Abstract

To overcome the limitations of lengthy laboratory testing cycles and insufficient on-site responsiveness, this study developed an online rapid monitoring device for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in soil–water–air systems based on photoionization detection (PID) technology. The device integrates modular sensor units, incorporates an electromagnetic valve-controlled multi-medium adaptive switching system, and employs an internal heating module to enhance the volatilization efficiency of VOCs in water and soil samples. An integrated system was developed featuring “front-end intelligent data acquisition–network collaborative transmission–cloud-based warning and analysis”. The effects of different temperatures on the monitoring performance were investigated to verify the reliability of the designed system. A polynomial fitting model between concentration and voltage was established, showing a strong correlation (R2 > 0.97), demonstrating its applicability for VOC detection in environmental samples. Field application results indicate that the equipment has operated stably for nearly three years in a mining area of Shandong Province and an industrial park in Anhui Province, accumulating over 600,000 valid data points. These results demonstrate excellent measurement consistency, long-term operational stability, and reliable data acquisition under complex outdoor conditions. The research provides a distributed, low-power, real-time monitoring solution for VOC pollution control in mining and industrial environments. It also offers significant demonstration value for standardizing on-site emergency monitoring technologies in multi-media environments and promoting the development of green mining practices.

1. Introduction

Mining and industrial operations represent significant anthropogenic sources of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), a diverse group of carbon-based chemicals characterized by high vapor pressure at ambient temperature. Within mining environments, VOC emissions arise through multiple pathways [1,2]. These include the liberation of methane and light hydrocarbons from coal seams via ventilation systems, exhaust emissions from diesel-powered machinery, and volatilization during processes such as mineral transport, loading, and unloading [3]. Furthermore, the application of organic solvents in mineral extraction and beneficiation, coupled with organic exhaust gases generated during high-temperature ore roasting and smelting operations, constitutes substantial VOC sources [3,4,5].

Upon environmental release, VOCs are subject to complex biotic and abiotic degradation processes that fundamentally determine their persistence and ecological impact. Abiotic transformation mechanisms encompass photochemical degradation—where sunlight-driven reactions oxidize compounds like benzene and toluene, contributing to secondary aerosol formation—hydrolysis in aquatic environments, and reactions with atmospheric oxidants including ozone (O3) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH). Concurrently, biodegradation pathways, predominantly mediated by microbial metabolism in soils and sediments, exhibit compound-specific efficiency; while alkanes and simple aromatics are readily degraded under aerobic conditions, chlorinated VOCs demonstrate markedly slower degradation kinetics due to structural complexity and potential microbial toxicity [4]. These differential degradation rates result in highly variable environmental lifetimes, ranging from hours to days for atmospheric VOCs to months or years for compounds sequestered in soils or groundwater, contingent upon factors such as temperature, oxygen availability, organic content, and microbial community structure [5,6].

The environmental ramifications of VOC emissions are multifaceted. Beyond their role as key precursors in the photochemical formation of ozone and secondary organic aerosols—primary constituents of smog and haze—VOCs pose direct threats to human health, including respiratory and neurological toxicity, with benzene specifically classified as a Group I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [7,8]. Ecosystem-level impacts manifest through inhibition of soil microbial activity, disruption of nutrient cycling processes, and potential bioaccumulation through trophic transfer, collectively contributing to the degradation of mining-affected ecosystems [9,10].

The significant environmental and health impacts of VOCs have prompted the development of comprehensive regulatory frameworks globally. The United States, an early adopter of VOC controls, has established extensive emission standards and technological guidelines under the Clean Air Act [11,12]. Similarly, the European Union has implemented directives targeting VOC emissions across multiple sectors, including solvent application, surface coatings, and fuel distribution. In China, over twenty VOC-related policy documents have been promulgated since 1993, with the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan establishing explicit reduction targets, sector-specific standards, and localized implementation protocols [13]. The recent draft issuance of the National Pollution Control Technology Guidance Catalogue (2024) by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment further exemplifies the ongoing refinement and standardization of VOC mitigation technologies.

Effective implementation and enforcement of these regulatory measures are fundamentally dependent upon accurate and reliable monitoring methodologies. Monitoring systems serve dual critical functions: enabling regulatory compliance verification and emission reduction enforcement while simultaneously generating essential data for air quality assessment, pollution source identification, and control strategy evaluation. The resultant data streams provide the scientific foundation for developing targeted policies, managing pollution at its source, and safeguarding both ecological integrity and public health [14,15].

Conventional VOC monitoring approaches, typically involving sample collection on sorbent tubes followed by laboratory analysis using thermal desorption–gas chromatography, provide high analytical precision but are inherently constrained by extended analysis cycles, delayed reporting timelines, and inability to support real-time decision-making at contamination sites [16,17]. These limitations are particularly problematic in mining contexts, where rapidly changing conditions and potential emergency scenarios demand immediate response capability. Although photoionization detectors (PIDs) have gained prominence for field deployment owing to their rapid response, portability, and sensitivity to low VOC concentrations [18,19,20], prevailing commercial systems remain predominantly configured for single-medium (atmospheric) monitoring. This technological gap highlights the pressing need for integrated monitoring solutions capable of simultaneous, adaptive measurement across the soil–water–air continuum—a capability essential for comprehensive environmental assessment in mining regions.

To address this technological deficit, the present study aims to develop and validate a novel integrated system for rapid, online VOC monitoring across multiple environmental media. The specific research objectives and innovations encompass: (1) designing an electromagnetic valve-controlled multi-medium switching mechanism enabling sequential monitoring of air, soil, and water phases using a single PID sensor; (2) integrating internal heating modules to enhance VOC volatilization efficiency from water and soil matrices, thereby improving detection sensitivity; (3) constructing a low-power, modular platform capable of sustained, solar-powered operation in field environments; and (4) implementing a cloud-based early warning platform incorporating hybrid forecasting models (ARIMA, GM, and BP neural networks) for dynamic pollution risk assessment. This research provides a comprehensive technical framework and theoretical foundation for advancing emergency monitoring capabilities in industrial and mining sectors while simultaneously contributing to the standardization of rapid, multi-media environmental assessment methodologies.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. System Architecture and Monitoring Device Composition

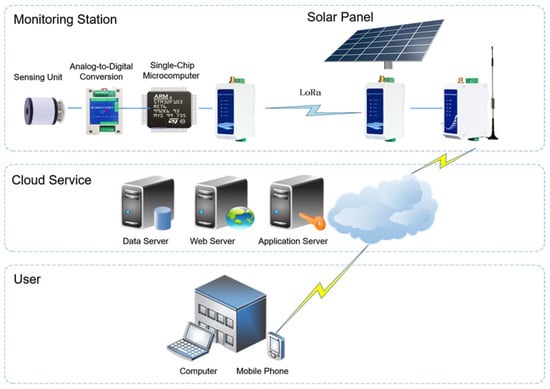

The rapid monitoring and early warning system for soil–water–air VOCs consists of three main components: the monitoring equipment, the cloud server, and user interface devices. The overall architectural framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Rapid Monitoring System for Soil–Water–Air VOCs.

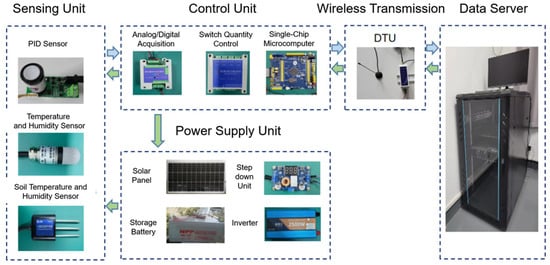

At the front end, the monitoring equipment adopts a modular architecture comprising four major units: the sensor unit, control unit, data transmission unit, and power supply unit (Figure 2). The device integrates multiple functions, including solar power supply, high-precision VOC detection, multi-protocol data conversion and transmission, and remote access capability. Standardized interface design ensures coordinated operation among all modules, enabling real-time monitoring and wireless transmission of VOC concentration data in environmental media.

Figure 2.

Overall design diagram of VOCs monitoring device.

Data are transmitted between monitoring points and to the cloud via a communication network based on LoRa technology, RS-485 bus, and 4G/5G networks. The cloud-based monitoring analysis system processes and analyzes uploaded data in real time. It establishes a dynamic risk monitoring and early warning framework using ARIMA, GM, and BP algorithmic models. When preset thresholds are exceeded, automatic alarms are triggered, and alert notifications are sent to designated users via SMS. Additionally, users can access real-time monitoring data and system status through desktop or mobile interfaces. The system is designed with low-power components and energy-efficient operational modes, allowing long-term, solar-powered deployment in field environments.

2.2. Device Design and Fabrication

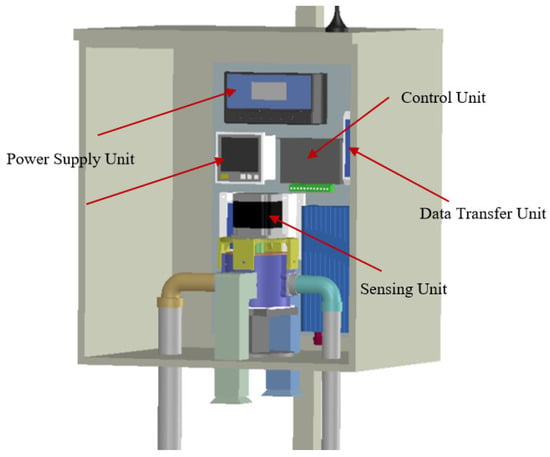

Based on preliminary design requirements, the SolidWorks 2021 modeling platform was used to construct parametric 3D solid models for each component of the signal module (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional model diagram of the VOCs monitoring device.

2.2.1. Soil–Water–Air Sampling and Sensing Unit

As the system’s front-end sensing component, the sensing unit serves as the foundation for environmental data acquisition. The sensing unit integrates a JEC-PID photoionization gas sensor (10.6 eV UV lamp) with a minimum detection limit of 100–1000 ppb and a measurement range of 0–2000 ppm for isobutylene, an environmental temperature-humidity sensor, and a soil temperature-humidity sensor. These components collectively measure relevant physical parameters and VOC concentrations, enabling multi-dimensional data acquisition.

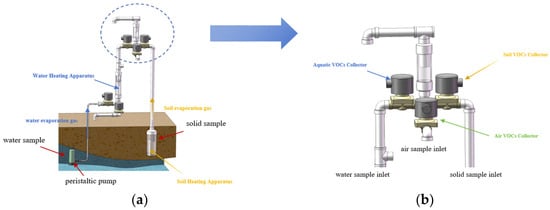

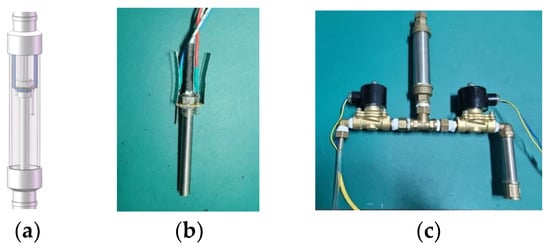

A key innovation of this system is the electromagnetic valve-controlled commutator (reversing device), which switches the sample gas flow path, enabling a single PID sensor to sequentially collect samples from air, soil, or water channels. This design allows integrated multi-media monitoring using a single detector, significantly reducing cost and complexity compared to multi-sensor setups. The reversing device features a simple structure and high operational stability. The electromagnetic valve is a standardized component that requires no custom fabrication. In terms of control logic, the electromagnetic valve operates solely in an on-off mode, resulting in simpler algorithms and enhanced operational stability. The structural diagram of the collection unit is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The structural design diagram of the acquisition unit, including: (a) overall structural diagram; (b) commutator structure.

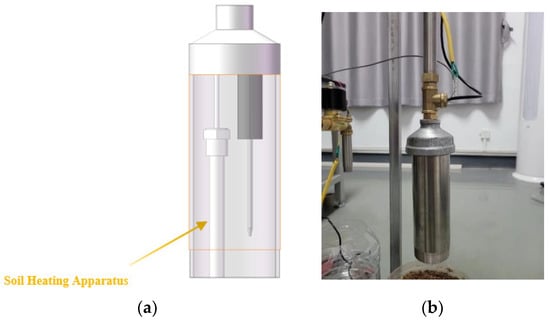

For VOC monitoring in water samples, heating plays a critical role by enhancing VOC volatilization efficiency. The device automatically collects water samples and subsequently heats them to promote VOC release, ensuring accurate detection. Stainless steel electric resistance heating rods (100 W, Xilong) were employed, with temperature regulated by a PID algorithm integrated within the main control unit. The specific design and physical diagram are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Design and physical diagram of the water VOCs collection module. (a) Water Heating Apparatus; (b) Heating rod; (c) Aquatic VOCs collector.

For soil monitoring, internal heating is utilized. The temperature increase induced by heating rods promotes VOC volatilization within the soil matrix, facilitating sample collection and concentration determination. Internal heating enhances thermal efficiency at equivalent energy input, thereby reducing overall energy consumption. Under solar-powered operation, the system exhibits extended battery life and improved operational stability. The design and actual device diagram of soil VOCs collection are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Design and actual device of VOCs Collection Module in Soil Matrix. (a) Soil Thermal Regulation Module; (b) Soil VOCs collector.

2.2.2. VOC Transport and Sampling Mechanism

The system employs a built-in pump (Kamoer, flow rate 0.5 L/min) to draw environmental samples into the detection pathway. For air monitoring, ambient air is continuously drawn through the air sampling channel. For water and soil monitoring, the internal heating modules promote VOC volatilization, and the released gases are transported to the PID sensor via the same pumping system. The electromagnetic valve commutator sequentially switches between the three media channels (air, water, soil) under program control, allowing a single PID sensor to monitor all three media types.

For soil monitoring, the system uses a sealed chamber design where soil samples are placed and heated to promote VOC release. The system operates in periodic sampling mode rather than continuous soil monitoring. After each measurement cycle, the chamber is purged with clean air to prepare for the next sampling event, ensuring that ‘new’ VOCs can be measured in subsequent cycles.

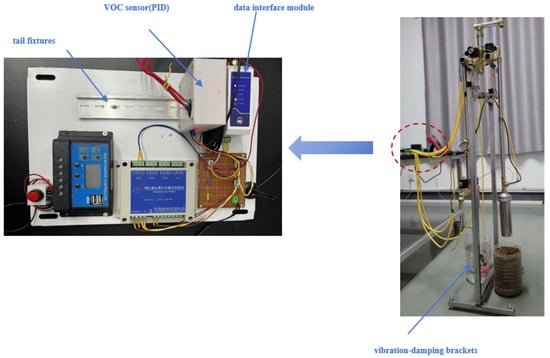

2.3. Device Integration and Laboratory Calibration

After independent design and performance verification of each functional module, the device entered the system integration phase. Each module was individually verified for performance prior to system integration. Functional testing was performed using a reference VOC source (standard isobutylene gas) to evaluate the sensor unit’s response and calibrate it against a factory-calibrated RC-0910 PRO PID meter. The heating modules were tested for temperature accuracy and stability, while the data transmission system was validated for integrity and transmission success rate. This stage was implemented in strict accordance with detailed module design drawings, incorporating practical operational requirements and spatial layout considerations to ensure precise installation of all electrical components. Precision positioning fixtures were employed for the core VOC sensor to maintain the optimal detection orientation and prevent any installation deviations that could affect measurement accuracy. Vibration-damping brackets and cushioning materials were applied to isolate the sensor from external mechanical interference. The data interface module was mounted using standard rail fixtures to enhance structural stability and modular expandability, with adequate space reserved to facilitate future maintenance and debugging. The fully integrated rapid VOC monitoring device is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Actual installation diagram of the soil–water–air rapid monitoring device.

2.4. Experimental Methods and Materials for Performance Evaluation

2.4.1. Waterborne VOCs Testing

This study systematically investigated the volatilization kinetics of VOCs using the Aquatic VOCs Collector (as shown in Figure 5c) filled with acrolein solutions at concentrations of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mol/L, and operated at 50 °C, 55 °C, 60 °C, 65 °C, and 70 °C. During each experiment, the solution concentration was maintained constant while the temperature was adjusted. Gas-phase VOC concentrations were continuously recorded by the device until volatilization was complete and the concentration returned to baseline levels. By monitoring VOCs concentration variations over time under different conditions, the coupling effects between concentration and temperature on volatilization behavior were elucidated. The instruments used in the experiment shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Instruments used in the experiment.

2.4.2. Soil Sample VOCs Testing

Soil samples were collected from an industrial site and adjacent uncontaminated surface soils in Dongying, Shandong Province. Because the soil contained diverse and unidentified VOCs, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis was conducted to identify the principal components.

Analyses were conducted using an Agilent 8890-5977B GC-MS system equipped with an Agilent HP-5MS UI capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm), where the 8890 component represents the gas chromatograph responsible for sample separation, and the 5977B represents the mass spectrometer for compound detection and identification.

The injection port temperature was set to 250 °C under a split mode with a 20:1 ratio. Ultra-pure helium gas (>99.999%) was used as the carrier gas at a column flow rate of 1 mL/min. Samples were analyzed using a programmed temperature ramp: the initial temperature was 45 °C, increased at 5 °C/min to 300 °C, and held at 300 °C for 5 min. The electron ionization (EI) source and quadrupole analyzer temperatures were set to 230 °C and 150 °C, respectively. The EI source operated in electron impact mode at 70 eV. Ions generated were detected by the quadrupole analyzer using an electron multiplier across a mass-to-charge (m/z) range of 33–500 u.

The main VOC components identified in the soil samples by GC-MS analysis are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The main components of soil samples.

Approximately 4.00 g of each soil sample was weighed and placed in a glass tube. The samples were homogenized by sieving through a 2-mm mesh before subdivision for GC-MS analysis and device testing. Ten milliliters of hexane were added as an extractant. After settling, the supernatant was transferred to the Soil VOCs Collector for heating at the same temperature gradient used for water samples (50 °C, 55 °C, 60 °C, 65 °C, 70 °C). The same supernatant used for GC-MS analysis was employed in the Soil VOCs Collector for comparative testing under identical temperature conditions. VOC concentrations were subsequently monitored by the device to establish the correlation between sensor voltage output and actual VOC concentration.

2.4.3. Airborne VOCs Testing

For ambient air monitoring, the system’s electromagnetic valve switches the PID sensor to the air sampling channel. The device continuously draws in ambient air, and the VOC concentration is recorded at a predefined interval (set to 50 s in this study). No pre-concentration or pre-treatment is required for atmospheric samples under typical conditions, enabling genuine real-time, continuous monitoring of airborne TVOC levels.

2.5. Software and Early Warning System Design

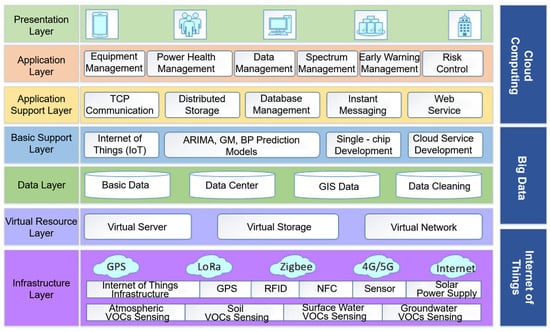

The VOCs monitoring and early warning platform system is architecturally divided into infrastructure layer, virtual resource layer, data layer, foundational support layer, application support layer, application layer, and presentation layer. Each layer is designed and developed based on modular thinking for functional structure, ensuring system stability, maintainability, and reconfigurability while meeting system functional requirements. The construction diagram is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Construction of the Monitoring and Early Warning System Platform.

The upper-level machine monitoring device for VOCs used in the design was developed in the Visual Studio (VS) development environment using C#. In VOCs monitoring work, the system collects relevant data. The sampling interval for PID is set to 50 s per sample, i.e., the collection device acquires one voltage data every 50 s, presenting the collected voltage values on a pre-designed client page, thereby enabling real-time monitoring of VOCs.

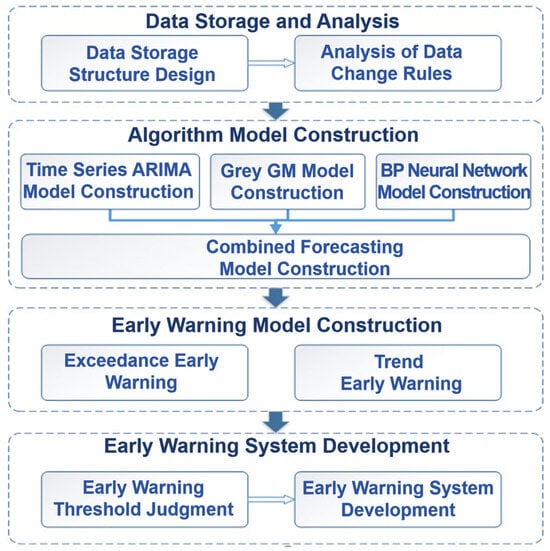

The internal logical structure of the monitoring and early warning system (Figure 9) mainly includes data storage analysis, algorithm model construction, and early warning model construction. Data storage analysis is responsible for establishing the raw data storage structure and the cleaned data storage structure of cloud-based monitoring data; algorithm model construction is based on ARIMA, GM, and BP models, determining their respective weight coefficients, and establishing a combined forecasting model; early warning model construction involves developing over-limit early warning functions for short cycles and trend early warning functions for long cycles; then, based on data feature analysis, determining the early warning thresholds, and completing the development of the early warning system.

Figure 9.

Logic structure diagram of the monitoring and early warning system.

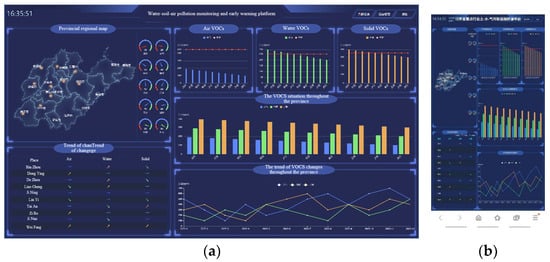

The completed monitoring and early warning system is illustrated in Figure 10. The system features screen adaptability, allowing it to be viewed on various types of display terminals such as computers, tablets, and mobile phones.

Figure 10.

Real-time Monitoring and Early Warning Front-end System (a) Desktop version; (b) Mobile version.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Waterborne VOCs Testing and Trend Analysis

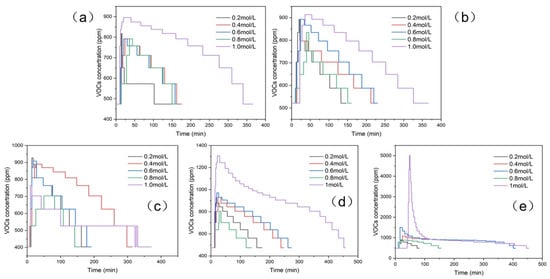

Experimental results indicate that the time window for reaching peak concentration exhibits a non-monotonic relationship with changes in concentration and temperature. Specifically, as the solution concentration increases, the peak time first delays and then shortens. The detailed peak times observed under different conditions are presented in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 11.

Table 3.

Time to reach peak concentration (minutes) at different temperatures and concentrations.

Figure 11.

Reaction trend of different acrolein solutions at (a) 50 °C; (b) 55 °C; (c) 60 °C; (d) 65 °C; (e) 70 °C.

At 0.8 mol/L, enhanced molecular association and increased viscosity caused a pronounced decline in volatilization efficiency at 70 °C, yielding a maximum concentration of only 879 ppm. In contrast, at 1.0 mol/L, intensified thermal motion overcame these effects, restoring high volatilization intensity with a peak of 5018 ppm. The results suggest that the volatilization process is regulated by three interacting mechanisms: (i) surface tension-vapor pressure equilibrium, (ii) diffusion-mass transfer competition, and (iii) molecular association dynamics.

The time required for complete volatilization exhibited a positive correlation with temperature. At 70 °C, the duration for concentration to return to baseline extended up to 457 min, reflecting a substantial prolongation of the volatilization process at elevated temperatures. The volatilization characteristics of acrolein solutions exhibited pronounced concentration–temperature coupling effects, summarized as follows: Low concentration range (0.2–0.6 mol/L): The optimal volatilization temperature shifted toward higher temperatures as concentration increased. The 0.2 mol/L solution exhibited a maximum volatilization concentration of 809 ppm at 60 °C, whereas the 0.4–0.6 mol/L solutions achieved higher volatilization fluxes at 70 °C, attributed to the disruption of intermolecular forces by thermal activation. High concentration range (0.8–1.0 mol/L): The system exhibited distinct nonlinear behavior. At 70 °C, volatilization efficiency of the 0.8 mol/L solution decreased sharply (879 ppm) owing to molecular association and viscosity effects. However, the 1.0 mol/L solution regained high volatilization intensity (5018 ppm) as thermal motion became the dominant factor.

3.2. Soil VOCs Testing and Pattern Analysis

3.2.1. Effect of Temperature on Monitoring VOCs Concentration in Soil

The heating temperature of the water bath was adjusted sequentially to 50 °C, 55 °C, 60 °C, 65 °C, and 70 °C. The soil extract solution was heated until gas-phase VOC release occurred, during which VOC concentrations were monitored and recorded under each temperature condition.

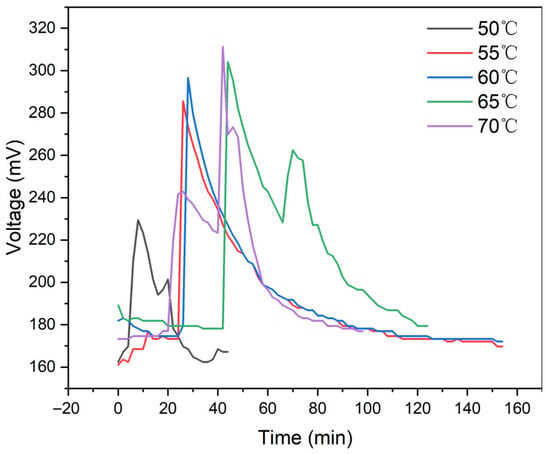

As shown in Figure 12, under a fixed extractant concentration, changes in heating temperature produced an initial voltage of approximately 161.1 mV, corresponding to the baseline VOC concentration in air. With increasing heating time, the voltage response of the collection device initially increased to a maximum value and then gradually decreased. When the VOCs in the supernatant had fully evaporated, the voltage signal returned to its initial baseline level.

Figure 12.

Reaction Trend of VOCs in Soil Samples at Different Temperatures.

Comparison across temperatures revealed that within 10–44 min after heating initiation, all temperature conditions exhibited a peak voltage response, corresponding to the highest concentration of volatilized VOCs. Specifically, the maximum voltage reached 311.3 mV at 70 °C, while other temperatures produced peaks between 220 and 310 mV. This suggests that 70 °C is optimal for VOC volatilization, facilitating more efficient VOC release from the soil supernatant. The rate of voltage increase varied among temperatures: at 50 °C, the maximum was reached earliest but with a relatively low value (229.5 mV). At 55 °C, the second-fastest response was observed, while at 65 °C and 70 °C, the time to reach the maximum was longer, with 70 °C exhibiting the highest overall voltage peak. The duration required for VOC signals to return to baseline varied by temperature: 60 °C exhibited the longest decay period (154 min), followed by 55 °C, whereas 50 °C showed the shortest recovery duration (44 min).

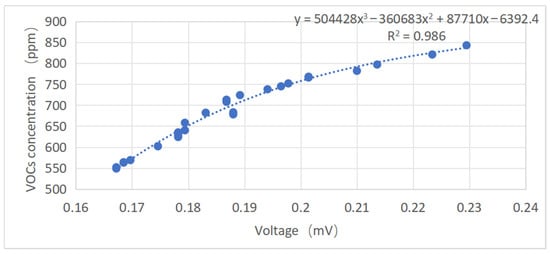

3.2.2. Correlation Between Rapid Monitoring Device Readings and VOC Data at Various Temperatures

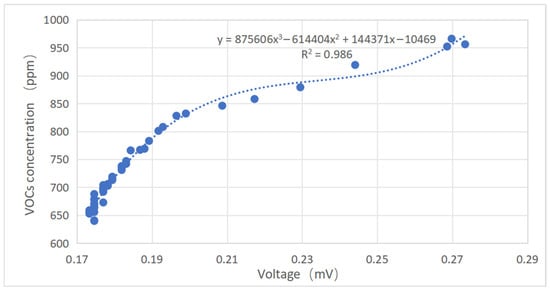

A comparative analysis was performed across all tested temperatures (50 °C, 55 °C, 60 °C, 65 °C, 70 °C). Data from the soil–water–air VOCs rapid monitoring device were correlated with measurements from a factory-calibrated RC-0910 PRO PID meter, verified using standard isobutylene gas prior to testing. Various fitting models (linear, quadratic, cubic, exponential, logarithmic) were tested. A cubic polynomial model was selected as it consistently provided the best fit (highest R2) across all temperature datasets, likely due to its ability to capture the nonlinear saturation characteristics of the PID sensor response over the measured concentration range. The resulting calibration curves and their corresponding equations and R2 values are summarized in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Variation trend of VOCs in soil samples at 50 °C.

In Figure 10, y represents the actual gas-phase VOC concentration, and x represents the corresponding voltage value recorded by the acquisition device. The fitted parameters are: p1 = 504,428, p2 = −360,683, p3 = 87,710, p4 = −1321.3, with an R2 value of 0.986, indicating excellent correlation. The polynomial fitting function is expressed as:

y = 504,428x3 − 360,683x2 + 87,710x − 6392.4

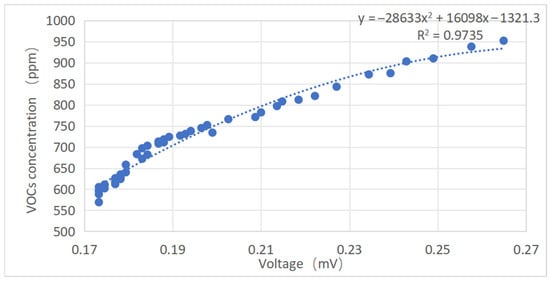

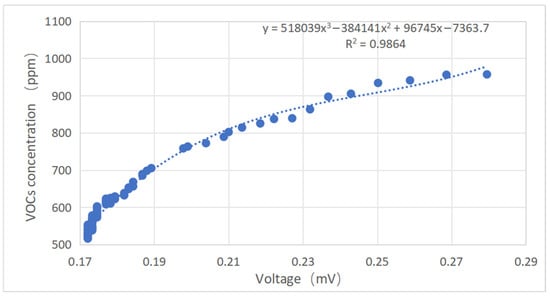

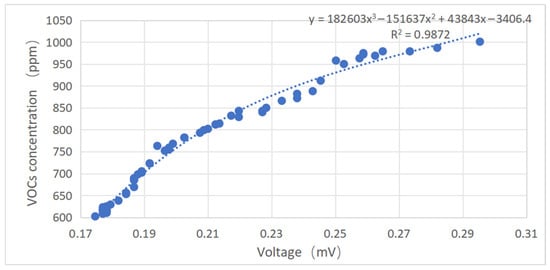

Similar calibration procedures were performed at 55 °C, 60 °C, 65 °C, and 70 °C, yielding strong correlations (R2 > 0.97) in all cases, as shown in Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17 and Equations (2)–(5). These results confirm the reliability of the device for quantifying VOCs in soil samples across a range of environmentally relevant temperatures.

Figure 14.

Variation trend of VOCs in soil samples at 55 °C.

y = −28,633x2 + 16,098x − 1321.3

Figure 15.

Variation trend of VOCs in soil samples at 60 °C.

y = 518,039x3 − 384,141x2 + 96,745x − 7363.7

Figure 16.

Variation trend of VOCs in soil samples at 65 °C.

y = 182,603x3 − 151,637x2 + 43,843x − 3406.4

Figure 17.

Variation trend of VOCs in soil samples at 70 °C.

y = 87,5606x3 − 614,404x2 + 144,371x − 10,469

In summary, the results indicate that the sensor exhibits a strong correlation (R2 > 0.97) with actual VOC concentrations across different temperatures, making it suitable for detecting VOCs in soil.

3.3. Field Application and Performance

During the setup of equipment on-site, various factors were considered, such as the sensitivity, stability, interference resistance of sensors, and the processing capability and real-time performance of microcontrollers. This set of equipment has been implemented and has been operating stably for over two years in a certain industrial park in Shandong and Anhui provinces, China. Under complex and variable outdoor environmental conditions, long-term operational stability is evidenced by continuous data acquisition capability over the reported period. The installation image of the equipment is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Equipment Installation Diagram.

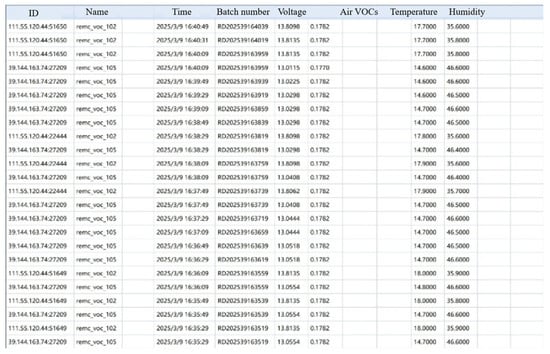

The system has demonstrated robust performance, maintaining data collection functionality for the majority of the deployment period, accumulating over 600,000 valid data points. Figure 19 shows part of the monitoring data from 2025, further demonstrating the effectiveness of the device in real-time monitoring of VOCs concentration and dynamic changes, providing solid data support for environmental regulation and pollution control in industrial parks.

Figure 19.

Monitoring Data for 2025 (Partial).

3.4. Discussion

The laboratory results demonstrate the critical influence of temperature and concentration on VOC volatilization kinetics, which validates the design choice to incorporate internally controlled heating modules for both water and soil samples. The non-monotonic relationship between concentration and peak time, along with the coupling effects at high concentrations, underscores the complexity of VOC release in environmental matrices. Our device’s ability to operate at different temperatures allows for the optimization of detection sensitivity for various contamination scenarios, a feature not commonly found in standard PID-based field instruments.

The high correlation (R2 > 0.97) between the device’s voltage output and reference concentrations across a range of temperatures confirms the reliability of the calibrated system. This performance is comparable to that of commercial PIDs used in single-medium applications [15,16]. The successful translation of laboratory calibration to the field is evidenced by the long-term stability and continuous data acquisition over two years, with field data trends showing plausible diurnal and seasonal variations consistent with expected VOC behavior in industrial environments.

A recognized limitation of the current system, inherent to non-separative PID technology, is its provision of a total VOC (TVOC) reading without speciation of individual compounds. While TVOC concentration is a valuable and sufficient metric for many regulatory, screening, and emergency response purposes (e.g., source tracking, leak detection, overall exposure risk assessment), it does not provide compound-specific information necessary for detailed risk analysis of specific toxic VOCs. Future work will focus on integrating a miniaturized gas chromatography (GC) column or other pre-separation techniques upstream of the PID to enable limited speciation of key VOC components.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully developed and validated an advanced integrated rapid monitoring system for soil–water–air VOCs to address the challenges of complex environmental media and poor detection timeliness. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The monitoring equipment adopts a modular design concept, decomposing functions into independent and flexible combination units, facilitating installation, maintenance, and upgrades.

(2) At the core technology level, it integrates photoionization detection technology with an innovative electromagnetic valve-controlled multi-medium switching system and multiple network transmission methods, enabling real-time, online monitoring of VOCs across three environmental media using a single device.

(3) The internal heating system precisely controls sample temperature, preventing VOC volatility loss or adsorption residue, ensuring that VOC components in samples fully enter the detection process. Laboratory tests revealed significant concentration–temperature coupling effects on VOC volatilization, guiding optimal operational parameters.

(4) A strong correlation (R2 > 0.97) was established between sensor voltage and actual VOC concentration across different temperatures (50–70 °C), validating the device’s quantitative detection capability for soil VOCs.

(5) The system incorporates a cloud-based early warning platform with a combined forecasting model (ARIMA, GM, BP), significantly enhancing the ability to predict VOC pollution risks.

(6) Field application results demonstrate that the equipment has been operating continuously and stably in industrial parks for over two years, accumulating more than 600,000 data points, which confirms its excellent measurement accuracy, stability, and reliability in complex outdoor environments.

This research provides an efficient and practical technical solution for distributed, low-power, real-time VOC monitoring in mines and industrial parks. It represents a significant step beyond conventional single-medium PIDs by offering an integrated approach. The system holds significant demonstration significance for promoting the development and standardization of on-site emergency monitoring technologies for volatile organic compounds in multi-media environments. A key limitation is the provision of total VOC data rather than speciated measurements. Future research will therefore focus on expanding the system’s capability to include speciated VOCs, potentially through integration with miniaturized separation techniques, and on optimizing algorithm model adaptability to enhance the system’s universality and intelligence level in even more complex environments. The integration of complementary sensors, such as for ozone (O3), is also planned to provide a more holistic environmental monitoring solution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F.; methodology, X.F. and C.D.; software, H.G., F.Z., J.Y. and C.D.; validation, H.G., F.Z. and J.Y.; formal analysis, H.G., F.Z. and S.C.; investigation, F.Z., J.Y., H.G. and X.F.; resources, X.F.; data curation, H.G., S.C. and X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G., F.Z. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.F.; visualization, H.G. and J.Y.; supervision, X.F.; project administration, X.F.; funding acquisition, X.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Bonanza and Precision Mining, Guizhou Provincial Academician Expert Workstation (KXJZ [2024]003), Anhui University of Science and Technology’s high-level talent team launch funding project (YJ20250001), The National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFC2902100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sekar, A.; Varghese, G.K.; Varma, R. Exposure to volatile organic compounds and associated health risk among workers in lignite mines. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 4293–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espinosa, A.J.; Peña-Heras, A.; Rossini-Oliva, S. Atmospheric Emissions of Volatile Organic Compounds from a Mine Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge and Tomato Plants (Lycopersicum esculentum L.). Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, C.K.; Padhy, P.K. Emissions of Total Volatile Organic Compounds from Anthropogenic Sources in India. J. Ind. Ecol. 1998, 2, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Tang, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, H.; Wen, M.; Li, G.; An, T. Aqueous VOCs in complex water environment of oil exploitation sites: Spatial distribution, migration flux, and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Song, L.; He, H.; Zhang, W. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in Soil: Transport Mechanisms, Monitoring, and Removal by Biochar-Modified Capping Layer. Coatings 2024, 14, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Gao, W.; Lin, Y.; Liu, J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, K. Soil volatile organic compounds: Source-sink, function, mechanism, detection, and application analysis in environmental ecology. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 184, 118125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S.; Liu, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Zheng, S. Assessing the hazard of diesel particulate matter (DPM) in the mining industry: A review of the current state of knowledge. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, J.; Ruan, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiao, X.; Sun, J.; Sun, K. Exposure to volatile organic compounds induces cardiovascular toxicity that may involve DNA methylation. Toxicology 2024, 501, 153705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; An, T. A review of disrupted biological response associated with volatile organic compound exposure: Insight into identification of biomarkers. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.-J.; Li, X.-Y.; Shen, Y.-C.; You, J.-X.; Wen, M.-Z.; Wang, J.-B.; Yang, X.-T. Assessing volatile organic compounds exposure and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in US adults. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1210136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Joseph, A.E.; Wachasunder, S.D. Qualitative Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds in Outdoor and Indoor Air. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2004, 96, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Zhu, X.; Niu, W. Comparative study of domestic and foreign emissionstandards for volatile organic compounds. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 5, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Li, B.; Li, J. Review on emission standards of atmospheric volatile organic compounds from fixed sources at home and abroad. Environ. Pollut. Control 2024, 24, 1384–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, K.; Iizuka, A.; Inoue, Y.; Mizukoshi, A.; Noguchi, M.; Yamasaki, A.; Yanagisawa, Y. Development of a Combined Real Time Monitoring and Integration Analysis System for Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 4100–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Naidu, R.; Chadalavada, S.; Bekele, D.; Gell, P.; Donaghey, M.; Bowman, M. Application of portable gas chromatography–mass spectrometer for rapid field based determination of TCE in soil vapour and groundwater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moufid, M.; Bouchikhi, B.; Tiebe, C.; Bartholmai, M.; El Bari, N. Assessment of outdoor odor emissions from polluted sites using simultaneous thermal desorption-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (TD-GC-MS), electronic nose in conjunction with advanced multivariate statistical approaches. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 256, 118449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestage, J.; Day, C.; Husheer, S.L.G.; Winter, W.T.; Ho, W.O.; Saffell, J.R.; Hutter, T. Selective Detection of Volatile Organics in a Mixture Using a Photoionization Detector and Thermal Desorption from a Nanoporous Preconcentrator. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, B.; Qiao, J.; Lin, W.; Zhang, W. Air Pollution Monitoring by Integrating Local and Global Information in Self-Adaptive Multiscale Transform Domain. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 3716–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krismadinata; Aulia, F.B.; Maulana, R.; Yuhendri, M.; Azri, M.; Kanimozhi, K. Development of graphical user interface for boost converter employing visual studio. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1281, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Gopalan, S.; Luo, F.; Amreen, K.; Singh, R.K.; Goel, S.; Lin, Z.; Naidu, R. Review and Perspective: Gas Separation and Discrimination Technologies for Current Gas Sensors in Environmental Applications. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 1373–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).