Abstract

Organic field-effect transistor (OFET) biosensors have emerged as a transformative technology for clinical biomarker detection, offering unprecedented sensitivity, selectivity, and versatility in point-of-care (POC) diagnostics. This review examines the fundamental principles, materials innovations, device architectures, and clinical applications of OFET-based biosensing platforms. The unique properties of organic semiconductors, combined with advanced biorecognition strategies, enable the detection of clinically relevant biomarkers at low concentrations. Recent developments in organic semiconductor materials have significantly enhanced device performance and stability. The integration of novel device architectures such as electrolyte-gated OFETs (EGOFETs) and extended-gate configurations has expanded the operational capabilities of these sensors in aqueous environments. Clinical applications span a broad spectrum of biomarkers, demonstrating the versatility of OFET biosensors in disease diagnosis and monitoring. Despite remarkable progress, challenges remain in terms of long-term stability, standardization, and translation to clinical practice. The convergence of organic electronics, biotechnology, and clinical medicine positions OFET biosensors as a promising platform for next-generation personalized healthcare and precision medicine applications.

1. Introduction

The accurate and timely detection of clinical biomarkers lies at the foundation of modern healthcare, enabling early diagnosis, precise monitoring of disease progression, and informed evaluation of therapeutic responses. Conventional diagnostic techniques, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and electrochemical biosensors, have demonstrated reliability and sensitivity but remain constrained by lengthy assay protocols, costly and bulky instrumentation, and limited adaptability for POC testing [1]. These shortcomings have intensified the demand for innovative sensing platforms that are rapid, ultrasensitive, highly selective, and functional within the complexity of biological fluids.

OFET biosensors have emerged as one of the most compelling alternatives to traditional methods, owing to the unique advantages of organic semiconductors [2]. Their solution processability, mechanical flexibility, low-cost fabrication, and facile chemical tunability distinguish them from conventional silicon-based devices [3]. Importantly, OFET biosensors enable label-free and miniaturized detection, often achieving femtomolar sensitivity, while operating at low voltages suitable for portable and wearable formats [4]. Advances in device engineering, particularly the adoption of electrolyte-gated and extended-gate configurations, have markedly improved performance in aqueous environments, addressing a long-standing barrier to clinical translation.

Recent research has highlighted the breadth of OFET biosensor applications across clinically relevant targets [5]. Innovations in organic semiconductors, spanning small molecules, conjugated polymers, and hybrid systems, have been complemented by sophisticated functionalization strategies that impart molecular recognition and biocompatibility [6,7]. This convergence has led to successful demonstrations of OFET platforms in detecting metabolic and cardiovascular biomarkers, cancer-associated proteins, neurological and inflammatory mediators, and infectious disease antigens. Extending beyond medical diagnostics, OFET biosensors are also increasingly explored for nucleic acid sensing and environmental monitoring, highlighting their versatility and translational potential [8].

By critically examining the state of the art, this review provides a systematic account of materials innovation, device architectures, and biorecognition strategies in OFET biosensors, alongside their clinical applications. Emphasis is placed on both the fundamental design principles and translational hurdles, highlighting opportunities for synergistic integration with biotechnology, nanomaterials, and digital health frameworks. Positioned at the intersection of organic electronics and precision medicine, OFET biosensors represent a transformative class of diagnostic technologies with the capacity to redefine the landscape of next-generation healthcare.

Although recent reviews by Niu et al. [8] and Amna and Ozturk [9] and have comprehensively surveyed OFET and related organic transistor biosensing platforms, the present work offers a distinct contribution by establishing a clinically oriented, architecture–performance–translation framework for OFET biosensors. Unlike prior narrative overviews, this review systematically consolidates OFET biosensors data using a PRISMA-based approach [10], enabling quantitative benchmarking of substrate composition, gate geometry, semiconductor class, and biorecognition strategy across 22 representative studies. Particular emphasis is placed on correlating device architecture—specifically extended-gate, dual-gate, and floating-gate designs—with their transduction efficiency, thereby providing actionable design principles for clinical translation. Furthermore, the review advances the field by integrating a critical assessment of operational challenges, including reproducibility and by outlining practical engineering strategies for scalable fabrication and long-term device reliability. Collectively, these aspects position this work as a translationally focused, data-driven synthesis that complements and extends existing literature toward real-world biomedical implementation of OFET biosensors. Moreover, to maintain systematic transparency, the review presents biomarker categories in proportion to their representation in the PRISMA-screened literature, with greater emphasis on those supported by more mature or extensive research.

2. Fundamentals of OFET Biosensing

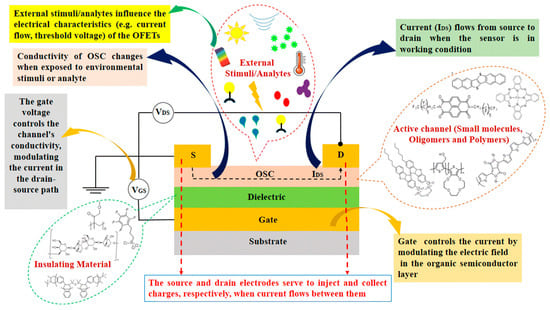

OFETs function as archetypal three-terminal electronic devices comprising a source, drain, and gate electrode, with the semiconducting channel electrostatically coupled to the gate through a dielectric layer (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of a Bottom-Gate, Top-Contact (BGTC) OFET-based sensor illustrating its operating principle (Reproduced with permission from [9]).

Upon application of a gate bias, charge carriers are induced at the semiconductor–dielectric interface, thereby modulating the current flowing between source and drain. This electrostatic control of channel conductivity constitutes the fundamental transistor mechanism (Figure 2). In biosensing contexts, OFETs are strategically adapted to transduce molecular recognition into measurable electronic signals. Typically, the semiconductor surface or gate dielectric is chemically functionalized with biorecognition moieties, including enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acids, or synthetic receptors, that exhibit high affinity toward the target analyte [11]. The binding of analytes perturbs the interfacial charge distribution or modifies the local electrostatic potential, which translates into measurable alterations in transistor characteristics such as drain current and threshold voltage [12]. A substantial body of work has demonstrated that these signal transductions occur in real time and without the requirement for exogenous labels, offering distinct advantages over conventional optical or enzymatic detection strategies. OFET-based biosensors are thus increasingly recognized as enabling platforms for POC diagnostics, wearable electronics, and integrated biomedical monitoring systems [13].

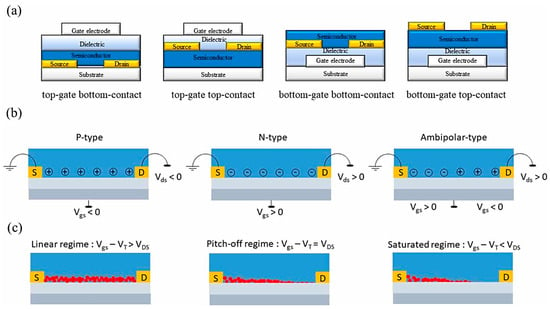

Figure 2.

Basic operating principles of OFETs: (a) representative device architectures; (b) classification based on charge carrier type; (c) schematic illustration of charge transport in the linear and saturation regimes. (Reproduced with permission from [8]).

The operational fidelity and sensitivity of OFET biosensors are intrinsically governed by the charge transport properties of the organic semiconductor layer. In contrast to the long-range band transport observed in crystalline silicon, charge conduction in organic materials is strongly dependent on molecular packing motifs, π–π stacking interactions, and the degree of energetic and structural disorder [14]. Conduction is generally mediated through thermally activated hopping or, under certain structural conditions, through delocalized band-like transport [15]. In biosensing applications, the semiconductor–dielectric interface assumes particular importance [16]. This is the site where analyte recognition takes place and where perturbations in local charge density directly modulate the conduction channel. EGOFETs, which exploit ionic motion in the electrolyte to achieve high capacitance and low-voltage operation, exemplify the benefits and trade-offs of interfacial engineering [17]. While such architectures enable biosensing at physiologically relevant voltages, the infiltration of ions into the active layer can compromise both stability and reproducibility. Recent studies emphasize the importance of functionalization strategies that simultaneously preserve the supramolecular order of the organic semiconductor and provide robust sites for biorecognition, as even minor disruptions in molecular packing can significantly degrade mobility and thus diminish sensor performance [18].

3. Organic Semiconductor Materials for Biosensors

The performance and applicability of OFET biosensors are intrinsically governed by the properties of their active semiconducting layers. Organic semiconductors serve as the transduction medium, translating biochemical interactions into measurable electrical signals [19]. Their chemical diversity, ease of molecular design, and solution processability have enabled a broad spectrum of material platforms tailored to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and operational stability in complex biological environments [20]. This section provides a systematic discussion of organic semiconductors employed in biosensing, encompassing small-molecule semiconductors, conjugated polymers, and hybrid nanocomposite systems.

Small-molecule semiconductors have been widely utilized in OFET biosensors owing to their well-defined molecular structures, high crystallinity, and reproducible electronic properties [21]. Prototypical examples include pentacene [22], dinaphtho [2,3-b:2′,3′-f]thieno [3,2-b]thiophene (DNTT) [23], and benzothieno [3,2-b][1]benzothiophene (BTBT) derivatives [24], which exhibit excellent charge transport characteristics under ambient conditions. Pentacene, one of the earliest small molecules integrated into OFET biosensors, offers high hole mobility but suffers from susceptibility to oxidation and limited aqueous stability. In contrast, DNTT and its fluorinated analogs demonstrate enhanced stability and reduced trap densities, making them favorable for extended-gate and electrolyte-gated biosensing formats. BTBT-based derivatives, with their tunable side-chain modifications, have further enabled the fabrication of flexible and printable OFET sensors [25]. Small-molecule semiconductors remain attractive for their superior carrier mobilities and ease of interfacial engineering, although their intrinsic environmental instability continues to necessitate encapsulation strategies or surface passivation.

Conjugated polymers such as poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) [26], poly[bis(thiophene)-benzothiadiazole] (PBTTT) [27], and diketopyrrolopyrrole-thiophene-thiophene (PDPP-TT) [28] have emerged as versatile alternatives to small molecules. Their processability from solution enables large-area device fabrication, while structural tunability allows optimization of solubility, energy levels, and functional group compatibility with bioreceptors. P3HT remains one of the most extensively studied polymers, combining good hole transport with facile blending in hybrid architectures. PBTTT, with its high degree of crystallinity, has shown remarkable stability under electrolyte gating, whereas PDPP-TT and related diketopyrrolopyrrole-based copolymers provide exceptional mobility and enhanced chemical robustness. In biosensing applications, conjugated polymers are particularly advantageous due to their mechanical flexibility, which supports integration into wearable and implantable formats. Moreover, functional side chains can be engineered to directly anchor biomolecules, improving specificity and lowering detection limits.

To address limitations in sensitivity, stability, and multifunctionality, hybrid materials and nanocomposites combining organic semiconductors with nanomaterials have gained prominence. Graphene/OFET hybrid systems [29] leverage graphene’s superior conductivity and surface area for enhanced signal amplification, while maintaining the flexibility of organic backbones. Similarly, carbon dots [30] and polymer composites introduce photoluminescent properties that enable dual-mode electro-optical sensing. ZnO–polymer blends [31] represent another emerging approach, where the inorganic component enhances electron mobility and environmental stability, complementing the biocompatibility of the polymer host. Such hybrid systems not only improve device performance but also expand sensing capabilities to include multiplexed and multi-analyte detection, which is highly desirable for complex clinical diagnostics.

4. Device Architectures and Design Strategies

The performance and applicability of OFET biosensors are strongly influenced by their underlying device architecture and design strategies. Over the past two decades, considerable efforts have been directed toward refining transistor geometries, gate configurations, and interfacial engineering methods to enhance sensitivity, stability, and operational compatibility in biological environments. Several architectures, ranging from traditional bottom-gate layouts to advanced electrolyte-gated and floating-gate systems, have been developed, each offering distinct advantages and trade-offs for clinical biomarker detection.

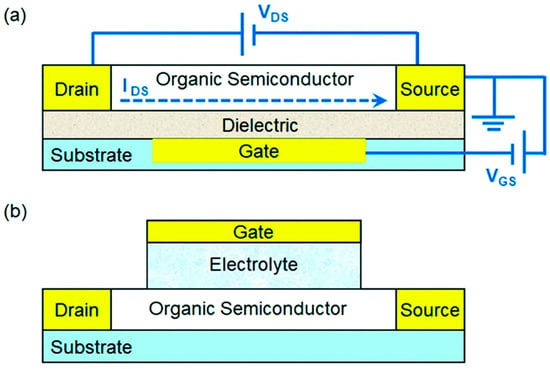

Bottom-gate and top-gate configurations represent the most fundamental device structures employed in OFET biosensing. In bottom-gate devices, the gate electrode and dielectric layer are positioned beneath the semiconducting channel, allowing relatively simple fabrication and compatibility with standard substrates such as Si/SiO2 (Figure 3a). Conversely, top-gate structures enable direct encapsulation of the organic semiconductor, providing improved protection against environmental degradation while permitting more versatile surface functionalization [32]. Both configurations have been widely adopted for immunosensor and enzyme-based transduction, with reported applications in detecting proteins, metabolites, and nucleic acids.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic representation of an OFET, illustrating the applied voltages (VDS and VGS) and the resulting source–drain current (IDS); and (b) schematic depiction of an EGOFET architecture. (Reproduced with permission from [33]).

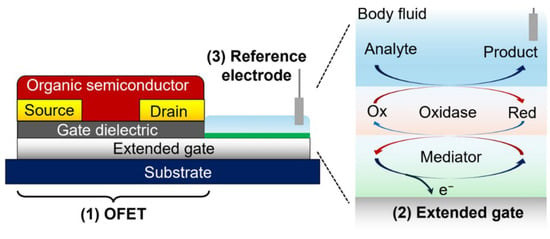

To overcome the limitations associated with solid dielectric layers in aqueous media, EGOFETs [34] and extended-gate OFETs have been introduced as more biocompatible alternatives. EGOFETs employ an electrolyte as the gate dielectric, enabling low-voltage operation and enhanced charge modulation due to electrical double-layer capacitance (Figure 3b). Extended-gate devices physically decouple the sensing interface from the active transistor, thereby minimizing direct exposure of the organic semiconductor to biological fluids and improving stability (Figure 4). These systems are particularly well-suited for label-free detection in complex media such as serum, plasma, and interstitial fluid, and they have demonstrated femtomolar sensitivity across a broad range of clinical biomarkers.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of an extended-gate OFET configured for biosensing, in which the extended-gate surface is modified with an immobilized enzymatic layer. (Reproduced with permission from [35]).

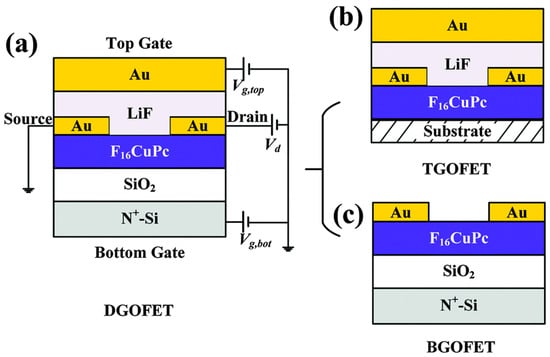

Further refinements include dual-gate (Figure 5) [36] and floating-gate (Figure 6) systems [37], which introduce additional design complexity to achieve enhanced control over channel conductivity. Dual-gate architectures allow independent tuning of the sensing interface and transistor channel, offering improved signal amplification and reduced noise.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of OFETs based on F16CuPc with LiF as the top-gate dielectric. (a) Cross-sectional view of a dual-gate OFET (DGOFET), consisting of an N+-Si substrate as the bottom gate with SiO2 dielectric, F16CuPc as the organic semiconductor channel, Au source and drain electrodes, a LiF dielectric layer, and a top Au gate. The DGOFET can be regarded as a combination of two single-gate OFETs: (b) a top-gate OFET (TGOFET) incorporating LiF as the dielectric, and (c) a bottom-gate OFET (BGOFET) employing SiO2 as the dielectric, both sharing common source and drain electrodes. (Reproduced with permission from [38].

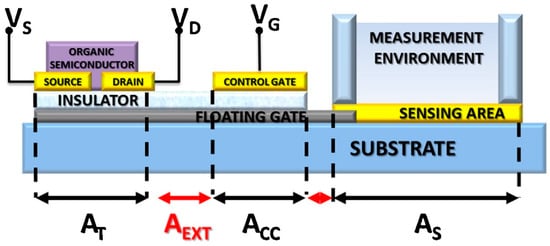

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of a floating-gate OFET architecture. The total floating-gate area (ATOT) comprises the transistor area (AT), the control capacitor area (ACC), and the sensing area (AS), along with the interconnecting extensions (AEXT). Tailoring these geometric contributions enables optimization of the sensing performance of OFET-based biosensors. (Reproduced with permission from [39]).

Extended-gate and dual-gate OFET architectures represent two advanced design strategies with distinct configurations and operational principles for biosensing applications. The extended-gate architecture physically decouples the sensing electrode, functionalized with biorecognition elements, from the organic semiconductor channel. This separation protects the sensitive semiconductor from direct exposure to aqueous media, thereby enhancing operational stability, simplifying biofunctionalization, and favoring biocompatibility and durability in point-of-care or continuous monitoring scenarios. In contrast, dual-gate architectures incorporate a second, independent gate electrode that enables superior electrostatic control over the channel conduction. This design provides significant signal amplification, enhanced transconductance, improved signal-to-noise ratio, and the ability to dynamically tune the sensing response and operational range. However, this comes at the cost of greater fabrication complexity and integration challenges, especially for operation in liquid environments. In practice, extended-gate OFETs are often prioritized for their environmental robustness and reliability in physiological media, whereas dual-gate OFETs are selected for applications demanding the highest analytical sensitivity and electrical tunability.

Floating-gate OFETs, inspired by charge-storage mechanisms in nonvolatile memory devices, provide an intrinsic means of signal integration by temporarily storing charges on an electrically isolated gate. During biomolecular recognition, potential variations induced at the sensing interface modulate the charge state of the floating gate, which in turn alters the channel current in a cumulative and time-dependent manner. This integration of transient electrostatic changes enables continuous and memory-like signal processing, effectively averaging small, stochastic events over time. Such a feature is particularly attractive for nucleic acid sensing, where hybridization events produce subtle potential shifts that benefit from charge accumulation to achieve amplified and stable readouts.

Recognizing the growing demand for POC and wearable diagnostics, significant attention has also been devoted to stretchable and flexible substrates. Materials such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [40], polyimide (PI) [41], and elastomeric composites [42] provide mechanical robustness and conformability, enabling integration of OFET biosensors into textiles, patches, and implantable platforms. Such flexible systems maintain stable electrical performance under repeated bending or stretching, a critical requirement for continuous health monitoring applications.

Complementary to architectural innovations, sophisticated surface functionalization strategies are the cornerstone of tailoring OFET biosensors for the high specificity and selectivity required in clinical diagnostics. These strategies are meticulously engineered to modulate interfacial charge transport while anchoring a diverse array of biorecognition elements. As demonstrated across numerous applications, key approaches include enzymatic immobilization (e.g., using glucose or lactate oxidase within a redox polymer for metabolic biomarkers) [43]; antibody coupling via covalent bonding or innovative platforms like carbon dots for protein biomarkers [44] such as cardiac troponin I, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP); polymer-based interfaces like PEG to enhance sensitivity and reduce fouling [45] for neurological targets like GFAP; and biomimetic membranes for model systems like streptavidin-biotin recognition. These targeted approaches are critical as they not only facilitate the precise immobilization of receptors but also directly enhance device performance by improving signal transduction, biocompatibility, and operational stability in complex biological fluids, all essential attributes for POC and wearable diagnostic applications.

These architectural and interfacial engineering strategies have expanded the operational capabilities of OFET biosensors, bridging the gap between laboratory demonstrations and real-world diagnostic applications. By systematically tailoring device design to specific targets and measurement environments, researchers have achieved substantial improvements in detection limits, response times, and operational stability—parameters critical for clinical translation.

5. Research Methods: Systematic Literature Review

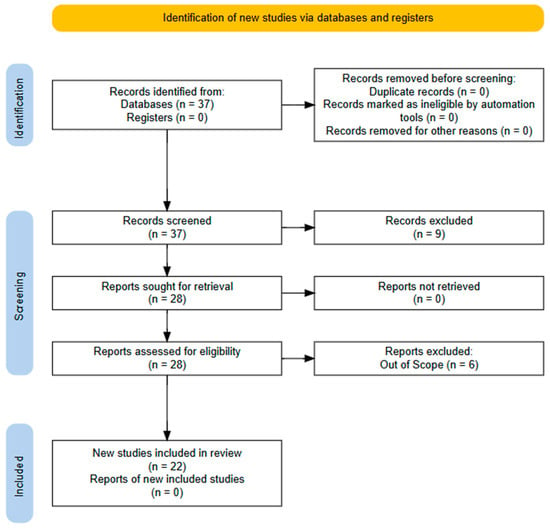

This study conducted a systematic literature review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [46], which are widely recognized for enhancing the transparency, completeness, and accuracy of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The PRISMA methodology [47] outlines a structured approach for identifying documents involving sequential steps: identification, screening, and inclusion based on eligibility quality assessment.

5.1. Identification

The literature search was carried out via the Scopus database [48], which was selected for its extensive coverage of recent and reputable publications across numerous journals. The search string used was “TITLE (“organic field effect transistors” OR ofet AND biosensor)”, which was restricted to the “Article title” field in Scopus. This search yielded an initial set of 37 documents.

5.2. Screening

The 37 identified documents were then subjected to further screening based on predefined criteria: document type (Article), source type (Journal), language (English), and publication stage (Final). The following search string was applied to refine the results:

“TITLE (“organic field effect transistors” OR ofet AND biosensor) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE, “j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO(PUBSTAGE, “final”))”.

This screening process, which was conducted on 4 November 2025, narrowed the list to 28 journal articles for further examination.

5.3. Eligibility

At the eligibility stage, the focus was on selecting journal articles that specifically addressed OFET biosensors for the detection of clinical biomarkers. The titles, abstracts, and full texts of the 28 articles were reviewed closely. Six articles were excluded because they were outside the scope of the study. Ultimately, 22 articles were deemed eligible for further analysis.

5.4. Included Articles and Quality Assessment

A total of 22 articles were retained for the final review. Bibliographic data, including author names, affiliations, article titles, keywords, abstracts, publication years, and journal titles, were extracted from the Scopus (Elsevier) database. As Scopus already ensures the quality of indexed publications, all 22 articles were considered suitable for inclusion in the subsequent analysis and discussion (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Three steps of this systematic literature review following PRISMA, 2020 [10].

6. Clinical Biomarker Applications of OFET Biosensors

6.1. Metabolic and Organ Dysfunction Biomarkers

Metabolic and organ dysfunction biomarkers are vital indicators of pathological conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and renal disorders. OFET-based biosensors offer significant promise for their detection owing to high sensitivity, flexible design, and compatibility with low-cost fabrication. Recent advances have enabled reliable monitoring of key metabolites and proteins, including glucose, lactate, cardiac troponin I, and urea, highlighting their translational potential for wearable and POC diagnostics. As a central metabolic regulator and primary marker for diabetes, glucose provides the logical starting point for this discussion.

6.1.1. Glucose

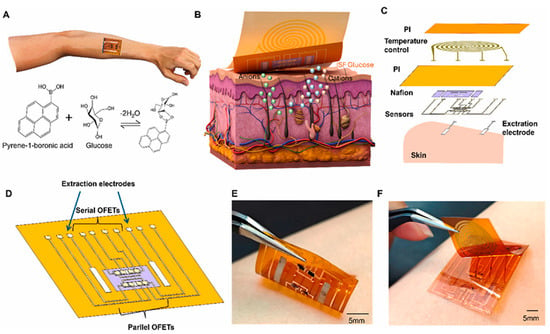

X. Zhang et al. [49] reported that flexible OFET sensors, exploiting the delocalized π-conjugation of organic semiconductors for efficient charge transport, had been investigated for their applicability in glucose monitoring within wearable biomedical platforms. Traditional OFET sensors had exhibited a restricted linear response range, primarily constrained by threshold voltage limitations and saturation current behavior, which impeded their effectiveness in biomarker quantification. To overcome this inherent drawback, the authors demonstrated that the strategic integration of both p-type and n-type OFET channels within a synergistic sensor array effectively broadened the linear response span for glucose detection (Figure 7). Furthermore, the study established that a fully printed fabrication process incorporating a bank-structured architecture ensured reproducibility and uniformity across the device array. In this work, the organic semiconductor layers (P3HT/N2200) were functionalized through a nanostructured interface comprising rGO and Pyrene-1-boronic acid. The pyrene moiety formed strong π–π interactions with the graphene surface, ensuring stable immobilization without disrupting charge transport, while the boronic acid groups acted as selective biorecognition sites through reversible boronate–diol complexation with glucose. The researchers ultimately validated the real-world applicability of the developed technology by implementing a flexible epidermal monitoring platform, thereby confirming the feasibility of continuous glucose sensing in a practical biomedical context.

Figure 7.

(A) Operating principle of OFET-based glucose sensors utilizing boronic acid. (B,C) Schematic representation of the detection system. (D) Structural design enabling a wide linear detection range for glucose. (E,F) Photographic images of the fabricated device. (Reproduced with permission from [49]).

By employing inkjet printing on polymeric films, Furusawa et al. [50] demonstrated an economical fabrication strategy for biosensors, positioning them as promising tools for point-of-care diagnostics. They stated that OFET-based biosensors operated as potentiometric electrochemical devices, and their investigation focused on the detection of glucose and 1,5-anhydroglucitol, which served as diabetes-related biomarkers. In their study, the OFET biosensor integrated with a Prussian blue electrode functionalized with glucose oxidase or pyranose oxidase was employed for monosaccharide recognition. The biorecognition layer was formed by immobilizing glucose oxidase or pyranose oxidase onto the Prussian Blue–carbon electrode using a chitosan matrix, where the enzymes were physically entrapped and electrostatically bound within the film. The Prussian Blue layer functioned as an electron mediator, transducing the enzymatic redox reactions into potential changes that modulated the OFET channel response. It was observed that upon immersion of the enzyme-modified electrodes in glucose solutions, the transfer characteristics of the OFET exhibited voltage shifts in correlation with glucose presence, while in the case of 1,5-anhydroglucitol, such a response was evident only when pyranose oxidase was incorporated. The findings demonstrated that recognition of these saccharides was achieved in an enzyme-specific manner on the printed OFET configuration. Although optimization was acknowledged as necessary to broaden the operational detection range, the plastic-film-based OFET biosensor was envisaged to extend beyond diabetes markers toward diverse biomolecular targets.

Both Zhang et al. [49] and Furusawa et al. [50] demonstrated glucose-responsive OFETs, yet their design philosophies diverge notably. Zhang et al. prioritized dual-channel integration (p–n array) for expanded linearity and flexible wearability, whereas Furusawa et al. focused on printed enzyme-integrated architectures for low-cost point-of-care applications. While both achieved reliable glucose transduction, Zhang’s device emphasized real-time epidermal monitoring, and Furusawa’s approach underlines scalability and enzyme selectivity—illustrating complementary directions in glucose biosensor optimization.

6.1.2. Lactate

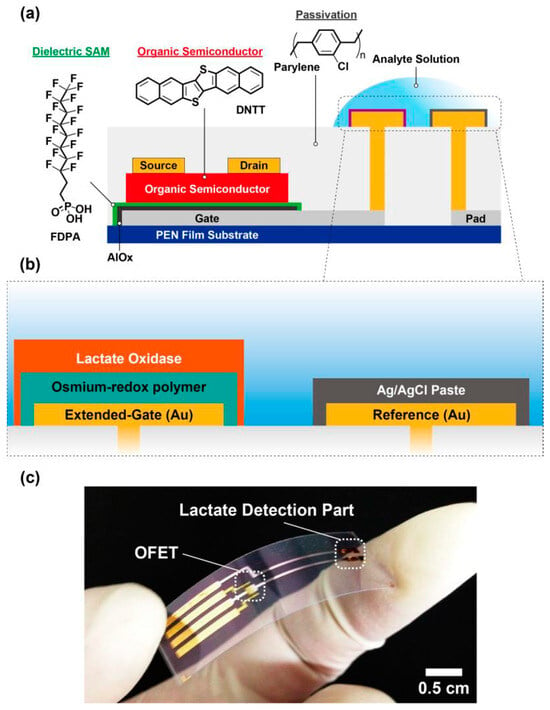

An OFET biosensor capable of discriminating lactate in aqueous media was reported by Minami et al. [51], emphasizing its relevance for biomedical sensing. The device demonstrated an ultra-low detection capability, achieving sensitivity appropriate for practical biosensing applications. They further emphasized that such OFET biosensors could be fabricated on flexible polymer substrates through cost-effective printing processes, making the system adaptable for large-area and portable sensing platforms. Their study introduced an extended-gate configuration in which the electrode was functionalized with lactate oxidase and horseradish peroxidase embedded within an osmium-based redox polymer matrix, thereby facilitating the enzymatic redox conversion of lactate. In this configuration, the biorecognition elements were immobilized on the gold extended-gate surface via glutaraldehyde cross-linking within the osmium– horseradish peroxidase polymer film, forming a stable enzyme–polymer composite. This indirect functionalization ensured efficient electron transfer between the enzymatic reaction and the OFET channel, while preserving the structural integrity of the organic semiconductor. The biosensor exhibited reliable selectivity and sensitivity, validating its suitability for enzyme-assisted electrochemical sensing. The findings highlighted that extended-gate OFET architectures presented a viable route for developing flexible, low-cost biosensors for lactate detection, emphasizing the potential of organic electronic devices in biomedical diagnostics.

Minamiki et al. [52] reported the development of a flexible biosensing platform employing OFETs for lactate detection (Figure 8). Lactate, being a significant metabolic biomarker for evaluating physiological performance, was targeted in their study as an indicator of health monitoring. The device was designed with a low-voltage operating capability and incorporated an extended-gate functionalized with lactate-specific enzymes and an osmium-based redox mediator to facilitate efficient signal transduction. Here, the organic semiconductor was indirectly functionalized by attaching biorecognition elements to an extended-gate electrode modified with lactate oxidase and a horseradish peroxidase–osmium redox polymer complex. The enzymes were immobilized within the polymer matrix via cross-linking, forming a stable conductive film that mediated electron transfer during the enzymatic oxidation of lactate, thereby modulating the OFET channel current for selective and reproducible lactate detection. This configuration enabled stable and continuous monitoring of lactate concentration under physiologically relevant conditions. The findings highlighted that such a strategy could broaden the applicability of OFETs in the design of next-generation wearable biosensing technologies.

Figure 8.

(a) Schematic illustration of the fabricated OFET biosensor. (b) Enlarged view of the sensing region. (c) Photograph of the completed device. (Reproduced with permission from [52]).

The lactate OFET studies by Minami et al. [51] and Minamiki et al. [52] both rely on enzyme-mediated redox coupling but differ in device configuration and operational voltage. The former utilized an osmium-based redox matrix to enable high selectivity in aqueous solutions, while the latter optimized low-voltage, extended-gate structures for wearable integration. These studies demonstrate a clear progression from proof-of-concept biochemical sensing toward practical physiological monitoring.

6.1.3. Cardiovascular Troponin I

Cardiovascular disorders have long been established as the leading cause of mortality worldwide, as noted by Ali et al. [53]. Among the critical diagnostic indicators for myocardial infarction, cardiac troponin I was identified as a regulatory protein that entered the bloodstream upon myocardial injury. Considerable research efforts have been directed toward creating biosensing systems with enhanced sensitivity for its detection. In this context, field-effect transistor-based configurations, particularly those employing organic semiconductors, were found suitable for recognizing such cardiac proteins. The study presented by the authors involved the design and detailed characterization of an OFETs integrating polyaniline nanofibers for biosensing purposes. In this work, the organic semiconductor comprising polyaniline nanofibers was functionalized through covalent immobilization of cardiac troponin I antibodies using a carbodiimide coupling reaction (EDC/NHS chemistry). This process activated the carboxyl groups on the antibodies, enabling amide bond formation with the amine groups of PANI, resulting in strong and stable attachment, which enhanced the robustness and specificity of the sensing interface. Structural and surface modifications of the sensing interface were validated using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy following antibody immobilization. Furthermore, the sensor’s functional response was systematically assessed by monitoring drain current variations in relation to different levels of cardiac troponin I. The fabricated device demonstrated remarkable detection capability with ultralow threshold limits, stable power operation, and consistent performance across repeated trials under variable electrical conditions, highlighting its promise for reliable clinical biomarker monitoring.

6.1.4. Urea Hydrolysis

Utsumi et al. [54] reported the fabrication of OFETs for biosensing applications, specifically targeting the detection of urea hydrolysis catalyzed by urease. In their study, a thin film of 2,6-diphenylanthracene was employed to construct a p-channel transistor that successfully transduced the enzymatic reaction into an electrical response. The transfer characteristics of the device revealed a marked enhancement in drain current when a phosphate buffer containing urea and urease was introduced on a separate sensing electrode, demonstrating that the hydrolytic process directly influenced the gate potential and thereby modulated the channel current. The incorporation of a high-k zirconium oxide dielectric further improved the device performance by lowering the gate voltage required for operation. Time-dependent and concentration-dependent measurements indicated that the drain current rapidly increased and stabilized, signifying the sensor’s high responsiveness to substrate availability. To extend the concept, a complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor inverter was fabricated using 2,6-diphenylanthracene as the p-channel material and N,N′-di-n-octyl-3,4,9,10-perylenetetracarboxylic diimide as the n-channel counterpart, enabling logical signal transduction of urea hydrolysis. The threshold voltage of the inverter shifted upon exposure to the enzymatic reaction, confirming the modulation of the electronic response. Furthermore, a ring oscillator composed of cascaded inverters was realized, and its oscillation frequency was observed to decrease significantly during the reaction, providing an unequivocal indication of hydrolytic activity. According to the researchers, these findings represented a pioneering step toward developing practical biosensors that integrate CMOS inverters and ring oscillators for biochemical detection. The study employed an indirect gate-electrode functionalization approach, wherein the biorecognition occurred on a separate sensing gate coated with a high-k zirconium oxide dielectric and parylene layer, avoiding direct modification of the organic semiconductor. The urease–urea reaction produced hydroxide ions that altered the local pH and gate potential, electrostatically modulating the device current and threshold voltage. This indirect strategy preserved the intrinsic transport properties of the organic semiconductor while ensuring a stable and reversible biosensing interface.

6.1.5. Multiplexed Detection

Zhao et al. [55] reported the development of skin-conformal, drift-free biosensing devices based on deformable diode-integrated OFETs. Their strategy utilized capacitive coupling in conjunction with differential signal processing, achieved through dual extended gates individually modified with specific target and reference bioreceptors. In this approach, the DPPTT was indirectly functionalized through an extended-gate structure, ensuring that the organic semiconductor layer remained encapsulated and chemically isolated from the biological medium. Biorecognition elements, including thiol-terminated aptamers, glucose oxidase/Prussian blue, and ion-selective membranes were immobilized on Au nanoparticle-coated CNT extended gates, serving as the active biochemical interfaces. This configuration effectively minimized signal distortion by several orders of magnitude relative to conventional organic transistors lacking diode connection, even when subjected to environmental and mechanical fluctuations such as electrical bias instability, tensile deformation, compressive force, and thermal variation. The methodology was successfully demonstrated for multiple biochemical detection modalities, including aptamer-mediated cortisol recognition, enzyme-assisted glucose detection, and ion-selective membrane-based sodium ion measurement. Furthermore, a comprehensive wearable platform was established by integrating the soft sensor array with a flexible electronic interface capable of wireless communication with a mobile application, enabling real-time cortisol monitoring in perspiration under physiologically induced stress conditions.

6.2. Cancer and Tumor Biomarkers

Cancer and tumor biomarkers play a pivotal role in early diagnosis, therapeutic monitoring, and prognosis, where sensitivity and reliability of detection are crucial. OFET-based biosensors have gained attention for this purpose due to their ability to transduce biomolecular interactions into stable electrical signals with high selectivity and low-cost fabrication potential. Among these, CEA and AFP are widely studied as representative tumor-associated biomarkers, forming the focus of this section.

6.2.1. Carcinoembryonic Antigen

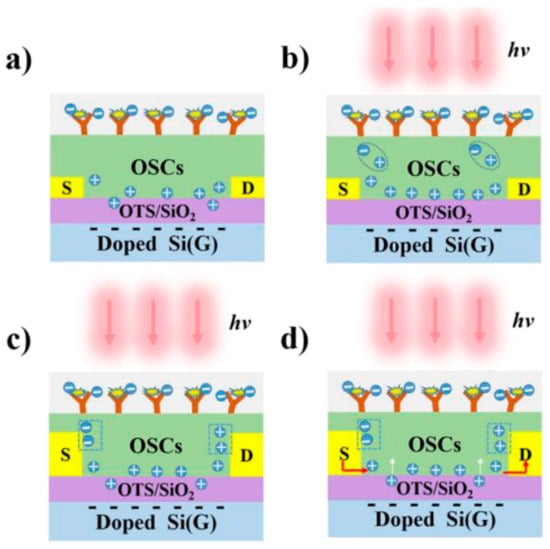

The development of biosensors with improved sensitivity and reliability is regarded as essential for early diagnosis and therapeutic management of tumor-associated disorders, as highlighted by Wang et al. [56]. In this context, they developed an OFET-based biosensor and employed it for the detection of CEA. The device demonstrated the capability to transduce the antigen–antibody interaction into distinct electrical responses under both illuminated and dark conditions, reflected by variations in source–drain current and threshold voltage (Figure 9). Under photo-irradiation, the incident light modulated the charge-carrier dynamics within the conductive channel, thereby amplifying the photocurrent and voltage responses relative to those obtained in darkness. Such photo-induced enhancement endowed the system with superior sensitivity compared to dark-state measurements. Furthermore, the integration of multisignal output modes contributed to improved detection reliability. The researchers functionalized the OFET by using PDQT as both the semiconducting and biorecognition layer. The PDQT film on an OTS-treated SiO2/Si substrate enabled direct physical adsorption of the CEA antibody without chemical linkers, preserving charge mobility and device stability. Antigen binding modulated source-drain current and threshold voltage, while illumination-generated photocarriers amplified the signal, yielding femtomolar sensitivity through a simple, robust functionalization approach. On account of its strong analytical performance, this OFET-based biosensor was proposed as a promising high-performance platform for the sensitive and reliable detection of diverse biomolecular targets.

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration of the operating mechanism of the OFET-based biosensor under dark and illuminated conditions. (a) Detection principle of the OFET-based biosensor for CEA in the absence of light. (b) Generation of photogenerated charge carriers in the OFET-based biosensor under light irradiation. (c) Migration of these photogenerated carriers within the applied electric field. (d) Detection mechanism of the OFET-based biosensor for CEA under illumination (light intensity: 2.13 mW cm−2, wavelength: 808 nm). (Reproduced with permission from [56]).

Y. Zhang et al. [30] reported that OFETs had been increasingly recognized as versatile candidates for biosensing, yet the primary challenge resided in tailoring functionalization strategies at the sensing interface to facilitate the recognition of trace-level proteins while sustaining overall device stability. To address this limitation, they devised an extended-gate OFET functionalized with carbon dots bearing thiol, amino, and carboxyl groups. The thiol moieties covalently bonded to the gold surface via Au–S self-assembly, while the residual carboxyl and amino groups enabled covalent immobilization of anti-CEA antibodies. This dual-functional surface provided high probe density, stable binding, and uniform orientation without affecting the organic semiconductor performance. The integration was achieved by exploiting the advantageous properties of carbon dots, including their ease of synthesis, structural tunability, nanoscale dimensions, and economic feasibility, which collectively facilitated their efficient deposition on the electrode surface. By utilizing the reactive functional moieties present on the carbon dot surface, the system enabled covalent immobilization of low-abundance proteins without impairing the electrical characteristics of the transistor. As a result, the fabricated biosensor demonstrated an ultrasensitive response with superior selectivity toward CEA, highlighting the pivotal role of carbon dots in enhancing biosensor performance and affirming their promise for early-stage cancer diagnostics.

The studies by Wang et al. [56] and Y. Zhang et al. [30] on CEA sensing highlight complementary approaches, i.e., photo-enhanced amplification versus nanocarbon interface engineering. Wang’s photoactive OFET achieved light-induced current amplification to boost sensitivity, while Zhang’s carbon-dot functionalization improved protein capture and device stability under ambient conditions. These contrasting strategies depict how both optical modulation and nanostructured interface design can substantially enhance tumor marker detection.

6.2.2. Alpha-Fetoprotein

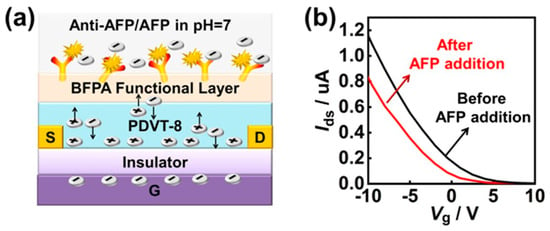

Enhanced responsivity and sensitivity were identified by Jiang et al. [57] as fundamental parameters determining the performance of OFET-based biosensors, particularly in disease diagnostics. However, they noted that designing devices capable of simultaneously improving these properties while remaining cost-effective, easily processable, and time-efficient posed a significant scientific challenge. To address this, they introduced an innovative OFET biosensor incorporating a copolymer thin film whose surface was subjected to optical illumination. Functionalization of the organic semiconductor layer was achieved through physical adsorption of antibodies onto the PDBT-co-TT film. The polymer’s hydrophobic and π-conjugated structure enabled stable non-covalent immobilization without hindering charge transport, while antigen binding modulated carrier mobility and current, ensuring selective and highly sensitive detection with preserved photoresponsivity. The film functioned dually as an organic semiconducting medium and as a photoactive layer, thereby enabling signal amplification through its pronounced photo-response. Consequently, the biosensor exhibited superior responsivity and sensitivity under illuminated conditions compared to dark operation, which facilitated highly efficient detection of AFP. This integration of optical excitation with transistor operation was described as a crucial link between the photoelectric effect and biological sensing. Furthermore, they suggested that the continuous development of advanced photoactive organic materials would potentially open new avenues toward highly sensitive biochemical diagnostic technologies.

Sun et al. [58] reported that OFETs had been recognized as promising low-cost biosensing platforms due to their rapid response and ability to simultaneously probe multiple parameters. They emphasized that conventional functionalization strategies on organic devices often compromised device stability and sensitivity, thereby limiting their reliability for advanced diagnostic applications. To overcome these challenges, they designed a novel organic material, 2,6-bis(4-formylphenyl)anthracene, which served as a protective and functional interfacial layer in OFET-based biosensors (Figure 10). This approach enabled ultrasensitive identification of AFP in human serum with exceptional precision. Functionalization of organic semiconductors in OFET biosensors was achieved by introducing reactive interfaces for stable biomolecule attachment. Researchers used 2,6-bis(4-formylphenyl)anthracene as a protective and functional layer on PDVT-8 films, whose aldehyde groups covalently bound AFP antibodies via Schiff base formation. This functionalization ensured robust immobilization, reduced nonspecific adsorption (ethanolamine-capped), and preserved charge transport. Through modulation of source–drain current and threshold voltage characteristics, the fabricated biosensor demonstrated enhanced stability in biomarker detection and effectively distinguished liver cancer cases from healthy subjects. The device further offered the benefits of label-free analysis, reduced assay duration, and minimal sample consumption. Compared with established clinical immunoassay techniques, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, the developed OFET biosensor provided a superior alternative with significant potential for early-stage liver cancer diagnostics.

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the OFET-based biosensor mechanism. (a) Model illustrating immune detection of the AFP biomarker diluted in 1× PBS at pH 7. (b) Variations in Ids and Vth electrical signals in response to 1 μg/mL AFP biomarker. (Reproduced with permission from [58]).

For AFP detection, Jiang et al. [57] utilized photoactivated polymer films for signal amplification, whereas Sun et al. [58] employed chemically engineered anthracene derivatives for interface stabilization and label-free serum analysis. Jiang’s approach maximized optical gain, ideal for controlled laboratory testing, while Sun’s strategy offered superior robustness and clinical practicality. Together, they exemplify the trade-off between photonic enhancement and structural stability in OFET cancer biosensors.

6.3. Neurological and Inflammatory Biomarkers

Neurological and inflammatory biomarkers are crucial for diagnosing and monitoring disorders of the central nervous and immune systems, where early detection can significantly influence clinical outcomes. OFET-based biosensors have shown strong potential in this domain, offering high sensitivity, label-free operation, and compatibility with complex biological samples. Representative examples include glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), myelin basic protein (MBP), and inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, which are explored in this section.

6.3.1. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP)

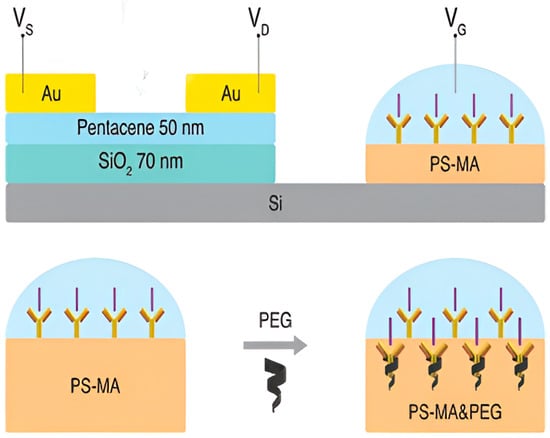

The development of an OFET-based biosensor for label-free recognition of GFAP was described by Song et al. [59]. The work demonstrated, for the first time, the implementation of an extended solution-gated architecture in which the active sensing region was physically isolated from the organic semiconductor, thereby eliminating the necessity of an external reference electrode (Figure 11). Functionalization of organic semiconductors was achieved by EDC/NHS activation of carboxyl groups on a PS-MA polymer layer, enabling covalent immobilization of anti-GFAP antibodies. The immobilized antibodies specifically bound GFAP antigens, and the resulting charge interactions modulated the drain current. Polyethylene glycols of varying molecular weights were incorporated into the biorecognition interface, which facilitated the extension of the Debye screening length. It was observed that higher molecular weight polyethylene glycols markedly enhanced the modulation of drain current, a phenomenon attributed to their ability to diminish the dielectric constant. Furthermore, the sensing behavior was systematically examined under varied gate bias conditions, revealing that reduced gate potential enhanced sensitivity, as the applied bias approached the intrinsic threshold of the transistor, thereby amplifying the effect of bound negatively charged proteins. Selectivity assays against potential interferents were also conducted, establishing both the specificity and stability of the biosensor. The outcomes highlighted the potential clinical relevance of the proposed system.

Figure 11.

Architecture of the extended-gate solution-based OFET device. (Reproduced with permission from [59]).

6.3.2. Myelin Basic Protein (MBP)

Song et al. [60] reported that OFET-based biosensors functionalized with antibody receptors had been extensively explored for the recognition of protein antigens, yet systematic comparisons of matrix polymers used for antibody immobilization had not been undertaken. In their investigation, acrylic copolymers were employed as receptor interfaces, utilizing MBP and its complementary antibody as a representative antigen–antibody system. The receptor layers were critically examined for their robustness under repeated washing procedures and for their ability to immobilize antibodies on device substrates through conjugation with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled antibodies. Functionalization of the organic semiconductor surface was accomplished using carboxyl-rich acrylic copolymers such as PS-MA, PS-PAA, PMMA-MA, and PDLLA-PAA. The carboxyl groups were activated via EDC/NHS chemistry to form covalent amide linkages with antibody amines, enabling stable and selective biorecognition. Among these, PS-MA exhibited superior antibody retention and sensing performance owing to its balanced hydrophobicity, carboxyl group density, and film stability. Furthermore, electronic responses and antigen-specific selectivity were demonstrated, thereby validating the functional performance of the devices. The study ultimately offered design insights into optimizing bioreceptor layer composition to enhance both sensitivity and operational stability in OFET biosensing platforms.

6.3.3. Inflammatory Cytokine TNFα

The centrality of biorecognition in living systems, along with its broad application in biomedical and technological fields, was highlighted by Berto et al. [61]. In their study, they demonstrated that the EGOFET functioned as an ultrasensitive and highly specific platform for probing the thermodynamics of biomolecular recognition between human antibodies and their target antigen, the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα, at the solid–liquid interface. Researchers functionalized the organic semiconductor interface to enable the covalent immobilization of antibodies while preserving their biological activity. Surface activation was achieved through carboxyl-terminated layers and carbodiimide (EDC/NHS) coupling chemistry, which promoted stable amide bond formation between the organic semiconductor surface and antibody amine groups. The biosensor displayed a non-linear amplification response at extremely low analyte concentrations, achieving ultra-low detection thresholds. The device sensitivity was shown to be dependent on the analyte level, with optimal performance observed under physiologically significant TNFα conditions when the transistor operated in the subthreshold regime. At higher antigen concentrations, the signal followed a linear dependence on concentration, while the overall sensitivity and operational dynamic range were modulated by the applied gate potential. This behavior was rationalized through the established correlation between sensor sensitivity and the density of states of the organic semiconductor, where the non-linear response was attributed to the energy distribution at the tail of the HOMO level. Analysis of the voltage-dependent response further enabled the extraction of binding constants, surface charge alterations, and effective capacitance variations associated with antibody–antigen interactions at the electrode interface. Ultimately, researchers confirmed the applicability of this biosensing strategy by detecting TNFα in plasma-derived samples, highlighting its potential utility in POC diagnostics.

6.4. Infectious Disease and Protein Recognition

Infectious disease biomarkers and protein–ligand recognition events are vital for rapid diagnostics, epidemiological monitoring, and therapeutic decision-making. OFET-based biosensors offer unique advantages in this domain through their ability to achieve high sensitivity, selective detection, and compatibility with scalable, flexible device fabrication. This section highlights representative applications, including those involving HIV, SARS-CoV-2 antigens and antibodies, as well as model protein systems such as streptavidin–biotin and avidin interactions.

6.4.1. HIV

Sailapu et al. [62] demonstrated a self-sustained sensing platform based on an EGOFET, which functioned without external power sources by deriving energy directly from the analyzed medium, thereby simulating a blood-like sample. The device incorporated a biofuel cell-based energy harvesting unit integrated with a smart interfacing circuit that enabled stable operation of the transistor sensor and facilitated simplified signal readout. The sensing mechanism relied on the bio-recognition of the HIV-1 p24 capsid protein at the gate electrode functionalized with specific antibodies, which was subsequently transduced into an electrical response by the EGOFET. The P3HT-based EGOFET was functionalized by forming a self-assembled monolayer (chem-SAM) on the gold gate for covalent immobilization of anti-HIV-1 p24 antibodies, followed by BSA blocking to prevent nonspecific binding. The platform exhibited high sensitivity, capable of detecting antigen concentrations at levels appropriate for early-stage HIV-1 diagnosis, thereby addressing the limitations of conventional POC systems that often failed to satisfy the ASSURED criteria [63]. Through this approach, the researchers established a cost-effective and portable diagnostic tool with minimal components, providing a feasible route toward decentralized testing with single-molecule resolution and robust performance, particularly in resource-limited settings.

6.4.2. SARS-CoV-2

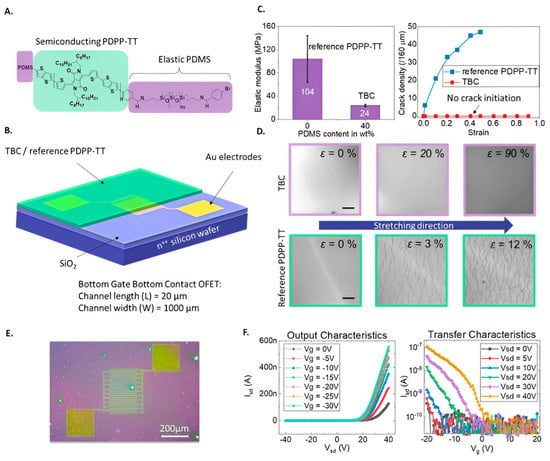

The critical role of adaptable diagnostic methods in enabling timely decision-making and managing large-scale health challenges during COVID-19 was noted by Ditte et al. [64]. They emphasized that while conventional SARS-CoV-2 detection approaches provided reliability, their integration into wearable platforms remained unfeasible for on-demand applications. To address this limitation, an OFET-based biosensor was developed for the detection of both SARS-CoV-2 antigens and corresponding antibodies within a short response period. The device was fabricated by functionalizing an intrinsically stretchable semiconducting triblock copolymer film with either anti-S1 antibodies or the receptor-binding domain of the S1 protein, thereby enabling selective recognition of viral antigens and antibodies (Figure 12). The organic semiconductor surface was functionalized through EDC/NHS coupling chemistry, activating carboxyl groups to enable covalent attachment of antibodies via amide bond formation with their amine groups. This stable and oriented immobilization of the biorecognition elements ensured high specificity and preserved the semiconductor’s electronic performance for efficient biosensing. The platform design was facilitated by the straightforward preparation of the triblock copolymer and the adoption of physical adsorption as an efficient immobilization strategy. The biosensor exhibited remarkable sensitivity and ultra-low detection limits for both viral antigens and antibodies, demonstrating its effectiveness as a dual-mode sensing system. The triblock copolymer employed as the active layer possessed a low elastic modulus and exceptional stretchability without compromising film integrity, making it suitable for integration into flexible diagnostic devices. Furthermore, its compatibility with scalable roll-to-roll printing underlined the potential for cost-effective production of wearable or skin-mounted POC testing systems.

Figure 12.

Fabricated BGBC OFET and polymer mechanical properties. (A) Chemical structure of TBC with 40 wt% PDMS: light-green = semiconducting PDPP-TT, purple = elastic PDMS end-caps. (B) BGBC device layout (Fraunhofer OFET Gen4, 230 nm SiO2) with TBC or reference PDPP-TT spin-coated on Au electrodes (L = 20 μm, W = 1000 μm). (C) Left: elastic modulus via nanoindentation; right: crack onset strain under tension. (D) Optical images of strained TBC (top, scale = 20 μm) and PDPP-TT (bottom, scale = 50 μm). (E) TBC OFET micrographs. (F) Representative electrical characteristics. (Reproduced with permission from [64]).

6.4.3. Streptavidin

Mulla et al. [65] reported a facile and efficient wet chemical approach for introducing carboxyl functionalities onto organic semiconductor films. In this method, a poly(acrylic acid) layer was directly deposited on the electronic channel of an EGOFET and subsequently cross-linked under ultraviolet irradiation without requiring any additional photo-initiator. The introduced carboxyl groups provided reactive sites for covalent coupling with the amino groups of phosphatidyl-ethanolamine, thereby enabling the stable immobilization of phospholipid bilayers. Functionalized phospholipids carrying recognition moieties were incorporated into the membranes to extend the platform’s capability for bio specific interactions. The PBTTT surface was functionalized with a UV-crosslinked poly(acrylic acid) layer bearing carboxyl groups, enabling EDC/NHS-mediated covalent attachment of biotinylated vesicles. Subsequent streptavidin binding provided a selective bio-interface, achieving stable, aqueous-compatible functionalization without compromising organic semiconductor performance. As a representative case, biotinylated phospholipids were utilized to enable selective recognition of streptavidin at the electronic interface. The morphological evolution and chemical state of the functionalized surfaces were systematically examined through scanning electron microscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy throughout the biofunctionalization sequence. Furthermore, the electrical response and sensing behavior of the fabricated devices were investigated, demonstrating high sensitivity and selective detection of streptavidin at concentration levels significantly lower than those typically achieved by conventional surface plasmon resonance assays.

EGOFET has been described as a robust and versatile platform for ultrasensitive, rapid, and reliable biomolecule detection in aqueous environments using cost-effective bioelectronic devices, as reported by Poimanova et al. [66]. They emphasized that the critical functional architecture of these systems consisted of semiconducting and biorecognition layers composed of conjugated organic compounds, which required exceptional stability under diverse electrolyte conditions during analyte detection. In their study, devices incorporating 2,6-dioctyltetrathienoacene as the semiconducting medium were produced via a doctor blade technique compatible with scalable printing approaches. Furthermore, EGOFETs incorporating a biorecognition layer derived from a biotin-functionalized [1]benzothieno [3,2-b]benzothiophene derivative were fabricated using the Langmuir–Schaeffer deposition method. The biotin sites enabled selective streptavidin binding through strong biotin–streptavidin affinity, forming a stable biorecognition interface without impairing the semiconductor’s electronic performance. Their findings demonstrated that the developed devices sustained reliable operation in a range of electrolyte environments and exhibited distinct sensing responses toward electrolyte pH variations as well as the specific interaction with streptavidin.

Both Mulla et al. [65] and Poimanova et al. [66] employed EGOFET configurations for streptavidin sensing, yet their fabrication philosophies differ significantly. Mulla et al. achieved covalent surface functionalization via photochemically cross-linked polymers, while Poimanova et al. emphasized scalable film deposition and electrolyte tolerance. The former demonstrated molecular-level immobilization precision; the latter prioritized environmental robustness, together showcasing the adaptability of OFET chemistry to diverse sensing environments.

6.4.4. Biotin

Picca et al. [31] reported the development of functional bio-interlayer OFET biosensors, where PSS-stabilized ZnO nanoparticles were incorporated within the streptavidin interfacial layer to enhance long-term operational stability. The devices embedding ZnO nanoparticles maintained their sensing efficiency for extended durations, whereas P3HT/streptavidin counterparts exhibited resistive degradation over time that hindered sensing performance. Electrical measurements combined with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy confirmed that the ZnO nanoparticles played a protective role by mitigating the structural and electronic degradation of the P3HT active layer. Furthermore, the nanoparticles acted as a humidity-capturing medium, thereby prolonging device lifetime. For proof-of-concept, streptavidin was employed as the recognition element for biotin detection, while poly(3-hexylthiophene) served as the semiconducting channel. ZnO nanoparticles were synthesized and incorporated into the device architecture through a simple spin-coating route in which a suspension of streptavidin–ZnO nanoparticles was deposited on the dielectric substrate, followed by the casting of a P3HT film. The complete fabrication process was achieved within a short time frame. The integration of ZnO nanoparticles not only imparted remarkable environmental stability, sustaining performance well beyond the timespan of nanoparticle-free devices, but also substantially improved charge carrier mobility without compromising biosensing capability. The combined structural and electronic analyses provided mechanistic insights into the stabilizing effect of ZnO nanoparticles on the organic semiconductor, thereby highlighting their critical role in ensuring device robustness and durability. The organic semiconductor surface was functionalized through a biotin–streptavidin affinity-based strategy. A biotinylated pentathiophene derivative was deposited onto the OFET channel, providing biotin sites for specific streptavidin binding, which served as an anchoring layer for biotinylated antibodies. This sequential assembly yielded an ordered and selective bio-interface formed entirely via non-covalent yet highly specific interactions.

6.4.5. Avidin

The development of biotin-modified fluorene–bithiophene copolymers for use in organic thin-film transistor biosensors was demonstrated by Kim et al. [67]. In their approach, the fluorene side chains were selectively biotinylated following esterification of biotin with the hydroxyl groups present in the polymer backbone. The resulting material was evaluated as an organic semiconductor using a thin-film transistor platform and demonstrated characteristic p-type behavior. The biosensing capability was validated through the detection of biologically relevant molecules, where the presence of avidin, in contrast to bovine serum albumin, induced a selective reduction in transistor conductivity in the fabricated device. Biotin functionalization of the organic semiconductor F8T2 was achieved via esterification of biotin with the polymer’s side-chain alcohol groups, following Suzuki coupling synthesis. Partial substitution (10–25%) introduced biorecognition sites enabling specific biotin–avidin interactions. Upon avidin binding, structural perturbations in the conjugated backbone led to marked decreases in charge mobility and fluorescence shifts, demonstrating effective electronic and optical transduction for biosensing applications. Furthermore, alterations in the optical response of the polymer were observed, evidenced by modifications in UV-fluorescence emission following interaction with avidin or bovine serum albumin.

6.5. Nucleic Acid and Environmental/Chemical Targets

Beyond clinical biomarkers, OFET-based biosensors have also been extended to nucleic acids and environmental or chemical analytes, broadening their diagnostic and monitoring potential. Their adaptability allows precise recognition of DNA sequences as well as detection of small molecules relevant to food quality and environmental health. This section discusses applications such as DNA hybridization assays and enzymatic sensing of trimethylamine as a marker of fish freshness.

6.5.1. DNA Hybridization Detection

Lai et al. [39] reported a strategy for engineering OFET architectures with tunable sensing characteristics. In their investigation, a specific configuration termed the Organic Charge-Modulated Field-Effect Transistor (OCMFET) was critically analyzed and modeled to surpass mere phenomenological interpretations of biochemical interactions and to quantitatively define its detection efficiency. The researchers functionalized organic semiconductors by introducing carboxylic acid groups onto the polymer backbone using 3-thiopheneacetic acid during polymerization, yielding a COOH-functionalized poly(3-alkylthiophene). These carboxyl groups were then activated using EDC/NHS coupling chemistry to covalently attach amine-containing biorecognition elements such as GOx. Through rigorous evaluation, the authors established the correlation between geometrical parameters and biosensing response, which enabled the formulation of explicit design principles. Guided by these principles, a device optimized for nucleic acid recognition was fabricated and subjected to detailed electrical assessment. The optimized sensor demonstrated unprecedented sensitivity and selectivity in detecting DNA hybridization, thereby establishing benchmark performance metrics. Importantly, the sensing mechanism of the OCMFET was shown to be independent of the nature of the employed semiconductor, indicating that the proposed methodology could be universally extended to alternative semiconducting systems and thus providing a foundation for the development of advanced bioelectronic platforms across diverse material classes.

6.5.2. Trimethylamine

An enzymatic OFET biosensor engineered for trimethylamine detection as an indicator of fish freshness was developed by Diallo et al. [68]. The device was fabricated on a Kapton substrate incorporating pentacene as the organic semiconducting layer, while Parylene-C served as the top-gate dielectric. A proton-sensitive interface was established by depositing a hydrogenated silicon nitride film on Parylene under moderate thermal conditions. The researchers functionalized the OFET by depositing a SiN:H layer on Parylene-C via UV-assisted CVD to create a proton-sensitive surface. The biorecognition element, flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3), was cross-linked with bovine serum albumin using glutaraldehyde vapor to form an enzymatic membrane on the SiN:H layer, enabling selective trimethylamine detection through enzyme-catalyzed proton generation. The fabricated biosensor exhibited pronounced responsiveness toward trimethylamine, confirming its capability for highly sensitive detection.

From the above discussion, it can be inferred that extended-gate and electrolyte-gated configurations—offer significant merits over direct organic semiconductor functionalization by physically and electrically decoupling the sensitive organic semiconductor channel from the biorecognition interface. This strategic separation preserves the intrinsic charge transport properties and molecular packing of the semiconductor by shielding it from disruptive chemical modifications, direct ion penetration, moisture-induced degradation, and biofouling in aqueous environments. The gate electrode provides a more robust and versatile platform for immobilizing diverse bioreceptors on metal or metal oxide surfaces, enabling greater reproducibility, uniformity, and the potential for regeneration of the sensing layer without altering the core transistor characteristics. Consequently, this design mitigates signal drift, reduces operational variability and noise, and improves transduction efficiency, leading to enhanced sensitivity, operational stability, and device longevity. By maintaining reliable performance in complex physiological media such as serum, plasma, and sweat, gate-functionalized OFETs directly address key hurdles in clinical translation, offering a more practical and resilient platform for point-of-care and wearable biosensing applications compared to organic semiconductor -functionalized systems.

The key specifications and performance metrics of the OFET biosensors discussed above are consolidated in Table 1 for comparative reference.

Table 1.

Summary of representative OFET biosensors, detailing device substrates, electrode and semiconductor configurations, biorecognition elements, and key performance metrics for clinical biomarkers and environmental targets.

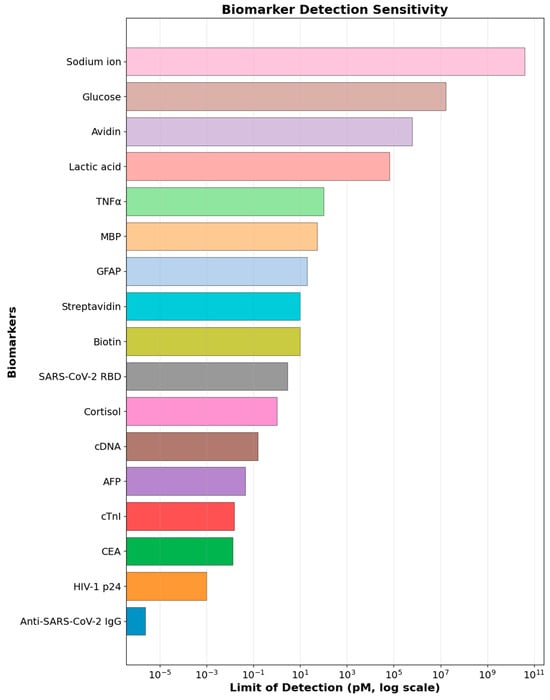

Table 1 summarizes representative OFET-based biosensors developed for diverse biomarkers, illustrating how substrate composition, electrode configuration, and receptor–semiconductor coupling dictate analytical performance. While several parameters remain NR (not reported), this largely reflects variations in characterization focus rather than data absence, highlighting the lack of standardized reporting protocols across studies. Among the consistently reported parameters, the LOD and linear detection range emerge as the most clinically relevant indicators. The comparative analysis of detection limits (Figure 13) reveals a distinct hierarchy in OFET biosensor performance: immunological and cancer-related biomarkers such as CEA, AFP, and HIV-1 p24 exhibit exceptional sensitivity in the femtomolar range, enabled by antibody-functionalized interfaces and efficient charge transport in optimized organic semiconductors. Neurological, cardiac, and inflammatory proteins display intermediate detectability, balancing recognition specificity with charge-screening management in complex biofluids. In contrast, small-molecule metabolites and ions such as glucose, lactate, and sodium require much higher concentrations for detection, reflecting intrinsic limitations in transducing low-molecular-weight, weakly charged species via label-free electronic mechanisms. This broad sensitivity gradient—spanning from femtomolar to millimolar levels—not only maps the current technological landscape of OFET biosensing but also highlights persistent data gaps and methodological diversity that must be addressed for cross-platform benchmarking and clinical translation toward a unified, high-performance biosensing paradigm.

Figure 13.

Limits of detection (LOD) for various biomarkers span over sixteen orders of magnitude, from femtomolar to millimolar levels, reflecting wide variation in analytical sensitivity across analyte classes.

Across the examined biomarker classes, OFET biosensors demonstrate clear trends linking device architecture, interfacial chemistry, and analytical performance, with distinct implications for clinical relevance and validation maturity. Comparative evaluations reveal that multi-channel and photoactive OFETs, as employed in glucose and AFP sensing, deliver superior signal amplification, while enzyme-integrated and hybrid nanoparticle systems—exemplified by lactate and biotin detection—enhance stability and selectivity under physiological conditions. Interface-engineered OFETs incorporating nanocarbon or inorganic composites also outperform conventional organic counterparts in long-term operation and reproducibility, particularly for tumor and protein biomarkers such as CEA and streptavidin.

Correspondingly, clinically aligned performance has been demonstrated in select cases: glucose sensors operate within the micromolar–millimolar range, matching physiologically relevant blood glucose levels (≈3.9–11 mM) [69], and lactate sensors achieve comparable sensitivity for sweat (4–25 mM) and blood (0.6–2 mM) [70]. For cardiac biomarkers, the cTnI sensor achieves an impressive LOD of 0.36 pg/mL, which surpasses the clinical decision limit for myocardial infarction (typically 10–50 pg/mL for high-sensitivity assays) [71]. Similarly, cancer biomarker sensors for CEA and AFP demonstrate detection limits in the fg/mL to pg/mL range, meeting or exceeding the clinical thresholds for early cancer detection (CEA: ~3–5 ng/mL for colorectal cancer [72]; AFP: ~10–20 ng/mL for liver cancer [73]). Despite these promising outcomes, most studies remain confined to buffer-based testing, with limited validation in complex biological matrices or patient-derived samples. Persistent challenges such as batch-to-batch reproducibility, signal interference, and operational stability in biofluids continue to hinder clinical translation.

7. Challenges, Emerging Trends, and Future Directions

Despite notable progress in the development of OFET biosensors, their translation from laboratory prototypes to clinically validated platforms remain hindered by several critical challenges. The foremost limitation lies in device stability, as organic semiconductors are intrinsically vulnerable to degradation under oxygen, moisture, and biofluid exposure, leading to signal drift and reduced operational lifespans [74]. While material innovations have been substantial, achieving long-term stability and biocompatibility remains an unresolved obstacle. Strategies to mitigate these effects include side-chain engineering for hydrophobic protection [75], encapsulation layers to suppress oxidation [76], and the application of self-assembled monolayers to passivate trap states [77]. Biocompatibility is equally vital, given that direct interfacing with biological samples demands materials that neither denature proteins nor induce cytotoxic effects. Recent progress in biofunctional polymers [78] and zwitterionic coatings [79] has improved reproducibility and reduced nonspecific binding, but seamless convergence of stability and biocompatibility remains essential for clinically reliable devices.

Beyond intrinsic material concerns, the lack of standardized fabrication and characterization protocols continues to impede reproducibility and cross-laboratory comparability. Substantial batch-to-batch variability, compounded by non-specific binding, protein fouling, and matrix effects in real biological environments, reduces both selectivity and sensitivity. Scaling up fabrication poses additional challenges [80]: although printing and roll-to-roll processing show promise for mass production, ensuring uniform performance and reliable biofunctionalization remains technically demanding. Complications further arise when integrating with complex physiological samples such as serum, saliva, urine, or sweat, where variations in ionic strength, pH, and protein content frequently interfere with device response. Finally, the pathway to clinical translation is constrained by limited regulatory validation, with only a small number of OFET biosensors advancing to preclinical or clinical evaluation.

To overcome these limitations, several emerging trends are redefining the OFET biosensing landscape. Flexible and wearable device platforms, built on stretchable substrates and biocompatible polymers, are being designed for continuous, non-invasive monitoring via epidermal patches and smart textiles. Multiplexed sensing through OFET arrays integrated with microfluidics enables simultaneous detection of multiple biomarkers from microliter-scale samples, advancing the vision of lab-on-chip diagnostics. Artificial intelligence and machine learning [81] offer transformative possibilities in data analysis, supporting real-time noise filtering, advanced signal interpretation, and predictive diagnostics. Complementary advances in energy harvesting and wireless communication are paving the way for self-powered OFET biosensors seamlessly integrated into IoT-based healthcare and telemedicine infrastructures.