Abstract

An indirect, novel, fast, and facile assay was developed for the colorimetric determination of fluoride anions using 96-well plates. The proposed method relies on the colorimetric degradation caused by fluoride ions after their reaction with the iron–thiocyanate complex in an acidic medium. The procedure required the addition of minimal amounts of ferric iron and thiocyanate anion solutions to form the corresponding complex with an intense blood-red color, after which, upon addition of fluoride ions, this complex would dissociate, and its color would gradually fade depending on the analyte concentration. The colorimetric differences were measured using a simple imaging device such as a flatbed scanner. Various parameters affecting the analytical performance of the proposed method were optimized, including solution concentrations, pH values, and reaction time for Fe(III)-SCN complex formation and its disintegration process. The proposed assay was successfully applied to the determination of F− in oral hygiene product samples. The method exhibited acceptable detection limits (3.2 mg L−1) with sufficient precision, good intra-day and inter-day reproducibility (ranging from 1.5 to 5.2%), and high selectivity against other anions and components of the samples under study.

1. Introduction

Fluorine, among the elements of the periodic table, is ranked 13th in terms of its quantity and exists only in anionic form as fluorite (CaF2), the most abundant fluoride mineral [1]. Fluoride anions (F−) have an interesting history, as fluorine and its derivatives are used in various fields, from industry to healthcare [2]. The discovery and study of fluoride anions are related to advances in chemistry and human needs for health and materials management [2]. Fluoride anions (F−) are the negatively charged ions that result when fluorine gains an electron. From the 19th century onwards, chemists began to understand the reactions of fluorine with other elements and its important properties. During the 20th century, the use of fluoride anions became even more important. In the 1940s, fluoride anions were first used in dentistry to prevent tooth decay, as F− strengthens tooth enamel [3]. The addition of fluoride to drinking water began in many countries to improve public health [4]. In industry, F− found applications in the production of aluminum and other fluorinated compounds, while their use in pharmaceuticals and cleaning compounds became increasingly common.

Regarding dental products, fluoride content ranges between 1.0 and 1.5 g kg−1. Fluoride anions can also be found in vegetables and fruits (0.1–0.4 mg kg−1), rice, and barley (~2.0 mg kg−1), and are accumulated in the bones of meat and fish. U.S.A. dietary recommendations for adults are from 3.0 to 4.0 mg per day, while in Europe they are limited between 2.9 and 3.4 mg per day. On the other hand, excess fluoride can contribute to health problems. The World Health Organization (WHO) set the recommended upper limit for fluoride in drinking water at 1.5 mg kg−1 [5]. Long-term exposure to higher fluoride levels may cause dental fluorosis, a dental disease that can cause defects in enamel formation, browning, and severe tooth deterioration [6].

Many techniques have been applied for the analytical determination of F−, including electrochemistry [7,8], titrimetry [9], ion chromatography [10,11], gas chromatography (GC) [12], fluorimetry [13,14], flow injection analysis (FIA) [15], and spectrometry [16,17,18]. Although these methods have excellent detection limits and accuracy, the necessity of laboratory equipment and significant amounts of reagents is a drawback for their use in routine analysis.

The iron–thiocyanate complex (Fe(SCN)x) is an example in which Fe(III) is linked to thiocyanate groups (SCN−). The thiocyanate ions act as ligands, attaching to the iron center through the nitrogen or carbon atom, depending on the position of the thiocyanate ion [19]. This complex is known for its intense color properties, with the most common color being red or orange, resulting from the interaction of iron with thiocyanate ions. These complexes are of interest in various fields, such as analytical chemistry, where they are used for the detection and quantification of iron [20], and for the indirect study of thiocyanate concentration [21].

The proposed analytical assay aimed to develop and validate an indirect, simple method with no sophisticated instrumentation for the colorimetric detection of fluoride anions in oral hygiene products, including toothpastes and mouthwashes, with the use of 96-well microplates. Adapting a microplate-based format allows for the simultaneous processing of a large number of samples, in contrast to separation and batch photometric methods [22,23,24]. The practicality and portability of the proposed method are additional advantages. A flatbed scanner provided colorimetric detection, maintaining a greener perspective compared to chromatographic instruments that use advanced mass spectrometric detection [25]. Microplates (also known as microtiter plates or microwell plates) offer many advantages in lab settings for biological, chemical, or pharmaceutical applications, including high throughput, low cost, reagent efficiency, compatibility with automated pipetting systems, and easy data collection using smartphones or flatbed scanners as detectors [26,27,28]. Fe(III) reacts rapidly with SCN− to form the deep blood-red =colored complex with a Kf ranging from 1.0 × 102 to 1.5 × 102. Then, an appropriate amount of fluoride ions was added to replace SCN− due to their higher affinity for Fe(III), with Kf ranging from 2 × 106 to 4 × 1012, leading to the formation of the colorless complex [FeF6]3− and the discoloration of the blood-red solution [29]. The proposed method was implemented for the determination of F− in oral healthcare products, and the results obtained were satisfactory in terms of sensitivity, recoveries, and reproducibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Solutions

All reagents used for the experiments were of analytical grade, and deionized water was used to dissolve and prepare their standard solutions. The standard concentrated solutions (stock solutions) of the corresponding reagents were prepared by weighing an appropriate amount of the reagent on a precision analytical balance, followed by the preparation of working solutions through subsequent dilutions. Ferric nitrate hexahydrate Fe(NO3)3 · 9H2O was supplied by Chem Lab NV (Zedelgem, Belgium), and a stock solution of 60 mM was prepared in 10 mM HNO3. A stock solution of 1.0 mol L−1 HNO3 was prepared from a 15.7 mol L−1 concentrated standard solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Ammonium thiocyanate (NH4SCN) was purchased from Panreac (Madrid, Spain), and a working solution of 100 mM was prepared weekly. Sodium fluoride (NaF), sodium chloride (NaCl), and sodium sulfate (Νa2SO4) were provided by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Sodium nitrate (NaNO3), sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO3), and magnesium nitrate hexahydrate (Mg(NO3)2 · 6H2O) were bought from Panreac (Madrid, Spain), Finally, potassium nitrate (KNO3), and calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Ca(NO3)2 · 4H2O) were provided by Chem Lab NV (Zedelgem, Belgium).

2.2. Apparatus

The experiments were performed in white, sterile 96-well plates with transparent bottoms (BRAND GMBH, Wertheim, Germany). Images of the microplates were captured at specific time intervals and from the same distance and angle using a flatbed scanner (IRIScan—Desk 6 Pro -Canon Europe, Amstelveen, The Netherlands) connected to a laptop. pH measurements were carried out using a pH meter (CONSORT, Turnhout, Belgium).

2.3. Experimental Steps

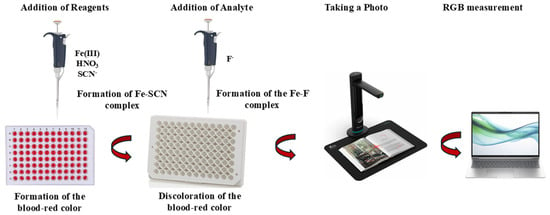

The experimental steps of the analytical methodology require minimal technical expertise and non-specialized instrumentation and are depicted in the following scheme (Figure 1). In brief, small volumes of deionized water, HNO3 solution (60 µL, 1.0 mmol L−1), Fe(III) solution (10 µL, 0.6 mmol L−1), and SCN− solution (60 µL, 20 mmol L−1) were added to the plate cells successively to form the stable, brightly colored [Fe(SCN)]2+ complex, and fluoride ions were added to diminish the blood-red colored complex. For the blank samples, deionized water was used instead of F−. After the reaction was completed in under one minute, the cells in the 96-well plate were photographed using a flatbed scanner and saved as JPEG files on a laptop computer, as depicted in Figure 1. The increase or fading of the color was then measured using the ImageJ (Version 1.53.k) program, both in the overall color area and in the red area, using the RGB function with a circular selection pattern, and the results were placed into an Excel sheet.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the methodology.

2.4. Oral Hygiene Samples

An accurately weighed amount of the toothpaste sample (10 g) was dispersed in 50 mL of water and stirred at room temperature with a magnetic stirrer for 10 min. The resulting solution was centrifuged at 2500 rpm at room temperature for 30 min. The insoluble part was washed several times with water, and the resulting solution was diluted to 100 mL and stored at 4 °C until measurement. For the children’s toothpaste sample, 20 g were weighed. Finally, the mouthwash samples were used as provided.

3. Results and Discussion

For the measurement of the mean color intensity of each sample, we performed analysis in triplicate and measured the color intensity of the sample minus the color intensity of the blank in all optimization experiments. For this, the fluoride concentration was replaced with deionized water.

3.1. Effect of Nitric Acid Concentration

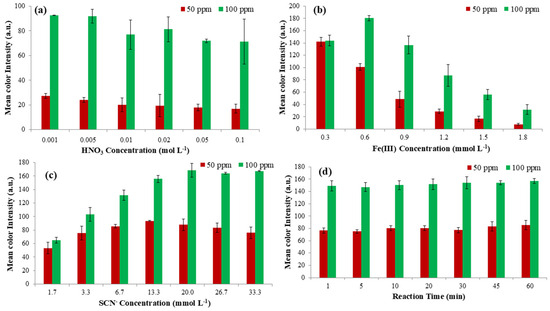

The regulation of pH has a significant impact on the formation of the starting complex between Fe(III) and SCN−, as well as the sensing complex between Fe(III) and F− ions. The dual goal of studying this parameter was to find the appropriate pH value so that (a) the complex between ferric iron and thiocyanate ions is created with an intense blood-red color and will be stable for a long time and (b) the breakdown of this complex with the addition of fluoride ions is rapid and proportional to their concentration. It is well established that the formation of the Fe-SCN complex is favored at acidic pH values, and nitric acid is the optimum solution for this assay [30]. Therefore, the influence of pH was studied at two different F-concentrations (50 and 100 mg L−1) by adding a certain volume of HNO3 solution (60 μL) at different concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 0.1 mol L−1. According to the data shown in Figure 2a, the optimal concentrations of HNO3 solutions were 0.001 and 0.005 mol L−1 for both concentrations of F− studied. For higher HNO3 concentrations, significant fading of the Fe(III)-SCN complex color was observed, which agrees with previous studies [21,30]. Between the two lowest concentrations, the HNO3 concentration of 0.001 mol L−1 was chosen as optimum for the rest of the experiments for reagent consumption reasons.

Figure 2.

Optimization of (a) Nitric acid concentration, (b) Trivalent iron concentration, (c) SCN− concentration, and (d) Reaction time that affect the performance of the proposed method.

3.2. Effect of Fe(III) Concentration

The next parameter studied was the concentration of Fe(III). This parameter plays an important role in the proposed methodology because it is important to achieve the most intense color of the solution possible, so that the color can be significantly quenched after the addition of fluoride ions. We aimed for the color to be as intense as possible so that we could lower the detection limits of the analyte as much as possible. So, the influence of Fe(III) concentration was studied at two different F− concentrations (50 and 100 mg L−1) by adding a certain volume of Fe(III) solutions (60 μL) at different concentrations ranging between 0.3 and 1.8 mmol L−1. From Figure 2b, it is clear that the optimum Fe(III) concentration is 0.6 mmol L−1 for both the signal of the highest fluoride concentration (100 mg L−1) and the proportionality of the two studied concentrations (the colorimetric signal is proportional). Thus, the Fe(III) concentration of 0.6 mmol L−1 was used for the following experiments.

3.3. Effect of SCN− Concentration

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, studying the effect of the concentration of thiocyanate ions is very important, as the intensity of the color of the formed complex depends on it. For this reason, the effect of this concentration was measured by adding a fixed volume of SCN− solutions (60 μL) ranging between 1.7 and 33.3 mM at two different F− concentrations (50 and 100 mg L−1). From Figure 2c, it is obvious that the optimum SCN− concentration is 20.0 mmol L−1 for both the signal of the highest fluoride concentration (100 mg L−1) and the proportionality of the two studied concentrations. Additionally, at low SCN− concentrations, the color was quite faint because of the lack of these ions and the incomplete formation of the complex, while at higher concentrations a plateau was reached. Thus, the SCN− concentration of 20.0 mmol L−1 was used for the upcoming experiments.

3.4. Effect of Reaction Time

The complexation reaction between fluoride ions and [Fe(SCN)]2+ is fast and occurs within seconds from the moment of addition of the analyte [21]. The effect of reaction time was therefore studied in the range of 1 to 60 min, with time intervals of 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min for the same fluoride concentrations as above. The 1 min reaction time appeared to be optimum for capturing the photograph, while at higher reaction times, no decrease was observed in the colorimetric signal. Thus, no major differences in the signals were observed (Figure 2d), which is why 1 min was chosen to decrease the length of the experimental process.

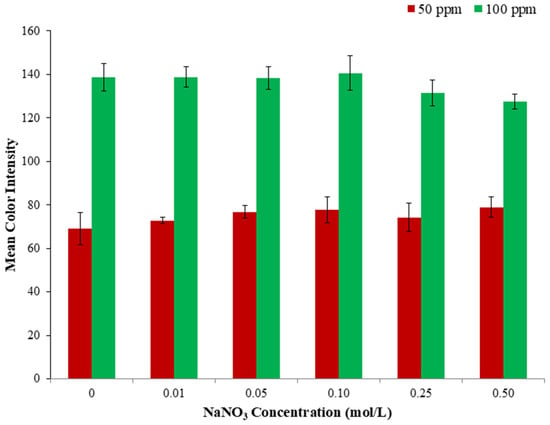

3.5. Effect of Ionic Strength

Ionic strength occasionally affects the formation and stability of complexes and the robustness of analytical methods, regarding the spectrophotometric evaluation of the Fe(III)-SCN complex [31]. Therefore, the effect of ionic strength was considered an important parameter to study. Different concentrations of NaNO3 solutions (from 0.01 to 0.50 mol L−1), obtained by dilution from the initial solution (2.0 mol L−1) (stock), were added into the wells of the plate. Specifically, no significant change is observed in Figure 3, for the first three NaNO3 concentrations (color alteration ranging from −0.2 to 1.4% relative error). In comparison, at the two higher salt concentrations, a small decrease was observed (−5.1 and −8.0% relative error, respectively). Thus, no salt addition was selected for the upcoming experiments.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the effect of ionic strength in the proposed method.

3.6. Method Validation

Method validation is a critical process in analytical chemistry to ensure that a proposed method is suitable for its intended purpose. It involves systematically evaluating various performance characteristics of the method, such as accuracy, precision, selectivity, linear range, detection limit, and quantitation limit, according to specific criteria.

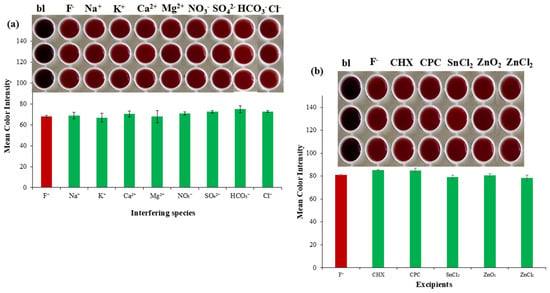

3.6.1. Selectivity

The selectivity of the method was validated by the determination of ions present in water and mouthwashes, which possibly hinder the formation of the complex we were studying. The cations and anions most frequently found, and at higher concentrations in water and mouthwashes are Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, NO3−, HCO3−, SO42−, and Cl−. Thus, with appropriate calculations and dilutions, the corresponding ion solutions were produced at concentrations commonly found in toothpaste and mouthwash samples (Table 1), while fluoride was at a concentration of 50 mg L−1. From Figure 4a, we observed that none of the ions studied interfered with the complexation of [Fe(SCN)]2+ with fluoride.

Table 1.

Concentration of the possible interfering ions used for the selectivity study.

Figure 4.

Selectivity study for the colorimetric determination of fluoride ions vs. (a) most common ions present in surface water samples, and (b) the excipients present in oral hygiene products.

The common active ingredients in toothpastes and mouthwashes are chlorhexidine (CHX), cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC), stannous chloride (SnCl2), zinc oxide (ZnO2), and zinc chloride (ZnCl2). These additives, present in the majority of toothpastes and mouthwashes, were studied in five-fold concentrations (Figure 4b), and no color differentiation was observed, which makes the method selective for the determination of fluoride in these samples. Phosphates can interfere by reacting to Fe(III), thus decreasing its concentration, or by causing precipitation and turbidity that affect color measurement. Despite the fact that phosphate concentration in toothpastes and mouthwashes are minimal, to avoid such interference, phosphate can be removed by precipitating it as a silver phosphate salt before the reaction with Fe(III)-SCN complex and the colorimetric measurement. This is achieved by adding a silver salt, such as silver nitrate (AgNO3), in an acidic solution, which causes the insoluble silver phosphate to precipitate, followed by filtration or centrifugation. On the contrary, oxalates are not typical ingredients in most oral hygiene products, so possible interference is negligible.

3.6.2. Figures of Merit

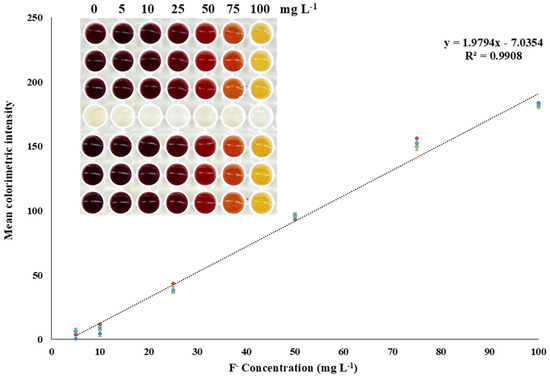

The next step for the determination of fluoride ions, after optimizing the parameters that affect this process, namely the complexation reaction of iron ions with thiocyanate ions, and their decomplexation and subsequent complexation with fluoride ions, was the study of successive calibration curves three times daily for five consecutive days to collect sufficient data to construct an overall calibration curve. To create this overall calibration curve, standard solutions of fluoride anions of different concentrations were measured. Specifically, concentrations of 5.0, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/L were measured, as this is the linear response of the proposed study, and each measurement was performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and repeatability of the method, as outlined in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Calibration curve of the proposed method. Integrated photo of the color change due to the existence of fluoride anions.

The intra-day precision was found to be 4.6 and 1.5% for measurements performed at concentrations of 25 and 75 mg/L, respectively. Correspondingly, the intra-day precision for the same fluoride concentrations was calculated and found to be 5.2 and 1.8%.

The limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were calculated based on the standard deviation of the constant term of the regression equation and the slope of the calibration curve, as LOD = 3.3 × SD/s and LOQ = 10 × SD/s, where SD is the standard deviation of the constant term and s is the slope of the regression equation. The LOD for the determination of the analyte was calculated to be 3.2 mg L−1, and the LOQ was 9.7 mg L−1. Most of the methods in Table 2 may have lower limits of detections but require complicated procedures, including synthesis of chromogenic substances, nanoparticles, and extraction in organic solvents. The proposed method may have higher LOD, but the procedure is fast, inexpensive, and only requires the addition of solutions produced from easily purchasable substances.

Table 2.

Comparison of the proposed method with similar colorimetric methods for the determination of fluoride anions.

3.7. Real Samples Application

The method was applied to real commercial toothpaste and mouthwash samples, specifically four toothpastes and two mouthwashes, endogenously. The fluoride concentrations of the samples were much higher than the upper bound of the calibration curve, so the appropriate dilution was performed (1/6 for the adult toothpastes, 1/8 for children’s toothpastes, and 1/10 for mouthwashes). The toothpaste samples included one children’s toothpaste targeting the age group of 2–6 years, with lower fluoride concentration (1000 mg L−1 instead of the 1450 mg L−1 F− present in adult toothpaste). Additionally, mouthwash samples had 220 and 225 mg L−1 F−, respectively. From the data in Table 3, it is clear that the recoveries of the endogenous measured levels of F− were satisfactory between 88 and 118.0%.

Table 3.

Accuracy of the proposed method for the analysis of F− in real samples.

4. Conclusions

An analytical method was developed and validated for the indirect determination of F− in oral hygiene products. Quantification of the analyte was performed by measuring the color reduction in the Fe-SCN complex by the analyte. The complexation reaction is favored at room temperature under acidic conditions and is completed in less than 1 min. The method developed was fast, simple, and accurate, with high selectivity against a variety of possible interfering substances. Finally, the method presented acceptable detection limits (3.2 mg L−1) with good applicability in toothpastes and mouthwashes with % recoveries ranging from 88 to 118%. There are some inconsistencies that need to be addressed in the future regarding possible interferences from phosphate, oxalate, and citrate anions and/or inaccurate recovery performances in certain samples. More specifically, sensitivity, accurate image acquisition, and data processing are parameters that need to be studied in detail. The above can be improved by using more sophisticated software which would obtain more accurate color intensity measurements and would not be affected by external factors, provided that the mentality of the method, minimizing the cost of equipment, is simultaneously maintained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z.T.; methodology, G.Z.T. and P.D.T.; validation, C.G. and M.T.; investigation, C.G.; data curation, C.G. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z.T. and P.D.T.; writing—review and editing, G.Z.T.; visualization, G.Z.T. and P.D.T.; supervision, G.Z.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| FIA | Flow Injection Analysis |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| JPEG | Joint Photographic Experts Group |

| RGB | Red–Green–Blue |

| CHX | Chlorhexidine |

| CPC | Cetylpyridinium Chloride |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Otal, E.H.; Kim, M.L.; Kimura, M. Fluoride detection and quantification, an overview from traditional to innovative material-based methods. In Fluoride; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshri, D.E. The modern inorganic fluorochemical industry. J. Fluor. Chem. 1986, 33, 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmer, J.P.; Hardy, N.C.; Chinoy, A.F.; Bartlett, J.D.; Hu, J.C.-C. How fluoride protects dental enamel from demineralization. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2020, 10, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffin, S.; Duffin, M.; Grootveld, M. Revisiting fluoride in the twenty-first century: Safety and efficacy considerations. Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 873157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Unde, M.P.; Patil, R.U.; Dastoor, P.P. The untold story of fluoridation: Revisiting the changing perspectives. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 22, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiruppathi, M.; Natarajan, T.; Zen, J.-M. Electrochemical detection of fluoride ions using 4-aminophenyl boronic acid dimer modified electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 944, 117685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, L.M.; Steyskal, E.-M. Electrochemical detection of fluoride ions in water with nanoporous gold modified by a boronic acid terminated self-assembled monolayer. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 6947–6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramović, B.F.; Gaál, F.F.; Cvetković, S.D. Titrimetric determination of fluoride in some pharmaceutical products used for fluoridation. Talanta 1992, 39, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talasek, R.T. Determination of fluoride in semiconductor process chemicals by ion chromatography with ion-selective electrodes. J. Chromatogr. A 1989, 465, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Y.P.; Liu, J.M. Determination of fluoride by an ion chromatography system using the preconcentration on nanometer-size zirconia. J. Anal. Chem. 2007, 62, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.M.; Shin, H.S. Sensitive determination of fluoride in biological samples by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry after derivatization with 2-(bromomethyl)naphthalene. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 852, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, H.; Kanno, C.; Yamada, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Suzuki, T.M. Fluorometric determination of fluoride ion by reagent tablets containing 3-hydroxy-2′-sulfoflavone and zirconium(IV) ethylenediamine tetraacetate. Talanta 2006, 68, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tu, S.; Le, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Ding, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, L. Development of a carbazole-based fluorescent probe for quantitative detection of fluoride ions in aqueous systems. Chem. Pap. 2023, 77, 1741–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themelis, D.G.; Tzanavaras, P.D. Simultaneous spectrophotometric determination of fluoride and monofluorophosphate ions in toothpastes using a reversed flow injection manifold. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 429, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, A.G.; Diro, A.; Asere, T.G.; Jado, D.; Melak, F. Spectroscopic determination of fluoride using eriochrome black T (EBT) as a spectrophotometric reagent from groundwater. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2021, 2021, 2045491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardımcı, B.; Üzer, A.; Apak, R. Spectrophotometric fluoride determination using St. John’s wort extract as a green chromogenic complexant for Al(III). ACS Omega 2022, 7, 45432–45442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhareva, O.; Mariychuk, R.; Sukharev, S.; Delegan-Kokaiko, S.; Kushtan, S. Application of microextraction techniques for indirect spectrophotometric determination of fluorides in river waters. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 11170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Berg, K.; Maeder, M.; Clifford, S. A new approach to the equilibrium study of iron(III) thiocyanates which accounts for the kinetic instability of the complexes particularly observable under high thiocyanate concentrations. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2016, 445, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Tapadia, K.; Soni, A.B. Determination of iron (III) in food, biological and environmental samples. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1415–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzis, D.; Zacharis, C.K.; Tsogas, G.Z.; Tzanavaras, P.D. High-throughput and green optical sensing of thiocyanate in human saliva based on microplates and an overhead book scanner as detector. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 248, 116317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.B.; Xu, X.R. Separation and determination of fluoride in plant samples. Talanta 1999, 48, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandulescu, R.; Florean, E.; Roman, L.; Mirel, S.; Oprean, R.; Suciu, P. Spectrophotometric determination of fluoride in dosage forms and dental preparations. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1996, 14, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayeoye, T.J.; Panghiyangani, R.; Singh, S.; Muangsin, N. Quercetin reduced and stabilized gold nanoparticle/Al3+: A rapid, sensitive optical detection nanoplatform for fluoride ion. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Sheng, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, K. Determination of trace fluoride in water samples by silylation and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 35, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkouliamtzi, A.G.; Tsaftari, V.C.; Tarara, M.; Tsogas, G.Z. A Low-Cost colorimetric assay for the analytical determination of copper ions with consumer electronic imaging devices in natural water samples. Molecules 2023, 28, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saranchina, N.V.; Slizhov, Y.G.; Vodova, Y.M.; Murzakasymova, N.S.; Ilyina, A.M.; Gavrilenko, N.A.; Gavrilenko, M.A. Smartphone-based colorimetric determination of fluoride anions using polymethacrylate optode. Talanta 2021, 226, 122103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvaki, G.N.A.; Tarara, M.; Tsogas, G.Z. Instrument-Free, novel colorimetric speciation of hexavalent chromium in natural waters using a flatbed scanner. Anal. Lett. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parham, H.; Rahbar, N. Solid phase extraction–spectrophotometric determination of fluoride in water samples using magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Talanta 2009, 80, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Prasad, S. Spectrophotometric determination of iron(III)–glycine formation constant in aqueous medium using competitive ligand binding. J. Chem. Educ. 2009, 86, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, M.W.; Rivington, D.E. Some measurements on the iron (111)–thiocyanate system in aqueous solution. Can. J. Chem. 1955, 33, 1572–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh, M.A. An extractive-spectrophotometric method for determination of fluoride ions in natural waters based on its bleaching effect on the iron (III)-thiocyanate complex. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 51, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushahary, B.C.; Biswakarma, N.; Thakuria, R.; Das, R.; Mahanta, S.P. In situ Ni(II) complexation induced deprotonation of Bis-Thiourea-Based tweezers in DMSO–water medium: An approach toward recognition of fluoride ions in water with organic probe molecules. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29300–29309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Ahamad, K.U.; Nath, P. Low-Cost, robust, and field portable smartphone platform photometric sensor for fluoride level detection in drinking water. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, F.; Farinha, A.S.F.; Santana, A.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Tomé, A.C.; Chernyshov, D.; Almeida Paz, F.A.; Cavaleiro, J.A.S.; Tomé, J.P.C. Colorimetric fluoride ion sensors based on dipyrrolic and bipyrrolic compounds: Synthesis and anion recognition. Dye. Pigment. 2025, 233, 112535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Shah, M.; Chaudhari, K.; Jana, A.; Sudhakar, C.; Srikrishnarka, P.; Islam, M.R.; Philip, L.; Pradeep, T. Smartphone-based fluoride-specific sensor for rapid and affordable colorimetric detection and precise quantification at sub-ppm levels for field applications. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 25253–25263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otal, E.H.; Kim, M.L.; Dietrich, S.; Takada, R.; Nakaya, S.; Kimura, M. Open-Source portable device for the determination of fluoride in drinking water. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murfin, L.C.; Chiang, K.; Williams, G.T.; Lyall, C.L.; Jenkins, A.T.A.; Wenk, J.; James, T.D.; Lewis, S.E. A colorimetric chemosensor based on a nozoe azulene that detects fluoride in aqueous/alcoholic media. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansaenpak, K.; Kamkaew, A.; Weeranantanapan, O.; Suttisintong, K.; Tumcharern, G. Coumarin probe for selective detection of fluoride ions in aqueous solution and its bioimaging in live cells. Sensors 2018, 18, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).