Abstract

Electrochemical detection is widely used in environmental, health, and food analysis due to its portability, low cost, and high sensitivity. However, when analytes with similar redox potentials coexist, overlapping voltammetric signals often occur, which compromises detection accuracy and sensitivity. In this study, a simple second-derivative image sharpening (IS) algorithm is applied to the electrochemical detection of chlorophenol (CP) isomers with similar redox behaviors. Specifically, a graphene-modified electrode was employed for the electrochemical detection of two chlorophenol isomers: ortho-CP (o-CP) and meta-chlorophenol (m-CP) in the range from 1.0 to 10.0 μmol/L. After image-sharpening, the peak potential difference between o- and m-CP increased from 0.08 V to 0.12 V. The limits of detection (LOD) for o-CP and m-CP decreased from 0.6 to 0.9 μmol/L to 0.12 and 0.31 μmol/L, respectively. The corresponding sensitivities also improved from 0.92 to 1.35 A/(mol L−1) to 4.11 and 3.71 A/(mol L−1), respectively. Moreover, the sharpened voltammograms showed enhanced peak resolution, facilitating visual discrimination of the two isomers. These results demonstrate that image sharpening can significantly improve peak shape, peak separation, sensitivity, and detection limit in electrochemical analysis. The obtained algorithm is computationally efficient (<30 lines of C++ (Version 6.0)/OpenCV, executable in <1 ms on an ARM-M0 microcontroller) and easily adaptable to various programming environments, offering a promising approach for data processing in portable electrochemical sensing systems.

1. Introduction

Electrochemical detection is particularly suitable for developing portable devices that enable in situ, on-site, and rapid analysis. Due to its advantages, such as portability, low cost, and high sensitivity, it has been widely applied in environmental, health, and food monitoring [1,2,3]. However, voltammetric detection—a commonly used electrochemical method based on redox reactions—often suffers from overlapping signals when analytes have similar peak potentials. This interference affects the accuracy and sensitivity of the detection [4,5]. Given the complex matrix interferences present in environmental, biological, and food samples, enhancing the signal recognition capability of electrochemical detection is essential [6,7]. To address this, various mathematical and computational techniques—including chemometrics, artificial neural networks, and computer vision—have been applied to process electrochemical data, particularly for signals with overlapping peaks [8,9,10,11,12]. However, these algorithms often require substantial computational resources, limiting their use in portable or field-deployable devices. Developing low-memory algorithms capable of high-precision electrochemical data processing remains a key challenge in portable detection system design.

Second-derivative Image sharpening is an image processing technique that makes an image appear clearer by enhancing the contrast of edges and details in the image [13]. With the development of computer technology, researchers have developed a variety of algorithms for image sharpening, ranging from the simplest Laplacian operator to high-pass filtering algorithms, wavelet algorithms, and even intelligent sharpening algorithms. So far, image sharpening algorithms have become a mature data processing technology [14]. The essence of the edge details in the voltammetry spectrum obtained by electrochemical detection is the electrochemical reaction of the target substance as the potential changes. One possible view holds that if the voltammetry is sharpened, details of the electrochemical reaction of the target substance may be obtained, thereby enhancing the clarity of the voltammetry. Meanwhile, the detection limit and sensitivity of the target substance calculated from the voltammetry spectrum may also increase accordingly.

Isomers of aromatic compounds usually have similar chemical properties and similar electrochemical redox behaviors. Therefore, the ability to detect isomers is often a reliable criterion for demonstrating the performance of electroanalytical methods. At present, electroanalytical methods have been reported in the detection of a series of aromatic isomers such as nitrophenols [15], aminophenols [16], nitrochlorobenzene [17], and naphthol [18]. Paper-based electrodes (including screen-printed electrodes) play an indispensable role in the detection of environmental pollutants, especially in aromatic isomers sensing [19,20]. Fan [21] reported the research about the simultaneous determination of hydroquinone and catechol isomers by a graphite paper electrode. So far, image sharpening algorithms have not been reported in the electrochemical detection of aromatic isomers.

Simultaneous detection of chlorophenol (CP) isomers is a typical electroanalytical research subject for aromatic isomers. At present, several reports have achieved simultaneous electrochemical detection of chlorophenol isomers [22,23]. Tian reviewed the electroanalytical investigation of CP isomers by tunable electrodes [22]. Our group also reported the simultaneous detection of 2-CP and 3-CP by cyclodexin-graphene electrode [23]. In this study, we selected o-chlorophenol and m-chlorophenol as model analytes due to their structural similarity and overlapping voltammetric behavior. A graphene oxide-modified glassy carbon electrode (GO/GCE) was used for detection, and a Laplacian-based image sharpening algorithm (second-derivative image sharpening) was applied to the voltammetric data. The effects of sharpening on peak resolution, detection limit, and sensitivity were systematically evaluated.

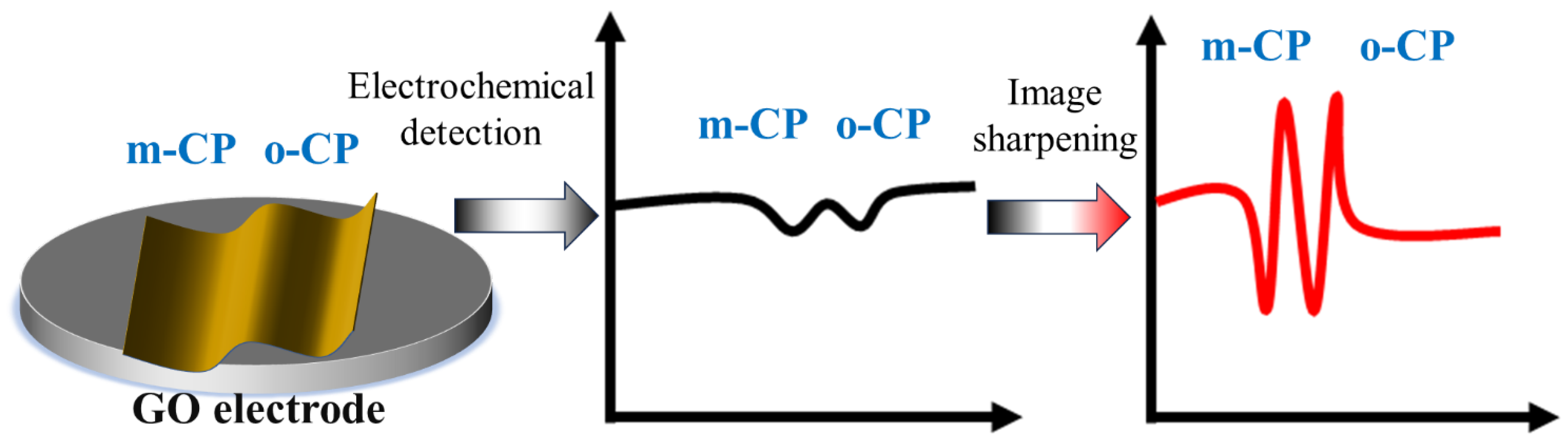

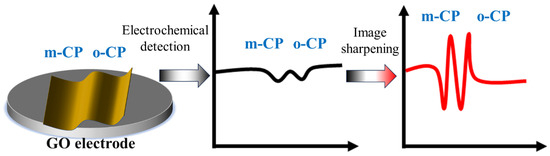

This paper aims to explore the application value of image sharpening in electrochemical detection, construct a representative standard electrochemical detection system, and conduct image sharpening on it. The paper selected two isomers with similar chemical properties, o-chlorophenol (o-CP) and m-chlorophenol (m-CP), as the detection objects, and used a single-layer graphene-modified electrode as the working electrode to study the electrochemical behavior and electrochemical detection of o-CP and m-CP, and obtained the voltammetry spectra before and after image sharpening. And calculate their corresponding detection limits and sensitivities, respectively (see Figure 1). Ultimately, the significance of image sharpening processing in electrochemical detection is explored from the aspects of detection spectra and detection performance.

Figure 1.

The Schematic diagram for this work (Image sharpening processing enhanced the electrochemical detection performance of chlorophenol isomers).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

Graphene oxide dispersions were purchased from XFnano Materials Technology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). and stored at 4 °C. Before use, the dispersions were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature. Reagents, including o-CP, m-CP, potassium chloride, disodium hydrogen phosphate, and sodium dihydrogen phosphate, were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Deionized water used in the work was prepared in-house. All reagents were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

2.2. Instrumentation

Electrochemical measurements were performed using a CHI-660C electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua Instrument Co., Shanghai, China). A conventional three-electrode system was employed, consisting of a GO/GCE as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, and a platinum wire as the auxiliary electrode. The diameter of the GCE is 3 mm, and the corresponding surface area is approximately 0.07 cm2. Surface morphology was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Philips, Amsterdam, Netherland) and atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker, Qingdao, China). The obtained ARM-M0 microcontroller was purchased from Wuhan Xinyuan Semiconductor Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) was provided by the Chongqing Changshou District Ecological Environment Monitoring Station and purchased from Agilent Technologies (Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd.

2.3. Electrode Preparation and Electrochemical Measurements

The preparation method for the graphene oxide (GO) modified electrode referred to the author’s previous work (carbon nanotube modified electrode), with minor modifications [24]. A glassy carbon electrode (GCE) was polished with alumina slurry and ultrasonically cleaned in deionized water. After drying, 5 μL of 0.5 wt% graphene oxide dispersion was drop-cast onto the electrode surface and dried under an infrared lamp to form the GO/GCE.

Linear scanning voltammetry (LSV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) in this work were conducted in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered solution (pH 5.5) containing varying concentrations of o-CP and m-CP. The potential range was 0.3–1.2 V, and scan rates of 20, 40, and 50 mV/s were tested. In quantitative analysis, the electrochemical determination of each concentration of the target substance needs to be repeated seven times, and the corresponding average value and relative error should be calculated.

2.4. Second-Derivative Image Sharpening Code and Procedure

The voltammetric data were exported and processed using a Laplacian sharpening algorithm implemented in C++ with OpenCV. The algorithm enhances the second derivative of the signal, emphasizing peak edges and improving visual resolution (second-derivative signal sharpening). The corresponding data processing code was tested on the ARM-M0 microcontroller. Thus, the algorithm is formally equivalent to a second-derivative electrochemical enhancement that has been used since the 1970s by Savitzky & Golay [25], but it is executed here in a single, low-memory pass on the microcontroller.

The code for the image-sharpening Algorithm 1 is listed below.

| Algorithm 1 The second-derivative image-sharpening algorithm |

| Image Sharpening Code (C++ with OpenCV) #include <opencv2/opencv.hpp> using namespace cv; int main() { Mat src = imread("image.jpg", IMREAD_GRAYSCALE); // Check if the image is loaded successfully if (src.empty()) { return −1; } // Create output image Mat dst; // Apply Laplacian operator int ddepth = CV_16S; // Use 16-bit signed depth to store derivative result Laplacian(src, dst, ddepth, 3, 1, 0, BORDER_DEFAULT); // Convert the result back to 8-bit Mat abs_dst; convertScaleAbs(dst, abs_dst); // Display the result imshow("Laplacian", abs_dst); waitKey(0); return 0; } |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Electrode Characterization

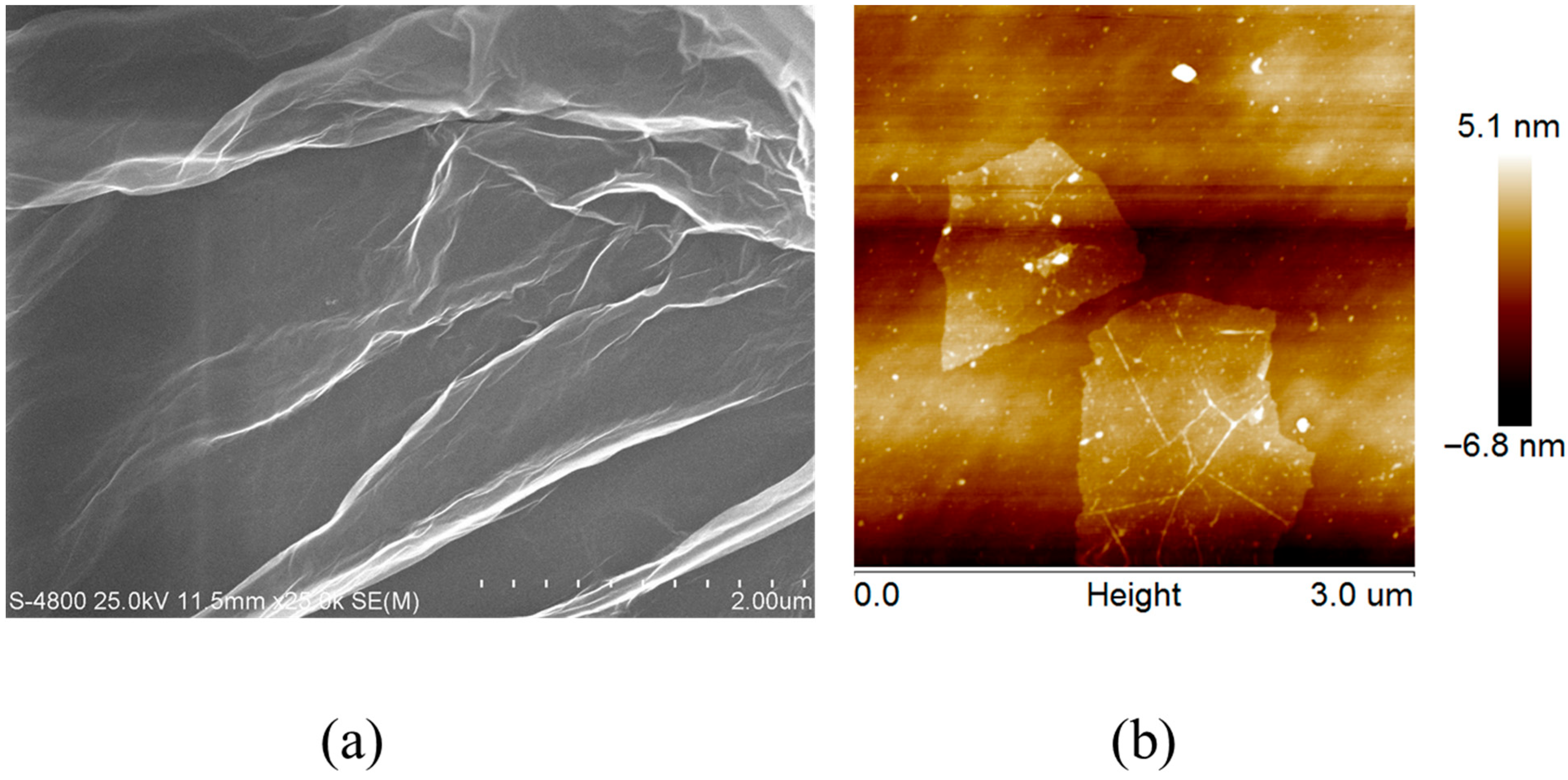

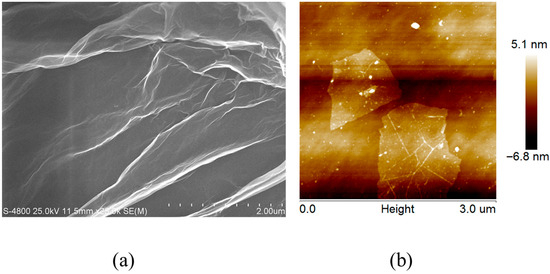

The morphology of the electrode materials was characterized by SEM and AFM, as shown in Figure 2a and Figure 2b, respectively. Figure 2a shows that graphene oxide exhibits a gossamer-like lamellar structure, indicating layered stacking on the electrode surface [26,27]. This phenomenon is consistent with previous reports in papers [28,29]. Figure 2b presents AFM images of single-layer graphene oxide, revealing micrometer-scale lateral dimensions and nanometer-scale thickness, consistent with the characteristics of monolayer graphene oxide [30,31,32]. These results confirm that graphene oxide is uniformly distributed on the electrode surface while retaining its microstructure, which is consistent with the literature reports [33,34,35]. Given its well-documented electrochemical performance, the GO-modified electrode was selected for subsequent electrochemical measurements and image sharpening analysis.

Figure 2.

The SEM (a) and AFM (b) images of graphene oxide.

3.2. Electrochemical Testing and Image Sharpening Processing

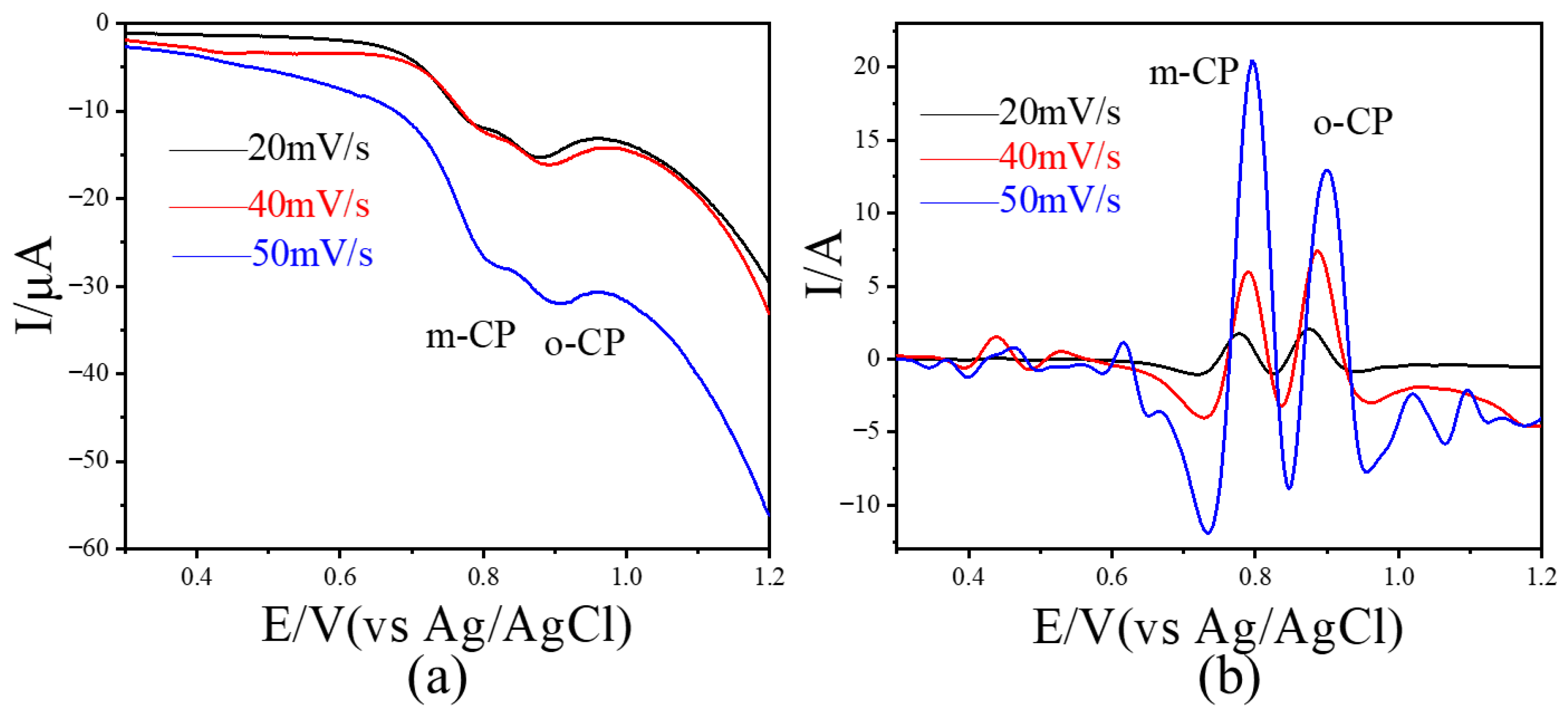

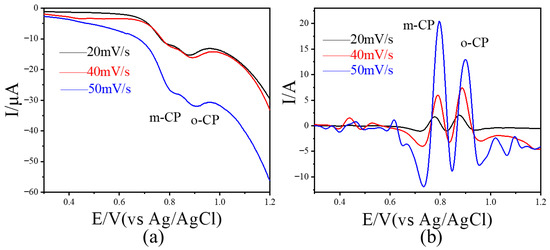

Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was performed on an electrolyte containing 10 μmol L−1 each of o-CP and m-CP over a potential range of 0.3–1.2 V. The resulting voltammogram is shown in Figure 3a. At scan rates of 20, 40, and 50 mV/s, two weak reduction peaks appeared between 0.8 and 0.9 V, corresponding to the electrochemical responses of o-CP and m-CP, respectively. The peaks were poorly resolved, with a small potential difference of approximately 0.08 V, making it difficult to distinguish between o-CP and m-CP using unprocessed voltammetric data. After image sharpening (Figure 3b), the peak shapes became sharper and more defined at all scan rates, allowing for clear visual discrimination between the two isomers. In addition, the distance between the two peaks (peak potential difference value) has also increased significantly, from 0.08 V to 0.12 V. The results show that image sharpening processing can significantly improve the peak shape in appearance and is helpful for intuitively judging the peak signals of similar substances. Considering that the details of the peak signals in electrochemical voltammetry are closely related to electrochemical analysis, we believe that image sharpening processing is helpful to improve the performance of electrochemical analysis methods.

Figure 3.

Linear scanning voltammetry results (a) of 10 μmol L−1 o-CP and m-CP coexisting at different scanning rates and corresponding linear scanning voltammetry results (b) after image sharpening processing.

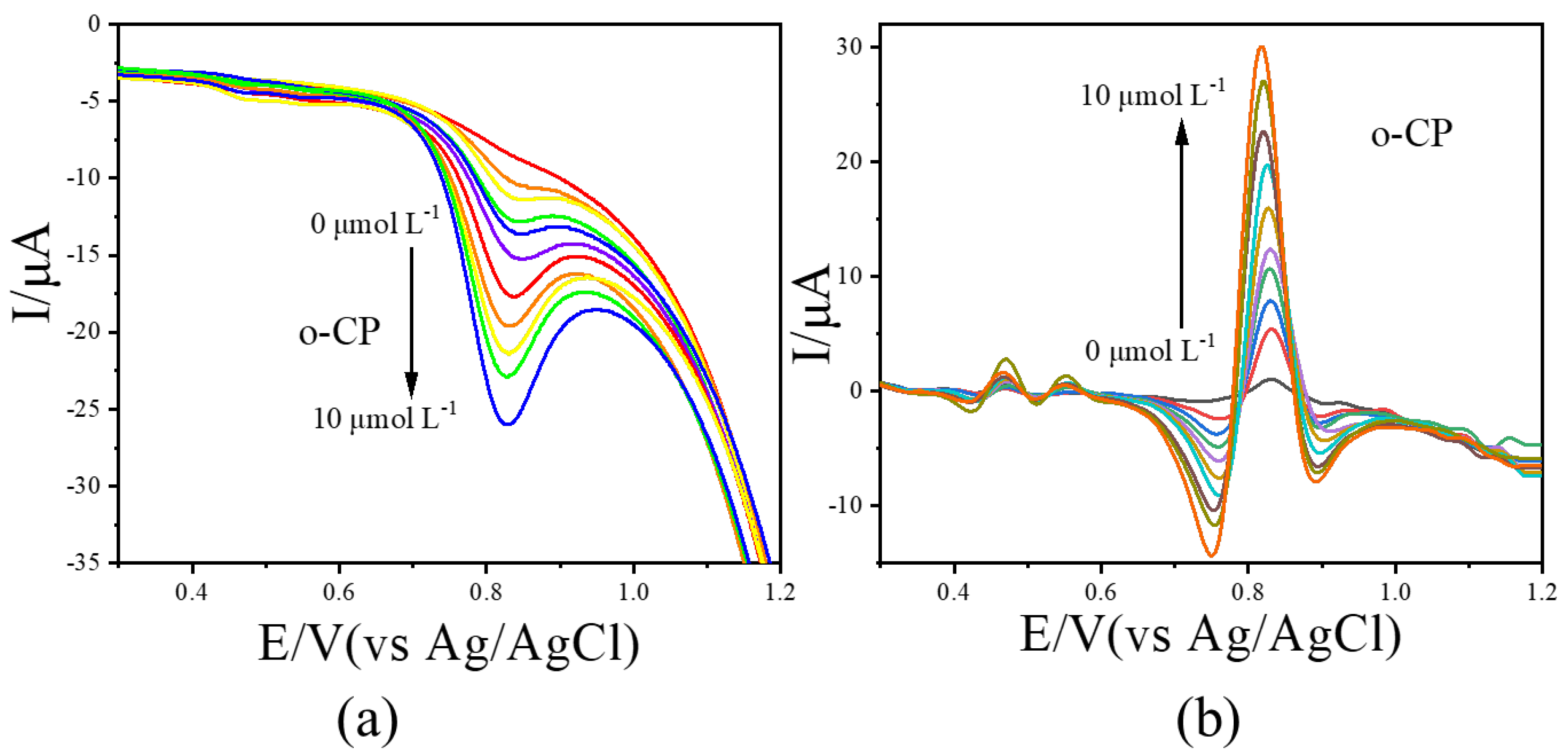

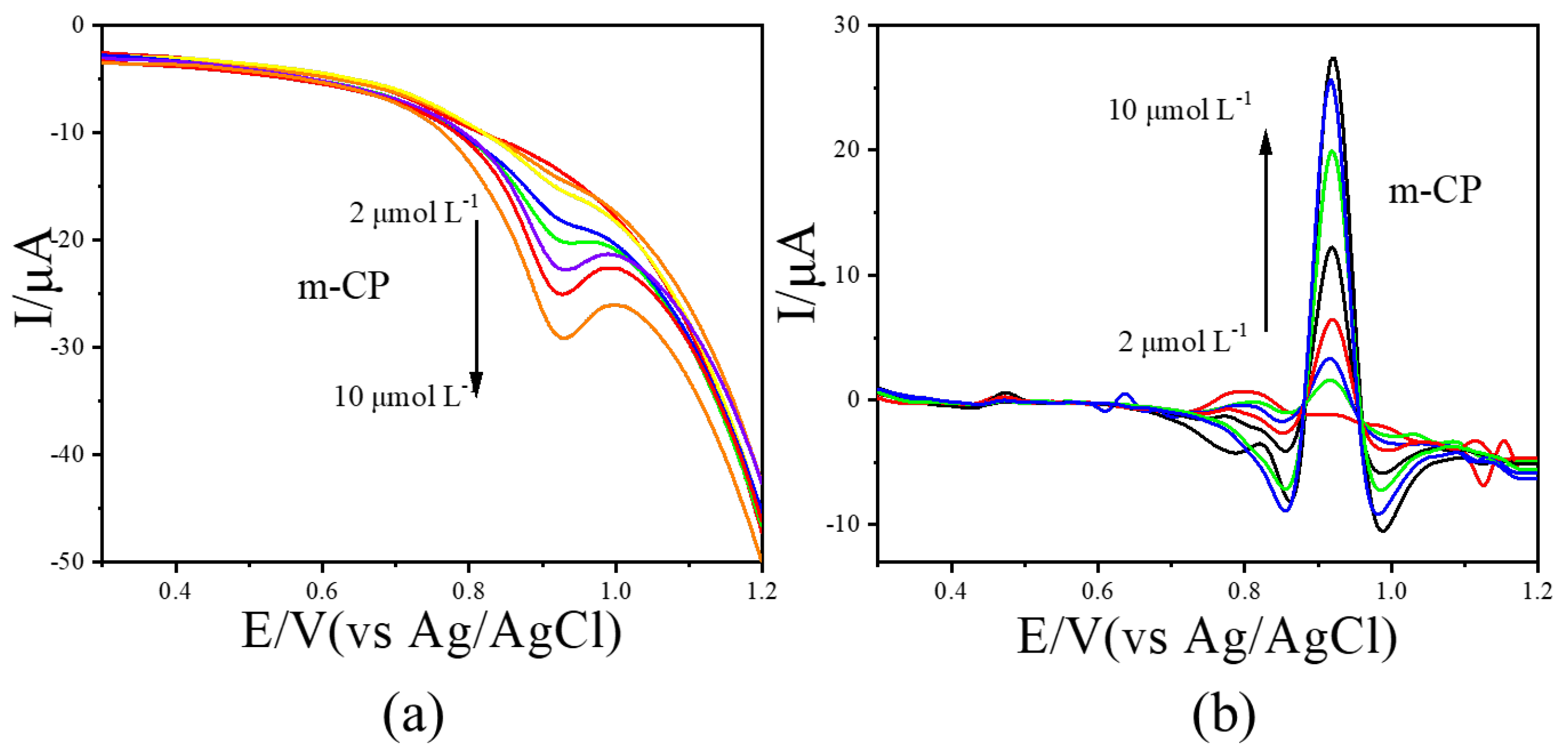

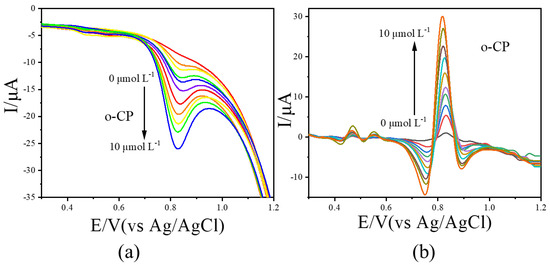

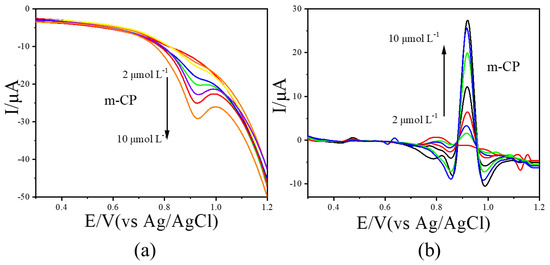

LSV measurements were further conducted for o-CP and m-CP at concentrations ranging from 0.0 to 10.0 μmol L−1. The resulting voltammograms were processed using the image sharpening algorithm, with results shown in Figure 4 (o-CP) and Figure 5 (m-CP). The LSV curves for o-CP with the concentration at 0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0 and 10.0 μmol L−1 were performed in Figure 4a. As shown in Figure 4a, o-CP exhibits a reduction peak at approximately 0.81 V across all concentrations. At low concentrations, the peak is broad and poorly defined. As the concentration increases, the peak becomes more pronounced and the peak current increases in the negative direction. After image sharpening processing on it (Figure 4b), the reduction peak of o-CP presents at about 0.84 V. Also, the reduction peak of o-CP can also show a sharp peak shape even at low concentrations, and the peak current significantly increases with the increase in o-CP concentration. Similar improvements were observed for m-CP (Figure 5). The solution containing m-CP with 0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, 10.0 μmol L−1 were used as electrolyte for LSV measurements. Image sharpening significantly enhanced peak definition, transforming broad peaks into sharp, well-resolved signals, with a corresponding increase in peak current. This phenomenon indicates that image sharpening can significantly improve the electrochemical spectra of o-CP and m-CP, making the electrochemical peaks sharper and more convenient for researchers to observe directly.

Figure 4.

The LSVs before (a) and after (b) second-derivative image sharpening for o-CP with different concentrations at 50 mV/s scan rate.

Figure 5.

The LSVs before (a) and after (b) image sharpening for m-CP with different concentrations at 50 mV/s scan rate.

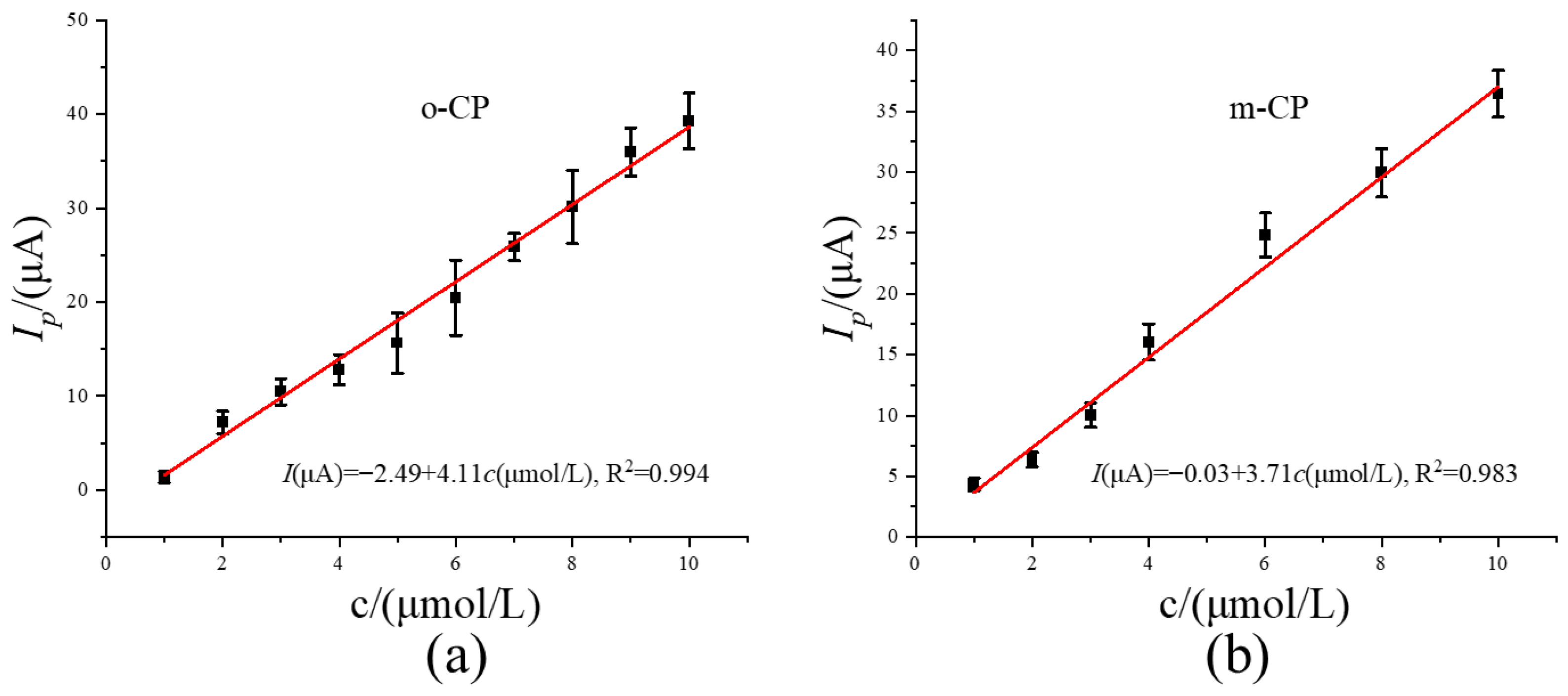

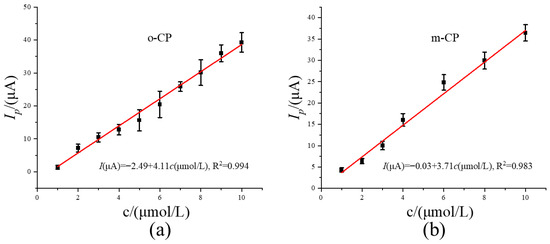

To further explore the significance of image sharpening in electrochemical detection from the perspective of detection performance, we plotted the linear relationship between concentration and peak current using the data obtained after image sharpening (Figure 4b and Figure 5b), and the corresponding results are shown in Figure 6a and Figure 6b, respectively. As shown in Figure 6, the concentrations of o-CP and m-CP both show a good linear relationship with the corresponding peak currents. The linear equations are Ipa (μA) = −2.49 + 4.11 c (μmol L−1), and Ipa (μA) = −0.03 + 3.71 c (μmol L−1), respectively. The corresponding values of correlation coefficient R is 0.997 and 0.996, respectively. Under the same conditions, repeated tests (n = 7) were conducted on o-CP samples of the same concentration, and the relative standard deviation (RSD) obtained was 2.52%. Meanwhile, the relative standard deviation of the repeated test results of o-CP (n = 7) was 3.12%. Based on this linear equation and the repeated experimental result data, we obtained the detection limit and sensitivity of the electrochemical method after image sharpening processing, and compared them with the values of the electrochemical detection method before image sharpening processing. The specific data are shown in Table 1. The results show that after image sharpening processing, the peak potential difference between o-chlorophenol and m-chlorophenol increased from 0.08 V to 0.12 V, and the calculated detection limits decreased from 0.60 μmol L−1 and 0.90 μmol L−1 to 0.12 μmol L−1 and 0.31 μmol L−1 respectively. The sensitivities increased from 0.92 A/mol L−1 and 1.35 A/mol L−1 respectively to 4.11 A/mol L−1 and 3.71 A/mol L−1. This indicates that after image sharpening processing, the detection limits and sensitivity of the two chlorophenols have been significantly improved, and second-derivative image sharpening processing has positive significance for the electrochemical detection of the two chlorophenols.

Figure 6.

The relationship curve between concentrations and peak currents for o-CP (a) and m-CP (b) second-derivative after image sharpening processing.

Table 1.

The analytical performance comparison of the obtained electrochemical method before and after second-derivative image sharpening processing.

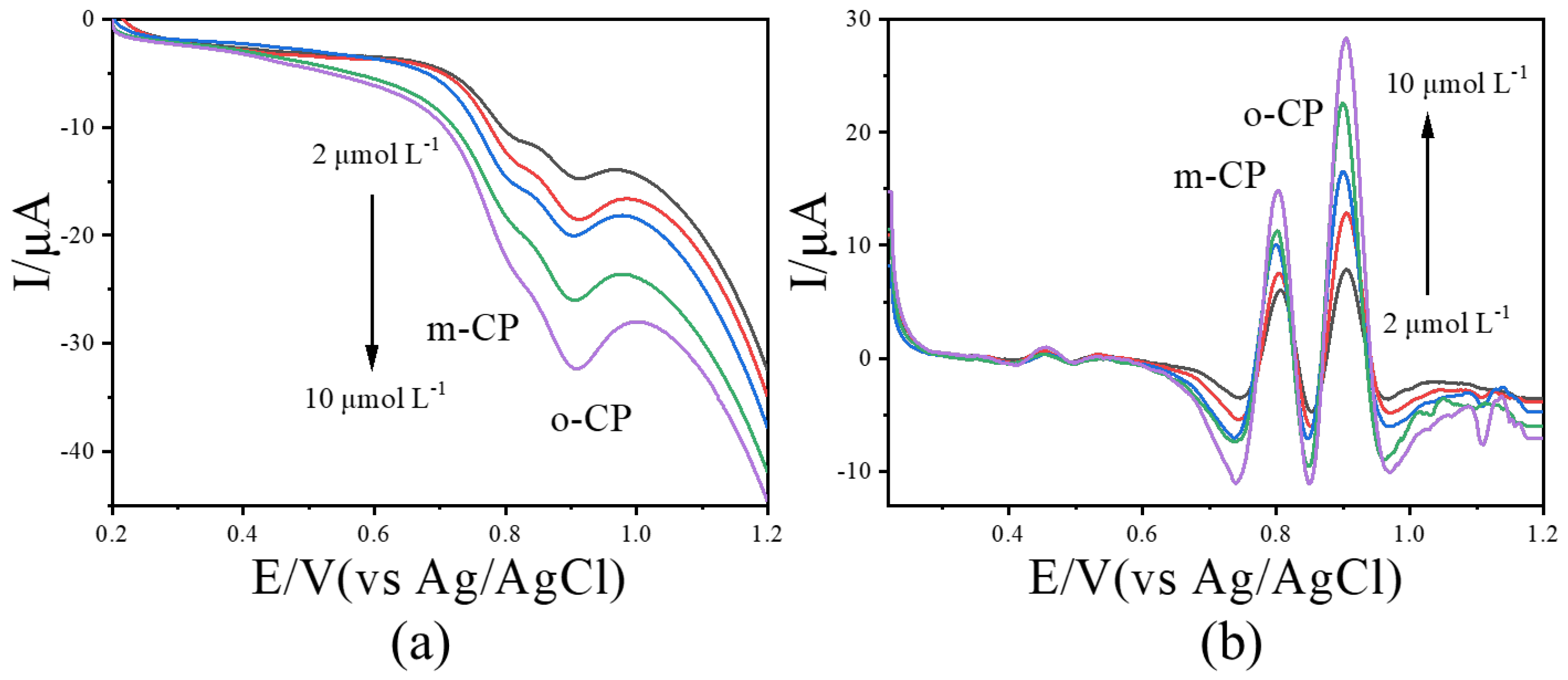

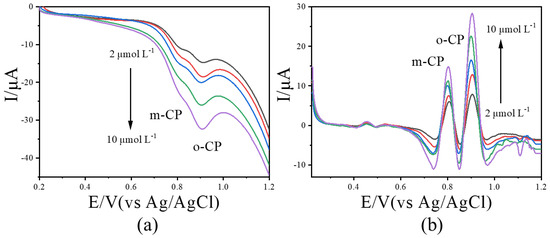

Since quantification and calibration in Figure 5 and Figure 6 were performed with individual analytes, we further examined the effect of image-sharpening (IS) processing on the calibration curves when o-CP and m-CP coexist. Mixed solutions containing both isomers at concentrations of 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, and 10.0 μmol L−1 were subjected to LSV. The corresponding results were performed in Figure 7. Prior to IS treatment, the current peaks for o-CP and m-CP were weak and poorly resolved (Figure 7a); after IS processing, both isomers exhibited well-defined peaks whose currents increased linearly with concentration (Figure 7b). This indicates that IS treatment still has a significant promoting effect on the calibration curve when two isomers coexist.

Figure 7.

The LSVs before (a) and after (b) second-derivative image sharpening for o-CP and m-CP coexist with different concentrations at 50 mV/s scan rate.

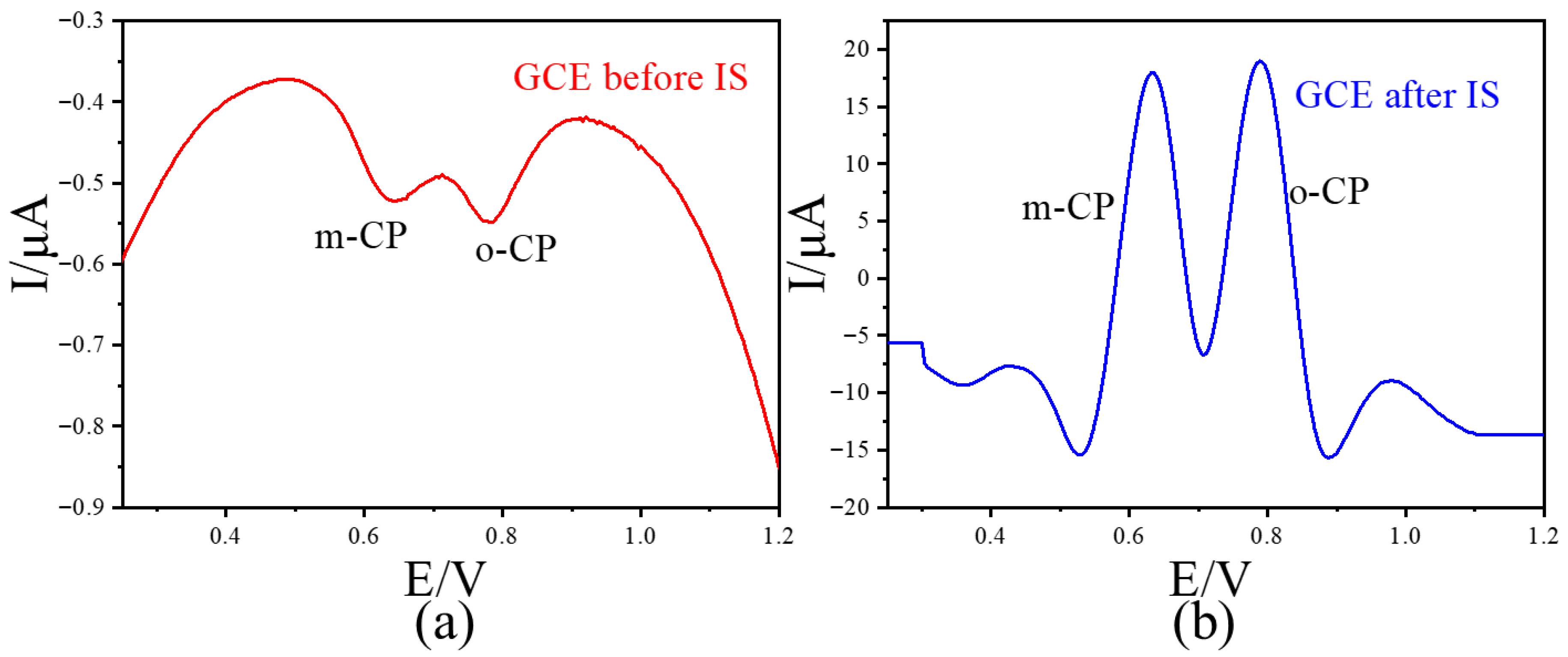

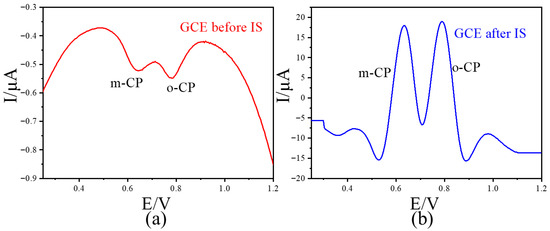

To avoid the influence of the adsorption effect between graphene and chlorophenol on the method adopted in this paper, we further investigated the electrochemical behavior of chlorophenol isomers on commercial glassy carbon electrodes (GCEs). The results showed that 2 μmol/L o-CP and m-CP exhibited weak electrochemical signals (peak current < 1μA) on GCE. After the IS data processing, the electrochemical signals of o-CP and m-CP were significantly increased (peak current >30 μA) (Figure 8). This increase is even more significant than that in graphene-modified GCE. The above results indicate that the method adopted in this paper has certain universality and can also be applied to commercial glassy carbon electrodes.

Figure 8.

The LSVs before (a) and after (b) second-derivative image sharpening for o-CP and m-CP coexist with different concentrations at GCE with 50 mV/s scan rate.

In summary, since image sharpening processing significantly improved the analytical performance of electrochemical detection of chlorophenol isomers, an electroanalytical detection method combining simple image sharpening processing was established.

3.3. Method Verification and Performance Comparison

To validate the feasibility and reliability of the proposed method, simulated sewage samples spiked with o-CP and m-CP were analyzed using both the IS-enhanced electrochemical method and HPLC. After pre−treatment, the simulated swage samples were prepared as the solutions to be tested (Table 2). A certain concentration of o-CP and m-CP will be added to the solution to be tested accordingly, and the final concentrations of chlorophenol in all samples were detected by the obtained IS processed electroanalysis method and by the HPLC as a standard control. The electrochemical results showed a strong correlation with HPLC data, with recovery rates ranging from 94.35% to 105.03%. Among them, the recovery rate for o-CP simulated sewage samples was 94.35–98.45%, with the RSD value being 2.03–4.56%. Meanwhile, the obtained method also achieved good results in the measurement of the m-CP simulated sewage sample, with the recovery rate in the range of 97.21% to 105.03%, and the RSD value in the range of 3.50% to 6.51%. Satisfactory recoveries were obtained in experiments with simulated sewage samples, demonstrating that the IS-processed electrochemical detection method had good analytical performance for the determination of o-CP and m-CP.

Table 2.

The detection of o-CP and m-CP in simulated sewage samples using the proposed method (n = 3).

Based on the good data in the previous analysis and detection, we transformed the second-derivative image sharpening algorithm into code (shown in Section 2.4, C++ with OpenCV) and used the ARM-M0 microcontroller as the single-chip microcomputer to conduct code tests on it. The results show that the code of this algorithm is extremely concise, with fewer than 30 lines. The algorithm consumes extremely little computing power and energy; the RAM consumption is less than 4 kB. Moreover, the single response time of this algorithm on the single-chip microcomputer is less than 1 ms. In summary, this algorithm has a series of advantages, such as concise code, small memory occupation, and fast response speed, and has significant application advantages in portable electrochemical sensors or portable electrochemical workstations.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a simple image sharpening algorithm can effectively enhance the resolution of overlapping voltammetric signals. By improving peak shape and separation, the method significantly increases sensitivity and lowers detection limits, offering a valuable tool for the electrochemical analysis of structurally similar compounds. The algorithm is cost-effective and computationally efficient, requiring minimal code and computing resources. Its simplicity and speed make it highly suitable for integration into portable electrochemical detection systems.

Author Contributions

S.D. completed most of the experimental work and the writing of this thesis. Y.W. finished the HPLC experiments and related data processing. Y.W. also provided chlorophenol standard samples and HPLC equipment for the research of this thesis. F.X. provided suggestions and revision opinions for the writing of this article. C.Z. provided the research ideas for this thesis and designed detailed research methods. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (NO. 2024NSCQ-MSX0774), Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (NO. KJQN202404503).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my most sincere gratitude to Changli Zhou for his earnest teachings and detailed guidance on this thesis. I miss him very much.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.N.; Niu, Q.; Gu, X.; Yang, N.; Zhao, G. Recent progress on carbon nanomaterials for the electrochemical detection and removal of environmental pollutants. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 11992–12014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, J.F.; Rojas, D.; Escarpa, A. Electrochemical sensing directions for next-generation healthcare: Trends, challenges, and frontiers. Anal. Chem. 2020, 93, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S.; Wu, X.; Shu, Z.; Xiao, A.; Chai, B.; Pi, F.; Wang, J.; Dai, H.; Liu, X. Curcumin-enhanced MOF electrochemical sensor for sensitive detection of methyl parathion in vegetables and fruits. Microchem. J. 2023, 184, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhao, J.; Bi, J.; Wu, G. Ion interference and elimination in electrochemical detection of heavy metals using anodic stripping voltammetry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 057507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.O.; Mafa, J.P.; Mabuba, N.; Arotiba, O.A. Dealing with interference challenge in the electrochemical detection of As (III)—A complexometric masking approach. Electrochem. Commun. 2016, 64, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, F.; Barceló, D. Challenges and strategies of matrix effects using chromatography-mass spectrometry: An overview from research versus regulatory viewpoints. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 134, 116068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariño, C.; Banks, C.E.; Bobrowski, A.; Crapnell, R.D.; Economou, A.; Królicka, A.; Pérez-Ràfols, C.; Soulis, D.; Wang, J. Electrochemical stripping analysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthongkham, P.; Wirojsaengthong, S.; Suea-Ngam, A. Machine learning and chemometrics for electrochemical sensors: Moving forward to the future of analytical chemistry. Analyst 2021, 146, 6351–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desagani, D.; Ben-Yoav, H. Chemometrics meets electrochemical sensors for intelligent in vivo bioanalysis. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 164, 117089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapoulouzi, M.; Ortone, V.; Cinti, S. Heavy metals detection at chemometrics-powered electrochemical (bio) sensors. Talanta 2022, 244, 123410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, K.L. A Study of Artificial Neural Networks for Electrochemical Data Analysis. ECS Trans. 2010, 25, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, K.; Thik, J.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ling, C. Computer vision enabled high-quality electrochemical experimentation. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 2183–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, K.N.; Potnis, A.; Dwivedy, P. A review on image enhancement techniques. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Comput. Sci. 2017, 2, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Mittal, A. Various image enhancement techniques-a critical review. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. 2014, 10, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Duan, S.; Xu, S.; Zhou, C. β-Cyclodextrin functionalized mesoporous silica for electrochemical selective sensor: Simultaneous determination of nitrophenol isomers. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 58, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhou, C. Simultaneous determination of aminophenol isomers based on functionalized SBA-15 mesoporous silica modified carbon paste electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 88, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Xu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhou, C. Electrochemical behavior of nitrochlorobenzene isomers based on ordered porous silica carbon paste electrode. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2011, 21, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Duan, S.; Liu, S.; Wei, M.; Xia, F.; Tian, D.; Zhou, C. Sensitive and simultaneous method for the determination of naphthol isomers by an amino-functionalized, SBA-15-modified carbon paste electrode. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 3063–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummari, S.; Panicker, L.R.; Rao Bommi, J.; Karingula, S.; Sunil Kumar, V.; Mahato, K.; Goud, K.Y. Trends in paper-based sensing devices for clinical and environmental monitoring. Biosensors 2023, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, W.; Cetinkaya, A.; Kaya, S.I.; Varanusupakul, P.; Ozkan, S.A. Electrochemical paper-based analytical devices for environmental analysis: Current trends and perspectives. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 40, e00220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Li, X.; Kan, X. Disposable graphite paper based sensor for sensitive simultaneous determination of hydroquinone and catechol. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 213, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Chen, S.; Yu, J.; Zhang, M.; Gao, N.; Yang, X.; Wang, C.; Duan, X.; Zang, L. Tunable construction of electrochemical sensors for chlorophenol detection. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 10171–10195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Tian, D.; Liu, S.; Zheng, X.; Duan, S.; Zhou, C. β-Cyclodextrin functionalized graphene material: A novel electrochemical sensor for simultaneous determination of 2-chlorophenol and 3-chlorophenol. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 195, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Yue, R.; Huang, Y. Polyethylenimine-carbon nanotubes composite as an electrochemical sensing platform for silver nanoparticles. Talanta 2016, 160, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porchet, J.P.; Günthard, H.H. Optimum sampling and smoothing conditions for digitally recorded spectra. J. Phys. E Sci. Instrum. 1970, 3, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Feng, S.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W. Effect of temperature on the mechanical properties, conductivity, and microstructure of multi-layer graphene/copper composites fabricated by extrusion. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 7773–7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Feng, F. Controllable synthesis of gossamer-like Nb2O5-RGO nanocomposite and its application to supercapacitor. J. Nanopart. Res. 2020, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.-S.; Chang, S.-M.; Lecaros, R.L.G.; Ji, Y.-L.; An, Q.-F.; Hu, C.-C.; Lee, K.-R.; Lai, J.-Y. Fabrication of hydrothermally reduced graphene oxide/chitosan composite membranes with a lamellar structure on methanol dehydration. Carbon 2017, 117, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, P.; Huang, C.; Xu, F.; Zou, Y.; Chu, H.; Yan, E.; Sun, L. Graphene-oxide-induced lamellar structures used to fabricate novel composite solid-solid phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 362, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigler, S.; Hof, F.; Enzelberger-Heim, M.; Grimm, S.; Müller, P.; Hirsch, A. Statistical Raman microscopy and atomic force microscopy on heterogeneous graphene obtained after reduction of graphene oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 7698–7704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-H.; Zhang, P.; Ren, H.-M.; Zhuo, Q.; Yang, Z.-M.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, Y. Surface adhesion properties of graphene and graphene oxide studied by colloid-probe atomic force microscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 258, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Alkhidir, T.; Mohamed, S.; Anwer, S.; Li, B.; Fu, J.; Liao, K.; Chan, V. Investigation of interfacial interaction of graphene oxide and Ti3C2Tx (MXene) via atomic force microscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 609, 155303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Feng, H.; Li, J. Graphene oxide: Preparation, functionalization, and electrochemical applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 6027–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi, A.; Chua, C.K.; Latiff, N.M.; Loo, A.H.; Wong, C.H.A.; Eng, A.Y.S.; Bonannia, A.; Pumera, M. Graphene and its electrochemistry—An update. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2458–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitollai, H.; Safaei, M.; Tajik, S. Application of Graphene and Graphene Oxide for modification of electrochemical sensors and biosensors: A review. Int. J. Nano Dimens. 2019, 10, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).