Abstract

Background: Percutaneous electrical stimulation and transcutaneous electrical stimulation (PTNS and TTNS) of the posterior tibial nerve are internationally recognized treatment methods that offer advantages in terms of treating patients with overactive bladder (OAB) who present with urinary incontinence (UI). This article aims to analyze the scientific evidence for the treatment of OAB with UI in adults using PTNS versus TTNS procedures in the posterior tibial nerve. Methods: A systematic review was conducted, between February and May 2021 in the Web of Science and Scopus databases, in accordance with the PRISMA recommendations. Results: The research identified 259 studies, 130 of which were selected and analyzed, with only 19 used according to the inclusion requirements established. The greatest effectiveness, in reducing UI and in other parameters of daily voiding and quality of life, was obtained by combining both techniques with other treatments, pharmacological treatments, or exercise. Conclusions: TTNS has advantages over PTNS as it is more comfortable for the patient even though there is equality of both therapies in the outcome variables. More research studies are necessary in order to obtain clear scientific evidence.

1. Introduction

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) defines overactive bladder syndrome (OAB), with code GC50.0, as a urological condition characterized by voiding urgency, polyuria, and nocturia that may or may not be accompanied by urinary incontinence (UI) [1]. OAB presents a worldwide prevalence [2] of 16% to 23%, rising to 15% in those over the age of 40 years [3] and to 30–40% in those over 75 years [4], although it can be found in people of all ages. Its prevalence in Europe [5] is around 12%.

J.C. Angulo, in an article [6] published in 2016, revealed a 19.46% prevalence of OAB in the Spanish population, with at least one episode of urge UI (UUI) a day in 48.74% of cases [6]. This prevalence is greater in females than in males. Studies conducted [7] in the populations of Europe, the United States, Asia, and Africa reveal a prevalence of UUI of 1.5% to 14.3% in men aged between 18 and 20 years, whereas in women, it ranges from 1.6% to 22.8%. The same is true for those aged over 30 years, where the prevalence in men is from 1.7% to 13.3%, as opposed to 7% to 30.3% in women [7].

Among subjects with OAB on the global scale, UUI has been observed to be the most unpleasant symptom of this condition [4]. Further, people with OAB usually adopt certain coping strategies that involve a decrease in their quality of life and socialization, such as limiting liquid intake, avoiding traveling, and attempting to have direct access to toilets [3].

UI is the involuntary leakage of urine and lack of ability to control urination, accompanied by spontaneous contractions of the detrusor muscle. There are various subtypes of UI: urgency UI (UII), the sudden desire or need to urinate; stress UI (SUI), caused by efforts, physical exercise, sneezing, or coughing; mixed UI (MUI), combined with urgency and efforts [1] (code MF50.2 in ICD-11). To be able to determine the best treatment option in each patient, a personalized assessment is necessary, including the evaluation of different aspects of health, motivation, and availability or access to specific treatments [2].

Profitability is a fundamental aspect when it comes to reviewing treatment options in this type of condition, which entail great social and financial costs. Previous studies [7] showed a value of EUR 7 billion in subjects with OAB over 18 years old in Canada and European countries, including Spain [7].

There are several alternatives for OAB and UI treatment: behavioral treatments, considered first-line treatments; pharmacological or second-line treatments such as anticholinergic or antimuscarinic and b-adrenergic drugs, and, by way of a third line of treatment, injections of OnabotulinumtoxinA and therapies with electrical stimulation, including, among others, percutaneous and transcutaneous electrical stimulation (PTNS and TTNS, respectively), which are the object of this study [8].

With regard to treatment by electrical stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve (PTN), this involves retrograde stimulation of the nerve fibers of the sacral plexus, which innervates the bladder and detrusor muscle [2,3,4,5,8]. Electrical stimulation can be applied through insertion of a needle in the PTN—that is, PTNS is carried out in the said nerve—or through surface electrodes, with TTNS [9], with beneficial and safe effects in the short term in women with OAB, and no relevant adverse effects [10], according to the review by Sousa-Fraguas et al., 2020.

These techniques may represent an advantage in treatment of subjects with OAB who present UI, enabling these difficulties to be solved, as they can be compared favorably to treatment using antimuscarinic drugs, due to them being less costly [11].

In this respect, the present study aimed to summarize the knowledge available and conduct a critical analysis of the evidence from randomized controlled clinical trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses on the effectiveness of PTNS and TTNS in the treatment of adults with OAB who present UI.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO/NHS)—number: 184809.

2.1. Selection Criteria

Three researchers independently reviewed the articles found. In order to formulate the objective and the question of the review, the PICOS strategy was used [13] (P—population or patients; I—intervention; C—comparison; O—outcomes; S—study design), in which P = (adults with OAB syndrome (OABS) and presence of UI); I = (PTNS and TTNS); C = (control group that received no intervention or received standard/usual care); O = (randomized clinical trials (RCTs), descriptive, observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses), and S = (randomized controlled clinical trials, descriptive observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses). This strategy enabled the establishment of critical reasoning on the issue [13] and the formulation of the following question: “What is the existing scientific evidence on the treatment of adults diagnosed as having OABS with UI through procedures of PTNS versus TTNS?”.

2.2. Data Sources

The bibliographic search was performed between the months of February and May 2021. The search terms used were percutaneous electric nerve stimulation; transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation; adult; urinary bladder, overactive; urinary incontinence; tibial nerve. Two multidisciplinary databases, Scopus and Web of Science (WOS), were used in the search. The search strategy followed is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy in WOS and Scopus databases.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

By way of exclusion criteria: all articles not published in English or Spanish; studies conducted in patients with neurological diseases or UI exclusively of neurogenic origin; carried out in children, animals, or patients with an associated underlying pathology; addressing fecal incontinence; in which treatment was not carried out with PTNS or TTNS of the PTN, or not aimed at treatment of OAB with UI; narrative or nonsystematic reviews; all documents not aligned with the research problem. The bibliographic research focused on all articles published from 2015 to 2020.

In order to obtain reliable, valid results, without them being influenced by bias, the Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale (PEDro) [14] was used to assess the methodological quality of the experimental studies, based on the Delphi list [15]. In the same way, the STROBE declaration [16] was applied for the evaluation of observational-type studies, and the PRISMA declaration [14] for reviews that followed its criteria in their execution. Articles that did not exceed the score of five in the PEDro scale [14] or with a score of less than 11 points in the STROBE declaration [16] were excluded, finally obtaining the articles chosen for the review.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

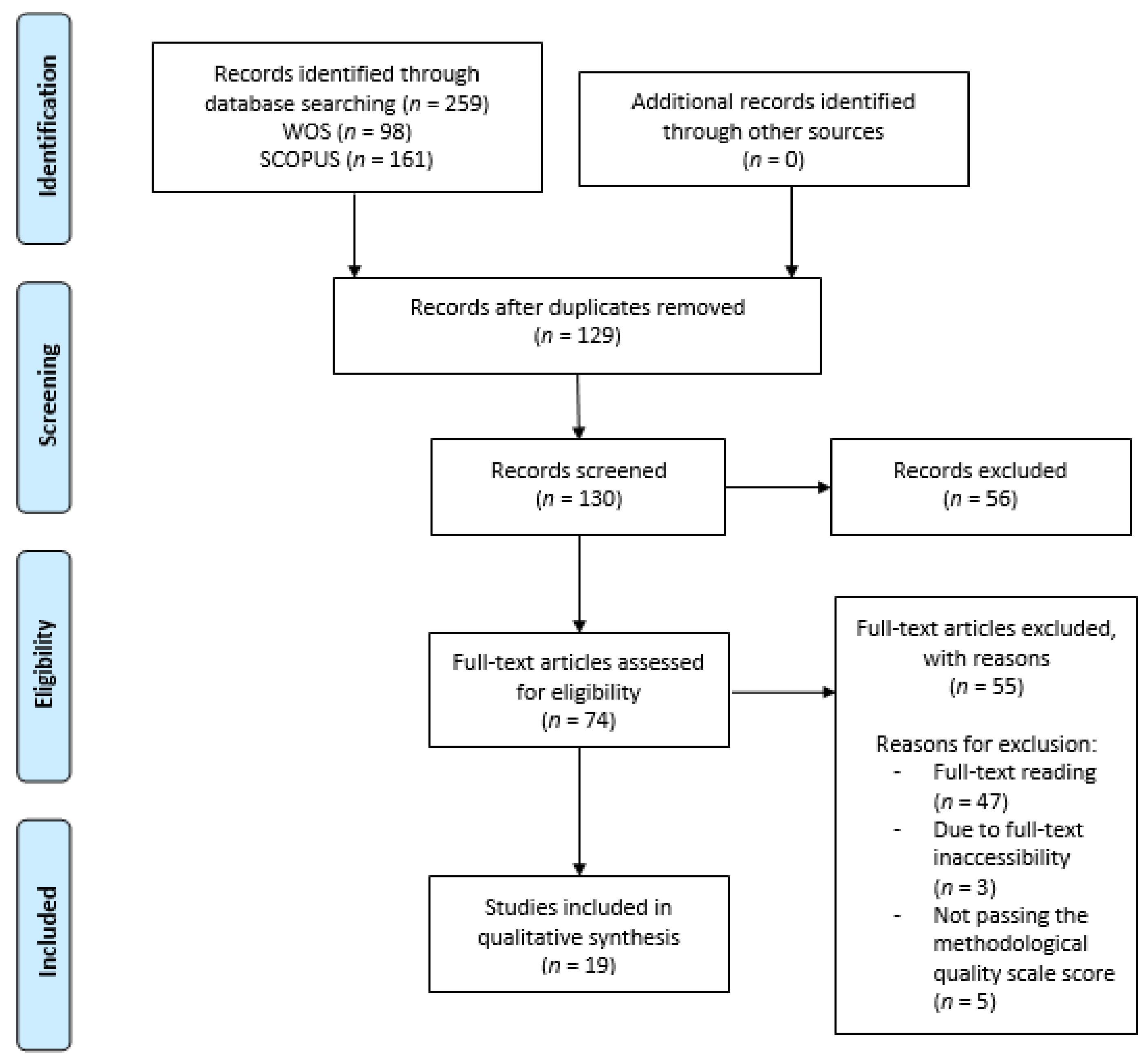

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart of this systematic review.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of this systematic review.

The initial search in the databases gathered a total of 259 articles, 98 from Web of Science (WOS) and 161 from Scopus.

The initial screening phase produced 130 articles after removing duplicates (n = 129).

Based on the titles and abstracts of the articles, a total of 56 articles were removed. Then, considering the remaining 74 eligible studies, many were excluded after full-text reading (n = 47), or because it was not possible to access the full text (n = 3), or for not passing the methodological quality scale (n = 5).

Finally, 19 studies [3,4,5,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] were included. Of these, nine were experimental [3,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], including eight RTCs [3,17,18,19,20,21,22,24] (Table 2); four were observational studies [5,25,26,27] (Table 3), and six were either systematic reviews [4,29,31] or a meta-analysis [28], while two encompassed both types of studies [30,32] (Table 4).

Table 2.

Characteristics of experimental studies included in the systematic review. Sevilla, ES. 2021.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the observational studies included in the systematic review. Sevilla, ES. 2021.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in the systematic review. Sevilla, ES. 2021.

3.2. Summary of the Evidence

As for the comparison between PTNS and TTNS therapy, studies were found [3,17] in which significant changes were observed in the variables of diurnal frequency of urination, nocturnal frequency of urination, 24-h voiding frequency, mean voided volume, and number of episodes of UI and UUI in 24 h [17].

When TTNS combined with trospium chloride [20] was compared to placebo, a decrease in frequency of urination was observed in both groups (p = 0.001 and p= 0.003, respectively); as to mean voided volume, significant improvements were observed in both groups, with greater significance in the combined therapy (p = 0.005), although there was a significant delay in the combined therapy group with regard to the first sensation of a full bladder [20].

In other studies [23,32], upon combining PTNS with drugs, 35/53 participants completed the satisfaction survey after treatment, 66% of whom preferred to continue with maintenance treatment, with a mean interval of 44.4 days (7–155 days) and frequency of sessions of 1.1 months; attendance was observed if there were symptoms of OAB, while patients with multiple sclerosis had the possibility of returning [23].

Following this comparative line, one review was found [4] in which TTNS was compared with diverse therapies, including 3/10 studies that compared simulated therapy, 4/10 anticholinergic, 1/10 exercise, 1/10 behavioral, and 1/10 two different stimulation sites. The three remaining studies compared TTNS with other treatments: extended-release oxybutynin vs. TTNS + fármacoM; TTNS vs. transcutaneous sacral foramina vs. combination of the two; bladder and pelvic floor training vs. TTNS.

By contrasting daily or weekly treatment [21] with TTNS, 100% of weekly participants completed the compliance and experience questionnaire, in comparison to 90.5% of patients on daily therapy [21]. Although 53% (18) gave as a result a moderate or significant improvement in symptoms for the global response assessment (GRA), 75% (13/20) of neurological patients with OAB and 36% (5/14) of patients with idiopathic OAB responded to the intervention [21].

With respect to adherence to treatment [5,17] with TTNS, one of the studies [5] established different reasons for discontinuity (in 70 participants): lack of symptom relief (70%); difficulty in complying (6%); becoming asymptomatic (8%). However, 16.9% (14) of patients continued treatment, with a mean follow-up of 39.3 months [5].

Meanwhile, a BMI of obesity (=30 kg/m2) was observed to be the only statistically significant variable predictive of failure in the response to PTNS (p = 0.002) [27]. Notably, after PTNS therapy, 66% (19/29) of participants informed of an improvement in their symptoms [27].

Some of the additional complications to those observed in the analysis of results [3,19,21,23,26,28,30,32] were urinary tract infections in 10/17 studies (peer comparisons revealed that OnabotulinumtoxinA was associated with a greater incidence of urine infections vs. placebo, sacral neurostimulation (SNS), and PTNS); ranking in order of fewest infections: first PTNS, second SNS, third placebo, and fourth OnabotulinumtoxinA. Further, urine retention with a need for intermittent catheterization was found in 11/17, with peer comparisons showing that OnabotulinumtoxinA was associated with a greater incidence of retention vs. placebo, SNS, and PTNS; ranking in order of lowest incidence: first SNM, second placebo, third PTNS, and fourth OnabotulinumtoxinA [30].

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to analyze the scientific evidence on the treatment of OAB with UI through procedures of PTNS, compared to TTNS, of the PTN. Nineteen studies were included, which analyze, observe, and compare these therapies with other methods, such as simulated treatment, placebo, anticholinergic or other drugs, sacral electrical stimulation, or vaginal electrical stimulation.

Among the studies whose intervention was based mainly on PTNS or TTNS therapy vs. another therapy, UI presented significant improvement when compared to placebo or simulated treatment [28,29,31]. Abulseoud A et al. [20] showed a significant improvement in the number of episodes of UI in combined groups of TTNS and trospium choloride compared to TTNS for eight weeks [20]. It is worth noting the significant improvements observed in the review by Veeratterapillay R et al. [31] in UUI after 12 weeks of treatment and two years of maintenance with PTNS therapy, unlike what was observed by Welk B et al. [22] in their RCT with PTNS therapy, with no significant differences between TTNS treatment compared to simulated therapy.

It is worth highlighting the improvements in UI reflected in the systematic review conducted by Booth J et al. [4], when combining TTNS therapy with pelvic floor exercises or behavioral treatment, as well as the results observed in the systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Wang M et al., as regards the reduction in the number of episodes of UI and UUI per day through PTNS therapy [32].

Apart from two studies analyzed [5,24], parameters related to frequency of urination, urgency of urination, and nocturia, as well as other symptoms of OAB such as voiding volume and urodynamic changes were included as variables and presented dissimilar results between studies.

In a recent study [10] from 2020, significant improvements were observed in the perception of quality of life of patients treated with TTNS and PTNS, with no differences between treatments [10].

By focusing on the quality of life observed in the studies analyzed, it is worth highlighting that all the experimental studies included provided data on this. Some of these studies [17,18,21,23] showed significant improvements in quality of life, through diverse questionnaires, after treatment with PTNS or TTNS, revealing that this improvement increased when TTNS was combined with trospium chloride, although the difference was not significant [20].

In 2013, Peters KM et al. [11] observed improvements in the quality of life of patients with OAB who were treated with PTNS, evaluated three years after treatment. In the present review, PTNS has been seen to present significant differences in quality of life when compared to vaginal electrostimulation [18], and it has been observed that there are significant differences in increased quality of life in both neurogenic and non-neurogenic OAB [23].

As for other parameters, it is worth noting the RCT of de Scaldazza CV et al. [18] in which significant differences were revealed in terms of the patient’s global perception in favor of the PTNS technique compared to vaginal electrostimulation.

Leroux PA et al. [5] in their study showed some of the reasons why there is discontinuity in treatment with TTNS therapy, the most prevalent of which, in 70% of cases, was sufficient relief from symptoms, while in 6% it was due to complications for compliance with the treatment, and in 8% it was due to a complete reduction of the symptoms and becoming asymptomatic [5].

Most of the studies included in this review report of the absence of adverse effects during treatment [5,17,18,20,22,24,25]. Studies that combine PTNS and TTNS therapy [17], and those in which TTNS therapy is involved [5,20,22,25], point out that there are no adverse effects after the use of this therapy, except for the study conducted by Moratalla-Charcos LM et al. [26], who speak of mild pain on plantar flexion after the use of this technique.

Regarding PTNS therapy, no serious adverse effects were found, only minor bleeding episodes were mentioned or mild discomfort at the needle insertion site [3,25,29], sometimes causing hematomas or paresthesia at the puncture site [31].

As for the electrical stimulation parameters with PTNS therapy, most studies referred to weekly sessions for 12 weeks as the time of treatment. Although some of them did not show the other parameters, the rest coincided with regard to sessions of 30 min duration, a frequency of 20 Hz, pulse of 200 ms, 34-gauge needle inserted approximately five cm above the medial malleolus, and electrode in ipsilateral calcaneus [17,19,22,23,27]. In terms of amplitude, this was increased to the level of discomfort of the patient, feeling of tickling on the sole of the foot, or flexion of the big toe.

Upon referring to treatment with TTNS therapy, the parameters between the studies are more variable: some of the studies mentioned the same stimulation parameters as those of PTNS therapy, while others varied in terms of frequency, using a frequency of 10 Hz, as was the case of the randomized clinical trial of Welk B et al. [22], also highlighting the frequency of weekly sessions, with a total of three weekly sessions for 12 weeks.

The experimental studies of Abulseoud A et al. [20] and Seth JH et al. [21] stand out due to the use of different parameters, with the former [20] using frequencies of 10 Hz, pulse of 250 ms, treatment three times a week for eight weeks, and with a stimulation time of 30 min. Meanwhile, in the latter study [21], they used amplitudes of 27 mA, pulse between 70 and 560 ms, which varied depending on patient tolerability, for 12 weeks, both daily and weekly. Mallman S et al. [24], in their RCT, showed a stimulus duration of 20 min with a follow-up of six weeks and a pulse duration of 300 ms.

5. Conclusions

It is complicated to be able to establish which electrical stimulation therapy of the PTN is the most effective for treatments of idiopathic OAB with UI in adults, as far as the different parameters observed in this review are concerned, due to the variability of the results obtained and the electrical stimulation parameters used in the studies included. Nevertheless, it is worth highlighting the advantages TTNS therapy presents with respect to PTNS therapy, as this could be more comfortable for the patient, all things being equal in the results variable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.-G. and M.A.-C.; methodology, A.A.-G., M.A.-C., and I.E.-P.; formal analysis, A.A.-G., I.E.-P., and M.A.-C.; investigation, A.A.-G., A.M.P.-L., M.B.-D., and M.J.C.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-G. and M.A.-C.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-G. and I.E.-P.; visualization, A.M.P.-L., M.B.-D., and M.J.C.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ICD-11-Mortality and Morbility Statistics. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Kobashi, K.; Nitti, V.; Margolis, E.; Sand, P.; Siegel, S.; Khandwala, S.; Newman, D.; MacDiarmid, S.A.; Kan, F.; Michaud, E. A Prospective Study to Evaluate Efficacy Using the Nuro Percutaneous Tibial Neuromodulation System in Drug-Naïve Patients with Overactive Bladder Syndrome. Urology 2019, 131, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Garcia, M.; Crampton, J. A single-blind, randomized controlled trial to valuate the effectiveness of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) in Overactive Bladder symptoms in women responders to percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS). Physiotherapy 2019, 105, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, J.; Connelly, L.; Dickson, S.; Duncan, F.; Lawrence, M. The effectiveness of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) for adults with overactive bladder syndrome: A systematic review. Neurol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leroux, P.A.; Brassart, E.; Lebdai, S.; Azzouzi, A.R.; Bigot, P.; Carrouget, J. Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation: 2 years follow-up outcomes in the management of anticholinergic refractory overactive bladder. World J. Urol. 2018, 36, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J.C.; Brenes, F.J.; Lizarraga, I.; Rejas, J.; Trillo, S.; Ochayta, D.; Arumi, D. Impacto del número de episodios diarios de incontinencia de urgencia en los resultados descritos por el paciente con vejiga hiperactiva. Actas Urol. Esp. 2016, 40, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milsom, I.; Coyne, K.S.; Nicholson, S.; Kvasz, M.; Chen, C.I.; Wein, A.J. Global prevalence and economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, R.; Linder, B.J. Evaluation and treatment of Overactive Bladder in Women. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings; Elsevier LTD: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 95, pp. 370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Valles-Antuña, C.; Pérez-Haro, M.L.; González-Ruiz de, L.C.; Quintás-Blanco, A.; Tamargo-Díaz, E.M.; García-Rodríguez, J.; San Martín-Blanco, A.; Fernandez-Gomez, J.M. Estimulación transcutánea del nervio tibial posterior en el tratamiento de la incontinecia urinaria de urgencia refractaria, de origen idiopático y neurogénico. Actas Urol. Esp. 2017, 41, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Fraguas, M.C.; Lastra-Barreira, D.; Blanco-Díaz, M. Neuromodulación periférica en el síndrome de vejiga hiperactiva en mujeres: Una revisión). Actas Urol. Esp. 2020, 45, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.M.; Carrico, D.J.; Wooldridge, L.S.; Miller, C.J.; MacDiarmid, S.A. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for the long-term treatment of overactive bladder: 3-year results of the STEP study. J. Urol. 2013, 189, 2194–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Grupo PRISMA. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet. 2014, 18, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cherghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Mosely, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Argimon Pallás, J.M.; Jimenez Villa, J. Metodos de Investigación Clinica y Epidemiológica, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; GØtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; Strobe Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, 1628–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramirez-García, I.; Blanco-Ratto, L.; Kauffmann, S.; Carralero-Martínez, A.; Sánchez, E. Efficacy of transcutaneous stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve compared to percutaneous stimulation in idiopathic overactive bladder syndrome: Randomized control trial. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019, 38, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaldazza, C.V.; Morosetti, C.; Giampieretti, R.; Lorenzetti, R.; Baroni, M. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus electrical stimulation with pelvic floor muscle training for overactive bladder syndrome in women: Results of a randomized controlled study. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2017, 43, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Preyer, O.; Umek, W.; Laml, T.; Bjelic-Radisic, V.; Gabriel, B.; Mittlboeck, M.; Hanzal, E. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus tolterodina for overactive bladder in women: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 191, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulseoud, A.; Moussa, A.; Abdelfattah, G.; Ibrain, I.; Saba, E.; Hassouna, M. Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve electrostimulation with low dose trospium chloride: Could it be used as a second line treatment of overactive bladder in females. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, J.H.; Gonzales, G.; Haslam, C.; Pakzad, M.; Vashisht, A.; Sahai, A.; Knowles, C.; Tucker, A.; Panicker, J. Feasibility of using a novel non-invasive ambulatory tibial nerve stimulation device for the home-based treatment of overactive bladder symptoms. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welk, B.; Mckibbon, M. A randomized, controlled trial of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation to treat overactive bladder and neurogenic bladder patients. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2020, 14, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudor, K.I.; Seth, J.H.; Liechti, M.D.; Ochulor, J.; Gonzales, G.; Haslm, C.; Fox, Z.; Pakzad, M.; Panicker, J.N. Outcomes following percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) treatment for neurogenic and idiopathic overactive bladder. Clin. Auton. Res. 2020, 30, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallmann, S.; Ferla, L.; Rodrigues, M.P.; Paiva, L.L.; Sanches, P.R.S.; Ferreira, C.F.; Ramos, J.G.L. Comparison of parasacral transcutaneous electrical stimulation and transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in women with overactive bladder syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 250, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salatzki, J.; Liechti, M.D.; Spanudakis, E.; Gonzalez, G.; Baldwin, J.; Haslam, C.; Pakzad, M.; Panicker, J.N. Factors influencing return for maintenance treatment with percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for the management of the overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2019, 123, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moratalla Charcos, L.M.; Planelles Gómez, J.; García Mora, B.; Santamaria Navarro, C.; Vidal Moreno, J.F. Efficacy and satisfaction with transcutaneous electrostimulation of the posterior tibial nerve in overactive bladder syndrome. J. Clin. Urol. 2018, 11, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.; Farhan, B.; Nguyen, N.; Ghoniem, G. Clinical outcomes of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in elderly patients with overactive bladder. Arab. J. Urol. 2019, 17, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wibisono, E.; Rahardjo, H.E. Effectiveness of Short Term Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation for Non-neurogenic Overactive Bladder Syndrome in adults: A Meta-analysis. Acta Med. Indones. 2015, 47, 188–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tutolo, M.; Ammirati, E.; van der Aa, F. What is New in Neuromodulation for Overactive Bladder? In European Urology Focus; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 4, pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C.W.; Wu, M.Y.; Yang, S.S.D.; Jaw, F.S.; Chang, S.J. Comparing the efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA, sacral neuromodulation, and peripheral tibial nerve stimulation as third line treatment for the management of overactive bladder symptoms in adults: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Toxins 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veeratterapillay, R.; Lavin, V.; Thorpe, A.; Harding, C. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation in adults with overactive bladder syndrome: A systematic review of the literature. J. Clin. Urol. 2016, 9, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jian, Z.; Ma, Y.; Jin, X.; Li, H.; Wang, K. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for overacttive bladder syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 2457–2471. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).