Abstract

Background/Objectives: Physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles remain leading behavioral risk factors for chronic disease across generations. Mothers with young children face unique barriers to exercise, including time constraints, fatigue, and limited access to supportive environments. Lion Hearts was developed to address these barriers through a family-centered, community-based approach that integrates physical activity, strength training, and health education. This protocol describes the systematic application of the Intervention Mapping (IM) framework to develop Lion Hearts, a multigenerational CrossFit-based program for mothers and children. Methods: Following the first four steps of the IM framework—needs assessment, matrices, intervention design, and program creation—behavioral determinants were identified through literature review, national data, and community input. The resulting 12-week program integrates twice-weekly family CrossFit sessions, monthly cardiovascular health workshops, and weekly home-based challenges delivered through local affiliates using a train-the-trainer model. Results: IM produced a theoretically grounded and evidence-based intervention targeting individual (self-efficacy, outcome expectations), interpersonal (modeling, relatedness), and environmental (access, social support) determinants. The process resulted in detailed logic models, behavior change matrices, and implementation materials, including family handbooks and coach guides. Conclusions: Lion Hearts represents a scalable, multigenerational approach to CVD prevention that leverages existing community fitness infrastructure. By embedding prevention within family systems and CrossFit affiliates, the program offers a sustainable, replicable model to enhance physical activity, strengthen family health behaviors, and reduce intergenerational CVD risk.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death among women in the United States, responsible for approximately one in every five female deaths [1]. The American Heart Association identifies motherhood as a vulnerable period that intensifies CVD risk factors, including reduced physical activity (PA) [2]. Maternal inactivity, obesity, and hypertension elevate women’s own CVD risk while simultaneously conferring intergenerational consequences: higher blood pressure, adverse lipid profiles, and lower fitness for their children [3,4]. Conversely, children who have physically active mothers mitigate these risk factors and are twice as likely to reach PA guidelines [5,6,7]. Addressing mothers’ PA levels during this life stage therefore represents an underutilized prevention opportunity with multigenerational implications [8].

Childhood represents a key developmental period for CVD prevention, as patterns of physical activity, fitness, and cardiometabolic health established early in life strongly influence risk trajectories into adulthood [9,10]. Consistent PA in this age group strongly predicts adult PA levels [11], yet fewer than one in four U.S. children consistently achieve the recommended 60 min of daily moderate-to-vigorous PA [12,13]. Mothers of young school-age children average some of the lowest levels of daily PA across the lifespan, with only 29.8% of U.S. mothers with pre-school children meeting the adult guideline of approximately 150 min/week of MVPA [14,15]. Likewise, researchers in the U.K. found that mothers with pre-school children achieved an average of 18 min/day of MVPA, while mothers with school-aged children averaged 26 min/day [16]. This inactivity heightens children’s risk for low activity levels, as maternal PA strongly predicts child PA through modeling and co-participation [17,18,19]. Despite this evidence, few interventions simultaneously engage mothers and children together in shared PA programming during this pivotal developmental stage [8,20].

Although aerobic PA receives the most attention in public health campaigns, muscle-strengthening activity remains especially low among women [21,22]. National surveillance data indicate that fewer than 26.9% of U.S. women meet the federal muscle-strengthening recommendation of two or more days per week, compared with roughly 35.2% of men [23]. This gap is even wider among mothers of young children, who cite fatigue, time constraints, and lack of access to supportive environments as primary barriers [24,25]. Strength-based exercise is critical for women’s cardiovascular and metabolic health, improving insulin sensitivity, body composition, and blood-pressure regulation while mitigating age-related muscle loss [26,27]. CrossFit offers an effective and scalable mode of strength training that combines aerobic and resistance exercise in time-efficient sessions [28,29]. These findings highlight a key opportunity to integrate strength training into maternal-focused prevention efforts.

Intergenerational interventions that engage parents and children together represent an especially powerful strategy for addressing sedentary behavior and promoting physical activity [30,31,32]. Such programs leverage reciprocal modeling and co-participation, where parents’ engagement enhances children’s motivation, and children’s enthusiasm reinforces parental adherence. This bidirectional influence fosters long-term behavior change and reduces sedentary time across generations, producing sustained improvements in both physical and psychosocial health. Family-centered interventions provide a promising but underused strategy to disrupt intergenerational CVD risk. Engaging mother–child dyads offers reciprocal motivation, accountability, and social support while fostering family cohesion [5,6,7]. However, existing programs are often resource-intensive, limited to clinical or school-based settings, and rarely engage children and mothers in non-aerobic-based activities such as skill and strength-based training [33]. This gap is critical, as early exposure to diverse, strength- and skill-based activities supports physical literacy, enhances body composition, and builds confidence for sustained engagement in PA [34,35].

Community fitness spaces—particularly CrossFit affiliates—represent a scalable, underused platform for family-centered prevention. CrossFit emphasizes functional movement, measurable progress [36], and social connection [37], features strongly associated with long-term adherence [37,38]. Affiliates provide accessible community hubs where mothers and children can participate together, overcoming common barriers to PA adherence such as cost, childcare, and social isolation. Specialty programs such as CrossFit Kids [39] offer developmentally appropriate training for children aged 4–11, making affiliates uniquely equipped to deliver safe, engaging, and scalable interventions for families [40,41]. Unlike traditional fitness centers such as the YMCA, which often separate adults and children through childcare services, CrossFit affiliates promote shared participation—allowing parents and children to train side by side—thereby strengthening family modeling, cohesion, and mutual motivation.

Despite decades of PA promotion research, few interventions target the mother–child dyad as the unit of change, with even fewer integrating cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), body composition, and cardiometabolic biomarkers alongside behavioral outcomes as indicators of effectiveness [42,43,44]. Rigorous, theory-driven frameworks such as Intervention Mapping (IM) [45] are needed to bridge this gap and design interventions that are not only effective but also implementable in real-world community settings [20]. The Lion Hearts intervention applies IM to develop a community-based, multigenerational program for CVD prevention. Lion Hearts directly targets mother–child dyads, embedding prevention in CrossFit affiliates to create sustainable, socially supported change. Thus, the goals of this paper were to describe the IM process used to develop Lion Hearts, outline the application of IM theoretical foundations to Lion Hearts, and describe its utility as a replicable model for reducing intergenerational CVD risk.

Lion Hearts is a 12-week, family-centered CrossFit program designed to improve cardiovascular health and physical activity among mothers and their children. The intervention combines twice-weekly functional fitness sessions, monthly cardiovascular health workshops, and weekly home-based challenges delivered through local CrossFit affiliates. Rather than testing intervention efficacy, this paper focuses on the formative development phase of Lion Hearts, following the first four steps of the IM framework. The goal is to document how theory, evidence, and community input were systematically integrated to produce an evidence-based, family-centered program ready for future implementation and evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Study Design

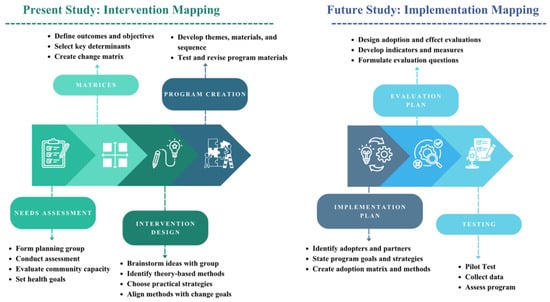

This study used the IM framework to guide the development of Lion Hearts, a multigenerational PA intervention for CVD prevention in mother–child dyads. IM integrates empirical evidence, behavioral theory, and implementation considerations to produce theoretically grounded, evidence-based programs suitable for real-world delivery. The first four IM steps (needs assessment, matrices, intervention design, program creation) were completed to develop and refine Lion Hearts, with implementation planning and evaluation (Steps 5 and 6) to follow in future phases. Figure 1 provides an outline of the IM steps applied in this study.

Figure 1.

Study Steps Outline. Overview of the Intervention Mapping process applied to the Lion Hearts program. The “present study” encompasses Steps 1–4 (Needs Assessment, Matrices, Intervention Design, and Program Creation), describing the development of Lion Hearts. “Future studies” will address Steps 5–6 (Implementation Planning and Evaluation) to refine, implement, and assess the intervention in community settings.

2.2. Research Context

Lion Hearts was designed in response to the need for family-centered CVD prevention strategies embracing the potential of community fitness settings—particularly CrossFit affiliates—as delivery platforms. The program was developed over a 3-month period through a collaborative process led by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in exercise science, health behavior change, CVD prevention, and community-based research. Team members met regularly to ensure consistent application of IM principles and to integrate diverse perspectives.

2.3. Planning Team Eligibility and Recruitment

The planning group consisted of faculty researchers (n = 4), community-based fitness professionals (n = 2), and mothers with lived experience in family-based health programs (n = 4). Advisory input was provided by local CrossFit affiliate owners (n = 2) who contributed expertise in functional training, class structure, and community engagement. Faculty researchers guided the theoretical alignment with Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Determination Theory, and Family Systems Theory, while graduate and undergraduate students supported literature reviews, data synthesis, and curriculum drafting. Mothers provided essential insights into family routines, barriers to participation, and motivational strategies for sustaining activity at home, ensuring that program content reflected real-world family dynamics. Fitness professionals and affiliate owners reviewed exercise selection, scaling options, and logistical considerations such as space, safety, and scheduling. This diverse composition ensured representation from both academic and community stakeholders, enabling the development of a program that is theoretically grounded, culturally relevant, and practically feasible for delivery in community fitness settings.

2.4. Theories, Models, and Frameworks for Implementation Strategies

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [46] informed strategies to enhance observational learning, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations within family contexts. The emphasis on reciprocal interactions among personal, behavioral, and environmental domains guided the selection of determinants and behavior change techniques. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [47] provided the framework for designing activities that foster autonomy, competence, and relatedness to support intrinsic motivation, ensuring both mothers and children experienced meaningful engagement in health behaviors. Family Systems Theory (FST) [48] highlighted the importance of family dynamics, communication, and shared goal setting. This perspective informed strategies to strengthen family cohesion and sustain behavioral changes across generations.

2.5. Intervention Mapping (IM) Steps

IM guided the systematic development of the Lion Hearts program. Step 1 (Needs Assessment) involved creating a Logic Model of the Problem through a comprehensive problem analysis. This process included a literature review (2010–2025) of family-based physical activity and CVD prevention interventions, analysis of national surveillance data (CDC, NHANES, American Heart Association), and review of local community health assessments and facility inventories. This review synthesized key evidence on family-based physical activity, cardiovascular disease prevention, and intergenerational health promotion to identify behavioral determinants and environmental barriers relevant to mothers and children. In accordance with IM procedures, these findings are integrated within the Results Section rather than presented as a separate systematic review.

In Step 2 (Matrices), performance objectives were defined according to Intervention Mapping guidelines by specifying the concrete actions that mothers and children would need to perform to achieve the desired behavioral outcomes (e.g., adopting sustainable physical activity routines). The IM team, guided by Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Determination Theory, and Family Systems Theory, translated each overarching behavior into measurable, observable steps reflecting autonomy, competence, relatedness, and self-efficacy. Environmental outcomes were developed in parallel to identify the conditions within CrossFit affiliates necessary to support these behaviors. These included coach practices, facility adaptations, and community supports that foster modeling, accessibility, and consistent family participation. Both sets of objectives were finalized through consensus among academic researchers, community fitness professionals, and parent advisors to ensure ecological validity and alignment with real-world implementation contexts.

In Step 3 (Intervention Design), the IM team designed the Lion Hearts program, specifying frequency of sessions, integration of educational components, and strategies to overcome identified barriers by leveraging community facilitators through a CrossFit affiliate setting. Step 4 (Program Creation) undertook the development of materials to support a train-the-trainers model, including mother and child handbooks, coach implementation guides, and structured curricula to prepare CrossFit coaches to deliver the program effectively. All materials were designed to be evidence-based, visually engaging, culturally sensitive, and literacy-appropriate to ensure accessibility. Future steps (Steps 5 and 6) will employ implementation mapping within a community-based participatory research framework to refine components with stakeholder input, identify adoption and sustainability strategies, and evaluate both implementation outcomes (e.g., reach, fidelity, sustainability) and participant outcomes (e.g., PA, cardiovascular health, psychosocial well-being).

3. Results

The Lion Hearts development process successfully completed Steps 1–4 of the IM framework, resulting in a theoretically grounded, evidence-based intervention package designed for multigenerational CVD prevention in mother–child dyads. The Results Section summarizes the primary outputs generated from the first four steps of the Intervention Mapping (IM) framework. Because this paper describes the program development phase rather than implementation or evaluation, “results” refer to the key deliverables and decisions emerging from each step—namely, (1) the Logic Model of the Problem identifying determinants of inactivity among mothers and children, (2) the Logic Model of Change and behavior matrices translating these determinants into actionable objectives, (3) the design and structure of the 12-week Lion Hearts program, and (4) the creation of implementation materials including participant handbooks, coach guides, and child workbooks. These outputs collectively represent the evidence-based foundation for subsequent implementation and evaluation phases.

3.1. Step 1: Logic Model of the Problem

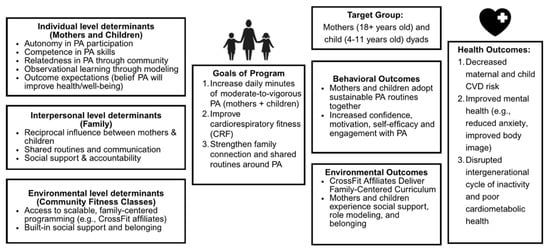

The needs assessment synthesized findings from national surveillance data, local community health reports, and an extensive literature review of family-based physical activity interventions. Analyses confirmed low adherence to physical activity guidelines in the target population, with only 23 percent of adults and 20 percent of children in the U.S. meeting PA recommendations [49]. Cardiovascular disease risk factors were prevalent in both groups, and barriers such as cost, transportation, and lack of family-friendly programming were consistently reported. The resulting Logic Model of the Problem identified determinants at individual (e.g., low self-efficacy, limited knowledge), interpersonal (e.g., lack of modeling and support), and environmental (e.g., limited access, affordability) levels (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Logic Model of the Problem. The Logic Model of the Problem illustrates how individual, interpersonal, and environmental determinants contribute to low physical activity among mothers and children. These multilevel factors inform the Lion Hearts program goals and expected behavioral and health outcomes, including increased family activity, improved fitness, and reduced intergenerational risk for inactivity and poor cardiometabolic health.

3.2. Step 2: Logic Model of Change and Performance Objectives

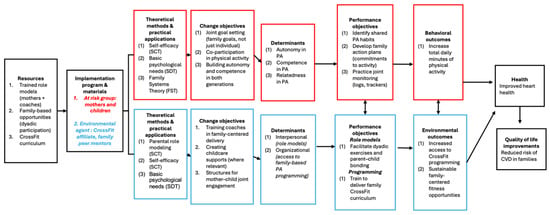

Based on identified determinants, a Logic Model of Change was created to specify desired outcomes and performance objectives for both mothers and children. For mothers, these included leading and participating in family PA, setting shared health goals, and modeling healthy behaviors. For children, objectives included active participation in family sessions, engaging in independent activity, developing movement skills, and understanding the importance of cardiovascular health. Matrices of change objectives linked each performance objective to its corresponding determinants, providing a clear framework for selecting behavior change techniques (see Table 1 and Figure 3).

Table 1.

Logic Model of Change and Performance Objectives.

Figure 3.

Lion Hearts Implementation Mapping Logic Model. Logic model outlining the Lion Hearts two-generation implementation strategy. The model maps resources, theoretical methods, change objectives, determinants, performance objectives, and expected behavioral and environmental outcomes leading to improved physical activity and cardiometabolic health among mothers and children in community CrossFit settings.

3.3. Step 3: Program Design

Lion Hearts will be structured as a 12-week program with three integrated components designed to support family health and engagement. Twice weekly, families will participate in 60 min CrossFit Sessions that incorporate functional movement, cardiovascular training, strength, and flexibility training activities scaled appropriately for mothers and children. Once a month, families will attend a 90 min Cardiovascular Health Education Workshop located at their local CrossFit affiliate, which will offer interactive learning on CVD risk, the benefits of physical activity, goal setting, and strategies for building supportive home environments. To extend the program beyond structured sessions, weekly Home-Based Family Challenges will encourage shared goals, reinforce skills, and promote family enjoyment. The overall design emphasizes developmental appropriateness, collaborative goal setting, and intrinsic motivation to build sustained engagement and long-term commitment to healthier lifestyles.

Unlike standard CrossFit or CrossFit Kids programming, Lion Hearts uniquely integrates family co-participation and cardiovascular education to promote both physical and relational health. Rather than focusing solely on performance or individual progression, the program emphasizes shared goal setting, maternal modeling, and home-based reinforcement to strengthen healthy habits within the family system. By merging the community-driven culture of CrossFit with evidence-based behavioral strategies, Lion Hearts represents a novel, family-centered approach to building cardiovascular fitness and lasting health behaviors across generations.

Each Lion Hearts session was designed to align with core CrossFit principles—functional movement, scalability, and community support—while incorporating behavioral strategies derived from Social Cognitive Theory and Self-Determination Theory. Families attend two 60 min CrossFit sessions per week, led by certified CrossFit coaches who have completed a Lion Hearts orientation on family-centered delivery, child safety, and motivational communication. Each session follows a consistent structure (see Table 2). Supervision is provided by a lead certified CrossFit coach, supported by trained assistants (e.g., service-learning students or staff) in a 1:6 coach-to-family ratio to maintain safety and engagement. Coaches receive ongoing mentorship from affiliate owners and the research team to ensure fidelity through checklists, observation forms, and monthly supervision calls.

Table 2.

Overview of Lion Hearts Weekly CrossFit Sessions (Step 3: Program Design).

3.4. Step 4: Program Production

Comprehensive program materials were developed to ensure consistency, accessibility, and family engagement across all components of Lion Hearts. Participant handbooks outline the structure of the 12-week program, including weekly schedules, progress-tracking tools, and practical tips for building active routines at home. Child-friendly workbooks incorporate age-appropriate illustrations, reflection prompts, and goal-tracking charts to support motivation and comprehension among younger participants. Coaching manuals provided by CrossFit offer standardized guidance on delivering CrossFit sessions, ensuring fidelity to safety, developmental appropriateness, and scalability for both mothers and children. The educational component of Lion Hearts includes monthly 90 min Cardiovascular Health Workshops and weekly Home-Based Family Challenges, each mapped to IM-identified behavioral determinants.

Workshop topics progress across the 12-week program to build cardiovascular literacy and self-regulatory skills (see Table 3). All content is included in the Lion Hearts family handbook and child workbook, designed with age-appropriate visuals, reflection prompts, and progress-tracking charts. Coaches receive a parallel implementation guide with step-by-step session outlines, cueing tips, and discussion questions to promote consistent delivery across affiliates.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular Health Workshops and Home-Based Family Challenges.

3.5. Steps 5–6: Implementation Mapping

Consistent with IM guidelines, the next phase of Lion Hearts will involve implementation mapping to collaboratively refine and finalize delivery strategies, adoption supports, and evaluation procedures before testing the program in community settings. Implementation mapping will engage coaches, mothers, and affiliate owners to adapt materials, determine recruitment and retention strategies, and establish feasible assessment protocols. Following this participatory process, a mixed-methods evaluation will be conducted to assess feasibility, fidelity, and preliminary effectiveness across behavioral, physiological, and psychosocial domains. Table 4 outlines the anticipated health and implementation measures to be considered during this next phase. These indicators reflect the proposed framework that will be reviewed and adapted through implementation mapping prior to launch.

Table 4.

Anticipated Health and Implementation Measured for Implementation Mapping Phase.

4. Discussion

This paper described the systematic application of the IM framework to develop Lion Hearts, a multigenerational, community-based physical activity intervention for CVD prevention. The findings of this formative research demonstrate how the structured application of the IM framework can translate theoretical constructs into a practical, community-based intervention. By explicitly connecting behavioral determinants identified in Step 1 to performance and environmental objectives (Step 2) and then operationalizing those objectives through program design (Step 3) and material production (Step 4), Lion Hearts provides a replicable model for developing multigenerational interventions that are both evidence-informed and implementation-ready.

The systematic needs assessment confirmed that low PA levels and high CVD risk factors are prevalent among mothers and children and that barriers such as cost, scheduling conflicts, and lack of family-friendly facilities limit engagement in PA. The Logic Model of the Problem and Logic Model of Change developed through IM provided a clear blueprint for addressing these determinants. Program design and material production emphasized scalability, developmental appropriateness, and family-centered engagement, positioning Lion Hearts for successful implementation in community fitness facilities such as CrossFit affiliates.

A unique strength of Lion Hearts is its scaling potential through existing infrastructure. CrossFit affiliates—numbering more than 10,000 across 150 countries [50]—provide a ready-made, community-based delivery system for family-centered prevention. Unlike traditional fitness centers, affiliates emphasize functional, scalable programming [36] and incorporate movements such as lifting, squatting, and carrying. These movements translate directly to the physical demands of daily motherhood and help to reduce musculoskeletal injury risk and enhance strength and cardiorespiratory fitness [29,51,52], which are key physiological predictors of CVD morbidity and mortality [53]. Additionally, many coaches pursue certifications such as CrossFit Kids [39], equipping them to deliver age-appropriate programming for children while simultaneously engaging adults. This dual capacity allows mothers and children to train side by side, embedding role modeling and shared routines while reducing barriers related to childcare, cost, and scheduling. By leveraging a workforce and infrastructure that already exists, Lion Hearts bypasses the resource-intensive process of building new delivery systems, offering a replicable model that embeds cardiovascular prevention directly within trusted community hubs.

Despite the promise of leveraging CrossFit affiliates as community delivery platforms, several considerations affect the feasibility and accessibility of Lion Hearts and similar programs. First, program costs—including facility access, coach training, and participant fees—can limit scalability in underserved or rural areas. To mitigate these challenges, Lion Hearts incorporates a train-the-trainer model, allowing existing coaches to be trained in family-centered delivery with minimal added expense and no new infrastructure. Additionally, partnerships with schools, community centers, and local sponsors can offset participation costs and increase reach among families who may not traditionally access CrossFit facilities. Geographic availability also presents a barrier, as CrossFit affiliates are unevenly distributed across communities. Integrating program delivery into shared-use spaces and leveraging mobile or pop-up formats may help address this limitation. Finally, accessibility for families of varying fitness levels and abilities remains essential. To enhance inclusivity, Lion Hearts emphasizes movement scaling, supportive coaching, and culturally responsive materials to ensure safe, developmentally appropriate participation. These considerations will be systematically examined during future implementation mapping and pilot testing to inform sustainable scale-up.

Although the IM framework has been widely used to develop family- and school-based health interventions, Lion Hearts advances this body of work by extending IM into a novel community fitness context. Previous IM-based family interventions have primarily targeted diet or general lifestyle education within clinical or educational settings, often emphasizing aerobic activity or parental guidance rather than co-participation [54,55,56]. In contrast, Lion Hearts applies IM to design a multigenerational, strength-based program delivered through existing CrossFit affiliates. This approach expands the ecological scope of IM by integrating behavioral science with community fitness infrastructure, thereby enhancing scalability and accessibility.

This development phase produced a comprehensive intervention package; however, implementation planning and evaluation design (Steps 5 and 6 of IM) remain future work. These steps will be undertaken through implementation mapping guided by a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach. By actively involving mothers, youth, fitness coaches, and community partners as equal collaborators, CBPR will ensure that adoption, delivery, and evaluation strategies are contextually relevant, culturally appropriate, and sustainable [57,58]. This participatory process will enhance local ownership and capacity, increasing the likelihood that Lion Hearts can be maintained and scaled after the research phase ends. Framing Steps 5 and 6 as a collaborative process acknowledges that even the most theoretically sound and evidence-based programs can falter without alignment to community realities [20]. Implementation mapping with CBPR will allow the intervention to be adapted for logistical feasibility, integrate local insights into recruitment and retention strategies, and establish realistic evaluation metrics that capture both health outcomes and implementation success.

The intergenerational design of Lion Hearts addresses sedentary behavior at both individual and family levels by aligning motivation, accountability, and environmental support across generations. By encouraging mothers and children to move together, the program transforms daily routines into shared opportunities for physical activity, strengthening family cohesion while promoting lifelong movement habits. Future research will focus on co-developing implementation protocols, training and supporting delivery staff, and establishing robust evaluation procedures to assess both proximal health changes (e.g., PA levels, cardiovascular indicators) and long-term maintenance. Rigorous mixed-methods evaluation will also explore mechanisms of change and contextual factors influencing outcomes. In this way, Lion Hearts lays the groundwork for a future community-owned program that may contribute to healthier behaviors and reductions in cardiovascular risk across generations once implemented and empirically evaluated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and J.G.; methodology, J.W.; investigation, J.W., J.G. and K.M.; resources, J.W.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W., J.G. and K.M.; writing—review and editing, D.D. and D.S.D.; visualization, J.W. and J.G.; supervision, D.S.D.; project administration, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pennsylvania State University (STUDY00027631 on 10 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| CRF | Cardiorespiratory Fitness |

| IM | Intervention Mapping |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| FST | Family Systems Theory |

| CBPR | Community-Based Participatory Research |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity |

References

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2021 Update. Circulation 2021, 143, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L.S.; Warnes, C.A.; Bradley, E.; Burton, T.; Economy, K.; Mehran, R.; Safdar, B.; Sharma, G.; Wood, M.; Valente, A.M.; et al. Cardiovascular Considerations in Caring for Pregnant Patients: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e884–e903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpka, S.; Macdonald-Wallis, C.; Hughes, A.D.; Chaturvedi, N.; Franks, P.W.; Lawlor, D.A.; Fraser, A. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Offspring Cardiac Structure and Function in Adolescence. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Lv, A.; Aihemaitijiang, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. The association of maternal gestational weight gain with cardiometabolic risk factors in offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e106–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T.L.; Møller, L.B.; Brønd, J.C.; Jepsen, R.; Grøntved, A. Association between parent and child physical activity: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julius, B.R.; O’Shea, A.M.; Francis, S.L.; Janz, K.F.; Laroche, H. Leading by Example: Association Between Mother and Child Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2021, 33, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Brage, S.; Cooper, C.; Godfrey, K.M.; Harvey, N.C.; Inskip, H.M.; Robinson, S.M.; Van Sluijs, E.M. The association between maternal-child physical activity levels at the transition to formal schooling: Cross-sectional and prospective data from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.J.; Collins, C.E.; Lubans, D.R.; Callister, R.; Lloyd, A.B.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Burrows, T.L.; Barnes, A.T.; Pollock, E.R.; Fletcher, R.; et al. Twelve-month outcomes of a father–child lifestyle intervention delivered by trained local facilitators in underserved communities: The Healthy Dads Healthy Kids dissemination trial. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eggum, N.D. Emotion-Related Self-Regulation and Its Relation to Children’s Maladjustment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A Developmental Perspective on the Role of Motor Skill Competence in Physical Activity: An Emergent Relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telama, R. Tracking of Physical Activity from Childhood to Adulthood: A Review. Obes. Facts 2009, 2, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2019; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Katzmarzyk, P.; Denstel, K.D.; Carlson, J.; Crouter, S.E.; Greenberg, J.; Pate, R.R.; Sisson, S.B.; Staiano, A.E.; Stanish, H.I.; Ward, D.S.; et al. The 2022 United States Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth; Physical Activity Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bellows-Riecken, K.H.; Rhodes, R.E. A birth of inactivity? A review of physical activity and parenthood. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.M.; Bianchi, S.M. Exercise Time: Gender Differences in the Effects of Marriage, Parenthood, and Employment. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 66, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.F.; Hesketh, K.R.; Crozier, S.R.; Baird, J.; Cooper, C.; Godfrey, K.M.; Harvey, N.C.; Westgate, K.; Inskip, H.M.; van Sluijs, E.M. The association between number and ages of children and the physical activity of mothers: Cross-sectional analyses from the Southampton Women’s Survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.A.; Rhodes, R.E. Parental correlates in child and adolescent physical activity: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, S.L.; Rhodes, R.E. Parental Correlates of Physical Activity in Children and Early Adolescents. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.L.Y.; Tang, T.C.W.; Chung, J.S.K.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Capio, C.M.; Chan, D.K.C. Parental Influence on Child and Adolescent Physical Activity Level: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.; Streight, E.; Cheng, S.; Rhodes, R.E. Parents’ experiences of family-based physical activity interventions: A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2025, 22, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in strength training—United States, 1998–2004. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2006, 55, 769–772. [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzo, J.L. Narrative Review of Sex Differences in Muscle Strength, Endurance, Activation, Size, Fiber Type, and Strength Training Participation Rates, Preferences, Motivations, Injuries, and Neuromuscular Adaptations. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 494–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). QuickStats: Percentage* of Adults Aged ≥18 Years Who Met the Federal Guidelines for Muscle-Strengthening Physical Activity,† by Age Group and Sex—National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- Brown, W.J.; Heesch, K.C.; Miller, Y.D. Life Events and Changing Physical Activity Patterns in Women at Different Life Stages. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 37, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Boudreau, P.; Josefsson, K.W.; Ivarsson, A. Mediators of physical activity behaviour change interventions among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 15, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenowatz, C.; Sui, X.; Fritz, S.; Lavie, C.J.; Beattie, P.F.; Church, T.S.; Blair, S.N. The association between resistance exercise and cardiovascular disease risk in women. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, A.E.; Boyer, W.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Laddu, D.; Lobelo, F.; Lee, D.C.; McDermott, M.M.; Swift, D.L.; Webel, A.R.; Lane, A. Resistance Exercise Training in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease: 2023 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e217–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagener, S.; Hoppe, M.W.; Hotfiel, T.; Engelhardt, M.; Javanmardi, S.; Baumgart, C.; Freiwald, J. CrossFit®—Development, Benefits and Risks. Sports Orthop. Traumatol. 2020, 36, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goins, J.M. Physiological and Performance Effects of Crossfit. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mailey, E.L.; Huberty, J.; Irwin, B.C. Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Web-Based Physical Activity Intervention for Working Mothers. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Hollman, H.; Sui, W. Family-based physical activity interventions and family functioning: A systematic review. Fam. Process 2024, 63, 392–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, D.S.; Hausenblas, H.A. Women’s Exercise Beliefs and Behaviors During Their Pregnancy and Postpartum. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2004, 49, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Cronin, J.B.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Haff, G.G.; Howard, R.; Kraemer, W.J.; Micheli, L.J.; Myer, G.D.; Oliver, J.L. National Strength and Conditioning Association Position Statement on Long-Term Athletic Development. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1491–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Myer, G.D. Resistance training among young athletes: Safety, efficacy and injury prevention effects. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.E.; Stodden, D.F.; Barnett, L.M.; Lopes, V.P.; Logan, S.W.; Rodrigues, L.P.; D’Hondt, E. Motor Competence and its Effect on Positive Developmental Trajectories of Health. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrossFit Training. Level 1 Training Guide, 3rd ed.; CrossFit LLC: Boulder, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lautner, S.C.; Patterson, M.S.; Spadine, M.N.; Boswell, T.G.; Heinrich, K.M. Exploring the social side of CrossFit: A qualitative study. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2021, 25, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman-Sandland, J.; Hawkins, J.; Clayton, D. The role of social capital and community belongingness for exercise adherence: An exploratory study of the CrossFit gym model. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CrossFit Education. Crossfit Kids Certificate Course; CrossFit LLC: Boulder, CO, USA; Available online: https://www.crossfit.com/certificate-courses/online-kids (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Claudino, J.G.; Gabbett, T.J.; Bourgeois, F.; Souza, H.D.S.; Miranda, R.C.; Mezêncio, B.; Soncin, R.; Cardoso Filho, C.A.; Bottaro, M.; Hernandez, A.J.; et al. CrossFit Overview: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianzina, E.A.; Kassotaki, O.A. The benefits and risks of the high-intensity CrossFit training. Sport Sci. Health 2019, 15, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, D.L.; Johannsen, N.M.; Lavie, C.J.; Earnest, C.P.; Church, T.S. The Role of Exercise and Physical Activity in Weight Loss and Maintenance. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 56, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, D. Effects of aerobic exercise on lipids and lipoproteins. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.M.; Bogart, K.R.; Logan, S.W.; Case, L.; Fine, J.; Thompson, H. Physical Activity Participation of Disabled Children: A Systematic Review of Conceptual and Methodological Approaches in Health Research. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, L.K.B.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.; Fernández, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior, 1st ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, W.H. Family Systems. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Friel, C.P.; Duran, A.T.; Shechter, A.; Diaz, K.M. U.S. Children Meeting Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep Guidelines. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrossFit LLC. CrossFit Affiliate List. Available online: https://www.crossfit.com/map (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Fernández, J.F.; Solana, R.S.; Moya, D.; Marin, J.M.S.; Ramón, M.M. Acute Physiological Responses During Crossfit® Workouts. Eur. J. Human Mov. 2015, 35, 114–124. Available online: https://www.eurjhm.com/index.php/eurjhm/article/view/362 (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Rios, M.; Pyne, D.B.; Fernandes, R.J. The Effects of CrossFit® Practice on Physical Fitness and Overall Quality of Life. Int J Environ Res. Public Health 2024, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Blair, S.N.; Arena, R.; Church, T.S.; Després, J.P.; Franklin, B.A.; Haskell, W.L.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Levine, B.D.; Lavie, C.J.; et al. Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134, e653–e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.G.; Watkins, J.M.; Goss, J.M.; Craig, D.W.; Waggoner, Z.; Martinez Kercher, V.M.; Kercher, K.A. Intervention Mapping for Refining a Sport-Based Public Health Intervention in Rural Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Craemer, M.; De Decker, E.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verloigne, M.; Duvinage, K.; Koletzko, B.; Ibrügger, S.; Kreichauf, S.; Grammatikaki, E.; Moreno, L.; et al. Applying the Intervention Mapping protocol to develop a kindergarten-based, family-involved intervention to increase European preschool children’s physical activity levels: The ToyBox-study. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stea, T.H.; Haugen, T.; Berntsen, S.; Guttormsen, V.; Øverby, N.C.; Haraldstad, K.; Meland, E.; Abildsnes, E. Using the Intervention Mapping protocol to develop a family-based intervention for improving lifestyle habits among overweight and obese children: Study protocol for a quasi-experimental trial. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, J.M.; Greeven, S.J.; Heeter, K.N.; Brunnemer, J.E.; Otile, J.; Solá, P.A.F.; Dutta, S.; Hobson, J.M.; Evanovich, J.M.; Coble, C.J.; et al. Human-centered participatory co-design with children and adults for a prototype lifestyle intervention and implementation strategy in a rural middle school. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinsen, A.; Berg, A.; Nielsen, S.; Trewella, K.; Cronin, T.J.; Pace, C.C.; Pang, K.C.; Tollit, M.A. Co-design methodologies to develop mental health interventions with young people: A systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2025, 9, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).