Abstract

Using the concept of category, we provide some insight into and prove an intrinsic property of the category AprS of approximation spaces and continuous functions. We also introduce rough closure and rough interior operators to characterize clopen topologies. Our main result proves the equivalence of several categories, including the category of equivalence relations and relation-preserving functions, the category of rough interior spaces and continuous functions, the category of rough closure spaces and continuous functions, and the category AprS. This work provides a deeper understanding of the interplay among rough set theory, information systems, and category theory.

Keywords:

rough sets; approximation spaces; equivalence relations; information systems; clopen topologies MSC:

03E99; 54C05; 54C10; 54E99; 91B06

1. Introduction

Rough set theory (RST), introduced by Pawlak [1], is intrinsically a study of an equivalence relation [2]. The theory originates from the concept of an approximation space , where U is a universe of objects and t is an equivalence relation on U. From the topological point of view, the Pawlak lower and upper approximations correspond, respectively, to the interior and closure functions in a clopen topology (a topology on a set is called a clopen topology if every member of is both open and closed) with the base (a base for a topological space is a set of open sets such that every member of can be expressed as a union of members of ; we say that the base generates the topology ). the set of all distinct t-equivalence classes. Consequently, there exists a natural bijection between the clopen topologies on a set U and the approximation spaces over U.

On the other hand, categories are rich algebraic structures that provide a unified framework for abstraction. Recently, Borzooei et al. [3] considered the class of approximation spaces and discussed some categories of lower, upper, and natural approximations without using many topological structures of spaces. However, their approach, which deliberately avoids deep topological machinery, has limitations in deriving more powerful categorical results. The need for a categorical framework grounded in topology is growing.

The classical Pawlak model offers a foundational framework for reasoning about uncertainty and indiscernibility, but its reliance on equivalence relations imposes a rigid partition structure, which is inadequate for dynamic or complex data. To address these limitations, rough set theory has expanded beyond equivalence-based granulations. One major direction replaces equivalence relations with arbitrary binary relations, tolerance relations, or neighborhood systems [4], enabling more flexible representations of similarity and proximity. Notable developments include generalized approximation spaces based on overlapping subset neighborhoods and overlapping containment rough neighborhoods. In fact, a rich interplay with topology has emerged. Topological tools, open sets, -open sets, and covering-based neighborhoods have been used to generate new rough models and to analyze arbitrary relations [5]. Concepts such as separation axioms and covering properties further refine granularity and relational structure. Together, these relational and topological generalizations demonstrate the field’s evolution toward more adaptable and mathematically integrated frameworks.

Against this backdrop, a rigorous categorical foundation for the classical equivalence-based setting remains essential. This work addresses this need by developing a topological interpretation of the standard rough set model. We advance this direction by systematically exploiting the topological structures inherent in rough set theory. In particular, we define the category AprS of approximation spaces and continuous functions. By introducing the notions of rough closure and rough interior operators, we provide an operator-theoretic characterization of clopen topologies. This framework reveals the intrinsic topological structure underlying Pawlak’s model and establishes a stable categorical foundation from which broader generalizations can be developed in a systematic and unified manner. Our overarching goal is to achieve a coherent categorical interpretation of rough set theory.

Our main result establishes the equivalence of four categories: the category AprS of approximation spaces and continuous functions; the category Equiv of equivalence relations and relation-preserving functions; the category of rough interior spaces and continuous functions; and the category of rough closure spaces and continuous functions.

We organize the paper as follows. Section 2 presents the necessary preliminaries, including approximation spaces, information systems, and basic topological notions. In particular, we review closure and interior operators and equivalent characterizations of continuity, which serve as foundational tools for later sections. In Section 3, we introduce rough closure and rough interior operators and show that they yield an operator-theoretic characterization of clopen topologies. We study minimal clopen neighborhoods, analyze union- and intersection-preserving operators, and characterize continuity between clopen spaces via these rough operators. Section 4 defines several categories that naturally arise from the rough set theory, including categories of approximation spaces, equivalence relations, rough closure spaces, and rough interior spaces. We prove that these categories are mutually equivalent, providing structurally identical perspectives on rough approximations. We also examine the connection between approximation spaces and information systems by introducing a subcategory of information systems with non-expansive O–A–D homomorphisms and constructing functors linking it to the category of approximation spaces. Section 5 reviews related categorical approaches to rough sets and compares our framework with existing ones, highlighting key conceptual and structural differences. Finally, Section 6 concludes with remarks on the significance of established categorical equivalences and outlines directions for future research, including further applications of categorical methods to rough set theory and information systems.

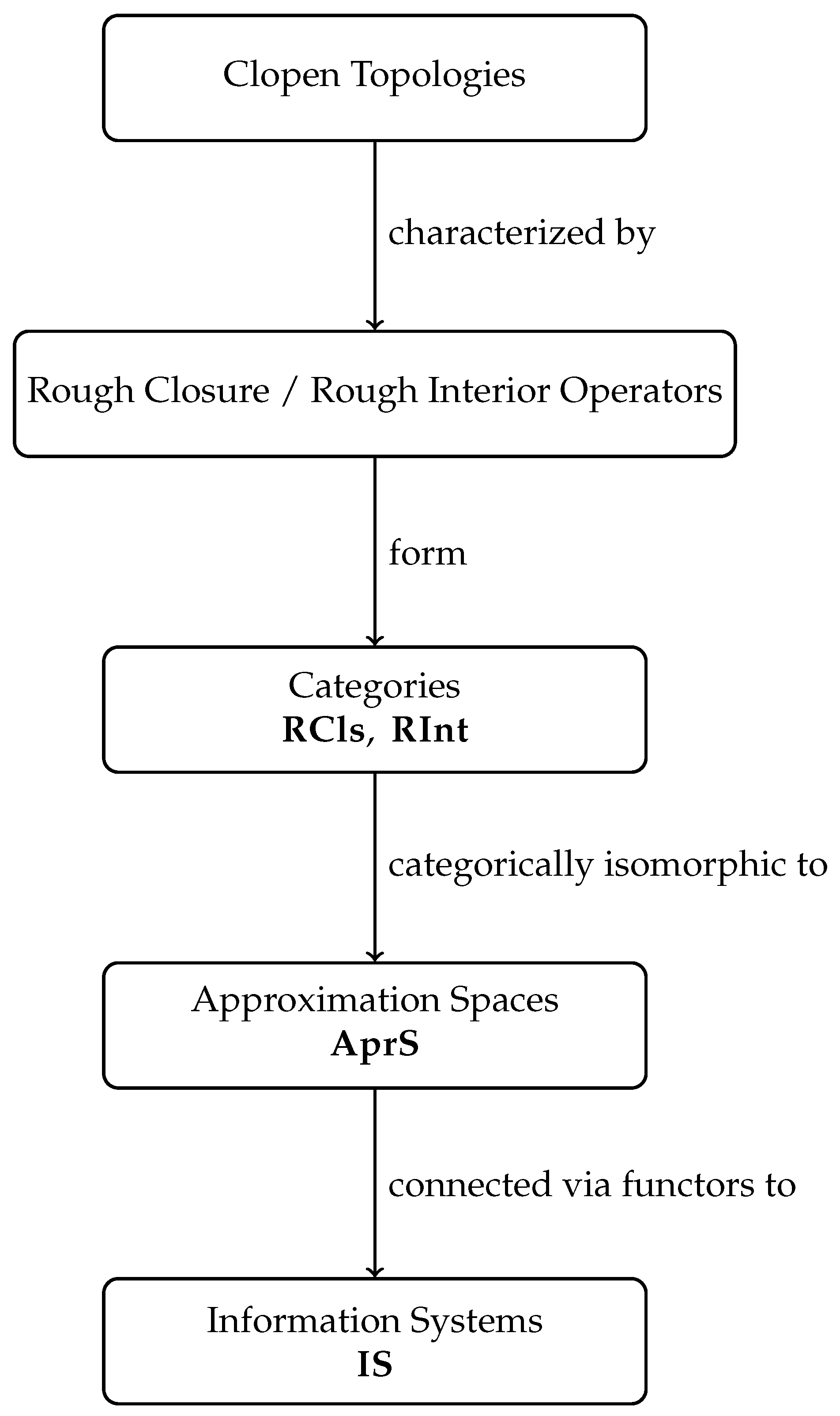

More precisely, we provide the following conceptual flowchart of the paper (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The diagram presents the conceptual structure of the paper in a top-down manner. Clopen topologies are characterized by rough closure and interior operators. These operators naturally form the categories and , which have been shown to be categorically isomorphic to the category of approximation spaces . Approximation spaces are linked to information systems through appropriate functors.

2. Preliminaries

This section recalls the basic concepts and notations that will be used throughout this paper. We begin with the fundamental notion of equivalence relations and their induced structures, then review essential set-theoretic operators, closure and interior spaces, topological spaces and continuity, and finally, approximation spaces and information systems in the context of rough set theory.

We shall denote the power set of a set U (i.e., the set of all subsets of U) by . A function from the power set of U to itself is also called an operator on U. The dual of the operator is the operator defined by

and hence

For an equivalence relation t on U and an element , we denote by the t-equivalence class of u, i.e., . The set of all distinct t-equivalence classes, denoted , is a partition of U and is called the quotient set of U modulo t.

2.1. Images and Preimages

Assume that is a function from a set U to a set V. We shall use the notations and to denote, respectively, the image of and the preimage of under the function f.

The preimage operator commutes with all basic set operations. Specifically, for any , the preimage of B is the complement of the preimage of the complement of B as follows:

and hence

These properties will be useful when studying continuity and approximations.

2.2. Closure and Interior Spaces

A closure operator on a set U is a function from the power set of U into itself that satisfies the following four conditions (known as the Kuratowski closure axioms): (it preserves the empty set), (it is extensive), (it is idempotent), and (it preserves binary unions) for every . The pair is called a closure space.

The notion of an interior operator is dual to that of a closure operator. An interior operator on U is a function that satisfies the dual interior axioms (called the Kuratowski interior axioms) as follows: (it preserves the total space), (it is intensive), (it is idempotent), and (it preserves binary intersections) for every . The pair is called an interior space. The following lemma relates closure and interior operators via preimages.

Lemma 1.

Let and be closure spaces. Assume that and are the interior operators corresponding to and , respectively, and that f is a function from U to V. The following statements are equivalent.

- (1)

- For each subset B of V, .

- (2)

- For each subset B of V, .

The proof is provided in Appendix B.

2.3. Topological Spaces and Continuity

A topological space can be described equivalently in terms of closure, interior, or neighborhood systems. For a subset , and represent the closure of A and the interior of A, respectively. The closure function

associated with each subset , with its closure satisfying the Kuratowski closure axioms.

Dually, the interior function

satisfies the Kuratowski interior axioms.

A set N in is a neighborhood of a point if and only if (shortened iff) N contains an open set to which u belongs, i.e., . The set of all neighborhoods of u is called the neighborhood system of u and is denoted by . The neighborhood function

satisfies the four neighborhood axioms [6]. It is an easy fact that for each subset , a point iff for every neighborhood N of u for closure operators. We therefore have the following.

Topologies are usually given in terms of open sets. As is well known [6,7], a topological space can be equivalently defined by a closure space, or an interior space, or a neighborhood function. This leads us to study the topological structure from different points of view.

A localized form of continuity in terms of neighborhoods may be stated as follows.

Definition 1.

Let U and V be topological spaces. A function is continuous at , iff for each neighborhood M of there is a neighborhood N of u such that . We say is continuous if f is continuous at every .

Proposition 1

([6]). Assume that U and V are topological spaces, and that f is a function from U into V. The following statements are equivalent.

- (1)

- The function f is continuous.

- (2)

- The preimage of each open set is open.

- (3)

- For each , the image of its closure is contained in the closure of its image.

- (4)

- For each , the closure of its preimage is contained in the preimage of its closure.

2.4. Approximation Spaces

An approximation space is a pair where U is a universe and t is an equivalence relation on U. The upper and lower approximations, and , of a set are defined, respectively, as follows [1]:

The upper approximation operator is a closure operator and satisfies

for all , i.e., the upper approximation operator is union preserving (a union-preserving operator on a set U is a function if it satisfies the property: for all .). The upper and lower approximation operators satisfy

or equivalently,

The last two equations imply that for every ,

Lemma 2.

If is an approximation space then the set of all subsets X of U for which is the same as the set of all subsets X of U for which . In other words, the topology

is clopen.

Proof.

Since, in a given approximation space , the upper and lower approximation operators are dual and the upper approximation satisfies the Kuratowski closure axioms, it follows that

is a topology on U. It follows immediately from (13) that

is clopen. □

2.5. Information Systems

As rough set theory is applied to data analysis, an approximation space is usually induced from information systems. According to [1], an information system (also called knowledge representation systems, data tables, or attribute–value systems) is defined as a tuple , where U is a nonempty finite set, called the universe; A is a nonempty finite set of primitive attributes; for each , is the domain of values for a; and for each , is the information function for the attribute a. To simplify the presentation, we can identify each attribute a with its information function and set . Then, an information system is simply a triplet , where A is a set of functions from U to D. Given an information system and a subset of attributes , the indiscernibility relation with respect to B is defined as Obviously, for each , is an approximation space. In particular, we can associate with each information system its finest approximation space , where . On the other hand, given an approximation space , we can (somewhat trivially) associate with it a single-attribute information system , where is the quotient set of U modulo t and .

In [8], homomorphisms between information systems are introduced. Given two information systems and , an O-A-D homomorphism from to is a triple of functions , where

- is the object mapping.

- is the attribute mapping.

- is the domain mapping.

such that

for any and .

The definitions of categories and functors are defined in Appendix A.

Remark 1.

From a categorical standpoint, information systems and their associated rough structures are unified by the notion of granulation. The equivalence of the proposed categories demonstrates that rough approximations, topological structures, and equivalence relations encode the same informational content at different levels of abstraction.

In this sense, the categorical framework does not replace information systems but rather clarifies their structural essence, enabling principled transformations and deeper theoretical insight.

3. Characterizations of Clopen Topologies

In this section, we restrict our study to clopen topological spaces. Unless otherwise stated, we shall assume throughout that is a clopen topological space. To better understand its structure, we begin with the notion of minimal clopen neighborhoods, then move on to continuous functions between such spaces, and finally connect these ideas to closure operators that naturally arise in rough set theory.

3.1. Minimal Clopen Neighborhoods

Recall [9] that an Alexandrov space is a topological space in which arbitrary intersections of open sets are open, or equivalently, every point has a minimal open neighborhood including it. It is clear that clopen topological spaces are Alexandrov spaces. Thus, in a given clopen topological space , every point has a minimal clopen neighborhood including it. We shall show that for every , is the minimal clopen neighborhood of u.

We now show that for every , the set serves as this minimal clopen neighborhood. From (5), we have for each ,

and . Hence is the minimal clopen neighborhood of u. Consequently, the neighborhood system of u is the set of all supersets of . Namely,

We next show that for , and are either identical or have no elements in common. On the contrary, assume that

It follows that is a nonempty clopen subset of and so . We have

consequently, the set includes u and is a clopen subset of . This is impossible since is a minimal clopen set including u. Therefore, and are either identical or have no elements in common. We thus obtain

Proposition 2.

Let be a clopen topological space. For a subset A of U, denotes the closure of A in . Then the following properties hold:

- (1)

- For each , is the minimal clopen neighborhood of u.

- (2)

- For , and are either identical or disjointed.

Since, in a given clopen topological space , the closure of a singleton is a minimal clopen set including u it follows that if then and have no elements in common. This gives

From (7), (16), and (17), we obtain for every ,

We clearly have, for any ,

i.e., the closure function is union preserving.

Lemma 3.

Let be a clopen topological space. For a subset A of U, denotes the closure of A in . Then the closure function is union preserving and satisfies the Kuratowski closure axioms.

3.2. Continuous Functions Between Clopen Topological Spaces

Having established the structure of minimal clopen neighborhoods, we now turn to the behavior of functions between clopen spaces. The continuity of a function can be characterized in terms of these closures. Assume that and are clopen topological spaces, and that f is a function from U to V. Denote by and the closure functions in and in , respectively. For each and , let and be the neighborhood systems of u in and of v in , respectively. Then, from (16), we obtain

According to Definition 1, is continuous, iff

We note in connection with (17) that

This, together with Lemma 1 and Proposition 1, gives the following:

Proposition 3.

Assume that and are clopen topological spaces, and that f is a function from U to V. Let and denote the closure functions in and in , respectively. Assume that and are the interior functions in and in , respectively. The following statements are equivalent.

- (1)

- The function f is continuous.

- (2)

- For each , .

- (3)

- For all , implies .

- (4)

- The preimage of each open set is open.

- (5)

- For each , .

- (6)

- For each , .

In other words, continuity can be equivalently expressed in several ways, including the preservation of closures of singletons, the preservation of open sets under preimages, and compatibility with interior operators. These equivalences are summarized in Proposition 3, which provides a robust characterization of continuous functions between clopen spaces.

3.3. Clopen Topologies and Rough Closure Operators

Note that a union-preserving operator preserves empty unions and binary unions. Thus, any extensive, idempotent, and union-preserving operator on a given set U is a closure operator and defines the topology on U. We establish the following equivalent condition of a clopen topology.

Proposition 4.

Let U be a given set. Assume that is an extensive and idempotent union-preserving operator, and that its dual interior operator. Let

Then is a clopen topology iff

or equivalently,

Proof.

We have seen that is a topology. Consequently, is a clopen topology iff

Since is extensive, it is easily seen from (1) that is intensive. This gives

Assume that is a clopen topology. From (26), we obtain for every

Since is idempotent, we have for every , ; by the clopen property, must be open; therefore, from (1), (2), and (29), we obtain

This proves that .

Conversely, assume that (24) holds.

Proposition 4 motivates us to define the notions of rough closure operators and rough interior operators as follows:

Definition 2.

Let U be a given set. An extensive and idempotent union-preserving operator on U will be called a rough closure operator on U if it satisfies

The pair is called a rough closure space. Dually, an intensive and idempotent intersection-preserving operator (an intersection-preserving operator on a set U is a function if its dual operator is union preserving). on U will be called a rough interior operator on U if it satisfies

The pair is called a rough interior space.

For a given set U, it follows from Proposition 4 and Definition 2 that any rough closure operator defines the clopen topology

on U. Conversely, let be a given clopen topological space. Since the closure function in satisfies the Kuratowski closure axioms, it follows from (19) that is a rough closure operator on U. Accordingly, a clopen topological space can be equivalently defined by a rough closure space, or a rough interior space.

4. Some Categories Equivalent to the Category Clop

In this section, we define the category of approximation spaces and continuous functions, the category Equiv of equivalence relations and relation-preserving functions, the category RCls of rough closure spaces and continuous functions, and the category RInt of rough interior spaces and continuous functions. We prove that Equiv, AprS, RCls, and RInt are mutually equivalent. Furthermore, we define the category of information systems and O-A-D homomorphisms. We establish the relationship between IS and AprS by considering a subcategory NeIS of information systems non-expansive O-A-D homomorphisms.

Given a clopen topological space , let

Then the relation

is an equivalence relation on U, called the kernel relation of S. From (17), we obtain

This gives

This section demonstrates that the category of clopen topological spaces is not isolated, but rather equivalent to multiple other categories, each offering a different perspective on the same underlying structure.

4.1. The Category of Approximation Spaces

For a given set U, it follows from (18), (19), and (32) that every clopen topological space becomes an approximation space via the restriction of its closure function to the set of singletons:

Conversely, it follows from Lemma 2 that every approximation space determines a clopen topology on U via its upper approximation operator . This establishes a bijective correspondence between clopen topologies on U, and approximation spaces . Accordingly, a clopen topological space can be equivalently defined as an approximation space . Hence from statement (2) of Proposition 3, we obtain the following:

Proposition 5.

Define the category

AprS

with objects’ approximation spaces , where U is a set and t is an equivalence relation on U. Morphisms are continuous functions, i.e., functions such that

Then the categories

AprS

and

Clop

are isomorphic.

4.2. The Category of Equivalence Relations

Rydeheard and Burstall [10] considered the category Rel whose objects are pairs of the form where U and R are sets such that R is a binary relation on U, i.e., , and whose morphisms are relation-preserving functions; that is, functions such that

Considering the category Rel, we can define a second category Equiv of equivalence relations and relation-preserving functions, which is the subcategory of Rel with objects being ordered pairs , where U is a set and t is an equivalence relation on U, and morphisms are relation-preserving functions.

From § 4.1 and statement (2) of Proposition 3, we obtain the following:

Proposition 6.

The categories

Equiv

and

Clop

are isomorphic.

4.3. The Categories of Rough Closure and Rough Interior Spaces

Let us define the category RCls as the category whose objects are rough closure spaces , where U is a set and is a rough closure operator on U. Morphisms are continuous functions, i.e., functions such that

or equivalently, for all .

As it is shown in § 3.3, a clopen topological space can be equivalently defined as a rough closure space . Hence from statement (2) of Proposition 3, we obtain the following:

Proposition 7.

The categories

RCls

and

Clop

are isomorphic.

Of course, since rough closure spaces and rough interior spaces are equivalent concepts. The category of rough interior spaces RInt has rough interior spaces as its objects. Morphisms are continuous functions; i.e., functions such that

Proposition 8.

The categories RInt

and

Clop

are isomorphic.

4.4. The Category of Information Systems

The category of information systems has information systems as its objects and O-A-D homomorphisms as its morphisms. We say that an O-A-D homomorphism is non-expansive if its attribute mapping is onto it. To establish the relationship between and , we consider a subcategory whose objects are information systems and morphisms are non-expansive O-A-D homomorphisms. Then, it is easy to see that, if is a non-expansive O-A-D homomorphism between information systems and , then is a relation-preserving function between approximation space and by using (14). Hence, we can define a functor

by setting and

On the other hand, let be a relation-preserving function. Then, we can define a non-expansive O-A-D homomorphism by setting , , and for any . It is obvious that is non-expansive and satisfies the homomorphic condition (14). Thus, we can define a functor

by setting and

We can see that

but does not hold. This means that an information system is more informative than the finest approximation space derived from it. Indeed, we can usually induce the same approximation space from several different information systems by using different sets of attributes, and this is the main idea of attribute reduction in rough set theory.

Together, these categories, , , , , and , are equivalent to , showing that clopen topologies can be studied from multiple perspectives: relational, algebraic, and informational.

4.5. Practical Applications

The equivalence of , , , , and allows us to switch between relational, algebraic, and topological languages depending on the problem. The study of these categories offers several possible practical benefits:

- Attribute Reduction and Feature SelectionThe functorial relationship between IS and AprS formalizes the process of attribute reduction by demonstrating that different attribute sets can induce isomorphic approximation spaces. This provides a principle, category-theoretic justification for feature selection algorithms. Formally, a subset of attributes constitutes a reduct if the induced approximation space is isomorphic to in the category AprS [11]. Practically, this enables the systematic identification of minimal attribute sets that preserve the original classification power, facilitating efficient preprocessing and dimensionality reduction without compromising approximation capability [12]. The functor , which maps multiple information systems to the same approximation space, justifies algorithmic searches for minimal isomorphic representations, ensuring that the underlying knowledge, encoded topologically, remains invariant during the reduction process [13].

- Data Integration and System InteroperabilityMorphisms in Equiv and AprS define rigorous, structure-preserving transformations between heterogeneous data sources. A morphism guarantees that objects indistinguishable in the source domain remain indistinguishable in the target domain, thereby maintaining classification consistency during data migration [14,15]. This formalism finds critical application in database schema mapping, ontology alignment, federated databases, multi-source data fusion, and knowledge graph transformation [16]. The framework serves as a powerful validation tool: if a proposed data mapping fails to be continuous, it indicates a potential distortion of the original indiscernibility classes, signaling the risks of classification errors and guiding the design of more robust integration pipelines [17].

- Topological Analysis of Discrete DataThe isomorphism between AprS and Clop enables the powerful application of topological methods to discrete datasets structured via equivalence relations. Since the induced clopen topologies are Alexandrov spaces, tools from algebraic topology—such as homology and persistent homology—can be employed to analyze global connectivity and shape in discrete settings [18,19]. This connection yields concrete analytical benefits: topological connectedness corresponds to irreducible data clusters, allowing the decomposition of datasets into independent, lossless components for optimized storage and processing [20]. Furthermore, equivalence classes form minimal clopen neighborhoods, defining sets of topologically indistinguishable objects for robust, neighborhood-based classification. The rough closure operator, defined as , provides a natural mechanism for approximate query matching by identifying all objects that share equivalence classes with query elements [21].

- Formal Specification of Knowledge-Preserving MappingsThe categorical framework provides an explicit, mathematical definition for what it means for a mapping between systems to “preserve knowledge.” This formalism guides the principled design of interoperable software in domains such as ontology alignment, database schema mapping, and knowledge graph transformation [22]. The correspondence between rough closure operators and clopen topologies offers a systematic methodology for engineers to construct application-specific approximation models by designing appropriate union-preserving operators [23]. Crucially, the equivalence demonstrates that four distinct mathematical representations—equivalence relations (Equiv), approximation operators (AprS), closure operators (RCls), and interior operators (RInt)—encode identical informational content, allowing practitioners to select the most convenient or efficient representation for their specific task with guaranteed semantic consistency [24].

- Algorithmic Optimization and Efficient ComputationThe mathematical properties, revealed by the categorical equivalence, directly enable practical algorithm design and optimization for large-scale data processing. The union-preserving property of rough closure operators, expressed as , permits the parallel computation of approximations and supports efficient incremental updates, significantly enhancing scalability [25]. Propositional characterizations of continuity provide multiple equivalent verification conditions, allowing algorithm designers to select the most computationally efficient method to ensure structure preservation in data transformations [21]. The representational flexibility afforded by the framework allows practitioners to leverage equivalence relations for database normalization, approximation operators for boundary region analysis, closure operators for topological reasoning, or interior operators for definability analysis, with results seamlessly transferring across these perspectives [26]. This flexibility underpins optimization strategies that search for minimal isomorphic representations, improving both storage efficiency and processing speed in practical implementations [27].

The established categorical equivalence provides a rigorous mathematical foundation that effectively bridges abstract theory and practical application. By facilitating seamless transitions between relational, algebraic, and topological perspectives, it delivers principled mechanisms for attribute reduction, novel methodologies for the topological analysis of discrete data, formal specifications for designing knowledge-preserving systems, and optimized algorithms for large-scale data processing [28]. This unified framework demonstrates that rough set theory, when interpreted through a categorical lens, offers not only profound mathematical insight but also directly applicable, operational tools for addressing contemporary, data-driven challenges across science and engineering [29].

5. Related Works

While rough set theory has been extensively studied from diverse perspectives, a limited number of works have investigated its structure from a categorical perspective. In [3], three categories of approximations, denoted by , , and , are defined. Objects of the three categories, as well as our definition of , are all approximation spaces. However, the corresponding morphisms preserve not only the underlying equivalence relation but also lower and/or upper approximations. These morphisms are called lower/upper transformations, although they are simply morphisms instead of natural transformations in the sense of category theory. More precisely, let and be two approximation spaces. Then, a function is called a lower and upper natural transformation if it satisfies, for any ,

and

respectively. In addition, f is simply a natural transformation if it is both a lower and upper natural transformation. It is shown that a lower natural transformation preserves equivalence classes ([3], Proposition 2.4). On the other hand, they also proved that a mapping is an upper natural transformation iff it preserves equivalence classes ([3], Theorem 3.4). This indicates that a lower natural transformation is automatically an upper natural transformation, although it is generally not the case. Because a function-preserving equivalence class is necessarily relation-preserving (but not conversely), the categories introduced in [3] impose a much stricter restriction on morphisms than ours. As a result, all three categories in [3] are subcategories of (or equivalently, or ) in this paper.

Unlike the categories defined in [3] and this paper, categories of rough sets also exist where the objects are not limited to approximation spaces. The earliest categorical analysis of rough sets is the category ROUGHdefined in [30]. Objects of ROUGH are triples , where is an approximation space and . Let and denote the quotient sets of and , respectively. Then, a morphism in ROUGH is a map such that . Thus, morphisms of ROUGH must preserve lower approximations.

Yet another category of rough sets is based on the algebraic interpretation of rough sets [31]. A pair is called a rough universe in [31], where U is the domain and B is a subalgebra of the power set Boolean algebra . Any pair such that and is an I-rough set of . Then, the category RSC has all I-rough sets as its objects and a morphism is simply a function such that [32]. While ROUGH and RSC appear different at first glance, they are shown to be equivalent in [32].

A subcategory of ROUGH, called -ROUGH, is defined to have the same objects as ROUGH, but its morphisms must satisfy the additional condition of preserving the boundary region. That is, is a morphism of -ROUGH if it is a morphism of ROUGH satisfying . Analogously, -RSC is the subcategory of RSC with the same collection of objects and its morphisms are RSC morphisms satisfying . It is shown that -ROUGH and -RSC are equivalent and both are equivalent to Set2, whose objects are pairs of sets and morphisms are pairs of functions where and . The result shows that the role of approximation spaces has become hardly visible in the categories of algebraic rough sets. By contrast, our categories of approximation spaces, rough closure spaces, and rough interior spaces arise from a topological interpretation of rough sets. Hence, approximation spaces and continuous functions between them play the major role in such categories. In some sense, this means that categories based on -rough sets somewhat lose structural information behind the construction of rough approximations.

6. Conclusions

By introducing the concepts of rough closure and rough interior operators, and leveraging the power of functors, we have established the categorical equivalence of

- The category of approximation spaces and continuous functions.

- The category of equivalence relations and relation-preserving functions.

- The category of all rough interior spaces and continuous functions.

- The category of rough closure spaces and continuous functions.

Our approach of using information systems to characterize the category of approximation space and its subcategory gives rise to a deeper insight of the interplay among rough set theory, information systems, and category theory. It gives us not only a better understanding of the rough set theory structures in the context of category theory but also the relationships of different categories arising from some topological tools. By using the concepts of categories, one can derive further useful properties and applications of rough set theory. Category theory provides a powerful, uniform language for describing how mathematical structures transform via structure-preserving maps. It allows us to articulate the preservation of structural behavior across different domains. However, the abstract nature of category theory, which deliberately ignores the specific sets, operations, and axioms defining the objects, means that a deep understanding of the underlying technical details remains crucial. This knowledge is essential for exploring the full implications of the proven results and for driving further theoretical developments and applications. We plan to pursue these promising research directions in future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-R.S., C.-J.L. and E.-B.L.; Methodology, Y.-R.S., C.-J.L. and E.-B.L.; Validation, Y.-R.S. and E.-B.L.; Formal analysis, Y.-R.S., C.-J.L. and E.-B.L.; Investigation, Y.-R.S., C.-J.L. and E.-B.L.; Resources, Y.-R.S., C.-J.L. and E.-B.L.; Writing—original draft, Y.-R.S. and E.-B.L.; Writing—review and editing, C.-J.L. and E.-B.L.; Supervision, E.-B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NSTC of Taiwan (grant number 113-2221-E-001-018-MY3 and 113-2221-E-001-021-MY3) and by MOST of Taiwan (grant number 119-2221-E-150-028).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Appendix A. Categories Defined

A category is a class of objects together with a family of disjoint sets , for each ordered pair of objects. The function is expressed for , and call f a morphism of with source A and target B. Given each pair , of morphisms, there is a unique morphism , called the composite of f and g. The composition is associative, and each object has an identity morphism that serves as a unit under composition [33].

A subcategory of is category whose objects are objects of and whose morphisms are morphisms of with the same identities and composition of morphisms.

A morphism in a category is called an isomorphism, and A and B are said to be isomorphic in , iff it has an inverse morphism, i.e., if there is a unique morphism with and .

In what follows, a full subcategory of is a subcategory of such that

The following are some examples of small categories:

- The category of sets and functions has objects including all sets , and morphisms of all (total) functions from A into B with the usual composition.

- The category of topological spaces and continuous functions.

- The category of clopen topological spaces and continuous functions.

The category is a full subcategory of the category .

References

- Pawlak, Z. Rough sets. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 1982, 11, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y. Topological and fuzzy rough sets. In Intelligent Decision Support—Handbook of Applications and Advances of the Rough Sets Theory; Slowinski, R., Ed.; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Borzooei, R.A.; Estaji, A.A.; Mobini, M. On the category of rough sets. Soft Comput. 2017, 21, 2201–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syau, Y.R.; Lin, E.B.; Liau, C.J. Neighborhood Systems and Variable Precision of Generalized Rough Sets. Fundam. Informaticae 2017, 153, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-shami, T.M. Topological approach to generate new rough set models. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 4101–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.L. General Topology; Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Day, M.M. Convergence, closure, and neighborhoods. Duke Math. J. 1944, 11, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymala-Busse, J.W. Algebraic properties of knowledge representation systems. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGART International Symposium on Methodologies for Intelligent Systems (ISMIS’86), Knoxville, TN, USA, 22–24 October 1986; pp. 432–440. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, F.G. Alexandroff spaces. Acta Math. Univ. Comen. 1999, LXVIII, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rydeheard, D.; Burstall, R. Computational Category Theory; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron, A.; Rauszer, C. The discernibility matrices and functions in information systems. In Intelligent Decision Support; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 331–362. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; An, J.; Wu, Y. A comparative study of algebra viewpoint and information viewpoint in attribute reduction. Fundam. Informaticae 2005, 68, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, P.; Slezak, D. Foundations of rough sets from vagueness perspective. In Rough Sets and Intelligent Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Polkowski, L. Rough Sets: Mathematical Foundations; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y. Granular computing on binary relations I: Data mining and neighborhood systems. In Rough Sets in Knowledge Discovery; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Calegari, S.; Ciucci, D. Integrating fuzzy logic in ontologies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Paphos, Cyprus, 23–27 May 2006; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewski, R.; Wasilewski, P.; Slezak, D.; Szczuka, M. Functors among categories of information systems, approximation spaces, and their morphisms. Fundam. Informaticae 2014, 135, 465–487. [Google Scholar]

- Breiner, A.; Kaliszewski, S.; Porter, T. Topology and Its Applications in Data Science; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edelsbrunner, H.; Harer, J. Computational Topology: An Introduction; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Munkres, J.R. Topology, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, F.Y. Reduction and axiomization of covering generalized rough sets. Inf. Sci. 2007, 177, 3500–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euzenat, J.; Shvaiko, P. Ontology Matching; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, G.; Ciucci, D. Algebraic structures for rough sets. In Transactions on Rough Sets II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 208–252. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvinen, J. Lattice theory for rough sets. In Transactions on Rough Sets VI; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 400–498. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.J.; Zhang, W.X. Rough approximation operators in covering approximation spaces. In Rough Sets and Current Trends in Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliani, P.; Chakraborty, M.K. A Geometry of Approximation: Rough Set Theory: Logic, Algebra and Topology of Conceptual Patterns; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Slezak, D. Rough sets and Bayes factor. In Transactions on Rough Sets III; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 202–229. [Google Scholar]

- Düntsch, I.; Gediga, G. Rough Set Data Analysis: A Road to Non-Invasive Knowledge Discovery; Methodos Publishers: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, Z.; Skowron, A. Rudiments of rough sets. Inf. Sci. 2007, 177, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M.; Chakraborty, M.K. A category for rough sets. Found. Comput. Decis. Sci. 1993, 18, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Iwinski, T.B. Algebraic approach to rough sets. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Math. 1987, 35, 673–683. [Google Scholar]

- More, A.K.; Banerjee, M. Categories and algebras from rough sets: New facets. Fundam. Informaticae 2016, 148, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLane, S. Categorical algebra. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1965, 71, 40–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.