Abstract

Continual Generalized Category Discovery (C-GCD) is an emerging research direction in Open-World Learning. The model aims to incrementally discover novel classes from unlabeled data while maintaining recognition of previously learned classes, without accessing historical samples. The absence of supervision signal in incremental sessions makes catastrophic forgetting more severe than in traditional incremental learning. Existing methods primarily enhance generalization through single-modality contrastive learning, overlooking the natural advantages of textual information. Visual features capture perceptual details such as shapes and textures, while textual information helps distinguish visually similar but semantically distinct categories, offering complementary benefits. However, directly obtaining category descriptions for unlabeled data in C-GCD is challenging. To address this, we introduce a conditional prompt learning mechanism to generate pseudo-prompts as textual information for unlabeled samples. Additionally, we propose a dual-modal contrastive learning strategy to enhance vision-text alignment and exploit CLIP’s multimodal potential. Extensive experiments on four benchmark datasets demonstrate that our method achieves competitive performance. We hope this work provides new insights for future research.

Keywords:

open-world learning; generalized category discovery; continual learning; contrastive learning; CLIP MSC:

68T07; 68T10; 68T30

1. Introduction

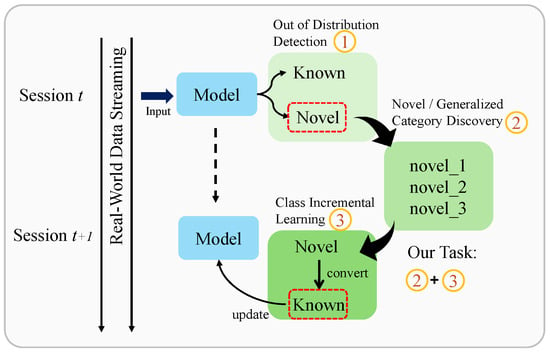

Traditional machine learning systems operate under the closed-set assumption, where the environment is static and the model remains fixed after deployment. However, this assumption is violated in real-world applications, where environments are inherently dynamic and uncertain. To address this limitation, Open-World Learning (OWL) [1] has emerged as a new paradigm that enables models to operate safely and evolve continuously through three integrated capabilities: rejecting unknown instances, discovering novel categories, and learning incrementally. Figure 1 illustrates the complete open-world learning pipeline. Unlike out-of-distribution (OOD) detection [2], which simply rejects unknown samples, open-world learning requires models to semantically cluster novel samples into distinct categories. This challenge is addressed by Novel/Generalized Category Discovery (N/GCD) [3,4]. And then, discovered categories are incorporated into the model through class incremental learning (CIL) [5], completing the learning cycle.

Figure 1.

Overview of the open-world learning life cycle. Our work focuses on continual Generalized Category Discovery, which integrates Generalized Category Discovery and incremental learning.

This paper focuses on Continual Generalized Category Discovery (C-GCD) [6,7], which extends GCD to continual settings. The model first acquires foundational knowledge through supervised training on labeled old classes in an offline session. It then proceeds through sequential online sessions containing unlabeled data with predominantly novel classes and sparse known class samples. Crucially, all learning proceeds entirely without supervision, and data from previous sessions are inaccessible [8], simulating autonomous learning of AI agents in real-world scenarios. The objective is to discover novel classes while preserving recognition capability for all previously learned classes.

C-GCD is essentially unsupervised continual learning. Unlike supervised continual learning [9], where labeled data provides explicit guidance, C-GCD operates without supervision throughout all online sessions. This characteristic causes the model to naturally adapt its representations in the direction of gradient descent during training [10]. Consequently, when novel class samples vastly outnumber old class samples, the model tends to misclassify old samples as novel classes, resulting in task-level overfitting. Furthermore, without supervisory signals, decision boundaries become increasingly blurred as online sessions progress, as confirmed by our baseline experiments (Section 4).

Existing C-GCD methods [6,7,11,12] primarily operate within a single visual modality framework. Despite leveraging visual features extracted from self-supervised vision transformers (ViT) such as DINO [13], these methods exhibit limitations in effectively generalizing visual concepts. Recent studies [14,15] have shown that adding simple textual descriptions such as “a photo of [class]” can significantly improve classification performance. This improvement can be attributed to the fact that although certain classes exhibit visual ambiguity, their corresponding textual descriptions typically encode more discriminative features. An intuitive approach is to leverage image descriptions to provide pseudo-supervision for the corresponding images, thereby enhancing novel class discovery and mitigating catastrophic forgetting. The advantage of this approach is that the supervision information not only alleviates the previously mentioned task-level overfitting and boundary degradation, but the cross-entropy loss also achieves higher performance than non-parametric classifiers. However, a key limitation is that C-GCD cannot directly access category information from unlabeled data, which hinders existing frameworks from effectively leveraging multimodal information.

To address this limitation, we propose DMCL, a prompt-based framework that leverages Dual-Modal Contrastive Learning with multimodal self-distillation. Our framework operates in two stages. In the first stage, we introduce a prompt generation network that synthesizes textual descriptions for training images. Inspired by conditional prompt learning [15], we develop a lightweight single-layer architecture to generate image-specific tokens as initial pseudo-prompt representations, which are then embedded into CLIP’s shared feature space alongside visual features. We optimize this network through dual modal contrastive learning strategies: (1) aligning generated pseudo-prompts with ground-truth prompts via contrastive learning and mean squared error loss for labeled data, and (2) employing self-supervised cross-prediction on the labeled dataset to strengthen visual–textual correlations. In the second stage, we leverage the trained generator to produce textual descriptions for unlabeled samples in online sessions. These descriptions are fused with visual representations through an adaptive fusion strategy, and the unified features are fed into a self-distillation framework [16] to generate text-enhanced pseudo-labels. This approach improves classification performance while mitigating catastrophic forgetting in unsupervised continual learning.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- 1.

- We attribute catastrophic forgetting in C-GCD to the absence of supervision. Specifically, we identify two critical issues: First, novel samples exhibit weak representational capacity, making them susceptible to semantic drift in subsequent sessions, leading to task-level overfitting. Second, semantic clusters spontaneously formed by novel samples are influenced by individual sample representations, resulting in small inter-class distances and large intra-class variance.

- 2.

- To address insufficient supervision, we propose DMCL, which incorporates a prompt generation network to synthesize textual descriptions for unlabeled samples. By fusing textual and visual modalities, we enrich sample representations and enhance discriminability, effectively mitigating the aforementioned issues. Furthermore, we introduce dual-modal contrastive learning to strengthen vision-text alignment and a multimodal self-distillation framework to generate high-quality pseudo-labels.

- 3.

- Extensive experiments on CIFAR-100, Tiny-ImageNet, ImageNet-100, and CUB-200 demonstrate the effectiveness of our method across both generic and fine-grained datasets. Comprehensive ablation studies and qualitative analyses confirm that our approach successfully addresses task-level overfitting and decision boundary degradation, achieving superior plasticity–stability trade-offs in continual learning scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Novel Category Discovery

Novel category discovery (NCD) addresses open-world classification challenges. Early NCD methods adopted two-stage approaches derived from transfer learning principles. Deep Transfer Clustering (DTC) [17] exemplifies this paradigm by first training embeddings on labeled data, then applying them to unlabeled instances. Subsequently, contrastive learning [18,19] enabled one-stage joint training on both labeled and unlabeled data. RankStats [20] employs self-supervised learning with ranking statistics for similarity computation, while UNO [4] introduces parametric classifiers through pseudo-labeling to enable cross-entropy optimization. These advances established the foundation for NCD and GCD research.

2.2. Generalized Category Discovery

Generalized Category Discovery (GCD) extends NCD to scenarios where unlabeled data contain both known and novel classes, also termed Open-World Semi-Supervised Learning (OW-SSL) [21,22,23]. Existing GCD methods typically extract visual features using pretrained vision transformers, then fine-tune through supervised learning on labeled samples and self-supervised contrastive learning on all data. Like NCD, GCD assumes prior knowledge of novel class numbers. Classification approaches divide into two paradigms: non-parametric and parametric methods. Non-parametric Methods utilize clustering-based classifiers, typically K-means [24], for novel category discovery. These methods mitigate overfitting to known classes while providing scalability for varying class numbers. The seminal GCD work constrains labeled clusters, then applies semi-supervised K-means on unlabeled data. Subsequent works exploit semantic structures through contrastive learning and prompt mechanisms. Some approaches leverage non-parametric properties to discover classes without prior knowledge of class numbers. Parametric Methods employ learnable classification heads for predictions. SimGCD [16] demonstrates that parametric models can outperform non-parametric counterparts when pseudo-label quality is sufficient, proposing a self-distillation framework that improves pseudo-label reliability. Recent works address biases in pseudo-label generation [25] and class imbalance [26], achieving state-of-the-art performance.

2.3. Continual Category Discovery

Investigating N/GCD in continual settings represents a natural progression in open-world learning. The terms “Continual” and “Incremental” are used interchangeably, both referring to class incremental learning.

NCDwF [11] investigates NCD in continual settings where models learn from labeled data then discover novel classes from unlabeled data. FRoST introduces replay-based storage of feature prototypes, while MSc-iNCD [27] leverages pretrained self-supervised models. Grow & Merge [12] extends to continual GCD, where models access labeled data initially and sequential unlabeled data subsequently. It employs growing phases for novel class detection and merging phases for knowledge distillation. IGCD [28] studies continual GCD on iNat2021 [29], processing partially labeled images at each stage.

Recent works explore alternative strategies. CLIP-CNCD [30] leverages CLIP’s zero-shot capabilities, decoupling old knowledge preservation from novel discovery through CLIP-generated pseudo-labels with CutMix [31] augmentation. PromptCCD [6] introduces Gaussian Mixture Prompting [32] with dynamic prompt pools for adaptive selection and on-the-fly class number estimation. TSPT [33] proposes rehearsal-free Two-Step Prompt Tuning with clustering-guided consistency learning and prompt pool selection. Happy [7] addresses class imbalance and pseudo-label biases through hardness-aware prototype sampling and soft entropy regularization.

Current C-GCD research adopts different configurations for novel class emergence. This work follows [7]: labeled data at the initial stage, progressive novel class discovery from unlabeled data in subsequent stages.

3. Method

3.1. Problem Definition

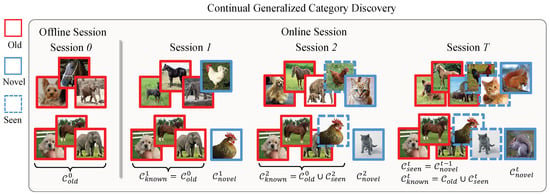

Figure 2 illustrates the C-GCD task pipeline. Formally, the model operates on labeled data and unlabeled data , where t denotes the session index. In our setting, labeled data is exclusively available at the initial stage (Session 0, ), also referred to as the offline session. We denote the label space of labeled data as and the complete label space including novel classes as , where . The model acquires foundational knowledge from containing old classes . Subsequently, the framework transitions into continual unsupervised discovery from Session 1 to T, where each session t presents unlabeled data containing both previously encountered and novel categories. Throughout this process, known classes encompass all previously observed categories, including the old classes and novel classes discovered in prior sessions . Novel classes represent categories first encountered at session t. This creates a progressive knowledge accumulation pattern where , meaning today’s discoveries become tomorrow’s foundation. The model’s performance is evaluated on test set , encompassing all categories observed through session t.

Figure 2.

Pipeline of Continual Generalized Category Discovery. The model first learns old classes in Session 0, then discovers novel classes while retaining known classes across sequential sessions. Novel classes discovered in session t become seen classes in session .

3.2. Baseline Framework

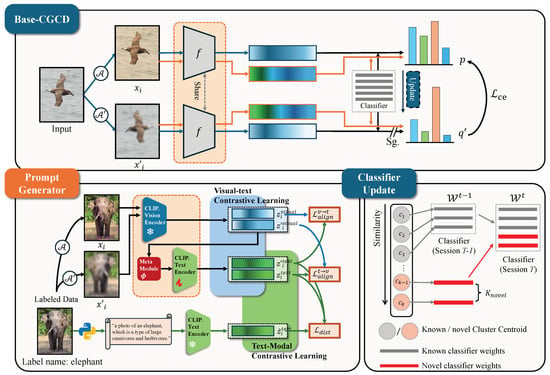

A straightforward solution is to adapt off-the-shelf GCD methods to continual settings. We develop a baseline framework, termed Base-CGCD. This baseline evaluates existing approaches under continual learning and reveals inherent challenges in C-GCD. As illustrated in Figure 3, Base-CGCD adopts a self-distillation architecture that performs GCD at each session. Upon discovering novel classes, we initialize new prototype heads using K-means clustering on learned features, enabling incremental learning through iterative head expansion.

Figure 3.

Overview of the DMCL framework. Top: Base-CGCD employs self-distillation for pseudo-label generation, where two augmented views are fed through a shared encoder to produce predictions and sharpened targets. Bottom-left: Prompt Generator trains a meta-module to generate pseudo-textual descriptions for unlabeled data via CLIP text encoder. And then, dual-modal contrastive learning aligns visual and textual modalities through bidirectional contrastive objectives and distribution matching loss. Bottom-right: Classifier Update shows progressive expansion from session 1 to T, where novel prototypes (red) are initialized alongside existing known prototypes (gray).

3.2.1. Representation Learning

Following [16], we employ both supervised and self-supervised learning in the projection space to enhance the model’s generalization capability:

where the feature is normalized, and denote the backbone and the projection head, respectively, and , are the temperature parameters. For clarity, the session index t is omitted in subsequent equations. In supervised contrastive learning, indexes all samples in the same batch sharing the same label as . The overall representation learning loss is balanced with

3.2.2. Parametric Classification

We adopt the parametric classification paradigm for category discovery. Specifically, we initialize classifier weights for all classes at session t, where . During training, for each augmented view , we compute the prediction distribution via softmax over cosine similarities between hidden feature and prototypes , scaled by temperature :

The soft pseudo-label is generated from another augmented view using a sharper temperature . For the offline session, we apply standard supervised cross-entropy loss:

where denotes the one-hot label of . For online sessions, which are entirely unsupervised, we replace ground-truth labels with soft pseudo-labels to construct the cross-entropy loss.

3.2.3. Incremental Update Strategy

We achieve continual discovery through iterative expansion of prototype classification heads. Specifically, as illustrated in the “Classifier Update” module of Figure 3, we perform K-means clustering on to obtain K -normalized cluster centroids . Among these, the centroids with the lowest maximum cosine similarity to existing old class heads are selected to initialize new prototype heads:

To mitigate catastrophic forgetting, we apply feature-level knowledge distillation [34] between the current model and the previous session model :

The overall optimization objectives for offline and online sessions are formulated as follows:

3.2.4. Limitations of Baseline

Experiments demonstrate (Section 4) that naive adaptations fail to address the complex C-GCD problem. Although self-distillation excels in static settings, it struggles in online sessions due to insufficient supervision. Without supervisory signals, the model exhibits bias toward dominant classes with higher sample frequencies during training. Consequently, known class samples are frequently misclassified as novel classes during testing. Furthermore, unsupervised clustering yields inaccurate prototypes characterized by reduced inter-class distances and increased intra-class variance. These issues lead to severe catastrophic forgetting, with static GCD methods sometimes failing to learn effectively in incremental scenarios.

3.3. Learning Instance-Specific Prompts for C-GCD

To overcome Base-CGCD’s limitations, we leverage the inherent discriminative power of textual modality to enhance visual representations. We adopt conditional prompt learning to address the challenge of inaccessible category information in unlabeled environments, and propose dual-modal contrastive learning across textual and visual–textual modality spaces.

3.3.1. Text-Modal Contrastive Learning

We first develop a pre-processing pipeline to encode image–label pairs within each mini-batch. Category information is structured into descriptions following the template “a photo of [class name], which is a type of [coarse class name]”, then encoded into feature vectors via CLIP’s text encoder. These serve as ground-truth supervision for training our prompt generation network.

We introduce a meta-module to map visual features to textual representations. Following meta-learning principles, learns to adaptively generate prompts from visual features. Specifically, given two augmented views and from , we extract visual representations through CLIP’s frozen vision encoder, then generate . To align generated prompts with the ground truth, we employ textual-modal contrastive learning:

where indicates labeled data space and mean squared error loss:

We combine both losses as to optimize and fine-tune the last layer of the text encoder , ensuring approximates the ground-truth prompts .

3.3.2. Visual–Text Cross-Modal Contrastive Learning

Subsequently, is processed by to synthesize corresponding tokens, which are then encoded by the trainable text encoder to generate textual representations . To ensure alignment between textual features and their corresponding images, we establish positive pairs by matching visual features from the first augmented view with pseudo-textual features from the second view, and vice versa. This bidirectional pairing strategy strengthens cross-modal alignment and enhances generalization capacity. The cross-modal contrastive losses are formulated as follows:

The overall cross-modal alignment loss is . Finally, we replace the single-modality encoder in Base-CGCD with our trained multimodal encoder to extract both textual and visual features. We perform cross-attention fusion on these modalities to dynamically balance their contributions:

The enhanced features are then fed into the self-distillation framework to generate high-quality pseudo-labels for classification.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experiments Detail

Datasets

We evaluate DMCL on three generic datasets: CIFAR-100 [35], Tiny-ImageNet [36], and ImageNet-100 [37] as well as the fine-grained dataset CUB-200 [38]. Each dataset is partitioned into an offline session and multiple online sessions (3 sessions by default). In the offline session, 70% of classes serve as the initial labeled data for supervised learning. In subsequent online sessions, the remaining classes are uniformly distributed as novel classes across sessions, with each session containing unlabeled data from both newly introduced novel classes and all previously learned classes. Table 1 provides detailed dataset statistics, where “Img/Novel” and “Img/Known” denote the number of samples per novel class and known class at each session, respectively.

Table 1.

Dataset configurations for Continual Category Discovery.

4.2. Evaluation Protocol

At each session, after training, the model is evaluated on a disjoint test set containing samples from both and . Following standard practice, we compute clustering accuracy (ACC) using the Hungarian algorithm [39] to find the optimal assignment between predicted cluster labels and ground-truth labels :

where and p denotes the optimal permutation. We report accuracy across three subsets: “All” (all classes ), “Known” (previously learned classes ), and “Novel” (newly discovered classes ).

Implementation

In all experiments, we employ ViT-B/16 pretrained with DINO v1 [13] as the initial backbone and fine-tune only the last transformer block. Our training proceeds in two stages:

Stage 1: Prompt Generation Network Training. During the offline session (Session 0), we train the prompt generation network on all labeled data for 100 epochs. In this stage, we freeze the CLIP vision encoder and fine-tune only the last layer of the CLIP text encoder. This allows the meta-module to learn effective mappings from visual features to textual representations while preserving the pretrained vision-language alignment.

Stage 2: Continual Discovery with Dual-Modal Learning. After training, we replace the DINO backbone in Base-CGCD with the trained prompt generation network and CLIP encoders. At each online session (Sessions 1 to T), we train on the unlabeled data containing both known and novel classes for 30 epochs with a batch size of 128 and a learning rate of 0.1. During this stage, we freeze the text encoder and fine-tune the vision encoder to adapt visual representations while maintaining stable textual features.

The Base-CGCD baseline follows the hyperparameter settings from [7,16]. All experiments are conducted on NVIDIA RTX A800 GPUs.

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

We compare DMCL against Base-CGCD and recent state-of-the-art C-GCD methods including GCD [3], SimGCD [16], GM [12], MetaGCD [40], PromptCCD [6], and Happy [7]. Table 2 presents comprehensive results across four datasets with three online sessions. DMCL achieves competitive or superior performance across all baselines in most scenarios.

Table 2.

Results on CIFAR-100(C100), ImageNet-100(IN100), Tiny-ImageNet(TinyIN), CUB200(CUB) with 3 online sessions. Bold indicates the best performance.

Novel Class Discovery. DMCL demonstrates strong plasticity in discovering novel classes. On CIFAR-100, DMCL achieves 67.00% novel class accuracy at Session 3, substantially outperforming Happy at 63.80% and PromptCCD at 55.12%. On ImageNet-100, DMCL attains 74.32% at Session 3, surpassing Happy at 73.24% and significantly ahead of other methods. Notably, on CUB, DMCL achieves remarkable improvements, reaching 77.82%, 79.34%, and 48.00% novel class accuracy across three sessions, compared to Happy’s results of 65.03%, 64.22%, and 40.16%. These results demonstrate that dual-modal contrastive learning effectively enriches representations and enhances discriminability for novel category discovery.

Knowledge Retention. For previously learned classes, DMCL maintains competitive accuracy while balancing plasticity. On CIFAR-100, DMCL achieves 87.08% and 78.79% known class accuracy at Sessions 1 and 2, outperforming most baselines. On ImageNet-100, DMCL attains 86.14% and 82.72% at Sessions 1 and 2, comparable to Happy’s 84.52% and 82.61%. This validates that our approach effectively mitigates catastrophic forgetting through adaptive fusion of visual and textual modalities.

Fine-Grained Recognition. On the challenging fine-grained CUB dataset, DMCL substantially outperforms all methods across sessions. At Sessions 1 and 2, DMCL achieves overall accuracies of 82.93% and 77.98%, surpassing Happy’s 82.03% and 75.24% and significantly ahead of other methods. This highlights the benefit of incorporating textual semantics for fine-grained visual discrimination, where subtle inter-class differences require richer multimodal representations.

4.3.2. Forgetting and Discovery Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s discovery capability and resistance to catastrophic forgetting, we analyze two key metrics: the maximum forgetting rate and the final discovery rate . The metric measures the capability to maintain performance on old categories, where lower values indicate better retention. The metric measures the ability to discover novel categories, where higher values indicate better discovery performance.

Both metrics are accuracy-based. The clustering accuracy on old categories and novel categories at session t can be computed as follows:

where and denote the number of old and novel category samples from , and and denote the ground-truth labels of old and novel samples, respectively. The forgetting and discovery metrics are then defined as and .

Table 3 presents the forgetting and discovery analysis on CUB. Compared to the state-of-the-art method Happy, DMCL demonstrates substantial improvements on both metrics. Specifically, DMCL reduces the forgetting rate from 4.18% to 3.79%, achieving the lowest forgetting among all methods. Meanwhile, DMCL significantly improves the discovery rate from 53.79% to 71.05%, demonstrating enhanced plasticity for novel class learning. In terms of overall performance, DMCL attains an average accuracy of 77.90%, surpassing Happy at 77.88% and PromptCCD at 55.45%.

Table 3.

Forgetting and Discovery Analysis on CUB. (↑ indicates that the higher the metric, the better, and ↓ indicates that the lower the metric, the better). Bold indicates the best performance.

These results validate that dual-modal contrastive learning with adaptive fusion effectively addresses the plasticity–stability dilemma in continual category discovery. The superior performance on the fine-grained CUB dataset particularly highlights the benefit of incorporating textual semantics, where subtle inter-class differences require richer multimodal representations to maintain discriminative decision boundaries across sessions.

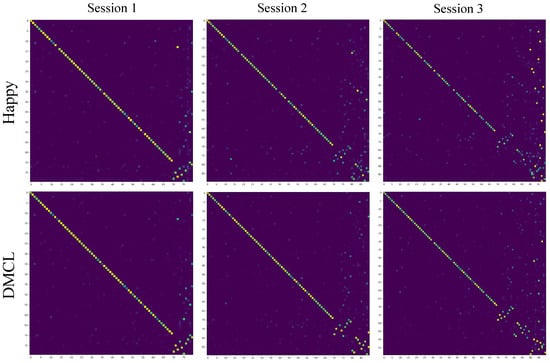

4.3.3. Visualization

We provide qualitative analysis to intuitively compare DMCL with the baseline framework. Figure 4 presents confusion matrices on CIFAR-100 across three online sessions. DMCL produces clearer diagonal patterns compared to Happy, indicating improved classification accuracy and reduced confusion between classes. Notably, the off-diagonal elements in DMCL are significantly sparser, demonstrating that the model effectively mitigates task-level overfitting. Specifically, DMCL exhibits substantially fewer known class samples misclassified as the novel classes introduced in the current session, validating the effectiveness of dual-modal learning in maintaining stable decision boundaries.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrices on CIFAR-100. DMCL produces clearer diagonal patterns compared to Base-CGCD, indicating improved classification accuracy and reduced confusion. Moreover, DMCL effectively mitigates task-level overfitting, with significantly fewer known class samples misclassified as the 10 novel classes in the current session.

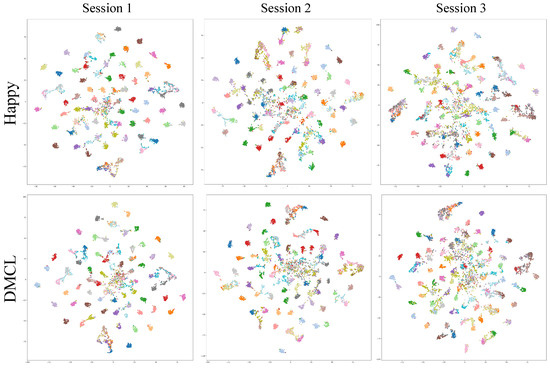

Figure 5 visualizes feature distributions using t-SNE across three sessions. Compared to Happy, DMCL achieves better class separation with reduced overlap among semantic clusters. In Session 1, DMCL shows more compact and well-separated clusters for both known and novel classes. As sessions progress, while both methods experience increased inter-class overlap due to the accumulation of classes, DMCL consistently maintains clearer cluster boundaries. This demonstrates that incorporating textual semantics through dual-modal contrastive learning enriches feature representations and enhances discriminability, thereby alleviating semantic drift across continual learning sessions.

Figure 5.

t-SNE visualization of feature distributions. DMCL (bottom) achieves better class separation with reduced overlap compared to Base-CGCD (top).

4.4. Ablation Study

We conduct comprehensive ablation studies to evaluate the effectiveness of each component in DMCL. Table 4 presents results on CIFAR-100 with different configurations of dual-modal contrastive learning and fusion strategies.

Table 4.

Ablation Study on DMCL Components and Multimodal Fusion Strategies. Bold indicates the best performance.

Effectiveness of Dual-Modal Contrastive Learning. Comparing the baseline without dual-modal contrastive learning (row 1) to the full model with adaptive fusion (row 2), we observe substantial improvements: 29.79% gain in overall accuracy, 4.92% in known classes, and 32.80% in novel classes. This validates that incorporating textual semantics significantly enhances feature discriminability and mitigates catastrophic forgetting.

Fusion Strategy Analysis. We compare four fusion strategies: adaptive, average, concatenation, and cross-attention. Cross-attention fusion achieves the best overall performance at 76.36%, demonstrating the superiority of instance-specific dynamic weighting over fixed parameter approaches. Notably, cross-attention excels particularly on known classes (77.89% vs. 77.18% for adaptive), validating our theoretical analysis that sample-aware fusion better mitigates catastrophic forgetting. The mechanism allows old class samples (prone to forgetting) to emphasize stable textual anchors, while novel class samples leverage adaptive visual features for discovery.

Adaptive fusion achieves competitive performance at 75.22%. Examining the learned fusion coefficient reveals that visual and textual modalities contribute nearly equally to enhanced representations. This near-equal weighting provides a strong baseline but lacks the flexibility to handle samples with different plasticity–stability requirements.

Average fusion performs comparably at 74.89%, only 0.33% lower than adaptive fusion. This validates our finding that is optimal—when the learned parameter approaches 0.5, average fusion becomes effectively equivalent, offering a simpler alternative without learnable parameters.

Concatenation-based fusion achieves only 70.22% overall accuracy, substantially underperforming other strategies. This degradation stems from increased dimensionality and potential misalignment between visual and textual feature spaces, which complicates discriminative decision boundary learning. The particularly poor novel class performance (52.24%) suggests concatenation fails to effectively integrate complementary modality information.

Prompt Setting Analysis. Table 5 presents ablation experiments validating our design choices on CIFAR-100. The most critical component is dual-modal contrastive learning. Removing it (visual-only) causes performance to drop from 76.36% to 51.67%, a substantial 24.69% degradation. Novel class accuracy is particularly affected (27.43% drop), confirming that textual semantics are essential for distinguishing newly emerged categories.

Table 5.

Ablation Study on CIFAR100 with prompt configure.

Conditional prompt generation outperforms fixed learnable prompts by 12.58% (76.36% vs. 63.78%). Instance-specific prompts capture fine-grained variations within categories, while fixed prompts apply uniformly and struggle to generalize, especially for novel classes where the gap reaches 22.69%. Our pseudo-prompt approach achieves 76.36%, reasonably close to the oracle using ground-truth text (82.42%). The 6.06% gap demonstrates that conditional generation effectively synthesizes discriminative descriptions without requiring manual annotations.

These results confirm that textual information and instance-specific generation are both essential for effective continual category discovery.

4.5. Novel Class Number Estimation

Previous experiments assume the number of novel classes is known a priori for fair comparison. However, automatic class number estimation is crucial for practical applications. Table 6 presents results under the class-agnostic setting on CIFAR-100, where we employ a hybrid estimation strategy combining Silhouette Score and Elbow Method to automatically determine novel class numbers. PromptCCD adopts a non-parametric classifier, which has inherent advantages in class-agnostic scenarios due to flexible output dimensionality. In contrast, Happy and our method employ parametric classifiers, requiring additional estimation mechanisms before training.

Table 6.

Performancewithout knowing the number of novel classes. DMCL achieves competitive results in the class-agnostic setting.

Despite this structural disadvantage, our method achieves the best overall accuracy at 67.20%, surpassing PromptCCD at 59.12%, Happy at 66.80%, and GM at 53.33%. For individual metrics, PromptCCD leads on both known classes at 77.62% and novel classes at 53.70%. Our method ranks second on both categories: 72.00% for known classes and 51.26% for novel classes, outperforming Happy at 70.56% and 48.84%, respectively.

These results validate that our dual-modal learning framework maintains robustness when class numbers are estimated rather than known, highlighting practical applicability in real-world continual learning scenarios.

4.6. Complexity Analysis

Table 7 presents complexity and efficiency metrics on CIFAR-100. Our model requires 92.0 M parameters, 16.87 GFLOPs per image, and 3.77 GB peak memory. Compared to visual-only baselines, the dual-modal components add approximately 6.2 M parameters (7.2% increase) and 0.67 GFLOPs (4.1% increase). This modest overhead yields substantial performance gains: 76.36% accuracy versus 65.89% for the baseline (10.47% improvement).

Table 7.

Model Complexity and Efficiency Analysis on CIFAR-100.

Inference efficiency remains strong at 1.01 ms per sample, achieving 986.94 FPS throughput and 16.65 TFLOPS. Training takes approximately 57 s per epoch, with novel class clustering requiring only 2–3 s per session. The pseudo-prompt generation adds negligible latency (0.05 ms per sample).

These results demonstrate a favorable trade-off: less than 5% computational overhead achieves over 10% accuracy improvement, validating our approach’s efficiency and practical applicability.

5. Discussion

5.1. Why Dual-Modal Contrastive Learning Works?

Existing works primarily rely on single visual modality for continual category discovery, overlooking the natural advantage of textual information in distinguishing novel classes under unlabeled settings. CLIP’s ability to map textual and visual features into a unified latent space provides the foundation for our dual-modal contrastive learning. Specifically, we introduce a meta-network to enable CLIP to handle unlabeled data, leveraging its inherent text-vision alignment capability to learn image-to-text mappings for generating descriptions of unknown images.

5.2. How Does Textual Features Mitigate Catastrophic Forgetting?

Textual features, in the form of pseudo-descriptions generated from corresponding images, provide semantic information that compensates for the lack of supervised signals in unsupervised continual learning. By incorporating these textual semantics, samples acquire enhanced discriminability, which alleviates semantic drift and consequently mitigates task-level overfitting.

Furthermore, as each sample obtains richer discriminative information through dual-modal representations, semantic clusters form more distinct and well-defined prototypes. During prototype initialization at each session, these high-quality prototypes derived from better-separated clusters lead to improved initial decision boundaries. This creates a virtuous cycle: better prototypes yield more accurate pseudo-labels, which in turn facilitate more reliable representation learning and prototype updates in subsequent sessions. Consequently, the model maintains stable decision boundaries for previously learned classes while adapting to novel categories, effectively balancing plasticity and stability.

5.3. How Textual Information Mitigates the Plasticity–Stability Dilemma?

Textual semantics serve dual roles: semantic anchors for stability and discriminative features for plasticity. Our adaptive fusion balances these uniformly, but different samples have contradictory needs. Old class samples require stability through higher text weight, while novel samples need plasticity through higher visual weight.

Cross-attention addresses this through instance-specific weighting. The bidirectional querying mechanism automatically adjusts modality emphasis: old samples attend more to stable text, novel samples to adaptive vision. This sample-aware balancing reduces forgetting while improving accuracy on both known and novel classes.

Fixed parameter fusion cannot simultaneously optimize for contradictory requirements. Cross-attention’s dynamic per-sample adjustment achieves superior plasticity–stability trade-offs, explaining its performance gains in our experiments.

6. Conclusions

This paper addresses Continual Generalized Category Discovery (C-GCD), an emerging challenge in open-world learning where models must incrementally discover novel classes from unlabeled data while preserving recognition of previously learned classes without accessing historical samples. We identify that the absence of supervisory signals in online sessions leads to two critical issues: semantic drift causing task-level overfitting, and degraded decision boundaries resulting from poor cluster quality.

To address these challenges, we propose DMCL, a dual-modal contrastive learning framework that leverages CLIP’s multimodal potential through a two-stage training paradigm. In the first stage, we introduce a prompt generation network with conditional prompt learning to synthesize textual descriptions for unlabeled samples. In the second stage, we enhance Base-CGCD with dual-modal contrastive learning and adaptive fusion, generating high-quality pseudo-labels through multimodal self-distillation. By incorporating textual semantics, our approach enriches sample representations and enhances discriminability, effectively mitigating catastrophic forgetting while improving novel class discovery.

Extensive experiments on CIFAR-100, Tiny-ImageNet, ImageNet-100, and CUB-200 demonstrate that DMCL achieves competitive or superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods. Particularly on fine-grained datasets, our method shows substantial improvements, validating the effectiveness of multimodal learning for continual category discovery. Comprehensive ablation studies and qualitative analyses confirm that dual-modal contrastive learning successfully addresses task-level overfitting and decision boundary degradation, achieving superior plasticity–stability trade-offs.

7. Future Work

While DMCL demonstrates the effectiveness of dual-modal learning for C-GCD, several promising directions merit further investigation. First, our prompt generation currently relies on fixed templates. Future work could explore learnable prompt structures that adapt to different visual domains or leverage large language models to generate richer semantic descriptions. Second, extending our global adaptive fusion to hierarchical or attention-based mechanisms could enable fine-grained integration where modality contributions vary spatially or semantically. Third, developing robust methods for estimating novel class numbers in dual-modal settings would enhance practical applicability, potentially through multimodal clustering consistency or semantic gap analysis in the embedding space. Beyond methodological improvements, extending C-GCD to more challenging scenarios such as object detection, semantic segmentation, or domain adaptation would demonstrate broader applicability. Additionally, theoretical analysis of how textual semantics contribute to plasticity–stability trade-offs could provide principled guidance for fusion strategy design.

We hope this work provides valuable insights and inspires future research in multimodal continual learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.J.; methodology, W.J.; formal analysis, C.Y.; resources, K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.J.; writing—review and editing, N.L.; visualization, H.H.; supervision, N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are sourced from a publicly available dataset. The dataset can be accessed at the following URL: ImageNet: Available online: https://image-net.org/download.php (accessed on 16 January 2026); CIFAR-100: Available online: http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 16 January 2026); CUB-200-2011: Available online: https://www.vision.caltech.edu/datasets/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhu, F.; Ma, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.L. Open-world machine learning: A review and new outlooks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.01759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Generalized out-of-distribution detection: A survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 5635–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaze, S.; Han, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Generalized category discovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 7492–7501. [Google Scholar]

- Fini, E.; Sangineto, E.; Lathuilière, S.; Zhong, Z.; Nabi, M.; Ricci, E. A unified objective for novel class discovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9284–9292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.W.; Wang, Q.W.; Qi, Z.H.; Ye, H.J.; Zhan, D.C.; Liu, Z. Class-incremental learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 9851–9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cendra, F.J.; Zhao, B.; Han, K. Promptccd: Learning gaussian mixture prompt pool for continual category discovery. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 188–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Zhu, F.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, C.L. Happy: A debiased learning framework for continual generalized category discovery. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 50850–50875. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Gao, F.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Hussain, A.; Zhou, H. Novel category discovery without forgetting for automatic target recognition. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4408–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, C.Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, R.; Ren, X.; Su, G.; Perot, V.; Dy, J.; Pfister, T. Learning to prompt for continual learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, C.; Yin, F.; Liu, C.L. Prototype augmentation and self-supervision for incremental learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 5871–5880. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, K.; Paul, S.; Aggarwal, G.; Biswas, S.; Rai, P.; Han, K.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Novel class discovery without forgetting. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 570–586. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Feng, Y.; Wu, Z.F.; Zhao, X.; Wan, H.; Tang, M.; Jin, R.; Gao, Y. Grow and merge: A unified framework for continuous categories discovery. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 27455–27468. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 9650–9660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Loy, C.C.; Liu, Z. Learning to Prompt for Vision-Language Models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. (IJCV) 2022, 130, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Loy, C.C.; Liu, Z. Conditional Prompt Learning for Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X.; Zhao, B.; Qi, X. Parametric classification for generalized category discovery: A baseline study. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 16590–16600. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Learning to discover novel visual categories via deep transfer clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Repulic of Korea, 27 October–12 November 2019; pp. 8401–8409. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 9729–9738. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Misra, I.; Mairal, J.; Goyal, P.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Unsupervised learning of visual features by contrasting cluster assignments. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 9912–9924. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Rebuffi, S.A.; Ehrhardt, S.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Autonovel: Automatically discovering and learning novel visual categories. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 6767–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cai, X.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, W. Dual-Space Contrastive Learning for Open-World Semi-Supervised Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 14735–14748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, R.; Feng, L.; Tang, K.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, H. Targeted representation alignment for open-world semi-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 23072–23082. [Google Scholar]

- Rizve, M.N.; Kardan, N.; Khan, S.; Shahbaz Khan, F.; Shah, M. Openldn: Learning to discover novel classes for open-world semi-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 382–401. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, J. Multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statisticsand Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1965; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 1, pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Otholt, J.; Dai, B.; Hu, D.; Meinel, C.; Yang, H. Supervised knowledge may hurt novel class discovery performance. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.03648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Lian, L.; Yu, S.X. Debiased learning from naturally imbalanced pseudo-labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 14647–14657. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Roy, S.; Zhong, Z.; Sebe, N.; Ricci, E. Large-scale pre-trained models are surprisingly strong in incremental novel class discovery. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Kolkata, India, 1–5 December 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Mac Aodha, O. Incremental generalized category discovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 19137–19147. [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn, G.; Cole, E.; Beery, S.; Wilber, K.; Belongie, S.; Mac Aodha, O. Benchmarking representation learning for natural world image collections. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 12884–12893. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q.; Yang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wiltos, K.; Woźniak, M.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Y. CLIP-guided continual novel class discovery. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 112920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Han, D.; Oh, S.J.; Chun, S.; Choe, J.; Yoo, Y. Cutmix: Regularization strategy to train strong classifiers with localizable features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Repulic of Korea, 27 October–12 November 2019; pp. 6023–6032. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Wen, X.; Han, K. Learning semi-supervised gaussian mixture models for generalized category discovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 16623–16633. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Du, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D. TSPT: Two-Step Prompt Tuning for class-incremental novel class discovery. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 319, 113603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Pan, X.; Loy, C.C.; Wang, Z.; Lin, D. Learning a unified classifier incrementally via rebalancing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 831–839. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Y.; Yang, X. Tiny imagenet visual recognition challenge. CS 231N 2015, 7, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, C.; Branson, S.; Welinder, P.; Perona, P.; Belongie, S. The Caltech-Ucsd Birds-200-2011 Dataset. 2011. Available online: https://authors.library.caltech.edu/records/cvm3y-5hh21 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Kuhn, H.W. The Hungarian method for the assignment problem. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 1955, 2, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, S. MetaGCD: Learning to Continually Learn in Generalized Category Discovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.