Abstract

Improving responsiveness and efficiency in production systems requires an understanding of how manufacturing flexibility and inventory management interact under conditions of uncertainty. This study examines the combined effect of four types of flexibility, machine, labor, routing, and volume, together with the use of buffers, on the total flow time of production batches. A total of 84 experimental configurations were simulated, of which 35 were feasible and statistically valid, using a discrete-event simulation model developed in Arena and validated with industrial data. The results show that combining high machine and labor flexibility reduces total flow time from 5450 to 3050 min (a 44% decrease), whereas routing and volume flexibility exhibit minor effects. Moreover, the inclusion of buffers further improves performance, reducing times by approximately 1000 min in low-flexibility configurations. These findings provide robust quantitative evidence to guide the design of adaptive production systems by jointly evaluating the flexibility and inventory management dimensions that are typically studied in isolation.

Keywords:

manufacturing flexibility; buffer allocation optimization; inventory modeling; discrete-event simulation; operations research; statistical analysis MSC:

90B35

1. Introduction

Flexible manufacturing enables production systems to efficiently adapt to internal and external changes, including fluctuations in demand, product variety, and operating conditions [1]. Flexible manufacturing systems (FMS) can produce different types of products simultaneously through programmed control at multiple automated and interconnected workstations [2,3].

While there is broad agreement on the importance of flexibility, its practical implementation and quantification remain challenging [4,5,6]. Among the various dimensions of flexibility described in the literature, this study focuses on those most directly related to system operations and amenable to parameterization: machine, labor, volume, and route flexibility [7]. In this context, machine flexibility and the other dimensions are interdependent and contingent on the available capacity at each level. Specifically, a minimum threshold of machine flexibility is necessary to enable increased flexibility in routing and production volume. Furthermore, labor flexibility must be aligned with these levels to ensure efficient adaptation to variations in production processes. Any imbalance among these elements can create inefficiencies or bottlenecks, thereby affecting the overall performance of the manufacturing system.

In particular, we examine how these types of flexibility affect flow time, a critical performance metric in dynamic and uncertain environments. The interplay between flexibility and uncertainty management has gained increasing attention, as unpredictable events—such as machine breakdowns or job arrival variability—significantly affect system performance [8,9]. Addressing this challenge requires quantitative approaches capable of modeling and anticipating such fluctuations [10].

In this document, two operational concepts are essential for interpreting the effects of flexibility and buffer management. The first is flow time, understood as the total time a lot spends on the system from its arrival to its completion, including both processing and waiting periods. This indicator directly reflects the system’s efficiency and its level of congestion. The second concept is responsiveness, which refers to the system’s ability to react in a timely manner to changes in demand, operational variations, or internal disruptions. In this research, this capability is assessed indirectly through flow time, under the premise that, if the system requires less time to process the lots, it is better prepared to respond to any change.

This study is set in the context of job shop FMS (JS-FMS), characterized by variable workflows and shared resources [11,12]. Scheduling in such systems involves two key decisions: resource allocation and job sequencing. Traditional static scheduling rules often underperform in these dynamic settings, highlighting the need for prediction and optimization techniques [13,14].

Although recent studies, such as those by [15,16], have begun to combine flexibility and buffers, they focus on partial configurations of flexibility (e.g., machine + buffer, or machine + route + buffer) and operate under limited uncertainty conditions. In contrast, the present study simultaneously evaluates four types of operational flexibility (machine, labor, route, and volume) together with the explicit allocation of buffers, within an experimental design that incorporates multiple sources of internal and external uncertainty. This broader integration enables the identification of nonlinear interactions and emergent effects that have not been characterized in prior studies, thereby providing a novel and more generalizable contribution to the analysis of the dynamic behavior of flexible manufacturing systems.

This research proposes a quantitative approach that integrates prediction and dynamic sequencing, while also considering buffer management as a strategic mechanism to absorb uncertainty. The main objective is to analyze how different configurations of flexibility impact flow time in a JS-FMS, contributing to more informed and resilient decision-making in complex production environments.

Related Literature

Research in FMS has extensively explored how flexibility and buffering strategies can be employed to address both internal and external uncertainties. This body of literature can be grouped into three main thematic areas: (i) conceptual frameworks on flexibility and uncertainty, (ii) empirical and simulation-based studies on flexibility and buffering, and (iii) algorithmic and optimization approaches for dynamic environments.

(i) Conceptual frameworks on flexibility and uncertainty: Pioneering studies by [17,18] laid the foundation for understanding how organizations combine flexibility and buffering to manage uncertainty. Pagell et al. [18], through the analysis of three case studies, highlighted that investments in infrastructure and workforce development significantly enhance organizational flexibility. However, while buffering strategies can absorb variability, they may also lead to increased long-term costs and introduce additional uncertainty. These studies underscore the need for prescriptive models that guide the combined application of flexibility and buffering across diverse operational contexts.

(ii) Empirical and simulation studies: A second research stream has focused on empirically validating the operational impact of different types of flexibility. Palominos et al. [19] assessed the flexibility of labor and machines in the face of disturbances, using a factorial design and simulations with Arena 7.01 software. Their results demonstrated that machine flexibility is key in high-demand scenarios, while labor flexibility becomes more critical in cases of system failure. Meanwhile, Seebacher and Winkler [20] proposed a bidimensional model that evaluates the trade-off between performance and efficiency in discrete manufacturing systems.

More recently, Mwangola et al. [15] analyzed how companies dynamically adjust inventory and volume flexibility based on uncertainty levels. High-performance firms strategically adjust both tools; in uncertain environments, they maximize their use to improve financial and operational performance, while in stable contexts, they reduce them to avoid costs. In contrast, low-performance firms often misuse these tools, with high levels in stable environments or exclusive reliance on flexibility in uncertain environments, thus limiting their competitiveness.

(iii) Optimization models and algorithmic developments: The third line of research consists of technical contributions aimed at optimizing operations in flexible systems. Waseem and Chang [16] developed a decision-making algorithm (Nash-MADDPG) that incorporates buffering strategies to manage uncertainty in multi-product FMS. Their reinforcement learning approach enhances robot cooperation and adapts better to variable environments than traditional methods.

Gaiardelli et al. [21] proposed an integrated task scheduling and transportation model in FMS without input or output buffers, using the Sched-T heuristic to minimize makespan. Furthermore, Dabwan et al. [22] integrated predictive maintenance based on IoT with timed Petri nets, generating MILP models that effectively manage unreliable machines, improving system performance.

Liu et al. [23] developed an enhanced genetic algorithm with three-level coding and a reconstruction operator to solve the combined order grouping and flexible scheduling problem, incorporating buffers and setup times to minimize makespan and stabilize production. In the context of hybrid networks, Ahmed et al. [24] modeled additive manufacturing as either a primary or backup source within a three-stage stochastic framework. Their model optimizes facility location, production quantities, and demand allocation, reducing inventory, backlog, and transportation costs while using additive manufacturing as a buffer against demand fluctuations.

Amjath et al. [25] focused on buffer allocation using finite queue networks, balancing operational efficiency and storage costs. Their model significantly reduces bottlenecks and enhances system performance. On the other hand, Pourvaziri et al. [26] addressed layout design under demand volatility, modeling partial machine flexibility using MILP and employing DOE-GATS, which generated robust and efficient solutions for large-scale problems, demonstrating superiority over benchmark algorithms.

The existing literature underscores the importance of operational flexibility and buffers in flexible manufacturing systems, although many studies have not explored in depth how these variables interact in uncertain production environments or how they align with adaptive buffering policies. In this context, the literature emphasizes the relevance of machine and labor flexibility to adapt production systems to disruptions and maintain efficiency. Machine flexibility is crucial during periods of high demand, while labor flexibility becomes more critical in cases of system failure or uncertainty. While buffers can mitigate variability, excessive use of buffers leads to higher operational costs and inefficiencies. The total flow time of a batch is determined by the responsiveness of flexible resources and the ability to adapt to fluctuating conditions. Inefficient use of buffers can further slow flow, disrupt production schedules, and unnecessarily extend batch flow times. To optimize flow, effective management of flexibility and buffers is essential. By adjusting these factors to operational conditions, resource overload can be prevented, bottlenecks minimized, and a balance between flexibility and buffer use can be maintained to improve overall system performance.

This study contributes to this gap through a factorial analysis that evaluates how different types of operational flexibility and inventory levels affect flow time in uncertain production environments. Furthermore, it aims to align operational flexibility with adaptive buffering policies, thereby improving response capacity and efficiency in a JS-FMS.

The remainder of this document is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the problem formulation. Section 3 describes the experimental design. Section 4 details computational experiments and analyzes the results, evaluating the combined impact of various types of manufacturing flexibility, with and without the use of buffers, on the system’s responsiveness; key findings are also discussed. Finally, Section 5 offers the study’s conclusions and proposes directions for future research.

2. Problem Formulation

Recently, advances in smart manufacturing have extended the equilibrium model principles proposed by Newman et al. [17] and Parker and Wirth [27] into digital and cyber–physical environments. These authors established the theoretical foundation describing how production systems balance uncertainty through flexibility and inventory. Today, such principles are reinterpreted within the frameworks of Industry 4.0 and 5.0, where digital capabilities enable predictive and autonomous management of variability. Technologies such as IoT-based predictive maintenance [28], algorithmic resource scheduling through real-time optimization [29] and AI-driven dynamic flexibility [30] expand the role of flexibility, transforming it into a data-informed adaptive capability that continuously adjusts resources according to the system’s state. In this context, the proposed model preserves the classical logic of balancing flexibility and buffers but updates it by recognizing that buffers can evolve into dynamic schemes, in which their size or function adjusts according to operating conditions and prevailing uncertainty. Thus, buffers cease to be static reserves and become active regulators, integrating traditional foundations with the predictive, self-organizing, and resilient paradigms of smart manufacturing.

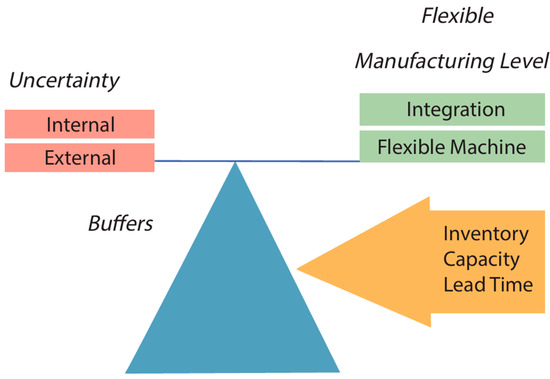

On this conceptual basis, the model developed herein builds upon the fundamentals established by [17], and incorporates the contributions of [27], who introduced a dynamic equilibrium model that explains production system variability and the mechanisms that counteract it, such as inventory and system flexibility. The model emphasizes the balance between internal and external uncertainty through the integration and flexibility of machines and resources (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Balance between manufacturing flexibility and external uncertainty, adapted from [17].

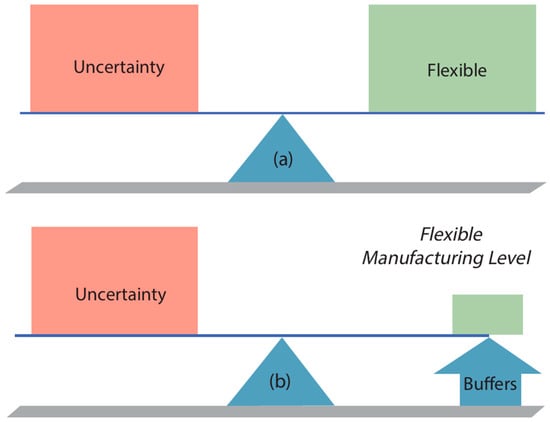

From this approach, two limiting situations emerge that warrant analysis. First, when the triangle of buffers is very small or nonexistent, a perfect balance between uncertainties and flexibility can be achieved, provided the variety of flexibility equals or exceeds the variety of uncertainties. Second, balance can be achieved solely by using buffers when flexibility levels are insufficient. Figure 2 shows these two scenarios: situation (b) highlights how combining flexibility and buffers effectively balances both external and internal uncertainties.

Figure 2.

Newman’s model: (a) No buffers; (b) With buffers.

A key issue arising from Figure 1 and Figure 2 is the apparent disconnect between the role of buffers in mitigating flow time uncertainty and their impact on system responsiveness. While the combined impact of flexibility and buffers are often proposed as solutions to reduce flow time variability, their contribution to overall system responsiveness is not always fully understood.

In this context, a critical question emerges: Are all buffers equally effective in enhancing response speed, or does their effectiveness depend on the presence of other flexibility mechanisms? For instance, how might the introduction of labor flexibility influence the impact of buffers on system responsiveness? It is possible that labor flexibility could either amplify, neutralize, or even diminish the benefits of buffers.

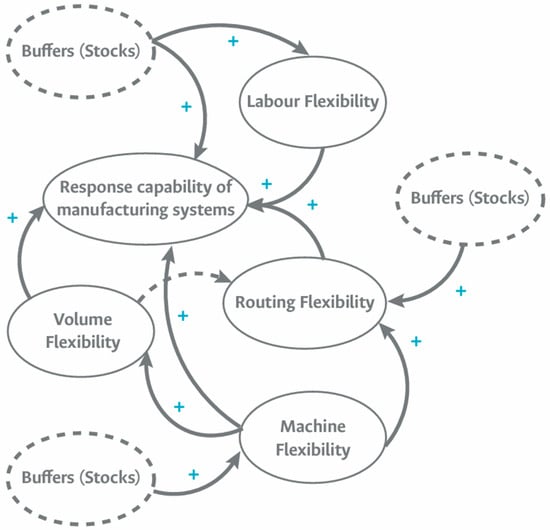

The questions outlined above were partially addressed by [19], who analyzed the relationship between uncertainty and machine and labor flexibility in the garment industry. Based on this work, this study aims to expand the investigation by examining the interplay among a broader range of flexibility types, inventory buffers, and their collective influence on the response capacity of manufacturing systems under internal and external uncertainties. To this end, a conceptual model is proposed to explore the relationships between flexibility types, buffers, and system responsiveness.

Figure 3 shows a diagram depicting key flexibilities in manufacturing systems facilitated by buffers, particularly inventory (stock). The diagram employs a standard notation: a positive (+) influence between two variables indicates that an increase in A leads to an increase in B, while a decrease in A result in a decrease in B. In contrast, a negative (−) influence indicates an inverse relationship, where an increase in A causes a decrease in B, and conversely, an increase in B leads to a decrease in A.

Figure 3.

Influence diagram of different types of flexibility and buffers on the responsiveness of a manufacturing system.

The diagram’s construction is informed by the definitions of flexibility and the relationships outlined in the works of [31,32,33]. Notably, the relationship between volume flexibility and route flexibility is represented with a dashed line, as Parker and Wirth [27] describe it as a combined (+ −) relationship. This reflects that both flexibilities are directly influenced by machine flexibility, and the use of route flexibility can result in positive or negative variations in production volumes.

Furthermore, Figure 3 emphasizes the positive impact of buffers on both flexibility and system response speed. This assertion will be validated through a series of simulation experiments.

3. Experimental Design

To address the problem and analyze the average time parts remaining in the manufacturing system, an experimental framework was developed that incorporates various structural elements and system disturbances. This study considers four dimensions of flexibility: machine flexibility, labor flexibility, volume flexibility, and route flexibility. It also includes buffers, which are defined as intermediate inventories located at the entry points of bottleneck resources.

Disturbances considered include both internal and external factors. Internal disturbances encompass variability in processing times, absenteeism, and machine breakdowns, while external disturbances pertain to demand variability.

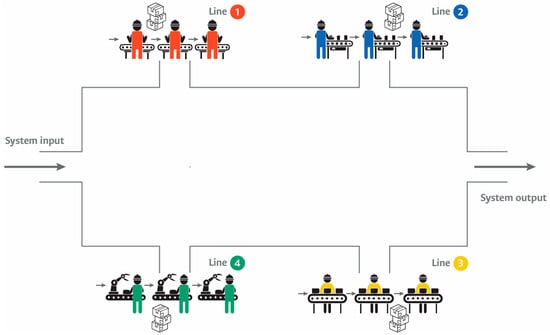

Figure 4 shows the production system modeled using Arena software, version 16.2. The machines are organized into four work lines, with each line comprising three machines arranged in a flow shop configuration. Each machine has a fixed location within the system layout and is assigned to a single worker, which represents a typical setup in knitwear manufacturing companies.

Figure 4.

Production system.

For the representation of Figure 4, detailed technical information about the products is used, including the set of required operations, the types of machines involved, operation specifications, and processing times. Additionally, the model incorporates probability distributions for machine failures and worker absenteeism, defined according to parameters established by [34].

Both flexibility and buffers are represented at three levels. The low level (L) corresponds to a condition of minimal or nonexistent flexibility, characterized by the absence of buffering strategies or flexibility mechanisms applied to machinery, workforce, or production processes. Under these conditions, production systems exhibit high rigidity, possessing a limited capacity to adapt to changes or variability, consequently restricting their responsiveness to operational disturbances. This absence of treatment implies that neither the equipment nor the processes are configured to manage fluctuations in demand or disruptions within the manufacturing environment.

The medium level (M) represents a balance between the low and high levels, characterized by moderate flexibility, a partial deployment of buffers, and a limited capacity for adaptation within production processes. While systems at this level lack maximum adaptability, they have incorporated certain capabilities to manage variability. This intermediate level permits operational adjustments but still exhibits limitations in agility and responsiveness.

The high level (H) reflects maximum flexibility and extensive buffer utilization. Production processes at this level are highly adaptive, possessing the capability to manage demand fluctuations and disruptions through the strategic deployment of inventories and significant flexibility in both machine and labor. This level enables rapid adjustments, the seamless reconfiguration of production lines, and smooth transitions between different products or production routes.

Based on this characterization, the experimental matrix categorizes flexibility dimensions and buffer capacities into three distinct levels: low (L), medium (M), and high (H). Rather than representing absolute values or industry-specific benchmarks, these levels function as relative categories that reflect incremental gains in the system’s adaptive capacity. Consequently, these defined levels capture varying degrees of resource substitutability, routing alternatives, and production reassignment capabilities—features inherent to a broad spectrum of flexible manufacturing systems. The corresponding operational definitions are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Levels of flexibility factors.

Although the parameterization of these levels is grounded in data from the garment manufacturing industry, in line with the flexibility typology proposed by [33]. The resulting structure is designed to be inherently scalable and generalizable. Consequently, the metrics employed—such as the number of operations per machine, the degree of labor polyvalence, or the count of available production lines—should be interpreted as proportional proxies for flexibility levels rather than as rigid, absolute thresholds

The H, M, and L levels of flexibility were defined using a proportional structure based on resource availability and system responsiveness. For instance, in labor flexibility, the values of 1, 2, and 4 machines per worker represent increasing levels of polyvalence, ranging from complete specialization to full interchangeability between operators and machines. Although these specific values originate from the apparel context, their definition is relative and can be generalized to other sectors by focusing on the proportion of resources or tasks accessible to each operator. Thus, these defined levels are not arbitrary; rather, they constitute a comparative framework for analyzing the relationship between flexibility, uncertainty, and responsiveness across various manufacturing environments.

Orders arrive at the system following a known demand pattern. There are four product types that can be ordered. Each product is assigned a specific, predefined technological sequence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Technological sequence for each product.

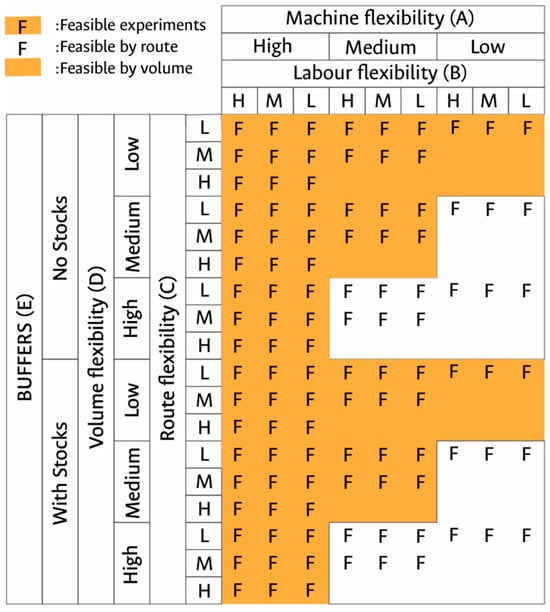

Of the 162 potential combinations derived from the factorial design, only 84 proved feasible. This reduction is attributable to structural constraints inherent to the modeled manufacturing system. In particular, route flexibility is hierarchically dependent on machine flexibility: alternative routes are viable only when machines possess the capability to perform more than one operation. Consequently, combinations involving medium or high routing flexibility are not feasible when machine flexibility is at a low level. Similarly, certain combinations of routing flexibility and volume flexibility become incompatible, as load redistribution across lines necessitates a minimum available capacity. Figure 5 summarizes these dependencies through shaded areas that indicate feasible configurations and blank zones that represent discarded scenarios, thus allowing for a clear and direct identification of the combinations that meet the operational conditions required for simulation.

Figure 5.

Matrix of experimental design.

Within this framework, 84 simulation experiments must be conducted, each with ten replications, to account for internal and external disturbances.

The study explores two alternative inventory utilization approaches to assess the impact of different types of flexibility. In the first scenario, the production line is evaluated without any material inventory. In the second scenario, a buffer of semi-finished products is introduced at the bottleneck machine to ensure the uninterrupted operation of the production line.

Likewise, the study analyzes the influence of the combined use of different types of manufacturing flexibility together with inventory management. The system’s responsiveness is measured in terms of the total flow time of the batches, expressed in minutes.

3.1. Flexibilities

The simulation model is based on a make-to-order manufacturing system comprising four flow shop lines. As various types of flexibility are introduced, the system begins to exhibit job shop characteristics. Tasks or orders adhere to product-specific demand distributions that vary in magnitude and occurrence interval, operating independently. Orders can be initiated on any line, with the processing route determined by each product’s unique technological sequence.

Based on the conceptual model presented in Section 2, Table 3 shows the defined levels for the flexibility factors considered in the experimental design of the manufacturing system. Each factor—machine flexibility, labor flexibility, and volume flexibility—is classified into three levels (low, medium, and high), describing the system’s capacity to adapt to various operating conditions. This classification enables the analysis of the individual and combined impact of each flexibility type on system performance. Furthermore, the system’s organization into production lines facilitates the evaluation of how the assignment of operations and resources across lines influences adaptability and performance under varying conditions and uncertainties.

Table 3.

Defined levels for flexibility factors in the experimental design.

From a broader perspective, this classification facilitates the extrapolation of experimental design to other manufacturing sectors, such as the automotive, electronics, or discrete parts industries. In these contexts, flexibility levels are mapped onto equivalent dimensions of adaptive capacity; for instance, the percentage of multifunction machinery, the degree of workforce polyvalence, or the proportion of capacity that can be reassigned in response to demand fluctuations. Consequently, the findings regarding the interaction between flexibility, buffers, and uncertainty do not depend on a specific industry, but rather on the system’s relative flexibility structure, thereby reinforcing the study’s external validity.

Route flexibility refers to a manufacturing system’s ability to provide alternative paths for products during contingencies like machine failures or worker absenteeism. This capability relies on the availability of redundant resources, which in turn requires sufficient machine flexibility. Route flexibility is considered present when each product has at least one alternative technological sequence.

At high levels, all machines can perform multiple operations, allowing parts to be rerouted without significant disruptions. At a medium level, each product has one alternative route. In contrast, the low level is characterized by the absence of this, meaning no resources are available to reroute production in the event of failures or absences. Table 4 shows the feasible combinations between machine and route flexibility levels, according to the conceptual model.

Table 4.

Relationship between machine flexibility and route flexibility in experimental design.

This study incorporates material buffers by allocating inventories at the input of bottleneck resources, which are identified by their longer processing times. Two conditions are considered: with and without buffer utilization. The primary objective is to ensure continuous bottleneck operation despite potential disruptions. Inventory allocation is based on demand patterns, and its effectiveness is validated through simulation.

Since the modeled system does not consider delivery deadlines, time buffers are not included.

3.2. Data for the Proposed Manufacturing System

Uncertainty data are sourced from [34], as this work is based on real data from the Spanish garment industry.

Processing times follow a normal distribution, accounting for the inherent variability in both machine and operator performance. Each operation is characterized by a processing time with a mean (μ) and a standard deviation (σ), defined as 10% of μ, following the approach proposed by [34]. Each part entering an operation is assigned an individual processing time drawn from this distribution, reflecting the natural variability in manufacturing times.

The operation with the highest average processing time defines the system’s bottleneck. The resource performing this operation is modeled as a limited-capacity resource and is the only one with the longest processing time. All other resources—associated with non-bottleneck operations—are considered to have unlimited capacity and identical, shorter processing times. This configuration creates a controlled environment for evaluating the impact of variability on the overall system performance.

Failure behavior in manufacturing resources is modeled based on their frequency and duration. The time between failures follows an exponential distribution with a mean of 25.93 h, capturing its inherent randomness. Repair duration is represented by a long-normal distribution (mean: 42.6 h; standard deviation: 41 h), reflecting its variability. This statistical characterization allows for a realistic incorporation of operational uncertainty and enables the evaluation of system performance under non-ideal conditions.

Worker absenteeism is modeled considering two main components: frequency and duration. Frequency follows an exponential distribution with a mean of 64.8 days, representing Poisson-type stochastic behavior. Duration is modeled using a discrete empirical function based on observed data, indicating that 60% of absences last one day and 10% extend to five days. This modeling approach enables a precise incorporation of absenteeism uncertainty into the analysis of manufacturing system performance.

The simulation considers two types of demand variations: the time between order arrivals and the type of product requested. The order arrival frequency is modeled using an exponential distribution with a mean of four minutes. Four product types are defined, each arriving independently. Although the distribution is the same for all four, a high degree of variability is introduced, allowing the demand for each product to fluctuate significantly over the simulation period.

Although the data used in this study originate from [34], their application remains relevant within the context of this work. These parameters are not intended to represent the current state of the textile industry but rather serve as a validated experimental basis that enables a controlled analysis of the interaction among different types of flexibility, buffers, and uncertainty. Since both studies were developed by the same author, the value of these data resides in their methodological consistency, which includes well-documented and reproducible distributions of time, failures, and absenteeism. This consistency ensures both the stability of the simulations and the comparability with previous research. Consequently, the data provides a reliable environment for rigorously examining the relative effects of the analyzed variables.

3.3. Assumptions and Considerations of the Models to Simulate

The design of the developed production system is based on the following assumptions:

- Machines operate only when a worker has been assigned, and work is available for processing.

- Setup time for operations is not considered.

- The time workers spend moving between machines is omitted.

- The parts to be processed have pre-assigned routes through the machines, thus maintaining route flexibility.

- All workers possess homogeneous skills.

- The production line is balanced in terms of the number of defined workstations.

- Each production batch consists of 36 pieces.

- The buffer size is equivalent to the lot size calculated according to the economic order quantity (EOQ) model.

Additionally, the model assumes that non-bottleneck resources operate with sufficiently high capacity, ensured through shorter processing times, so that they do not introduce additional flow restrictions. This simplifying assumption allows isolating the marginal effects of the flexibility dimensions and the use of buffers on key performance indicators such as system flow time. However, real production systems often exhibit time-varying or shifting bottlenecks, as well as capacity limitations in resources that are not initially constrained. Under these more complex conditions, system behavior may differ from the patterns observed in this study. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as a controlled, best-case approximation, applicable mainly to environments where critical resources are clearly identified and managed.

The buffer size was determined using the EOQ model, not with the aim of optimizing inventory levels or as a traditional application associated with independent demand settings, but rather as a standardized mechanism to impose a consistent and comparable buffer level across all experimental scenarios. This methodological choice prevents inventory policy from becoming a confounding factor that could obscure or distort the isolated effects of machine and labor flexibility on system performance.

Although more sophisticated alternative approaches exist, such as queueing-theory-based methods or simulation-based optimization, these typically generate buffer sizes that depend on the specific dynamics of each scenario, which may hinder direct comparisons across flexibility configurations. In this regard, the use of EOQ provides a neutral and stable reference point that preserves the internal validity of the experimental design by ensuring controlled and homogeneous conditions.

The sources of uncertainty and variability considered in this study, such as processing times and resource assignment dynamics, are explicitly incorporated through the simulation model, while the structural decisions associated with buffer sizing and system configuration are kept constant.

Moreover, it is acknowledged that omitting setup times and operator travel times may lead to a slight overestimation of the benefits associated with labor and routing flexibility, since these elements introduce significant delays in real job shop environments. In this study, such simplifications are maintained to isolate the pure effects of flexibility and buffer usage; however, their absence implies that the results should be interpreted as a controlled approximation. Future work should explicitly incorporate these times in order to assess their impact in scenarios that more accurately represent industrial operations.

Regarding these assumptions, it should be noted that the simulation period corresponds to a 24-week season, equivalent to 54,000 min (a workday of 450 min, five days per week, four weeks per month, over six months). Ten replications were performed for each simulation run of 54,000 min.

3.4. Model Verification

To ensure the internal consistency and rigor of the developed simulation model, a verification process was conducted by comparing the theoretically estimated average flow time with the results obtained from multiple experimental replications. This procedure confirmed the correct implementation of the system logic and the coherence of the results. Crucially, the model incorporates specific parameters related to processing times, batch consolidation, machine failures, and labor absenteeism. Verification was performed using a Student’s t-test, where the null hypothesis tested was the equality between the simulated value and the expected value.

Production orders are generated according to an exponential distribution with a mean of four minutes and are randomly assigned to one of four product types with equal probability. Although the average interarrival time per product type is 16 min, orders do not immediately enter the manufacturing system. Instead, a batch of 20 orders must first be consolidated before being assigned to a production line, resulting in an average accumulated waiting time of 304 min per order.

Each order passes through three resources in sequence. One of these acts as a bottleneck, with a processing time five times longer than the others (20 min versus 5 min). Consequently, the total processing time per order is 30 min.

In addition, machine failure and labor absenteeism events are modeled. Machine failures occur in the meantime between failures of 25.93 h (1556 min) and an average repair duration of 42.5 min. Labor absenteeism is modeled as a Poisson process with a mean time between events of 93,000 min and an average duration of 1229 min per event.

Table 5 shows the estimated average time a production order remains in the manufacturing system, broken down by resource and considering the effects of failures and absenteeism.

Table 5.

Estimated average order throughput time in the manufacturing system (in minutes).

If the occurrence of three additional failures per resource (129 min) and one labor absenteeism event per resource (3686 min) is considered during the order’s stay in the system, the expected total time in the system is 4756 min + 383 min (failures) + 3686 min (absenteeism) = 8826 min.

To verify this estimate, ten replications of the simulation model were executed without employing any type of flexibility or buffers. The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Average order throughput times per replication in the manufacturing system (in minutes).

A one-sample Student’s t-test was applied using a hypothetical mean of 8826 min. The observed t-value was −2.44, which lies within the acceptance interval [−2.69, 2.69]. Therefore, the null hypothesis of equal means is accepted.

As a result, it is concluded that the simulation model accurately reproduces the expected behavior of the system and is valid for use in subsequent experiments.

4. Results and Discussion

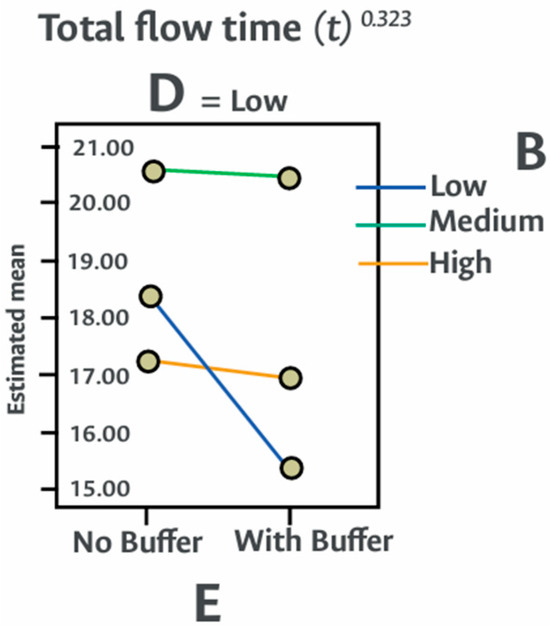

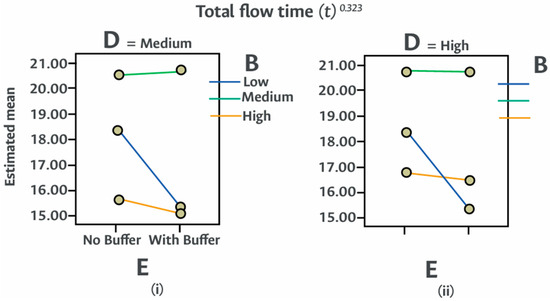

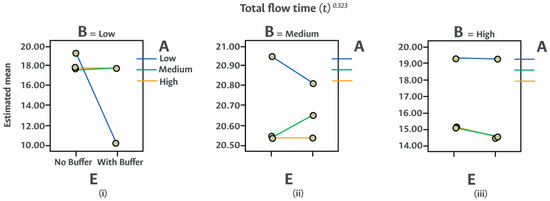

This section presents the findings derived from the simulation under two experimental scenarios: with and without buffer utilization. It analyzes how different combinations of manufacturing flexibilities affect the system’s overall responsiveness. The study particularly focuses on identifying significant interactions among flexibility types and assessing the role of buffers as either a complement to or a substitute for these flexibilities.

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

Table 7 shows the average flow time of batches in the system for each experimental configuration. Each cell displays two values: without buffers (top) and with buffers (bottom). The shortest flow time for each configuration is highlighted in bold. It is important to note that empty cells in the table denote infeasible configurations, meaning those arrangements that could not be successfully simulated or implemented under the given experimental constraints. A subsequent statistical analysis will be conducted to formally validate the significance of the observed differences in flow times.

Table 7.

Average flow time (in minutes) of batches under combinations of flexibilities, with and without the use of buffers.

According to Table 7, in configurations with high machine flexibility (A) and labor flexibility (B), flow times decrease substantially, regardless of the buffer capacity utilized. In contrast, when these flexibilities are at low levels, the use of buffers becomes critical to maintaining acceptable performance. This demonstrates that inventories can effectively and partially compensate for the lack of flexibility, a finding that is particularly relevant in environments with human or technical resource constraints. Furthermore, the data show that the presence of inventories helps to stabilize system performance under less favorable conditions, acting as a backup mechanism that absorbs operational variability and keeps response times within acceptable limits. Table 7 also confirms that, in no instance, system responsiveness is negatively affected by buffers; in the worst-case scenario, flow time remains unchanged.

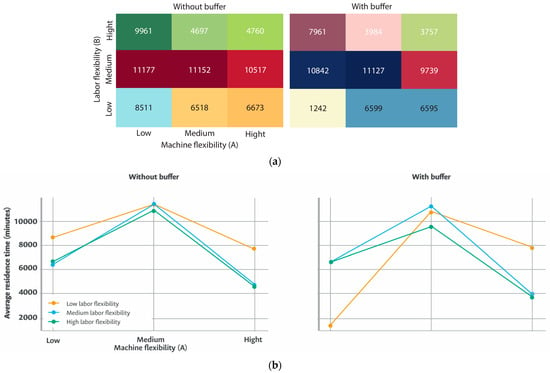

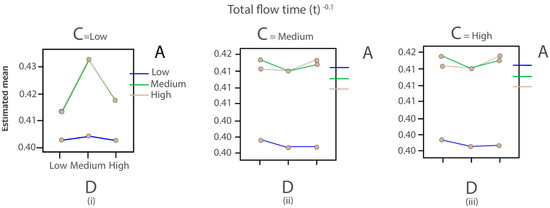

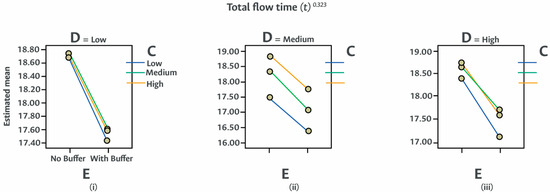

Based on these results and considering the complexity of the factorial design and the large number of experimental combinations, Figure 6a,b focus exclusively on machine flexibility (A) and labor flexibility (B), which exhibited the most significant effects on average flow time. In contrast, volume flexibility (D) and route flexibility (C) showed marginal variations and demonstrated less influential behavior. Consequently, they were excluded to facilitate visual interpretation and highlight the interactions that determine system performance.

Figure 6.

(a) Heat maps of average flow time according to machine flexibility (A) and labor flexibility (B), without buffers (left) and with buffers (right). Lighter shades indicate shorter flow times, while darker shades represent longer delays. (b) Interaction plots between labor flexibility (B) and machine flexibility (A).

In the scenario without buffers, the highest flow time values, exceeding 11,100 min, are concentrated in configurations with low or medium machine and labor flexibility, clearly indicating greater system congestion. The shortest time without buffers (4697 min) is observed with medium machine flexibility and high labor flexibility, thereby highlighting the dominant effect of labor flexibility in the absence of inventories. Upon the implementation of buffers, the reduction in flow time is considerable: the best performance (1242 min) is achieved with low machine and labor flexibility, demonstrating that inventories can compensate for structurally unfavorable configurations. The second-best result (3757 min) corresponds to high levels of both flexibilities, indicating that buffers also enhance already-efficient configurations. Overall, Figure 6a shows that buffers substantially reduce congestion and improve the system’s responsiveness across all different levels of flexibility, serving as a critical mechanism to absorb operational variability and improve performance.

In the scenario without buffers, the pattern reveals a pronounced increase in flow time when machine flexibility rises from low to medium, particularly for low and medium levels of labor flexibility, where times exceed 11,000 min. However, increasing machine flexibility to high levels results in a notable decrease in time, reaching approximately 4800–5000 min. This behavior indicates that, without intermediate inventories, the system is markedly sensitive to the simultaneous combination of medium flexibilities.

In the scenario with buffers, the reduction in flow time is evident across nearly all combinations. Optimal performance (1242 min) occurs with low machine and labor flexibility, thereby indicating that buffers effectively compensate for the system’s lack of adaptability. When machine flexibility is high, times also decrease significantly, reaching values close to 3800 min for medium and high levels of labor flexibility.

Overall, Figure 6b shows that buffers mitigate variations across flexibility levels and reduce flow times in both structurally weak and efficient configurations, consequently contributing to a more stable system.

Before performing an analysis of variance, the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances are verified (Table 8). Each cell presents two values: without buffers (top) and with buffers (bottom).

Table 8.

Verification of statistical assumptions for the analysis of variance. (a) Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality and (b) Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test yielded p-values below 0.05, indicating that the data do not follow a normal distribution. Similarly, Levene’s test provided significant evidence of heteroscedasticity (p < 0.001), reinforcing the need to transform the data prior to conducting the analysis of variance.

To address these deviations, transformations of the dependent variable were applied using the [35] method. The optimal transformation parameters were (t)−0.1 for the results without buffers and (t)0.323 for those with buffers.

Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12 present the full results of the analysis of variance applied to both the original and transformed data for the models without buffer (Table 9 and Table 10) and with buffer (Table 11 and Table 12). The transformation stabilized the variance, a necessary condition for validating the assumptions of the analysis and enabled the detection of effects that were not previously evident. As a result, several interactions involving the use of buffers (factor E) were identified as statistically significant, such as (B*C*E), (A*B*C*E), (A*C*D*E) and (A*B*C*D*E). These interactions, which had not been significant due to high variability, revealed after the transformation a meaningful influence of the buffer in combination with other factors (Table 12). This finding demonstrates that transformation was essential for uncovering hidden relationships among the variables.

Table 9.

Analysis of variance without buffer using original data.

Table 10.

Analysis of variance without buffer using transformed data.

Table 11.

Analysis of variance with buffer using original data.

Table 12.

Analysis of variance with buffer using transformed data.

4.2. Main Findings and Contributions

Analysis of variance reveals important insights into interactions among different types of flexibility. A key contribution of this study is its demonstration that combining high levels of labor and machine flexibility enhances system responsiveness by 44%, partially validating previous findings [34]. However, this work goes further by quantifying a threshold beyond which additional flexibility yields no benefit.

From a managerial standpoint, these findings suggest that investments in flexibility require careful appraisal, as incremental enhancements beyond specific thresholds do not invariably yield proportional operational gains. Operations managers can utilize these identified thresholds as benchmarks to prioritize investments in labor and machine flexibility up to the point where the resulting reductions in flow time are significant. Adopting this targeted approach allows firms to avoid overinvestment with only marginal benefits.

Another significant contribution is the identification of non-additive effects among flexibility types. For instance, medium levels of route flexibility can degrade system performance in the presence of certain combinations of volume and machine flexibility. This counterintuitive interaction, unreported in the previous literature, highlights the need for more careful planning in flexible manufacturing environments.

In practice, these findings caution managers that the isolated introduction of routing flexibility may precipitate congestion and induced bottlenecks if it is not deployed in coordination with other flexibility dimensions. Consequently, production system design decisions should prioritize synergistic combinations of flexibility investments. Neglecting this holistic perspective risks generating localized improvements that prove counterproductive, leading to systemic sub-optimization rather than enhanced overall performance.

This behavior is explained by three primary operational dynamics that emerge primarily under intermediate levels of route flexibility. First, a moderate increase in alternative routes introduces diversions toward non-critical resources. Under medium flexibility, these resources begin to experience transient congestion, effectively shifting the constraint and resulting in longer waiting and processing times. Second, the flow redistribution remains incomplete: there are still insufficient alternative routes to effectively balance the load, which leads to the emergence of new, induced bottlenecks that are not present under either low or high levels of flexibility. Finally, the moderate increase in routing options amplifies variability in arrival sequences to shared resources, intensifying competition for capacity and increasing queueing times. Taken together, these factors explain why intermediate route flexibility can degrade system performance, whereas at high levels this effect disappears due to sufficient redundancy to distribute the load more evenly.

Moreover, competition for shared resources remains a critical factor. Increasing the number of flexibility types does not always improve performance; it can, in fact, lead to the saturation and overexploitation of certain resources. In this context, volume flexibility exhibits more volatile behavior, showing an average 7% efficiency gain when combined with machine flexibility. Conversely, route flexibility does not significantly contribute to reducing flow time.

These results imply that, from an operations management perspective, volume flexibility should be viewed as a complementary asset rather than a substitute for other structural flexibilities. Its effectiveness is contingent upon a robust foundation of labor and machine flexibility, which underscores the necessity of strategically aligned flexibility policies. Consequently, managers should prioritize an integrated framework in which structural capabilities enable effective and scalable volume adjustments.

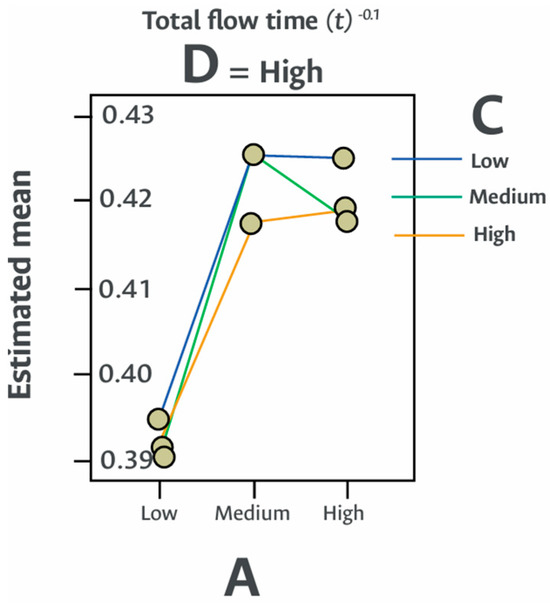

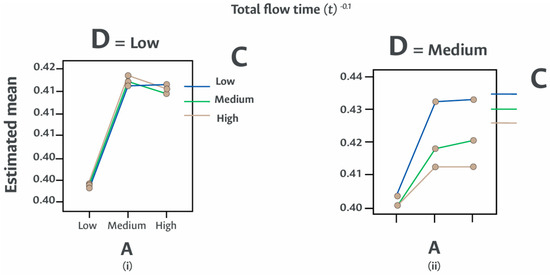

Before presenting the graphical results, it is essential to clarify that the response variables were subjected to a Box–Cox transformation. The purpose of this transformation was to ensure compliance with the normality and homoscedasticity assumptions required for the analysis of variance. The estimated transformation parameters were λ = −0.1 for the scenarios without buffers and λ = 0.323 for the scenarios with buffers. These parameters were applied consistently across all subsequent analyses and figures.

However, to facilitate the practical and operational interpretation of the findings, the key results are presented in their original units (minutes). For this purpose, the baseline corresponds to the average flow time in the system without flexibility or buffers (8.826 min), a value obtained during the model verification stage. Therefore, although Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 display values transformed using the Box–Cox procedure, the textual discussion is conducted using real-time units to enhance interpretability and practical relevance.

Figure 7.

Permanence time (transformed) versus machine (A), route (C) and volume (D) flexibilities without the use of buffers.

Figure 8.

Permanence time (transformed) versus volume (D), route (C) and machine (A) flexibilities without the use of buffers. The results show that higher levels of machine flexibility significantly reduce flow time, while route and volume flexibility exhibit minor effects.

Figure 9.

Permanence time (transformed) versus route (C), machine (A) and volume (D) flexibilities without the use of buffers. The results indicate that at low route flexibility levels (C = Low), medium machine and volume flexibilities increase total flow time, suggesting an adverse interaction between these factors. As route flexibility increases (C = Medium, High), the system exhibits more stable flow times, and low machine flexibility tends to minimize permanence time.

Figure 10.

Transformed flow time versus the combined impact of labor (B) and volume (D) flexibilities with the use of buffers (E).

Figure 11.

Transformed flow time versus the combined impact of volume (D) and labor (B) flexibilities with the use of buffers (E). The results show that the inclusion of buffers consistently reduces total flow time across all levels of labor and volume flexibility. The reduction is more pronounced when labor flexibility is low, indicating that buffers compensate for the limited adaptability of the workforce.

Figure 12.

Transformed flow time versus the combined impact of labor (B) and machine (A) flexibilities with the use of buffers (E). The results show that the inclusion of buffers reduces total flow time across all combinations of machine and labor flexibilities. The effect is most significant when labor flexibility is low, highlighting the compensatory role of buffers in systems with limited workforce adaptability.

It is important to clarify that the Box–Cox transformation was employed exclusively to satisfy the assumptions of residual normality and homoscedasticity, thereby ensuring the statistical validity of the analysis of variance. Significance tests and the identification of interactions were conducted on the transformed scale; however, the substantive interpretation of the effects relies exclusively on the original variable (minutes). Once the significant factors and interactions were identified, the patterns were re-examined on the real scale, confirming that the direction, relative magnitude, and importance of the effects do not exhibit qualitative changes. Therefore, the transformation does not introduce ambiguities, nor does it restrict the practical interpretation of effect sizes, and the operational implications remain fully traceable in real time units.

Figure 7 shows the joint effect of machine, route, and volume flexibility. When converting the results back to the real scale, it is observed that increasing machine flexibility from low to medium raises the flow time from approximately 8100 min to around 8600 min, irrespective of the route flexibility level. This confirms that certain increases in flexibility may induce congestion, particularly when resources are not properly coordinated.

This counterintuitive behavior can be attributed to several operational mechanisms that emerge when machine flexibility reaches intermediate levels. At this stage, job flows tend to concentrate on a limited subset of semi-flexible machines, increasing congestion and extending waiting times.

Moreover, because labor flexibility does not expand at the same rate, competition over shared resources intensifies although machines can process a wider range of operations, the system does not always have the corresponding labor capacity to support this expanded capability.

The resulting incomplete redistribution of work also gives rise to new emergent bottlenecks that differ from the system’s structural bottlenecks and appear specifically at medium flexibility levels.

Taken together, these factors explain why flow time may increase when moving from low to medium machine flexibility. Notably, this effect disappears at high flexibility levels, where full redundancy enables a more efficient balancing of workloads across resources.

The lowest flow time, close to 8000 min, is achieved under low machine flexibility combined with high volume flexibility.

In Figure 8 and Figure 9, which complete the remaining combinations without the use of buffers, it can be observed that machine flexibility exerts the greatest impact on reducing flow time, decreasing it by up to 708 min (an 8% improvement). Conversely, volume flexibility shows a more limited effect (a reduction of approximately 530 min), and route flexibility exhibits only a marginal impact, reducing flow time by just 88 min compared to the baseline scenario.

When buffers are incorporated (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13), the results show substantial reductions in flow time. For example, under conditions of low labor flexibility, buffers decrease the flow time from the baseline of 8826 min to approximately 6300–6400 min, representing improvements of about 28–29%. Furthermore, in scenarios characterized by elevated machine flexibility, the utilization of buffers reduces flow time by up to 2500 min, validating their strategic importance within the production system. From a managerial standpoint, these results underscore that buffers can serve as a critical compensatory mechanism when system flexibility is limited or costly to implement. This allows organizations to substantially enhance responsiveness without necessitating extensive structural reconfigurations.

Figure 13.

Transformed flow time versus the combined impact of volume (D) and route (C) flexibilities with the use of buffers (E). The results indicate that buffers consistently reduce total flow time for all levels of volume and route flexibility. The reduction is more evident when route flexibility is low, suggesting that buffers enhance system responsiveness when routing options are limited.

In summary, the quantitative results, expressed in minutes, demonstrate that labor flexibility has the greatest impact, reducing flow time by approximately 1940 min. This is followed by machine flexibility (708 min), volume flexibility (530 min), and finally route flexibility, whose effect is marginal (88 min). These values correspond to reductions of approximately 22%, 8%, 6%, and 1%, respectively, relative to the baseline scenario without any flexibility.

These empirical results offer actionable insights into decision-making, enabling managers to prioritize investments with the highest projected impact on system performance. Specifically, the findings identify labor flexibility as a paramount strategic lever, whereas routing flexibility is characterized as a secondary mechanism that should be approached with caution and integrated alongside complementary adaptive strategies.

A notable result is that labor flexibility exhibits the largest main effect and magnitude of impact on reducing flow time (22%), clearly outperforming the other flexibility dimensions. This dominant effect is explained by the fact that labor flexibility acts as a primary buffer against both process variability and resource variability, specifically in the presence of combined equipment failures and personnel disruptions. In the event of machine failures, the ability to reassign and cross-train operators sustains the operational viability of alternative routes, preventing workload accumulation at the system constraint. Similarly, labor flexibility effectively mitigates capacity losses associated with absenteeism or limitations in personnel availability, which, in a job shop environment, can halt entire workstations even when alternative machines are structurally available. By sustaining operational continuity under these two combined sources of variability, labor flexibility mitigates resource utilization variability, drastically reduces queueing times, and prevents the generation of transient induced bottlenecks, accounting for its dominant effect relative to the other types of flexibility.

These results underscore the need for coordinated planning between flexibility and inventory policies to enhance system responsiveness without introducing inefficiencies.

Regarding buffer, the analyses reveal its inclusion consistently reduces or maintains flow time across all scenarios, with no adverse effects. The analysis of variance shows that in 40% of the experimental configurations, system responsiveness improves significantly, surpassing even the performance achieved through low levels of flexibility alone. This suggests that buffers can serve as an effective complementary strategy, particularly where flexibility implementation is limited or cost prohibitive.

According to the analysis of variance, the significant interactions associated with buffer usage are as follows:

- Labor and route flexibility (route flexibility is only present when machine flexibility is enabled);

- machine, labor, and route flexibility;

- machine, route, and volume flexibility (volume flexibility is only present when machine flexibility is enabled); and

- machine, labor, route, and volume flexibility. These interactions reinforce the non-additive nature of the system, where the benefits depend not only on the individual level of each type of flexibility but also on their combination.

In quantitative terms, the average percentage reduction in flow time is contingent upon both the type and the level of flexibility applied. Specifically, in scenarios combining high machine and high labor flexibility, the reduction in flow time reaches 28% and 29%, respectively. In contrast, volume flexibility consistently yielded a 12% impact across all levels, while route flexibility showed reductions of 14%, 11%, and 11% for low, medium, and high levels, respectively. These findings suggest that the greatest benefits of buffer implementation are concentrated in settings with high machine and labor flexibility, indicating a synergistic relationship. Conversely, volume flexibility shows a stable impact, and route flexibility provides limited benefit across all levels.

The experimental results generally support the relationships proposed in the conceptual model; however, a noteworthy exception is identified: volume flexibility exhibits a stronger positive aggregate effect than initially expected in certain scenarios, suggesting that its contribution is highly dependent on specific combinations with other types of flexibility.

Additionally, the use of buffers consistently enhances the effectiveness of all flexibility types, reducing total flow time by approximately 900 to 2600 min depending on the scenario. This confirms their role as a strategic resource for improving system performance under conditions of uncertainty and operational variability.

Consequently, the results underscore the critical need to synchronize flexibility and buffering policies. They demonstrate that buffers should not be viewed merely as passive inventory mechanisms; rather, they function as active managerial instruments that mediate the complex interplay between variability, capacity, and flexibility. In this framework, buffers serve as a stabilizing force within intricate production environments, enabling a more resilient response to operational dynamics.

5. Conclusions

Manufacturing flexibility is widely recognized as a critical strategy for achieving competitive advantage in production systems. However, understanding the interplay between different types of manufacturing flexibility and their responses to various uncertainties is crucial for identifying the most effective strategies for competitiveness. This study evaluates the impact of four combinations of manufacturing flexibility and inventory management on total batch flow time within a JS-FMS. Employing a factorial experimental design with 35 scenarios, the effects of labor flexibility, machine flexibility, route flexibility, volume flexibility, and buffer were analyzed at high (H), medium (M), and low (L) levels.

A total of 84 experimental configurations derived from the full factorial design were simulated. Of these, 35 were found to be feasible and statistically valid, forming the basis for the analysis. The results provide valuable insights into the significance of these combinations for optimizing system performance. A notable finding is a 44% reduction in total flow time achieved by combining high machine flexibility with labor flexibility. In contrast, route and volume flexibility demonstrated negligible impacts on flow time reduction. Furthermore, the study highlights the effectiveness of buffers in significantly decreasing total flow time.

This finding underscores the importance of identifying the most effective combinations of flexibility to enhance manufacturing system responsiveness. Implementing all types of flexibility simultaneously may not be the most effective strategy, as it can lead to diminished performance due to system saturation and potential conflicts between different types of flexibility. A more efficient approach is to select a targeted subset of flexibility with carefully calibrated levels.

Incorporating buffers can significantly enhance manufacturing system responsiveness. However, it is crucial to strategically integrate buffers with the most relevant types of flexibility. A blanket approach to inventory management, especially when coupled with high levels of flexibility across all dimensions, can lead to diminishing returns and even negative consequences, such as increased complexity, higher holding costs, and reduced overall efficiency.

The results of this study provide valuable tools for production managers and system designers to strategically evaluate how to allocate and combine different types of flexibility. Identifying optimal configurations not only enhances operational performance and facilitates adaptation to fluctuating demand but also substantiates investment decisions from a rigorous cost–benefit perspective. Specifically, the 44% reduction in flow time achieved through the combination of high machine and labor flexibility strongly suggests that the greatest strategic returns are derived from coordinating the acquisition of versatile machinery with comprehensive cross-training programs. Conversely, routing and volume flexibility yield only marginal benefits and consequently warrant a lower strategic priority. Furthermore, intermediate levels of flexibility must be avoided, as they risk generating systemic congestion unless accompanied by complementary resource augmentation. Finally, the implementation of buffers represents a cost-effective alternative for improving system responsiveness when significant structural investments are not economically or operationally feasible.

Although the results show that buffers never degrade system responsiveness and, on the contrary, systematically reduce flow time, it is important to recognize that this improvement is not free of operational commitments. In particular, the present study does not explicitly incorporate inventory holding costs or the potential adverse effects associated with increased work-in-process—factors that are essential for a comprehensive cost–benefit assessment. In real settings, elevated work-in-process levels may lead to greater space requirements, risk of obsolescence, increased material-handling complexity, and additional indirect costs. Therefore, although buffers constitute an effective mechanism for mitigating uncertainty, their implementation should be evaluated within an economic framework that simultaneously considers both operational benefits and inventory-related costs.

While these results furnish robust evidence regarding the relative impact of distinct types of flexibility and the strategic use of inventory, their generalizability is subject to significant limitations inherent to the experimental design. The employed model is grounded in a four-line flow system characteristic of the apparel industry, which inherently constitutes a constrained operational environment. Consequently, the findings must be interpreted with caution when extrapolated to alternative manufacturing paradigms, particularly those characterized by elevated levels of automation, greater product-mix variability, or divergent flow architectures. Nevertheless, the patterns identified, such as the synergistic effects of machine and labor flexibility, the non-additive nature of these flexibilities, and the established buffering role of inventories, represent plausible operational mechanisms applicable across a broad spectrum of discrete manufacturing systems. This suggests potential for generalization, the realization of which is contingent upon the degree of structural and operational similarity exhibited by any target system.

Future Work

A set of extensions is proposed to increase the realism of the simulation model and enhance its capacity for generalization. In particular, the following avenues for future research are outlined:

- Introduce variable transportation times between stations, in order to analyze the impact of logistical variability and potential bottlenecks on the system’s responsiveness. It is also relevant to explicitly include setup times and operator movement times, as their omission may overestimate the benefits of labor and routing flexibility. Incorporating these elements would enable the assessment of their effects in scenarios that more accurately represent real industrial operations.

- Implement dynamic buffers whose size can be adjusted according to operational load, demand fluctuations, or actual production requirements. This would allow a more realistic representation of production systems and their behavior under different congestion levels.

- Advance toward a joint time–cost optimization approach, integrating economic metrics such as operating, inventory, and flexibility-related costs. This approach would enable the development of a multi-objective model capable of simultaneously evaluating temporal efficiency and the economic feasibility of the flexible manufacturing system.

- Update the model’s parameterization using databases from contemporary industrial settings, reflecting the technological conditions of digital manufacturing. This would allow the results to be contrasted with current scenarios characterized by advanced automation, IoT integration, and artificial intelligence, thus strengthening the model’s empirical validity and its applicability in intelligent manufacturing systems.

- Empirically validate the model using real data from current production systems, with the aim of comparing the simulation results with observed indicators and reinforcing its external validity and predictive capability in smart manufacturing environments.

- Expand the analysis by incorporating new dimensions of flexibility, particularly product flexibility, with the goal of assessing its impact on overall system performance and enriching the influence diagram developed in this study. In this regard, an explicit hypothesis is proposed: product flexibility may amplify the effect of volume flexibility in the face of variations in product mix and may also interact with routing flexibility by requiring additional or alternative routes to accommodate differentiated operations. These potential synergies or trade-offs justify their evaluation through simulation and statistical analysis, in order to integrate this dimension into the influence diagram and understand its interaction with the four flexibility types currently examined.

- Deepen the study of resource saturation points, with the purpose of identifying the system’s operational limits and optimizing their utilization, thus avoiding inefficiencies associated with overuse or misestimation of flexibility requirements. Additionally, it is proposed to explore the effect of stochastic variability by incorporating uncertainty into critical variables such as demand, processing times, and resource availability, in order to evaluate the model’s robustness under conditions that more accurately reflect complex production environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Q.; methodology, G.M.; software, P.P.; formal analysis, G.M.; Investigation, P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.; writing—review and editing, G.F. and L.Q.; project administration, G.F.; funding acquisition, P.P. and L.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by the DICYT (Scientific and Technological Research Bureau) of the University of Santiago of Chile (USACH) and the Department of Industrial Engineering.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fenta, E.W.; Tsegaye, A.A.; Abere, A.E.; Tefera, G.T. Opportunities in Flexible Manufacturing Systems in the near Future. Global J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2025, 26, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Hu, X.; Mostafa, A.M.M. Path Detectability Verification for Time-Dependent Systems with Application to Flexible Manufacturing Systems. Inf. Sci. 2025, 689, 121404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Younas, M. Development and Application of Digital Twin Control in Flexible Manufacturing Systems. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, J.; Gupta, A.K. Mapping and Visualizing Flexible Manufacturing System in Business and Management: A Systematic Review and Future Agenda. J. Model. Manag. 2024, 19, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilanitasari, P.; Shin, S.J. A Review of Prediction and Optimization for Sequence-Driven Scheduling in Job Shop Flexible Manufacturing Systems. Processes 2021, 9, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Jayswal, S.C. Modelling of Flexible Manufacturing System: A Review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2464–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasi, M.; Altan, B.; Ekici, A.; Özener, O.Ö.; Yanıkoğlu, İ.; Dolgui, A. Production Planning with Flexible Manufacturing Systems under Demand Uncertainty. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Shao, H.; Feng, M.; Han, T.; Wan, J.; Liu, B. Towards Trustworthy Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis via Attention Uncertainty in Transformer. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 70, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternero, R.; Sepúlveda-Rojas, J.P.; Alfaro, M.; Fuertes, G.; Vargas, M. Inventory Management with Stochastic Demand: Case Study of a Medical Equipment Company. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2023, 34, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, L.; Han, T.; Droguett, E.L.; Mosleh, A.; Chan, F.T.S. An Uncertainty-Informed Framework for Trustworthy Fault Diagnosis in Safety-Critical Applications. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 229, 108865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Shi, H.; Han, C.; Meng, F. Research on Production Scheduling Optimization of Flexible Job Shop Production with Buffer Capacity Limitation Based on the Improved Gene Expression Programming Algorithm. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2023, 24, 2317–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherian, A.; Chauhan, G.; Srivastav, A.L. Data-Driven Prioritization of Performance Variables for Flexible Manufacturing Systems: Revealing Key Metrics with the Best–Worst Method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 3081–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, A.; Guizzi, G.; Popolo, V.; Vespoli, S. A Genetic-Algorithm-Based Approach for Optimizing Tool Utilization and Makespan in FMS Scheduling. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckenborg, C.; Schumacher, P.; Thies, C.; Spengler, T.S. Flexibility in Manufacturing System Design: A Review of Recent Approaches from Operations Research. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 315, 413–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangola, W.N.; Mackelprang, A.W.; Burke, G.J. Performing in Uncertain Operating Environments: Buffer Inventory, Volume Flexibility or Both? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 268, 109115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Chang, Q. From Nash Q-Learning to Nash-MADDPG: Advancements in Multiagent Control for Multiproduct Flexible Manufacturing Systems. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, W.R.; Hanna, M.; Maffei, M.J. Dealing with the Uncertainties of Manufacturing: Flexibility, Buffers and Integration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1993, 13, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Newman, W.R.; Hanna, M.D.; Krause, D.R. Uncertainty, Flexibility, and Buffers: Three Case Studies. Prod. Inventory Manag. J. 2000, 41, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Palominos, P.; Quezada, L.; Moncada, G. Modeling the Response Capability of a Production System. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 122, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebacher, G.; Winkler, H. Evaluating Flexibility in Discrete Manufacturing Based on Performance and Efficiency. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 153, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiardelli, S.; Carra, D.; Spellini, S.; Fummi, F. Dynamic Job and Conveyor-Based Transport Joint Scheduling in Flexible Manufacturing Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabwan, A.; Kaid, H.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Alqahtani, K.N.; Ameen, W. An Internet-of-Things-Based Dynamic Scheduling Optimization Method for Unreliable Flexible Manufacturing Systems under Complex Operational Conditions. Machines 2024, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zha, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Cheng, Q.; Cheng, C. An Improved Genetic Algorithm with an Overlapping Strategy for Solving a Combination of Order Batching and Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Heese, H.S.; Kay, M. Designing a Manufacturing Network with Additive Manufacturing Using Stochastic Optimisation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 2267–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjath, M.; Kerbache, L.; Smith, J.M.G.; Elomri, A. Optimisation of Buffer Allocations in Manufacturing Systems: A Study on Intra and Outbound Logistics Systems Using Finite Queueing Networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourvaziri, H.; Salimpour, S.; Akhavan Niaki, S.T.; Azab, A. Robust Facility Layout Design for Flexible Manufacturing: A Doe-Based Heuristic. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 5633–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.P.; Wirth, A. Manufacturing Flexibility: Measures and Relationships. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1999, 118, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katib, I.; Albassam, E.; Sharaf, S.A.; Ragab, M. Safeguarding IoT Consumer Devices: Deep Learning with TinyML Driven Real-Time Anomaly Detection for Predictive Maintenance. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lü, Z.; Ding, J.; Su, Z.; Li, X.; Gao, L. An Effective Local Search Algorithm for Flexible Job Shop Scheduling in Intelligent Manufacturing Systems. Engineering 2025, 50, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Gao, K.; Pan, Q. Optimizing Dynamic Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Using an Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization Framework and Genetic Programming. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2025, 29, 1502–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, P.H.; Mandelbaum, M. Measurement of Adaptivity and Flexibility in Production Systems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 49, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, P.H.; Mandelbaum, M. On Measures of Flexibility in Manufacturing Systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1989, 27, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, A.K.; Sethi, S.P. Flexibility in Manufacturing: A Survey. Int. J. Flex. Manuf. Syst. 1990, 2, 289–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]