A Practical CNN–Transformer Hybrid Network for Real-World Image Denoising

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Excellent feature extraction capability: Convolution operations effectively extract local features of an image.

- Low computational cost: The computation scales linearly with the input size, making the overall model lightweight.

- Long-range dependency: Due to the inherent structure of CNNs, learning relationships between distant pixels is challenging, limiting the ability to capture global patterns and overall context.

- Low generalization performance: Due to their inductive biases and limited receptive fields, CNNs may struggle to capture long-range dependencies and generalize to domains that differ significantly from the training distribution.

- Superior global feature extraction capability: Unlike CNNs, which primarily extract local features, the self-attention mechanism in Transformers computes and integrates global image information across the entire spatial domain, achieving superior performance on benchmark datasets (e.g., Restormer: 40.03 dB PSNR on SIDD).

- High computational cost: The self-attention mechanism exhibits quadratic complexity O (N2) with image resolution, making it difficult to deploy on edge devices or in real-time processing environments.

- Increased memory usage: Transformer-based models generally require more computations than CNNs, leading to higher memory usage, which makes real-time processing of high-resolution images challenging.

- The model should perform well across diverse real-world environments beyond the training dataset, ensuring high practical applicability.

- The structure should have reasonable computational requirements and architecture that allows for efficient deployment on hardware platforms.

2. Related Works

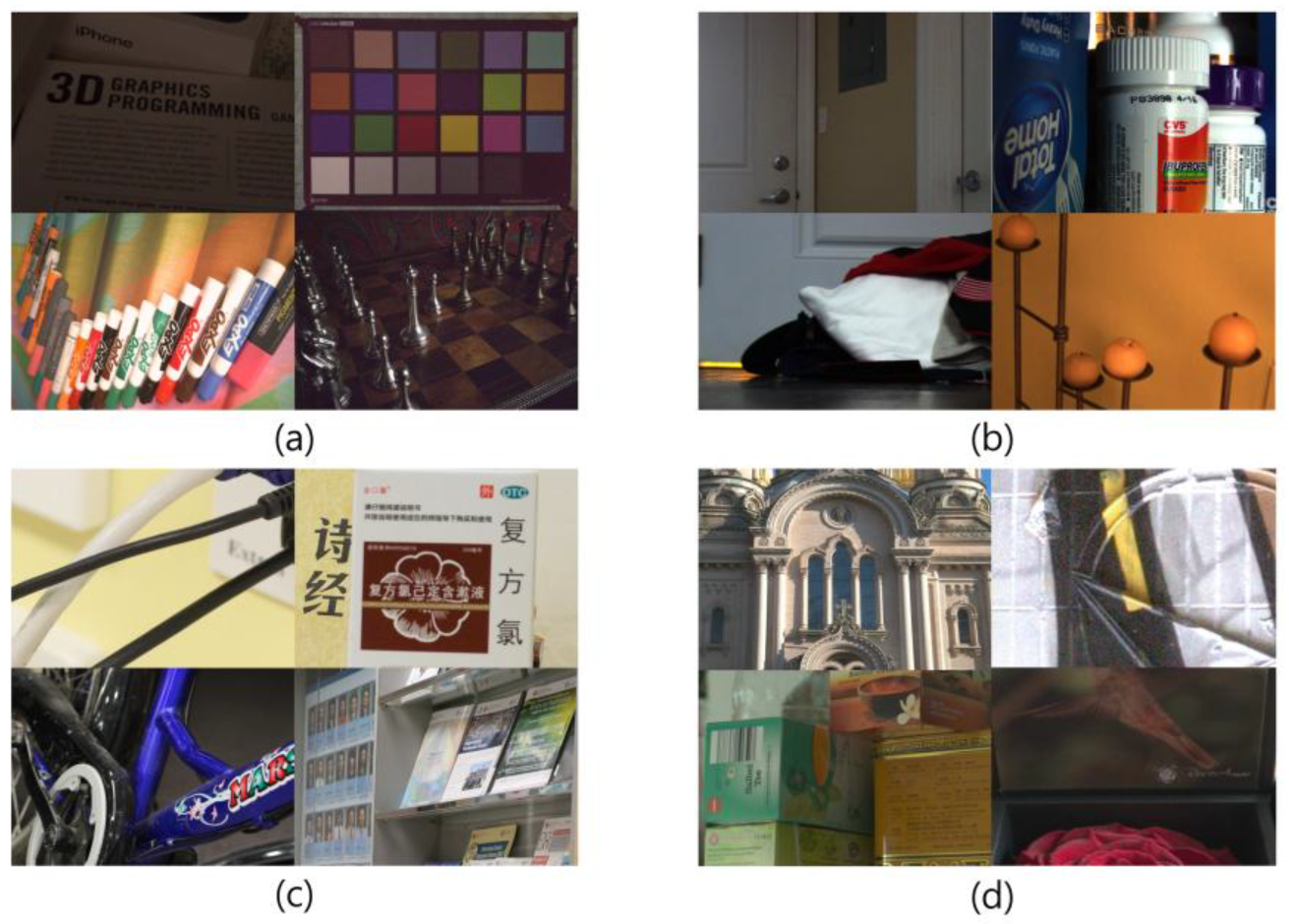

2.1. Image Denoising Dataset

- SIDD (Smartphone Image Denoising Dataset) [16]: Contains 160 scenes captured from 5 smartphone cameras under various lighting conditions. Provides Small (160 pairs), Medium (320 pairs for training), and Full (30,000 pairs for official benchmarking).

- PolyU Dataset [17]: Generates ground truth by capturing the same scene multiple times with different cameras and computing the average values. It comprises 40 scenes with 80 images and 100 cropped images.

- RENOIR [18]: Consists of approximately 100 scenes and over 400 images, provided in pixel- and brightness-aligned format. Furthermore, this dataset focuses on real-world denoising under low-light conditions.

- DnD [19]: Consists of 50 pairs of noisy-clean image pairs and provides 50 noisy images for benchmarking. Also, it extracts 20 patches of 512 × 512 size from each image to provide a total of 1000 patches for real-world photography applications.

- Set12 [20]: Consists of 12 grayscale images with 12 scenes. It is widely used for evaluation of image denoising with artificially added Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) at various noise levels.

- BSD68 [21]: Contains 68 grayscale images from the Berkeley Segmentation Dataset. It represents a diverse collection of natural scenes and is commonly used for benchmarking denoising algorithms with synthetic Gaussian noise.

- CBSD68 [22]: The color version of BSD68 dataset, containing 68 color images with the same resolutions. It is specifically designed for testing color image denoising algorithms on various real-world image content with artificially added noise.

- Kodak24 [23]: Comprises 24 high-quality color images, featuring fine details and rich textures.

2.2. Image Denoising Network

2.2.1. Convolutional Neural Network-Based Model

2.2.2. Transformer-Based Model

2.2.3. CNN–Transformer Hybrid Model

2.2.4. Contribution of Our Study

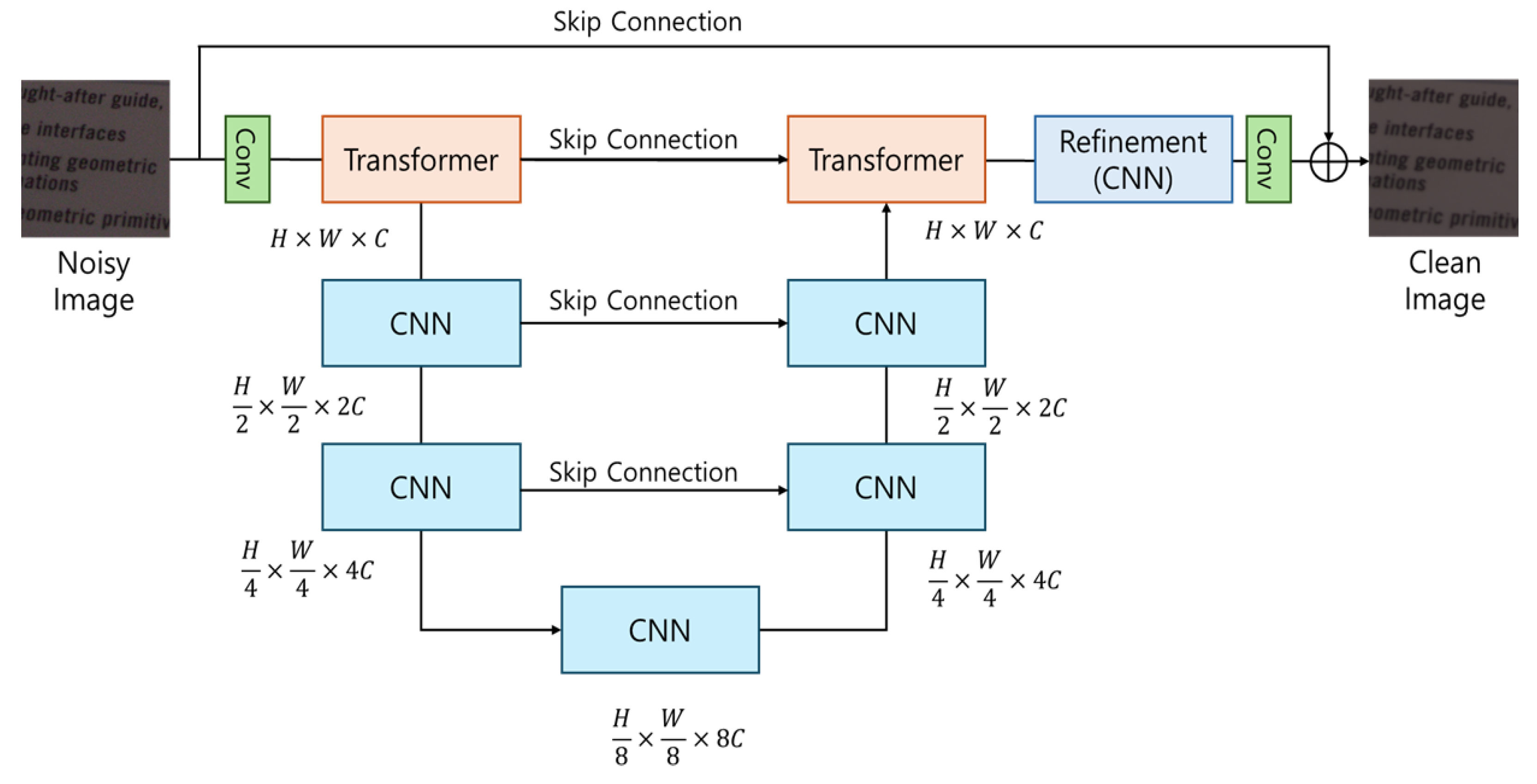

- Strategic Architecture Design: Unlike existing methods that apply Transformersacross the entire network or employ complex multi-branch architectures, we achieve computational efficiency by utilizing a streamlined U-Net structure with Transformer blocks strategically positioned at the bottleneck level, thereby obtaining the benefits of global feature extraction while minimizing computational overhead.

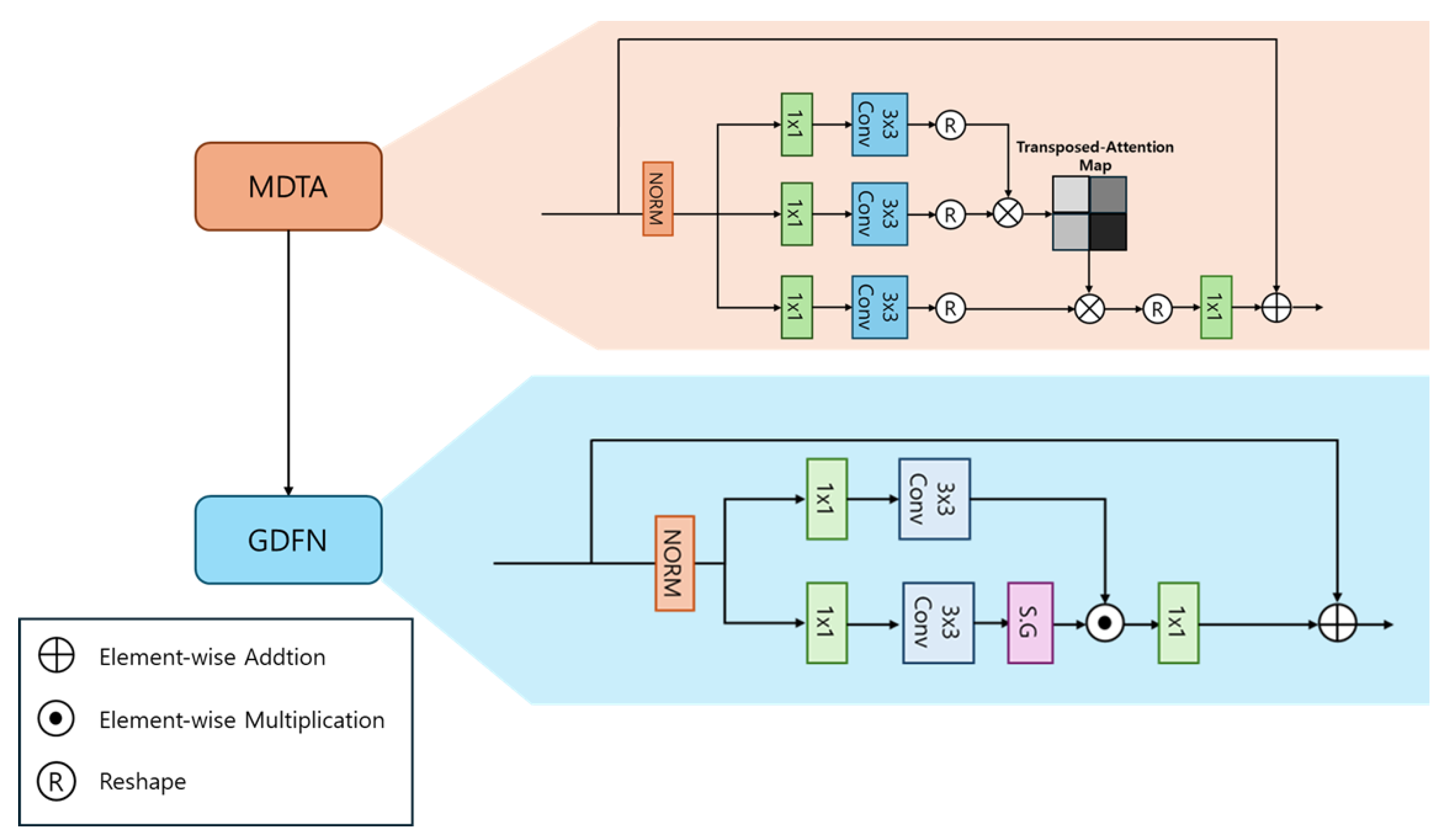

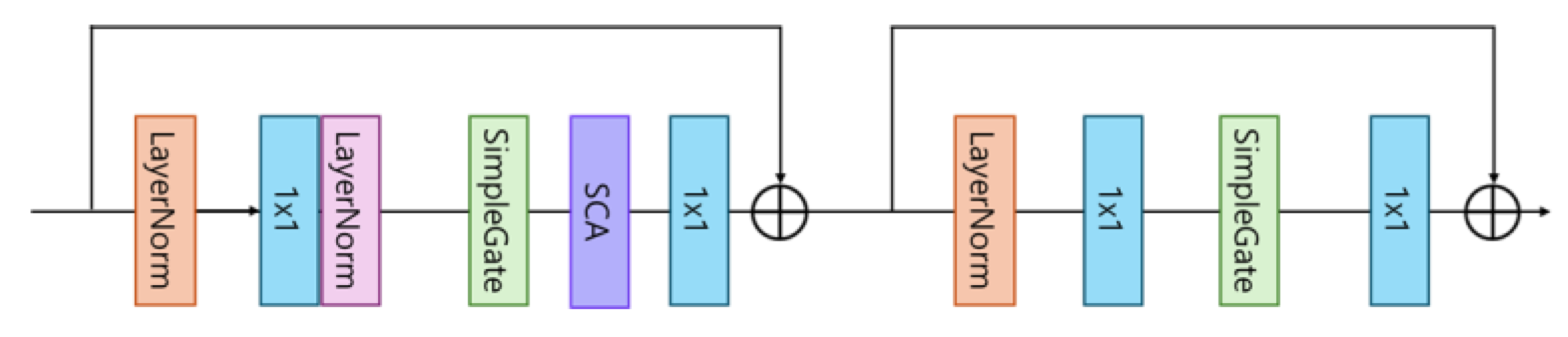

- Selective Component Integration: The proposed approach carefully integrates NAFNet’s lightweight CNN modules with Restormer’s efficient Transformer modules (MDTA, GDFN), combining the strengths of each component while maintaining manageable model complexity through explicit resource constraints (<5 M parameters, <25 G MACs).

- Balanced Performance–Efficiency Trade-off: In contrast to existing methods that either substantially increase computational cost to achieve performance gains or compromise performance for efficiency, the proposed approach demonstrates competitive performance (39.73 dB PSNR, 0.9588 SSIM on SIDD) with practical computational requirements suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

- Simplified Integration: Our approach avoids the complex feature fusion mechanisms required by parallel architectures (HTCNet, HCformer) by using a unified encoder–decoder structure with strategic module placement, resulting in more stable training and easier implementation.

3. Methods

3.1. Architecture

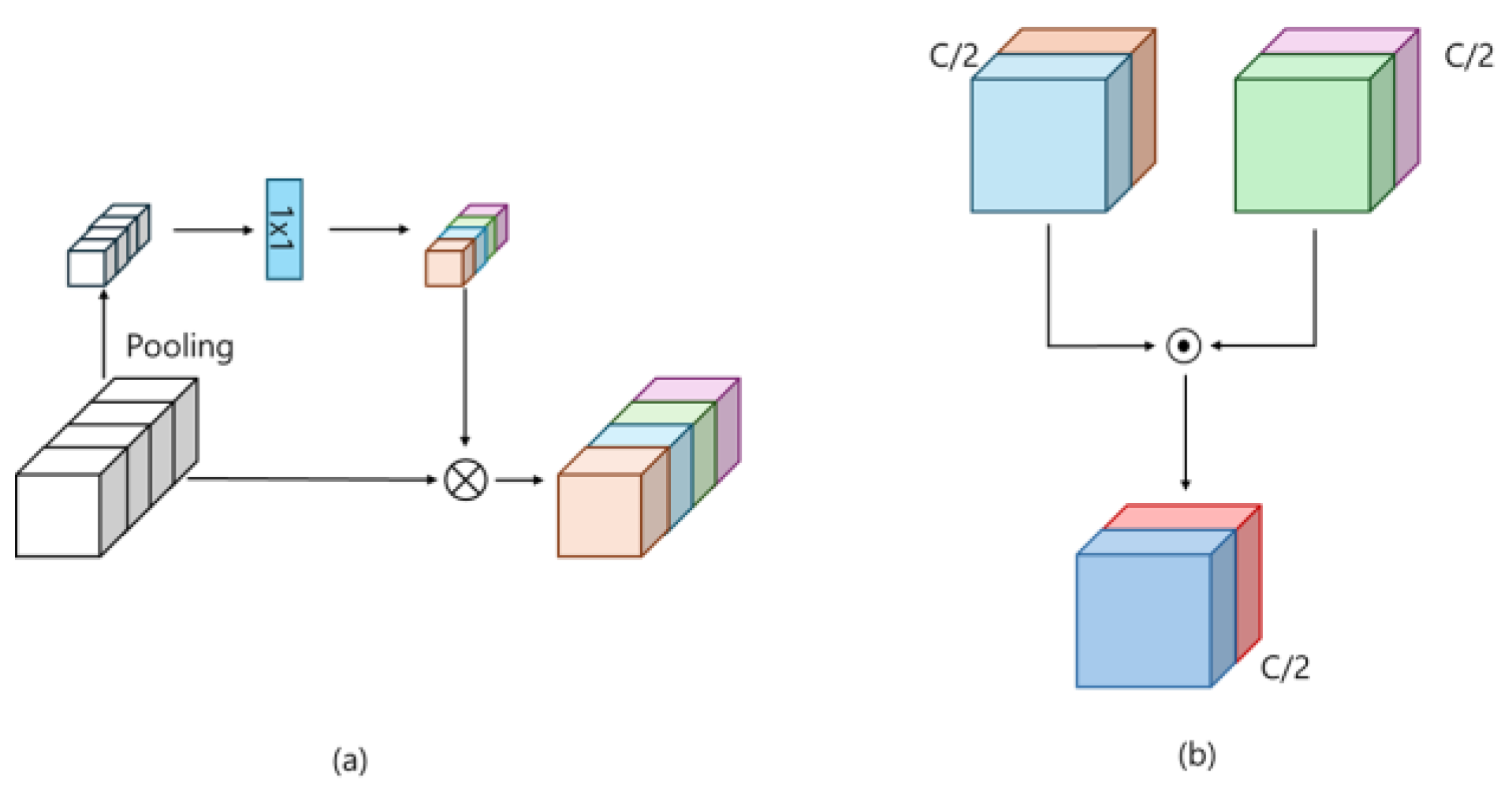

3.2. Transformer Block

3.3. CNN Block

4. Experiments

4.1. Training Settings

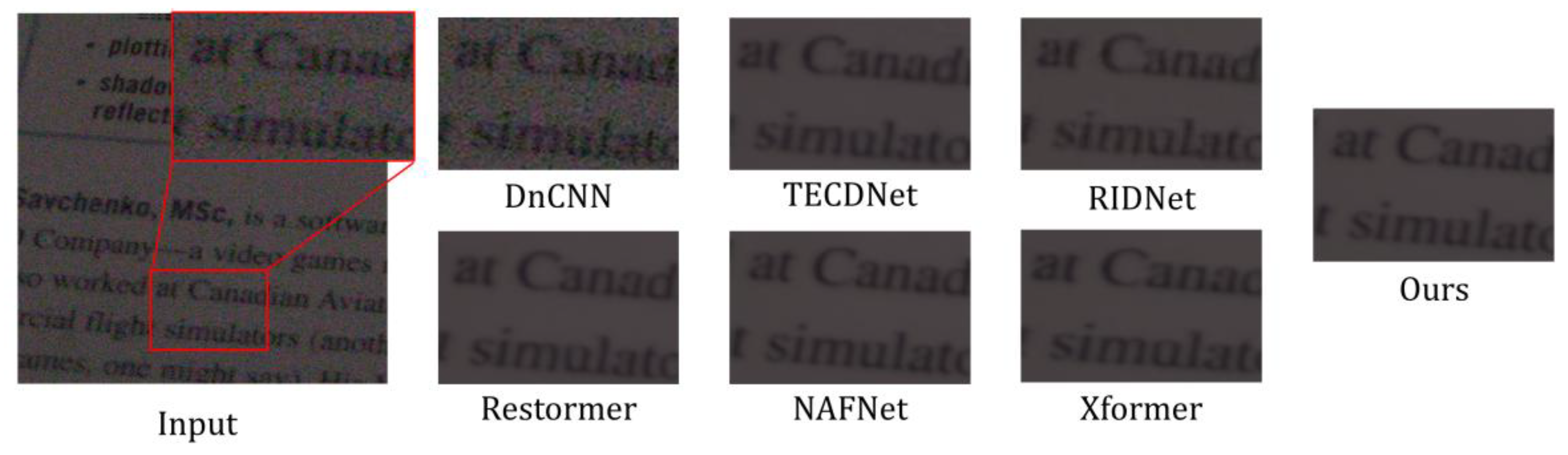

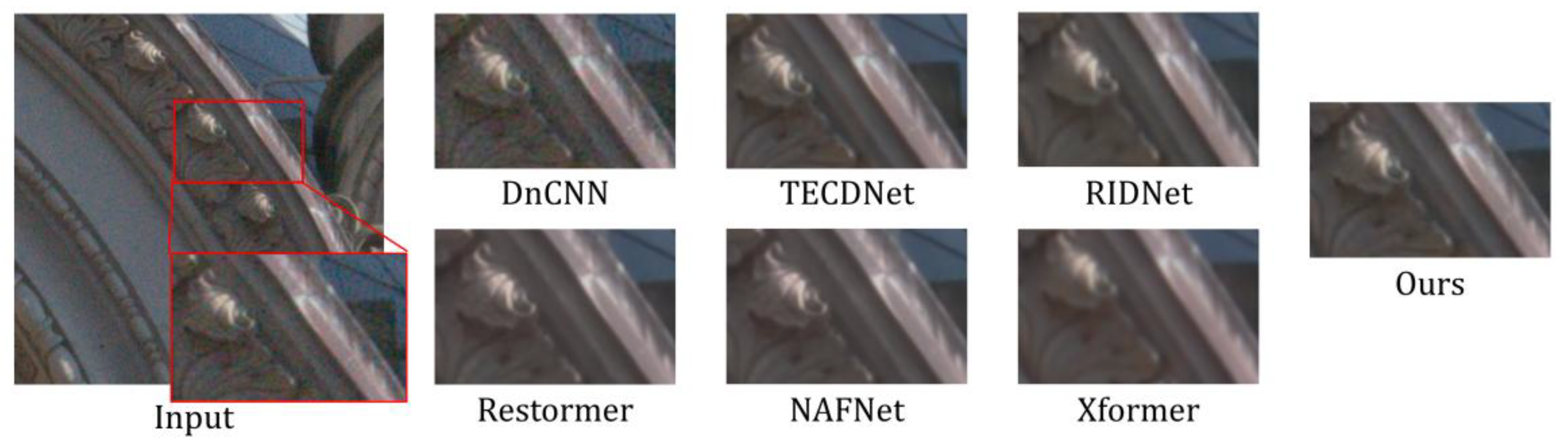

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Model Complexity Comparison

4.2.2. Quantitative Comparison

5. Discussion

5.1. Balancing Efficiency and Performance

5.2. Limitations and Challenges

- High-Resolution Image Processing: The current model is optimized for 256 × 256 resolution, and memory usage and computation time increase dramatically when processing high-resolution images above 4 K.

- Real-Time Processing and Hardware Integration Constraints: Although more efficient than existing Transformer-based methods, the model still exhibits high computational complexity for integration into actual image sensors or embedded systems, which requires further optimization.

- Performance Improvement Limitations: The baseline model shows slightly lower PSNR performance compared to some SOTA models, while the enhanced version achieves competitive or superior performance. Additional model architecture and computational optimizations may be needed for handling complex noise patterns beyond the scope of standard benchmarks.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, W.; Feng, X. Weighted Nuclear Norm Minimization with Application to Image Denoising. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 2862–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, F. Learning a Convolutional Neural Network for Image Compact-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 4480–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H. Restormer: Efficient Transformer for High-Resolution Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5718–5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image Restoration Using Swin Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cun, X.; Bao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Uformer: A General U-Shaped Transformer for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17683–17693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. FFDNet: Toward a Fast and Flexible Solution for CNN-Based Image Denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 4608–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhang, L. Beyond a Gaussian Denoiser: Residual Learning of Deep CNN for Image Denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 3142–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chu, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Simple Baselines for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Kuang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, T. PA-NAFNet: An Improved Nonlinear Activation Free Network with Pyramid Attention for Single Image Reflection Removal. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 160, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, W. NAFSSR: Stereo Image Super-Resolution Using NAFNet. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Fu, Y.; Huang, T.; Shi, H. Pyramid Attention Network for Image Restoration. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2023, 131, 3207–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H.; Shao, L. Learning Enriched Features for Real Image Restoration and Enhancement. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabov, K.; Foi, A.; Katkovnik, V.; Egiazarian, K. Image Denoising by Sparse 3-D Transform-Domain Collaborative Filtering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007, 16, 2080–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buades, A.; Coll, B.; Morel, J.M. A Non-Local Algorithm for Image Denoising. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Volume 2, pp. 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Fei, L.; Zheng, W.; Xu, Y.; Zuo, W.; Lin, C.W. Deep Learning on Image Denoising: An Overview. Neural Netw. 2020, 131, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhamed, A.; Lin, S.; Brown, M.S. A High-Quality Denoising Dataset for Smartphone Cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D. A Trilateral Weighted Sparse Coding Scheme for Real-World Image Denoising. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, J.; Barbu, A. RENOIR—A Dataset for Real Low-Light Image Noise Reduction. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2018, 51, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plötz, T.; Roth, S. Benchmarking Denoising Algorithms with Real Photographs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2750–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Set12 Dataset. Available online: https://github.com/cszn/DnCNN (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Martin, D.; Fowlkes, C.; Tal, D.; Malik, J. A Database of Human Segmented Natural Images and Its Application to Evaluating Segmentation Algorithms and Measuring Ecological Statistics. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–14 July 2001; Volume 2, pp. 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBSD68 Dataset (Color Berkeley Segmentation Dataset). Available online: https://github.com/clausmichele/CBSD68-dataset (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Kodak Lossless True Color Image Suite. Available online: http://r0k.us/graphics/kodak/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Chen, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chu, X.; Chen, C. HINet: Half Instance Normalization Network for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. Toward Convolutional Blind Denoising of Real Photographs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Po, L.M.; Yan, Q.; Liu, W.; Lin, T. Pyramid Real Image Denoising Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP), Sydney, Australia, 1–4 December 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, C. MemNet: A Persistent Memory Network for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4539–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Barnes, N. Real Image Denoising with Feature Attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3155–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrola-Ramos, J.; Dalmau, O.; Alarcón, T.E. A Residual Dense U-Net Neural Network for Image Denoising. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 31742–31754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Plug-and-Play Image Restoration with Deep Denoiser Prior. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 6360–6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; El-Khamy, M.; Lee, J. DN-ResNet: Efficient Deep Residual Network for Image Denoising. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April 2018; pp. 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H.; Shao, L. Multi-Stage Progressive Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14821–14831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Kong, Y.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Residual Dense Network for Image Restoration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 2480–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Qiao, Y.; Change Loy, C. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zheng, M.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, C.W. A Cross Transformer for Image Denoising. Inf. Fusion 2024, 102, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. HAT: Hybrid Attention Transformer for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 17931–17941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Dong, J.; Ge, J.; Li, M.; Pan, J. Efficient Frequency Domain-Based Transformers for High-Quality Image Deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 5886–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Y. Efficient Frequency-Domain Image Deraining with Contrastive Regularization. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J.; Dong, J.; Kong, L.; Yang, X. Xformer: Hybrid X-Shaped Transformer for Image Denoising. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Ke, C.; Li, K. Hybrid Spatial-Spectral Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Denoising. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024 Workshops; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Cao, G.; Huang, X.; Yang, L. Hybrid Transformer-CNN for Real Image Denoising. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Guo, J.; Wang, J. HTCNet: Hybrid Transformer-CNN for SAR Image Denoising. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 19546–19562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Qiao, Y. Hcformer: Hybrid CNN-Transformer for LDCT Image Denoising. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 2290–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dataset | No. of Scenes | No. of Images Pairs | Data Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real-World Dataset | |||

| SIDD | 160 | 30,000 | Raw, s-RGB |

| PolyU Dataset | 40 | 100 | Raw, s-RGB |

| RENOIR Dataset | 120 | 500 | Raw, sRGB |

| DnD | 50 | 50 | Raw, sRGB |

| Synthetic Datasets | |||

| Set12 | 12 | 12 | Grayscale |

| BSD68 | 68 | 68 | Grayscale |

| CBSD68 | 68 | 68 | sRGB |

| Kodak24 | 24 | 24 | sRGB |

| Network | MACS (G) | Parameter (M) |

|---|---|---|

| DnCNN-17 | 36.57 | 0.67 |

| RIDNet | 6.61 | 0.10 |

| Restormer_32 | 64.46 | 11.74 |

| Restormer_48 | 141.24 | 26.13 |

| NAFNet_32 | 16.11 | 17.1 |

| NAFNet_64 | 63.36 | 67.89 |

| TECDNet (T/C) | 21.90 | 20.87 |

| Xformer | 65.42 | 25.2 |

| Ours_32 | 20.44 | 7.18 |

| Ours_48 | 44.49 | 16.02 |

| Network | PSNR | SSIM |

|---|---|---|

| DnCNN-17 | 23.66 | 0.583 |

| RIDNet | 38.71 | 0.951 |

| Restormer | 40.03 | 0.959 |

| NAFNet_32 | 39.96 | 0.960 |

| NAFNet_64 | 40.30 | 0.961 |

| TECDNet (T/C) | 39.77 | 0.970 |

| Xformer | 39.98 | 0.957 |

| Ours_32 | 39.98 | 0.958 |

| Ours_48 | 40.05 | 0.961 |

| Network | PSNR | SSIM |

|---|---|---|

| DnCNN-17 | 32.43 | 0.790 |

| RIDNet | 39.23 | 0.953 |

| Restormer | 40.03 | 0.956 |

| TECDNet (T/C) | 39.92 | 0.956 |

| Xformer | 40.19 | 0.957 |

| Ours_32 | 39.73 | 0.959 |

| Ours_48 | 39.91 | 0.961 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, A.; Hwang, E.; Kim, D. A Practical CNN–Transformer Hybrid Network for Real-World Image Denoising. Mathematics 2026, 14, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010203

Lee A, Hwang E, Kim D. A Practical CNN–Transformer Hybrid Network for Real-World Image Denoising. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010203

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ahhyun, Eunhyeok Hwang, and Dongsun Kim. 2026. "A Practical CNN–Transformer Hybrid Network for Real-World Image Denoising" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010203

APA StyleLee, A., Hwang, E., & Kim, D. (2026). A Practical CNN–Transformer Hybrid Network for Real-World Image Denoising. Mathematics, 14(1), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010203