Abstract

In this paper, we derive a semi-discrete scheme using the central difference method, which perfectly preserves the conservation of mass and energy for the Hirota equation. By applying the Crank–Nicolson method for temporal discretization, we develop the fully discrete scheme that conserves mass and energy. It is shown that the accuracy of the fully discrete scheme is of the second order in space and time. Because the Crank–Nicolson discretization leads to a nonlinear algebraic system, an efficient iterative solver is proposed that linearizes and solves the resulting five-diagonal matrix at each iteration while treating high-order contributions iteratively to reduce computational cost. Numerical experiments are presented to demonstrate the accuracy and verify the conservation properties.

MSC:

65M12; 65N06

1. Introduction

The Hirota equation is a fundamental nonlinear integrable partial differential equation that plays a significant role in soliton theory and the study of nonlinear waves. This equation has applications across different fields like fluid dynamics and optical physics, where it helps describe phenomena such as localized wave structures and modulational instability. In this work, we focus on the following form of the Hirota equation [1]:

with the initial value

where denotes the imaginary unit, t is the time variable, x is the spatial coordinate, is a complex-valued function, and are the real constants. A given smooth complex-valued function is denoted as . For the Hirota equation, two important invariants need to be considered, namely the mass

and the energy

For Equation (1), when , Equation (1) can be simplified to the conventional form of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE) [2,3], which is a significant nonlinear partial differential equation extensively utilized across multiple domains of physics. If , it will turn into the complex modified Korteweg-de Vries equation (mKdVE) [4]. Therefore, this equation is integrable and can be regarded as a combination of the NLSE and the mKdVE. As a modified NLSE, Equation (1) displays higher-order dispersion and time-delay corrections to the cubic nonlinearity. Owing to the inclusion of higher-order terms and additional nonlinear effects [5,6], it can describe more complex marine phenomena, such as sea depth, bottom friction, viscosity, etc.; these factors must all be considered during the simulation process. In the context of wave propagation within oceanic environments and optical fiber systems, it can be considered a more precise approximation compared to the NLSE.

In 1973, Hirota first formulated the Hirota equation and derived its exact N-envelope-soliton solutions [1]. After that, the Hirota equation has been the subject of extensive scholarly investigation. Ankiewicz et al. [7] investigated rational solutions of the Hirota equation through the application of a modified Darboux transformation technique, and demonstrated numerically that these solutions are closely related to rogue waves arising from chaotic wave fields. Tao and He [8] systematically derived multisoliton, breather, and first-order rogue wave solutions of the Hirota equation through the Darboux transformation, and derived a generalized formulation of rogue wave solutions with multiple tunable parameters via Taylor expansion of breather solutions, providing a theoretical basis for controllable experimental observation of rogue waves. Li et al. [9] constructed high-order rogue wave solutions for the Hirota equation using a parameterized Darboux transformation. Mu et al. [10] conducted an investigation into the higher-order rogue waves of the Hirota equation using a variable separation and Taylor expansion method, providing explicit solutions. In a recent paper, Peng et al. [11] investigate the rogue dn-periodic waves (the rogue wave solutions on the dn-periodic waves background) for the Hirota equation by adopting the Darboux transformation. Notably, Zouraris [12] proposed a linear implicit finite-difference discretization for a Schrödinger–Hirota type equation and proved optimal second-order convergence in a discrete -norm under suitable mesh constraints. However, the scheme did not obtain the conservation of mass and energy. Motivated by these developments, the present paper focuses on constructing a conservative scheme for the Hirota equation that preserves discrete mass and energy.

To preserve mass and energy at the discrete level, we employ a conservative numerical discretization method. Conservative schemes have been widely studied in the context of nonlinear dispersive equations such as the nonlinear Schrödinger equation and the Korteweg–de Vries equation, where preserving invariants like mass, momentum, and energy is crucial for accurately capturing long-time dynamics. For instance, Sanz-Serna [13] and De Frutos [14] proposed time-centered conservative schemes for the NLSE, demonstrating their ability to preserve discrete analogues of conserved quantities and improve numerical stability. Similarly, Furihata [15] developed the discrete variational derivative method, a systematic framework for constructing schemes that preserve conservation laws for a class of Hamiltonian partial differential equations, including the Korteweg-de Vries equation, by discretizing the underlying variational structure. Recently, Li et al. [16] proposed two conservative operator-compensation methods to address the Gross-Pitaevskii equation, which is a variant of the NLSE.

In this paper, we construct a numerical scheme for the Hirota equation utilizing the Crank–Nicolson (CN) method. The combination of high-order derivatives and nonlinear terms characteristic of the Hirota equation results in a highly complex algebraic system upon discretization. Consequently, refining the spatial mesh leads to a substantial increase in computational complexity. Moreover, direct solvers can be applied in principle, but their computational cost becomes prohibitive for the nonlinear algebraic systems arising from such discretizations. To efficiently handle this complexity and maintain numerical stability, a numerical iteration method is proposed to deal with the complicated system of linear algebraic equations, which results from the large stencil. This method can save the computational cost.

The structure of this paper is outlined as follows: In Section 2, we present the spatial discretization of the Hirota equation, and analyze the conservation properties of the resulting semi-discrete system. Subsequently, the fully discrete system is derived by using the Crank–Nicolson method for temporal discretization. Section 3 presents numerical experiments to evaluate the accuracy and verify the conservation properties of the proposed schemes. Finally, conclusions are discussed in the Section 4.

2. Numerical Method for the Hirota Equation

In practical computations, since the solution of the Hirota equation decays rapidly in the far field and satisfies homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions, the computational domain is typically taken sufficiently large so that truncation errors can be neglected. For convenience of presentation, we restrict our attention to the one-dimensional (1-D) spatial case, where the Hirota equation is considered on a bounded interval . The subsequent discussion can be readily extended to two- and three-dimensional settings.

In the 1-D case, the problem, together with the initial and boundary conditions, is formulated as

with the initial condition

and boundary condition

2.1. Semi-Discretized Scheme

Some notations are introduced, before we present a semi-discretized scheme for the Hirota. For a positive integer J, denotes the spatial mesh size , and grid points . Set the index sets as

Given a grid function ( if ), we define the difference operators as follows:

Applying the difference operators to the Hirota equation, we obtain the semi-discrete scheme as follows:

with the initial value

and the boundary condition

where we approximate the nonlinear term by to ensure the conservation properties of the scheme, is the conjugate of .

Next, we investigate the conservation properties of the semi-discretized scheme. For this purpose, we first present the following lemma:

Lemma 1.

Let and be the grid functions for . For , the values of and are the boundary values.

Proof.

Expanding the discrete second-order difference operator , we have

The proof is complete. □

Remark 1.

According to Lemma 1, it can be inferred that

when u and v satisfy periodic boundary conditions or zero boundary conditions.

Theorem 1.

The semi-discretized scheme is capable of maintaining mass conservation in the sense

where

Proof.

Multiply both sides of Equation (9) by to obtain the following:

Subtract the conjugate from Equation (17) to obtain the following:

Sum Equation (18) over and then we can obtain the following:

Subsequently, we will divide Equation (19) into four terms and solve each one individually, where Lemma 1 was used:

This completes the proof. □

Theorem 2.

The semi-discretized scheme is capable of maintaining energy conservation in the sense

where

2.2. Fully Discretized Scheme

Let the time step size be and define the time steps as for . Let denote the numerical approximation of for and . By applying the Crank–Nicolson method in time, the semi-discrete method (9) is discretized as follows:

where

with the initial value

and the boundary condition

By applying Taylor series expansion to the spatial and temporal discretizations, it follows that the truncation error of the scheme is of order , which confirms that the method is second-order accurate in both space and time. This result will be verified in the next section.

The definitions of discrete mass and energy are as follows:

Next, we show the conservative properties of the fully discretized scheme (26).

Theorem 3.

The Crank–Nicolson finite difference method (26) is conservative in the sense that

Proof.

Firstly, we prove the conservation of mass. Multiply both sides of Equation (26) by to obtain the following:

Subtract the conjugate from Equation (32), sum it over , and we can obtain the following:

Then, we will divide Equation (33) into four terms and solve each one individually similar to Theorem 1:

This completes the proof of mass conservation. Furthermore, the proof of energy conservation is similar to that of Theorem 2 for the semi-discretized problem. □

Remark 2.

According to Theorem 3, fully-discrete CN schemes (26) are unconditionally stable.

If the nonlinear term in Equation (26) is not approximated by but instead replaced by or treated in another equivalent form, the mass and energy conservation cannot be proved. And the fully-discrete method is as follows:

Equation (26) results in a nonlinear algebraic system; thus, the solution necessitates an efficient iterative scheme. The following method is employed.

In the process of solving, since solving the linear algebraic equation of the five diagonal matrix requires a large amount of computation, the high-order term is iteratively calculated. Scheme (26) can be written in the following iterative scheme, i.e.,

where l denotes iteration number.

When , , where . can be obtained by numerical iterative calculation when is less than the given threshold.

3. Numerical Results

In this section, we will validate the accuracy, order, and conservation properties of the fully discretized numerical scheme through numerical examples.

Example 1.

In this example, we choose , , , and the initial condition is taken as

We solve the problem on . To implement the CN method, we adopt an iteration algorithm and set the tolerance for the iteration to . This tolerance ensures that the iteration error remains well within the range of the overall numerical discretization error and therefore does not influence the accuracy or conservation properties of the numerical scheme.

Let u denote the ’exact’ solution, which is numerically approximated using a highly refined spatial mesh and temporal step size, for instance, and . Denote by the computed numerical solution. The error function is then defined as . In the present example, we evaluate the maximum norm of the error, given by , at the temporal instant . The spatial accuracy results are presented in Table 1. A time step size of was employed to ensure that errors arising from temporal discretization remain negligible. As shown in Table 1, the spatial discretization attains second-order accuracy. The temporal accuracy is summarized in Table 2. To reduce the impact of spatial discretization errors, a sufficiently refined mesh with size was utilized. The findings demonstrate that the temporal discretization also achieves second-order accuracy.

Table 1.

Example 3.1: Spatial accuracy orders with at time across varying mesh size h.

Table 2.

Example 3.1: Temporal accuracy orders with at time across varying time step .

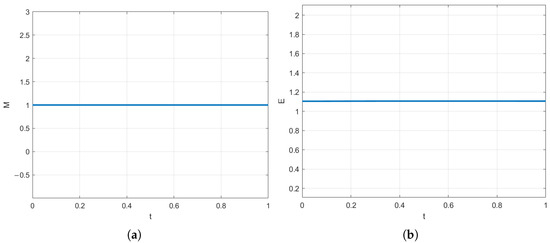

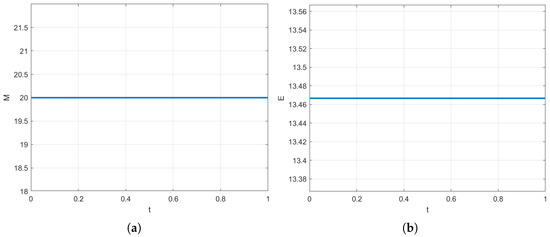

Figure 1 presents the results of numerical simulations of the Hirota equation using the conservative CN scheme, focusing on mass and energy conservation at . The mass conservation curve in the left plot clearly shows that the mass M remains constant at 1 throughout the entire time range , indicating that the numerical method is able to precisely maintain mass conservation. The energy curves also remain flat.

Figure 1.

(a) Mass conservation and (b) energy conservation of Example 3.1.

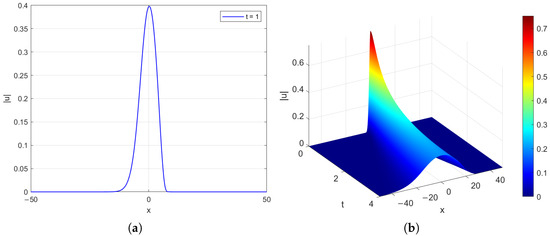

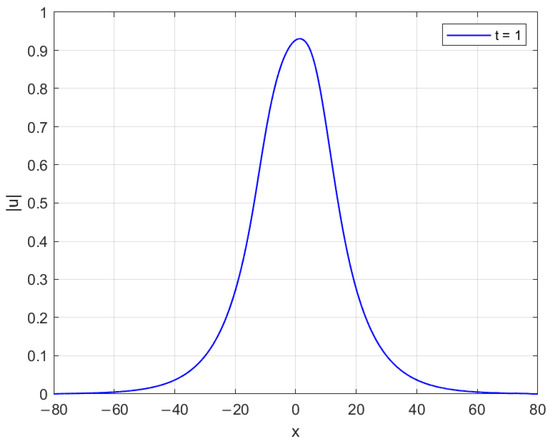

Figure 2 illustrates the numerical behavior of the solution obtained. In panel (a), the soliton profile at time is displayed, showing the expected localized and symmetric wave structure. Panel (b) demonstrate the dynamical evolution of over the time interval with and . For longer-time simulations, the computational domain would need to be enlarged to avoid distortions caused by boundary reflections.

Figure 2.

(a) The wave at time and (b) the long-term behavior from to .

Example 2.

In this example, we choose and the initial condition is taken as

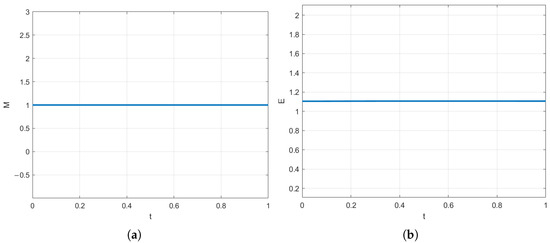

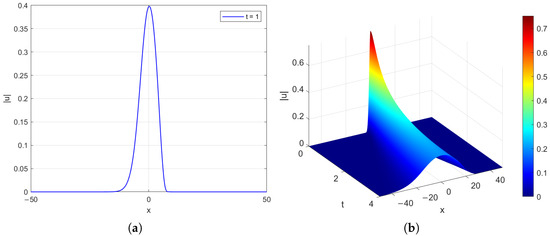

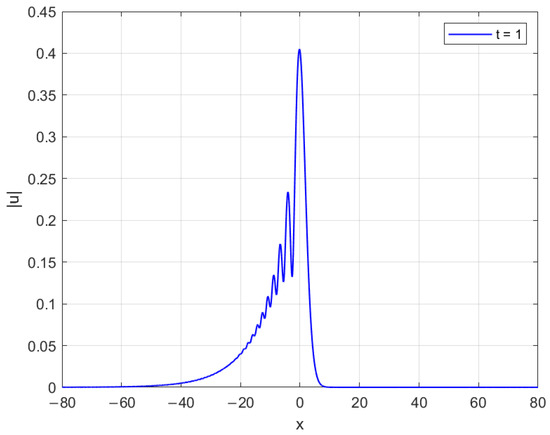

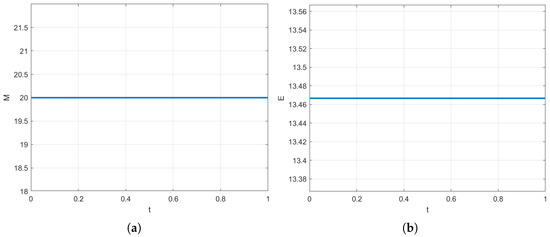

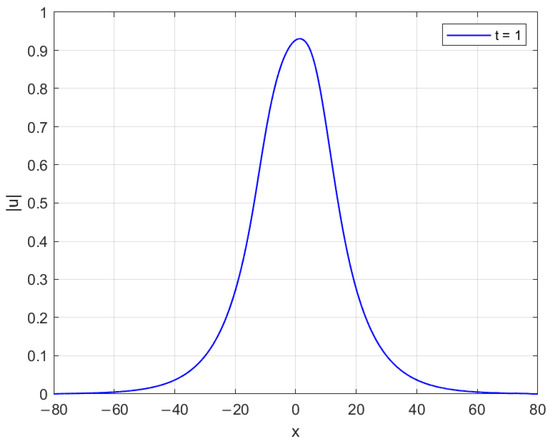

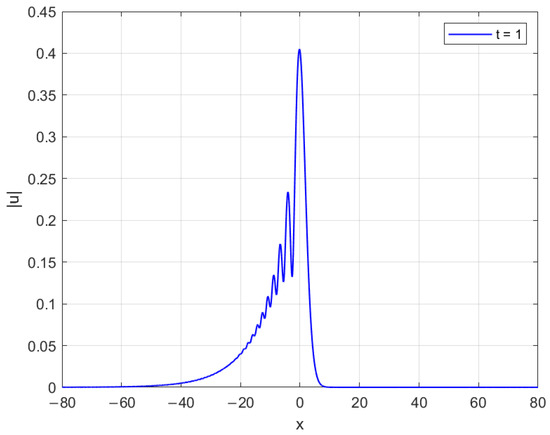

We solve this problem on . For implementing the CN method, we adopt an iteration algorithm, and take the iteration tolerance as . We evaluate the capacity of the CN method to conserve mass and energy while simulating its dynamic behavior. In this study, the parameters are set as and . As illustrated in Figure 3, the results demonstrate that the CN method effectively preserves mass and energy, which aligns with the theoretical expectations established in the numerical analysis literature. Figure 4 depicts the dynamical evolution of the solution at using our proposed approximation for the nonlinear term. Figure 5 contrasts the dynamical evolution at when the nonlinear term is approximated by using the non-conservation scheme (35). The erratic oscillations and non-physical behavior illustrate the instability introduced by these alternative approximations, validating the necessity of our proposed form for ensuring numerical stability and conservation.

Figure 3.

(a) mass conservation and (b) energy conservation of Example 3.2.

Figure 4.

The wave at time .

Figure 5.

The wave at time under different approximations of the nonlinear term.

Example 3.

To further demonstrate the applicability of the proposed conservative scheme, we present a preliminary two-dimensional numerical experiment. We consider the following Hirota equation on a rectangular domain :

with the initial condition

We choose the initial condition to be taken as

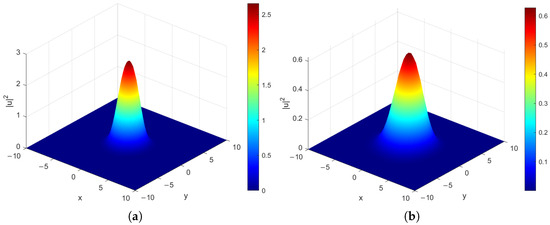

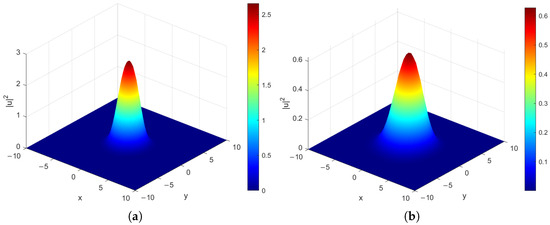

We solve this problem on with spatial step sizes and time step . Figure 6 shows the numerical results at and . This example illustrates that the method can indeed be extended to multidimensional settings, although a complete analysis of the 2D scheme will be presented in future work.

Figure 6.

Surface plot of at (a) and (b) .

4. Conclusions

For the differential discretization of the Hirota equation, we used the central difference method for spatial discretization and the Crank–Nicolson method for temporal discretization. The semi-discrete system obtained exhibits properties of mass and energy conservation under certain conditions. Through derivation and numerical validation, we demonstrate that the fully discrete system also maintains both mass and energy conservation. We also prove that the accuracy of the scheme is second-order in space and time.

Author Contributions

Validation, D.H.; Writing—original draft, J.Z.; Writing—review and editing, X.L. and D.H.; Supervision, D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12272059).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hirota, R. Exact envelope-soliton solutions of a nonlinear wave equation. J. Math. Phys. 1973, 14, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, A.; Kodama, Y. Solitons in Optical Communications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, G.P. Nonlinear Fiber Optics; Academic: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wadati, M. The modified Korteweg-de Vries equation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1973, 34, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkuma, K.; Yoshi, H.; Ichikawa, H.; Abe, Y. Soliton propagation along optical fibers. Opt. Lett. 1987, 12, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulides, D.N.; Joseph, R.H. Femtosecond solitary waves in optical fibers—Beyond the slowly varying envelope approximation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1985, 47, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankiewicz, A.; Soto-Crespo, J.M.; Akhmediev, N. Rogue waves and solutions of the Hirota equation. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81, 046602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.S.; He, J.S. Multisolitons, breathers, and rogue waves for the Hirota equation generated by the Darboux transformation. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 85, 026601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; He, J. High-order rogue waves for the Hirota equation. Ann. Phys. 2013, 334, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.; Qin, Z.; Chow, K.W.; Ee, B.K. Localized modes of the Hirota equation: Nth order rogue wave and a separation of variable technique. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2016, 39, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.Q.; Tian, S.F.; Wang, X.B.; Zhang, T.T.; Fang, Y. Characteristics of rogue waves on a periodic background for the Hirota equation. Wave Motion 2020, 93, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouraris, G.E. A linear implicit finite difference discretization of the Schrödinger–Hirota equation. J. Sci. Comput. 2018, 77, 634–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Serna, J.M. Methods for the numerical solution of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Math. Comput. 1984, 43, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Frutos, J.; Sanz-Serna, J.M. Accuracy and conservation properties in numerical integration: The case of the Korteweg-de Vries equation. Numer. Math. 1997, 75, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furihata, D.; Matsuo, T. Discrete variational derivative method—A structure-preserving numerical method for partial differential equations. Sugaku Expo. 2018, 31, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Cai, Y.; Wang, P. Operator-compensation methods with mass and energy conservation for solving the Gross-Pitaevskii equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 2020, 151, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).