Abstract

This study develops an integrated quality inspection and production optimization framework for an imperfect production system, where system deterioration follows a zero-inflated non-homogeneous Poisson process (ZI-NHPP) characterized by a power-law intensity function. Parameters are estimated from historical data using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm, with a zero-inflation parameter π modeling scenario where the system remains defect-free. Operating in either an in-control or out-of-control state, the system produces products with Weibull hazard rates, exhibiting higher failure rates in the out-of-control state. The proposed model integrates system status, defect rates, employee efficiency, and market demand to jointly optimize the number of conforming items inspected and the production run length, thereby minimizing total costs—including production, inspection, correction, inventory, and warranty expenses. Numerical analyses, supported by sensitivity studies, validate the effectiveness of this integrated approach in achieving cost-efficient quality control. This framework enhances quality assurance and production management, offering practical insights for manufacturing across diverse industries.

Keywords:

quality inspection; zero-inflated non-homogeneous Poisson process; negative binomial sampling; EM algorithm; Weibull hazard rate; imperfect production system MSC:

62F15; 62N02; 62N05; 62C10; 65C20

1. Introduction

In modern manufacturing, achieving high-quality production while minimizing costs is critical, particularly in imperfect production systems designed for customized products under tight delivery schedules [1]. Imperfect production systems, which are prone to deterioration, produce both conforming and defective items, leading to increased costs from rework, warranty claims, and customer dissatisfaction [2,3,4]. Traditional models often rely on deterministic or simple stochastic assumptions, such as constant failure rates or Weibull distributions [1,5]. However, historical data may exhibit inflation, where systems occasionally remain defect-free due to robust design, necessitating advanced models like the Zero-Inflated Non-Homogeneous Poisson Process (ZI-NHPP) with a power-law intensity, estimated via the Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm [6,7,8]. This study proposes an integrated framework to optimize both the production run length and the number of conforming items inspected to minimize the expected total cost, including production, inspection, correction, inventory holding, and warranty costs based on Weibull hazard rates [1]. By integrating system status, defect rates, employee efficiency, and market demands, the model leverages ZI-NHPP to enhance applicability in Industry 4.0 contexts [9]. The findings offer practical insights for cost-effective quality management in manufacturing.

2. Literature Review

The literature on quality management in imperfect production systems encompasses production–inventory optimization, maintenance policies, stochastic deterioration modeling, inspection planning, and reliability analysis. This review synthesizes key contributions from previous studies, highlighting gaps that the current research addresses by integrating Zero-Inflated Non-Homogeneous Poisson Process modeling with Expectation-Maximization estimation for parameter fitting using potentially inflated historical data.

2.1. Imperfect Production and Inventory Models

Imperfect production systems, characterized by defective outputs resulting from system deterioration, require integrated strategies to balance quality and cost effectively. Coordinated strategies that combine production lot sizing, quality control, and condition-based maintenance reduce downtime and costs [2]. Accounting for Type I and Type II inspection errors helps minimize warranty expenses in imperfect systems [10]. Reliability-aware and fuzzy optimization approaches further reduce holding costs and improve decisions under uncertainty [3]. EPQ models with probabilistic demand and collaborative approaches enhance supply chain efficiency through information sharing [11]. Sustainable production–inventory models incorporating quality-improvement investments and preservation technology yield long-term cost savings and environmental benefits [4]. Joint lot-sizing and condition-based maintenance under inspection errors demonstrate adaptability to degradation patterns [12]. Integrated supply chain modeling considering imperfect production, deterioration, and inspection errors underscores the need for coordinated quality control strategies [13].

These studies offer robust frameworks for imperfect production systems [2,3,4,12], but they often assume simple deterioration models and do not address data inflation. The present study extends this work by employing ZI-NHPP with EM estimation to model heterogeneous degradation, thereby enhancing its applicability to imperfect production systems.

2.2. Maintenance and Inspection Policies

Maintenance and inspection strategies are essential for managing deteriorating production systems. Joint optimization of control charts, production cycles, and maintenance schedules with stochastic shift sizes enhances defect detection via adaptive thresholds [14]. Multi-facility inspection and repair planning can be cost-minimized through mathematical programming [15]. Integrating production, preventive maintenance, and dynamic inspection with real-time monitoring reduces downtime in degrading systems [16].

Stochastic processes, particularly NHPP, are widely used to model time-varying failure rates, with applications to anti-corrosion coating maintenance scheduling, distribution-system reliability evaluation, and condition-based maintenance with non-homogeneous degradation [6,7,8]. Bayesian methods further refine maintenance strategies under uncertainty, improving scheduling and warranty planning for hybrid failure modes and deterioration [17,18].

These contributions highlight the efficacy of stochastic models and Bayesian approaches in maintenance [6,7,8,16,17,18]. However, few studies address zero-inflated data, which this study tackles using ZI-NHPP with EM estimation, improving deterioration modeling for production systems.

2.3. Quality Inspection Planning

Effective inspection planning ensures product quality in multi-stage manufacturing systems. Comprehensive reviews synthesize optimization strategies for part quality inspection, emphasizing inspection timing and extent for cost minimization [19,20]. Integrated models that co-optimize preventive maintenance and inspection in serial multi-stage systems use mixed-integer programming to control costs [21]. For imperfect production systems with Weibull deterioration, inspection plans that integrate system status, defective rates, and market demands can be optimized for quality and cost [1]. Supplier quality management shows that investment and incentive-aligned inspection improve sourced quality [22]. Multi-criteria algorithms support the selection of inspection alternatives considering quality, economic, and environmental factors [23]. Ontology-based expert systems automate construction inspection planning for Industry 4.0 [9]. In electronics, automatic optical inspection (AOI) technologies continue to advance defect detection [24]. Attribute-sampling plans for time-truncated life tests are applicable in reliability contexts [25]. Machine-learning-enabled risk-based inspection screening improves efficiency [26]. Under 100% inspection, optimizing process means with inspection errors further strengthens quality control parameters [27].

These works advance inspection methodologies [1,9,19,20,21,22,23] but often rely on traditional deterioration models. This study builds on [1] by integrating ZI-NHPP, addressing inflated data with EM estimation for a robust negative-binomial sampling inspection (NBSI) plan.

2.4. Reliability Analysis and Modeling

Reliability modeling for complex systems has evolved to handle stochastic dependencies and uncertainty. Hybrid reliability analysis with adaptive Kriging improves uncertainty quantification with incomplete interval data [28]. Factor-analysis-based approaches model stochastic dependencies among components [29]. Degradation hidden Markov models with time-varying parameters improve reliability assessment for partially monitored systems [30]. Wiener-process-based re-prediction methods integrate monitoring and historical data for remaining useful life estimation in subsea systems [31]. Distribution families incorporating the exponentiated Weibull address v-shaped and bathtub-shaped failure rates [5]. Competing Weibull mixture models capture heterogeneous and censored data effectively [32]. Mahmood [33] argues that ZIP and ZINB regression models are superior to conventional control charts for the reliability analysis of high-yield processes characterized by zero-inflated defect data. These reliability studies [5,28,29,30,31,32] support the use of Weibull hazard rates in this study and highlight advanced stochastic modeling. However, they rarely address zero-inflated deterioration data, which this study tackles through ZI-NHPP with EM estimation, enhancing applicability to imperfect production systems in Industry 4.0 contexts.

2.5. Research Gaps and Contributions

Although the existing literature provides robust frameworks for managing imperfect production systems, several key gaps limit their applicability to real-world scenarios, particularly in imperfect production environments. First, studies on imperfect production and inventory models [2,3,4,10,11,12,13] often rely on deterministic or basic stochastic assumptions, without adequately addressing heterogeneity and zero-inflation in deterioration data—where systems may experience prolonged defect-free periods due to design robustness or operational variability—potentially leading to overestimated risks and inefficient resource allocation.

In maintenance and inspection policies [6,7,8,14,15,16,17,18], NHPP-based models are prevalent, but they rarely incorporate zero-inflation, leading to biased parameter estimates from datasets with excess zeros. Bayesian methods improve uncertainty handling, yet they typically overlook structural inflation in event counts.

Quality inspection planning research [1,9,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] advances optimization techniques (e.g., mixed-integer programming, ontology-based systems) but usually assumes linear or Weibull deterioration without inflated zeros, which can undermine cost minimization in multi-stage production setups. Similarly, reliability modeling [5,28,29,30,31,32] excels in handling dependencies and censored data but seldom integrates zero-inflated processes for non-homogeneous degradation.

Existing NHPP- and Weibull-based deterioration models generally assume a single failure-generating process and do not address zero-inflated defect patterns, which are common in high-yield manufacturing and may lead to biased intensity estimation. This study advances this literature by introducing a zero-inflated deterioration framework and linking it directly to joint inspection and production-run optimization in imperfect production systems. We model deterioration as a Zero-Inflated Non-Homogeneous Poisson Process (ZI-NHPP) with a power-law intensity function and estimate parameters using an EM-based procedure that properly accounts for inflation in historical defect data. Building on this foundation, we develop a Negative-Binomial Sampling Inspection (NBSI) strategy that determines the optimal number of conforming items inspected and jointly minimizes expected production, inspection, rework, holding, and warranty costs under state-dependent Weibull failure rates. By integrating deterioration dynamics with inspection scheduling and cycle planning—while incorporating defect susceptibility, learning effects, and demand conditions—this study provides a unified decision framework that improves cost-efficiency and offers practical guidance for managing quality in imperfect production environments.

3. Problem Description and Model Development

3.1. Problem Description

It is supposed that a manufacturer specializing in imperfect production systems for customized products faces the challenge of establishing an efficient production and inspection framework to handle imperfections in the manufacturing process. In such production configuration, the system must rapidly assemble components on demand to meet customer specifications, while minimizing costs and ensuring product quality. However, the production system is imperfect and subject to deterioration, which can cause it to shift from an in-control state (producing mostly conforming items with low defect rates) to an out-of-control state (generating more defective items, such as those with cracks, abnormal joints, or component malfunctions). This deterioration is modeled using a Zero-Inflated Non-Homogeneous Poisson Process, as historical data often shows inflated zeros (periods with no deterioration events), possibly due to robust periods in Industry 4.0-enabled systems. Therefore, the manufacturer faces several key challenges:

System Deterioration and State Uncertainty: The production system deteriorates over time, with the rate influenced by factors such as machine wear, employee efficiency, and environmental conditions. The probability of being out-of-control increases with the production run length , leading to higher defect rates () and costs. Historical data may exhibit zero-inflation, where the system remains defect-free with probability , complicating traditional modeling approaches.

(1) Quality Inspection Trade-offs: Implementing a full inspection is time-consuming and costly, whereas sampling carries the risk of accepting defective lots or rejecting conforming ones, leading to correction () or warranty () expenses. Therefore, the manufacturer requires an optimal sampling plan to determine the number of items to inspect () without disrupting production schedules.

(2) Cost Minimization Under Multiple Factors: The total cost includes production (fixed and variable, based on learning), inspection ( and ), inventory holding (), and warranty based on product hazard rates. The employee learning rate () affects efficiency, while market demand () and production rate () influence inventory mismatches. Balancing these factors, while accounting for product deterioration, presents a complex challenge.

(3) Parameter Estimation from Historical Data: Deterioration parameters (, , ) must be estimated from potentially zero-inflated historical data, requiring advanced methods such as the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to handle zero-inflation.

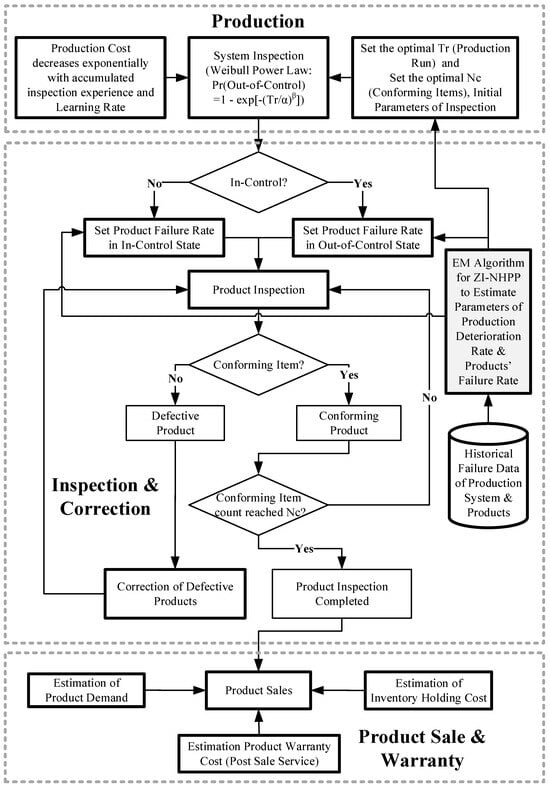

For better comprehension, the framework of the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Production System Operation with Inspection, Correction, and Warranty Framework.

Figure 1 illustrates the integrated operational framework for an imperfect production system, incorporating production, inspection, correction, and warranty processes to minimize total costs under zero-inflated non-homogeneous Poisson deterioration. This diagram provides a visual representation of the system’s workflow, highlighting key decision points, state transitions, and cost implications, while emphasizing the role of the ZI-NHPP model in estimating deterioration parameters from historical data.

The framework begins at the top with “production cost” considerations, which decrease exponentially with accumulated inspection experience and employee learning rate. Production initiates by setting the optimal production run length , during which the system may remain in-control or shift to out-of-control based on the ZI-NHPP intensity function . Parameters such as and are estimated via the EM algorithm from historical failure data of production systems and products, accounting for zero-inflation .

A central decision node checks if the system is in control. If it is in control, the product failure rate is set low (using Weibull parameters (, ); if out-of-control, it is set high (, ). This leads to “product inspection”, where negative binomial sampling is employed to inspect items until the optimal number of conforming items is reached. Items are classified as conforming or defective: defective items undergo correction, while conforming items proceed to product sales.

The lower section addresses post-production stages. Conforming items contribute to “inventory holding cost” estimation, based on mismatches between production output and demand. Sold products incur “warranty costs”, estimated using Weibull cumulative hazards over the warranty period , differentiated by system state: for in-control (low failure risk) and for out-of-control (high failure risk). Historical data informs these estimations, ensuring alignment with real-world deterioration patterns.

This framework underscores the interplay between quality inspection and production planning, optimizing and to minimize the expected total cost , which includes production, inspection and correction, inventory holding, and warranty expenses. By integrating ZI-NHPP for robust deterioration modeling, the approach enhances cost-efficiency in production systems.

3.2. Development of the Mathematical Model

To address these challenges, the manufacturer aims to develop a cost-minimizing inspection plan that optimizes , minimizes the expected total cost (E[TC]), and adapts to mass customization needs. These notations or symbols used are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations or Symbols.

The expected total cost formula for the optimal inspection plan in imperfect production systems using a ZI-NHPP model incorporates various cost components. These costs reflect the integration of production, inspection, inventory management, and warranty considerations. Below is a detailed explanation of each cost component in the formula:

(1) Production Cost: This component represents the total cost incurred during the production process and can be expressed as follows:

where represents the fixed expenditure on production equipment during a period, reflecting the capital investment required to operate the manufacturing system. The variable cost is modeled as a summation from to (quantity demanded), where is the manufacturing cost of the first unit. The term accounts for the learning rate , a decreasing function that captures improvements in employee efficiency over time, derived from the learning curve effect. The exponential factor incorporates the contraction constant () and the optimal number of conforming items inspected (), reflecting reduced manufacturing costs as more conforming items are identified due to enhanced efficiency. This term ensures that production costs decrease with improved inspection outcomes.

Generally, the study assumes a consistent learning rate , which may vary in practice due to worker turnover or skill disparities, potentially affecting cost estimates in dynamic production environments. governs the pace of deterioration and its influence on production cost is analytically characterized in Lemma 1. A higher amplifies cost savings from inspection, but its value should be calibrated against empirical data to avoid over-optimism.

Lemma 1.

Monotonicity and Convexity of Production Cost.

- Statement: The production cost is strictly decreasing and convex in for , and . Furthermore, is strictly increasing and convex in .

Proof of Lemma 1.

Please refer to Appendix A.

- The parameter governs the rate at which the system transitions to reduced productivity due to deterioration. Higher accelerates performance degradation, driving costs upward, and its convexity implies that deterioration mitigation measures (e.g., preventive maintenance or higher sampling rates) become increasingly valuable when deterioration becomes severe. □

(2) Inspection and Correction Cost: This cost covers the expenses associated with inspecting the production system and correcting deviations, and it can be expressed as follows:

where represents the fixed cost of inspecting the system after each production run to assess its status [1]. The variable component includes (correction cost) and (product inspection cost per item, where is the expected number of items inspected due to the defective rate ). The probability of entering the out-of-control state is , in accordance with the ZI-NHPP deterioration model, where is the latent defect-free probability based on the Weibull deterioration model’s cumulative intensity. This probability indicates the likelihood of needing correction actions. In addition, please note that is a quality proportion parameter, not a complementary probability to , and the two should not sum to 1.

This component highlights a critical trade-off in imperfect production systems: full inspection is resource-intensive, whereas sampling risks accepting defective lots, incurring and (warranty) costs. The out-of-control probability, driven by and , is sensitive to production duration; longer increases this probability, necessitating more frequent inspections. The defect rate further complicates this balance—higher raises the expected number of items inspected, amplifying costs unless offset by robust design.

Lemma 2.

Expectation and Probability in Inspection and Correction Cost.

- Statement: The inspection and correction cost has expected number of inspections under negative binomial sampling, and is the valid probability of needing correction, bounded in .

Proof of Lemma 2.

Please refer to Appendix A. □

(3) Inventory Holding Cost: This component quantifies the cost of holding inventory during the production cycle, and it can be expressed as follows:

is the inventory holding cost per unit time, applied to the squared difference between the total products produced (, where is the production rate) and the demand (), divided by twice the demand rate (). The quadratic term accounts for overproduction or underproduction relative to demand, amplifying costs when production exceeds or falls short of .

In the study, where demand () is often customized and variable, this cost component underscores the challenge of synchronizing production with customer orders under tight schedules. The quadratic nature ensures that small mismatches are tolerable, but large deviations (e.g., overproduction due to extended ) escalate costs rapidly. Sensitivity to and is significant; increasing to meet demand may raise the related costs, creating a trade-off with quality costs.

Lemma 3.

Convexity of Inventory Holding Cost.

Statement: The inventory holding cost is convex in and minimized at (perfect production-demand match).

Proof of Lemma 3.

Please refer to Appendix A.

- This result highlights that inventory cost is driven not merely by time or production scale individually, but by the extent to which production output matches demand over a cycle. The convex structure implies that deviations from the balance point become increasingly costly, so small mismatches are inexpensive while large overproduction accumulates inventory rapidly. When combined with deterioration effects, longer production runs may reduce setup frequency but push the system further from the demand-matching point, reinforcing the trade-off between holding cost and quality-related risks. □

(4) Warranty Cost: This cost accounts for warranty-related expenses due to product failures during the warranty period .

is the warranty cost per item. The warranty cost is divided into two parts: (i) In-Control Warranty Cost represents the expected failures of products produced in the in-control state, with hazard rate . The term is the probability of the system remaining in-control. (ii) Out-of-Control Warranty Cost covers failures of unchecked, conforming, and reworked items from the out-of-control state, with hazard rate (where is the proportion of conforming items from the in-control state, and is the out-of-control probability.

Warranty costs are a major concern in production systems, where product customization increases failure risks if defects are undetected. The use of Weibull distributions (, for low hazard; , for high) reflects realistic failure patterns, with > indicating accelerated degradation in out-of-control states. Inspection () reduces warranty claims by reworking defective items, but the effectiveness depends on (conforming proportion) and . The zero-inflation parameter also plays a role; higher (robust design) reduces baseline warranty costs, offering a strategic lever for manufacturers.

Lemma 4.

Expectation of Failures in Warranty Cost.

- Statement: The warranty cost uses Weibull expected failures for states (in-control, low hazard) and (out-of-control, high hazard), weighted by system states, and is non-decreasing in . (: The out-of-control probability, : The in-control probability).

Proof of Lemma 4.

Please refer to Appendix A.

- The warranty cost increases as the system becomes more likely to be out-of-control during production, because items produced in that regime fail at a much higher hazard rate. Thus, even when defects are not immediately observable, inadequate inspection increases long-run failure liability, linking inspection decisions to post-sale cost exposure. □

(5) Total Expected Cost: According to the above mentioned, the total expected total cost is as follows:

The total cost integrates these components, reflecting a comprehensive approach to cost management in imperfect production systems. The ZI-NHPP framework addresses data inflation, a limitation in prior models (e.g., [1]), while the integrated optimization of (number of conforming items inspected) and (production run length) balances quality control and cost efficiency. The expanded discussion highlights parameter sensitivities (e.g., , , ) and practical trade-offs, such as the interplay between inventory holding costs and production scheduling. For manufacturers, this suggests a dual strategy: invest in robust design to increase and implement adaptive inspection and production planning to optimize both and based on defective rates and demand data.

3.3. ZI-NHPP Framework for Estimating the Parameters of a Production System’s Deterioration

To accurately model the deterioration process in imperfect production systems, we adopt the ZI-NHPP framework. This model is particularly suited for historical datasets exhibiting excess zeros—periods where no deterioration events occur—due to inherent system robustness or Industry 4.0-enabled preventive measures (-[6,7]). Traditional NHPP assume a continuous intensity function but fail to account for structural zeros, leading to biased parameter estimates ([8]). The ZI-NHPP addresses this by incorporating a mixture distribution: with probability (the zero-inflation parameter), the system remains defect-free (no events), and with probability , it follows an NHPP with a power-law intensity function (where is the scale parameter and indicates accelerating deterioration, reflecting wear-out in production systems).

The cumulative intensity function is given by , and the probability of no events occurring up to time in the susceptible subpopulation is . Therefore, the overall probability of zero events up to time (the production run length) is , while the probability of being out of control is . This formulation captures the heterogeneous degradation in a production system, where deterioration events (e.g., a machine shifting to an out-of-control state) may be rare but increase over time due to factors such as machine wear, employee efficiency, or environmental conditions.

Parameters , , and must be estimated from historical data, which often includes multiple systems or runs with varying observation periods. We employ the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm, an iterative method well-suited for handling latent variables in zero-inflated models. The EM algorithm treats the zero-inflation as arising from unobserved binary indicators: for each observation , let if the system is susceptible (follows an NHPP) and if it is immune (experiencing zero events). The observed data consist of event counts over intervals , where may originate from either subpopulation.

Assume independent systems, each observed over time . The likelihood for the ZI-NHPP is:

where , is the Dirac delta, and .

Complete-Data Likelihood:

Introduce latent . The complete data likelihood is:

Taking the log as follows:

EM Algorithm Steps:

The EM algorithm iterates between E-step (computing expected ) and M-step (maximizing ) until convergence (e.g., change in ).

E-step: Compute the responsibility (posterior expectation of ):

For , this simplifies to ; for .

M-step: Update parameters by maximizing the expected complete log-likelihood:

For and , solve the system for susceptible observations ():

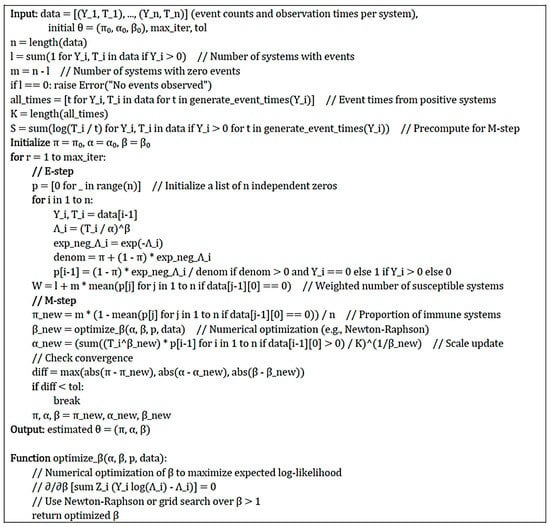

This requires numerical optimization methods (e.g., Newton-Raphson), as closed-form solutions are unavailable for the power-law NHPP. The reparameterization aligns with the Weibull forms used in the cost model (e.g., hazard rates), ensuring consistency. Figure 2 presents the pseudocode for the EM algorithm used to estimate the parameters of a production system’s deterioration.

Figure 2.

Pseudo-code of the EM Algorithm for Estimating the Parameters of a Production System’s Deterioration.

The above pseudo-code presented outlines an iterative EM algorithm designed to estimate the parameters of a Zero-Inflated NonHomogeneous Poisson Process model, tailored to characterize the deterioration of production systems. This algorithm addresses the challenge of historical data exhibiting excess zeros-periods with no deterioration events-by integrating a zero-inflation parameter with a powerlaw intensity function and cumulative intensity . The algorithm begins by accepting input data as a list of tuples () for systems, where represents the number of deterioration events and is the observation time for system . Initial parameter values , a maximum number of iterations (max_iter), and a convergence tolerance (tol) are also provided. The code first computes (number of systems with events) and (number of zeroevent systems), concatenating event times from positive systems into all_times to determine (total event count). If , an error is raised due to insufficient data. A precomputed statistic , the sum of over event times, aids in parameter updates.

The EM algorithm iterates up to max_iter times or until convergence. In the E-step, a list of length is initialized to store the responsibility , the expected value of the latent indicator (1 if susceptible, 0 if immune). For each system , the cumulative intensity and its exponential are calculated. The responsibility is set to for (adjusted for zero division), 1 for (certainly susceptible), and 0 as a fallback. This step estimates the probability of each system belonging to the susceptible subpopulation. The weighted number of susceptible systems is then computed as .

In the M-step, the parameters are updated as follows: is the proportion of immune systems, calculated as ; is optimized numerically (e.g., via Newton-Raphson) to maximize the expected log-likelihood; and is derived from the relationship between observed intensities and , approximated as . Convergence is checked by comparing the maximum absolute difference between old and new parameters against tol; if satisfied, the loop terminates, outputting the final .

Moreover, it should be noted that the estimates of and in the M-step do not have closed-form solutions due to the mixture structure of the ZI-NHPP likelihood. Therefore, we maximize the expected complete-data log-likelihood numerically using a Newton–Raphson procedure with line search. If the Hessian becomes unstable, a quasi-Newton BFGS routine is used as a fallback. Initial values are obtained from standard NHPP estimation to ensure convergence. This guarantees monotonic likelihood improvement during iterations.

This implementation is robust for production systems’ deterioration data, handling per-system variability in and , and incorporates safeguards against edge cases (e.g., no events). It leverages the EM algorithm’s ability to manage latent variables, providing a practical tool for estimating parameters from zero-inflated datasets. Likewise, the estimation of the scale and shape parameters for product failures in both in-control and out-of-control states can be effectively implemented using the same algorithm in practice.

The programs related to the algorithms and mathematical models are available in the Supplementary Materials of the study.

4. Application and Numerical Analysis

4.1. Numerical Example

As a toy manufacturer specializing in electronic toys under an imperfect production system, we encounter persistent challenges in ensuring product quality while controlling costs amid system deterioration. Our production line for items such as interactive robots and remote-controlled vehicles often shifts from an in-control state to an out-of-control state, resulting in defects like faulty circuits and assembly errors. These issues increase rework, warranty claims, and inventory holding costs. Historical data from our operations reveal significant variability, including extended periods without deterioration events-possibly due to robust component designs or preventive maintenance—that traditional models fail to capture accurately. To address this, we have implemented a Zero-Inflated Non-Homogeneous Poisson Process framework, employing the EM algorithm to estimate degradation parameters from our historical production logs.

Table 2 summarizes the key parameter values used in our case study, derived from empirical data and aligned with our electronic toy manufacturing context. For the production system’s degradation, the scale parameter and shape parameter indicate a moderate degradation onset with accelerating failure rates, while the zero-inflation parameter suggests a 30% probability of defect-free runs, underscoring design robustness. The defect rate in the out-of-control state is 0.3, reflecting common issues like component wear. Inspection-related costs include system inspection at , correction at , and per-item inspection at . Product failure rates are modeled with Weibull parameters: in-control state () for lower hazards, and out-of-control state () for higher risks. Production parameters encompass a rate of units, contraction constant , equipment expenditure , first-unit manufacturing cost , employee learning rate , and demanded quantity . Additional costs include inventory holding at per unit time and maintenance at per item, with a conforming proportion from incontrol state and warranty term years.

Table 2.

Parameter Values for the Case.

These parameters provide a realistic basis for optimizing our production run length () and the number of conforming items inspected (), aiming to balance quality assurance with cost efficiency. By leveraging this model, we seek to develop actionable strategies that reduce overall expenses-spanning production, inspection, correction, inventory, and warranty-while adapting to market demands for customizable electronic toys.

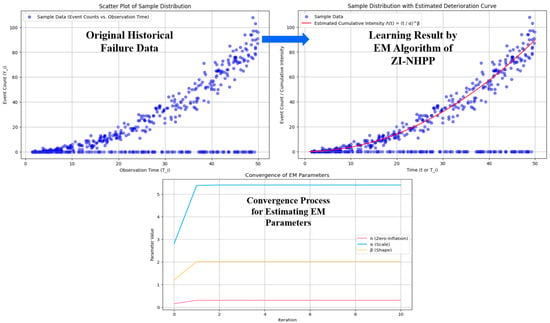

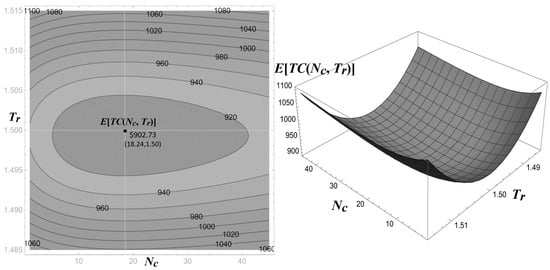

Using the EM algorithm on simulated historical data (n = 500), we estimated , , and , closely matching the true parameter values and demonstrating the algorithm’s reliability (see Figure 3). These estimates inform our optimization of the production run length () and the number of conforming items inspected (), aiming to balance quality assurance with cost efficiency. Numerical optimization of the expected total cost yields an optimal and months, resulting in a minimal expected total cost of approximately 902.73. Since must be an integer in practice, we round it down to 18, after which the expected total cost is 903.42. Note that the number of inspection items () can be deduced to be 26. Although a closed-form solution for minimizing is not available, numerical methods demonstrate the convexity of with respect to and , as shown in Figure 4. This configuration minimizes costs by limiting production run lengths to reduce deterioration risk while inspecting a sufficient number of items to detect defects early.

Figure 3.

The Process of Applying the EM algorithm to Estimate the Parameters of the ZI-NHPP Model.

Figure 4.

Contour and 3D Plot of Total Expected Cost () under Various Production Run () Lengths and Numbers of Conforming Items for Inspection ().

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

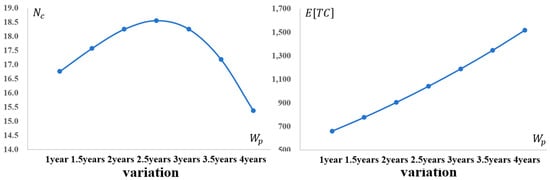

Figure 5 illustrates the sensitivity of the expected total cost and the optimal number of conforming items inspected () to variations in the warranty term (). As expected, extending increases due to greater exposure to product failures under Weibull hazard rates, particularly in the out-of-control state where failure rates accelerate. This analysis quantifies the cost implications, revealing that a 1-year extension from the baseline = 2 years elevates by approximately 15–20%, depending on the adjustment in . Such insights enable manufacturers to evaluate the financial trade-offs of offering longer warranties, balancing customer satisfaction against increased warranty expenses.

Figure 5.

Impact of Optimal Number of Conforming Items Inspected () and Total Expected Cost () as Warranty Term () Changes.

Notably, extending also induces non-monotonic and non-linear changes in the optimal . To mitigate the amplified warranty costs from prolonged coverage, the model adjusts inspection intensity; however, this adaptation is not straightforward. As shown in Figure 5, peaks at approximately 19 when = 2.5 years, indicating a heightened need for sampling to detect and correct defects early, thereby reducing long-term failure risks. However, beyond or below this threshold—whether increasing to 4 years or decreasing to 1 year— decreases, dropping to about 15 at = 4 years. This counterintuitive pattern arises because excessively long warranties shift the cost optimum toward shorter production runs and fewer inspections, prioritizing prevention through system robustness (e.g., higher ) over extensive sampling, while shorter warranties lessen the incentive for aggressive inspection.

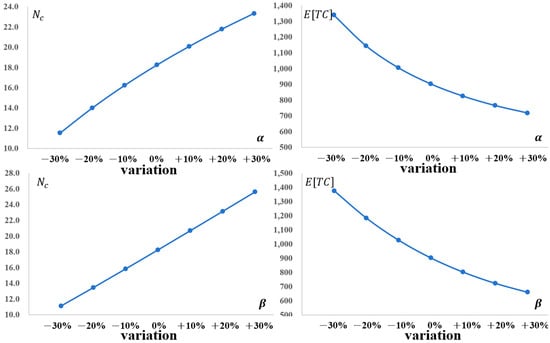

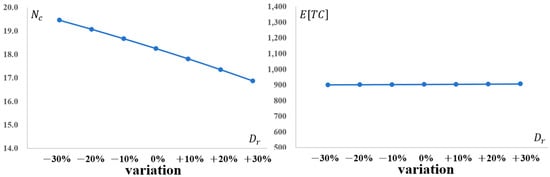

Figure 6 illustrates the sensitivity of the expected total cost and the optimal number of conforming items inspected () to variations in the scale () and shape () parameters of the production system degradation, adjusted by ±30% from baseline values ( = 5.3, = 2.0). Increasing to 6.89 (+30%) reduces by approximately 20% to around 805, reflecting enhanced system reliability due to a slower degradation onset, which lowers out-of-control transitions and associated costs. Similarly, elevating to 2.6 (+30%) decreases by about 25%, as the accelerated but more predictable deterioration pattern allows for better preventive measures.

Figure 6.

Impact of Optimal Number of Conforming Items Inspected () and Total Expected Cost () as Scale & Shape Parameters () Changes.

Concurrently, these parameter shifts necessitate adjustments in to verify the in-control state. At = 6.89, rises to 23 (from baseline 18), requiring more inspections to confirm sustained reliability amid the extended scale. For = 2.6, increases to 26, as the sharper deterioration curve demands intensified sampling to detect shifts early. Reductions in and lower to 12 and 11, respectively, as the system is more prone to defects, shifting the focus from inspection to other cost mitigations. These non-linear responses highlight the model’s adaptability, guiding toy manufacturers to calibrate parameters for cost-efficient operations.

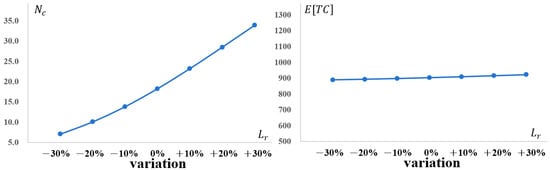

Figure 7 illustrates the sensitivity of the expected total cost and the optimal number of conforming items inspected () to variations in the employee learning rate (), adjusted by ±30% from the baseline value ( = 0.5). Increasing to 0.65 (+30%) improves production efficiency, thereby reducing production costs through accelerated learning curves; however, this requires more intensive inspection to maintain quality amid faster output, causing to rise to approximately 34. The offsetting effects of decreased production costs and increased inspection expenses result in minimal variation in , which remains stable around 900, fluctuating by only 2–3% across the range. While this cost-focused analysis indicates negligible changes in , it does not imply that increasing lacks benefits for manufacturers. Incorporating revenue perspectives reveals that improved learning rates enable higher production volumes and faster throughput, potentially generating additional product revenue—especially in high-demand assemble-to-order segments such as electronic toys. Therefore, strategies like investing in employee training to enhance remain advantageous overall, despite the balanced cost dynamics observed here.

Figure 7.

Impact of Optimal Number of Conforming Items Inspected () and Total Expected Cost () as Employee Learning Rate () Changes.

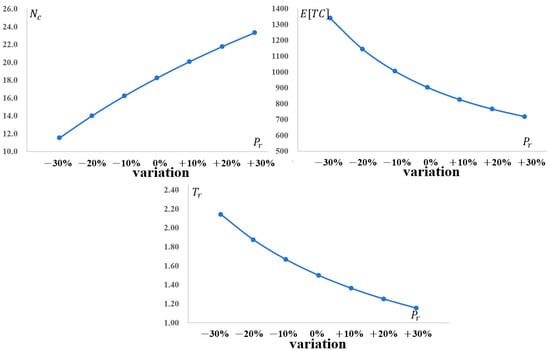

Figure 8 examines the sensitivity of the expected total cost , the optimal number of conforming items inspected (), and the optimal production run length () to variations in the production rate (), adjusted by ±30% from the baseline value ( = 800). Increasing to 1040 (+30%) markedly reduces by approximately 25% to 718, as higher throughput lowers per-unit production costs and enhances efficiency, with effects more pronounced than those observed with employee learning rate () adjustments. This escalation also boosts to 23, necessitating more inspections to ensure quality amid accelerated output, while shortening to 1.05 to mitigate deterioration risks during extended runs. Conversely, decreasing to 560 (−30%) elevates by 15% to 1028, reduces to 18, and extends to 2.1, reflecting diminished efficiency and prolonged cycles to meet demand. Unlike increases, which yield stable due to offsetting costs, enhancements deliver clearer cost reductions alongside contraction.

Figure 8.

Impact of Optimal Number of Conforming Items Inspected (), Total Expected Cost () and Optimal Production Run Length () as Production Rate () Changes.

Figure 9 presents a sensitivity analysis of the expected total cost, , the optimal number of conforming items inspected () during the current production run length (), in response to variations in the defect rate (), adjusted by ±30% from the baseline value ( = 0.3). The analysis reveals that changes in —increasing to 0.39 (+30%) or decreasing it to 0.21 (−30%) results in only minimal fluctuations in . This modest impact can be attributed to the relatively low baseline defect rate, where defect occurrences are already limited, thereby reducing the overall cost sensitivity to further adjustments.

Figure 9.

Impact of Optimal Number of Conforming Items Inspected () and Total Expected Cost () as Defect Rate () Changes.

Although the defect rate affects the expected number of nonconforming items, its impact on the total expected cost remains relatively modest. This is because influences primarily the inspection-, correction-, and warranty-related components, while production, deterioration, and holding costs constitute a substantial share of the total cost and are not directly driven by . Moreover, the optimal sampling effort adjusts endogenously as changes: higher defect rates reduce the required number of conforming samples for detection, whereas lower defect rates require increased sampling to maintain diagnostic confidence. These offsetting behavioral responses contribute to the relatively small variation in observed in Figure 9.

However, the effect on is more pronounced, particularly at higher levels. When increases to 0.39, decreases to approximately 17, compared to the baseline value of 18. This reduction occurs because, with a higher defect rate, the expected number of conforming items per sample diminishes under the same inspection effort. Consequently, fewer conforming items need to be inspected to determine whether the production system is in control or out of control, thereby optimizing resource allocation. These findings suggest that, for our electronic toy manufacturing process, adjustments in primarily influence the inspection strategy rather than the total cost, providing valuable insights for adaptive quality control in varying defect scenarios. Additionally, Table 3 provides detailed information related to Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, which are used to investigate the impacts of the relevant factors.

Table 3.

Impact of , , , , , and on , , and .

4.3. Managerial Insights

This subsection synthesizes the analytical findings from the numerical experiments and articulates their broader managerial implications. No new numerical results are introduced; instead, we integrate the patterns observed in previous analyses to clarify the strategic role of coordinated decisions regarding inspection intensity and production-run length. The focus is on how these decisions systematically shift in response to operational conditions, offering qualitative guidance on whether firms should prioritize inspection, shorten production cycles, or invest in reliability improvements. The summarized insights are presented as follows:

- (1)

- Warranty Period ()

Changes in the warranty duration affect both the total expected cost and the optimal inspection plan. Moderate extensions of the warranty period encourage the firm to increase inspection intensity, as detecting defects earlier becomes more economically valuable. However, when the warranty period becomes substantially long, continuously increasing inspection intensity becomes less cost-effective. In such cases, the preferred strategy shifts toward structural actions, such as shortening the production run or improving the inherent reliability of the system, rather than indefinitely expanding sampling efforts.

Insight: Warranty policies reshape not only the cost structure but also the intended role of inspection. Moderate warranties emphasize detection, whereas extended warranties prioritize prevention and robustness.

- (2)

- Degradation Characteristics (,): When the production system deteriorates more gradually or follows a predictable pattern, the economic necessity of confirming the in-control state increases. A healthier system incentivizes higher sampling intensity because verifying quality provides greater marginal benefits. Conversely, when deterioration accelerates or becomes more erratic, simply increasing inspection frequency becomes less effective; the optimal strategy shifts toward more frequent production cycles or equipment improvements.

Insight: Reliable systems warrant more rigorous verification, whereas fragile systems require structural modifications instead of expanded inspections.

- (3)

- Employee Learning Rate (): Improvements in learning rates enhance productivity and reduce production-related cost components; however, this does not directly lead to proportional reductions in total expected costs. This is because increased productivity typically necessitates higher sampling intensity to ensure that the greater output maintains the same level of quality assurance.

Insight: Learning enhances throughput and operational efficiency but yields limited cost savings unless accompanied by appropriate inspection adjustments.

- (4)

- Production Rate (): Higher production capacity reduces per-unit operational costs and enhances the firm’s ability to implement shorter production cycles, thereby mitigating deterioration risks. With increased capacity, inspection intensity tends to rise because verifying a larger output becomes more valuable. Conversely, at lower production rates, longer production cycles may be necessary to meet demand, increasing exposure to deterioration and making inspection a secondary rather than a primary control mechanism.

Insight: Capacity expansion enhances the effectiveness of short-term, high-verification strategies, while capacity constraints shift the focus toward longer-term operations and more cautious inspection.

- (5)

- Defect Rate (): Variations in defect probability have a limited impact on the total expected cost when the baseline defect rate is already moderate. However, they significantly influence inspection strategies: a higher likelihood of defects reduces the number of conforming samples required to infer the system state, as poor-quality signals become more apparent.

Insight: Even when costs are insensitive to defect rates, inspection policies must adapt to the information patterns in the data, not merely to cost outcomes.

- (6)

- Integrated Managerial Implications: Across all parameter variations, a consistent pattern emerges. Production run length and inspection intensity are interconnected strategic levers rather than independent decisions. Policy shifts (e.g., warranty length, capacity, maintenance investment) alter the role of inspection—sometimes serving as the primary tool for verification, and other times acting as a secondary measure to prevention or production adjustments. Zero-inflation modeling prevents the overestimation of deterioration risks, thereby avoiding overly conservative inspection plans that traditional NHPP models might generate. The convex nature of the cost landscape indicates a stable region of near-optimal solutions, facilitating robust decision-making even when parameter estimates are imperfect.

Overall Insight: The model not only determines the optimal sampling level and production interval but also offers a prescriptive framework that explains when firms should respond through inspection, operational redesign, or reliability investments.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive framework for integrating quality inspection and production run optimization in imperfect production systems, where deterioration is modeled using a zero-inflated non-homogeneous Poisson process (ZI-NHPP) with a power-law intensity function. By addressing the limitations of traditional models that overlook zero inflation in historical data—such as prolonged defect-free periods due to system robustness or advanced preventive measures—the proposed approach employs the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to accurately estimate key parameters, including the zero-inflation probability and degradation rates. This integration not only enhances the modeling of heterogeneous deterioration but also jointly optimizes the production run length and the number of conforming items inspected, minimizing the expected total cost encompassing production, inspection, correction, inventory holding, and warranty expenses. The framework’s emphasis on Weibull hazard rates for product failures, differentiated between in-control and out-of-control states, further refines cost predictions by accounting for accelerated failure risks under degraded conditions. Ultimately, this work bridges critical gaps in the literature, offering a robust tool for cost-efficient quality management in dynamic manufacturing environments.

In the basic model development, the problem is framed around a manufacturer facing challenges in balancing the rapid assembly of customized products with imperfections arising from system deterioration. The production system operates in an in-control state, yielding mostly conforming items with low defect rates, but gradually shifts to an out-of-control state over time, increasing defects such as cracks or malfunctions. This transition is captured by the ZI-NHPP, which incorporates a zero-inflation parameter to model scenarios. Key trade-offs are highlighted, including the time and cost of full inspections versus the risks of sampling errors leading to unwarranted corrections or warranty claims. The model integrates multiple cost components: fixed and variable production costs influenced by employee learning rates, inspection and correction expenses, inventory holding costs tied to mismatches between production rates and market demand, and warranty costs based on product hazard rates. Parameter estimation from historical data is achieved via the EM algorithm, which handles zero-inflated observations by iteratively maximizing the likelihood, ensuring reliable fits for degradation parameters. The optimization seeks to determine the ideal production run length, which heightens out-of-control probabilities and defect rates if extended, and the number of conforming items to inspect, striking a balance to minimize overall expenses while incorporating factors like employee efficiency and demand variability. The flowchart illustrates this process, from system inspection under Weibull power-law probabilities to product sales and warranty estimation, underscoring the interconnected nature of production, quality control, and post-sale services.

The application and numerical analysis demonstrate the framework’s practical utility through a case study of a toy manufacturer producing electronic items. Historical production log data, characterized by significant zero inflation due to periods without defects, are processed using the EM algorithm. This approach yields parameter estimates that closely align with underlying patterns, confirming the method’s reliability in handling zero-inflated data. Numerical optimization of the expected total cost function reveals a convex surface with respect to production run length and the number of conforming items inspected. This enables the identification of minima that effectively reduce deterioration risks while ensuring sufficient sampling to detect issues early. The resulting configuration limits extended runs to prevent out-of-control shifts and adjusts inspection intensity to maintain quality without incurring excessive costs.

Sensitivity studies further validate the model’s robustness by examining responses to variations in key parameters. For example, extending the warranty period increases total costs due to prolonged exposure to product failures under Weibull hazard conditions, particularly in out-of-control states. This leads to non-monotonic adjustments in the optimal number of inspected items—initially increasing to enhance early defect detection but decreasing beyond certain thresholds as the focus shifts toward system-level prevention. Changes in degradation parameters, such as scale and shape, indicate that improved system reliability (characterized by slower onset or more predictable degradation patterns) reduces costs and requires more inspections to confirm sustained performance. Conversely, reductions in reliability increase vulnerability and redirect efforts toward alternative mitigation strategies. Variations in the employee learning rate result in minimal cost fluctuations due to offsetting effects between improved production efficiency and increased inspection demands; however, they highlight broader benefits such as higher throughput and potential revenue gains in high-demand segments. Adjustments in production rate demonstrate clearer cost reductions with increases, accompanied by shorter production runs and intensified inspections to manage accelerated output, whereas decreases prolong production cycles and elevate expenses. Finally, changes in the defect rate have modest cost impacts given low baseline levels but more pronounced effects on inspection numbers, with higher defect rates reducing the number of conforming samples per inspection effort and prompting corresponding strategic shifts.

From a managerial perspective, these insights underscore the value of adopting advanced stochastic models like ZI-NHPP in imperfect production environments to avoid overestimating risks from unaccounted zero-inflation, leading to more precise resource allocation and reduced unnecessary interventions. Manufacturers can utilize the integrated framework to dynamically adjust production and inspection strategies in response to market demands and employee capabilities, thereby enhancing cost efficiency without compromising quality. For instance, investing in training to improve learning rates not only stabilizes costs but also supports scalability in customized production. Warranty policies should be carefully calibrated, as extensions can encourage adaptive inspections but may prioritize preventive robustness over sampling in extreme cases, balancing customer trust with financial exposure.

The proposed model provides a planning-level framework for linking deterioration, inspection, and production run length decisions. However, several assumptions limit its scope. First, deterioration is modeled as a two-regime process; systems exhibiting progressive multi-stage wear may require a more granular reliability model. Second, the ZI-NHPP parameters are calibrated from historical failure data and may not remain stable across different operating conditions, requiring periodic re-estimation. Third, cost parameters such as rework, inspection, and warranty costs are assumed to be stationary and do not reflect dynamic contract structures or learning-based cost reduction. Finally, the optimization is static-cycle-based rather than real-time adaptive; integrating state-dependent decision-making or reinforcement learning approaches would be a natural extension.

Future research could extend this model by incorporating Bayesian analysis into parameter estimation, allowing the framework to be applied even in scenarios with limited or no historical data. This approach leverages prior distributions and updates posterior beliefs based on sparse observations, thereby enhancing robustness in data-scarce environments. Additionally, integrating uncertain demand factors, such as stochastic or probabilistic demand models, would broaden the practical applicability of the study to volatile market conditions where demand fluctuations impact inventory and production planning. By addressing these avenues, the framework can evolve to meet emerging challenges, ultimately contributing to more resilient and efficient production systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math13243901/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; data curation, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; formal analysis, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; funding acquisition, M.-N.C.; investigation, C.-C.F.; methodology, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; project administration, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; resources, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F.; supervision, M.-N.C.; writing—review and editing, M.-N.C. and C.-C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation and the Guangdong Soft Science Foundation, China [grant number 2024A0505050043].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Lemma A1.

Monotonicity and Convexity of Production Cost.

Proof of Lemma A1.

Let (since implies cost reduction via learning). The variable part is . Then . Differentiate w.r.t. : , proving strict decrease (efficiency gains from more conforming inspections reduce costs). Second derivative: , proving convexity (diminishing marginal returns in efficiency). For large , approximate (valid for ), preserving convexity.

- In addition, holding fixed: , so increases as deterioration accelerates, consistent with the interpretation that higher leads to faster efficiency loss. Second derivative: , implying convexity in —the marginal cost of deterioration grows faster as deterioration intensifies. □

Lemma A2.

Expectationand Probability in Inspection and Correction Cost.

Proof of Lemma A2.

Under negative binomial distribution, inspect until conforming items are found, with success probability (conforming rate in out-of-control state). The number of trials , so by the mean of a negative binomial (sum of geometrics). For (The out-of-control probability): The ZI-NHPP has mixture density: with probability , no events (defect-free); else, NHPP with first-event time , so . Thus, which is increasing in and (shape parameter), and since the exponential term is in . The cost is linear in and , hence non-decreasing in . □

Lemma A3.

Convexity of Inventory Holding Cost.

Proof of Lemma A3.

This is a quadratic penalty for mismatch between supply and demand , normalized over cycle time . Differentiate w.r.t. :

- Set to zero: , and second derivative proving convexity and global minimum at match point (zero cost). Integration with deterioration: Longer increases (from Lemma 2), creating a trade-off. □

Lemma A4.

Expectation of Failures in Warranty Cost.

Proof of Lemma A4.

For Weibull lifetime with hazard , the cumulative hazard over is , approximating expected failures per item (for low rates, via renewal theory). The full expression (from paper context) weights:

- (1)

- In-control (): All items at low hazard.

- (2)

- (2) Out-of-control: Uninspected mix low high; inspected reworked to high.

- Thus, , linear in (increasing since ). Differentiating w.r.t. yields a net increase due to reworked items. □

References

- Ho, J.W. Quality Inspection Plan for Imperfect Production System with Assembly Configuration. Processes 2020, 8, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.Q.; Zhou, B.H.; Li, L. Integrated Production, Quality Control and Condition-Based Maintenance for Imperfect Production Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 175, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.K.; Khara, B. Imperfect Production Inventory System Considering Effects of Production Reliability. In Fuzzy Optimization, Decision-Making and Operations Research: Theory and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, A.; Mishra, U.; Sarkar, B. A Sustainable Production–Inventory Model with Imperfect Quality under Preservation Technology and Quality Improvement Investment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M. Combined Class of Distributions with an Exponentiated Weibull Family for Reliability Application. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2023, 20, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Truong-Ba, H.; Cholette, M.E.; Will, G. Optimal Inspections and Maintenance Planning for Anti-Corrosion Coating Failure on Ships Using Non-Homogeneous Poisson Processes. Ocean Eng. 2021, 238, 109695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Zhang, D.; Li, G.; Hu, X. Reliability Evaluation of Distribution System Based on Time-Varying Failure Rate Model and Non-Homogeneous Poisson Process. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Energy Engineering and Power Systems (EEPS), Dali, China, 23–30 July 2023; pp. 593–597. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X. Condition-Based Maintenance Policy for Systems with a Non-Homogeneous Degradation Process. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 81800–81811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiß, S. An Ontology-Based Expert System for Quality Inspection Planning in the Construction Execution. In ECPPM 2022—eWork and eBusiness in Architecture, Engineering and Construction 2022; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Sett, B.K.; Sarkar, S. Optimal Production Run Time and Inspection Errors in an Imperfect Production System with Warranty. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2018, 14, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Navarro, K.; Acevedo-Chedid, J.; Árquez, G.M.; Florez, W.F.; Ospina-Mateus, H.; Sana, S.S.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E. An EPQ Inventory Model Considering an Imperfect Production System with Probabilistic Demand and Collaborative Approach. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2020, 17, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Tian, S.; Xu, J.; Deng, Y.; Cai, K. Optimal Production Lot-Sizing and Condition-Based Maintenance Policy Considering Imperfect Manufacturing Process and Inspection Errors. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 177, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Rout, C.; Goswami, A. A Model of an Integrated Supply Chain with Imperfect Production, Product Deterioration, and Quality Inspection Errors. Sādhanā 2024, 49, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmasnia, A.; Hajihosseini, Z.; Maleki, M.R. Joint Design of Control Chart, Production Cycle Length, and Maintenance Schedule for Imperfect Manufacturing Systems with Deteriorating Products under Stochastic Shift Size. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 21, 639–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalyov, M.Y.; Lukashevich, M.N.; Pesch, E. Cost-Minimizing Planning of Container Inspection and Repair in Multiple Facilities. OR Spectr. 2023, 45, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajej, Z.; Rezg, N.; Gharbi, A. Joint Production Preventive Maintenance and Dynamic Inspection for a Degrading Manufacturing System. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.C.; Hsu, C.C.; Liu, J.H. Bayesian Statistical Method Enhances the Decision-Making for Imperfect Preventive Maintenance with a Hybrid Competing Failure Mode. Axioms 2022, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.C.; Ma, L.; Kuo, W. Bayesian Analysis Enhances Sales and Warranty Strategies for Repairable Industrial Products by Considering Hybrid Deterioration Modes. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 72169–72188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Malek, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Dantan, J.Y.; Siadat, A.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. A Review on Optimisation of Part Quality Inspection Planning in a Multi-Stage Manufacturing System. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 4880–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genta, G.; Galetto, M.; Franceschini, F. Inspection Procedures in Manufacturing Processes: Recent Studies and Research Perspectives. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4767–4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Malek, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Siadat, A.; Dantan, J.Y. A Novel Model for the Integrated Planning of Part Quality Inspection and Preventive Maintenance in a Linear-Deteriorating Serial Multi-Stage Manufacturing System. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 96, 3633–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Li, C. Supplier Quality Management: Investment, Inspection, and Incentives. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrinaldi, F.; Pratama, H.B. Selecting the Best Quality Inspection Alternative Based on the Quality, Economic and Environmental Considerations. Qual. Manag. J. 2020, 28, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Al Rahman, M.; Mousavi, A. A Review and Analysis of Automatic Optical Inspection and Quality Monitoring Methods in Electronics Industry. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 183192–183271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, H.; Al-Omari, A.I.; Saha, M.; Mali, A. Time Truncated Life Tests for New Attribute Sampling Inspection Plan and Its Applications. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2022, 39, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, A.; Ratnayake, R.C. Machine Learning Approach for Risk-Based Inspection Screening Assessment. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 185, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolus, A.; Duffuaa, S. Determining Optimal Process Means in a Multi-Stage Production System with Inspection Errors in 100% Inspection. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2025, 22, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Park, C.; Lin, C.; Ouyang, L.; Ma, Y. Hybrid Reliability Analysis with Incomplete Interval Data Based on Adaptive Kriging. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 237, 109362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Yang, J.; Li, L. Reliability Analysis for Multi-Component Systems Considering Stochastic Dependency Based on Factor Analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 169, 108754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.F. Reliability Assessment for Partially Monitored Systems Based on Degradation Hidden Markov Models with Time-Varying Parameters. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2025, 74, 5272–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Fan, H.; Shao, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.; Ji, R. Remaining Useful Life Re-Prediction Methodology Based on Wiener Process: Subsea Christmas Tree System as a Case Study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahdy, E.E. Reliability Modelling of Heterogeneous Data by Using Different Competing Weibull Mixture Models. Adv. Appl. Stat. 2024, 91, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T. Generalized linear model based monitoring methods for high-yield processes. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2020, 36, 1570–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).