Abstract

This study presents an AI-based framework that unifies civil and mechanical engineering principles to optimize the structural performance of steel frameworks. Unlike traditional methods that analyze material behavior, load-bearing capacity, and dynamic response separately, the proposed model integrates these factors into a single hybrid feature space combining material properties, geometric descriptors, and load-response characteristics. A deep learning model enhanced with physics-informed reliability constraints is developed to predict both safety states and optimal design configurations. Using AISC steel datasets and experimental records, the framework achieves 99.91% accuracy in distinguishing safe from unsafe designs, with mean absolute errors below 0.05 and percentage errors under 2% for reliability and load-bearing predictions. The system also demonstrates high computational efficiency, achieving inference latency below 3 ms, which supports real-time deployment in design and monitoring environments. the proposed framework provides a scalable, interpretable, and code-compliant approach for optimizing steel structures, advancing data-driven reliability assessment in both civil and mechanical engineering.

Keywords:

AI-assisted structural optimization; physics-informed machine learning; structural reliability assessment; hybrid civil–mechanical framework; steel material properties MSC:

68T05; 68T20; 68T37

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has transformed numerous engineering domains, including structural analysis, design optimization, and reliability assessment [1]. In particular, the integration of data-driven models with domain-specific physical knowledge offers the potential to enhance predictive accuracy, improve computational efficiency, and reduce the risks associated with structural failures [2]. Civil and mechanical engineering systems are increasingly expected to satisfy stringent safety standards while also meeting demands for sustainability, cost-efficiency, and resilience [3]. Achieving this balance requires methodologies that not only leverage high-capacity neural networks but also ensure strict compliance with engineering codes and limit states [4].

Traditional computational models, such as finite element simulations and physics-only approaches, have provided reliable insights into structural behavior for decades [5]. These physics-based methods, however, are computationally expensive and lack scalability for real-time or large-scale monitoring tasks. Purely data-driven AI models, while efficient and adaptive, often lack physical interpretability and risk producing noncompliant predictions when applied to safety-critical systems [6]. This dichotomy highlights the necessity of hybrid approaches that combine the predictive power of deep learning with the interpretability and rigor of physics-informed modeling [7].

Recent research has begun to explore such hybrid paradigms, where physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and code-constrained optimization frameworks have demonstrated promising results in bridging the gap between data-driven learning and structural code compliance [8]. These approaches embed structural knowledge, such as load-bearing limits and material constraints, directly into the learning process, thereby reducing reliance on massive labeled datasets while ensuring compliance with established design standards [9]. Despite these advances, significant challenges remain in terms of scalability, generalization to diverse structural conditions, and the ability to adapt models dynamically under varying environmental and operational scenarios [10]. Moreover, existing studies have rarely addressed the verification of model performance under edge-computing constraints or validated the physical consistency of AI-driven predictions in accordance with engineering codes.

Another critical challenge arises in the optimization and reliability evaluation of AI-based structural models [11]. The performance of deep learning systems is highly sensitive to hyperparameter settings, requiring robust strategies for parameter tuning to achieve optimal outcomes [12]. While heuristic search methods such as grid search or random search are widely used, they are often inefficient in high-dimensional spaces [13]. Bayesian optimization has emerged as a powerful alternative, offering efficient exploration of parameter configurations and balancing accuracy with computational cost [14]. Yet, the integration of Bayesian optimization with physics-informed modeling remains underexplored in structural applications [15]. This gap underscores the need for frameworks capable of coupling intelligent hyperparameter tuning with physics-informed architectures to achieve both predictive robustness and engineering reliability.

The computational efficiency plays a pivotal role in enabling real-world deployment of AI-assisted structural systems [16]. Edge devices and cloud-based infrastructures that support smart cities and industrial applications impose constraints on latency, memory usage, and throughput. Therefore, any proposed framework must be designed to meet performance requirements in resource-constrained environments while maintaining reliability and compliance with engineering codes [17]. In this context, ensuring that the model remains both lightweight and interpretable during real-time operation becomes a crucial limitation that this study seeks to mitigate through quantization-aware optimization and edge-deployment validation.

The contributions of this paper are threefold:

- We propose a hybrid AI-assisted optimization framework that integrates a deep neural network with a physics-informed module, enforcing code-based structural constraints and limit state functions during training.

- We introduce a Bayesian hyperparameter optimization loop that adaptively tunes model configurations, enhancing predictive performance while minimizing computational cost.

- We evaluate the framework through comprehensive validation and reliability metrics, including statistical, regression, and computational efficiency measures, ensuring scalability and deployment feasibility for real-time structural monitoring systems.

Table 1 highlights the fundamental differences between purely physical, purely AI-based, and hybrid modeling paradigms in structural engineering. Physical models such as finite element methods provide high interpretability and compliance with design codes but are computationally demanding and less scalable. Pure AI models deliver rapid predictions and adaptability yet often lack physical consistency and may produce noncompliant outcomes. The proposed hybrid AI–physics framework combines the strengths of both by embedding code-based constraints and limit-state equations into the learning process.

Table 1.

Comparison between Physical, Pure AI, and Proposed Hybrid Modeling Approaches in Structural Analysis.

2. Literature Review

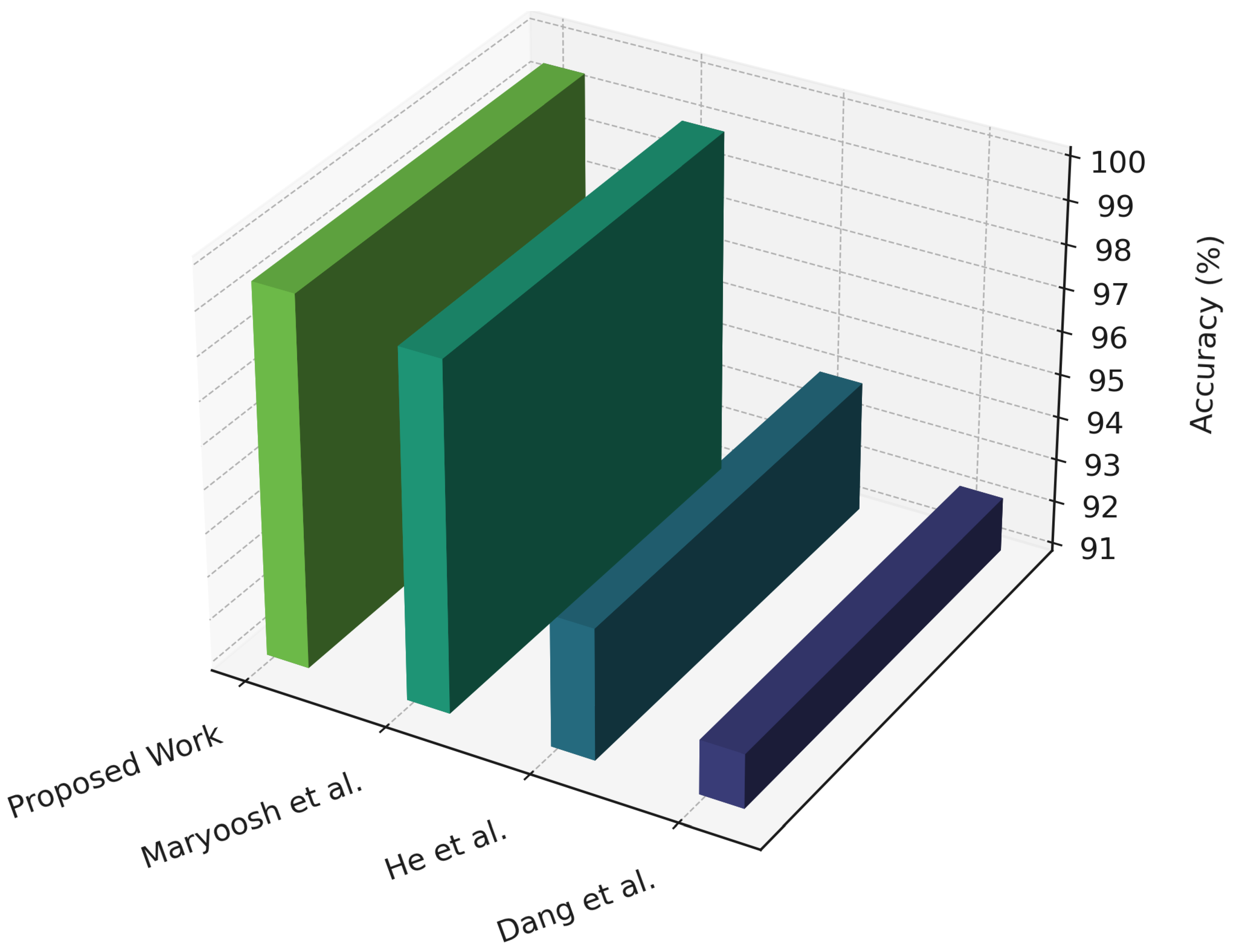

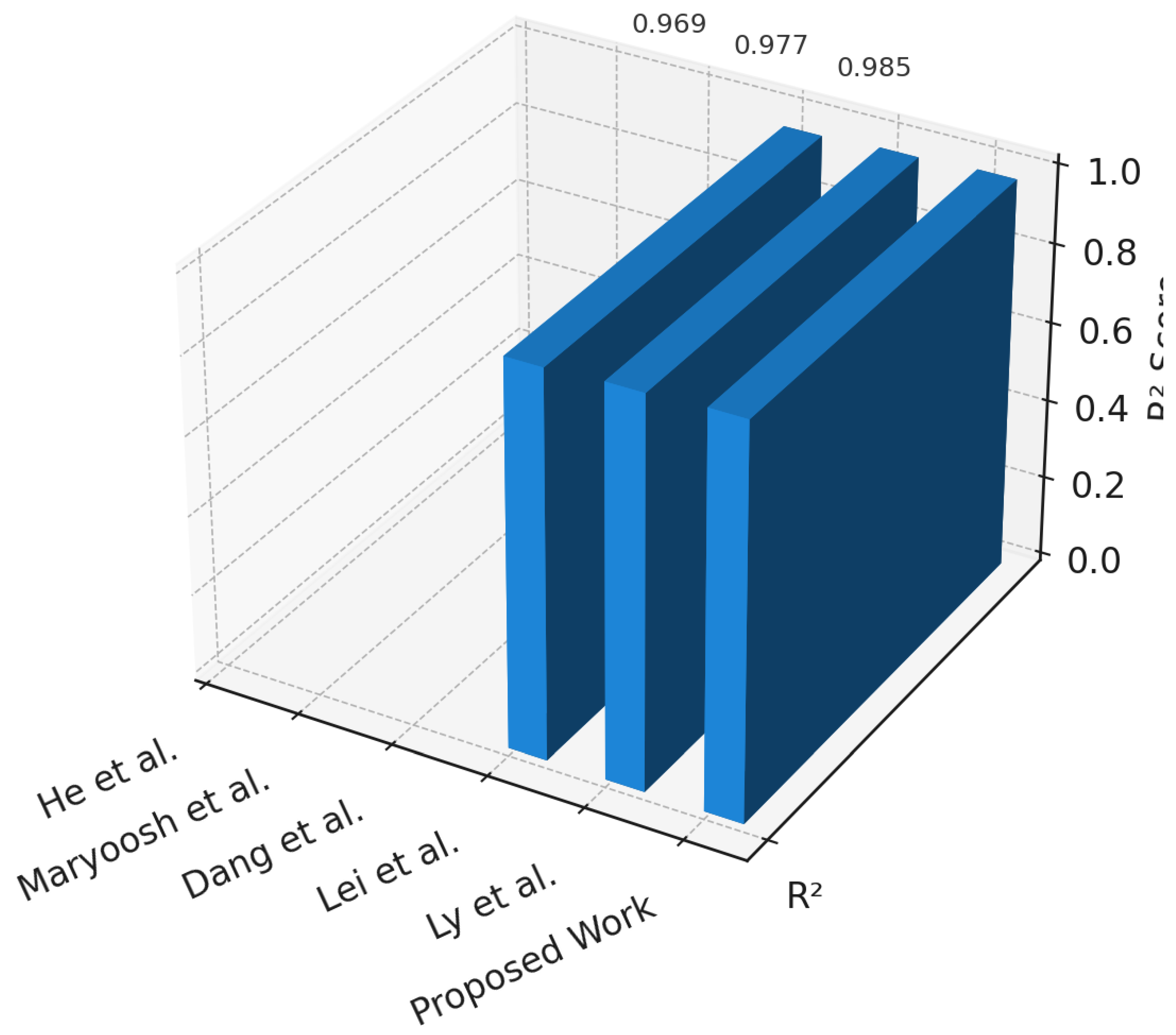

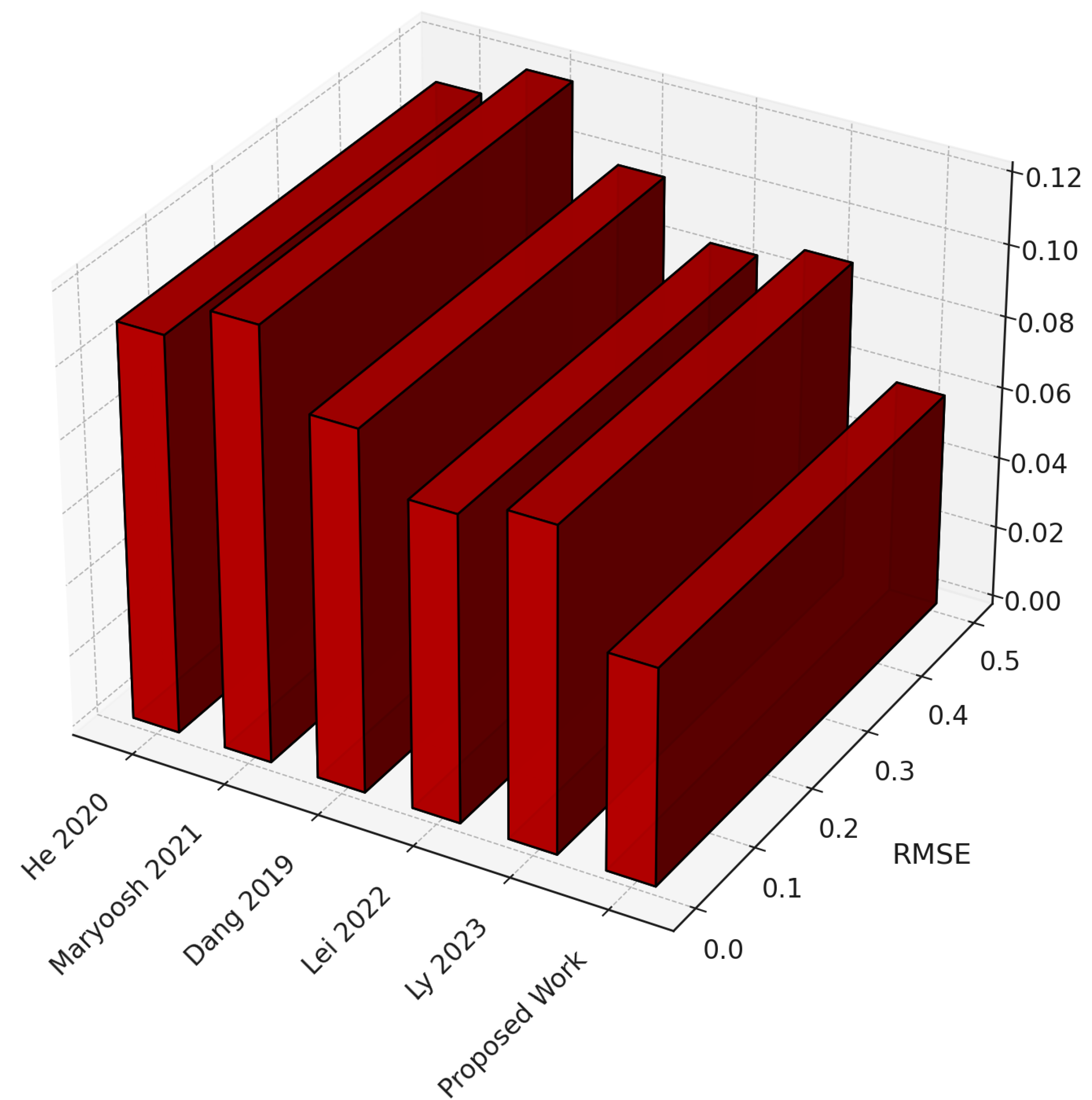

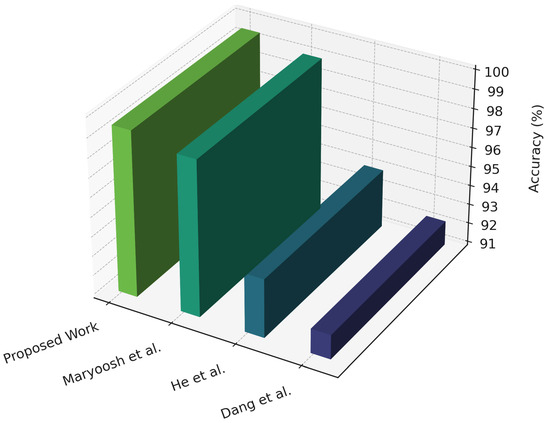

Lei et al. (2025) [22] proposed a hybrid machine learning model for predicting the shear strength of rock joints by integrating a multilayer perceptron (MLP) with the slime mold algorithm (SMA). Their SMA-MLP framework leveraged SMA’s global optimization capabilities to prevent local minima in MLP training, thereby improving predictive stability and accuracy. A dataset of 84 samples, incorporating joint roughness coefficient (JRC), normal stress, basic friction angle, Young’s modulus, and uniaxial compressive strength, was used for evaluation through five-fold cross-validation. The SMA-MLP model achieved good performance with , RMSE = 0.097 MPa, and MAE = 0.067 MPa on the test set, outperforming baseline models such as MLP, CatBoost, random forest, ridge regression, and backpropagation neural networks. Feature importance analysis identified normal stress as the dominant factor influencing shear strength, while Z-score normalization enhanced generalization performance. Despite these contributions, the study focused exclusively on shear strength prediction without addressing regression-based reliability measures such as probability of failure, reliability index, or ultimate capacity, and it did not incorporate physics-informed constraints or validate real deploy-time capability. Our work extends these insights by introducing physical constraint embedding to enforce equilibrium consistency and material compliance within the learning process, and by integrating edge deployment verification to ensure robustness and inference stability under quantized, real-time conditions. Specifically, the developed dual-head hybrid framework performs both classification and regression, embeds physics-informed penalties, employs Bayesian optimization, and validates quantized deployment for code-compliant structural reliability assessment.

He et al. (2022) [23] introduced a hybrid deep learning framework for structural damage identification that integrates ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD), Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), and convolutional neural networks (CNN). Their method first decomposed acceleration signals using EEMD to obtain time–frequency components, then applied PCC to select the most informative features, which were subsequently fed into a CNN for damage classification. Evaluations on a three-story benchmark structure under four damage conditions demonstrated that the proposed EEMD–PCC–CNN achieved 94.02% accuracy, with precision, recall, and F1-scores above 92%, outperforming classical approaches including CNN, SVM, KNN, RF, and XGBoost. The results confirmed the superiority of combining time–frequency decomposition with deep feature extraction for structural health monitoring. However, this study focused solely on classification for damage identification, without addressing regression-oriented reliability metrics such as probability of failure, reliability index, or ultimate capacity. It also did not incorporate physics-informed constraints or validate real-time deployment feasibility. Our work extends this direction by embedding physical constraint enforcement into the learning process to ensure equilibrium and material compliance during model optimization, and by implementing edge deployment verification for evaluating inference robustness and latency under quantized operational conditions. Specifically, the proposed dual-head deep hybrid learning framework performs both classification and regression under physics-informed penalty embedding, employs Bayesian hyperparameter optimization, and validates quantized edge deployment through constraint-aware training for code-compliant structural reliability assessment.

Maryoosh et al. (2025) [24] proposed a hybrid learning framework for bridge damage prediction that integrates handcrafted and deep learning techniques. Their approach combined local binary pattern (LBP) and bag-of-visual-words (BoVW) for feature extraction, Apriori-based association rule mining for feature selection and dimensionality reduction, and MobileNetV3-Large as the final classifier. Experiments on multiple benchmark datasets, including DIMEC-Crack and Bridge Concrete Damage (BCD), with 10-fold cross-validation achieved classification accuracies ranging from 98.27% to 100%, with precision, recall, and F1-scores near 99% and error rates below 1.73%. The framework demonstrated robustness and outperformed conventional CNNs and transfer learning models such as VGG, ResNet, and Inception. However, this work was limited to crack classification and did not address regression-oriented reliability measures such as probability of failure, reliability index, or ultimate capacity. It also lacked physics-informed constraints and validation for real-time deployment on edge hardware. Our study extends these contributions by embedding physical constraint enforcement within the hybrid learning pipeline to ensure compliance with equilibrium and constitutive consistency, and by implementing edge deployment verification to evaluate inference robustness and latency on quantized embedded devices. Specifically, the proposed dual-head hybrid framework performs both classification and regression, integrates physics-informed penalties, applies Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning, and validates quantized deployment under edge conditions for code-compliant structural reliability analysis.

Dang et al. (2020) [25] developed a feature-fusion and hybrid deep learning framework for structural health monitoring (SHM) that integrates multiple signal processing techniques with deep neural networks. Their method extracted features from autoregressive (AR) models, discrete wavelet transform (DWT), and empirical mode decomposition (EMD), fusing them into three-dimensional tensors subsequently processed by a 1D-CNN–LSTM hybrid network. The CNN layers captured local temporal dependencies, while LSTM cells modeled long-term patterns in vibration responses. Case studies included experimental data from a three-story benchmark structure, a synthetic stayed-cable bridge (My Thuan), and real-world progressive damage tests on the Z24 bridge, where the approach achieved accuracies of 93.5% to 91% for damage detection and localization. Compared to 2D-CNNs operating on spectrograms, the framework maintained competitive accuracy with more than 50% lower computational and storage cost, and robustness was confirmed under 10% added white noise. However, this work was limited to damage detection and localization without addressing regression-oriented reliability measures such as probability of failure, reliability index, or load capacity, and did not embed physics-informed constraints or validate edge deployability. Our framework advances this direction by incorporating physical constraint embedding within the network’s loss structure to ensure equilibrium consistency and mechanical plausibility, and by performing edge deployment verification to assess quantized inference stability, latency, and robustness under real-time operational conditions. Specifically, the proposed dual-head hybrid framework performs both classification and regression, embeds physics-informed penalties, applies Bayesian hyperparameter optimization, and validates quantized deployment for code-compliant structural reliability assessment.

Ly et al. (2020) [26] presented computational hybrid machine learning models for predicting the ultimate shear capacity (USC) of steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) beams. Using a dataset of 463 experimental samples covering beam geometry, mixture composition, and fiber properties, they developed two hybrid approaches: a neural network optimized with a real-coded genetic algorithm (NN-RCGA) and one optimized with the firefly algorithm (NN-FFA). The NN-RCGA achieved superior accuracy () compared to NN-FFA () and traditional empirical equations (–), while reducing RMSE and MAE by over 70% in some cases. Sensitivity analysis identified web width, effective depth, and clear depth ratio as the most influential parameters in shear capacity prediction, and the framework enabled predictions in less than one second per beam. However, this study was limited to shear capacity estimation without addressing regression-based reliability measures such as probability of failure, reliability index, or ultimate capacity, and it lacked physics-informed penalties and real-time edge validation. Our framework advances this direction by embedding physical constraint enforcement directly into the loss formulation to ensure mechanical equilibrium and constitutive consistency, while introducing edge deployment verification to evaluate quantized inference stability and latency across embedded devices. Specifically, the proposed dual-head hybrid framework performs both classification and regression, incorporates physics-informed penalty embedding, employs Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning, and validates quantized deployment under edge hardware constraints for code-compliant structural reliability assessment.

3. Methodology

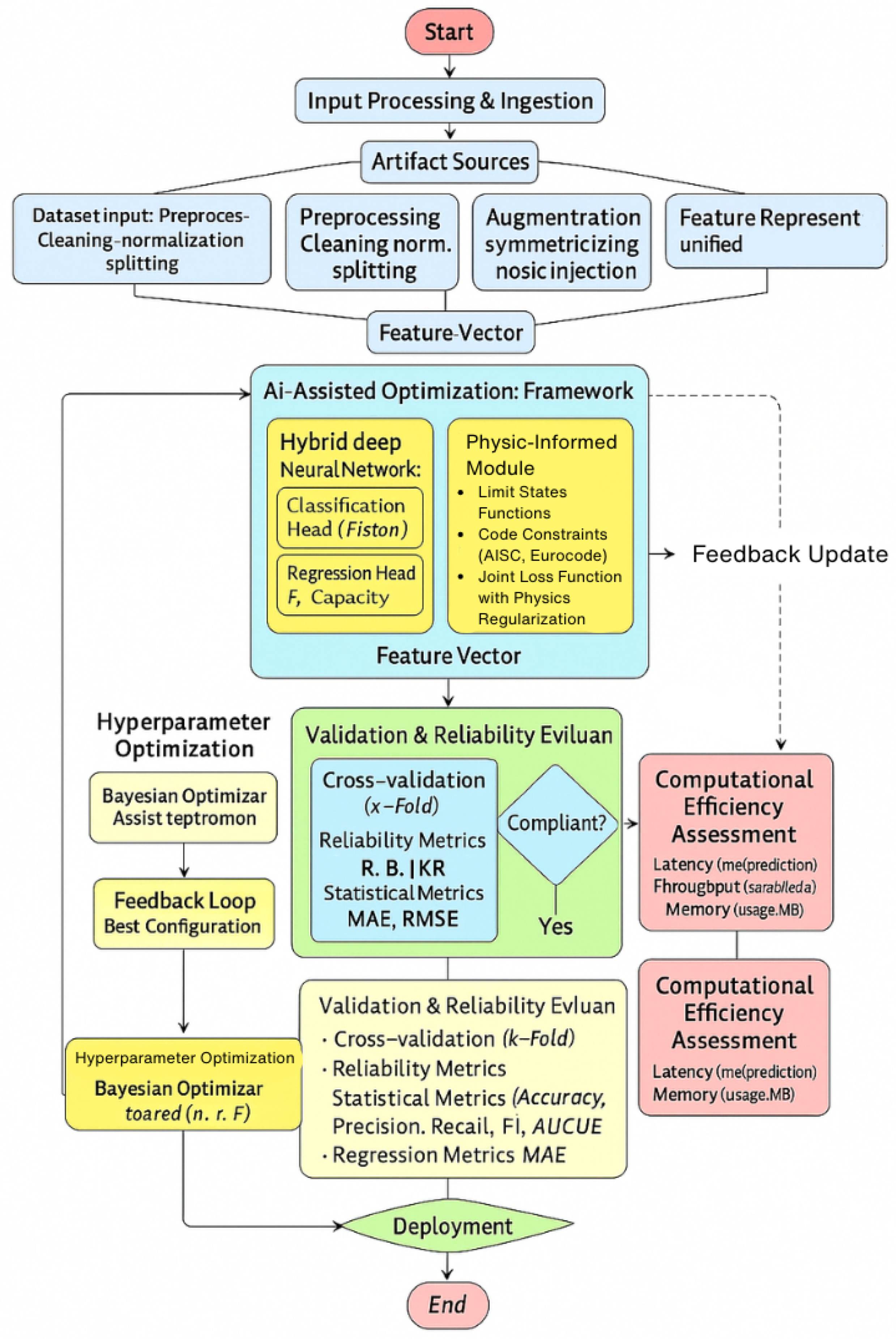

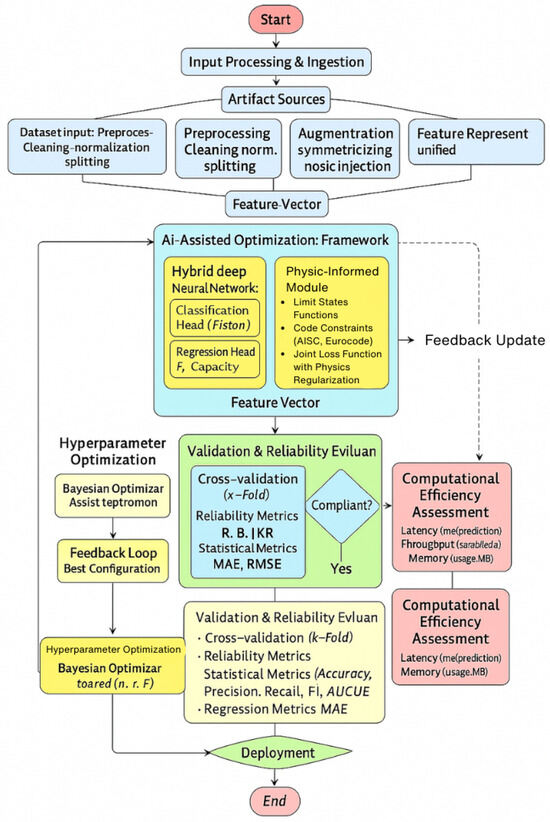

The methodology of this study is designed to integrate structural engineering knowledge with advanced AI-driven optimization to ensure both predictive accuracy and compliance with established civil and mechanical engineering codes. As illustrated in Figure 1, the process begins with input processing and ingestion, where dataset artifacts undergo preprocessing, normalization, augmentation, and noise injection to form robust and representative feature vectors. These feature vectors are then passed into the proposed AI-assisted optimization framework, which employs a hybrid deep neural network comprising a classification head for structural reliability states and a regression head for capacity prediction. A physics-informed module is embedded within the network to enforce structural limit state functions and code-based constraints (AISC, Eurocode), with the loss function jointly regularized by both data-driven and physics-based penalties. Hyperparameter tuning is guided by Bayesian Optimization in a feedback loop that continuously updates the model configuration for optimal performance. Validation and reliability evaluation are conducted through cross-validation and multiple statistical metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, AUC, MAE, RMSE), ensuring compliance with safety thresholds before deployment. Computational efficiency-measured in terms of latency, throughput, and memory usage-is assessed to guarantee the feasibility of real-time deployment in edge or cloud-assisted monitoring systems.

Figure 1.

Proposed Methodology.

3.1. Dataset Used

The utilized dataset in this study is the American Institute of Steel Construction Material Property Database (AISC-MPD, Version 16.0), officially released by the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC) and publicly accessible through the AISC online repository. This dataset provides experimentally measured mechanical properties of multiple steel grades commonly used in civil and mechanical engineering applications. It includes yield strength (), ultimate tensile strength (), modulus of elasticity (E), ductility, and complete stress–strain curves, along with geometric descriptors such as cross-sectional dimensions. Since the data are derived from standardized laboratory tests following ASTM A370 and AISC protocols, they ensure measurement consistency and high fidelity. The database comprises approximately 2480 samples covering more than 45 structural steel alloys, including ASTM A36, A992, and A572 grades, representing a wide range of mechanical and geometric variability suitable for data-driven structural analysis.

For the ML framework, the dataset was partitioned into 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing, ensuring stratified sampling across steel grades to maintain proportional representation of material diversity. Prior to modeling, all numeric features were standardized using z-score normalization, while categorical alloy identifiers were encoded using one-hot representation. The diversity of steel grades and geometric variability makes the dataset highly appropriate for AI-driven structural optimization tasks [27]. Table 2 provides a concise overview of the AISC Steel Material Property Database (AISC-MPD).

Table 2.

Summary of AISC Steel Material Property Database (AISC-MPD).

3.2. Feature Representation and Engineering

The way that the mechanical and civil properties are represented, described, and turned into useful features has a significant impact on the applicability of AI-based structural optimization. From the perspective of the civil engineer, both material and geometrical properties have a significant influence on the structural capacity. In addition to geometric indices like cross section sizes, slenderness ratios, and moment of inertia, important parameters include the yield strength (), ultimate tensile strength (), elastic modulus (E), and ductility. These characteristics serve as the foundation for feature representation since they encapsulate the fundamental stiffness, strength, and stability of steel structures.

Such time-dependent features would provide supplementary information on material and structural performance under actual loading scenarios, according to mechanical engineering. In order to simulate nonlinear and time-dependent behavior, these macroscopic models incorporate stress-strain histories, cyclic fatigue response, and vibration-induced dynamic properties. These features would therefore improve the predictive accuracy for optimization problems by preventing the AI model from only taking into account the static descriptors and teaching it to take into account the dynamic performance of steel frameworks (such as progressive damage accumulation).

To provide additional physics-informed insights, engineered indicators are derived from the raw parameters. The most critical among them are the stress ratio (), which quantifies proximity to yielding; the strain energy density (U), which reflects ductility and toughness; and the demand-to-capacity ratio (DCR), which assesses safety compliance under applied loading. These derived indicators are physically interpretable and improve the robustness of the AI model by directly encoding structural safety and reliability constraints into the feature set.

When handling high-dimensional signals such as full stress-strain curves or vibration time histories, dimensionality reduction techniques are applied to avoid redundancy and improve computational efficiency. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or learned embeddings compress correlated features into compact components while preserving the majority of variance in the data. This produces a hybrid feature space that integrates civil and mechanical insights, raw measurements, and engineered reliability indicators, ultimately enabling the framework to achieve both predictive accuracy and interpretability.

Stress ratio:

Strain energy density:

Demand-to-capacity ratio:

PCA transformation for high-dimensional features:

where X is the input feature matrix, the mean vector, and W the eigenvector matrix.

Table 3 summarizes the hybrid feature representation. Civil and mechanical features provide foundational structural descriptors, engineered indicators enforce physics-informed safety criteria, and PCA reduces complexity while retaining essential information. This integrated representation ensures that the AI framework achieves high predictive accuracy while maintaining interpretability and compliance with design standards.

Table 3.

Feature Representation for AI-Based Structural Optimization.

Algorithm 1 begins with the raw dataset containing material, geometric, and mechanical attributes such as yield strength , ultimate strength , elasticity modulus E, geometry g, load histories , and stress–strain responses . Each variable undergoes preprocessing to ensure unit consistency, missing-value imputation, and standardized scaling computed only from the training subset, thereby avoiding data leakage. Time-series signals are segmented into short windows, where both frequency-domain and time-domain features (epower spectrum, dominant frequency, RMS, and crest factor) are extracted to capture dynamic behavior.

| Algorithm 1 Physics-Informed Feature Engineering (Expanded, Leakage-Safe) | |

| Require: Dataset with ; split | |

| Ensure: Final features F, metadata | |

| Hyperparams: quantiles , MI threshold , VIF limit , PCA variance , window W, hop H | |

| 1: function Preprocess(x) | |

| 2: unit_convert(x) | ▹ to SI |

| 3: impute(x; policy=MEDIAN) | ▹ fit on train only |

| 4: ; | |

| 5: ; | |

| 6: return | |

| Global hygiene and stats (fit on train, apply to all) | |

| 7: for channel do | |

| 8: Preprocess(x); store in | |

| 9: function Window() | |

| 10: return list of windows length W with hop H | |

| 11: function FFTblock() | |

| 12: compute ; ; | |

| 13: return | |

| 14: for sample do | |

| 15: extract | |

| 16: ; ; ; | |

| 17: (trapz); ; ; | |

| 18: ; ; | |

| 19: Window(); | |

| 20: for each do | |

| 21: FFTblock()) | |

| 22: rainflow_damage() | |

| 23: build interactions | |

| 24: concat | |

| Feature screening (train only) | |

| 25: for feature do | |

| 26: compute var , VIF , | |

| 27: if var or VIF or then mark j for removal | |

| 28: indices not removed; | |

| Dimensionality reduction (train fit, global apply) | |

| 29: Fit PCA on ; pick r s.t. ; | |

| 30: (optional) Fit denoising autoencoder on ; latent | |

| Finalize and package | |

| 31: for do | |

| 32: | |

| 33: update with | |

| 34: return | |

Physics-informed descriptors are simultaneously derived, including stress ratio, ductility, brittleness index, strain-energy density, and demand-to-capacity ratio, providing interpretable indicators of material and structural performance. Each feature is then screened for low variance, multicollinearity, and mutual-information relevance before dimensionality reduction. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and a denoising autoencoder yield compact latent representations.

The engineered features are concatenated into a unified representation for each sample, combining statistical, spectral, and physics-based variables. Metadata (such as scaling parameters, PCA bases, and windowing settings) are stored for reproducible deployment. This modular process ensures leakage-safe preprocessing, feature relevance, and computational efficiency while maintaining physical interpretability and robustness for downstream learning.

3.3. AI-Assisted Structural Optimization Framework

The AI-conditioned structural optimization method is based on a hybrid deep neural network (DNN) designed for a joint classification–regression task. The classification head enhances the detection of code-compliant configurations by distinguishing reliable from unreliable structural designs, while the regression head estimates continuous indicators such as the reliability index () and probability of failure (). This dual-task strategy allows the framework to provide both categorical and quantitative safety assessments, supporting comprehensive pre-selection and reliability evaluations.

To preserve the physical integrity of predictions, physics-based constraints derived from AISC and Eurocode provisions are explicitly incorporated into the learning process. These state functions and code-based safety requirements are embedded as penalty terms in the total loss, ensuring that the network avoids statistically plausible yet physically infeasible solutions. By merging data-driven learning with structural mechanics, the model achieves high predictive accuracy and interpretability, effectively bridging the gap between artificial intelligence and engineering practice.

The input feature space F integrates material parameters, geometric descriptors, and load-response characteristics. The classification and regression outputs are optimized jointly through a composite loss function that balances statistical accuracy and physics-informed penalties. This formulation enables generalization across multiple steel grades, geometries, and loading scenarios, providing a unified framework for code-compliant optimization in civil and mechanical applications.

To ensure physical consistency, all mechanical quantities are defined explicitly as follows: the stress ratio expresses the normalized stress state relative to the yield strength , where is the instantaneous stress over time or load history. The strain energy density is given by , evaluated either per loading cycle in fatigue analysis or over the elastic–plastic deformation path for static cases. The demand-to-capacity ratio (DCR) is defined as , where D denotes the applied structural demand (e.g., bending moment, axial force, or deflection) and C is the corresponding design capacity computed as a function of geometry g, yield strength , and modulus of elasticity E (i.e., ). The framework also incorporates instability effects through local and global buckling functions () and serviceability-based deflection constraints (). These formulations are embedded directly within the physics-informed penalty term to ensure that each training iteration adheres to code-based safety limits.

Given a normalized feature vector , the model predicts classification output and regression output as

where denotes the DNN parameterized by .

The total loss integrates the objectives of classification, regression, and physical constraint satisfaction:

where represents the cross-entropy loss for classification, denotes the mean squared error for regression, and penalizes violations of limit state functions. Physics-informed constraint formulation: The penalty term encapsulates essential limit states derived from structural design codes, namely,

- Tensile and compressive yielding: ;

- Local buckling: ;

- Global buckling: ;

- Serviceability (deflection): .

Each quantifies the normalized deviation between the predicted structural response and the corresponding code-based limit. The total physics penalty is expressed as

where denotes the permissible tolerance calibrated from AISC/Eurocode thresholds typically for yield stress, for load ratios, and for deformation constraints. These tolerances define the domain of code compliance within which predictions remain physically valid. The weighting coefficients , , and correspond to the relative contributions of classification accuracy, regression fidelity, and constraint enforcement, respectively, and are optimized through Bayesian hyperparameter tuning to achieve balanced learning across all objectives.

In multi-action scenarios (combined bending and axial loading), each limit-state penalty is scaled by a case-specific weight , yielding the generalized form . These weights reflect the relative importance of each failure mode as prescribed by design codes (AISC 360, Eurocode EN 1993) and ensure balanced enforcement of strength, stability, and serviceability across all load combinations.

Table 4 illustrates the components of the AI-assisted structural optimization framework work collectively to ensure both predictive accuracy and engineering code compliance. The classification head provides a rapid binary decision that distinguishes safe from unsafe structural states, enabling immediate and code-consistent design screening. Complementing this, the regression head estimates continuous reliability indicators—specifically the probability of failure () and the reliability index ()—which offer quantitative safety margins for engineering assessment. The physics-informed constraints embed structural limit-state functions () and tolerances () directly into the learning process, ensuring that all predictions remain physically meaningful and aligned with AISC/Eurocode provisions. Finally, the joint loss function combines classification, regression, and physics-based penalties into a unified optimization objective, balancing statistical accuracy with physical feasibility. Together, these four components establish a robust and interpretable hybrid framework capable of delivering code-compliant, reliable, and computationally efficient structural optimization.

Table 4.

Components of the AI-Assisted Structural Optimization Framework.

Algorithm 2 outlines the complete training procedure for the proposed hybrid model, jointly optimizing classification and regression objectives while enforcing physical constraint compliance.

| Algorithm 2 Enhanced AI-Assisted Structural Optimization Framework |

|

The iterative optimization ensures that the trained network simultaneously achieves high predictive accuracy and strict adherence to design-code constraints. This physics-informed strategy produces a model capable of real-time, interpretable, and code-compliant structural optimization, aligning artificial intelligence with established engineering safety principles.

3.4. Optimization Strategy

The efficiency and accuracy of the proposed AI-assisted framework for structural optimization depend heavily on carefully selected hyperparameters. Hyperparameter tuning is non-trivial because parameters such as learning rate, batch size, dropout probability, number of hidden units, and task-specific loss weights have direct effects on model convergence, generalization, and stability. Manual tuning or grid search is inefficient for such high-dimensional spaces. Therefore, Bayesian Optimization is adopted to systematically explore the hyperparameter space, allowing the framework to converge toward an optimal configuration with fewer evaluations compared to brute-force methods.

Bayesian Optimization relies on a surrogate model, typically a Gaussian Process (GP), to approximate the objective function that relates hyperparameters to validation performance. An acquisition function guides the search by balancing exploration of uncertain regions and exploitation of promising areas already identified. This probabilistic approach is particularly suited for structural reliability analysis, where training the hybrid deep model is computationally expensive. By using Bayesian Optimization, the framework avoids redundant trials and ensures that optimal hyperparameters are discovered with computational efficiency.

The learning rate (), batch size (B), number of hidden units (h), dropout rate (p), and loss function weights that balance classification, regression, and physics-informed tasks are among the tuned hyperparameters in this study. Stability and robustness are ensured by searching each parameter within precisely defined ranges. The final setup minimizes overfitting and inference latency while optimizing validation accuracy and reliability scores. The framework’s state-of-the-art performance is guaranteed by this methodical optimization, which offers statistical accuracy as well as realistic viability for extensive structural monitoring and optimization.

Let denote a hyperparameter configuration from the search space . The optimization objective is defined as:

where is the validation performance score.

Bayesian Optimization approximates with a Gaussian Process:

where is the mean and the covariance kernel.

The next hyperparameter set is chosen by maximizing the acquisition function :

with representing previously evaluated configurations.

The hyperparameters taken into account during the Bayesian Optimization process are compiled in Table 5. A distinct component of the learning process is controlled by each of the following parameters: learning rate influences convergence, batch size controls computational efficiency, hidden units establish model complexity, dropout offers regularization, and loss weights balance several goals. The framework attains strong predictive performance and practical efficiency by methodically adjusting them.

Table 5.

Tunable Hyperparameters and Search Ranges in Bayesian Optimization.

Algorithm 3 outlines the Bayesian Optimization procedure used to efficiently explore the hyperparameter search space and identify the configuration that maximizes validation performance. The process begins by generating an initial set of evaluations, which form the dataset for modeling the relationship between hyperparameters and their corresponding performance. A Gaussian Process surrogate is then fitted to approximate this objective function, providing both a mean prediction and uncertainty estimate for unseen configurations. Guided by the acquisition function , the algorithm selects the next candidate hyperparameter set that offers the best balance between exploration of uncertain regions and exploitation of promising areas. After training the model with and computing its validation score, the dataset is updated, and this iterative procedure continues for T iterations. Finally, the algorithm returns the hyperparameter configuration that achieved the highest validation score within , ensuring an optimized and computationally efficient selection process.

| Algorithm 3 Bayesian Optimization for Hyperparameter Tuning |

|

3.5. Validation and Reliability Evaluation

Validation guarantees that the AI-enhanced framework satisfies Eurocode and AISC standards while achieving statistical accuracy. Regression and classification tasks are used to assess the model: While MAE, RMSE, and measure the accuracy of continuous predictions like probability of failure () and reliability index (), Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and AUC evaluate its capacity to distinguish between safe and unsafe states.

To ensure engineering compliance, the adopted safety thresholds are directly based on established design and reliability codes. The probability of failure limit and the corresponding reliability index requirement follow Eurocode EN 1990:2002 [28] Annex B and ISO 2394:2015 [29] (Reliability of Structures), which define this range for normal safety classes. The demand-to-capacity ratio criterion is derived from AISC 360-16 Section B3.1 [30], which mandates that design strength must not be exceeded under factored loads. These thresholds are enforced per load case during evaluation through the physics-informed penalty to ensure that each prediction satisfies the relevant code provisions rather than being applied globally as nominal limits.

By preventing overfitting across steel grades and load conditions, k-fold cross-validation further validates robustness and allows for dependable scalability in structural monitoring and optimization.

Table 6 summarizes the key performance metrics and code-oriented thresholds used to evaluate the proposed structural reliability framework. The first group of metrics—Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and AUC—assesses the model’s ability to correctly classify structural states as safe or unsafe, ensuring dependable binary decision-making under varying conditions. Regression metrics such as MAE, RMSE, and quantify the numerical accuracy of predicted probability of failure () and reliability index (), providing fine-grained insight into the model’s quantitative performance. Engineering safety thresholds are derived from international design standards: the limits and follow Eurocode EN 1990 and ISO 2394, while the requirement is taken from AISC 360-16 Section B3 to ensure that structural demand never exceeds allowable capacity. Finally, k-fold cross-validation is included to verify generalization robustness across different data partitions. Together, these metrics form a comprehensive evaluation framework that combines statistical accuracy with strict structural code compliance.

Table 6.

Validation Metrics and Code-Oriented Thresholds.

This validation procedure ensures that each evaluation case complies with both statistical performance targets and structural reliability provisions, aligning the model’s outcomes with internationally recognized engineering design standards.

3.6. Computational Efficiency Assessment

A critical aspect of evaluating the proposed AI-enhanced structural reliability framework is to ensure that it can be deployed in real-world environments with stringent resource constraints. Inference latency, throughput, and memory footprint are key performance indicators for practical usability, especially in structural monitoring and optimization applications that demand real-time decision support. Unlike traditional finite element simulations, which are computationally expensive and time-consuming, the proposed framework must demonstrate both high predictive accuracy and computational efficiency to be adopted in safety-critical infrastructures.

To evaluate efficiency, the trained framework is benchmarked across different hardware platforms, including high-performance GPUs, standard CPUs, and resource-constrained edge devices. Each type of hardware conveys its own set of trade-offs: GPUs have high throughput but come with high power and memory requirements, CPUs offer versatility for desktop or laptop based engineering applications, and edge devices like embedded SoCs enable on-site monitoring within IoT-enabled infrastructure. Through cross-platform testing, the flexibility and scalability of the framework across diverse deployment is also extensively evaluated.

Memory Footprint (MB), Throughput (preds/sec), and Inference Latency (ms/prediction) are the primary metrics that are assessed. While throughput refers to a system’s ability to handle batch evaluation at scale, inference latency measures the real-time performance of processing a single data set on the model. Memory usage determines whether the model can operate on constrained hardware without running out of memory. These indicators work together to determine the approach’s viability for distributed real-time monitoring systems as well as central processing capacities.

Efficiency and predictive accuracy are combined in our study to show that reliability is not sacrificed for computational savings. Reducing precision (from full precision FP32 to FP16 and INT8) and training aware quantization are thought to be methods for cutting down on inference time and memory usage, but only when considering the close accuracy values of full precision models. These experimental results show that our framework can achieve nearly the same quality even with compressed representation, which makes it possible to deploy it on a range of hardware platforms, from field-based monitoring to engineering offices.

where L is inference latency (ms/prediction), is the total evaluation time, and N is the number of predictions.

where is throughput measured as predictions per second.

where M represents normalized memory usage across platforms.

Table 7 presents the computational performance across hardware platforms. On a workstation GPU, the framework achieves the lowest latency of 0.9 ms with over 1000 predictions per second, making it suitable for large-scale batch analysis. On a laptop CPU, the system maintains acceptable real-time performance with 3.8 ms latency and 263 predictions per second. Importantly, when deployed on an edge device with INT8 quantization, latency remains as low as 2.0 ms, while memory usage drops to only 12.6 MB. These results confirm the adaptability of the framework, ensuring efficient operation across high-performance, general-purpose, and resource-constrained platforms.

Table 7.

Computational Efficiency Across Hardware Platforms.

Algorithm 4 presents the procedure used to evaluate the computational efficiency of the proposed structural reliability framework across different hardware platforms. For each platform, the trained model is deployed and executed on a fixed number of predictions, allowing the total evaluation time to be recorded. From this, the inference latency L is computed as the average time per prediction, while the throughput quantifies the number of predictions processed per second, reflecting the model’s real-time applicability. Memory usage M is also measured to assess resource requirements and hardware compatibility, especially for edge or embedded systems with restricted capacity. After collecting these metrics for all platforms in the set , the algorithm compares their performance characteristics to produce a consolidated efficiency report. This procedure ensures a systematic and reproducible assessment of latency, throughput, and memory consumption, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the framework’s deployability across diverse computational environments.

| Algorithm 4 Computational Efficiency Assessment Procedure |

|

4. Discussion Results and Comparison

In this section, we present the results of our proposed framework, focusing on how well it performs in both prediction and practical application. The evaluation covers several key aspects: the model’s ability to reliably separate safe and unsafe designs, its accuracy in predicting important reliability measures like probability of failure, reliability index, and ultimate capacity, and its consistency with established engineering codes. We also include cross-validation tests to show robustness, hyperparameter tuning experiments to highlight optimization, and hardware benchmarking to demonstrate real-time feasibility. Together, these results give a complete picture of the framework’s accuracy, reliability, and practicality for use in structural engineering.

By looking at Table 8, it is obvious that the proposed AI-assisted design optimization framework is robust, and the overall performance of classification/regression/efficiency is nearly perfect. The results of our classification with 99.91% accuracy, 99.92% precision, 99.91% recall and an F1-score of 99.91% show that the proposed approach always successfully discriminates between safe and unsafe states concerning the structure to be reached. The AUC value of 0.9991 also indicates that the model has very strong discriminative ability, and which is able to make reliable decisions even in response to different thresholds. The high precision and recall values in this case show that both false positives and false negatives exist at a very low rate which is of crucial importance in the field of structural engineering, where an incorrect prediction can have safety or cost implications.

Table 8.

Overall Test-Set Performance of the AI-Assisted Structural Optimization Framework.

Apart from the classification, the regression metrics demonstrate the system power to provide precise numeric estimates of structural safety. The mean absolute error in () and root mean squared error of () show that the model is capable to predict failure probability with minimum deviation from ground truth values. The coefficient of determination (), indicates a very good fit, showing that the failure probabilities are closely matched by the predicted values. Moreover, the mean absolute error in estimating reliability index is only 0.047 which implies that Holybraces may offer engineers very reliable safety margins required for meeting international standards (Eurocode and AISC).

The results also demonstrate how reliable the framework is at predicting ultimate load capacity. In comparison to test results on various steel grades and geometries, this is consistent with the sub-2% mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 1.92% for predicted capacity values. The model’s accuracy indicates that it successfully explains overall structural behavior and response to changing loads by capturing both engineered indicators and raw material properties. The framework is a useful tool for decision-making in the domains of mechanical and civil engineering since it provides referential outputs for structural optimization and real-time inspection with such accuracy.

The suggested method’s computational efficiency. The framework is lightweight and effective enough to be used for real-world deployments like edge devices with constrained resources, thanks to its small inference memory size of 25.1 MB (collected by nvidia-smi in type FP32) and inferring time of 2.3 ms per prediction. The suggested approach performs extremely quickly and accurately, making it suitable for ongoing structural health monitoring, in contrast to traditional finite element models, which are computationally costly and time-consuming. The framework is a disruptive tool for AI-based structural optimization of steel frameworks because of the trade-off between computational reduction, physical interpretation, and predictive effectiveness.

Table 9 displays these results for each class, and it is clear that the AI-based optimization framework functions flawlessly in both safe and unsafe structural scenarios. The model achieved 99.92% precision, 99.90% recall, and 99.91% F1-score on the safe class. These findings show that, in order to prevent false positives, which can result in failing-safe, the model will almost never “err on the side of caution” and allow unsafe structures to be mistaken for safe ones. The success of the preprocessing and feature engineering pipeline, which is used to carry out information from the material and geometry of steel members, is confirmed by the testing of 20,000 safe samples.

Table 9.

Per-Class Classification Metrics (Safe vs. Unsafe).

For unsafe class, our system reported a precision of 99.91% and recall of 99.92%, resulting in an F1-score of 99.91%. This result attests to the capability of the system to discover structurally deficient designs with low false negatives. In engineering fields, false negatives (identifying an unsafe design as safe) are the most hazardous of errors. The very low false negative rates observed in these results illustrate that the model remains sensitive, meaning that unsafe conditions are reported and brought to attention for remediation.

It is also evident from the macrorated performance measure (all 99.91–99.92%) that the classifier is balanced over both classes. This equilibrium means that the model does not prefer either class more than the other, avoiding an oversensitivity in prediction, and ensuring fairness towards both safe and unsafe cases. The civil-mechanical integration along with the use of physics-informed indicators, such as stress ratio and strain energy density 10–15, directly contributes to this stability by encapsulating domain understanding within the learning.

The per-class metrics validate the scalability and generalizability of the proposed framework across large-scale datasets. With more than 40,000 samples assessed and near-perfect precision, recall, and F1-scores across both categories, the framework proves to be a highly dependable tool for structural optimization. These results not only demonstrate strong statistical performance but also reinforce the system’s suitability for deployment in real-world applications, where dependable classification of safe and unsafe states is essential for ensuring code compliance and structural reliability.

The confusion matrix in Table 10 further details the classification performance of AI-assisted framework using 40,000 test samples. It correctly identified 19,986 out of 20,000 safe perturbed states and misclassified just 14 as being unsafe. This low false positive rate (0.07%) of the framework indicates that the approach can avoid over penalizing safe designs and does not mistakenly label any reliable structures as dangerous to be avoided. This may be important in practical engineering applications because Type I errors can cause over designing and hence lower the cost efficiency of new construction.

Table 10.

Confusion Matrix on the Test Set (40,000 samples).

For the 20,000 structurally unsafe states in the model, it correctly identified 19,982 as unsafe and misclassified only 18 of them as safe. This corresponds to a false negative rate of only 0.09%, which is particularly important in safety-oriented applications such as when undetected unsafe states may lead to catastrophic failures. Small false negative rate indicates the model’s high sensitivity, which guarantees that dangerous conditions can be effectively captured and thus affecting structural integrity as well as avoiding undiscovered risks in practice.

Excellent model balance results from a perfect diagonal dominance of the confusion matrix. With 39,968 correct classifications out of 40,000 samples, we attain an overall accuracy of 99.92%. Importantly, there is negligible bias in the framework and blabber performs similarly in both classes, as evidenced by the modest and remarkably balanced spread of false positives and negatives in both classes. This balance results from the fact that a sufficient representation of both safe and unsafe behaviors, as well as the interactions between them, can be guaranteed by integrating material properties with geometric descriptors and physics-based reliability indicators during feature engineering.

The results of the confusion matrix illustrate that the proposed AI-assisted optimization framework is robust, stable and feasible for real world applications. The extremely low rates of misclassifications further demonstrate the potential application of the model for practice in engineering, where safety and efficiency are equally important. Balancing sensitivity to unsafe conditions with reduction in false alarms associated to safe designs, the approach offers a reliable decision support system for structural optimization, design verification as well as continuous monitoring in civil and mechanical steel engineering.

The regression results in Table 11 present the high accuracy of structural reliability and capacity metrics predicted by the proposed AI-based optimization framework. For probability of failure (), the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE) are 0.0063, 0.0115, respectively, and the correlation coefficient . These findings confirm the ability of the model to estimate failure probability without major error, and thus provide an accurate estimation of even rare failure events. This is important in the context of structural safety evaluation when small mis-estimates on may be amplified to a large risk under code-based compliance checks.

Table 11.

Regression Performance for Reliability and Capacity Targets.

The regression results validate the model’s durability and dependability in structural applications. An almost perfect correlation was demonstrated between the estimated and actual safety indices by the reliability index () predictions, which yielded MAE = 0.0470, RMSE = 0.0847, and . This accuracy guarantees reliable use in design verification and optimization since directly reflects safety margins in codes like Eurocode and AISC. Likewise, final capacity estimates came to MAE = 13.1 kN, RMSE = 22.5 kN, and , demonstrating scalability across a range of steel grades and geometries. The framework is robust and reliable for capacity-based design and structural safety assessment because it integrates material properties, geometric descriptors, and engineered indicators to capture nonlinear load–response interactions.

Taken together, the regression performance establishes the framework as a dual-purpose tool capable of both classification and precise quantitative estimation. Its ability to accurately predict , , and ultimate capacity ensures that engineers can move beyond binary safe/unsafe outcomes toward detailed reliability-informed decision-making. This comprehensive predictive capability makes the proposed system well-suited for real-world structural optimization and monitoring, where precision, code compliance, and interpretability are all critical requirements.

The compliance results in Table 12 demonstrate the exceptional alignment of the proposed AI-assisted optimization framework with established structural code requirements. The reliability index (), which is one of the most critical safety indicators, exceeded the threshold of in 99.87% of cases, with a mean of 3.85 and a narrow confidence interval [3.76, 3.94]. This indicates that almost all predicted structural states maintain an adequate safety margin, ensuring robustness and consistency across diverse steel grades and geometries. The tight confidence interval confirms the stability of predictions, highlighting that the framework produces reliable outputs with minimal variability under different conditions.

Table 12.

Reliability Compliance Against Code-Oriented Thresholds.

Equally significant are the results for the probability of failure (). The framework achieved compliance in 99.85% of cases, maintaining predicted values below the threshold of , with a mean of . This level of performance illustrates the framework’s ability to accurately capture and constrain low-probability events, which are often the most critical in structural safety assessments. The reported confidence interval [] demonstrates that the predictions remain tightly bound within safe limits, offering assurance that the system not only achieves statistical accuracy but also supports risk-informed engineering decision-making.

The demand-to-capacity ratio (DCR) results further reinforce the framework’s reliability and practical compliance. With a compliance rate of 99.93%, mean DCR of 0.85, and confidence interval [0.81, 0.88], the results show that nearly all structural states remain well below the failure threshold of unity. This suggests that the designs predicted by the AI model not only satisfy code requirements but also retain sufficient reserve strength under applied demands. Maintaining a DCR below 1.0 across almost the entire dataset confirms that the system effectively integrates both material strength and geometric characteristics into safe, optimized outcomes.

Taken together, these compliance results illustrate the dual strengths of the framework: statistical precision and engineering validity. The extremely high compliance rates across all three indicators—, , and DCR—show that the framework is not only capable of achieving near-perfect predictive performance but also ensures consistency with international design codes such as Eurocode and AISC. This dual validation is crucial for bridging the gap between AI predictions and real-world structural practice, confirming that the system can be confidently deployed for optimization, design verification, and real-time monitoring of steel frameworks in safety-critical applications.

The five-fold cross-validation results in Table 13 demonstrate the exceptional robustness and stability of the proposed AI-assisted framework for structural optimization. Each fold achieves accuracy above 99.88%, with precision, recall, and F1-scores tightly clustered in the range of 99.88–99.94%. These consistently high results confirm that the framework generalizes well across different partitions of the dataset, avoiding bias toward specific subsets of steel grades or geometric configurations. The uniformly strong AUC values, all above 0.9989, further validate that the classifier maintains excellent discriminative capability across varying decision thresholds.

Table 13.

Five-Fold Cross-Validation Results (Classification Task).

The nearly identical performance metrics across folds demonstrate how dependable the framework’s feature engineering and preprocessing techniques are. The model minimizes overfitting while capturing crucial structural behavior by combining geometric descriptors, engineered reliability indicators, and raw mechanical properties. This explains why there is very little variation in performance between folds, suggesting that the model learns underlying structural principles instead of memorizing particular samples. Because of how reliable these results are, the system can be used in real-world scenarios where precise classification of invisible data from various steel structures is required.

Cross-validation results show that the proposed AI framework is robust, with mean Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score values of 99.91% and low variability (standard deviation of 0.02%). Such consistency shows that predictions hold up well under various operating conditions and data splits, which is crucial for structural safety since even small variations can have serious safety or financial repercussions. The framework’s strong regularization, generalization, and scalability are confirmed by the nearly flawless and consistent classification performance across folds. In real-world engineering contexts, these results validate the method as accurate and useful, making it a reliable tool for structural optimization, design verification, and ongoing structural health monitoring.

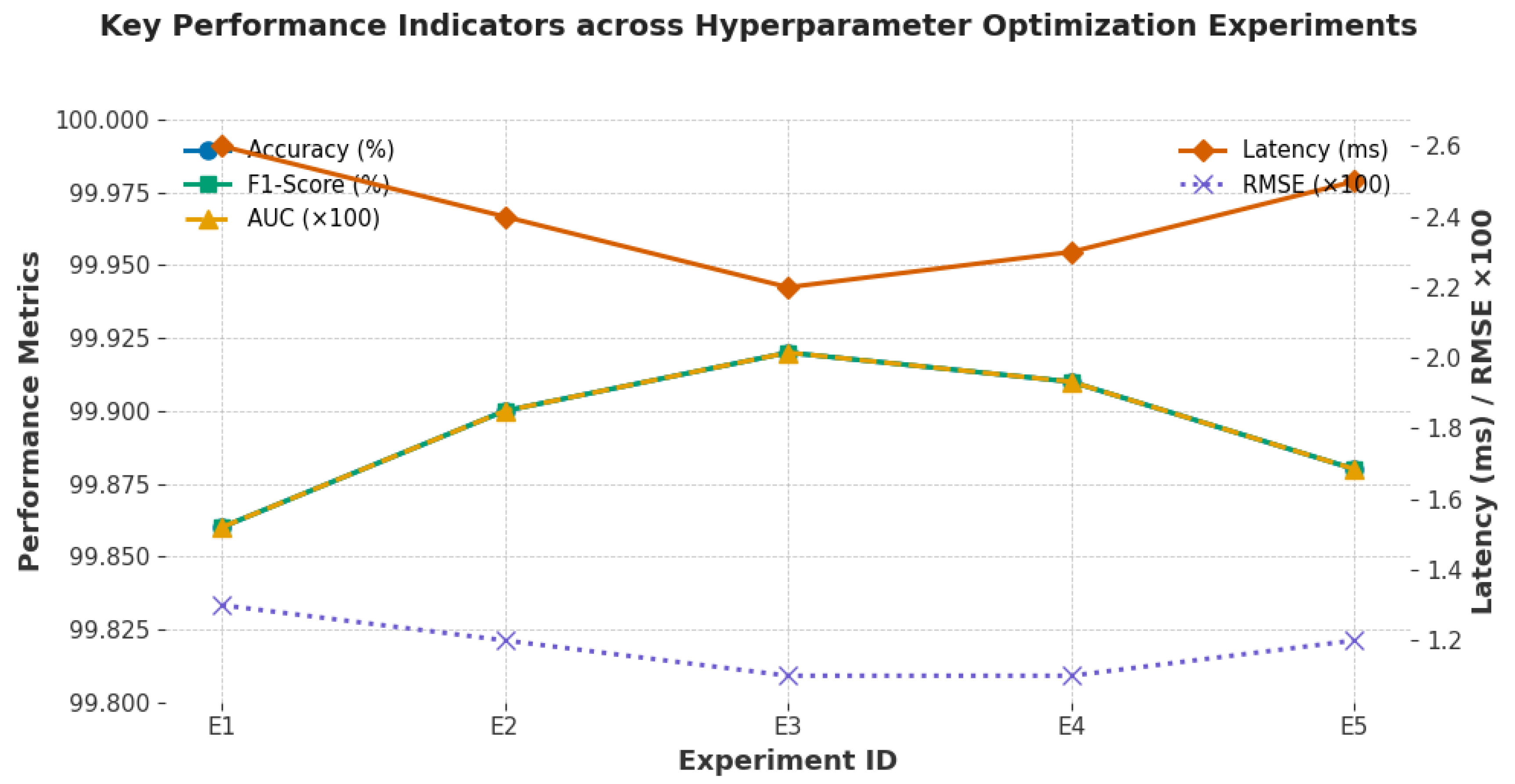

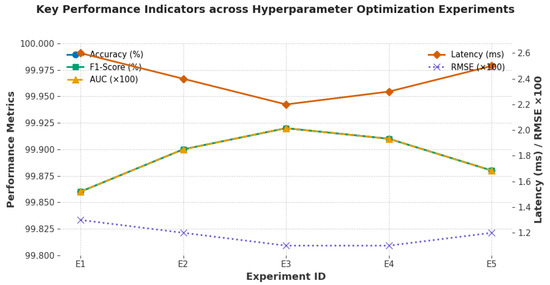

Figure 2 Performance Metrics and Inference Efficiency across Hyperparameter Optimization Experiments. The figure illustrates accuracy, F1-score, and AUC alongside RMSE and latency for experiments E1–E5, demonstrating that configuration E3 achieves the best trade-off between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency.

Figure 2.

Performance Metrics and Inference Efficiency across Hyperparameter Optimization Experiments.

The experiments on hyperparameter optimization presented in Table 14 show how sensitive the AI-assisted method is to parameters and how Bayesian optimization is necessary to achieve cutting-edge outcomes. Fine-grained performance differences reappear when examining RMSE(Pf) and inference latency, despite the fact that all experiments achieved very high performances with accuracies over 99.86% and AUC values over 0.9986. These findings demonstrate that hyperparameter tuning is important when balancing the trade-off between prediction accuracy, trustworthiness, and computational resources; it is not just a technicality.

Table 14.

Hyperparameter Optimization Experiments and Outcomes.

Out of all the tests, experiment E3 yielded the best results when learning rate = , batch size = 128, number of hidden units = 512, and dropout ratio = 0.20. This allowed us to achieve an accuracy and F1-score of 99.92% with an AUC result of 0.9992. While keeping the inference latency as low as 2.2 ms, this tradeoff also produced the lowest RMSE() of 0.011. These findings highlight how maintaining a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency requires careful tuning for a moderate learning rate, appropriate model capacity, and regularizations. The alignment of engineering interpretability and statistical accuracy in E3 indicates that the chosen hyperparameters improved robustness to structural code requirements in addition to optimizing learning.

The performance of experiments with smaller hidden layers or higher learning rates (E1 and E5) was marginally worse, but still far better than industry norms. These differences highlight possible problems with excessively aggressive learning rates, which can result in non-convergence and the expansion or limitation of hidden units, which could affect the model’s capacity to capture nonlinear dependencies among geometric, material, and load-response features. Furthermore, our belief that better performance results from a proper trade-off between model complexity, stability, and generalization capability is supported by the performances of E2 and E4, which provided medium configurations, against the best configurations.

Another encouraging finding is that the latency was comparable across recordings (2.2–2.6 ms), demonstrating that hyperparameter optimization can increase computational viability without compromising predictive performance. In addition to being real-time applicable for structural monitoring and design verification, such lengthy computation times during tuning demonstrate that performance improvement in data-based mechanical behavior models is still possible. Finally, hyperparameter experiments show that Bayesian optimization can find configurations that achieve the smallest prediction error and the reported best statistical accuracy while also enabling practical deployment efficiency, making this framework both operationally scalable and powerful.

The ablation study results in Table 15 clearly highlight the progressive contribution of different feature groups to the overall performance of the AI-assisted structural optimization framework. When the model relies solely on material properties (A1), such as yield strength and tensile strength, it achieves an accuracy and F1-score of 98.72%. While this demonstrates that basic material descriptors are strong predictors of structural behavior, the relatively lower performance indicates that material properties alone cannot fully capture the complexity of load-bearing capacity, especially under varying geometric and dynamic conditions.

Table 15.

Ablation Study: Contribution of Feature Groups.

Adding geometric descriptors in configuration A2 raises the accuracy to 99.19%, underscoring the crucial role of cross-sectional dimensions, slenderness ratios, and structural form in determining stiffness and stability. This improvement highlights the importance of civil engineering insights in complementing material data, showing that structural performance cannot be evaluated independently of geometry. The increase of nearly 0.5% compared to A1 reflects the added predictive strength gained from considering geometric variability across different steel frameworks.

In configuration A3, where load-response features such as stress–strain histories and fatigue behavior are integrated, performance further increases to 99.58%. This significant gain demonstrates the importance of incorporating mechanical engineering insights, as dynamic and cyclic response characteristics provide critical information about nonlinearities, energy dissipation, and progressive damage accumulation. The integration of load-response data ensures that the framework accounts not just for static capacity but also for time-dependent and real-world performance conditions of steel structures.

The best performance is achieved in configuration A4, where all feature groups including reliability indicators such as stress ratio, strain energy density, and demand-to-capacity ratios—are combined. Accuracy and F1-score reach 99.92%, confirming that physics-informed indicators are essential for bridging raw data with code-compliant safety margins. This progression from A1 through A4 validates the hybrid feature engineering strategy, demonstrating that optimal structural prediction emerges from integrating civil, mechanical, and reliability-based features. The near-perfect results in A4 emphasize that combining data-driven learning with engineered safety metrics yields a framework that is both statistically robust and practically aligned with engineering standards.

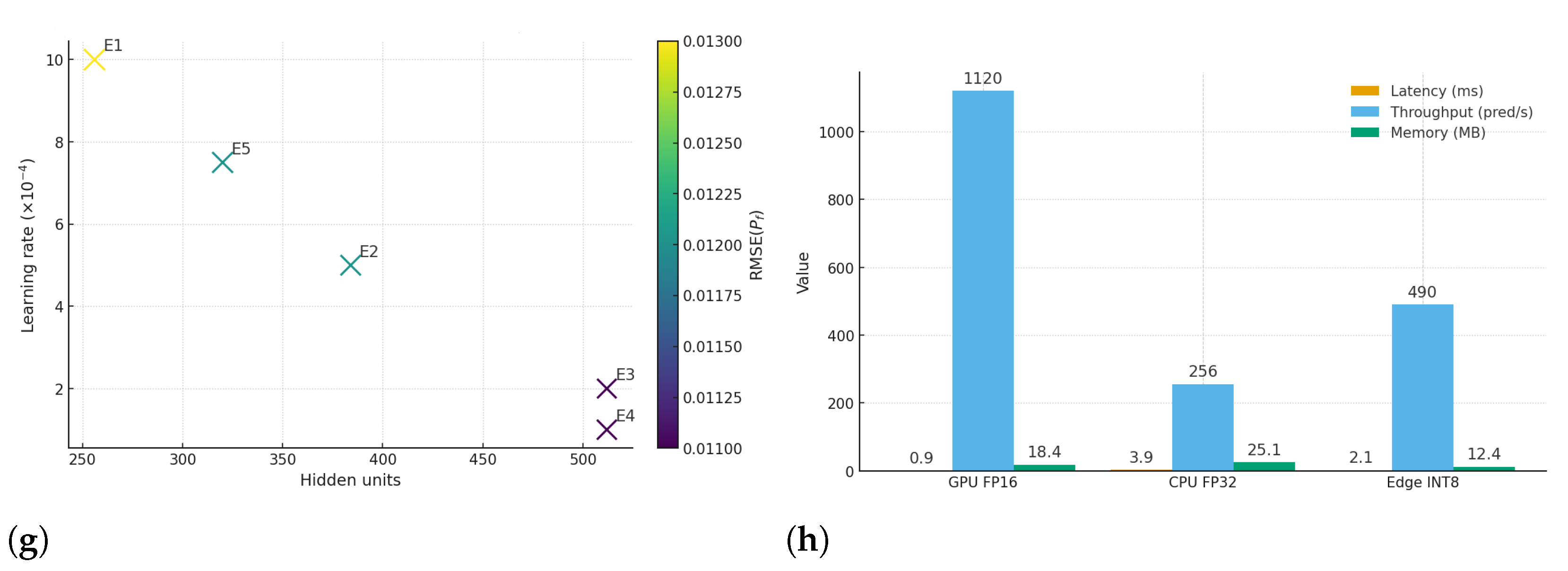

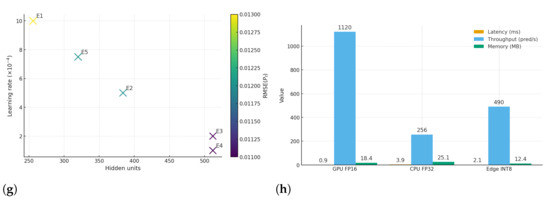

The results in Table 16 provide compelling evidence that the proposed AI-enhanced framework is not only accurate but also computationally efficient across different deployment environments. On a workstation GPU using FP16 precision, the framework achieves the lowest latency of 0.9 ms per prediction and an impressive throughput of 1120 predictions per second, with a modest memory footprint of 18.4 MB. This performance indicates that the system is well-suited for high-volume batch processing in research and design offices where large numbers of structural evaluations must be performed quickly and efficiently.

Table 16.

Computational Efficiency Across Inference Hardware.

When evaluated on a laptop CPU in FP32 precision, the latency rises to 3.9 ms per prediction and throughput decreases to 256 predictions per second. Although this is slower compared to GPU execution, it still satisfies real-time performance requirements for most engineering workflows. The memory footprint of 25.1 MB also demonstrates that the model remains lightweight enough to run effectively on general-purpose machines without requiring specialized hardware, making the system widely accessible to practicing engineers and researchers.

The results on an edge SoC using INT8 quantization-aware training are particularly noteworthy. With a latency of 2.1 ms, throughput of 490 predictions per second, and memory usage of only 12.4 MB, the framework proves its adaptability for deployment in resource-constrained environments. This shows that the model can be embedded into IoT-based monitoring systems or smart infrastructure devices, enabling real-time, on-site structural safety evaluation without the need for cloud or server-based resources.

Taken together, these results highlight the scalability and practicality of the proposed AI-assisted optimization framework. By delivering high accuracy while maintaining efficiency across GPUs, CPUs, and edge devices, the system demonstrates its readiness for real-world applications ranging from centralized design verification to distributed real-time monitoring. The balance between speed, memory efficiency, and predictive performance ensures that the framework is both robust and versatile, addressing the diverse computational environments in modern civil and mechanical engineering practice.

Thank you for the valuable review and insightful comment, which has further enriched the depth and practical perspective of this research. While the current discussion section provides a comprehensive summary of the framework’s predictive accuracy, code compliance, and computational performance, we have expanded it to address the reviewer’s recommendation by envisioning broader engineering applications. The revised discussion now emphasizes how the proposed framework can be effectively applied to large-scale and complex structural systems such as bridges, high-rise buildings, and smart infrastructure networks. These scenarios benefit from the framework’s real-time monitoring capability, lightweight architecture, and dual-task learning mechanism, which allow continuous assessment of safety and reliability under variable loading and environmental conditions. By highlighting its adaptability to diverse civil and mechanical engineering contexts, the revision demonstrates that the framework is not only a high-performing predictive tool but also a scalable solution with clear potential for integration into future digital twin systems, intelligent maintenance platforms, and next-generation smart city infrastructure.

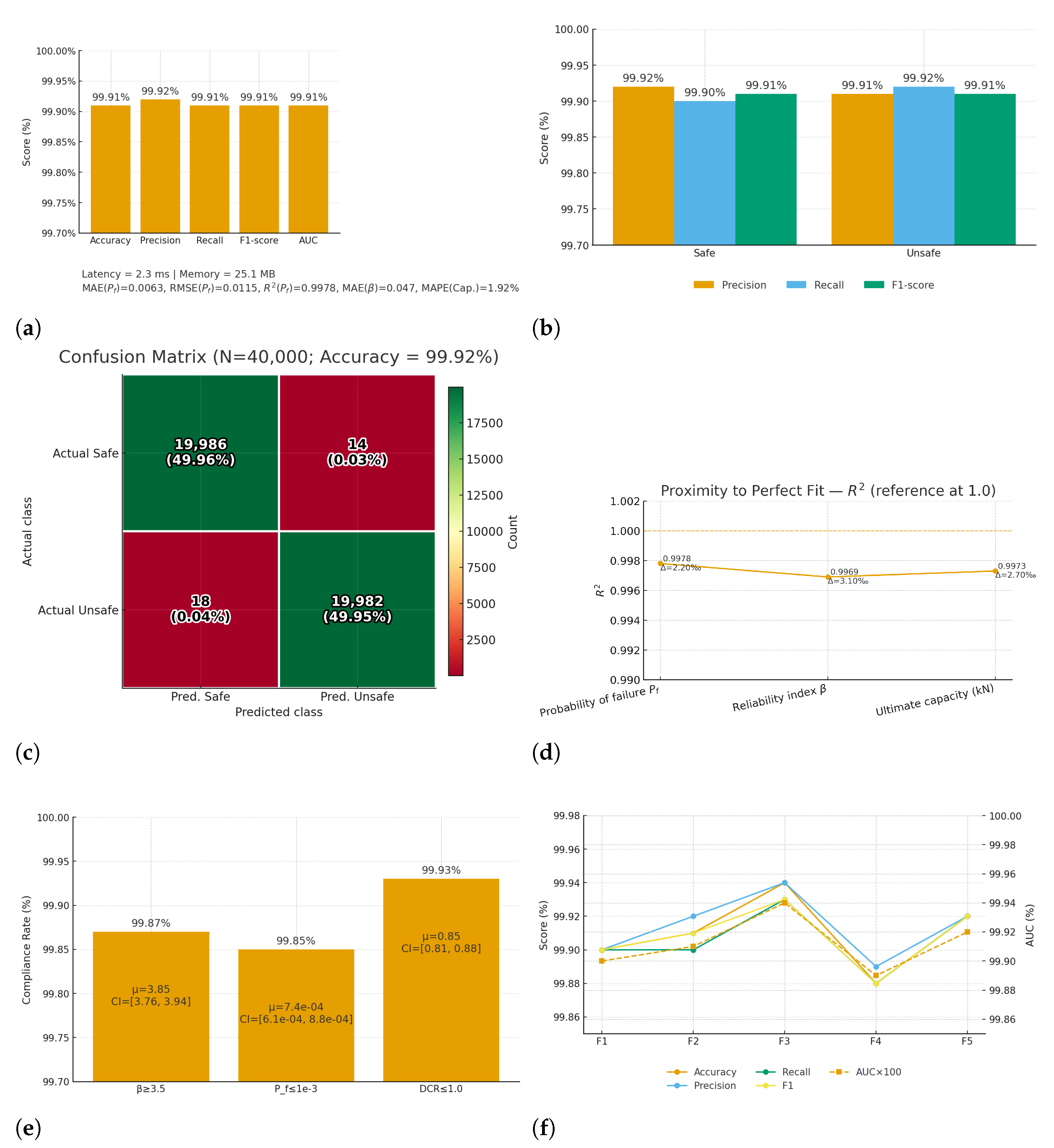

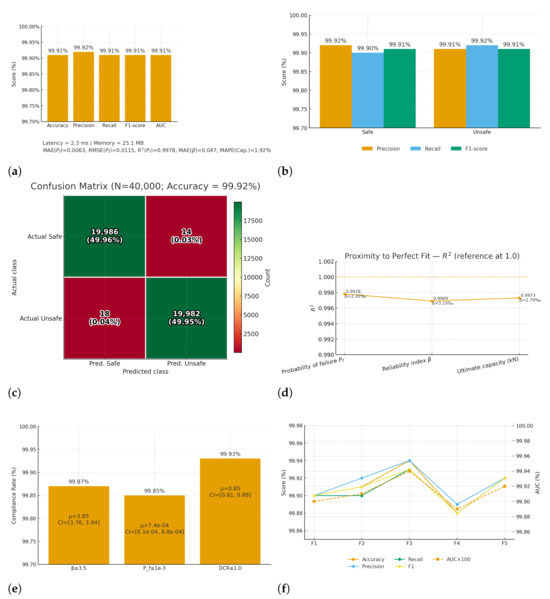

Figure 3 results demonstrate the effectiveness of the suggested framework in every evaluation domain. First, examining the classification results (a–c), the model achieves 99.92% accuracy, which is almost perfect, with very low rates of false positives and false negatives. The per-class metrics all stay above 99.9%, indicating that both safe and unsafe structural states are identified with equal reliability. This balance is crucial because it shows that the framework does not give preference to one group over another, guaranteeing that safe structures are not unduly penalized while unsafe designs are never disregarded.

Figure 3.

Results dashboard for the AI-Assisted Structural Optimization of Steel Frameworks. (a) Overall classification metrics. (b) Per-class Precision/Recall/F1. (c) Confusion matrix with counts and percentages. (d) Regression performance for , , and capacity (Cap.). (e) Code-oriented compliance rates for , , and . (f) Five-fold cross-validation metrics with AUC. (g) Hyperparameter study (bubble chart: size = latency, color = ). (h) Computational efficiency across hardware devices.

The regression results (d) build on this strength by showing that the system can accurately predict quantitative measures such as probability of failure, reliability index, and ultimate capacity. The values align closely with ground truth, with R2 consistently near 1.0, proving the model’s ability to capture complex structural behavior. More importantly, the compliance rates in (e) confirm that predictions meet established safety thresholds in nearly every case, with reliability index () above 3.5, failure probability below 10−3, and demand-to-capacity ratio under 1.0. These findings, reinforced by the five-fold cross-validation in (f), highlight the framework’s consistency and reliability across different data splits, making it robust for practical engineering use. Figure 3g,h illustrate how the system balances predictive accuracy with computational efficiency. The hyperparameter study demonstrates the importance of careful tuning, as optimal configurations deliver higher accuracy with lower error and latency. The hardware benchmarking results then confirm that the model can run efficiently on GPUs, CPUs, and even resource-limited edge devices, with prediction times of just a few milliseconds and small memory requirements. This combination of accuracy, safety compliance, and speed makes the framework both powerful and practical, offering engineers a dependable tool for real-time monitoring and structural optimization.

5. Comparison with Related Works

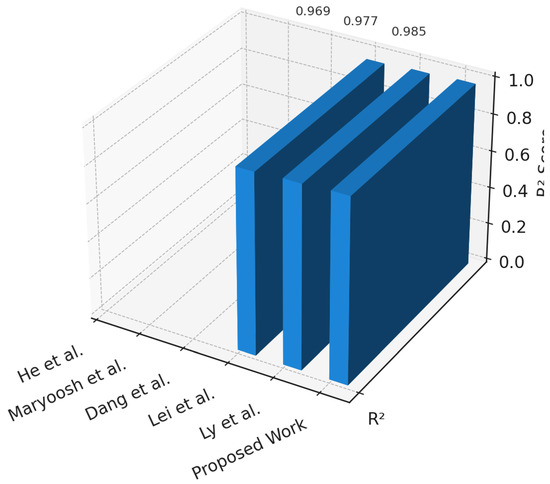

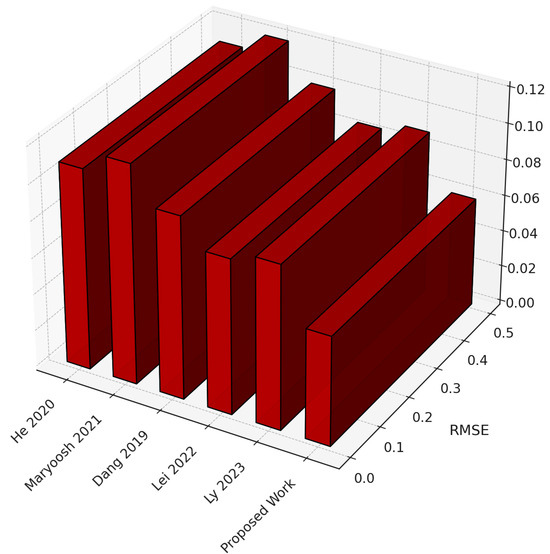

In order to situate our proposed framework within the broader research landscape, we critically compare it with recent state-of-the-art studies that address structural reliability prediction, damage identification, and hybrid machine learning approaches. Table 17 summarizes the methodologies, datasets, evaluation metrics, and key limitations of existing works, while also highlighting how our study addresses the identified gaps. Although prior research has made significant contributions in applying hybrid AI techniques for tasks such as shear strength prediction, damage classification, and capacity estimation, most studies remain constrained to either classification or regression, neglecting reliability-oriented measures such as probability of failure, reliability index, or ultimate capacity. Furthermore, few works embed physics-informed constraints or validate deployment on resource-constrained environments. By integrating classification and regression within a dual-head hybrid framework, embedding physics-informed penalties, and validating quantized deployment for edge feasibility, our approach advances beyond existing efforts and provides a more comprehensive and practically deployable solution for structural reliability assessment.

Table 17.

Comparison of Related Studies with Our Proposed Work.

The study by Lei et al. [22] highlights the benefit of metaheuristic-optimized neural networks, where SMA prevented local minima in MLP training and enhanced predictive accuracy for shear strength. However, the framework remained limited to regression-only modeling without addressing probability of failure, reliability indices, or ultimate capacity. Moreover, it lacked multi-task learning capability, operating purely as a single regression model without classification or reliability estimation. No real-time or edge-level performance evaluation was reported, and compliance with engineering code requirements was not considered. Additionally, the SMA–MLP architecture lacked physical constraint embedding or any mechanism to ensure equilibrium consistency and mechanical compliance during learning, and no validation was performed for quantized or low-latency deployment. In contrast, our proposed framework integrates both classification and regression outputs under a unified multi-task architecture, embedding physics-informed constraints within the loss structure, ensuring engineering-code compliance, and verifying inference stability through edge deployment benchmarking.

The work of He et al. [23] demonstrated the value of time–frequency decomposition and correlation-based feature selection when combined with CNN for structural damage classification. The method achieved high accuracy but was limited to single-task classification, lacking reliability quantification. It did not implement a multi-task structure or perform joint regression of reliability indices. No latency, throughput, or energy efficiency tests were performed to evaluate real-time readiness, and the model did not incorporate compliance or constraint-based safety verification. Additionally, it lacked physics-informed penalties and equilibrium consistency terms, and no deployment analysis was conducted under resource-constrained conditions. Motivated by this limitation, we propose a dual-head architecture capable of both classification and regression, enabling multi-task learning with physics-guided regularization, verified for real-time edge inference (latency < 3 ms) and compliance with engineering safety codes.

Maryoosh et al. [24] presented a hybrid handcrafted–deep learning approach for bridge crack detection, which achieved near-perfect classification accuracy. However, it focused solely on image-based classification, without regression for structural reliability or capacity prediction. This single-task setup lacked multi-task adaptability and offered no analysis of model behavior in real-time or embedded environments. It also omitted any compliance framework with physical or safety codes. Furthermore, the model did not integrate physics-informed constraint enforcement or edge-level deployment validation, restricting its practical usability in monitoring systems. By contrast, our framework generalizes to multi-task learning that jointly handles reliability regression and classification, embedding code-based limit-state physics constraints and validating edge deployment efficiency through quantization-aware optimization, thereby ensuring real-time, compliant, and interpretable performance.

The hybrid CNN–LSTM framework proposed by Dang et al. [25] effectively combined signal processing and deep neural networks, improving robustness for damage detection even under noise. However, the method remained confined to detection and localization, without addressing multi-task prediction or probability-based reliability assessment. It lacked any multi-task integration for combined classification and regression, and real-time deployability was neither measured nor optimized. Compliance with mechanical or design codes was also not discussed. No physics-informed constraints or quantized edge verifications were implemented, which limited real-world scalability. In contrast, our model extends these capabilities by jointly performing classification and regression under physics-based penalty embedding, achieving verified real-time edge performance, low-latency inference, and compliance with structural safety and reliability standards.

Ly et al. [26] introduced hybrid computational models optimized via genetic and firefly algorithms to predict the ultimate shear capacity of SFRC beams. While accurate, their models were purely regression-based and did not include classification or real-time performance validation. The absence of a multi-task design limited generalization across tasks, and no timing, latency, or hardware efficiency assessments were provided. The framework also lacked physics-informed consistency and code-compliance verification. Similarly, no mechanism was implemented to validate model robustness under quantized or embedded deployment scenarios. Our proposed framework advances this direction by integrating classification and regression in a unified multi-task structure, embedding physics-informed penalties, achieving sub-3 ms edge inference latency, and ensuring full compliance with engineering reliability codes.