1. Introduction

Skewed and heavy-tailed data are prevalent in various applied domains, including econometrics, environmental science, and risk analysis. Income distributions, housing prices, and insurance claims often display asymmetry and excess kurtosis; the tail behavior encodes meaningful extremes, such as financial losses or contaminant spikes, that should not be dismissed as outliers; see, for example, Ibragimov et al. [

1], Guo [

2], Cortés et al. [

3], and Ahmad et al. [

4].

A natural starting point for modeling asymmetry is the Skew-normal distribution introduced by Azzalini [

5] (see also [

6]). By augmenting the normal distribution with a skewness parameter, the Skew-normal preserves analytical tractability while allowing for controlled departures from symmetry. However, because the Skew-normal remains light-tailed, it is ill-suited to settings where leptokurtosis is intrinsic to the data-generating process.

To address heavy tails alongside asymmetry, the Skew-

t family extends the

t distribution by introducing a skewness parameter. An influential approach views Skew-

t random variables as scale mixtures of Skew-normal and Chi-square variables [

5,

7], a perspective adopted and elaborated by several authors, including Hasan et al. [

8]. Related extensions, such as extended Skew-

t (EST) and alternative parameterizations, further enhance the modeling flexibility (see, for example, [

9]). Empirically, Skew-

t models have seen broad application, from financial time series and risk assessment to environmental monitoring and robust analysis under truncation or censoring [

10,

11]. Non-central variants expand the toolkit and have been studied in detail, with their properties and use cases documented in Hasan et al. [

8] and Hasan [

12].

Despite this progress, the assessment of the Skew-t model remains essential. In practice, misspecification of tail weight or asymmetry can distort inference on extremes, dependence, and risk. This motivates rigorous goodness-of-fit (GoF) procedures tailored to Skew-t families—methods that can diagnostically test statistical adequacy against alternatives that differ in tail behavior, asymmetry, or both.

In this paper, we develop an energy-based goodness-of-fit test for Azzalini’s standard Skew-

t distribution proposed in Azzalini and Capitanio [

6] and defined as a random variable with probability density function (PDF) that takes the following form:

where

g and

G are the PDF and the cumulative CDF of the standard

t distribution. The parameters

and

are referred to as the skewness parameter and the degrees of freedom, respectively. We will denote this density by

. The special case for

reduces to the standard Student

t distribution with

degrees of freedom. The CDF of this Skew-

t distribution does not have a closed form.

A scale–location extension of this definition has been proposed by adding a location parameter

and a scale parameter

by replacing

x in Equation (1) by

. The expected value of the scale–location Skew-

t variable can be obtained by

where

,

, and

. The reader is referred to Azzalini and Capitanio [

6,

13] for more details on the theoretical properties and alternative parameterizations of the Skew-

t distribution. For simplicity, we will refer to Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution as the Skew-

t distribution for the remainder of this paper unless otherwise stated.

Without loss of generality, we will focus on the standard Skew-

t distribution in our construction of the goodness-of-fit test, since an arbitrary four-parameter Skew-

t density can be converted to the standard one via a linear transformation.

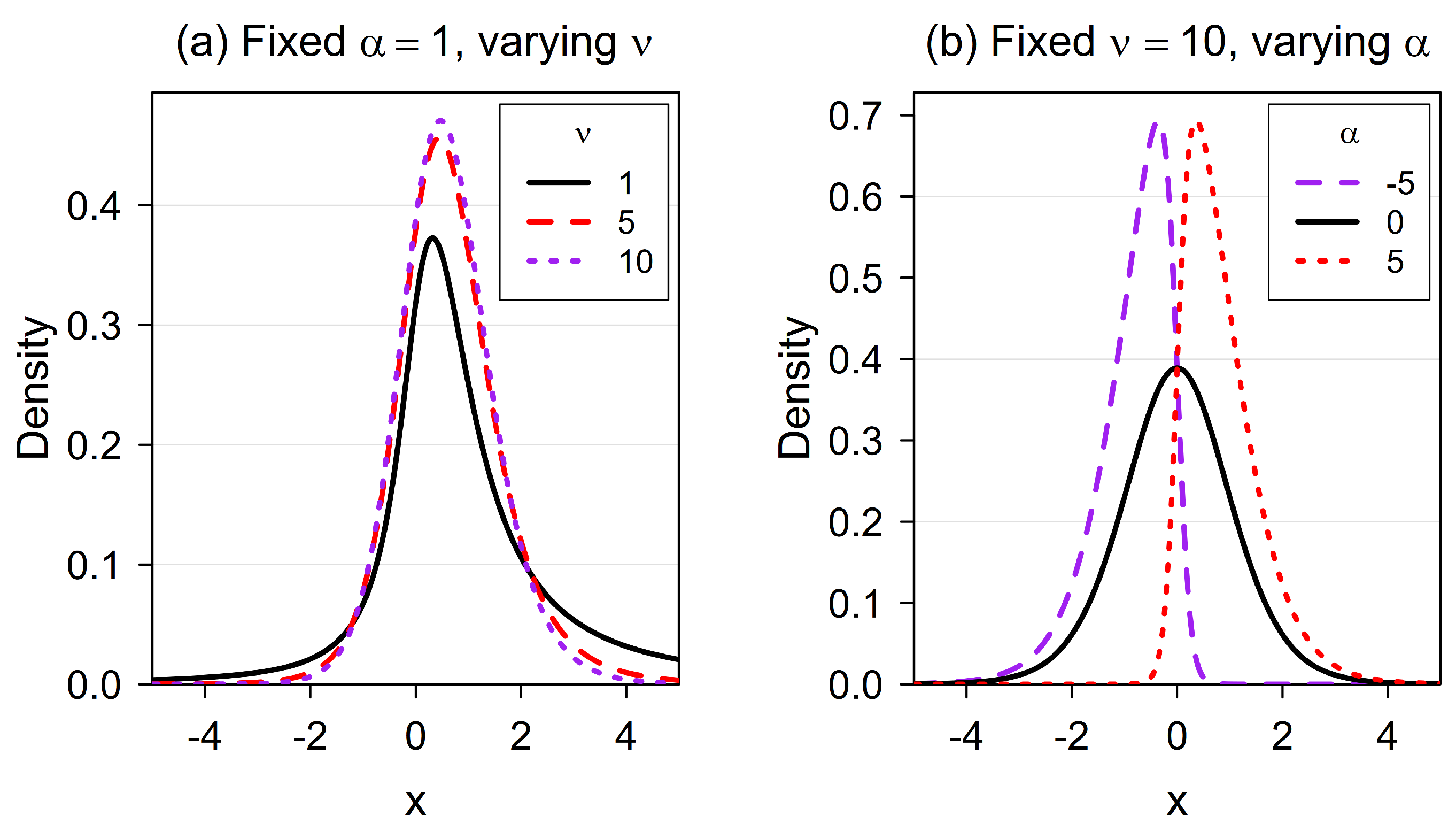

Figure 1 provides density curves of the standard Skew-

t distribution for varying degrees of freedom (

) when the skewness parameter

is held fixed. This illustrates the role of each parameter as the parameter

controls the skewness of the density, and the parameter

controls the thickness of the tail.

There is limited research on the goodness-of-fit test for Azzalini’s Skew-

t distributions, except those based on empirical distribution functions (EDFs), such as Kolmogorov–Sminorv, Cramer–von-Mises, etc., discussed and modified in [

14,

15]. Recently, Maghami and Bahrami [

16] proposed a goodness-of-fit test for Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution based on the correlation coefficient (

r). Most studies related to Skew-

t distributions focus on properties, extensions, generalizations, change point analysis, and applications, for example, [

12,

17,

18,

19], among many others. To address this research gap, we develop an energy-based goodness-of-fit test for the Skew-

t distribution. Our test leverages the well-established properties of energy-based testing to achieve higher power for any given sample size and parameter combination

and

.

In this article, we propose a new one-sample (univariate) energy goodness-of-fit test based on energy statistics proposed by [

20,

21]. In the most recent work, Refs. [

22,

23,

24] proposed goodness-of-fit tests based on energy statistics for Skew-normal, Inverse Gaussian, and Lindley distributions, respectively. For a given sequence of independent random variables of size

n and with a cdf

G, the test statistic based on energy statistics will reject the null hypothesis that

for large values of the test statistic. If the null distribution,

F, and the given data come from the same underlying distribution

G, then the values of the test statistic are expected to be smaller. Furthermore, there have been numerous studies involving energy statistics such as testing for multivariate normality [

25,

26], testing for equality of distributions [

27,

28], one-sample goodness-of-fit tests [

22,

24,

29,

30], and change point analysis [

31,

32,

33,

34], among many others.

The energy distance is a statistical distance between the distributions of random vectors that characterizes the equality of distributions; see, for example, [

21,

29,

35]. The concept of energy statistics described by Sźekely [

21] is based on the notion of Newton’s gravitational potential energy, which is a function of the distance between two bodies. The idea of energy statistics, therefore, is to consider statistical observations as heavenly bodies governed by a statistical potential energy, which is zero if and only if an underlying statistical null hypothesis is true, see, for example, [

29,

36].

Definition 1.

Sźekely and Rizzo [35] defined the energy distance between distributions of two independent and univariate random samples X and Y with finite expectations as follows: , , and equality holds if and only if X and Y are identically distributed.

1.1. Existence and Uniqueness of the MLEs for Azzalini’s Skew-t Distribution

Azzalini and Genton [

37] presented a detailed discussion of the existence and uniqueness of the maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) for Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution. They concluded that the distribution is generally robust, with the profile log-likelihood for the skewness parameter

being unimodal and free of stationary points at

. The Fisher information matrix remains non-singular for all finite degrees of freedom, ensuring the existence and uniqueness of the MLE under regular conditions. Simulation studies confirm that the MLEs for skewness and tail parameters (degrees of freedom) are well-behaved for moderate to large samples, while likelihood-based adjustments such as the deviance approach can mitigate rare boundary issues in small samples (see Azzalini and Genton [

37] and Azzalini and Capitanio [

6] for more details).

Recent advances have addressed the instability and divergence of the MLE for

in small samples. Azzalini and Arellano-Valle [

38] introduced a penalized log-likelihood framework that ensures robust, finite, and unique estimates for

, even in small or multivariate settings. In our computations, we adopted this penalized likelihood approach to enhance robustness and avoid instability in parameter estimation for the Skew-

t family.

1.2. Motivation and Scientific Contribution

The Skew-

t distribution stands out as a flexible and reliable tool for modeling asymmetric and heavy-tailed data. Its regular profile likelihood and robust MLE properties make it especially suitable for general-purpose robust inference in both univariate and multivariate settings. In this paper, we propose a procedure that is superior for the goodness-of-fit test for the Skew-

t distribution based on energy distance statistics (Sźekely and Rizzo [

35]) and the definition of Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution (Azzalini and Capitanio [

13]). Unlike the proposed method based on energy statistics, many existing methods depend on the distribution function of random variables. Energy statistic-based tests have been shown to be typically more powerful against general alternatives than corresponding tests based on classical statistics (non-energy type), such as Kormogorov–Smirnov, correlation, Anderson–Darling, and Cramer–von-Mises. In addition, energy statistic-based tests have an invariance property with respect to any distance-preserving transformation of the dataset; see [

29,

33,

36]. This enables studies that involve energy statistics to be extended to multivariate and high-dimensional settings.

In

Section 2 of this article, we introduce a test procedure based on energy statistics for the goodness of fit of Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution and discuss its theoretical properties. We perform various simulations in

Section 3 to compare the approach with other existing methods. In

Section 4, we apply our method to three case studies. The conclusions are provided in

Section 5. Limitations and future research are discussed in

Section 6.

2. Proposed Energy-Based Goodness-of-Fit Test

We propose a one-sample univariate goodness-of-fit test based on the energy statistics proposed by [

26,

35] for the Skew-

t distribution. The null hypothesis is that the data

X follow the null distribution

which is a Skew-

t distribution, against the alternative that the Skew-

t distribution is a poor fit for the data.

Definition 2.

Let be a random sample from a univariate population with distribution F and let be the observed values of the random variables in the sample. Then, the one-sample energy statistic goodness-of-fit test for testing the hypothesis vs is defined as follows.where X and are independent and identically distributed variables with distribution , and the expectations are taken with respect to the null distribution . The null hypothesis

is rejected for large values of the test statistic

. Under the null hypothesis, the limiting distribution of

is a quadratic quantity of the form

such that

are i.i.d. standard normal random variables and

are nonnegative constants that depend on the null distribution. Thus, the goodness-of-fit test can be implemented by finding the constants

. In practice, this could be difficult, and we therefore resort to the use of empirical critical values of

so that

This fact is guaranteed since the test based on

is a consistent goodness-of-fit test, see, for example, Sźekely and Rizzo [

26] and Móri et al. [

25].

The goodness-of-fit test statistic based on energy statistics is dependent on the derivation of the expected values of and where X and are independent and identically distributed random variables from the null distribution

Proposition 1.

Let where is the standard Skew-t density defined in Equation (1). Then, for any fixed where is the CDF of the standard Skew-t distribution. Proof of Proposition 1. Let

. Then, for every fixed real number

x, we have

where the integral term can be numerically evaluated in R (version 4.4.2) using the command

dst() available in the Azzalini

sn package. □

Sometimes the derivation of the second term in Equation (

4) may not be analytically feasible and, therefore, we can use the following approximation as suggested in [

22].

Proposition 2

(Quantile-based Approximation)

. Let X and be independent and identically distributed random variables with a well-defined cumulative distribution function, . Given that the quantile or inverse CDF function of X exists, we have the following. where m is the number of equally sized sub-intervals of and is chosen from the ith sub-interval. It is worth noting that Proposition 2 applies to all distribution functions. Proof. This proof is provided by Opperman and Ning [

22]. □

3. Simulations and Results

This section presents a simulation-based assessment of the proposed goodness-of-fit (GoF) test for Azzalini’s Skew-t distribution, built upon the energy distance framework. We evaluated the test performance on varying values of the skewness parameter () and degrees of freedom (). Simulations are conducted under both the null hypothesis and multiple alternative distributions, and type I error and empirical power are computed.

In this simulation study, we calculate two key quantities. The size of the test (type I error) and the empirical power (1-type II error). We used R (R version 4.4.2) and the

sn package,

https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sn/refman/sn.html (accessed on 21 November 2025), to carry out the simulations. Due to the complexity of repeatedly evaluating the Skew-

t CDF and performing numerical integration, all simulations were parallelized using the

foreach and

doParallel R packages. The simulations were distributed across 11 processor cores, significantly accelerating the test’s evaluation across various scenarios. The programming code is too lengthy to include in the paper. However, it can be obtained by contacting the authors via email.

3.1. The Univariate Energy Test Statistic

The univariate energy test statistic is derived from the expected pairwise distances between observations and a reference Skew-

t distribution. We used the standard Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution in our development of the test statistic and rely on standardization to convert an arbitrary Skew-

t to the standard one before applying the test. Let

be the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of Azzalini’s standard Skew-

t distribution with parameter vector

. The test statistic for a sample

is

where

,

, and

m is the number of equally sized sub-intervals of

and

is chosen from the

ith sub-interval.

This expression is approximated using the following.

A term involving the integral of up to each data point.

A quantile-based approximation for the inter-distributional expectation .

A linear-order statistic approximation for the within-sample expectation .

According to Rizzo [

20], the last term of the test statistic

in Equation (

4) can be linearized in order to reduce the computational complexity of the test from

to

, which is useful during extensive simulations and applications. Let

be the ordered sample of the random sample

. Then, the linearization of the double sum of the test

is given as

3.2. Critical Value Simulation Under Varying and

In this section, we conduct a simulation study to estimate the critical values for the energy-based goodness-of-fit test under Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution. The critical value simulations are summarized in

Table 1. We selected degrees of freedom

to account for different levels of heavy tail behavior and skewness coefficient

to cover the three possible scenarios of right skew, symmetry, and left skew. We used 5000 replicates in this study, with sample sizes

.

Table 2 presents the results of the type I error simulations, illustrating that the empirical values are very close to the theoretical value of 0.05, regardless of the sample size and the parameter values chosen for each sample.

3.3. Type I Error Control

To explore the sensitivity of the test, we vary the skewness parameter and the degrees of freedom . For each combination of , we

Generate samples of size from the Skew-t distribution with parameters ;

Estimate the parameters using the maximum penalized likelihood method available in the sn package;

Standardize the data to the standard Skew-

t random variables and compute the energy goodness-of-fit statistic using the formula in Equation (

7);

Determine the empirical 95th percentile critical value under the null hypothesis.

The empirical type I error is then evaluated across different parameter settings to confirm robustness.

Table 2 shows that the proposed energy-based test maintained the nominal significance level in all the configurations examined. For

, the empirical type I error was close to 0.05, although slightly higher in extreme skewness or low degrees of freedom. As the sample size increased, the test stabilized and was consistently aligned with the theoretical level.

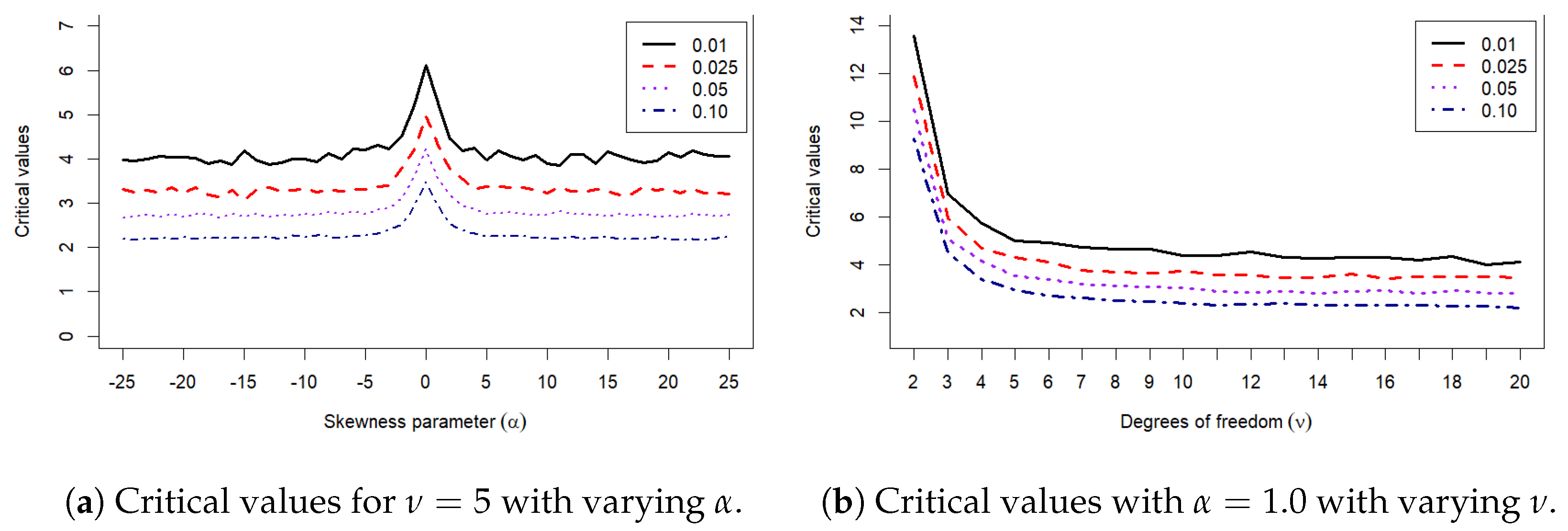

Figure 2a shows critical values with a varying skewness parameter,

, for

and sample size

For each selected level of significance (

), the critical values seem to stabilize as the skewness parameter

progresses further from 0. At

, we see a dramatic increase in the simulated critical value. Note that Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution reduces to the classic Student

t distribution when

. In this special case, Azzalini’s skewness

t might be an overfitting model for the data, as the skewness parameter is no longer needed and the Student

t distribution is a better fit. If

, the critical value stabilizes. This implies that for a fixed predetermined confidence level, the actual value of the skewness parameter

has little to no effect on the critical value as long as

; in other words, the data exhibit a noticeable skewness.

Figure 2b shows critical values with varying

for

and sample size

When the degrees of freedom

, Azzalini’s Skew-

t distribution reduces to Cauchy’s distribution, and this is why we see higher critical values for the goodness-of-fit test. As degrees of freedom increase

, the critical values for a predetermined significance level stabilize as depicted by the nearly horizontal lines in

Figure 2b.

3.4. Power Analysis Under Various Alternatives

The simulation findings demonstrate the superior statistical power of the proposed energy-based goodness-of-fit, , test statistic compared to several established goodness-of-fit tests, including the Anderson–Darling (A-D), Cramér–von Mises (CvM), Watson, Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S), and Kuiper tests. The analysis was carried out on various alternative distributions with sample sizes (n) of 50, 100, 150, and 200.

For power studies, samples are drawn from alternative distributions that deviate from Azzalini’s Skew-t distribution family. These include the following:

Chi-square: This is asymmetric and heavy-tailed.

StudentorGosset’s t: This is symmetric and heavy-tailed.

Exponential: This has a lighter tail and positive skew.

SHASH: The SHASH (Sinh-Arcsinh) distribution discussed in [

39] is a highly flexible statistical distribution defined by four parameters that separately control the location, scale, skewness, and kurtosis of a variable.

Generalized t (GT): This is to assess sensitivity to misspecification.

Log-normal: This is asymmetric and heavy-tailed.

KwCWG: This is the Kumaraswamy Complementary Weibull geometric probability distribution. This is a five-parameter density that is well-suited for modeling skewed data with heavy tails.

The empirical power of our proposed test can thus be obtained using the following algorithm.

Obtain the critical value under the Skew-

t distribution assumption with parameters

as explained in

Section 3.3.

Generate a dataset from the desired alternative distribution.

Process the data as if they were from a Skew-t distribution and estimate the parameters using the maximum penalized likelihood method available in the sn package.

Standardize the data to the standard Skew-

t random variables

, then compute the energy goodness-of-fit statistic using Equation (

7).

Based on the energy goodness-of-fit statistic and the critical value in Step 1, determine whether or not the null hypothesis is rejected.

Repeat Steps 1 through 5 for B times and the empirical power is calculated as the proportion of times the null is rejected across repetitions.

The empirical powers for the classical EDF (non-energy) tests considered in this study are also obtained in a similar manner.

Table 3 summarizes the results of the power comparison simulations. For each case, the bold font indicates the highest power achieved at the combination of the sample size and alternative distribution displayed in the row heading, for each test shown in the column heading.

3.5. Superior Performance of the Test

As illustrated in

Table 3, across

all scenarios, the energy-based test exhibited the highest power. This dominance is particularly evident in cases of heavy-tailed and skewed distributions.

For the Log-normal () distribution, the test achieved a power of 0.9701 at a sample size of just 50, far exceeding the next best test, Watson’s test, which had a power of 0.3988.

Against the GT () distribution, the test reached a power of 1.0000 for sample sizes of 150 and 200, indicating perfect detection in the simulation.

For the Exponential (Exp(1)) distribution, the power of ranged from 0.8413 to 0.9848, consistently outperforming all other competitors.

For the KwCWG distribution, the power of the test ranged from 0.0845 to 0.1170, with the energy test outperforming the other tests in three out of the four sample size settings. The overall small power in this comparison indicates that the tests are having difficulty distinguishing between the two distributions. This is expected as both distributions are suitable to model skewness and heavy tails. However, since the Skew-t distribution uses four parameters instead of five, it is more parsimonious.

The K−S and A−D tests performed poorly in almost all scenarios, especially for skewed and heavy-tailed data. The correlation-based test was competitive but slightly less sensitive to deviations in kurtosis. The energy test consistently ranked the best performing method in all conditions except a single case for the KwCWG distribution.

3.6. Effect of Sample Size and Parameters

As anticipated, the power for all tests increased with the sample size. For example, in the case of the SHASH distribution, the power of the test rose from 0.5734 for to 0.6749 for . It should be noted that for the standard distribution, which is a special case of the Skew-t distribution when the skewness parameter , all tests showed very low power. The highest power achieved was only 0.2790 by the test at . This suggests that all tests have difficulty distinguishing the two distributions, although the test still has a relative advantage. The proposed energy-based test achieved the highest power under conditions of high skewness () and low degrees of freedom (). As increased, the power decreased slightly. This decrease in power is likely because the Skew-t distribution converges to the Skew-normal family as degrees of freedom, , making it harder to distinguish the Skew-normal from the Skew-t distribution as the degrees of freedom increase.

3.7. Summary

In summary, the simulation results provide strong evidence that the energy-based statistic, , is a more powerful goodness-of-fit test than the other methods considered in the study, especially for non-normal distributions with skewness or heavy tails. In general, the energy-based GoF test for the Skew-t distribution demonstrates

Robust control of type I error;

Superior power in a wide range of alternatives;

Flexibility for skewed, heavy-tailed, and multi-modal data.

Its simplicity and effectiveness make it a promising tool for model validation in applied settings. Although the proposed method relies on a Monte Carlo approximation for expectation terms, the computational cost is manageable and can be parallelized. The use of linearized summation and pre-simulated reference distributions further improves efficiency.

4. Real Data Applications

To evaluate the practical utility of the proposed test, we present three case studies with real-world datasets. For each case study, we use the penalized MLE to fit the data, compare the fit using information criteria, visually assess goodness-of-fit using histograms of the original data and superimposed density curves, and compare the CDF of the fitted Skew-t model to the empirical density curve. We compute p-values for the likelihood ratio test to illustrate that the Skew-t distribution provides a better fit to the data than the nested models (normal, Skew-Cauchy, and Skew-normal). We finally present the test statistic and p-value for our proposed energy-based test, along with those for the selected comparator tests.

Since the underlying distributions of these datasets are not exactly known in advance, we use the bootstrap algorithm to determine whether they come from Azzalini’s Skew-t distribution. The bootstrap procedure is used to approximate the p-value of the proposed test as given below.

Fit the real data with an Azzalini’s Skew-t distribution in Equation (1) and obtain the maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) of , and from the Azzalini’s sn package available in R (version 4.4.2).

Use the formula in Equation (

7) to calculate the energy goodness-of-fit statistic of the standardized data and denote it

.

Simulate , a random sample of size from the Azzalini Skew-t distribution with parameters specified as , and that were obtained in Step 1.

Standardize the data with the standard Skew-

t distribution and compute the energy goodness-of-fit statistic for the simulated data using the formula in Equation (

7) and denote this value as

.

Repeat this process for B times and obtain B energy goodness-of-fit statistics and denote them by .

The bootstrap

p-value is therefore approximated as

where

is an indicator function that takes the value of one when

and zero otherwise.

A similar procedure was applied for classical (EDF) tests to approximate their respective bootstrap p-values.

4.1. Case Study 1

The first dataset represents the body mass index (BMI) of 102 male Australian athletes (Cook and Weisberg [

40]). The dataset is provided in

Table A1 and is available in the

dr package in R. This dataset was previously analyzed by Maghami and Bahrami [

16], who used the correlation coefficient as a measure of goodness of fit for the Skew-

t distribution. The dataset exhibits moderate skewness and potential heavy tails, making it an ideal candidate for Skew-

t modeling.

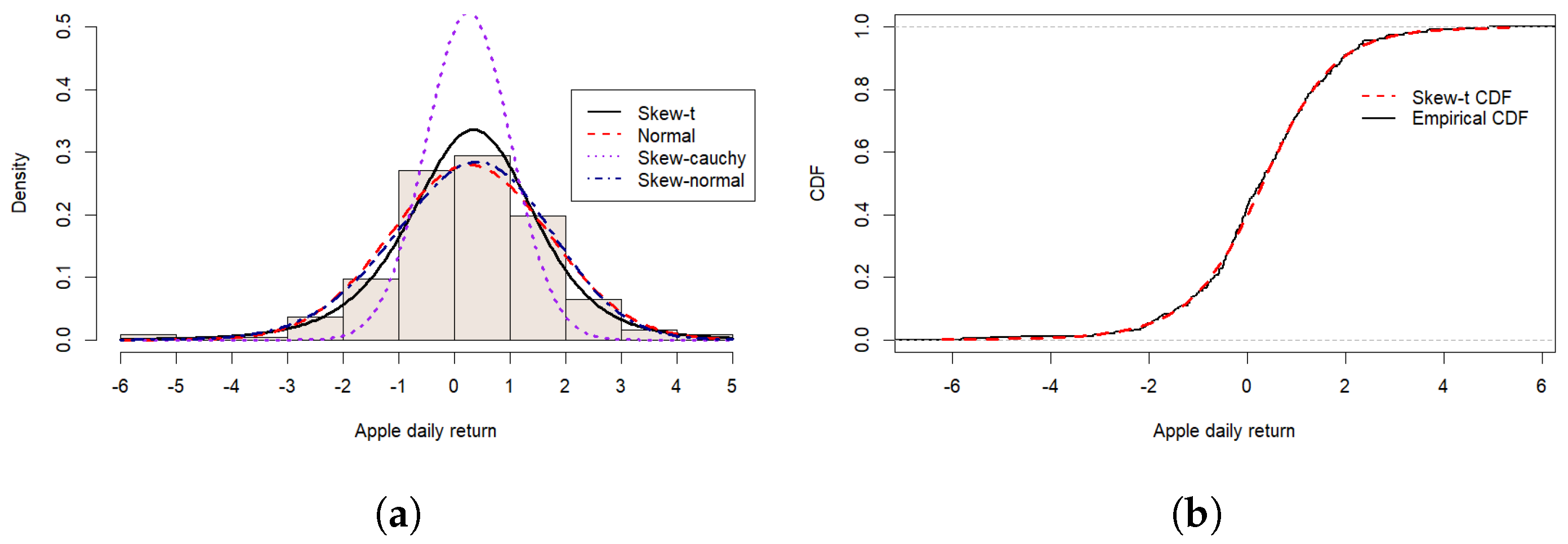

4.2. Case Study 2

The second dataset consists of Apple Inc.’s closing prices. This is the daily rate of returns for Apple stock Macrotrends [

41]. This dataset was used in the analysis by [

19] to detect structural changes in the distribution using the MIC-based method. The dataset is obtained from [

41], which provides historical stock price data. We limited the data to the range from

31 January 2019 to 24 January 2020 to avoid the heterogeneity introduced by change points. The stock price shows a general upward trend with some noticeable fluctuations. Given that stock prices exhibit time dependence, we transform the raw closing prices,

, into daily returns, defined as

This transformation allows us to analyze relative price changes rather than absolute levels. The resulting data consist of 248 daily return observations, which we suspect to follow a Skew-

t distribution. The filtered and transformed data are available in

Table A2 in

Appendix A.

4.3. Case Study 3

The third case study is the daily returns of the Dow Jones Industrial Average stock over the period of one year, from 1 November 2024 to 31 October 2025. This data is available in the

Tidyquant package in R (version 4.4.2). Stock prices have frequently fluctuated this year due to tariff-related volatility, so we expect the data to exhibit heavy tails and outliers, making it an ideal candidate for Skew-

t distributions. The data are then transformed using Equation (

9) to correct for the dependence between observations. The transformed data consists of 249 observations and is available in

Table A3 in

Appendix A.

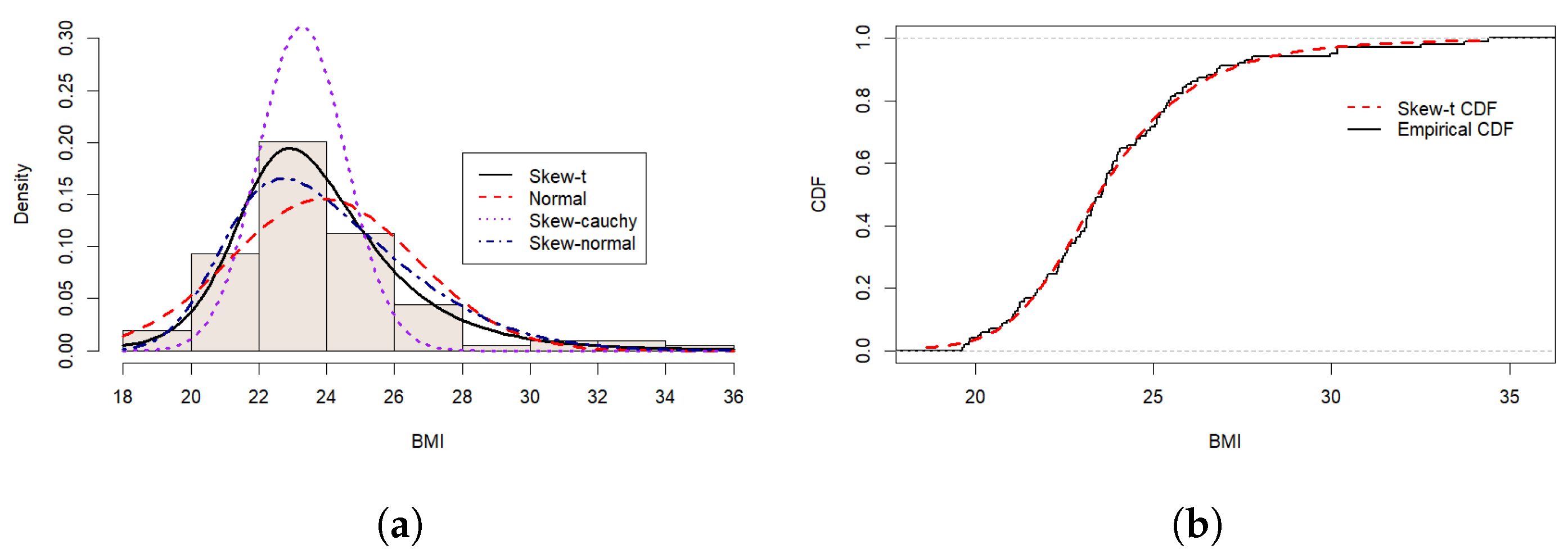

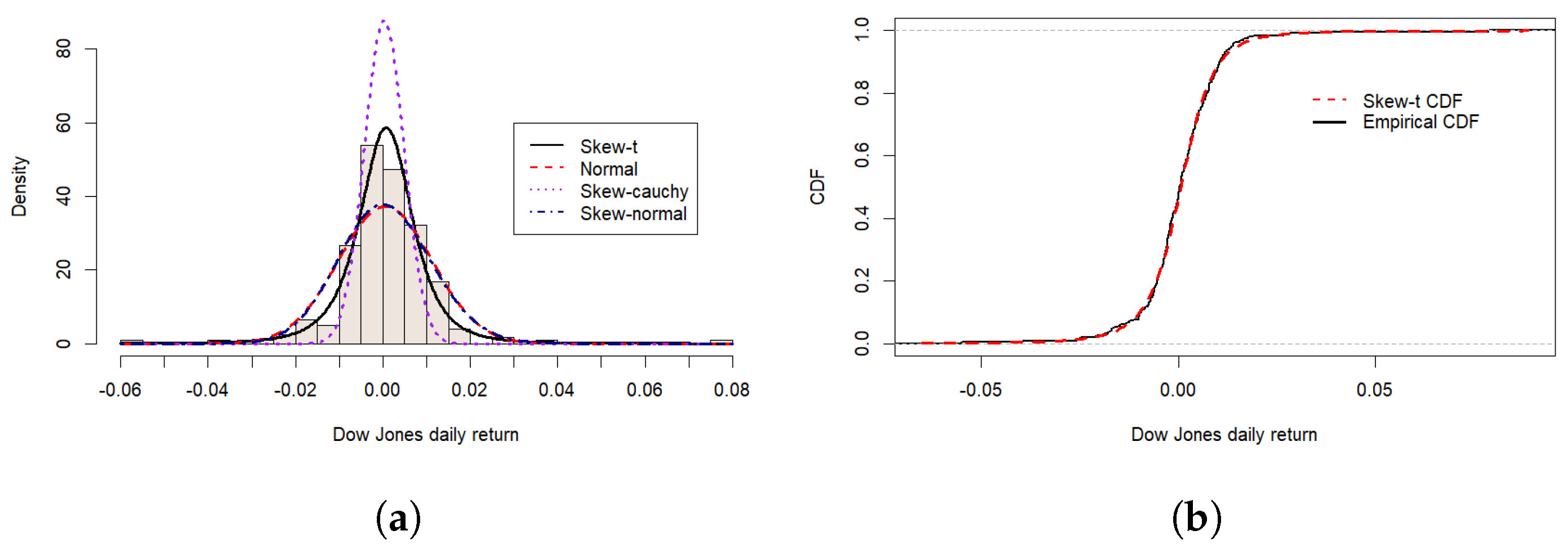

4.4. Model Fitting

The histograms in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 reveal skewness; therefore, distributions such as the Skew-

t, Skew-normal, Skew-Cauchy, and normal distributions are good candidates for modeling these datasets. Parameter estimation is conducted using the penalized maximum likelihood method. The results of the penalized maximum likelihood estimates (PMLEs), log-likelihood (LogL), Akaike information criterion (AIC), Schwarz information criterion (SIC), and corresponding

p-value for the likelihood ratio test (LRT) against the Skew-

t distribution are reported in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

In all datasets, the Skew-t distribution yielded the lowest AIC values, indicating a better overall fit. Surprisingly, the Skew-normal distribution gave a lower SIC value for the body mass index (BMI) dataset. In addition, the associated p-value (0.0502) for the likelihood ratio test (LRT) indicates some evidence that the data may follow Skew-t distribution. Other likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) yielded small p-values, suggesting strong evidence in favor of Skew-t distribution.

In the first dataset (BMI), our proposed test statistic is 1.7109, with a corresponding p-value of 0.5840, supporting the assertion that the BMI data follow the Skew-t distribution. Classical tests considered in the study also supported the null hypothesis that body mass index (BMI) data can be modeled using the Skew-t distribution. In the second dataset, the test statistic for the proposed procedure is 3.9635, and the corresponding p-value is 0.5473. These results support the fact that the data follow the Skew-t distribution. Similar results are observed for the classical (EDF) tests, which suggest that the Skew-t distribution is an adequate model for the data. For the last dataset, the proposed test statistic is and its corresponding p-value is 0.5012, indicating that the Dow Jones daily returns follow a Skew-t distribution. We observe a similar conclusion from the classical (EDF) tests.

The results for all datasets are summarized in

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9. Furthermore, density estimates and empirical cumulative functions suggest that the Skew-

t distribution fits the datasets adequately, as shown in

Figure 3a,b for the BMI dataset,

Figure 4a,b for the Apple stock prices dataset, and

Figure 5a,b for the Dow Jones daily returns data, respectively.

4.5. Discussion

In the three case studies we presented in this article, the Skew-

t distribution fits the data adequately and has the lowest AIC value among the distributions. This assertion is also well confirmed by the density and empirical CDF estimates as shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. Through simulations, 2000 bootstrap samples are drawn from the Skew-

t distribution with the parameter estimates specified in

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9, and the approximate

p-values of the proposed test for the three case studies are obtained as 0.5840, 0.5473, and 0.5012, respectively. We therefore fail to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the three datasets can be modeled with the Skew-

t distribution.

The three case studies highlight the energy-based GOF test’s ability to validate Skew-t modeling in real-world scenarios, particularly when skewness and heavy tails are present. In addition, they illustrate the utility of energy-based approaches in detecting misfits in a range of candidate models.