Abstract

Despite the success of reinforcement learning (RL), the common assumption of online interaction prevents its widespread adoption. Offline RL has emerged as an alternative that learns a policy from precollected data. However, this learning paradigm introduces a new challenge called “distributional shift”, degrading the performance of the policy when evaluated on out-of-distribution (OOD) scenarios (i.e., outside of the training data). Most existing works resolve this by policy regularization to optimize a policy within the support of the data. However, this overlooks the potential for high-reward regions outside of the data. This motivates offline policy optimization that is capable of finding high-reward regions outside of the data. In this paper, we devise a causality-based model architecture to accurately capture the OOD scenarios wherein the policy can be optimized without performance degradation. Specifically, we adapt causal normalizing flows (CNFs) to learn the transition dynamics and reward function for data generation and augmentation in offline policy learning. Based on the physics-based qualitative causal graph and precollected data, we develop a model-based offline OOD-adapting causal RL (MOOD-CRL) algorithm to learn the quantitative structural causal model. Consequently, MOOD-CRL can exercise counterfactual reasoning for sequential decision-making, revealing a high potential for OOD adaptation. The effectiveness is validated through extensive empirical evaluations with ablations including data quality and algorithmic sensitivity. Our results show that MOOD-CRL achieves comparable results with its online counterparts and consistently outperforms state-of-the-art model-free and model-based baselines by a significant margin.

MSC:

37M10

1. Introduction

While reinforcement learning (RL) has achieved notable success in addressing sequential decision-making challenges across diverse domains, its deployment in real-world applications poses significant challenges due to the need for active and online interaction with the environments during policy training. These challenges have motivated the use of large-scale, precollected data that are readily available in practice. Specifically, offline RL aims to learn a policy directly from data rather than through online interaction. Yet, traditional offline RL encounters a significant challenge known as distributional shift. This shift denotes the difference in state-action visitation of the learning policy and a behavior policy used to generate the data. Specifically, the distributional shift occurs when the agent explores or is evaluated on a state that is not included in the precollected data, and it degrades the performance of the learning policy.

Since distributional shift is a central challenge in offline RL, most of the prior research has focused on mitigating its effects. One predominant way is through the policy regularization that constrains the policy to stay within the support of the data [,]. However, the regularized policy may achieve only a suboptimal performance when the given data is suboptimal. Hence, a novel approach that is orthogonal to most existing works for offline RL is to learn a policy without the regularization through an accurate policy evaluation beyond the data support, i.e., out-of-distribution (OOD) adaptation.

Our work aims to enable the OOD adaptation in learning policy through a causality-based approach []. Specifically, we learn a causal model—capable of counterfactual reasoning—that enables accurate policy evaluation in OOD regions. We assume that a causal graph is provided as prior knowledge to capture the qualitative physical laws of the environment (e.g., Newton’s second law). In robotics and autonomous systems, such causal graphs can often be derived from qualitative physics, making this assumption largely non-restrictive. Using this structure, we learn the transition dynamics and reward function of the environment based on causal relationships rather than spurious correlations in the data [,].

We adopt causal normalizing flows (CNFs) as a causal model, which enables causal inference with the normalizing flows (NFs) architecture. CNFs enable accurate environment modeling with fast OOD detection via NFs and causal inference through the incorporation of causal graphs within the architecture. Building on this foundation, we propose MOOD-CRL (model-based offline OOD-adapting causal RL), which leverages OOD detection, model expressiveness, and causal reasoning to develop a causal framework for model-based offline RL. Our contributions are twofold as follows.

- We propose an effective algorithm using causal normalizing flows that systematically guides policy learning in OOD regions. Specifically, we remove the prevalent use of a penalty for OOD exploration in the past literature but leverage the exact likelihood estimation of normalizing flows to detect and regulate the degree of OOD exploration.

- We conduct comprehensive empirical studies by comparing our algorithm against state-of-the-art model-based and model-free baselines in multiple robotic manipulation domains. In addition, we present several ablation studies: (i) evaluating the effectiveness of our model in OOD prediction compared to a naive prediction model in a discrete interpretable scenario, (ii) analyzing the policy performance under different RL algorithms that vary in algorithmic sophistication, and (iii) examining the sensitivity of the algorithm’s performance with respect to the quality of the given data.

Paper outline. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The necessary background for our method is introduced in Section 3. Next, the details of our algorithm are discussed in Section 4. This is followed by comprehensive experiments designed to evaluate the OOD adaptation of our approach, including extensive comparisons with other baselines, in Section 5. Finally, this paper is concluded with a discussion of the current limitations of our method and potential directions for promising future research to further advance offline RL in Section 7.

2. Related Work

Offline RL has gained significant attention in the community, with several notable methods emerging for its resolution. This includes both model-based and model-free algorithms, with resolutions on handling the distributional shift via constraints to match the training data distributions. It has been an active search to explore more sophisticated methods for incorporating such constraints via (1) policy constraint, (2) importance sampling, and (3) uncertainty estimation. We summarize the previous trend below with the taxonomy proposed by [].

2.1. Model-Free Algorithms

2.1.1. Policy Constraints

Prior works [,,] use f-divergence to quantify the distributional shift and use it as a constraint in the policy learning algorithm to align the action distributions of the learning policy with the behavior policy. This formulation requires the parametric form of the behavior policy. For example, [] estimates behavior policy via supervised regression, while [] suggested support matching over distribution matching to prevent OOD actions, which was proved to be effective by exploiting only good actions in the data.

2.1.2. Importance Sampling

Another line of work, exemplified by [,], uses importance sampling to learn an optimal policy directly from a precollected dataset. The core of this method is to estimate an optimal distributional correction term, which allows the algorithm to correctly measure the performance of the learning policy, even when generalizing to OOD states. However, despite this correction, these approaches still rely on explicit OOD penalization to avoid policy degradation.

2.1.3. Uncertainty Estimation

Instead of using rigid f-divergence constraints, some approaches mitigate excessive conservatism by estimating the distributional shift via uncertainty. This uncertainty quantifies the model’s confidence in OOD states, which is then used to penalize the learning policy to visit OOD (i.e., highly uncertain) regions. For example, some algorithms [] adopt practical dropout-based uncertainty methods to detect OOD state–action pairs and penalize their contribution in the training objectives. Other methods [] leverage the disagreement within an ensemble of Q-networks; the resulting high prediction variance on OOD points is then used to penalize their Q-values, often in conjunction with clipped Q-learning. This same principle of using network disagreement as an OOD metric is also seen in [,], where the prediction error between a ‘predictor’ and ‘target’ network serves as a proxy for the distributional shift, providing an uncertainty-based OOD penalty.

2.1.4. OOD Adaptation Using Transfer Technique

To address OOD data in offline RL, [] proposed a teacher–student framework where a student policy learns from the offline data, augmented by knowledge distilled from a teacher policy trained on separate medium or expert data. To mitigate critic overestimation from bootstrapping errors on OOD actions, they also introduce a policy discrepancy measure—a non-probabilistic, one-step-free metric—to refine the loss computation.

2.2. Model-Based Algorithms

Model-based offline RL centers on estimating transition dynamics and reward functions from a precollected dataset. The central challenge of this approach is, however, the limited inference of the learned model on OOD states.

The majority of the prior works tackle this through reward regularization. For instance, [] employs a supervised learning approach with explicit uncertainty quantification to underestimate rewards, and [] formalizes this by learning a pessimistic MDP whose performance is designed to lower-bound the policy’s real-world performance, thus serving as a safe surrogate for policy learning.

Another line of work uses learned models for data augmentation to improve dataset coverage and quality. For example, ref. [] proposes generating ‘high-quality’ synthetic trajectories and then employs a separate backward model to verify their reliability. These learned models, recently leveraging advanced architectures like the Transformer [], are also commonly unrolled for trajectory planning []. While this improved dataset is intended to provide OOD state coverage, these methods rely on heuristics to ensure data quality. However, these heuristics do not guarantee that the generated data necessarily reflects the true physics present in the dataset.

2.3. Others

There are multiple other studies to enhance offline RL, such as Lyapunov stability and control-invariant sets [], invariant representation learning [], mutual information regularizer [], and anti-exploration [] to penalize OOD states/actions. However, the degree of conservatism to avoid overestimation is still ambiguous and can be sub-optimal. A straightforward extension is proposed in [] by sampling and learning under multiple conservatism degrees. Another notable issue in offline RL is how to learn policies from data generated by multiple policies (with varying sampling distributions and performance) for the task [].

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Reinforcement Learning

A Markov decision process (MDP) is a mathematical formulation for sequential decision-making problems. The MDP is a four-tuple , including a state set , an action set , a transition function, , and a reward function, . In RL, the objective is to optimize the policy by maximizing the cumulative reward , where is the discount factor.

3.2. Offline Reinforcement Learning

In offline RL, the objective remains the same as in online RL, but learning is performed from fixed and precollected data without further online interaction. This can be accomplished either through a model-based approach or by directly learning a policy in a model-free manner. While offline RL presents numerous advantages by avoiding online interaction, it introduces a new challenge of distributional shift. This factor is known to hinder policy optimization, as highlighted in []. Various works have explored this area from different angles, including the exploration of conservative value functions [], estimation of state-action density in policy training [], and utilization of a superior network architecture (specifically the Transformer []), yet no promising results compared to their online counterpart. Hence, a crucial yet under-explored aspect of offline RL is to address the distributional shift through adaptation beyond the given data.

3.3. Causal Reinforcement Learning

Causal discovery [] aims to uncover the causal graph among variables in the data [,,]. For instance, this often involves adopting a scoring metric to identify true causal relationships and designing policy optimization schemes based on the discovered graph []. Once identified, the causal graph can be incorporated into reinforcement learning (causal RL) to enhance the accuracy of environmental modeling. Nevertheless, despite substantial progress in causal discovery, a critical gap remains in understanding how these graphs can be effectively utilized, particularly within offline RL.

3.4. Normalizing Flows (NFs)

NFs belong to a distinct category of generative models, alongside a generative adversarial network (GAN) and variational autoencoder (VAE). While sharing structural similarities with VAE, NFs are different in incorporating diffeomorphic transformations that enable precise density estimations of the modeled data distribution. Unlike the use of non-invertible transformations by VAE, NFs use bijective and invertible transformations to enable seamless passage of samples back and forth through the model, allowing exact probabilistic inference. Derived using the change of variable, the NFs are updated by maximizing the model’s probability density, represented as , in generating samples from one simple distribution to another distribution as follows:

where and are vectors of the same dimensionality (bijective), where x represents the given data, and u is a corresponding representation in the base distribution (i.e., uniform or multivariate Gaussian distribution). The Jacobian is the matrix of all partial derivatives of F.

The role of the Jacobian, , is crucial as it shapes the original data into a base distribution. However, the high computational complexity of computing the determinant of the Jacobian, i.e, , has established the convention of employing autoregressive transformations, in which the Jacobian takes a lower-triangular form, reducing the complexity from cubic to linear, . This preference makes the autoregressive structure inherently suitable and a natural choice for NFs [].

Moreover, the autoregressive NF has undergone theoretical scrutiny as a framework for causal inference [,]. Specifically, these are achieved by constraining the flow of data passage by the given causal graph (e.g., binary adjacency matrix). This approach simply prevents the information sharing between irrelevant nodes within the transformation, , computing with only causally related ones. Under certain conditions, this masking process guarantees the equivalence between the autoregressive causal NF and a structural causal model, leading to causal NFs.

4. Model-Based Offline OOD-Adaptation Using Causal Normalizing Flows

In this section, we introduce our algorithm for offline model-based RL, proposing the CNF-based model architecture for model-based policy optimization. Given a precollected dataset and a causal graph of the environment, we present an architecture for learning the transition dynamics and reward function under the bijective property of CNF. We provide the pseudo-code of our proposed algorithm in Algorithm 1.

4.1. Formulating CNF for MDP Prediction

Conventional multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) use a non-bijective mapping, , to model dynamics, whereas CNFs employ bijective transformations that require identical input and output dimensionalities. This bijectivity of CNFs hinders a naive application of a conventional MLP-based approach, since the dimension of state–action pairs is not equal to the dimension of next state and reward, . This mismatch has limited the use of CNFs in offline model-based RL, despite the clear advantages of CNFs.

| Algorithm 1 MOOD-CRL: Model-based Offline OOD-Adapting Causal Reinforcement Learning |

|

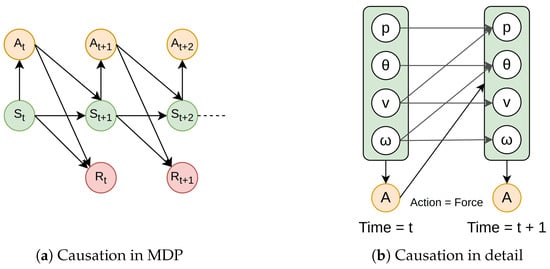

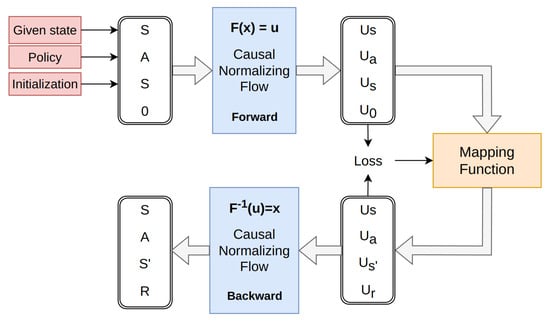

In offline RL, the data typically consists of MDP tuples , where the causation of the MDP and the relationships within it are visualized in Figure 1. To model the transition dynamics and reward function with the bijective property of CNFs, we treat the entire MDP tuple as both the input and output of the model. Specifically, we aim to predict the true MDP tuple from the perturbed tuple , where the next state and reward tokens are initialized as previous state, s, and zero (denoted as ⌀), respectively. The rationale for this initialization approach is to closely place the perturbed and true tuples in the base space. Additionally, we employ a mapping function (an MLP) in the base space to map a perturbed tuple with the base representation of the corresponding true MDP tuple u, such that the inverse operation of the CNF can recover the true tuple in the original data space. These sequential operations undergo the following transformations:

where represents the bijective transformation of the CNF, and is a MLP, mapping to u. They can be denoted as compositions of sequential transformations as follows:

where and are intermediate transformations within their architectures.

The diagram in Figure 2 illustrates our algorithm, which simultaneously models both the transition dynamics and the reward function. Notice the interplay among the MLP in the base space (serving as a mapping function connecting perturbed tuples to true tuples), the CNF (transforming predicted tuples in the base space to the true distribution), and the policy network (mapping states to actions for decision-making).

Figure 1.

Illustration of causality in RL context. (a) depicts the decision flow based on the Markov property: state causes action (), state–action causes next-state () and reward (). (b) illustrates the qualitative physics-informed causation in state-to-state transitions for each time frame, specifically in an Inverted-Pendulum Environment by OpenAI Gym []. The variables p, , and correspond to position, angle, velocity, and angular velocity, respectively. As shown in (b), the causation is grounded in physics, and multi-dimensional actions can be further partitioned into various parts for other environments.

Figure 2.

Illustration of our CNF-based model architecture with an MLP in the base space. The system processes two MDP tuples: the first initializes the next state as the current state with a reward of zero, while the second represents the true tuple that the model aims to predict.

4.2. Architectural Details

In this section, we present the detailed operations of each component and explain the rationale behind their use in our algorithm.

4.2.1. Autoregressive Flow Model for Causal Inference in MDPs

In our setup, we define x, z, and u as the original data, intermediate data during the transformation process, and the ultimately transformed data in the base distribution, respectively. This process is articulated as follows:

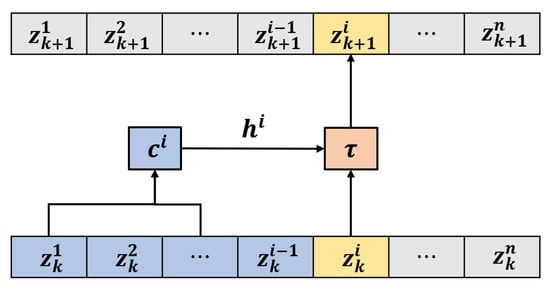

Building on this, the autoregressive transformation, labeled , is defined by the subsequent expression:

In this context, and c denote the transformer and conditioner, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 3. The subscript, k, indicates the transformation index, while the superscript, i, denotes the variable index within a layer. This framework inherently aligns with causal inference, particularly guided by an additional matrix-product operation inside c (conditioner) with a causal graph. The schematic ensuring causation in the transformation is as follows:

where denotes the element in the i-th row and j-th column of the adjacency matrix , representing the causal graph specific to a given environment. This behaves as a masking of variables for those that do not have a causal relationship.

Figure 3.

Autoregressive flow model illustration of transformation: . The conditioner, denoted as c, gathers information from previous elements, while transforms the current element and its history into a new value. The figure is adopted from [].

As a result, our algorithm optimizes the CNF parameters by minimizing the divergence between the true and generated sample distributions, using the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence,

4.2.2. MLP in the Base Space

The use of a base space is well established in the machine learning literature, as it enables simpler representations and improves interpretability. For example, ref. [] demonstrates that arithmetic operations in the base space can easily predict image rotations. Similarly, we use this idea in our framework such that the MLP in the base space maps two MDP tuples, namely and u. The MLP is trained to minimize the discrepancy between these two tuples; for our case, we adopted the -norm as follows: This should be in -norm but was indicated as -norm.

where the gradient with respect to is detached.

4.2.3. Policy Training with Causal Model

After training the CNF and the MLP, we employ the resulting model as a simulator with which any online model-free algorithms can be used to train a policy. Specifically, for the given initial state , we sample action and use the simulator to get the transition and reward as . Let the trajectory buffer of a policy be defined as . As policy rollouts, we have its trajectories in the set generated by appending for each time step (i.e., ).

Then, we use the following on-policy optimization to update the policy:

It is important to note that, unlike prior offline RL approaches [,,], we do not incorporate any reward penalization. Additionally, to ensure the causal model consistently makes reasonable predictions, we devise a principled approach to prevent erroneous extrapolations into OOD space. This method terminates the episodic task if the likelihood of observing the current MDP tuple falls dramatically low. The terminating criterion is shown as follows:

where the parameter is user-defined to control the level of exploration into OOD scenarios, and it was chosen as a negative scaler. Notice that this termination process is only feasible when using CNF as a causal model, as other causal models such as causal transformers and causal Bayesian networks do not possess the ability to perform exact likelihood estimation.

5. Experiments

This section systematically and extensively evaluates our method using OpenAI’s Gymnasium [] to address the following questions:

- Is MOOD-CRL able to effectively capture causation among variables?

- Is MOOD-CRL able to operate under different qualities of data?

- Is MOOD-CRL able to surpass previous offline RL algorithms in performance?

5.1. Baselines Algorithms

Our baselines encompass both model-based and model-free algorithms, as described below.

- Model-based offline OOD-adapting RL (MOOD-RL): MOOD algorithm without a causal graph. It is simply a base distributional learning in normalizing flows parameterized by MLP.

- Model-based offline policy optimization (MOPO) []: MLP-based network architecture which learns world dynamics and uncertainty present in predictions to avoid OOD exploration by reward penalty.

- Offline policy optimization via stationary distribution correction estimation (OptiDICE) []: Model-free algorithm that directly learns a policy without learning transition dynamics and reward function via stationary distribution correction estimation.

- Multi-layer perceptrons (MLP): Traditional deep neural network architecture to predict the transition dynamics and reward function.

5.2. Testing Environments

We consider widely used continuous robotic environments to address Questions 2 and 3.

- Inverted Pendulum: and where a cart with the vertical pole seeks to keep the pole upright.

- Hopper: and where a one-legged robot aims to achieve forward velocity without falling.

- Walker: and where a two-legged robot aims to achieve forward velocity without falling.

- HalfCheetah: and where a two-legged cheetah aims to achieve forward velocity without falling.

We construct the causal map (i.e., adjacency matrix used in Equation (6)) based on the provided dynamics of each environment we consider in Gymnasium (https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/ (accessed on 27 April 2024)).

5.3. Causal Predictive Power of MOOD-CRL

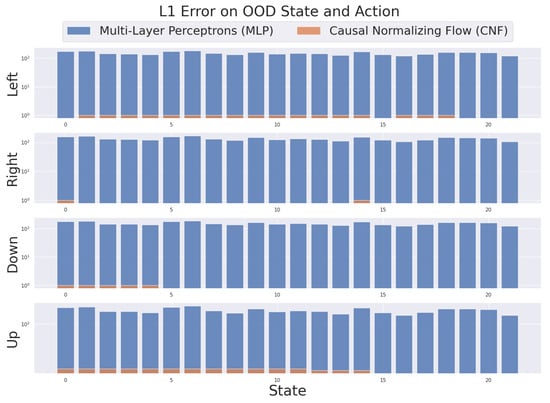

We demonstrate the stability and predictive performance of MOOD-CRL in OOD scenarios using a straightforward discrete environment: FrozenLake []. We compare the predictions of transition dynamics in OOD regions between the MLP-based model and the CNF-based model.

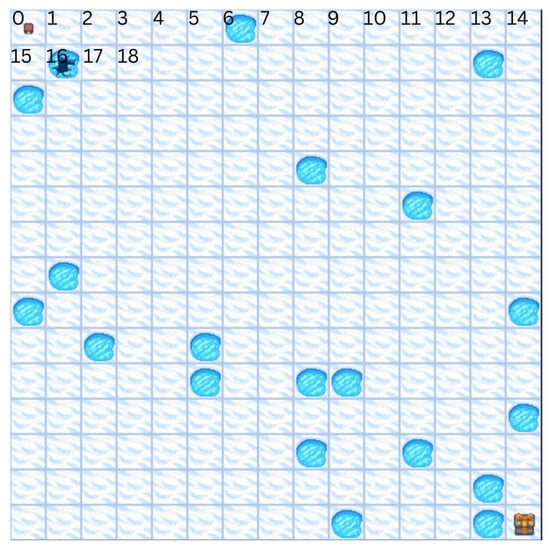

5.3.1. Experimental Design: Analysis in a Discrete Environment

We begin with a deterministic FrozenLake domain as depicted in Figure 4. In this environment, the agent initiates at the top-left corner (state = 0) to reach the goal, bottom-right, state (state = 224). The agent has four available actions: moving left, down, right, and up. Notably, any actions directed towards obstacles or the boundary of the domain result in remaining in the same state. To evaluate the OOD prediction capability of our model, we constructed the training data by selecting the bottom 80% of MDP tuples: state–action pairs, , where and ; the remaining part is test data. Our primary focus lies in understanding whether the model can capture the fundamental dynamics of this domain: moving upwards entails subtracting 15 from the previous state or identifying the boundaries on the left and right sides. Note that the upper boundary and obstacles are inherently not discoverable due to the absence of information in the data. However, the left and right boundaries hold the potential for inference.

Figure 4.

A classical toy problem implemented in Gymnasium involves a 15 × 15 grid with non-slippery conditions selected for a deterministic environment. The top-left corner has a state of 0, increasing by 1 towards the right. Any actions towards boundaries and obstacles result in staying in the same position.

5.3.2. Evaluation: Analysis in a Discrete Environment

As depicted in Figure 5, the CNF model demonstrates an accurate capture of the system dynamics, resulting in a significantly reduced prediction error. This superior accuracy is attributed to its causal architecture, which enables it to learn the true data-generating mechanism rather than just superficial correlations. The substantial error gap between the models is evident in the OOD region where . When confronted with these unseen inputs, the standard MLP baseline fails to generalize, leading to catastrophic and erroneous predictions. The CNF, in contrast, remains robust, demonstrating its ability to effectively model system dynamics and produce reliable, accurate outputs even when extrapolating to unseen regions of the state-action space.

Figure 5.

This figure compares the prediction errors of MLP- and CNF-based models (log-scale) of transition dynamics. The training data consist of state–action pairs with , while states are reserved for testing in FrozenLake, as shown in Figure 4. The results indicate that the CNF-based model consistently provides reasonable predictions in OOD scenarios, while the MLP fails more broadly under OOD conditions, producing incorrect values.

5.4. Assessments in Continuous Robotic Control Tasks

In this section, our primary focus is on how the learned CNF model can improve the performance of the resulting policy compared to the naive MLP-based model and true dynamics.

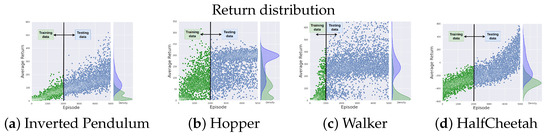

5.4.1. Experimental Design: Continuous Robotic Tasks

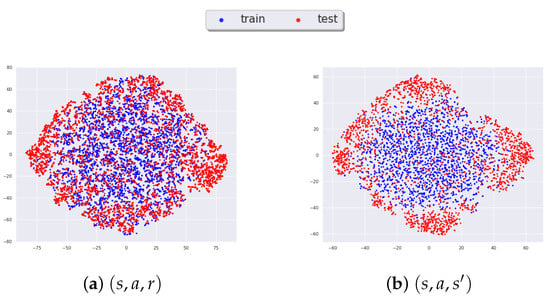

To closely mimic the pure online setting, we curated custom data that reflects different learning stages to evaluate the OOD adaptation performance of algorithms. Specifically, the training data consist of state–action pairs observed within the first 2000 episodes, as illustrated by the return distribution in Figure 6, which we refer to as low-quality data. Medium-quality data, collected from episodes 2000 to 3000, is kept the same size as the low-quality dataset for ablation purposes, which we explore in the next section. This data composition method measures the model’s ability to generalize from partial to unseen data, which is essential for learning complex, multi-stage policies. Akin to how infants learn to crawl before walking, we test if a model exposed to one stage of a task can successfully extrapolate its knowledge to the next. Hence, our evaluation is to verify if the learned models can provide accurate information given a missing link in the learning process. The t-SNE visualization [] is provided in Figure A2 in Appendix A, offering a sound justification for this choice.

Figure 6.

This figure illustrates the structure of our data, showing the gap between the training distribution and the testing (i.e., target) distribution (see the density plot on the right side of each figure) This is to provide more explanation on the density plot on the right. This setup is specifically designed to evaluate the OOD-adaptation of the algorithm using training (i.e., low-quality) data to obtain higher rewards in the testing data.

We employ two on-policy policy gradient methods, such as REINFORCE [] and proximal policy optimization (PPO) []. Specifically, we evaluate the algorithmic sensitivity of each model-based offline RL approach by pairing it with both a classic (REINFORCE) and a modern (PPO) policy gradient method. These on-policy algorithms are trained by using the transition and rewards generated by the given model (i.e., CNF, MLP, and true). Note that this setup differs from prior offline RL literature, where they typically use an off-policy method—soft actor–critic []—that is inherently robust to distributional shift. Our rationale for using an on-policy policy gradient method is to directly evaluate the OOD adaptation performance of each learned model.

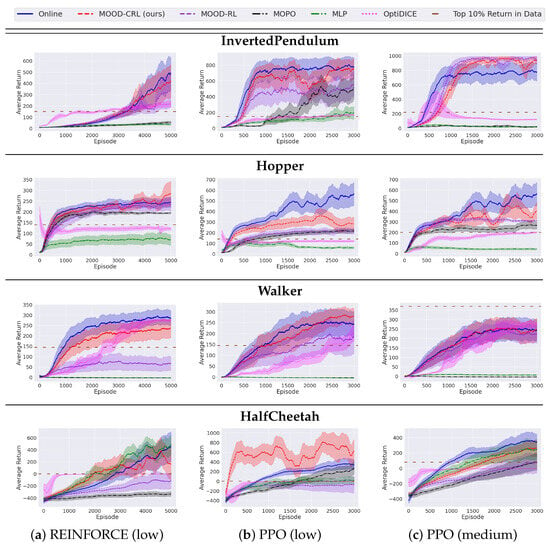

5.4.2. Evaluation: Continuous Robotic Tasks

As shown in Figure 7, the baseline methods exhibit poor performance, particularly on low-quality data (first two rows). MOPO, for instance, performs poorly when combined with REINFORCE. While it achieves competitive results with PPO, it consistently fails to match the performance of our method, MOOD-CRL, in any task. This failure is particularly pronounced in the HalfCheetah environment, where MOPO underperforms even a traditional MLP baseline. This poor performance is attributed to MOPO’s conservative mechanism: it tends to aggressively penalize OOD scenarios by underestimating their values. This behavior, intended to ensure safety, ultimately hinders policy improvement and leads to inconsistent training results. Concurrently, the model-free OptiDICE generally fails to achieve the performance levels of model-based methods, suggesting that model-based approaches offer a more principled solution for these tasks.

Figure 7.

Average episodic returns (higher is better) over 5 seeds are plotted. Standard errors are shown in the shaded regions. Each row represents one domain, while each column represents a base RL algorithm–data quality pair. The solid horizontal line marks the optimal return (top 10%) found in the training data. Blue curves denote online learning benchmarks.

In contrast, our method, MOOD-CRL, demonstrates robust and high performance. It consistently tracks the online learning curves, or at least their lower bounds, across both REINFORCE and PPO algorithms. MOOD-CRL is also highly competitive with MOPO in every domain, highlighting the clear benefits of our base-distributional learning approach, which leverages causal normalizing flows for interpretability and robustness. We did, however, observe an anomalous spike in performance for MOOD-CRL in HalfCheetah (PPO, low-quality data), where its return unexpectedly exceeded the online learning curve. We attribute this to slight errors in state prediction, which resonated to create high-quality state–action pairs. As this was an isolated case and no performance degradation was observed, we conclude that MOOD-CRL’s predictions remain robust and reasonably accurate across the entire domain.

5.5. Ablation on Different Data Quality

To assess the sensitivity of each baseline and ours to varying data quality, we conduct an ablation study by including medium-quality data (last row of Figure 7) in addition to its low-quality counterpart. This differs from the previous method of employing low-quality data inputs, which involves utilizing knowledge from early iterations and assessing its OOD adaptation. Instead, we now task the algorithm with medium-quality data to learn a high-performing policy.

In the cases of Inverted Pendulum, Walker, and HalfCheetah, it is evident that MOPO and MLP fail to exhibit even minor improvements. This suggests that the predictions made by these models do not facilitate any OOD adaptation for optimal rewards. Conversely, ours, including MOOD-RL, demonstrate stable and consistent learning curves. This solves the previous inferiority of the model-based approach against the model-free approach, where the given data lacks wide coverage, underscoring the advantage over other model-based approaches.

5.6. Experimental Remarks

The baseline algorithms demonstrated poor performance in our online-focused experimental settings, which were designed to benchmark state-of-the-art methods. This highlights their heavy reliance on data distributions and their inability to extrapolate to OOD scenarios. Both model-based and model-free approaches primarily depend on algorithmic mechanisms that are robust to distributional shifts, rather than addressing the root cause of OOD adaptation. In contrast, our proposed method, MOOD-CRL, clearly outperforms these baselines, showcasing its effectiveness and adaptability in these challenging settings.

6. Discussions

6.1. Broader Impact

The offline learning scheme of our approach makes it safer for deployment in safety-critical environments, as it does not require online interaction. However, caution is still warranted in domains with ethical considerations, such as healthcare, where errors can have significant consequences. In this context, our algorithm can also be effective, as it includes a OOD detection parameter that controls the degree of OOD-adaptation.

6.2. Limitations

While this paper introduces a novel research avenue for model-based offline RL, we acknowledge several limitations of our approach. These include the absence of theoretical support and scalability issues, with computational costs increasing as the dimensions of states and actions grow. The latter is particularly pronounced as passing the entire MDP tuple through the model becomes more susceptible to the curse of dimensionality.

6.3. Future Work

We suggest several intriguing research avenues worth exploring further. (a) It is promising to investigate further which base-distributional learning mechanisms, coupled with interpretative tools (normalizing flows or VAE), can enhance overall learning outcomes, such as Bayesian neural networks [], recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [], or Transformers []. (b) Moreover, constrained settings [], even with environmental non-stationarity [], can be considered in offline RL under MOOD-CRL’s umbrella. This is particularly crucial in safety-critical domains like autonomous driving and robotic manipulation, where safety breaches are intolerable, and non-stationary conditions may prevail. These requirements necessitate rigorous proof through constraint-satisfaction analysis in OOD cases, either with chance-constrained or worst-case safety criteria. (c) Another direction is to explore the sensitivity of our causal approach to data decentralization. Since the model’s performance is highly dependent on the training data, its effectiveness could be detrimentally affected in decentralized settings. Investigating the model’s robustness in such scenarios warrants further investigation. (d) Lastly, one could bring other techniques to enhance offline RL by studying conformal predictions for uncertainty quantification calibration and physics-informed neuro-symbolic RL with data-invariant logic rules for extrapolation.

7. Conclusions

While prior work in offline RL centered on OOD constraints, we introduced an OOD-adapting algorithm empowered by causal inference and accurate OOD detection. Our approach eliminates OOD penalization, addressing distributional shifts without policy degradation through a novel causal normalizing flow and MLP architecture. This model-based formulation leverages causal inference, OOD detection, and the ability to handle multi-modal distributions of data. Our experiments confirm that our model’s learning curve closely tracks the performance of online training. Additionally, our ablation studies demonstrate superior robustness, showing that the model is significantly less sensitive than all baselines to variations in data composition and the choice of policy gradient algorithm. This research introduces a foundational approach to model-based offline RL for out-of-distribution adaptation, opening several avenues for future investigation. Promising directions include the development of more sophisticated model architectures and the extension of this framework to more general safety-critical applications, such as autonomous driving and medical care.

Author Contributions

M.C. contributed the idea generation, algorithmic implementation, and initial draft writing, while C.S. provided guidance on idea generation, experimental planning, and finalizing this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

A version of this paper has previously appeared as a preprint at https://export.arxiv.org/pdf/2405.03892 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Experimental Details

In this section, we outline the specific configurations of our experiments conducted in OpenAI Gymnasium []. We provide details on the composition of the training data and the underlying rationale. Additionally, we elaborate on the specific parameters employed for the baselines, including network size, key hyperparameters, and the causal graph used in our approach.

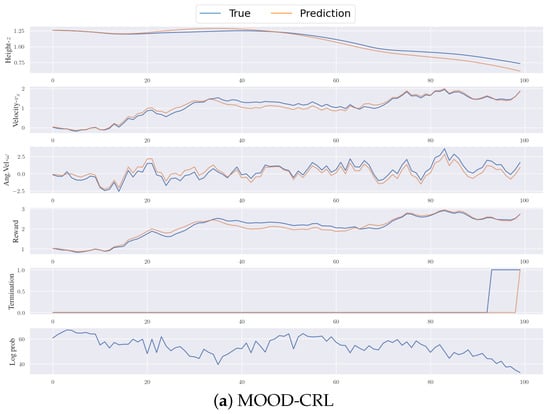

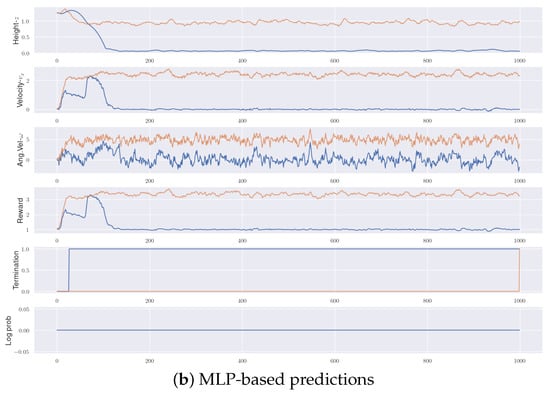

Figure A1.

This illustrates the disparity between the true and predicted values in the Hopper. Key physical quantities of the torso of Hopper are plotted alongside rewards and termination (for those requiring termination prediction as well). Log probability is also included to validate the predictions made by our method. Notably, while MLP-based predictions may exhibit unknown patterns, our predictions form reasonable curves and patterns compared to the true values, albeit with some margins.

Appendix A.1. State and Reward Predictions Curve

For additional clarity, we provide a comparison of transition and reward dynamics between the trained model and the true oracle for the Inverted Pendulum in Figure A1 for the sake of simplicity.

Appendix A.2. t-SNE Visualization of Data

Using t-SNE visualization [], the Figure A2 validates our choice of data for OOD adaptation purposes.

Appendix A.3. Experimental Settings

Below, detailed hyperparameters for experiments and qualitative physics-informed causal graphs are discussed.

Hyperparameters

- Optimizer: Adam, Learning Rate: 1

- CNF (Causal Normalizing Flow):

- -

- Flow model: Masked Autoregressive: Flow []

- Architecture: conditioner (64, 64, 64) with 5 layers of transformation ;

- Base Distribution: Normal;

- Activation: elu;

- -

- Regularization: weight regularization:

- Training Epochs: 2000;

- -

- Base model: MLP:

- Architecture: neural network dimension of (512, 512, 512, 512);

- Activation: leakyrelu;

- -

- Regularization: weight regularization:

- Training Epochs: 1000.

- MOPO:

- -

- Architecture: Single ensemble with dimensions (512, 512, 512, 512);

- -

- Activation: elu;

- -

- Regularization: weight regularization;

- -

- Training Epochs: 1000.

- MLP:

- -

- Architecture: neural network dimension of (512, 512, 512, 512);

- -

- Activation: leakyrelu;

- -

- Regularization: weight regularization;

- -

- Training Epochs: 1000.

- Policy Network:

- -

- Architecture: neural network dimension of (64, 64);

- -

- Algorithm: REINFORCE and PPO:

- REINFORCE: lr = 1e-4;

- PPO: K-epochs = 2, lr(policy) = 1e-4, lr(critic) = 3e-3, epsilon-clip = 0.2.

Figure A2.

The visualization showcases the t-SNE representation of HalfCheetah data, emphasizing the distributional shift between the training and testing datasets. (a) captures the variance in reward dynamics, while (b) visualizes the transitional shift in distribution.

References

- Rezaeifar, S.; Dadashi, R.; Vieillard, N.; Hussenot, L.; Bachem, O.; Pietquin, O.; Geist, M. Offline reinforcement learning as anti-exploration. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 8106–8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Thomas, G.; Yu, L.; Ermon, S.; Zou, J.Y.; Levine, S.; Finn, C.; Ma, T. Mopo: Model-based offline policy optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 14129–14142. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Jiang, J.; Long, G.; Zhang, C. Causal Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.01452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Cai, R.; Sun, F.; Huang, L.; Hao, Z. A Survey on Causal Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.05209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudencio, R.F.; Maximo, M.R.; Colombini, E.L. A survey on offline reinforcement learning: Taxonomy, review, and open problems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 35, 10237–10257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; Meger, D.; Precup, D. Off-policy deep reinforcement learning without exploration. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2052–2062. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Zhou, A.; Tucker, G.; Levine, S. Conservative q-learning for offline reinforcement learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Tucker, G.; Nachum, O. Behavior regularized offline reinforcement learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.11361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jeon, W.; Lee, B.; Pineau, J.; Kim, K.E. Optidice: Offline policy optimization via stationary distribution correction estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 6120–6130. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Paduraru, C.; Mankowitz, D.J.; Heess, N.; Precup, D.; Kim, K.E.; Guez, A. Coptidice: Offline constrained reinforcement learning via stationary distribution correction estimation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.08957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhai, S.; Srivastava, N.; Susskind, J.; Zhang, J.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Goh, H. Uncertainty weighted actor-critic for offline reinforcement learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.08140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Moon, S.; Kim, J.H.; Song, H.O. Uncertainty-based offline reinforcement learning with diversified q-ensemble. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 7436–7447. [Google Scholar]

- Nikulin, A.; Kurenkov, V.; Tarasov, D.; Kolesnikov, S. Anti-exploration by random network distillation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 26228–26244. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Tao, J.; Lyu, J.; Li, X. Exploration and anti-exploration with distributional random network distillation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gangopadhyay, B.; Yeh, J.F.; Takamatsu, S. Augmenting Offline RL with Unlabeled Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.07117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidambi, R.; Rajeswaran, A.; Netrapalli, P.; Joachims, T. Morel: Model-based offline reinforcement learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 21810–21823. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Fang, X.; Xu, K.; Zhao, W.; Li, H.; Zhao, D. High-quality synthetic data is efficient for model-based offline reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Janner, M.; Li, Q.; Levine, S. Offline reinforcement learning as one big sequence modeling problem. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.; Gradu, P.; Choi, J.J.; Janner, M.; Tomlin, C.; Levine, S. Lyapunov density models: Constraining distribution shift in learning-based control. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 10708–10733. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.; Su, Y.; Kumar, A.; Levine, S. Data-Driven Offline Decision-Making via Invariant Representation Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.11349. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Kang, B.; Xu, Z.; Lin, M.; Yan, S. Mutual Information Regularized Offline Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.07484. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Kumar, A.; Levine, S. Confidence-Conditioned Value Functions for Offline Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.04607. [Google Scholar]

- Data-Driven Deep Reinforcement Learning. Available online: https://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2019/12/05/bear/ (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Levine, S.; Kumar, A.; Tucker, G.; Fu, J. Offline reinforcement learning: Tutorial, review, and perspectives on open problems. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.01643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lu, K.; Rajeswaran, A.; Lee, K.; Grover, A.; Laskin, M.; Abbeel, P.; Srinivas, A.; Mordatch, I. Decision transformer: Reinforcement learning via sequence modeling. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 15084–15097. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causal inference. Causality: Objectives and Assessment; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Ng, I.; Chen, Z. Causal discovery with reinforcement learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.04477. [Google Scholar]

- Gasse, M.; Grasset, D.; Gaudron, G.; Oudeyer, P.Y. Causal reinforcement learning using observational and interventional data. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.14421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glymour, C.; Zhang, K.; Spirtes, P. Review of causal discovery methods based on graphical models. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Meisami, A.; Tewari, A. Efficient reinforcement learning with prior causal knowledge. In Proceedings of the Conference on Causal Learning and Reasoning, Eureka, CA, USA, 11–13 April 2022; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 526–541. [Google Scholar]

- Papamakarios, G.; Nalisnick, E.; Rezende, D.J.; Mohamed, S.; Lakshminarayanan, B. Normalizing flows for probabilistic modeling and inference. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 2617–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Javaloy, A.; Sánchez-Martín, P.; Valera, I. Causal normalizing flows: From theory to practice. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.05415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemakhem, I.; Monti, R.; Leech, R.; Hyvarinen, A. Causal autoregressive flows. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Virtual, 13–15 April 2021; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3520–3528. [Google Scholar]

- Towers, M.; Terry, J.K.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Balis, J.U.; Cola, G.d.; Deleu, T.; Goulão, M.; Kallinteris, A.; KG, A.; Krimmel, M.; et al. Gymnasium. Zenodo 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06434. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, G.; Cheung, V.; Pettersson, L.; Schneider, J.; Schulman, J.; Tang, J.; Zaremba, W. OpenAI Gym. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.01540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; McAllester, D.; Singh, S.; Mansour, Y. Policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning with function approximation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 1999, 12, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Hartikainen, K.; Tucker, G.; Ha, S.; Tan, J.; Kumar, V.; Zhu, H.; Gupta, A.; Abbeel, P.; et al. Soft actor-critic algorithms and applications. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.05905. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, R.M. Bayesian Learning for Neural Networks; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 118. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning internal representations by error propagation. In Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition: Foundations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Held, D.; Tamar, A.; Abbeel, P. Constrained policy optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.; Sun, C. Constrained Meta-Reinforcement Learning for Adaptable Safety Guarantee with Differentiable Convex Programming. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 20975–20983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamakarios, G.; Pavlakou, T.; Murray, I. Masked autoregressive flow for density estimation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 2335–2344. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).