Abstract

The information environment is an important factor that affects enterprises’ implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Considering the uncertainty of product demand, this paper focuses on the retailer’s CSR behavior mechanism under information symmetry and asymmetry scenarios. By constructing four different Stackelberg game models, we obtain the product prices, green decision-making, and the revenues of supply chain members. Applying the game-theory-based method, we further analyze the impact of the market demand uncertainty factor, true CSR level, and estimated CSR level on the decision and performance. The results show the following: (1) Demand uncertainty enhances the CSR effect in the peak season but inhibits it in the off-season. (2) The difference in information structure affects the proportion of supply chain members’ green efforts and green costs. (3) The asymmetry of information makes it impossible for the retailer to enhance its economic benefit by implementing CSR within a reasonable range. Thus, from a profitable perspective, its optimal strategy is to discontinue CSR investment while pretending to undertake it. (4) When the retailer implements CSR, once the manufacturer cannot accurately obtain the true CSR information, its own revenue will decrease, and if overestimating, the retailer will benefit. The conclusions of this paper provide practical and management insights for information transparency in the green supply chain.

Keywords:

uncertain demand; information asymmetry; corporate social responsibility; strategic behavior; green supply chain MSC:

90B06

1. Introduction

With rapid economic development, environmental damage caused by enterprises’ production and operation activities has become increasingly severe. To establish a resource-saving and environment-friendly society and to promote economic–environmental coordination, a series of policies has been introduced by the government to regulate high-pollution practices. As an effective tool for enterprises to achieve coordinated economic and environmental development, green supply chains have gained widespread recognition among enterprises [1]. Moreover, environmental consciousness among consumers significantly influences green supply chain operations and is a key driver of market demand. Relevant studies show that the environmental friendliness demonstrated by green products prompts consumers to be willing to pay a higher price for them than for ordinary products [2,3]. Consumers’ green consumption is closely associated with their awareness of green products, which the retailer can significantly influence through green marketing efforts. Green marketing has been confirmed to boost sales of sustainable products. For instance, Jd.com uses biodegradable express delivery bags and tape-free cardboard boxes to reduce environmental pollution caused by single-use packaging. Red Star Macalline attaches low-carbon labels to its products to increase consumer purchases [4]. In addition to the case where the retailer separately takes responsibility for the green marketing of products, the upstream manufacturer may also enhance promotional efforts by marketing a contract with the retailer. In conclusion, under the combined effect of the external environmental regulations and the internal green consumption potential, supply chain members collaboratively adopt green supply chain management, thereby strengthening corporate competitiveness.

Corporate social responsibility mandates that businesses extend their obligations beyond traditional financial duties to shareholders by addressing the needs of broader stakeholders, including consumers, the environment, and employees [5,6]. In recent years, influenced by rising social consciousness, industry competition, and the sustainability concept, balancing economic, environmental, and social needs has become critical for corporate development. According to Cone Communications’ 2017 CSR research report, 87% of consumers prefer purchasing from CSR-active companies, while 76% actively boycott irresponsible firms [7]. Facing growing pressure for socially responsible management, supply chain enterprises now actively undertake CSR practices and extend the corresponding code of conduct to the whole supply chain. This strategic shift aims to enhance brand reputation and occupy more market share. For example, BASF, in collaboration with other chemical giants such as Bayer, Henkel, Lanxess, etc., jointly initiated the TFS (Together for Sustainability) standard to assess the behavioral norms of its partners in areas such as environmental protection, labor rights, health and safety, and legal employment. It has set up CSR standards at the “entry threshold” level for the entire industry supply chain [8]. Furthermore, it has also been proposed that over 90% of enterprises believe that reasonable CSR strategies will bring both economic and social benefits [9]. Therefore, actively implementing CSR also provides a new approach for enterprises to improve their financial performance.

In recent years, a growing number of enterprises have conveyed information to stakeholders through publishing CSR reports. According to an Ernst & Young survey, 94% of organizations believe that active CSR partners are able to achieve environmental sustainability and create stable commercial benefits for them [10]. CSR reporting has emerged as a hot issue of non-mandatory information disclosure that investors and consumers are most concerned about [11]. Nevertheless, in practice, each supply chain member assumes different roles and pursues distinct interests, which leads to uneven levels of CSR information disclosure being prevalent. In the course of communicating information, as the information holder, CSR enterprises always occupy an advantageous position. On the contrary, as receivers of information, the stakeholders cannot ensure the authenticity and effectiveness of the information, but only further evaluate the production and operation conditions and economic performance of the enterprise through the passively received information. In addition, in the process of compiling CSR reports, insufficient qualitative description and quantitative indicators also cause stakeholders to be unable to obtain adequate information to a certain extent. Finally, in order to obtain more consumer recognition and support, and increase cooperation opportunities with the industry leader, enterprises usually exaggerate the degree of their investment in CSR, which also leads to stakeholders being unable to take their true CSR information. To sum up, the unidirectional information flow, the non-comprehensive and standardized basis of compiling reports, and the dissemination of misleading information collectively contribute to CSR information asymmetry in supply chains, which also affects the supply chain members’ operational performance.

Inspired by the above corporate practice background, this paper aims to study the CSR information asymmetry problem in green supply chains, and on this basis, the behavior strategy changes of both members under different information environments are discussed. The particular issues are outlined below:

- (1)

- How should the retailer control its CSR implementation level from the different operational objectives under information symmetry?

- (2)

- What is the connection between the supply chain members’ green effort ratio and their efficiency of green effort? How does information asymmetry affect the proportion of green efforts and green costs that members undertake?

- (3)

- How does the demand uncertainty factor affect the utility of CSR?

- (4)

- Under information asymmetry, how does the estimated and true CSR affect the pricing and the supply chain members’ performance?

- (5)

- What CSR implementation strategies should the retailer adopt to enhance profitability across different information scenarios, and how should the upstream manufacturer respond?

To address these research gaps, we take a two-echelon green supply chain as the research object. Considering demand uncertainty, the comparison of the manufacturer’s estimated CSR degree with the retailer’s actual CSR degree is innovatively taken as the expression of information asymmetry. Using game-theoretic modeling, four models of information symmetry without retailer CSR implementation (Model B), information symmetry with retailer CSR implementation (Model I), information asymmetry without retailer CSR implementation (Model AB), and information asymmetry with retailer CSR implementation (Model AI) are constructed. By comparing the retailer’s profit maximization and utility maximization, this paper studies the CSR behavior mechanism of the retailer under different information conditions. Furthermore, we also explore the respective revenue changes of both members in different scenarios and obtain the optimal strategy selections of the retailer in different environments.

The results of this paper reveal that under information symmetry, the retailer’s implementation of CSR practices does not necessitate a reduction in economic profit. In other words, implementing CSR within a moderate scope can enhance gains for both participants of the supply chain. This finding offers theoretical support for the retailer’s CSR activities while contributing to the CSR literature. The study further found that under information asymmetry, the retailer’s CSR behavior consistently reduces its own revenue regardless of the CSR level. In addition, for the CSR retailer, it can be seen from the comparison of decision results under different information environments that once the manufacturer cannot accurately obtain the CSR degree information, its profit will be reduced, and if it overestimates, the retailer will benefit. Finally, from a strategic perspective, if the retailer implements CSR to improve its revenue, then in the information asymmetry environment, it should actually give up implementing CSR, but pretend to fulfill CSR. Correspondingly, for the CSR retailer, it should strategically exaggerate its CSR level to make the other member overestimate it, and thus gain revenue improvement. Under the above two strategies, the manufacturer’s optimal response is moderate underestimation to reduce profit loss.

It should be noted that, based on the stakeholder theory proposed by Panda [12], this paper exogenizes CSR, in which case the retailer makes decisions with utility maximization. Internalization characterizes CSR as an investment cost expenditure, and the degree of CSR directly affects the market demand for the product. However, the method of exogenous CSR is independent of the production and operation of the supply chain and has an indirect effect on product demand by affecting corporate reputation. Therefore, from the perspective of conforming to the actual situation, it is more reasonable to externalize CSR. Furthermore, under the premise of CSR externalization, the true CSR degree of the retailer and the estimated CSR degree of the manufacturer can be quantified, so as to further explore the impact of information asymmetry on supply chain performance. However, CSR internalization cannot construct a reasonable model for behavioral strategy problems under information asymmetry. In conclusion, starting from the theoretical level and model construction, this paper conducts exogenous processing of CSR.

Table 1 maps three core research questions to three contributions, with forward pointers to later sections.

Table 1.

The research navigation for this paper.

The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 reviews the key relevant literature, points out research gaps, and outlines this study’s contributions. Section 3 describes the supply chain problem, formulates the relevant hypotheses, and defines the relevant notation. Section 4 constructs four different game models and analyzes the impact of relevant factors on optimal decisions. Section 5 examines equilibrium outcomes across varying information scenarios. Section 6 presents a numerical examination of the proposed frameworks. In Section 7, the main results obtained from the study are summarized.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Supply Chain

Mounting environmental challenges have caused academia to pay extensive attention to green supply chain problems and achieve rich results. In terms of pricing and green decisions, based on consumers’ reference behaviors, Hong et al. [13] considered green and conventional products’ competition, and further studied the pricing strategies of the products. Zhang et al. [14] considered the reference price and studied the dynamic pricing problem in the dual-channel green supply chain in both centralized and decentralized scenarios, respectively. Wu et al. [15] investigated pricing strategies and green product decisions under stochastic demand, revealing that while demand uncertainty reduces green supply chain efficiency, it can positively influence both product pricing and greenness levels. Concerning green marketing practices in supply chains, Kou et al. [16] proposed that environmental advertising can help consumers better understand the low-carbon properties of products, and green consumption awareness will be translated into actual purchasing behavior. Hong and Guo [17] compared the environmental performance of the sustainable supply chain under three different contracts and found that the product under the two-part pricing contract was the most eco-friendly, while the marketing cost-sharing contract was more favorable to the manufacturer compared with the retailer. Wang et al. [18] analyzed the government’s carbon cap-and-trade policy effect on single emission reduction and proposed the cost-sharing contract to improve the profits of both members. Mondal and Giri [19] demonstrated that supply chain performance can be enhanced through the promotion of green innovation, marketing initiatives, or a combination of both strategies. As for demand uncertainty in green supply chains, Xie et al. [20] believe that the market demand for environmentally friendly products exhibits significant volatility and stochasticity. Under the influence of multiple factors such as consumer green preference, market competition, and price, such uncertainty will affect the decisions of supply chain members. Zhao et al. [21] took into account stochastic consumer demand and studied the effect of blockchain technology on decisions in the green supply chain. Yang and Xiao [22] studied the pricing of green supply chains under government intervention based on the fuzzy uncertainty of consumer demand, and found that as the parameter ambiguity increases, the expected profit of manufacturers and systems also increases.

While the aforementioned studies have investigated supply chain issues from the perspectives of pricing, green decisions, green marketing, and demand uncertainty separately, no existing literature has integrated these four research contents within the same research framework under the context of green CSR. Enterprises enhance their brand reputation by implementing CSR, but the uncertainty of demand is widespread in the green supply chain. Therefore, starting from practice, it is very necessary to explore how the uncertainty of demand affects the implementation effect of CSR. The above literature has laid a solid foundation for this paper to analyze the role of the demand uncertainty factor in CSR, and has led to Propositions 1, 2, 5, 7, and 9 of this paper.

2.2. CSR Supply Chain

Corporate social responsibility directly affects the social image of an enterprise, which in turn affects consumers’ purchase intentions and market demand for products [23]. Ngai et al. [24] proposed that CSR practices can bring benefits to enterprises and stakeholders, including high-quality offerings, a dependable supply chain, a loyal customer base, and a positive public image. The research report of Koh et al. [25] clarifies that disclosure of CSR information to shareholders and employees can significantly ease financing constraints and enhance the sustainability of corporate innovation. Gregory et al. [26] believe that CSR has become a new source of competitiveness, which can strengthen the relationship with customers and improve the financial performance of enterprises. Although the above empirical research proved that CSR commitment positively affects enterprise performance, there are still research gaps in the theoretical modeling of CSR in the existing literature [6]. Du and Wang [27] explored the issue of CSR input between two mining production supply chains composed of a manufacturer and a retailer. Johari et al. [28] explored the impact of implementing CSR on manufacturers’ pricing strategies based on single-population evolutionary game theory. Chen and Ding [29] established a differential game dynamic model to study a competitive supply chain from the CSR perspective. Wang et al. [30] considered the dominance of the retailer and studied fairness concerns and information asymmetry effects on the reverse recycling supply chain.

In recent years, the high social concern about environmental governance issues has also prompted scholars to introduce CSR into the green supply chain. Peng et al. [31] studied the joint impact of different entities using CSR and manufacturers’ different risk preferences on corporate decision-making and utility under random demand for green products, and designed contracts to improve the inefficiency of the decentralized risk avoidance model. Ma and Lu [32] used a Stackelberg game model to analyze the triple bottom line in a low-carbon supply chain subject to a carbon tax, and found that when the retailer bears CER and CSR, the supply chain will obtain the highest profit. He et al. [3] studied the coordination issues in the omni-channel supply chain under the assumption of the CSR retailer. Chen et al. [33] considered the different CSR undertaking situations of supply chain members, studied the impact of changes in the degree of corporate social responsibility on the greenness of products and pricing decisions in the dual-channel supply chain, and achieved the coordination of profits of the two members by designing a combined contract under a franchise fee.

Similar to the above studies, this paper also takes the green CSR supply chain as the research object. However, it differs in that it focuses on the problem of CSR information asymmetry. This literature subcluster links to Propositions 1, 2, and 6.

2.3. Information Asymmetry Supply Chain

In practice, the holding of private information by supply chain participants may have adverse effects on the environment and social welfare, thus leading to undesirable consequences [11]. In terms of demand information asymmetry, Hu et al. [34] discussed six combination situations under two information structures and three power structures, and found that information asymmetry is not always harmful to supply chains. Ma et al. [35] examined the problem of information asymmetry in the three-level supply chain dynamic game, and designed a cost- and benefit-sharing contract to achieve Pareto improvements for all members. Li et al. [36] investigated the showroom effect and studied the competition and cooperation of the supply chain under information asymmetry. In terms of cost information asymmetry, Huang et al. [37] studied the problem of asymmetry of sales cost information in dual-channel supply chains and designed anti-subsidy incentive contracts to reduce channel conflicts. Ranjbar et al. [36] discussed how to design incentive contracts to induce the retailer to disclose information under asymmetric sales effort cost information. Liu et al. [38] studied the blockchain’s role in alleviating the asymmetry of quality information among supply chain channel members by constructing a supply chain composed of a single manufacturer and a single retailer. In addition to the above two most typical types of information asymmetry, Vosooghidizaji et al. [39] also discussed quality, interruption, and inventory information asymmetry according to the different natures of information. In addition, from the perspective of participants’ numbers, the information asymmetry problem can also be classified as unilateral, bilateral, or multilateral information asymmetry.

There are a few studies related to the supply chain CSR information asymmetry problem. Liu et al. [40] used the Stackelberg game to explore the CSR cost information asymmetry effect on the profits of supply chain participants and proposed to set up a compensation fund to encourage information disclosure. Vosooghidizaji et al. [11] constructed a two-echelon non-green supply chain, in which both members have CSR cost information, and analyzed the decision results of the enterprises under two different situations: information asymmetry-misreporting and information asymmetry-estimation. Ma et al. [41] considered the asymmetry CSR cost information of the manufacturer in a two-echelon supply chain, and developed a two-part tariff contract adaptable to varying information structures, aiming to enhance the retailer’s profitability while strengthening the manufacturer’s CSR commitment.

However, this literature takes the conventional supply chain as the research object and analyzes how to achieve consistent CSR information among supply chain members through contract design. Unlike these studies, our research is based on a green background and deeply explores the impact of CSR information asymmetry on the decision-making results. Most importantly, we further analyze the behavioral strategies of supply chain members in different information environments. The above literature leads to the core issue of this study and is directly linked to Propositions 3, 4, 8, and 10.

2.4. Research Gap and Contributions

In terms of research objects, most of the existing literature focuses on a single participant with green behavior, neglecting the influence of CSR on the green practices of other participants within the supply chain. In this study, not only the manufacturer’s green production but also the retailer’s green marketing are considered. Furthermore, the existing studies have largely overlooked the effect of demand uncertainty on CSR implementation results. The research elements of this paper are closely related to Liu et al. [40], Vosooghidizaji et al. [11], and Ma et al. [41]. Like them, this paper explores the CSR information asymmetry problem. Nevertheless, our research is different from theirs. Firstly, the above literature treats CSR as endogenous, analyzing the CSR cost information asymmetry in conventional supply chains. By contrast, this study adopts stakeholder theory to frame CSR as exogenous and innovatively takes the comparison between the true CSR degree of the retailer and the estimated CSR degree of the manufacturer as the expression of information asymmetry. Secondly, similar to the above literature, we also discuss the product pricing problem under CSR. The difference is that this study further examines how the manufacturer’s estimated CSR influences the product greenness, the green effort proportion, and the revenues of supply chain members under two different information asymmetry scenarios. Finally, in terms of research content, the existing studies mainly focus on how to design contracts to induce the information advantage party to disclose information, while this paper focuses on exploring the mechanism of CSR in different information environments, and discusses what behavior strategies supply chain participants should implement under different information structures and CSR conditions by analyzing the revenue changes of both members. To sum up, this study integrates demand uncertainty and information asymmetry, and implements CSR within an analytical framework, employing game theory, revealing the spontaneity and strategy of the retailer’s CSR behavior, and the research results provide some references for the strategy selection of supply chain participants in different information environments. The key distinctions between the three most relevant studies and this study are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of three most relevant studies.

3. Problem Description and Assumptions

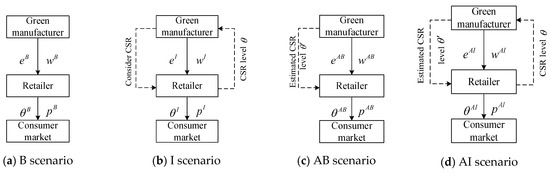

Considering the uncertainty of market demand, we take a two-echelon green supply chain composed of a manufacturer and an independent CSR retailer as the research object. To expand the sales of products, both members have made the corresponding green efforts, in which the manufacturer invests in the production of the green product to enhance its eco-friendliness and the retailer invests in green marketing activities to attract consumers to purchase the products. In the above decision system, acting as the Stackelberg game leader, the manufacturer initially determines the product greenness and sets the per-unit wholesale price. Subsequently, as the follower, the retailer decides the green marketing effort level and the per-unit retail price. This decision-making structure reflects the reality that the manufacturer has high bargaining power in the channel through its control over green technologies, and this dominant approach is widely adopted in the research of green supply chain management [1,23,27].

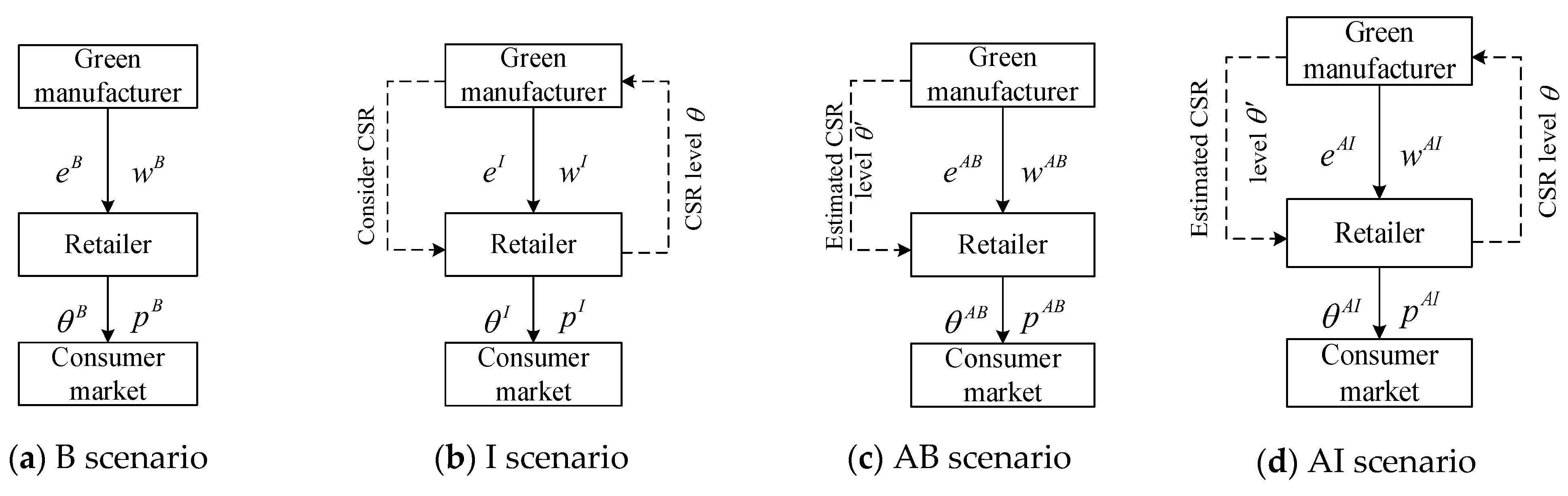

The decision-making structure of the supply chain system under different scenarios is shown in Figure 1. This paper first constructs two benchmark models (Scenarios B and I) under information symmetry. Those types of models correspond in reality to supply chains that achieve a high degree of CSR information sharing through technical means (such as blockchain traceability), authoritative third-party certifications (such as fair trade labels), or strategic alliances. For example, through the IBM Food Trust platform, Walmart effectively obtained CSR information consistent with that of upstream producers, including origin, planting process, and carbon emissions during transportation. Apple Inc. conducts in-depth audits of its internal operations and upstream suppliers through a large audit team, requiring its partners to disclose key data related to CSR, such as working conditions and environmental performance. This paper further constructs game models under information asymmetry (Scenarios AB and AI). These models offer a profound representation of the prevailing challenges in real-world supply chains, where one party faces significant difficulties in accurately observing or verifying the corporate social responsibility performance of another. Such situations are commonly seen in cooperation frameworks that rely on unilateral statements, short-term transaction relationships lacking independent verification mechanisms, or enterprises with significant supervision costs. For instance, many retailers (such as Amazon and IKEA) claim that the products they sell are “green” or “organic”. If consumers cannot fully verify the authenticity of these product claims, it will lead the enterprises into market disputes over “greenwashing”. The tragic collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh in 2013 exposed the huge reputation crisis caused by the brand’s inability to fully understand the true safety conditions of its suppliers’ factories.

Figure 1.

Decision-making structures of the supply chain in different scenarios.

Assumption 1.

The market demand for green products often shows significant fluctuations in practice. For instance, it exhibits peak season characteristics during holidays and promotional seasons, while it shows off-season features during regular periods. Referring to [42,43,44], we adopted binomial distribution to characterize the uncertainty of the potential demand. Assuming that the probability of the potential demand occurs in peak season and off-season is () and , respectively, then the expectation of this can be expressed as , where [45]. This modeling method can not only effectively capture the essential volatility of demand, but its excellent analytical properties also provide convenience for subsequent game analysis.

Assumption 2.

The green product’s market demand is affected by price, greenness, and marketing efforts. Similar to [3,16], expanding the traditional linear form, the green product market demand function is assumed as , where is the sensitivity of consumers to price, which reflects the basic law that demand decreases as the price increases. and are the marginal contributions of the greening efforts, which reflect the pulling effect of the manufacturer’s and retailer’s green efforts on product demand, while and are the product greenness and green marketing effort level. Compared with the product’s green degree and marketing efforts, the price is the most important factor influencing consumers to choose green products; therefore, the relationship , is satisfied [4,16]. In addition, taking a hypothesis to ensure that the basic market demand remains positive in the absence of green technology and marketing investment, this is in line with the reality of the consumer market.

Assumption 3.

The green effort cost functions for the manufacturer and the retailer are and , respectively, where and are the green effort cost coefficients for both parties, respectively. The above green investment cost function is characterized by convexity and an increasing marginal cost. This assumption has been widely used in the green supply chain [1,3].

Assumption 4.

Referring to the stakeholder theory [12], CSR is defined as the concern of the green product consumer surplus, which is the difference between the maximum price consumers are willing to pay and the market price that they actually pay, and determined as , where . The retailer’s utility function is , where is the retailer’s CSR level.

Assumption 5.

The green investment of the manufacturer is mainly used for the innovation of the green product technology, which does not affect the fundamental production costs. Therefore, in order to facilitate calculation, the unit production cost is normalized to zero [46]. This simplified method does not influence the relevant conclusions [47].

Assumption 6.

Supply chain participants are risk-neutral and make decisions following profit or utility maximization under different scenarios. The assumption of risk neutrality makes this study focus on the core issue of CSR behavior under information asymmetry, and the utility maximization decision fully reflects that the retailer does not only pursue pure profit.

Assumption 7.

To guarantee the objective function’s concavity and prevent trivial solutions, we make the following assumptions: , and . In addition, we use the superscript to represent four decision models with different information and different CSR modes, and the subscript to represent different members of the supply chain. Table 3 summarizes the notation used in this study.

Table 3.

Notation definitions.

4. Model Framework

In this section, game models B, I, AB, and AI are constructed and solved based on whether the retailer implements CSR and the different information conditions. In the four decision models, the manufacturer is the leader while the retailer is the follower. The overview of symbols and scenarios is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Overview of symbols and scenarios.

It should be clarified that when information is asymmetric, the retailer’s CSR degree information is not completely open and transparent, and the retailer may disguise its CSR information or exaggerate its CSR information. Under asymmetric information, the manufacturer can only guess the retailer’s CSR degree through the retailer’s decision-making behavior, and the greenness of the product and the wholesale price are determined based on the estimated CSR degree.

4.1. Without CSR Under Information Symmetry (Model B)

In Model B, as fully rational individuals, both the retailer and manufacturer pursue the maximization of economic benefit. The decision-making issues for players in the supply chain are as follows:

Proposition 1.

(i) The optimal product greenness, the green marketing effort level, the wholesale price, and the retail price in Model B are as follows:

(ii) The supply chain participants’ profits, the consumer surplus, and the retailer utility are expressed as follows:

The proof of all propositions is provided in Appendix A.

Corollary 1.

(i)

, , , .

The proof of all corollaries is provided in Appendix A.

Corollary 1 shows that in the information symmetry scenario, for the supply chain in which both parties exert green efforts in their production processes, the market demand uncertainty factor positively affects product pricing and supply chain members’ economic benefits. When product sales approach the peak season, encouraged by the high scale of potential market demand, the supply chain participants will continuously improve product greenness and green marketing level. At this time, the price of the product increases due to the improvement in quality, and the downstream retailer, which is close to the consumer market, has more room to enhance price. Remarkably, despite the retailer having an advantage in the pricing strategy, under the dominant position, the demand uncertainty factor increases the marginal profit of the manufacturer more than that of the retailer; that is, . Therefore, in the cooperation of both members, the peak season is more conducive to the manufacturer’s profit.

4.2. With CSR Under Information Symmetry (Model I)

In Model I, the manufacturer pursues the maximization of economic benefit, while the CSR retailer pursues the maximization of utility. The decision-making issues for players are as follows:

Proposition 2.

(i) The optimal product greenness, the green marketing effort level, the wholesale price, and the retail price in Model I are as follows:

(ii) The supply chain participants’ profits, the consumer surplus, and the retailer utility are expressed as follows:

Corollary 2.

(i) , , , , .

(ii) When ,; and when , .

(iii) , .

Corollary 2 shows that in the information symmetry scenario, higher CSR levels prompt the retailer to reduce prices and intensify green marketing levels to benefit the stakeholders in the supply chain channel. In response to the CSR behavior of the retailer, the dominant manufacturer will expand its green investment and enhance the wholesale price to transfer the risk of cost. While these kinds of affordable quality green products can effectively stimulate the market demand and further improve the consumer surplus, from a profitability standpoint for the supply chain members, when the retailer undertakes CSR within a certain range, the improvement in the CSR degree can positively affect the economic benefits of both members. Although the excessive focus on CSR by the retailer will encourage the manufacturer to get a free ride, the retailer’s utility always increases.

4.3. Without CSR Under Information Asymmetry (Model AB)

In Model AB, the retailer’s CSR degree information is not completely public and transparent. Therefore, by estimating the retailer’s CSR level, the manufacturer will decide the product greenness and the wholesale price, while the retailer who does not actually implement CSR will determine the final green marketing effort level and the retail price through the manufacturer’s misjudged decision results. The decision-making issues for players in the supply chain are as follows:

Proposition 3.

(i) The optimal product greenness, the green marketing effort level, the wholesale price, and the retail price in Model AB are as follows:

(ii) The supply chain participants’ profits, the consumer surplus, and the retailer utility are expressed as follows:

Corollary 3.

(i)

,

,

,

,

.

(ii)

,

.

Corollary 3 shows that in the AB scenario, with the increase in the misjudged CSR degree, the manufacturer will improve the eco-friendliness of products by inputting more investment, while the additional green costs will drive the wholesale price higher, and the improvement in the product’s green attributes will also drive the downstream retailer to further increase the marketing effort. Under the combined influence of the manufacturer’s green cost pressure transfer and the increase in its own marketing cost, the retailer who has not actually implemented CSR decides to increase the retail price to earn more revenue. The promotion of both product greenness and marketing intensity expands the market coverage to a certain extent, while also increasing the consumer surplus. For the manufacturer, since the demand expansion of green products does not meet its expectations of upfront high green cost investment, the misjudgment behavior hurts its economic performance, but the retailer benefits from it.

4.4. With CSR Under Information Asymmetry (Model AI)

In Model AI, there is no consensus on the reported CSR level of the retailer. Consequently, under the asymmetry information scenario, the manufacturer will decide the product greenness and the wholesale price by estimating the retailer’s CSR level, while the retailer who actually implements CSR will determine the final green marketing effort level and the retail price through the misjudged decision results of the manufacturer. The decision-making issues for players in the supply chain are as follows:

Proposition 4.

(i) The optimal product greenness, the green marketing effort level, the wholesale price, and the retail price in Model AI are as follows:

(ii) The supply chain participants’ profits, the consumer surplus, and the retailer utility are expressed as follows:

Corollary 4.

(i) , , , , .

(ii) , , .

Corollary 4 shows that in the AI scenario, with the increase in the true CSR level, the retailer improves the green marketing efforts and reduces the product’s market price, expecting to foster supply chain sustainability by offering concessions to both the manufacturer and consumers. At this point, due to the incomplete transparency of CSR information, the upstream manufacturer will make decisions by estimating the CSR degree of the downstream retailer. Therefore, the product greenness and wholesale price are not affected by the retailer’s true CSR level, but the combined positive effects of the retail price and marketing efforts can increase market demand to a certain extent, and raise consumer surplus accordingly.

In terms of supply chain members’ profits, the CSR estimation of the manufacturer does not affect the positive effect of the retailer’s true CSR on its economic benefit. In Scenario I, it is significant that when the retailer implements CSR within a reasonable range, the revenue of both members can be improved. Nevertheless, in the AI scenario, due to information asymmetry, the retailer’s CSR always has a negative effect on its profit. Consequently, when the implementation degree of CSR is relatively small, this ensures the transparency of information is crucial for the retailer to guarantee the favorable effect of CSR behavior on its own profit. In addition, the increase in the retailer’s true CSR level is helpful to its own utility.

Corollary 5.

(i)

, , , , .

(ii) When , ; and when , .

(iii) , .

Corollary 5 shows that the change trend of decision variables with the manufacturer’s estimated CSR level in the AI scenario is the same as in the AB scenario. In particular, the rising retail price further reflects that true CSR is the driving factor motivating the retailer to lower prices for consumer benefit. Furthermore, for the manufacturer, if the true CSR level of the retailer is higher than its estimated level, that is, the manufacturer underestimates the extent of the retailer’s CSR investment, the greater the underestimation, the lower the manufacturer’s profit. Similarly, if the retailer’s true CSR level is lower than the manufacturer’s estimated level, that is, the manufacturer overestimates the retailer’s CSR investment, the greater the overestimation, and the lower the manufacturer’s profit will be accordingly. In summary, the manufacturer’s profit will be highest only if its estimated CSR level is equal to the true CSR level. For the retailer, under the joint enhancement of the price and market demand, its economic benefits and utility will improve with the increase in the manufacturer’s misjudgment degree.

We summarize in Table 5 the influence trends of the main parameters on the supply chain decision results and the performance under the four scenarios.

Table 5.

Summary table of four scenarios’ main parameter effects.

5. Comparison and Analysis

This section first explores the impact of different information degrees and whether the retailer implements CSR on the green effort proportion and green cost proportion of supply chain members. Secondly, by comparing the performance of the supply chain under retailer profit maximization and utility maximization in the information symmetry scenario, we discuss the retailer’s CSR mechanism under information symmetry. Thirdly, by comparing the supply chain performance under retailer profit maximization and utility maximization in the information asymmetry scenario, and the supply chain performance under different information conditions when CSR is implemented by the retailer, we discuss the retailer’s CSR mechanism under information asymmetry. Finally, by comparing the influence of the market demand uncertainty factor on the equilibrium solutions under different scenarios, the effect of demand uncertainty on CSR utility is obtained.

5.1. Comparison of Green Efforts and Green Costs Under Different Scenarios

We define green effort efficiency indicators and to measure the impact of supply chain enterprises’ green efforts on market demand under the given cost. This means that if one party’s green effort makes a larger marginal contribution to the market demand, or its green effort cost is lower, or both of the above advantages apply, the enterprise’s green efforts will be more efficient, while its green production technology or green marketing scheme will be more mature and can promote the demand expansion of environmentally friendly products more effectively.

Proposition 5.

(i)

, . When , ; and when , .

(ii) , . When , ; and when , .

Proposition 5(i) indicates that when the CSR information is transparent (Scenarios B and I), comparing the green efforts of both parties is equivalent to evaluating their green effort efficiencies. Therefore, from the perspective of minimizing sustainable production and marketing costs, the party with higher efficiency should invest more green effort. In contrast to the aforementioned transparency scenarios, in the AB scenario, as well as in the AI scenario, when the manufacturer overestimates the true CSR level of the retailer, channel members’ green effort ratio is greater than their green effort efficiency ratio. This implies that under the above two cases, the proportion of the manufacturer’s green effort in the total green efforts of the supply chain increases. However, in the AI scenario, if the manufacturer underestimates the CSR degree of the retailer, the ratio of green efforts by supply chain parties falls below their green effort efficiency ratio, which implies a decreased proportion of the manufacturer’s green efforts in the overall supply chain green efforts.

Proposition 5(ii) indicates that the asymmetry of CSR information can lead to alterations in the relationship between the green effort costs of both parties. Specifically, in Scenarios AB and AI, when the manufacturer overestimates the true CSR level of the retailer, its green effort cost as a share of the supply chain’s total green effort cost increases relative to Scenarios B and I. Conversely, in Scenario AI, once the manufacturer underestimates the retailer’s CSR level, its green effort cost as a share of the supply chain’s total green effort cost decreases relative to Scenarios B and I. In conclusion, CSR information asymmetry alters both the green effort ratio and the green cost ratio between the members within the supply chain.

5.2. Analysis of CSR Mechanism Under Information Symmetry

Proposition 6.

(i)

, , , , .

(ii) When , ; and when , .

(iii) , .

Proposition 6 indicates that, compared to the scenario without CSR, the retailer’s CSR behavior not only enhances the greenness of products and intensifies marketing efforts but also lowers the retail price. Furthermore, the price reduction generates a greater consumer surplus. For the retailer, when the CSR level remains small, the demand increase can compensate for the decline in its marginal revenue and the increase in its marketing costs; thus, its economic benefit enhances. However, when CSR input is large, the decline in marginal revenue has the dominant effect. Consequently, the retailer’s economic benefit is damaged. In addition, since the combined increase in environmental benefits and consumer surplus compensates for the profit loss, the retailer’s utility is enhanced. To sum up, both consumers and the environment can benefit from the CSR behaviors of the retailer, which also promote the green transformation and sustainable development of enterprises.

Proposition 7.

(i) , , , .

(ii) . When , ; and when , .

Proposition 7 discusses the impact of the demand uncertainty factor on the CSR implementation effect. Proposition 7(i) indicates that when the retailer implements CSR, the greenness of the product, green marketing effort level, and wholesale price are all more sensitive to the peak season than in the scenario without CSR, while the product’s retail price is the opposite. Proposition 7(ii) finds that the supply chain members’ revenue also has a similar change trend; that is, when the CSR level of the retailer is low, compared to the scenario in which the retailer does not implement CSR, the peak season is more conducive to the profits of both members. The findings from Proposition 7 indicate that the peak season promotes the utility of CSR behavior for the green supply chain, while the off-season inhibits this effect for both parties.

5.3. Analysis of CSR Mechanism Under Information Asymmetry

Proposition 8.

(i)

, , , , .

(ii) , , .

Proposition 8 indicates that when the information is asymmetric, the greenness and wholesale price of products provided by the manufacturer will not change irrespective of the retailer’s CSR implementation, which also misleads the downstream CSR retailer to increase its marketing effort and lower its retail price to benefit the manufacturer and consumers more. Therefore, the manufacturer’s profit and the retailer’s own utility are enhanced in the AI scenario. However, the retailer’s excessive concession makes its revenue lower than that in the AB scenario.

The result of Proposition 8 reveals that when the information is asymmetric, the retailer implementing CSR will be more conducive to the expansion of market demand for green products. However, no matter how much CSR is input, the retailer’s own profit always decreases. Therefore, if the retailer implementing CSR intends to improve its own revenue, then investigating the accuracy and transparency of information transmission is the precondition.

Proposition 9.

(i)

, , , .

(ii) , .

Similar to Proposition 7, from the perspective of revenue, Proposition 9 finds that, compared with the retailer inputting CSR, in the scenario without CSR, the manufacturer’s response to the demand uncertainty factor will be more sluggish, whereas the retailer’s response will be more sensitive. Thus, in the context of information asymmetry, the increase in potential market demand will promote the effect of “benefiting others but hurting oneself” from the retailer’s CSR behavior, whereas the decrease in potential demand will weaken both effects.

Proposition 10.

(i) When , , , , , , , , .

(ii) When , , , , , , , , .

Proposition 10 indicates that if the retailer undertakes CSR, the manufacturer’s misjudgment of the CSR level differently influences the supply chain performance. Proposition 10(i) finds that when the manufacturer underestimates the CSR degree, both the greenness and the product’s wholesale price will decline. At this time, the eco-friendliness of the products provided by the manufacturer is lower than that expected by the downstream CSR retailer. Therefore, it will choose to decrease the marketing effort for green products. Meanwhile, to counteract declining demand due to lower greenness, the retailer will lower the price. Ultimately, the shrinking of the green products’ market demand takes the dominant effect, although the cost of green investment of the manufacturer decreases, and its total revenue is hurt. Consequently, the retailer also loses more profit than under the information symmetry scenario, and its utility is accordingly reduced.

Conversely, Proposition 10(ii) finds that when the manufacturer overestimates the CSR degree, the product greenness and the wholesale price will improve. Correspondingly, the increased eco-friendliness of products encourages the downstream retailer to strengthen the marketing efforts. Nevertheless, due to the asymmetry of information, the retailer’s true CSR level at this time is lower than the manufacturer’s estimate. Therefore, in terms of pricing, the retailer will adjust the retail price upwards. Ultimately, the growth in the market demand for green products takes the dominant effect, which enhances the retailer’s profit relative to the information symmetry scenario. However, the manufacturer’s economic benefit is still reduced owing to the excessive green cost investment caused by its misjudgment. To summarize, when the retailer implements CSR, once the manufacturer cannot accurately obtain the degree information, its revenue will decline, and if overestimated, the retailer will benefit.

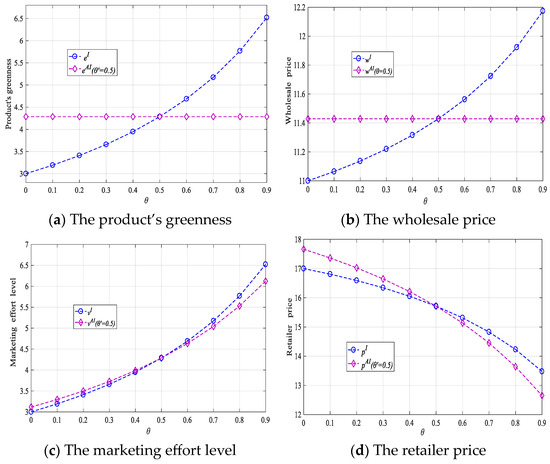

6. Numerical Analysis

This section discusses the mechanism of CSR under different information environments and further obtains the supply chain members’ behavior strategies. Referring to Wang et al. [47], the parameters are taken as follows: , , , , , , , , and the range of and is .

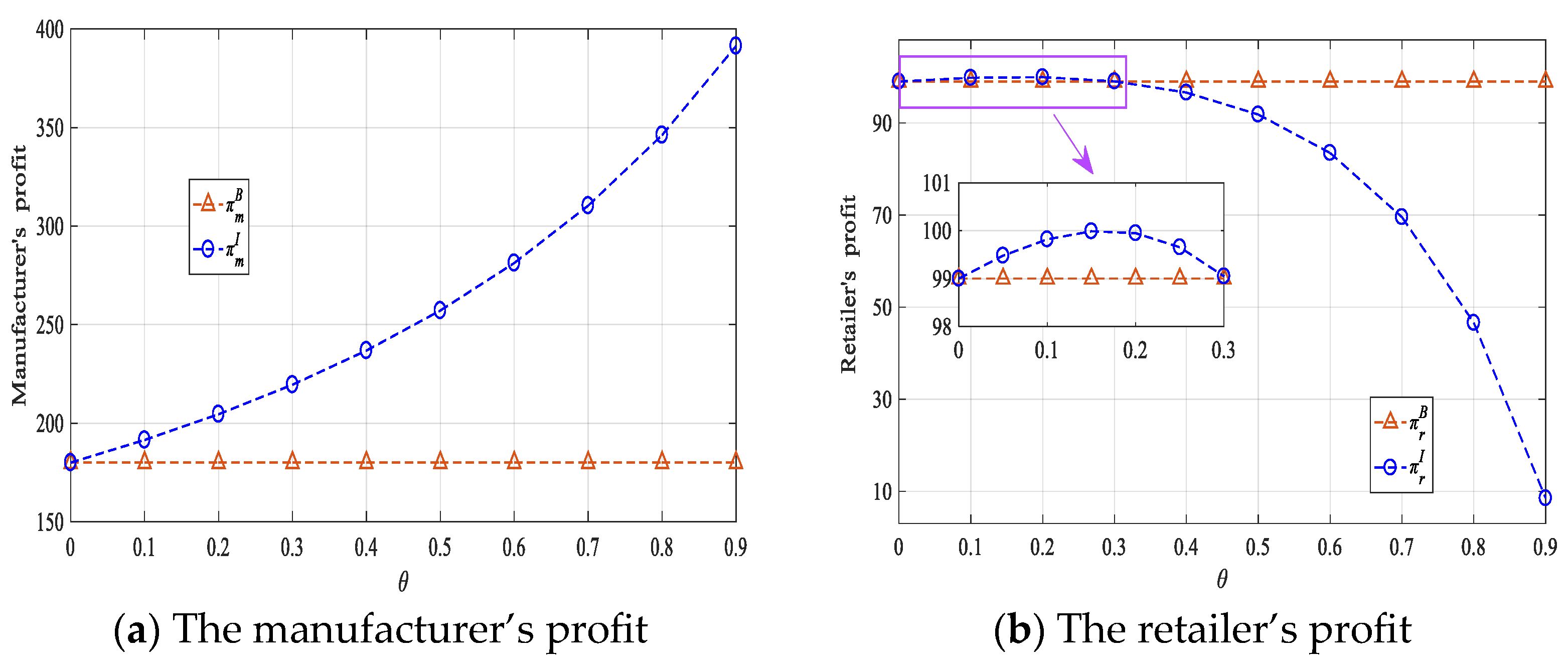

6.1. CSR Mechanism Under Information Symmetry

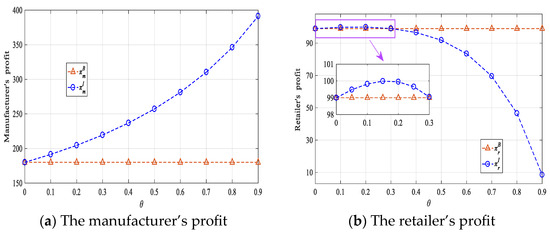

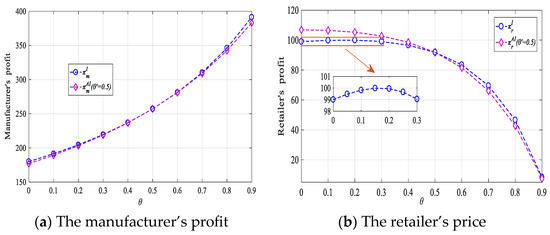

Figure 2 indicates that when the CSR implementation level is relatively lower (), the retailer’s own profit is also improved. In this range, with the growth of , its profit initially rises and then falls; when the trend turns, the threshold of the CSR level is 0.1667. Different from the above, when the CSR implementation level is relatively higher (), with the increase in , the retailer’s own profit will suffer a more significant decline. For the manufacturer, the retailer’s CSR implementation is consistently conducive to its profit growth, and the higher the level of CSR implementation, the faster its profit growth.

Figure 2.

Impact of on the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s profits under symmetric information scenarios.

The above analysis shows that in the information transparency environment, by implementing CSR within appropriate bounds, the retailer’s CSR behavior can effectively stimulate market demand and optimize the economic benefits of both members. The above conclusion further confirms the view put forward by Vickers [47] that maximizing the non-economic profit objective of enterprises contributes to improving their economic revenue. The excessive implementation of CSR will reduce the profit margin of the retailer, but this behavior always contributes to increasing the products’ eco-friendliness and raises the influence of brands. Therefore, enterprises should combine their development objectives with reasonable control over the degree of implementation of CSR, and maintain a balance between economic revenue and sustainable development.

6.2. CSR Mechanism Under Information Asymmetry

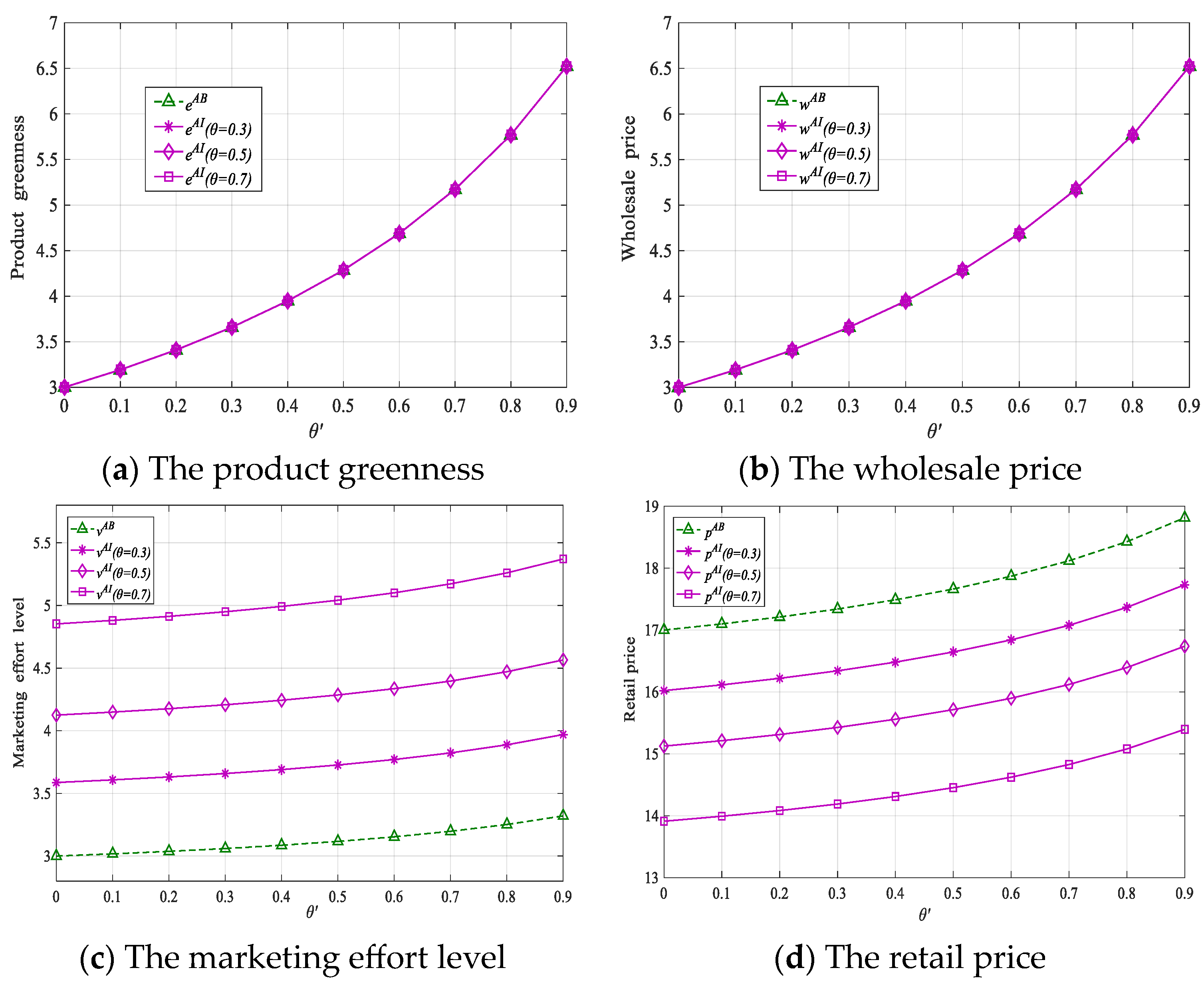

6.2.1. Comparison of Whether the Retailer Implements CSR Under Information Asymmetry

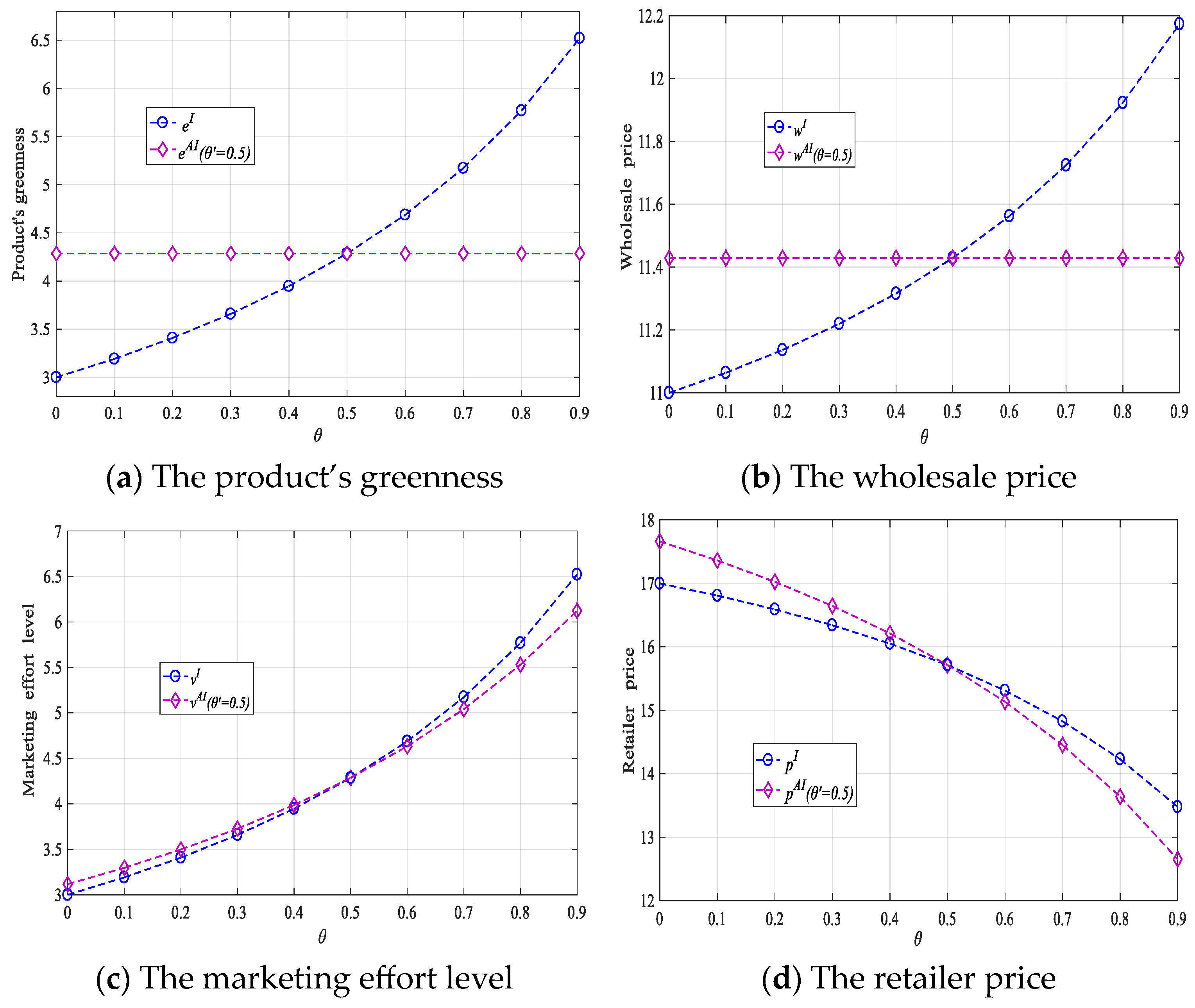

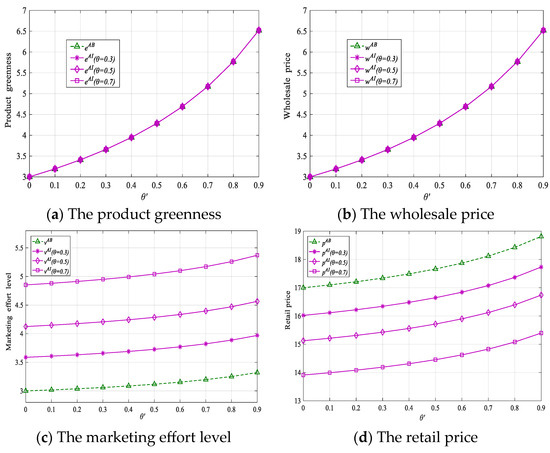

Figure 3 illustrates that in the context of asymmetry information, irrespective of the CSR choice of the retailer, as the estimated CSR degree increases, the manufacturer will choose to improve the product’s environmental performance and simultaneously increase the wholesale price to grab more profit. Since the manufacturer will make its optimal decisions based on the estimated CSR in the AB and AI scenarios, the greenness and wholesale price of the product are equal in both scenarios. Corresponding to the manufacturer’s choice, under the two scenarios, with the increase in estimated CSR, the retailer will further strengthen the marketing effort and raise the retail price. Different from the above, in the AI scenario, with the increases in the true CSR degree, the retailer will improve the concession to stakeholders, thus deciding to strengthen the product’s marketing effort and lower the retail price. It is worth noting that no matter how the value changes for the estimated CSR and the true CSR, the product’s retail price is consistently lower in the AI scenario, while its marketing level is higher than in the AB scenario.

Figure 3.

Impact of on the optimal decisions in the AI and AB scenarios.

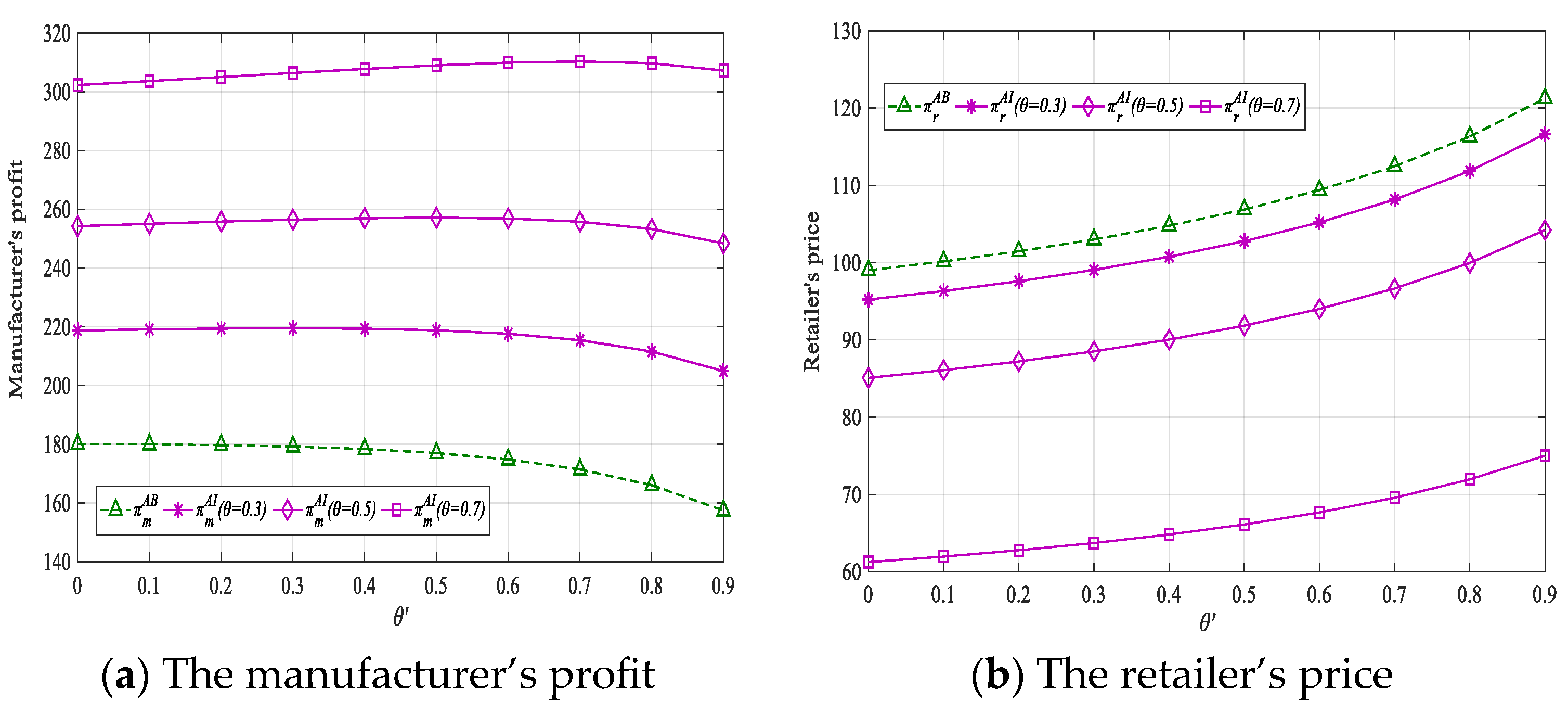

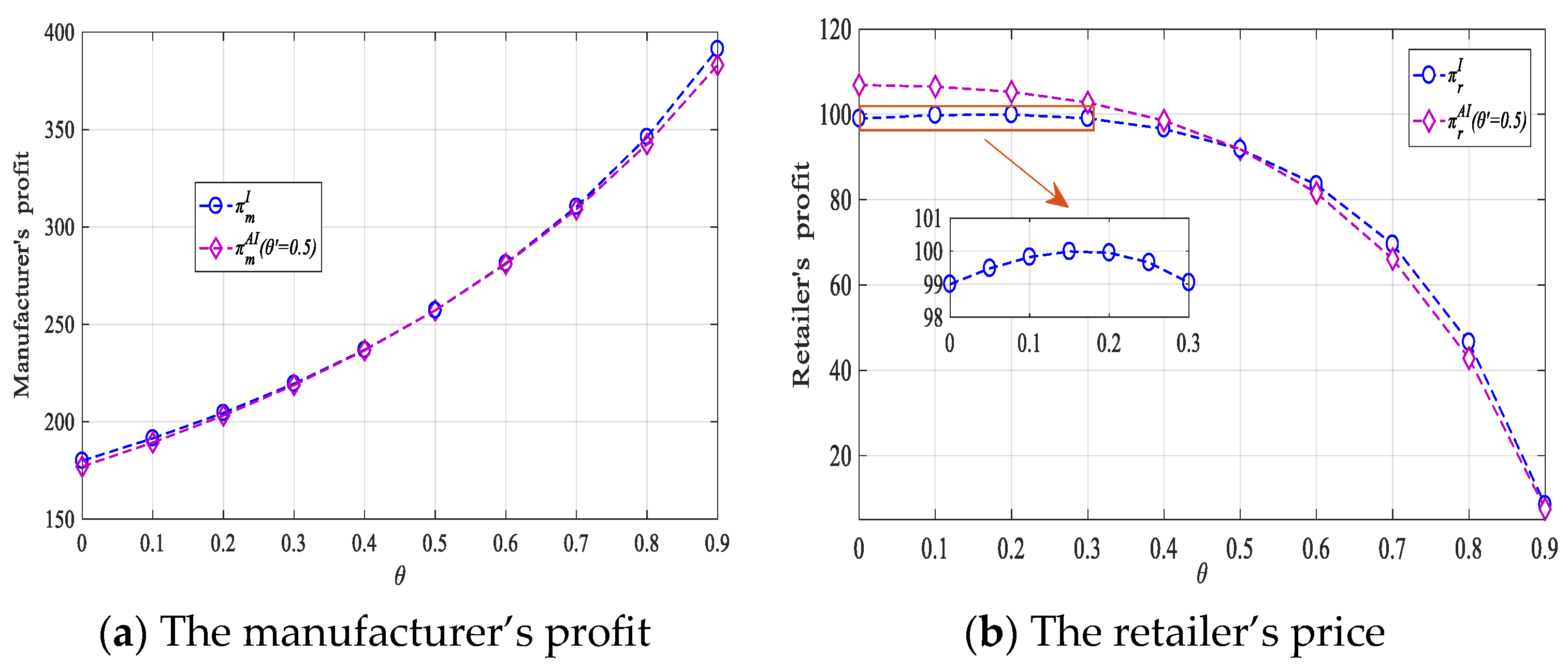

Figure 4a demonstrates that in the CSR information asymmetry environment, the higher the estimated CSR level without actual implementation by the retailer, the greater the corresponding decline in the manufacturer’s profit. However, when the retailer undertakes CSR, the impact of the manufacturer’s estimated level of CSR on its own profits depends on the relative size of the true value and the estimated value. Specifically, when the manufacturer underestimates the retailer’s true CSR level, with the increase in the misestimated CSR level, its profit improves. Conversely, when the manufacturer overestimates the CSR inputs of the retailer, its profit will be negatively impacted by the misestimated CSR. In other words, the manufacturer’s revenue can only be maximized if the estimated CSR level is equal to the true CSR level. Moreover, in the AI scenario, with the increase in the true CSR level, the manufacturer’s profit will continue to grow, and no matter how the true and estimated CSR values change, the manufacturer’s profit in the AI scenario is consistently higher than in the AB scenario. From the above conclusion, it can be seen that in the asymmetric information environment, the increase in the manufacturer’s profit is still attributed to the retailer’s concession.

Figure 4.

Impact of on the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s profits under Scenarios AI and AB.

Figure 4b shows that under CSR information asymmetry, the manufacturer’s overestimation of the retailer’s CSR level consistently benefits the retailer’s economic performance, irrespective of actual CSR implementation or its extent, and the increased profit range of the retailer under the AB scenario is higher than that under the AI scenario. Additionally, in the AI scenario, the profit of the retailer falls as its true CSR level increases. By comparing the profits of the retailer in the AI and AB scenarios, it can be seen that regardless of how the true value and estimated value of CSR change, the profit of the retailer in the AB scenario is always higher than that in the AI scenario. To further summarize the above findings, from a strategic perspective, if the retailer intends to increase its own profit by implementing CSR in a certain degree, it may use information asymmetry to pretend to implement CSR in behavior and simultaneously exaggerate the CSR level to obtain more revenue.

6.2.2. Comparison of Different Information Environments for the CSR Retailer

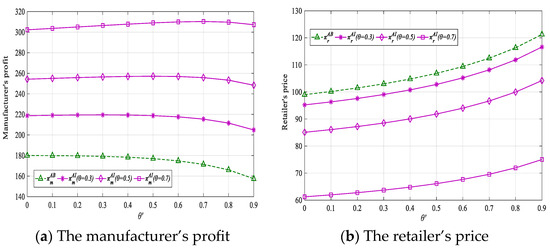

In this section, under different values of , supply chain members’ performances under the AI and I scenarios have similar change trends and relationships. Therefore, to present the conclusions more clearly, we take as an example.

According to Figure 5, it can be seen that when the retailer undertakes CSR, regardless of the symmetry of CSR information, with the true CSR level increasing, the retailer in both the AI and I scenarios will strengthen the marketing of green products as well as lower the retail price. At this time, the upstream manufacturer who receives the true extent of the retailer’s concession information will choose to enhance the eco-friendliness of the product and increase the wholesale price. Accordingly, the manufacturer who has not received the true extent of the retailer’s concession information will make decisions by estimating the CSR level of the retailer. Thus, the wholesale price and product greenness in the AI scenario are not affected by the retailer’s true CSR level.

Figure 5.

Impact of on the optimal decisions in the AI and I scenarios.

Then, the optimal decisions under the AI and I scenarios are compared. As shown in Figure 5, in the case where the manufacturer overestimates the CSR level () of the retailer, compared with Scenario I, the greenness of products, wholesale prices, green marketing investment, and retail prices in the AI scenario will all be higher. The manufacturer’s reinforced decision-making stems from an overestimation of the retailer’s concessions. Although the enhancement of the product’s green attributes encourages the retailer to improve its marketing effort, in terms of pricing, the price of the retail product in the AI scenario is higher than in the I scenario due to the fact that the retailer’s concession fell short of the manufacturer’s expectations. Conversely, when the estimated level of the manufacturer is lower than the true level of the retailer (), the product greenness, wholesale price, green marketing level, and retail price in the AI scenario are all lower than in the I scenario. The key driver behind these results is that the underestimation of the retailer’s concession induces the manufacturer to reduce its decision strength to a certain extent. At this time, since the eco-friendliness of green products does not meet the expectation of the downstream retailer, the retailer correspondingly reduces the marketing intensity to diminish green expenditure and simultaneously uses the low-price strategy to avoid excessive product demand shrinkage.

Figure 6a demonstrates that the profit of the manufacturer consistently increases with the true level of CSR, whether the CSR information is symmetric or not. According to Figure 6b, when the manufacturer can accurately capture the CSR degree information of the retailer, that is, when the information is symmetric, the retailer can effectively improve its own revenue by implementing CSR within a certain range (). However, under the information asymmetry scenario, the retailer’s CSR activities consistently reduce its profitability.

Figure 6.

Impact of on the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s profits under Scenarios AI and I.

For the CSR retailer, in an information asymmetry situation, if the manufacturer overestimates the true CSR level, the retailer’s profit will be higher than in Scenario I. Conversely, if the manufacturer underestimates the true CSR level, the profit of the retailer will be correspondingly lower than in Scenario I. The above results of estimation will trigger a strategic behavior for the retailer. Specifically, if the retailer wants to improve its benefit by implementing CSR, then it can strategically exaggerate the CSR level and use the information deviation to make the manufacturer overestimate. In addition, when the retailer exaggerates its CSR input, the actual CSR degree should not be too large; otherwise, it will lead to detrimental effects on its profit. However, at this time, for the manufacturer, both overestimation and underestimation are detrimental to its economic benefit. Therefore, which strategy should it adopt to reduce loss when facing the retailer’s announced untrue CSR level? To solve this problem, we compare the profit losses of the manufacturer () with the same extents of overestimation and underestimation, and obtain the results shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

The impact of the estimation on the manufacturer’s profit.

From Table 6, it can be seen that both overestimation and underestimation of CSR have adverse effects on the manufacturer’s profit to varying degrees, while, under the same trend of misestimation, with the increase in the misestimation degree, the manufacturer will lose more. What is more important is that when the degrees of overestimation and underestimation are the same, the loss of the manufacturer under overestimation will be greater. Consequently, if the manufacturer is unable to accurately obtain the retailer’s true CSR level, a moderate underestimation is more favorable.

6.3. Strategy Analysis of Supply Chain Members

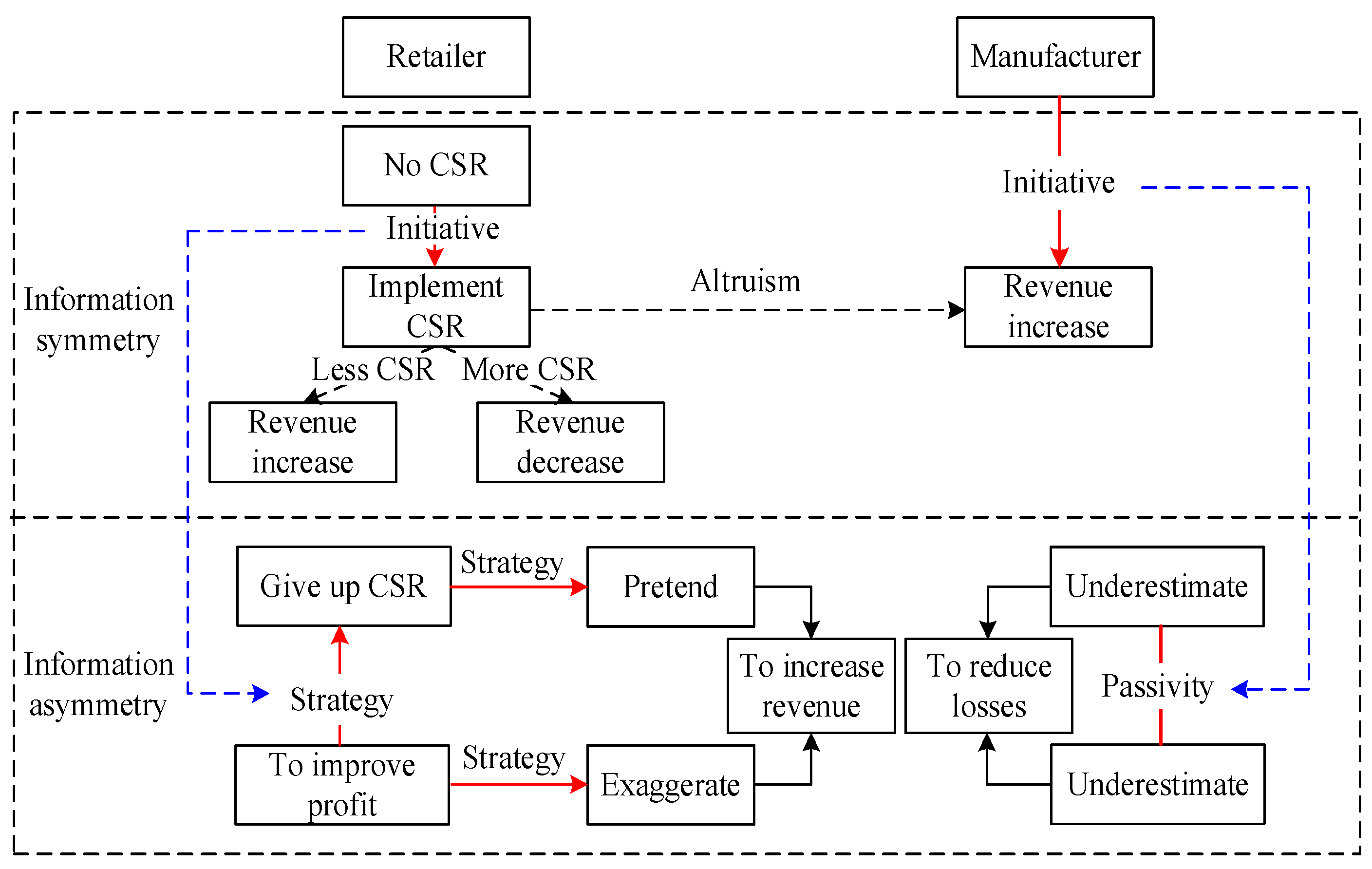

By summarizing the analysis in Section 6.1 and Section 6.2, we can conclude the following:

- (1)

- In the case of information symmetry, the retailer implements CSR to a certain extent, which has a “benefit oneself and others” effect. Nevertheless, excessive CSR implementation harms the retailer’s economic performance, even though both its utility and the manufacturer’s profit are boosted.

- (2)

- When the information is asymmetric, the manufacturer is unable to accurately obtain the CSR degree information of the retailer. At this time, the CSR behavior of the retailer consistently compresses its own profit space, but is always conducive to its own utility and the manufacturer’s revenue.

- (3)

- In the presence of information asymmetry, for the CSR retailer, once the manufacturer cannot accurately estimate the other member’s CSR level, its own revenue will be reduced. Further, overestimation is more unfavorable than underestimation.

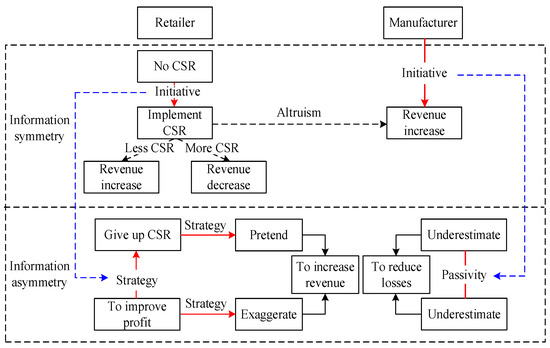

Furthermore, through the above summary of the retailer’s CSR mechanism under information symmetry and information asymmetry, combined with the relevant corollary analysis, from the perspective of strategic behavior for both members, the following conclusion can be drawn.

When the information is symmetric, if the retailer wants to improve its own economic profit by implementing CSR, then inputting CSR to a relatively small extent is the best choice. However, if the operational objective of the retailer is to promote sustainable development to a greater extent and strengthen the partnership within the supply system, then it needs to improve the CSR level as much as possible.

When information is asymmetric, the retailer’s profit is always damaged regardless of its own CSR input level. Therefore, from a strategic point of view, if the retailer implementing CSR intends to improve its revenue, it may use information asymmetry to achieve the goal. Specifically, in an information asymmetry environment, the retailer may choose to give up implementing CSR in reality but pretend to fulfill CSR in behavior, and thus use information asymmetry to induce the manufacturer to overestimate the CSR that does not actually exist. At this time, for the manufacturer, despite the profit loss being inevitable, it should choose to moderately underestimate to diminish the cost of green investment and reduce its own revenue loss.

For the CSR retailer, by comparing the different information environments’ results, we can obtain that only when the manufacturer overestimates the CSR level will the economic benefit of the retailer under information asymmetry be enhanced. In the contrary scenario, it is diminished. At this time, if the retailer’s starting point in implementing CSR is to increase its own revenue, it should strategically exaggerate the CSR level. For the manufacturer, due to the information deviation, both overestimation and underestimation have adverse effects on its revenue, while overestimation will lead to more loss. Consequently, the manufacturer’s strategy is to moderately underestimate to avoid more losses.

Figure 7 shows the CSR implementation strategies of the retailer and the response strategies of the manufacturer under different information environments.

Figure 7.

Behavior strategies for supply chain members.

7. Conclusions

This paper takes a two-echelon supply chain in which both the manufacturer and the retailer are involved in green efforts as the research object. According to different information conditions and whether the retailer implements CSR, this paper investigates product prices and green decisions under four game models. In addition, the impact of the market demand uncertainty factor, true CSR, and estimated CSR on supply chain performance is explored. Finally, through the discussion of the retailer’s CSR mechanism under different information environments, the optimal strategic behavior of both members is further obtained.

The main conclusions are the following:

- (1)

- Under conditions of information symmetry, when the CSR effort of the retailer is modest, the economic benefits of both members are enhanced. However, when the retailer commits to a high level of CSR, its profitability may be eroded.

- (2)

- When the retailer undertakes CSR, if the manufacturer overestimates the CSR level, information asymmetry will cause it to bear a higher share of green efforts and green costs than symmetric information. However, when the manufacturer underestimates the true CSR level, it has the opposite effect.

- (3)

- For the retailer that is intensely concerned about its own economic benefit, the accurate transmission of information is the foundation for its input in CSR.

- (4)

- From the perspective of strategic behavior, when the information is asymmetric, implementing CSR consistently has a negative impact on the retailer’s revenue. Therefore, if its objective in implementing CSR is to improve its own economic benefit, it should actually give up implementing CSR, while strategically taking advantage of information asymmetry to disguise and exaggerate its CSR implementation level to gain profit enhancement. At this time, the manufacturer should moderately underestimate to reduce its loss.

- (5)

- If the retailer’s objective in implementing CSR is to improve own economic benefit, then the effective strategy is to exaggerate its CSR level. At this time, the coping strategy of the manufacturer is to moderately underestimate to avoid greater loss.

- (6)

- The market demand uncertainty factor contributes to the retailer’s CSR effect during the peak season but inhibits it in the off-season.

This study helps managers understand how CSR information asymmetry affects supply chain members’ economic performance, enabling them to formulate appropriate response strategies. The findings offer the following managerial insights:

- (1)

- The retailer should make full use of the “altruism” attribute brought by implementing CSR to attract and select competitive strength partners, adjust the product structure, and accelerate the green transformation of the enterprise.

- (2)

- When the retailer implements CSR, information asymmetry will lead to the manufacturer as a stakeholder being unable to derive profit enhancement. To avoid this adverse situation, the manufacturer should make full use of its dominance and actively promote the relevant participants in the supply chain channel to combine the quantitative indicators and qualitative descriptions, thereby forming standardized and transparent standards related to CSR, thus alleviating the negative impact brought by information asymmetry.

- (3)

- If the retailer implements CSR to improve its own economic benefits to a certain extent, it should be fully aware of the information environment through market research beforehand to ensure that its CSR degree information can be accurately transmitted to other members. Accordingly, the retailer’s pursuit of CSR for supply chain sustainability often comes at a substantial cost to its own economic performance. At this time, breaking the information barrier and fully disclosing the CSR degree information enables the supply chain system to work in a benign operating environment, which is more consistent with the long-term development planning of both parties.

- (4)

- As for information symmetry, the government should comprehensively take into account the CSR development level of each region as well as the laws and regulations, accelerate the construction of a local CSR indicator system, providing a basis for enterprises to disclose true CSR information through reports, and further avoid the loss of economic benefits caused by misestimation of information.

- (5)

- Under information symmetry, the supply chain members’ ratio of green efforts is equivalent to the ratio of their effort efficiencies. In order to maximize the environmental benefits of the supply chain system, both members can negotiate to make the party with higher demand expansion capacity or lower investment cost contribute more green efforts.

There exist certain limitations associated with this study. Firstly, this paper only considers the unilateral information asymmetry caused by the retailer’s CSR information transmission process. Nevertheless, there are also situations in which both members implement CSR. Hence, bilateral CSR information asymmetry can be further explored. Secondly, the signaling game in information economics can describe the CSR information transmission process from a dynamic perspective, and subsequent work can start from this theory to study CSR information disclosure in the green supply chain. Finally, this study focuses on the issue of CSR information asymmetry in the green supply chain, particularly under the manufacturer’s dominance. In reality, there are also situations where the retailer takes the lead or decisions are made jointly by both parties. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the above problem under these two power structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L.; methodology, Z.L.; software, W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L. and Z.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71361018).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in [AIMS] at [10.3934/jimo.2024033], reference number [47].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Proposition 1.

According to the inverse solution method of the Stackelberg game, the Hessian matrix of with respect to and is as follows:

Because of and , , . Hence, the Hessian matrix is negative definite. Therefore, is jointly concave with respect to and . The following equations are solved simultaneously: , . The optimal response functions of and can be obtained as follows: , .

Substituting the above response and into Formula (1), we can obtain the manufacturer’s profit function as

From Equation (A1), the Hessian matrix of with respect to and is as follows:

Based on the condition that and , we can obtain , . Hence, the Hessian matrix is negative definite. Therefore, is jointly concave with respect to and . The following equations are solved simultaneously: and . and can be obtained. Then, and are substituted into and to get and . According to the equilibrium solutions, we can obtain the supply chain members’ profit, the consumer surplus, and the retailer utility. □

The proof method of Proposition 2 is similar to Proposition 1, and is omitted.

Proof of Corollary 1.

Therefore, we obtain and . □

The proofs of , , , , and are similar to the above. In addition, similar to the proof methods of Corollary 1, the proofs of Corollaries 2–5 are omitted.

Proof of Proposition 3.

In Model AB, the manufacturer guesses the retailer’s CSR level is . Therefore, it considers the retail price and marketing effort level as , , and further takes the above misestimated and into its profit function to make decisions. Then, we get and (the solution method for this part is similar to Proposition 2).

But in fact, the retailer optimizes its decisions for maximum profitability. Similar to Proposition 1, the retailer’s actual response functions are derived as follows: , . Then, taking and into the above response functions, we can obtain and . Finally, the members’ profits and the consumer surplus are obtained. □

Proof of Proposition 4.

In Model AI, the manufacturer guesses that the retailer’s CSR level is , and based on the estimated value, its makes the decisions of and (the solution method for this part is similar to Proposition 3; therefore, we can obtain , ). But actually, the retailer implements CSR with level , and makes decisions to maximize utility. Therefore, the true response functions of the retailer about and are and (the solution method for this part is similar to Proposition 2). Then, applying and to the above response functions, we can obtain and . Finally, the members’ profits and the consumer surplus are obtained. □

Proof of Proposition 5.

- Proposition 5(i):

, , , .

Let ; from , we take ; in a further step, since , we have . Finally, we can obtain .

Let ; from , we take ; in a further step, when , from , we can take . Therefore, we can obtain , and when , from , we can take . Therefore, we can obtain . □

The proof method of Proposition 5(ii) is similar to Proposition 5(i).

Proof of Proposition 6.

where , , , .

From , we can take that when , , and when , . We need to determine the sign of A.

Furthermore, we need to discuss the sign of . From , we can take . Then we can obtain . □

The proofs of , , , , , and are similar to the above.

In addition, the proof methods of Propositions 7–10 are similar to Proposition 6, and are omitted.

References

- Wang, S.J.; Liu, L.Z.; Wen, J. Product pricing and green decision-making considering consumers’ multiple preferences under chain-to-chain competition. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 152–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Zhang, C. A dynamic analysis of a green closed-loop supply chain with different on-line platform smart recycling and selling models. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.H.; Jiang, J.X.; Hu, W.F. Cross effects of government subsidies and corporate social responsibility on carbon emissions reductions in an omnichannel supply chain system. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 175, 108872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.X.; Zhong, Y. Carbon emission reduction and green marketing decisions in a two-echelon low-carbon supply chain considering fairness concern. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2023, 38, 905–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkila, T.; Sarna, B. A systematic literature review on employee relations with CSR: State of art and future research agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.H.; Zhao, W.F.; Zhang, Z.C. Impacts of CSR implementation and channel leadership in a socially responsible supply chain. Kybernetes 2022, 52, 4197–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, U.; Oscar, T.F.; Paulus, S.K. On the Nexus Between CSR Practices, ESG Performance, and Asymmetric information. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2020, 22, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.J.; Leung, C.; Miao, C.Y. Selling format choices in e-commerce platform considering green investment and corporate social responsibility. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 193, 110299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Bashir, J. How does corporate social responsibility transform brand reputation into brand equity? Economic and noneconomic perspectives of CSR. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Liu, S.; Yao, F.M. Pricing and recovery strategies for bidirectional-competition closed-loop supply chains with CSR awareness. J. Syst. Eng. 2021, 36, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vosooghidizaji, M.; Taghipour, A.; Canel-depitre, B. Coordinating corporate social responsibility in a two-level supply chain under bilateral information asymmetry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Modak, N.; Basu, M. Channel coordination and profit distribution in a social responsible three-layer supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 168, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.F.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.G. Green product pricing with non-green product reference. Transp. Res. Part E Logisfics Transp. Rev. 2018, 115, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Han, G. Two-stage pricing strategies of a dual-channel supply chain considering public green preference. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.L.; Schutter, B.D.; Rezaei, J. Decision analysis and coordination in green supply chains with stochastic demand. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2023, 10, 2208277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.F.; Liu, H.; Gao, H.H. Cooperative emission reduction in the supply chain: The value of green marketing under different power structures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 68396–68409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Z.; Guo, X. Green product supply chain contracts considering environmental responsibilities. Omega 2019, 83, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.R.; Brownlee, A.; Wu, Q.H. Production and joint emission reduction decisions based on two-way cost-sharing contract under cap-and-trade regulation. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 146, 106549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, C.; Giri, B.C. Pricing and used product collection strategies in a two-period closed-loop supply chain under greening level and effort dependent demand. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Ma, J.H.; Goh, M. Supply chain coordination in the presence of uncertain yield and demand. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 4342–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.W.; Jin, S.; Gao, P. Dynamics analysis of green supply chain under the conditions of demand uncertainty and blockchain technology. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.Y.; Xiao, T.J. Pricing and green level decisions of a green supply chain with governmental interventions under fuzzy uncertainties. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1174–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, L.Z.; Li, W.X. Stability analysis of supply chain members time delay decisions considering corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 2024, 53, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]