Abstract

In this paper, we develop a fast numerical algorithm, termed MDI-LR, for the efficient implementation of quasi-Monte Carlo lattice rules in computing d-dimensional integrals of a given function. The algorithm is based on converting the underlying lattice rule into a tensor-product form through an affine transformation, and further improving computational efficiency by incorporating a multilevel dimension iteration (MDI) strategy. This approach computes the function evaluations at the integration points collectively and iterates along each transformed coordinate direction, allowing substantial reuse of computations. As a result, the algorithm avoids the need to explicitly store integration points or compute function values at those points independently. Extensive numerical experiments are conducted to evaluate the performance of MDI-LR and compare it with the straightforward implementation of quasi-Monte Carlo lattice rules. The results demonstrate that MDI-LR achieves a computational complexity of order or better, where N denotes the number of points in each transformed coordinate direction. Thus, MDI-LR effectively mitigates the curse of dimensionality and revitalizes the use of QMC lattice rules for high dimensional integration.

Keywords:

lattice rule (LR); multilevel dimension iteration (MDI); Monte Carlo (MC) and Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) methods; high dimensional integration MSC:

65D30; 65D40; 65C05; 65N99

1. Introduction

Numerical integration is an essential tool and building block in many scientific and engineering fields which requires to evaluate or estimate integrals of given (explicitly or implicitly) functions, which becomes very challenging in high dimensions due to the so-called the curse of dimensionality (CoD). They are seen in evaluating quantities of stochastic interests, solving high dimensional partial differential equations, or computing value functions of an option of a basket of securities. The goal of this paper is to develop and test an efficient algorithm based on quasi-Monte Carlo methods for evaluating the d-dimensional integral:

for a given function and .

Classical numerical integration methods, such as tensor product and sparse grid methods [1,2] as well as Monte Carlo (MC) methods [3,4] require the evaluation of a function at a set of integration points. The computational complexity of the first two types of methods grows exponentially with the dimension d in the problem (i.e., the CoD), which limits their practical usage. Monte Carlo (MC) methods are often the default methods for high dimensional integration problems due to their ability of handling complicated functions and mitigating the CoD. We recall that the MC method approximates the integral by randomly sampling points within the integration domain and averaging their function values. The classical MC method has the following form:

where denotes independent and uniformly distributed random samples in the integration domain . The expected error for the MC method is proportional to , where stands for the variance of f. If f is square-integrable then the expected error in (2) has the order (note that the convergence rate is independent of the dimension d). Evidently, the MC method is simple and easy to implement, making them a popular choice for many applications. However, the MC method is slow to converge [5,6], especially for high dimensional problems, and the accuracy of the approximation depends on the number of random samples. One way to improve the convergence rate of the Monte Carlo method is to use quasi-Monte Carlo methods [7,8].

Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) methods [9,10] employ integration techniques that use point sets with better distribution properties than random sampling. Similar to the MC method, the QMC method also has the general form (2), but, unlike the MC method, the integration points are chosen deterministically and methodically. The deterministic nature of the QMC method could lead to guaranteed error bounds and that the convergence rate could be faster than the order of the MC method for sufficiently smooth functions. QMC error bounds are typically given in the form of Koksma-Hlawka-type inequalities as follows:

where is a (positive) discrepancy function which measures the non-uniformity of the point set and is a (positive) functional which measures the variability of f. Error bounds of this type separate the dependence on the cubature points from the dependence on the integrand. The QMC point sets with discrepancy of order or better are collectively known as low-discrepancy point sets [11].

One of the most popular QMC methods is the lattice rule, whose integration points are chosen to have a lattice structure, low-discrepancy, and better distribution properties than random sampling [12,13,14], hence, resulting in a more accurate method with faster convergence rate. However, traditional lattice rules still have limitations when applied to high dimensional problems. Good lattice rules almost always involve searching (cf. [15,16]), the cost of an exhaustive search (for n fixed) grows exponentially with the dimension d. Moreover, like the MC method, the number of integration points required to achieve a reasonable accuracy also increases exponentially with the dimension d (i.e., the CoD phenomenon), which makes the method computationally infeasible for very high dimensional integration problems.

Recent advances in quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) methods have substantially extended their applicability and efficiency in high-dimensional numerical integration. In the past few years, researchers have developed various forms of randomized QMC (RQMC), adaptive transformation, and hybridization techniques that integrate ideas from importance sampling, stochastic optimization, and even machine learning-inspired transport mappings. For instance, Guth and Kaarnioja [17] applied QMC techniques to partial differential equations with generalized Gaussian input uncertainty, demonstrating that properly designed low-discrepancy sampling can substantially reduce variance in high-dimensional PDE solvers. Wang and Wang [18] analyzed the convergence rate of QMC with importance sampling in reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces (RKHS), providing new theoretical insights for unbounded functions. Melnikov and Milz [19] explored RQMC in the context of risk-averse stochastic optimization, confirming its superior performance in variance reduction and robustness. In financial modeling, Hok and Kucherenko [20] demonstrated the “unreasonable effectiveness” of RQMC for option pricing and risk analysis, achieving remarkable accuracy improvements over traditional Monte Carlo approaches. Furthermore, Imai, Kuo, and Owen [21] proposed a dimension-reduction-enhanced RQMC method that significantly reduces the effective dimension in high-dimensional integrals. Collectively, these recent studies highlight a clear trend toward the hybridization of adaptive transformations, dimension reduction, and randomized QMC techniques, which resonates with the motivation and design philosophy of the present work. Nevertheless, despite these promising developments, most existing QMC variants still face intrinsic challenges when tackling extremely high-dimensional problems—particularly those with dimensions exceeding one hundred—where convergence rates deteriorate rapidly and computational costs remain prohibitive.

To overcome the limitations of QMC lattice rules, we first propose an improved QMC lattice rule based on a change of variables and reformulate it as a tensor product rule in the transformed coordinates. We then develop an efficient implementation algorithm, called MDI-LR, by adapting the multilevel dimension iteration (MDI) idea first proposed by the authors in [22], for the improved QMC lattice rule. The proposed MDI-LR algorithm optimizes the function evaluations at integration points by clustering them and sharing computations via a symbolic-function based dimension/coordinate iteration procedure. This MDI-LR algorithm significantly reduces the computational complexity of the QMC lattice rule from an exponential growth in dimension d to a polynomial order , where N denotes the number of integration points in each (transformed) coordinate direction. Thus, the MDI-LR effectively overcomes the CoD and revitalizes QMC lattice rules for high dimensional integration.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we first briefly review the rank-one lattice rule and its properties. In Section 4, we introduce a reformulation of this lattice rule and proposed a tensor product generalization based on an affine transformation. In Section 3, we introduce our MDI-LR algorithm for efficiently implementing the proposed lattice rule based on a multilevel dimension iteration idea. In Section 5, we present extensive numerical experiments to test the performance of the proposed MDI-LR algorithm and compare its performance with the original lattice rule and the improved lattice rule with standard implementation. The numerical experiments show that the MDI-LR algorithm is much faster and more efficient in medium and high dimensional cases. In Section 6, we numerically examine the impact of parameters appeared in MDI-LR algorithm, including the choice of the generating vector for the lattice rule. In Section 7, we present a detail numerical study of the computational complexity for the MDI-LR algorithm. This is achieved by using regression techniques to discover the relationship between CPU time and dimension d. Finally, the paper is concluded with a summary given in Section 8.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we first briefly recall some basic materials about Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) lattice rules for evaluating integrals (1) and their properties. They will set stage for us to introduce our fast implementation algorithm in the later sections.

2.1. Quasi-Monte Carlo Lattice Rules

Lattice rules are a class of quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) methods which were first introduced by Korobov in [12] to approximate (1) with periodic integrand f. A lattice rule is an equal-weight cubature rule whose cubature points are those points of an integration lattice that lie in the half-open unit cube . Every lattice point set includes the origin. The projection of the lattice points onto each coordinate axis are equally spaced. Essentially, the integral is approximated in each coordinate direction by a rectangle rule (or a trapezoidal rule if the integrand is periodic). The simplest lattice rules are called rank-one lattice rules. They use a lattice point set generated by multiples of a single generator vector, which are defined as follows.

Definition 1

(rank-one lattice rule). An n-point rank-one lattice rule in d-dimensions, also known as the method of good lattice points, is a QMC method with cubature points

where , known as the generating vector, is a d-dimensional integer vector having no factor in common with n, and the braces operator takes the fractional part of the input vector.

Every lattice rule can be written as a multiple sum involving one or more generating vectors. The minimal number of generating vectors required to generate a lattice rule is known as the rank of the rule. Besides rank-one lattice rules which have only one generating vector, there are also lattice rules having rank up to d. f is said to have an absolutely convergent Fourier series expansion if the following is true:

where the Fourier coefficient is defined as follows:

The following theorem gives two characterizations for the error of the lattice rules (cf. [13] (Theorem 1) and [10] (Theorem 5.2).

Theorem 1.

Let denote a lattice rule (not necessarily rank-one) and let denote the associated integration lattice. If f has an absolutely convergent Fourier series (5), then the following is true:

where is the dual lattice associated with .

Theorem 2.

Let denote a rank-one lattice rule with a generating vector . If f has an absolutely convergent Fourier series (5), then the following is true:

It follows from (7) that the least upper bound of the error for the class of functions whose Fourier coefficients satisfy is given by the following:

where , , and denotes the absolute value of the i-th component of .

Let

For fixed n and , a good lattice point is so chosen to make as small as possible. It ws proved by Niederreiter in [23,24] (Theorem 2.11) that for a prime n (or a prime power) there exists a lattice point such that the following is true:

This was achieved by proving that has the following expansion:

where

As expected, the performance of a lattice rule depends heavily on the choice of the generating vector . For large n and d, an exhaustive search to find such a generating vector by minimizing some desired error criterion is practically impossible. Below we list a few common strategies for constructing lattice generating vectors.

2.2. Examples of Good Rank-One Lattice Rules

The first example is the Fibonacci lattice, we refer the reader to [10] for the details.

Example 1

(Fibonacci lattice). Let and , where and are consecutive Fibonacci numbers. Then the resulting two-dimensional lattice set generated by is called a Fibonacci lattice.

Fibonacci lattices in 2-d have a certain optimality property, but there is no obvious generalization to higher dimensions that retains the optimality property (cf. [10]).

The second example is so-called Korobov lattices, we refer the reader to [25,26] for the details.

Example 2

(Korobov lattice). Let a be an integer satisfying . Supposed a and n are relatively prime (i.e., their greatest common factor (GCF) is 1) and

Then, the resulting d-dimensional lattice set generated by is called a Korobov lattice.

It is easy to see that there are (at most) choices for the Korobov parameter a, which leads to (at most) choices for the generating vector . Thus it is feasible in practice to search through the (at most) choices and take the one that fulfills the desired error criterion such as the one that minimizes , and (11) allows to be computed in operations (cf. [14]).

The last example is called the CBC lattice which is based on the component-by-component construction (cf. [27]).

Example 3

(CBC lattice). Let and suppose that a and n are relatively prime. Let denote a shifted error operator defined in [27]. Then the generating vector of the CBC lattice is defined component-wise as follows:

- (i)

- Set .

- (ii)

- With held fixed, choose from to minimize in 2-d.

- (iii)

- With held fixed, choose from to minimize in 3-d.

- (iv)

- repeat the above process until all are determined.

It is well-known that [27], with general weights, the cost of the CBC algorithm is prohibitively expensive, thus in practice some special structure is always adopted, among them, product weights, order-dependent weights, finite-order weights, and POD (product and order-dependent) weights are commonly used. In each of the d steps of the CBC algorithm, the search space has cardinality . Then the overall search space for the CBC algorithm is reduced to a size of order (cf. [28] (page 11)). Hence, this provides a feasible way of constructing a generating vector .

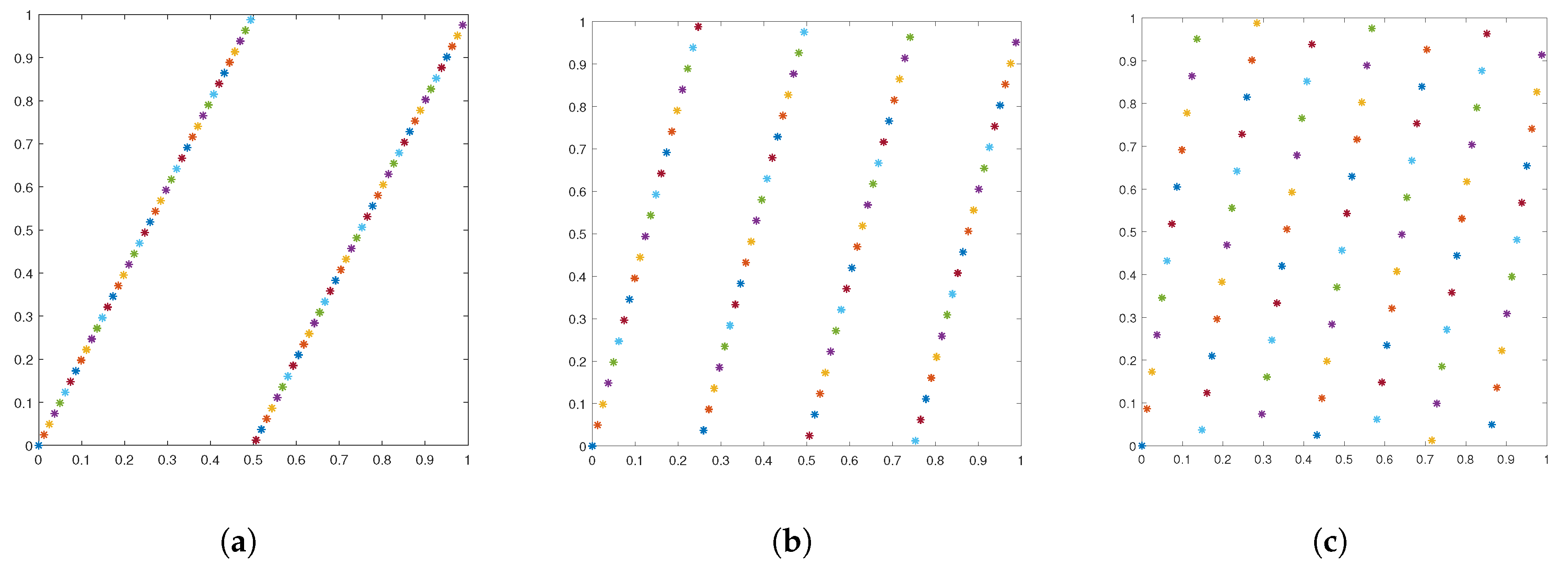

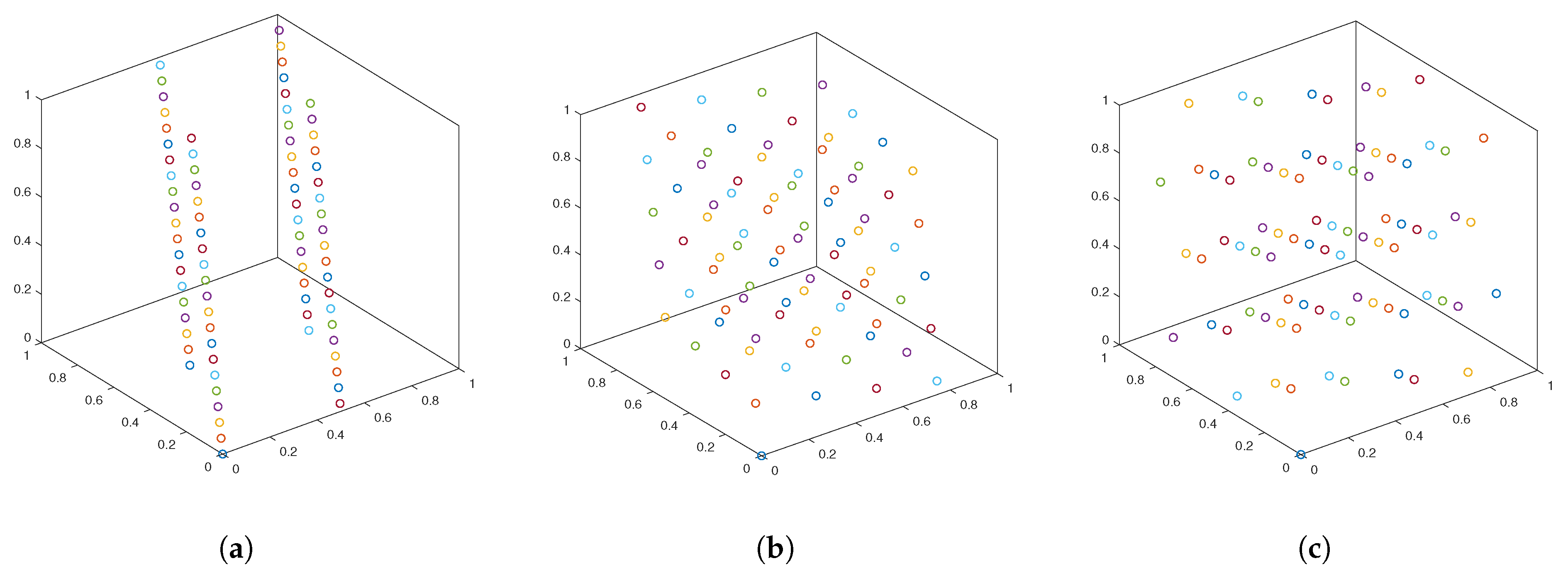

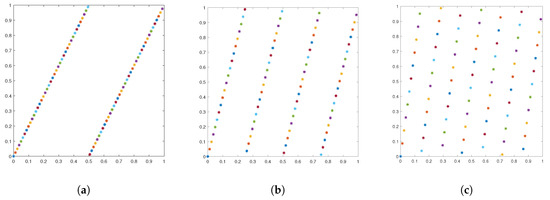

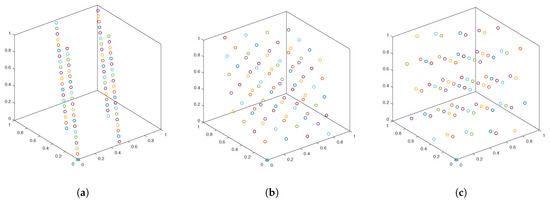

Figure 1 shows a two-dimensional lattice with 81 points, the corresponding generating vectors are (1, 2), (1, 4) and (1, 7) respectively. Figure 2 shows a three-dimensional lattice with 81 points, and the corresponding generating vectors are, respectively, (1, 2, 4), (1, 4, 16), and (1, 7, 49).

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional lattice with 81 points. (a) The corresponding generating vector is . (b) The corresponding generating vector is . (c) The corresponding generating vector is . We observe that the distribution of the 81 lattice points strongly depends on the generating vector. The colors in (a–c) have no particular meaning, they are used to help viewing those points.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional lattice with 81 points. (a) The corresponding generating vector is . (b) The corresponding generating vector is . (c) The corresponding generating vector is . Again, we observe that the distribution of the 81 lattice points strongly depends on the generating vector. The colors in (a–c) have no particular meaning, they are used to help viewing those points.

3. Reformulation of Lattice Rules

Clearly, the lattice point set of each QMC lattice rule has some pattern or structure. Indeed, one main goal of this section is precisely to describe the pattern. We show that a lattice rule almost has a tensor product reformulation viewed in an appropriately transformed coordinate space via an affine transformation. This discovery allows us to introduce a tensor product rule as an improvement to the original QMC lattice rule. More importantly, the reformulation lays an important jump pad for us to develop an efficient and fast implementation algorithm (or solver), called the MDI-LR algorithm, based on the idea of multilevel dimension iteration [22], for evaluating the QMC lattice rule (2).

3.1. Construction of Affine Coordinate Transformations

From Figure 1 and Figure 2, we see that the distribution of lattice points are on lines/planes which are not parallel to the coordinate axes/planes. However, those lines/planes are parallel to each other, this observation suggests that they can be made to parallel to the coordinate axes/planes via affine transformations. Below, we prove that is indeed the case and explicitly construct such an affine transformation for a given QMC lattice rule.

Theorem 3.

Let be the generating vector of a rank-one lattice rule. The j-th lattice point associated with is defined by , where the operator defines as taking the fractional part component-wise. The collection thus forms the n-point set of a rank-one QMC lattice rule in dimension d. Define the following:

Notice that and . Then form a Cartesian grid in the new coordinate system, where denotes the operation of taking the absolute value component-wise in the vector .

Proof.

By the definition of , we have . A direct computation yields the following:

Recall that and denote respectively the fractional and integer parts of the number x. Because

then

and

It is easy to check that the following is true:

On the other hand, let the following be true:

where

and represents the least common multiple.

For any , we have . Since , then . For in the set described by (17), , we obtain the following:

Let ; t follows that there exists an such that resulting in . In the same way, . Therefore, we conclude that , that is, the transformed lattice points have the Cartesian product structure. □

Lemma 1.

Let for denote the Korobov lattice point set, where , and a is an integer parameter that determines the generating vector of the Korobov lattice. Assume that a and n are relatively prime. Define , , which satisfies the conclusion of Theorem 3. Moreover, if , then the number of points in each coordinate direction of the lattice set is the same, that is, , where denotes the number of lattice points along the d-th coordinate direction.

Proof.

From Theorem 3 we have the following:

and

For in the set described by (21), let , it follows that there exists an such that , resulting in . Similarly, . Therefore, we conclude that , Obviously, the transformed lattice points have the Cartesian product structure. Moreover, if , then

Hence . The proof is complete. □

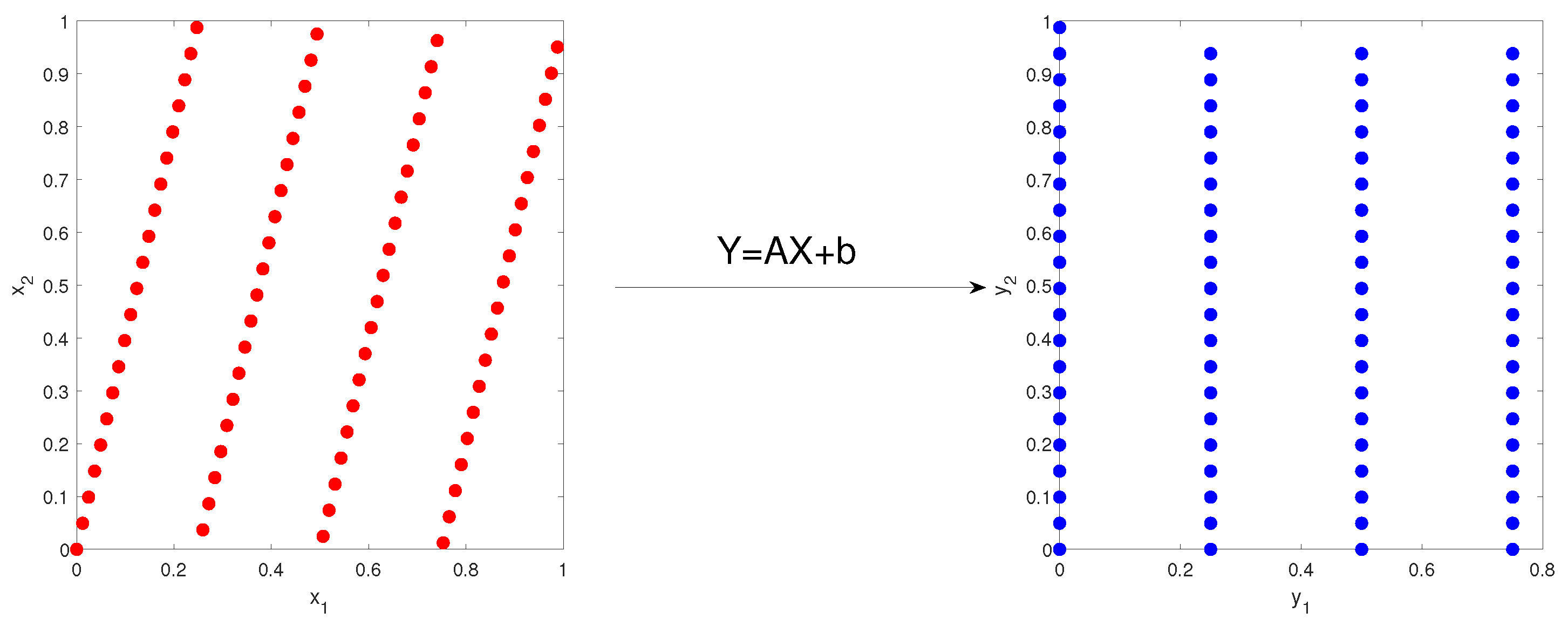

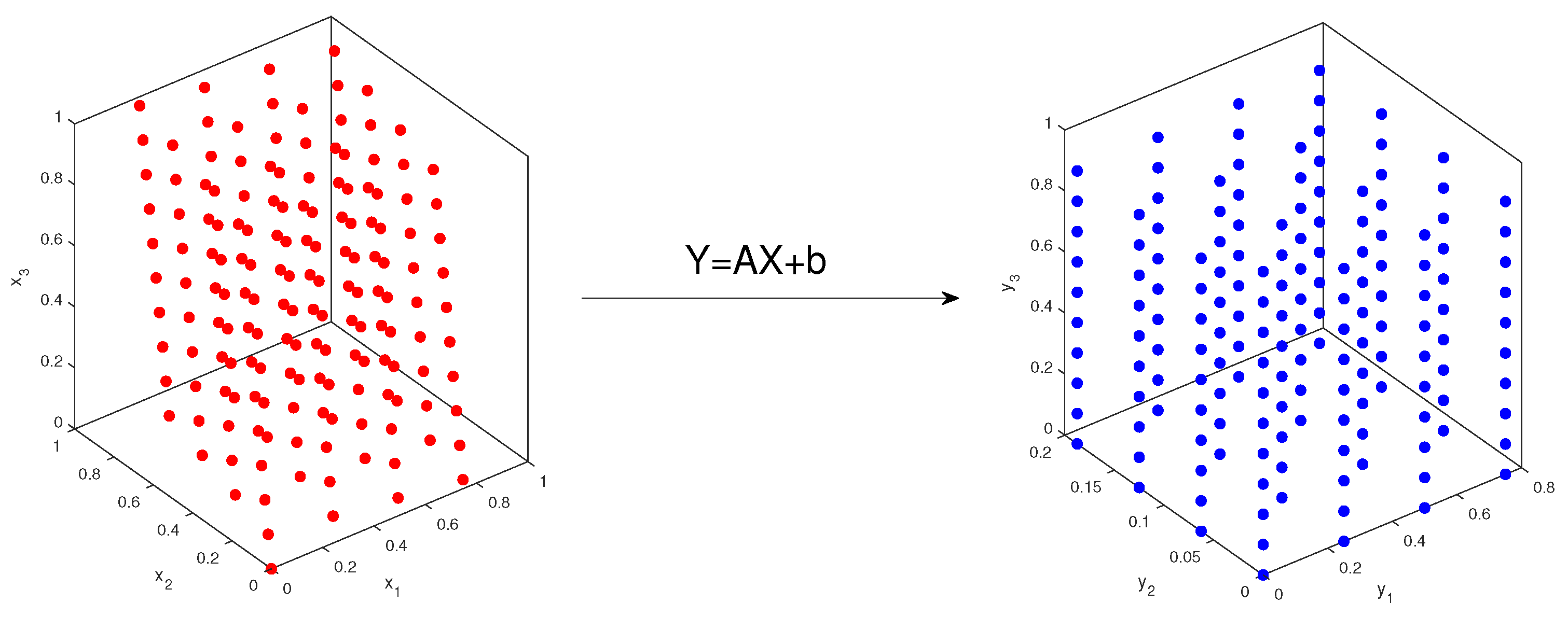

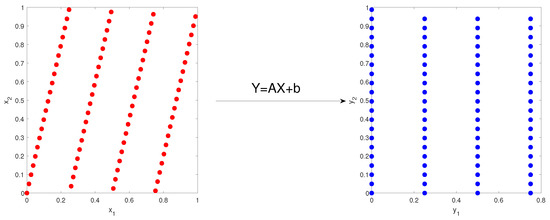

Left graph of Figure 3 shows a 2-d example of 81-point rank-one lattice with the generating vector . Right graph displays transformed lattice under the affine coordinate transformation from to itself, where

Figure 3.

(Left): 81-point lattice with the generating vector . (Right): transformed lattice after affine coordinate transformation.

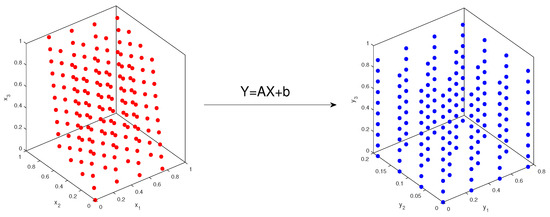

Figure 4 demonstrates a specific example in 3-d. The left graph is a 161-point rank-one lattice with generating vector . The right one shows the transformed points under the affine coordinate transformation from to itself, where the following is true:

Figure 4.

(Left): 161-point rank-one lattice with generating vector is . (Right): transformed lattice after coordinate transformation.

3.2. Improved Lattice Rules

From Figure 3 and Figure 4 we see that the transformed lattice point sets do not exactly form tensor product grids because many lines miss one point. By adding those “missing" points which can be performed systematically, we easily make them become tensor product grids in the transformed coordinate system. Since more integration points are added to the QMC lattice rule, the resulting quadrature rule is expected to be more accurate (which is supported by our numerical tests), hence, it is an improvement to the original QMC lattice rule. We also note that those added points would correspond to ghost points in the original coordinates.

Definition 2

(Improved QMC lattice rule). Let and be a rank-one lattice point set and for some and (which uniquely determine an affine transformation). Suppose there exists points so that together the points form a tensor product grid in the transformed coordinate system, then the QMC lattice rule obtained by using those sampling points is called an improved QMC lattice rule, and denoted by .

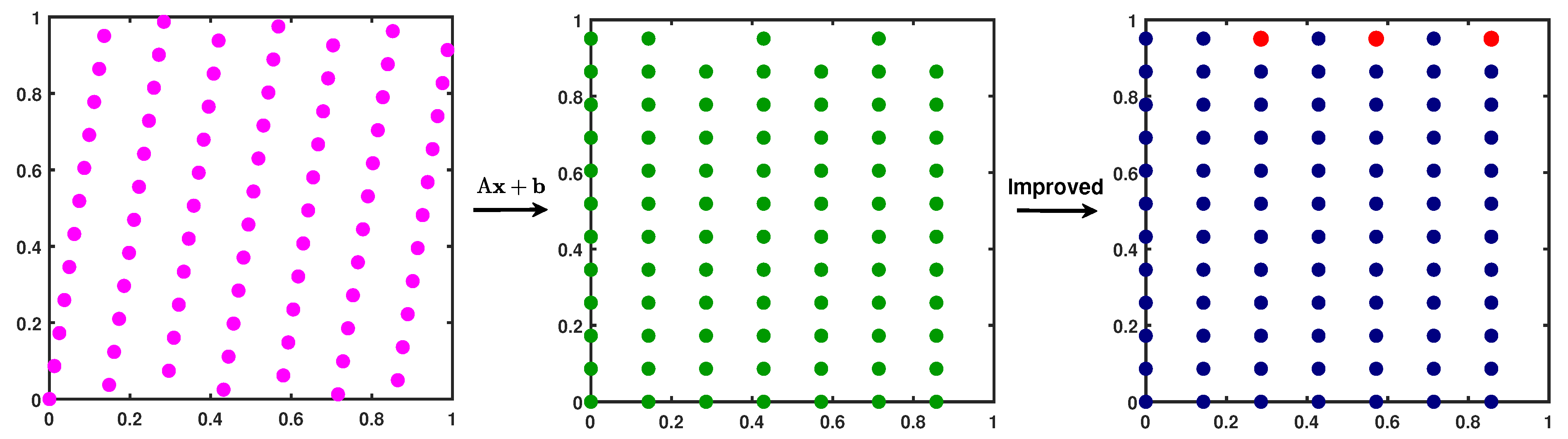

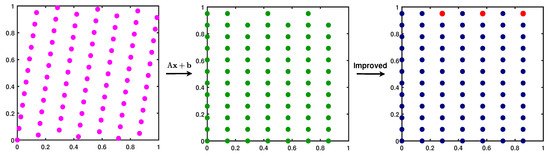

Figure 5 shows a 81-point (i.e., ) 2-d rank-one lattice with the generating vector , the transformed lattice (middle), and the improved tensor product grid (right). Three points (in red color) are added on the top; so, for this example.

Figure 5.

(Left): 81-point lattice with the generating vector . (Middle): transformed lattice. (Right): improved tensor product grid after adding three points (in red color).

4. The MDI-LR Algorithm

Since an improved rank-one lattice is a tensor product grid in the transformed coordinate system and its corresponding quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) rule is a tensor product rule with equal weight, . This tensor product improvement allows us to apply the multilevel dimension iteration (MDI) approach, which was proposed by the authors in [22], for a fast implementation of the original QMC lattice rule, especially in the high dimension case. The resulting algorithm will be called the MDI-LR algorithm throughout this paper,

Formulation of the MDI-LR Algorithm

To formulate our MDI-LR algorithm, we first recall the MDI idea/algorithm in simple terms (cf. [22]). For a tensor product rule, we need to compute a multi-summation with variable limits as follows:

which involves function evaluations for the given function f if one uses the conventional approach by computing function value at each point independently, that inevitably leads to the curse of dimensionality (CoD). To make computation feasible in high dimensions, it is imperative to save the computational cost by evaluating the summation more efficiently.

The main idea of the MDI approach proposed in [22] is to compute those function values in cluster (not independently) and to compute the summation layer-by-layer based on a dimension iteration with help of symbolic computation. To that end, we write the following:

where is fixed and

The MDI approach recursively generates a sequence of symbolic functions ; each function has m fewer arguments than its predecessor (because the dimension is reduced by m at each iteration). As already mentioned above, the MDI approach explores the lattice structure of the tensor product integration point set; instead of evaluating function values at all integration points independently, it evaluates them in cluster and iteratively along m-coordinate directions, and the function evaluation at any integration point is not completed until the last step of the algorithm is executed. In some sense, the implementation strategy of the MDI approach is to trade large space complexity for low time complexity. That being said, however, the price to be paid by the MDI approach for the speedy evaluation of the multi-summation is that those symbolic function needs to be saved during the iteration process, which often takes up more computer memory.

For example, consider 2-d function and let . In the standard approach, to compute the function value at an integration point , one needs to compute three multiplications , and , and two additions. To compute function values, it requires a total of multiplications and additions. On the other hand, the first for-loop of the MDI approach generates which requires N evaluations of (symbolic computations) and N evaluations of , as well as additions. The second for-loop generates which requires N evaluations of and N evaluations of , as well as additions. After the second for-loop completes, we obtain the summation value. The computation complexity of the MDI approach consists of a total of multiplications and additions. Which is much cheaper than the standard approach. In fact, the speedup is even more dramatic in higher dimensions.

It is easy to see that the MDI approach can not be applied to the QMC rule (2) because it is not in a multi-summation form. However, we have showed in Section 3 that this obstacle can be overcome by a simple affine coordinate transformation (i.e., change of variables) and adding a few integration points.

Let denote the affine transformation, then the integral (1) is equivalent to the following:

where stands for the determinant of and

Then, our improved QMC rank-one lattice rule for (2) in the -coordinate system takes the following form:

Let the following be true:

Clearly, it is a multi-summation with variable limits. Thus, we can apply the MDI approach to compute it efficiently. Before doing that, we first need to extend the MDI algorithm, Algorithm 2.3 of [22], to the case of variable limits. We name the extend algorithm as MDI, which is defined in Algorithm 1 below.

where denotes the natural embedding from to by deleting the first m components of vectors in , and the following is true:

| Algorithm 1 MDI(d, g, ) |

Inputs:

Output: .

|

Remark 1.

- (a)

- Algorithm 1 recursively generates a sequence of symbolic functions , each function has m fewer arguments than its predecessor.

- (b)

- Since , when , we simply use the underlying low dimensional QMC quadrature rules. As was performed in [22], we name those low dimensional algorithms as 2d-MDI and 3d-MDI, and introduce the following conventions.

- −

- If , set MDI, which is computed by using the underlying 1-d QMC quadrature rule.

- −

- If , set MDI 2d-MDI.

- −

- If , set MDI 3d-MDI.

We note that when , the parameter m becomes a dummy variable and can be given any value. - (c)

- We also note that the MDI algorithm in [22] has an additional parameter r which selects the 1-d quadrature rule. However, such a choice is not needed here because the underlying QMC rule is used as the 1-d quadrature rule.

We are now ready to define our MDI-LR algorithm, which is denoted by MDI-LR, which is defined in Algorithm 2 below, by using the above MDI algorithm to evaluate in (27).

| Algorithm 2 MDI-LR(f, ) |

Inputs: . Output: . |

Noting that, here, we set , that is, the dimension is reduced by 1 at each dimension iteration; this is because the numerical tests of [22] show that, when , the MDI algorithm is more efficient than when . Also, the upper limit vector depends on the choice of the underlying QMC rule. In Lemma 1 we showed that when and , then , that is, the number of integration points is the same in each (transformed) coordinate direction.

5. Numerical Performance Tests

In this section, we present extensive and purposely designed numerical experiments to gauge the performance of the proposed MDI-LR algorithm and to demonstrate its superiority over the standard implementations of the QMC lattice rule (SLR) and the improved lattice rule (Imp-LR) for computing high dimensional integrals. All our numerical experiments are performed in Matlab on a desktop PC with Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6226R CPU 2.90GHz and 32GB RAM. It should be noted that the MDI-LR algorithm does not require any prior knowledge of the integrand’s smoothness, which makes it applicable to a broad class of problems, including those with limited regularity.

5.1. Two and Three-Dimensional Tests

We first test our MDI-LR on simple 2- and 3-d examples and to compare its performance (in terms of the CPU time) with the SLR and Imp-LR methods.

Test 1. Let and consider the following 2-d integrands:

Table 1 and Table 2 present the computational results (errors and CPU times) of the SLR, Imp-LR and MDI-LR method for approximating and , respectively. Recall that the Imp-LR is obtained by adding some sampling points on the boundary of the integration domain in the transformed coordinates, and the MDI-LR algorithm provides a fast implementation of the Imp-LR using the MDI approach. From Table 1 and Table 2, we observe that in low dimensions (e.g., ), all three methods require very little CPU time, and the SLR method may even be slightly faster than the Imp-LR and MDI-LR methods. Since the Imp-LR and MDI-LR methods use additional sampling points on the boundary, which leads to slightly higher accuracy compared to SLR. Moreover, the MDI-LR method is specifically designed to accelerate the Imp-LR for computing high-dimensional integrals. As the dimension increases, the advantage of the MDI-LR becomes significant: it achieves much higher accuracy while maintaining moderate CPU time, resulting in substantially lower computational complexity and greater efficiency than SLR in high dimensions.

Table 1.

Relative errors and CPU times of SLR, Improved LR and MDI-LR simulations with , , for approximating .

Table 2.

Relative errors and CPU times of SLR, Improved LR and MDI-LR simulations with , , or approximating .

Test 2. Let and we consider the following 3-d integrands:

Table 3 and Table 4 present the simulation results (errors and CPU time) of the SLR, Imp-LR, and MDI-LR methods for computing and in Test 2. We observe that the SLR method requires less CPU time in both simulations. The advantage of the MDI-LR method in accelerating the computation does not materialize in low dimensions as seen in Test 1. Once again, the Imp-LR and MDI-LR have higher accuracy compared to the SLR method because they use additional sampling points on the boundary of the transformed domain.

Table 3.

Relative errors and CPU times of SLR, Improved LR and MDI-LR simulations with , , for computing .

Table 4.

Relative errors and CPU times of SLR, Improved LR and MDI-LR simulations with , , for computing .

5.2. High Dimensional Tests

Since the MDI-LR method is designed for computing high dimensional integrals, its performance for is more important and anticipated, which is indeed the main task of this subsection. First, we test and compare the performance (in terms of CPU time) of the SLR, Imp-LR, and MDI-LR methods for computing high dimensional integrals as the number of lattice points grows due to the dimension increases. Then, we also test the performance of the SLR and MDI-LR methods for computing high dimensional integrals when the number of lattice points increases slowly in the dimension d.

Test 3. Let for and consider the following Gaussian integrand:

where stands for the Euclidean norm of the vector .

Table 5 shows the relative errors and CPU times of SLR, Imp-LR, and MDI-LR methods for approximating the Gaussian integral . The simulation results indicate that SLR and Imp-LR methods are more efficient when , but they struggle to compute integrals when as the number of lattice points increases exponentially in the dimension. However, this is not a problem for the MDI-LR method, which can compute this high dimensional integral easily. Moreover, the MDI-LR method improves the accuracy of the original QMC rule significantly by adding some integration points on the boundary of the transformed domain.

Table 5.

Relative errors and CPU times of SLR, Improved LR and MDI-LR simulations with , , for computing .

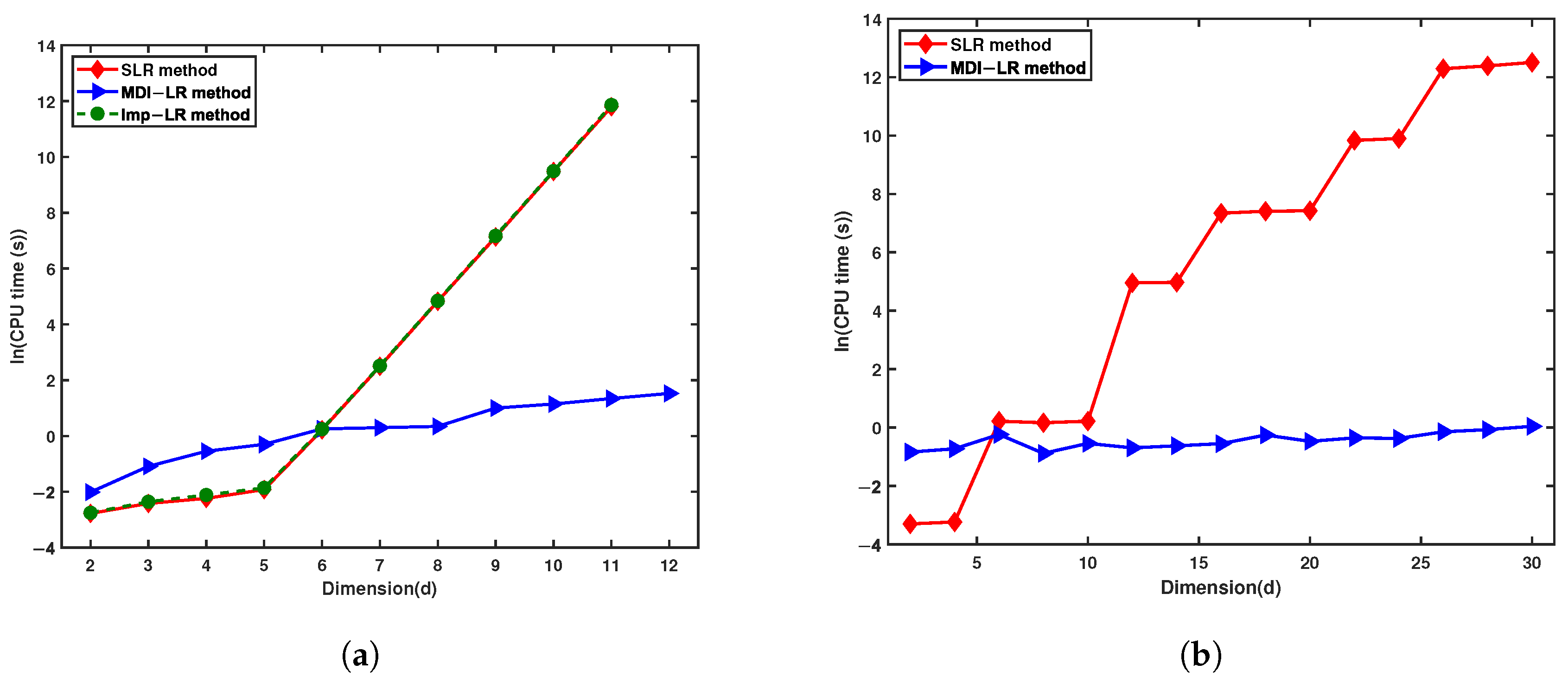

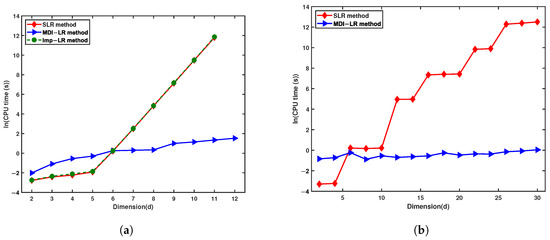

Table 6 shows the relative errors and CPU times of the SLR and MDI-LR methods for computing when the number of lattice points increase slowly in the dimension d. As the dimension increases, the CPU time required by the SLR method also increases sharply (see Figure 6). When approximating the Gaussian integral of about 30 dimensions with lattice points, the SLR method requires 74 h to obtain a result with relatively low accuracy. In contrast, the MDI-LR method only takes about one second to obtain a more accurate value, this demonstrates that the acceleration effect of the MDI-LR method is quite dramatic.

Table 6.

Relative errors and CPU times of SLR and MDI-LR simulations with the same number of integration points for computing .

Figure 6.

CPU time comparison of SLR and MDI-LR simulations: (a) the number of lattice points increases in dimension; (b) the number of lattice points increases slowly.

It is well known that it is difficult to obtain high accuracy approximations in high dimensions because the number of integration points required is enormous. A natural question is whether the MDI-LR method can handle very high (i.e., ) dimensional integration with reasonable accuracy. First, we note that the answer is machine dependent, as expected. Next, we present a test on the computer at our disposal to provide a positive answer to this question

Test 4. Let and consider the following integrands:

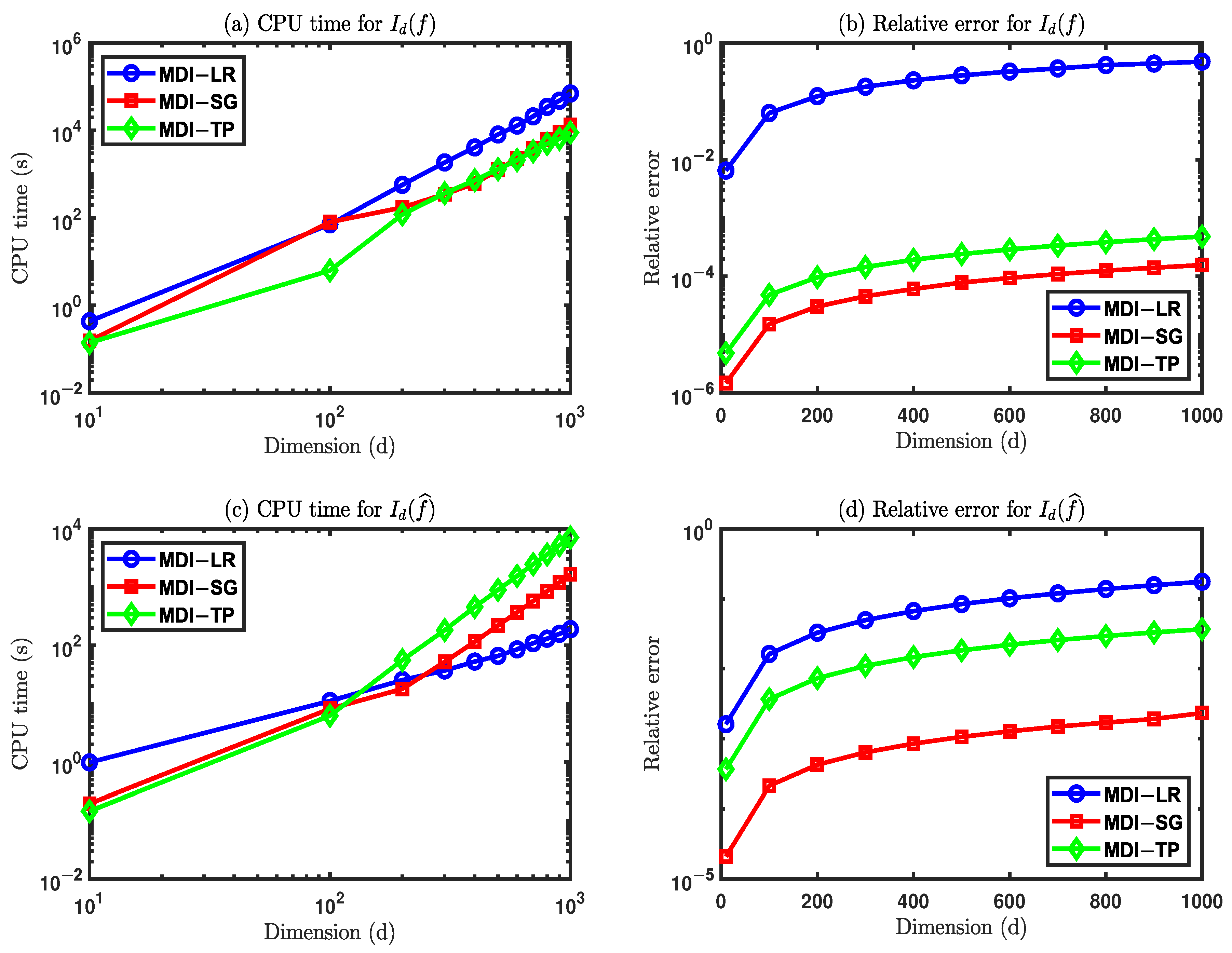

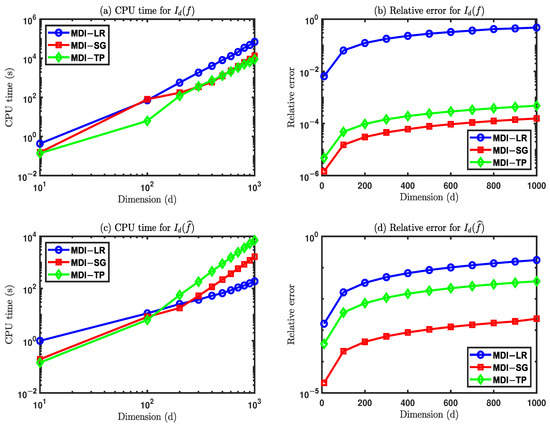

We use the algorithm MDI-LR to compute and with parameters , and an increasing sequence of d. The computed results are presented in Table 7. The simulation is stopped at because it is already in the very high dimension regime. These tests demonstrate the efficacy and potential of the MDI-LR method in efficiently computing high dimensional integrals. However, we note that, in terms of efficiency and accuracy, the MDI-LR method underperforms its two companion methods; namely, the MDI-TP [22] and MDI-SG [29] methods, as shown in Figure 7. The main reason for the underperformance is that the original lattice rule is unable to provide high accuracy integral approximations and the MDI-LR is a fast implementation algorithm (i.e., solver) for the modified lattice rule, Imp-LR. Nevertheless, the lattice rule has its own advantages, such as allowing flexible integration points and giving better results for periodic integrands.

Table 7.

Computed results for and by algorithm MDI-LR.

Figure 7.

Comparison of MDI-LR, MDI-SG, and MDI-TP methods.

6. Influence of Parameters

The original MDI algorithm involves three crucial input parameters: r, m, and N. The parameter r determines the one-dimensional basis value quadrature rule, while m sets the step size in the multidimensional iteration, and N represents the number of integration points in each coordinate direction. The algorithm MDI-LR is similar to the original MDI, but uses the QMC rank-one lattice rule with generating vector , so the parameter r is muted. Here we focus on the Korobov approach in constructing the generating vector , which is defined as . Moreover, the improved tensor product rule (in the transformed coordinate system) that is implemented by the algorithm Imp-LR has variable upper limits in the summation (cf. (27)); hence, N is now replaced by which is determined by the underlying QMC lattice rule. Furthermore, as explained earlier, we set due to our experience in [22]. As a result, the only parameter to select is a. Below, we first test the influence of the Korobov parameter a on the efficiency of the algorithm MDI-LR and then test dependence of its performance on and d.

6.1. Influence of Parameter a

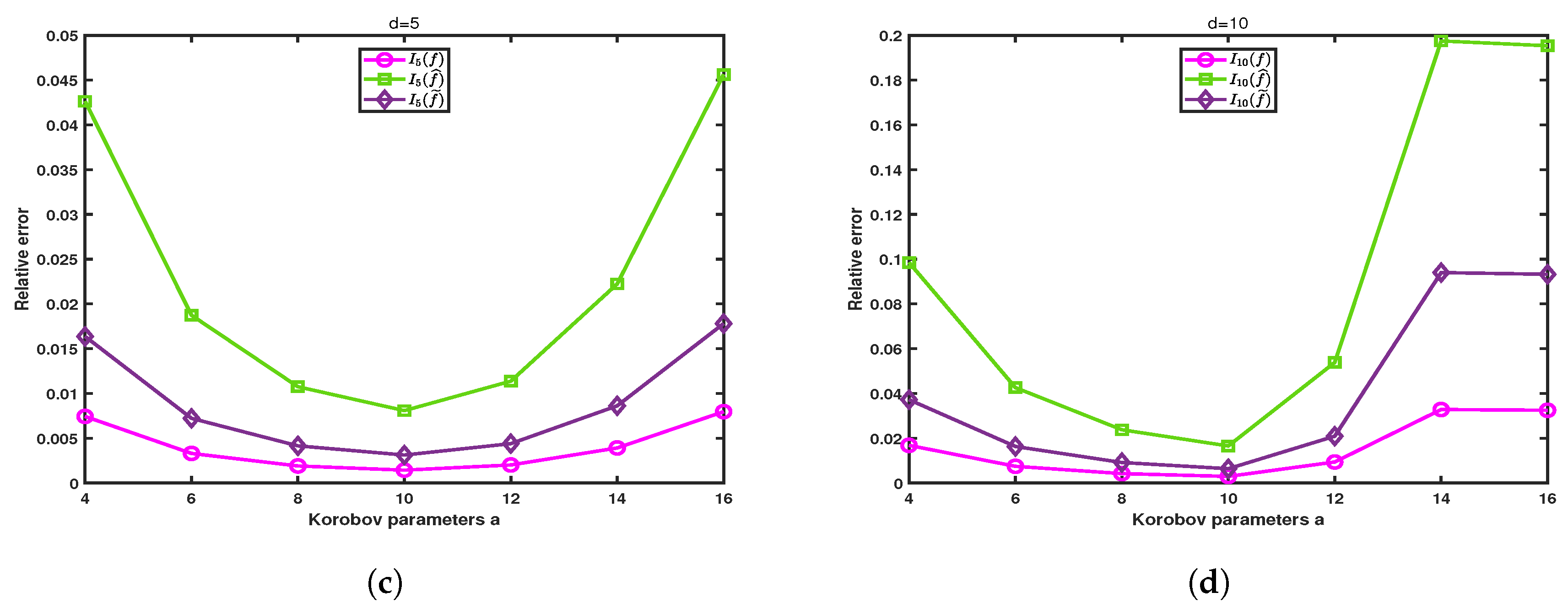

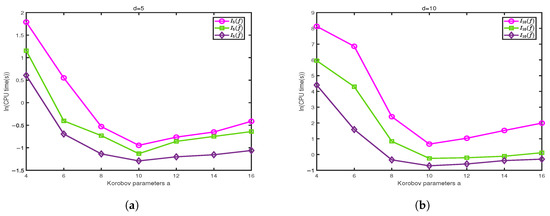

In this subsection, we investigate the impact of the generating vector in the algorithm MDI-LR. We note that similar methods can be constructed using other .

Test 5. Let and consider the following integrands:

We compare the performance of the algorithm MDI-LR with different Korobov parameters a while holding other parameters unchanged when computing , , and .

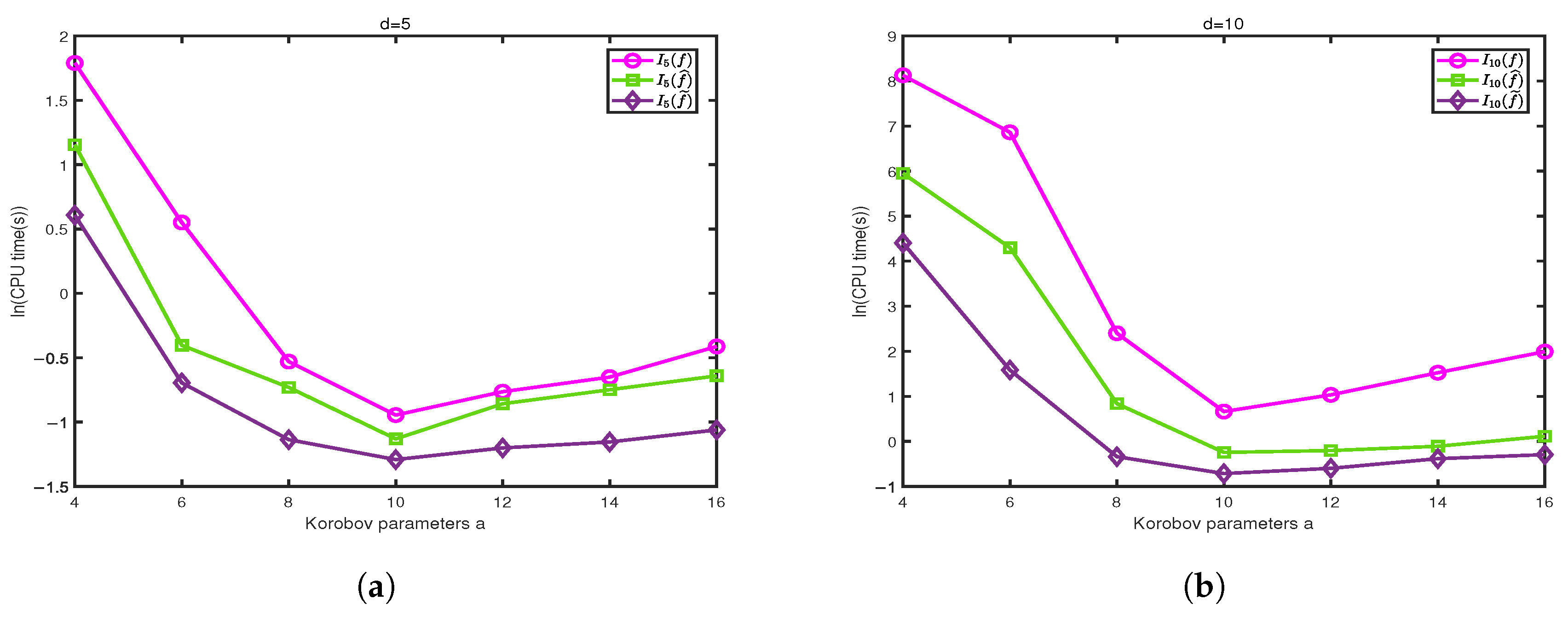

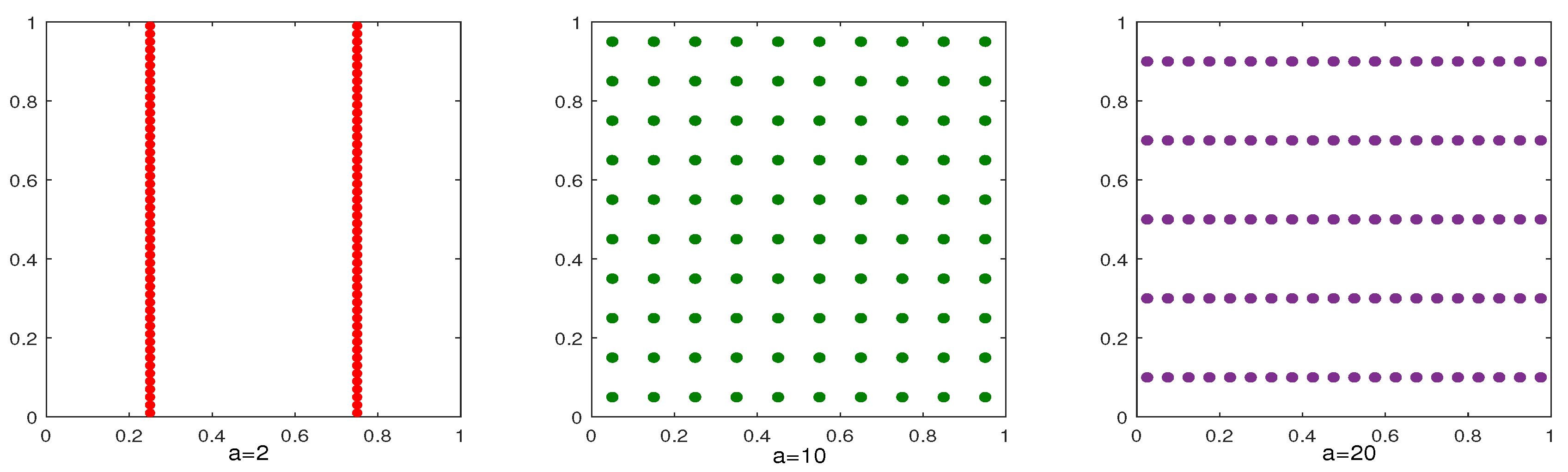

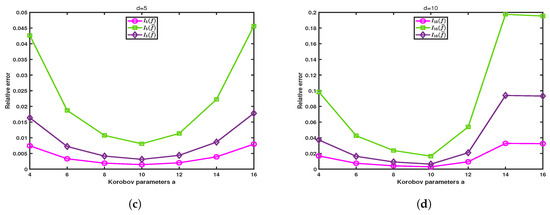

Figure 8 shows the computed results for and , respectively. We observe that the algorithm MDI-LR with different parameters a has different accuracy and the effect could be significant. These results indicate that the algorithm is most efficient when , where and n represents the total number of integral points. This is because when a smaller a is used, although fewer integration points need to be evaluated in each coordinate direction in the first dimension iterations, since the total number of integral points n is the same, the amount of computation will increase dramatically. When using a larger a, more integration points need to be used in each coordinate direction in the first dimension iterations. Only when the integration points are equally distributed to each coordinate direction, the efficiency of the algorithm MDI-LR can be optimized. A total of 100 points are shown in Figure 9. When , only 2 iterations in the -direction are needed, but 50 iterations in the -direction must performed, hence, a total of 52 iterations in the two directions are required. On the other hand, when , a total of 25 iterations in the two directions are required. It is easy to check that the least total of 20 iterations occurs when . The difference in accuracy is obvious, because the different a leads to different generating vector . Which in turn results in different integration points. We note that it was already well studied in the literature on how to choose a to achieve the highest accuracy (cf. [10]).

Figure 8.

Performance comparison of algorithm MDI-LR with and for computing , and . (a) , CPU time comparison. (b) , CPU time comparison. (c) , comparison of relative errors. (d) , comparison of relative errors.

Figure 9.

Distribution of 100 integration points in the transformed coordinate system when respectively.

6.2. Influence of Parameter

In the previous section, we know that the algorithm is most efficient when , where N represents the number of integration points in each direction. This section aims to investigate the impact of N on the MDI-LR algorithm. For this purpose, we conduct tests by setting and and .

Test 6. Let , f, and be the same as in Test 5.

Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 present a performance comparison for algorithm MDI-LR with and , respectively. We note that the quality of the computed results also depend on types of the integrands. As expected, more integration points must be used to achieve a good accuracy for very oscillatory and fast growth integrands.

Table 8.

Performance comparison of algorithm MDI-LR with and , for computing .

Table 9.

Performance comparison of algorithm MDI-LR with and , for computing .

Table 10.

Performance comparison of algorithm MDI-LR with and , for computing .

7. Computational Complexity

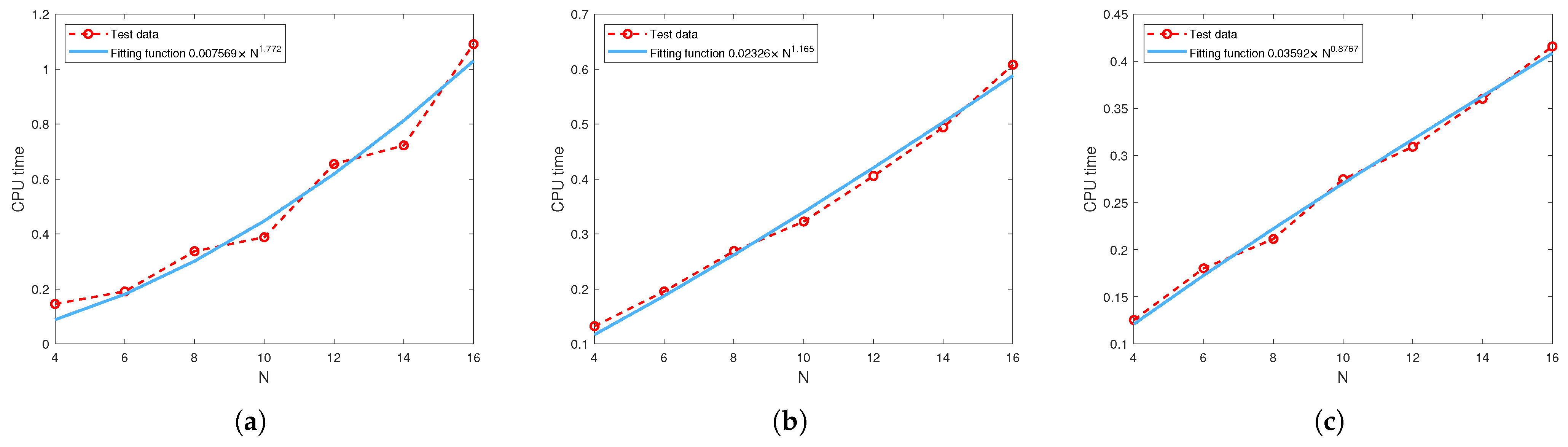

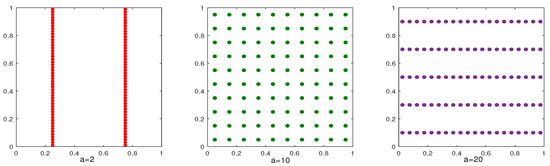

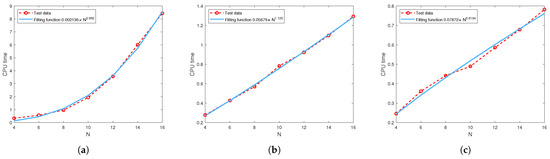

7.1. The Relationship Between the CPU Time and N

In this subsection, we examine the relationship between CPU time and the parameters and using a regression technique based on test data.

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show CPU time as a function of N obtained by the least squares regression with the fitted function given in Table 11. All results show that CPU time grows in proportion to .

Figure 10.

The relationship between the CPU time and parameter N when : (a) (b) (c) .

Figure 11.

The relationship between the CPU time and parameter N when : (a) (b) (c) .

Table 11.

Relationship between the CPU time and parameter N.

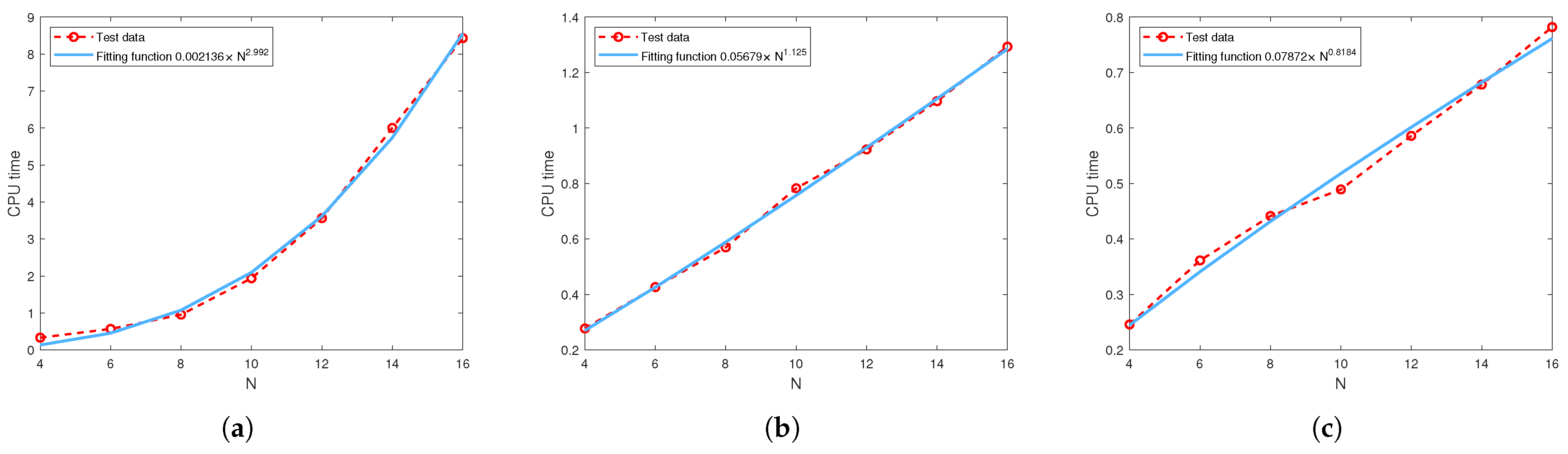

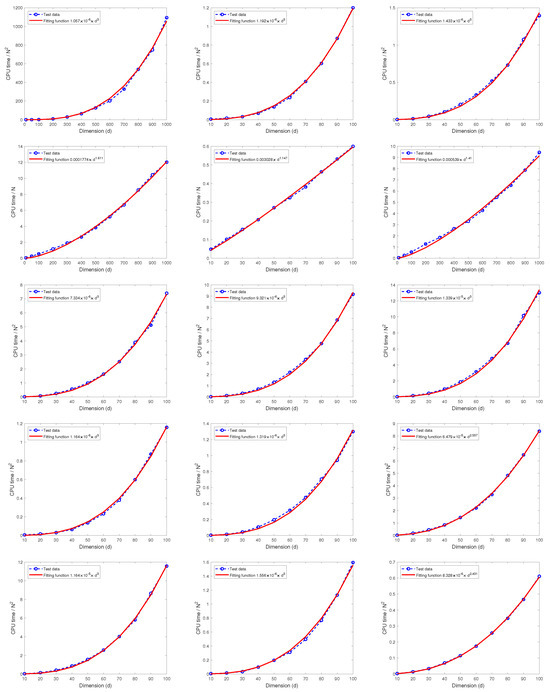

7.2. The Relationship Between the CPU Time and the Dimension d

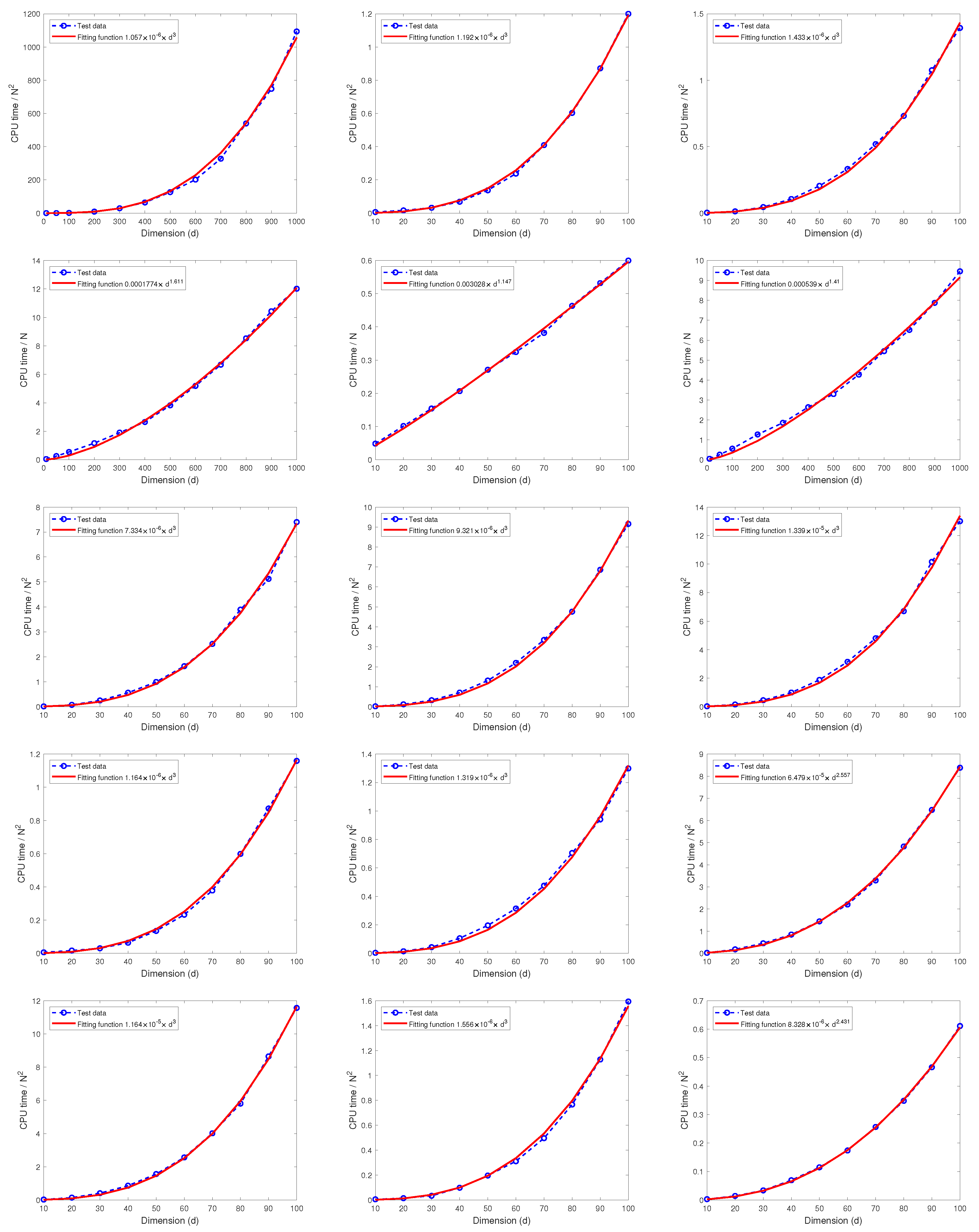

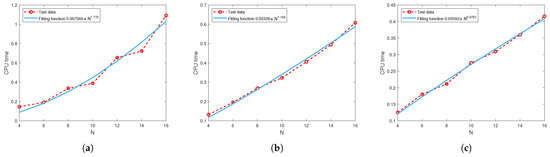

In this subsection, we exploit the computational complexity (in terms of CPU time as a function of d) using the least squares regression on numerical test data.

Test 7. Let , we consider the following five integrands:

Figure 12 displays the the CPU time as functions of d obtained by the least square regression whose analytical expressions are given in Table 12. We note that the parameters of the algorithm MDI-LR only affect the coefficients of the fitted function, not the power of the polynomials. These results show that the CPU time required by the proposed algorithm MDI-LR grows at most with polynomial order .

Figure 12.

The relationship between the CPU time and dimension d.

Table 12.

The relationship between CPU time as a function of the dimension d.

We assess the quality of the fitted curves using the R-square criterion in Matlab, defined by R-, where is a test data output, is the predicted value, and is the mean of . As shown in Table 12, the R-square values of all fitted functions are close to 1, indicating their high accuracy. These results support the observation that the CPU time grows no more than cubically with the dimension d. Combined with the results of Test 6 in Section 6.2, we conclude that the computational cost of the proposed MDI-LR algorithm scales at most polynomially in the order of .

8. Conclusions

In this paper, we develop a fast numerical algorithm, termed MDI-LR, for the efficient implementation of quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) lattice rules in computing the d-dimensional integral of a given function. To formulate the algorithm, we first employ an affine transformation to map standard rank-one lattice points into a tensor-product-like lattice and then enhance computational reuse and scalability through a multilevel dimension iteration (MDI) approach. This design eliminates the need for explicitly storing integration points or independently evaluating function values, thereby improving both efficiency and scalability.

The main innovations of the proposed method are fourfold. First, the affine-transformed lattice enhances the uniformity of integration point distribution, particularly near domain boundaries. Second, the transformation allows us systematically to add a small number of supplementary points near the boundary of the integration domain to obtain a perfect tensor-product lattice in the new coordinate system. The tensor-product lattice gives a better coverage of the integration domain and results in a slightly higher accurate quadrature rule than the original QMC lattice rule with almost same number of integration points. Third, the transformed QMC lattice (i.e., the tensor-product lattice) can be seamlessly embedded into the Multidimensional Integration (MDI) acceleration framework, which substantially improves computational efficiency while maintaining the numerical accuracy of the quadrature rule. Finally, the proposed MDI-LR algorithm demonstrates excellent scalability and robustness in very high-dimensional problems (up to thousands of dimensions), surpassing direct implementation of QMC methods in both efficiency and accuracy.

Extensive numerical experiments confirm that the MDI-LR algorithm achieves a computational complexity of approximately or better, effectively mitigating the curse of dimensionality. These results indicate that the MDI-LR algorithm makes QMC lattice rules not only competitive but also practically applicable to large-scale high-dimensional integration problems. Future work will focus on extending the proposed framework to general Monte Carlo methods and applying it to high-dimensional partial differential equations and real-world computational models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F.; methodology, H.Z. and X.F.; code and simulation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—revision and editing, X.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work of X.F. was partially supported by the NSF grant: DMS-2309626.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bungartz, H.-J.; Griebel, M. Sparse grids. Acta Numer. 2014, 13, 147–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, T.; Griebel, M. Numerical integration using sparse grids. Numer. Algorithms 1998, 18, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caflisch, R.E. Monte Carlo and quasi-Monte Carlo methods. Acta Numer. 1998, 7, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y. A Monte Carlo method for high dimensional integration. Numer. Math. 1989, 55, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratley, P.; Fox, B.; Niederreiter, H. Implementation and Tests of Low Discrepancy Sequences. ACM Trans. Model. Comput. Simul. 1992, 2, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederreiter, H. Low-discrepancy and low-dispersion sequences. J. Number Theory 1988, 30, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, H. Good permutations for extreme discrepancy. J. Number Theory 1992, 42, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, I. Uniformly distributed sequences with an additional uniform property. USSR Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 1977, 16, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.Y.; Schwab, C.; Sloan, I.H. Quasi-Monte Carlo methods for high-dimensional integration: The standard (weighted Hilbert space) setting and beyond. ANZIAM J. 2011, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.; Kuo, F.Y.; Sloan, I.H. High-dimensional integration: The quasi-Monte Carlo way. Acta Numer. 2013, 22, 133–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederreiter, H. Random Number Generation and Quasi-Monte Carlo Methods; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobov, N.M. The approximate computation of multiple integrals. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1959, 124, 1207–1210. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, I.H.; Joe, S. Lattice Methods for Multiple Integration; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sloan, I.H.; Dick, J. On Korobov lattice rules in weighted spaces. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2004, 42, 1760–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krommer, A.R.; Ueberhuber, C.W. Computational Integration; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S. Experiments on optimal coefficients. In Applications of Number Theory to Numerical Analysis; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, P.A.; Kaarnioja, V. Quasi-Monte Carlo for partial differential equations with generalized Gaussian input uncertainty. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2025, 63, 1666–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X. On the convergence rate of Quasi Monte Carlo method with importance sampling for unbounded functions in RKHS. Appl. Math. Lett. 2025, 160, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, O.; Milz, J. Randomized quasi-Monte Carlo methods for risk-averse stochastic optimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2025, 206, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hok, J.; Kucherenko, S. The unreasonable effectiveness of Randomized Quasi-Monte Carlo in option pricing and risk analysis. Available at SSRN. 2025. Available online: https://www.broda.co.uk/Slides/Risk_RQMC_PCA_Presentation.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Imai, J.; Tan, K.S. Dimension reduction for Quasi-Monte Carlo methods via quadratic regression. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 227, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhong, H. A fast multilevel dimension iteration algorithm for high dimensional numerical integration. Ann. Math. Sci. Appl. 2023, 83, 427–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederreiter, H. Existence of good lattice points in the sense of Hlawka. Monatsh. Math. 1978, 86, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederreiter, H. Quasi-Monte Carlo methods and pseudo-random numbers. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1978, 84, 957–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederreiter, H.; Winterhof, A. Applied Number Theory; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobov, N.M. Properties and calculation of optimal coefficients. Dokl. Akad. Nauk 1960, 132, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, I.H.; Reztsov, A. Component-by-component construction of good lattice rules. Math. Comput. 2002, 71, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzer, P.; Niederreiter, H.; Pillichshammer, F. Ian Sloan and Lattice Rules. In Contemporary Computational Mathematics—A Celebration of the 80th Birthday of Ian Sloan; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 741–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Feng, X. An efficient and fast sparse grid algorithm for high dimensional numerical integration. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).