Abstract

We discuss Markov edge processes defined on edges of a directed acyclic graph with the consistency property for a large class of subgraphs of obtained through a mesh dismantling algorithm. The probability distribution of such edge process is a discrete version of consistent polygonal Markov graphs. The class of Markov edge processes is related to the class of Bayesian networks and may be of interest to causal inference and decision theory. On regular -dimensional lattices, consistent Markov edge processes have similar properties to Pickard random fields on , representing a far-reaching extension of the latter class. A particular case of binary consistent edge process on was disclosed by Arak in a private communication. We prove that the symmetric binary Pickard model generates the Arak model on as a contour model.

Keywords:

directed acyclic graph; Markov edge process; clique distribution; consistency criterion; mesh dismantling algorithm; Bayesian network; Pickard random field; regular lattice; Arak model; evolution of particle system; broken line process; contour edge process MSC:

60G60; 60K35; 68R10; 94C15

1. Introduction

A Bayesian network is a probabilistic graphical model that represents a set of variables and their conditional dependencies via a directed acyclic graph [Wikipedia]. Bayesian networks are a fundamental concept in learning and artificial intelligence, see [1,2,3]. Formally, a Bayesian network is a random field indexed by sites of a directed acyclic graph (DAG) whose probability distribution writes as a product of conditional probabilities of given its parent variables , where is the set of parents of v.

A Bayesian network is a special case of Markov random field on a (generally undirected) graph . Markov random fields include nearest-neighbor Gibbs random fields and play an important role in many applied sciences including statistical physics and image analysis [4,5,6,7].

As noted in [8,9,10] and elsewhere, manipulating the marginals (e.g., computing the mean or the covariance function) of a Gibbs random field is generally very hard when V is large. A class of Markov random fields on which avoids this difficulty was proposed by Pickard [10,11] (the main idea of their construction belongs to Verhagen [12], see [11] (p. 718)). Pickard and related unilateral random fields have found useful applications in image analysis, coding, information theory, crystallography and other scientific areas, not least because they allow for efficient simulation procedures [8,9,13,14,15,16].

A Pickard model (rigorously defined in Section 2) is a family of Bayesian networks on rectangular graphs enjoying the important (Kolmogorov) consistency property: for any rectangles we have that

where is the distribution of and is the restriction of marginal of on . Property (1) implies that the Pickard model extends to a stationary random field on whose marginals coincide with and form Markov chains on each horizontal or vertical line.

Arak et al. [17,18] introduced a class of polygonal Markov graphs and random fields indexed by continuous argument satisfying a similar consistency property: for any bounded convex domains , the restriction of to coincides in distribution with . The above models allow a Gibbs representation but are constructed via equilibrium evolution of a one-dimensional particle system with random piece-wise constant Markov velocities, with birth, death and branching. Particles move independently and interact only at collisions. Similarity between polygonal and Pickard models was noted in [19]. Several papers [20,21,22] used polygonal graphs in landscape modeling and random tesselation problems.

The present paper discusses an extension of polygonal graphs and the Pickard model, satisfying a consistency property similar to (1) but not directly related to lattices or rectangles. The original idea of the construction (communicated to the author by Taivo Arak in 1992) referred to a particle evolution on the three-dimensional lattice . In this paper, the above Arak model is extended to any dimension and discussed in Section 4 in detail. It is a special case of a Markov edge process with probability distribution introduced in Section 3 and defined on edges (arcs) of a directed acyclic graph (DAG) as the product over of the conditional clique probabilities , somewhat similarly to a Bayesian network, albeit the conditional probabilities refer to collection of ‘outgoing’ clique variables and not to a single ‘child’ as in a Bayesian network. Markov random fields indexed by edges discussed in the literature [5,6,7] are usually defined on undirected graphs through Gibbs representation and experience a similar difficulty of computing their marginal distributions as Gibbsian site models. On the other hand, ‘directed’ Markov edge processes might be useful in causal analysis where edges of DAG represent ‘decisions’ and can be interpreted as the (random) ‘cost’ of ‘decision’ .

The main result of this work is Theorem 2, providing sufficient conditions for consistency

of a family of Markov edge processes defined on DAGs, , with the partial order given by The sufficient conditions for (2) are expressed in terms of clique distributions and essentially reduce to the marginal independence of incoming and outgoing clique variables (i.e., collections and ), see (33) and (34).

The class of DAGs satisfying (2) is of special interest. In Theorem 2, is the class of all sub-DAGs obtained from a given DAG by a mesh dismantling algorithm (MDA). The above algorithm starts by erasing any edge that leads to a sink or comes from a source , and proceeds in the same way and in an arbitrary order, see Definition 4. The class contains several interesting classes of ‘one-dimensional’ and ‘multi-dimensional’ sub-DAGs on which the restriction in (2) is identified as a Markov chain or a sequence of independent r.v.s (Corollary 2).

Section 4 discusses consistent Markov edge processes on ‘rectangular’ subgraphs of endowed with nearest-neighbor edges directed in the lexicographic order. We discuss properties of such edge processes and present several examples of ‘generic’ (common) clique distributions, with particular attention paid to the binary case (referred to as the Arak model). In dimension we provide a detailed description of the Arak model in terms of a particle system moving along the edges of . Finally, Section 5 establishes a relation between the Pickard and Arak models, the latter model identified in Theorem 3 as a contour model of the former model under an additional symmetry assumption.

We expect that the present work can be extended in several directions. Similarly to [8,9] and some other related studies, the discussion is limited to discrete probability distributions, albeit continuous distributions (e.g., Gaussian edge processes) are of interest. A major challenge is the application of Markov edge processes to causal analysis and Bayesian inference, bearing in mind the extensive research in the case of Bayesian networks [1,2]. Consistent Markov edge processes on regular lattices may be of interest to pattern recognition and information theory. Some open problems are mentioned in Remark 7.

2. Bayesian Networks and Pickard Random Fields

Let be a given DAG. A directed edge from to , is denoted as . With any vertex we can associate three sets of edges

representing the incoming edges, outgoing edges and all edges incident to v. A vertex is called a source or a sink if or , respectively. The partial order (reachability relation) on G means that there is a directed path on this DAG from to . We write if The above partial order carries over to edges of G, namely, Following [2], the set of vertices is called the parents of v, whereas is called the family of v.

Definition 1.

Let be a given DAG. We call family distribution at any discrete probability distribution , that is, a sequence of positive numbers summing up to 1:

The set of all family distributions at is denoted by .

For , the conditional probability of given parent configuration writes as

with if and if .

Definition 2.

Let be a set of family distributions on DAG . We call a Bayesian network on G corresponding to a random process indexed by vertices (sites) of G and such that for any configuration

We remark that the terminology ‘family distribution’ is not commonplace, whereas the definition of Bayesian network varies in the literature [1,2,23], being equivalent to (5) under the positivity condition In the simplest case of chain graph , (Example 2 below), a Bayesian network is a Markov chain with transition probabilities ; particularly, any non-Markovian site process on the above G is not a Bayesian network. In the general case , the conditional (family) distributions in (5) are most intuitive and often used instead of . A Bayesian network satisfies several Markov conditions [2], particularly, the ordered Markov condition:

The Markov properties of site models on directed (not necessary acyclic) graphs are discussed in Lauritzen et al. [24] and other works.

In the rest of this subsection, is a directed subgraph of the infinite DAG with lexicographic partial order

and edge set

The class of ‘rectangular’ subDAGs with

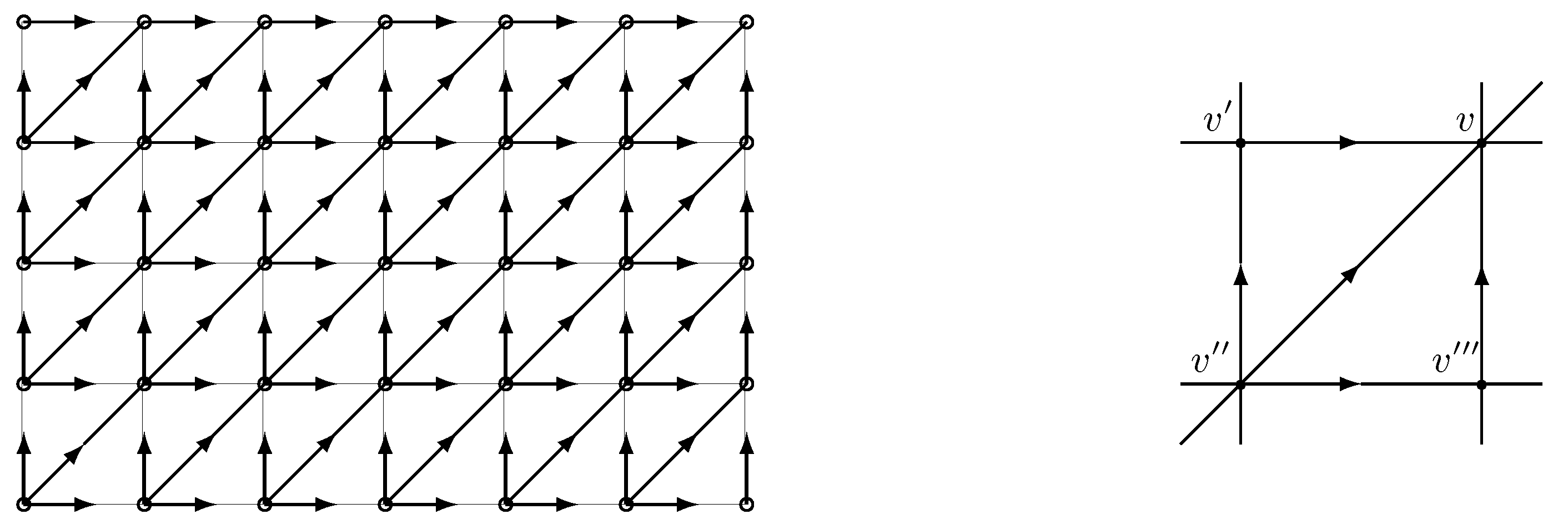

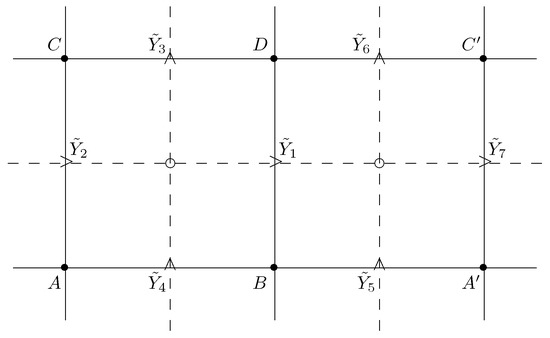

will be denoted . Given two ‘rectangular’ DAGs , we write if . For the generic family in Figure 1, right, the family distribution is is indexed by the elements of the table

and written as the joint distribution of four r.v.s with , . The marginal distributions of these r.v.s are designated by the corresponding subsets of the table (8), e.g., is the distribution of r.v. A. The conditional distributions of these r.v.s are denoted as in (4); viz., is the conditional distribution of B given a value of A.

Figure 1.

Left: Rectangular DAG in (7); right: generic family .

Definition 3.

We call a Pickard model a Bayesian network on DAG with family distribution independent of and satisfying the following conditions:

(stationarity) and

(conditional independence).

In a Pickard model, the family of consists of four points, see Figure 1, except when v belongs to the left lower boundary of rectangle V in (7) and ; for it consists of the single point . Accordingly, the family distributions are marginals of the generic distribution in Definition 3. We note that Pickard model (also called Pickard random field) is defined in [8,9,10,16] in somewhat different ways, which are equivalent to Definition 3. Let be the class of all rectangles V in (7).

Theorem 1

Remark 1.

The consistency property in (11) implies that for in (7), and any , the restriction of a Pickard model on the horizontal interval is a Markov chain

with initial distribution and transition probabilities . Indeed, is the set of vertices of , and the corresponding ‘one-dimensional’ Pickard model on is defined by (12). In a similar way, the restriction of a Pickard model on a vertical interval is a Markov chain

with initial distribution and transition probabilities .

Remark 2.

In the binary case or , the distribution ϕ is completely determined by probabilities

In terms of (14), conditions (9) and (10) translate to

see [10] (p. 666). The special cases , and correspond to a degenerated Pickard model, the latter two implying and , respectively, and leading to a random field which takes constant values on each horizontal (or vertical) line in . Hence, a binary Pickard model can be parametrized by seven parameters,

as in the non-degenerated case can be found from :

The parameters in (16) satisfy natural constraints resulting from their definition as probabilities, particularly, .

3. Markov Edge Process: General Properties and Consistency

It is convenient to allow G to have isolated vertices, which of course can be removed w.l.g., our interest primarily being focused on edges. The directed line graph of DAG is defined as the graph whose set of vertices is is the same as that of an undirected line graph, and the set of (directed) edges is

Note that is acyclic, and hence a DAG.

Given a DAG , we denote as the class of all non-empty sub-DAGs (subgraphs) with .

Definition 4.

A transformation is said to be a top mesh dismantling algorithm (top MDA) if it erases an edge leading to a sink ; in other words, if with

Similarly, a transformation is said to be a bottom mesh dismantling algorithm (bottom MDA) if it erases an edge starting from a source , in other words, if with

We denote as and the classes of DAGs containing G and the subDAGs which can be obtained from G by succesively applying a top MDA, bottom MDA, or both types of MDA in an arbitrary order:

Note that the above transformations may lead to a subDAG containing isolated vertices which can be removed from w.l.g. Figure 2 illustrates that in general.

Figure 2.

SubDAG (right) cannot be obtained from DAG G (left) by MDA.

Definition 5.

A subDAG is said to be the following:

- (i)

- An interval DAG iffor some ;

- (ii)

- A chain DAG if , for some

- (iii)

- A source-to-sink DAG if any edge connects a source of to a sink of .

The corresponding classes of subDAGs in Definition 5 (i)–(iii) will be denoted by and .

Proposition 1.

For any DAG we have that

Proof.

The proof of each inclusion in (20) proceeds by induction on the number of edges of G. Clearly, the proposition holds for . Assume it holds for ; we will show that it holds for The induction step for the three relation in (20) is proved as follows.

- (i)

- Fix and to be as in (19). Let be the set of sinks of G. If is a sink and (or ), then belongs to by definition of the last class. If is a sink and , we can dismantle an edge , and the remaining graph in (18) has edges and contains , meaning the inductive assumption applies, proving .Next, let . Then there is a path in G from to at least one of these sinks. If , we apply a top MDA to and see that in (18) has the number of edges and contains the interval graph in (19), so that the inductive assumption applies to and consequently to G as well, as before, proving the induction step in case (i).

- (ii)

- Let be a chain between and , since belongs to by definition. Let be the set of sinks of G. If is a sink and then G contains an edge which does not belong to . Then, by removing e from G by top MDA we see that in (18) contains the chain viz., , and therefore by the inductive assumption. If is a sink and , we remove from G any edge leading to and arrive at the same conclusion. If is not a sink, we remove any edge leading to a sink and apply the inductive assumption to the remaining graph having edges. This proves the induction step in case (ii).

- (iii)

- Let , where and are the sets of sources and sinks of , respectively. Let and be the sets of sources and sinks of . If , i.e., G is a source-to-sink DAG, we can remove from it an edge and the remaining graph in (18) contains and satisfies the inductive assumption. If G is not a source-to-sink DAG, it contains a sink or a source In the first case, there is , which can be removed from G, and the remaining graph contains and satisfies the inductive assumption. The second case follows from the first one by DAG reversion. This proves the induction step in case (iii), hence the proposition.

□

An edge process on DAG is a family of discrete r.v.s indexed by edges of G. It is identified with a (discrete) probability distribution

Definition 6.

Let be a given DAG. A clique distribution at is any discrete probability distribution , that is, a family of positive numbers summing up to 1:

The set of all clique distributions at is denoted by .

Given , the conditional probabilities of out-configuration given in-configuration write as

with and for for .

Definition 7.

A Markov edge process on a DAG corresponding to a given family of clique distributions is a random process indexed by edges of G and such that for any configuration

An edge process on a DAG can be viewed as a site process on the line graph of , with

Corollary 1.

A Markov edge process in (21) is a Bayesian network on the line DAG if

Condition (22) can be rephrased as the statement that ’outgoing’ variables are conditionally independent given ‘ingoing’ variables for each node . Analogously, in (21) is a Bayesian network on the reversed line graph under a symmetric condition that ‘ingoing’ variables are conditionally independent given ‘outgoing’ variables , for each node .

Definition 8.

Let be a DAG and be a family of subDAGs of G. A family of edge processes is said consistent if

Given edge process in (21), we define its restriction on a subDAG as

In general, is not a Markov edge process on , as shown in the following example.

Example 1.

Let Then and

The subDAG is composed of two edges going from different sources 1 and 2 to the same sink 3. By definition, a Markov edge process on corresponds to independent , viz.,

It is easy to see that the two probabilities in (25) and (26) are generally different (however, they are equal if is a product distribution and , in which case and

In Example 1, the restriction to is a Markov edge process with . The following proposition shows that a similar fact holds in a general case for subgraphs obtained from G by applying a top MDA.

Proposition 2.

Let be a Markov edge process on DAG . Then for any , the restriction is a Markov edge process on with clique distribution given by

which is the restriction of clique distributions to (sub-clique)

Proof.

It suffices to prove the proposition for a one-step top MDA, or in (18). Let , , . From the definitions in (21) and (27),

□

Example 2

(Markov chain). Let be a chain from 0 to n. The classes and consist respectively of all chains from 0 to , from to n and from i to j ( A Markov edge process on the above graph is a Markov chain with the probability distribution

where is a (discrete) univariate and are bivariate probability distributions; are conditional or transitional probabilities. It is clear that the restriction on is a Markov chain with ; in other words, it satisfies Proposition 2 and (27). However, the restriction to or is a Markov chain with the initial distribution

which is generally different from . We conclude that Proposition 2 ((27) in particular) fails for subDAGs of G obtained by a bottom MDA. On the other hand, hold for the above provided the values satisfy the additional compatibility condition:

Proposition 3.

Proof.

Relation (28) follows from

and the definition in (21), since the products cancel in the numerator and the denominator of (30).

Consider (29). We use Propositions 1 and 2, according to which the interval DAGs belong to . The ‘intermediate’ DAG , constructed from by adding the single edge , viz., , also belongs to since it can be attained from by dismantling all edges with the exception of . Note that . Therefore, by Proposition 2, where is a Markov edge process on with clique distributions

The expression in (29) follows from (31) and (28) with E replaced by by noting that is a sink in ; hence, , whereas . □

Remark 3.

Note that in the conditional probability on the r.h.s. of (28) are nearest neighbors of e in the line graph (DAG)

Theorem 2.

Remark 4.

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

- In the binary case (), the value can be interpreted as the presence of a ‘particle’ and as its absence on edge . ‘Particles’ ‘move’ on a DAG in the direction of arrows. ‘Particles’ ‘collide’, ‘annihilate’ or ‘branch’ at nodes , with probabilities determined by clique distribution . See Section 4 for a detailed description of particle evolution for the Arak model on .

Proof of Theorem 2.

It suffices to prove (35) for a one-step MDA:

which remove a single edge coming from a source and a single edge going to a sink , respectively. Moreover, it suffices to consider only. The proof for follows from Proposition 2 and does not require (32)–(34). (It also follows from by DAG reversion.) Then, by the marginal independence of and ,

From the definition of in (27), we have that , and therefore

leading to

and proving (35) for defined above, or the statement of the theorem for a one-step MDA . □

Corollary 2.

Let be a Markov edge process on DAG satisfying the conditions of Theorem 2:

- (i)

- The restriction of on a chain DAG , is a Markov chain, viz.,where

- (ii)

- The restriction of on a source-to-sink DAG is a sequence of independent r.v.s, viz.,where is the set of sources of and is the set of edges coming from a source and ending into a sink of ,

Proof.

- (i)

- (ii)

- By Proposition 1, belongs to so that Theorem 2 applies with in (27) given by

□

Remark 5.

A natural generalization of chain and source-to-sink DAGs is a source–chain–sink DAG with the property that any sink is reachable from a source by a single chain (directed path). We conjecture that for a source–chain–sink DAG , the restriction of in Theorem 2 is a product of independent Markov chains on disjointed directed paths of , in agreement with representations (36) and (37) of Corollary 2.

Gibbsian representation of Markov edge processes. Gibbsian representation is fundamental in the study of Markov random fields [4,6]. Gibbsian representation of Pickard random fields was discussed in [8,9,11,12]. The following Corollary 3 provides Gibbsian representation of the consistent Markov edge process in Theorem 2. Accordingly, the set of vertices of DAG is written as , where the boundary consists of sinks and sources of G and the interior of the remaining sites.

Corollary 3.

Let be a Markov edge process on DAG satisfying the conditions of Theorem 2 and the positivity condition . Then

where the inner and boundary potentials are given by

Formula (38) follows by writing (21) as and rearranging terms in the exponent using (32)–(34). Note (38) is invariant with regard to graph reversal (direction of all edges reversed). Formally, the inner potentials in (39) do not depend on the orientation of G, raising the question of the necessity of conditions (33) and (34) in Theorem 2. An interesting perspective seems to be the study of the Markov evolution of Markov edge processes on DAG with invariant Gibbs distribution in (38).

4. Consistent Markov Edge Process on and Arak Model

Let be an infinite DAG whose vertices are points of regular lattice and whose edges are pairs directed in the lexicographic order if and only if . We write if . A -dimensional hyperplane

can be identified with for any fixed .

Let denote the class of all finite ‘rectangular’ subgraphs of , viz., if for some and We denote

the class of all subgraphs of formed by intersection with a -dimensional hyperplane that can be identified with an element of . Particularly, for and any ,

and the subgraph can be identified with a chain

of length . Similarly, for any ,

and the subgraph of is a planar ‘rectangular’ graph belonging to . Note that any subgraph is an interval subDAG of in the sense of Definition 5 (i). From Proposition 1 we obtain the following corollary.

Corollary 4.

Let . Any subgraph can be obtained by applying an MDA to G.

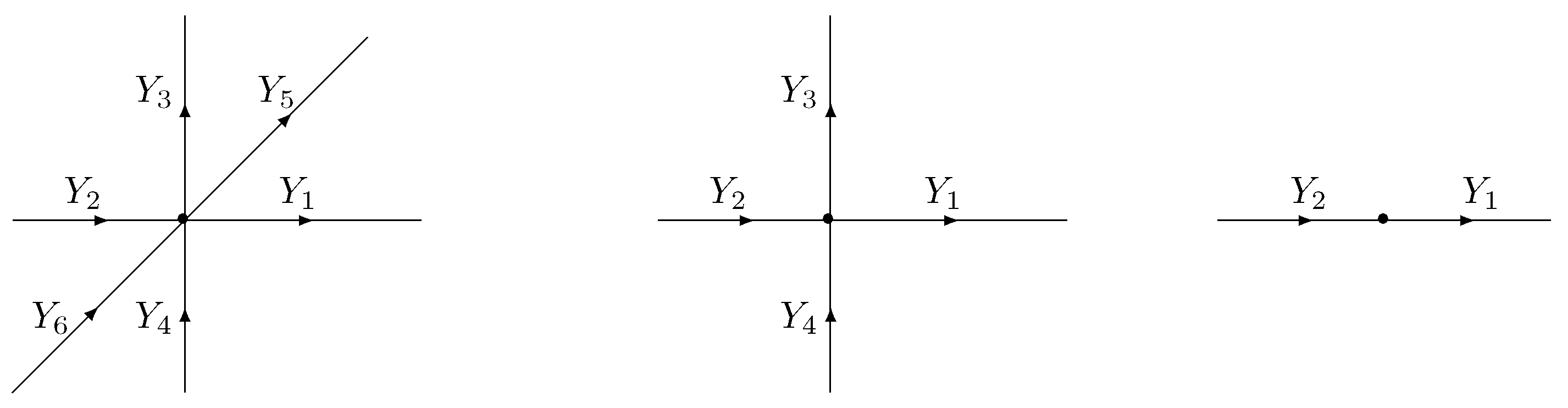

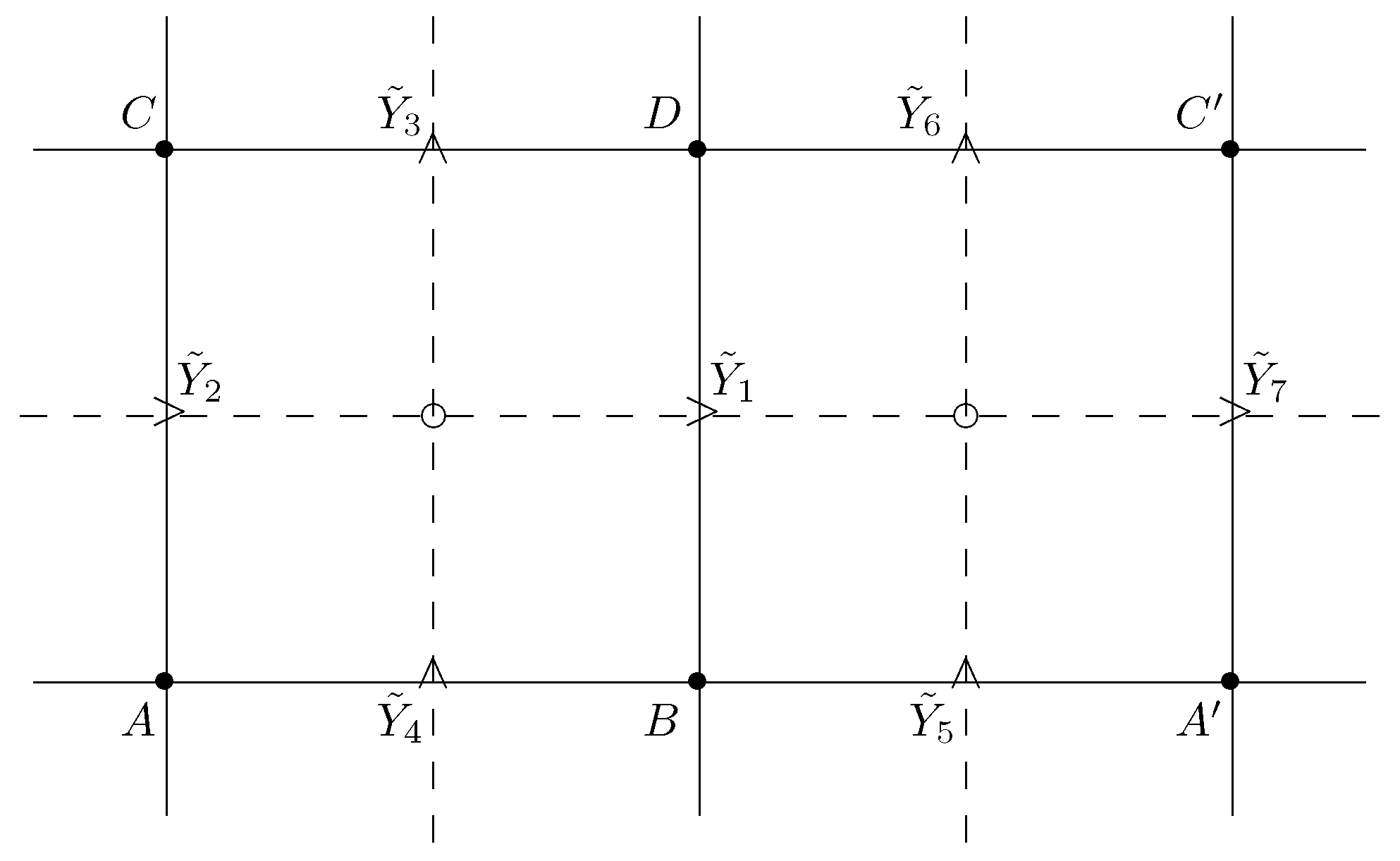

We designate ‘outgoing’ and ‘incoming’ clique variables (see Figure 3). Let be a generic clique distribution of random vector on incident edges of . We use the notation .

Figure 3.

Generic clique variables of Markov edge processes on , .

The compatibility and consistency relations in Theorem 2 write as follows for any

and

Let be the class of all discrete probability distributions on satisfying (45) and (46).

Corollary 5.

Let be a (consistent) Markov edge process on DAG with clique distribution . The restriction

of on any -dimensional hyperplane in (40) is a consistent Markov edge process on DAG with generic clique distribution . Particularly, the restriction

of to a one-dimensional hyperplane in (40) is a reversible Markov chain with the probability distribution

where and are the conditional probabilities.

Example 3.

Broken line process. Let and take integer values and have a joint distribution

, where is a parameter. Note that for

and the last equality is valid for , too. Therefore, π in (50) is a probability distribution on with (marginals) and written as the product of the geometric distribution with parameter . We see that (50) belongs to and satisfies (45) and (46) of Corollary 5. The corresponding edge process called the discrete broken line process was studied by Rollo et al. [25] and Sidoravicius et al. [26] in connection with planar Bernoulli first passage percolation. The discrete broken line process can be described as an evolution of particles moving (horizontally or vertically) with constant velocity until collision with another particle and dying upon collision, with independent immigration of pairs of particles. An interesting and challenging open problem is the extension of the broken line process to higher dimensions, particularly to or .

Definition 9.

We call an Arak model a binary Markov edge process on a DAG with clique distribution .

We also use the same terminology for the restriction of an Arak model on a subDAG , and speak about an Arak model on since extends to infinite DAG ; the extension is a stationary binary random field whose restriction coincides with . Note that when , the clique distribution is determined by probabilities

Particularly, for the compatibility and consistency relations in (45) and (46) read as

The resulting consistent Markov edge process on depends on parameters. In the lattice isotropic case it depends on nine parameters satisfying two consistency equations, and , resulting in a seven-parameter isotropic binary edge process communicated to the author by T. Arak.

Denote unit vectors in , —edges parallel to vectors The following corollary is a consequence of Corollary 5 and the formula for the transition probabilities of a binary Markov chain in Feller [27] (Ch.16.2).

Corollary 6.

The covariance function of an Arak model. Let be an Arak model on DAG . Then for any , ,

where are as in (51).

Remark 6.

In the two-dimensional case , the Arak model on DAG is determined by the clique distribution of in Figure 3, middle, with probabilities satisfying four conditions:

The resulting edge process depends on 11 = (15 − 4) parameters. In the lattice isotropic case, we have five parameters satisfying a single condition and leading to a four-parameter consistent isotropic binary Markov edge process on . Some special cases of parameters in (54) are discussed in Examples 4–6 below.

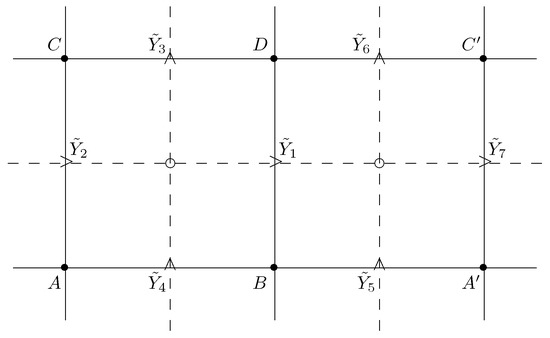

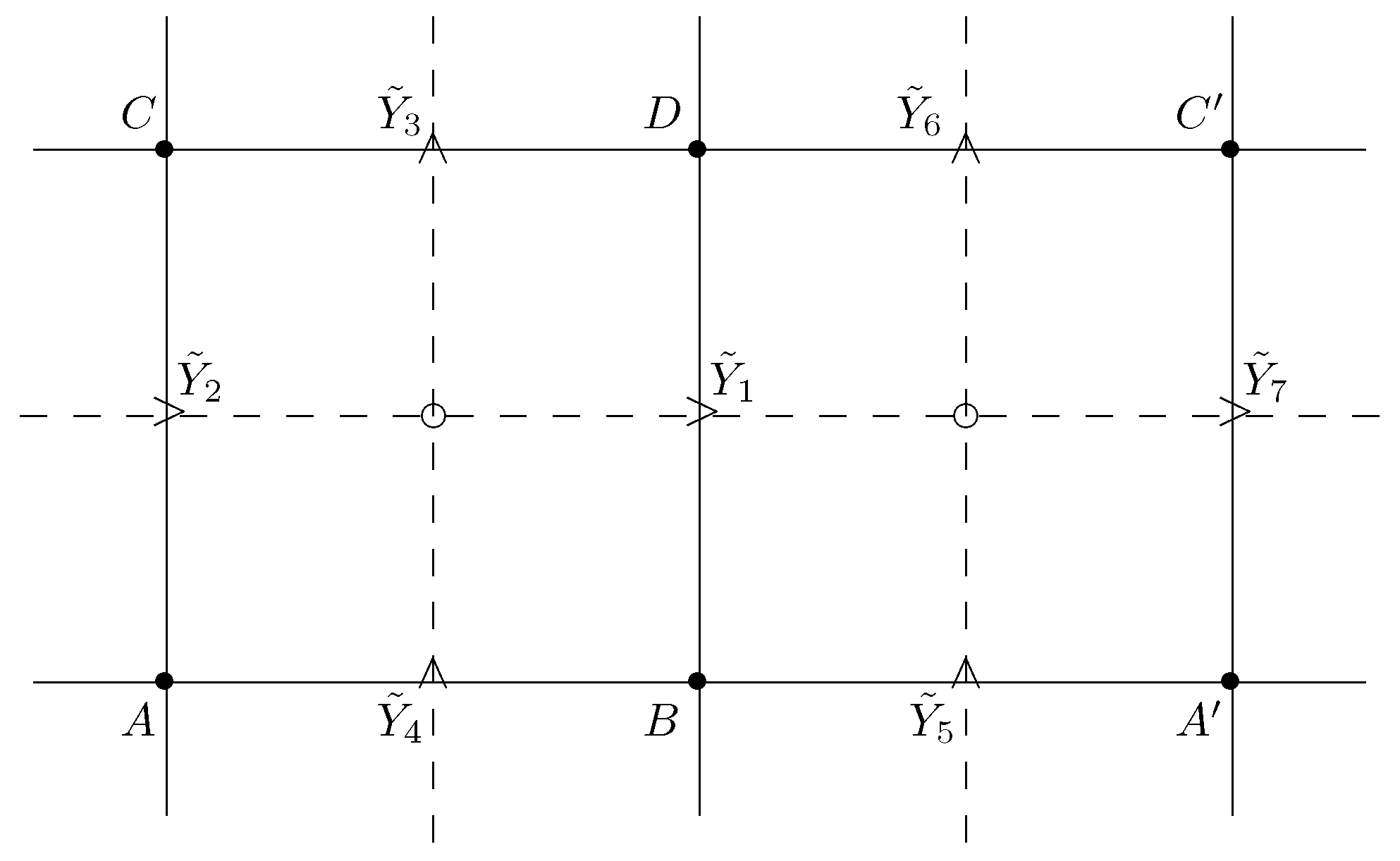

The evolution of the particle system. Below, we describe the binary edge process in Remark 2 on DAG in terms of particle system evolution. The description becomes somewhat simpler by embedding G into , where

where and are boundary sites (sources or sinks belonging of the extended graph ), as shown in Figure 4. The edge process is obtained from as

The presence of a particle on edge (in the sense explained in Section 2) is identified with . A particle moving on a horizontal or vertical edge is termed horizontal or vertical, respectively. The evolution of particles is described by the following rules:

- (p0)

- Particles enter the boundary edges (vertically) and (horizontally) independently of each other with respective probabilities and .

- (p1)

- Particles move along directed edges of independently of each other until collision with another moving particle. A vertical particle entering an empty site will undergoes one of the following transformations.

- (i)

- Leaves v as a vertical particle with probability ;

- (ii)

- Changes the direction at v to horizontal with probability

- (iii)

- Branches at v into two particles moving into different directions, with probability ;

- (iv)

- Dies at v, with probability .

Similarly, a horizontal particle entering an empty site exhibits transformations as in (i)–(iv) with respective probabilities , and . - (p2)

- Two (horizontal and vertical) particles entering , either

- (i)

- both die with probability or

- (ii)

- the horizontal one survives and the vertical one dies with probability . or

- (iii)

- the vertical one survives and the horizontal one dies with probability . or

- (iv)

- both particles survive with probability .

- (p3)

- At an empty site (no particle enters v), one of the following events occurs:

- (i)

- A single horizontal particle is born, with probability

- (ii)

- A single vertical particle is born, with probability

- (iii)

- No particles are born, with probability ;

- (iv)

- Two (horizontal and vertical particles) are born, with probability .

The above list provides a complete description of the particle transformations and transition probabilities of the edge process in terms of parameters

Example 4.

are independent r.v.s, . Accordingly, take independent values on edges of a ’rectangular’ graph , with generally different probabilities and for horizontal and vertical edges. In terms of the particle evolution, this means the ‘outgoing’ particles at each site being independent and independent of the ‘incoming’ ones.

Example 5.

, implying and for any horizontal shift of . The corresponding edge process in this case takes constant values on each horizontal line of the rectangle V. Similarly, case leads to taking constant values on each vertical line of V.

Example 6.

, meaning that none of the four binary edge variables can be different from the remaining three. This implies or

and or

The resulting four-parameter model is determined by . In the isotropic case we have two parameters since This case does not allow for the death, birth or branching of a single particle; particles move independently until collision with another moving particle, upon which both colliding particles die or cross each other with probabilities defined in (p1)–(p3) above.

5. Contour Edge Process Induced by Pickard Model

Consider a binary site model on rectangular graph

Let be the shifted lattice, and be the rectangular graph with For any horizontal or vertical edge we designate

the edge of , which ‘perpendicularly crosses e at the middle’ and is defined formally by

A Boolean function takes two values, 0 or 1. The class of such Boolean functions has elements.

Definition 10.

Let and be two Boolean functions. A contour edge process induced by a binary site model on in (57) and corresponding to is a binary edge process on defined by

Probably the most natural contour process occurs in the case of Boolean functions

visualized by ‘drawing an edge’ across neighboring ‘occupied’ and ‘empty’ sites in the site process. The introduced ‘edges’ form ‘contours’ between connected components of the random set . Contour edge processes are usually defined for site models on undirected lattices and are well-known in statistical physics [28] (e.g., the Ising model), where they represent boundaries between ‘spins’ and are very helpful in rigorous study of phase transitions. In our paper, a contour process is viewed as a bridge between binary site and edge processes on DAG in (57), particularly, between Pickard and Arak models. Even in this special case, our results are limited to the Boolean functions in (60), raising many open questions for future work. Some of these questions are mentioned at the end of the paper.

Theorem 3.

Proof.

Necessity. Let in (59) and (60) agree with the Arak model. Accordingly, the generic clique distribution is determined by a generic family distribution as

see Figure 3. From (15), we find that

The two first equations in (54) are satisfied by (64). Let us show that (64) implies the last two equations in (54), viz., Using (10), (64) and the same notation as in (17), we see that is equivalent to the equation

which factorizes as Hence, , since and are excluded by the non-degeneracy of .

Let us show the necessity of the two other conditions in (61). Let be a rectangle as in Figure 4 and be the corresponding edge process, where are as in (63) and

The last fact implies that and are conditionally independent given . Particularly,

and

From and (15) we find that

and

Hence, (65) for leads to , or

Next, consider (66). We have

Hence, (66) for writes as yielding and

Equations (67) and (68) prove (61).

and

From and (15) we find that

and

Hence, (65) for leads to , or

Next, consider (66). We have

Hence, (66) for writes as yielding and

Equations (67) and (68) prove (61).

Figure 4.

Contour edge variables in Theorem 3.

Figure 4.

Contour edge variables in Theorem 3.

Finally, let us show that (61) implies symmetry of family distribution and Pickard model . Indeed, is equivalent to the equality of moment functions:

The relation implies the coincidence of moment functions up to order 2: so that (69) reduces to

The relation follows from (15), whereas the remaining three relations in (70) use (15) and (61).

It remains to show the symmetry of Pickard model . Write for configuration of the transformed Pickard model . Then by the definition of Bayesian network in (5),

where provided have the symmetry property. The latter property is valid for our family distribution , implying and ending the proof of the necessity part of Theorem 3.

Sufficiency. As shown above, the symmetry implies (61) and (54) for the distribution of the quadruple in (63). We need to show that in (59) and (60) is a Markov edge process with clique distribution following Definition 7.

Let be the left bottom point of V in (57) and

be the set of all configurations of the contour model. It is clear that any uniquely determines in (72) up to the symmetry transformation: there exist two and only two configurations, , satisfying (72). Then, by the definition of the Pickard model and the symmetry of ,

where

for and having a four-point family as in Figure 1, right. From the definitions in (63), we see that

This and (74) yield

where are out-edges and in-edges of . An analogous relation to (75) holds for , whereas for we have , cancelling with factor 2 on the r.h.s. of (73). The above argument leads to the desired expression

of the contour model as the Arak model with clique distribution given by the distribution of in (63).

Remark 7.

- (i)

- The Boolean functions in (60) are invariant under symmetry . This fact seems to be related to the symmetry of the Pickard model in Theorem 3. It is of interest to extend Theorem 3 to non-symmetric Boolean functions, in an attempt to completely clarify the relation between the Pickard and Arak models in dimension 2.

- (ii)

- A contour model in dimension is usually formed by drawing a -dimensional plaquette perpendicularly to the edge between neighboring sites of a site model X in [28,29]. It is possible that a natural extension of the Pickard model in higher dimensions is a plaquette model (i.e., a random field indexed by plaquettes rather than sites in ), which satisfies a similar consistency property as in (11) and is related to the Arak model in . Plaquette models may be a useful and realistic alternative to site models in crystallography [30].

6. Conclusions

We introduce and systematically explore a new class of processes—consistent Markov edge processes defined on directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). The work generalizes and combines previously known models such as Picard’s Markov random fields and Arak’s probabilistic graph models, offering a unified approach to their study. Main Theorem 2, which establishes sufficient consistency conditions for a family of subgraphs obtained using the MDA algorithm, is a key contribution and opens the way to applications in causal inference and decision theory.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions. This work was inspired by collaboration and personal communication with Taivo Arak (1946–2007). I also thank Mindaugas Bloznelis for his interest and encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Neapolitan, R.E. Learning Bayesian Networks; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.J.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Besag, J. Spatial interaction and the statistical analysis of lattice systems (with Discussion). J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1974, 36, 192–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmet, G. Probability on Graphs, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kindermann, R.; Snell, J.L. Markov Random Fields and Their Applications; Contemporary Mathematics, v.1; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen, S. Graphical Models; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Champagnat, F.; Idier, J.; Goussard, Y. Stationary Markov random fields on a finite rectangular lattice. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1998, 44, 2901–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutsias, J. Mutually compatible Gibbs random fields. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1989, 35, 1233–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, D.K. Unilateral Markov fields. Adv. Appl. Probab. 1980, 12, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, D.K. A curious binary lattice process. J. Appl. Probab. 1977, 14, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, A.M.V. A three parameter isotropic distribution of atoms and the hard-core square lattice gas. J. Chem. Phys. 1977, 67, 5060–5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Talukder, A.; Cressie, N. Texture analysis using partially ordered Markov models. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Image Processing, ICIP-94, Austin, TX, USA, 13–16 November 1994; IEEE Computer Society Press: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 402–406. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, A.J.; Kay, J.W.; Titterington, D.M. An empirical study of the simulation of various models used for images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1994, 16, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchhammer, S.; Justesen, J. Block Pickard models for two-dimensional constraints. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2009, 55, 4626–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Justesen, J. Fields from Markov chains. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2005, 51, 4358–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arak, T.; Clifford, P.; Surgailis, D. Point-based polygonal models for random graphs. Adv. Appl. Prob. 1993, 25, 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arak, T.; Surgailis, D. Markov fields with polygonal realizations. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 1989, 80, 543–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surgailis, D. The thermodynamic limit of polygonal models. Acta Appl. Math. 1991, 22, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J. How many T-tessellations on k lines? Existence of associated Gibbs measures on bounded convex domains. Random Struct. Algorithms 2015, 47, 561–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiêu, K.; Adamczyk-Chauvat, K.; Monod, H.; Stoica, R. A completely random T-tessellation model and Gibbsian extensions. Spat. Stat. 2013, 6, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thäle, C. Arak-Clifford-Surgailis tesselations. Basic properties and variance of the total edge length. J. Stat. Phys. 2011, 144, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Gal, I. Bayesian networks. In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Quality and Reliability; Ruggeri, F., Faltin, F., Kenett, R., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen, S.; Dawid, A.P.; Larsen, B.; Leimer, H. Independence properties of directed Markov fields. Networks 1990, 20, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollo, L.T.; Sidoravicius, V.; Surgailis, D.; Vares, M.E. The discrete and continuum broken line process. Markov Process. Relat. Fields 2010, 16, 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sidoravicius, V.; Surgailis, D.; Vares, M.E. Poisson broken lines’ process and its application to Bernoulli first passage percolation. Acta Appl. Math. 1999, 58, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1950; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sinai, Y.G. Theory of Phase Transitions: Rigorous Results; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmet, G. The Random Cluster Model; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Enting, I.G. Crystal growth models and Ising models: Disorder points. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1977, 10, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).