4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the superiority of the proposed framework in airport surface surveillance systems, we utilized the Airport Surface Surveillance (ASS) dataset, which is publicly accessible at

https://zenodo.org/records/10969885 (accessed on 1 September 2025), for experimental validation. This dataset consists of 2000 typical surveillance images, annotated with common targets such as airplanes, persons, and trucks, among which small targets account for 39.42%. Constructed to enhance the detection performance of small targets in airport surface surveillance systems, this dataset provides a solid experimental foundation for assessing the proposed framework.

Regarding object size distribution, the ASS dataset contains objects with varying scales. Small objects, defined as those with an area less than 32 × 32 pixels (following the COCO dataset convention), account for 39.42% of all annotated instances. Medium objects (32 × 32 to 96 × 96 pixels) comprise approximately 45%, while large objects (greater than 96 × 96 pixels) make up the remaining 15.58%. The minimum detectable object size in our experiments is approximately 16 × 16 pixels, though detection accuracy decreases significantly for objects smaller than 24 × 24 pixels. Objects smaller than this threshold, such as small animals (e.g., dogs or birds), may not be reliably detected and are not included as target categories in this study, as the primary focus is on aviation-related objects including aircraft, persons, and ground support vehicles. Future work could explore the extension of our framework to detect smaller objects or additional categories relevant to airport safety.

Mean Average Precision (mAP) is a commonly used evaluation metric in object detection tasks, measuring the average detection accuracy of a model across different categories. Specifically, mAP@0.5 represents the mean Average Precision when the Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold is set at 0.5, and it is calculated as follows:

Here, denotes the area under the Precision–Recall curve for the i-th category, and n represents the total number of categories. This metric provides a comprehensive reflection of the model’s detection performance across different categories and is one of the key indicators for assessing the accuracy of object detection models.

To more comprehensively evaluate the detection performance of the model, mAP@0.5:0.95 is widely adopted. This metric calculates the mean Average Precision for IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 (with a step size of 0.05) and is calculated as follows:

Here, represents the average precision of the i-th category at an IoU threshold of j. mAP@0.5:0.95 provides a more comprehensive reflection of the model’s detection performance across different IoU thresholds and is an important indicator for assessing the robustness of object detection models.

Precision is one of the key evaluation metrics in object detection tasks, measuring the proportion of correctly detected objects among all detected objects, and it is calculated as follows:

Here, denotes the number of correctly detected objects, and represents the number of incorrectly detected objects. Precision reflects the accuracy of the model in the detection process and is one of the key indicators for assessing model performance.

Recall is another important evaluation metric in object detection tasks, measuring the proportion of correctly detected objects among all actual objects, and it is calculated as follows:

Here, represents the number of objects that were not detected. Recall reflects the completeness of the model in the detection process and is one of the key indicators for assessing model performance.

4.2. Experiment Setup

The experiments were conducted on a high-performance computing platform equipped with the Linux operating system (Ubuntu 20.04), six NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 graphics processing units (GPUs) with 24 GB memory each, and 64 gigabytes of system RAM. The deep learning framework employed was PyTorch 1.12, complemented by the Python 3.9 programming language and the CUDA 11.3 parallel computing platform.

All models, including our proposed architecture and baseline models (YOLO11x, YOLOv10x, YOLOv9e, YOLOv8x, and YOLOv6x), were trained from scratch without leveraging pre-trained weights to ensure fair comparison and rigorous assessment of learning capabilities. The training protocol consisted of 100 epochs with the following hyperparameters:

Optimizer: Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with momentum = 0.937 and weight decay = 5 × 10−4.

Learning rate: Initial learning rate of 0.01 with cosine annealing schedule, decaying to 0.0001 at the final epoch following: .

Batch size: 66 (11 images per GPU across 6 GPUs).

Input resolution: 640 × 640 pixels with multi-scale training (±10% scaling).

Loss weights: , , for box regression, classification, and distribution focal loss, respectively.

To enhance model robustness and prevent overfitting, we applied augmentation strategies during training as follows:

Mosaic augmentation (probability = 0.5): combines four training images into one.

Random horizontal flip (probability = 0.5).

HSV color jittering: Hue (±0.015), Saturation (±0.7), and Value (±0.4).

Random scaling (range: 0.5–1.5).

Translation (±20% of image size).

Rotation (±10 degrees).

No augmentation was applied during validation and testing to ensure objective evaluation.

To ensure fair comparison, all baseline YOLO models (

Table 2) were retrained on the ASS dataset under identical conditions:

Same training/validation split (80%/20%, stratified by class distribution).

Same hyperparameters (optimizer, learning rate schedule, batch size, and epochs).

Same data augmentation pipeline.

Same hardware configuration (6× RTX 4090 GPUs).

We did not use publicly available pre-trained weights for baseline models because (1) pre-trained weights are typically trained on the COCO dataset, which has different object distributions and scales compared to airport surveillance scenarios; (2) training from scratch provides a more rigorous assessment of each architecture’s learning capacity on our specific task. This training-from-scratch approach ensures that performance differences in

Table 2 reflect genuine architectural advantages rather than transfer learning benefits.

The training time for our proposed model was approximately 18 h on the 6-GPU configuration, while inference speed averaged 45 FPS at 640 × 640 resolution on a single RTX 4090 GPU.

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Training Curve Analysis

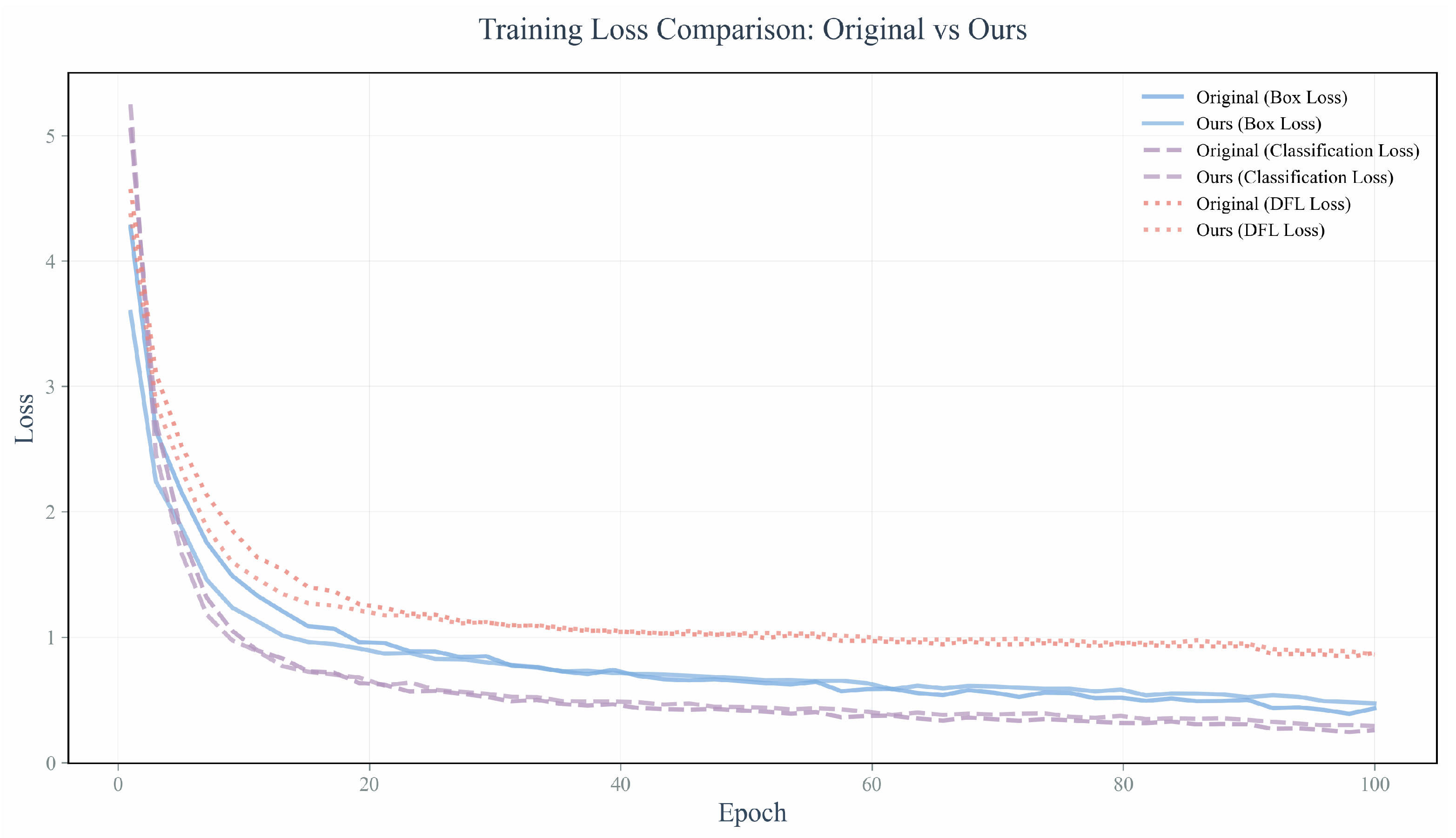

Figure 1 provides an insightful analysis of the training loss dynamics between the original and the proposed enhanced YOLOv11 model, specifically tailored for the intricate task of airport surface surveillance object detection. The visual representation meticulously delineates the progressive reduction in loss values for box, classification, and distribution focal loss components across the training epochs for both models under investigation. Strikingly, the enhanced YOLOv11 model, labeled as “ours,” demonstrates a consistently lower loss trajectory compared to its original counterpart, signifying its superior capacity for feature learning and generalization. This trend is particularly evident during the initial epochs, suggesting an accelerated convergence rate and a heightened proficiency in mitigating predictive errors. The divergence in loss reduction between the models becomes more pronounced as training progresses, underscoring the enhanced model’s ability to refine its predictive accuracy with greater efficiency.

These findings are instrumental in validating the hypothesis that the modifications incorporated into the YOLOv11 model result in a more robust and precise detection framework. The improved performance is critical for meeting the stringent precision requirements of airport surveillance systems, where accurate object detection is paramount for ensuring operational safety and efficiency. The comprehensive analysis of the training loss curves not only affirms the enhanced model’s superiority but also provides a robust empirical foundation for its potential deployment in real-world airport surveillance scenarios.

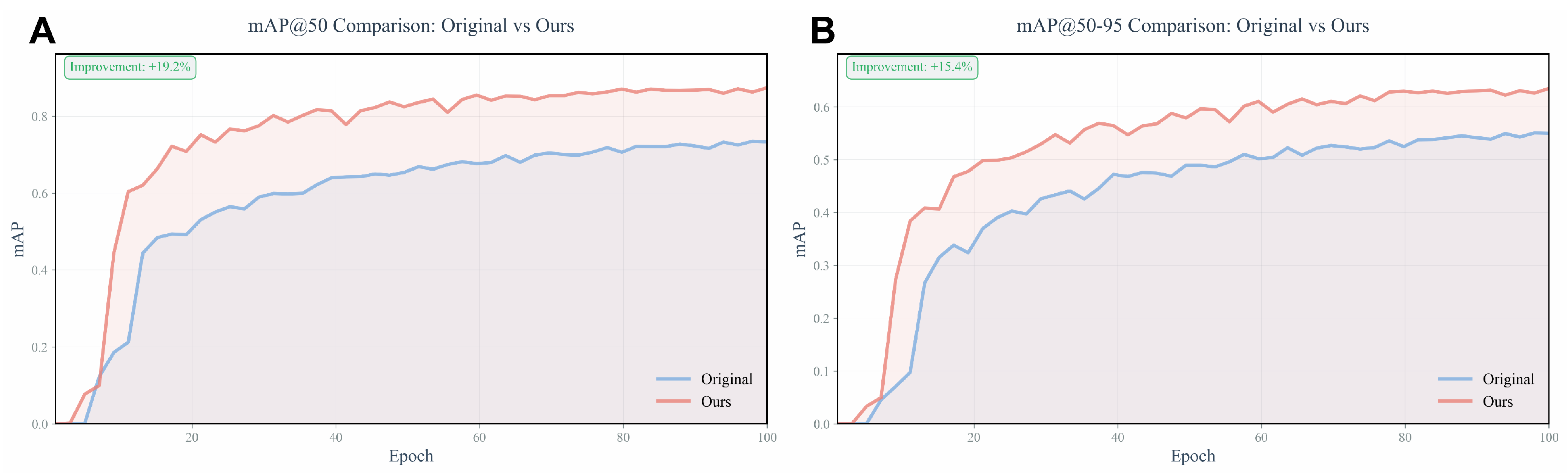

Figure 2 provides an academically rigorous assessment of the performance of the enhanced YOLOv11 model against the original model in the domain of airport surface surveillance object detection, focusing on two critical evaluation metrics: mAP@50 and mAP@50:95. Panel A illustrates the mAP@50 comparison, where the mAP (mean Average Precision) is measured at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.50. The enhanced model, denoted by the red curve, demonstrates a notable improvement of 19.2% over the original model, represented by the blue curve. This improvement signifies that the enhanced model achieves a higher precision in object detection tasks at a moderate IoU threshold, which is indicative of better localization accuracy.

Panel B presents the mAP@50-95 comparison, which evaluates the mAP across a range of IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95. The red curve again surpasses the blue curve, indicating a 15.4% enhancement. This metric is particularly informative as it assesses the model’s performance over a broader spectrum of IoU thresholds, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the model’s accuracy and robustness in detecting objects under varying conditions of overlap.

The convergence patterns of both panels reveal that the enhanced model not only reaches higher mAP values more rapidly but also maintains these superior performance levels throughout the training epochs. This consistent outperformance suggests that the modifications introduced in the YOLOv11 model lead to a more robust learning framework capable of generalizing across a wider range of detection scenarios.

In conclusion, the enhanced YOLOv11 model exhibits a significant advancement in object detection capabilities, as evidenced by the improved mAP metrics. These findings are of paramount importance for airport surface surveillance systems, where precise and reliable object detection is essential for ensuring the safety and efficiency of airport operations.

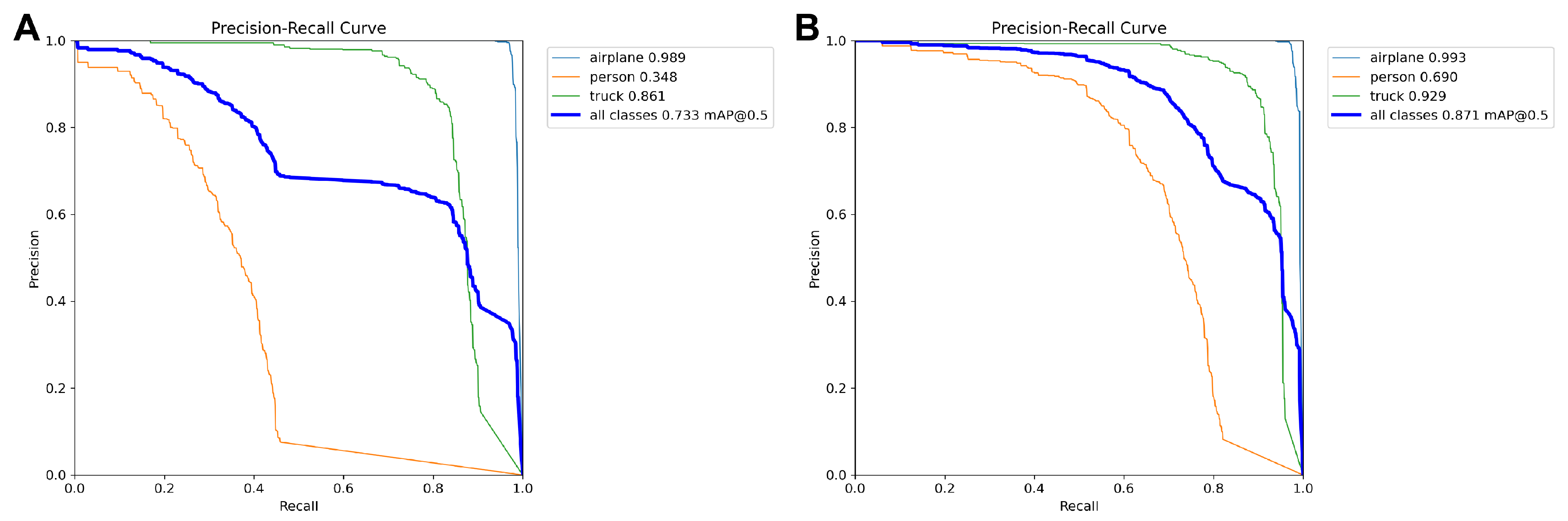

Figure 3 meticulously delineates the Precision–Recall (PR) curves for both the original model (Panel A) and the enhanced model (Panel B) across various object categories within the context of airport surface surveillance tasks. These curves provide a granular analysis of model performance with respect to different classes, including airplanes, individuals, and trucks, as well as an aggregate measure of performance across all classes.

In Panel A, the PR curves of the original model indicate a high precision rate for the airplane category, nearing perfection at 0.989, suggesting the model’s proficiency in detecting large, distinct objects. However, the precision rate for the individual category drops significantly to 0.348, likely due to the challenges associated with detecting smaller, less distinct targets that are prone to occlusion and confusion with complex backgrounds. The truck category exhibits a precision rate of 0.861, indicating a satisfactory level of detection capability. The mean Average Precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP@0.5) for all classes stands at 0.733, reflecting the model’s moderate performance in the overall object detection task.

Panel B presents a marked improvement in performance across all categories for the enhanced model. The airplane category’s precision rate ascends to 0.993, indicating an almost flawless detection capability. The individual category experiences a substantial increase in precision to 0.690, signifying a breakthrough in the model’s ability to discern small, subtle targets. The truck category’s precision rate improves to 0.929, further attesting to the enhanced model’s efficacy in detecting objects of moderate size. The overall mAP@0.5 across all classes is elevated to 0.871, corroborating the enhanced model’s superior performance and robustness in diverse object detection scenarios typical of airport ground surveillance.

Collectively, the enhanced model demonstrates superior precision and recall across the board compared to the original model, with particularly notable advancements in the challenging task of detecting individuals. These findings underscore the enhanced model’s heightened efficacy in managing the complexities of airport ground surveillance object detection tasks, thereby offering substantial support for enhancing the safety and efficiency of airport operations. This improvement holds significant theoretical and practical implications for the design and implementation of automated surveillance systems, especially in the context of airport ground surveillance where high-precision object detection is paramount.

4.3.2. Ablation Experiment

Table 2 presents an updated ablation study that meticulously examines the incremental contributions of various architectural enhancements to an airport surface surveillance object detection model. The study provides a comprehensive analysis of the model’s performance metrics, including the number of layers, parameter count, computational complexity (GFLOPs), mean Average Precision (mAP) at different IoU thresholds, and class-specific mAP for airplanes, persons, and trucks.

Model A, serving as the baseline, features a 190-layer architecture with 56.83 million parameters and a computational load of 194.4 GFLOPs. It achieves a mAP@0.5 of 0.736 and a mAP@0.5-0.95 of 0.554, indicating a moderate level of performance. The class-specific mAP reveals a high detection accuracy for airplanes (0.989) and trucks (0.862), but a notably lower performance for persons (0.356), suggesting a challenge in detecting smaller or less distinct targets.

Model B introduces the GhostNetV2 module, which reduces the parameter count to 32.98 million and the computational complexity to 140.9 GFLOPs, resulting in a more efficient model. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of a slight decrease in mAP@0.5 to 0.721 and mAP@0.5-0.95 to 0.548. The class-specific mAP shows a marginal improvement for persons (0.324) but a slight decrease for trucks (0.848), indicating that while GhostNetV2 enhances model efficiency, it may not be optimal for all detection tasks.

Model C incorporates the PKI Block, which increases the number of layers to 466 but maintains a similar parameter count of 38.77 million and a computational complexity of 242.5 GFLOPs. This model shows a significant improvement in mAP@0.5 to 0.852 and mAP@0.5-0.95 to 0.616, suggesting that the PKI Block effectively enhances feature extraction and target detection. The class-specific mAP also improves, particularly for persons (0.642), indicating a better capability in detecting smaller targets.

Model D further refines Model C by incorporating the Shape-IoU loss, which maintains the same number of layers and parameter count but slightly improves the mAP@0.5 to 0.876 and mAP@0.5-0.95 to 0.641. The class-specific mAP for persons (0.722) and trucks (0.963) reaches the highest among all models, demonstrating the Shape-IoU loss’s effectiveness in refining bounding box predictions and improving localization accuracy.

In conclusion, the ablation study results underscore the unique contributions of each module to the overall performance of the airport surface surveillance object detection model. The GhostNetV2 module enhances model efficiency, the PKI Block improves feature extraction and detection accuracy, and the Shape-IoU loss refines bounding box predictions. These enhancements collectively provide a robust framework for improving the safety and efficiency of airport operations by enhancing the model’s ability to accurately detect various targets under diverse surveillance conditions.

4.3.3. Comparison Experiment

Table 3 presents an exhaustive comparison of various YOLO models in the context of airport surface surveillance object detection tasks. The table encompasses key metrics such as the number of layers, parameter count, computational complexity (GFLOPs), mean Average Precision (mAP) at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds, and class-specific mAP for airplanes, persons, and trucks.

The YOLO11x model, serving as the baseline, comprises 190 layers with a parameter count of 56.83 million and a computational complexity of 194.4 GFLOPs. It achieves a mAP@0.5 of 0.736 and a mAP@0.5-0.95 of 0.554, indicating a moderate level of performance. However, its mAP for the person class is a mere 0.356, suggesting a performance bottleneck in identifying small or complexly backgrounded targets.

The YOLOv10x model, through the reduction of parameter count to 29.40 million and computational complexity to 160.0 GFLOPs, achieves model lightweighting. However, this simplification leads to a slight decrease in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5-0.95 to 0.685 and 0.521, respectively, with the person class mAP further dropping to 0.348, confirming the negative impact of model simplification on small target detection performance.

The YOLOv9e model, despite having 279 layers and a parameter count of 57.38 million, exhibits a computational complexity of 189.1 GFLOPs. It shows a mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5-0.95 of 0.692 and 0.52, respectively, which is slightly lower than the YOLO11x. The person class mAP is 0.237, indicating limited capability in small target detection.

The YOLOv8x model, with a parameter count as high as 68.13 million but a computational complexity of 257.4 GFLOPs, demonstrates efficiency in computational resource utilization. It achieves a mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5-0.95 of 0.688 and 0.525, respectively, slightly lower than the YOLO11x. However, the person class mAP is 0.226, further highlighting the challenge in small target detection.

The YOLOv6x model, although having fewer layers at 120 but a high parameter count of 172.98 million and a computational complexity of 608.3 GFLOPs, shows the highest computational demand. Its mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5-0.95 are 0.592 and 0.455, significantly lower than other models. Particularly, the person class mAP is only 0.056, significantly revealing the model’s inadequacy in handling small targets.

In stark contrast, our model (Ours), through the introduction of advanced structural and loss function enhancements, achieves a significant improvement across all evaluation metrics. With 466 layers, a parameter count of 38.77 million, and a computational complexity of 242.5 GFLOPs, our model attains a mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5-0.95 of 0.876 and 0.641, respectively, which is markedly superior to other models. Notably, for the person class, our model achieves an mAP of 0.680, demonstrating a substantial advancement in small target detection. Additionally, our model attains the highest mAP for airplanes and trucks, at 0.993 and 0.961, respectively.

In summary, our model exhibits exceptional performance in airport surface surveillance object detection tasks, particularly in handling small targets and complex backgrounds. These findings indicate that through meticulously designed model structures and loss functions, the detection performance can be effectively enhanced, providing robust technical support for improving the safety and efficiency of airport operations. These insights not only offer a novel perspective in the field of airport surface surveillance but also serve as invaluable references for the design and optimization of future object detection models.

4.3.4. Multi-Model Scenario Application Comparison

The comparative analysis illustrated in

Figure 4, the provided images is designed to rigorously assess the effectiveness of various object detection algorithms within the context of airport surface surveillance. By conducting such a comparison, it is possible to delve into the performance nuances of each algorithm concerning detection accuracy, completeness of target identification, and the confidence levels associated with predictions. This analysis is crucial for identifying the most suitable object detection model for integration into airport surveillance systems.

Upon examination of the visual data, our model (referred to as “Ours”) demonstrates superior performance across multiple dimensions. It exhibits a high degree of accuracy in identifying and localizing objects such as airplanes, individuals, and trucks. When compared with alternative algorithms, our model consistently achieves a lower rate of missed detections and false positives. For instance, in several frames, while other algorithms may fail to recognize certain airplanes or individuals, our model successfully detects these entities with precision.

Furthermore, our model assigns notably high confidence scores around the detected objects, signifying robust assurance in its predictions. These elevated confidence levels are indicative of the model’s reliability, which is essential for airport surveillance to minimize false alarms and oversights, thereby enhancing the dependability of the monitoring system.

Our model also maintains consistent performance across diverse environmental conditions, including variations in lighting, weather, and time of day. This consistency underscores the model’s robustness, ensuring uniform detection outcomes across a range of real-world surveillance scenarios. Additionally, our model excels in capturing finer details of targets; for example, when detecting airplanes, it is capable of accurately identifying them even at greater distances or when they are of smaller size, concurrently providing high confidence scores.

In conclusion, our model outperforms its counterparts in the task of airport surface surveillance object detection, showcasing superior detection integrity, predictive accuracy, and confidence scoring. These attributes make our model a reliable choice for adoption within airport monitoring systems, promising to augment surveillance efficiency and security. This comprehensive analysis highlights the model’s potential to significantly contribute to the advancement of automated surveillance technologies within the aviation sector.