TECP: Token-Entropy Conformal Prediction for LLMs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

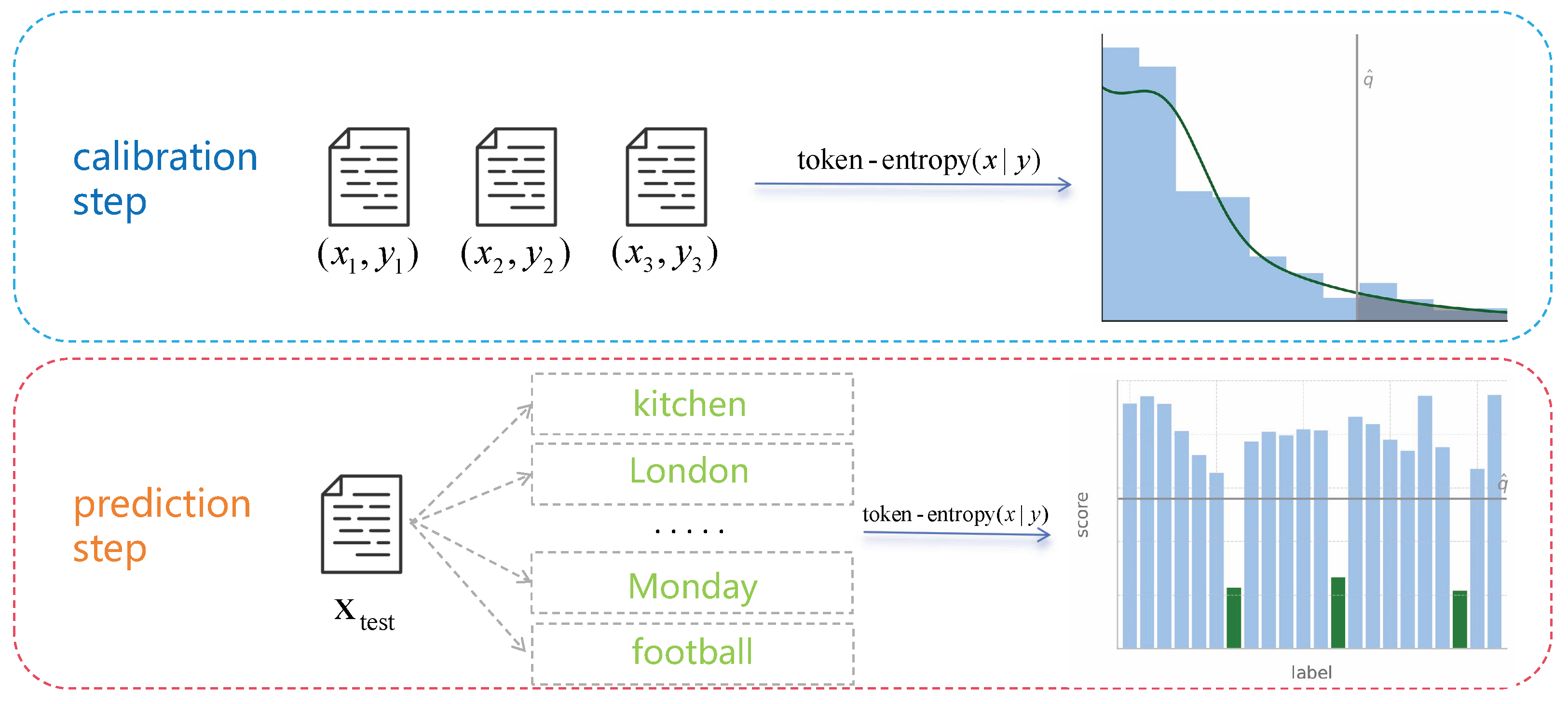

3. Method

3.1. Problem Setup and Candidate Generation Mechanism

3.2. Uncertainty Estimation via Token Entropy

3.3. Uncertainty Calibration and Prediction Set Construction

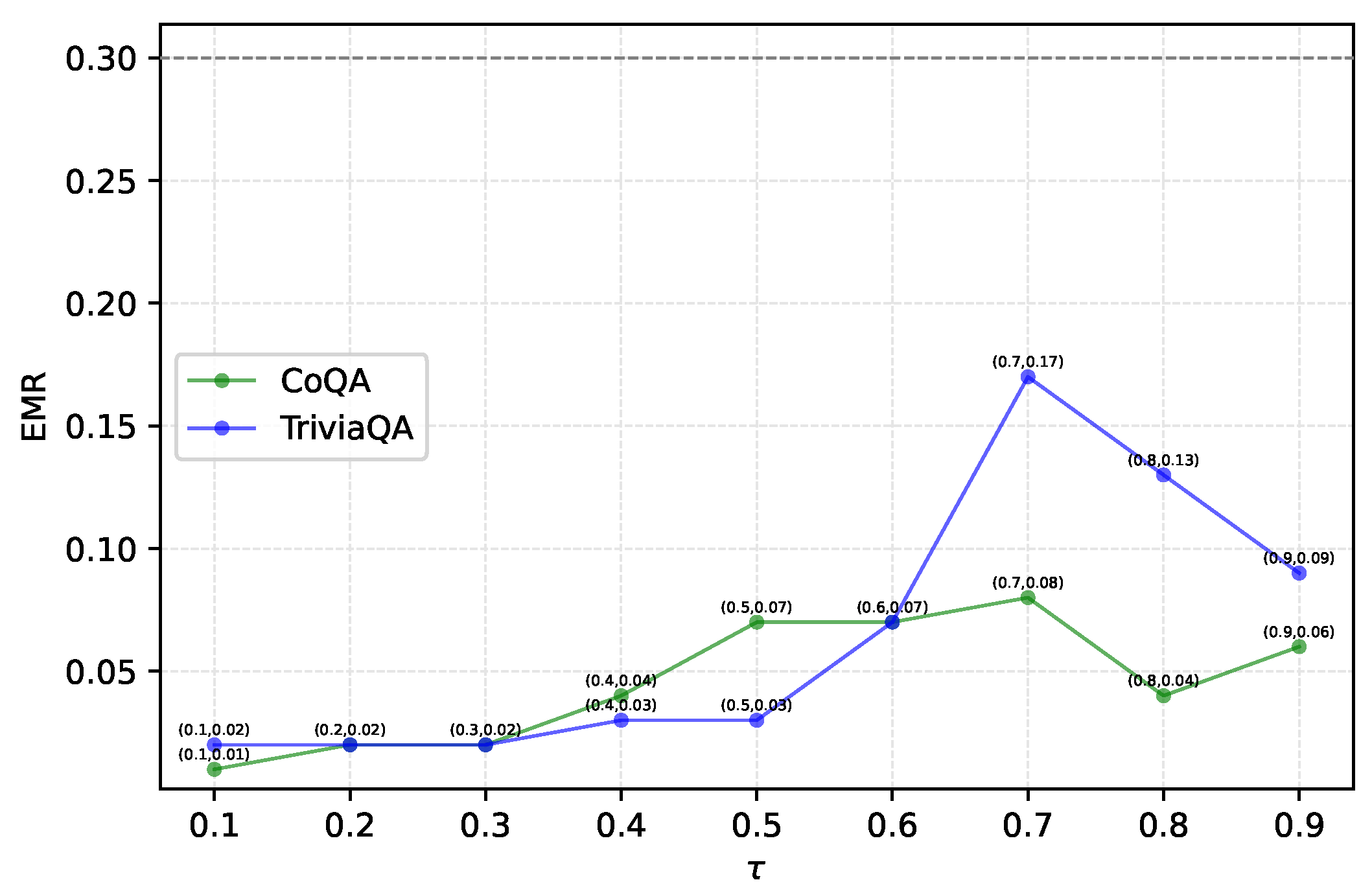

- Data partitioning and filtering. For each sample , if there exists a candidate such that , the sample is deemed assessable (i.e., of acceptable generation quality). Moreover, it is retained in , where is a semantic-matching threshold typically in the range –. We then randomly split into a calibration subset and a test subset in a user-specified ratio.

- Construction of the nonconformity score multiset . On , we collect uncertainty scores of the (semantically correct) candidates:Using all the candidates is a permissible, more conservative variant.

- Quantile-based confidence threshold. For target coverage , we order increasingly and take the -th order statistic as the empirical threshold :where . We use a “higher” interpolation rule to avoid underestimating the threshold and thereby preserve coverage.

- Prediction set construction. For any test input x, we defineBy construction, achieves a nominal coverage of at least for the ground-truth answer under exchangeability. We caution that pre-filtering calibration samples as “assessable” may affect exchangeability; we, therefore, report sensitivity to the semantic threshold and also consider a no-filter variant as a conservative baseline.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

- ConU. A prediction method is proposed based on Conformal Uncertainty, which evaluates candidate responses generated for each input prompt and quantifies predictive uncertainty by incorporating both model confidence scores and calibration error. In contrast to heuristic approaches that rely solely on response-level variability, ConU offers a principled mechanism for constructing prediction sets with theoretical risk control guarantees. Notably, the method does not require access to model log-probabilities, yet is still able to retain high-confidence responses selectively. It enables the construction of prediction sets that are statistically guaranteed to meet predefined risk levels, while remaining representative, stable, and interpretable.

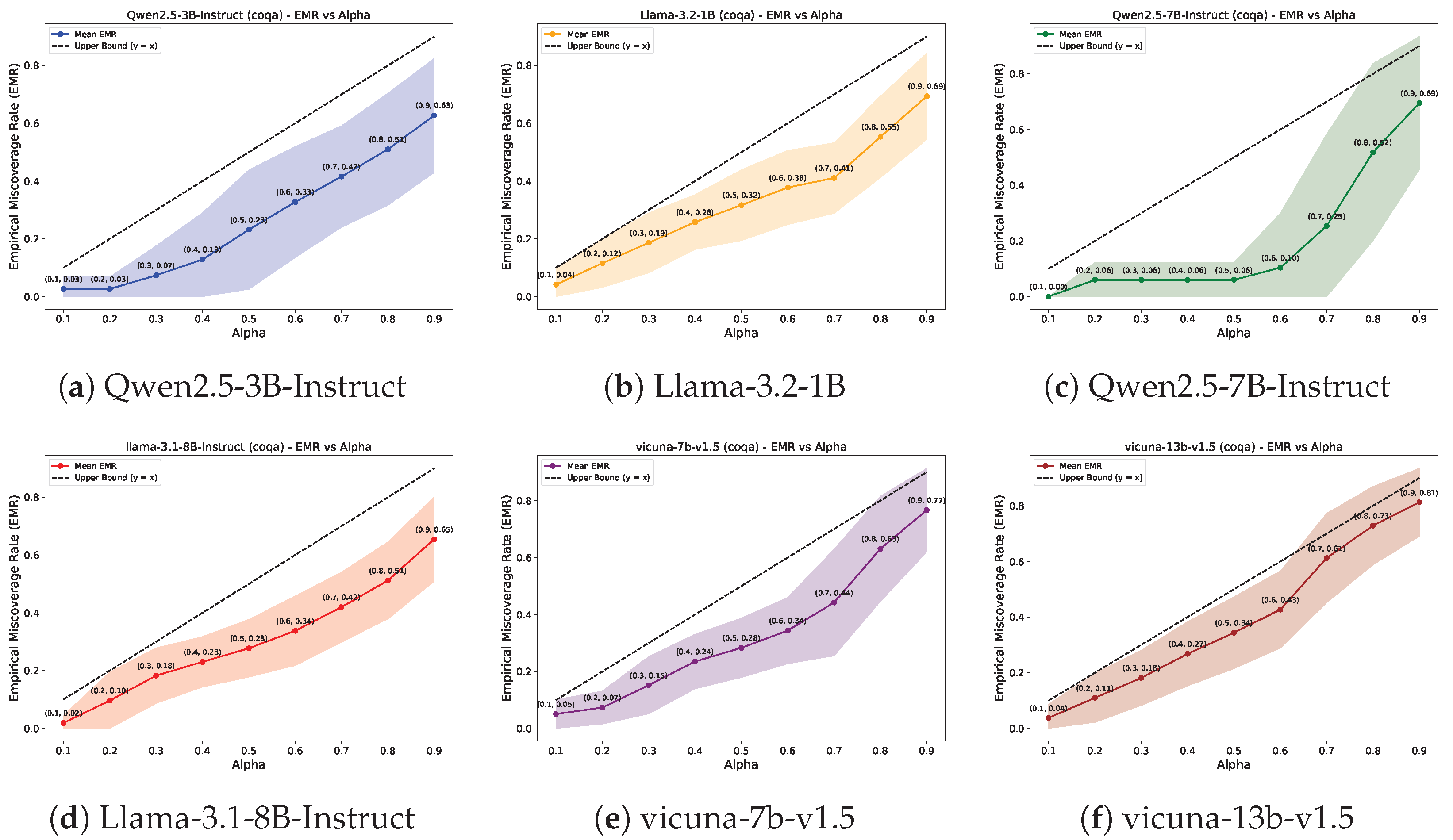

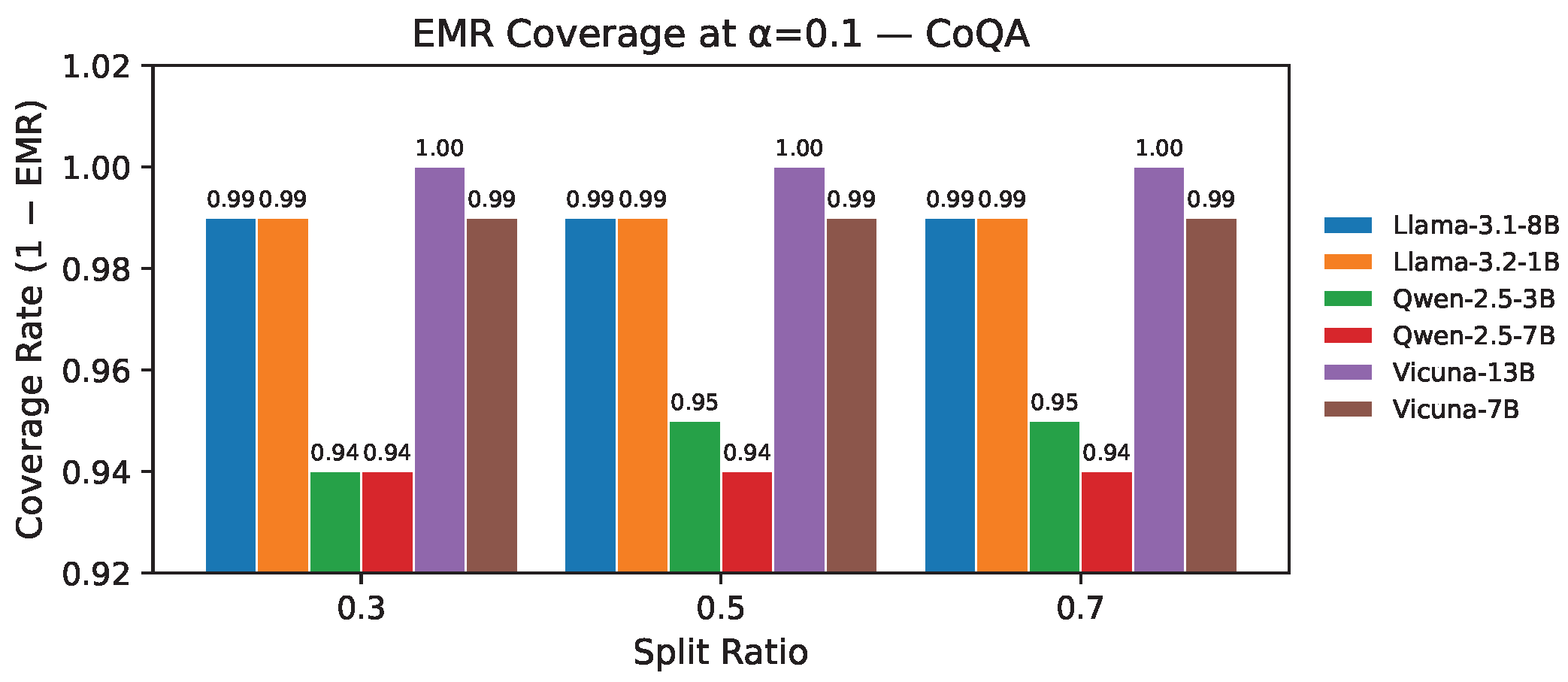

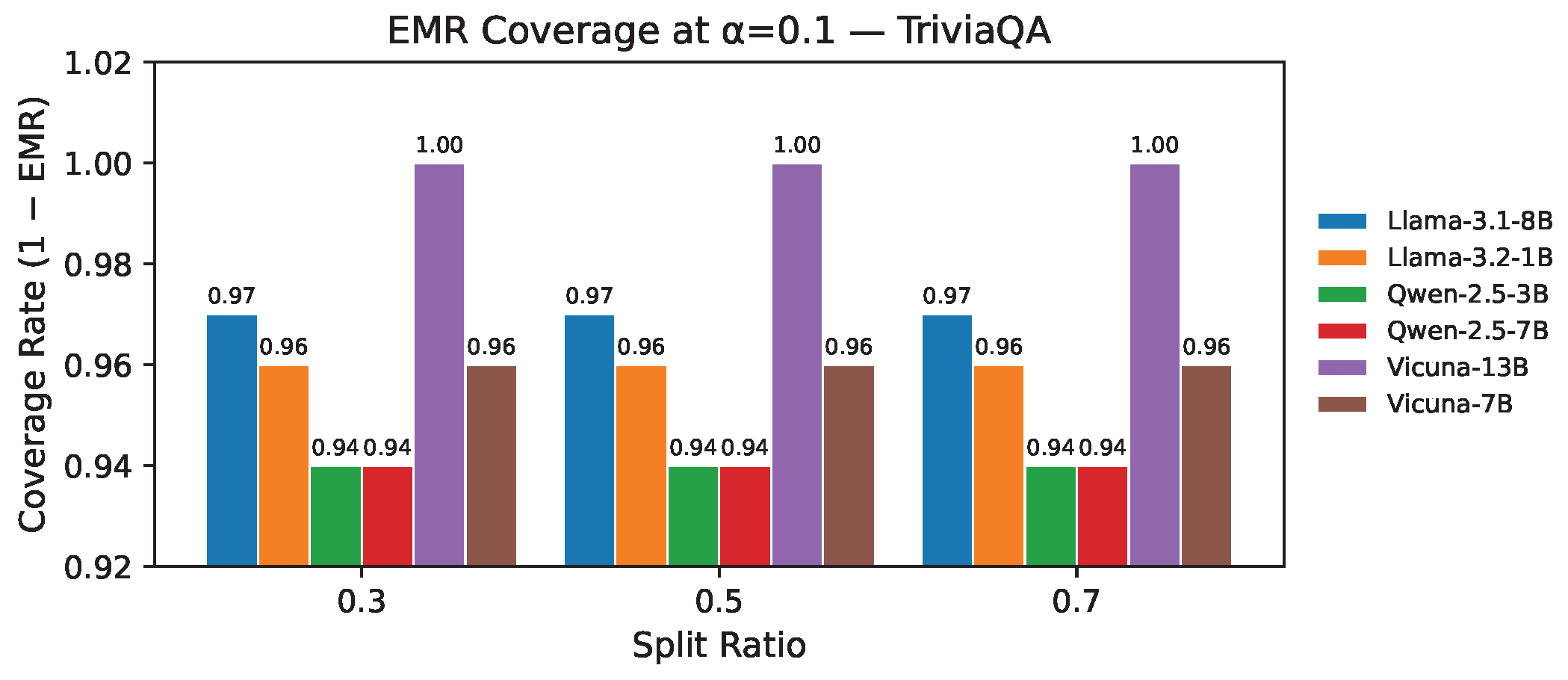

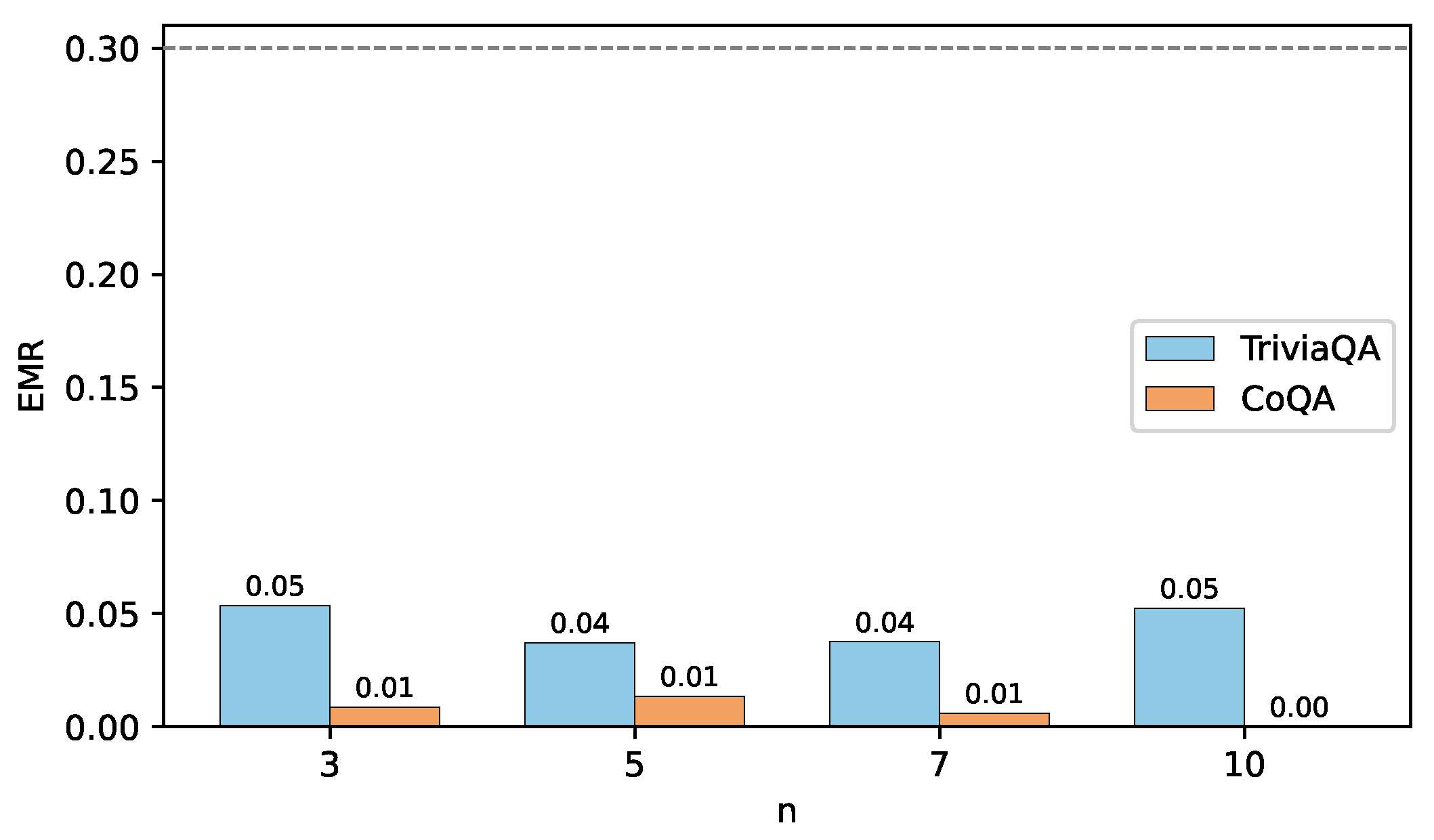

- Empirical miscoverage rate (EMR) quantifies the proportion of instances where the prediction set contains at least one output that passes the correctness criterion (higher is better). It captures the set’s validity.

- Average prediction set size (APSS) computes the mean cardinality of prediction sets across the evaluation corpus. Lower values indicate greater efficiency.

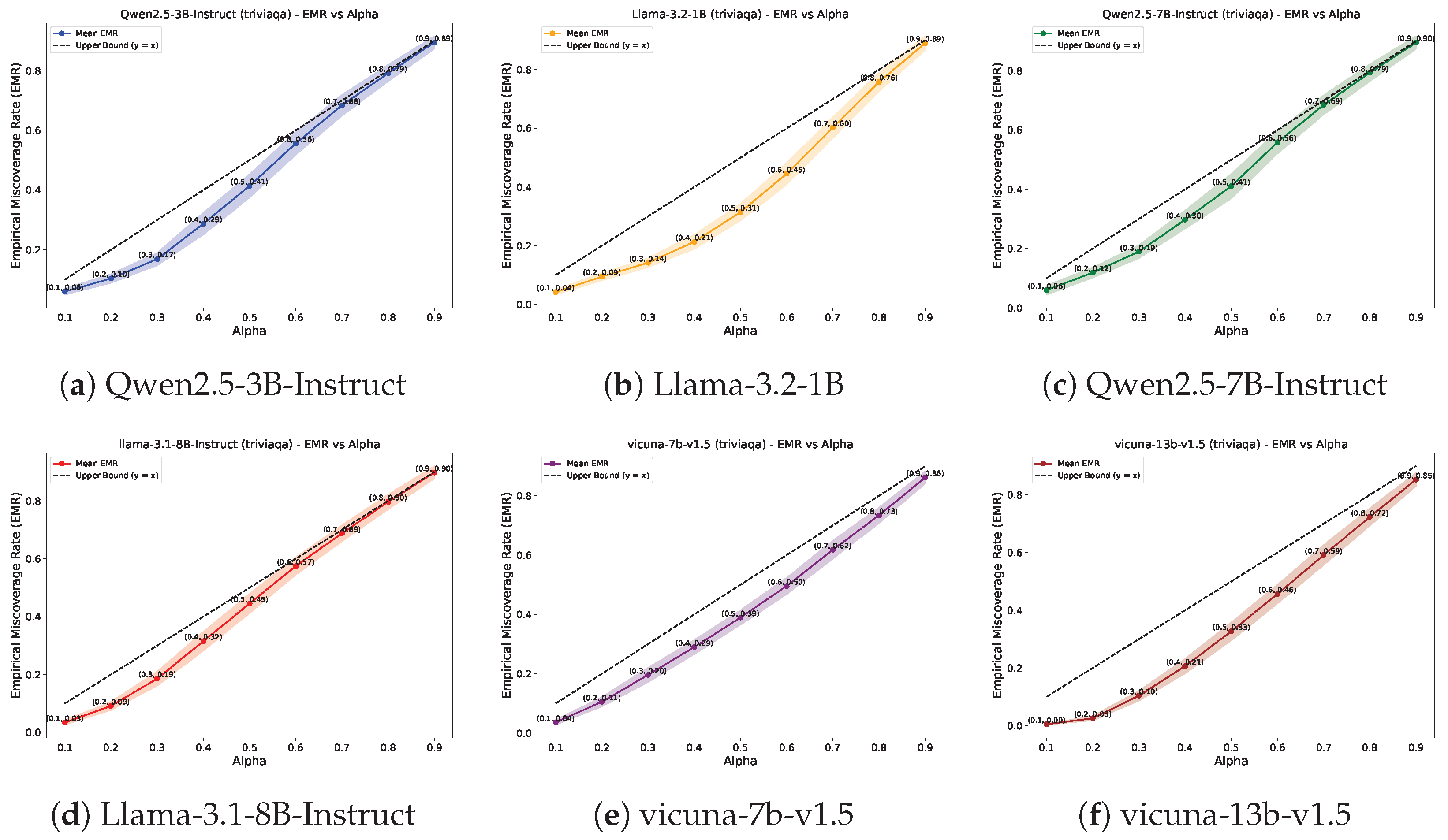

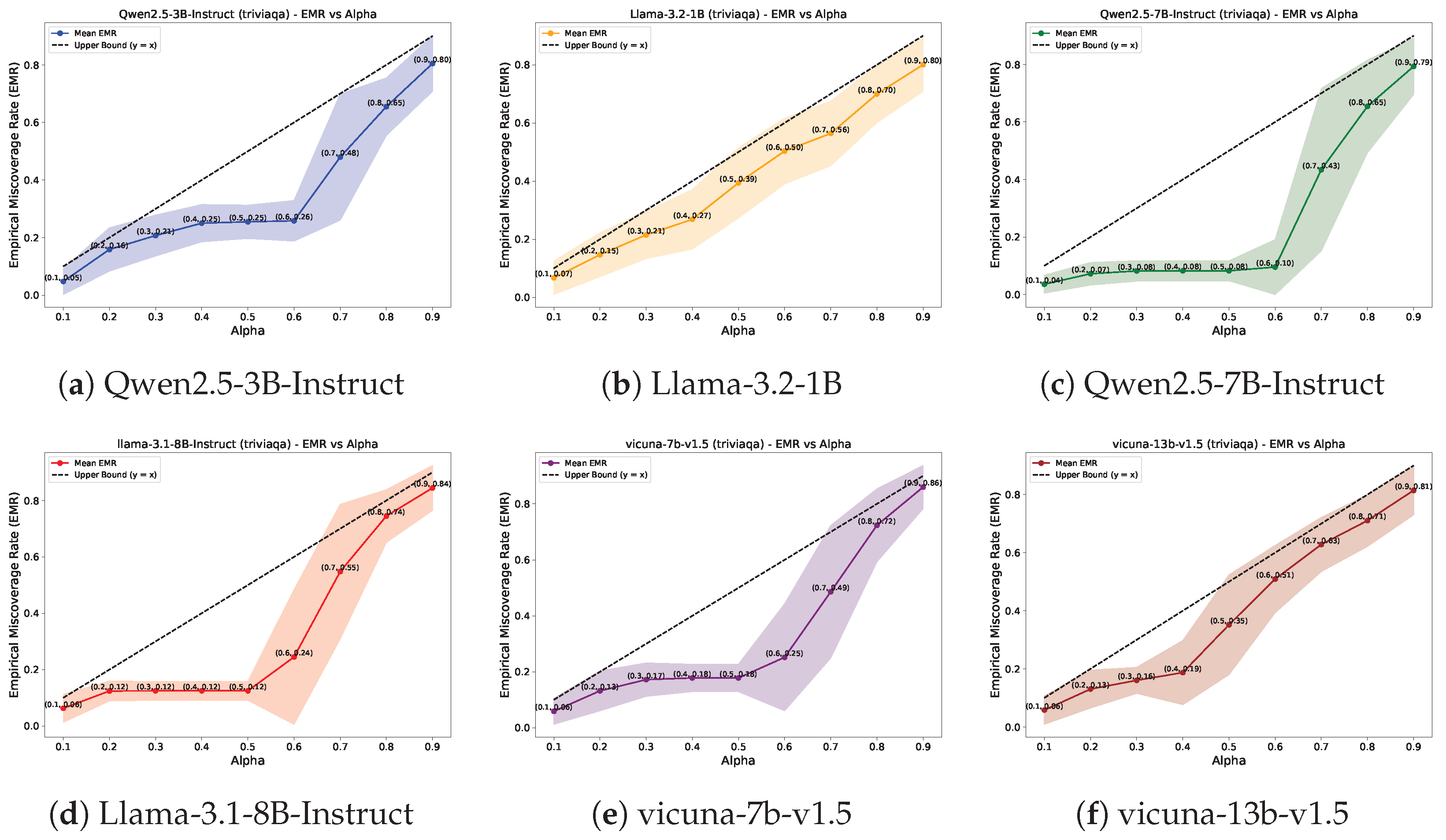

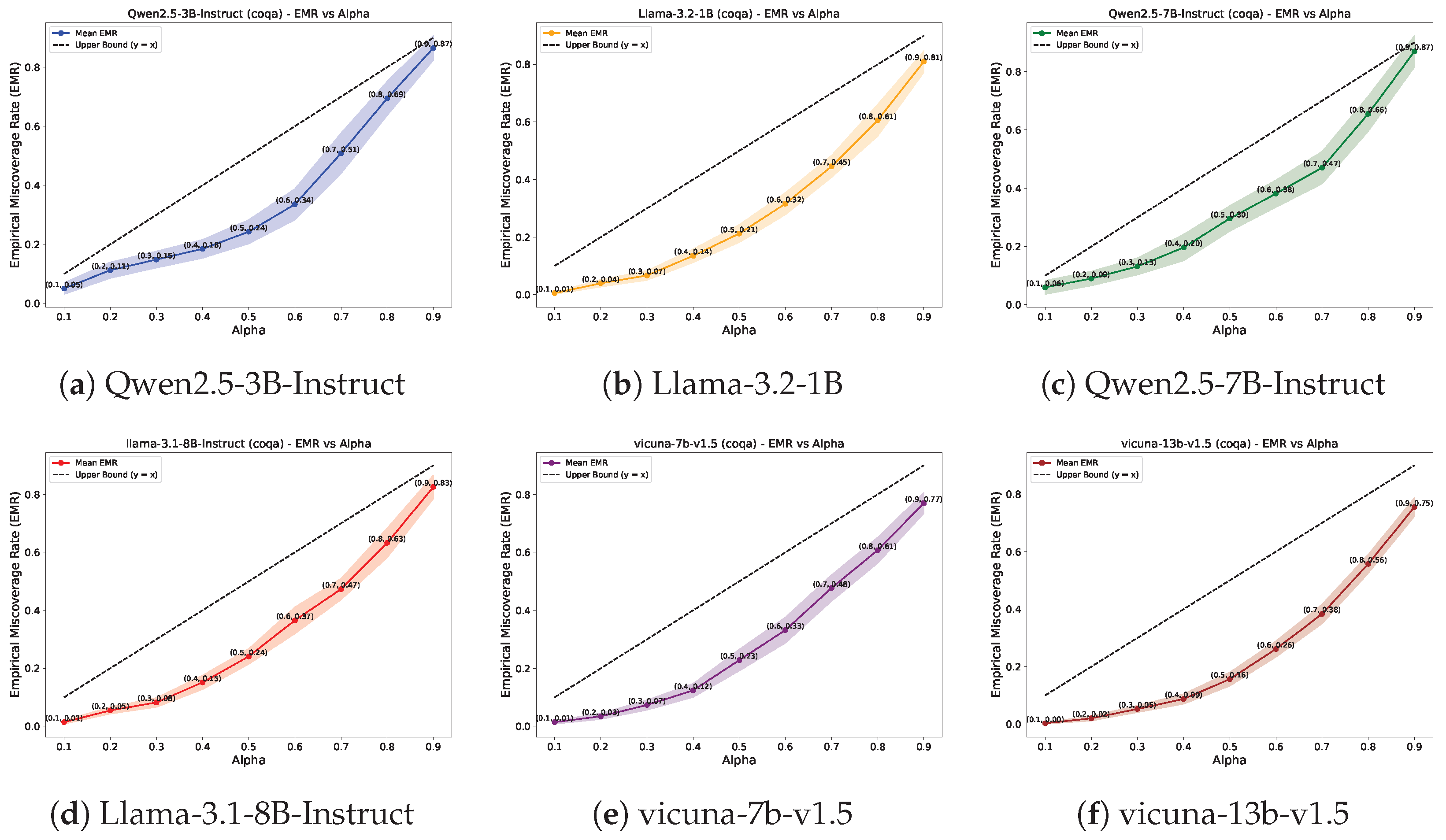

4.2. Results for QA

4.3. Ablation Study

4.4. Comparison with Baseline

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, Y.; Duan, J.; Xu, K.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. A Survey on Large Language Model (LLM) Security and Privacy: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. High-Confid. Comput. 2024, 4, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramachaneni, V. Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Survey on Architectures, Applications, and Challenges. Adv. Innov. Comput. Program. Lang. 2025, 7, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Bi, J.; Lan, J.; Gu, J.; Grosser, C.; Krompass, D.; et al. Does Machine Unlearning Truly Remove Model Knowledge? A Framework for Auditing Unlearning in LLMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.23270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, X.; Huang, W.; Liang, J.; Bi, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, Y.; Du, B.; Ye, M. Backdoor Cleaning without External Guidance in MLLM Fine-Tuning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.16916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Bi, J.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, F.; Du, Y.; Tian, Y. MV-Debate: Multi-View Agent Debate with Dynamic Reflection Gating for Multimodal Harmful Content Detection in Social Media. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.05557. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Wei, J.; Xiao, D.; Wang, S.; Wu, T.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; et al. PediatricsGPT: Large Language Models as Chinese Medical Assistants for Pediatric Applications. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 138632–138662. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, L. MISS: A Generative Pre-Training and Fine-Tuning Approach for Med-VQA. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks (ICANN), Lugano, Switzerland, 17–20 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Bi, J.; Gu, J.; Chen, Y.; Tresp, V. SPOT! Revisiting Video-Language Models for Event Understanding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.12919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, M.; Wei, J.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, L. Can LLMs’ Tuning Methods Work in Medical Multimodal Domain? In Proceedings of the MICCAI, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 43, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrinovics, E.; Biswas, R.; Bjerva, J.; Hose, K. Knowledge Graphs, Large Language Models, and Hallucinations: An NLP Perspective. J. Web Semant. 2025, 85, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.; Lee, Z.; Ye, W.; Zhang, S. Hademif: Hallucination Detection and Mitigation in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, D.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Wu, T.; Li, K.; Zhang, L. CoMT: Chain-of-Medical-Thought Reduces Hallucination in Medical Report Generation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025—IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, S.; Kossen, J.; Kuhn, L.; Gal, Y. Detecting Hallucinations in Large Language Models Using Semantic Entropy. Nature 2024, 85, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, S.; Zavalny, A.; Wang, C.; Xu, R.; Kailkhura, B.; Xu, K. Shifting Attention to Relevance: Towards the Predictive Uncertainty Quantification of Free-Form Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X.; Miikkulainen, R. Semantic Density: Uncertainty Quantification for Large Language Models Through Confidence Measurement in Semantic Space. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 134507–134533. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Duan, J.; Yuan, C.; Chen, Q.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Shi, X.; Xu, K. Word-Sequence Entropy: Towards Uncertainty Estimation in Free-Form Medical Question Answering Applications and Beyond. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Duan, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shi, X.; Xu, K.; Shen, H.T.; Zhu, X. ConU: Conformal Uncertainty in Large Language Models with Correctness Coverage Guarantees. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Miami, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Cross, M.; Calderon-Ramirez, S. Uncertainty Estimation in Large Language Models to Support Biodiversity Conservation. Proceedings of NAACL 2024: Industry Track, Mexico City, Mexico, 16–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Shen, C.; Li, X.; Lu, J. Uncertainty Quantification for Safe and Reliable Autonomous Vehicles: A Review of Methods and Applications. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 2880–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Li, N.; Feng, K.; Wang, Z.; Tan, Y.; Li, H. Machinery Multimodal Uncertainty-Aware RUL Prediction: A Stochastic Modeling Framework for Uncertainty Quantification and Informed Fusion. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 31643–31653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, D.; Wu, T.; Jiang, Y.; Hou, X.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Xiao, D.; Li, K.; Zhang, L. Detecting and Evaluating Medical Hallucinations in Large Vision Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bi, J.; Ma, Y.; Pirk, S. ASCD: Attention-Steerable Contrastive Decoding for Reducing Hallucination in MLLM. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.14766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadavath, S.; Conerly, T.; Askell, A.; Henighan, T.; Drain, D.; Perez, E.; Schiefer, N.; Dodds, Z.; German, M.; Johnston, S.; et al. Language Models (Mostly) Know What They Know. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.05221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, L.; Gal, Y.; Farquhar, S. Semantic Uncertainty: Linguistic Invariances for Uncertainty Estimation in Natural Language Generation. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Malinin, A.; Gales, M. Uncertainty Estimation in Autoregressive Structured Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 4–8 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Hilton, J.; Evans, O. TruthfulQA: Measuring How Models Mimic Human Falsehoods. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Q.; Bao, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, Z.; Zou, C. Conformal Prediction with Cellwise Outliers: A Detect-then-Impute Approach. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Snell, J.C.; Griffiths, T.L. Conformal Prediction as Bayesian Quadrature. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhu, X.; Shi, X.; Xu, K. SConU: Selective Conformal Uncertainty in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, R.F.; Candès, E.J.; Ramdas, A.; Tibshirani, R.J. Conformal Prediction Beyond Exchangeability. Ann. Stat. 2023, 51, 816–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, A.N.; Bates, S. Conformal Prediction: A Gentle Introduction. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 2023, 16, 494–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Duan, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Chen, T.; Shi, X.; Xu, K. COIN: Uncertainty-Guarding Selective Question Answering for Foundation Models with Provable Risk Guarantees. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iutzeler, F.; Mazoyer, A. Risk-Controlling Prediction with Distributionally Robust Optimization. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Geng, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Fu, B.; Zheng, F. Sample then Identify: A General Framework for Risk Control and Assessment in Multimodal Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | LLMs/ | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TriviaQA | Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | 9.02 | 8.05 | 7.06 | 6.10 | 5.10 | 4.06 | 3.03 | 2.00 | 1.02 |

| Llama-3.2-1B | 9.00 | 7.99 | 6.99 | 6.00 | 5.00 | 4.00 | 3.01 | 1.99 | 1.01 | |

| Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct | 9.01 | 8.03 | 7.02 | 6.00 | 4.97 | 3.95 | 2.96 | 2.00 | 1.00 | |

| Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct | 8.99 | 7.99 | 7.00 | 6.00 | 4.99 | 4.00 | 3.02 | 2.03 | 1.05 | |

| vicuna-7b-v1.5 | 9.01 | 8.00 | 6.99 | 6.02 | 5.02 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 1.01 | |

| vicuna-13b-v1.5 | 9.00 | 7.98 | 6.97 | 5.98 | 4.97 | 3.99 | 3.00 | 1.99 | 1.02 | |

| CoQA | Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | 9.02 | 8.02 | 7.01 | 6.02 | 5.03 | 4.03 | 3.03 | 2.01 | 1.00 |

| Llama-3.2-1B | 9.00 | 7.99 | 7.01 | 6.01 | 5.01 | 4.03 | 3.03 | 2.02 | 1.02 | |

| Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct | 8.95 | 8.01 | 7.03 | 6.01 | 5.02 | 4.03 | 3.04 | 2.05 | 1.01 | |

| Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct | 8.95 | 7.96 | 6.99 | 6.02 | 5.03 | 4.02 | 3.00 | 2.03 | 1.01 | |

| vicuna-7b-v1.5 | 9.00 | 8.00 | 7.00 | 6.01 | 5.01 | 4.01 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | |

| vicuna-13b-v1.5 | 8.98 | 7.98 | 6.98 | 5.98 | 4.98 | 3.98 | 2.98 | 2.00 | 1.02 |

| Dataset | LLMs/Threshold | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TriviaQA | Llama-3.2-1B | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.73 |

| llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.23 | |

| vicuna-7b-v1.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| vicuna-13b-v1.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.52 | |

| Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.42 | |

| CoQA | Llama-3.2-1B | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.87 | |

| vicuna-7b-v1.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| vicuna-13b-v1.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.90 | |

| Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, B.; Lu, Y. TECP: Token-Entropy Conformal Prediction for LLMs. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3351. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203351

Xu B, Lu Y. TECP: Token-Entropy Conformal Prediction for LLMs. Mathematics. 2025; 13(20):3351. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203351

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Beining, and Yongming Lu. 2025. "TECP: Token-Entropy Conformal Prediction for LLMs" Mathematics 13, no. 20: 3351. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203351

APA StyleXu, B., & Lu, Y. (2025). TECP: Token-Entropy Conformal Prediction for LLMs. Mathematics, 13(20), 3351. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203351