Abstract

High-quality image restoration (IR) is a fundamental task in computer vision, aiming to recover a clear image from its degraded version. Prevailing methods typically employ a static inference pipeline, neglecting the spatial variability of image content and degradation, which makes it difficult for them to adaptively handle complex and diverse restoration scenarios. To address this issue, we propose a novel adaptive image restoration framework named Hybrid Convolutional Transformer with Dynamic Prompting (HCTDP). Our approach introduces two key architectural innovations: a Spatially Aware Dynamic Prompt Head Attention (SADPHA) module, which performs fine-grained local restoration by generating spatially variant prompts through real-time analysis of image content and a Gated Skip-Connection (GSC) module that refines multi-scale feature flow using efficient channel attention. To guide the network in generating more visually plausible results, the framework is optimized with a hybrid objective function that combines a pixel-wise L1 loss and a feature-level perceptual loss. Extensive experiments on multiple public benchmarks, including image deraining, dehazing, and denoising, demonstrate that our proposed HCTDP exhibits superior performance in both quantitative and qualitative evaluations, validating the effectiveness of the adaptive restoration framework while utilizing fewer parameters than key competitors.

Keywords:

image restoration; dynamic prompting; transformer; adaptive restoration; attention mechanism MSC:

68U10; 68T07

1. Introduction

With the widespread application of intelligent technologies in urban management and public safety, high-quality image data has become a cornerstone for enhancing urban operational efficiency and ensuring public security. However, in practical scenarios such as urban surveillance and emergency response, the acquisition, transmission, and storage of images are often affected by complex environmental factors like adverse weather (e.g., rain and haze), leading to severe degradation of image quality. These prevalent degradation phenomena not only compromise the fidelity and usability of information but also directly impact the accuracy and reliability of subsequent systems for object detection, intelligent monitoring, and emergency response [1]. Therefore, recovering clear images from these complex and variably degraded images has become a core challenge in the field of computer vision.

Current mainstream image restoration (IR) methods are primarily dominated by Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [2] and Transformers [3]. CNN-based models, such as NAFNet [4], rely on local convolutional operators. While adept at capturing local textures, their limited receptive fields present inherent deficiencies in modeling long-range dependencies and global structures. To overcome this drawback, recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, such as SwinIR [5] and Restormer [6], have adopted the Transformer architecture [3,7] to capture global context. The model’s central self-attention mechanism is adept at modeling long-range dependencies among pixels, thereby enabling considerable advancements in performance.

However, despite their success, these mainstream methods share a fundamental limitation: their core restoration pipelines are static and apply operations homogeneously across all spatial locations. This “one-size-fits-all” approach fails to account for the spatial variability inherent in real-world degradations, such as haze that is denser in the background than the foreground, or rain streaks that are sparse and randomly distributed. For CNN-based models, this limitation stems from the spatial invariance of convolutional kernels; the same learned filter is applied indiscriminately to a clear patch of sky and a heavily corrupted region of complex texture, which is a suboptimal strategy. Similarly, for Transformer-based models, although self-attention can model global relationships, the computation is inherently uniform—all image patches undergo the same transformation process. This lacks a mechanism to dynamically adjust the restoration strategy or intensity based on the local image content and degradation level. This failure to perform spatially adaptive processing constitutes a core bottleneck for further performance improvement in image restoration.

To break through this bottleneck, this paper proposes a novel adaptive image restoration framework named HCTDP (Hybrid Convolutional Transformer with Dynamic Prompting). Our model achieves fine-grained image processing by introducing a dynamic, content-aware restoration mechanism built upon a hybrid convolutional Transformer U-Net backbone. Our core innovations and main contributions are summarized as follows:

- Content-Adaptive Dynamic Prompting Mechanism: We propose a Spatially Aware Dynamic Prompt Head Attention (SADPHA) module. By analyzing local features at multiple network scales to generate prompt vectors that parameterize and modulate the restoration operators, this module addresses the fundamental limitation of traditional models that use static operators, thus effectively preventing structural artifacts and the loss of high-frequency details.

- Efficient Skip-Connection Refinement Scheme: To suppress noise in the encoder’s feature stream, we introduce a Gated Skip-Connection (GSC) module. This module integrates an Efficient Channel Attention Network (ECA-Net) [8] within the skip connections, acting as a lightweight feature filter through its non-dimensionality-reducing local cross-channel interaction capability. This design enhances the suppression of irrelevant information while ensuring the effective fusion of multi-scale features.

- Perception-Oriented Optimization Objective: We designed and validated a hybrid loss function that combines a pixel-level L1 loss with a feature-level perceptual loss [9]. This optimization objective guides the network to generate results that are structurally and texturally more realistic and better aligned with human visual perception.

2. Related Work

2.1. Image Restoration

Image restoration aims to recover a clear image from its degraded version in a semantically plausible and visually realistic manner. The technological evolution in this field has been primarily driven by two major architectures: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers.

Early work in image restoration primarily employed CNN architectures, with U-Net [10] being a representative example. However, these initial models faced significant challenges with irregularly shaped degraded regions, as standard convolutions treat all input pixels equally, often leading to color discrepancies and blurring artifacts around the restored areas [11,12]. To address this structural problem, specialized convolution mechanisms were proposed. Partial Convolution (PConv) [11] introduced a rule-based mask-updating mechanism, conditioning the convolution operation only on valid pixels and progressively filling holes from the boundary inwards. Subsequently, Gated Convolution [13] replaced PConv’s hard-coded rules with a learnable soft-gating mechanism, allowing the network to dynamically determine the importance of features for the reconstruction task, thereby offering greater flexibility.

While these methods improved the handling of irregular structures, another major challenge was the tendency of early models to produce perceptually unconvincing and blurry results. To address this issue of visual realism, researchers introduced Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [14], which enhance the realism of generated textures through adversarial training. Subsequent improvements led to a dual-discriminator strategy, where a global discriminator supervises overall structural consistency while a local discriminator ensures the clarity and fidelity of fine details [15].

Despite these advances, the inherently local receptive field of CNNs remains a critical bottleneck, making it difficult for them to effectively model long-range dependencies in an image, which is crucial for restoring large degraded areas. To mitigate this issue, Yu et al. introduced a contextual attention layer that explicitly “borrows” feature information from known background regions to fill missing patches [12]. Subsequent work, such as the Coherent Semantic Attention (CSA) layer, further improved the semantic consistency of the generated content by modeling feature relationships within the hole regions themselves [16].

To fundamentally address the locality problem of CNNs, researchers turned their attention to the Transformer architecture [3], whose core self-attention mechanism is inherently powerful at global dependency modeling. The Vision Transformer (ViT) can capture long-range interactions across the entire image, directly tackling the limited receptive field problem of CNNs [7]. However, the computational complexity of the standard self-attention mechanism, which grows quadratically with image spatial resolution, severely limits its application in high-resolution image restoration tasks [17].

Consequently, recent research has focused on designing efficient Transformer architectures, commonly adopting hybrid designs that combine the global modeling strengths of Transformers with the efficient local processing capabilities of CNNs. Among these, SwinIR, proposed by Liang et al. [5], computes self-attention within non-overlapping local windows and enables interaction through window shifting. Restormer, proposed by Zamir et al. [6], takes a different approach by introducing a Multi-Dconv Head Transposed Attention (MDTA) mechanism on the channel dimension, reducing complexity to linear. Similarly, Uformer, proposed by Wang et al. [18], constructs a U-shaped hierarchical Transformer architecture whose core LeWin (Locally enhanced Window) Transformer block also integrates convolutions to enhance local feature capture. These models have achieved excellent results in various restoration tasks, validating the immense potential of hybrid CNN-Transformer designs.

2.2. Prompt Learning for Visual Models

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) aims to adapt large-scale pre-trained models at a low computational cost, avoiding a full model fine-tuning. As a representative PEFT method, Prompt Learning was initially applied in the field of natural language processing. This approach keeps the weights of the pre-trained model fixed and guides the model to complete specific downstream tasks by learning a set of lightweight, task-specific “prompt” parameters.

This paradigm has been successfully extended to the visual domain. CoOp (Contextual Optimization), proposed by Zhou et al., is a pioneering work for vision–language models like CLIP. Instead of manually designing text prompts (e.g., “a photo of a class”), CoOp models the context words with learnable continuous vectors, which are optimized end-to-end for the downstream classification task [19]. Visual Prompt Tuning (VPT), proposed by Jia et al., applies this concept directly to Vision Transformers. VPT introduces a small number of learnable prompt tokens in the input space and prepends them to the sequence of image patch embeddings. These prompts are processed together with the image tokens by the fixed Transformer backbone, effectively steering the model’s behavior to adapt to new tasks with minimal additional parameters [20].

2.3. Prompt-Based All-in-One Restoration

The capabilities of general-purpose restoration backbones and the efficiency of prompt learning have converged in the development of “all-in-one” image restoration models. These models aim to handle a variety of image degradation tasks using a single, unified network. A representative work in this area is PromptIR, proposed by Potlapalli et al. [21]. PromptIR is designed as a blind image restoration framework capable of handling multiple degradations (such as noise, rain, and haze) without prior knowledge of the specific corruption type [21]. Its core innovation is a plug-in prompt block composed of two modules: a Prompt Generation Module (PGM) and a Prompt Interaction Module (PIM). The PGM receives features from the intermediate layers of the restoration network and dynamically generates a prompt specific to the degradation type. This generation process is accomplished by predicting a set of linear combination weights for a learnable basis of prompts. Subsequently, the PIM injects this generated prompt into the network’s decoder, guiding the restoration process to adapt to the identified specific degradation type [21].

Although existing works like PromptIR [21] have demonstrated the effectiveness of prompts in multi-task blind image restoration, they primarily focus on degradation-aware adaptation. The prompting mechanism in such methods is designed to identify the global degradation type (e.g., noise or haze) and configure the network accordingly. However, this differs from the core challenge in many image restoration tasks, where the degradation type is often known, and the real difficulty lies in generating semantically coherent and contextually appropriate content for the corrupted regions. Therefore, existing methods lack a mechanism for fine-grained guidance of the generated content. Developing a prompting framework that is content-adaptive, rather than merely degradation-type-adaptive, remains an important research topic.

3. Materials and Methods

To overcome the limitations of existing static restoration models in handling spatially variant degradations, we propose the Hybrid Convolutional Transformer with Dynamic Prompting (HCTDP) framework. The core idea of HCTDP is to dynamically adjust the restoration process to adapt to the local characteristics of the image. To this end, HCTDP employs a U-Net style hierarchical encoder–decoder backbone, a proven architecture that excels at multi-scale feature processing. On top of this, we integrate two primary innovations aimed at achieving content-aware restoration:

- A Spatially Aware Dynamic Prompt Head Attention (SADPHA) module, which generates content-relevant guidance by synthesizing adaptive prompts from a learnable knowledge base.

- A Gated Skip-Connection (GSC) module, which refines the feature maps transferred from the encoder to the decoder to ensure high-fidelity feature aggregation.

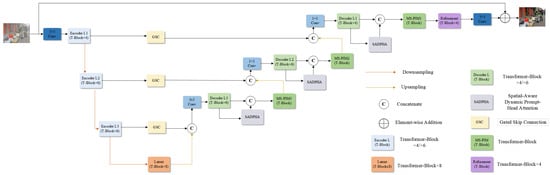

The overall architecture of our HCTDP network is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of our proposed HCTDP network. The model employs a hierarchical U-Net structure, which excels at capturing both global context and local details. The encoder path consists of three levels (L1, L2, and L3) and a latent bottleneck layer. The decoder path mirrors this structure, where each level utilizes an SADPHA module to generate adaptive prompts that are subsequently fused via a Prompt Interaction Module (PIM). Gated Skip-Connections (GSCs), implemented as ECA Attention, are used to refine the information flow between corresponding encoder and decoder levels.

3.1. Overall Network Architecture

The HCTDP framework adopts a hierarchical encoder–decoder architecture, leveraging its inherent ability to capture multi-scale contextual information while preserving high-resolution spatial details. Given a degraded image , it is first passed through an initial convolutional layer to produce the initial feature map .

The Encoder path is responsible for extracting abstract feature representations at multiple scales. It consists of three successive levels (L1, L2, and L3) and a bottleneck (Latent) level. Each level contains a series of Transformer Blocks (T-Blocks). As shown in Figure 1, the number of T-Blocks for levels L1, L2, L3, and Latent are 4, 6, 6, and 8, respectively, thereby allocating more computational capacity to deeper, more semantic layers. Between each level, a downsampling operation is applied to reduce the spatial resolution and progressively enlarge the receptive field.

The Decoder path aims to reconstruct a high-quality image from the learned representations. At each decoder level l, an upsampling operation first restores the spatial resolution of the feature maps from deeper levels. To provide the decoder with rich low-level texture and edge information that complements the high-level semantic features, the upsampled feature map is concatenated with the feature map from the corresponding level of the encoder. This encoder feature is first refined by our GSC module. The fused feature map is then processed by the T-Blocks of the current decoder level. Our key innovation, the SADPHA module, is applied at the end of each decoder stage to generate content-aware prompts. These prompts are then fused with the main feature stream via a dedicated Prompt Interaction Module (PIM, which is another T-Block), adaptively guiding the restoration process.

Finally, a refinement module and a final convolutional layer are used to reconstruct a residual image. This residual is added back to the original degraded input via a global residual connection to produce the final restored image .

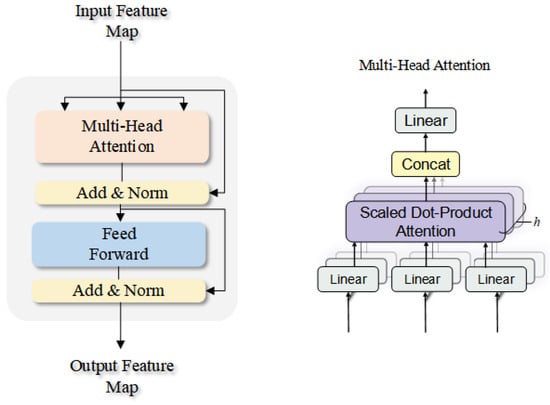

3.2. Transformer Block

The basic building block of our network is the Transformer Block (T-Block), illustrated in Figure 2. Each T-Block consists of two main sub-layers: a Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) module and a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN). We adopt a pre-normalization strategy, applying Layer Normalization (LN) before each sub-layer. Residual connections are used around both sub-layers to facilitate gradient flow.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the Transformer Block (adapted from [3]) (left) and the detailed structure of the Multi-Head Attention (MHA) mechanism (right).

- Pre-normalization: We apply Layer Normalization (LN) before each sub-layer. This approach is crucial for stabilizing the training of deep Transformers as it normalizes the input to each sub-layer, ensuring a consistent distribution of activations and mitigating the risk of vanishing or exploding gradients as data propagates through the deep network.

- Residual Connections: We use residual connections around both sub-layers. During backpropagation, this creates an additive identity path in the chain rule, allowing the gradient to flow directly across the connection. This “shortcut” ensures that the gradient signal can travel unimpeded to earlier layers, which is essential for effectively training deep architectures.

The MHSA module, with its ability to model long-range dependencies, computes scaled dot-product attention:

where Q, K, and V are the query, key, and value matrices, respectively. The FFN then processes these aggregated features, introducing non-linearity and transforming the feature representation for subsequent layers.

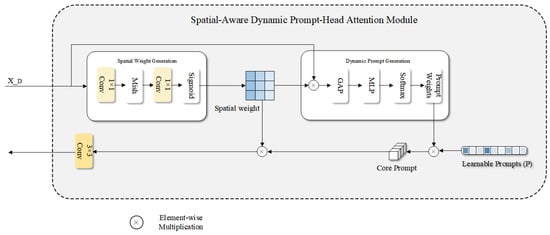

3.3. Spatially Aware Dynamic Prompt Head Attention (SADPHA)

Traditional restoration models often apply static, spatially invariant operators, which are ill suited for handling real-world degradations that are typically non-uniform. To address this, we propose the SADPHA module, detailed in Figure 3, which introduces a dynamic, content-aware restoration mechanism. This module first analyzes the input features via a spatial weight map to perceive and locate degraded regions that require focused restoration. It then dynamically generates a set of weights based on the features of these key regions to “modulate” a learnable knowledge base of restoration prompts, thereby tailoring a unique core restoration solution for the current image. Finally, this customized restoration solution is precisely and differentially applied to different locations of the image under the guidance of the initial spatial weights, ensuring that the restoration intensity matches the local degradation level for fine-grained adaptive restoration. This process is divided into two main steps: prompt generation and prompt interaction.

Figure 3.

Detailed structure of the Spatially Aware Dynamic Prompt Head Attention (SADPHA) module. It generates a spatially aware “core prompt” based on the input features.

Given an input feature map from a decoder stage, the SADPHA module first generates the prompt:

- Spatial Weight Generation: This branch first computes a spatial attention map to identify regions of interest that require more intensive restoration. It is generated via a compact two-layer convolutional network:where is the Sigmoid function. We employ the Mish activation function [22], known for its smooth, non-monotonic properties, which helps in preserving finer details in the attention map compared to standard ReLU.

- Dynamic Prompt Generation: This branch is responsible for synthesizing the “core prompt”. The network maintains a learnable prompt bank , which can be interpreted as a knowledge base containing various restoration priors or “experts”. The module learns to dynamically select and combine these experts by generating a set of of weights :where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. The final “core prompt” is synthesized as a dynamic linear combination of the experts in the bank:This core prompt is then broadcasted to the spatial dimensions of the feature map and further modulated by the spatial weight map to produce the final output prompt of the module, .

- Prompt Interaction: Simple modulation or addition of prompts can limit their ability to guide complex restoration processes. Therefore, the generated prompt is concatenated with the main feature map along the channel dimension. This combined feature map is then fed into a subsequent T-Block, which we term the Prompt Interaction Module (PIM). Crucially, since the PIM is itself a Transformer block, its self-attention mechanism can model complex, non-local interactions between the original feature content () and the synthesized guidance information (). This enables a deep, non-linear fusion, allowing the prompt to influence the restoration process globally and flexibly, rather than just acting as a simple local filter.

How Degraded Regions Are Identified: The identification process is a learned, data-driven behavior, not a predefined rule. The convolutional filters within the ‘Spatial Weight Generation’ branch are trained end-to-end to act as specialized feature detectors. Through training, they become sensitive to specific statistical anomalies that characterize degradation, such as the high-frequency patterns of noise, the linear directional signatures of rain streaks, or the local contrast reduction and color shifts caused by haze. The network then learns to map these detected, multi-channel patterns into a single-channel spatial weight map, . In this map, high values effectively highlight regions that the model has identified as requiring intensive restoration, based on the learned correlation between input patterns and successful ground-truth reconstruction.

Justification for Adaptivity: The adaptivity of the module is fundamental to its design, not merely a product of the Mish activation function. The spatial weight map is adaptive by definition because it is a direct computational output of the input features, formally expressed as . Since the deep feature representation is unique for every image, and the mapping function f (represented by the trained network branch) is deterministic, the resulting map is necessarily unique for each input. Therefore, the map is inherently adaptive, as it is generated in real-time and tailored to the specific spatial content and degradation patterns of each individual image.

Clarification of “Dynamic” Prompts: The term “dynamic” refers to how the final restoration prompt is created for each image. The network maintains a learnable prompt bank, , which can be conceptualized as a static “palette” of specialized restoration experts that are fixed after training. Our method is dynamic because, for each new image, it learns to dynamically “mix” these experts. This is achieved via two steps:

- Global Analysis and Weight Prediction: The network first performs a global analysis of the image’s features to predict a unique set of content-specific combination weights, .

- Prompt Synthesis: It then synthesizes a bespoke “core prompt,” , by calculating a weighted average of the static experts using these newly generated weights: .

This real-time synthesis, where a custom prompt is actively constructed based on the input’s specific needs, is the essence of our dynamic mechanism.

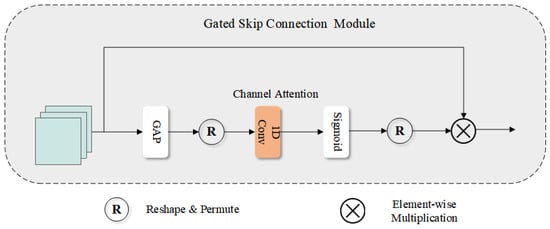

3.4. Gated Skip-Connection (GSC)

To prevent the propagation of noisy or irrelevant low-level features from the encoder, which could corrupt the high-fidelity reconstruction in the decoder, we introduce a Gated Skip-Connection (GSC) module. We implement the GSC using the Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) mechanism, as depicted in Figure 4. Unlike other channel attention methods that perform dimensionality reduction, which can cause information bottlenecks, ECA-Net [8] utilizes a fast 1D convolution to directly model local cross-channel interactions. This design choice enables a more efficient and effective recalibration of channel-wise feature responses.

Figure 4.

Structure of the Gated Skip-Connection (GSC) module, implemented via ECA-Net.

The GSC module generates channel-wise attention weights by applying Global Average Pooling (GAP) to the input, followed by a 1D convolution.

The refined feature map is then produced via element-wise multiplication:

This purified feature map is then passed to the decoder, ensuring that only the most salient and useful features are utilized for the reconstruction task.

Rationale for 1D Convolution: Our choice of a fast 1D convolution over a global linear layer is based on efficiency and effectiveness. A linear layer modeling interactions between C channels would require parameters, making it computationally expensive and prone to overfitting. In contrast, a 1D convolution with a small kernel size k requires only parameters. As , this is a far more efficient method for capturing the most important local cross-channel dependencies.

Rationale for Reshaping: The reshaping of data is a necessary operational step to utilize the 1D convolution. The input feature map is first reduced by Global Average Pooling to a ‘(1, 1, C)’ tensor. This tensor is then permuted or reshaped into a 1D sequence of shape ‘(1, C)’, which is the required input format for a Conv1D layer.

Justification for Avoiding an Information Bottleneck: An information bottleneck occurs when feature dimensionality is reduced, which can cause information loss. Our GSC module explicitly avoids this by design. Following ECA-Net [8], the 1D convolution operates directly on the full, C-dimensional channel space without any intermediate compression or dimensionality reduction step (unlike mechanisms such as SE-Net that use a C → C/r → C bottleneck). By preserving the dimensionality throughout the operation, no information bottleneck is created, ensuring a richer feature flow.

3.5. Hybrid Loss Function

Optimizing solely for pixel-level fidelity (e.g., using L1 or L2 loss) often leads to overly smooth results that lack perceptual realism. To address this, our network’s optimization is guided by a hybrid loss function that synergistically combines a pixel-level fidelity term and a feature-level perceptual term. Our network is guided by a hybrid loss function. The design is “hybrid” because it synergistically combines objectives from two distinct domains: the pixel-space (via L1 loss for structural fidelity) and the feature-space (via perceptual loss for visual realism). The novelty of our approach lies not in the loss function itself, but in its strategic use to guide our novel adaptive architecture (HCTDP) toward generating high-fidelity and perceptually rich results. The total loss is a weighted sum:

where is the L1 loss, is the perceptual loss [9], and and are hyperparameters that balance their contributions.

The L1 Loss, also known as Mean Absolute Error, measures the absolute difference between the restored image and the ground truth image . We specifically choose the L1 Loss for its theoretical advantages. The L2 loss penalizes larger errors quadratically, which mathematically encourages the model to find an average of possible solutions, often resulting in overly smooth or blurry outputs to minimize this high penalty. In contrast, the L1 loss is more robust to outliers (such as intense noise spikes or rain streaks) as it penalizes all errors linearly. This encourages the preservation of sharp edges and fine textures, leading to visually sharper and more plausible results.

The perceptual loss promotes visual realism by reducing the discrepancy between high-level feature representations. For this purpose, we employ a pre-trained VGG-19 network [23] as a feature extractor, with its parameters frozen during training. The loss is formulated by calculating the L1 norm of the difference between feature maps from the restored and ground-truth images. These features are sourced from various layers within the VGG network to encapsulate information at multiple scales.

where is the feature map from the j-th VGG layer (typically spanning relu1_2 to relu5_2), and is the weighting factor for that layer. By imposing a penalty on deviations in the feature domain, this loss facilitates the reconstruction of authentic textures and the conservation of semantic integrity, producing outputs more attuned to human visual perception.

3.6. Pseudo-Code for Proposed Modules

To enhance reproducibility, we provide pseudo-code for our core modules. Algorithm 1 outlines the process for the SADPHA module, and Algorithm 2 details the GSC module.

| Algorithm 1 Spatially Aware Dynamic Prompt Head Attention (SADPHA) |

Require: Input decoder feature map , learnable prompt bank Ensure: Fused feature map 1: ▹ Generate spatial weight map 2: ▹ Apply spatial weights to features 3: 4: ▹ Predict dynamic combination weights 5: ▹ Synthesize dynamic core prompt 6: ▹ Create spatially variant prompt 7: 8: ▹ Fuse via a T-Block 9: return |

| Algorithm 2 Gated Skip-Connection (GSC) |

Require: Input encoder feature map Ensure: Re-calibrated feature map 1: ▹ Squeeze spatial dimensions 2: ▹ Format for 1D convolution 3: ▹ Generate channel weights vector 4: ▹ Reshape weights for broadcasting 5: ▹ Re-calibrate feature map 6: return |

4. Experiments and Results

To rigorously assess the capabilities of our proposed HCTDP model, we performed a wide range of experiments targeting key image restoration challenges, such as deraining, denoising, and dehazing. This section outlines the experimental protocol, compares our model’s quantitative and qualitative results against state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches, and uses ablation studies to verify the utility of its core components.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Training and Evaluation Datasets

For training and evaluation, we utilized multiple established public datasets.

- Image Deraining: We used the Rain13K [24] dataset for training and the Rain100L [24] dataset for testing. These datasets contain a variety of synthetic rainy images and their corresponding clean ground truths.

- Image Denoising: For the denoising task, training was performed on the SIDD [25] dataset, and evaluation was conducted on the BSD400 [26] dataset.

- fImage Dehazing: We used the OTS [27] dataset for training and the SOTS [28] dataset for testing, which include synthetic hazy images of both indoor and outdoor scenes.

4.1.2. Performance Metrics

To quantify the quality of the restored images, we utilized two prevalent full-reference image assessment metrics:

- Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): PSNR serves as a standard metric for evaluating the fidelity of an image at the pixel level. An increased PSNR value corresponds to a reduced pixel-level discrepancy between the output and ground truth images, which denotes superior fidelity.

- Structural Similarity Index (SSIM): SSIM measures the similarity between images from three aspects: luminance, contrast, and structure, which is more consistent with human visual perception. SSIM scores fall within the range of −1 to 1; values approaching 1 signify a higher degree of structural resemblance.

4.1.3. Training Details

We implemented our model in the PyTorch(v1.10.1) framework, conducting the training process on a system equipped with two NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs. We used the AdamW optimizer [29] with an initial learning rate of that was dynamically modulated via a cosine annealing scheduler [30]. The training process utilized input image patches of size , organized into batches of 32. The model was trained for a total of 150 epochs. For the weights in the hybrid loss function, we empirically set and . All comparative experiments were conducted under the same hardware and software environment to ensure a fair comparison.These weights were determined empirically through a series of experiments on a validation set, aiming to find an optimal balance that leverages L1 loss for structural fidelity while incorporating perceptual loss to enhance textural details without introducing artifacts.

4.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

To validate the superiority of our HCTDP model, we compared it with several leading image restoration methods, including the CNN-based MPRNet [31], and the Transformer-based SwinIR [5] and PromptIR [21]. We evaluated all methods on multiple benchmark test sets.

4.2.1. Quantitative Comparison

Table 1 shows the quantitative comparison results across multiple restoration tasks. As can be seen from the table, our HCTDP model surpasses all other compared methods in terms of PSNR and SSIM metrics for deraining, dehazing, and denoising tasks. Particularly in the dehazing (SOTS) task, our method achieves a 0.96 dB PSNR improvement over the second-best method, MPRNet [31], which significantly demonstrates our model’s capability in handling complex degradation patterns. This is primarily attributed to the adaptive content-aware capability provided by the SADPHA module, which can distinguish between severely degraded regions (e.g., dense fog and heavy rain streaks) and lightly or non-degraded regions (e.g., clear foreground objects and smooth sky). Based on this identification, the model can apply strong restoration to heavily degraded areas while performing fine-grained, detail-preserving adjustments or no processing at all on other areas. This tailored restoration strategy avoids two common problems in traditional models: insufficient restoration in heavily affected areas, leading to residual artifacts, and excessive restoration in clear areas, causing loss of texture details and color distortion. It is this fine-grained spatial adaptability that allows HCTDP to effectively remove degradation while maximizing the preservation of the original image’s fidelity, thus achieving superior performance on objective metrics like PSNR and SSIM. Furthermore, as shown in Table 2, our HCTDP model has approximately 27 M parameters, while the second-best performing model, PromptIR, has 32.1 M parameters. Our HCTDP model not only achieves better performance with fewer parameters than PromptIR, but also demonstrates superior computational efficiency. This indicates an excellent trade-off between performance and efficiency, making our model a more compelling solution for practical applications.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison on multiple restoration tasks on benchmark datasets. The best results are in bold, and the second-best are in italics. The ↑ symbol indicates that higher values are better.

Table 2.

Comparison of model parameters and computational complexity. FLOPs are calculated for a 128 × 128 input. ‘↓’ indicates that lower is better.

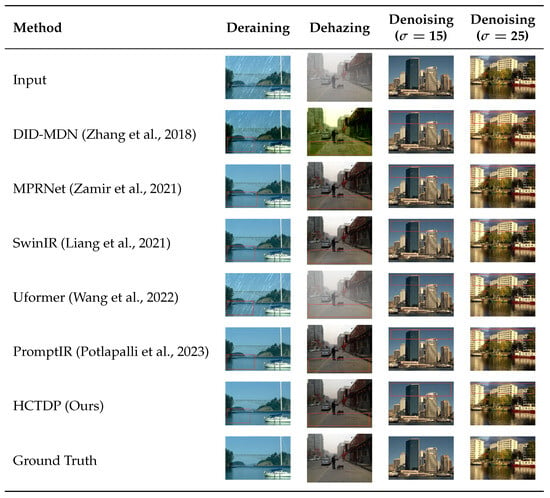

4.2.2. Qualitative Comparison

In addition to quantitative metrics, we provide visual comparisons for various restoration tasks in Figure 5 to intuitively demonstrate the performance.

Figure 5.

Qualitative comparison on various restoration tasks. For each task, we show the results of different methods. Our HCTDP model consistently produces visually superior results with better detail preservation and fewer artifacts.Red boxes highlight the selected regions for detailed comparison [5,18,21,31,32].

In the deraining task, it is evident that images processed by methods like DID-MDN [32] and Uformer [18] still have a significant amount of visible rain streaks, and the overall images are blurry, failing to effectively remove the “rain curtain effect”. Although MPRNet [31] and SwinIR [5] show improvement, streak artifacts or over-smoothing issues are still visible in the detailed area under the bridge. In contrast, our HCTDP model not only completely removes all rain streaks but also accurately restores the scene’s inherent structure and contrast, yielding the clearest and most natural results. We attribute this success to two key designs: first, the core capability of the SADPHA module to handle non-uniformly distributed degradation. The distribution of rain streaks is inherently sparse and random; SADPHA can precisely locate these rainy regions and generate localized restoration prompts, guiding the network to apply strong, targeted restoration, while performing protective detail recovery in rain-free areas. Second, the GSC module plays a crucial supporting role by purifying skip-connection features, preventing the original rain streak noise from directly contaminating high-level semantics. This provides a “cleaner” context for SADPHA’s precise restoration, further enhancing the clarity and fidelity of the final result.

In the dehazing task, it is clear that the result from Uformer [18] still has noticeable haze residue, leading to low overall image contrast. DID-MDN [32] shows significant color deviation, and SwinIR also fails to correctly handle some light haze. In comparison, the image restored by our method is much clearer and more transparent. This powerfully demonstrates another advantage of the SADPHA module: its ability to accurately identify the non-uniform distribution of haze concentration with varying scene depth and generate spatially variant dynamic prompts, thereby guiding the restoration process to perform more targeted, intensity-variable dehazing operations to completely remove residual haze.

Similarly, in the denoising task, methods like MPRNet [31] exhibit a tendency for over-smoothing, erasing a significant amount of fine textures. Our HCTDP model, however, effectively suppresses noise while preserving these high-frequency details intact. This is mainly due to the content-aware capability of the SADPHA module, which can distinguish between flat and texture-rich regions in an image, applying stronger smoothing to the former and protective restoration to the latter, thus avoiding the detail loss caused by a “one-size-fits-all” approach.

4.3. Ablation Study

To validate the effectiveness of the innovative components in our model, we conducted a series of ablation studies. We started with a basic Transformer U-Net as the baseline, which does not include the SADPHA and GSC modules. We then progressively integrated our Gated Skip-Connection (GSC) module and the Spatially Aware Dynamic Prompt Head Attention (SADPHA) module, finally evaluating the full HCTDP model with both modules. The performance was evaluated on the Rain100L [24] test set.

The ablation study results, shown in Table 3, reveal the crucial roles of the key components in our model. The baseline model, with both GSC and SADPHA modules removed, achieves a PSNR of 36.20 dB. When the GSC module is introduced alone, the model’s performance improves to 36.36 dB, a gain of 0.16 dB over the baseline. This initially indicates that effectively filtering features in the skip connections can remove some of the interference information introduced by rain streaks, thereby providing cleaner features to the decoder.

Table 3.

Ablation study results for the key components of our model on the Rain100L dataset.

In contrast, integrating the SADPHA module alone brings a significant PSNR improvement of 0.60 dB, pushing the performance to 36.80 dB. This result strongly demonstrates that SADPHA is the core driver of our model’s performance improvement, and its spatially adaptive and content-aware restoration capabilities are key to achieving efficient deraining.

Finally, when both modules work in synergy, our full HCTDP model achieves the best performance with a PSNR of 36.91 dB and an SSIM of 0.9752, a total improvement of 0.71 dB over the baseline. The full model not only surpasses the baseline but also outperforms any variant with a single component. Notably, the addition of GSC on top of SADPHA still provides a stable improvement of 0.11 dB (36.91 dB vs. 36.80 dB). While the incremental gains might seem modest, it is crucial to note that they are achieved upon a very strong Transformer-based baseline. In the mature and highly competitive field of image restoration, a PSNR improvement of 0.71 dB on a standard benchmark like Rain100L is considered a significant achievement. This clearly reveals a positive synergistic effect between the two modules: the GSC module provides higher quality, cleaner inputs for SADPHA’s adaptive restoration by purifying encoder features, while SADPHA, in turn, can more accurately exert its restoration capabilities. The two components complement each other, jointly contributing to the model’s optimal performance.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed the HCTDP framework, a Hybrid Convolutional Transformer with Dynamic Prompting for adaptive image restoration. This framework effectively addresses the limitations of static models in handling spatially variant degradations through synergistic innovations in architectural design and optimization objectives. At the architectural level, we introduced two core modules: SADPHA and GSC. SADPHA provides a new paradigm for fine-grained restoration through a content-adaptive Dynamic Prompting mechanism, while GSC effectively ensures the purity of the feature flow in the U-Net architecture. Our ablation studies have fully validated the independent effectiveness and synergistic interaction of these two architectural components. At the optimization level, we adopted a hybrid function combining L1 loss and perceptual loss, a strategy that has been proven crucial for enhancing the visual realism of the restoration results.

Experimental results demonstrate that through the synergistic design of architecture and optimization, HCTDP achieves SOTA performance on multiple benchmarks, including deraining, denoising, and dehazing. However, we acknowledge several avenues for future work. While our model demonstrates strong performance on synthetic datasets, a crucial next step is to evaluate its robustness on real-world degraded images to further validate its practical applicability. To enhance the rigor of our validation, future work will also incorporate non-parametric statistical tests to formally verify the significance of performance improvements. Furthermore, exploring comparisons with alternative paradigms, such as Bayesian methods like Information Field Theory, could provide valuable insights and represents an interesting avenue for future investigation. As the field of image restoration continues to evolve rapidly, we also plan to continuously benchmark HCTDP against emerging state-of-the-art models. Future research may also include applying our adaptive prompting mechanism to other low-level vision tasks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and G.C.; methodology, J.Z. and J.Y.; investigation, Q.Z.; formal analysis, S.L.; data curation, W.Z.; resources, J.Y. and G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chongqing Technology Innovation and Application Development Project, grant number 2023TIAD-GPX0007.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available. We used the Rain13K [24] and Rain100L [24] datasets for the image deraining task, the SIDD [25] and BSD400 [26] datasets for the image denoising task, and the OTS [27] and SOTS [28] datasets for the image dehazing task.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fu, X.; Huang, J.; Zeng, D.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X.; Paisley, J. Removing Rain from Single Images via a Deep Detail Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3855–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhang, L. Beyond a Gaussian Denoiser: Residual Learning of Deep CNN for Image Denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 3142–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Chu, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Simple baselines for image restoration. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image restoration using swin transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H. Restormer: Efficient transformer for high-resolution image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 5728–5739. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 694–711. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Reda, F.A.; Shih, K.J.; Wang, T.C.; Tao, A.; Catanzaro, B. Image inpainting for irregular holes using partial convolutions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, J.; Shen, X.; Lu, X.; Huang, T.S. Generative image inpainting with contextual attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 5505–5514. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, J.; Shen, X.; Lu, X.; Huang, T.S. Free-form image inpainting with gated convolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 4471–4480. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the NIPS’14: 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka, S.; Simo-Serra, E.; Ishikawa, H. Globally and locally consistent image completion. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 30 July–3 August 2017. Article No. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, C. Coherent semantic attention for image inpainting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 4170–4179. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z.; Talebi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P.; Bovik, A.; Li, Y. Maxim: Multi-axis MLP for image processing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 10784–10795. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cun, X.; Bao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Uformer: A general u-shaped transformer for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 17663–17673. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Loy, C.C.; Liu, Z. Learning to prompt for vision-language models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Tang, L.; Chen, B.C.; Cardie, C.; Belongie, S.; Hariharan, B.; Lim, S.N. Visual prompt tuning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 709–727. [Google Scholar]

- Potlapalli, V.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. PromptIR: Prompting for all-in-one blind image restoration. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, D. Mish: A self regularized non-monotonic neural activation function. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08681. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Huang, J.; Zeng, D.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Ding, X. Deep joint rain detection and removal from a single image. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1357–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamed, A.; Bruna, A.; Timofte, R. SIDD: A smartphone image denoising dataset. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 820–829. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Fowlkes, C.; Tal, D.; Malik, J. A database of human segmented natural images and its application to evaluating segmentation algorithms and measuring ecological statistics. In Proceedings of the Eighth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2001), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–14 July 2001; Volume 2, pp. 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Ren, W.; Fu, D.; Tao, D.; Feng, D.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Z. Benchmarking single image dehazing and beyond. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 28, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, D. AOD-Net: All-in-one dehazing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4770–4778. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; He, Y.; Yang, M.H. Multi-stage progressive image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14991–15001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Patel, V.M. Density-aware single image de-raining using a multi-stream dense network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).