Deep-DSO: Improving Mapping of Direct Sparse Odometry Using CNN-Based Single-Image Depth Estimation

Abstract

1. Introduction

Related Works

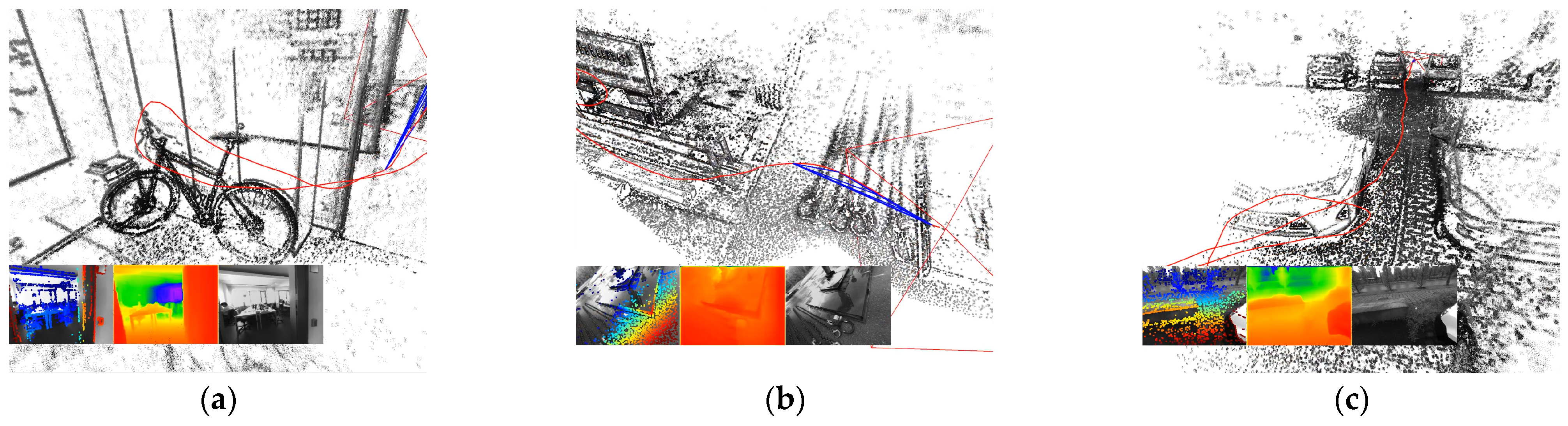

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review of the DSO Algorithm

2.2. Review of NeW CRF Single-Image Depth Estimation

2.3. An Improved Point-Depth Initialization for the DSO Algorithm

3. Results

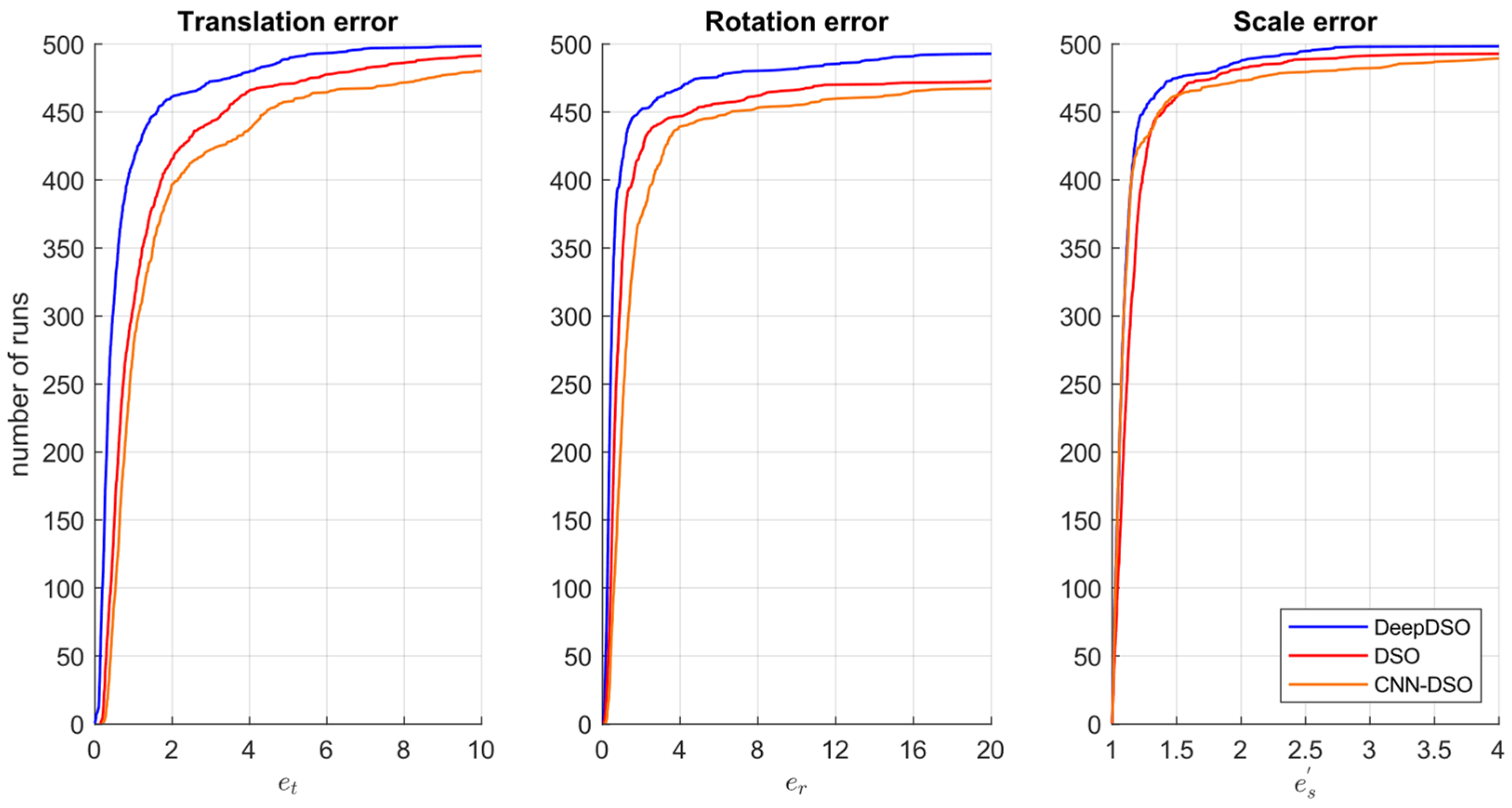

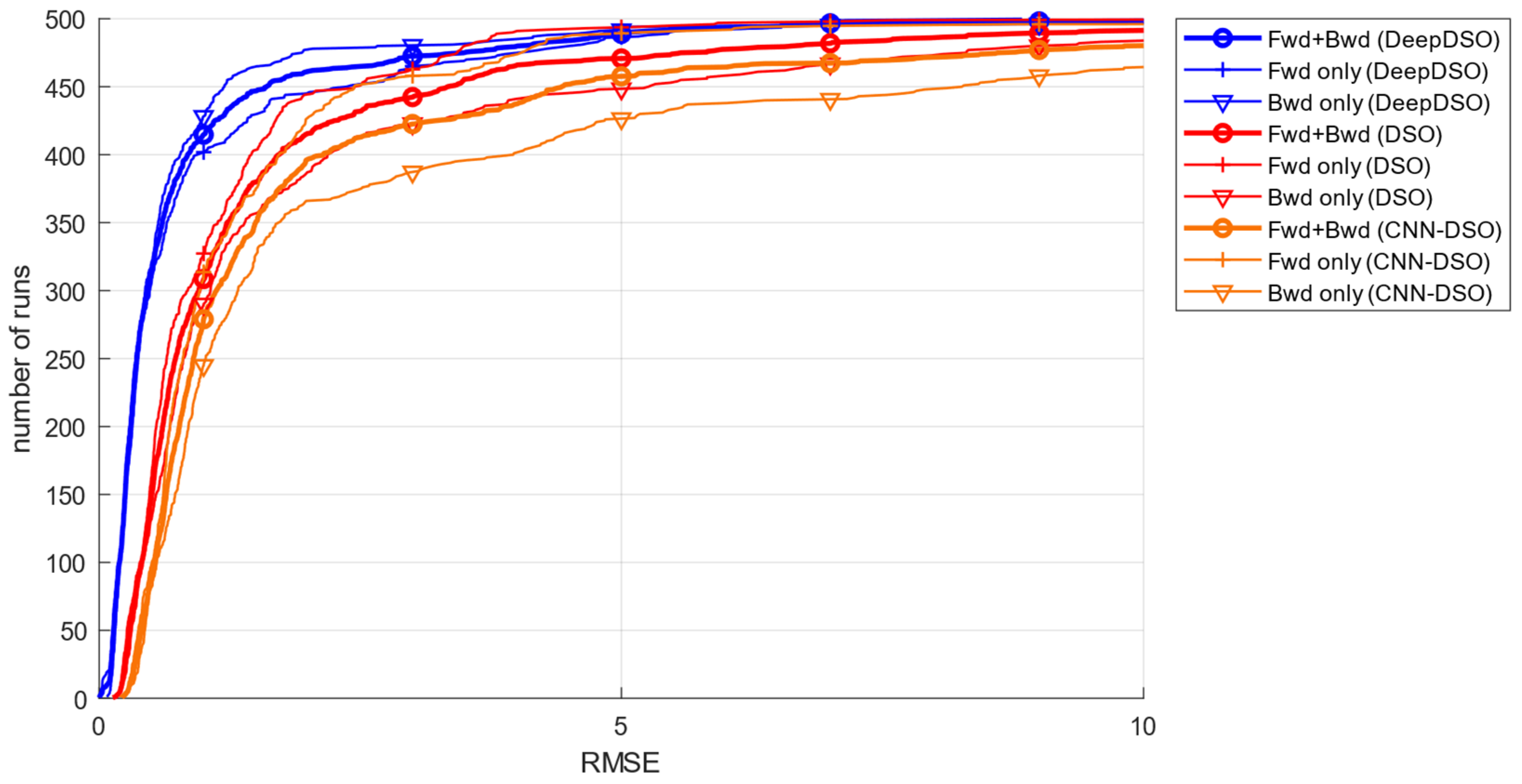

- Start and end segment alignment error. Each experimental trajectory was aligned with ground truth segments at both the start (first 10–20 s) and end (last 10–20 s) of each sequence, computing relative transformations through optimization:

- Translation, rotation and scale error: From these alignments, the accumulated drift was computed as enabling the extraction of translation, rotation and scale error components across the complete trajectory.

- Translational RMSE: The TUM-Mono benchmark authors also established a metric that equally considers translational, rotational, and scale effects. This metric, named alignment error (), can be computed for the start and end segments. Furthermore, when calculated for the combined start and end segments, is equivalent to the translational RMSE:where are the estimated tracked positions for the to frames, and are the frame indices corresponding to the start- and end-segments for the ground truth positions . As can be seen, the TUM-Mono benchmark is ideal for monocular comparisons, particularly for sparse-direct systems. This is because the benchmark was entirely acquired using monocular cameras and the ground truth was registered by a monocular SLAM system. Additionally, it enables the comparison of SLAM and VO systems from multiple dimensions, both separately and in conjunction. For this reason, we used this benchmark to test the performance of our DeepDSO proposal.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aqel, M.O.A.; Marhaban, M.H.; Saripan, M.I.; Ismail, N.B. Review of visual odometry: Types, approaches, challenges, and applications. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario Barros, A.; Michel, M.; Moline, Y.; Corre, G.; Carrel, F. A Comprehensive Survey of Visual SLAM Algorithms. Robotics 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servières, M.; Renaudin, V.; Dupuis, A.; Antigny, N. Visual and Visual-Inertial SLAM: State of the Art, Classification, and Experimental Benchmarking. J. Sens. 2021, 2021, 2054828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollhöfer, M.; Thies, J.; Garrido, P.; Bradley, D.; Beeler, T.; Pérez, P.; Stamminger, M.; Nießner, M.; Theobalt, C. State of the Art on Monocular 3D Face Reconstruction, Tracking, and Applications. Comput. Graph. Forum 2018, 37, 523–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Granda, E.P.; Torres-Cantero, J.C.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.H. Monocular visual SLAM, visual odometry, and structure from motion methods applied to 3D reconstruction: A comprehensive survey. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq Bhat, S.; Alhashim, I.; Wonka, P. AdaBins: Depth Estimation Using Adaptive Bins. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 4008–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranftl, R.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Koltun, V. Vision Transformers for Dense Prediction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.13413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messikommer, N.; Cioffi, G.; Gehrig, M.; Scaramuzza, D. Reinforcement Learning Meets Visual Odometry. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.15626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, D.D.; Geng, Z.Y. Visual Odometry Algorithm Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Image, Vision and Computing (ICIVC), Qingdao, China, 23–25 July 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Favaro, P.; Soatto, S. Real-time 3D motion and structure of point features: A front-end system for vision-based control and interaction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. CVPR 2000 (Cat. No.PR00662), Hilton Head, SC, USA, 15 June 2000; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.J.; Reid, I.D.; Molton, N.D.; Stasse, O. MonoSLAM: Real-Time Single Camera SLAM. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, R. PTAM-GPL: Parallel Tracking and Mapping. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/Oxford-PTAM/PTAM-GPL (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodriguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM3: An Accurate Open-Source Library for Visual, Visual–Inertial, and Multimap SLAM. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgaerts, L.; Bruhn, A.; Mainberger, M.; Weickert, J. Dense versus Sparse Approaches for Estimating the Fundamental Matrix. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2011, 96, 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranftl, R.; Vineet, V.; Chen, Q.; Koltun, V. Dense Monocular Depth Estimation in Complex Dynamic Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 4058–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stühmer, J.; Gumhold, S.; Cremers, D. Real-Time Dense Geometry from a Handheld Camera. In Joint Pattern Recognition Symposium; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 6376, pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzoli, M.; Forster, C.; Scaramuzza, D. REMODE: Probabilistic, monocular dense reconstruction in real time. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 2609–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Schöps, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large-Scale Direct Monocular SLAM. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Zurich, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8690 LNCS, No. Part 2; pp. 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Koltun, V.; Cremers, D. Direct Sparse Odometry. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, R.; Demmel, N.; Cremers, D. LDSO: Direct Sparse Odometry with Loop Closure. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 2198–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta, J.; Aguinaga, I.; Montiel, J.M.M. Direct Sparse Mapping. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–5 June 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bescos, B.; Facil, J.M.; Civera, J.; Neira, J. DynaSLAM: Tracking, Mapping, and Inpainting in Dynamic Scenes. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 4076–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbeek, A. Sparse-to-Dense: Depth Prediction from Sparse Depth Samples and a Single Image. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/annesteenbeek/sparse-to-dense-ros (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Sun, L.; Yin, W.; Xie, E.; Li, Z.; Sun, C.; Shen, C. Improving Monocular Visual Odometry Using Learned Depth. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 3173–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummenhofer, B.; Zhou, H.; Uhrig, J.; Mayer, N.; Ilg, E.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Brox, T. DeMoN: Depth and Motion Network for Learning Monocular Stereo. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–21 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 5622–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teed, Z.; Deng, J. DeepV2D: Video to Depth with Differentiable Structure from Motion. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.04605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Z.; Dunn, E. VOLDOR-SLAM: For the Times When Feature-Based or Direct Methods Are Not Good Enough. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.06800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teed, Z.; Deng, J. DROID-SLAM: Deep Visual SLAM for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 16558–16569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; Mei, K. SDF-SLAM: A Deep Learning Based Highly Accurate SLAM Using Monocular Camera Aiming at Indoor Map Reconstruction with Semantic and Depth Fusion. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10259–10272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, K.; Tombari, F.; Laina, I.; Navab, N. CNN-SLAM: Real-Time Dense Monocular SLAM with Learned Depth Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 6565–6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlow, T.; Czarnowski, J.; Leutenegger, S. DeepFusion: Real-Time Dense 3D Reconstruction for Monocular SLAM Using Single-View Depth and Gradient Predictions. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 4068–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloesch, M.; Czarnowski, J.; Clark, R.; Leutenegger, S.; Davison, A.J. CodeSLAM—Learning a Compact, Optimisable Representation for Dense Visual SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 2560–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnowski, J.; Laidlow, T.; Clark, R.; Davison, A.J. DeepFactors: Real-Time Probabilistic Dense Monocular SLAM. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Agia, C.; Meger, D.; Dudek, G. Depth Prediction for Monocular Direct Visual Odometry. In Proceedings of the 2020 17th Conference on Computer and Robot Vision (CRV), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 13–15 May 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; von Stumberg, L.; Wang, R.; Cremers, D. D3VO: Deep Depth, Deep Pose and Deep Uncertainty for Monocular Visual Odometry. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1278–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimbauer, F.; Yang, N.; von Stumberg, L.; Zeller, N.; Cremers, D. MonoRec: Semi-Supervised Dense Reconstruction in Dynamic Environments from a Single Moving Camera. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 15–20 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 6108–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Tang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Vasilakos, A.V. Deep Direct Visual Odometry. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 7733–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, S.Y.; Amiri, A.J.; Mashohor, S.; Tang, S.H.; Zhang, H. CNN-SVO: Improving the Mapping in Semi-Direct Visual Odometry Using Single-Image Depth Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 5218–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Granda, E.P.; Torres-Cantero, J.C.; Rosales, A.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.H. A Comparison of Monocular Visual SLAM and Visual Odometry Methods Applied to 3D Reconstruction. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Usenko, V.; Cremers, D. A Photometrically Calibrated Benchmark for Monocular Visual Odometry. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.02555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. DVSO: Deep Virtual Stereo Odometry. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/SenZHANG-GitHub/dvso (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cheng, R. CNN-DVO. McGill University. 2020. Available online: https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/downloads/6t053m97w (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Muskie. CNN-DSO: A Combination of Direct Sparse Odometry and CNN Depth Prediction. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/muskie82/CNN-DSO (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Godard, C.; Mac Aodha, O.; Brostow, G.J. Unsupervised Monocular Depth Estimation with Left–Right Consistency. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 6602–6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Granda, E.P. Real-Time Monocular 3D Reconstruction of Scenarios Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10481/90846 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Wang, S. DF-ORB-SLAM. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/834810269/DF-ORB-SLAM (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Zubizarreta, J. DSM: Direct Sparse Mapping. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/jzubizarreta/dsm (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Herrera-Granda, E.P.; Torres-Cantero, J.C.; Peluffo-Ordoñez, D.H. Monocular Visual SLAM, Visual Odometry, and Structure from Motion Methods Applied to 3D Reconstruction: A Comprehensive Survey. Heliyon-First Look 2023, 8, e37356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, J.; Sturm, J.; Cremers, D. Semi-dense Visual Odometry for a Monocular Camera. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Chung, S.H.; Ng, A.Y. Learning Depth from Single Monocular Images. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’05), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–8 December 2005; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 1161–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Aich, S.; Uwabeza Vianney, J.M.; Islam, M.A.; Liu, M.K.B. Bidirectional Attention Network for Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 11746–11752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigen, D.; Puhrsch, C.; Fergus, R. Depth Map Prediction from a Single Image Using a Multi-Scale Deep Network. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.; Nguyen-Ha, P.; Matas, J.; Rahtu, E.; Heikkilä, J. Guiding Monocular Depth Estimation Using Depth-Attention Volume. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 581–597. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Han, M.-K.; Ko, D.W.; Suh, I.H. From Big to Small: Multi-Scale Local Planar Guidance for Monocular Depth Estimation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.10326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, B.; Yi, E.; Kim, J. Patch-Wise Attention Network for Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Liao, R.; Liu, Z.; Urtasun, R.; Jia, J. GeoNet: Geometric Neural Network for Joint Depth and Surface Normal Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, C.; Mac Aodha, O.; Firman, M.; Brostow, G. Digging into Self-Supervised Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 3827–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizilini, V.; Ambruş, R.; Burgard, W.; Gaidon, A. Sparse Auxiliary Networks for Unified Monocular Depth Prediction and Completion. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 11073–11083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, M.; Kretz, A.; Mester, R. SDNet: Semantically Guided Depth Estimation Network. In Pattern Recognition; Fink, G.A., Frintrop, S., Jiang, X., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 288–302. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Adam, H.; Yuille, A.; Chen, L.-C. ViP-DeepLab: Learning Visual Perception with Depth-aware Video Panoptic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 3996–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shen, C.; Dai, Y.; Hengel, A.V.D.; He, M. Depth and surface normal estimation from monocular images using regression on deep features and hierarchical CRFs. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Tian, H. Depth estimation with convolutional conditional random field network. Neurocomputing 2016, 214, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Gu, X.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, S.; Tan, P. Neural Window Fully-connected CRFs for Monocular Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 3906–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, S.Y. CNN-SVO. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/yan99033/CNN-SVO (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Civera, J.; Davison, A.J.; Montiel, J.M.M. Inverse Depth Parametrization for Monocular SLAM. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2008, 24, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J. DSO: Direct Sparse Odometry. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/JakobEngel/dso (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Lovegrove, S. Pangolin. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/stevenlovegrove/Pangolin/tree/v0.5 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Loo, S.-Y. MonoDepth-cpp. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/yan99033/monodepth-cpp (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The Cityscapes Dataset for Semantic Urban Scene Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, A.; Whelan, T.; McDonald, J.; Davison, A.J. A benchmark for RGB-D visual odometry, 3D reconstruction and SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Cheng, X.; Geng, Q.; Cao, B.; Zhou, D.; Wang, P.; Lin, Y.; Yang, R. The ApolloScape Dataset for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Urtasun, R. Are we ready for autonomous driving? The KITTI vision benchmark suite. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 3354–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, M.; Nikolic, J.; Gohl, P.; Schneider, T.; Rehder, J.; Omari, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Siegwart, R. The EuRoC micro aerial vehicle datasets. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016, 35, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.J.; Wulff, J.; Stanley, G.B.; Black, M.J. A Naturalistic Open Source Movie for Optical Flow Evaluation. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); Fitzgibbon, A., Lazebnik, S., Perona, P., Sato, Y., Schmid, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Part IV, LNCS 7577; pp. 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, A.R.; Sax, A.; Shen, W.; Guibas, L.; Malik, J.; Savarese, S. Taskonomy: Disentangling Task Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 3712–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Liu, Y.; Shen, C. Virtual Normal: Enforcing Geometric Constraints for Accurate and Robust Depth Prediction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 7282–7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Min, D.; Kim, Y.; Sohn, K. A Large RGB-D Dataset for Semi-supervised Monocular Depth Estimation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, K.; Chen, J.; Luo, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Monocular Relative Depth Perception with Web Stereo Data Supervision. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingachev, E.; Ivkin, P.; Zhukov, M.; Prokhorov, D.; Mavrin, A.; Ronzhin, A.; Rigoll, G.; Meshcheryakov, R. Comparison of ROS-Based Monocular Visual SLAM Methods: DSO, LDSO, ORB-SLAM2 and DynaSLAM. In Interactive Collaborative Robotics; Ronzhin, A., Rigoll, G., Meshcheryakov, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingachev, E.; Lavrenov, R.; Magid, E.; Svinin, M. Comparative Analysis of Monocular SLAM Algorithms Using TUM and EuRoC Benchmarks. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 187, pp. 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Granda, E.P. A Comparison of Monocular Visual SLAM and Visual Odometry Methods Applied to 3D Reconstruction. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/erickherreraresearch/MonocularPureVisualSLAMComparison (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Sturm, J.; Engelhard, N.; Endres, F.; Burgard, W.; Cremers, D. A benchmark for the evaluation of RGB-D SLAM systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vilamoura, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Liu, E.; Yan, K.; Ma, Y. Scale Estimation and Correction of the Monocular Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) Based on Fusion of 1D Laser Range Finder and Vision Data. Sensors 2018, 18, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucar, E.; Hayet, J.-B. Bayesian Scale Estimation for Monocular SLAM Based on Generic Object Detection for Correcting Scale Drift. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.02768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasdat, H.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Davison, A.J. Scale Drift-Aware Large Scale Monocular SLAM. In Robotics: Science and Systems VI (RSS); Robotics: Science and Systems Foundation: Zaragoza, Spain, 2010; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Arora, C. DepthFormer: Multiscale Vision Transformer for Monocular Depth Estimation with Local-Global Information Fusion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.04535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Arora, C. Attention Attention Everywhere: Monocular Depth Prediction with Skip Attention. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.09071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coefficient () | Translational RMSE † | Std. Dev. | Convergence Rate ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.4127 | 0.0856 | 73% |

| 3 | 0.3214 | 0.0523 | 87% |

| 4 | 0.2685 | 0.0347 | 94% |

| 5 | 0.2453 | 0.0218 | 98% |

| 6 | 0.2382 | 0.0163 | 100% |

| 7 | 0.2491 | 0.0197 | 100% |

| 8 | 0.2738 | 0.0284 | 100% |

| 9 | 0.3156 | 0.0412 | 100% |

| 10 | 0.3647 | 0.0569 | 100% |

| Component | Specifications |

|---|---|

| CPU | AMD Ryzen™ 7 3800X (TSMC made in Hsinchu, Taiwan). 8 cores, 16 threads, 3.9–4.5 GHz. |

| GPU | NVIDIA GEFORCE RTX 3060 (ASUS made in Hanoi, Vietnam). Ampere architecture, 1.78 GHz, 3584 CUDA cores, 12 GB GDDR6X. Memory interface width 192-bit. 2nd generation Ray Tracing Cores and 3rd generation Tensor cores. |

| RAM | 16 GB, DDR 4, 3200 MHz (Corsair made in Taoyuan, Taiwan). |

| ROM | SSD NVME M.2 Western Digital 7300 MB/s (Western Digital, Penang, Malasia). |

| Power consumption | 750 W 1 |

| Method | Translation Error | Rotation Error | Scale Error | Start-Segment Align. Error | End-Segment Align. Error | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal–Wallis general test | pval = 2.2 × 10−16 | pval = 2.2 × 10−16 | pval = 2.2 × 10−16 | pval = 2.2 × 10−16 | pval = 2.2 × 10−16 | pval = 2.2 × 10−16 |

| DeepDSO | 0.3250961 a | 0.3625576 a | 1.062872 a | 0.001659008 a | 0.002170299 a | 0.06243667 a |

| DSO | 0.6472075 b | 0.6144892 b | 1.100516 b | 0.003976057 b | 0.004218454 b | 0.19595997 b |

| CNN-DSO | 0.7978954 c | 0.9583970 c | 1.078830 c | 0.008847161 c | 0.006651353 c | 0.20758145 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrera-Granda, E.P.; Torres-Cantero, J.C.; Herrera-Granda, I.D.; Lucio-Naranjo, J.F.; Rosales, A.; Revelo-Fuelagán, J.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.H. Deep-DSO: Improving Mapping of Direct Sparse Odometry Using CNN-Based Single-Image Depth Estimation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203330

Herrera-Granda EP, Torres-Cantero JC, Herrera-Granda ID, Lucio-Naranjo JF, Rosales A, Revelo-Fuelagán J, Peluffo-Ordóñez DH. Deep-DSO: Improving Mapping of Direct Sparse Odometry Using CNN-Based Single-Image Depth Estimation. Mathematics. 2025; 13(20):3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203330

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrera-Granda, Erick P., Juan C. Torres-Cantero, Israel D. Herrera-Granda, José F. Lucio-Naranjo, Andrés Rosales, Javier Revelo-Fuelagán, and Diego H. Peluffo-Ordóñez. 2025. "Deep-DSO: Improving Mapping of Direct Sparse Odometry Using CNN-Based Single-Image Depth Estimation" Mathematics 13, no. 20: 3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203330

APA StyleHerrera-Granda, E. P., Torres-Cantero, J. C., Herrera-Granda, I. D., Lucio-Naranjo, J. F., Rosales, A., Revelo-Fuelagán, J., & Peluffo-Ordóñez, D. H. (2025). Deep-DSO: Improving Mapping of Direct Sparse Odometry Using CNN-Based Single-Image Depth Estimation. Mathematics, 13(20), 3330. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203330