Abstract

Operational satellites are critical to modern aerospace infrastructure, supporting essential services such as communication, navigation, and global surveillance. However, the increasing density of satellites and space debris in Earth’s orbit has heightened the risk of collisions, thereby threatening network reliability. This study addresses the dual challenge of managing space debris and enhancing satellite network performance by applying the concept of acyclic matching from graph theory to satellite constellations modeled as honeycomb networks. Acyclic matching identifies edge subsets without shared nodes or cycles, enabling static signal rerouting through pre-computed, loop-free paths. This ensures fault tolerance and efficient resource allocation in increasingly complex satellite constellations. The proposed method derives the general solution for acyclic matching cardinality and determines the maximum matching set for n-dimensional honeycomb networks. This technique aligns with emerging trends in autonomous fault-tolerant systems and adaptive routing protocols, proving particularly relevant for large-scale satellite systems such as Starlink and global navigation constellations. By providing alternative communication paths in the event of satellite or link failures, the approach significantly enhances the scalability, reliability, and resilience of satellite networks, ensuring uninterrupted service and improved space traffic management in the face of rising orbital congestion.

Keywords:

acyclic matching; aerospace technology; fault-tolerant communication; honeycomb network; satellite constellation MSC:

97K30; 68W25; 05C70 68M10

1. Introduction

Aerospace technology encompasses advanced engineering and innovation that enable the design, development, and deployment of aircraft, spacecraft, and associated systems. One of its most transformative applications is in satellite constellation networks of interconnected satellites working together to provide global coverage for communication, navigation, and Earth observation. These constellations leverage aerospace advancements in propulsion, miniaturization, and autonomous operation to deliver unprecedented capabilities. By combining cutting-edge aerospace technology with scalable satellite networks, these systems are reshaping industries, fostering global connectivity, and addressing critical challenges such as disaster management and climate monitoring. However, as satellite constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink and GPS expand, they face challenges related to reliability, fault tolerance, and operational resilience. Failures caused by environmental factors, hardware malfunctions, or collisions with space debris can disrupt communication, leading to degraded performance or service outages [1]. To maintain seamless operations under these conditions, innovative strategies like fault detection, efficient routing, and recovery mechanisms are required. Current satellite networks depend on large constellations of orbiting satellites to provide a variety of services. While redundancy has been the traditional approach to ensure fault tolerance, it leads to inefficiencies, high operational costs, and scalability challenges as constellations expand. Redundancy-based strategies also lack real-time adaptability, making them ill-suited for addressing unpredictable failures. Graph theory-based strategies, such as acyclic matching, provide a scalable mathematical approach to improve fault-tolerant signal routing and ensure network reliability through static loop-free paths.

Honeycomb networks are geometric structures characterized by interconnected hexagonal cells. The hexagonal arrangement allows for high bisection widths and reduced overall link costs compared to traditional mesh networks, making them suitable for multiprocessor interconnection systems [2]. These networks are celebrated for their combination of lightweight properties, structural stability, efficient load distribution and fault-tolerant properties, making them widely used in aerospace and satellite engineering. Honeycomb networks allow for even load distribution across multiple communication paths, ensuring stability and aerodynamic efficiency in satellite constellations. Their unique geometry provides redundancy by offering multiple pathways that can maintain signal integrity even under failure conditions. The properties of honeycomb networks make them particularly well-suited for analysis using graph theory methods. Their symmetrical and recursive nature aligns with mathematical strategies like acyclic matching to optimize communication pathways. The neural networks are widely applied in the field of aviation [3]. These networks are integral to modern aerospace designs, supporting advanced composite materials and fault recovery. Honeycomb networks allow signals to reroute seamlessly during failures, minimizing communication interruptions while maintaining operational efficiency. Routing and broadcasting algorithms for the honeycomb mesh networks have been described to find a path from a source to a destination and forward a message along the path [4]. Recently, research has concentrated on identifying dominating sets in honeycomb networks, which play a crucial role in ensuring secure communications [5] and exhibit certain coloring properties [6]. While these bipartite networks have been studied extensively for their mechanical properties [7,8], their integration in space networks with fault-tolerant communication strategies is an area of growing research [9,10].

Graph theory provides mathematical tools for analyzing complex communication networks [11,12], which have more applications in medical [13], chemical, and aeronautical fields, and even in satellite constellations. Honeycomb networks assist in designing optimal network topologies by determining efficient arrangements of nodes and links. This is essential for minimizing latency, maximizing throughput, and enhancing fault tolerance. In communication networks, graph theory aids in the design and analysis of routing algorithms, identifying critical nodes, and optimizing overall network performance [14,15]. One of the key concepts in graph theory is matching, defined as a subset of edges in a graph where no two edges share a common node. Various types of matching exist, including perfect matching, min–max matching, and acyclic matching [16]. Of these, acyclic matching is a specialized type of matching that imposes an additional constraint, the subgraph induced by the matched edges must be loop-free (acyclic), which was introduced by Noga et al. [17]. Subsequently, Panda and Pradhan [18] made a key contribution by demonstrating that the acyclic matching problem can be efficiently solved for certain bipartite graphs and particularly those classified as P4-free and 2P3-free. Other researchers further advanced the field by presenting an algorithm for finding maximal acyclic matching [19,20]. Building on this work, [21] explored the complexities of comb-convex and dually chordal graphs, proving that they cannot be solved in polynomial time. Juhi Chaudhary also made a notable contribution by creating a linear-time algorithm to compute a maximal acyclic matching with the minimal cardinality for proper interval graphs, and he recently derived an algorithm for min–max acyclic matching problems and vertex cover numbers [22,23]. Lately, acyclic matching numbers have been computed for various bipartite graphs and utilized in electrical networks to tackle unforeseen power outage emergencies [24]. Acyclic matching properties are also classified and applied in abelian groups in [25,26]. Ref. [27] developed a tree width algorithm using induced matching under the perspective of parameterized complexity, with which induced matching and acyclic matching were explained. Ref. [28] demonstrated that a maximum acyclic matching in a graph can be computed recursively with a recursion depth for unidirectional graphs.

Although research in acyclic matching has been steadily growing, its application to graph networks remains relatively unexplored. In particular, determining the cardinal value of acyclic matching has received limited attention in the literature. Moreover, generalizing such solutions for arbitrary n-dimensional graphs poses significant challenges due to the complexity of these structures. Acyclic matching is essential for fault-tolerant communication because it ensures stable signals and fault-free routing paths without delays caused by interference or loops. The properties of acyclic matching include maximizing the number of independent signal paths and ensuring that no signal loops form. This allows satellite networks to dynamically respond to faults by rerouting signals across independent, non-overlapping paths, ensuring uninterrupted communication. Graph theorists such as Lovász and Plummer have contributed foundational insights into matching and its optimization [29]. These principles now underpin modern fault-tolerant communication strategies.

Real-time fault detection and routing are critical for satellite reliability. Integrating honeycomb network topologies with acyclic matching algorithms enables fast, fault-free rerouting by computing loop-free paths during failures. Honeycomb networks provide a geometric foundation for redundancy and resilience, while acyclic matching offers computational algorithms for fault detection and rerouting. This integration allows satellite constellations to maintain efficient and reliable communications even under crucial environmental disruptions or failure conditions. Recent research highlights that the combination of mathematical and geometric strategies offers scalable, efficient, and adaptive fault detection and routing mechanisms, particularly for satellite constellations [30]. Despite their theoretical promise, these strategies remain underexplored in practical aerospace and satellite communication applications [31]. This motivates further research into computational algorithms, mathematical derivations, and real-world satellite designs that incorporate honeycomb networks and acyclic matching for improved reliability and fault recovery. This paper makes the following novel contributions to aerospace technology and graph theory applications. First, it explains existing fundamental properties needed to understand upcoming results. Second, it introduces two linear-time algorithms, AMCV and AMES, designed for computing maximum acyclic matching sets in honeycomb structures. Third, it derives a general solution for acyclic matching cardinality in n-dimensional honeycomb networks, proven as through a rigorous mathematical proof, based on induction and contradiction analysis. Finally, it presents the future practical application framework demonstrating how acyclic matching can enhance fault-tolerant communication in satellite constellations by preventing signal loops and enabling static rerouting. Collectively, these contributions bridge theoretical graph theory with practical aerospace engineering, offering scalable solutions to improve the reliability of next-generation satellite networks.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology, including formal definitions of acyclic matching and honeycomb networks. Section 3 details our main results, presenting two algorithms (AMCV for cardinal value computation and AMES for edge set determination) along with theoretical proofs. Section 4 discusses practical applications in satellite constellation fault tolerance with illustrative examples, along with its limitations and future work. Section 5 concludes the work.

2. Methodology

A matching is a collection of pairwise non-adjacent edges, such that each vertex is incident to at most one edge in the matching set. Formally, in a graph , a matching is a set of edges such that for any two edges , the vertices of and do not overlap [32]. A maximum matching is a matching that contains the largest possible number of edges. A matching is a perfect matching if every vertex of the graph is connected to exactly one edge in the matching.

2.1. Acyclic Matching

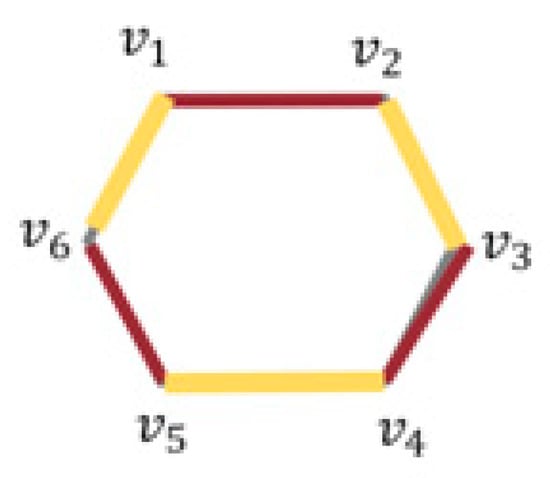

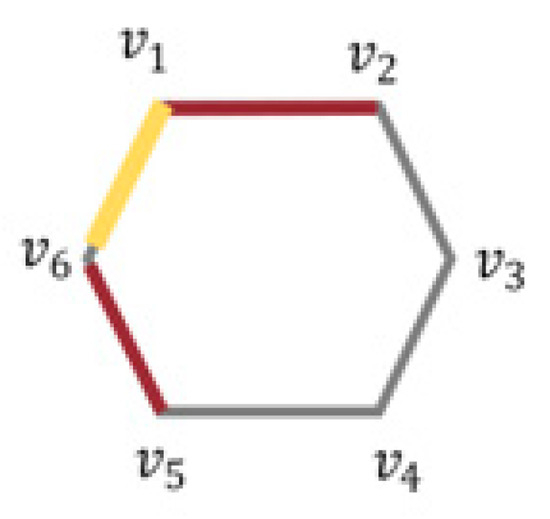

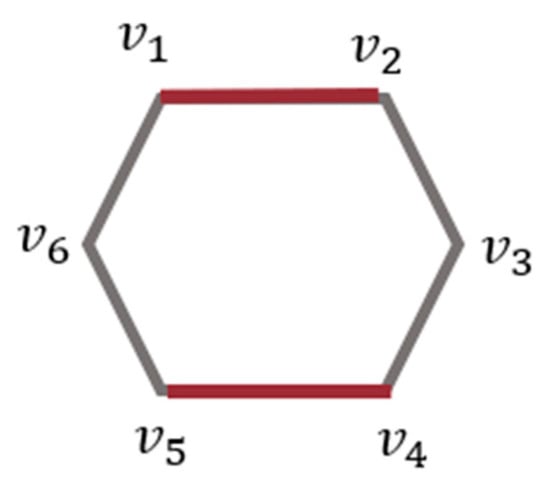

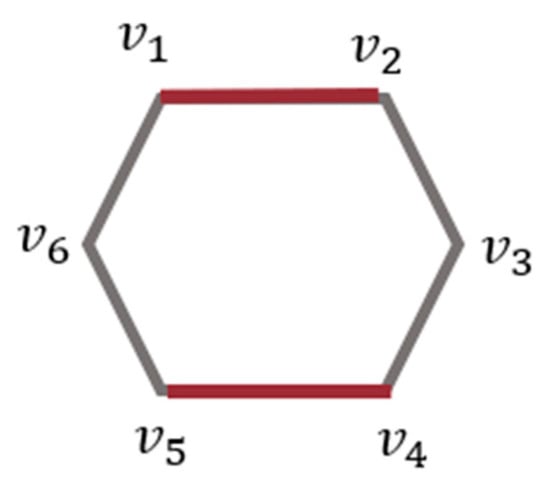

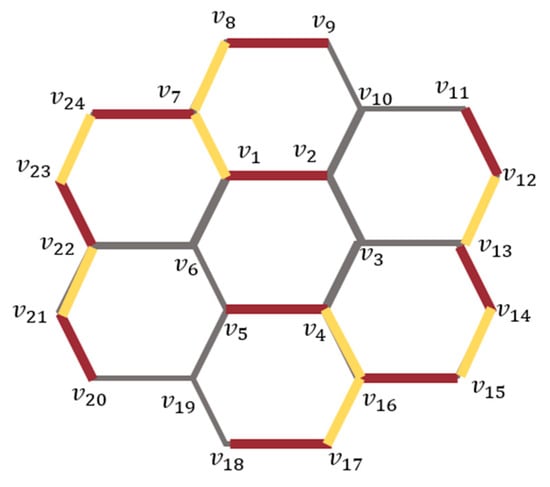

For the graph , a matching is said to be acyclic if the induced subgraph formed by vertices are acyclic (without any loops). Acyclic matching is the set of independent matching edges [33] which forms a path created by and has no cycles with length . Figure 1 depicts a matching set (red edges); the induced subgraph (yellow edges along with the red) forms a cycle, whereas the pathway of is acyclic in Figure 2. The cardinal value is denoted as . As depicted in Figure 2, acyclic matching eliminates closed loops, thereby guaranteeing uninterrupted and interference-free signal routing within satellite networks.

Figure 1.

Perfect matching.

Figure 2.

Acyclic matching.

2.2. Honeycomb Network

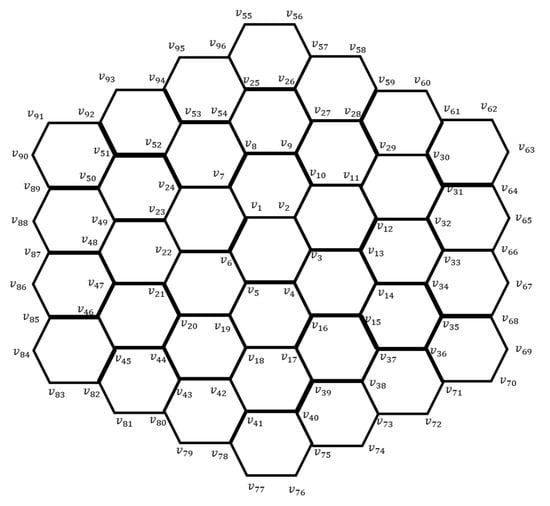

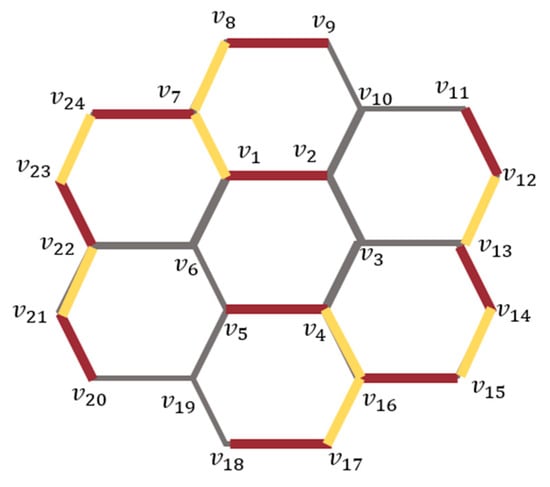

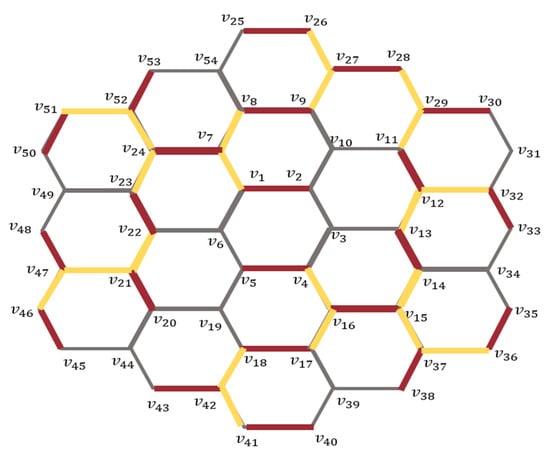

A highly interconnected system, honeycomb has a repeating modular structure much like hexagonal cells. The network is constructed by expanding the previous network by adding a layer of hexagons around the boundary of . Each new layer surrounds the existing structure, progressively increasing the overall size and complexity of the network, and it is determined as the number of hexagons between the centre and boundary of HC(n). The size of the network significantly grows as increases, with the number of vertices and edges given by 6n2 and 9n2 − 3n, respectively [34]. The honeycomb layout ensures efficient spatial reuse of frequencies and allows seamless coverage over a wide area. The given Figure 3 has six layers of hexagonal cells and holds 96 vertices interconnected to each other with the help of 132 edges. Recently, honeycomb structures have attracted a wide range of researchers as well as artists.

Figure 3.

.

2.3. Fundamental Properties

The set M is defined by three fundamental properties: maximality, independence of edges, and acyclicity. Maximality ensures that M contains the largest possible number of edges, without violating the independence or acyclicity conditions. The independence of edges guarantees that no two edges in M share a common vertex, meaning each vertex is incident to at most one edge in the matching. Finally, acyclicity requires that the induced subgraph G[M] contains no cycles, preventing loops in the path. Together, these properties ensure that the matching set maintains an optimal, conflict-free, and stable configuration

In the subsequent section, the concept of acyclic matching is utilized in a honeycomb network. The resulting algorithms enable the computation of its help to cardinal value and the corresponding edge set .

3. Results

The linear-time algorithms for calculating the maximum number of acyclic matching edges and sets are derived below, where the cardinal value is denoted as , and a proof of correctness is given in the subsequent theorem.

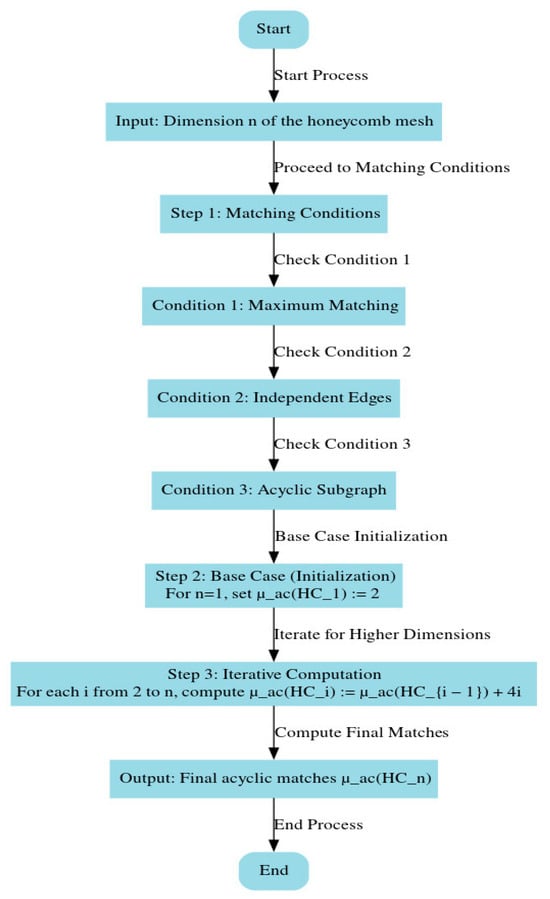

3.1. ALGORITHM 1-AMCV: Acyclic Matching Cardinal Value for Honeycomb

To find the maximum cardinal value of an acyclic matching set of a honeycomb network with .

Input: Dimension of the honeycomb network.

Output: AMCV,

Step 1: Matching Conditions

Ensure the following conditions are met:

- The matching set must be maximum.

- All matching edges must be independent.

- The induced subgraph formed by the matching edges must be acyclic (contains no cycles).

Step 2: Base Case (Initialization)

For :

Step 3: Iterative Computation for Higher Dimensions

For each :

Output:

The total number of acyclic matching edges for the honeycomb network with dimension is given by

The flowchart (refer Figure 4) depicts the procedure of finding the cardinal value .

Figure 4.

Framework to identify AMCV.

3.2. ALGORITHM 2-AMES: Acyclic Matching Edge Set for HCn

A linear-time algorithm for assessing the maximum number of acyclic matching edges is derived. The edge is formed from its own vertices where since there are no loops in the honeycomb. is the matching set of edges. The induced subgraph formed from the edges with no cycles of length and gives the cardinal value.

To find acyclic matching edge set of a honeycomb network with .n-dimension

Input: A honeycomb graph, , where .

Output: The AMES, of and .

- Initialize

- Choose

- ifthen andifthen go to step 2ifthen go to step 2else go to step 4end ifend if

- end if

- 4.

- stop

Computational Complexity Analysis

The AMCV and AMES algorithms offer significant computational advantages. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Computational analysis.

Time Complexity:

AMCV: The iteration across dimensions requires O(n) steps, while all other operations are constant. Therefore, the overall time complexity is O(n). AMCV executes in time, which is sublinear in the number of satellites. Runtime grows linearly with the dimension parameter n, . Higher order results are calculated approximately in Table 2.

Table 2.

Runtime and memory scaling of AMCV and AMES.

AMES: O(n2) linear time, where n is the honeycomb dimension. This is optimal since the number of edges in is 9n2 − 3n.

Space Complexity:

AMCV: Additional data structures are not required, which yields an overall space requirement of O(1).

AMES: O(n2) for storing the matching set.

The advantages over general matching algorithms include specialized structure exploitation. Unlike general maximum matching algorithms (e.g., Edmonds’ algorithm with O(|V|3) complexity), AMES and AMCV exploit honeycomb network regularity for direct computation. General algorithms require complex augmenting path searches. However, AMES uses the proven formula = 2(n2 + n − 1) for direct edge selection. Additionally, the linear time complexity makes the algorithms suitable for real-time satellite constellation reconfiguration, unlike exponential-time general acyclic matching algorithms.

The upcoming theorem derives the proof of correctness for the algorithms provided.

Theorem 1.

If

, then the cardinality series of acyclic matching is for

Proof.

Case (i): If , .

For the graph , the matching edges must be selected in such a way that the induced subgraph must be acyclic. Since it contains a single cell of a hexagon (refer Figure 5), edges can be chosen without even creating . The independent edge set for acyclic matching( is selected, which is marked red in Figure 5, and there are also other possible matching sets. Therefore, the cardinality of acyclic matching of is 2.

Figure 5.

.

Case (ii):

is constructed from by gluing six hexagons to all the edges of . An acyclic path formed by is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

.

.

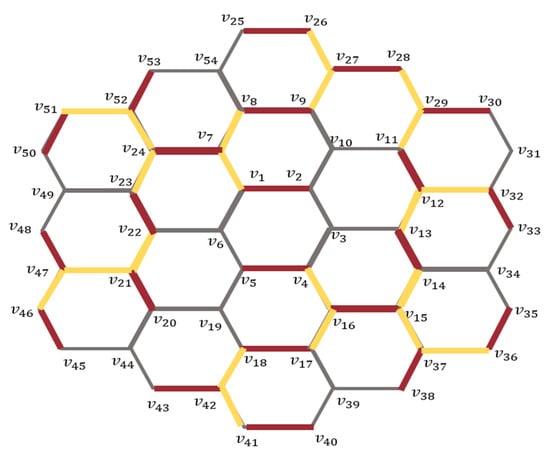

Case (iii):

Each and every boundary edges in gets attached to and forms the mesh . The Figure 7 depicts the induced subgraph forms an acyclic path traced in yellow along with .

Figure 7.

.

(refer Figure 7).

Case (iv): For any , the recursive relationship of arises because each new dimension adds exactly 4n edges to the maximum acyclic matching set. This can be proven by induction:

For n = 1,

Inductive step: Assume for some .

For

For any, the result is .

- Proof by contradiction,

Let be our proposed cardinality.

Case 1. If

, assume. By our construction, there exist at least independent edges in that form an acyclic subgraph. Since our current matching uses fewer than edges, there exists at least one additional edge such that M ∪ {e} maintains all three properties:

- The matching remains maximum after adding e (contradiction with assumption).

- Independence is preserved (e shares no vertices with edges in M).

- Acyclic property is maintained (adding e creates no cycles in G[M∪ {e}]).

This contradicts the assumption that .

Case 2. If

: Assume . This implies either:

- Two edges share a vertex (violating independence property), or

- The induced subgraph G[M] contains a cycle (violating acyclic property)

With more than K edges in , at least one of these violations must occur, contradicting the definition of acyclic matching.

Therefore, is the unique optimal solution.

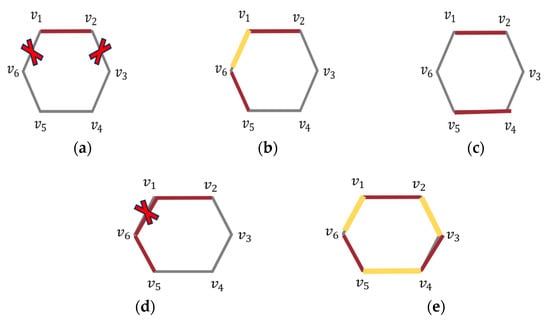

For example, for ,

- The value of from case(i) is 2. Let us assume . We can see from the Figure 8a there is a possibility of selecting one more edge without affecting the first property (cross mark edges),where red denotes . Figure 8b,c show two different possibilities, here yellow edge connects adjacent acyclic matching edges forms induced path. Therefore, must be equal to 2.

Figure 8. (a) . (b) . (c) (d) . (e) .

Figure 8. (a) . (b) . (c) (d) . (e) . - If , then at least one edge in the matching set will share a vertex with another edge, which contradicts that M must have independent edge property or the induced subgraph formed by edges must form a cycle, as shown in the Figure 8d,e, respectively.

Therefore, the only possible cardinality value for acyclic matching must be . The given Figure 8a–e strengthen the result through the contradiction method.

Thus for any n–dimensional honeycomb, the general acyclic matching number can be derived as . □

The applications of acyclic matching in aerospace technology, focusing on enhancing operational stability and enabling fault-tolerant communication in satellite constellations, are discussed in the upcoming section.

4. Discussion

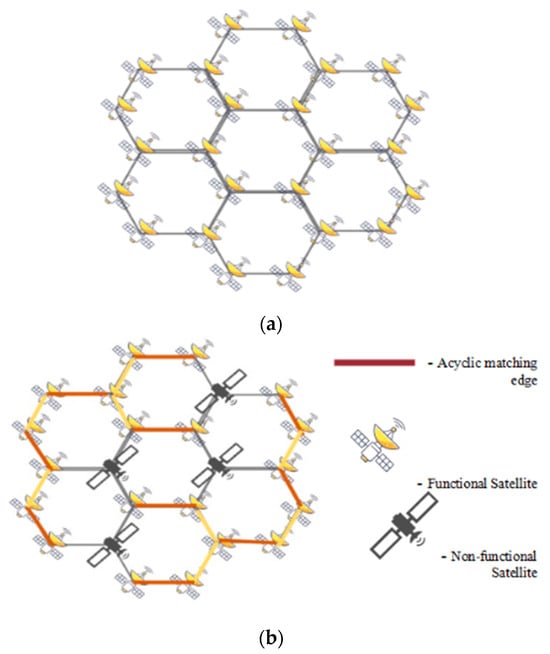

In satellite constellations, the satellites are distributed in space in a structured way to maintain communication coverage [35]. Representing a static satellite constellation in a honeycomb-designed network geometry is efficient in path optimization and fault tolerance. In the honeycomb structure, each satellite represents a node. The communication links or edges are those that connect neighboring satellites. A graph network having redundant cycles in a cyclic communication path leads to the risk of signal interference, feedback loops, or delays in that network. To mitigate this, acyclic matching ensures that only specific paths are active within the network while strictly avoiding cycles.

Acyclic matching provides a structured way to select communication links between satellites so that no two paths share the same node and no closed loops are formed. This ensures that the network operates with minimal redundancy and maximum stability. When a fault occurs, whether due to a satellite failure, debris collision, or signal degradation [36], the acyclic matching framework allows the system to adapt dynamically. Each satellite is continuously monitored through health-check mechanisms that evaluate signal strength and connectivity. If a satellite fails, its neighboring satellites quickly detect the disruption. The system then refers to pre-computed acyclic matching sets, which contain alternative, fault-tolerant communication paths. These backup edges can be activated to reroute signals without introducing cycles or overloading other links. In honeycomb-based satellite constellations, this approach guarantees that communication is rerouted through mathematically optimized paths that remain interference-free and stable. Thus, even when faults occur, satellites within the acyclic matching set effectively provide recovery by maintaining uninterrupted global communication coverage.

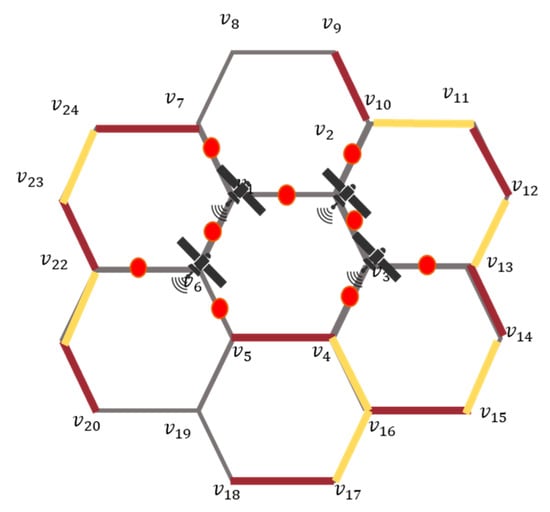

Figure 9a illustrates a honeycomb-designed satellite network that ensures uninterrupted communication (taken from Theorem 1(ii)). If one or more satellites experience a malfunction, the nearest operational satellite reroutes the communication through an acyclic matching set. In the depicted scenario, four satellites have malfunctioned (there are other possibilities). When a disruption occurs in a satellite, its three-way communication link is severed. However, acyclic matching ensures seamless connectivity by rerouting signals through the nearest functional satellite, as each satellite in the matching set is adjacent to a faulty one (refer Figure 9b). This acyclic path prevents redundant information transfer between satellites, optimizing the network. As a result, communication loss is minimized while maintaining maximum coverage.

Figure 9.

(a) Honeycomb-designed satellite network. (b) Implementation of acyclic matching.

4.1. Technical Mechanisms for Fault Tolerance

The honeycomb network offers several key advantages that make it a robust choice for satellite communication systems. Its structural redundancy ensures that each satellite (node) has multiple communication paths through hexagonal connectivity, providing inherent backup routes. The load distribution feature further enhances performance, as the geometric structure naturally balances even signal flow across the network, effectively minimizing the risk of bottlenecks. Additionally, the design supports scalability, since its modular hexagonal pattern allows seamless expansion of the constellation without topology reconfiguration.

Complementing this, acyclic matching plays a crucial role in maintaining network integrity. It prevents loops by ensuring that G[M] remains acyclic, and signals follow deterministic paths without infinite loops or oscillations. Furthermore, the use of independent edges eliminates interference and cross-talk between communication channels. Acyclic matching also enables rapid reconfiguration, as pre-computed sets allow immediate fault recovery without the need for complex recalculations.

When combined, these two approaches create a powerful synergy: the honeycomb structure provides multiple path options, while acyclic matching selects optimal loop-free subsets for active communication, resulting in both reliability and efficiency.

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

This research paper has so far discussed random dysfunctional satellites in between the network. But if the satellites simultaneously fail in the honeycomb network, then the cardinal value will decrease, yielding . For example, in the cardinality is 10 (refer case (ii) in Theorem 1). If satellites fail, communication between 9 satellites will be interrupted as shown in Figure 10, where the red dots denote interruption in between the communications. When we apply acyclic matching, .

Figure 10.

Simultaneous malfunction.

The failure set cannot be included because of the interruption caused by .

Thus, for any n-dimensional honeycomb network, though the theoretical derivation of acyclic matching is precise, when applying in a satellite constellation, the simultaneous failure is the limitation that is yet to be explored as an open problem.

The current work models satellite constellations using a two-dimensional honeycomb structure. Future research can extend this framework to better align with real-world satellite dynamics. A promising direction is to rearrange the satellite constellation into an advanced honeycomb structure. Applying acyclic matching to a more complex 3D honeycomb model could make practical implementation possible and more efficient. Thus, while our work does not directly capture the full dynamics of real constellations, it sets the stage for adapting the presented framework towards realistic 3D orbital topologies and evolving network scenarios.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, an acyclic matching set and its cardinal value within satellite constellations modeled as honeycomb networks were determined to be . Additionally, algorithms AMCV and AMES were derived to compute acyclic matching edges along with their cardinality. Analyzing this technique in various honeycomb-derived mesh networks might lead to advancements in the field of aeronautics.

Author Contributions

S.S. was responsible for manuscript preparation, conceptualization, derivation of the core theorems and algorithm, including creation of all figures and visual illustrations. A.D. provided overall supervision and guidance throughout the research and thoroughly revised the manuscript, methodology from inception to final draft. V.M. Formal analysis. G.A. Investigation. M.S. Software. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMCV | Acyclic Matching Cardinal Value |

| AMES | Acyclic Matching Edge Set |

References

- Yulong, L.; Xiande, W.; Zhongfu, L. Safety risk assessment on communication system based on satellite constellations with the analytic hierarchy process. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2008, 80, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Asif, M.; Nazeer, W. The Study of Honey Comb Derived Network via Topological Indices. Open J. Math. Anal. 2018, 2, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szrama, S. Turbofan engine health status prediction with neural network pattern recognition and automated feature engineering. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2024, 96, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojmenovic, I. Honeycomb networks: Topological properties and communication algorithms. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 1997, 8, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithra, M.R.; Menon, M.K. Secure domination of honeycomb networks. J. Comb. Optim. 2020, 40, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangrade, A.; Agrawal, B.; Kumar, S.; Mansuri, A. A study of applications of graph colouring in various fields. J. Stat. Appl. Math 2022, 7, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Bi, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Lu, G.; Cui, Y.; Tse, K.M. Design and mechanical properties analysis of hexagonal perforated honeycomb metamaterial. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 270, 109091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Patel, R. Recent Advances in Satellite Network Fault Tolerance. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 075101. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1402-4896/adc3d2 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Graph-theoretic approaches to space network optimization. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 4234–4248. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yang, R.; Sun, S.; Niu, B. Advances in the analysis of honeycomb structures: A comprehensive review. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2025, 296, 112208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, D.; Arputhamary, A.; Saffren, S. Defense Mechanism for the Nodes of 2-D Meshes and n-cubes. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT), Bhilai, India, 19–20 February 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, D.; Jothi, R.M.J.; Vidhya, M. Tree Topologies and Node Covers for Efficient Communication in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Advanced Network Technologies and Intelligent Computing, ANTIC 2023; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Verma, A., Verma, P., Pattanaik, K.K., Dhurandher, S.K., Woungang, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, D. Protection of Medical Information Systems Against Cyber Attacks: A Graph Theoretical Approach. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 126, 3455–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadavare, A.B.; Kulkarni, R.V. A Review of Application of Graph Theory for Network. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2012, 3, 5296–5300. [Google Scholar]

- Phule, S.E. Application of graph theory in networking and social media. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 2024, 4, 2581–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyárfás, A. Perfect matchings in shadow colorings. Acta Math. Hungar. 2020, 161, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, N.; Fan, C.; Kleitman, D.; Losonczy, J. Acyclic Matchings. Adv. Math. 1996, 122, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.S.; Pradhan, D. Acyclic matchings in subclasses of bipartite graphs. Discret. Math. Algorithms Appl. 2012, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, M.; Rautenbach, D. A lower bound on the acyclic matching number of subcubic graphs. Discret. Math. 2018, 341, 2353–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, M.; Rautenbach, D. On some hard and some tractable cases of the maximum acyclic matching problem. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.S.; Chaudhary, J. Acyclic Matching in Some Subclasses of Graphs. In Proceedings of the Combinatorial Algorithms: 31st International Workshop, IWOCA 2020, Bordeaux, France, 8–10 June 2020; Volume 12126, pp. 409–421. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, J.; Mishra, S.; Panda, B. Minimum maximal acyclic matching in proper interval graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2025, 360, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, J.; Zehavi, M. Parameterized results on acyclic matchings with implications for related problems. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2025, 148, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffren, S.; Angel, D. Utilizing Acyclic Matching for Enhancing Current flow in Diamond Ladder Structures. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS), Assam, India, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 802–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, M.; Taylor, P. The weak acyclic matching property in abelian groups. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.02178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, M.; Taylor, P. Classifying Abelian Groups Through Acyclic Matchings. Ann. Comb. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampis, M.; Vasilakis, M. Structural Parameterizations for Induced and Acyclic Matching. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, S. On the Complexity of Computing a Maximum Acyclic Matching in Undirected Graphs. Mathematics 2025, 13, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovász, L.; Plummer, M.D. Matching Theory; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0821847596. [Google Scholar]

- Hedayati, M.; Barzegar, A.; Rahimi, A. Fault Diagnosis and Prognosis of Satellites and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabacchin, N.; Colombatti, G. Design of an Orbital Infrastructure to Guarantee Continuous Communication to the Lunar South Pole Region. Aerospace 2025, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffren, S.; Angel, D. Acyclic matching in Hypercube Networks. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Instrumentation and Control Technologies: Computational Intelligence for Smart Systems, ICICICT 2022, Kannur, India, 11–12 August 2022; pp. 681–685. [Google Scholar]

- Saffren, S.; Angel, D. Acyclic matching in Ladder graphs. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2516, 210019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, P.; Bharati, R.; Rajasingh, I.; M, C.M. On minimum metric dimension of honeycomb networks. J. Discret. Algorithms 2008, 6, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, X. A Secure Satellite Transmission Technique via Directional Variable Polarization Modulation with MP-WFRFT. Aerospace 2025, 12, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Liu, C. Fault-tolerant routing in satellite mega-constellations. Comput. Netw. 2023, 220, 109487. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).