Abstract

Self-supervised learning (SSL) is a potential deep learning (DL) technique that uses massive volumes of unlabeled data to train neural networks. SSL techniques have evolved in response to the poor classification performance of conventional and even modern machine learning (ML) and DL models of enormous unlabeled data produced periodically in different disciplines. However, the literature does not fully address SSL’s practicalities and workabilities necessary for industrial engineering and medicine. Accordingly, this thorough review is administered to identify these prominent possibilities for prediction, focusing on industrial and medical fields. This extensive survey, with its pivotal outcomes, could support industrial engineers and medical personnel in efficiently predicting machinery faults and patients’ ailments without referring to traditional numerical models that require massive computational budgets, time, storage, and effort for data annotation. Additionally, the review’s numerous addressed ideas could encourage industry and healthcare actors to take SSL principles into an agile application to achieve precise maintenance prognostics and illness diagnosis with remarkable levels of accuracy and feasibility, simulating functional human thinking and cognition without compromising prediction efficacy.

Keywords:

deep learning (DL); self-supervised learning (SSL); machine learning (ML); cognition; classification; data annotation MSC:

68T07; 68T05; 93E35

1. Introduction

Concepts of AI, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), DL, and ML considered in the last few decades have contributed to multiple valuable impacts and core values to different scientific disciplines and real-life areas because of their amended potency in executing high-efficiency classification tasks of variant complex mathematical problems and difficult-to-handle subjects. However, some of them are more rigorous than others. More specifically, DL, CNN, and artificial neural networks (ANNs) have a more robust capability than conventional ML and AI models in making visual, voice, or textual data classifications [1].

The crucial rationale for these feasible models includes their significant classification potential in circumstances involving therapeutic diagnosis, maintenance, and production line prognostics. As these two processes formulate a prominent activity in medicine and engineering, the adoption of ML and DL models could contribute to numerous advantages and productivity records [2,3,4,5,6].

Unfortunately, documented historical information may not provide relevant recognition solutions for ML and DL, especially for new industry failure situations and recent manufacturing and production fault conditions since the characteristics and patterns of lately-reported problems do not approach past observed datasets. More classification complexity, in this respect, would increase [7].

A second concern pertaining to the practical classification tasks of ML and DL is their fundamental necessity for clear annotated data that can accelerate this procedure, offering escalated accuracy and performance scales [8].

Thirdly, in most data annotation actions, the latter may contribute to huge retardation, labor efforts, and expenses to be completely attained, particularly when real-life branches of science handle big data [9].

Resultantly, a few significant classification indices and metrics may be affected, namely accuracy, efficacy, feasibility, reliability, and robustness [10].

Relying on what had been explained, SSL was innovated with the help of extensive research and development (R&D), aiming to overcome these three obstacles at once. Thanks to researchers who addressed some beneficial principles in SSL to conduct flexible analysis of different data classification modes, such as categorizing nonlinear relationships, unstructured and structured data, sequential data, and missing data.

Technically speaking, SSL is considered a practical tactic for learning deep representations of features and crucial relationships from the existing data through efficient augmentations. Without time-consuming annotations of previous data, SSL models can generate a distinct training objective (considering pretext processes) that relies solely on unannotated data. To boost performance in additional classification activities, the features produced by SSL techniques should have a specific set of characteristics. The representations should be distinguished with respect to the downstream tasks while being sufficiently generic to be utilized on untrained actions [11].

The emergence of the SSL concept has resulted in core practicalities and workable profitabilities correlated with functional information prediction for diverse disciplines that have no prior annotated documented databases, contributing to preferable outcomes in favor of cost-effectiveness, time efficiency, computational effort flexibility, and satisfying precision [12].

Taking into account the hourly, daily, and weekly creation of massive data in approximately each life and science domain, this aspect could pose variant arduous challenges in carrying out proper identification of data, especially when more information is accumulated after a long period of time [13].

Within this framework of background, the motivation for exploring essential SSL practicalities arises from the increasing need to leverage vast amounts of unlabeled data to improve classification performance. Accordingly, the major goal of this article is to enable industrial engineering researchers and medical scientists to better understand major SSL significances and realize comprehensively their pivotal workabilities to allow active involvement of SSL in their work for conducting efficient predictions in diagnoses and prognostics.

To provide more beneficial insights on SSL incorporation into industry and medicine, a thorough review is carried out. It is hoped from this overview that its findings could actually clarify some of SSL’s substantial rationale and innovatory influences to handle appropriate maintenance checks and periodic machine prognostics to make sure production progress and industrial processes are operating safely within accepted measures.

On the other hand, it is actually essential to emphasize the importance of this paper in elucidating a collection of multiple practicalities of SSL to support doctors and clinical therapists in identifying the type of problem in visual data and, thus, following suitable treatment. This clinical action can sometimes be challenging, even for professionals. As a result, other approaches might be implemented, like costly consultations, which are not feasible.

Correspondingly, the organization of this paper is arranged based on the following sequence:

- Section 2 is prepared to outline the principal research method adopted to identify the dominant advantages of SSL algorithms in accomplishing efficient classification tasks without the identification of essential datasets crucial for training and testing procedures to maximize the model’s classification effectiveness.

- Section 3 is structured to explain the extensive review’s prominent findings and influential characteristics that allow SSL paradigms to accomplish different classification tasks, offering elevated scales of robustness and efficacy.

- Section 4 illustrates further breakthroughs and state of the art that have been lately implemented through several research investigations and numerical simulations to foster the SSL algorithms’ categorization productivity and feasibility.

- Section 5 provides noteworthy illustrations and discussion pertaining to the evaluation of SSL serviceable applications and other crucial aspects for classifying and recognizing unlabeled data.

- Section 6 expresses the main research conclusions.

- Section 7 points out the imperative areas of future work that can be considered by other investigators to provide further modifications and enhancements to the current SSL models.

- Section 8 expresses the critical research limitations encountered in the review implementation until it is completed.

Totally, the paper’s contribution is reflected in the following points:

- Cutting much time, effort, and cost connected with essential data annotation for conventional DL and ML models adopted to support medical therapists in diagnosing the type of problem in visual databases,

- Achieving the same relevance for industrial engineers, who wish to make machine prognostics as necessary periodic maintenance actions robustly,

- Performing precise predictions of different problems in medicine, industry, or other important disciplines, where new behaviors of data do not follow previously noted trends, helps predict new data patterns flexibly and reliably in real-life situations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Approach

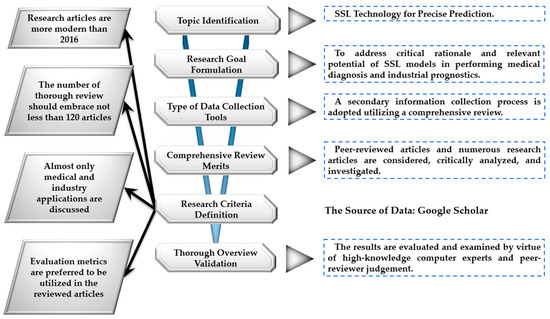

This study considers specific research steps, shown in Figure 1, to accomplish the primary research objective. The data collection process implemented in this article comprises secondary information collection, which relies on addressing beneficial ideas and constructive findings from numerous peer-reviewed papers and recent academic publications, examining variant benefits and many relevances of SSL in recognizing unspecified data, and bringing remarkable rates of workability, accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the comprehensive overview adopted in this paper.

2.2. The Database Selection Criteria

To upgrade the review outcomes’ robustness, this work establishes a research foundation based on certain criteria, depicted in Figure 1, through which some aspects are taken into consideration, including the following:

- The multiple research publications analyzed and surveyed are more modern than in 2016. Thus, the latest results and state-of-the-art advantages can be extracted.

- The core focus of the inspected articles in this thorough overview is linked to SSL’s significance in industry and medicine when involved in periodic machinery prognostics and clinical diagnosis, respectively.

- After completing the analysis of SSL’s relevant merits from the available literature, critical appraisal is applied, referring to some expert estimations and peer reviewer opinions to validate and verify the reliability and robustness of the paper’s overall findings.

3. Related Work

In this section, more explanation concerning the critical characteristics of SSL paradigms and their corresponding benefits and applications is provided, referring to existing databases from the global literature, which comprises recent academic publications and peer-reviewed papers.

More illustration is offered on these aspects in the following sub-sections.

3.1. Major Characteristics and Essential Workabilities of SSL

As illustrated above, supervised learning (SL) needs annotated data to train numerical ML models to enable an efficient classification process in various conventional ML models. On the contrary, unsupervised learning (USL) classification procedures do not require labeled data to accomplish a similar classification task. Rather, USL algorithms can rely solely on identifying meaningful patterns in existing unlabeled data without necessary training, testing, or preparation [14].

For the previously illustrated industrial and medical pragmatic practices, SSL can often be referred to as predictive learning (or pretext learning) (PxL). Labels can be generated automatically, transforming the unsupervised problem into a flexible, supervised one that can be solved viably.

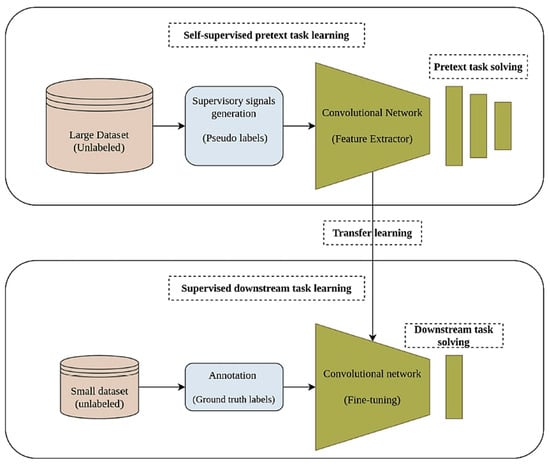

Another favorable solution of SSL algorithms is their efficient categorization of data correlated with natural language processing (NLP). SSL can allow researchers to fill in blanks in databases when they are not fully complete or have a high-quality definition. As an illustration, with the application of ML and DL models, existing video data can be utilized to reconstruct previous and future videos. However, without relying on the annotation procedure, SSL takes advantage of patterns linked to the current video data to efficiently complete the categorization procedure of a massive video database [15,16]. Correspondingly, the critical working principles of the SSL approach can be illustrated in the workflow shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The major workflow related to SSL [17].

From Figure 2, during the pre-training stage (pretext task solving), feature extraction is carried out by pseudo-labels to enable an efficient prediction process. After that, transfer learning is implemented to initiate the SSL phase, in which a small dataset is considered to make data annotations (of ground truth labels). Then, fine-tuning is performed to achieve the necessary prediction task.

3.2. Main SSL Categories

Because it can be laborious to compile an extensively annotated dataset for a given prediction task, USL strategies have been proposed as a means of learning appropriate image identification without human guidance [18,19]. Simultaneously, SSL is an efficient approach through which a training objective can be produced from the data. Theoretically, a deep neural network (DNN) is trained on pretext tasks, in which labels are automatically produced without human annotation. The learned representations can be utilized to complete the pretext tasks. Familiar SSL sorts involve: (A) generative, (B) predictive, (C) contrastive, and (D) non-contrastive models. The multiple contrastive and noncontrastive tactics illustrated in this paper can be recognized as joint-embedded strategies.

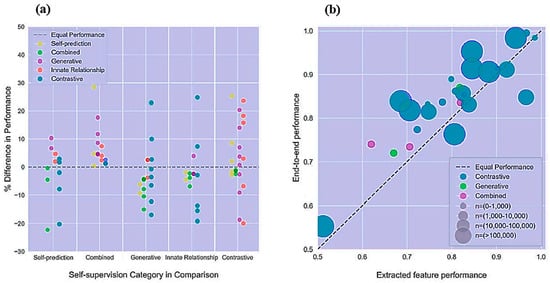

However, more types of SSL are considered in some contexts. For example, a graphical illustration in [20] was created, explaining the performance rates that can be achieved when SSL is applied, focusing mainly on further SSL categories, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Two profiles of (a) some types of SSL classification with their performance level and (b) end-to-end performance of extracted features and the corresponding number of each type [20].

It can be realized from the graphical data expressed in Figure 3a that the variation in the performance between the self-prediction, combined, generative, innate, and contrastive SSL types fluctuates mostly between 10% and 10%. In Figure 3b, it can be noticed that end-to-end performance corresponding to contrastive, generative, and combined SSL algorithms varies between nearly 0.7 and 1.0, relating to an extracted feature performance that ranges approximately between 0.7 and 1.0.

In the following sections, more explanation is provided for some of these SSL categories.

3.2.1. Generative SSL Models

Using an autoencoder to recreate an input image following compression is a common pretext operation. Relying on the first component of the network, called an encoder, the model should learn to compress all pertinent data from the image into a latent space with reduced dimensions to minimize the reconstruction loss. The image is then reconstructed by the latent space of a second network component called a decoder.

Researchers in [18,19,21,22,23,24,25] reported that denoising autoencoders could also provide reliable and stable identifications of images by learning to filter out noise. The network cannot learn the identity function owing to extra noise. By encoding the distribution parameters of a latent space, variational autoencoders (VAE) can advance the autoencoder model [26,27,28,29]. Both the reconstruction of error and extra factor, the Kull-Leibler divergence between an established latent distribution (often a unit-centered Gaussian distribution), and the encoder output are minimized during training. The samples from the resulting distribution can be obtained through this regularization of the latent space. To rebuild entire patches with only 25 percent of the visible patches, scholars in [30,31] have recently adopted vision transformers to create large masked autoencoders that work at the patch level rather than pixel-wise. Adding a class token to a sequence of patches or performing global mean pooling on all the patch tokens, as in this reconstruction challenge, yields reliable image representations.

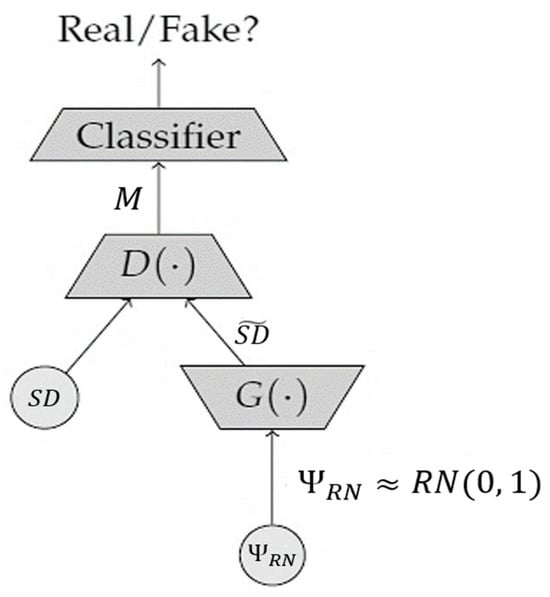

A generative adversarial network (GAN) is another fundamental generative USL paradigm that has been extensively studied [32,33,34]. This architecture and its variants aim to mimic real data’s appearance and behavior by generating new data from random noise. To train a GAN, two networks compete in an adversarial minimax game, with one learning to turn the rate of random noise, into synthetic data, , which attempts to mimic the distribution of the original data. These aspects can be illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The architecture employed in GAN. Adopted from Ref. [35], used under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

In the adversarial method, a second network, which can be termed discriminator D(.) was trained to distinguish between generated and authentic images from the original dataset. When the discriminator is certain that the input image is from the true data distribution, it reports a score of 1, whereas for the images produced by the generator, the score is zero. One possible estimation of this adversarial objective function, , can be accomplished by the following mathematical formula:

where:

- —A group of random noise vectors with an overall amount of N

- —A dataset comprising a set of real images having a total number of .

3.2.2. Predictive SSL Paradigms

Models trained to estimate the impact of artificial change on the input image express the second type of SSL technique. This strategy is inspired by understanding the semantic items and regions inside an image, which can be essential for accurately predicting the transformation. Scholars in [36] conducted analytical research to improve the performance of the model against random initialization and to approach the effectiveness obtained from the initialization with ImageNet pre-trained weights in benchmark computer vision datasets by pre-training a paradigm to predict the relative positions of two image patches.

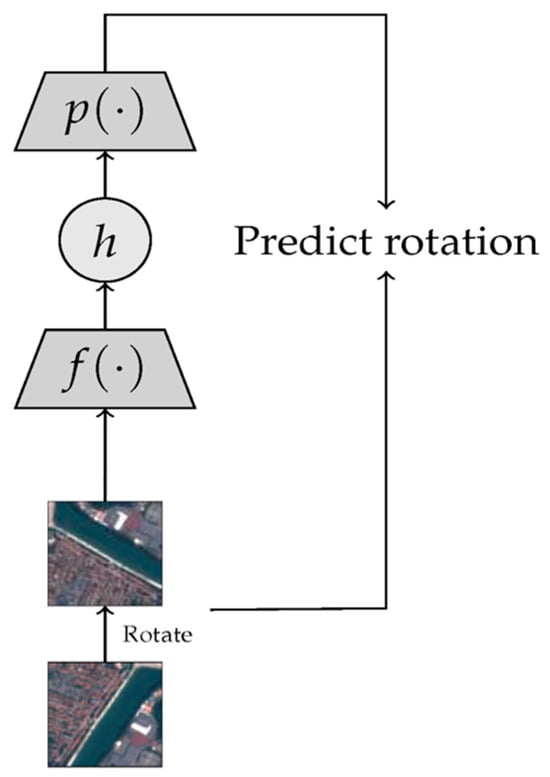

Some researchers have confirmed the advantages of colored images [37]. In this method, the input image is first changed to grayscale. Next, a trained autoencoder converts the grayscale image back to its original color form by minimizing the average squared error between the reconstructed and original images. The encoder feature representations are considered in the subsequent downstream processes. The numerical RotNet approach [38] is another well-known predictive SSL approach, which represents a practical training process for mathematical schemes to help predict the rotation that is randomly implemented in the input image, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flowchart configuration of the operating principles related to the intelligent RotNet algorithm relying on the SSL approach for accurate prediction results. From Ref. [35], used under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

To improve the performance of the model in a dynamic rotation prediction task, the relevant characteristics that classify the semantic content of the image should first be extracted. Researchers in [39] considered a jigsaw puzzle to forecast the relative positions of the picture partitions using the shuffled SSL model. The Exemplar CNN was also addressed and trained in [40] to predict augmentations that can be applied to images by considering a wide variety of augmentation types. Cropping, rotation, color jittering, and contrast adjustment are examples linked to the enhancement classes gained by the Exemplar CNN model.

An SSL model can learn rich representations of the visual content by completing one of these tasks. However, the network may not be able to perform effectively on all subsequent tasks contingent on the pretext task and dataset. Because the orientation of objects is not as rigorously practical to handle in remote sensing datasets as in object-centric datasets, the prediction of random rotations of an image would not perform particularly well on such a dataset [41].

3.2.3. Contrastive SSL Paradigms

Forcing the features of various perspectives in a picture to be comparable is another strategy that can result in accurate representations. The resulting representations are independent of the particular enhancements needed to generate various image perspectives. However, the network can be converged to a stable representation that meets the invariance condition but is unrelated to the input image.

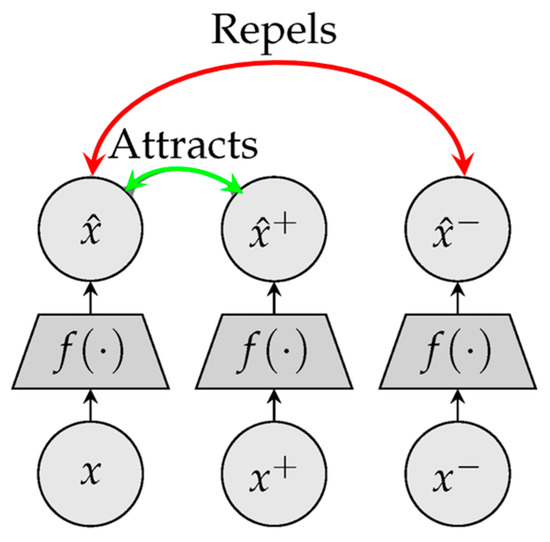

One typical approach to achieving this goal via the acquisition of various representations while avoiding the collapse problem is the contrastive loss. This type of loss function can be utilized to train the model to distinguish between views of the same image (positive) and views of distinct images (negative). Correspondingly, it seeks to obtain homogeneous feature representations for pairs with positive values while isolating features for negative pairs. The triplet loss investigated by researchers in [42] is the simplest form of this family. It requires a model to be trained such that the distance between the representations of a given anchor and its positive rates is smaller than the distance between the representations of the anchor and the random negative, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The architecture of the triplet loss function. From Ref. [35], used under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

In Figure 6, the triplet loss function is considered helpful in learning discriminative representations by learning an encoder that is able to detect the difference between negative and positive samples. Under this setting, the triplet Loss Function, , can be estimated using the following relationship:

where:

- —The positive vector value of the anchor x

- —The negative vector value of the anchor x

- —The embedding function

- —The value of the margin parameter.

In [43], the researchers examined the SimCLR method, which is one of the most well-known SSL strategies. It formulates a type of contrastive representational learning. Two versions of each training batch image can be generated using random-sampling augmentation. After these modified images are fed into the representational method, a prediction network can be utilized to map the representation onto a hypersphere of dimension, .

The overall mathematical algorithm is trained to elevate the cosine similarity across the representation parameter, , and its corresponding positive counterpart, (belonging to the same original visual data) and to minimize the similarity between and all other representations in the batch , contributing to the following expression:

where:

- the dot product between and .

- the temperature variable to scale the levels of similarity, distribution, and sharpness.

- the embedding function.

At the same time, the algebraic correlation connected with the evaluation process of the complete loss function that assesses the cross-entropy of temperature, which can be dominated as normalized temperature cross-entropy, which is denoted by -S, is depicted in the following relation:

where indicates the number of items in the dataset, such as images and textual characters.

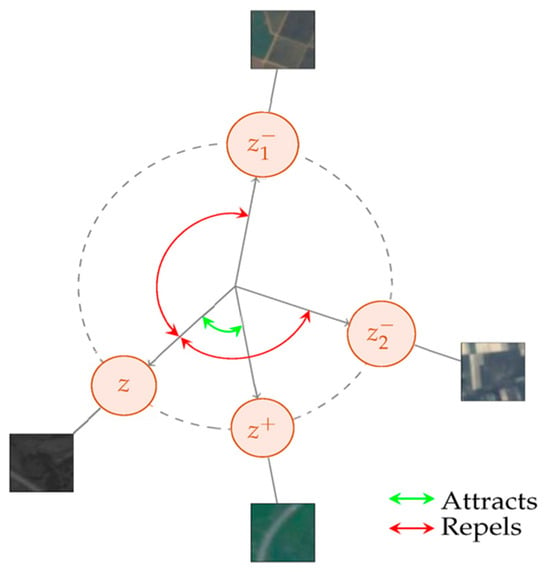

Figure 7 shows that the NT-Xent loss [44] acts solely on the direction of the features confined to the D-dimensional hypersphere because the representations are normalized before calculating the function loss value.

Figure 7.

Description of contrastive loss linked to the 2-dimensional unit sphere with two negative parameters ( and ) and one positive () sample from the EuroSAT dataset. From Ref. [35], used under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

By maximizing the mutual data between the two perspectives, this loss ensures that the resulting representations are both style-neutral and content-specific.

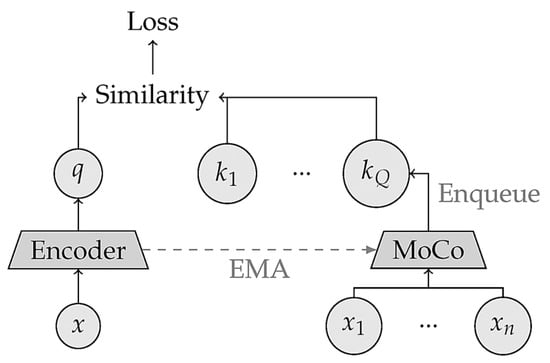

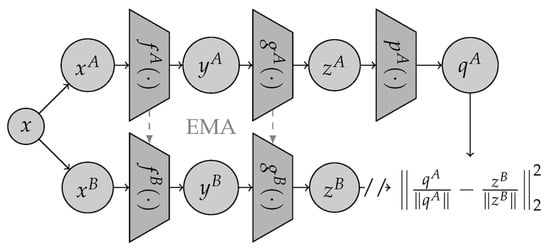

In addition to SimCLR, they suggested the momentum contrast (MoCo) technique, which uses a reduced number of batches to calculate the contrastive loss while maintaining the same functional number of negative samples [45]. It employs an exponentially moving average (EMA)-updated momentum encoder whose values are updated by the main encoder’s weights and a sample queue to increase the number of negative samples in each batch, as shown in Figure 8. To account for the newest positives, the oldest negatives from the previous batch were excluded. Other techniques, such as swapping assignments across views (SwAVs), correlate views to consistent clusters between positive pairs by clustering representations into a shared set of prototypes [44,46,47,48]. The entropy-regularized optimal transport strategy is also used in the same context to move representations between clusters in a manner that prevents them from collapsing into one another [46,49,50,51,52,53]. Finally, the cross-entropy between the optimal tasks in one branch and the anticipated distribution in the other is minimized by the loss. To feed sufficient negative samples to the loss function and avoid representations from collapsing, contrastive approaches often need large batch sizes.

Figure 8.

An illustration of Q samples developed utilizing a momentum encoder whose amounts are modified. From Ref. [35], used under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

As shown in Figure 8, at each step of the numerical analysis, only the major encoder amounts are updated based on the backpropagation process. The similarity aspects between the queue and encoded batch samples were then employed for contrastive loss.

Compared with traditional prediction methods, joint-embedding approaches tend to generate broader representations. Nonetheless, their effectiveness in downstream activities may vary depending on the augmentation utilized. If a model consistently returns the same representations for differently cropped versions of the same image, it can effectively remove any spatial information about the image and will likely perform poorly in tasks such as semantic segmentation and object detection, which rely on this spatial information. Dense contrastive learning (DCL) has been proposed and considered by various researchers to address this issue [54,55,56,57]. Rather than utilizing contrastive loss on the entire image, it was applied to individual patches. This permitted the contrastive model to acquire representations that are less prone to spatial shifts.

3.2.4. Non-Contrastive SSL Models

To train self-supervised models, alternative methods within joint-embedded learning frameworks can prevent the loss of contrastive elements. They classified these as approaches that do not rely on contrast. Bootstrap Your Own Latent (BYOL) is a system based on mentor-apprentice pairing [58,59,60]. The student network in a teacher-student setup is taught to mimic the teacher network’s output (or characteristics). This method is frequently utilized in knowledge distillation when the instructor and student models possess distinct architectures (e.g., when the student model is substantially smaller than the teacher model) [61]. The weights of the instructor network in BYOL are defined as the EMA of the student network weights. Two projector networks, and , are utilized after the encoders, and , to calculate the training loss. Subsequently, to extract representations at the image level, they retrain only the student encoder . Additional asymmetry is introduced between the two branches by a predictor network superimposed on the student projector, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Architecture of the non-contrastive BYOL method, considering student A and lecturer B pathways to encode the dataset. From Ref. [35], utilized under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

In Figure 9, the teacher’s values are modified and updated by the EMA technique applied to the student amounts. The online branch is also supported by an additional network, , which is known as the predictor [60].

SimSiam employs a pair of mirror-image networks and a predictor network at the end of a node [62,63,64]. The loss function employs an asymmetric stop gradient to optimize the pairwise alignments between positive pairs because the two branches have identical weights. Relying on a student-teacher transformer design known as self-distillation, DINO (self-distillation with no labels) defines the instructor as an EMA of the weights in the student network [65]. Next, the teacher network’s centered and sharpened outputs are utilized to train the student network to make exact predictions for a given positive pair.

Another non-contrastive learning model, known as the Barlow Twins, can be offered according to the information bottleneck theory, which eliminates the need for individual amounts for each branch of the teacher-student model considered in BYOL and SimSiam [66,67]. This technique enhances the mutual information between two perspectives by boosting the cross-correlation of the matching characteristics provided by two identical networks and eliminating superfluous information in these representations. The Barlow twin loss function was evaluated by the following equation:

where is the cross-correlation matrix calculated by the following formula:

where and express the corresponding outcomes related to the two identical networks provided by the two views of a particular photograph.

Variance, invariance, and covariance regularization (VICReg) approaches have been recently proposed to enhance this framework [68,69,70,71]. In addition to invariance, which implicitly maximizes alignments between positive pairs, the loss terms are independent for every branch, unlike in low twins. Using distinct regularization for each pathway, this method allows for noncontrastive multimodal pre-training between text and photo pairs.

Most of these techniques train a linear classifier on the priority of representations as the primary performance metric. Researchers in [70] analyzed the beneficial impacts of ImageNet, whereas scholars in [69,72] examined CIFAR’s advantages, which help accomplish an active analysis of object-centric visual datasets commonly addressed for the pre-training and linear probing phases of DL. Therefore, these techniques may not apply to image classification.

Scholars are invited to examine devoted review articles for further contributory information and essential fundamentals pertaining to SSL types [68,73].

3.3. Practical Applications of SSL Models

Before introducing the common applications and vital utilizations of SSL models to handle efficacious data classification and identification processes, their critical benefits should be identified as a whole. The commonly-addressed benefits and vital advantages of SSL techniques can be expressed as follows [74,75]:

- Minimizing the massive cost connected with data labeling phases is essential to facilitating a high-quality classification/prediction process.

- Alleviating the corresponding time needed to classify/recognize vital information in a dataset,

- Optimizing the data preparation lifecycle is typically a lengthy procedure in various ML models. It relies on filtering, cleaning, reviewing, annotating, and reconstructing processes through training phases.

- Enhancing the effectiveness of AI models. SSL paradigms can be recognized as functional tools that allow flexible involvement in innovative human thinking and machine cognition.

According to these practical benefits, further workable possibilities and effective prediction and recognition impacts can be explained in the following paragraphs, which focus mainly on medical and engineering contexts.

3.3.1. SSL Models for Medical Predictions

Krishnan et al. (2022) [76] analyzed SSL models’ application in medical data classification, highlighting the critical challenges of manual annotation of vast medical databases. They addressed SSL’s potential for enhancing disease diagnosis, particularly in EHR and some other visual clinical datasets. Huang et al. (2023) [20] conducted a systematic review affirming SSL’s benefits in supporting medical professionals with precise classification and therapy identification from visual data, reducing the need for extensive manual labeling.

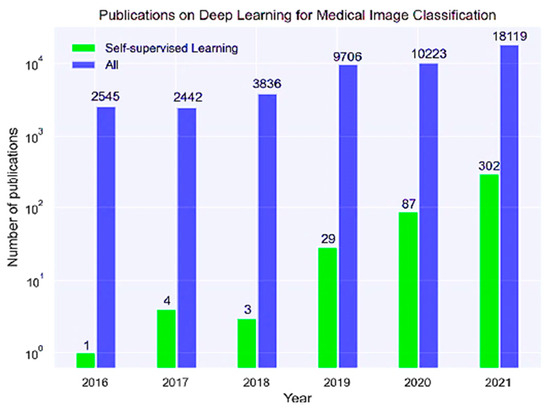

Figure 10 shows the number of DL, ML, and SSL research articles published between 2016 and 2021.

Figure 10.

The number of articles on SSL, ML, and DL models utilized for medical data classification [20].

It can be concluded from the statistical data explained in Figure 10 that the number of research publications addressing ML and DL models’ importance and relevance in the medical classification has been increasing per year. Similarly, the increasing trend was for the overall number of academic articles investigating the SSL, ML, and DL algorithms in conducting high-performance identification of problems in images of patients.

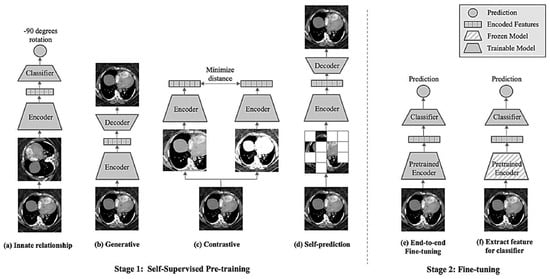

Besides these numeric figures, an explanation of the pre-training process of SSL and fine-tuning can be expressed in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

The two stages of pre-training and fine-tuning are considered in the classification of visual data [20].

It can be inferred from the data explained in Figure 11 that the pre-training SSL process takes into account four critical types to be accomplished, including (Figure 11a) innate relationship, (Figure 11b) generative, (Figure 11c) contrastive, and (Figure 11d) self-prediction. At the same time, there are two categories included in the fine-tuning process, which comprise end-to-end and feature extraction procedures.

Before the classification process is done, SSL models are first trained. This step is followed by the encoding of image features. It follows the adoption of the classifier, which is important to enable precise prediction of the medical problem in the image.

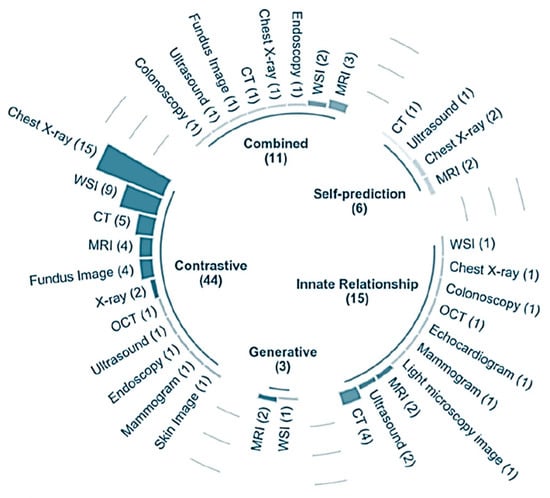

In their overview [20], the scholars identified a collection of some medical disciplines in which SSL models can be advantageous in conducting the classification process flexibly, which can be illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The major categories correlated with medical classification can be done by SSL models [20].

From the data expressed in Figure 12, it can be inferred that the possible medical classification types and dataset categories are numerous in SSL models that can be applied reliably for efficient classification. As a result, this aspect makes SSL models more practical and feasible for carrying out robust predictions of problems in clinical datasets.

Various studies have explored the application of SSL models in medical data classification, showcasing their efficacy in improving diagnostic accuracy and efficiency. Azizi et al. (2021) [77] demonstrated the effectiveness of SSL algorithms in classifying medical disorders within visual datasets, particularly highlighting advancements in dermatological and chest X-ray recognition. Zhang et al. (2022) [78] utilized numerical simulations to classify patient illnesses on X-rays, emphasizing the importance of understanding medical images for clinical knowledge. Bozorgtabar et al. (2020) [79] addressed the challenges of data annotation in medical databases by employing SSL methods for anomaly classification in X-ray images. Tian et al. (2021) [80] identified clinical anomalies in fundus and colonoscopy datasets using SSL models, emphasizing the benefits of unsupervised anomaly detection in large-scale health screening programs. Ouyang et al. (2021) [81] introduced longitudinal neighborhood embedding SSL models for classifying Alzheimer’s disease-related neurological problems, enhancing the understanding of brain disorders. Liu et al. (2021) [82] proposed an SSMT-SiSL hybrid model for chest X-ray data classification, highlighting the potential of SSL techniques to expedite data annotation and improve model performance. Li et al. (2021) [83] addressed data imbalances in medical datasets with an SSL approach, enhancing lung cancer and brain tumor detection. Manna et al. (2021) [84] demonstrated the practicality of SSL pre-training in improving downstream operations in medical data classification. Zhao and Yang (2021) [85] utilized radiomics-based SSL approaches for precise cancer diagnosis, showcasing SSL’s vital role in medical classification tasks.

3.3.2. SSL Models for Engineering Contexts

In the field of engineering, SSL models may provide contributory practicalities, especially when prediction tasks in mechanical, industrial, electrical, or other engineering domains are necessary without the need for massive data annotations to train and test conventional models to accomplish this task accurately and flexibly.

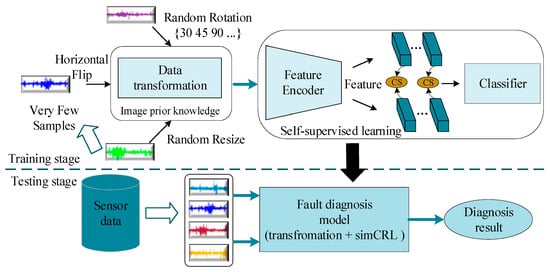

In this context, Esrafilian and Haghighat (2022) [86] explored the critical workabilities of SSL models in providing sufficient control systems and intelligent monitoring frameworks for heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems. Typically, ML and DL models may not contribute to noteworthy advantages since complicated relationships, patterns, and energy consumption behaviors are not directly and clearly provided. The controller was created by employing a model-free reinforcement learning technique recognized with a double-deep Q-network (DDQN). Long et al. (2023) [87] proposed an SSL-based defect prognostics-trained DL model, SSDL, addressing the challenges of costly data annotation in industrial health prognostics. SSDL dynamically updates a sparse auto-encoder classifier with reliable pseudo-labels from unlabeled data, enhancing prediction accuracy compared with static SSL frameworks. Yang et al. (2023) [88] developed an SSL-based fault identification model for machine health prognostics, leveraging vibrational signals and one-class classifiers. Their SSL model, utilizing contrastive learning for intrinsic representation derivation, outperformed novel numerical models in fault prediction accuracy during simulations. Wei et al. (2021) [89] utilized SSL models for rotary machine failure diagnosis, employing 1-D SimCLR to efficiently encode patterns with a few unlabeled samples. Their DTC-SimCLR model combined data transformation combinations with a fixed feature encoder, demonstrating effectiveness in diagnosing cutting tooth and bearing faults with minimal labeled data. Overall, DTC-SimCLR had improved diagnosis accuracy and fewer samples. Figure 13 depicts a low-sample machine failure diagnosis approach.

Figure 13.

The formulated system for machine failure diagnosis needs very few samples [89].

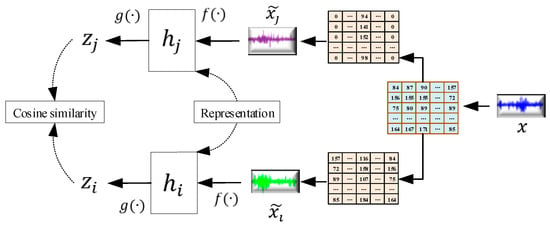

Furthermore, the procedure related to the SSL in SimCLR can be expressed in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The procedure related to the SSL in SimCLR [89].

Simultaneously, Table 1 indicates the critical variables correlated with the 1D SimCLR.

Table 1.

The major variables linked to the 1D SimCLR [89].

Above these examples, Lei et al. (2022) [90] addressed SSL models in predicting the temperature of aluminum correlated with industrial engineering applications. Through their numerical analysis, they examined how changing the temperature of the pot or electrolyte could affect the overall yield of aluminum during the reduction process through their proposed deep long short-term memory (D-LSTM).

On the other side, Xu et al. (2022) [91] identified the contributory rationale of functional SSL models to offer alternative solutions to conventional human defect detection methods that became insufficient. Bharti et al. (2023) [92] remarked that deep SSL (DSSL) contributed to significant relevance in the industry owing to its potency in reducing the time and effort required by humans for data annotation by manipulating operational procedures carried out by robotic systems, taking into account the CIFAR-10 dataset. Hannan et al. (2021) [93] implemented SSL prediction to estimate the state of charge (SOC) correlated with lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries precisely in electric vehicles (EVs) to ensure their maximum cell lifespan.

3.3.3. Patch Localization

Regarding the critical advantages and positive gains of SSL models in conducting active processes of patch localization, several authors confirmed the significant effectiveness and valuable merits of innovative SSL schemes in accomplishing optimum activities of recognition and detection related to a defined dataset of patches. For instance, Li et al. (2021) [94] estimated the substantial contributions of SSL in identifying visual defects or irregularities in an image without relying on abnormal training data. The patch localization of visual defects involves grid classes, wood, screws, metal nuts, hazelnuts, and bottles.

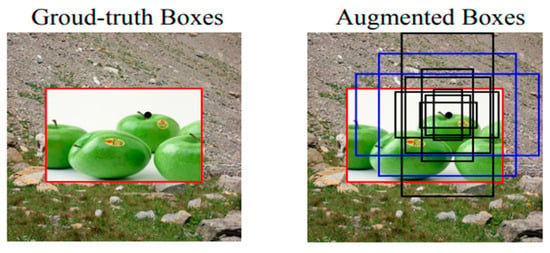

Although SSL has made great strides in the field of image classification, there is moderate effectiveness in making precise object recognition. Through their analysis, Yang et al. (2021) [95] aimed to improve self-supervised, pre-trained models for object detection. They proposed a novel self-supervised pretext algorithm called instance localization, proposing an augmentation strategy for the image-bounding boxes. Their results confirmed that their pre-trained algorithm for object detection was improved, but it became less effective in ImageNet semantic classification and more so in image patch localization. Object detection considering the PASCAL VOC and MSCOCO datasets revealed that their method achieved state-of-the-art transfer learning outcomes.

The red box in their result, expressed in Figure 15, indicates the base truth bounding box linked to the foreground image. However, the right-hand photo shows a group of anchor boxes positioned in the central area related to a singular spatial location. By improving the multiple anchors using variant scales, positions, and aspect ratios, the base truth pertaining to the blue boxes can be augmented, offering an intersection over union (IoU) level greater than 0.5.

Figure 15.

Bounding boxes addressed for spatial modeling [95].

To train an end-to-end model for anomaly identification and localization using only normal training data, Schlüter et al. (2022) [96] created a flexible self-supervision patch categorization model called natural synthetic anomalies (NSA). Their NSA harnessed Poisson photo manipulation to combine scaled patches of varying sizes from multiple photographs into a single coherent entity. Compared with other data augmentation methods for unsupervised anomaly identification, this aspect helped generate a wider variety of synthetic anomalies that were more akin to natural sub-image inconsistencies. Natural and medical images were employed to test their proposed technique, including the MVTec AD dataset, indicating the efficient capability of identifying various unknown manufacturing defects in real-world scenarios.

3.3.4. Context-Aware Pixel Prediction

Learning visual representations from unlabeled photographs has recently witnessed a rapid evolution owing to self-supervised instance discrimination techniques. Nevertheless, the success of instance-based objectives in medical imaging is unknown because of the large variations in new patients’ cases compared with previous medical data. Context-aware pixel prediction focuses on understanding the most discriminative global elements in an image (such as the wheels of a bicycle). According to the research investigation conducted by Taher et al. (2022) [97], instance discrimination algorithms have poor effectiveness in downstream medical applications because the global anatomical similarity of medical images is excessively high, resulting in complicated identification tasks. To address this shortcoming, scholars have innovated context-aware instance discrimination (CAiD), a lightweight but powerful self-supervised system, considering: (a) generalizability and transferability; (b) separability in embedding space; and (c) reusability and systematic reusability. The authors addressed the dice similarity coefficient (DSC) as a measure related to the similarity between two datasets that are often indicated as binary arrays. Similarly, authors in [98] proposed a teacher-student strategy for representation learning, wherein a perturbed version of an image serves as an input for training a neural net to reconstruct a bag-of-visual-words (BoW) representation referring to the original image. The BoW targets are generated by the teacher network, and the student network learns representations while simultaneously receiving online training and an updated visual word vocabulary.

Liu et al. (2018) [57] distinguished some beneficial yields of SSL models in identifying information from defined datasets of context-aware pixel databases. To train the CNN models necessary for depth evaluation from monocular endoscopic data without a priori modeling of the anatomy or coloring, the authors implemented the SSL technique, considering a multiview stereo reconstruction technique.

3.3.5. Natural Language Processing

Fang et al. (2020) [15] considered SSL to classify essential information in certain defined datasets related to natural language processing. Scholars explained that pre-trained linguistic models, such as bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERTs) and generative pre-trained transformers (GPTs), have proved their considerable effectiveness in executing active linguistic classification tasks. Existing pretraining techniques rely on auxiliary prediction tasks based on tokens, which may not be effective for capturing sentence-level semantics. Thus, they proposed a new approach that recognizes contrastive self-supervised encoder representations using transformers (CERTs). Baevski et al. (2023) [99] highlighted critical SSL models’ relevance to high-performance data identification correlated with NLP. They explained that currently available techniques of unsupervised learning tend to rely on resource-intensive and modal-specific aspects. They added that the Data2vec model expresses a practical learning paradigm that can be generalized and broadened across several modalities. Their study aimed to improve the training efficiency of this model to help handle the precise classification of NLP problems. Park and Ahn (2019) [100] inspected the vital gains of SSL to lead to efficient detection of NLP. Researchers proposed a new approach dedicated to data augmentation that considers the intended context of the data. They suggested a label-asked language model (LMLM), which can effectively employ the masked language model (MLM) in data with label information by including label data for the mask tokens adopted in the MLM. Several text classification benchmark datasets were examined in their work, including the Stanford sentiment treebank-2 (SST2), multi-perspective question answering (MPQA), text retrieval conference (TREC), Stanford sentiment treebank-5 (SST5), subjectivity (Subj), and movie reviews (MRs).

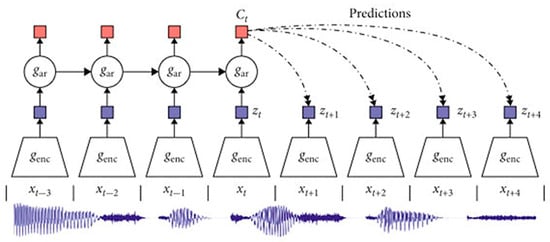

3.3.6. Auto-Regressive Language Modeling

Elnaggar et al. (2022) [101] published a paper shedding light on valuable SSL roles in handling the active classification of datasets connected to the modeling of auto-regressive language. The scholars trained six models, four auto-encoders (BERT, Albert, Electra, and T5), and two auto-regressive prototypes (Transformer-XL and XLNet) on up to 393 billion amino acids from UniRef and BFD. The Summit supercomputer was utilized to train the protein LMs (pLMs), which required 5616 GPUs and a TPU Pod with up to 1024 cores. Lin et al. (2021) [102] performed numerical simulations, exploring the added value of three SSL models, notably (I) autoregressive predictive coding (APC), (II) contrastive predictive coding (CPC), and (III) wav2vec 2.0, in performing flexible classification and reliable recognition of datasets engaged in auto-regressive language modeling. Several any-to-any voice conversion (VC) methods have been proposed, like AUTOVC, AdaINVC, and FragmentVC. To separate the feature material from the speaker information, AUTOVC and AdaINVC utilize source and target encoders. They proposed a new model, known as S2VC, which harnesses SSL by considering multiple features of the source and target linked to the VC model. Chung et al. (2019) [103] proposed an unsupervised auto-regressive neural model to help students learn generalized representations of speech. Their speech representation learning approach was developed to maintain information for various downstream applications to remove noise or speaker variability.

3.4. Commonly-Utilized Feature Indicators of SSL Models’ Performance

Specific formulas in [104,105] were investigated to examine different SSL paradigms in carrying out their classification task, particularly the prediction and identification of faults and errors in machines, which can support maintenance specialists in selecting the most appropriate repair approach. These formulas formulate practical feature indicators to monitor signals that can be prevalently utilized by maintenance engineers to identify the health state of machines. Twenty-four typical feature indicators were addressed, referring to Zhang et al. (2022) [106]. These indices can enable maintenance practitioners to locate optimum maintenance strategies to apply to industrial machinery, helping to handle current failure issues flexibly. Those twenty-four feature indicators are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalent signal feature indicators utilized to examine and diagnose machine and industrial equipment health.

Table 2.

Prevalent signal feature indicators utilized to examine and diagnose machine and industrial equipment health.

| Feature Indicator Type | Major Formula | Eq# |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Value | (7) | |

| Standard Deviation | (8) | |

| Square Root Amplitude | (9) | |

| Absolute Mean Value | (10) | |

| Skewness | (11) | |

| Kurtosis | (12) | |

| Variance | (13) | |

| Kurtosis Index | (14) | |

| Peak Index | (15) | |

| Waveform Index | (16) | |

| Pulse Index | (17) | |

| Skewness Index | (18) | |

| Frequency Mean Value | (19) | |

| Frequency Variance | (20) | |

| Frequency Skewness | (21) | |

| Frequency Steepness | (22) | |

| Gravity Frequency | (23) | |

| Frequency Standard Deviation | (24) | |

| Frequency Root Mean Square | (25) | |

| Average Frequency | (26) | |

| Regularity Degree | (27) | |

| Variation Parameter | (28) | |

| Eigth-Order Moment | (29) | |

| Sixteenth-Order Moment | (30) |

Those twenty-four indices can serve as prior feature group, FG, which can be illustrated by the following:

The twenty-four feature indicators can be utilized relying on the data standardization process, which can be achieved by the following mathematical expression:

4. Statistical Figures on Critical SSL Rationale

To provide elaborating statistical facts pertaining to SSL importance in handling robust data detection and efficient data classification crucial for industrial disciplines, two comparative analyses were implemented; the first one is correlated with fault diagnostics in actual industrial applications. In the meantime, the second comparative study is concentrated on the essential prediction of health issues in the real medical context.

Table 3 summarizes the major findings and major limitations of SSL models involved in real industrial scenarios.

Table 3.

Summary of the core findings and critical limitations respecting SSL engagement in different real industrial scenarios for machine health prognostics and fault prediction.

From Table 3, the material significance of SSL models can be noticed from their considerable practicalities in carrying out precise machine failure prediction, supporting the maintenance team in executing the necessary repair procedures without encountering the common problems of massive data annotation and time-consuming identification of wide failure mode databases, which are essential for DL and ML models.

Besides these noteworthy findings, it is crucial to point out that in spite of the constructive prediction success of those SSL paradigms, there are a couple of issues that could restrict their broad prediction potential, including instability, imbalance, noise, and random variations in the data, which may cause uncertainties and a reduction in their overall prediction performance. Correspondingly, it is hoped that these barriers can be handled efficiently in future work.

On the other hand, Table 3 provides some concluding remarks pertaining to the imperative outcomes and prevalent challenges of SSL paradigms utilized in real medical health diagnosis.

It is inferred from the outcomes explained in Table 4 that SSL also offered a collection of noteworthy implications in favor of better medical treatment that can support healthcare providers in classifying swiftly and durably the sort of clinical problem in patients. Therefore, the most appropriate therapeutic process can be successfully prescribed. Similar to what was discussed previously pertaining to the industrial domain, performing the prognosis of rotational machinery is not an easy task since failure modes and machinery faults are diversified and they are not necessarily identical to past failure situations. In the medical context, diagnosis may sometimes be complicated as different patients have various illness conditions and disorder features that do not necessarily simulate historical patient databases.

Table 4.

Crucial outcomes and major obstacles related to SSL involvement in medical diagnosis.

5. Discussion

Supportive information and elaborative details on modern technologies and the latest innovations are integrated into SSL classification models to improve their potential and efficacy in monitoring various data recognition, forecasting, or distinguishing with perfect levels of precision and reliability. The discussion includes a critical explanation and evaluation of the following SSL-supportive technologies:

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN);

- Deep InfoMax (DIM);

- Pre-trained Language Models (PTM);

- Contrastive Predictive Coding (CPC);

- Autoencoder and its associated extensions.

5.1. Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN)

One category of DL architecture is the GAN. A GAN is commonly adopted to create new data based on the training process carried out by two neural networks, which compete with each other to generate the necessary authentic data. Images, movies, and text are examples of databases that can be handled and analyzed flexibly using the output of a GAN.

The concept of GANs was first addressed and investigated in an article published by [138]. An alternative paradigm for USL was created in their study, in which two neural networks were trained to compete with one another. Since then, GANs have emerged as powerful tools for generative modeling. Recently, GANs have proved essential in generative modeling, showcasing impressive skills.

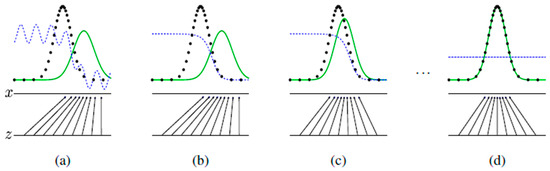

GANs have a significant influence on various activities, including improving data augmentation strategies, enhancing reinforcement learning algorithms, and strengthening SSL methodologies. GANs are a fundamental concept in modern ML, enabling progress in different fields due to their adaptability. Simultaneous training is conducted for GANs considering the update of the distinctive distribution, which can be expressed as a dashed blue line, , in Figure 16. Thus, this blue dashed line can distinguish between data samples related to the generative distribution, , , which is characterized by a solid green line. The horizontal line down the photo expresses the domain and a source of that can be uniformly sampled. At the same time, the horizontal line located in the upper area of the image indicates a part of the domain. The mapping of that equals , can impose the non-uniform distribution, , on transformed samples. In areas with higher density, G could contract and enlarge in zones with lower density levels that are correlated with [138].

Figure 16.

Configurations of (a) expresses a partial precise classifier and is identical to , (b) was converged to , (c) when was updated, the gradient helped to transfer to areas, which are approximately considered as data, and (d) when various training processes have been conducted, if both and have sufficient potential, they would attain a position in which they could not enhance since is identical to [138].

From Figure 16, can be expressed by the following formula:

5.2. Deep InfoMax (DIM)

This new concept was first introduced by [139], who conducted a numerical analysis to examine novel means of unsupervised learning of representations. Researchers have optimized encoding by decoding mutual information. They confirmed the importance of structure by showing how including information about the input locality in an aim can significantly enhance the fitness of a representation for subsequent tasks. Adversarial matching to a prior distribution allows researchers to control representational features.

DIM outperforms numerous well-known unsupervised learning approaches and is competitive with fully supervised learning in typical architectures across a variety of classification problems. Furthermore, according to the numerical analysis of these researchers, DIM paved the way for more creative formulations of representation learning objectives to address specific end goals, and it also provided new opportunities for the unsupervised learning of representations, particularly in addition to other vital DL models involving SSL and semi-supervised learning procedures [140,141]. The researcher has implemented a higher-level DIM concept to enhance information representation [142].

5.3. Pre-Trained Language Models (PTM)

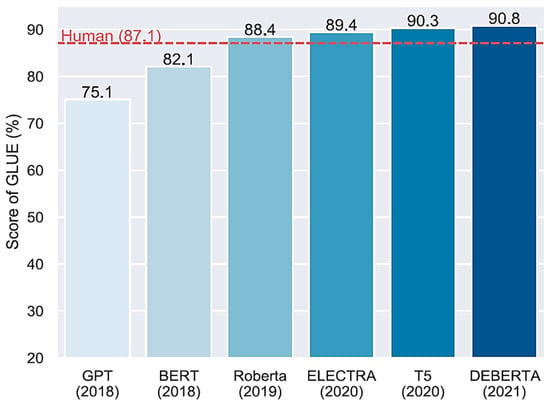

Regarding the beneficial merits of PTM for SSL models, Han et al. (2021) [143] explained that large-scale pre-trained language models (PTMs), such as BERT and generative pre-trained transformers (GPT), have become a benchmark in developing AI. Knowledge from large amounts of labeled and unlabeled data can be efficiently captured by large-scale PTMs owing to their advanced pretraining objectives and large model parameters. The rich knowledge implicitly contained in numerous parameters can help in a range of downstream activities, as has been thoroughly established through experimental verification and empirical analysis. This is achieved by storing knowledge in large parameters and fine-tuning the individual tasks. The AI community agrees that PTMs, rather than developing models from scratch, should serve as the foundation for subsequent tasks. In this study, they extensively examined the background of pre-training, focusing on its unique relationship with transfer learning and self-supervised learning, to show how pivotal PTMs are in the evolution of AI. In addition, the authors examined PTMs’ most recent developments in PTMs in depth. Advances in these four key areas—effective architecture design, context use, computing efficiency, interpretation, and theoretical analysis—have been made possible by the explosion in processing power and the growing availability of data. Figure 17 illustrates the time profile of the emergence of various language-understanding benchmarks linked to the PTM [143].

Figure 17.

Emergence of various language understanding benchmarks linked to PTM [143].

5.4. Contrastive Predictive Coding (CPC)

The CPC can be described as an approach implemented for SSL models to support them in understanding and learning representations in latent embedding spaces using autoregressive models. The CPC seeks to learn from a global, abstract representation of the signal rather than a high-dimensional, low-level representation [144].

Through further investigations on CPC, some scholars, such as [144], explored modified versions of CPC, which was CPCv2 to replace the auto-regressive aspects in the RNN model of CPC, taking into consideration CNN, helping promote the quality of the learned representations for image classification tasks [43,45,145,146].

Ye and Zhao employed CPC for the SSL-based intrusion detection system [147], as illustrated in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

An example of a CPC process adopted for SSL classification task. From Ref. [147], used under Creative Commons CC-BY license.

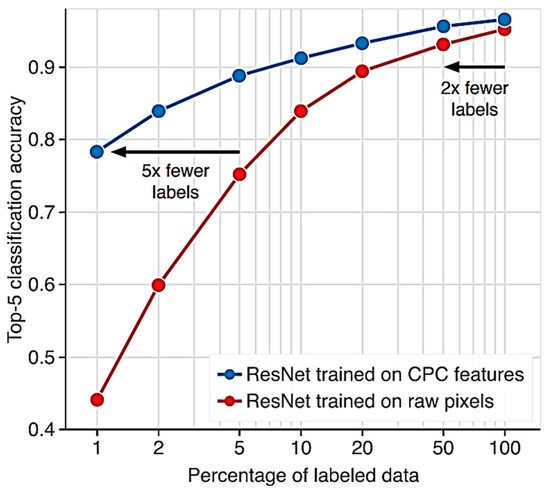

On the other hand, Henaff (2020) [145] elucidated some prominent merits of CPC in recognizing certain visual data more efficiently compared with SSL models that are trained by raw pixels, which can be explained in Figure 19. In this figure, when a low volume of labeled data is offered, trained SSL models based on raw pixels may fail to generalize, which is indicated by the red line. By training SSL models with the unsupervised representations that are learned by CPC, those models could retain considerable levels of precision within this lower data domain. Those trained SSL models can be expressed as a blue line in the same figure. The precision of SSL models could be attained with a remarkably lower number of labels, which are expressed with horizontal arrows.

Figure 19.

Involving CPC to recognize visual data efficiently [145].

5.5. Autoencoder and Its Associated Extensions

Autoencoders (AEs) and their corresponding extensions are other examples of modern techniques that enable the active implementation of SSL models. Some researchers, including Wang et al. (2020) [148], examined the beneficial impacts of autoencoder integration into the SSL classification task. They reported that by utilizing SSL models, single-channel speech could be enhanced by feeding the network with a noisy mixture and training it to output data closer to the ideal target.

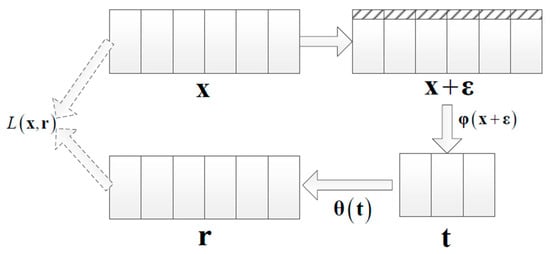

According to Jiang et al. (2017) [112], the AE seeks to learn the function, expressed by the following formula:

where is the input vector.

The AE learning action is correlated with two major phases: (a) encodering and (b) decoding. In the first phase, the encoder can map the vector, which expresses the data input, into a code vector. The latter can express the input. After this action, the decoder will try to utilize this code vector of the information input to restructure the input vector, providing a lower level of error. In their working principles, the decoder and encoder rely on ANN to complete their tasks. As a result, the output target pertaining to the AE would express the AE itself. The major configurations of the encoder and decoder in the AE could be expressed, respectively, as follows:

where . expresses the sample number of the raw data. , where is sample vector. , and it expresses the pattern or code taken from . . . expresses the weight matrix and bias level between the hidden layer (layer No. 2) and the input layer (layer No. 1). and . indicates the bias existing between layers two and three. is the weight matrix between those two layers as well.

From Figure 20, L(x,r) is the squared error, is the reconstruction function. is the projection function that can map the input to the feature space. expresses a vector through which each index is independent and behaves similarly to the Gaussian distribution that has a variance, .

Figure 20.

An extensive training process conducted for [112].

6. Conclusions

This study was carried out in response to the poor classification robustness and weak categorization efficiency of conventional DL and ML models and even modern DL algorithms that have been involved recently in medicine and industry to conduct practical prediction processes. However, because of the huge cost, effort, and time corresponding to data annotation in those two domains, the ML and DL prediction procedures would be considerably challenging. Remarkable R&D revealed a noteworthy SSL that was evolved to enable flexible and efficient classification without referring to arduous data annotation. In addition, SSL was created to overcome another problem reflected in the variating trends and behavior of new data that do not necessarily simulate past documented data. Therefore, when data annotation is fully applied, ML and DL models may not provide important prediction outcomes or classification capabilities.

To shed light on the constructive benefits and substantial contributions of SSL models in facilitating prediction tasks, this paper adopted a comprehensive overview through which variant efficacious applications of two necessary scientific fields were explored, including (a) industry and manufacturing and (b) medicine. Within those two domains, industrial engineers and healthcare providers encounter repetitive obstacles in predicting certain types of faults in machines and ailment situations in patients, respectively. As illustrated here, even if historical databases of machine fault behavior and patient disorders are fully annotated, most ML and DL models fail to perform precise data identification. Relying on the thorough overview implemented in this article, the imperative research findings can be summarized in the following aspects:

- Involving SSL algorithms in industrial engineering and clinical contexts could support manufacturing engineers and therapists in carrying out efficient classification procedures and predictions of the current machine fault and patient problems with remarkable levels of performance, accuracy, and feasibility.

- Profitable savings in the computational budget, time, storage, and effort needed in the annotation and training of unlabeled data can be eliminated when SSL is utilized, maintaining approximately optimum prediction efficacy.

- Functional human thinking, learning approaches, and cognition are utilized in SSL models, contributing to upgraded machine classification and computer prediction outcomes correlated with different fields.

7. Future Work

Based on the statistical numerical outcomes and noteworthy ideas obtained from the extensive overview in this paper, the current work proposes some crucial future work perspectives and essential ideas that can help promote SSL prediction potential. The remarkable suggestions that can be taken into consideration are as follows:

- To review the importance of SSL in carrying out accurate predictions pertaining to other scientific domains.

- To overcome some problems not addressed carefully in the literature encountering most SSL models, reflected in SSL trials, analyze and take into consideration solely semantic characteristics linked to the investigated dataset. They do not benefit from critical features existing in visual medical databases.

- To classify other crucial applications of SSL, including either recognition or categorization, not correlated with the relevance of the predictions addressed in this paper.

- To identify other remarkable profitabilities and workable practicalities of SSL other than their contributions to cutting much computational time, budget, and effort for necessary data annotation in the same prediction context.

- To expand this overview with a few case studies in which contributory SSL predictions are carefully explained.

8. Research Limitations

In spite of the successful achievement of the meta-analysis and thorough review of various robust SSL applications in industrial and medical contexts, the study encountered a few research constraints that restricted the broad implementation of the extensive review. Those limitations are translated into the following aspects:

- Some newly published academic papers (more than 2022) have no direct access to download the overall document. Additionally, some web journals do not have full access to researchers, even for oldly published papers. For this reason, the only extracted data from those articles were the abstract.

- There is a lack of abundant databases correlated with the direct applications involved in SSL in machinery prognostics and medical diagnosis.

- There were no direct explanations or abundant classifications of major SSL limitations that needed to be addressed and handled.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.A., N.T.A.R., N.L.F., M.S. (Muhammad Syafrudin), and S.W.L.; methodology, M.M.A., N.T.A.R., N.L.F., M.S. (Muhammad Syafrudin) and S.W.L.; validation, M.M.A., N.T.A.R., A.A.H. and M.S. (Mohammad Salman); formal analysis, N.L.F., D.K.Y. and S.W.L.; investigation, D.K.Y., N.L.F., M.S. (Muhammad Syafrudin) and S.W.L.; data curation, M.M.A., N.T.A.R., A.A.H. and M.S. (Mohammad Salman); writing—original draft preparation, M.M.A., N.T.A.R., A.A.H. and M.S. (Mohammad Salman); writing—review and editing, D.K.Y., N.L.F., M.S. (Muhammad Syafrudin) and S.W.L.; funding acquisition, M.S. (Muhammad Syafrudin) and S.W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant number: NRF2021R1I1A2059735).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AE | Autoencoder |

| AP | Average Precision |

| APC | Autoregressive Predictive Coding |

| AUCs | Area under the Curve |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BoW | Bag-of-Visual-Words |

| BYOL | Bootstrap Your Own Latent |

| CaiD | Context-Aware instance Discrimination |

| CERT | Contrastive self-supervised Encoder Representations through Transformers |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CPC | Contrastive Predictive Coding |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DCL | Dense Contrastive Learning |

| DIM | Deep InfoMax |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DSC | Dice Similarity Coefficient |

| EHRs | Electronic Health Records |

| EMA | Exponentially Moving Average |

| EVs | Electric Vehicles |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, And Air-Conditioning |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| Li-ion | Lithium-ion |

| LMLM | Label-Masked Language Model |

| LMs | Language Models |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean-Absolute-Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLC | Multi-Layer Classifiers |

| MLM | Masked Language Model |

| MoCo | Momentum Contrast |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MPQA | Multi-Perspective Question Answering |

| MRs | Movie Reviews |

| MSAs | Multiple Sequence Alignments |

| NAIP | National Agricul-ture Imagery Pro-gram |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| NSA | Natural Synthetic Anomalies |

| PdL | Predictive Learning |

| pLMs | protein LMs |

| PPG | Phoneme Posteriororgram |

| PTM | Pre-trained Language Models |

| PxL | Pretext Learning |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square-Error |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| SL | Supervised Learning |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| SSEDD | Self-Supervised Efficient Defect Detector |

| SSL | Self-Supervised Learning |

| SST2 | Stanford Sentiment Treebank-2 |

| SwAV | Swapping Assignments across Views |

| TREC | Text Retrieval Conference |

| USL | Unsupervised Learning |

| VAE | Variational Auto-Encoders |

| VC | Voice Conversion |

| VICReg | Variance, Invariance, and Covariance Regularization |

References

- Lai, Y. A Comparison of Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Image Recognition. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1314, 012148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeianjouybari, B.; Shang, Y. Deep learning for prognostics and health management: State of the art, challenges, and opportunities. Measurement 2020, 163, 107929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoppil, N.M.; Vasu, V.; Rao, C.S.P. Deep Learning Algorithms for Machinery Health Prognostics Using Time-Series Data: A Review. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 1123–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Wei, M. A Review on Deep Learning Applications in Prognostics and Health Management. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 162415–162438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Nguyen, K.T.P.; Medjaher, K.; Gogu, C.; Morio, J. Bearings RUL prediction based on contrastive self-supervised learning. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 11906–11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrim, A.; Gogu, C.; Vingerhoeds, R.; Salaün, M. Self-Supervised Learning for data scarcity in a fatigue damage prognostic problem. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 120, 105837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Jia, M.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, X. Health Assessment of Rotating Equipment with Unseen Conditions Using Adversarial Domain Generalization Toward Self-Supervised Regularization Learning. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 4675–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez, I.; Doelling, R.; Bringmann, O. Self-supervised Multi-stage Estimation of Remaining Useful Life for Electric Drive Units. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; IEEE: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 4402–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hahn, T.; Mechefske, C.K. Self-supervised learning for tool wear monitoring with a disentangled-variational-autoencoder. Int. J. Hydromechatronics 2021, 4, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Guan, C. A self-supervised contrastive learning framework with the nearest neighbors matching for the fault diagnosis of marine machinery. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 270, 113437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Tian, Y. Self-Supervised Visual Feature Learning with Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 4037–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhao, L.; Huang, X.; Huang, W.; Ding, J.; Yao, Y.; Xu, L.; Yang, P.; Yang, G. Self-supervised knowledge mining from unlabeled data for bearing fault diagnosis under limited annotations. Measurement 2023, 220, 113387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Rosenthal, J.; Waring, J.; Umeton, R. Applying Self-Supervised Learning to Medicine: Review of the State of the Art and Medical Implementations. Informatics 2021, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadif, M.; Role, F. Unsupervised and self-supervised deep learning approaches for biomedical text mining. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 1592–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhou, M.; Ding, J.; Xie, P. Cert: Contrastive self-supervised learning for language understanding. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.12766. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, A.; Babu, A.R.; Zadeh, M.Z.; Banerjee, D.; Makedon, F. A Survey on Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning. Technologies 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurrab, S.; Duwairi, R. Self-supervised learning methods and applications in medical imaging analysis: A survey. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohri, K.; Kumar, M. Review on self-supervised image recognition using deep neural networks. Knowl. Based Syst. 2021, 224, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Carass, A.; Zuo, L.; Dewey, B.E.; Prince, J.L. Autoencoder based self-supervised test-time adaptation for medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 72, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.-C.; Pareek, A.; Jensen, M.; Lungren, M.P.; Yeung, S.; Chaudhari, A.S. Self-supervised learning for medical image classification: A systematic review and implementation guidelines. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Yoon, G.; Song, J.; Yoon, S.M. Self-supervised deep geometric subspace clustering network. Inf. Sci. 2022, 610, r235–r245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mu, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Zong, L.; Li, Y. Deep anomaly detection with self-supervised learning and adversarial training. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 121, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciga, O.; Xu, T.; Martel, A.L. Self supervised contrastive learning for digital histopathology. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2022, 7, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wu, H.; Han, W.; Li, C.; Chen, H. Joint optimization of autoencoder and Self-Supervised Classifier: Anomaly detection of strawberries using hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Liu, X.; Cen, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, C.; Tang, J. GraphMAE: Self-Supervised Masked Graph Autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 14–18 August 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lao, Q.; Kang, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Du, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, K. Self-supervised anomaly detection, staging and segmentation for retinal images. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 87, 102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Chen, G.; Liu, S. Multi-scale graph attention subspace clustering network. Neurocomputing 2021, 459, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, W.; Han, M. Variational auto-encoders based on the shift correction for imputation of specific missing in multivariate time series. Measurement 2021, 186, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. HAT-GAE: Self-Supervised Graph Auto-encoders with Hierarchical Adaptive Masking and Trainable Corruption. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.12063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Ernest N. Morial Convention Center: New Orleans, LA, USA; IEEE: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 16000–16009. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekri, M.N.; Ghosh, A.M.; Grolinger, K. Generating Energy Data for Machine Learning with Recurrent Generative Adversarial Networks. Energies 2019, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]