Abstract

A certain Grothendieck topology assigned to a metric space gives rise to a sheaf cohomology theory which sees the coarse structure of the space. Already constant coefficients produce interesting cohomology groups. In degree 0, they see the number of ends of the space. In this paper, a resolution of the constant sheaf via cochains is developed. It serves to be a valuable tool for computing cohomology. In addition, coarse homotopy invariance of coarse cohomology with constant coefficients is established. This property can be used to compute cohomology of Riemannian manifolds. The Higson corona of a proper metric space is shown to reflect sheaves and sheaf cohomology. Thus, we can use topological tools on compact Hausdorff spaces in our computations. In particular, if the asymptotic dimension of a proper metric space is finite, then higher cohomology groups vanish. We compute a few examples. As it turns out, finite abelian groups are best suited as coefficients on finitely generated groups.

Keywords:

coarse geometry; sheaf cohomology; Grothendieck site; Higson corona; Roe coarse cohomology MSC:

51F30; 55N30

1. Introduction

The sheaf-theoretic approach to coarse metric spaces has been applied in many different contexts [1,2,3]. Sheaf-theoretic methods play an important role in our paper. We also present three other computational tools. Cochain complexes assigned to a filtration of Vietoris–Rips complexes have not just been used in the coarse setting [4]. Many well-known coarse (co-)homology theories are coarse homotopy invariant [5,6,7]. The cohomology of the Higson corona is of course as a composition of functors a coarse invariant which has been studied before [8]. Even in combination with other computational methods [9], coarse invariants are hard to compute for the spaces one is most interested in, which include Riemannian manifolds and finitely generated groups.

Coarse sheaf cohomology has been designed by the author in her thesis. Aside from an agenda to present new computational methods which may be suitable for a large number of spaces, there are two immediate results:

Theorem 1.

If M is a non-positively curved closed Riemannian n-manifold and A a finite abelian group, then

the left side denotes coarse sheaf cohomology with values in the constant sheaf A and the right side denotes singular cohomology with values in the group A.

This result can be immediately applied to define a coarse version of mapping degree associated to a coarse map between manifolds.

Theorem 2.

If T is a simplicial tree with infinitely many ends and A is a finite abelian group, then

There are many interesting cohomology theories on coarse metric spaces. The most prominent examples are Roe’s coarse cohomology [10,11,12] and controlled operator K-theory [13,14,15,16]. If two metric spaces have the same coarse type, then specifying a coarse equivalence is a proof. If on the other hand do not have the same coarse type, then a coarse invariant which does not have the same values on X and Y gives a proof. In general, a well-designed cohomology theory delivers a rich source of invariants which are easy to compute. To this date, cohomology of finitely generated free abelian groups has been calculated for Roe’s coarse cohomology and also controlled operator K-theory. There is still a gap in knowledge about cohomology of other finitely generated groups. Riemannian manifolds on the other hand do not show interesting cohomology groups since every Riemannian n-manifold with nonpositive sectional curvature is coarsely homotopic to and most coarse cohomology theories are coarse homotopy invariant [10].

Our coarse cohomology theory is a sheaf cohomology theory on a Grothendieck topology assigned to a metric space X [17]. If A is an abelian group, then for the constant sheaf A on X we obtain in dimension 0 a copy of A for every end of X or an infinite direct sum of copies of A if X does not have finitely many ends [17].

In this paper, we design a cochain complex assigned to a metric space X and abelian group A. The functor forms a flabby sheaf on . The sequence of sheaves

is exact. Thus, cohomology of

computes coarse sheaf cohomology of X with values in .

Theorem 3.

If X is a metric space, then there is a flabby resolution of the constant sheaf on . We can compute sheaf cohomology with values in the constant sheaf using cochain complexes:

For , there is a comparison map with Roe coarse cohomology. This map is neither injective nor surjective though. The main difference is that our cochains are defined as maps that need to be “blocky” while coarse cochains do not have this restriction. Thus, general statements on cohomology are easier to prove for Roe coarse cohomology, while we hope that combinatorical computations are easier realized using blocky cochains.

There are several notions of homotopy on the coarse category which are all equivalent in some way. The homotopy theory we are going to employ uses the asymptotic product as coarse substitute for a product and the first quadrant in equipped with the Manhattan metric as a coarse substitute for an interval [18]. In effect, this homotopy theory and the other coarse homotopy theories are only of use if one wants to compute cohomology of and maybe Riemannian manifolds. Nonetheless, we prove that coarse sheaf cohomology is a coarse homotopy invariant using the resolution via cochains.

Theorem 4.

If two coarse maps between metric spaces are coarsely homotopic, then they induce the same map

in cohomology with values in a constant sheaf A.

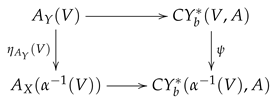

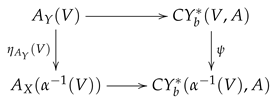

A coarse map between metric spaces induces a cochain map which in turn induces a homomorphism . Conversely, the inverse image functor maps the constant sheaf on to the constant sheaf on . Thus, there is an induced homomorphism in cohomology. One may wonder if both homomorphisms coincide, and indeed they do.

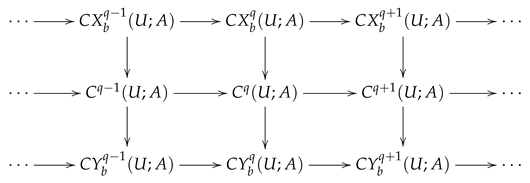

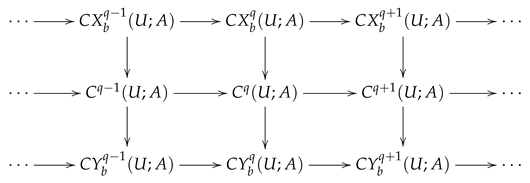

To a proper metric space X we can assign a compact Hausdorff topological space , the Higson corona of X. This version of boundary reflects sheaf cohomology in the following way: There is a functor which maps a sheaf on to a sheaf on . Conversely, the functor maps a sheaf on to a sheaf on , Together, they provide an equivalence of categories between “reflective” sheaves on and sheaves on . In particular, the constant sheaf on is reflective and mapped to the constant sheaf on . We can compute cohomology with constant coefficients either way:

Theorem 5.

If X is a proper metric space and A an abelian group, then

the qth cohomology of X with values in the constant sheaf A on is isomorphic to the qth sheaf cohomology of the Higson corona of X with values in the constant sheaf .

Moreover, if asdim then for .

This paper provides enough computational methods to compute metric cohomology of finitely generated groups. Vanishing of for finite A can be computed directly using cochains. Then, our result on the Higson corona implies that is acyclic for finite coefficients. The same method can be employed to show that trees are acyclic for finite coefficients. Thus, we computed metric cohomology of the free group with generators. Computing cohomology of the free abelian groups with is more challenging. A coarse homotopy equivalence provides a Leray cover of which has the same combinatorical information as the nerve of a Leray cover of the topological space . Thus, cohomology with finite coefficients can be derived.

Theorem 6.

If A is a finite abelian group, then

There is a more general notion of coarse space which includes the class of coarse metric spaces. Most of our concepts work in more generality. We restrict our attention to metric spaces only since a wider audience (than coarse geometers) is interested in this class of coarse spaces only. The coarse sheaf cohomology theory is defined on coarse spaces with connected coarse structure. The resolution via cochains also works for this class of spaces. The homotopy theory is only defined for metric spaces and the results on the Higson corona work for proper metric spaces and coarse structures generated by a compactification of a paracompact, locally compact Hausdorff space.

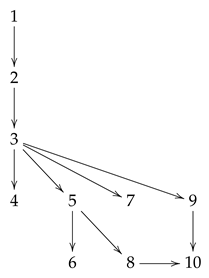

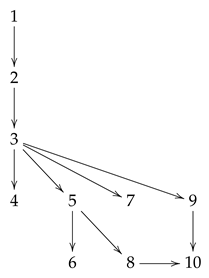

This article is organized in 10 sections. Some can be read independently but there are also a few dependencies as depicted in the following diagram.

The final section uses every aspect so far discussed. Sheaf-theoretic methods, the resolution via cochains, coarse homotopy and the Higson corona are employed in the computation of metric cohomology of .

2. Coarse Cohomology by Roe and the Higson Corona

This chapter introduces terminology and concepts which are well known to coarse geometers.

If X is a metric space, then a subset is called an entourage if

The set of entourages forms the coarse structure of X. If , then the set

is an entourage. If are two subsets, then

A subset is called bounded if there exists and such that .

A map between metric spaces is called coarsely uniform if for every there exists such that in X implies in Y. The map is called coarsely proper if for every bounded set the set is bounded in X. The map is called coarse if is both coarsely uniform and coarsely proper. Two maps between metric spaces are called close if the set is an entourage in Y. The coarse category consists of metric spaces as objects and coarse maps modulo close as morphisms. Isomorphisms in this category are called coarse equivalences.

This paper presents a resolution of the constant sheaf which consists of cochains which closely resemble coarse cochains of Roe’s coarse cohomology. For this purpose, we give a quick introduction to coarse cohomology by Roe which was invented by Roe in [10,11].

If X is a metric space, then the set of q-simplices of the R-Vietoris–Rips complex of X is defined as

A subset is called bounded if the projection to every factor is bounded. Then, a subset is called cocontrolled if for every the set is bounded.

Definition 1.

If X is a metric space and A an abelian group, then the coarse cochains is the set of functions with cocontrolled support. It is a group by pointwise addition. The coboundary map is defined by

This makes a cochain complex. Its homology is called coarse cohomology by Roe and denoted by .

If is a coarse map, then it induces a cochain map

Two coarse maps which are close induce the same map in cohomology. If and , then

A section in this paper transfers sheaves on a proper metric space to sheaves on its Higson corona. For this purpose, we give a definition of the Higson corona which is equivalent to the usual one [19].

Let X be a metric space. Two subsets are called close (or not coarsely disjoint) if there exists an unbounded sequence and some such that for every i. We write in this case.

A metric space is called locally finite if every bounded set is finite. Every proper metric space is coarsely equivalent to a locally finite metric space.

Definition 2.

Let X be a proper metric space and a locally finite subset where the inclusion is coarsely surjective. Denote by the set of nonprincipal ultrafilters on S. If is a subset, define

Then, define a relation ⋏ on subsets of : if for every the relations imply .

The relation ⋏ on subsets of determines a Kuratowski closure operator

Now, define a relation λ on : if implies .

Now, the Higson corona of X is defined as the quotient by λ.

If is a subset of a metric space, then where the closure is taken in the Higson compactification. We call the basic open sets and the basic closed sets. There are two observations: If are two subsets, then

- if and only if are not close

- .

3. Coarse Sheaf Cohomology, a Survey

This chapter gives a survey on coarse sheaf cohomology or coarse cohomology with twisted coefficients as we call it [17]. There are several facts on sheaf cohomology on topological spaces which hold in more generality for sheaf cohomology defined on a Grothendieck topology. Since the literature does not provide every aspect, we are going to prove these facts by hand.

Let be a subset of a metric space. A finite family of subsets forms a coarse cover of U if for every entourage the set

is bounded. This is equivalent to saying that the set

is a cocontrolled subset of .

To a metric space X we associate a Grothendieck topology in the following way. The underlying category is the poset of subsets of X. Subsets form a covering of if they coarsely cover U.

A contravariant functor on subsets of X is a sheaf on if for every coarse cover of a subset of X the following diagram is an equalizer

If is a sheaf on then the right derived functor of the global sections functor is called coarse sheaf cohomology, written .

If

is a short exact sequence of sheaves on then there is a long exact sequence in cohomology

If A is an abelian group, the sheafification of the constant presheaf A on is called the constant sheaf on X. In this paper, we are interested in the computation of in higher dimension. The zeroth cohomology group is related to the number of ends of the metric space X:

A sheaf on is called acyclic if for . A sequence of sheaves

is exact if . Here, is the sheafification of the image presheaf .

Lemma 1.

If

is an acyclic resolution of sheaves on then

cohomology of can be computed by taking homology of the cocomplex

Proof.

Suppose

is an exact sequence with acyclic for every i.

For every define . The exact sequence

gives rise to a long exact sequence

Thus, for and

The inclusion and the corestriction of to combine to an exact sequence

This sequence gives rise to a long exact sequence

which reads for . If , then we obtain inductively

□

Lemma 2.

If X is a metric space, every injective sheaf on is flabby.

Proof.

Let be an injective sheaf on and let be an inclusion of subsets. We define a presheaf on by

Denote by the sheafification. In a similar way, we define and . Then, is a subsheaf in a canonical way. Thus, we have an exact sequence

Since is an injective object the sequence

is exact. Now

and

which proves the claim. □

Lemma 3.

If X is a metric space, then flabby sheaves on are acyclic.

Proof.

We mimic the proof of ([20], Proposition 2.5).

If is a flabby sheaf, then it can be embedded in an injective sheaf . The quotient of this inclusion is denoted . Then, we have an exact sequence

with flabby, flabby by Lemma 2 and is flabby by a standard argument. General theory on flabby sheaves also implies that the sequence

is exact. Then, the long exact sequence in cohomology to the short exact sequence (2), the exactness of (3) and for implies and

for . Since satisfies the requirements for this Lemma, we obtain the result for using inductively and the isomorphism (4). □

4. Standard Resolution

This chapter proves Theorem 3.

Let A be an abelian group. If is a disjoint union of a subset of a metric space, then

Then, we define

where the indexing category consists of pairwise disjoint subsets with . There is an arrow if is a refinement of . Then is equivalent to if

for every . We equip with a group operation by pointwise addition. The elements of are called blocky functions with blocks . They can be compared with the group of all functions .

A differential on is defined by

Now, defines the subcomplex of functions in with cocontrolled support. Then, we define .

Definition 3.

If X is a metric space, A an abelian group and then coarse cohomology is defined to be the qth homology of the coarse cochain complex .

Subsets of a subset of a metric space form a coarse disjoint union of U if they coarsely cover U and every two elements are disjoint.

Lemma 4.

If is a subset of a metric space and A an abelian group, then

Proof.

We compute . Let be a cocycle. Then, if defines an equivalence relation on X with equivalence classes . The form a coarse disjoint union since has cocontrolled support. We can assume all are not bounded otherwise we subtract a cochain with bounded (cocontrolled) support. Thus, is an element of .

If we are given a coarse disjoint union of U and then we can assume the are disjoint and not bounded. Then,

defines a cocycle in . □

If is a coarse map between metric spaces and a cochain, then defines a cochain in , specifically is mapped to . If has cocontrolled support, so does . Thus, there is a well-defined cochain map .

In particular, an inclusion of subsets induces a restriction map . Thus, forms a presheaf on .

Lemma 5.

If X is a metric space, the presheaf is sheaf on .

Proof.

Let be a coarse cover of a subset . We show the identity axiom. Let be a section with for every i. By Lemma 6, the set is cocontrolled. Then

as a finite sum of functions with cocontrolled support has cocontrolled support.

We show the gluing axiom. Suppose are functions with for every . Define a function

If then . As can easily be seen, the cochain restricts to for every i. □

Lemma 6.

If and are a coarse cover of a subset of a metric space then

is bounded.

Proof.

If is a function, then denote

Here, the empty intersection denotes U. Then,

Now, the projection to the ith factor of is

bounded. Since is a finite union of the this proves the claim. □

Lemma 7.

The sheaf on is flabby.

Proof.

If is an inclusion of subsets and then there is a disjoint union with . Define

Then, restricts to on U. □

Lemma 8.

The homology of is concentrated in degree zero.

Proof.

We compute . If then

If and then define the cochain

Here, is a fixed point. If then . Then

Thus, higher homology of vanishes. □

We note an exact sequence of cochain complexes:

Lemma 9.

If and for every subset and there exists a coarse cover of U and with then is exact at q.

Proof.

Let be an element. Then, has cocontrolled support; thus, it is an element of . Since the element is even a cocycle in . Then, there exists a coarse cover and elements with . Then, is a cocycle in for every i. Thus, there exists with . Thus, represents a coboundary. □

Lemma 10.

If and is cocontrolled in then is a coarse cover of U.

Proof.

Let be a number. If then . Since this set is bounded, must be contained in a bounded set too. □

Lemma 11.

If is a cocycle, then there exists a coarse cover of U with for every .

Proof.

Suppose and fix for every i. Then is bounded if . We add i to a list . Likewise, is cocontrolled if there exists a map with . We add the set to the list . We proceed likewise with of up to factors. We then define

We show is the desired coarse cover.

If then it is of the form . Let be a function. Since we have . Thus . Since f was arbitrary this implies .

If then . Thus there exists a subset with . Which implies that is cocontrolled. This way we showed that is cocontrolled in . By Lemma 10 we can conclude that is a coarse cover. □

Theorem 7.

If X is a metric space and A an abelian group then the are a flabby resolution of the constant sheaf A on . We can compute

for every .

Proof.

We prove that

is a flabby resolution of A. By Lemma 5, the are sheaves. They are flabby by Lemma 7. By Lemma 4, the sequence is exact at 0. If we combine Lemmas 9 and 11, then we see that it is exact for . □

5. Functoriality, Graded Ring Structure and Mayer–Vietoris

This chapter presents a few immediate applications of Theorem 3.

Lemma 12.

If two coarse maps are close then they induce the same map in cohomology.

Proof.

The chain homotopy for coarse cohomology presented in ([11], Proposition 5.12) can be costumized for our setting. Define a map by

If then . Since are close, cocontrolled support of implies cocontrolled support of . Thus, h is well-defined.

The combinatorical calculation presented in the proof of ([11], Proposition 5.12) shows that

Thus are cochain homotopic. □

Throughout this section, X denotes a metric space and R a commutative ring.

We define a map on cochains

with

Lemma 13.

This product ∨ is well-defined.

Proof.

We show has cocontrolled support if one of does.

Suppose has cocontrolled support. Then, is bounded for every . This implies the 0th factor is bounded. If , then the ith factor

is bounded. This proves the claim. □

The formula

is easy to check. From that, we deduce that the ∨-product of two cocycles is a cocycle and the product of a cocycle with a coboundary is a coboundary. Thus, ∨ gives rise to a cup-product ∪ on . Associativity and the distributive law can be checked on cochain level. This makes a graded ring.

Theorem 8.

(Mayer–Vietoris) If is a coarse cover of a metric space X, then there is a long exact sequence in cohomology

Proof.

We examine a sequence of cocomplexes

Here, is defined by and by . This sequence is exact at and since is a sheaf on and are a coarse cover of X. It is exact at since is a flabby sheaf.

The result is obtained by taking the long exact sequence in cohomology of the exact sequence of cochain complexes. □

We denote by the qth homology group of the cochain complex given a metric space X and an abelian group A.

Proposition 1.

Let X be a metric space and A an abelian group. Then,

and

for every .

Proof.

Suppose . An element of is a constant function. If X is bounded, every constant function represents an element of . If X is not bounded, then every constant function with bounded (cocontrolled) support must be zero.

If , we use the short exact sequence of cochain complexes

This splits since every element of is represented by a blocky map .

Now we produce the long exact sequence in cohomology. The first few terms are

If X is bounded then, this reads

Thus, . If X is not bounded, then the first few terms of the long exact sequence in cohomology read

Then

In the middle term, we mod out the constant functions.

For , the long exact in cohomology reads

Thus we proved the claimed results. □

6. Computations

Theorem 3 can also be applied to compute cohomology groups in a combinatorical manner.

Lemma 14.

If A is a finite abelian group, then .

Proof.

If then has cocontrolled support. This means for every the set is bounded. This amounts to saying that the function

has finite support . Then define

This function is blocky since assumes only finitely many values. Here, we use that A is finite. Moreover, we have

This shows that has cocontrolled support. Thus is a coboundary in . □

Theorem 9.

If T is a tree and A is a finite abelian group then

Proof.

Designate an element as the root of the tree and define

Let be a cocycle. Then for every , there is a unique 1-path joining to s. Define

Let be a number. If and then there exist paths joining to t and joining to s with or depending on whether or is a 1-path joining t to s. Then

is a would-be cocycle in ; thus, it has bounded support. Thus, we showed is a coboundary.

Since the inclusion is coarsely surjective, we can conclude . □

We will compute the following example later in more detail. This version of the proof is more combinatorical though.

Lemma 15.

If is the free abelian group on two generators, then ; indeed, the first cohomology group contains a copy of .

Proof.

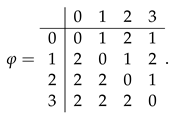

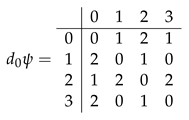

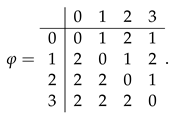

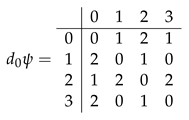

We divide into 4 quadrants: . Fix points . We define a cocycle by

Among other equations, we obtain and . Thus, and lie in the support of . Since and are cocontrolled, this is okay. Checking the other finitely many equations, we obtain that does indeed have cocontrolled support. Thus, is indeed a cocycle. We show that is not a coboundary. Suppose for contradiction that with and . First we show . Suppose for contradiction and while does not take the value k. Then, . Since this implies is contained in the support of and therefore is cocontrolled. Since is one-ended, this is a contradiction. Now, we construct . Suppose . Since is not cocontrolled, we obtain and similarly . Since is not cocontrolled, we obtain . Then

Among other equations, we obtain and . Thus, and lie in the support of . Since and are cocontrolled, this is okay. Checking the other finitely many equations, we obtain that does indeed have cocontrolled support. Thus, is indeed a cocycle. We show that is not a coboundary. Suppose for contradiction that with and . First we show . Suppose for contradiction and while does not take the value k. Then, . Since this implies is contained in the support of and therefore is cocontrolled. Since is one-ended, this is a contradiction. Now, we construct . Suppose . Since is not cocontrolled, we obtain and similarly . Since is not cocontrolled, we obtain . Then

If we compare the tables, we see that does not have cocontrolled support. Thus, is a proper cocycle. □

If we compare the tables, we see that does not have cocontrolled support. Thus, is a proper cocycle. □

7. Infinite Coefficients

The computations in Section 6 only work for finite coefficients. This chapter shows that the coefficient does not produce interesting cohomology groups.

If X is a proper metric space and A a metric space denoted by the abelian group of Higson functions modulo functions with bounded support. Namely, a bounded function is called Higson if for every entourage and every there exists a compact subset such that implies .

Lemma 16.

If X is a proper R-discrete for some metric space and A a metric space then for with the obvious restriction maps is a sheaf on .

Proof.

Let be a coarse cover of a subspace .

We prove the base identity axiom. Let be an element. If have bounded support then has support contained in the set

which is a finite union of bounded sets and therefore itself bounded. Thus, has bounded support.

Now, we prove the gluing axiom. Suppose there are functions with for every . Then, define a function

which restricts to on each . Here, is any choice of point. Now is continuous since U is R-discrete. The image of

is bounded. Now, we check the Higson property. If is an entourage, then

where is bounded. Let be a number. Then for each i, there exists a bounded subset with for each . Now define . Then for each . Thus, satisfies the Higson property. □

Denote by the abelian group of Freudenthal functions modulo functions with bounded support. Namely, a bounded function is called Freudenthal if for every entourage , there exists a compact subset such that implies .

Lemma 17.

If X is a proper metric space and A is a countable abelian group, then the constant sheaf A on is isomorphic to which is isomorphic to .

Proof.

For each we show that the inclusion is bijective. Let be an element. We show that is Freudenthal. Let be an entourage and choose . Then, there exists a bounded set with for each . Since A is 1-discrete, this implies for each . Thus is Freudenthal.

Now, we show the constant sheaf A is isomorphic to . We define a homomorphism . If then it can be written corresponding to a coarse disjoint union . Then, we define

The are Higson and glue to a Higson function . If is another element represented by corresponding to then is represented by corresponding to . Without loss of generality, the are pairwise disjoint and cover U and likewise, the are pairwise disjoint and cover U. Then,

Thus, is a homomorphism. We show that is well defined. Suppose is represented by 0 on where B is finite. Then has bounded support. Thus, is well defined.

Now, we construct the inverse . If is Freudenthal, then in particular its image is finite. Since is Higson, the are a pairwise coarsely disjoint union of U. Then, define to be the element represented by corresponding to . It is mapped by to . Thus, is surjective. Now, we show is injective: If has bounded support B then is represented by 0 on . □

Proposition 2.

If X is a proper metric space, the following sequence of sheaves on is exact:

Proof.

Let be a subset.

The map is induced by the inclusion . This map is well defined since every Freudenthal function is Higson. It is injective. Thus exactness at is guaranteed.

The map is induced by the quotient map . A Higson function is in the kernel of this map exactly when its image is contained in . Thus, exactness at is ensured.

Now we show exactness at . Let be a function. Its image is covered by . Since

we obtain that are coarsely disjoint. Thus, are a coarse cover of U. Now we describe a lift of : If then is defined to be the representative of in the interval . A lift of is obtained by defining to be the representative of in the interval . Thus, the right morphism in the diagram is surjective. □

Lemma 18.

If X is a proper metric space, the sheaf is flabby.

Proof.

Let be a subset. Since is a subset, the closure of A in is a compactification generated by . Now, is equivalent (as a compactification) to and thus also generated by . Since both and separate points from closed sets, they are both contained in , the algebra of bounded functions on A which extend to ([21], Proposition 2). The ([21], Proposition 2) also states that is the smallest unital, closed -algebra with this property. Since both and are unital, closed the equality

holds.

We provide another proof using the Tietze extension theorem. If an element in is represented by then it extends to on . By the Tietze extension theorem, we can extend to a bounded function on . Then, represents an element in that restricts to . □

Example 1.

We show is flabby on the specific example constructing a concrete global lift of a Higson function on a subspace of . If then there are with the largest number in U with and the smallest number in U with . Define

This function is Higson: If then there exists an with for every with and . If with then

provided .

Remark 1.

By the long exact sequence in cohomology, we obtain

If we can define

This function satisfies the Higson condition but is not bounded. Post-composition with the projection gives a Higson function which does not have a lift. Compare this result with [8].

Remark 2.

It would be great if we could find an algorithm that computes coarse cohomology with constant coefficients of a finitely presented group. This does not work even in degree 0. If we could decide whether vanishes, then we can decide whether G is finite. This is in general not decidable.

8. The Inverse Image Functor

In this section, we fix a coarse map between metric spaces.

If is a sheaf on then the inverse image (or pullback sheaf) is the sheafification of the presheaf on which assigns with .

Conversely, if is a sheaf on then the direct image is the sheaf on which assigns to .

Lemma 19.

The functor is left adjoint to . The functor is left exact and the functor is exact. The functor maps injectives to injectives.

Proof.

The functor

is a morphism of Grothendieck topologies and therefore gives rise to functors between categories of presheaves ([22], Chapter I,2.3). The functor maps a presheaf on to the presheaf on . is defined in ([22], Theorem I,2.3.1). If is a presheaf on and we define : Consider all with . They form a category . Then,

since is the initial object in .

Then ([22], Chapter I,3.6) discusses functors and between categories of sheaves. We obtain the direct image functor and the inverse image functor . Then ([22], Proposition I,3.6.2) implies that is left adjoint to , the functor is left exact and if is actually exact then the functor maps injectives to injectives. It remains to show that is exact. By ([22], Proposition I,3.6.7) the functor is exact if preserves finite fibre products and final objects. Indeed, the inverse image of an intersection is an intersection of inverse images and the inverse image of the whole space is the whole space. □

There are of course non-metrizable coarse spaces. Usually, we are only interested in metric spaces except in the following case. Note that coarse cohomology with twisted coefficients has been defined on all coarse spaces.

Proposition 3.

If we equip with the topological coarse structure associated to the one-point compactification of , we obtain a coarse space called ∗. This space ∗ is not metrizable but a final object for metric spaces. The constant sheaf on ∗ is flabby.

Proof.

A set is closed if it is finite or contains +. Thus, a subset is an entourage if for every subset the projection of to the first factor is finite exactly when the projection of to the second factor is finite.

Let X be a metric space and a basepoint. We define a map

We show that this map is coarsely uniform: If and a subset such that the projection to the first factor is finite then choose arbitrary with . Since the first factor of F is finite, there is some with . Then,

Thus, the projection of F to the second factor is finite. This implies that is coarsely uniform. If is bounded, then there exists some such that implies . Then, is contained in a ball of diameter S around . Thus, is coarsely proper. This way, we showed that is a coarse map. Suppose is another coarse map. Let be a subset such that the projection of to the first factor is finite. We have that is of the form

for some subset . Then, the projection of to the first factor is . Since is coarsely proper, the set is bounded. This implies that is bounded which is the projection of to the second factor. Since we only used that are coarse maps, we can use the same argument with the factors reversed. Thus, we showed that is an entourage in ∗. This implies that are close; they represent the same coarse map. This way we showed that ∗ is a final object for metric spaces.

If are infinite subspaces, then there exists a bijection . The set is an entourage and is not bounded. Thus, is not cocontrolled. We conclude that a coarse cover of a subset contains an element which is cofinite in U. Let A be an abelian group. Then,

This shows that is flabby. □

Lemma 20.

If A is an abelian group, then . The unit of at is given by

Proof.

If Z is a metric space and the unique coarse map we prove . This proves the claim since

The sheaf is the sheafification of the following presheaf

Now, this is just the constant sheaf on Z.

Now, we compute the unit of the adjunction . We denote by the presheaf inverse image functor. Then, the unit of the adjunction at is given by

The unit of the adjunction sheafification # and inclusion of presheaves in sheaves at is given by

This makes sense since assigns a value to where is a coarse disjoint union of . Since is a coarse map, the form a coarse disjoint union of U. Then, represents on U which in cocycle notation is . Now, we compose the units:

and obtain the desired result. □

Theorem 10.

The map induced by the inverse image functor

coincides with the canonical map

Proof.

We apply ([23], Scolium II.5.2). We checked that the proof of this result also works for sheaves on a Grothendieck topology. We choose , and a resolution on Y. Then, has a resolution on X. The morphism of complexes is given by

which makes the diagram

commute. □

commute. □

9. Sheaves on the Higson Corona

This chapter proves Theorem 5.

Lemma 21.

Let X be a metric space. If is a coarse cover of X then there exists a coarse cover of X with for every .

Proof.

By ([24], Lemma 15) there exists a cover of X as a set such that for every i. For every i there exists an in-between set with and . Then for every i, the sets are a coarse cover. Taking the intersection over those coarse covers provides a coarse cover

Now, let be an element. If there is some i with then

and in the other case for every i. Thus,

Now, we join appropriate elements of and obtain the desired coarse cover:

□

Given a sheaf F on we define a sheaf on : If both then . Thus, is a directed poset by inclusion. Now we define a sheaf on basic open subsets of . If is a subset, then

If is an inclusion of subspaces then implies . Thus, there is a well-defined restriction map which maps to . This makes a presheaf.

Proposition 4.

If X is a proper metric space and F a sheaf on then is a sheaf on .

Proof.

Let be a cover of a basic open set by basic open sets.

Let be a subset with . Then,

Thus, is an open cover of . Since is compact, there exists a finite subcover . By ([25], Lemma 32) the subsets are a coarse cover of X. By Lemma 21 there exists a finite coarse cover of X such that for every i and . Then are a coarse cover of A.

We show the base identity axiom: Let be elements with for every i. Since for every i the identity axiom on coarse covers implies .

Now we show the base gluablity axiom. Let be a section for every i such that for every . Then the glue to a section on A by the gluablity axiom on coarse covers. □

If is a morphism of sheaves on then we define for every basic open :

This definition makes sense since implies that . Thus, is an element in . By gluing along basic open covers, we obtain for every open a map . We show that is a morphism of sheaves: If is an inclusion of subsets and an element, then

Moreover, and . Thus, we have proved that is a functor. Namely, if denotes the category of sheaves on and denotes the category of sheaves on , then

is a functor between categories of sheaves.

Lemma 22.

Let X be a proper metric space. If are subsets with then there exists a subset with

an open cover and .

Proof.

Since is compact there only exists one proximity relation on which induces the topology on . Thus, the relation defined by if and the relation induced by ⋏ on the quotient coincide. Since both and are closed sets, we obtain

Thus, . Then, there exist with and . This in particular implies that . Then,

□

Given a subset of a proper metric the relations and imply . Thus, is a directed poset. If G is a sheaf on we define

If then implies . Thus, we can define a well-defined restriction map which maps to . This makes a presheaf on .

A sheaf F on is called reflective if for every subset the canonical map

is an isomorphism.

Proposition 5.

Let X be a proper metric space. If G is a sheaf on , then is a reflective sheaf on .

Proof.

Let be a coarse cover of .

We prove the identity axiom. Let be a section with for every i. Then there exists with in . Since we obtain

By Lemma 22 there is some with an open cover and . Thus, the identity axiom for open covers implies . This proves in .

Now, we prove the gluablity axiom. Let be a section for every i with for every . Suppose are represented by with . As in the first part of this proof, there is some subset with

and . By the gluablity axiom on open covers the glue to a section which represents a section .

Now, we show that is reflective. For every with there exists with and . Thus,

is an isomorphism. □

If is a morphism of sheaves on and a subset then

is well defined since implies

We show defines a morphism of sheaves on . If then

Moreover, and . Thus, we showed that is a functor between categories of sheaves:

In fact, its image is contained in the full subcategory of reflective sheaves.

Theorem 11.

If X is a proper metric space, the category of reflective sheaves on X is equivalent to the category of sheaves on via .

Proof.

Let G be a sheaf on . Then, for every there is a morphism

which naturally defines a morphism of sheaves . We show this map is bijective. Suppose is mapped by to 0. Then for every there exists with . Then,

Thus, is an open cover of . The global axiom on open covers of shows that on . Suppose is an element in . Then, as before, is an open cover of . Then is an element with

Thus, is surjective. It is easy to see that defines a natural transformation. This way, we showed that is a natural isomorphism between and .

Now, let F be a sheaf on . Then, for every , there is a map

This map is well defined since implies there is some such that for every the section vanishes. This in particular implies that . Now, we show is injective. If maps to 0 by then the support is closed in . Thus there exists an open on which vanishes. Thus represents the 0 element. Now we show is surjective if F is reflective. If , then there exists some and such that . Then, maps by to . □

Theorem 12.

If F is a reflective sheaf on then . The right side denotes sheaf cohomology on .

Proof.

We first show if G is a flabby sheaf on then is a flabby sheaf on . For every , the restriction is surjective. If then there exists some with .

Now we show is an exact functor. Let

be an exact sequence of sheaves on . If then there exists with . Since there is a cover and with . Then cover . Since is compact a finite subcover will do. Then form a coarse cover of A. By Lemma 21, there exists a coarse cover of A with . Then, maps to by . Thus, we have proved . If conversely, with a coarse cover of A and represents an element in , then in particular is an open cover containing . By Lemma 22, there exists with covered by . Since there exists with . Then, has the property that . Thus, . This way we proved , the sequence is exact at .

If F is a reflective sheaf on , then there exists a flabby resolution

of sheaves on . Since is an exact functor, we obtain an exact resolution of flabby sheaves

with an isomorphism . The global section functor on the reduced sequences gives the same result. □

Proposition 6.

If A is an abelian group and X a proper metric space, then on and on are isomorpic. In particular, is a reflective sheaf.

Proof.

If is a subset and denotes the inclusion then is an inclusion of a closed subset. We have . There is a bijective map defined as follows: A section in is represented by a Higson function where A is equipped with the word length metric. This function can be extended to the boundary since it is Higson. Then this function is a continuous map where A is equipped with the discrete topology. Since a coarse disjoint union of B is 1:1 with disjoint unions of by clopen sets we obtain a bijection. This tells us that . Applying the functor we obtain a bijection . □

Theorem 13.

If X is a proper metric space with then for every reflective sheaf and .

Proof.

The space is paracompact since it is compact. By ([26], Chapitre II.5.12) it is sufficient to show that the covering dimension of does not exceed n. By ([27], Theorem 1.1) we obtain . Thus the result follows. □

This result can be used to finalize our computations in Section 6.

Theorem 14.

If A is a finite abelian group, then

If denotes the free group with generators and A is finite again, then

Proof.

The cohomology in degree 0 is clear since has one end and has infinitely many ends. In degree 1, cohomology with finite coefficients vanishes by Lemmas 14 and 9, respectively. Now, both and trees have asymptotic dimension 1 [28]. Then, Theorem 13 implies that the higher cohomology groups vanish. □

10. Coarse Homotopy Invariance

This chapter proves Theorem 4.

Lemma 23.

If are coarse maps which are close to each other and is a cochain, then

- 1

- is a cochain;

- 2

- the composition of with the map φ is a cochain in ;

- 3

- the composition of with φ is a cochain in .

Proof.

We prove 1. first. Suppose is cocontrolled. We show is cocontrolled. If , then is cocontrolled since are coarse and close to each other. Thus, there exists some and with

Then,

is bounded. Thus, is cocontrolled. Now, is cocontrolled. Then,

is cocontrolled. If then . Thus, is blocky. This way we showed that is a cochain.

Now, we prove 2. Name the map by . If , then there exist such that . Now and . We use this to prove

Thus, has cocontrolled support. Moreover, if , then we have . Thus, is blocky. This way, we showed that defines a cochain.

The proof of 3. is similar to the proof of 2. and left to the reader. □

Lemma 24.

If I is a metric space, coarse maps which are close to each other and is a cocycle then

is a coboundary in .

Proof.

First, we define for a map

This map defines a cochain by Lemma 23.

If then is short for . We compute

We arrived at a sum where the terms marked with either contribute the desired terms or cancel each other out. The terms with add to a coboundary.

We first look at the terms . If the term for cancels with the term for . If the term for cancels with the term for . We did not yet count the terms for which give . The terms for contribute . Finally if then is counted only once and contributes .

It remains to show that the other terms contribute a coboundary:

□

Lemma 25.

If I is a metric space, a cochain and a family of coarse maps with the properties

- 1.

- for every ;

- 2.

- for every and some ;

then for every , there exists such that

independent of .

Proof.

If then is bounded, namely, contained in for some .

□

The proof of Theorem 15 can be illustrated by an example. Proposition 7 carries out the essential step of the proof for .

Proposition 7.

If the projection

induces an isomorphism in cohomology inverse to the induced map associated to the inclusion .

Proof.

In the following proof, is short for and abbreviates or .

We show that the map

induces the same map in cohomology as the identity on .

For we define an auxilary map

We obtain . The satisfy the conditions of Lemmas 24 and 25.

Suppose . Let be a cocyle. Then, since are close. Thus, there is some with . Namely,

Then, define the map

This map is well defined, since for each fixed point in , only finitely many terms in the above sum are defined. If , then Lemma 25 implies that there exists some such that each summand of has support contained in . This implies that . Thus, has cocontrolled support. Now, may or may not be blocky. We have to go the extra step to produce a map with cocontrolled support which is also blocky. To obtain such a map, we are going to add a coboundary.

By Lemma 24 we obtain

in the next step, we obtain

Successively, we obtain

By the proof of Lemma 24 the map satisfies the conditions of Lemma 25. Thus, the sum has cocontrolled support. This implies that the map

has cocontrolled support. We have

Thus, is blocky, namely, if then . This way we have proved that is a cochain.

Lastly, we have

Thus, defines a coboundary. This way, we showed induces the identity on for . It remains to show the statement for .

Since is one-ended a cocycle, is represented by a constant function on except on a bounded set. Then, is constant except on a bounded set. Thus, is the same map as the identity on . □

Now, denote and equip this space with the Manhattan metric. Namely, if then,

If X is a metric space and a point, then the asymptotic product of X and I is defined to be

The paper [18] shows that is the pullback of and . Moreover, we can define a well-defined homotopy theory: If X is a metric space, define maps

Definition 4.

If are two coarse maps, they are coarsely homotopic if there exists a coarse map with and .

The paper [18] shows that coarse homotopy is an equivalence relation and compares this theory with other homotopy theories on the coarse category.

Lemma 26.

If X is a metric space, then .

Proof.

Denote by the projection of to the first factor. Since is a surjective coarse map, the inequality follows easily.

Now, suppose is a coarse disjoint union. This means that are disjoint and form a coarse cover of X. Namely, the set is bounded for every . Then, the set is bounded. Without loss of generality, we assume it is empty. Thus, for fixed either for every or for every .

Now, we show form a coarse disjoint union. They are disjoint by the assumption. Let be a number and let be two points with . Then, with . Then, the set is bounded, which implies that is bounded. □

Theorem 15.

If two maps are coarsely homotopic, then they induce the same map in cohomology.

Proof.

We just need to show that the projection which sends an element to x induces an isomorphism in cohomology. Indeed, since the maps are both the unique inverse to . Then, and induce the same map in cohomology.

Now, Proposition 7 already showed is an isomorphism with in place of X and in place of I. The same proof can be transferred to this situation where we use Lemma 26 for the step in degree 0.

Namely, we proceed as follows. In the following proof, is short for and abbreviates or .

We show that the map

induces the same map in cohomology as the identity on .

For , we define an auxilary map

We obtain . The satisfy the conditions of Lemmas 24 and 25.

Suppose . Let be a cocyle. Then, since are close. Thus, there is some with . Namely,

Then, define the map

This map is well defined since for each fixed point in , only finitely many terms in the above sum are defined. If , then Lemma 25 implies that there exists some such that each summand of has support contained in . This implies that . Thus, has cocontrolled support. Now, may or may not be blocky. We have to go the extra step to produce a map with cocontrolled support which is also blocky. To obtain such a map, we are going to add a coboundary.

By Lemma 24, we obtain

In the next step, we obtain

Successively, we obtain

By the proof of Lemma 24, the map satisfies the conditions of Lemma 25. Thus, the sum has cocontrolled support. This implies that the map

has cocontrolled support. We have

Thus, is blocky; namely, if then . This way, we have proved that is a cochain.

Lastly, we have

Thus, defines a coboundary. This way, we showed induces the identity on for . It remains to show the statement for .

The proof of Lemma 26 shows that induces the identity on . Namely, if then there are only boundedly many such that has mixed values on . Thus is the same map as up to bounded error. □

A metric space X is called coarsely contractible if the map is a coarse homotopy equivalence.

Lemma 27.

If X is a coarsely contractible metric space, then for every and finite abelian group A.

Proof.

By definition, the map is a coarse homotopy equivalence. Therefore, it induces an isomorphism in cohomology by Theorem 15. Since is acyclic, so is X by Theorem 14. □

11. Cohomology of Free Abelian Groups

This chapter proves Theorem 6.

If X is a uniquely geodesic metric space and then a geodesic triangle with vertices is the union of the geodesics joining a to b, b to c and c to a. There is a comparison map which is an isometry on each of the edges. Then, X is called CAT(0) if for every for every .

Lemma 28.

If X is a CAT(0) space then is coarsely contractible.

Proof.

We define two maps

and show that they are coarse homotopy inverses.

Since X is CAT(0), there exists for every a geodesic joining to x. The inequality holds for every by the curvature condition.

We define

Here and . The map h joins to . It remains to show that h is coarse. If and , then

for large compared to R. Then,

for large compared to R. Thus, h is coarsely uniform.

Lemma 28 in particular implies that is a coarsely contractible subspace of . In fact, and are coarsely contractible subspaces of and so is every finite intersection of them.

Lemma 29.

If is a sheaf on a metric space X and a Leray cover of X, namely, a coarse cover such that every finite intersection is -acyclic, then

The right side denotes Čech-cohomology of the cover .

Proof.

For sheaves on a topological space, there exist a number of proofs for this result. We mimic the proof of ([20], Theorem III.4.5).

Embed in a flabby sheaf and take the quotient . Then, there is a short exact sequence of sheaves

Since there is a short exact sequence of abelian groups

Taking products, we obtain an exact sequence of Čech-cocomplexes

This results in a long exact sequence of Čech cohomology. Since is flabby, its Čech cohomology vanishes for . This way, we get an exact sequence

and isomorphisms

for each . Associated to the exact sequence of sheaves (7) there is an exact sequence

Since for any sheaf we can compare the exact sequences (8) and (10) and obtain

Now, the long exact sequence in cohomology for (7) and being -acyclic implies that is -acyclic. Thus, satisfies the conditions of this Lemma. This way, we use induction and isomorphisms (9) to obtain the result for . □

Theorem 16.

We can compute cohomology:

if A is a finite abelian group.

Proof.

If , this result is already Theorem 14.

Suppose . We compute cohomology of . The result for follows since the spaces and are coarsely equivalent. For define and . A finite intersection of those halfspaces is coarsely contractible by Lemma 28. We show the form a coarse cover. Let be a point. We show . If then implies . Additionally, implies . Together they imply and in all together the result. Thus, forms a Leray cover.

By Lemma 29, the metric cohomology of is the Čech cohomology of . In the topological world the sphere admits a Leray cover by and . The combinatorical information of this cover is the same as that of . Thus, both covers have the same nerve. Since the nerve contains all the cohomological information, we just proved that (as a metric space) has the same cohomology as (as a topological space). This proves the claim. □

There is another method we can use to compute the cohomology of . If X is a CAT(0) metric space, then the coarse cone over X is given by . Lemma 28 tells us that the coarse cone is coarsely contractible. Now, the coarse suspension of a CAT(0) metric space X is given by .

Lemma 30.

If X is a CAT(0) metric space, then the coarse suspension shifts coarse sheaf cohomology by one degree, namely, for .

Proof.

We cover by two sets and . They form a coarse cover: if with then , and . Since s is positive and t is negative, we obtain . Furthermore, and . Thus, coarsely cover X.

There are coarse homotopy equivalences and . Namely, the inclusion has a coarse homotopy inverse

The coarse homotopy connecting with is given by

Here . We show h is coarse: If then in particular and

Thus, is coarsely uniform. If then and if then or if then . Thus, is coarsely proper.

The coarse homotopy equivalence connecting X with is given by and its inverse is

The coarse homotopy joining to is given by

We prove that is coarsely proper; the property coarsely uniform can be shown similarly as for . If then and .

Then, the long exact sequence of Theorem 8 gives us

in degree . □

Remark 3.

The suspension functor has a right adjoint, the loop space. If X is a metric space, then the loop space of X, consists of coarse maps . A subset is an entourage if for every the set is an entourage in Y. Note that defined this way does not have a connected coarse structure. Then, there exists a natural isomorphism

Suppose coarse maps denote the th coarse homotopy group of Y. If we insert for X in the adjoint relation, then we can see that the loop space shifts coarse homotopy groups down a dimension.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bunke, U.; Engel, A. Coarse cohomology theories. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.08599. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, J.; Siegel, P. Sheaf theory and Paschke duality. J. K-Theory 2013, 12, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A. Coarse geometry via Grothendieck topologies. Math. Nachr. 1999, 203, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, J.C. On the Vietoris-Rips complexes and a cohomology theory for metric spaces. Ann. Math. Stud. 1995, 38, 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Higson, N.; Roe, J. A homotopy invariance theorem in coarse cohomology and K-theory. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 1994, 345, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchener, P.D. Coarse homology theories. Algebr. Geom. Topol. 2001, 1, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, C. Equivariant coarse (co-)homology theories. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.02053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesling, J. The one-dimensional Čech cohomology of the Higson compactification and its corona. Topol. Proc. 1994, 19, 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Higson, N.; Roe, J.; Yu, G. A coarse Mayer-Vietoris principle. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1993, 114, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J. Coarse cohomology and index theory on complete Riemannian manifolds. Mem. Amer. Math. Soc. 1993, 104, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J. Lectures on Coarse Geometry; University Lecture Series; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2003; Volume 31, p. viii+175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, S. Homological Methods in Coarse Geometry. Ph.D. Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA, 2010; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, J. Index Theory, Coarse Geometry, and Topology of Manifolds; CBMS Regional Conference Series in Mathematics; Published for the Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences, Washington, DC; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1996; Volume 90, p. x+100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higson, N.; Roe, J. Analytic K-Homology; Oxford Mathematical Monographs; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; p. xviii+405. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.L. Coarse Baum-Connes conjecture. K-Theory 1995, 9, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G. The coarse Baum-Connes conjecture for spaces which admit a uniform embedding into Hilbert space. Invent. Math. 2000, 139, 201–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E. Coarse cohomology with twisted coefficients. Math. Slovaca 2020, 70, 1413–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E. A pullback diagram in the coarse category. Appl. Categ. Struct. 2023, 31, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E. Coarse homotopy on metric spaces and their corona. Comment. Math. Univ. Carolin. 2021, 62, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorne, R. Algebraic Geometry; Graduate Texts in Mathematics, No. 52; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1977; p. xvi+496. [Google Scholar]

- Mendivil, F. Compactifications and Function Spaces. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tamme, G. Introduction to étale Cohomology; Universitext; Translated from the German by Manfred Kolster; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; p. x+186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, B. Cohomology of Sheaves; Lecture Notes Series; Aarhus Universitet, Matematisk Institut: Aarhus, Denmark, 1984; Volume 55, p. vi+237. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, E. A totally bounded uniformity on coarse metric spaces. Topol. Appl. 2019, 263, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E. Twisted Coefficients on coarse Spaces and their Corona. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.00380. [Google Scholar]

- Godement, R. Topologie Algébrique et Théorie des Faisceaux; Actualit’es Sci. Ind. No. 1252; Publ. Math. Univ. Strasbourg: Hermann, Paris, 1958; Volume 13, p. viii+283. [Google Scholar]

- Dranishnikov, A.N.; Keesling, J.; Uspenskij, V.V. On the Higson corona of uniformly contractible spaces. Topology 1998, 37, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P.W.; Yu, G. Large Scale Geometry; EMS Textbooks in Mathematics; European Mathematical Society (EMS): Zürich, Switzerland, 2012; p. xiv+189. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).