Abstract

We study the relationship between the category of R-modules () and the category of intuitionistic fuzzy modules (). We construct a category of complete lattices corresponding to every object in and then show that, corresponding to each morphism in , there exists a contravariant functor from to the category (=union of all , corresponding to each object in ) that preserve infima. Then, we show that the category forms a top category over the category . Finally, we define and discuss the concept of kernel and cokernel in and show that is not an Abelian Category.

1. Introduction

The category theory is concerned with the mathematical entities and the relationships between them. Categories also emerge as unifying concepts in many fields of mathematics, particularly in all other areas of computer technology and mathematical physics. In the L.A. Zadeh [1] introductory paper, fundamental research is being carried out in the fuzzy sets context. Almost all of this mathematical development has been categorical. Several other researchers have developed and researched theories of fuzzy modules, fuzzy exact sequences of fuzzy complexes, and fuzzy homologies of fuzzy chain complexes [2,3,4,5,6].

K.T. Atanassov [7,8] suggested the interpretation of intuitionistic fuzzy sets that could be a generalized form of fuzzy sets. R. Biswas was the first to apply the criterion of intuitionistic fuzzy sets in algebra and led to the introduction of an intuitionistic fuzzy subgroup of a group in [9]. Later on, Hur and others in [10] and [11], brought the perception of the intuitionistic fuzzy subring and ideals. B. Davaaz and others in [12] delivered the perception of an intuitionistic fuzzy submodule of a module. Later, many mathematicians contributed to the study of intuitionistic fuzzy submodules, see [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The focus of this study is to carry the analysis of intuitionistic fuzzy modules over a commutative ring, to a categorical approach, to pave the way for future research.

Along with the commutative ring R with unity, we defined a category () of intuitionistic fuzzy modules where the classes of all intuitionistic fuzzy modules and intuitionistic fuzzy R-homomorphisms constitute objects and morphisms. The compositions of morphisms are the ordinary compositions of functions. Moreover, we reveal that is an abelian group under the ordinary addition of R-homomorphisms, where A and B are intuitionistic fuzzy submodules. In the context of the additive composition, this structure appears to have a distributive influence on the left and at the right. This paper shows that seems to be an additive category, even though it is not an abelian category (Section 4).

In this approach, we are implementing an important technological tool to “optimally intuitionistic fuzzify” the R-homomorphism families. This capability to intuitionistic fuzzify provides with the top category structure over (Section 3). We even characterize zero objects, kernels, cokernels in . Our objective is to study the intuitionistic fuzzy aspects of some algebraic structures, such as rings and modules. The study of fuzzy aspects of rings and modules is well developed, even then there are many scopes for further studies in intuitionistic fuzzification of such algebraic structures. The adopted approach is better than the previously developed fuzzy approach as it includes a non-membership function, which provides a more effective and efficient tool for dealing with uncertainties.

Finally, we have shown that the category of fuzzy modules is a subcategory of a category of intuitionistic fuzzy modules , and we established a contravariant functor from the category to the category (= union of all , corresponding to each object in ). For basic definitions and results about category, we follow [20,21,22].

2. Materials and Methods

- Construct the category of intuitionistic fuzzy modules (.

- Study the relationship between the category of R-modules () and the category of intuitionistic fuzzy modules ().

- Analyze the concept of kernel and cokernel in .

- Investigate that is not an abelian category.

3. Results

Throughout the paper, R is a commutative ring with unity 1 and . M is a unitary R-module, is a zero element of M, and I represents the unit interval .

3.1. Preliminaries

Definition 1

([20]). A category C is a quadruple consisting of:

- (C1) , an object class;

- (C2) a set of morphisms is associated with each ordered object pair ;

- (C3) a morphism , for each object X;

- (C4) a composition law holds i.e., if and , ; such that it satisfies the following axioms:

- (M1) , and ;

- (M2) , ;

- (M3) a set of morphisms are pairwise disjoint.

Example 1.

- (1)

- , the category with sets as objects, functions as morphisms, and the usual compositions of functions, as compositions.

- (2)

- , the category with groups as objects, group homomorphisms as morphisms, and their compositions as compositions.

- (3)

- , the category with abelian groups as objects, group homomorphisms as morphisms, and their compositions as compositions.

Definition 2

([21]). The opposite category of the specified category C is constructed when reversing the arrows, i.e., for each ordered object pair

Definition 3

([21]). Category D is said to be a subcategory of the category C when , ordered object pair and composition of morphisms, and the identity of D should be the same as that of C.

Example 2.

The category is a subcategory of .

Definition 4

([21]). For the ordered object pair of D, a full subcategory of a category C is a category D if and .

Example 3.

The category is a full subcategory of .

Definition 5

([21]). A category C is called abelian if

- 1.

- C does have a zero object.

- 2.

- There is a product and a co-product for any pair of objects of C.

- 3.

- Each morphism in C does have a kernel and a cokernel.

- 4.

- Each monomorphism in C seems to be the kernel of its cokernel.

- 5.

- Any epimorphism in C seems to be the cokernel of its kernel.

Example 4.

The category is an example of an abelian category.

Proposition 1

([4]). The collection of all R-modules and R-homomorphisms is a category. This category is denoted by .

Definition 6

([21]). Let and be two categories and let and be maps. Then the quadruple is a functor provided:

- (i)

- implies ;

- (ii)

- implies ,;

- (iii)

- preserves composition, i.e., , and ;

- (iv)

- F preserves identities, i.e., , .

Remark 1

([21]).

- (i)

- Instead of we write .

- (ii)

- In preference to we write .

- (iii)

- We call a functor from C to D.

- (iv)

- A functor defined above is called a covariant functor that preserves:

- The domains, the co-domains, and identities.

- The composition of arrows, it especially retains the path of the arrows.

- (v)

- A contravariant functor F is similar to the covariant functor in addition to the other side of the arrow, and .

Thus, a contravariant functor is the same as a covariant functor .

Definition 7

([22]). The category formed from a given category C is called a top category over C, if corresponding to every object A in C, the collection of elements of C with the ordered relation defined on it, form a complete lattice, and the inverse image map , form a contravariant functor.

Definition 8

([7,8,9]). An intuitionistic fuzzy set (IFS) A in X can be represented as an object of the form , where the functions and denote the degree of membership (namely ) and the degree of non-membership (namely ) of each element to A respectively and for each .

Definition 9

([12,13,15]). An IFS of R-module M is called an intuitionistic fuzzy submodule (IFSM) if

- (i)

- , ;

- (ii)

- and , ;

- (iii)

- and , .

Example 5.

Let . Then M is an -module under usual componentwise addition and scalar multiplication composition. Then the intuitionistic fuzzy set of M defined by

is an intuitionistic fuzzy submodule of M.

Definition 10

([13,19]). Let K as a submodule of an R-module M. The intuitionistic fuzzy characteristic function of K is defined by , described by , where

Clearly, is an IFSM of M. The IFSMs are called trivial IFSMs of module M. Any IFSM of the module M apart from this is called proper IFSM.

Definition 11

([17]). Let are IFSM of R-modules M and N respectively. Then the map is called an intuitionistic fuzzy R-homomorphism ( or IF R-hom ) from A to B if

- (i)

- is R-homomorphism and

- (ii)

- and .

To avoid confusion between an R-homomorphism and an intuitionistic fuzzy R-homomorphism . We denote the latter by . So, given an IF R-homomorphism , is the underlying R-homomorphism of . The set of all IF R-homs from A to B is denoted by .

Example 6.

Let and be two Z-modules. Define intuitionistic fuzzy sets and on M and N, respectively, as

Then A and B are intuitionistic fuzzy submodules of M and N, respectively.

Define the mapping by . Clearly, f is a R-homomorphism. Consider , , , . Also,, , , . Thus, and .

Hence, is an IF R-homomorphism.

Proposition 2.

form an additive abelian group. Moreover, it is a unitary R-module when R is a commutative ring with unity.

Proof.

Since and implies that there exists zero IF homomorphism . Let and , we have .

Similarly, we can show that . This shows that . Now, we can define . The addition obviously satisfies the commutative law and associative law. Also, define − for every .

We have confidence in the definition, because: and . This shows that .

Precisely, and . This shows that works as the additive inverse of and is the zero element (or additive identity) in . Hence, is an additive abelian group.

Furthermore, we define the R-scalar multiplication on as follows:

For any and define .

As the map is the ordinary R-homomorphism of M into N and

and . It follows that . As R is a commutative ring. It is clear that implies that . Moreover, for , we have implies that . Also, . Further, implies that .

Hence, is a unitary R-module. □

If and , define

and

As is the pre-image of under f, we have . Especially, if , then we have , for all .

Proposition 3.

Let A and B are IFSM of R-modules M and N, respectively, and is IF R-hom, then:

- (i)

- is a submodule of M;

- (ii)

- The restriction of A to i.e., is an IFSM of A.

Proof.

- (i)

- Since is IF R-hom.Let be zero element of M, then . Let and , then and implies that . In particular . Further, if , Conveniently, we can predict . Thus, is a submodule of M.

- (ii)

- Let . Then , where and . Now it is simple to prove that C is an IFSM of M and .

□

3.2. Categories of Intuitionistic Fuzzy Modules

In this section, we analyze the IF-modules category and the existence of the covariant functor between the modules category and IF-modules category.

Theorem 1.

Let and are two IF modules of R-modules M and N respectively. Then the function on R-module defined by

where and is an intuitionistic fuzzy submodule of .

Proof.

As shown in Proposition 2, is an R-module, where the scalar multiplication on is defined as .

Next, we show that the function on R-module defined by

where and is IFSM of .

Let and , Consider

Thus . Likewise, we are able to exhibit that .

Further, let and . Consider

Thus, . Likewise, we are able to exhibit that .

Also, .

Likewise, we can demonstrate that . Hence is IFSM of R-module . □

Definition 12.

The category has R-modules as objects and R-homomorphisms as morphisms, with composition of morphisms defined as the composition of mappings.

An IF-module category over the base category is completely described by two mappings:

IF-module category consists of

- (C1) Ob() the set of objects as IFSMs on Ob(), i.e., the objects of the form ;

- (C2) the set of IF R-homomorphisms corresponding to underlying R-homomorphisms from , i.e., IF R-homomorphisms of the form , such that for ,as defined in Theorem 1, a composition law associating to each pair of morphisms and , a morphism , such that the following axioms hold:

- (M1) Associativity: , for all , and ;

- (M2) preservation of morphisms: ;

- (M3) existence of identity: there is an identity such that .

Thus, A category of IF R-modules can be constructed as

Proposition 4.

is a subcategory of .

Proof.

It follows from Definition 3, Proposition 1 and Theorem 1. □

Proposition 5.

There exist a covariant functor from to .

Proof.

Define by , where .

Let . Thus , where described by

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

- (v)

- (vi)

- (vii)

- (viii)

- .

We want to prove that preserves object, composition, domain, and codomain identity.

Let , such that

- ⇒

- and

- ⇒

- and

- ⇒

- is well defined.

Let then .

Then, , and . For any , we have

Therefore, .

Moreover, implies that is the identity element in . Hence, is a covariant functor. □

3.3. Optimal Intuitionistic Fuzzification

In this section, we show that the category forms a top category over the category . To prove this, we first construct a category of complete lattices corresponding to every object in and then show that corresponding to each morphism in , there exists a contravariant functor from to the category (=union of all , corresponding to each object in ) that preserve infima. Finally, we define the notion of kernel and cokernel for the category and show that is not an abelian category.

Let and are IFSM of R-modules M and N, respectively, and is R-homomorphism. With the help of A and f, we can provide an IF module structure on N by

It is clear that is an IFSM of and is an IF R-hom.

With the help of B and f, we can provide an IF module structure on M by

Hence, is an IFSM of M and is an IF R-hom.

Lemma 1.

Let M and N are R-modules and be R-homomorphism.

- (i)

- If is an IFSM of M, then there is an IFSM of N such that for any IFSM of N, is an IF R-hom if and only if .

- (ii)

- If is an IFSM of N, then there is an IFSM of M such that for any IFSM A of M, is an IF R-hom if and only if .

Proof.

(i) Now, is an IF R-hom if and only if and . Let be any element, then .

Likewise, we are able to exhibit that i.e., .

(ii) Now, is an IF R-hom if and only if and . Now, and implies that . □

Observe that If , now for each IFSM A [B] on M [N] one will have [] IFSMs, we conclude that f is trivially intuitionistic fuzzified relative to A [B]. In particular, we will say that for each IFSM A [B] of M [N], we have obtained IF R-hom [].

Lemma 2.

The set form a complete lattice associated with the order relation if and , .

Proof.

Let be a collection of elements of . Then infimum and supremum on are explicitly specified as:

and

Then form a complete lattice. □

Remark 2.

- (i)

- The least element of is and the greatest element of is .

- (ii)

- under the order relation defined above form a category where= all IF-modules of M and = order relation defined above.

- (iii)

- Supremum can also be defined as , which only holds for IF sets but does not hold for IF modules including when J is finite.

For e.g., let -module Z and IFSMs and of M described as:

Take , where and . Here we can check that is not an IFSM of M, for and .

Lemma 3.

The set form a complete lattice associated with the order relation if and .

Proof.

Let be a collection of elements of . Then infimum and supremum on are explicitly specified as:

and

Then form a complete lattice. □

Remark 3.

under the order relation defined above form a category where = all IF-modules of M and = order relation as defined above.

Theorem 2.

is a top category over .

Proof.

This becomes sufficient to prove that, with every , the corresponding complete lattice specified in Lemma 2. For each , defined as determine a contravariant functor . Thus, we are trying to prove that

- (i)

- for all , preserve infima,

- (ii)

- for each , and

- (iii)

- for each identity R-homomorphism , we have the identity function .

Consider is a non-empty subfamily of , and let . Then,

Thus, preserves infima.

Let is homomorphism, and let and , then

Thus, .

Further, is the identity R-homomorphism, such that . Then be the identity element in , for if be any element, then . Hence proved. □

Remark 4.

There exists a covariant functor so preserves suprema and is determined by so that .

Proof.

It is very simple to find that preserves suprema and is the identity element in . Furthermore, we have

Thus . Hence, the result is proved. □

Lemma 4.

(i) Let , N are R-modules and be a collection of R-homomorphisms. If is a collection of IFSMs of , then there exists a smallest IFSM of N so that is an IF R-hom, , where , here and .

(ii) Let M and are R-modules and be a collection of R-homomorphisms. If are IFSMs of , then there exists a largest IFSM of M so that is an IF R-hom, , where , here and .

Proof.

(i) Using Lemma 1(i), for each , is IFSM of , there exists IFSM on N so that for every IFSM of N, is an IF R-hom if and only if , i.e., and .

Let and . Subsequently, the consequence follows.

(ii) Using Lemma 1(ii), for each , is IFSM of N, then there exists an IFSM of M, such that for any IFSM of M, is an IF R-hom if and only if , i.e., and .

Let and . Subsequently, the consequence follows. □

Lemma 5.

(i) Let are IFSMs of and be a family of R-homomorphisms and R-homomorphism then

(ii) Let are IFSMs of and be a family of R-homomorphisms and a homomorphism then

Proof.

- (i)

- Let be the collection of R-homomorphisms. Then, by Lemma 4(i), there exists IFSM of T such that is IF R-hom, , where , here and . Consider

- (ii)

- Let be the collection of R-homomorphisms. Then by Lemma 4 (ii), there exists IFSM of L such that is IF R-hom, , where , here and . Now, we have

Thus, . □

Remark 5.

From Lemma 4 and Lemma 5, we are able to optimally intuitionistically fuzzify [], in respect to the family of IFSMs [].

Theorem 3.

The category of IF modules has kernels and cokernels.

Proof.

Let and be IFSM of R-modules M and N, respectively. Let be an IF R-hom corresponding to the R-homomorphism .

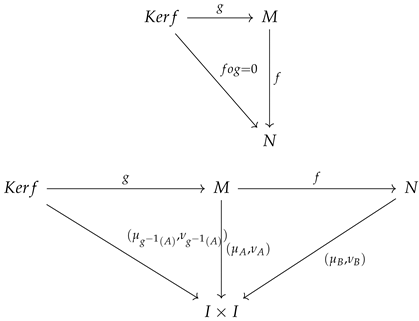

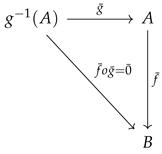

For Ker f, there exists an inclusion map in order for the subsequent diagram commutes

|

For Ker , there exists an inclusion map such that the following diagram commutes

|

Therefore, the kernel of is defined as with the inclusion map .

Thus, the kernel of is given as , where the inclusion map is .

Similarly, the cokernel of is defined as , where the projection map and . □

Remark 6.

Although the category of IF modules has kernels and cokernels even then it is not an abelian category.

By definition of the abelian category, every monomorphism should be normal, i.e, every monomorphism is a kernel of some morphism. An IF R-hom of IFSM C of M on being normal (i.e., being a kernel) C should be identical to . Consequently, for , the IF R-hom is a sub-object of , which is not a kernel. Thus, is not an abelian category.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we studied the category of intuitionistic fuzzy modules over the category of fuzzy modules by constructing a contravariant functor from the category to the category (=union of all , corresponding to each object in ). We showed that is a subcategory of . Further, we showed that is a top category that is not an abelian category.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.; Methodology, C.; Supervision, P.K.S.; Validation, P.K.S.; Writing—Original Draft, Chandni; Writing—Review and Editing, P.K.S. and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewer(s) for the constructive and insightful comments, which have helped us to substantially improve our manuscript. The second author takes this opportunity to express gratitude to Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, for giving her the platform for the research work to be conducted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inform. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, R.; Zahedi, M.M. Fuzzy chain complex and fuzzy homotopy. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2000, 112, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permouth, L.; Malik, D.S. On categories of fuzzy modules. Inf. Sci. 1990, 52, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, P.K. A study of functors associated with fuzzy modules. Discovery 2014, 24, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi, M.M. Some results on fuzzy modules. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1993, 55, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, M.M.; Ameri, R. Fuzzy exact sequence in category of fuzzy modules. J. Fuzzy Math. 1994, 2, 409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Atanassov, K.T. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986, 20, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassov, K.T. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets Theory and Applications, Studies on Fuzziness and Soft Computing, 35; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, R. Intuitionistic fuzzy subgroup. In Mathematical Forum X; Dibrugarh University: Assam, India, 1989; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, K.; Kang, H.W.; Song, H.K. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Subgroups and Subrings. Honam Math. J. 2003, 25, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hur, K.; Jang, S.Y.; Kang, H.W. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Ideals of a Ring. J. Korea Soc. Math. Educ. Ser. B 2005, 12, 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Davvaz, B.; Dudek, W.A.; Jun, Y.B. Intuitionistic fuzzy Hv-submodules. Inf. Sci. 2006, 176, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, D.K. Topics in Intuitionistic Fuzzy Algebra; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrucken, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-8443-9147-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cigdem, C.A.; Davvaz, B. Inverse and direct system in the category of intuitionistic fuzzy submodules. Notes Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets 2014, 20, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, P.; John, P.P. On Intuitionistic Fuzzy Submodules of a Module. Int. J. Math. Sci. Appl. 2011, 1, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.K.; Kaur, T. Intuitionistic fuzzy G-modules. Notes Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets 2015, 21, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.K. On intuitionistic fuzzy representation of intuitionistic fuzzy G-modules. Ann. Fuzzy Math. Inform. 2016, 11, 557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.K. Exact sequence of intuitionistic fuzzy G-modules. Notes Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets 2017, 23, 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.K.; Kaur, G. On intuitionistic fuzzy prime submodules. Notes Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets 2018, 24, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Lim, P.K.; Lee, J.G.; Hur, K. The category of intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Ann. Fuzzy Math. Inform. 2017, 14, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinster, T. Basic Category Theory. In Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Volume 143, ISBN 978-1-107-04424-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wyler, O. On the categories of general topology and topological algebra. Arch. Math. 1971, 22, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).