Abstract

Augmented Reality (AR) is transforming education by integrating digital and real-world elements to create immersive and practical learning experiences. AR offers unique benefits in education, such as enhancing student engagement, facilitating understanding of complex concepts through visualizations, and promoting collaborative learning. However, it also faces significant barriers, including high costs, technological limitations, and a lack of standardized evaluation frameworks. Drawing on examples across STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), humanities, and arts education, this article highlights how AR can effectively enhance learning outcomes. This narrative review synthesizes recent research on AR in education, drawing on empirical and conceptual studies across different educational levels and domains. Additionally, this paper examines the relationship between AR and major learning theories, presenting relevant case studies and the application of AR across various educational domains and target audiences. The review offers practical recommendations for educators, instructional designers, and researchers aiming to integrate AR into formal and informal learning environments, and introduces the ARCADE framework (Align–Rationale–Configure–Activate–Document–Evolve) as an actionable cycle to guide the design, implementation, and reporting of AR-based educational interventions.

1. Introduction

In the digital age, the education landscape is undergoing an unprecedented transformation. The rapid evolution of technologies is redefining not only how we live and work, but also how we learn (McDiarmid & Zhao, 2022). In an increasingly interconnected world, the development of innovative and engaging ways to advance students’ knowledge is no longer an option, but a necessity. Among these emerging technologies, Augmented Reality (AR) stands out for its potential to make learning more interactive, personalized, and close to real-world experiences (Al-Ansi et al., 2023; Garzón et al., 2021). The search for new educational strategies is not limited to improving academic performance but also aims to stimulate students’ curiosity, enthusiasm, and participation. In this context, AR offers a promising answer, integrating virtual and real-world content to create immersive educational experiences that overcome the limitations of traditional teaching.

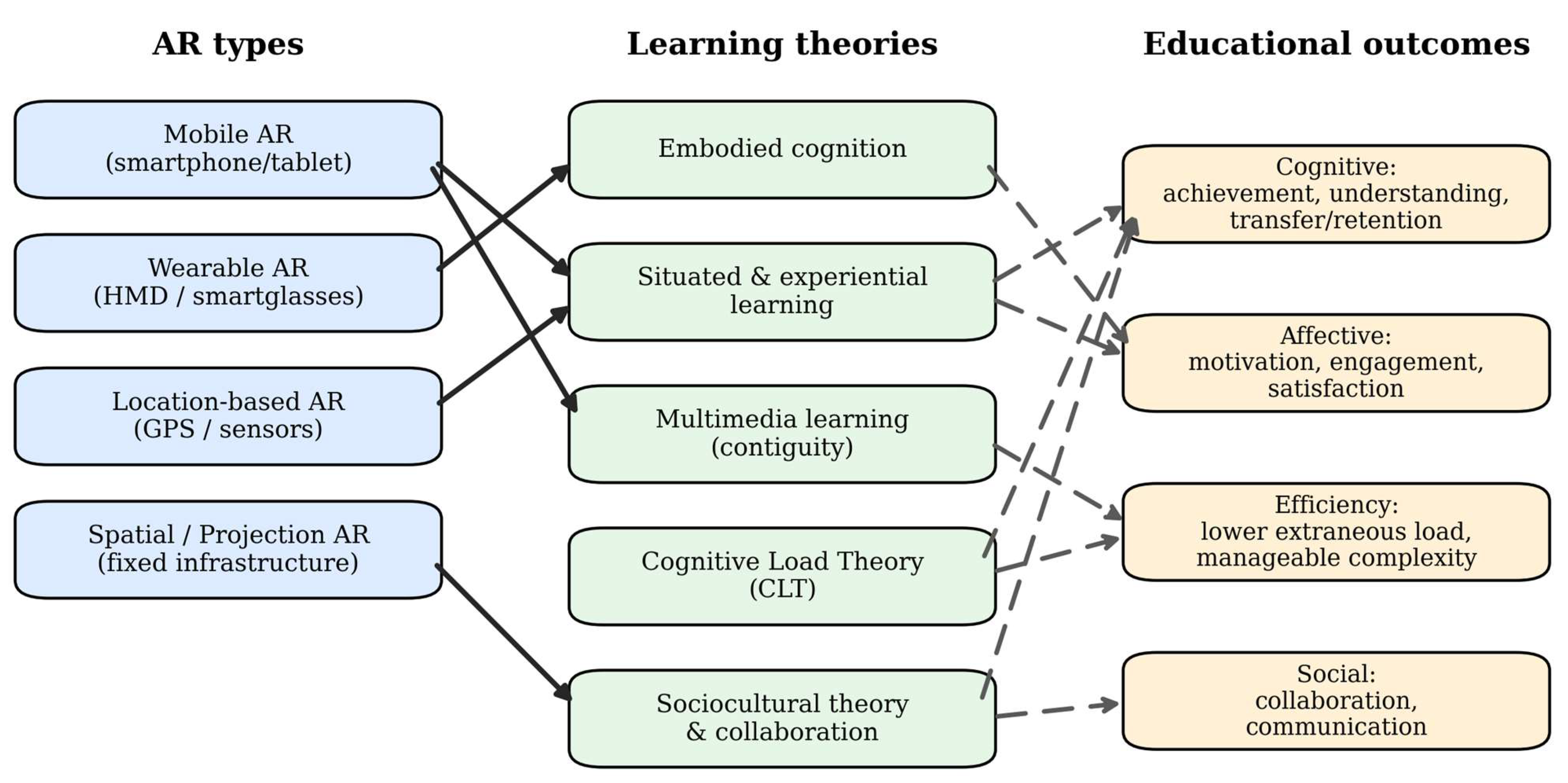

Within the context described above, this paper provides an education-centered narrative review of AR. The primary objective is to support educators, instructional designers, and researchers by clarifying the educationally relevant aspects of AR and by explaining how recurrent AR affordances relate to major learning theories and how these theory-linked mechanisms connect to educational outcomes across domains (e.g., STEM, humanities, and arts).

While AR entails important technical and historical developments, the primary lens of this review remains educational. Accordingly, the overview of AR definitions, typologies, and technological evolution is included only to the extent that it clarifies the instructional affordances that underpin learning design decisions (e.g., in situ overlays, spatial anchoring, interaction, collaboration) and the constraints that may shape implementation. The core contribution is therefore a theory-informed synthesis that maps AR features and learning mechanisms to learning theories and commonly assessed outcomes, and derives design and methodological recommendations to support sustainable, human-centered AR implementations in educational practice. To operationalize these proposed directions, we introduce the ARCADE framework (Align–Rationale–Configure–Activate–Document–Evolve), an actionable cycle intended to support coherent design, implementation, and reporting choices in educational AR.

Compared with prior reviews, this narrative review shifts the emphasis from descriptive trend mapping toward a theory-informed synthesis with practice-oriented guidance, providing a broader synthesis that (a) connects AR to major learning theories, (b) maps applications across STEM, humanities, and arts, and (c) discusses design and methodological recommendations for sustainable, human-centered AR solutions in education. For example, Garzón et al. (2021) provided a broad historical and technological overview of educational AR, whereas the present review explicitly links recurrent AR features to major learning theories and derives design and methodological recommendations for sustainable, human-centered implementations. Similarly, Akçayır and Akçayır’s (2017) systematic review examined publication trends, learner populations, AR technologies, and reported advantages and challenges. In contrast, this paper offers a theory-informed narrative review that broadens the educational domains considered and provides a synthesis grounded in learning theories, along with actionable recommendations for adopting AR in educational settings.

2. Methodological Approach

This paper is based on a narrative review of the literature on AR in education. Rather than aiming at an exhaustive, protocol-driven synthesis, a narrative review allows for a flexible integration of empirical and conceptual studies and for a critical discussion of how AR has been framed and implemented across different educational levels and domains.

Searches were last updated in October 2025. No strict publication-year window was imposed. However, screening and selection primarily focused on recent works that reflect the diffusion of mobile and wearable AR in educational contexts. Literature searches were conducted iteratively in Scopus and Web of Science and complemented by backward and forward citation tracking of key papers. Search queries combined AR-related terms with education-related terms and domain-specific keywords. Illustrative search strings included: augmented reality AND education AND learning; augmented reality AND teaching; augmented reality AND language learning; augmented reality AND humanities OR arts. Retrieved records were screened at the title and abstract level for relevance to AR in educational settings and then assessed in full text against the inclusion and exclusion criteria reported above.

For this review, we included peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and book chapters that (a) addressed AR applications in educational settings (from early childhood to higher and adult education, as well as informal learning), (b) reported empirical data and/or presented theoretical or design frameworks relevant to teaching and learning, and (c) were published in English. We excluded studies focusing exclusively on technical aspects (e.g., hardware optimization, tracking algorithms) without a clear educational component, as well as non-scholarly reports or commercial white papers.

The case studies presented in the subsequent sections were selected as illustrative examples using purposeful criteria: explicit links to learning theory, clear descriptions of AR features and the learning context, an empirical evaluation (e.g., learning, cognitive, or behavioral outcomes), and coverage across educational domains and levels. When multiple candidates met these criteria, preference was given to more recent and/or widely cited studies.

The analysis proceeded in two steps. First, studies were grouped by their educational contribution: (a) theory-informed learning mechanisms and instructional principles, (b) empirical applications and evidence across educational (e.g., STEM, humanities, and arts), and across educational levels, and (c) implementation, evaluation, and ethical/practical constraints. Second, within each group, the selected papers were examined to identify recurring themes, methodological trends, and gaps in the literature.

3. Exploring the Basics of Augmented Reality

3.1. Definitions and Differences Between Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Mixed Reality

AR can be situated within Milgram and Kishino’s Reality-Virtuality Continuum, where an AR image is defined as “any representation which involves the augmentation, or enhancement, of a real environment-based image with some kind of virtual (computer-generated) image content” (Milgram et al., 1994). AR, according to another common definition, is “the superimposition of digital elements (computer graphics, text, video, or audio) in the real world” (Azuma, 1997). Czok et al. (2023), integrating these perspectives, define AR as “a technology that supplements reality with digital content that is interactive, real-time, and functionally 3D-registered, accessible through handheld or wearable devices”. With AR, the real environment is “enriched” with computer-generated virtual objects that the user cannot manipulate. The user can observe and listen to sounds from the real environment. Devices used to access AR content include smartphones, tablets, computers, and Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) ‘open’ (like glasses with transparent lenses) (Pallavicini, 2020).

Although they are often confused with each other, AR differs from both Virtual Reality (VR) and Mixed Reality (MR) (Table 1). VR refers to a digital (computer-created) environment in which people are fully immersed and can interact. Stimuli from the outside world (visual and auditory) are not perceived, thanks to the use of ‘closed’ HMDs (goggles like diving masks, but with wholly obscured lenses) (Pallavicini, 2020). Instead, the term MR refers to a technology that presents real-world and virtual objects on a single display. Digital objects, unlike AR, do not overlap but are ‘anchored’ in and interact with the real environment and are manipulable by the user (Pallavicini, 2020).

Table 1.

Differences between AR, VR, and MR.

3.2. Origins and Evolution

AR has only recently gained widespread acceptance, but its origins—like those of VR—can be traced back to the early 1960s. In this period, Ivan Sutherland, a young researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston, developed “Sketchpad”, a primitive form of computer graphics that laid the foundation for the current graphical interfaces used in VR (Sutherland, 1964). In parallel, Morton Heilig patented “Sensorama”, a mechanical device that created an immersive, multisensory cinematic experience (Heilig, 1962), while Douglas Engelbart founded the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at Stanford University to develop computers and display systems to enhance human capabilities (Pallavicini, 2020). In 1968, Sutherland published a scientific paper entitled “The Ultimate Display”, describing a visor with interactive graphics and feedback devices, and developed the first HMD to immerse viewers in an artificial 3-D environment, known as “The Sword of Damocles” (Pallavicini, 2020).

The term “Augmented Reality” was coined in 1990 by Thomas Caudell and David Mizell, Boeing Company researchers who developed an HMD to simplify cable assembly, a complex and error-prone process (Caudell & Mizell, 2003). In the late 1990s, Feiner et al. (1997) created a roving machine for their university’s campus that combined 3D superimposed AR graphics with the mobility of mobile computing, using a head-worn 3D display and a portable 2D display with a trackpad to provide various information about the campus (Feiner et al., 1997). In the 2000s, experimental AR applications expanded into entertainment (e.g., early AR gaming concepts such as AR Quake), although high costs initially limited adoption beyond research settings (Das et al., 2017).

During the 2010s, AR became mainstream through smartphones, enabled by built-in cameras and GPS, and popularized by location-based and overlay-driven experiences, including the AR games Paranormal Activity: Sanctuary and Zombies, Run! (Das et al., 2017). At the same time, wearable AR reemerged through consumer and industrial initiatives (e.g., Google Glass), highlighting both the potential of always-available AR and the challenges of privacy, practicality, and public acceptance. The decade also saw the consolidation of MR headsets (e.g., Microsoft HoloLens) that supported spatial mapping and interactive holographic content, accelerating professional applications and strengthening interest in educational use cases (Sünger & Çankaya, 2019). A crucial year for the spread of AR was 2016, when Niantic, in collaboration with Game Freak, The Pokémon Company, and Nintendo, launched Pokémon Go. This mobile game uses geolocation and AR, drawing inspiration from the Pokémon video game series that began in 1996. In 2016, Pokémon Go became the mobile game of the year, with more than 650 million downloads and about 5 million active users, generating over $5 billion in revenue (Kumparak, 2017).

More recently, several models of AR-compatible HMDs—such as Microsoft HoloLens, the Magic Leap One, or the more recent Apple Vision Pro—have been released, becoming advanced, easy to use, and with a wider FOV (Field Of View), that is “the extent of the environment observable by the human eye” (Fang et al., 2023). Many technological advances have broadened the feasibility of AR across domains, including education (Waisberg et al., 2024a, 2024b), while also raising new questions about effective pedagogical integration, accessibility, and sustainable implementation.

4. Key Hardware Elements and Different Types of AR Systems

From an educational perspective, hardware and tracking choices matter primarily because they constrain key learning affordances (e.g., hands-free embodied interaction, in situ contextualization, shared workspaces) and the amount of extraneous cognitive load introduced by the interface. To keep the focus on education, the following overview is intentionally concise.

4.1. Displays

Hardware components of AR systems include displays, input devices, tracking, and computers (Carmigniani & Furht, 2011; Haneefa et al., 2024). Displays are subdivided according to the operational distance between the AR system and humans (from nearest to farthest) into (Fang et al., 2023):

Wearable AR: It uses HMDs (e.g., Apple Vision Pro, Microsoft HoloLens), which are devices worn on the user’s head and placed in front of the eyes to display three-dimensional digital content (Fang et al., 2023). HMDs for AR are characterized by leaving the user’s hands free, which is why they are widely used in areas including industry (Funk et al., 2016; Häkkilä et al., 2018), such as training specialized operators in the maintenance of complex machinery (Fang et al., 2023), and medicine (Eckert et al., 2019).

Mobile AR: Mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets for AR are enabled by the availability of powerful, low-cost hardware. For this reason and because of the low cost, this type of AR is the most adopted in the educational field (Al-Ansi et al., 2023). However, a significant disadvantage is that these devices require one or both hands for display and interaction (Carmigniani & Furht, 2011). Currently, the two main classes of portable AR displays are smartphones and tablets. Thanks to technological advances, smartphones combine powerful Central Processing Units (CPUs), cameras, accelerometers, GPS, and solid-state compasses, making them an exciting platform for AR. However, their small display size is not ideal for 3D user interfaces. Tablets offer more power than smartphones but are more expensive and heavier, making them less practical for prolonged one-handed use. Smartphones and tablets with AR capabilities (e.g., ARKit for iOS and ARCore for Android) enable these technologies. For example, by using apps such as HP Reveal and linking the AR content to a QR code, students can use their mobile device to activate a three-dimensional visualization. More versatile than bar codes, QR codes have recently become very popular for introducing AR to schools (Anderson, 2019).

Spatial Augmented Reality (SAR): This AR system projects graphic information directly onto physical objects, eliminating the need to wear displays. It does not require users to wear additional equipment, making it a compelling option for various industries (Bimber & Raskar, 2005; Carmigniani & Furht, 2011). Spatial displays integrate technology into the environment, allowing easy scalability for groups of users and facilitating collaboration (Fang et al., 2023). Unlike mobile and wearable AR, spatial AR systems do not require users to carry or wear devices, as the fixed infrastructure manages the tracking. This makes spatial AR particularly suitable for large-scale or public installations, such as those in museums or industrial settings (Carmigniani & Furht, 2011; Fang et al., 2023).

4.2. Tracking Systems

Tracking devices consist of digital cameras and/or other optical sensors, such as GPS, accelerometers, solid-state compasses, and wireless sensors (Arena et al., 2022). Each of these technologies has a different level of accuracy and depends significantly on the type of system being developed (Carmigniani & Furht, 2011). Wearable AR systems use cameras, depth sensors, accelerometers, and gyroscopes to map the environment and track head movements in real-time, ensuring precise positioning of virtual objects and enhancing immersion. They often use inside-out tracking to determine users’ positions without external markers. In contrast, mobile-AR systems rely on smartphone and tablet sensors—cameras, accelerometers, gyroscopes, and GPS—to overlay digital content on real-world images, dynamically adapting for applications such as navigation. Spatial AR systems take a different approach, using cameras, depth sensors, and external projectors installed in the environment. These systems map the physical space and track users’ movements within it. Cameras and sensors monitor position and gestures while a central computer dynamically processes the data to adjust the projected digital content.

Several researchers classified AR interfaces into two levels based on their tracking techniques. (Fan et al., 2020):

- Image-based AR: includes marker-based and markerless solutions that use image recognition techniques to track an object and its position.

- Location-based AR: uses position data to identify an object and its position (Cheng & Tsai, 2013; Koutromanos et al., 2015).

4.3. Input Devices

There are several types of input devices for AR systems, and the type of display and the applications primarily determine their selection for use (Arena et al., 2022; Carmigniani & Furht, 2011). In more detail, wearable AR systems feature gesture recognition sensors, voice commands, and controllers such as wands or rings for seamless interaction, making them ideal for industrial design, simulations, and collaborative tasks. On the other hand, mobile AR systems rely on touchscreen gestures (e.g., tapping and swiping) and built-in cameras for intuitive interaction. Voice commands and motion sensors enable hands-free operation, making them versatile for navigation, gaming, and retail. Finally, Spatial AR systems use external cameras, depth sensors, and sometimes motion-sensing gloves or handheld controllers for precise interaction. Voice recognition and environmental sensors enhance experiences in interactive installations, museums, and large-scale simulations, supporting multiple users in shared spaces.

4.4. Computer

AR systems require a robust CPU and ample Random Access Memory (RAM) to process images captured by the camera effectively (Carmigniani & Furht, 2011). Mobile-AR relies on built-in smartphone and tablet processors to manage cameras, accelerometers, gyroscopes, and GPS, seamlessly overlaying digital content on the physical environment. By contrast, wearable AR integrates optimized processors within HMDs. These handle the data stream from cameras, depth sensors, and motion trackers, ensuring precise tracking of movements and environmental details for a smooth, immersive experience. Spatial AR, in contrast, depends on a central high-performance computer connected to projectors and sensors installed in the environment. This system processes data to map physical spaces and dynamically adjusts holographic projections, enabling accurate, dynamic, large-scale AR experiences (Carmigniani & Furht, 2011).

5. Augmented Reality, Education, and Theories of Learning

5.1. From Embodied Interaction to Embodied Cognition

To understand the link between AR and learning, it is first necessary to delve into the concept of embodied interaction, as defined by Kay (1990) as a process of gradually integrating technology into the user’s body to make human–computer interaction as natural as possible (Biocca, 1997; Dourish, 2001). This perspective, known as “direct manipulation”, argues that people should interact with digital objects in the same way they manipulate physical objects, without having to learn new commands, by simply adapting their perceptual-motor patterns to the interface (Morganti & Riva, 2006).

AR and other immersive media (VR and MR) are regarded as the ultimate examples of the evolution of technological interfaces toward progressive embodiment (Biocca, 1997; Durlach & Mavor, 1995; Kay, 1990). This means that such systems seek to integrate the human body into interacting with the digital world, making the experience more natural and intuitive. This type of embodied interaction allows innate perceptual-motor skills to interact with the digital environment, creating a more direct and intuitive connection between the user and the technology.

Linked to the concept of embodied interaction, the focus on the user’s physical embodiment in interacting with digital objects is embodied cognition, which is also fundamental to understanding the links between AR and learning. Specifically, embodied cognition proposes that the mind and body are interconnected, with the body playing a crucial role in information processing and thinking (Damasio, 1994). Thought requires bodily mediation to originate and adapt to the body itself; in a word, it is “embodied.” This view of the relationship between mind and body belongs to a current of cognitive psychology developed in recent decades of the previous century, which arose to explain the organization of thought and the role of the body in this process: the “bodily” or “embodied” cognitive psychology (A. Clark, 2008; Varela et al., 1991). This theoretical perspective developed in open opposition to computational cognitive psychology, popular in the 1940s and 1950s, which viewed the mind as a “huge computer,” a processor of sensory information into symbolic representations (Fodor, 1983). In contrast, embodied cognitive psychology argues that the organization of thought cannot be understood without the contextualized experience of a body-environment system (A. Clark, 2008; Shapiro, 2010).

Embodied cognitive psychology is inspired by phenomenological philosophy, particularly the ideas of Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Heidegger was one of the first to highlight the importance of the body in thought (Heidegger, 1927), while Merleau-Ponty described the body as the “medium through which men conceive the world in its totality” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945). According to embodied cognitive psychology, the body acts as a mediator of all experiences, functioning both as a processing system for the information gathered and as a framework for the neural processes of the mind (Bechara & Damasio, 2005; Damasio, 1994). The concept is also highlighted in Conceptual Metaphor Theory, which emphasizes that our knowledge of the world is embodied, that is, constructed based on bodily experiences in the surrounding environment (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980).

5.2. Situated Learning, Experiential Learning, and the Contiguity Principle of Multimedia Learning

Embodied cognition emphasizes how thinking arises from the contextualized interaction between the body and the environment, aligning closely with the principles of the critical learning theories described below. In practical terms, an embodied perspective suggests that learning benefits are most likely when AR supports purposeful sensorimotor coupling, allowing learners to manipulate anchored virtual objects, move around them, and receive immediate feedback. To prevent interaction from becoming an end in itself, embodied AR activities should be aligned with explicit learning goals such as spatial reasoning or procedural understanding and should include brief prompts that direct attention to relevant features, for example, by asking learners to compare what changes before and after an action.

Situated Learning Theory: The latter argues that learning is inextricably linked to the social and physical context in which it occurs, emphasizing the importance of hands-on interaction and direct experience in knowledge acquisition (Lave & Wenger, 1991). This theoretical framework underscores that knowledge is not an abstract entity to be acquired passively but rather a social process that develops through active participation and practice within a community. For example, in an apprenticeship, learning occurs through observation and immersion in the practices and discourses of the professional community, enabling students to acquire skills in a natural, integrated way.

AR can create situated learning environments where students interact with digital content in their physical surroundings, enhancing their understanding through direct, contextualized engagement. Contextual visualization presents virtual information in a real-world context, helping students build knowledge while learning about interactivity and enabling bodily interactions with virtual content. Previous studies have shown that these features increase student motivation and foster various educational applications (Teng et al., 2017). For example, in an educational context, students can explore 3-D models of molecular structures, solar systems, or historical reconstructions, thereby facilitating deeper, more meaningful learning (Bacca et al., 2014). AR enables learners to engage in authentic tasks that reflect real-world practices, thereby supporting the situated learning model (Bower et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2020). From a situated learning lens, the educational value of AR depends on whether contextual augmentation is integrated into an authentic task structure rather than presented as contextual decoration. This typically requires clear goals and role expectations, structured guidance through checklists, prompts, and progressive disclosure, and a debriefing phase that connects in-context experience to abstract concepts.

- -

- Case Study: Santos et al. explored AR applications for situated vocabulary learning, leveraging multimedia learning theory to design an AR system for handheld devices (Santos et al., 2016). Their study focused on developing and evaluating AR applications for learning Filipino and German vocabulary in authentic contexts. The AR system allowed users to interact with virtual content, including text, images, audio, and animations, superimposed onto the real environment. Compared to non-AR methods, AR-supported learning improved vocabulary retention and enhanced motivation, attention, and satisfaction (Santos et al., 2016). This case study highlights a key boundary condition: situated vocabulary gains are more likely when AR cues closely match the learner’s perceptual context and multimedia elements are integrated to minimize split attention.

Experiential Learning (Kolb et al., 2000): It is based on the idea that direct experience is the core of the learning process. According to Kolb, learning is a continuous cycle comprising four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Kolb et al., 2000). This model emphasizes the importance of having practical experience and reflecting on it to transform it into applicable knowledge. For example, in a science laboratory, students observe and actively experiment with phenomena, reflect on the results, and apply the new knowledge to real problems.

AR enhances experiential learning by merging real and virtual environments, enabling students to interact with virtual objects and engage in realistic simulations. This approach fosters a cycle of experience, reflection, and application, enabling students to understand complex concepts better through direct interaction. Students can work together to tackle problems, exchange ideas, and build knowledge more dynamically and engagingly. By incorporating AR into experiential learning, traditional teaching methods can be transformed, offering new opportunities for active and immersive educational experiences (Teng et al., 2017).

In experiential learning terms, AR is most effective when it supports the whole learning cycle, moving from concrete engagement to guided reflection, conceptualization, and active experimentation, rather than merely offering an immersive experience. This implies structuring activities so that learners first engage with a task, then reflect through prompts, link their observations to underlying concepts, and apply what they learned in a new attempt. Collaboration should also be deliberately structured through roles and explicit peer-feedback criteria rather than assumed to emerge spontaneously.

- -

- Case Study: Wu and Huang investigated the application of AR in an interactive design course to foster experiential and situated learning (C. Wu & Huang, 2020). Their study involved 62 university students divided into 17 groups tasked with designing AR applications. The course was structured around key activities, including case analysis, project planning, peer reviews, and performance presentations. Grounded in Kolb’s experiential learning theory and the situated learning model, the instructional design emphasized real-world contexts and collaboration. Results revealed that 15 of 17 groups successfully integrated AR technology with prior knowledge, creating applications such as games and educational tools. Students reported improved creativity, teamwork, and understanding of AR technologies (C. Wu & Huang, 2020). Notably, this type of design-focused task may have its greatest impact on higher-order outcomes, such as creativity, teamwork, and design competence, which are often undermeasured in AR research. More detailed reporting of group processes, including collaboration quality and the content of peer feedback, as well as implementation conditions such as teacher facilitation, time constraints, and technical reliability, would help explain variability across groups and improve reproducibility in classroom settings.

Contiguity Principle of Multimedia Learning (R. C. Clark & Mayer, 2011; Mayer, 2009): This principle emphasizes aligning text with corresponding graphics or objects, meaning that text should not be physically separated from the visuals it describes. Applied to AR, the contiguity principle implies that overlays should be placed as close as possible to the referent objects and introduced at the moment they become instructionally relevant. However, AR interfaces can also increase extraneous load through clutter, redundant labels, or competing visual cues. Therefore, design should emphasize minimal essential overlays, signaling (highlight what matters), and segmentation (progressive disclosure). Evaluation should combine learning outcomes with cognitive-efficiency indicators such as perceived load, task time, and error rates, since contiguity benefits often emerge as reduced split attention and more efficient processing rather than higher immediate scores alone.

AR technology can create a visualization tool for electromagnetic fields, which are typically invisible to students (Buchau et al., 2009; Ibáñez et al., 2014). In such a system, AR overlays a visual representation of the electromagnetic field in the real world, allowing students to see and understand its spatial distribution. Students can gain a more intuitive grasp of abstract, difficult-to-comprehend concepts by visualizing electromagnetic fields directly in their surroundings. This hands-on interaction with the augmented visuals helps bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical understanding, making the learning process more engaging and effective (Teng et al., 2017).

- -

- Case Study: Krüger and Bodemer investigated the application of multimedia design principles in AR learning environments, focusing on the spatial contiguity and coherence principles (Bacca-Acosta et al., 2022). Two studies examined the impact of these principles on cognitive load and knowledge acquisition. In the first study, with 80 participants, researchers examined the spatial integration of virtual and physical elements in AR. Participants experienced an integrated or separated design, with virtual textual information either overlaid on real-world visuals or presented separately on a tablet. Results suggested minor improvements in reducing extraneous cognitive load and enhancing performance with integrated designs, though most effects were not statistically significant. The second study, involving 130 participants, explored the coherence principle by manipulating the addition of matching or non-matching virtual sounds in an AR environment. Contrary to expectations, non-matching sounds did not significantly increase cognitive or task load compared to matching or no sounds (Bacca-Acosta et al., 2022).

5.3. Constructivism, Sociocultural Theory, and Connectivism

In addition to the theories listed in the preceding paragraphs, other conceptual frameworks are particularly interesting concerning the use of AR for education, specifically (Zhang et al., 2020):

Constructivism: First coined by Piaget and later developed by Vygotsky, this perspective posits that learners actively construct their understanding and knowledge of the world through experiences and reflection (Bruner, 1997; Dewey, 1916; Jonassen, 1991; Piaget, 1973). This theory emphasizes that learning is an active, constructive process where the learner builds on prior knowledge to create new understandings (Dewey, 1916).

In the context of AR, constructivism is particularly relevant, as this technology enables the overlay of digital information in the real world, providing an interactive and immersive learning experience (M. Wang et al., 2018). This model aligns with the principles of constructivism, emphasizing active, experience-based, and collaborative learning (Afnan & Puspitawati, 2024; Techakosit & Wannapiroon, 2015). AR facilitates knowledge construction by bridging theoretical understanding and practical applications, improving student engagement and motivation (Y. W. Chen et al., 2019). Constructivism is particularly useful in fields like STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), where practical, experiential learning is essential for skill development (Hsu et al., 2017; Ibáñez & Delgado-Kloos, 2018; Sırakaya & Alsancak Sırakaya, 2022).

From a constructivist standpoint, AR is expected to be most effective when it supports learners’ active meaning-making, allowing students to explore, test ideas, and revise their understanding based on feedback rather than passively consuming overlays. This implies designing AR tasks as guided inquiry or problem-based activities with explicit prompts, opportunities for comparison and iteration, and a structured debrief to connect exploration to formal concepts. Accordingly, evaluation should go beyond immediate factual performance and include indicators of conceptual understanding and transfer (e.g., explanation quality, application to novel cases), as well as process measures that reflect constructive activity (e.g., strategy use, interaction traces), since “engagement” alone does not guarantee knowledge construction.

- -

- Case Study: Safadel and White explored the use of AR in teaching molecular biology, emphasizing its potential to improve the visualization and comprehension of complex 3D macromolecular structures (Safadel & White, 2019). The study involved 60 university students randomly assigned to either a traditional 2D instructional condition or an AR-enhanced environment. In the AR condition, students used mobile devices to interact with 3D models of molecules, such as DNA, enabling them to rotate, manipulate, and observe structures from multiple perspectives. This AR approach aligned with constructivist and situated learning theories, as it engaged students in active exploration and contextualized learning tasks. Results demonstrated that students in the AR group reported higher satisfaction and usability, and a better understanding of molecular structures, than those in the 2D group (Safadel & White, 2019). This study also points to a key boundary condition for constructivist AR: benefits are more likely when exploration is scaffolded, and learners are prompted to articulate what the visualizations imply, rather than simply manipulating models superficially.

Sociocultural Theory: Originally developed by Lev Vygotsky, this theoretical perspective emphasizes the fundamental role of social interaction in the development of cognition (Vygotsky, 1978).

AR technologies enhance sociocultural learning by facilitating collaborative and interactive experiences (Dunleavy et al., 2009; Hellermann et al., 2017; H. Y. Wang et al., 2017). For instance, to facilitate learning a foreign language, AR can create scenarios in which learners interact with virtual characters or peers in real time, practicing language skills in contextually rich environments (Godwin-Jones, 2016; Hellermann et al., 2017; Sydorenko et al., 2019). A sociocultural lens highlights that AR is not only a representational tool but also a mediational means that can shape joint attention, dialogue, and participation. From an educational perspective, this means that collaborative AR activities should be deliberately structured by defining roles and interdependence, embedding prompts for dialogue and negotiation, and providing teacher facilitation or system scaffolds to sustain productive interaction, particularly in heterogeneous groups. Outcomes should therefore include measures of collaboration quality (e.g., interaction patterns, communication/argumentation quality, equitable participation) in addition to learning gains, since the mechanism of change is mediated social interaction rather than exposure to content alone.

- -

- Case Study: Teo et al. (2022) explored the application of an AR game to improve comprehension of English for Medical Purposes (EMP) among 240 Asian medical undergraduates aged 19–21 (Teo et al., 2022). The AR games integrated multimedia elements into real-life healthcare scenarios, allowing students to practice listening and reading comprehension collaboratively under teacher guidance. AR games created real-life-like scenarios for students to practice comprehension collaboratively, integrating verbal and non-verbal cues to simulate professional contexts. This approach facilitated shared responsibility for learning and enhanced cognitive processes, mainly when students of varying proficiency levels collaborated in heterogeneous groups. The study emphasized that teacher immediacy—close interpersonal communication with students—reduced psychological distance and improved engagement, aligning with the sociocultural focus on mediated learning through interaction (Teo et al., 2022). This case study is particularly informative in showing that teacher-related variables, such as guidance, immediacy, and classroom facilitation, can be decisive implementation conditions for AR-supported collaboration.

Connectivism: Introduced by George Siemens and Stephen Downes (Downes, 2007; Siemens, 2004). Connectivism is a learning theory for the digital age that emphasizes the role of social and technological networks in learning (Greenwood & Wang, 2018; M. Wang et al., 2018). According to this theoretical framework, knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and learning involves the ability to construct and traverse those networks (Downes, 2007).

AR facilitates connectivist learning by allowing learners to access and interact with various digital resources and networks (Greenwood & Wang, 2018; Techakosit & Wannapiroon, 2015; M. Wang et al., 2018). For example, AR can be integrated with other digital tools to create a rich, interconnected learning environment that enhances collaboration and knowledge-sharing (Alam & Mohanty, 2023; Zamiri & Esmaeili, 2024). In addition, AR can support collaborative learning environments, where learners work together to solve problems and achieve common learning goals, thereby fostering a community of practice essential for cognitive development (Greenwood & Wang, 2018).

Within a connectivist perspective, the learning benefit of AR lies less in immersion and more in enabling learners to access, navigate, and contribute to distributed knowledge resources through networked tools. This suggests designing tasks that require learners to search, curate, and share information, connect evidence across sources, and reflect on how their network supports understanding (e.g., creating annotated AR-linked resources, peer knowledge-sharing workflows). Evaluation should include outcomes sensitive to networked learning—such as information literacy, quality of resource curation, knowledge-sharing behaviors, and collaboration patterns—alongside domain achievement, as these indicators capture the core connectivist mechanism.

- -

- Case Study: Techakosit and Wannapiroon (2015) investigated the design and evaluation of a connectivism learning environment integrated into an AR science laboratory to enhance scientific literacy. The study was conducted in two phases: designing the AR-based learning environment and evaluating its suitability with the input of seven experts in connectivism, AR, and scientific literacy. The AR learning environment was structured around four key components: the learning environment, a process to enhance scientific literacy, environmental characteristics, and measures to foster scientific literacy. The design emphasized connectivist principles, where learners engage in a networked environment to share, research, and reflect on scientific concepts. The AR component enabled students to perform hands-on experiments, collaborate in real time, and visualize complex scientific concepts interactively. Expert evaluations highlighted the environment’s suitability, with ratings indicating a high potential to promote problem-solving skills, collaborative learning, and a deeper understanding of science. The study concluded that integrating AR into science education fosters scientific literacy by bridging theoretical concepts with practical, technology-mediated experiences (Techakosit & Wannapiroon, 2015). Because this case study emphasizes design and expert evaluation, it also underscores the importance of examining implementation and learning effects in authentic classroom settings.

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT): This conceptual framework emphasizes the role of working and long-term memory in learning, highlighting how excessive cognitive load can hinder information processing and retention (Chandler & Sweller, 1991; Moreno, 2004; Sweller et al., 2011). CLT categorizes cognitive load into intrinsic (i.e., related to task complexity and prior knowledge), extraneous (i.e., linked to instructional design), and germane (i.e., effort for schema construction) (Chandler & Sweller, 1991; Sweller, 1988). Effective instructional materials should minimize extraneous load and optimize germane load by using strategies such as segmenting information, integrating multimedia, and employing visual aids (Mayer, 2012).

AR supports CLT by breaking complex concepts into manageable parts, aiding schema construction, and interactive learning. However, poorly designed AR can increase extraneous load, underscoring the need for careful design to balance engagement and cognitive efficiency segments (Buchner et al., 2022; Dunleavy et al., 2009; Elford et al., 2022). From a CLT standpoint, AR improves learning by reducing extraneous processing (e.g., split attention, complex spatial integration) and by supporting germane processing through well-timed guidance and coherent multimodal integration. This implies minimal essential overlays, segmentation/progressive disclosure, and scaffolding calibrated to prior knowledge (novices typically benefit from stronger guidance, whereas experts may require less). Significantly, CLT predicts that null or negative effects can arise when interaction friction, tracking instability, or dense overlays increase extraneous load. Therefore, studies should explicitly measure cognitive load (ideally distinguishing extraneous from intrinsic demands) and report usability/technical breakdowns, alongside achievement and transfer, to interpret heterogeneous outcomes.

- -

- Case Study: A practical example of an AR application concerning CLT can be seen in a study conducted by Küçük et al., which evaluated an AR application named “MagicBook” (Küçük et al., 2016). Seventy second-year medical students were divided into experimental and control groups. The experimental group used the “MagicBook” to learn neuroanatomy, while the control group used traditional learning methods. The “MagicBook” integrates traditional printed books with AR technology using mobile devices. Students interact with the book by scanning visual markers on the pages using the Aurasma app on their mobile devices. This interaction superimposes multimedia content, such as 3D animations and videos, onto the book pages, allowing students to visualize anatomical structures dynamically and interactively. The results showed that the “MagicBook” students achieved higher academic performance and reported lower cognitive load than the control group. The AR application helped make abstract anatomical concepts more concrete, reducing the mental effort required to understand these concepts. The “MagicBook” enabled information processing through visual and verbal channels, enhancing knowledge transfer to long-term memory (Küçük et al., 2016). This example illustrates how AR can function as an integration tool by aligning visual and verbal information and making spatial relations more concrete, which is consistent with reduced extraneous cognitive load.

6. Educational Topics Addressed by AR and Targeted Age Groups

6.1. Growth in the Number of Studies on AR in Education

Since its introduction 50 years ago, AR technology has been adopted across various fields, including the military, medicine, engineering, and education (Sirakaya & Cakmak, 2018). Research on AR in education has experienced significant growth over the last few decades, with distinct periods of development reflecting technological advancements and increased adoption in educational contexts (Garzón et al., 2021). According to Garzon and colleagues, the evolution of AR in education can be categorized into three generations (Garzón et al., 2021):

Early Development and Initial Growth (1995–2009): The early phase of AR research in education, referred to as the “hardware-based AR” period, spanned from 1995 to 2009. During this latency phase, the focus was primarily on developing AR delivery technologies, such as HMDs and other specialized hardware. Research growth was slow, laying the foundation for future applications but limited by the high cost and complexity of the technology (Garzón et al., 2021).

Application-Based AR Era (2010–2019): The year 2010 marked a turning point for AR in education, with an inflection toward exponential growth. This period, often described as the “application-based AR” era, saw AR technologies becoming more accessible through mobile applications. Events such as the release of Google Glass in 2014 and the global success of Pokémon Go in 2016 drew significant attention to AR, inspiring developers and educators to explore its potential in educational settings (Garzón et al., 2021). From 2011 to 2016, AR research growth was steady but not exponential. However, between 2017 and 2019, the number of studies increased significantly, reflecting growing interest in AR as an educational tool. Studies during this phase focused on leveraging mobile-AR platforms, which became dominant in education AR adoption (Al-Ansi et al., 2023).

Exponential Growth and Modern Developments (2020–today): The most significant increase in educational research on AR has occurred since 2020. According to a recent review, the number of papers published in these three years exceeded the total number of studies conducted from 2011 to 2019 (Al-Ansi et al., 2023). This rapid growth aligns with advancements in dedicated AR devices such as HMDs, WebAR technologies (i.e., AR experiences that are accessible directly through a web browser, without the need for downloading dedicated apps), and Artificial Intelligence (AI) integration. These innovations have broadened the scope and accessibility of AR applications in education, supporting diverse learning environments and disciplines.

Regarding the distribution in countries and institutions of the studies on AR in education, the United States leads in the number of studies (347), followed by Spain (273), Taiwan (114), China (113), and Germany (110) (Garzón et al., 2021). Prominent AR research institutions include the State University System of Florida, the University of La Laguna, and Harvard University. English remains the dominant publication language, accounting for 1898 studies, followed by Spanish, Portuguese, German, and Russian (Garzón et al., 2021).

6.2. Domains and Target Ages of AR Studies for Education

AR has been widely studied and implemented across diverse educational contexts, demonstrating its adaptability across subjects. Its application extends beyond traditional classrooms to settings such as museums and science centers (Scavarelli et al., 2021). Between 2010 and 2015, research on AR focused mainly on STEM disciplines, accounting for nearly half of the studies (Bacca et al., 2014). In contrast, only about 22 percent of studies focused on utilization in the Humanities and the Arts (Majid & Salam, 2021). However, since 2016, with the influence of companies such as Google and Snapchat that have helped popularize AR and VR technologies, there has been a significant increase in studies on the use of AR in these humanistic disciplines as well (Majid & Salam, 2021). AR solutions for teaching STEM subjects and in the Humanities and Arts will be examined below.

STEM Disciplines: Studies over the last decade have highlighted that AR applications have been particularly prevalent in STEM education (Hsu et al., 2017; Ibáñez & Delgado-Kloos, 2018; Sırakaya & Alsancak Sırakaya, 2022), where students often struggle to apply reasoning skills to abstract concepts requiring advanced spatial visualization (Sahin & Yilmaz, 2020). The reliance on rote memorization and limited conceptual understanding further inhibits the development of critical thinking skills. AR addresses these challenges by transforming abstract ideas into tangible, interactive representations, improving spatial ability, practical skills, and conceptual understanding. Its integration of computerized content with real-world visuals captures students’ attention, enhances motivation, and fosters both physical and cognitive immersion, enabling collaborative exploration of complex theories (Hsu et al., 2017; Ibáñez & Delgado-Kloos, 2018; Sırakaya & Alsancak Sırakaya, 2022). This immersive approach improves the quality of education and helps students develop critical skills and knowledge more effectively and efficiently than traditional technology-enhanced learning environments (Hsu et al., 2017; Ibáñez & Delgado-Kloos, 2018; Sırakaya & Alsancak Sırakaya, 2022). In the context of AR applications in STEM education, research spans various disciplines, with studies focusing on physics (31.58%), natural sciences (26.32%), mathematics (15.79%), chemistry and astronomy (10.53%), and general science (5.26%) (Ajit et al., 2021). Additionally, the settings for these studies vary, with most conducted in classrooms (52.63%), followed by virtual laboratories (15.79%), field trips (21.05%), and museum environments (10.53%) (Ajit et al., 2021). In STEM, AR studies most often evaluate learning using pre/post achievement tests, concept-understanding measures, and spatial-ability tasks, frequently complemented by motivational and attitude scales. Typical designs rely on mobile, marker-based, or tablet AR that supports interactive 3D visualization, guided inquiry, and manipulation of otherwise abstract entities. Overall effects are commonly positive for conceptual understanding and engagement, while results are more mixed for transfer and longer-term retention when activities are brief or under-scaffolded. Recurring constraints include usability friction, visual clutter that can increase cognitive load, and technical instability that interrupts learning. Accordingly, STEM evaluations would benefit from routinely reporting cognitive efficiency indicators and including delayed and transfer tests alongside immediate performance. The following are some examples of the use of AR in teaching various STEM subjects:

- -

- Physics: AR can be helpful for physics teaching by offering digital and visual tools that make complex concepts more accessible and concrete (Cai et al., 2013, 2017; Fidan & Tuncel, 2019). For instance, a recent study on 91 students aged 12–14 evaluated the effectiveness of “FenAR”, a marker-based AR software designed to make challenging notions such as force, energy, pressure, and work more accessible. Through tablets, students interacted with realistic three-dimensional models, manipulating virtual objects and observing details from different angles. FenAR also allowed students to explore concepts such as weight and mass in various environments, including on the moon or Mars, thereby facilitating a practical understanding of theoretical ideas. Results showed that students who used AR performed significantly better on learning tests and retained learned concepts longer (Fidan & Tuncel, 2019).

- -

- Natural Sciences: By enabling students to visualize complex phenomena, such as biological cycles, ecosystems, and natural processes, through dynamic three-dimensional models, AR facilitates understanding abstract concepts, stimulates curiosity, and promotes more engaging and accessible learning. For example, a study by Sahin and colleagues involved 100 students aged 12 to 13 from two public middle schools to test their attitudes toward AR applications (Sahin & Yilmaz, 2020). The participants, who had never used AR before, were divided into two groups: an experimental group and a control group. Students in the experimental group studied the module “The Solar System and Beyond” utilizing AR-based teaching materials. These materials consisted of an activity booklet enhanced by educational videos, three-dimensional images of the planets, and key information obtained from the Morpa Campus website. During the lecture, students could interact directly with the 3D representations of the planets and constellations. At the same time, virtual objects were projected onto the whiteboard to create a synchronized, engaging learning environment. Meanwhile, the control group followed the same topic through traditional methods based solely on textbooks and face-to-face lectures. Students in the experimental group performed significantly better on the course evaluation test than their peers in the control group. In addition to academic improvements, the use of AR also positively impacted students’ attitudes toward the subject, making learning more interesting and challenging (Sahin & Yilmaz, 2020).

- -

- Math: Numerous studies have investigated AR solutions for teaching mathematics, particularly for visualizing 3-D graphs or solving geometric problems (J. W. Lai & Cheong, 2022). For example, Kounlaxay et al. studied 40 undergraduate engineering students at Souphanouvong University in Laos to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching three-dimensional geometry in mathematics. Students tried “GeoGebra AR”, an application that allows them to create, visualize, and manipulate three-dimensional geometric objects in a real-world context. During the lessons, students could interact with solid figures such as cubes, cylinders, cones, and prisms, observing how parameters, such as height and radius, affected volume calculations in real time, allowing them to modify the shapes and see the results immediately (Kounlaxay et al., 2021).

- -

- Biology: AR for studying anatomy or processes takes advantage of the unique features of this technology to enable students to visualize complex structures, such as the human body or biological processes, in a three-dimensional and detailed cellular manner (e.g., Afnan & Puspitawati, 2024). An example conducted in this area is the study by Fuchsova, which involved 61 first-year college students in a program for future teachers (Fuchsova & Korenova, 2019). The goal was to improve comprehension of human anatomy using interactive AR applications installed on tablets: “Anatomy 4D” and “The Brain iExplore”. “Anatomy 4D” allowed users to explore the human body in 4D, visualizing body systems in detail to better understand the relationships between organs and physiological processes. On the other hand, “The Brain iExplore” focused on the brain, showing its reactions to sounds and allowing students to delve into functions such as short-term memory through interactive games. During the sessions, students integrated AR applications with traditional textbooks and smartphone research, making learning more flexible. Results showed significant improvement in understanding and memorization of concepts, increased motivation, and development of clinical skills. The immersive and interactive experience provided by AR made learning more engaging (Fuchsova & Korenova, 2019).

Humanities and Arts: In subjects such as history, literature, and languages, students often face challenges connecting abstract concepts, distant historical events, or cultural contexts to their lived experiences. Traditional methods relying heavily on text-based resources can limit engagement and comprehension, especially when visual or experiential learning could better convey complex ideas. AR offers a transformative approach by immersing students in interactive, context-rich environments that bring historical events, literary worlds, and cultural settings to life (Barrile et al., 2019; Challenor & Ma, 2019; Gherardini et al., 2020). For instance, AR applications can reconstruct historical landmarks, visualize ancient artifacts, or simulate cultural experiences, making abstract or distant subjects more tangible and relatable (C. A. Chen & Lai, 2021). This engagement captures students’ attention and deepens their understanding and retention of content. Furthermore, AR fosters critical and creative thinking by encouraging students to interact with and interpret dynamic representations of texts, artifacts, or environments. By bridging the gap between abstract ideas and real-world applications, AR enhances the quality of humanities education, promoting greater engagement, more profound comprehension, and a more immersive learning experience (Barrile et al., 2019; Challenor & Ma, 2019; Gherardini et al., 2020).

Across the humanities and arts, AR is typically used to make distant cultural, historical, or textual content experientially “present” through contextual reconstruction, narrative augmentation, or location-based guidance. Outcome measures often combine comprehension tests with engagement, interest, sense of place, empathy, or reflective skills. Most studies report increased motivation and richer understanding when AR is embedded in meaningful interpretive tasks and followed by structured reflection. Effects are weaker when AR is used mainly as a visualization add-on. Typical constraints include novelty-driven engagement, uneven attention allocation between real and virtual cues, and logistical demands in the settings.

The following are some examples of the use of AR in teaching different humanities subjects:

- -

- History and Archaeology: With the ability to recreate historical settings, visualize archaeological artifacts in 3D, and integrate contextual information, AR permits exploration of events and places with a level of interactivity and engagement that is difficult to achieve with traditional methods (Barrile et al., 2019; Challenor & Ma, 2019; Gherardini et al., 2020). AR not only facilitates understanding of complex historical events but also promotes historical empathy, helping students connect emotionally with figures and places from the past (C. A. Chen & Lai, 2021). AR applications used at archaeological sites or museums enrich learning, transforming visits into educational experiences that combine technological innovation and cultural insight (Challenor & Ma, 2019). For example, in a study by Chang and colleagues, 87 first-year university students from the Department of Tourism and Leisure in Taiwan participated in a guided tour of historic sites using three modes: an advanced AR app, an audio guide, and no media. The AR allowed them to identify buildings and provide real-time historical information. The results showed a significant improvement in test scores and “Sense of Place” (historical empathy and sense of belonging) in the AR group compared to the others, highlighting that AR is more effective than audio in engaging students and improving learning (Chang et al., 2015).

- -

- Literature: By overlaying digital virtual elements with traditional texts, AR allows students to view animated scenes, explore narrative settings, and interact with story characters, transforming reading into an immersive experience. This approach stimulates students’ imagination and interest and facilitates a deep understanding of texts, developing narrative, critical, and emotional skills in a more dynamic and accessible way than traditional methods. For example, a study by Nezhyva and colleagues explored the use of AR to improve comprehension and interaction with literary works among elementary school children (Nezhyva et al., 2020).

- -

- Foreign Languages: Although the adoption of AR for language learning is still in its early stages, it has shown great potential in assisting learners and educators (Mohd Nabil et al., 2024). According to Larchen Costuchen et al. (2020), AR has proven to be a valuable tool for creating innovative materials and immersive educational technologies for second-language learning, such as AR books (Cheng, 2017), AR flashcards (Tsai, 2018; Yaacob et al., 2019), and AR games (Hu et al., 2022). A significant finding of their study was that incorporating immersive AR experiences into familiar physical environments enhanced vocabulary retrieval performance among twenty-first-century college students learning a second language. Additionally, Y. W. Chen et al. (2019) observed that students exhibited high motivation to learn through contextualized AR-enhanced learning. Skilled learners showed increased motivation in self-efficacy, proactive learning, and perceived learning value.

- -

- Arts: AR is also transforming art education, offering innovative tools to explore artworks, places, and concepts in an interactive, immersive way. Through AR, students and visitors can view hidden details, interact with digital reconstructions, and delve into historical and cultural contexts, making art learning more accessible, engaging, and personalized. For example, in a study on augmented museum experiences, AR enriched Van Gogh’s painting “Starry Night” with visual effects (twinkling stars, reflections on water) and floating descriptive text. Questionnaires showed that verbal elements (descriptions) had a more significant impact on user engagement and willingness to pay for similar experiences, highlighting the importance of relevant informational content- rather than visual effects alone (He et al., 2018). Moreover, a study at the Acropolis Museum in Athens used mobile devices to augment exhibits with AR, creating interactive narrative experiences. Features included videos, games, audio narratives, and digital reconstruction. Although the results have not been published, visitors expressed interest in using AR to get more information about the exhibits (Keil et al., 2013).

Importantly, research suggests that AR can be effective for students of all ages, with applications and instructional strategies tailored to the specific age group. This adaptability reassures educators and researchers that AR can be a versatile tool in learning (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2017; Parmaxi & Demetriou, 2020). The adaptability of AR makes it suitable for learners of all age groups, addressing diverse educational needs across various stages of education (Liono et al., 2021):

Kindergarten and Early Childhood Education: AR has proven helpful for young children, primarily through playful activities, interactive educational games (flashcards, puzzles, and matching cards), and artistic activities. These tools help children acquire basic knowledge playfully and engagingly, enhancing learning and the memorization of new concepts (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2017; Parmaxi & Demetriou, 2020). AR is often used with this age group to make learning vocabulary and language skills more interactive and visually stimulating through three-dimensional presentations, which make the content more concrete and memorable (Bacca et al., 2014). However, the role of parents and teachers is crucial in facilitating the effective use of AR at this age (Oranç & Küntay, 2019). Despite the apparent benefits, studies on this age group remain limited (e.g., Aydoğdu, 2022; Zulhaida Masmuzidin & Azah Abdul Aziz, 2018).

Elementary School Education: AR has proven particularly effective in teaching science and other fundamental subjects. AR-based tools allow complex concepts to be visualized concretely and three-dimensionally, making subjects such as astronomy, biology, and geography more accessible and engaging (Gün & Atasoy, 2017; Hidayat et al., 2021). For example, AR can provide 3-D representations of celestial objects, planets, or natural phenomena, transforming abstract topics into visual and interactive experiences that facilitate understanding (Liono et al., 2021). In addition to science, AR can support learning in reading, math, and language through playful activities such as interactive games and simulations. Animated visualizations and immersive environments stimulate curiosity, enhance student motivation, and promote longer-lasting learning. Integrating visual and hands-on elements helps students understand key concepts, consolidating their learning journey in a more dynamic context than traditional methods. Due to its interactive nature, AR also promotes the development of cognitive and social skills by encouraging collaboration among students through group activities and exploration-based projects. The use of this technology not only makes learning more engaging but also helps form a solid foundation for science and language competencies (Hidayat et al., 2021).

Middle School and High School Education: At these levels, AR is a valuable support for the study of complex subjects such as biochemistry, ecology, and vocational education. With interactive modules and detailed visualizations, AR simplifies complex concepts and makes content more accessible to students (Liono et al., 2021). In addition, integrating AR into laboratories has improved efficiency, allowing students to complete tasks faster than traditional methods. AR also explores literary texts, simulates conversations, and improves content comprehension through games and educational activities. Additionally, AR’s integration into laboratory sessions has enhanced efficiency, allowing students to complete tasks faster than with traditional methods (Liono et al., 2021).

Higher Education: AR is widely implemented in university education, especially in STEM disciplines. College students benefit from AR’s ability to visualize complex systems and processes, deepening their understanding of specialized arguments (Eckert et al., 2019). AR is also used in advanced language-learning contexts, such as professional simulations and role-plays, to prepare students for real-world academic and work situations (Majid & Salam, 2021). The high participation of college students in AR studies is attributed to their familiarity with mobile devices, the availability of student samples, and their ability to provide constructive feedback on AR applications (J. W. M. Lai & Bower, 2019; Mei & Yang, 2019).

7. Discussion

7.1. Enhancing Education Through Augmented Reality: Opportunities and Advancements

AR has proven to be a powerful tool for improving student engagement and motivation, increasing student enthusiasm for learning (Al-Ansi et al., 2023; Garzón et al., 2021; Godoy, 2020; H. K. Wu et al., 2013). These activities make learning more dynamic and engaging than traditional methods. In addition, AR allows students to personalize learning: students can interact with the content in a way that suits their learning style and pace. Furthermore, through AR applications, it is possible to receive immediate and personalized feedback, enhancing comprehension and the ability to translate the information learned (AlNajdi, 2022; W. T. Wang et al., 2022). AR can also be integrated with other digital tools to create richer and more diverse educational experiences. For example, AR applications can be combined with e-learning and social media platforms, fostering collaboration between students and teachers (Al-Ansi et al., 2023) and opening new opportunities for interactive and collaborative learning. An additional benefit of AR is the flexibility of access to learning materials, which can be used anytime, anywhere. This feature reduces dependence on the physical presence of teachers and promotes autonomous, continuous learning adaptable to students’ individual needs (Al-Ansi et al., 2023; AlNajdi, 2022).

Interactivity is another crucial aspect of AR. Students can explore content through animations, videos, and simulations, making learning more engaging and stimulating (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2017; Bacca et al., 2014). Already in one of the first reviews of the use of AR in education, published in 2013, the authors noted that the main benefits of AR lie in its ability to foster three-dimensional visualizations that support authentic, situated, collaborative, and immersive learning opportunities (H. K. Wu et al., 2013). AR aids students in grasping complex phenomena by offering interactive visual experiences that blend virtual and real-world information (Billinghurst & Dünser, 2012), keeping students’ attention and interest high, and facilitating a deeper understanding of the subjects covered. Creators can overlay virtual images onto real objects using AR, allowing users to interact physically with digital content. This capability enhances understanding of spatial and temporal relationships between real and virtual objects. For instance, while students can learn about a planet’s position relative to the sun through text and 2D images, visualizing a 3D solar system provides a clearer understanding of that position (López-Belmonte et al., 2023). Animated representations of dynamic processes, combined with direct tactile interaction, enable a natural engagement with digital content, leading to a deeper comprehension of spatial and temporal concepts (Hashim et al., 2024).

AR technology also excels at contextualizing content (Bacca et al., 2014; Scavarelli et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). It connects learning materials to the real world, helping learners understand the context of the information they learn. AR to create context-aware or location-based educational materials is emerging as an innovative educational strategy that leverages geolocation capabilities to deliver relevant, situated educational content. One of the main benefits of this approach is situated learning. Context-aware AR allows students to learn in real-world contexts, enhancing their understanding of concepts through direct interaction with their surroundings (Dunleavy et al., 2009). Students can receive information and resources tailored to their geographic location and specific context, fostering more focused and relevant learning (Bacca et al., 2014) and thus enhancing experiential learning and long-term memory (Billinghurst & Dünser, 2012). In addition, the ability to receive information in real time and to be located in the students’ physical context. For example, AR applications in museums allow individuals to view additional information about works of art or historical artifacts directly on their mobile devices, enhancing the on-site educational experience (C. A. Chen & Lai, 2021). Another example is the use of AR for natural science learning, where students can explore natural environments by receiving contextual information about plants, animals, and natural phenomena (Cascales et al., 2013; Lo et al., 2021).

Finally, AR promotes new forms of collaborative learning, both online and offline (Fan et al., 2020). Learning becomes a social activity as multiple users can interact with 3D objects and share their perspectives from various viewpoints, creating innovative learning experiences. The growing use of smartphones has spurred interest in mobile AR applications (Ariano et al., 2023). Modern smartphones and tablets, equipped with sensors such as cameras, GPS, compasses, accelerometers, large touchscreens, fast CPUs, and advanced graphics capabilities, are ideal for AR experiences.

7.2. Limits and Barriers to the Use of AR in Education

Despite its many advantages, implementing AR in education also presents several challenges and limitations. First, many studies on AR in education face methodological challenges (Al-Ansi et al., 2023). A common issue is the lack of detailed sample descriptions, including key characteristics such as age, gender, field of study, and recruitment methods. This omission limits the generalizability of findings, making it difficult to determine whether results apply broadly or are specific to student groups. Additionally, the absence of standardized assessment tools complicates the evaluation of AR’s impact on learning. Many studies rely on ad hoc scales that may lack reliability and validity, leading to fragmented findings that hinder a comprehensive understanding of AR’s educational effectiveness.

Secondly, the analysis of scientific literature highlights the lack of a standardized framework for evaluating AR applications in education (Al-Ansi et al., 2023). This problem is attributable to the variety of goals and contexts in which AR is applied. For example, the effectiveness of an AR application for learning technical skills in the medical field requires different metrics than an application designed to improve language learning in children. The use of ad hoc evaluation criteria and tools, which are often not validated, limits the comparability of results and the ability to conduct reliable replications or meta-analyses. This hinders the creation of evidence-based guidelines for the effective implementation of AR in education.

Thirdly, a significant limitation in several studies using AR for education is the lack of explication of the underlying learning theory (Garzón et al., 2020, 2021; Huang et al., 2019). Many studies do not specify the conceptual framework underlying their AR applications, and this lack of theory makes it difficult to interpret research findings in a broader context and limits understanding of the mechanisms through which AR might enhance learning. Without a sound theoretical framework, it’s challenging to establish the scientific basis for AR’s effectiveness and justify methodological choices. In addition, the lack of a reference theory makes it difficult to compare results across studies, as each project may be based on different unstated assumptions. This also prevents the development of a cumulative, coherent knowledge base to guide further research and development. Ultimately, the lack of theoretical clarity hinders the development of practical guidelines for integrating AR into education and limits scientific progress.

Fourth, despite its potential, AR can also cause distractions if not used properly. At times, students can become overwhelmed by overlapping information and visual interactions (Al-Ansi et al., 2023).

Fifth, another main obstacle is technical problems, such as a lack of a stable, accurate Internet connection and reliance on mobile device location sensors (Manisha & Gargrish, 2023). These problems can limit the effectiveness of AR in educational settings (Fan et al., 2020; H. K. Wu et al., 2013). In addition, the effectiveness of AR depends on teachers’ technological competence. Lack of proper training can limit the effective use of AR in the classroom (Nikou et al., 2024). Professional development is crucial to ensure teachers integrate AR effectively into their lessons.

Sixth, implementing AR technologies can be expensive, and not all schools have the resources to adopt these tools (Al-Ansi et al., 2023; Garzón et al., 2021). As noted by many authors, the costs associated with purchasing AR hardware and software can be a significant barrier for many educational institutions (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2017; Nguyen & Dang, 2017; H. K. Wu et al., 2013). Furthermore, ensuring that all students have access to the necessary technology and that the content is accessible is essential to avoid disparities in learning (Al-Ansi et al., 2023). Not all students may have access to mobile devices or reliable Internet connections, which can limit the effectiveness of context-aware learning materials (Bacca et al., 2014; Fan et al., 2020; Radu, 2014; H. K. Wu et al., 2013).