1. Introduction

There is a consensus among researchers that France has historically influenced the Brazilian educational model. This influence began when bourgeoisie members sent their children to study in France during the colonial period (between 1530 and 1822) and later intensified with the establishment of universities and schools in Brazil. Notable examples include Pedro II School in Rio de Janeiro, where educational materials and content were imported (in 1857), and the founding of the University of São Paulo, which employed French professors from 1934 onwards (

Lucchesi, 2011).

Currently, undergraduate engineering programs in France span ten semesters. The first four semesters may be completed at an engineering school or in preparatory courses for the Grandes Écoles (offered at Lycées or universities).

To gain admission to a French engineering school or preparatory course, students apply based on their high school performance. If admitted to an engineering school, students follow a ten-semester curriculum. Alternatively, those who choose preparatory courses receive a solid foundation, particularly in mathematics (480 h) and physics and mechanics (420 h), over the course of four semesters. Afterwards, they can undertake specialized training at 1 of the 154 Grandes Écoles over the next three years.

In Brazil, admission to engineering programs may occur through the national high school examination or a selection process conducted by the institution itself.

Brazilian engineering programs typically follow a structure similar to that of French universities, with a foundational cycle spanning four semesters that focus on mathematics, physics, and introductory engineering courses, followed by three years of specialized training.

As with admission processes, the sequence of Differential and Integral Calculus (DIC) courses in Brazilian engineering programs varies, particularly in the number of courses and the credit hours assigned within the curriculum.

Given this context, this article aims to understand the practices and perceptions surrounding the teaching and learning of Differential and Integral Calculus 1 (DIC1) based on the current French model (as implemented at Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1—LYON 1) and the Brazilian model (as observed at the Federal University of Technology—Paraná—UTFPR). Through this investigation, we analyze the perspectives of instructors and students regarding the methodological approaches applied to teaching DIC1 in engineering programs, addressing the research question—What are the current teaching practices and perceptions related to the teaching and learning of Differential and Integral Calculus I (CDI1) within the contemporary French model based on the context of Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1 (LYON 1), and within the Brazilian model, based on the context of the Federal University of Technology—Paraná (UTFPR)? This study seeks to advance a comparative understanding of these two educational systems.

Lucchesi (

2011) examines the historical influence of the French model on the development of the university system in Brazil; however, a contemporary comparative analysis of calculus courses for engineering students is not found in the literature and may offer meaningful insights for both countries. Such a comparison has the potential to inform and enhance teaching and learning processes by highlighting both convergences and divergences, as well as opportunities for pedagogical improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

The first step in this study involved a literature review to define the aspects that should be observed during the classes and the questions that should be included in the questionnaires. This review aimed to better understand the use of active methodologies in mathematics education within engineering programs and how such approaches impact the teaching and learning process. Based on this review, the observation protocol and questionnaires were adapted from the instrument and study developed by

Ellis et al. (

2014).

A total of 21 teaching activities were selected to compose the classroom observation form. A questionnaire was also developed for teachers and students after the observation period. In the questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate how frequently each of the 21 activities was employed during classes and to select the five they considered most relevant for learning.

The 21 activities included in both the observation form and the questionnaires are listed in

Table 1.

Most of these activities are characteristic of active learning and enhance the development of higher-order thinking, which is essential for fostering critical and analytical skills in students. Active learning encompasses diverse interpretations and implementations, ranging from hands-on laboratory approaches that emphasize personal, epistemological, and social involvement to strategies leveraging standardized assessments for formative purposes, thus shifting assessment from a summative score-based view to a dynamic process that informs teaching and motivates student engagement (

Spagnolo et al., 2021;

Ferretti et al., 2024).

Teaching practices must be connected to cognitive and semiotic dimensions, recognizing that students interact with representations rather than abstract mathematical objects; this requires managing treatments and conversions across semiotic registers, as outlined by Duval, to avoid cognitive gaps and ensure conceptual understanding. Finally, framing higher-order thinking demands moving beyond implicit or generic notions by explicitly addressing transversal competencies such as the ability to interpret, transform, and integrate multiple representations, which are essential for constructing mathematical knowledge and should be treated as explicit learning goals within instructional design (

Spagnolo et al., 2021;

Ferretti et al., 2024).

Question 1 addressed the frequency with which the 21 activities were used in class, with responses measured using a Likert scale: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), often (4), and always (5). Question 2 asked participants to identify the five most important activities for learning. The most crucial activity scored 5 for this question, while the least important of the five received a 1.

Responses from both teachers and students were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including the calculation of absolute (

n) and relative (%) frequencies (

Kaur et al., 2018). For Question 1 (teaching frequency), the results were presented using diverging bar charts, as recommended by

Robbins and Heiberger (

2011).

To evaluate the association between activity responses, country, and respondent status (teacher or student), non-parametric Mann–Whitney tests were used (for comparisons between two independent groups), which allow for comparison across numerical or ordinal categorical variables.

Given the impact of sample size on p-values (

Sullivan & Feinn, 2012), the effect size (r) was also calculated (

Fritz et al., 2012), with values interpreted as follows: small (r > 0.1), medium (r > 0.3), and large (r > 0.5) (

Cohen, 1988). All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.3.3 (

R Core Team, 2023), with a significance level (α) of 5%.

Bar charts with the results of these questions can be found starting in

Section 4.3.

For the comparison of the data collected through observations with the responses of students and teachers to the questionnaires, the activities most frequently observed were compared with those most frequently employed according to teachers and students.

Data collection occurred during France’s 2022–2023 academic year and the second semester of 2023 in Brazil. Class observations and printed questionnaires were administered to both teachers and students. The participating teachers included eight from France and four from Brazil. The study involved 115 students from LYON 1 and 69 from UTFPR. According to

Reis (

2011), classroom observation enhances the quality of teaching and learning by enabling access to instructional strategies, applied activities, and teacher–student interactions.

3. Differential and Integral Calculus

Differential and Integral Calculus (DIC) content is presented in different configurations in France and Brazil. At LYON 1 in France, the mathematics course analyzed was Algèbre et Analyse, which, in the first semester, covers algebraic calculations, basic concepts of logic, complex numbers, arithmetic, polynomials, functions and applications, sequences and series of real numbers, limits and continuity of functions, and differentiation. The second semester includes matrices, vector spaces, linear applications, rational functions, integration, and differential equations. In Brazil, these topics are primarily distributed across the courses Differential and Integral Calculus 1 (DIC1) and Analytical Geometry and Linear Algebra.

In Brazil, the sequence of DIC courses may vary in number and duration, often offered across two or three semesters. The UTFPR Pato Branco campus, where the research took place, has two versions of DIC (Differential and Integral Calculus), depending on the engineering course. In Computer Engineering, Electrical Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering, the DIC sequence consists of 2 units: Calculus in One Real Variable (90 h) and Calculus in Several Real Variables (60 h). The exception is the Civil Engineering course, which offers the DIC sequence in 3 units of 60 h each: Pre-Calculus and Differential and Integral Calculus 1 (with a syllabus equivalent to Calculus in One Real Variable) and Differential and Integral Calculus 2. The difference lies mainly in discussing the content of Functions in the Pre-Calculus course.

For this study, data collection and classroom observations in Brazil were conducted in Calculus in One Real Variable and Differential and Integral Calculus 1.

3.1. France: Lyon 1 and the Course Algèbre et Analyse

LYON 1 is a university that offers six different engineering programs through its école d’ingénieurs Polytech Lyon and a preparatory course for the Grandes Écoles, and for this reason, it was included in the study.

Algèbre et Analyse is a first-year preparatory course with a total workload of 240 h, distributed over two semesters. A lead instructor is responsible for coordinating the course across semesters and among the instructors who teach the tutorial groups (Travaux Dirigés, or TDs).

During the first year, students dedicate 10.5 h per week to mathematics: 4.5 h are spent in large lecture halls with approximately 130 students, while the remaining 6 h are dedicated to problem-solving sessions in TD groups, which are divided into five smaller groups. The lectures are delivered by different instructors each semester, and the TD groups are also assigned different instructors.

Lecture sessions in the auditorium are expository, focusing on presenting theorems and proofs. In contrast, TD sessions emphasize problem-solving, with the teaching style varying by instructor. The auditorium, which has a capacity of 200 students, is equipped with multimedia projectors, two screens, and a chalkboard.

TD classrooms range from small rooms with chalkboards or whiteboards and a capacity of 30 students to larger rooms that accommodate 50 students and are equipped with whiteboards and multimedia projectors.

On the department’s homepage, students can access the syllabus, which includes a class-by-class schedule of topics covered, exercises assigned in each TD session, exercise sets with solutions, evaluation criteria, links to books and supplementary materials, past exams with answer keys, and announcements. If an instructor needs to “accelerate” the content delivery, this is also reflected in the TD sessions.

Students take between 4 and 8 written exams, which account for 30% of their final grade. In groups of three, they also complete oral assessments on definitions and theorems. These oral assessments last one hour and occur four times per semester, comprising 40% of the final grade. The final exam is a standardized written test administered to all students enrolled in the same course, accounting for the remaining 30% of the final grade.

3.2. Brazil: The Course Differential and Integral Calculus 1

The Federal University of Technology—Paraná (UTFPR) is a benchmark in engineering education in Brazil. With over a century of history, it began its academic activities in 1909. It comprises 13 campuses and offers 57 engineering programs across 18 different specializations. The research took place at the Pato Branco campus, which offers 5 Engineering courses. The campus was chosen based on the number of courses and the number of students.

The course Calculus in One Real Variable syllabus covers functions, limits, derivatives, and integrals of a real variable. In contrast, Differential and Integral Calculus 1 (DIC1) specifically addresses limits, derivatives, and integrals of a real variable. Students in Computer Engineering, Electrical Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering spend 5 h per week dedicated to Calculus in the first semester, and Civil Engineering students dedicate 3 h and 20 min. In both cases, an additional 5 h are dedicated to Analytic Geometry and Linear Algebra, totaling 8 h and 20 min or 10 h per week dedicated to mathematics, depending on the course.

Instructors utilize the Moodle platform to share the course plan, supplementary materials, and exercise lists, as well as to maintain communication channels with students.

Classes follow a lecture-based and dialogical format, both for presenting content and for solving exercises, although the class dynamics may vary depending on the instructor.

The course schedule is flexible and typically adapted by each instructor to fit the characteristics and needs of each cohort. Students take three written exams, and instructors may include supplementary assessment activities and/or make-up evaluations.

The classrooms have a capacity for 60 students, a large whiteboard, are equipped with a multimedia projector, and are air-conditioned. Class sizes ranged from 23 to 29 students.

4. Teaching Activities in DIC and Learning Conceptions

This section presents the classroom observations and the responses of teachers and students to the questionnaires. By identifying the teaching methodologies adopted by instructors based on classroom observations, we can compare them with the responses provided by both teachers and students. Finally, we present how teachers believe students learn best and whether these beliefs align with their actual teaching practices and students’ expectations.

A more in-depth discussion of the data collected can be found in the following section, where we compare the activities observed with the most dedicated time with the activities most frequently mentioned by teachers and students.

4.1. Observations of TD Groups—France

The 130 students enrolled in Algèbre et Analyse during the 2022–2023 academic year were divided into five TD groups. These groups met simultaneously, twice a week for 3 h sessions each, including a 15 min break. Group TD1 consisted of the 30 students with the highest admission scores, while the remaining groups each had 25 students. Groups TD4 and TD5 were co-taught by two instructors who alternated between sessions throughout the first and second semesters, and these instructors were not included in the observations. The eight TD instructors observed are A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H.

The instructors and groups observed, and the number of observations is summarized in

Table 2.

The number of observed sessions varied depending on the instructors’ availability to host the first author. Social movements and strike days during the academic year also disrupted the schedule, limiting access to certain classes and limiting the number of sessions that could be observed.

The average time (in minutes) dedicated to each activity observed in class is summarized in

Table 3. Each meeting is equivalent to 180 min.

The TD sessions were primarily intended for problem-solving, with instructors typically demonstrating solutions on the board and occasionally inviting students to present their solutions. Instructors would ask if anyone was interested in going to the board. Some students volunteered repeatedly, while others declined, saying they were unprepared.

Professors C and G were the youngest among the group, with 8 and 4 years of teaching experience, respectively. Their relationships with students differed from those of more experienced instructors. Professor C spent two-thirds of the session solving problems on the board and devoted 50% more time than the average to answering students’ questions. Students frequently approached him during breaks or after class to discuss questions, casually, and even offered him coffee as a reward for solving a specific problem.

Professor G, in turn, devoted nearly three times the average amount of time to students solving exercises individually. He continuously walked around the classroom offering help and answering questions. However, it seemed that the small age gap between him and the students allowed for greater freedom of expression—but also led to off-topic conversations, suggesting a lack of respect for the instructor.

Professor F, with ten years of experience, did not invite students to the board. He spent almost two-thirds of the session solving problems but explained each step thoroughly, including which theorems justified the operations. He also exceeded the average time spent responding to questions and supporting students working individually. Notably, he was the only instructor who took attendance at every session.

Other instructors had between 18 and 32 years of experience. After a conversation with his class, Professor B concluded that most students had not completed the assigned exercises before the TD session, as recommended. He was strict about cellphone use and off-topic conversations. He spent one-sixth of the class time lecturing—an approach unsuited for TD settings. He did not invite students to the board but spent the second-highest average amount of time on whole-class discussions and asked students to explain their reasoning.

Professor A devoted nearly one-third of the class time to solving problems on the board—more than three times the average—but did not ask students to explain their reasoning during or after the activity. He emphasized the importance of memorizing formulas and solving problems without reference materials. He also delivered one of the highest average amounts of lecture time but showed concern for a student who joined late in the semester, asking if she was keeping up and encouraging her to ask questions.

No full-class discussions were observed in the sessions taught by Professors A, D, and E. However, Professor D spent 50% more time responding to student questions than average, while P. At the same time, E devoted the most time to having students explain their reasoning—almost five times the average amount, amounting to one-sixth of the total class time.

Professor H demonstrated a more balanced instructional approach by spending less time solving problems on a board and more time in full-class discussions. In the questionnaire, he commented that this teaching style is only possible due to the engagement and commitment of his students. He added that such a method would not be feasible in other classes.

4.2. Observations from the DIC1 Course—Brazil

During the second semester of 2023, four classes were observed: three of them were Calculus in One Real Variable courses offered to students who had previously failed the subject, and one was a Differential and Integral Calculus 1 (DIC1) class for regular students in the Civil Engineering program.

Four instructors were responsible for teaching these courses. Classes were held in rooms with a capacity of 60 students, equipped with whiteboards, multimedia projectors, and air conditioning. The number of students per class ranged from 23 to 29.

Instructors I, J, and K taught their classes simultaneously, with three weekly sessions of 1 h and 40 min each. Instructor L taught in two weekly sessions of the same duration.

Table 4 shows the instructors observed, the course they were teaching, and the number of sessions observed.

The number of sessions observed varied depending on the instructor’s availability. In addition to scheduling conflicts, simultaneous teaching times, and other academic responsibilities limited the number of sessions that could be observed.

Table 5 summarizes the main characteristics observed during the classes, along with the average time spent on each one in minutes, noting that a meeting totals 100 min.

Instructors J and L were the youngest in the group, with 3 and 8 years of teaching experience, respectively. Although Instructor J spent approximately 40% of the class time lecturing, his interaction with students was dynamic, consistently prompting questions and discussions. Instructors I and K had 16 and 18 years of teaching experience. All instructors began their classes by reviewing the content of the previous session.

I was the only instructor who used GeoGebra and encouraged students to do the same. He spent less than half of the class time at the board—whether lecturing or solving problems—and actively encouraged students to work on exercises and other tasks. Notably, he allocated about one-third of class time (34.33 min) to individual problem solving by students, nearly double the average.

In all observed classes, when students were asked to solve problems individually, some chose to collaborate with their peers—without being discouraged. Instructor K was the only one to assign group exercises. Combining students’ time working individually and in groups, he devoted 28.8 min to student-centered problem solving.

It is also worth noting that Instructor K was the only one who provided supplementary materials via Moodle and asked students to complete exercises before class.

Finally, Instructor L spent the most time solving problems on the board—35.5 min, just over one-third of the class session—and dedicated the most time to whole-class discussions.

4.3. Teaching According to Teachers

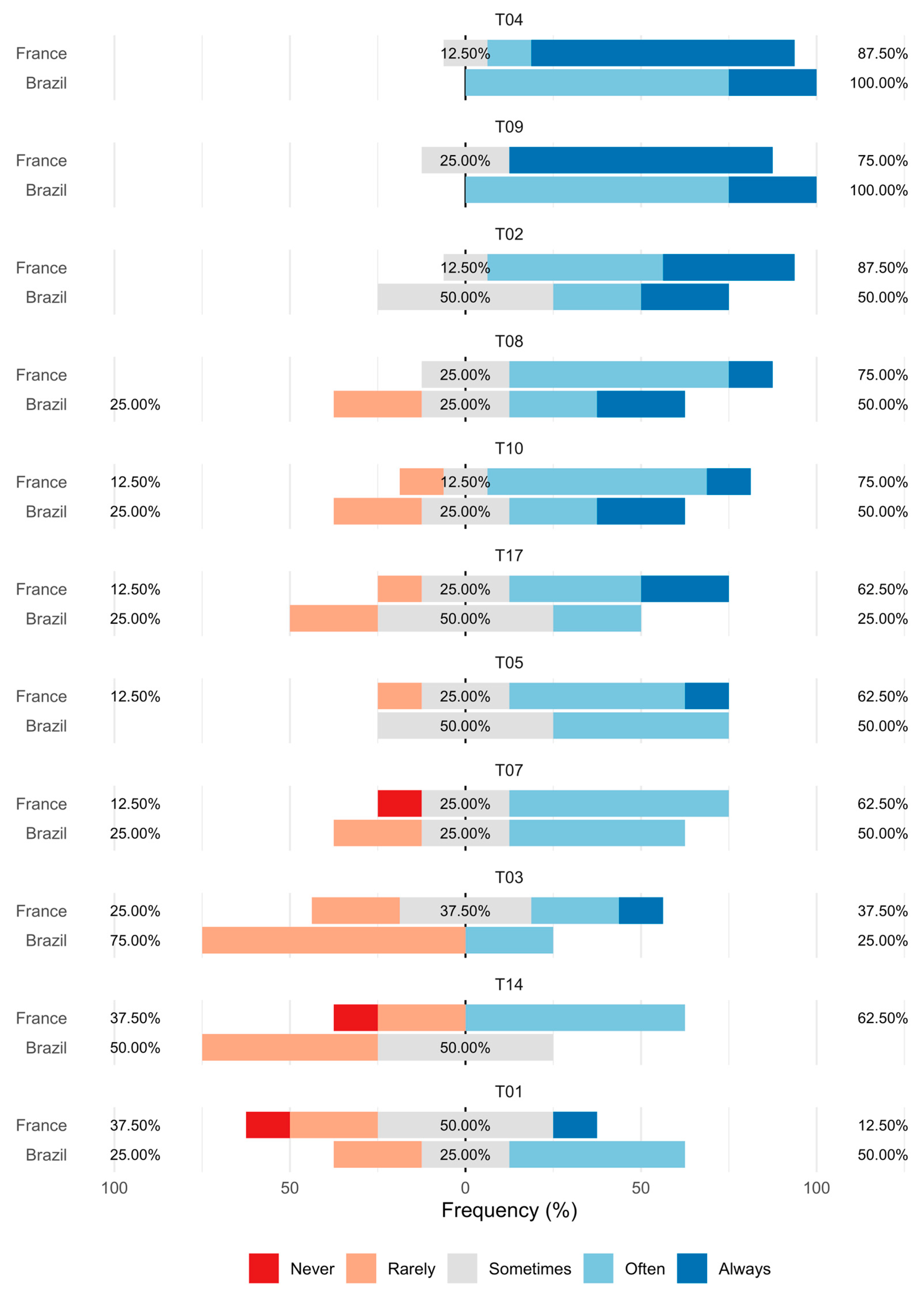

Figure 1 summarizes the responses of French and Brazilian instructors regarding the frequency with which they apply the listed teaching activities, as perceived by them.

Table 6 presents the teaching methodologies corresponding to the 21 observed teaching activities, as listed in

Table 1.

Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found for the following teaching activities:

T16—Recommends supplementary materials;

T15—Provides pre-class materials;

T19—Uses mathematical software;

T21—Uses platforms with immediate feedback.

With large effect sizes (r > 0.5), indicating that the difference remains meaningful despite the small sample size. In all these cases, Brazilian instructors reported using such activities more frequently—even if only “rarely” or “sometimes.” This suggests that Brazilian instructors tend to provide more support to students through supplementary and pre-class materials and technological tools to enhance content understanding. Brazilian instructors’ use of mathematical software was reported at a frequency between “sometimes” and “often.”

Among the activities most frequently used by French instructors—reported as “always”—are those aligned with the structure and organization of TD sessions, such as the following:

Followed by:

T02—Solves exercises on the board;

T08—Facilitates whole-class discussions;

T10—Asks students to explain their reasoning;

T17—Assigns pre-class exercises;

T05—Asks students to solve exercises individually.

with frequencies ranging between “often” and “always.”

Additionally, the activities:

T07—Provide individual support to students;

T03—Ask students to solve exercises on the board;

T14—Ask students to explain their reasoning during assessments.

and have cumulative frequencies above 50%, falling between “sometimes” and “always.”

The high frequency of these activities reflects the nature of the course, which emphasizes problem-solving and includes oral assessments, justifying the frequent use of exercises on the board by both instructors and students, as well as the emphasis on reasoning during assessments. However, these remain individual experiences: students ask questions, the teacher answers, and students work independently with occasional individual support.

For Brazilian instructors, the most frequently reported activities—with cumulative frequencies of 100% between “often” and “always”—were as follows:

Followed by:

T05—Asks students to solve exercises individually;

T07—Provides individual support;

T01—Delivers lectures;

T19—Uses mathematical software;

T17—Assigns pre-class exercises;

T02—Solves exercises on the board;

T08—Facilitates whole-class discussions;

T10—Asks students to explain their reasoning.

With cumulative frequencies between 50% and 75% (rated between “sometimes” and “often”).

These results reflect the specific characteristics of DIC1 classes. They are aligned with the classroom observations—such as “A01—Teacher lectures” and “A19—Teacher uses mathematical software”, the latter showing a statistically significant difference.

Nevertheless, the most common classroom activities in DIC1 are largely solitary: students work alone, are individually supported, attend lectures, ask questions, and receive answers.

In France and Brazil, students remain passive: they receive instructions, fulfill assignments, and occasionally provide responses or explanations. Some activities that teachers reported frequently were seldom observed during class, including the following:

T09—Asks students if they have questions;

T08—Facilitates whole-class discussions;

T10—Asks students to explain their reasoning;

T17—Assigns pre-class exercises;

T07—Provides individual support.

This gap between reported and observed practice may be related to the minimal time these activities require. For example, asking whether students have questions (A09) or assigning exercises in advance (A17) takes little time and may not have been captured extensively during observations.

4.3.1. The Teaching in France According to Teachers and Students

Figure 2 summarizes the responses of teachers and their students in France.

No statistically significant differences were found, and it can be stated that students perceive teaching as their teachers do.

4.3.2. The Teaching in Brazil According to Teachers and Students

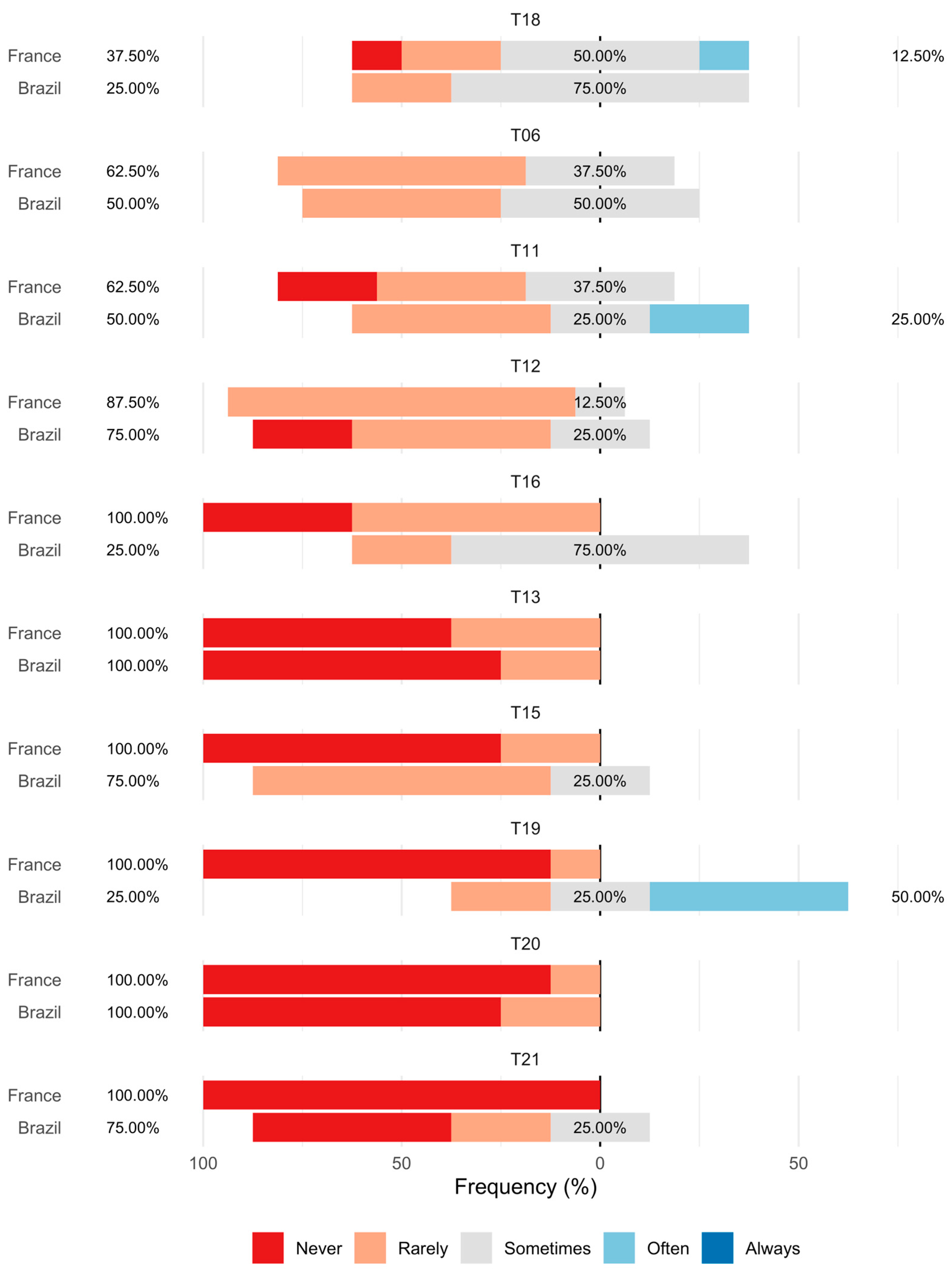

Similarly, we will compare the responses of Brazilian students with those of their teachers.

Figure 3 below summarizes the responses of Brazilian teachers and their students.

Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found for the teaching activities “T02—Solves exercises on the board” and “T09—Asks if students have questions,” with effect sizes (r) being small and medium, respectively. In both cases, students rated these activities as more frequent than their teachers did, which leads us to conclude that students reinforce the notion that, indeed, the teacher asks if students have doubts and dedicates time to solving exercises on the board, a finding corroborated by classroom observations.

4.4. The Learning Conception According to Teachers in France and Brazil

We now proceed to discuss how learning is perceived by teachers.

Figure 4 summarizes the responses from French and Brazilian teachers, who ranked the activities they consider most important and believe can contribute to improving learning. This question was not answered by Teacher D. The learning activities “L01—Observes the teacher explaining content as a lecture,” “L06—Solves exercises involving real-world problems,” “L13—Gives a presentation to the entire class,” “L15—Receives pre-class material, such as a book excerpt or video,” “L19—Uses some mathematical software,” “L20—Plays a game proposed by the teacher in the classroom,” and “L21—Uses a platform with immediate feedback” were not selected by the teachers and, therefore, were excluded from the analysis.

Table 7 presents the teaching methodologies in correspondence to the 21 observed teaching activities, according to

Table 1.

No statistically significant differences were found between the responses of French and Brazilian teachers, although the list of the most important activities differs between the two countries.

The activities in which students “L17—Solve exercises before class,” “L02—Watch the teacher solve exercises on the board,” and students “L05—Solve exercises individually” are characteristic of the tutorial session (TD), and these activities occupy the top positions indicated by French teachers as those that can contribute to improving learning.

Among French teachers, “L02—Watch the teacher solve exercises on the board” and students “L05—Solve exercises individually” occupy the second and fourth positions in order of importance, respectively. In addition to being considered important for learning, these activities were reported by teachers as frequently performed, with a cumulative frequency above 75% between “sometimes (3)” and “always (5)”. They were also frequently observed during classes and collectively accounted for almost two-thirds of class time on average.

Meanwhile, the students’ activities “L17—Solve exercises before class” and “L09—Ask questions about their doubts,” which occupy the first and third positions in order of importance, respectively, may be related. By solving exercises in advance, students may bring their questions to class.

It remains contradictory that French teachers indicated the student activity “L11—Work with peers to solve exercises” as the fifth most important for learning, yet stated that this activity is performed “rarely” or “sometimes,” with a cumulative frequency of 75%, and it was not observed in the classes monitored.

The list of the five most important activities for Brazilian teachers, capable of contributing to learning, differs considerably from that of French teachers.

Only the activities “L02—Watch the teacher solve exercises on the board” and “L09—Ask questions about their doubts” are among the top five for both French and Brazilian teachers. Additionally, the Brazilian list includes the student activity “L12—Explain an exercise to a peer,” “Solve exercises on the board,” and “L10—Explain their reasoning during class.”

Among the most important activities for both French and Brazilian teachers, only the activity “L02—Watch the teacher solve exercises on the board” is teacher-focused. The remaining activities involve greater student engagement in their learning process, as they require students to organize their thoughts and processes in order to verbalize them to peers or ask questions. These activities position the student at the center of the learning process, as an active agent in their own learning.

However, Brazilian teachers point to “L12—Explain an exercise to a peer” as the most important activity, yet this activity was not observed during the sessions. The activity “L02—Watch the teacher solve exercises on the board” is frequently employed, with a cumulative frequency of 100% between “sometimes (3)” and “always (4),” according to Graph 1, and this activity occupies approximately one-quarter of class time on average.

Figure 4 further shows that the conceptions of French and Brazilian teachers differ regarding the activities most important and capable of contributing to student learning. For French teachers, the most important activities for learning are those in which the student remains passive or engaged in individual tasks, whereas for Brazilian teachers, the most important activities involve students actively engaged in the learning process.

4.4.1. The Learning Conception in France According to Teachers and Students

Because the students responded to the same questionnaire, it is possible to compare their responses with those of their teachers.

Figure 5 summarizes the responses of French teachers and their students.

French teachers and students attributed statistically different importance to the activity “L17—Solve exercises before class,” and the effect size (r) is small. The importance attributed by teachers was higher than that attributed by students; that is, the teacher emphasizes the need for students to solve exercises before class, which is consistent with the characteristics of DT and the observations made. However, students do not perceive the importance of this activity to the learning process as their teachers do.

For French teachers, the most important activities for learning reflect the characteristics of DT, while for students, the most important activities for learning are “L02—Watch the teacher solve exercises on the board,” “L04—Watch the teacher answer their questions on the board,” “L05—Work individually on problems or exercises,” “L09—Ask questions about their doubts,” and “L11—Work with their peers to solve exercises.”

The activities indicated by students point to an individualized activity, where students ask questions and receive answers from the teacher. You do some work individually, and when you point to group work, in the fifth position, you may be interested in the possibility of receiving help and answers from your colleagues.

4.4.2. The Learning Conception in Brazil According to Teachers and Students

Similarly, we will compare the responses of Brazilian students with those of their teachers.

Figure 6 summarizes the responses of Brazilian teachers and their students.

Brazilian students and teachers assigned statistically different importance (p < 0.05) to “L10—Explains your reasoning during class” and “L03—Solve exercises on the board,” with an effect size (r). Teachers assigned higher importance to these two questions than students. The activity “L13—Gives a presentation to the entire class” was not selected by any of the teachers or students and was therefore the analysis.

Brazilian teachers indicated activities in which students are actively involved in learning, such as the activities “L12—Explains an exercise to a classmate,” “L09—Asks questions about your doubts,” “L10—Explains your reasoning during class,” and “L03—Solve exercises on the board,” the latter two showing statistically significant differences. Brazilian students also indicate passive learning, listing the activities “L02—Watch the teacher solve exercises on the board,” “L04—Watch the teacher answer their questions on the board,” “L01—Watch the teacher explain the content like a lecture,” “L09—Ask questions about their doubts,” and “L11—Work with their peers to solve exercises.” The only activity that indicates some student involvement, such as group work, suggests the possibility of receiving contributions from peers, an activity that is more frequently observed in Brazil and cannot be observed in the classes.

4.5. The Learning Conception According to Students in France and Brazil

We can also compare the responses of French and Brazilian students to the second question, to observe their opinions on the most critical activities for learning, and to analyze the differences between the countries.

Figure 7 summarizes the students’ responses.

French and Brazilian students assigned statistically different importance (p < 0.05) to the activities “L01—Watch the teacher explain the content as a lecture,” “L03—Solve the exercises on the board,” “L05—Work individually on problems or exercises,” “L16—Receive supplementary material (websites, videos, books, and/or texts),” and “L19—Use some mathematical software.” French students assigned greater importance to the activities “L03—Solve the exercises on the board” and “L05—Work individually on problems or exercises,” both of which had a small effect size (r). The other activities most important to Brazilian students were “L01—Watches the teacher explain the content as a lecture” and “L16—Receives supplementary material (websites, videos, books, and/or texts)” with a small effect size, and “L19—Uses some mathematical software” with a medium effect size.

Among the five most essential activities listed by French and Brazilian students, the only activity that differs in the two lists, in third place, is “L05—Works individually on problems or exercises” for the French, and “L01—Watches the teacher explain the content as a lecture” for the Brazilians.

Both groups emphasize the importance of not remaining uncertain, as they indicate “L09—Asks questions about their doubts” in fourth place. However, the activities indicated by the students suggest individualized learning, where they ask questions and receive answers from the teacher. In France, students work individually, while in Brazil, they remain passive in class. When they indicate group work, in fifth place, they seek support from the teachers. colleagues.

Activities such as “L08—Participate in a discussion with the whole class,” “L14—Explain your reasoning during assessment,” “L10—Explain your reasoning during class,” and “L03—Solve the exercises on the board,” which require some engagement from students and could contribute to active learning, are at the bottom of both lists.

5. Discussion

Based on the data collected, in France, the teaching activities observed consist, on average, of 54.7% of class time with the teacher lecturing and solving exercises on the board, while 36.3% of class time is dedicated to students solving exercises individually or at the board, with the teacher responding to questions.

Only 5.25% of the average class time is devoted to whole-class discussions, students explaining their reasoning, or making presentations to the class—activities that can enhance learning by requiring students’ active engagement.

In Brazil, teachers dedicate on average 51% of class time to lecturing and solving exercises on the board, followed by 21.5% of class time during which students solve exercises individually or at the board, with the teacher addressing questions. Meanwhile, 6.1% of the average class time is allocated to whole-class discussions and group work.

When comparing the teachers’ responses regarding how frequently they employ these activities with the data collected from classroom observations, it appears that the most frequently employed activities, as shown in Graph 1, were indeed observed, albeit occupying limited time.

Nevertheless, the most frequently observed activities and the time allocated to them in Calculus I (DIC) instruction reflect characteristics of traditional teaching methods.

Statistically significant differences were found between French and Brazilian teachers in terms of specific teaching practices such as “L16—Recommends supplementary materials,” “T15—Provides pre-class materials,” “T19—Uses mathematical software,” and “T21—Uses platforms with immediate feedback.” Brazilian teachers reported more frequent use of these activities, suggesting they may be more open to active learning methodologies, as they already incorporate activities aligned with such strategies.

Students, when asked about how frequently their teachers implement these activities, generally agreed with their teachers’ perceptions. However, in Brazil, statistically significant differences were found for the activities “T02—Solves exercises on the board” and “T09—Asks if students have questions,” where students reported higher frequencies than teachers did. This discrepancy may reflect either the teachers’ modesty or the students’ overestimation of these activities.

The list of the most important activities contributing to learning, as perceived by French and Brazilian teachers, differs between the two countries, reflecting distinct educational realities in each country. Despite these differences, both groups report using similar teaching strategies when considering the most frequently employed activities.

Among the activities listed by French teachers, “L17—Solves exercises before class” and “L09—Asks questions about their doubts” cannot only be used together but also support the development of higher-order thinking skills such as applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and creating. Similarly, Brazilian teachers identified activities such as “L12—Explains an exercise to a peer,” “L03—Solves exercises on the board,” and “L10—Explains reasoning during class” as important for learning, also supporting the development of higher-order thinking and placing students at the center of the learning process.

When comparing French students’ responses about the most important learning activities to those of their teachers, a statistically significant difference was found for the activity “L17—Solves exercises before class.” This suggests that while teachers expect students to solve exercises in advance to bring their questions to class, students do not perceive this activity as one of the top five most important for learning.

French students generally listed individual and passive activities as the most important, with the exception of “L11—Works with peers to solve exercises,” indicating that they remain engaged in lower-order thinking tasks, mostly receiving instruction from the teacher and occasionally peer support.

Radzimski et al. (

2021) discussed group-based problem solving in Calculus courses and found that both top-quartile and bottom-quartile students benefited. The former gained opportunities to explain mathematical reasoning, while the latter profited from peer support during problem-solving.

Rohde Poole (

2022) applied mathematical modeling in a mathematics course, including group problem-solving, and the students showed themselves to be in favor of the activities.

This finding aligns with

Freeman et al.’s (

2014) definition of active learning and the characteristics outlined by

Bonwell and Eison (

1991), who advocate for student involvement in the learning process through classroom activities and/or discussions, and often involve group work.

In Brazil, teachers attributed statistically significant importance to the activities “L10—Explains reasoning during class” and “L03—Solves exercises on the board,” which do not appear among the students’ top five. These activities provide opportunities for developing higher-order thinking skills, according to Bloom’s Taxonomy. Activities include application, analysis, evaluation, and creation. (

Ferraz & Belhot, 2010).

Zandieh et al. (

2017) implemented a classroom setting with four walls entirely covered in whiteboards, where students worked in small groups—a variation of the “L03—Solves exercises on the board” activity. The authors noted that this approach helped students see mathematics as a human activity and themselves as active creators of knowledge, again promoting higher-order thinking.

When comparing the top five activities identified by students as most important for learning, they were mostly passive in nature, such as watching the teacher solve exercises and respond to questions on the board or working in groups. Brazilian students still value traditional classroom formats, whereas French students tend to emphasize individual work. All of these activities are primarily focused on lower-order thinking skills.

Interestingly, the activity “L14—Explains reasoning during assessment,” which characterizes the TD format, is not among the top five for either French students or teachers. Likewise, “L17—Solves exercises before class” is not perceived as important by French students, even though it could promote higher-order thinking.

In the French context, teachers appear to view learning as a process in which students solve exercises before the TD, bring their questions to class, watch the teacher solve problems on the board, and then work individually or with peers. Students, however, do not acknowledge the importance of solving exercises in advance and mainly see themselves as spectators watching the teacher solve problems and answer questions, occasionally working individually or with peers.

These were the most frequently employed teaching practices, according to both French teachers and students, and were observed during TD sessions—except for the “A11—Students work in groups” activity. The remaining activities mostly promote lower-order thinking. Overall, French teachers and students share similar views on the learning process.

In Brazil, teachers seem to perceive learning as involving students explaining exercises to peers, articulating their reasoning, asking questions, watching the teacher solve problems, and solving exercises themselves on the board. In contrast, students describe learning as largely a passive process: attending lectures, watching the teacher solve problems, asking questions, listening to responses, and occasionally working with peers.

Although Brazilian teachers emphasize activities that promote higher-order thinking—such as “L12—Explains an exercise to a peer,” “L10—Explains reasoning during class,” and “L03—Solves exercises on the board”—these activities were rarely observed during class. In fact, only one teacher asked a student to solve a problem on the board, and only for a brief period. Of the most frequently employed activities, only “L10—Explains reasoning during class” appeared among the top.

Furthermore, research by

Lugosi and Uribe (

2022) shows that the implementation of active learning strategies, such as classroom discussion, group work, whole-class presentations, and real-world problem-solving, was able to improve students’ academic performance, with a 10% lower failure rate compared to the control group.

The most frequently used activities in Brazilian DIC1 classes, according to both teachers and students, primarily target lower-order thinking skills, such as remembering and understanding, according to Bloom’s Taxonomy. Students’ perspectives on learning also reflect this focus. This suggests a potential discrepancy between Brazilian teachers’ beliefs about how students learn and their actual teaching practices.

According to

Sun and Zhang (

2024), apparent discrepancies between teachers’ beliefs and their teaching practices, especially positive beliefs about teaching, may have been expressed simply because they were expected. They warn that it is difficult to guarantee that such a belief will necessarily be implemented in practice, but it is more likely to be. The authors also emphasize the importance of promoting reflective practices in teacher training programs to align teachers’ beliefs with their teaching practices.

What many teachers may not realize is that, according to research by

Ellis et al. (

2014), students who persist in studying Calculus—or choose to take additional Calculus courses—often report that group work and activities requiring them to explain their thinking to peers were influential in that decision. These activities are not tied to a single methodology, but can be part of various pedagogical approaches.

Table 8 presents the main results obtained according to the objective in each of the comparisons performed.

We identified the need to bridge the gaps between teaching practices, theoretical frameworks, and student engagement in mathematics education.

Spagnolo et al. (

2021) highlight how formative assessment and active learning strategies can transform traditional approaches, particularly through laboratory-based activities and the integration of standardized assessments to foster reflective teaching and student autonomy. Activities A03, A06, A08, A10, A11, A12, and A13 listed in

Table 1, for example, pursue the same pedagogical purpose as outlined by

Spagnolo et al. (

2021).

Ferretti et al. (

2024) focus this discussion by addressing the cognitive and semiotic dimensions of learning, showing that managing multiple representations and conversions between registers is critical for conceptual understanding and higher-order thinking. Activity A19, involving the use of mathematical software such as GeoGebra, is indispensable for attaining the objectives outlined by

Ferretti et al. (

2024).

Together, these findings advocate for a systemic shift toward pedagogies that explicitly cultivate active participation, cognitive flexibility, and metacognitive skills, moving beyond rote procedures to empower students as co-constructors of mathematical knowledge.

6. Conclusions

The course model for Algebra and Analysis developed at Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1 is similar to the model presented by other authors, such as

Gruber et al. (

2021) and

Hancock et al. (

2021) in the United States, and

Radzimski et al. (

2021) in Canada. These models involve a large lecture class followed by smaller sessions dedicated to solving exercises. The difference, however, lies in the length of each session and the number of hours allocated to exercise resolution.

For instance, the DIC course model developed at UTFPR differs significantly from the French model. In Brazil, the same instructor leads all student activities, always working with small groups.

Throughout the observations, activities such as “A09—Teacher asks students if they have questions” and “A17—Teacher asks students to solve exercises before class,” which were frequently rated between “sometimes (3)” and “always (5)” by instructors, were indeed observed. However, they were not among the most frequently observed activities, likely because such tasks do not require a significant amount of classroom time.

In both France and Brazil, instructors spend on average more than 50% of the class time at the board. This means that for more than half of the class duration, students are watching the instructor lecture or solve problems while copying notes. Less than 10% of class time is devoted to activities where students are actively engaged and developing other skills, such as participating in whole-class discussions, explaining their reasoning, giving presentations, or working in groups.

There seems to be agreement between French and Brazilian instructors regarding the teaching methodology for the DIC course. The eight most frequently used teaching activities are the same in both groups, despite the classes having different characteristics. These activities are largely characterized by passive, individual student work, including “T02—Solves exercises on the board,” “T04—Answers questions on the board,” “T09—Asks if students have questions,” “T17—Asks students to solve exercises before class,” “T05—Asks students to solve exercises individually,” and “T07—Provides individual support.” Students largely agree with their instructors on the teaching approach used.

It is worth noting that the use of mathematical software was observed in only one Brazilian class (teacher P1), yet it ranked among the top ten reported teaching activities, with 75% of Brazilian instructors rating it as occurring “sometimes (3)” or “often (4).”

However, there is less agreement between French and Brazilian instructors regarding which activities are most important for student learning, as shown in Graph 4.

French instructors cited “L05—Solves exercises individually” and “L11—Works with peers to solve exercises” as among the most important learning activities. However, these seem to be opposing rather than complementary activities. The former does not encourage the exchange of experiences or the development of other skills as the latter does. These activities could complement each other if combined with tasks such as “T10—Asks a student to explain their reasoning” or “T13—Asks students to make a presentation to the class.” The other activities considered important by French instructors still reflect passive learning, where students receive information rather than construct knowledge.

Brazilian instructors, on the other hand, seem to believe that the most important activities for student learning—and those they report using—are not fully aligned. Activities like “L12—Explains an exercise to a peer” and “L03—Solves exercises on the board,” cited as the first and fifth most important for learning, do not appear among the top ten teaching practices, nor were they observed during classroom sessions. For Brazilian instructors, the most impactful learning activities are those in which students are actively involved.

Notably, the activities “L02—Watches the teacher solve exercises on the board” and “L09—Asks questions about their doubts,” mentioned by both French and Brazilian instructors among the top five most important for learning, reflect the necessity of problem-solving and the instructors’ concern that students leave class without lingering questions.

Students’ views on the most important learning activities suggest a preference for traditional instruction, where the teacher presents content and solves problems while students remain passive—listening and copying—both in France and Brazil.

In the French context, students do not seem to value solving exercises before class, likely because time is already allocated for individual work during TD sessions, as noted in teacher B’s class. Additionally, the time instructors spend at the board solving exercises, with students only copying, supports this view. This is reinforced by the importance instructors attribute to the activity “L17—Solves exercises before class,” which students rank significantly lower.

We observe that, generally, instructors in both countries report similar teaching practices, and students’ perceptions align with those of their teachers. French instructors seem to believe in passive learning, while Brazilian instructors prefer active student engagement. However, the actual teaching practices differ, revealing a disconnect between how Brazilian instructors believe students learn and how they actually teach.

Furthermore, both French and Brazilian students appear passive in the learning process, assuming the role of spectators who receive information from their teachers and assistance from peers in solving exercises.

Thus, the French model observed in TD sessions for the Algebra and Analysis course at Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1 presents features that could inform the Brazilian model for DIC. Highlights include the dedicated course workload and especially the amount of time allocated for solving exercises—creating space for flexible teaching methodologies, even if only partially, as noted by

Bénéteau et al. (

2016),

Gruber et al. (

2021),

Hyland et al. (

2021),

Krause et al. (

2021),

Ng et al. (

2020),

Olson et al. (

2011),

Reinholz (

2017),

Villalobos et al. (

2021), among others.

Also noteworthy are activities where students solve exercises on the board. However, this moment could be better utilized by incorporating student explanations of their reasoning. Likewise, individual problem-solving could be transformed into collaborative group work, creating opportunities for meaningful discussions as recommended by

Talbert (

2014), leading to real progress for students aiming to become self-regulated, lifelong learners.

The Brazilian DIC1 model observed at UTFPR, Pato Branco campus, also offers valuable elements that could benefit the French model.

Notable practices include the use of mathematical software, such as GeoGebra, and students working in groups. Incorporating software like GeoGebra in DIC1 courses is a tool that facilitates content comprehension (

Božić et al., 2021) and allows for manipulations not possible in the static environment of the chalkboard (

Yimer, 2020).

This approach aligns with the more student-centered learning approach recommended by the Brazilian National Curriculum Guidelines for Undergraduate Engineering Courses (

BRASIL, 2019).

Albalawi (

2018) also highlights the importance of self-regulated and student-centered learning to ensure students are truly involved in the learning process and take responsibility for their own development, becoming lifelong learners.

Mercat (

2022a) highlights the resistance to change in educational institutions. Additionally,

Mercat (

2022b) highlights that the use of active methodologies promotes improvements in retention rates and student engagement.

Certainly, one of the challenges for instructors is to raise student awareness about the importance and necessity of solving exercises in advance. This preparation allows students to bring questions to class and engage in peer discussions, thereby becoming actively involved in the learning process. It is also challenging for instructors to reduce the time spent lecturing and working at the board while students passively listen and copy. A shift toward more interactive and reflective learning activities is needed.