1. Introduction

The digitalisation of education systems is reshaping teaching and learning processes, including approaches to learning assessment and the provision of feedback to students. Digital technologies enable a shift from episodic, predominantly standardised assessment formats toward continuous assessment practices integrated into the learning process, where emphasis is placed on personalised feedback, student self-reflection, and the monitoring of learning progress (

Elkington & Chesterton, 2023;

Maier & Klotz, 2022). Contemporary research literature links formative assessment and other informal assessment practices to the strengthening of students’ self-regulation skills and to a deeper understanding of the learning process (

Kaya-Capocci et al., 2022;

Andrade, 2019;

Panadero et al., 2018). In this context, digital tools enable real-time data collection and analysis, personalised feedback provision, visualisation of learning progress, and alterations in students’ patterns of engagement and responsibility for their own learning.

However, the realisation of these possibilities is not automatic. It depends on the availability and quality of digital technologies, students’ digital competencies, their interaction with information and communication technologies (ICT), and the nature of the digital activities in which they engage during learning. Research shows that students’ digital competence, technological self-efficacy, and attitudes are closely associated with how successfully they are able to use digital technologies for learning and assessment purposes (

Hatlevik & Christophersen, 2013;

Jin et al., 2020;

Reichert et al., 2020). In this context, large-scale international educational studies such as PISA become particularly important, as they systematically collect data on students’ access to technology, their digital experiences, and the characteristics of ICT use for learning purposes.

In the PISA 2022 cycle, the ICT Familiarity Questionnaire made it possible to analyse students’ digital environment across three dimensions: (1) access to digital technologies at home and at school; (2) the frequency and nature of technology use; and (3) students’ attitudes, self-efficacy, and experiences related to ICT use (

OECD, 2023). Secondary analyses of PISA data are widely used to examine the relationships between ICT use and student achievement. For example,

Petko et al. (

2017) demonstrated that it is not the frequency of technology use but rather students’ perceived quality of ICT and their positive experiences with technology that are more significant predictors of learning outcomes. These insights suggest that students’ technological experiences, rather than infrastructure alone, may be crucial for understanding the potential of digitalized assessment.

In the European context, the DigCompEdu framework conceptualises digital competence not only as technical proficiency, but also as the ability to select, use, and evaluate digital resources, analyse learning data, and provide feedback to learners (

Redecker & Punie, 2017;

European Commission, 2022,

2024). This is particularly relevant at the national level, especially in Lithuania, where PISA 2022 data offer a unique opportunity to assess students’ actual ICT use, their technological experiences, and their level of digital literacy (

OECD, 2025).

However, although PISA studies extensively analyse student achievement, far less attention is paid to how students’ ICT resources and practices shape their opportunities to receive digital feedback and what conditions these create for digitalised assessment practices. This raises a key question: What conditions for the effective use of digital resources for academic feedback are created by students’ ICT access, their learning-related technology use, and their perceived digital skills, while accounting for leisure-related technology use as a contextual factor that may indirectly shape students’ engagement in digital learning environments? The PISA 2022 ICT Familiarity data enable this question to be examined systematically and using data-supported analysis. On the other hand, students’ academic progress may be shaped not only by their access to technology or their prior experiences of using it, but also by the extent to which digital tools effectively mediate assessment processes (

Mehrvarz et al., 2021). This raises a second central research question: to what extent does digital feedback account for differences in student achievement independently of ICT access, usage practices, and students’ digital competencies? Moreover, is its effect direct, or does it emerge only in interaction with other features of the digital learning environment?

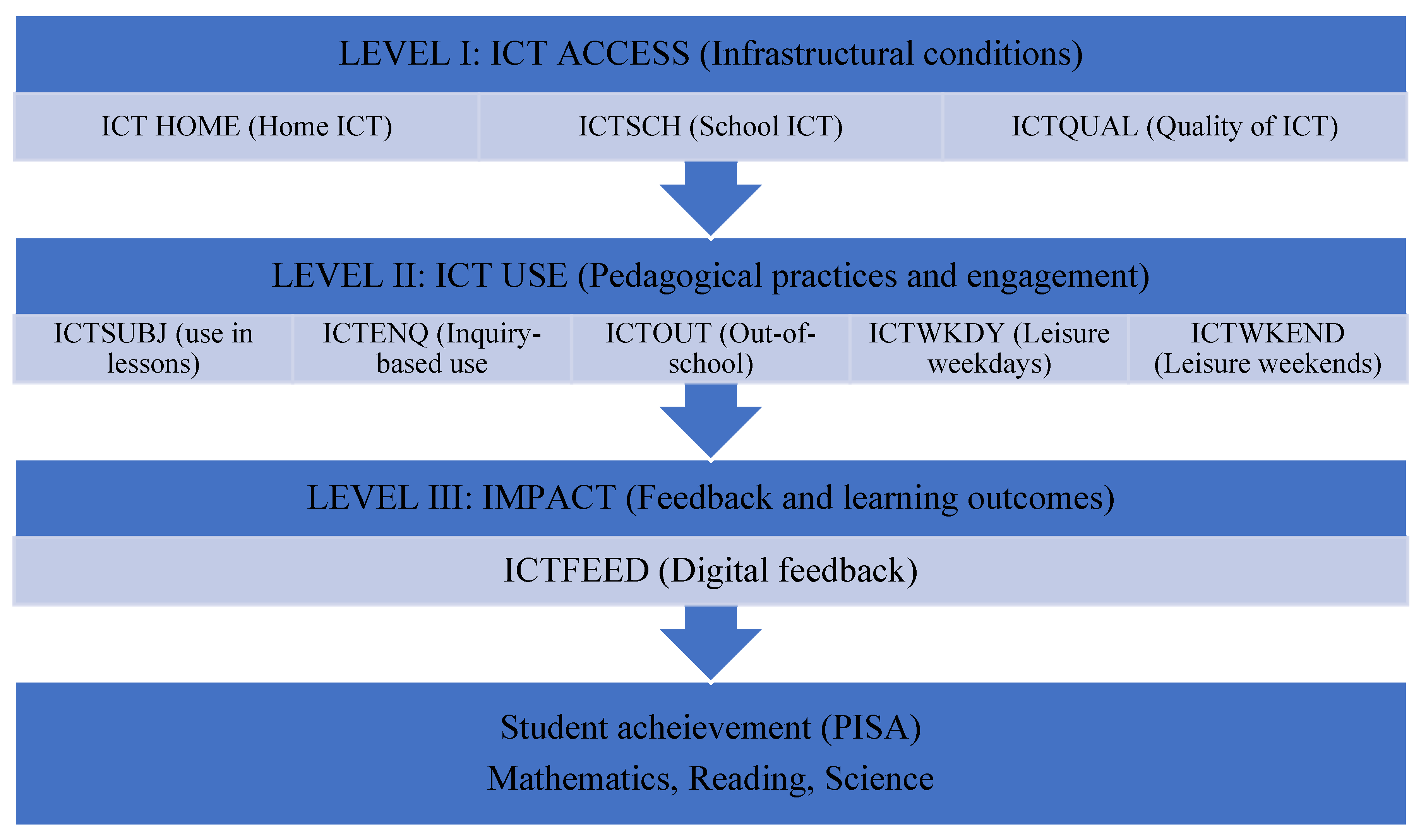

Therefore, the aim of this article is to develop and validate a three-level ICT model that incorporates ICT access and quality (“access”), the nature of ICT use in learning practices (“use”), and the relationship between digital feedback, ICT practices, and student achievement (“impact”). The study seeks to reveal how the interaction among these three levels shapes digital assessment practices and influences students’ academic outcomes in Lithuanian general education schools.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. ICT Infrastructure in Education

Contemporary education systems often operate on the assumption that adequate ICT infrastructure is a prerequisite for effective digital learning and assessment. For many years, national strategies have prioritised access to devices, connectivity, and digital resources, assuming that an increased quantity of technologies would inherently improve teaching and learning processes (

Conrads et al., 2017). However, an expanding body of research demonstrates that mere access to technology does not guarantee pedagogical benefit for students’ learning. OECD analyses of digital transformation emphasise that student learning outcomes are influenced more strongly by the quality, reliability, real-time accessibility, and pedagogical suitability of technologies than by their sheer number or physical presence in schools (

OECD, 2023). Similarly, the DigCompEdu framework highlights that infrastructure represents only an initial condition that must be combined with sound pedagogical design, digital competence, and high-quality digital content to enable effective educational use of technology (

Redecker & Punie, 2017).

Empirical studies confirm that the mere presence of technology at school or at home is not directly associated with student achievement (

Lomos et al., 2023;

Jin et al., 2020;

Gubbels et al., 2020;

Petko et al., 2017;

Vigdor et al., 2014). More consequential than mere access are the ways in which technology is experienced and used in learning contexts, including its pedagogical integration, stability, functionality, and perceived suitability for supporting learning processes. For example,

Petko et al. (

2017) demonstrated that it is students’ experiences with technology, rather than the quantity of technological resources, that account for greater variation in learning outcomes. Rigorous longitudinal evidence further shows that the introduction of home computers and broadband Internet is associated with modest but statistically significant declines in students’ math and reading achievement, suggesting that increased access may introduce distractions or displace productive learning activities when not pedagogically guided (

Vigdor et al., 2014). Evidence from PISA-based analyses further indicates that excessive or leisure-oriented technology use is negatively associated with learning outcomes, reinforcing the view that technology use becomes beneficial only when meaningfully embedded in learning processes (

Gubbels et al., 2020). Similar conclusions are reported in more recent research showing that the impact of technology use is limited when digital tools are integrated in a fragmented or technologically driven, rather than pedagogically grounded, manner (

Jin et al., 2020).

These insights are further supported by the study conducted by

Lomos et al. (

2023), which examined conditions in an education system with exceptionally high levels of ICT provision. Their findings show that even when the infrastructure is nearly ideal, namely sufficient equipment, stable internet connectivity, and a wide range of digital resources—actual ICT use in classroom practice remains limited. When first-order barriers (equipment, internet access, availability) are removed, second-order barriers become decisive: teachers’ beliefs, digital self-efficacy, pedagogical knowledge, school leadership support, and broader cultural factors. The authors found that the effect of infrastructure on teachers’ digital use is weak (β = 0.15), and that meaningful integration depends primarily on collaboration cultures, a coherent school-level ICT vision, and systematic professional development (

Lomos et al., 2023).

These findings suggest that ICT infrastructure constitutes the first, but not the determining, layer of the digital learning ecosystem. While it provides essential conditions, students’ digital experiences, the feedback they receive, and ultimately their learning outcomes depend on how technologies are actually integrated into teaching and learning practices. In this context, the PISA 2022 ICT Familiarity framework offers a data-supported basis for examining how these infrastructural factors operate within the first level of the proposed three-layer model and whether they meaningfully shape students’ digital learning and feedback experiences. Within PISA 2022, this infrastructural layer is operationalised through the indicators ICTHOME, ICTSCH and ICTQUAL, enabling data-supported examination of how access conditions relate to students’ digital practices.

2.2. Digital Feedback

Feedback is regarded in educational research as one of the most important mechanisms of learning regulation, helping students identify gaps in their understanding, recognise areas for improvement, and plan subsequent learning actions (

Panadero et al., 2018;

Brookhart, 2017;

Andrade, 2019). In digital environments, the potential of this mechanism expands even further, as technologies enable feedback to be provided more frequently, more rapidly, in a more personalised manner, and through a wider range of formats (

Maier & Klotz, 2022).

Digital feedback can be delivered in several ways:

Teacher-provided digital feedback, including written comments, audio or video recordings, and screencast explanations;

Peer feedback, facilitated through collaborative tools and peer-assessment processes;

Automated platform-generated feedback, which encompasses immediate hints, error analysis, and personalised learning pathways.

Research shows that multimodal forms of digital feedback enhance students’ self-regulation, engagement, and understanding of learning progress, particularly when feedback is clear, specific, and oriented toward further improvement (

Kaya-Capocci et al., 2022).

Research evidence also provides a clearer understanding of how students perceive digital feedback and which conditions determine its effectiveness. In their study,

Ryan et al. (

2020) emphasise that students view digital feedback as clearer, more detailed, and more structured compared to written comments. More than one-third of students reported that video-based feedback was easier to understand because the teacher’s voice, intonation, and non-verbal cues conveyed additional information (

Ryan et al., 2020).

Moreover, students actively revisited the digital feedback they received, e.g., over two-thirds reported listening to the recordings more than once, indicating that digital feedback is perceived as easily accessible and valuable for learning (

Ryan et al., 2020). The study also showed that digital feedback can have a stronger impact on learning than written comments. Video explanations helped students better understand assessment criteria, more accurately identify areas for improvement, and strengthened their confidence in their ability to enhance their learning outcomes (

Ryan et al., 2020).

However, certain limitations were also identified: some students felt that the feedback lacked sufficient detail, others experienced technical accessibility issues, and shorter recordings did not always provide enough information about specific errors or the underlying assessment logic (

Ryan et al., 2020).

These insights suggest that the effectiveness of digital feedback depends on several interrelated conditions: the pedagogical quality of the feedback provided (e.g., clarity, specificity, and focus on improvement) (

Brookhart, 2017;

Kaya-Capocci et al., 2022), the quality and reliability of the technologies used (

Ryan et al., 2020), teachers’ ability to design and deliver multimodal feedback (

Ryan et al., 2020;

Maier & Klotz, 2022), students’ digital competencies (

Panadero et al., 2018;

Andrade, 2019), and the consistent integration of digital feedback into teaching, learning, and assessment processes (

Panadero et al., 2018;

Brookhart, 2017). Within the structure of PISA 2022, digital feedback (ICTFEED) becomes a central variable that allows for the examination of how ICT infrastructure and students’ usage practices interact within the assessment ecosystem.

2.3. Inquiry-Based and Problem-Based Learning

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is considered one of the most important forms of active learning, in which students investigate phenomena, pose questions, formulate hypotheses, collect and analyse data, and construct knowledge based on evidence (

Bell et al., 2012;

Hmelo-Silver et al., 2007). This learning approach is fundamentally grounded in student activity, autonomy, and the ability to critically evaluate information; therefore, it aligns particularly well with contemporary digital technologies (

Hinostroza et al., 2024).

The integration of digital technologies into inquiry-based learning processes opens up additional opportunities for students to gather and process data, visualise complex phenomena, conduct real-time measurements, and collaborate in solving problems. A systematic analysis of technology use (

Hinostroza et al., 2024) showed that digital tools perform several essential functions in IBL processes: they help structure the inquiry steps, enable the collection of different types of data, support the organisation and analysis of information, facilitate the construction and visualisation of arguments, and allow for the sharing of ideas with peers. In many empirically examined contexts, these technological functions contribute to deeper learning (

McTighe & Silver, 2020), greater learner autonomy (

Effiyanti et al., 2016), and the development of higher-order thinking skills (

Anazifa & Djukri, 2017).

The nature of inquiry-based learning can encourage students’ intensive interaction with digital tools, particularly during the investigation phase, when the inquiry involves data collection, documentation, or analysis that can be supported by digital technologies, such as taking measurements, collecting data, creating notes, recording observations, and analysing information. Research shows that mobile and other digital tools support students in independently exploring their surroundings, documenting phenomena, systematically processing data, and reflecting on their learning progress (

Suárez-Rodríguez et al., 2018;

Chiang et al., 2014). This aligns with broader literature emphasising that inquiry-based activities are associated with the growth of learner agency, that is, students’ ability to initiate and manage their own learning (

Lee & Choi, 2017).

Importantly, the intensive technological engagement inherent in inquiry activities naturally generates more feedback. Digital tools enable students to receive immediate or automated feedback while collecting data, analysing information, or testing hypotheses (

Hong et al., 2017). This cyclical feedback helps learners continuously assess their progress, adjust their actions, and better understand the structure of the learning tasks. Therefore, inquiry-based ICT activities serve not only as a means of active learning but also as one of the most significant sources of digital feedback.

In the context of PISA 2022, the ICTENQ index captures precisely those problem-based and inquiry-oriented activities in which students use digital technologies to search for information, collect data, process it, and present the results of their investigations.

2.4. Links Between the Use of Digital Technologies and Student Achievement

The impact of digital technologies on students’ academic achievement is one of the most debated topics in contemporary educational policy and research. Empirical evidence (

Burbules, 2018) shows that the effects of ICT use are neither linear nor unidirectional: they can be positive, neutral, or negative, depending on the purpose, intensity, and pedagogical integration of technology in the learning process. Consequently, the scholarly literature identifies several distinct patterns of digital impact.

First, the effects of technology can be positive when it is used purposefully and supports higher-order cognitive activities such as problem solving, modelling tasks, or data analysis (

Hu & Yeo, 2020). In such cases, the digital environment helps students to structure knowledge, strengthen argumentation skills, and systematically apply inquiry principles. Second, studies also report neutral effects, typically when ICT use is fragmented, episodic, or oriented toward low-complexity activities that are not directly connected to academic performance (

OECD, 2024). In these situations, technology does not perform a transformative function in the learning process. Third, and perhaps most importantly, an increasing number of studies document a negative relationship between ICT use and student achievement, especially when technologies are used superficially, excessively, or without a clear pedagogical rationale (

Jin et al., 2020). This pattern reflects a broader and increasingly consistent finding in the literature: it is not the mere presence of technology, but the quality of its pedagogical integration, that determines whether digital tools contribute to learning.

Recent findings from an international study on ICT use and student outcomes (

Vargas-Montoya et al., 2023) provide particularly important insights. The study shows that the use of ICT during subject lessons (ICTCLASS) is negatively associated with students’ reading, mathematics, and science achievement, even after controlling for socio-economic background, motivational variables, and school-level factors. The negative effect ranges from −7 to −11 PISA points, indicating that much of ICT integration in classrooms is not connected to deeper or more structured learning, but more often reflects low-complexity activities or excessive, pedagogically ungrounded technology use. A particularly noteworthy finding of this study is that this negative association is stronger in middle-income countries, where the quality of technology, pedagogical integration, and teachers’ digital competence are more likely to be limited. The study shows that in such contexts, the adverse effect of ICT use is significantly greater (β_interaction ≈ +6) compared to high-income countries.

These results highlight a critical trend: the purpose of technology use matters more than its frequency. The impact on students’ achievement depends on whether ICT is integrated as a tool for deeper learning, rather than as a substitute for instruction or an add-on activity without clear pedagogical structure.

The relationship between ICT use and student achievement is complex and context-dependent. It is not the technological tools themselves, but the quality of their integration and the structure of learning processes that determine whether technology becomes a factor that enhances, neutralizes, or even hinders student progress. To analyse these heterogeneous ICT-achievement relationships systematically, the PISA 2022 ICT Familiarity framework offers a set of well-validated indices, such as ICTSUBJ, ICTENQ, ICTOUT, that operationalise distinct forms of technology use and enable data-supported examination of their differential associations with student learning outcomes. In the present study, these indices are incorporated into a multi-level analytical model that examines their relationships with student achievement while accounting for infrastructure conditions and digital feedback practices. Given these contradictory findings, a holistic, multi-level impact model, encompassing infrastructure, usage practices, and digital feedback, is necessary. This is precisely the type of model developed in the present study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context

The PISA 2022 study in Lithuania was conducted in the spring of 2022, one year after an intensive period of remote and hybrid learning during the 2020–2021 school years caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although Lithuanian schools gradually returned to in-person teaching from the spring of 2021, full face-to-face instruction was restored nationwide only in September 2021. This exceptional period resulted in a rapid and substantial increase in the integration of information and communication technologies (ICT) into teaching, learning, and assessment processes. A large share of pedagogical activities, including assignment delivery, monitoring of student progress, communication, and feedback provision—was transferred to digital environments.

Consequently, the PISA 2022 ICT Familiarity questionnaire reflects not only the typical extent of ICT use in Lithuanian schools but also the pandemic-accelerated technological transformation that reshaped students’ and teachers’ digital practices. It is important to note that by 2022, students’ digital experiences had already developed within an environment of intensive technology use, in which ICT had become an essential—rather than supplementary—component of the learning process. International literature likewise highlights that the widespread shift to digital learning during the pandemic created new ICT use practices that did not always persist upon returning to traditional schooling (

OECD, 2023;

UNESCO, 2020).

Despite the rapid expansion of digital technologies, their implementation was not always systematic. Although Lithuanian education policy has increasingly prioritised the development of digital resources and the strengthening of teachers’ digital competences, a number of effective practices established during remote learning were not sustainably integrated once schools returned to in-person instruction (

Gečienė-Janulionė et al., 2024). As a result, the PISA 2022 study was conducted at a time when Lithuanian schools were still in the process of forming stable and long-term strategies for technology use.

This context is essential for interpreting our findings: students’ access to ICT, their perceptions of technology quality, their engagement in digital learning activities, and their experiences of digital feedback in 2022 did not reflect a typical instructional cycle, but were instead shaped by a broader, multifaceted, and rapidly evolving process of digital transformation. This allows us to reasonably argue that the PISA 2022 data capture a “transitional period” in the digital landscape, during which students, teachers, and schools were developing new ICT integration practices grounded in the experiences of the pandemic.

3.2. Research Methods

This study employs a quantitative secondary data analysis (SDA) approach, which enables the re-examination and reinterpretation of large-scale international educational datasets. SDA is particularly well suited for analysing complex phenomena—such as trends in the use of information and communication technologies (ICT), their relationship with learning practices, and their associations with students’ academic outcomes.

Recent research highlights that SDA makes it possible to identify long-term directions in education policy and to assess their effects on both student and teacher outcomes (

Veletić, 2024). Moreover, secondary analysis allows researchers to investigate variable combinations that were not central to the original study design but are conceptually relevant for addressing new scholarly questions. As

Martin (

2025) argues, SDA is especially valuable when grounded in robust theoretical models, as this ensures a structured and coherent approach to interpreting large and complex datasets.

In this study, the SDA approach enables a systematic examination of the PISA 2022 student survey data for Lithuania, distinguishing three levels of ICT use: infrastructure, learning practices, and digital feedback. Working with a dataset of this scale allows for an assessment not only of individual learner characteristics but also of broader systemic processes related to students’ digital habits, access to technology, perceptions of its quality, and learning outcomes.

Secondary data analysis is also particularly suitable for evaluating the effectiveness of technology integration.

Kelly (

2024) emphasises that SDA makes it possible to assess the impact of digital tools across diverse educational contexts, as it draws on extensive and representative datasets that help identify subtle relationships between digital infrastructure, pedagogical practices, and student achievement.

Accordingly, in this study SDA is used not only to analyse Lithuanian students’ digital experiences in the PISA 2022 context, but also to develop a theoretical holistic three-level ICT model that aims to capture the interplay between infrastructure, usage practices, and digital feedback in shaping student achievement.

3.3. Research Variables

This study draws on the PISA 2022 dataset for Lithuania, which enables a structured examination of the conditions underlying the use of information and communication technologies (ICT), students’ digital learning practices, and their relationships with both digital feedback and academic achievement. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the ICT variables are presented in

Table 1. Although several ICT indicators show moderate correlations—particularly between weekday and weekend leisure ICT use, and between learning-related ICT use and digital feedback—these associations remain below thresholds typically associated with problematic multicollinearity. The correlated variables represent conceptually distinct dimensions of the ICT ecosystem, and their inclusion did not result in unstable coefficient estimates, inflated standard errors, or sign reversals across regression models. This suggests that multicollinearity did not materially affect the interpretation of the results.

The analytical model is based on the premise that digital feedback is not an isolated phenomenon, but rather the outcome of a broader ICT ecosystem in which infrastructural, pedagogical, and competence-related factors interact. For this reason, both dependent and independent variables are analysed and grouped into four conceptually coherent categories.

The study uses the official PISA 2022 ICT Familiarity indices (e.g., ICTHOME, ICTSCH, ICTQUAL, ICTSUBJ, ICTENQ, ICTOUT, ICTFEED), which are constructed and psychometrically validated by the OECD using internationally standardised procedures documented in the PISA Technical Report. Because the present analysis examines structural relationships among established constructs rather than developing new measurement models, we rely on these OECD-validated indices and do not re-estimate CFA/MGCFA or alignment models within this study. This approach is consistent with common practice in secondary analyses of PISA data and supports cross-study comparability.

The primary dependent variable is the PISA index ICTFEED, which captures how frequently students receive feedback through digital means. This index encompasses teacher-provided comments in virtual learning environments, peer feedback delivered through collaborative platforms, and automated feedback generated by educational software. ICTFEED is selected as the central analytical indicator because it provides insight into how students’ technological environment and usage patterns reshape assessment practices and what conditions support the development of digital feedback processes in Lithuanian schools.

The first group of independent variables, ICT resources and their quality, represents the infrastructural factors forming the technological foundation of the learning environment. This category includes three indices: ICTSCH, which captures the technological resources available at school; ICTQUAL, which reflects students’ perceived quality of digital equipment and platforms; and ICTHOME, which describes the technological resources accessible in the home environment. Rather than serving as direct indicators of digital assessment or feedback practices, these variables describe the infrastructural conditions that enable or constrain the implementation of digitally mediated assessment and feedback.

The second group of variables is related to students’ ICT use in learning and leisure contexts, as practical engagement with technology shapes students’ digital comfort, skills, and confidence in using digital tools. This category includes four indices describing learning-related ICT practices: ICTSUBJ, capturing the frequency of ICT use during subject lessons; ICTENQ, indicating the use of ICT for inquiry-based and problem-based activities; ICTOUT, reflecting digital learning activities outside the classroom; as well as two leisure-related variables, ICTWKDY and ICTWKEND, which measure the extent to which students use digital technologies for entertainment on weekdays and weekends. Rather than serving as direct indicators of digital feedback, these variables capture students’ broader patterns of digital engagement, which form the contextual conditions under which digital feedback is encountered and processed.

The third group of variables consists of students’ perceived digital competences, measured through the ICTEFFIC index. This index captures students’ self-efficacy in the domain of digital technologies—their ability to search for and evaluate information, create digital content, apply algorithmic thinking, engage in programming, and solve technological problems. This variable is essential because, even when access to technology is sufficient and digital practices are intensive, the quality of learning and the ability to interpret digital feedback largely depend on students’ competence levels.

Finally, the study incorporates students’ performance in the three core PISA domains, namely mathematics, reading, and science. These indicators are included as control variables, enabling an assessment of whether digital feedback and ICT use practices interact with students’ academic performance. Examining these indicators makes it possible to determine whether ICTFEED functions as a learning-enhancing mechanism or, conversely, as a compensatory mechanism that is more prevalent among lower-achieving students.

In sum, the variables included in this study are selected to reflect the logic of the proposed three-level ICT model, moving from infrastructural factors to usage practices and student competences, and ultimately examining their interaction with digital feedback and learning outcomes. This structure enables a holistic analysis of the digital learning ecosystem in Lithuanian general education schools, based on the Lithuanian PISA 2022 sample.

3.4. Sample

The PISA 2022 study in Lithuania employed a two-stage, stratified probability sampling design with a clustered structure, following OECD methodology (

OECD, 2024). In the first stage, a representative sample of schools was drawn from the national school frame; in the second stage, a random sample of 15-year-old students was selected within each participating school. This design ensures that every population unit has a known, non-zero selection probability, minimising sampling bias and allowing reliable extrapolation to the national population of Lithuanian 15-year-olds.

In total, 7257 students from 291 schools participated in PISA 2022 in Lithuania, providing a statistically reliable and nationally representative sample. Because PISA is a population-level rather than a convenience survey, data analysis relies not on raw sample counts but on weighted estimates adjusted for the sampling design.

Three methodological elements are essential for valid analysis of PISA data:

Sampling weights. Student and school weights correct for unequal selection probabilities and ensure national representativeness. Analyses conducted without weights would yield biased estimates.

Plausible values (PVs). PISA proficiency scores are not single point estimates but sets of latent ability indicators (typically 10 PVs per domain). All statistical models must incorporate all PVs; using a single PV would underestimate variance and produce unreliable results.

BRR replicate weights. PISA uses Balanced Repeated Replication (BRR) with Fay’s adjustment to estimate standard errors under stratified and clustered sampling. BRR replicates must be included in each regression or SEM model to avoid downward-biased or incorrect standard errors.

Adhering to these methodological procedures is essential for valid interpretation of PISA data and for ensuring that the findings reflect, as accurately as possible, underlying patterns within the population of Lithuanian 15-year-olds. All models, estimates, and standard errors reported in this study follow these sampling and estimation principles.

3.5. Statistical Methods

To estimate relationships between variables, linear regression analysis was conducted while fully accounting for the PISA sampling design. Under these conditions, the resulting regression coefficients represent population-level estimates, rather than sample-based coefficients, and standard errors were computed using Balanced Repeated Replication (BRR). Consequently, both β coefficients and their standard errors (s.e.) are adjusted for unequal selection probabilities and within-cluster measurement variance—that is, they are adjusted for the complex survey design.

The tables in the article report R

2 values, indicating the proportion of variance in student competence explained by the regression model at the population level (

OECD, 2023), together with their standard errors. Standardised β coefficients are interpreted as effect-size indicators of the independent variables: β ≈ 0.10 is considered small, β ≈ 0.20 medium, and β ≥ 0.30 an educationally meaningful effect (

Hair et al., 2019;

Rutkowski & Rutkowski, 2018). Beta coefficients and t-values are calculated using replicate-design adjusted standard errors and therefore must be interpreted at the population rather than sample level. Interpretation is based on both statistical significance (t ≥ |2.58| for

p < 0.01, or t ≥ |1.96| for

p < 0.05) and effect size, following

Cohen (

1988) and

von Davier and Lee (

2019).

Variable means, standard errors, and correlations are presented as population-level estimates, computed using sampling weights and replicate-weight variance adjustments. All analyses were performed using the IEA IDB Analyzer, which automatically applies sampling weights, plausible values, and BRR replicate weights.

In the secondary analysis of PISA data, we employed item-level modelling alongside the official PISA indices, as different aspects of ICT infrastructure (such as classroom access, technical functioning, speed, teachers’ preparedness, etc.) may have unequal or even divergent relationships with digital feedback. Item-level analysis enables a transparent demonstration of how operationalisation choices influence results and reduces the risk that a composite index may obscure critical components.

In addition, considering the international context, we tested measurement invariance (MGCFA/alignment) and conducted sensitivity analyses, comparing the conclusions with those obtained using the OECD-reported indices. This procedure follows PISA methodological standards for scale construction and replicability and aligns with good research practice, whereby decisions to use single-item or multi-item indicators are explicitly justified through theory and validity evidence.

The analytical framework follows an SEM-inspired conceptual logic but is implemented through sequential regression models serving as structural proxies rather than a full latent-variable SEM, in line with the use of OECD-validated PISA indices and complex-sample estimation requirements. Correlations among ICT indicators were examined and found to remain within acceptable ranges; the stability of coefficients across model specifications and the absence of inflated standard errors indicate that multicollinearity did not materially influence the results.

4. Results

4.1. The Impact of ICT Infrastructure on Digital Feedback

To assess the influence of the first level of the model, namely ICT infrastructure, three indicators of digital technology availability were included in the regression model: ICT availability at home (ICTHOME), ICT availability at school (ICTSCH), and the perceived quality of digital technologies at school (ICTQUAL), as measured in the Lithuanian PISA 2022 sample.

Table 2 presents the regression results examining the effects of ICT infrastructure indicators (ICTHOME, ICTSCH, ICTQUAL) on students’ experiences of digital feedback (ICTFEED) in the Lithuanian PISA 2022 sample. The analysis was conducted using the full PISA complex survey design corrections (weights, BRR, and plausible values). Consequently, the obtained β, s.e., and t estimates are interpreted at the population level, rather than at the sample level. The results show that among the three indicators, only the perceived quality of school-level technology (ICTQUAL) has a statistically significant effect on students’ digital feedback experiences: β = 0.26, t = 18.23,

p < 0.001. The model’s explanatory power is modest, with R

2 = 0.07 (s.e. = 0.10).

In contrast, ICT availability at home (ICTHOME) and at school (ICTSCH) were not significant predictors in the model. This finding is consistent with international research demonstrating that the quantity of available technologies does not in itself ensure pedagogical value; rather, the key factors are the stability, speed, functional suitability, and reliability of the equipment, as well as the availability of effective technical support.

These results align with the theoretical foundation of the article: ICT infrastructure represents a necessary but not sufficient precondition for digital feedback to function. It is the quality of technology that enables meaningful digital feedback processes to emerge, yet even high-quality infrastructure does not guarantee that students will consistently experience such feedback in practice.

4.2. Use of Digital Resources for Feedback

To examine the manifestation of digital feedback in this study, we employed the PISA 2022 questionnaire scale Support or feedback via ICT, which measures how frequently students receive feedback through digital technologies during the learning process. The scale includes four situations that represent distinct sources of digital feedback:

- (1)

Feedback or comments provided by the teacher in a virtual learning environment;

- (2)

Peer feedback on the student’s work;

- (3)

Feedback generated by educational software or applications; and

- (4)

Responses received while completing tasks in specialised learning programs or apps.

Each of these aspects is rated on a five-point frequency scale, ranging from “Never or almost never” to “Every day or almost every day”. This structure makes it possible to assess the extent to which students experience digital feedback across different instructional contexts.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between students’ experiences of digital feedback (ICTFEED), ICT availability, instructional uses of digital technologies, and students’ digital competences in the Lithuanian PISA 2022 sample. Students’ responses reveal a high degree of heterogeneity in their experiences with digital feedback. For all four activity categories that make up the Support or feedback via ICT scale, the calculated Qualitative Variation Index (QVI) values exceed 0.95, indicating that students’ experiences are highly diverse and unevenly distributed. This suggests that the use of digital resources for providing feedback is far from standardised across Lithuanian schools; rather, these practices remain inconsistently embedded within the national education system.

When examining individual types of digital feedback, teacher-provided digital comments emerge as the most common form: approximately 41% of students report receiving such feedback at least once a week. Peer feedback mediated through digital tools is somewhat less frequent (33%), while automated feedback generated by educational software or applications is reported by only 31% of students. Thus, teacher-delivered digital feedback is the most prevalent, whereas automated or algorithmic feedback is the least common.

A substantial proportion of students—between 30% and 40%, depending on the activity—report rarely or never receiving any form of digital feedback. This indicates that such practices are not yet a routine component of students’ learning experiences. Digital feedback in Lithuanian general education schools remains fragmented, unevenly implemented, and highly heterogeneous.

4.3. Inquiry-Based Learning

The implementation of inquiry- and problem-based learning occurs both in the school environment and within virtual learning platforms. Students may receive this type of feedback either in the classroom or while completing tasks outside of school, meaning that it constitutes an individually experienced component of the learning process. For this reason, the dependent variable, namely the digital feedback index (ICTFEED), is analysed at the student level.

At the same time, digital feedback may depend not only on individual student experiences but also on the broader school environment, where technologies are available and pedagogically integrated. Therefore, the regression models include school-level variables, calculated by aggregating (taking school means of) relevant indicators in order to distinguish school-level effects from individual-level variation. These school-level indices represent key aspects of infrastructure and instructional practice (ICTSCH_mean, ICTQUAL_mean, ICTSUBJ_mean, ICTENQ_mean).

Table 3 presents the regression results for school-level ICT predictors of students’ digital feedback experiences (ICTFEED) in the Lithuanian PISA 2022 sample. The regression model shows that school-level factors account for approximately 2% of the variance in students’ digital feedback experiences (R

2 = 0.02; s.e. = 0.004). This indicates that digital feedback is largely an individual-level phenomenon, rather than a uniformly implemented school-wide practice.

Among all school-level indicators included in the analysis, only two dimensions demonstrated statistically significant effects. The strongest effect was observed for technology use in inquiry-based learning activities (ICTENQ_MEAN), β = 0.14, t = 9.62, p < 0.001. This suggests that in schools where technologies are more frequently integrated into inquiry, project-based, and problem-solving activities, students tend to receive somewhat more digital feedback.

A second, smaller but still significant effect was found for perceived technology quality (ICTQUAL_MEAN): B = 0.12 (s.e. = 0.05), β = 0.03, t = 2.37, p < 0.05. This indicates that reliable, functional, and pedagogically suitable technologies create enabling conditions for the use of digital systems to provide feedback.

By contrast, the quantity of ICT resources in schools and the frequency of technology use during regular subject lessons do not significantly predict students’ digital feedback experiences. This finding reinforces the broader conclusion that the mere presence or routine use of technologies in classrooms is insufficient; rather, it is the purposeful, inquiry-oriented integration of ICT, supported by high-quality technological infrastructure, that is associated with more frequent digital feedback.

4.4. The Influence of Digital Feedback on Student Achievement

In addressing the second research question, the aim is to determine how students’ interaction with information and communication technologies relates to their achievement in mathematics, reading, and science placing particular emphasis on the use of digital tools to provide feedback during the learning process. The analysis considers not only the use of digital feedback itself, but also other forms of students’ digital experiences, such as access to technological resources at home and at school, the use of technologies for school-related activities both inside and outside the classroom, and digital leisure use. The associations between these factors and student achievement are interpreted using population-level regression estimates adjusted for the PISA complex sampling design.

To examine the relationship between ICT-related factors, digital feedback, and student achievement in mathematics, reading, and science, population-level regression models were estimated using PISA 2022 data.

Table 4 presents the standardized regression coefficients (β), standard errors, and t-values for the effects of ICT-related variables and digital feedback (ICTFEED) on student achievement across the three PISA domains. Analysis of the PISA 2022 data shows that the effects of digital factors on student achievement are stable across all assessment domains, namely mathematics, reading, and science literacy, indicating the reliability and consistency of the results. The direction of effects is replicated across different learning domains, suggesting that the identified patterns are not incidental but reflect a broader structural influence of digital learning conditions.

The impact of digital factors on student achievement is not uniform. Although the models explain only a relatively small share of the variance in achievement (approximately 10%; R2 = 0.090, 0.106, 0.100), a clear distinction emerges between digitally supported learning activities and non-productive digital behaviours. The results show that the perceived quality of digital resources at school (ICTQUAL) and the use of ICT for learning-related activities outside the classroom (ICTOUT) are consistently positively associated with achievement in all three domains. This suggests that higher performance is linked not to the quantity of technological resources available at school or at home, but rather to the quality and purposeful use of these resources in supporting autonomous learning.

In contrast, intensive ICT use for leisure, both on weekdays and weekends (ICTLAISVALAIKIS), has a negative effect on achievement across all domains (β = −0.21, −0.19, −0.20, respectively). This likely indicates that excessive digital leisure competes with time allocated to learning or reflects unproductive patterns of ICT engagement. More frequent digital feedback (ICTFEED) is likewise negatively associated with student achievement (β = −0.14, −0.16, −0.16), which may suggest that digital feedback practices are used more intensively in contexts where students demonstrate lower academic performance.

Table 5 compares the explanatory power (R

2) of the regression models estimated with and without digital feedback (ICTFEED) for mathematics, reading, and science literacy. A comparison of the regression models with and without ICTFEED shows that the inclusion of digital feedback increases the explained variance in achievement only marginally but consistently (ΔR

2 ≈ 0.013–0.017). This systematic yet modest improvement in all three competence domains indicates that more frequent digital feedback adds only limited explanatory power once ICT access and usage contexts are already controlled for. At the same time, the negative regression coefficients, each exceeding |0.10|, suggest that digital feedback is more commonly associated with lower-achievement contexts: it appears to reflect situations in which students require additional support rather than functioning as a factor that directly enhances academic performance.

In summary, technology acts as a learning-enhancing factor only when it is integrated into contexts that foster deep learning and learner autonomy. Intensive digital leisure use (ICTWKDY and ICTWKEND; national label: ITCLAISVALAIKIS) is more characteristic of students with lower PISA achievement, regardless of the assessment domain. The negative association between ICTFEED and achievement can be interpreted as a compensatory effect: digital feedback is more frequently provided to students experiencing learning difficulties, thereby reflecting a need for support rather than indicating the direct impact of digital tools on learning outcomes. This interpretation is consistent with prior research showing that feedback and digitally supported assessment practices are often intensified for lower-achieving students as part of remedial or supportive instructional strategies, particularly in data-informed and formative assessment contexts (

Brookhart, 2017;

Panadero et al., 2018;

Petko et al., 2017).

5. Synthesizing the Three-Level Model from the Findings

Taken together, the data-supported findings provide a coherent basis for the proposed three-level ICT model, capturing the progression from access to use and impact. At the first level (access), ICT infrastructure was operationalised through ICTHOME, ICTSCH and ICTQUAL. The regression analyses showed that only perceived quality of ICT at school (ICTQUAL) significantly predicted students’ experiences of digital feedback (ICTFEED), whereas ICT availability at home and at school had no meaningful effect. This indicates that infrastructure, as conceptualised in the model, should not be understood in terms of sheer device counts, but rather as functional and reliable access conditions that make digital feedback technically possible.

The second level (use) focuses on students’ digital practices in different learning contexts. Here, the results demonstrate that ICT use in inquiry-based learning activities (ICTENQ) and ICT use for school-related activities outside the classroom (ICTOUT) are the strongest predictors of digital feedback at the student level, while routine technology use during subject lessons (ICTSUBJ) has only a small and practically negligible effect. Additional analyses further show that students’ digital leisure use (ITCLAISVALAIKIS) and perceived digital self-efficacy (ICTEFFIC) are also related to ICTFEED, but with more modest effect sizes. In line with the model, this suggests that digital feedback emerges primarily in contexts of active, inquiry-oriented and extended learning, rather than from generic or episodic ICT use in regular lessons.

At the third level (impact), the model links digital feedback and ICT practices to student achievement in mathematics, reading and science. The findings reveal a consistent pattern across all three domains: ICTQUAL and ICTOUT are positively associated with achievement, whereas intensive digital leisure (ITCLAISVALAIKIS) and digital feedback (ICTFEED) are negatively associated with performance. The small but systematic increase in explained variance when ICTFEED is added to the models, combined with its negative coefficients, supports the interpretation of digital feedback as a compensatory mechanism: it is used more frequently in lower-achieving contexts, reflecting a need for additional support rather than exerting a direct positive effect on learning outcomes.

On this basis, the data-supported findings substantiate the three-level model in two ways. First, they confirm that infrastructure is a necessary but not sufficient condition: only high-quality ICT creates the conditions for digital feedback, and even then, feedback practices depend on how technologies are pedagogically integrated. Second, they show that pedagogical use is the central mediating layer: inquiry-based and out-of-class ICT activities are the main pathways through which access conditions translate into students’ digital feedback experiences, which in turn are embedded in complex, partly compensatory relationships with achievement. Thus, the model derived from the findings conceptualises digital feedback not as an isolated variable, but as an emergent outcome of interactions between access, use, and impact within the broader digital learning ecosystem.

6. Discussion

This study sought to develop and conceptually articulate a three-level ICT model that describes a logical sequence from the availability of technologies (“access”), to their pedagogical use for learning (“use”), and to the association between digital practices and student achievement (“impact”) (see

Figure 2). Using PISA 2022 data from Lithuania, we then examined whether data-supported patterns were consistent with this conceptual structure. The results revealed a coherent and clearly articulated structure, while also exposing several tensions and paradoxes that reflect the complexity of the digital learning ecosystem in Lithuanian schools.

The figure illustrates the conceptual structure of the proposed model, distinguishing between ICT Access (infrastructural conditions), ICT Use (learning-related and leisure-related practices), Digital Feedback (ICTFEED), and Student Achievement (mathematics, reading, and science). Solid arrows represent enabling relationships consistent with the access–use–impact logic, while the dashed arrow indicates the compensatory association between digital feedback and achievement observed in the data supported analysis. The model is examined using PISA 2022 data from Lithuania.

The analysis of the first level of the model-ICT infrastructure-confirmed that the mere presence of technological resources at home or at school is not a sufficient condition for the formation of digital feedback practices. This finding aligns with international research (

OECD, 2023;

Petko et al., 2017), which emphasises that access to technology alone does not generate pedagogical value. In our study, only one infrastructural indicator proved significant—the ICT quality index (ICTQUAL). This demonstrates that it is stable, reliable, and pedagogically suitable technologies that create the actual conditions for using digital assessment and feedback tools. This is consistent with the conclusions of

Lomos et al. (

2023), who argue that “first-order barriers” have become less relevant in contemporary schools and that the decisive factors are the functional adequacy of technologies and the quality of their integration, rather than their mere availability.

The second level of the model—ICT usage practices, emerged as the strongest and most consistent predictor of digital feedback. The results show that inquiry- and problem-based activities (ICTENQ) and learning activities conducted outside the classroom (ICTOUT) are the primary factors explaining variation in ICTFEED. These practices encourage students to engage actively with digital systems, complete tasks, receive automated or teacher-provided feedback, and reflect on their learning progress. This pattern is consistent with literature examining the interaction between inquiry-based learning, problem-solving pedagogies, and digital forms of feedback (

Kaya-Capocci et al., 2022;

Hattie & Clarke, 2020).

By contrast, ICT use during subject lessons (ICTSUBJ) showed only a very weak effect, which aligns with evidence that routine, instructional, and teacher-directed uses of technology rarely generate added learning value (

OECD, 2023). This supports the conclusion that digital feedback does not arise from the mere presence of technology in lessons, but rather from student engagement in active, creative, and self-directed forms of learning.

The third level of the model revealed one of the most noteworthy and theoretically significant findings of the study: digital feedback (ICTFEED) is consistently negatively associated with student achievement across all three PISA domains. This relationship remains significant even when controlling for infrastructural factors, learning-related ICT use, and digital leisure. This pattern is congruent with research suggesting that feedback in educational settings often functions as a compensatory mechanism, more frequently provided to lower-achieving students (

Brookhart, 2017;

Hattie, 2009). Studies of digital, particularly recorded, feedback practices similarly show that teachers tend to provide more detailed comments to students who require greater support, and that these students often revisit such feedback multiple times (

Ryan et al., 2020).

Therefore, the negative association between ICTFEED and student achievement is unlikely to exist because digital feedback reduces performance; rather, it emerges because digital feedback functions as an intervention tool directed primarily at students who experience learning difficulties. This reflects a broader international pattern: feedback is not distributed uniformly across learners, but instead “follows” students’ needs rather than their outcomes.

Therefore, the negative association between ICTFEED and student achievement is unlikely to reflect a detrimental effect of digital feedback on learning; rather, it appears to emerge because digital feedback functions as a compensatory intervention primarily directed at students experiencing learning difficulties. This reflects a broader international pattern in which feedback is not distributed uniformly across learners, but instead tends to “follow” students’ needs rather than their outcomes.

At the same time, these findings align with a broader body of research indicating that increased or unguided ICT use may have neutral or negative associations with student achievement when digital technologies are not embedded in pedagogically meaningful practices (

Vigdor et al., 2014;

Jin et al., 2020). The compensatory interpretation of ICTFEED is further supported by formative assessment research showing that feedback is often intensified for lower-achieving students as part of remedial and supportive instructional strategies, rather than functioning as a direct driver of achievement gains (

Brookhart, 2017;

Panadero et al., 2018).

In summary, this study provides data-supported evidence support for a three-level digital learning model, revealing a clear structural sequence:

Infrastructure creates the necessary conditions, but does not exert a direct effect on its own.

Active, inquiry-based use of ICT has the strongest influence on digital learning processes.

Digital feedback reflects students’ learning needs, rather than acting as a mechanism that directly enhances achievement.

Taken together, the model offers a deeper understanding of how technologies influence learning and helps explain the often contradictory findings in ICT research. The study emphasises that digital resources become effective learning factors only when they are integrated into meaningful, active, and self-directed learning practices. Digital feedback, in turn, serves as an important indicator of individual learning trajectories and support needs rather than a direct driver of improved learning outcomes.

7. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged.

First, the proposed three-level ICT model is developed and examined using secondary data from PISA 2022, which, while offering strong methodological rigour and international comparability, constrains the analysis to variables and indicators defined within the PISA framework. As a result, the model captures students’ self-reported access to and use of digital technologies, as well as their perceptions of digital feedback, but does not include direct measures of classroom practices or instructional decision-making processes.

Second, the study does not incorporate the perspectives of teachers or other educational professionals. Consequently, the model reflects a student-centred, system-level view of digital practices and feedback, rather than practitioners’ interpretations of how digital feedback is designed, implemented, and adapted in everyday teaching. Including teachers’ voices through qualitative interviews, surveys, or mixed-methods designs would allow future research to validate, refine, or challenge the conceptual assumptions underlying the model.

Third, due to the cross-sectional nature of the PISA data, the observed associations between ICT access, usage patterns, digital feedback, and achievement should not be interpreted as causal relationships. Longitudinal or experimental studies would be necessary to examine the temporal dynamics of digital feedback practices and to test compensatory or developmental mechanisms more directly.

The analysis is limited to the Lithuanian PISA 2022 sample. While this allows for a contextually grounded interpretation of the digital learning ecosystem in Lithuanian general education schools, caution is required when generalising the findings to other national or educational contexts.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

Despite these limitations, this study makes a significant and original contribution by providing a data-supported, theoretically grounded three-level model that clarifies how ICT access, pedagogical use, and digital feedback interact within a national education system. Rather than treating technology as a uniform input, the model conceptualises digital feedback as an outcome of pedagogical engagement and learning practices, offering a more nuanced understanding of how digital learning ecosystems function.

Applying this model to the Lithuanian context, the findings offer a renewed perspective on the digital learning ecosystem in Lithuanian schools. The data-supported analysis indicates that digital feedback is not an automatic or self-emerging phenomenon; rather, it is shaped not by the quantity of technology, but by its quality, the culture of pedagogical use, and students’ learning experiences. Accordingly, the practical recommendations derive directly from these context-specific, data-supported conclusions.

First, the results demonstrate that the quality of technology is the only significant infrastructural predictor of students’ digital feedback experiences. Neither the amount of equipment available at home nor the quantity of devices at school has a meaningful effect on whether students receive digital feedback. This indicates that digital education policy should shift from the logic of “more devices” toward the development of a functional, reliable, and pedagogically integrated digital ecosystem. Investment priorities should emphasise quality rather than quantity—focusing on infrastructure that ensures stability, technical support, and the functional conditions necessary for meaningful digital assessment.

Second, the study revealed that the strongest conditions for digital feedback emerge from inquiry- and problem-based learning activities (ICTENQ), as well as learning activities taking place outside the classroom (ICTOUT). These practices generate the most meaningful forms of feedback. This confirms that digital technologies are most effective when integrated into active, autonomous, and higher-order learning processes. Schools should therefore purposefully cultivate an inquiry-based learning culture: strengthen traditions of project work, investigation, and experimentation; prepare teachers to design cognitively demanding tasks; and ensure that digital tools are used in transformative, not merely supplementary, ways.

Third, routine use of ICT during subject lessons (ICTSUBJ) has only a very weak effect on the intensity of digital feedback. This suggests that increasing the formal presence of technology, if not aligned with pedagogical aims, is not effective. Our data reinforce the growing argument in international literature that technology alone does not transform learning—learning changes only when pedagogical practices change together with technology.

Fourth, a consistent negative relationship between digital feedback and achievement was observed across all three PISA domains, even after controlling for ICT access, learning-related use, and digital leisure. The most plausible interpretation is a compensatory effect: students who receive more feedback tend to be those who struggle academically. Therefore, in schools, digital feedback should not be conceptualised as a technical feature, but as a pedagogical support mechanism aimed at providing individualised assistance to students facing learning difficulties.

Fifth, digital leisure activities showed a consistent negative association with all domains of achievement. This underscores the need to link digital literacy education with media hygiene, time management, and critical attention skills. It also signals an important area of responsibility for both schools and families in promoting healthy digital behaviour.

The overarching conclusion of this model is that digital learning constitutes a multidimensional ecosystem, not an isolated factor. The impact of ICT on student experiences and outcomes depends on the interplay of three interconnected components:

- (1)

The quality of infrastructure;

- (2)

The nature of technology-enabled learning practices;

- (3)

The learning processes through which meaningful digital feedback is generated.

The three-level model developed in this study provides a conceptual foundation for EdTech policy analysis: only by viewing technology as part of a broader pedagogical system is it possible to understand its real impact on learning.

Based on this model, a more coherent direction for EdTech policy can be formulated: technologies should be invested in and implemented not because they are modern, but because they enable pedagogical practices that foster deep learning, self-regulation, and meaningful feedback. It is precisely this interplay of the “access–use–impact” dimensions that opens opportunities to build a digital learning ecosystem which not only modernises the educational process but genuinely contributes to student progress.

The findings of this study have implications for multiple stakeholders. For researchers, the proposed three-level ICT model offers a transferable conceptual framework that can be replicated and tested in other national contexts and extended through longitudinal and mixed-methods designs. For learners, the results highlight the importance of purposeful, learning-oriented uses of digital technologies and the development of self-regulation and balanced digital habits. For educators, the study reinforces that digital feedback is a pedagogical practice requiring the design of inquiry-based and cognitively demanding learning activities, rather than a technical outcome of technology use. For course designers, the findings underscore the need to embed digital feedback mechanisms within coherent learning designs aligned with learning goals and assessment criteria. At the institutional level, schools should prioritise the quality, reliability, and pedagogical usability of digital infrastructure and foster a shared culture of reflective digital practice. Finally, at the policy level, EdTech strategies should focus less on expanding access and more on supporting pedagogically grounded uses of technology that enable meaningful feedback and deep learning.