In second and foreign language learning (SL/FL), learners’ Willingness to Communicate (WTC) in the target language, as the ultimate goal of learning, plays a crucial role (

MacIntyre et al., 1998;

MacIntyre, 2010), as the communicative language teaching approach has developed.

MacIntyre et al. (

1998) perceive WTC in the L2 context as “readiness to engage in a stretch of local interaction at a particular time with a particular person” (p. 547). WTC has been conceptualized through both trait-like (stable across situations;

Cetinkaya, 2005;

Clément et al., 2003) and dynamic situational perspectives (fluid, context-dependent;

Kang, 2005;

MacIntyre, 2007).

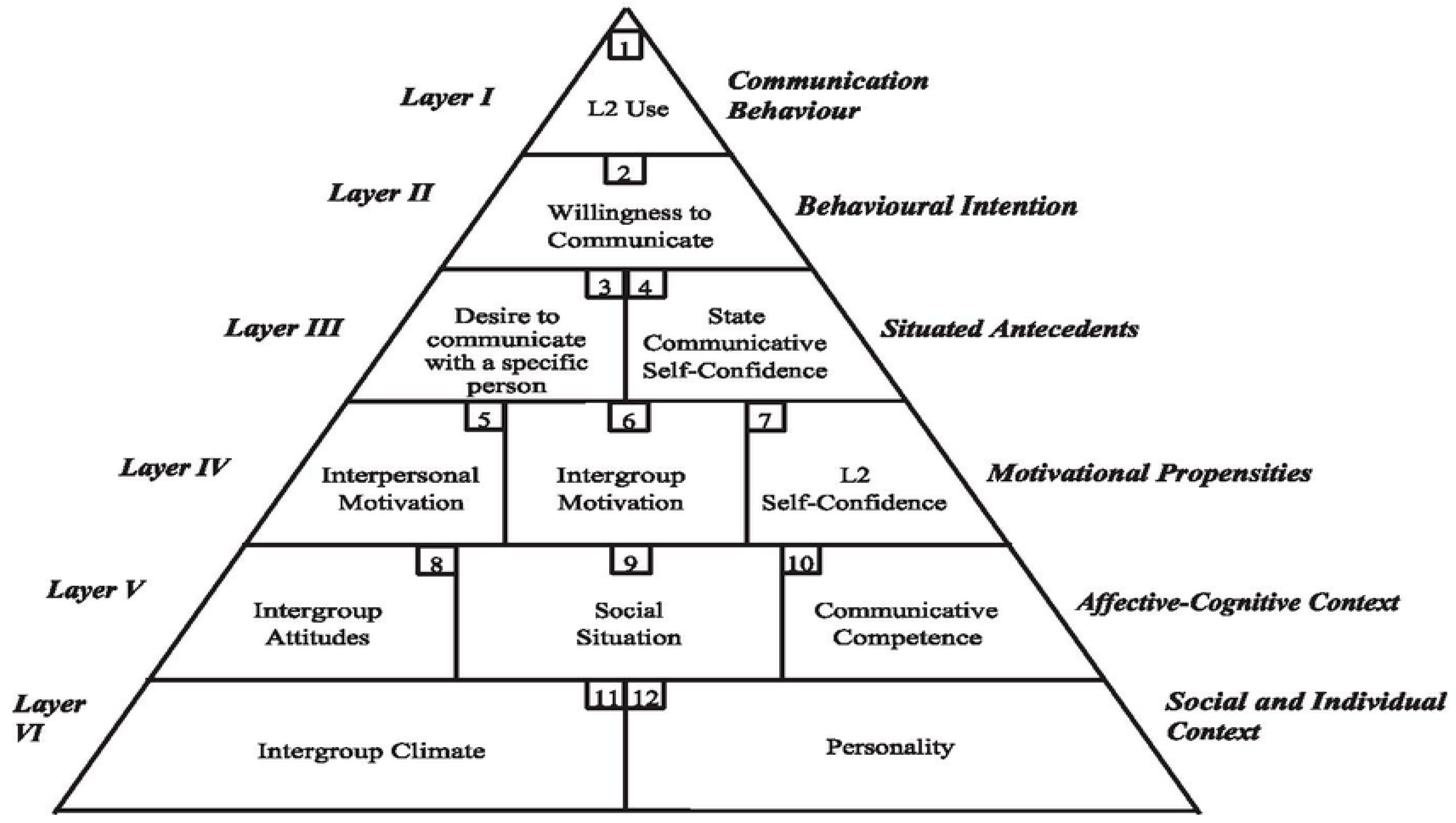

MacIntyre et al.’s (

1998) pyramid model, given in

Figure 1, integrates both perspectives across six layers: stable impacts (layers IV–VI: motivational propensities, affective-cognitive context, intergroup climate) and dynamic contextual impacts (layers I–III: behavioral intention, situated antecedents, communicative competence). From this model, it can be inferred that several factors contribute to WTC, which is a behavioral intention.

1.1. Variables Affecting L2 WTC

To investigate the variables that influence WTC, recent research has examined factors such as teacher support and grit. Academic, instrumental, and emotional TS has a strong influence on WTC (

Zarrinabadi, 2014;

Hejazi et al., 2023), the level of learner motivation and engagement (

Chiu et al., 2023;

Tao et al., 2022), and the overall language learning experience (

Peng & Woodrow, 2010). Recent empirical studies still confirm the essential role of teacher support.

Yang et al. (

2024) have shown, using the sequence mediation model, that teacher support improves both grit and FLE, which, in turn, improves WTC, thereby directly aligning with our theoretical construct. In the Pakistani-specific scenario,

Habib et al. (

2025) found that supportive instructional practices and teachers’ flexible communication strategies play a crucial role in promoting students’ enjoyment. Similarly, Khatoon, Samson, and Jamshed concluded that teacher attitudes and classroom climate significantly impact learners’ affective states and communicative behavior (

Khatoon et al., 2024).

John (

2024) also found that the gamification methods improve the teacher–student relationship and teacher immediacy, minimizing affective communication barriers. As explained by

Duckworth et al. (

2007) and

Teimouri et al. (

2019,

2020), grit is a significant personality trait that can influence learners’ persistence in language learning. L2 grit is theoretically distinct from related motivational constructs. Unlike general motivation (desire/reasons for learning;

Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015), grit emphasizes sustained effort despite setbacks rather than initial enthusiasm. Unlike self-determination (autonomy, competence, relatedness needs;

Noels, 2001), grit focuses on behavioral persistence independent of psychological need satisfaction. Unlike the Ideal L2 Self (aspirational future identity;

Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015), grit concerns tenacity in action rather than identity vision. Empirically,

Lan et al. (

2021) and

Lee (

2022) demonstrate L2 grit’s unique predictive validity beyond these constructs in L2 WTC models, justifying its inclusion as a distinct personality dimension.

Various studies have explored its interplay with learners’ psychological needs and L2 academic achievement (

Elahi Shirvan & Alamer, 2022;

Zhao & Wang, 2023), emotions and personal bests to foreign language learning (

Khajavy & Aghaee, 2024;

Zhao et al., 2024), motivation (

Chen et al., 2021), Ideal L2 self, L2 WTC and shyness (

Lan et al., 2021) enjoyment, L2 WTC, (

E. Liu & Wang, 2021;

Ebn-Abbasi & Nushi, 2022;

Fathi et al., 2023;

Tsang & Lee, 2023). Contemporary research robustly confirms grit’s influence on language learning outcomes.

G. Li (

2024) demonstrated that gritty learners report higher FLE and lower anxiety, fostering better communicative behavior among Chinese learners.

Bai and Hu (

2025) found that FLE predicts L2 WTC through two mediators: L2 grit and academic buoyancy, highlighting the role of grit in complex emotional-motivational processes. In Pakistan,

Fatima (

2024) established that perseverance and emotional stability strongly predict academic success among Lahore University students, providing foundational evidence for extending grit research to L2 communication contexts.

Shahrokhi and Dehaghani (

2025) further showed that grit interacts with self-assessment and motivation to enhance L2 WTC through self-regulated learning mechanisms.

Another dimension of research from positive psychology emphasizes the role of emotions in the learning process, considering both internal and external variables from the learners’ perspective (

Pekrun, 2006;

C. Li, 2022). In this respect, Control Value Theory (CVT) states that other institutional factors, i.e., teacher support (TS), classroom climate, and personal qualities such as Grit, guide the emotions of the learner before they can be determined because they bring changes to the emotional experience during a specific situation (

Almusharraf & Khahro, 2020). Additionally, based on this theory, FLE has been regarded as a positive, high-arousal, activity-emotion (

Pekrun, 2006;

Oxford, 2016;

Mercer & Dörnyei, 2020). Students who are provided with such emotions, e.g., FLE, will be more prone to being activated by persuasive physical tension and to display more vigorous behavioral responses, e.g., L2 WTC. Emotions like FLE can shape learning behaviors by enhancing motivation and willingness to engage in communication. A plethora of research presents a positive correlation in this regard (

Bailey et al., 2021;

Fathi et al., 2023;

Feng et al., 2026;

Alrabai, 2024). Recent structural equation modeling studies increasingly position FLE as central to L2 communication outcomes. As shown by

M. Wang and Wang (

2024), psychological readiness to communicate and enjoyment are positively affected by classroom environments that provide emotional support, and FLE is one of the necessary emotional variables that connect the classroom climate to learning outcomes. Using both variable-centered and person-centered research methods,

Xiao and Jia (

2025) found that emotionally intelligent learners have higher FLE and demonstrate better communicative intentions. In the Pakistani context, an analytical study concluded that increased FLE is a significant predictor of enhanced English proficiency among university students because it lowers anxiety levels and is associated with active engagement (

Khatoon et al., 2024). This was furthered by

John (

2025), who demonstrated how learning under AI assistance boosts motivation, interaction, and confidence, and that technologically mediated support might also promote an enjoyment-based engagement.

The mediator role of FLE, however, varies across contexts. The cross-cultural study by

Bensalem et al. (

2023) revealed that FLE mediation was much stronger in Saudi Arabia than in Morocco, suggesting that cultural and educational variables mediate emotional development.

C. Li (

2022) reported that the impact of FLE depends on proficiency level, with intermediate learners being most affected. The research studies in high-pressure, exam-based situations occasionally indicate attenuating FLE effects in which anxiety overpowers positive emotions (

Teimouri et al., 2019). These ambivalent results highlight the need to investigate the unique educational setting in Pakistan.

This study examines how TS, L2 Grit, and L2 WTC interact, taking into account the interplay among positive institutions, personality traits, and emotions (

Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), with a narrower focus on the influence of FLE. According to previous studies, TS and L2 Grit may foster enjoyment of language learning, which positively influences L2 WTC (

Fathi et al., 2023;

Alrabai, 2024). However, there is limited information on how FLE can mediate such relationships. Though the relationships between TS, L2 Grit, and L2 WTC have been investigated independently in previous research (

Peng & Woodrow, 2010;

Lee, 2022), the interaction between these variables and FLE, a positive emotional state with motivation and engagement in L2 learning (

Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014) has not been discovered in this situation as a limited number of studies (

Yang et al., 2024) are available in this situation.

1.2. Motivation for the Present Study

English is used as both a second and a foreign language in Pakistan, as the nation is multilingual and faces socioeconomic stratification (

Rahman, 2001;

Haidar, 2017) and problems with instructional practices (

Manan, 2018). Nevertheless, the students have strong instrumental motivation despite these challenges, and they consider English a key to socioeconomic self-improvement (

Khalid, 2016;

Rashid & Malik, 2025). This instrumental drive is accompanied by a powerful sense of national identity associated with the Urdu language, reflecting a moderate bilingual strategy.

L2 WTC among Pakistani English language learners is studied from the perspective of contextual preferences (

Bukhari et al., 2015;

Ali, 2017), sociocultural influences (

Ubaid et al., 2022, factors affecting L2 WTC such as motivation, self-perceived communicative competence, language anxiety in educational contexts (

Ghani & Azhar, 2017;

Imran & Ghani, 2014) and familiarity with interlocutors and context (

Ali, 2017). Recent Pakistani scholarship has begun to address the complexity of L2 WTC. According to

Sarwari (

2024), L2 WTC is strongly linked to English achievement, as the study found that oral and written performance is more likely to be better with higher L2 WTC scores.

Ubaid et al. (

2025) found that instrumental and integrative motivation complement L2 WTC and that classroom experiences mediate the effect.

Razzaq and Hamzah (

2024) showed that metacognitive strategic awareness and communicative confidence were strongly associated, indicating cognitive-emotional interactions. Nonetheless, these studies analyze variables in relative isolation, without systematically integrating positive psychology constructs. The interaction of positive institutions in the context of positive psychology (

Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) means that positive environmental structures (TS), including academic, emotional, and instrumental aspects, interact with positive personality traits (L2 grit) and positive emotions (FLE) to predict learning outcomes. This interaction of three represents the main assumption of positive psychology in the context of education.

Nevertheless, despite growing recognition of TS’s mediating mechanisms (

Yang et al., 2024;

Habib et al., 2025), grit’s emotional pathways (

G. Li, 2024;

Bai & Hu, 2025), and FLE’s central role (

M. Wang & Wang, 2024;

Xiao & Jia, 2025), and emerging Pakistani L2 WTC research (

Sarwari, 2024;

Ubaid et al., 2025;

Khatoon et al., 2024), no study has systematically examined how TS, L2 grit, and FLE interact within an integrated positive psychology framework to shape L2 WTC among Pakistani university learners. Recent work has advanced understanding of individual constructs or examined paired relationships (e.g., (

Fatima, 2024), on grit; (

Habib et al., 2025), on FLE), but the complete mediational architecture—whereby institutional support and personal resilience translate into communicative willingness through emotional enjoyment—remains unexplored in Pakistan’s unique multilingual, socioeconomically stratified educational environment. This research fills this crucial gap by providing an empirically validated, theoretically based structural model that incorporates all three pillars of positive psychology.

To justify the choice of the TS, L2 grit, and FLE as the focus constructs, the three-pillar framework of positive psychology (

Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) was used, which assumes that well-being is a result of the interplay between positive institutions (TS), positive personality traits (L2 grit), and positive emotions (FLE). Empirically, these variables represent modifiable factors within educators’ control, making findings actionable in resource-constrained Pakistani EFL/ESL contexts. Recent scholarship (

Yang et al., 2024;

Bai & Hu, 2025;

G. Li, 2024) demonstrates their growing centrality to L2 WTC research, yet their integrated mediational architecture remains unexplored in multilingual South Asian contexts.

Research Questions and Objectives

To achieve this end, the following research questions are posed:

Does TS directly predict L2 WTC?

Does L2 Grit directly predict L2 WTC?

Does FLE mediate the relationship between TS, L2 Grit, and L2 WTC?

Answering the above research questions, the study will help fill the gap in the number of positive psychology studies in second language learning (SLA) and offer practical EFL/ESL pedagogical implications. Understanding the emotional and psychological mechanisms behind L2 WTC can help educators develop strategies to foster a more engaging and communicative learning environment, ultimately improving learners’ language outcomes.

1.3. Theoretical Framework

The study is based on the pyramid model of L2 WTC by

MacIntyre et al. (

1998) and principles of positive psychology (

Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Although we agree with

Henry and MacIntyre (

2023) that the 3D model should focus on dynamic and temporal interactions, the nature of our cross-sectional design prevents us from capturing them. Alternatively, the current study confirms their demand for combined frameworks that can investigate several L2 WTC antecedents simultaneously and experiment with the relationships among environmental factors (TS), stable traits (L2 grit), and dynamic emotions (FLE) in the Pakistani context. Instead of operationalizing the entire 3D model, we provide contextual replication and structural model testing that help us realize these relationships in a multilingual, underrepresented environment. The main argument of this study is that TS and L2 Grit are related to L2 WTC, although FLE mediates their effects. The sub-claims are:

TS alone does not directly predict L2 WTC, but it does predict FLE.

L2 Grit directly predicts L2 WTC and is positively associated with FLE.

FLE serves as a crucial emotional factor that connects TS and L2 Grit to L2 WTC.

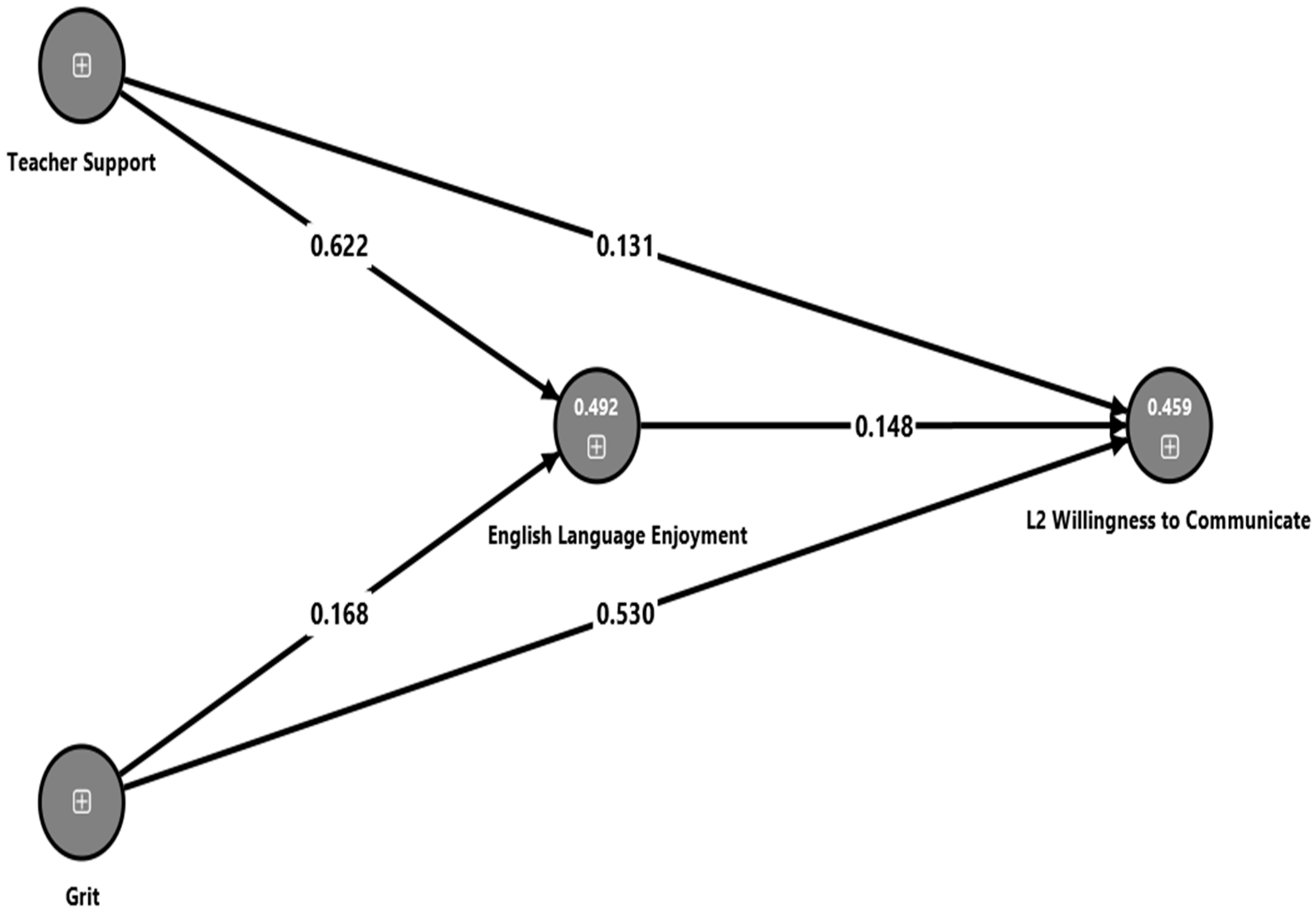

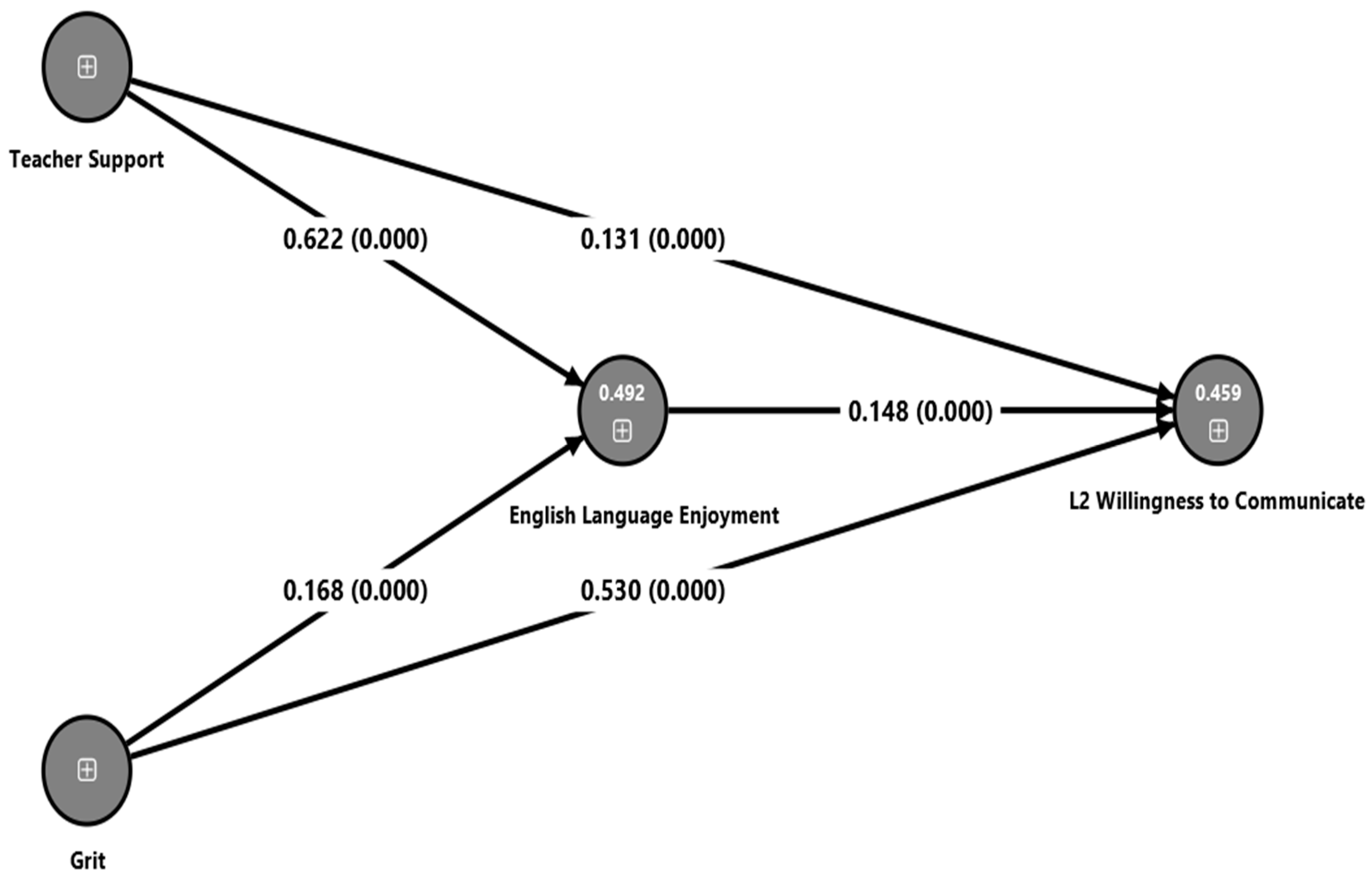

A conceptual framework is proposed to illustrate the relationships among the variables in

Figure 2. A solid line depicts the significant relationship between the variables.

Perceived TS → L2 Grit (H1)

L2 Grit → L2 WTC (WTC) (H2)

Perceived TS → FLE (FLE) (H3)

FLE (FLE) → L2 WTC (H4)

Perceived TS → FLE → L2 WTC (H5, mediation)

L2 Grit → FLE → L2 WTC (H6, mediation)