Abstract

Education is embedded within a complex societal ecosystem that attempts to imbue students with the cultural norms and values of the society in which it operates. Neoliberalism ideology has been shaping education systems, policies and reforms in Australia and many other countries, since the early 1980s. Arguably, there are both benefits and challenges related to neoliberal education. For example, neoliberals advocate for education systems to be run according to free market principles, that elements of education should be privatised endogenously and exogenously, that parents/guardians and students should have more agency and that top-down management should be increased through surveillance and mandated performance. This paper addresses the last point that increased teacher accountability measures and the standardisation of student learning outcomes have resulted in the de-professionalisation of teaching. Using case study research, five expert teachers’ experiences of using action research to explore and challenge their pedagogy is investigated. Perceptions about teacher autonomy and the de-professionalism of teaching emerged as the overarching research aim inquired whether action research can be used as a response to the declining status of the teaching profession. Findings suggest that through action research, teachers can be empowered to enhance their pedagogy, while developing meaningful and contextually relevant evidence-based practice.

1. Introduction

Education is embedded within a complex societal ecosystem with the primary purpose of developing young peoples’ academic learning, and personal and social development. It is within this context that the cultural norms and values of the society in which an education system operates is imbued on students through the policies that drive educational agendas that in turn have implications on curriculum content, modes of delivery, resources and budget allocation and how quality is considered and measured. It is through this lens that it can be understood that neoliberalism ideology has been shaping education systems, policies and reforms in Australia, Britain and many other countries, since the early 1980s (Ball, 2016, 2000). Neoliberalism in education is most simply described as the commodification of access to education, wherein students are considered customers or consumers of a service (Connell, 2013). Arguably, there are both benefits and challenges related to neoliberal education. For example, neoliberals advocate for education systems to be run according to free market principles, that elements of education should be privatised endogenously and exogenously, that parents/guardians and students should have more agency and that top-down management through surveillance and mandated performance should be increased. This paper addresses the last point that increased teacher accountability measures and the standardisation of student learning outcomes have resulted in the de-professionalisation of teaching.

The declining status of the teaching profession has been in crisis for a number of years and this can largely be attributed to the de-professionalisation of teaching and teachers (R. Buchanan, 2015; J. Buchanan, 2020). To understand what the de-professionalisation of teaching and teachers means in education, it is important to firstly consider what professionalisation is in this context. Despite the many definitions of professionalism, the term most commonly refers to the quality or value of people’s actions within an occupational group and the roles and function(s) that they have in society (Hargreaves, 2000). Professionalisation can be further articulated as the strategies utilised by individuals or a group of workers to advocate and advance their debate for professional recognition or status (Hargreaves & Goodson, 2002; Whitty, 2000). Professional status then is best described as a culmination of position and social standing as given to a profession by society for its perceived value (Crossman, 2005; Hoyle, 2001). Unfortunately, research indicates that teaching as a profession continues to be plagued by ambiguity and considered lower in status than other professions that have required a university level qualification (Allen et al., 2019; Dumay & Burn, 2022). Several studies exploring the status of teaching and teaching as a profession more widely (Allen et al., 2019; Darling-Hammond et al., 1995; Dumay & Burn, 2022; Fuller et al., 2013; O’Donnell, 2000; Praetorius & Charalambous, 2023; Rowan, 1994; Verhoeven et al., 2006) have found at least one, if not all, of the following three primary factors to be of import in the classification of professionalisation: prestige (comparative ranking to other occupations), status (the knowledge required by the profession in comparison to others) and esteem (how society perceives its value and, in turn, function in the societal ecosystem) (Hoyle, 2001; Dumay & Burn, 2022). Within education, the professional status of teachers and teaching is inextricably linked to issues of quality. As a result, measurements for teacher performance and the accountability of student learning outcomes have become significant neoliberal factors placing stress on the profession and the way it is perceived.

Concerningly, forms of quantifiable standardised testing and assessment continue to be considered the gold standard for measuring quality education internationally (Crawford & Tan, 2019). Consequently, such performance-based assessments have also been used as a tool for measuring teacher performance (Lavy, 2007; Lewis & Young, 2013; Morris, 2011). A number of strategies for increasing student learning outcomes and achievement have been implemented around the world, such as increasing or in some cases decreasing the entrance requirement for pre-service teachers seeking an undergraduate or graduate teaching degree, increasing financial remuneration, providing more appealing working conditions, possibilities of paid professional experience and increasing some of the authority that teachers in the profession have over their work environment (Lewis & Young, 2013; Lankford et al., 2014).

Similarly, in Australia, the latest federal government education review (DET, 2018) aims to improve evidence-based decision-making in Australian school education. A key component of this review recognises that the Australian government’s educational investment must be guided by rigorous evidence and on par with other professional sectors that consider what works, for whom and in what contexts. Over the past two decades, the Australian educational landscape has evolved rapidly. Most notably, have been the changes surrounding teacher registration and the introduction of formalised teacher standards that are regulated by a national governing body that informs initial teacher education programs and accreditation. The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) is a federal organisation that was developed in 2011 and tasked with promoting excellence in teaching with the primary purpose of maximising student achievement and engagement (AITSL, 2018). The literature has suggested that as governments and regulatory authorities aim to increase quality, so too are the demands of the profession, culminating in an increase in professional status as perceived by society (Fisch, 2009; Fuller et al., 2013; Klenowski, 2012; Praetorius & Charalambous, 2023). However, also asserted by literature is the increasing trend of the opposite effect, where a targeted focus on performance standards and accountability can remove important elements, such as autonomy and responsibility (Dumay & Burn, 2022; Fisch, 2009; Fuller et al., 2013; Klenowski, 2012; Praetorius & Charalambous, 2023). These elements are critical as they constitute what a profession is and if taken away through the required implementation of rigid standards to be adhered to, this will result in the professional status of teachers and teaching being diminished (Fuller et al., 2013).

Traditionally, ideas of professionalism have focused on establishing professional standards that define or categorise an occupation as a profession (Wyatt-Smith & Looney, 2016). The use of professional standards to define an occupation is reflected in professions, such as medicine and law, that have historically maintained high professional standing in society and, in turn, a consistently strong professional status. Therefore, to be recognised as a profession, an occupation must require not only a specialised skill set, but importantly, a substantive body of knowledge. Similarly, to medicine or law, this includes a shared technical knowledge and culture, ethical standards in the form of a code of professional conduct committed to high quality and client/consumer’s needs, and a strong professional organisation that includes self-regulation, rather than external bureaucratic control (Alexander et al., 2019; Hargreaves, 2000; Whitty, 2000). In this knowledge-based and client-focused concept of professionalism, individuals in the occupation are autonomous to make the best decisions for their clients, irrespective of what might be considered easiest or in fact what the client(s) might want (Alexander et al., 2019; Darling-Hammond et al., 1995). Within this concept of professionalism, autonomy is central to the process of elevating its processional status. This is based on three assumptions that autonomous professionals use to distinguish themselves from others, because they (i) are concerned with the promotion of human well-being, (ii) rely on highly specialised knowledge and skills, and (iii) work from a position of authority that establishes a relationship of trust (Biesta, 2017). This perspective of professionalism has been used to measure the professional status of teachers and in turn measured by these professional standards, which has resulted in teachers’ work and teaching being frequently categorised as a semi-profession (Whitty, 2000).

Unfortunately, the complex nature of teachers’ work is constantly misunderstood by society. Consequently, due to the diversity of pedagogical approaches and practices, teachers are often required to use across a range of educational contexts, which means that they are repeatedly regarded as lacking technical expertise or a shared technical knowledge and culture (Alexander et al., 2019). Teachers are therefore often not seen to be in a position of authority, to have autonomy or to have codes of self-regulation, and are being controlled by external bureaucratic demands (Alexander et al., 2019; J. Buchanan, 2020; Whitty, 2000). However, attempts to address these claims about the teaching profession can be found in studies that explore and try to define and categorise teachers’ knowledge (Alexander et al., 2019; Biesta, 2017; Day, 2002; Hill & Chin, 2018; Loewenberg et al., 2008; Shulman, 1986, 1987). Such literature is an example of the studies that contribute to the crusade for the recognition of the professional status of teachers and teaching and or as a resistance to performance-based measure and notions often associated with evidence-based practice. From this perspective, an established expert knowledge-based and specialised skill set for teaching intends to replace the performance-based standards dictated by this traditional view of professionalism.

Research that endeavours to distinguish teacher’s knowledge as a specific expert form of knowledge can be particularly attributed to Shulman (1986, 1987) who classifies the elements of teaching knowledge into seven typologies: content knowledge, general pedagogical knowledge (including principles and strategies of classroom management and organisation), curriculum knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge (expert amalgam of content and pedagogy that uniquely requires teachers’ professional understanding and experience), knowledge of learners and their characteristics, knowledge of educational contexts (including the workings of the group/classroom, the governance and financing, the character of communities and cultures) and knowledge of educational ends (aims, purposes and values that include philosophical and historical perspectives) (1987). Pedagogical content knowledge is the typology of teaching knowledge “most likely to distinguish the understanding of the content specialist from that of the pedagogue” (Shulman, 1987, p. 8). Shulman advocates for professional reform and bases arguments on the belief that there exists a ‘knowledge base for teaching’—“a codified or codifiable aggregation of knowledge, skill, understanding, and technology, of ethics and disposition, of collective responsibility—as well as a means for representing and communicating it” (Shulman, 1987, p. 4).

The wisdom of practice is considered the final source of the knowledge base and, in turn, the least able to be defined or codified. Such wisdom of practice contains the maxims that guide (or provide reflective rationalisation/pedagogical reasoning) the practices of expert teachers (Shulman, 1987). Shulman asserts that “One of the more important tasks for the research community is to work with practitioners to develop codified representations of the practical pedagogical wisdom of such teachers” (Shulman, 1987, p. 11). This conception of professionalisation attempts to develop the potential for empirical research and a scientific foundation for the teaching profession (Darling-Hammond et al., 1995; Hargreaves & Goodson, 2002). While trying to define professionalisation in this context can be problematic because of the complex nature of teachers’ work, Shulman provides a basis from which to consider expert teachers’ knowledge as a way to reclaim teacher autonomy, to provide recognition of its professional value and as a way to meaningfully understand what makes quality education and educators. It should also be recognised that teachers’ work cannot be generalised and is highly contextualised and situated, so there will likely be multiple ways in which teachers’ knowledge is enacted.

Teachers’ experiences of educational contexts and situations are central to understanding teachers’ knowledge. The practical knowledge of teachers encompasses situated knowledge about curriculum, practices, classrooms, school environment, and teachers’ lives (Clandinin & Connelly, 1986). Therefore, teacher professionalism must also incorporate notions of practical and context-oriented knowledge and judgment (Clandinin & Connelly, 1986; Hargreaves & Goodson, 2002). A sense of professional community can be developed collaboratively through establishing technical expertise and a shared technical knowledge and culture. Through communities of practice, teachers’ application of expert, situated and practical knowledge (Clandinin & Connelly, 1986; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Shulman, 1987) is disseminated, engaging teachers in the process of professionalisation, which in turn enhances teacher professionalism (Ball, 2003). Teaching practices are based on norms that are socially mediated and negotiated within everyday education contexts, and teacher professionalism is reliant upon localised parameters and context-specific determinants that characterise the local teacher community from which different shared technical knowledge and cultures will emerge. These should be viewed as having legitimate alternative educational goals and prescriptions for situated and context-specific teaching practices that may or may not be applicable beyond a particular educational setting. Within these communities of practice contexts (Lave & Wenger, 1991), teachers mediate their professional identity and determine themselves what defines the norms of the profession through developed expert teachers’ knowledge and collegial interactions in the exchange of this shared knowledge (Ferreira, 2022). This requires a recognition that teacher professionalism is diverse, variable and contingent. A multidimensional approach using multiple contextual lenses, such as organisational, institutional and social systems, is critical when attempting to understand the nature of teacher professionalism.

Teaching, which can be described as an incredibly complex and difficult job that when done well, is made to look easy (Labaree, 2000), is perhaps why it has been excluded from the professions and in some ways devalued from a societal perspective (J. Buchanan, 2020). Shulman describes teaching as “perhaps the most complex, most challenging, and most demanding, subtle, nuanced, and frightening activity that our species has ever invented” (Shulman, 2004, p. 504). Within the contemporary neoliberal landscape, one starts to question how to respond to the de-professionalisation of teaching, particularly given that teachers’ work is one of the most highly complex and at times unpredictable pursuits there is. In this era of measurement, Oscar Wilde’s famous contention that people know the price of everything, but the value of nothing (Loewenberg et al., 2008), although cynical, seems to aptly capture the issues discussed related to the de-professionalisation of teachers and teaching, and what should constitute evidence-based practice. The significance of the research presented in this article is that it provides an evidence-based practice example that demonstrates how teachers can use research to enhance their pedagogy and in doing so, respond to the de-professionalisation of teaching. Using case study research, five expert teachers’ experiences of using action research to explore and challenge their pedagogy is investigated. Perceptions about teacher autonomy and the de-professionalism of teaching emerged as the overarching research aim inquired whether action research can be used as a response to the declining status of the teaching profession. Findings suggest that through action research, teachers can be empowered to enhance their pedagogy, while developing meaningful and contextually relevant evidence-based practice, resisting de-professionalisation.

It is important to acknowledge that countries may vary in the extent to which they allow for teacher professionalism with variation in their status and autonomy over the work. Cases where the teaching profession is mandated by professional standards, could suggest that the profession is highly governed and controlled. One might think that this would make any initiative such as action research limited in potential impact on enhancing the status or professional nature of the occupation. However, in contexts such as Australia where teachers are being asked to provide ongoing evidence of their effectiveness, it has been identified that action research can be a useful tool in fulfilling both mandated requirements and to empower teachers to use this evidence to improve practice through autonomous decision-making about teaching and learning, reclaiming their professional status.

2. Materials and Methods

Before detailing the research methods used to conduct this current study, it is important to provide a brief introduction to action research as it is the research method that the expert teacher participants used to better understand their pedagogy.

2.1. Expert Teacher Research Method—Understanding Pedagogy Through Action Research

While action research has a long tradition in education, the contemporary discourse around evidence-based practice has instigated a resurgence about the value of such an approach for developing critically reflective practitioners (Crawford, 2022a). The expert teachers in this study used Crawford’s action research (AR) model with embedded peer observation as a way to understand, interpret and analyse the complex and multifaceted issues presented in a localised or context-specific environment that uses a systematic and rigorous research frame that may allow for the findings to be applied to a wider context or other similar educational settings (Crawford, 2019a, 2022a). This creates opportunities for replicating such research, potentially enhancing its contribution to the advancement of the profession. Unlike other research methodologies, AR operates on the principle that local conditions vary significantly. Therefore, solutions to complex educational problems cannot be derived from generalised facts that disregard these local nuances, highlighting the limitations of standardised measures.

It is widely accepted that AR was first coined by Kurt Lewin in his 1946 paper, Action Research and Minority Problems, in which he highlighted research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action (Lewin, 1946). In its basic form, AR requires teachers to investigate the result of an action through a cyclical spiral of steps, in which each cycle includes planning, action and fact-finding. However, a more sophisticated understanding of the process of AR emerged with Stenhouse’s (1975) introduction of the ‘teacher-as-researcher’ concept that placed emphasis on the value of critical reflection as a professional endeavour (Crawford, 2022a). Being a reflective practitioner is crucial for effective teaching and the ongoing professional learning and development of educators. Reflection in AR is an intentional process and a fundamental aspect of the methodology. It is defined by a cyclical approach that is planned, systematic, iterative, and critical. This process alternates between action and reflection, continuously refining methods and interpretations based on understanding, insights and new knowledge gained from previous cycles (Crawford, 2019a; Mertler, 2009).

Although action research often centres on individual practice, it has the potential to significantly enhance educational outcomes on a broader scale by fostering collaborative change with the shared objective of improving practice (Crawford, 2019a, 2022a) as observed in this research. One particular benefit for using AR is that educators can directly access the findings from their research endeavours, enabling them to implement immediate changes through the process of systematic critical reflection. Finally, AR is conducted by the educator to benefit both the teacher and their learners. The findings, in turn, lead to actions or changes implemented by the teacher that are justifiable, credible and authentic (Crawford, 2019a; Kennedy-Clark et al., 2018). AR has been known to be used as a means “to formally or informally determine the impact of pedagogy on student learning, develop curriculum and program initiatives and respond to education policy and school reform” (Crawford, 2022a, p. 58).

Using AR as a tool for teachers to better understand their pedagogy will allow for the exploration of whether AR would change the values and belief of teachers, lead to more effective teaching and learning and impact the status of the profession. On the other side of this exploration is whether AR can only address certain conditions of professionalism. Given the emphasis on the declining status of teachers, it is not suggested that the AR of a small number of teachers can change this complex and wide-reaching issue. However, there is value in considering its use for providing a form of contextually relevant evidence-based practice, providing teachers with autonomy over their work, and unintended consequences, such as when the status and value of research as a discipline would see a devaluation as a result.

2.2. Research Aims and Research Questons

The overarching research aim for this study inquired whether action research can be used as a response to the declining status of the teaching profession through the development of evidence-based practice research. Aligning with previous research studies (Crawford, 2019a, 2022a), this research explored the extent to which AR can be used to develop an evidence-based practice by examining the techniques, strategies, behaviours and attitudes involved in teachers’ professional actions and decision-making.

The following overarching question was designed based on the primary aim: To what extent can action research be valued as evidence-based practice and mitigate the perceived de-professionalisation of teaching?

The second research question was designed to consider how action research could potentially challenge neoliberal understandings of the value placed on traditional forms of evidence-based practice through determining if AR could enhance pedagogy: To what extent can action research enhance pedagogy?

2.3. Case Study

Given this study investigated teacher experts engaging with action research within a particular educational context, the exploratory nature of qualitative research was considered most appropriate. According to Creswell and Guetterman (2019), qualitative research by its very nature allows a researcher to conduct an in-depth investigation of unknown variables relating to a specific subject or group of people previously unstudied. This helps to develop an understanding of the phenomena in question by using data collected from first-hand participant experiences. By involving a diverse range of participants, the study can explore various perspectives on the topic, using their experiences and the meanings they construct as the basis for evidence and interpretation. To facilitate this, an embedded case study design was adopted and semi-structured interviews, classroom observations, teacher research journals and lesson plans and teaching materials were used as methods to gather data (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2014) related to the individual experience of using AR to enhance pedagogy and respond to the de-professionalisation of teaching. Case study design, participants and related data collection methods relevant to this paper are discussed in turn within the Materials and Methods section.

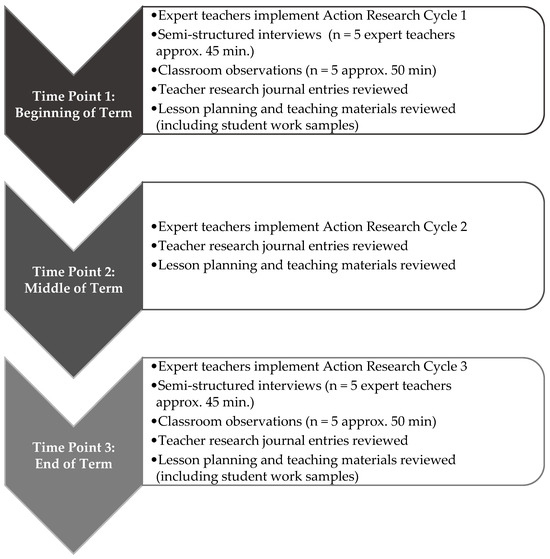

Case study research offers a framework for the detailed description and analysis of a specific phenomenon within real-life contexts, where the causal relationships between variables are not yet understood (Stake, 1995; Yin, 2014). Multiple sources of data are collected to create an accurate and detailed picture of the case in question, focusing on answering research questions that aim to identify various variables of interest (Lucas et al., 2018; Yin, 2014). Similar to action research, although generalisability is not the primary goal of case study research, the conclusions drawn from a case can have broader applications within a field with results placing emphasis on analytical and theoretical generalisation rather than statistical generalisation (Grauer & Klein, 2012; Merriam & Tisdell, 2015) about teaching practice in this specific case. An embedded case study concentrates on a single case, defined by its context, and represents the phenomenon of interest. However, within the case, multiple subsets can be identified for further investigation, each offering a unique influence or variation on the phenomenon (Lucas et al., 2018; Merriam & Tisdell, 2015; Yin, 2014). For this reason, embedded case studies are at times confused with multiple-case study designs, while both examine a range of subsets from one particular case, the subsets within an embedded study share the same context and binding variables (Lucas et al., 2018; Merriam & Tisdell, 2015; Yin, 2014). This research adopted an embedded case study design to collect multiple perspectives on the phenomena that considered to what extent AR could enhance pedagogy and if so, could this challenge neoliberal ideas of what evidence-based practice could be. The case study was conducted at one school, which is considered a high performing government (public) school in the state of Victoria, Australia. The time frame for work with the expert teachers within the case study constituted one school term (10 weeks). Figure 1 outlines the overall case study design and time points for data collection across the project:

Figure 1.

Case study design.

2.4. Particpants

This study investigated the experiences of 5 expert teachers using action research to explore and challenge their pedagogy. These teachers are regarded as ‘expert teachers’, also known as ‘leading teachers’ according to the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APSTs) set by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL, 2018). The standards and teacher levels of proficiency are public statements of what AITSL constitutes teacher quality and defines the work of teachers through making explicit the elements and expectations of “high-quality, effective teaching in 21st century schools that will improve educational outcomes for students” (AITSL, 2018). The teachers in this study are considered experts not only because of the years in which they have been teaching (ranging from 10–30 years), but for the following key reasons:

- High motivation to develop their practice to improve their students’ learning and engagement;

- Expressed willingness to conduct research and better understand how data can be used for teaching and learning;

- Interest in Stenhouse (1975)’s ‘teacher-as-researcher’ concept that placed emphasis on the value of critical reflection as a professional endeavour;

- Interest in the application of the Victorian state Department of Education and Training High Impact Teaching Strategies (HITS) outlined in Frameworks for Improving Student Outcomes (FISO) (DET, 2020);

- Identified as a team leader;

- Regularly mentor student teachers on professional experience/placement at the school.

The 5 expert teachers who volunteered to be part of this research are situated in the same school and represent each of the primary school grades from foundation/prep to grade 6 as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Expert teachers approximate years of teaching and grade level.

Although from different grade levels, the teachers had the same aims, to use AR to accomplish the following:

- Increase professional efficacy and capacity in the explicit teaching of thinking skills, including metacognitive processes (one of the HITS) and research the impact;

- To explore student engagement and learning outcomes as a result of increased metacognitive strategies.

The focus for these expert teachers was firmly on increasing student engagement and improving learning outcomes through the development of teacher instructional practice in building metacognitive strategies.

2.5. Instruments for Collecting Data—A Focus on the Final Semi-Structured Inteview

Semi-structured interviews, classroom observations, research teacher journals, and lesson planning and teaching materials (including student work samples) were used in the overall research project. For the purpose of this paper, data from the final semi-structured interviews will be used as the data from this instrument and time point was most illuminating in addressing the research questions and in turn will be discussed in this section.

The final semi-structured interviews were conducted with each of the 5 expert teachers at the end of the school term and were approximately 45 min in length. These were guided by an interview protocol, comprising 12 open-ended conversational prompts and questions, that supported the expert teacher in their exploration and explanation of their perceptions and experiences (Ahlin, 2019; Brown & Danaher, 2019) related to pedagogy, using AR and its potential value and the nature of evidenced-based practice:

- Can you describe your teacher philosophy/the type of teacher you consider yourself to be or what that might mean to someone observing from the outside looking in?

- If you had to give advice to a student-teacher or graduate teacher about what teachers’ work involves, what would you say?

- What terms would you use to describe your pedagogy?

- Can you summarise which elements of pedagogy are important to you and why?

- How is this (question 3 and 4) encompassed in your pedagogy? Can you elaborate/provide an example(s)?

- How would you describe or explain action research to someone who has never used it before (explore experiences, application in practice and whether teachers can draw from examples to illustrate thinking and understanding)?

- Depending on response to question 6—positive experience with AR—what strategy would you use to encourage colleagues to implement AR in their classrooms? Neutral experience with AR—if you were conducting a professional development session, how would you describe the benefits and challenges? Would you recommend action research to other teachers?

- After implementing AR in your own classroom, are you more confident with the idea of using research and data for teaching and learning? (On a scale of 1 being not at all confident to 10 really confident.)

- Do you feel that undertaking an action research project impacted/improved your practice?

- How did your experience of being in charge of your own professional learning impact or affect you? (Explore the nature of teachers’ knowledge and expert teachers’ knowledge as a way to reclaim teacher autonomy.)

- What are your views on evidence-based practice and how have they changed, if at all, from the beginning of the term? (Explore teacher-as-researcher concept.)

- What are your views on implementing AR more widely throughout the educational system? How do you think this would be received by your peers and colleagues?

This purposeful conversational style to conducting semi-structured interviews provided an informal approach that enabled these expert teachers the freedom to discuss key issues of importance to them (Ahlin, 2019; Denscombe, 2014). These questions and prompts were designed to address the primary aim of the study to explore the extent that action research may be valued as evidence-based practice through enhancing pedagogy and in turn mitigate the perceived de-professionalisation of teaching.

2.6. Analysis of the Final Semi-Structured Interview Data

In this case study, qualitative data and in particular the semi-structured interview data, were analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) and thematic analysis techniques (Spiers & Riley, 2019). IPA is adaptable to various research contexts and questions, making it a versatile tool in qualitative research. The goal of IPA is to thoroughly examine personal meaning and lived experiences. Grounded in phenomenological philosophy, hermeneutics, and idiography, IPA enables researchers to conduct an in-depth exploration of how participants derive meaning from their personal and social environments (Crawford, 2019b). IPA is typically carried out on small sample sizes because the process demands meticulous attention to detail, is iterative by its very nature and, in turn, is time consuming (Smith & Osborn, 2015). It offers researchers an insider perspective on participants’ worlds by engaging in an idiographic exploration of their meaning constructs, while recognising the impact of personal, social and culturally mediated factors (Crawford, 2019b). While there are various approaches to conducting an IPA analysis, this case study employs a data reduction method that involves identifying patterns and key themes through the following steps: transcription, reading and re-reading, initial coding, abstraction coding and interpretation (Crawford, 2019b). The themes highlight both convergence and divergence, as well as commonality and nuance, which is aligned with other research studies that may utilise such an analysis approach (Crawford, 2019b; Smith & Osborn, 2015; Spiers & Riley, 2019). IPA’s emphasis on detailed, idiographic exploration makes it a valuable method for understanding the intricacies of human experience, in this case, expert teachers engaging with AR for teaching and learning.

2.7. Ethics

The principal of the school where the research was conducted was approached via official written correspondence following ethical approval from the Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and the Department of Education. The school was identified as being a high performing school through publicly available data reporting on student learning performance, context and demographics. It was decided that a school with such a profile may, in turn, value the research aims of this project. The principal was highly receptive and immediately expressed seeing the benefits in participating, particularly as the teachers would gain further learning and understanding of their pedagogical development. The researcher later learned that the principal not only found this to be an important part of teachers’ work, but was deeply passionate and committed to developing and providing opportunities for their teaching team to engage with. In accordance with ethical guidelines, pseudonyms for research participants are used and any information that may potentially identify the school have been masked. Informed consent was obtained from all research participants involved in this project. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The researcher is a highly experienced educator and teacher educator who specialises in the development of teaching and learning models, curriculum and pedagogy and the application of research as a form of evidence-based practice. Crawford has also used IPA extensively in their research and is therefore well positioned to conduct and report on the findings of this research.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, results from the final semi-structured interview are presented thematically with accompanying illustrative exemplars. Four primary themes were identified from the data and, in turn, form the basis for how the findings are presented:

- Teaching philosophy and identity guides the professional work of teachers.

- The importance of pedagogy and its central role in the professional work of teachers.

- Action research enhanced pedagogy, but this is not without challenges.

- Redefining evidence-based practice and reclaiming teacher autonomy.

Given the descriptive nature of these results, the interpretation and discussion are weaved through to guide understanding.

Results were quite positive in relation to the teachers finding value with engaging in action research for teaching and learning. One could suggest that positive results may not come as a surprise when conducting research in a high performing school with highly motivated and committed teachers. However, what is evident in the findings is the high level to which the teachers engaged with critically reflective practice and as a result regaining the autonomy of their professional learning and work as they felt empowered by the action research process. Finally, one of the most poignant revelations, was that the data collected in practice for practice was regarded as meaningful and highly relevant. The findings from the research that the expert teachers conducted indicated that they had achieved the aims of enhancing pedagogy (explicit teaching of thinking skills, including metacognitive processes—HITS) and increased student learning outcomes and engagement using metacognitive strategies.

3.1. Teaching Philosophy and Identity Guides the Professional Work of Teachers

Teaching philosophy, the type of teacher research participants considered themselves to be and how this may relate to key elements of their pedagogy were guided by questions 1 to 5. Findings suggested that many of the key issues highlighted and regarded as important by these expert teachers also encompassed their professional identity and in turn guided their work as teachers. A teaching philosophy is essentially a set of beliefs and values concerning the practice of teaching and the process of learning (Murphy, 2023). Key education principles are stated and a rationale for each is provided with practical examples to illustrate and support beliefs. Although specific beliefs and values are unique to each teacher, they share common elements as demonstrated in Table 2, which provides a summary of teaching philosophies and the types of teaching and learning valued.

Table 2.

Summary of quoted teaching philosophies from final semi-structured interview.

While there are a number of reasons for a teacher to think about their teaching philosophy, it was used for two reasons in this case study. The first was as an opportunity for professional learning and development through reflection and recounting experiences. Expert teachers considered the following key questions that encompass their teaching philosophy: Why do I teach? What do I teach? How do I teach? How do I measure my own effectiveness? (Bowne, 2017). The second reason was as a way to gain insight into the teachers’ beliefs and values about teaching and learning and understand how these ideas might be supported in practice in the classroom. Opportunities to engage in the scholarship of teaching and learning (Boyer, 1991; Yeo et al., 2024) move beyond neoliberal notions of measurement and accountability, instead having a profound impact on the development of teacher practice. This was particularly true for the research participants who exhibited attributes similar to other studies (Murphy, 2023; Pelger & Larsson, 2018; Yeo et al., 2024) demonstrating a higher level of self-awareness of their role as educator, articulated an understanding of successful practices in their classroom, drew inspiration from literature on teaching and saw a higher value in contextually relevant evidence-based practice that enhanced pedagogy through action research. The responses in Table 2 make clear that teaching is not only a highly complex, situated and active endeavour, but that quality teaching cannot be reduced to simply technique or content knowledge, instead it is derived in part from the identity and integrity of the teacher (Palmer, 2017). “Teaching is by its nature an uncertain endeavor with no identifiable ‘answers’ … knowledge is elusive…teachers develop not through the acquisition of best practices but through cultivating dispositions that are responsive to this uncertainty” (Wahl, 2017, pp. 510–511). All five expert teachers linked their teaching philosophy to their professional identity in some way. This seemed to be either a driving factor that guided teachers’ pedagogy and professional work or has evolved into a reciprocal relationship between these factors.

3.2. The Importance of Pedagogy and Its Central Role in the Professional Work of Teachers

The five expert teachers discussed how pedagogy is a key component of the work of teachers, which were guided by questions 2 to 5. Each of the five expert teachers identified the ever growing list of tasks that are expected of teachers: planning and preparation (curriculum alignment, lesson design and resources development), instruction and delivery (including using a range of teaching strategies for differentiated learning, classroom management and behaviour management), assessment and feedback, student support (including individualised instruction, special needs and mentoring and counselling), professional learning/development (individually and collaboratively with peers), administrative duties (including record keeping, communication with parents/guardians through meetings, emails and reports to discuss student progress and address concerns), leading or supporting extracurricular activities and school events and organising and supervising educational or team building/wellbeing excursions/field trips and other out-of-classroom learning experiences. These tasks highlight the multifaceted nature of teachers’ work, demonstrating that teachers play a crucial role in shaping the educational experiences and overall development of their students (Crawford, 2022b). While teachers acknowledged the extent of what they do, they viewed pedagogy as central to their work and what gives their role professional status. Table 3 provides illustrative quotes from participants that demonstrate the importance of pedagogy in their work.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes demonstrating the importance of pedagogy.

Findings suggested that teachers were acutely aware that pedagogy is not just about the methods they use, but about the underlying principles and beliefs that shape their teaching practices. It was clear that such critical understanding enabled them to create effective and meaningful learning experiences for their students. Correlating with other studies (Entz, 2007; Loughran, 2013; Madalinska-Michalak, 2022), the data also highlight a perceived link between the importance of pedagogy and teachers’ professional identity.

3.3. Action Research Enhanced Pedagogy, but This Is Not Without Challenges

Although drawing from slightly different frames for approaching teaching and learning, each of the five expert teachers expressed that the aims for their AR projects were achieved and that this professional learning opportunity enhanced their pedagogy. In this regard, participants felt that AR had increased their professional efficacy and capacity in the explicit teaching of thinking skills (metacognitive processes) for which they were able to research the impact to understand student engagement and learning outcomes as a result of increased metacognitive strategies. Teachers also demonstrated specific technical skills and knowledge, consistent with other studies that highlight technical skills and knowledge as a key aspect of professionalisation (Alexander et al., 2019; Darling-Hammond et al., 1995). Guided by questions 6 to 9, Table 4 provides illustrative quotes from participants that highlight how AR enhanced pedagogy, including some of the benefits and challenges encountered.

Table 4.

Illustrative quotes demonstrating AR enhanced pedagogy, including benefits and challenges.

Findings indicated that all five expert teachers found that using AR provided a systematic way or structured approach for investigating and improving teaching and learning. While there are identified challenges, such as the time required in addition to regular teacher responsibilities and work, the benefits of using AR to refine and adapt pedagogy led to improvements in student outcomes and teacher effectiveness. This is consistent with other studies that identified both benefits and challenges with using AR (Crawford, 2022a; Osmanović et al., 2021; Pine, 2009).

3.4. Redefining Evidence-Based Practice and Reclaiming Teacher Autonomy

Guided by semi-structured interview questions 9 to 12, all five expert teachers expressed that AR is a powerful tool for teachers, as it allows them to systematically investigate their own practices and make contextually relevant data-driven decisions to improve student outcomes. Table 5 provides illustrative quotes from participants that highlight how AR can be considered as evidence-based practice, redefining what evidence-based practice could be and reclaiming teacher autonomy.

Table 5.

Illustrative quotes demonstrating AR as valuable evidence-based practice and reclaiming teacher autonomy.

Findings suggested that AR empowered participants to develop as teacher–researchers and as a result, redefine neoliberal understandings and expectations of what evidence-based practice is (e.g., standardised testing) or should be (Crawford, 2022a; Pine, 2009). Similar to other studies that attempt to redefine teachers’ knowledge and teachers’ work (Loughran, 2013; Osmanović et al., 2021), taking charge of their professional learning allowed participants to reclaim their teacher autonomy. The data collected, analysed and applied in practice through their respective AR projects was considered valuable and provided a means for informed decision-making about teaching and learning. In this regard, participants suggested that AR could be a legitimate form of evidence-based practice and a useful approach for enhancing pedagogy, which aligns with other research concerning the value of AR for teaching and learning (Crawford, 2022a). Each teacher was enthusiastic about sharing their experience and knowledge of AR with peers and, in turn, thought that implementing AR more widely throughout the educational system would be more useful than some of the mandates and data currently imposed on them. However, they also rightly pointed out that while AR was an appropriate response to the de-professionalisation of teaching and teachers’ work, implementation would require recognition or recompense in workload. Currently, AR is additional to their regular work and expectations, which could not be effectively sustained. They expressed that they were already considerably overworked and their peers and colleagues would feel the same.

Some studies have identified that teachers are often not regarded as having autonomy, authority and self-regulation (J. Buchanan, 2020; Whitty, 2000). This case responds to these factors that impact the perceived de-professionalisation of teaching by providing opportunities for teachers to reclaim their autonomy and self-regulation through AR evidence-based practice. This is particularly pertinent given that other studies (Alexander et al., 2019; Biesta, 2017; Dumay & Burn, 2022; Fuller et al., 2013) have identified that such factors as autonomy and self-regulation are important to what constitutes a profession.

4. Conclusions

Neoliberal educational reforms are a set of policies and practices that aim to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of education systems by applying market principles. Neoliberal reformers contend that such reforms enhance the professional status of teachers by establishing standards of practice and improving transparency through accountability systems (Ball, 2016; Connell, 2013). However, what constitutes quality in education and how to measure its effectiveness, contradicts the very nature of teaching practice and often disregards the complex and nuanced expert knowledge of teachers as articulated by Shulman (Shulman, 1986, 2004). Instead, teachers are left negotiating the arduous and convoluted interplay between professional identity, accountability demands and teacher agency to interpret expected norms imposed on education within the multilayered societal ecosystem. This leads to teacher identities also being reformed in the process and the resultant overall de-professionalisation of teaching and teachers’ work (R. Buchanan, 2015; J. Buchanan, 2020; Hargreaves, 2000). This has had a profound global impact on what it means to be a professional teacher, what society expects from teachers and what teachers expect from themselves.

The aim of this research was to investigate whether AR can be used as a response to the declining status of the teaching profession through the development of contextually relevant evidence-based practice research. To that end, the primary research question explored the extent to which AR can be valued as evidence-based practice and mitigate the perceived de-professionalisation of teaching. The second research question considered if AR could enhance pedagogy and, in turn, challenge neoliberal understandings of the value placed on traditional forms of evidence-based practice. It was not intended that this study would draw from a large sample size and make generalisable statements, but instead provide an in-depth case study as a response to the de-professionalisation of teaching by empowering teachers to enhance their pedagogy through AR. It is important to acknowledge that this study was located in a high-performing school, with a highly motivated group of expert teachers, who were led by a supportive, dedicated and committed principal. However, findings clearly illustrated how action research not only serves as a relevant form of evidence-based practice, but also shifts thinking, redefining what constitutes evidence in education and empowers teachers to take control of their professional work. This effective and valued response to the de-professionalisation of teaching and teachers’ work has important implications for pedagogical development, what constitutes quality in education and the status of the profession.

Although not apparent from the interview data, it is appropriate to suggest that teachers who are considered experts may have already developed their identity in the school before starting with the action research approach. Therefore, one may expect that the practice of AR would fit with their existing orientations of professionalism and evidence, rather than where action research changed their values, way of working and enabling a more professional approach. Given the time limitations of this study, further investigation would be required to determine this; however, findings indicated that in this case, AR led to achieving the outcomes for their individual research project aims. Also, considering aspects of varying degrees of teacher experience would be an important and interesting extension to this research as the results of novice versus expert teachers could be quite different. This may require a larger sample size of teachers working across a number of different school settings, a limitation of this study. Finally, future research could focus on the leadership perspective and explore why the principal values AR as evidence-based practice and how they support their teachers to develop their pedagogy and classroom practice using such an initiative. A larger cross sample of schools may also reveal that not all principals are as supportive of the AR approach given the time commitment associated with such reflective practice and the burgeoning demands of teachers’ work. While the research presented in the article focuses on a specific school context, it could be replicated in other environments and education contexts using the parameters discussed in the methodology or extended in further research, such as longitudinal or in-depth studies on the subject.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The full data set is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions, data relevant to this paper are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the expert teachers who volunteered their time in kind to participate in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahlin, E. M. (2019). Semi-structured interviews with expert practitioners: Their validity and significant contribution to translational research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C., Fox, J., & Gutierrez, A. (2019). Conceptualising teacher professionalism. In Professionalism and teacher education (pp. 1–23). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J., Rowan, L., & Singh, P. (2019). Status of the teaching profession—Attracting and retaining teachers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(2), 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2018). Accreditation standards and procedures. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/deliver-ite-programs/standards-and-procedures (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Ball, S. J. (2000). Performativities and fabrications in the education economy: Towards the performative society? Australian Educational Researcher, 27(2), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S. J. (2016). Neoliberal education? Confronting the slouching beast. Policy Futures in Education, 14(8), 1046–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. (2017). Education, measurement and the professions: Reclaiming a space for democratic professionality in education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(4), 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowne, M. (2017). Developing a teaching philosophy. Journal of Effective Teaching, 17(3), 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, E. L. (1991). The scholarship of teaching from: Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. College Teaching, 39(1), 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A., & Danaher, P. A. (2019). CHE principles: Facilitating authentic and dialogical semi-structured interviews in educational research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42(1), 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J. (2020). Challenging the deprofessionalisation of teaching and teachers: Claiming and acclaiming the profession (1st ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 21(6), 700–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, M. F. (1986). Rhythms in teaching: The narrative study of teachers’ personal practical knowledge of classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 2(4), 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R. (2013). The neoliberal cascade and education: An essay on the market agenda and its consequences. Critical Studies in Education, 54(2), 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R. (2019a). Connected2Learning: Thinking outside the square—Final project report: Curious about learning? Why? Monash University. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, R. (2019b). Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in music education research: An authentic analysis system for investigating authentic learning and teaching practice. International Journal of Music Education, 37(3), 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R. (2022a). Action research as evidence-based practice: Enhancing explicit teaching and learning through critical reflection and collegial peer observation. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 47(12), 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R. (2022b). Explicit teaching and learning: Developing teacher practice to enhance student learning outcomes: Final project report. Monash University. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, R., & Tan, H. (2019). Responding to evidence-based practice: An examination of mixed methods research in teacher education. Australian Educational Researcher, 46(5), 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Guetterman, T. C. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman, B. (2005). Education—Mind your language please. Teacher Development, 9(1), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wise, A. E., & Klein, S. P. (1995). A license to teach: Building a profession for 21st-century schools (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. (2002). School reform and transitions in teacher professionalism and identity. International Journal of Educational Research, 37(8), 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denscombe, M. (2014). Good research guide: For small-scale social research projects (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Training (DET). (2018). Through growth to achievement: Report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools. Commonwealth of Australia. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/download/4175/through-growth-achievement-report-review-achieve-educational-excellence-australian-schools/18692/document/pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Department of Education and Training (DET). (2020). High impact teaching strategies—Excellence in teaching and learning. Victorian State Government. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/support/high-impact-teaching-strategies.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Dumay, X., & Burn, K. (2022). The Status of the teaching profession: Interactions between historical and new forms of segmentation (1st ed., Vol. 1). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entz, S. (2007). Why Pedagogy matters: The importance of teaching in a standards-based environment. Forum on Public Policy: A Journal of the Oxford Round Table, 2007(2), 1–25. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A191817960/AONE?u=monash&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=ea80e3ef (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Ferreira, R. (2022). Teacher identity development within a community of practice (1st ed.). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch, A. A. (2009). The difficulty of raising standards in teacher training and education. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Culture, and Composition, 9(1), 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C., Goodwyn, A., & Francis-Brophy, E. (2013). Advanced skills teachers: Professional identity and status. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 19(4), 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauer, K., & Klein, S. R. (2012). A case for case study research in education. In Action research methods (pp. 69–79). Palgrave Macmillan US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four ages of professionalism and professional learning. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 6(2), 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A., & Goodson, I. (2002). Teachers’ professional lives: Aspirations and actualities. In Teachers’ professional lives (pp. 9–35). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H. C., & Chin, M. (2018). Connections between teachers’ knowledge of students, instruction, and achievement outcomes. American Educational Research Journal, 55(5), 1076–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, E. (2001). Teaching: Prestige, status and esteem. Educational Management & Administration, 29(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy-Clark, S., Eddles-Hirsch, K., Francis, T., Cummins, G., Feratino, L., Tichelaar, M., & Ruz, L. (2018). Developing pre-service teacher professional capabilities through action research. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(9), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenowski, V. (2012). Raising the stakes: The challenges for teacher assessment. Australian Educational Researcher, 39(2), 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaree, D. F. (2000). On the nature of teaching and teacher education: Difficult practices that look easy. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, H., Loeb, S., McEachin, A., Miller, L. C., & Wyckoff, J. (2014). Who enters teaching? Encouraging evidence that the status of teaching is improving. Educational Researcher, 43(9), 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lavy, V. (2007). Using performance-based pay to improve the quality of teachers. The Future of Children, 17(1), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W. D., & Young, T. V. (2013). The politics of accountability: Teacher education policy. Educational Policy, 27(2), 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenberg, B. D., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, J. (2013). Pedagogy: Making sense of the complex relationship between teaching and learning. Curriculum Inquiry, 43(1), 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P., Fleming, J., & Bhosale, J. (2018). The utility of case study as a methodology for work-integrated learning research. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 19(3), 215–222. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/utility-case-study-as-methodology-work-integrated/docview/2227914089/se-2 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Madalinska-Michalak, J. (2022). Recruiting and educating the best teachers: Policy, professionalism and pedagogy. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Mertler, C. A. (2009). Action research: Teachers as researchers in the classroom (2nd ed.). Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, A. (2011). Student standardised testing: Current practices in OECD countries and a literature review. (OECD Education Working Papers, p. 65). OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/working-papers/student-standardised-testing-current-practices/docview/911974022/se-2 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Murphy, M. P. A. (2023). Taking teaching philosophies seriously: Pedagogical identity, philosophy of education, and new opportunities for publication. In The Palgrave handbook of teaching and research in political science (pp. 13–21). Springer International Publishing AG. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, B. (2000). The professional status of teaching: Breaking the pattern of decline. Education Review, 4(5), 8–9, 24. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.200102856 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Osmanović, Z. J., Mamutović, A., & Maksimović, J. (2021). The role of action research in teachers’ professional development. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education, 9(3), 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, P. J. (2017). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life (3rd ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Pelger, S., & Larsson, M. (2018). Advancement towards the scholarship of teaching and learning through the writing of teaching portfolios. The International Journal for Academic Development, 23(3), 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, G. J. (2009). Teacher action research: Building knowledge democracies. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius, A.-K., & Charalambous, C. Y. (2023). Theorizing teaching: Current status and open issues (1st ed.). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, B. (1994). Comparing teachers’ work with work in other occupations: Notes on the professional status of teaching. Educational Researcher, 23(6), 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (2004). Professional development: Learning from experience. In S. Wilson (Ed.), The wisdom of practice: Essays on teaching, learning and learning to teach (pp. 503–522). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2015). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (3rd ed., pp. 25–52). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Spiers, J., & Riley, R. (2019). Analysing one dataset with two qualitative methods: The distress of general practitioners, a thematic and interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16(2), 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research and development. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, J. C., Aelterman, A., Rots, I., & Buvens, I. (2006). Public perceptions of teachers’ status in Flanders. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 12(4), 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, R. (2017). What can be known and how people grow: The philosophical stakes of the assessment debate. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 36(5), 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitty, G. (2000). Teacher professionalism in new times. Journal of In-Service Education, 26(2), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt-Smith, C. M., & Looney, A. (2016). Professional standards and the assessment work of teachers. In D. Wyse, L. Hayward, & J. Pandya (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (1st ed., pp. 805–820). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, M., Miller-Young, J., & Manarin, K. (2024). SoTL research methodologies: A guide to conceptualizing and conducting the scholarship of teaching and learning (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).