Abstract

The importance of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) is recognised by Australian governments and significant reforms are being implemented to increase access to high-quality ECEC. Whilst increased recognition and access are vital, so are strategies to support a high-quality and sustainable workforce. One strategy is for governments to partner with universities to support Diploma-qualified educators to upskill to become teachers. Providing support for Diploma pathway students to be successful in their studies and motivated and to stay in the profession post-graduation is vital. The aim of this study was to investigate a specific design element within one innovative initial teacher education programme for Diploma pathway students—the role of the teaching coach. The teaching coach role was designed to support Diploma pathway students to complete their degree and help create the professional networks needed to sustain them in the profession long term. Using a single site case study approach, qualitative data were collected via semi-structured interviews with teaching coaches. Using the theory of practice architectures to the analyse data, we interrogated the practices of the teaching coaches, how teaching coaches perceived they supported student success and the arrangements that enabled and constrained these practices. From the perspective of the teaching coaches, their role supported student learning and professional networks. The role also provided unanticipated benefits for the teaching coaches themselves. The study highlights the importance of universities going beyond traditional practices to contribute to professional learning and networks for ECEC professionals throughout their careers.

1. Introduction

Major reform has been taking place in the Australian early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector since the late 2000s (Jackson, 2017). In Victoria, the Best Start Best Life reforms (Department of Education, 2024b) aim to ensure that children across the state have access to high-quality, fully funded kindergarten programmes. Since 2013, incremental increases in the number of hours of funded kindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds have increased the need for Bachelor-qualified early childhood teachers (Department of Education, 2023). With demand for kindergarten places forecasted to grow by 46% from 2022 to 2028 (Department of Education, 2024b), an ongoing supply of high-quality early childhood teachers is essential, as is maintaining a strong and sustainable ECEC workforce.

To build a sustainable workforce, the Victorian Department of Education has provided significant funding for a range of programmes, including financial scholarships and incentives, traineeships, and career advancement programmes (Department of Education, 2024b). One initiative was to partner with Victorian universities to offer innovative initial teacher education pathways that enabled Diploma-qualified educators to complete their professional experience placements (herein referred to as placements) in their workplace as they upskilled to become a Bachelor-qualified teacher. Offering opportunities for Diploma-qualified educators to upskill is a longstanding approach in Australia to increase the supply of early childhood teachers (Hadley & Andrews, 2015). Yet placements have traditionally been completed outside of workplaces, resulting in Diploma upskillers not being paid while undertaking placements. Whilst there are significant benefits in upskilling Diploma-qualified educators, these students often experience challenges with university study (Hadley & Andrews, 2015). Common challenges (such as written academic standards) coupled with the potential challenges of undertaking placements in their workplace (discussed below) meant that innovative strategies were needed to support Diploma pathway students not only to succeed in their studies, but also to stay in the profession post-graduation. This article discusses the approach taken in Deakin University’s employment-based pathway to provide targeted support for Diploma upskillers who were working whilst studying online and undertaking placements in their workplace. This targeted support was provided through an innovative role known as a teaching coach.

It is well documented that mentoring and coaching provide a range of benefits for ECEC professionals (e.g., Andrews et al., 2025; Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2021; Nolan et al., 2025; Page & Eadie, 2019). Drawing on the research evidence, the teaching coach role was designed based on the coaching model from the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) (AITSL, 2017). The role of the teaching coach aimed to support students’ successful completion of their degree and help create the professional networks needed to sustain graduates in the early childhood teaching profession long term (Jackson et al., 2024; Nolan et al., 2025; Robertson et al., 2024). The three components of the AITSL coaching model (mentoring, teaching and coaching) provided a foundation for teaching coach practices, which evolved and developed over time.

The aim of the study discussed in this paper was to investigate the practices of the teaching coaches and the conditions that enabled and constrained their practices. Whilst the study did not aim to directly measure benefits for students, we sought to identify practices that the teaching coaches perceived to benefit students. Drawing from interviews with the teaching coaches and the theory of practice architectures as an analytical lens (Kemmis et al., 2014), we also identified unexpected benefits for teaching coaches themselves. We suggest that further development of coaching roles within universities, such as the teaching coach, that provide opportunities for ongoing professional learning and networks, may contribute to sustainability of the ECEC profession.

1.1. Sustaining the ECEC Workforce—The Role of Coaching and Mentoring

Building a high-quality and sustainable early childhood teacher workforce requires a multifaceted approach (Thorpe et al., 2024). Although pay and work conditions are essential arrangements often at the forefront of discussions about workforce sustainability (Thorpe et al., 2024), professional networks that contribute to professional learning and teacher wellbeing, to motivate teachers “to stay and thrive” are essential (Andrews et al., 2025; Bull et al., 2024; Ciuciu & Robertson, 2019; Jackson et al., 2024; Nolan et al., 2025; Thorpe et al., 2024, p. 324). In their study on teacher retention, Ciuciu and Robertson (2019) identified that “Support from … professional networks [are] not just important, but … necessary” (p. 86).

Coaching and mentoring have been defined in multiple ways. In this paper, drawing on the AITSL (2017) coaching model, coaching is defined as “a joint enterprise in which one person supports another to develop their understanding and practice in an area defined by their own needs and interests” (Creasy & Paterson, 2005); and mentoring is viewed as a relationship between a more experienced person and someone “transitioning to a new career stage or role”. Mentoring involves the sharing of knowledge based on experience (AITSL, 2017, slide 15). Both coaching and mentoring are effective approaches to professional learning (Andrews et al., 2025; Nolan & Molla, 2018; Page & Eadie, 2019), supporting teacher wellbeing (Andrews et al., 2025; Kutsyuruba & Godden, 2019) and building professional networks (Kervin et al., 2025; Nolan et al., 2025). Coaching in teacher education programmes has been described as beneficial for coaches and students (Sorensen, 2012), as students can feel a sense of improvement in practice as they work alongside their coach and receive immediate and detailed feedback (Cohen et al., 2024). Mentoring is commonly used for in-service early childhood teachers (Nolan & Molla, 2018), particularly new graduates (Andrews et al., 2025; Nolan et al., 2025), and for pre-service teachers during placements (Graves, 2010; Nicolas et al., 2025). Traditionally, mentoring for pre-service teachers is undertaken solely by an experienced teacher in the placement site as a part of the requirements of an early childhood teaching degree. Considering the importance of sustaining a high-quality ECEC workforce and the increase in alternative pathways to initial teacher education, universities are exploring innovative ways to provide a greater range of mentoring and coaching opportunities for teachers at all stages of their careers (Andrews et al., 2025; Kervin et al., 2025; Nicolas et al., 2025).

The Early Childhood Elevate Mentoring Program (ECEMP) is one innovative example of a university-led mentoring programme for pre-service early childhood teachers. ECEMP provided mentoring by early childhood teachers for Diploma pathway students (Kervin et al., 2025) via a structured online module-based programme that combined “video lectures, written content, professional readings, reflective questions … and … a community of practice” (Kervin et al., 2025, p. 85). Whilst the programme aimed to support pre-service teachers, it also contributed to professional growth and deepened professional identities for the mentors (Kervin et al., 2025). Another example is the Early Childhood Professional Practice Partnership Program (EC PPP). EC PPP provided university-led intensive mentoring for pre-service teachers and their placement mentors. Findings from this programme identified that “intensive mentoring and dedicated time to enable and encourage a professional, trusting and supportive relationship and opportunities to develop mastery of early childhood teaching between the mentor teacher and preservice teacher, had a direct effect on the [pre-service teacher] choices in their career pathways” (Moore et al., 2023, p. 81). Moore et al. (2023) also identified that in Australian ECEC, there is an “absence of extensive and well-established mentoring structures, such as those present in primary schools” and therefore “more support and resourcing from government and initial teacher education institutions” is required (Moore et al., 2023, pp. 83–84). Given the value of these programmes, and ECEC reforms aimed at increasing the supply and sustainability of early childhood teachers, further innovations that provide ongoing learning and professional networks for both pre-service and in-service teachers are essential.

1.2. Diploma Pathway Students

The Diploma pathway into an early childhood teaching degree is a common and valuable approach to building the Australian early childhood teacher workforce. Some Australian universities have specific Degree programmes solely for Diploma pathway students. These programmes (usually 2 years in length) and are designed to build on the prior qualifications and experience of Diploma-qualified educators. In other universities, such as Deakin, Diploma pathway students join the same programme as students completing the entire Degree (usually three or four years) and receive varying amounts of Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) based on their Diploma qualification. Diploma pathway students, many of whom are culturally and linguistically diverse, bring a range of skills, experience and prior knowledge that contribute positively to becoming an early childhood teacher (Harvey et al., 2016) and to diversity in the early childhood teacher workforce (Gide et al., 2022). Despite these positive characteristics, Diploma pathway students often experience a range of challenges undertaking university study, both personally and pedagogically (Aird et al., 2010; Hadley & Andrews, 2015). Pedagogical challenges relate to unfamiliarity with the academic style of university learning, which differs significantly from their prior Diploma-level study in vocational education and training. Diploma pathway students are often challenged by both the written academic standards and university-level professional expectations (Hadley & Andrews, 2015).

In addition to pedagogical challenges, Diploma pathway students often experience personal challenges, such as financial and work obligations, family commitments and changing circumstances (Aird et al., 2010; Hadley & Andrews, 2015) that can impact course completion (Christensen & Evamy, 2011). Diploma pathway students are often mature-age and likely to experience multiple personal factors that require additional and targeted support (Christensen & Evamy, 2011; Hadley & Andrews, 2015). In the employment-based pathway discussed in this paper, the role of the teaching coach was designed to provide this support.

1.3. Work Whilst Studying Pathways—Benefits and Challenges

Globally, various terms are used to describe people being employed to fulfil all or parts of a teaching role while they are working towards the required qualification. Terms include, for example, apprenticeship (Department of Education, 2024a) and learnership (Odendaal, 2014). In Australia, terms include Permission to Teach (PTT), which is used to describe students teaching in primary or secondary schools as they complete their degree (Dawborn-Gundlach, 2025). Work whilst studying pathways to teaching qualifications are often developed in response to workforce shortages (Dawborn-Gundlach, 2025). The term ‘employment-based’ was adopted by Deakin University to recognise that Diploma-qualified educators were required to be employed in an ECEC setting to be eligible for this pathway. Although in some work whilst studying approaches, such as PTT, students are undertaking the full responsibilities of a teacher, in Deakin’s employment-based pathway, students continue to work in the role of a Diploma-qualified educator and are supported by a Degree-qualified teacher until they have completed their degree.

Work whilst studying pathways can have positive benefits for students (Krokfors et al., 2006; Richter, 2016). Significantly, the opportunity to work and study simultaneously provides access for people who may not have been able to access university study due to time, socioeconomic and geographical constraints (Dawborn-Gundlach, 2025; Krokfors et al., 2006). The benefit of being paid while studying is particularly attractive to students (Wyatt-Smith et al., 2022). This increased access and opportunity are beneficial in increasing the teacher workforce (Wyatt-Smith et al., 2022).

In terms of student learning, the practical learning that occurs alongside theoretical learning can support the integration of theoretical perspectives and practice experiences (Krokfors et al., 2006). However, the practical skills of students in work whilst studying pathways have been found to develop more quickly than theoretical skills (Krokfors et al., 2006). The environment that students work in while they are studying can contribute to and influence their developing teacher identity (Wallis, 2023). Good workplace relationships alongside role and personal support are important for students who are working while studying (Meyer et al., 2024). Thinking beyond course completion, supporting students during their course can be a beneficial way for workplaces to invest in future staff (Wallis, 2023).

Alongside the possible significant benefits of work whilst studying pathways, students can experience challenges. Workload pressures can impact the time students have to plan for and enact their workplace role (Krokfors et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2024) and engage with course content (Richter, 2016). Work whilst studying pathway students have reported feeling lonelier due to not having regular in-person contact with others in the university (Krokfors et al., 2006). In addition to challenges reported in the literature, the team designing the employment-based pathway at Deakin University identified possible challenges with students being assessed by a workplace colleague acting in the role of mentor during placements. Concerns included the possibility of bias or difficulties workplace-based mentors may have in providing honest feedback, particularly if the feedback might be perceived as negative. To reduce the challenges experienced by students within the employment-based pathway, the team designing the pathway understood the importance of thinking differently. The allocation of a teaching coach to each student for the duration of their course is a unique innovation aimed at supporting student success and building professional networks.

1.4. The Employment-Based Pathway at Deakin University

The employment-based pathway at Deakin University is an innovative pathway for Diploma-qualified educators to upskill to a Bachelor of Early Childhood Education (Robertson et al., 2024). Traditionally, students in the Bachelor of Early Childhood Education are required to do their placements in a range of settings sourced through Deakin University’s professional experience office. The employment-based pathway allows students who are employed in an ECEC setting in the state of Victoria to do all their placements in their workplace. Since the inception of the programme in 2021, four cohorts of students (a total of 351) have graduated, with a fifth and sixth cohort currently in progress. The first four cohorts graduated via an accelerated version of the pathway, completing their degree full-time over 18 months (Robertson et al., 2024). The current cohorts are undertaking the pathway via a part-time version (minimum two and a half years), in recognition that full-time study is not feasible for all students. The employment-based pathway was designed with the following key components:

- Recognition of prior learning (RPL)Online studyStudent scholarshipWorkplace-based placementsAllocation of a teaching coach

While the focus of this paper is the role of the teaching coach, we provide a brief overview of the other components as a way of understanding the landscape within which the teaching coaches practiced.

RPL—Students receive RPL for the first year of the degree. Year Two entry provides recognition of Diploma pathway students’ prior qualifications and experience, yet it often results in challenges as they miss out on important transitional learning that is embedded within Year One.

Online Study—To provide access for students who work and live in locations across Victoria, including rural and regional, the employment-based pathway is offered online. Whilst online study provides flexibility and access, it can result in challenges for students in navigating the online environment and feeling disconnected from peers through a lack of in-person contact (Richter, 2016).

Study Scholarship—Students are provided with a significant scholarship that is paid in instalments, with the final instalment being paid after 12 months in an early childhood teaching role. While this financial support is beneficial, the increase in cost of living means that many students experience financial concerns.

Workplace-based professional experience placements—Students can continue to work and get paid in their ECEC setting throughout their study by completing placements in their workplace. When completing a workplace-based placement, students work alongside and are assessed by a Bachelor-qualified early childhood teacher who acts as a mentor teacher in their workplace. Whilst this arrangement provides convenience and financial support for students, being assessed by a workplace colleague can present challenges, such as the possibility of bias or difficulties in providing honest feedback.

Allocation of a teaching coach—Students are allocated a Deakin-employed teaching coach who works with them for the duration of their study (Robertson et al., 2024).

1.5. The Role of the Teaching Coach

Teaching coaches are selected for the role based on their extensive teaching experience, with many also having leadership experience, and/or other roles relating to building the capability of teachers, e.g., mentor. Coaches are supported to understand the requirements of their role through The Teaching Coach Guide (discussed below), teaching coach meetings and support from academic and professional staff delivering the employment-based pathway. From 2024, new coaches have been paired with an experienced teaching coach as a buddy. Teaching coaches work with students for the duration of their course, with the exception of a few who have, for various reasons, been unable to continue in the role. In this instance, students have been reallocated to an existing teaching coach. At the beginning of each new cohort of students, the number of teaching coaches required was reviewed and new teaching coaches were employed when necessary.

The teaching coach role draws on the AITSL’s (2017) coaching model. This model, along with much of the literature on coaching and mentoring, focuses on coaching for in-service teachers (AITSL, 2017; Nolan et al., 2025). AITSL’s Coaching Toolkit for Teachers describes coaching as “a professional learning strategy using questioning and conversation to support professional growth” (AITSL, 2017, p. 15). AITSL’s model is designed to holistically support and encourage teachers to grow their practice while developing a sense of responsibility for their learning (AITSL, 2017). Coaching is described as multifaceted, combining teaching, mentoring and counselling (AITSL, 2017).

Drawing on AISTL’s model, the role of the teaching coach in the employment-based pathway is to support students, both individually and as a group, in their academic learning and placements (Robertson et al., 2024). Teaching coaches act as a conduit between the university, the student and the workplace mentor. Within the teaching coach role, the three dimensions of AITSL’s (2017) coaching model are described as:

Mentor—teaching coaches scaffold students’ professional growth and relationships, including relationships with workplace mentors

Teacher—teaching coaches foster students’ knowledge of academic and digital literacy skills, including providing information about university study skills supports

Counsellor—teaching coaches support students with difficult times, such as challenges balancing workload or negotiating complex situations during workplace placements, and provide advice and information about further support services, such as counselling and disability resources.

To enact these three roles, teaching coaches are allocated a small group of students (approximately five) whom they meet with online individually and as a group on a fortnightly basis. Students are encouraged to attend the fortnightly meeting as regularly as possible. The focus of teaching coach–student meetings is flexible to allow students the opportunity to identify aspects where support is required. In addition to these regular meetings, teaching coaches arrange and participate in a triadic meeting (between student, mentor and teaching coach) during students’ workplace-based placements. Teaching coaches support students with demonstrating their reflective practice and mentors in providing unbiased and honest feedback to students (Robertson et al., 2024).

To support teaching coaches in their role, they are provided with a Teaching Coach Guide. The guide was developed by academic staff in 2021 and further developed in 2024 in consultation with the teaching coaches. The initial guide was a brief three-page document that introduced the teaching coach role and its alignment with the AITSL’s (2017) coaching model, the requirement for regular meetings with students and triadic meetings with students and mentors during placement. This initial guide stated the necessity for teaching coaches to identify and plan for individual and group needs. The second iteration of the guide was more detailed (ten pages) and drew on the experiences of the teaching coaches to provide an outline of suggested practices at different times of the year. The second iteration also drew on the theory of practice architectures to provide details of sayings, doings and relatings that teaching coaches found effective in their practices.

An additional support for the teaching coaches is fortnightly online teaching coach-university staff meetings are facilitated by staff from the employment-based pathway project team (e.g., an early childhood academic and/or the project manager). As with the teaching coach–student meetings, the teaching coach-university staff meetings are flexible to meet the needs of the coaches. The project team provides key information, such as enrolment information and dates, information about units of study, and addresses any questions or concerns from the coaches. These meetings are also an opportunity to celebrate and share effective practices and achievements. In addition to the fortnightly meetings, from 2024, new teaching coaches have been allocated an experienced teaching coach as a ‘buddy’, to help them settle into the role.

Teaching coaches are employed part-time, with an allocation of approximately 3–4 h per week, depending on student numbers. Whilst coaches are expected to undertake the key engagements described above, there is flexibility with how and when they use these hours, depending on the needs and engagement of students.

2. Methods

This study was undertaken as part of a larger project funded by the Victorian Department of Education that seeks to understand How are initial teacher education programmes understood to be innovative and what design elements are most effective? The findings discussed in this paper focus on the design element “the teaching coach within the employment-based pathway into Deakin University’s Bachelor of Early Childhood Education”. Specifically, this study aimed to address the following research questions:

What are the practices of teaching coaches in Deakin University’s employment-based pathway and how do teaching coaches perceive these practices to support students?

What arrangements do teaching coaches in Deakin University’s employment-based pathway perceive to enable and constrain their practices?

Given that the teaching coach role was an innovation unique to Deakin University and the aim of the research was to understand the lived experiences of the teaching coaches, a qualitative single-site case study approach was selected as an appropriate methodology (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). In keeping with this single-site approach, the study was framed by the theory of practice architectures (Kemmis et al., 2014). As an ontological site-based theory, the theory of practice architectures attends to practices and conditions of practices as they unfold in individual sites (Kemmis et al., 2014). Whilst the theory does not aim to achieve findings that are universally transferable, generalisations can be made across sites that experience similar practices and practice conditions (Kemmis et al., 2014). The combination of a qualitative single-site case study and the theory of practice architectures provided a means to develop a rich and in-depth understanding (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016) of the teaching coaches’ perspectives on their role within Deakin University’s employment-based pathway, which was the aim of the study. The study was undertaken by the early childhood team delivering the employment-based pathway.

2.1. Participants

Participants were eligible for this study if they had worked as a teaching coach with at least one cohort in the Bachelor of Early Childhood Education in this employment-based pathway. All 26 teaching coaches who had worked in the pathway between 2021 and 2025 were invited to participate in the research via an email from the research fellow, with 18 taking up the invitation. All participants were female and either current or ex-early childhood teachers, with the exception of one who was an ex-primary teacher. All participants were highly experienced teachers, as this was an expectation of anyone taking on the role, with many having had multiple roles such as leadership, educational leader, mentor to placement students, and several had prior experience working at Deakin University. Eight teaching coaches indicated they held or were studying towards postgraduate qualifications, including Master’s and Doctoral levels. All coaches were recommended through professional networks of academics involved in the Bachelor of Early Childhood Education at Deakin University and were identified as experienced, dedicated and accomplished early childhood teachers. Following approval from the Deakin University Human Ethics Advisory Group, written consent was obtained from each participant. To remove possible conflict between teaching coaches and the early childhood team who were delivering the employment-based pathway, undertaking the research, and positioned as the teaching coaches’ employer, a research fellow was employed to undertake data collection and curation.

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, adopted to enable in-depth exploration of participants’ lived experiences and perspectives while maintaining some consistency in participants’ reporting (Seidman, 2019). As in previous large mixed methods studies, interview only data is justified as it is reported here as one aspect of the overarching data collection approach (Steed et al., 2023). Reporting semi-structured interview data only is also considered appropriate for zooming in on the perspectives and experience of a particular group of participants, rather than searching for objective truth (Seidman, 2019). Interview questions, and the research questions they aimed to answer, included:

- What resources, skills, or understandings have you brought to help you in the coaching role? (Research question 2)How have you been supported in your role? (Research question 2)How do you engage with the students as a teaching coach? (Research question 1)

Interviews were conducted online via ZOOM and were between 40 and 90 min in duration. Data were collected between September 2022 and September 2025. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Participant anonymity and student and staff privacy were maintained by using pseudonyms and removing any identifying information.

2.3. Analytical Framework

The theory of practice architectures was used as a lens through which to examine the data. According to the theory, practices are made up of bundles of sayings, doings and relatings that hang together in the ‘project’ of a practice (Kemmis et al., 2014). Sayings are socially constructed words, understandings and ideas communicated within the practice; doings involve the ways in which action, activity, or in-activity occur within physical space, and relatings are the interconnected relationships and dynamics involved in practices (Grootenboer & Edwards-Groves, 2023). The project of the practice, in simplest terms, is the answer to the question ‘What are you doing?’ (Kemmis et al., 2014). In the case of the teaching coaches, the project of their practices was to support students to successfully complete their degree, equipped to stay in the ECEC profession long term.

The conditions that shaped the teaching coaches’ practices are known as the ‘practice architectures. The practice architectures are made up of three dimensions—cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political—and can be both within and brought to the site of practices (Kemmis et al., 2014). The practice architectures, also known as conditions or arrangements, can shift and change over time, making it also possible to transform practices (Kemmis et al., 2014). For example, material-economic arrangements brought to the practice, such as previous work experiences, can shape the doings of a practice (Cooke et al., 2020). Similarly, cultural-discursive arrangements within the site of the practice, such as The Teaching Coach Guide, can shape the sayings and doings of a practice. It is through understanding the conditions of practices that new ways of understanding, doing, and relating can occur (Kemmis et al., 2014).

Using the dimensions of practices and practice architectures, data were thematically analysed employing a modified table of invention (Kemmis et al., 2014). This table helped to identify common themes within teaching coach practices and the arrangements brought to and within the university that shaped these practices. This analysis also helped us to identify the intention and the outcome of teaching coach practices.

3. Results and Discussion

We begin by discussing three key practices of the teaching coaches and how the teaching coaches perceived these supported students. This is followed by key arrangements brought to and within the university that supported teaching coach practices. Lastly, we discuss the unanticipated benefits for the teaching coaches themselves. We conclude by advocating further development of university-led innovations to support professional learning and networks that can help sustain the ECEC profession.

3.1. The Practices of Teaching Coaches—What Do They Do, Say and How They Relate

Three key themes were identified in the teaching coaches’ description of their practices. Whilst each of these themes includes various sayings, doings and relatings, they have been categorised according to the dominance of each dimension within the practice. The themes are: Responding to student needs (doings); Encouraging thinking and reflection (sayings); and Building connections (relatings).

3.1.1. Responding to Student Needs (Doings)

Teaching coaches identified that one of the most important aspects of the role was to understand students and their context and respond flexibly to students’ needs. In the beginning, teaching coaches negotiated teaching coach–student meeting times that worked for both individuals and groups, and emphasised the importance of regular attendance at these meetings. Within the meetings, it was important to get “to know [the students] and … their needs” (Tiffany). Similarly, Tracey explained, “you really need to listen to really try and hear what the students are having trouble with”. Support for students is “very individualised [and like a] community of practice” (Tiffany). Although the teaching coach groups were not formally labelled as a community of practice, the experience for coaches reflected the community of practice approach used by Kervin et al. (2025).

Several coaches discussed a shift in the doings of their practices as students progressed through the course (Kemmis et al., 2014). In the early stages, supporting students with the expectations of university study, such as academic writing and navigating university systems, was a high priority. Jennifer explained:

Initially, it was … ’How do I upload an assessment or [use] Turnitin?’. Once they … got into the rhythm of things [they moved] … to extending their own pedagogical practices. Towards the end they were … looking … on to being an early childhood teacher [and they were more interested in] the VIT [Victorian Institute of Teaching] process and … interviewing [for teaching roles].

Early support was needed to help students make the most of their university experience within the context of the challenges of an employment-based pathway (Krokfors et al., 2006; Richter, 2016):

They find it overwhelming to transition into that university world and understand the expectations … there is the risk of moving in a way where it’s about just getting it done rather than really immersing oneself in the experience and the learnings … and then finding the time to reflect on theory and practice. As a teaching coach, you have to recognise when that’s happening and call it out in the most encouraging way possible.(Megan)

Similarly, the challenges for students in navigating study and life were explained by Kate as:

Whether it be financially dropping work, and the whole structuring of who’s taking care of the children, who’s cooking … that was something that was a topic of conversation … from the start … because they had to not only set up a new routine as a student, but they also had to set themselves a new routine … being a student and educator.

This responsive right time, right support approach contrasted to other university-led approaches to mentoring, such as ECEMP and EC PPP, which were more structured (Kervin et al., 2025; Moore et al., 2023). Whilst supporting students to navigate the practical challenges of university study, teaching coaches also recognised the importance of encouraging thinking and reflection.

3.1.2. Encouraging Thinking and Reflection (Sayings)

Teaching coaches viewed supporting students to critically reflect on their teaching practices as important in promoting high-quality teaching and learning, often using questions as provocations (Kervin et al., 2025). For example, Angela encouraged students to think more deeply when observing, documenting and planning for children’s learning. Similarly, Michelle encouraged students to question the practices in their centre “What does your centre do? Why? Where did this come from? What theory does that connect to?”. Teaching coach perspectives were that through coaching, the students became used to having reflective conversations and reflection started to become part of their practice and “who they are as a teacher” (Michelle). These experiences of learning to reflect in a safe environment are instrumental in the important work of forming teacher identity (Ciuciu & Robertson, 2019; Wallis, 2023).

Some coaches said that encouraging critical reflection was particularly important given the context of the employment-based pathway and students undertaking placements in their workplace. In recognising the value and importance of this pathway, Tracey felt it was harder to get “the students to get off the dance floor onto the balcony and watch what they are doing and be self-critical … because when we’re in a place of work, we [are more] comfortable””, thus, identifying that connecting theory and practice can be challenging for students in an employment-based pathway (Krokfors et al., 2006).

Several teaching coaches encouraged students and workplace mentors to get creative and “think outside of the box” (Tiffany) in creating the conditions for robust critical reflection, suggesting “why not go to a coffee shop and have that planning meeting?” (Tiffany). In a similar manner, Michelle identified:

I think [moving to a different physical space] really enhanced him, [gave him] breathing space. If we’re talking about teacher retention, we need to be looking after the mentor teachers as well as the students and looking at some of those higher up things that might be causing complexity.

Echoing Kervin et al.’s (2025) recognition that support and mentoring are important for teachers at all stages of their careers.

Several coaches encouraged students to find other professionals to critically reflect with, beyond the teaching coach and post-graduation:

If you’re not happy with how something is going, who is your go-to person? Who are you going to go and reflect with … so that you can think about what you might do next time or what you might change up in your programme?(Stephanie)

This comment reflects the coaches’ understanding that professional networks both within and beyond workplaces are important for ECEC professionals (Ciuciu & Robertson, 2019; Nolan et al., 2025).

In the sayings of their practices, teaching coaches were deliberate in not giving all the answers; instead, aiming to create the conditions for students’ thinking and reflection to occur. Teaching coaches reported that the encouragement to think and critically reflect helped to close the gap between the development of practical and theoretical skills for students in employment-based pathways, which is also identified by Krokfors et al. (2006). Teaching coaches recognised that creating a safe space for students to be brave and critically reflect required building positive relationships and connections.

3.1.3. Building Connections (Relatings)

Teaching coaches identified the importance of building relationships with students, between students and with workplace mentors and employers.

Relationships with students. Developing relationships with students was important in providing emotional support, reassurance and encouragement. A key aspect of Stephanie’s relatings involved “Encouraging [students] to really have a go and keep going … [to help them] come out feeling confident and competent”. Similarly, Michelle said “it’s all about … rising people up and figuring out their gifts and empowering people and their agency … it’s keeping people inspired, keeping people motivated”. In summarising the role of the teaching coach, Megan said: “An image of a cheerleader comes to mind. You’re … there … saying you can do it … just continually encouraging them and checking in with them … and … validating [their experience]”. The teaching coaches’ relational practices became a social-political arrangement that championed students to become empowered and agentic teachers (Kemmis et al., 2014; Weston et al., 2024).

This care for students’ wellbeing (Kutsyuruba & Godden, 2019) was evident in coaches’ advice to students at times of stress: “I know it feels counterproductive … I know you’re overwhelmed but switch off for a day” (Megan). Similarly, in encouraging students to take care of themselves within the busyness of work, study and family life, Stephanie said:

There were lots of conversations about ‘You’ve got to put your own oxygen mask on first, you can’t be all things to everybody. If you want to do well in this course and get the most out of it … you’re going to have to make decisions about how you look after your own wellbeing.’

Some teaching coaches indicated that students’ graduation marked an end to the teaching coach–student relationship. Monica saw this as a “professional boundary”. Whereas for other coaches, their relationship with students continued beyond course completion, thus providing a professional network post-graduation. For example, Megan said she emailed past students about workshops and other things they might be interested in. Michelle and Tiffany explained that students had reached out for support with VIT registration, interviewing, CV [curriculum vitae] preparation and writing transition learning and development statements: “It’s the first year of teaching and they’ve still got me as the sort of ‘Unofficial Deakin Carer’” (Tiffany).

Relationships between students. Teaching coaches’ practices included fostering relationships between students in their coaching group. Coming together on a regular basis, offered the opportunity for “networking, support, wisdom sharing, collaborative discussion, enhanced reflective practices and friendship” (Tiffany). Jennifer described catching up with her group as “wonderful, for … students to have networking, especially doing an online course”. These comments identify the importance of the teaching coach role in addressing potential issues of online learning in employment-based pathways, such as loneliness (Krokfors et al., 2006). From the perspectives of teaching coaches, the group environment not only addressed social isolation but also supported students to see that they were not alone in their experiences. Students were able “to see and hear others that are experiencing similar struggles and wins” (Allison). Coaches reported that some student groups developed a “lasting connection” (Stephanie) that they believed would continue beyond graduation, thus providing a professional network to sustain them in their careers (Ciuciu & Robertson, 2019).

Relationships with workplaces. Teaching coach relational practices also included connecting with mentor teachers and leaders in the settings where students were employed. Teaching coaches advocated for students, their study needs and requirements, as Kate explained “Sometimes my students would come to me … and say I’m not getting … sufficient planning time … It’s not about me stepping on anyone’s toes … it’s about sharing with students’ ways to professionally navigate situations themselves”. Whilst advocating for students, coaches understood the complexities of workplaces and aimed to respectfully “bridge the gap” (Kate) between expectations of the workplace and the university. Coaches also played a role in helping workplace leaders address concerns about students. For example, a leader contacted Megan to “say they were concerned about a student, and what should they do?”. This multilayered support contributed towards “healthier workplace outcomes” (Tiffany). This finding aligns with literature identifying the importance of positive workplace relations in early childhood, particularly for those working while studying (Ciuciu & Robertson, 2019; Meyer et al., 2024). Michelle reflected that she “felt quite empowered as a teaching coach” because of her capacity to support both students and workplaces.

3.2. The Arrangements That Enabled and Constrained the Practices of the Teaching Coaches

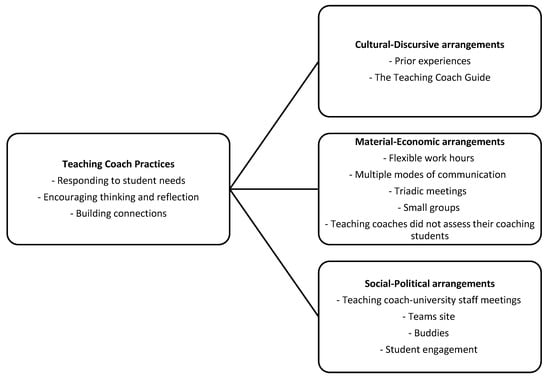

Following the theory of practice architectures, we examined the key arrangements brought to and within the university that enabled and constrained the teaching coaches’ practices, as summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The practice architectures that enabled and constrained the teaching coach practices.

3.2.1. Cultural-Discursive Arrangements

Two key cultural-discursive arrangements (see Figure 1) enabled the practices of the teaching coaches: Prior experience and The Teaching Coach Guide.

Prior experience. Teaching coaches were selected for the role based on their extensive experience as ECEC teachers and leaders, which positioned them well to transition to the role of a teaching coach (Cooke et al., 2020). Some teaching coaches shared in detail about their previous roles, Jennifer, for example, had been a teacher for over 14 years, an educational leader and nominated supervisor and Tiffany had “been in the profession for over 30 years”. Like participants in Kervin et al.’s (2025) study, the teaching coaches’ prior experiences shaped their coaching practices and helped the coaches to understand the landscape of students’ experiences. Megan said, “bringing my experiences as an early childhood teacher helped my awareness of workforce challenges and the things that might contribute to compromising teacher wellbeing”. Prior experiences also meant that coaches understood the importance of, and what is needed to support, high-quality ECEC, as stated by Christina, “We need to make sure [teachers] feel passionate and interested, and are supported and feel valued”.

While all teaching coaches were current or ex-teachers, some also had experience in leadership roles, equipping them with the skills to respond to student needs, build connections and encourage thinking and reflection. Jennifer said, “the experiences of my leadership roles have really helped me to engage people, to be flexible and acknowledge everyone’s uniqueness”. Similarly, Laura felt the teaching coach role aligned with her passion for leadership and with the relational practices she had enacted within past leadership roles.

In addition to teaching and leadership experience, coaches brought a deep passion for ECEC, as evidenced by Erin:

My life’s work is the main resource that I have … and also, I’m very passionate about education. I am particularly passionate about early education because we set such great foundations. The power that we have as early educators … We really do have an important role in society.

This deep passion and understanding of the important role of ECEC shaped the way teaching coaches encouraged students to reflect deeply on who they are as teachers and practices for high-quality ECEC.

In addition to their prior experiences, teaching coaches drew on support provided by the university.

The Teaching Coach Guide. This document, provided to coaches when they began the role, was instrumental in shaping practices. The guide explained the multifaceted nature of the role based on the AITSL coaching model, as Laura explained, “[the course director] created this … matrix of what it was … mentorship, counselling, and teaching”. Laura, one of the first teaching coaches, said the guide provided clarity on what was expected “Everything is really clear … on what to be doing”. Similarly, one of the more recently employed coaches, Monica, explained, “It’s a great little reference guide … it breaks everything down”. The cultural-discursive arrangement of The Teaching Coach Guide, which evolved along with the teaching coaches’ practices, worked in conjunction with key material-economic arrangements.

3.2.2. Material-Economic Arrangements

Material-economic arrangements (see Figure 1) that were key to shaping teaching coach practices were: Flexible work hours; Multiple modes of communication; Triadic meetings; Small groups; and the academic team ensured that Teaching coaches did not assess their coaching students if they were also lecturing or tutoring in the degree.

Flexible work hours. Whilst teaching, coaches held meetings with their students at regular times in the evenings, coaches noted the importance of being flexible with their time to support students, as stated by Laura:

You have to have quite a bit of flexibility with your time. Some people want or need meetings in the evenings because they’re working in the day. Some people prefer to meet when they have their days off. So, being a bit flexible with times is important … [as is] replying in a timely manner. If they’re … asking a question in relation to an assessment task, they don’t really have time to wait for a week until you can point them in the right direction. So, you have to be quite available.

Some teaching coaches were more available and flexible than others, as noted by Tracey:

I’m lucky, I’m retired, so I have a lot of spare time. So, I made myself available to them from 10:30 in the morning till 10 o’clock at night … and if they wanted me on the weekends, I just asked them to text and ask me to ring them.

Tracey understood that for the other coaches who were juggling multiple roles, “there’s pressure … to manage” their time. Providing increased flexibility in student support is an ongoing consideration for universities, particularly with the increase in alternative pathways (Dawborn-Gundlach, 2025; Richter, 2016) and if teaching coaches are able to practice in the flexible ways needed to support students effectively.

Multiple modes of communication. Coaches used multiple modes to communicate with their coaching groups, which enabled the practice of responding to student needs and building relationships. Whilst regular meetings were held via Zoom, most coaches also used WhatsApp, text, phone and email. Coaches noted that the use of phone and WhatsApp was preferred by many students and contrasted to the more formal use of email regularly used between students and academic staff. Modes of communication were usually discussed early and depended on student preferences.

Triadic meetings. A key arrangement that enabled relationships between teaching coaches and workplaces was triadic meetings. As described earlier, the purpose of the triadic meetings was to facilitate honest communication and unbiased assessment between the student and their workplace-based mentor (Robertson et al., 2024). Just as flexibility was important in the teaching coach relationships with students, flexibility was needed when communicating with workplaces, as Stephanie explained, “Making contact with the mentor teacher and … trying to find times that suited everybody … was tricky. I tried … to do it in [their] planning time [but sometimes] we … had to find other ways [such as] after hours”. Allison acknowledged the importance of having clear communication channels to ensure that mentor teachers and employers were familiar with the university expectations. The importance of connections between universities and education settings was identified by Nicolas et al. (2025).

A university decision in designing the teaching coach role was that triadic meetings would be held online to provide all employment-based pathway students with the same experience, regardless of location. One teaching coach saw this as a constraint to relationship building and not in line with the importance of flexibility in meeting student needs “I don’t like that. That rule needs to change” (Angela). This demonstrates the effect that material-economic arrangements can have on relational practices (Kemmis et al., 2014).

Small groups/teaching coaches did not assess their coaching students. These arrangements worked together to enable a different kind of relationship than what students had with their lecturers. Teaching coaches perceived that these arrangements created the conditions for students to be vulnerable and honest about their understanding and experiences, a crucial element of preparing teachers (Weston et al., 2024). As Tracey explained:

It’s the added level of someone to talk to, and it’s [a] closer [relationship] in that we’re not lecturers. [They] can maybe be more critical about something or say … I still don’t get it. [They] might be a little more brave about asking for help [because they are not] in a huge room of people.

This finding, again, highlights the influence of material-economic arrangements on the vital relational aspects of becoming a teacher (Weston et al., 2024).

3.2.3. Social-Political Arrangements

Whilst the arrangements discussed (see Figure 1) here could be viewed within the material-economic domain, we discuss them as a social-political arrangement because they created conditions for relationships that were important in shaping teaching coach practices. These arrangements were: Teaching coach-university staff meetings; Teams site; Buddies; and Student engagement.

Teaching coach-university staff meetings. The arrangement of fortnightly teaching coach-university staff meetings (where teaching coaches meet with an academic or professional staff member from the project team) created a sense of community for the teaching coaches (Kervin et al., 2025) and enabled the teaching coaches to feel more confident in undertaking their practices. Teaching coaches consistently discussed the value of the meetings and the relational connections they fostered. Erin explained, “it is nice having that get-together with the rest of the coaches … feeling part of that team”. Similarly, Michelle described feeling a sense of collegial support from the teaching coach group, which in turn made her feel empowered within her role. Laura said, “I feel like we’re really well supported … we can go in with any questions … things [the students] may be concerned about … We’ve got great support from [academics] and [the professional] team”. Because the teaching coach role is part-time, many of the teaching coaches had other professional roles which sometimes clashed with meeting times. Although the meetings were recorded, coaches missed the opportunity for relational interactions. Some managed this by catching up with an individual coach at another time.

Teams site. In addition to teaching coach-university staff meetings, a dedicated Teams site was used to provide support and resources to coaches. Examples of resources include: documents outlining academic integrity information, placement expectations and The Teaching Coach Guide. The posts function of the Teams site, which is monitored by the employment-based pathway academic and professional staff, is used for support and clarification. As Laura explained “we can post [questions] on there … [and] either the [programme manager] or [course director] or [academic staff member] reply”. This arrangement enabled the coaches to uphold timely support for their students.

Buddies. From the beginning of 2024, the four new coaches were allocated a buddy from the pool of nine experienced coaches to help them understand and settle into the role. While not all new coaches participated in an interview, one of the coaches who experienced the support of a buddy, Monica, said it made for a “supportive environment” and was “really beneficial” to have someone, in addition to the academics, on the project to turn to for advice. This finding highlights that relationships and communication with others involved in a practice are invaluable in learning ‘how to go on’ in a practice (Cooke et al., 2020). Monica’s reflection that the buddy supported her practice as a teaching coach also identifies how the arrangements supporting the teaching coach practices evolved and developed over time.

Student engagement. Whilst students’ attendance and engagement were not formally recorded, teaching coaches anecdotally reported in their interviews that levels of student participation in coaching enabled and constrained coaches’ practices. Groups and individuals that were really engaged, attended all meetings and contributed to discussions created a positive and engaged atmosphere for students and coaches. Kate explained:

[Students] that have [an] in-depth, ingrained passion for working with young children … [and also] the process of learning as an exciting opportunity which sparks joy … trickles into any sort of communication that they have with others; which fosters motivation and provides [a] positive community of practice.

Not all students were so engaged, and this affected Heather’s own motivation “I’m not as passionate [this time] because the students are not as keen or committed”. Most coaches recognised that engagement looks different for every student and it was important to check in as Kimberley described, with “a text message to say ‘Just touching base to see how you’re going. Remember, I’m here, and more than happy to meet with you, just let me know’”.

The arrangements discussed here primarily worked to shape teaching coaches’ practices with the aim of supporting students’ study success. Both the arrangements and associated practices also resulted in unanticipated benefits for the teaching coaches themselves.

3.3. Unanticipated Benefits for Teaching Coaches

Whilst the teaching coach role was designed to support students, interviews revealed that there were unanticipated benefits for the teaching coaches (Kervin et al., 2025), initiating new ways of practicing (Cooke et al., 2020; Kemmis et al., 2014). Key benefits for teaching coaches were: Learning and confidence (doings); New perspectives (sayings); and an increased Professional network (relatings).

Learning and confidence. As experienced ECEC professionals, some coaches were motivated to take on the role of teaching coach to offer themselves “a little bit of extra … professional challenge” (Monica), something they felt they needed at that point in their career. This connects with findings from Robertson et al. (2024) that experienced teachers are looking for more variety in leadership roles and career progression. Coaches identified the development of leadership and communication skills. For example, Kate described the role as an “opportunity to develop leadership skills … for myself and communication skills with a variety of different individuals”. Learning and practice shifts occurred both within their teaching coach role and, for some coaches, within their other professional roles. Monica described how the teaching coach role supported her in developing a deeper knowledge about working with adults and gave her more confidence professionally:

It’s … made me more confident in sharing my thoughts [and] giving feedback to teachers or the people that I’m overseeing. Giving … tough feedback … not negative but saying … ’I think you need to be able to concentrate on this area of your practice’. Versus maybe in the past, when I was trying to keep everyone happy all the time … this role has helped me frame it in a way that I think is accessible for the person listening.

In reflecting on her experiences as a teaching coach, Erin said, “I would be a way better teacher now … it’s just been another part of this learning journey for me”. Similarly, in providing details of her experiences as a new teaching coach, Monica explained, “I’m getting braver … I … sat back for the first six months and didn’t say much … as I got more confident … I can contribute, when I’ve got a problem … I’ll bring it up in a meeting … I offer experience and advice now”. This development in practice and confidence echoes calls from (Moore et al., 2023) who advocate for part-time leadership pathways for experienced teachers that build their professional capabilities, while supporting teachers to maintain part-time teaching roles.

New perspectives. Some teaching coaches described a shift in their thinking over time. For example, in recognising a shift from needing to be an expert to understanding that she could learn alongside the students, Megan explained:

I started to let go of the pressure and expectation that I [had to be] an expert. Instead … we’re learning together … I didn’t always have the answers, sometimes … another student [had the] answer … I started to … forget about the title that comes with the role … and instead, focus on the relationships and notice what … students need or want.

Megan’s comments reflect Nolan and Molla (2018) who reported that mentoring can, and should, be a shared collaborative learning process where mentors do not need to be an expert.

Some coaches developed new perspectives by being exposed to the course content, as noted by Emma “I’ve definitely learned a lot about the unit content. There were things that I was like, ‘oh, that’s interesting’ … there are concepts … that are new since I did my degree”. Monica noted that her assigned teaching coach buddy had “quite a different teaching philosophy, so we ended up having a few interesting conversations”. Coaches saw this new learning and thinking as professionally rewarding (Kutsyuruba & Godden, 2019).

Professional networks. Teaching coaches indicated that the role enabled both participation in, and contributions to, professional networks where she felt “respected and valued” (Laura). Professional networks included ongoing relationships with students, other teaching coaches and the Deakin University community. Monica explained there was a “particular student I connected with [and] she was a support for me when I needed someone to vent to”. Laura said, “It’s really great to have met some like-minded people and … being part of a really professional organisation has been a great experience””.

Some coaches mentioned attending the annual Deakin Early Childhood Conference and the value of this opportunity for professional development and networking. Megan said she took up an opportunity “to present [a] keynote based on some of my previous studies and research [and] that was a really exciting … being able to contribute in that way”.

Within their valuable new professional networks (Ciuciu & Robertson, 2019), coaches were able to “learn from each other” (Jennifer) and had increased opportunities for reflective practice:

As teachers, we would love something like this … it’s that feeling of contribution back to the profession and hoping that the support and guidance and mentoring that we have given the students will help them as they move into the sector and become part of that network with us.(Jennifer)

4. Conclusions

The findings from this study identified teaching coach practices that, from the perspective of the teaching coaches, provided benefits for Diploma pathway students and their workplaces. As a conduit between the university, students and their workplace in the Department of Education funded employment-based pathway at Deakin University, teaching coaches provided support throughout students’ study and created the conditions for professional learning and networks that have the potential to help teachers “stay and thrive” in the ECEC profession (Bull et al., 2024; Ciuciu & Robertson, 2019; Nolan et al., 2025; Thorpe et al., 2024, p. 324). Teaching coaches’ practices that were flexible in providing caring and relational ‘right time, right support’ were perceived to help students navigate university study. They were also perceived to develop vital high-quality teaching practices, such as critical thinking and reflection. Teaching coaches themselves developed their learning, confidence and new perspectives, along with a professional network and career opportunities beyond the classroom (Department of Education, 2024b; Moore et al., 2023; Robertson et al., 2024; Jackson et al., 2024). The teaching coach role empowered experienced teachers to give back to the ECEC profession as they created communities of practice in support of high-quality teachers.

Within the context of significant ECEC reform and recognition of the need to develop a strong, sustainable workforce (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2021; Education Services Australia, 2021; Nolan et al., 2025) considerable funding is being provided for a range of workforce initiatives (Department of Education, 2024b). Yet, as identified by Moore et al. (2023), the ECEC sector has an “absence of extensive and well-established mentoring structures” (p. 83). We echo their call for “more support and resourcing from government and initial teacher education institutions” (p. 84) to provide ongoing coaching and mentoring for ECEC professionals across all stages of their career (Kervin et al., 2025; Nolan et al., 2025).

In the current climate of workforce shortage, not just in ECEC, but across the education sector, we propose that university-led innovations, such as the role of the teaching coach, that contribute towards professional learning and networks for in-service and pre-service teachers, are an important contribution to building a strong and sustainable education workforce. The vital need for an ongoing supply of teachers, coupled with the increased diversity of those undertaking initial teacher education, requires universities to think beyond traditional support structures. Flexible roles that provide relationally-focussed ‘right time, right support’ for students, and alternative career pathways and professional networks (Jackson et al., 2024) for experienced teachers are essential. The value of both continuing and expanding the teaching coach role was best articulated by two of the Deakin teaching coaches:

I wish I’d had it, and I hope it continues. In my experience, [this] and school readiness funding have been the two most wonderful displays of funding allocation from the Department of Education. It would be fabulous to see that funding continue [to provide] this lifeline that flows right through. If we’re going to throw them in the deep end, let’s give them a little lifeboat. When the rough seas come, and they will, and when they do, jump in here for five minutes. Let’s regroup, let’s chat. Let’s go and look at the sunshine. Let’s make sure you’ve had enough of a cup of tea.(Tiffany)

I think it’s fabulous that … the teaching coach role was included. I really hope that it continues. I would love to see it be included in [all] the programmes … if there was just someone assigned to a group of students to check in … with students while they’re studying … I really enjoyed my time as a teaching coach … I thought it was a real privilege to be able to be so involved in these students’ journeys. Really rewarding, and a really lovely way to contribute to the quality and the sustainability of a profession that I really care about (Megan).

This study is limited to the perspectives of the teaching coaches and to one source of data. Further research is needed to understand the perspectives and experiences of students within the employment-based pathway and university staff delivering the programme and to triangulate through multiple sources of data. Bringing together the experiences and perspectives of all stakeholders can strengthen university-led innovations that aim to support sustainability of the ECEC workforce.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and K.B.; Methodology, M.C., R.F. and K.B.; Formal analysis, M.C. and R.F.; Investigation, R.F. and K.B.; Data curation, R.F. and K.B.; Writing—original draft, M.C. and R.F.; Writing—review & editing, M.C., R.F. and K.B.; Project administration, M.C. and K.B.; Funding acquisition, M.C. and K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the VICTORIAN DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, grant number RM42017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Ethics Advisory Group, of DEAKIN UNIVERSITY (HAE-22-068/25 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Natalie Robertson, Amanda Mooney and Damian Blake the project leads responsible for funding acquisition, and Fiona Kneen, the innovative initial teacher education project manager.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECEC | Early Childhood Education and Care |

| ECEMP | Early Childhood Elevate Mentoring Program |

| EC PPP | Early Childhood Professional Practice Partnership |

| AITSL | Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership |

| RPL | Recognition of Prior Learning |

| VIT | Victorian Institute of Teaching |

References

- Aird, R., Miller, E., van Megen, K., & Buys, L. (2010). Issues for students navigating alternative pathways to higher education: Barriers, access and equity: Literature review prepared for the adult learner social inclusion project. Queensland University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, R., Hadley, F., Waniganayake, M., Hay, I., Jones, C., & Liang, X. M. (2025). Sustaining the best and the brightest: Empowering new early childhood teachers through mentoring. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 14(2), 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2021). Shaping our future: National children’s education and care workforce strategy (2022–2031). Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2017). Coaching toolkit for teachers. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/coaching-resources-complete-set.pdf?sfvrsn=8ab8ec3c_0 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Bull, R., McFarland, L., Cumming, T., & Wong, S. (2024). The impact of work-related wellbeing and workplace culture and climate on intention to leave in the early childhood sector. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 69, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L., & Evamy, S. (2011). MAPs to success: Improving the first year experience of alternative entry mature age students. International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 2(2), 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuciu, J., & Robertson, N. (2019). ‘That’s what you want to do as a teacher, make a difference, let the child be, have high expectations’: Stories of becoming, being and unbecoming an early childhood teacher. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(11), 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Wong, V. C., Krishnamachari, A., & Erickson, S. (2024). Experimental evidence on the robustness of coaching supports in teacher education. Educational Researcher, 53(1), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M., Francisco, S., Press, F., & Wong, S. (2020). Becoming a researcher: The process of ‘stirring in’ to data collection practices in early childhood education research. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 18(4), 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creasy, J., & Paterson, F. (2005). Leading coaching in schools. Leading practice seminar series. National College for School Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Dawborn-Gundlach, M. L. (2025). An investigation of alternative pathways to teacher qualifications in Australia. Education Sciences, 15(8), 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. (2023). Kindergarten funding guide. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/childhood/providers/funding/J641-Kindergarten-Funding-Guide-v6.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Department of Education. (2024a). Offer a teacher degree apprenticeship. United Kingdom Government. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/offer-a-teacher-degree-apprenticeship (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Department of Education. (2024b). Victorian teacher supply and demand report 2022. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Education Services Australia. (2021). Shaping our future: A ten-year strategy to ensure a sustainable, high-quality children’s education and care workforce 2022–2031. Education Services Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Gide, S., Wong, S., Press, F., & Davis, B. (2022). Cultural diversity in the Australian early childhood education workforce: What do we know, what don’t we know and why is it important? Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 47(1), 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S. (2010). Mentoring pre-service teachers: A case study. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 35(4), 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootenboer, P., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2023). The theory of practice architectures: Researching practices. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, F., & Andrews, R. (2015). “Because uni is totally different than what you do at TAFE”: Protective strategies and provisions for Diploma students traversing their first professional experience placement at university. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A., Burnheim, C., & Brett, M. (2016). Student equity in Australian higher education: Twenty-five years of a fair chance for all (A. Harvey, C. Burnheim, & M. Brett, Eds.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. (2017). Beyond the piece of paper: A Bourdieuian perspective on raising qualifications in the Australian early childhood workforce. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(5), 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J., Healey, B., Nolan, A., Moore, D., Kinnear, K., Ciuciu, J., Lanting, C., & Beahan, J. (2024). National professional practice network for educators and teachers: National children’s education and care workforce strategy, focus area 3-3. Australian Education Research Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervin, L., Mantei, J., & Neilsen-Hewett, C. (2025). Mentoring to build early childhood teacher capacity across career stages: The early childhood elevate mentoring program. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 50(1), 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokfors, L., Jyrhämä, R., Kynäslahti, H., Toom, A., Maaranen, K., & Kansanen, P. (2006). Working while teaching, learning while working: Students teaching in their own class. Journal of Education for Teaching, 32(1), 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsyuruba, B., & Godden, L. (2019). The role of mentoring and coaching as a means of supporting the well-being of educators and students [Guest editorial]. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 8(4), 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A., Richter, E., & Kempert, S. (2024). Student teachers as in-service teachers in schools: The moderating effect of social support in the relationship between student teachers’ instructional activities and their work-related stress. Teaching and Teacher Education, 146, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D., Morrissey, A., & Bussey, K. A. (2023). “I love the way we do it in early childhood”: Influence of an enhanced kindergarten placement on preservice teachers’ career choices. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 48(9), 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, E., Guarrella, C., & Madanipour, P. (2025). A university-stakeholder collaborative approach to designing early childhood mentor teacher training. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 24, 16094069251342537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, A., Ciuciu, J., Moore, D., Lanting, C., & Kinnear, K. (2025). Valuing the early childhood education workforce: Fostering and sustaining professional growth through induction and mentoring. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 46, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, A., & Molla, T. (2018). Teacher professional learning in early childhood education: Insights from a mentoring program. Early Years, 38(3), 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, R. M. (2014). Learn while you earn: Student teacher experiences of a learnership programme facilitated by open distance learning. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, J., & Eadie, P. (2019). Coaching for continuous improvement in collaborative, interdisciplinary early childhood teams (Vol. 44). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B. (2016). Teacher training by means of a school-based model. South African Journal of Education, 36(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, N., Cooke, M., Bussey, K., Mooney, A., & Blake, D. (2024). Reframing early childhood teacher education to support equity and access: The practice architectures of an enabling ‘degree-qualified’ pathway. In J. Burke, M. Cacciattolo, & D. Toe (Eds.), Inclusion and social justice in teacher education (pp. 177–197). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, I. (2019). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (5th ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, P. (2012). Mentoring and coaching for school teachers’ initial teacher education and induction. In S. J. Fletcher, & C. A. Mullen (Eds.), SAGE handbook of mentoring and coaching in education (pp. 201–214). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Steed, E. A., Strain, P. S., Rausch, A., Hodges, A., & Bold, E. (2023). Early childhood administrator perspectives about preschool inclusion: A qualitative interview study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52(3), 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]