Abstract

In this project, Anishinaabe artists and knowledge carriers worked with non-Indigenous classroom teachers to explore the cultural significance and mathematics of making wiigwaas makakoon (birch bark baskets). The artists spent two weeks in two grade 6 classrooms teaching students the process of basket making. They combined Indigenous pedagogy and intentionally designed inquiry tasks in order to generate mathematically related concepts. To make cultural–mathematical connections, we looked to Battiste’s characteristics of Indigenous pedagogy and explored how the learning that took place was holistic, part of a lifelong process, experiential, rooted in language and culture, spiritual, communal, and an integration of Indigenous and Eurocentric knowledges. Mathematically, students explored measurement with non-standard units, bisected angles without the use of a protractor, and explored the best way to optimize the capacity of their baskets. This work is an example of integrating Indigenous knowledge and heritage into elementary mathematics instruction.

1. Introduction

This article shares the joy experienced while engaging in mathematically related concepts through Indigenous pedagogy as students learned about Anishinaabe technology, design, and artistry while designing and creating a wiigwaas makak (birch bark basket). It is part of a larger series of projects with Anishinaabe and Métis leaders, artists, and educators, as well as non-Indigenous educators, to collaboratively explore connections between Anishinaabe or Métis cultural practices and the mathematics inherent within these practices. These projects, known collectively as “First Nations and Métis Math Voices”, have taken place in different community settings that are varied in terms of contexts and participants. Each individual project is developed at the local grassroots level and driven by the views, opinions, resources, and interests of participating communities. To make these cultural–mathematical connections, we identified relational protocols from Indigenous knowledge systems to build long-term relationships with communities that are grounded in respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility (Archibald et al., 2019; Kirkness & Barnhardt, 1991).

Current culturally responsive, or culturally sustaining, education focuses on students’ culture as a resource or asset and is responsive to students’ lived experiences, language, and contemporary cultural practices (Paris, 2012). This work takes many different forms, but a common focus is that mathematics education is grounded in place and community. In the conclusion of a volume on culturally responsive mathematics education, for example, the authors emphasize “living connections between community, culture and mathematics” (Nicol et al., 2020). Much of this work has been centred within Indigenous communities (e.g., Lipka et al., 2007; Lunney Borden, 2013; Nicol et al., 2013; Glanfield & Sterenberg, 2019). However, in our work, we were interested in how we might practice culturally responsive pedagogies within a diverse urban context while still supporting and sustaining cultural competence in participating students. For this article, we will outline the mathematics of creating a wiigwaas makak and use the characteristics for Indigenous Pedagogies created by Marie Battiste in 2013 as a framework to analyse the learning experience of students. We chose this framework because it provided several clear indicators/descriptors for what Indigenous pedagogies look like in action.

Situating Ourselves

Anika—Boozhoo nindinawemaaganidog, Mashkiki Oshki Waabigwan indigo anishinaabemong, Anika niin nindizhinikaaz zhaganaashiiimong, Anishnaabekwe indaaw, miinawa zhaaganash indaaw. Amik nindoodem, Wiikwemkoong nindoonjibaa, Animikii Wiikwedong indaa. Nindanokii gikinoo’amaagewikwe.

My English name is Anika, my father is Ojibwe/Odawa from Wiikwemkoong Unceded Indian Reserve; my maternal family is Settler Canadian. I am an Anishnaabe educator, now living and working in Thunder Bay. I have been working in the area of Indigenous Education since I started my teaching journey in the beautiful community of Eabametoong First Nation, a remote fly-in First Nation in Northwestern Ontario. I was raised in an urban setting; for the most part disconnected from my Anishinaabe community and culture. Since moving to Thunder Bay in 2010, I have been grateful to connect with the large urban Indigenous population here and build meaningful relationships with my relations from Fort William First Nation.

Ruth—I am a settler educator and math education researcher. I have been working with Indigenous community partners since 2012 to explore the mathematics inherent in cultural practices in order to make math meaningful for Indigenous students, and so that all students have the opportunity to learn from and with community and have experiences with Indigenous Knowledge systems. I have worked with school boards and First Nations schools across Turtle Island.

2. Materials and Methods

Cyclical Research Process

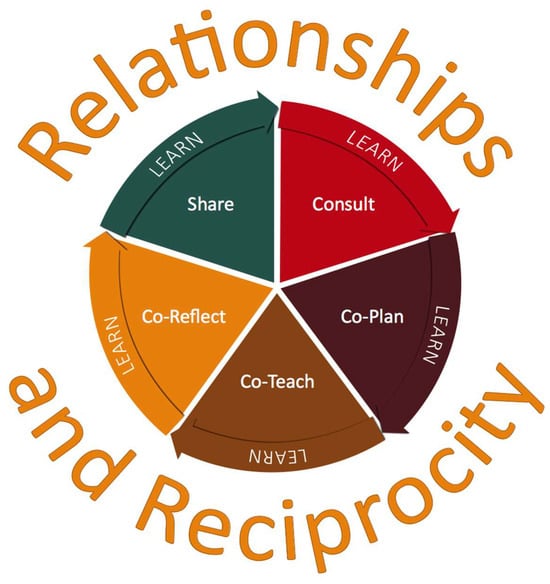

We have written about our research process in previous articles (Beatty, 2018; Beatty & Blair, 2015; Beatty & Ruddy, 2018; Beatty & Clyne, 2024; Beatty et al., 2024), which includes initial community consultations, co-planning, co-teaching, co-reflection, and sharing out the work in various forms, including workshops, papers, and reports to community (Figure 1). For this article, we draw from two different project cycles—Year 1 and Year 2—both of which took place in grade 6 classrooms.

Figure 1.

The cyclical research process.

For this project, we began with extensive consultation in our community of Animikii Wiikwedong, or Thunder Bay, located in Northwestern Ontario, on the homelands of the Anishinaabe of Fort William First Nation, signatory to the Robinson Superior Treaty of 1856. Elders, knowledge carriers, representatives from different Indigenous community organizations, Indigenous educators, school and system leaders and classroom teachers gathered to listen, share and guide us towards consensus on which piece of material culture we might want to explore through this research project in our area. Overwhelmingly, the consensus was that whatever we chose, the community wanted to ensure it was something that would allow for relationship building with Land.

Simpson (2014) introduces the concept of “Land as pedagogy” and shares about the Indigenous reality that many face of being displaced through reserves, cities, and towns and the importance of finding ways to “connect to the land and our stories and to live [Anishinaabeg] intelligences no matter how urban or how destroyed our homelands have become” (p. 23). The community group echoed these expressions. For them, as for Simpson, it is critical to “grow and nurture a generation of people that can thinking within the land and have tremendous knowledge and connection to aki” (p. 23). Many students and families attending school in Thunder Bay have connections to First Nations communities across Northwestern Ontario with strong family and community ties to Land-based practices. It takes time and many resources to access Land when you live in a city, which can be a barrier that results in a disconnection from Land for many students and families. After extensive discussions, community members who participated in consultation came to the decision to begin to explore the mathematics inherent in Birch Bark Basket, wiigwaas makak, making. Since wiigwaas makakoon (birch bark baskets) are made from materials harvested from the Land and their use and importance in our area have significance, it was an excellent fit. After our initial community meeting, Author 1 attended a workshop that was led by Levi Duncan, a former teacher in Muskrat Dam First Nation and birch bark basket maker. She made plans to attend, along with the math resource teacher from her Board, to start the process of learning and making mathematical connections. Author 1 shared with an Elder who was part of the initial community group that she would be attending this upcoming workshop. They pulled her aside and told her to be sure to pay attention to how Levi teaches, not just the processes and the steps of how to make a basket, but the ways he shares his knowledge. This small, yet intentional, comment opened her eyes, mind, and heart to seeing, deepening her understanding and truly valuing Indigenous pedagogical approaches and their importance in educational/instructional settings. It was a gift through this research process that the Elder gave from the very beginning to centre the how and not just the what within the process of learning this form of Indigenous technology and design.

Prior to getting into the classroom, we spent a co-planning day working with Indigenous artists and educators. In Year 1, we worked with Audrey DeRoy, Two Feathers, and in Year 2, we worked with Elliot Cromarty, Kaneebowich Mukwa, Elizabeth Moore, and Animki Benisi. All artists worked at Fort William Historical Park. During the co-planning day, the artists worked with classroom teachers and the researchers so they could learn how to make a wiigwaas makak and begin to explore the mathematical concepts inherent in creating a birchbark basket. This was also an opportunity to begin the fundamental process of building relationships between the artists and teachers.

Following the co-planning day, the artists joined the grade 6 classroom teacher and the researchers to engage in a two-week investigation of the mathematics inherent in creating a wiigwaas makak. Both years of the project took place in an elementary school in Thunder Bay, Ontario. The grade 6 classes comprised Anishinaabe, Anisininew and non-Indigenous students. The co-teaching was very fluid in structure and moved back and forth between teaching Anishinaabe culture, teaching the properties of the materials used, sharing cultural teachings connected to wiigwaas, and exploring mathematical concepts during the design and execution of making makakoon (baskets).

While the teaching and delivery of this research were carried out primarily in English, the interconnectedness of Indigenous Languages, worldviews and pedagogies was acknowledged from the beginning. We had first-language Anishinaabemowin speakers as part of the initial community consultation group. Questions surrounding whether we should describe it as “arts” or “crafts” were brought to the community group. Bruce Beardy, a first-language speaker, shared this description in Anishinaabemowin, Anishinaabewaadisiiwin Abajitaawinan gaye izhimaajiiwinan, or Indigenous technology and design in English. Throughout this paper, we use the term Anishinaabe(g) or Indigenous “artist(s)” when referring to Anishinaabe community members who carry the knowledge and teachings around the creation of the specific Indigenous design and technology that we were exploring, wiigwaas makakoon. Knowledge carriers are those community members who carry a range of Anishinaabe teachings and knowledges but may not have the skills required to make and teach about wiigwaas makakoon specifically. Throughout the co-planning and co-teaching, we continued to work with first-language speakers to include Anishinaabemowin vocabulary and terminology for mathematical concepts.

For this work, we were interested in the impacts that teaching mathematics through Anishinaabe design and technology, using Indigenous pedagogies, might have on student learning. Because this was an exploratory project, we adopted an inquiry-based approach (Artigue & Blomhøj, 2013), which has been shown to promote student engagement and sense-making as students invent mathematical concepts, in this case, through the creation of makakoon. We used open tasks, for example, inviting students to create a makak with the largest capacity, to offer opportunities for questioning, experimenting, and communicating in order to construct an understanding of abstract concepts like base, height, capacity and the interrelationship of these dimensions.

During the two-week process, we video recorded each half-day class, including cultural teachings by the artists and mathematical investigations by the students that were co-facilitated by the artists and classroom teacher. We also kept field notes of the classroom instruction and of the conversations between the artists, classroom teacher, and the authors after each class in preparation for the following day’s investigation. We photographed all aspects of the progression of learning to create makakoon, from the initial paper models through to makakoon created with wiigwaas.

The recordings were edited into specific learning episodes generated by the different activities. We wrote up each day’s investigation and included video clips, field notes, and photographs to create comprehensive summaries. These were then analyzed by the authors to identify mathematically related concepts, primarily geometry and measurement concepts, and for connections to Battiste’s Indigenous pedagogy framework. This article summarizes those analyses and was shared with the participating artists, who approved the contents prior to submission for publication.

3. Results and Discussion

In order to fully represent how investigating mathematical knowledge was intertwined with a framework for building cultural understanding, we present both the results and a discussion of this project in one section. In her book Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit, Battiste (2013) shares what came from the Aboriginal Learning Knowledge Centre with the Canadian Council on Learning (Ungerleider, 2007) from First Nations, Métis and Inuit leaders about the unique characteristics of “Aboriginal learning.” These include:

Learning is holistic;

Learning is a lifelong process;

Learning is experiential in nature;

Learning is rooted in Aboriginal languages and cultures;

Learning is spiritually oriented;

Learning is a communal activity;

Learning is an integration of Aboriginal and Eurocentric knowledge. (p. 181)

Through this project, we observed these characteristics along with other Indigenous pedagogical approaches that are supported by the literature, including expert–apprentice modelling (Beatty & Blair, 2015; Lipka, 2002; Lipka et al., 2007; Kisker et al., 2012; Beatty & Ruddy, 2018; Beatty & Clyne, 2024) with an emphasis on observation, individualized instruction, and a communal approach (Battiste, 2013, 2016). In sharing this research journey and the learning that came through it, we have chosen to organize our results into each of Battiste’s characteristics. Through the exploration of the mathematics inherent in making a wiigwaas makak, we learned about the strength of Indigenous pedagogy.

3.1. Learning Is Holistic

Indigenous pedagogy is holistic in that it emphasizes the need to address the intellectual, physical, emotional, and spiritual development of the student (Cajete, 1994; Barnhardt & Kawagley, 2005; Battiste, 2016). The activities the students engaged with when learning to make the baskets were not just intellectual in terms of honing their mathematical thinking. The experience also brought in physical, emotional and spiritual aspects of Indigenous pedagogy.

As we stated earlier, during the initial consultation with community, there was consensus among all stakeholders that these math projects should allow for relationship building with Land. Prior to the mathematical investigations in the classroom, the grade 6 students went out on the Land with the artists to visit birch groves and learn the proper techniques for harvesting wiigwaas in a way that does not damage the tree, including understanding the time of year this harvesting should be done. Animke described the correct way to harvest the bark:

You make your first incision as high as your chin. And then you cut [in a vertical line] upwards. We do not cut downwards—it would be so simple to cut downwards—but the reason we do not cut downwards is that we want to protect that beautiful tree from bugs and insects. So that first incision that we make that’s as high as our chin, you’re going to hear a loud snap sound [claps] like that. And what that is, is the release of pressure from behind that wiigwaas, that bark. It is the time when that sap is flowing from the roots of the trees going up through the trunk and out to its branches.

Students learned about the importance of wiigwaas in Anishinaabeg culture and examples of all the uses of the birch tree, such as making canoes, homes, drums, and medicine. Kaneebowich Mukwa outlined the properties of birchbark that make it such a versatile material.

Wiigwaas atik is a birch tree. To the Anishinaabeg people, this tree was a tree of life. It provided everything. Everything that you could imagine. It provided food, it provided baskets, spoons, snowshoes, and homes. There’s many different uses that we had for the bark of the tree [wiigwaas]. Trees this size, where you can put one arm around the tree, are good for craft work. Things like birch bark baskets, little canoes and that—but if you want something thicker you want a tree that you can barely get both arms around. The thicker bark we’re going to use for the construction of a home, for the construction of canoes, so something that’s a bit stronger and sturdier. The birch bark is one of the few trees in the world that has a horizontal grain to it, so, when you peel bark off of a birch tree it goes around the tree, whereas if you go to a cedar tree the bark goes up and down the tree. There’s also oils in the birchbark that makes it water repellent. And that’s why it’s very flammable and a good firestarter.

When creating the baskets, the students learned how to form a relationship with their piece of bark to determine how to shape it and how to respect the material when working with it. They learned that if it has knots, you cannot fold it on the knot or poke holes for sewing the corners together where the knots are. “You need to consider that it’s a piece of a living tree that has a life and a story of its own and, unlike paper, it’s not the same all over.” Animke showed the students that the smooth inside part of the bark usually goes on the outside of the basket because that is the way the bark naturally curls.

Kaneebowich Mukwa showed the students how to dip the pieces of bark in warm water to soften them so that they could be folded into the shape of a basket.

“It’s about being able to control the birchbark, being able to hold it effectively so that it doesn’t crack across because under these lines here, these lenticels, these are also weak points in the bark. If you try to fold along that there’s a chance it might just crack right open.”

The artists taught the students about the other materials from the Land involved in creating a makak, including spruce root (watap) for sewing the basket together and cedar for creating a strong rim.

Cedar is what we’re going to be using for the rim. It doesn’t always have to be cedar. Some people use thicker spruce roots for that. Some people also use red osier dogwood as well. You are going to trim up the sides of your basket, so it looks a bit more flush and even all around, because when you bend your cedar around, it’s going to be one straight strip. What you want to do when you’re sewing it is make sure it [the rim] is nice and flat and flush. You don’t want to have very loose stitches, otherwise it’s going to defeat the purpose of your rim.

When it came to creating baskets, the artists showed the students different basket designs and discussed the purpose of each. Even though one of our tasks was to create a basket that would “hold the most stuff” to explore the interconnected relationship between the dimensions of a basket, there is more to consider when creating a basket than what shape will have the greatest capacity. For example, when gathering berries, if the basket holds a lot of berries in a lot of layers, the berries at the bottom will get squished. For berries, a basket with a large base and shallow walls is better to prevent creating layers of fragile fruit, but the walls have to be high enough to prevent the fruit from spilling if the basket is dropped. On the other hand, for more robust gatherings, like nuts or pine cones, a basket with higher walls to allow for more “piling up” is appropriate (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Students examine different types of baskets used for different purposes.

Throughout the process of creating the wiigwaas makakoon, students were often reminded that the materials carried the spirit of the tree; as a result, they needed to consider the kind of energy they were bringing to that spirit while creating. They were taught that when or if they were getting frustrated trying to fold, or make holes, or sew the basket, they might start to put that negative energy into their creation. Student B had one difficult morning with their basket; it had cracked while they were putting a hole to sew, and it was starting to unfold, and they were getting visibly frustrated. One of the educators asked them how they were feeling and to consider what kind of energy they might be putting into his basket; they decided to take a break and go for a drink and a walk around. When they came back, they were feeling better and ready to work through the problems. When that student finished their basket, they held it up high above their head, so incredibly proud of what they had created, and also proud of how they had created it. This is one of the underrated skills you learn through engaging in the creation of material culture; it is a self-regulation process that requires recognizing your own emotions and addressing them so you can continue to create.

3.2. Learning Is a Lifelong Process

Everyone involved in this project—artists, students, teachers, and researchers—realized that Nishnabeg intelligence is for everyone. It is not just pedagogy; it is how to live life (Simpson, 2014, p. 18). Both the participating students and the adults learned about the importance of wiigwaas in Anishinaabe culture. Everyone learned that mathematics is embedded within Indigenous technologies and that this mathematics extends beyond paper and pencil calculations to also encompass harvesting wiigwaas, visualizing the shape of the makak within the sheet of wiigwaas, and creating art from sheets of bark.

The non-Indigenous classroom teacher and researcher and the Indigenous researcher/educator learned new ways of teaching. As an example, when Kaneebowich Mukwa first demonstrated bisecting the corners of a rectangular sheet of card stock to demonstrate how to centre the base and fold up the walls, Author 1 was not sure all the students had understood what he had done. During the break, she asked him to do a “think aloud”, that is, to describe every step of how to make the cuts and to describe what he was thinking as he did so. Kaneebowich Mukwa nodded, and then we headed back to the classroom. During the second demonstration of making the cuts, he said to the students,

“So just keep an eye on me, and see what I utilize and what methods I use to turn that [holds up sheet of paper] into this [holds up paper basket].”

He did not say another word. The students watched as he expertly cut the four corners and folded the walls up to make a perfect basket. He then walked around so every student could see the basket up close, with congruent sides—“nice, even walls.” Rather than explicitly describing his thinking and decision-making processes, Kaneebowich Mukwa put the onus back on the students to observe, make connections, and figure out the process for creating 45° angled cuts at each corner that were all the same length.

What we learned through documenting these projects over two years is that, even though we have developed a process for the inquiry, the learning changes and expands with each cycle. There is always more to learn and more to investigate each time we repeat the cycle. As Simpson (2014) writes, “you can’t graduate from Nishnaabewin; it is a gift to be practiced and reproduced” (p. 9).

3.3. Learning Is Experiential

As outlined below, we discovered that the students learned complex mathematical concepts and engaged in rich mathematical discussions through the process of creating their makakoon rather than the more Western approach of completing worksheets with memorized formulae. They experienced an entirely different knowledge system—one that was focused on the process of making and doing to build mathematical concepts.

In the following two excerpts from project interviews, participating students explained their perceptions of the project and how different it was from the math instruction they were used to. They also compared and contrasted a Eurocentric way of learning and teaching math and an Indigenous approach that was more about knowing the materials, relying on innate spatial reasoning skills, and building a level of mastery from a sequence of experiences. The first student, M, is Anisininew and explained the importance of having math taught through familiar cultural practices when he was interviewed by the classroom teacher.

It was good to learn about how the First Nations lived, making the basket. It’s just a fun experience to make it in school. I feel like we’re connecting with the First Nations and learning about their culture more and I’m really fascinated—like fascinated! I feel like I’m really connecting about where I was born because I’m Oji-Cree and it feels like I’m really connecting with my culture and it feels like how I learned it, and my Mom learned it. [We then talked about how the project is ending and the artists would no longer be visiting the classroom daily]. That’s actually really sad for me because I feel like we connected so much over the weeks, and I really loved the First Nations helping us, building stuff, hands-on experience.

M ended by saying that he wished that the teachers would make connections to Indigenous culture in all aspects of their teaching, not just when introducing new concepts in mathematics. His comments highlight the importance of bridging the lived experiences of Indigenous students with concepts of mathematics curricula (Ruef et al., 2020).

The second student, P, is non-Indigenous and spoke about how much she enjoyed the experience and how different the approaches the artists and her classroom teacher took when they were co-teaching.

It was actually pretty funny because they had completely different outlooks on math and ways to make the baskets. Two Feathers, she would cut and just kind of eyeball it, and Mr. Sandberg was like, ‘ok, you’ve got to measure it carefully so it’s perfect’ and I just thought it was really interesting. I learned that everything needs to be treated with respect. And I learned a lot about patience because folding the birchbark was…crazy! [Holding her basket]. I can’t even believe this was a piece of birch bark on a tree, and now it’s a piece of art. I’ve never done anything like this before.

3.4. Learning Is Rooted in Indigenous Languages and Cultures

“Oral storytelling becomes an even more important vehicle for the creation of free cognitive spaces, because the physical act of gathering a group of people together within our territories reinforces the web of relationships that stitch our communities together.” (Doerfler et al., 2013, p. 281).

All of the artists began the projects by focusing on the cultural connections of this work and told stories about the history of wiigwaas and designing and constructing makakoon. For example, Audrey showed students some of the materials the tools would have been made out of historically. The awl, for instance, used to punch holes in the wiigwaas to make sewing the basket together easier, would have been made out of muskrat bone or a caribou splinter bone. “We would sharpen the bone with a rock. Anything that was exposed on the ground we would harvest and make tools out of.” Animke Benisi explained how the birchbark got its distinctive horizontal marks, “burn marks”, by telling a Nanabozho tale about waabooz (rabbit) and animikii (thunderbird).

We also worked with an Ojibwe language teacher to bring the language into math class. First, we focused on translating the materials—wiigwaas for birchbark, makak for basket, and watap for spruce root. We then began to discuss our long list of “mathematical concepts” and how these could be translated. During the second cycle of this research, we were lucky to have a group of educators who were first-language speakers of Ojibwe visit the classroom while we were making baskets. We shared a few of the key mathematical terms (i.e., base, width, height, etc.) in English with this group of speakers and asked them for translations in Ojibwe. At first, the group looked at the list and had nothing to say, so we thought we might not get those translations. As it turned out, the speakers needed the evening to discuss those mathematical concepts before being able to share them with us. When they returned the next day, they had a few translations for us that enhanced student understanding of the mathematical concepts that can seem abstract to students. For example, they shared a word for base—ka’iishiiyatek, which they shared literally translates to “it’s where it sits” in their dialect. This provides a visual for what the term “base” means, which helps students better understand that term.

This work is about highlighting the complex mathematics of Indigenous cultural practices, but it is also about lifting up and prioritizing Indigenous Knowledges and the profound effects this can have on Indigenous students. Elder Rita Fenton from Fort William First Nation summarized her perspective on this work when she came to visit the classroom:

What it is about culture, for me, it’s a way of life. And the thing that was missing in my life was my identity. My identity because I didn’t know who I was. When I danced in a circle for the first time in my life and I felt that connection to who I am as a Native person. It was missing, that was missing. And so many of our children in schools—if they were anything like me, they didn’t know—didn’t have an identity. The children are our future generation, and if we teach them at a young age about this [their culture] they will have that pride and dignity as Anishinaabe people. I’m so glad this is being taught in the schools and there should be more of it. Then you’ll have that understanding of where we come from and the problems that we have had to survive and go through. And still walk and be proud.

3.5. Learning Is Spiritually Oriented

One of the properties of Indigenous pedagogy that Battiste lists is that learning is spiritually oriented. As we went through the projects, one recurring theme was the connections the artists made to the spirit of the birch tree—wiigwaas atik—and connections to aki, the Land. In addition to learning about wiigwaas from a cultural and practical perspective, students also received teachings from Animke that were spiritual in nature.

“Those birch trees are going to be harvested in the months of June and July. Before you go harvesting your bark you will always state to the tree why you are there and the purpose you are going to use for that birch bark. So, you will have your basket offering and your semaa (tobacco). And then you proceed to harvest the bark.”

Kaneebowich Mukwa reiterated the teachings and, like Animke, made connections to the importance of offering gratitude, the sustainable nature of the harvest, and the importance of expressing gratitude for the material, including sharing the intended use of the wiigwaas with the spirit of the wiigwaas atik. He also emphasized the importance of using the material effectively, which was a theme throughout the project as students learned the correct way to create their baskets using geometry to minimize wasting the birch bark.

When we go to harvest materials or harvest animals, we’re giving thanks and we’re also stating our purpose of what we’re harvesting and what we plan to use it for. This is very important that we’re acknowledging the spirit of the birch tree or the spirit of the animals—that we know what their use is going to be and it’s important that they know that because the spirit of that birch tree continues to live on in this birch bark. We still have to continue to treat it with respect and use it as effectively as we should.

Battiste speaks about the importance of “releasing the focus of the mind, and through relaxation and de-stressing, it opens the mind, body, heart, and spirit to a peace of mind” (Battiste, 2013, p. 182) in order to release the learning spirit. In this work, we noted the wholehearted engagement of students as they focused on finding and centering the base, creating their cuts, and ensuring minimal waste because this learning was grounded in Anishinaabe culture. Mathematics was utilized as a way of creating something beautiful—“a piece of art”—and students were encouraged to experiment, explore, and learn from their or their peers’ mistakes.

3.6. Learning Is a Communal Activity

From the outset, this project was conceived as a communal project driven by community and involving Anishinaabeg artists, Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators, Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, and the researchers. This was a new experience for everyone, and each day, students worked together to pool their knowledge in order to develop the collective expertise of the classroom. They generated a number of questions to investigate as they began to learn how to construct baskets.

- How can we be sure our walls are the same height?

- Should the diagonal cut at each corner pass through the centre of the paper?

- What is the optimum angle of the cut at the corners to get even walls?

- What does the cut create?

- Which of these walls would be higher? Paper with a small rectangle in the middle and long diagonal cuts, or paper with a large rectangle in the middle and short diagonal cuts?

- Would the walls be the same height if you had a square base?

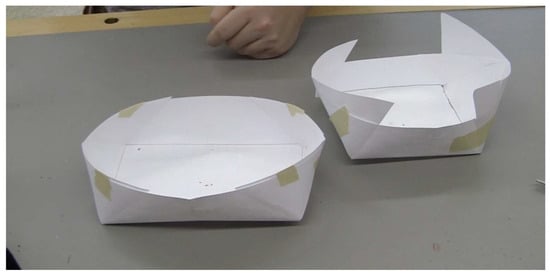

The last question resulted from the experiences of a number of students whose baskets had wildly incongruent walls (Figure 3). As a reminder, the students learned how to create walls by (1) creating a smaller rectangle in the middle of the sheet of paper that was similar to the dimensions of the paper, and (2) making 45° cuts at the corners and then folding up and taping the corners. To understand why some baskets had uneven walls, the students worked together with the artists to collectively problem-solve.

Figure 3.

The basket on the left has a rectangular base and even walls; the basket on the right has a square base and uneven walls.

“See the angle being cut there [on the basket with walls of different heights]. That’s the difference. We have a pretty close to perfect square in here [at the base of the basket on the right] and that’s why the angle we cut in is a little different. And that’s why we have this big tail sticking out here [one of the higher walls] just because they’re two different lengths from the side of the paper.”

In group discussions, students shared with each other their approaches, informal tools, noticings, wonderings, and “a-ha” moments, which were nourished by the apprentice model the artists used to work in close proximity to each individual student.

One beautiful thing we witnessed through this process was a continuous shift in who the “experts” in the room were. At times, when we were discussing and naming mathematical formulas, such as how to find volume, the classroom teacher led as the expert. The artists were the experts modelling how to work with the wiigwaas. Through the inquiry-based learning design, students often became the experts and shared with the group how they found centre, or how they decided where to make their diagonal cuts. Students were constantly demonstrating new ways of doing things that brought out different mathematical understandings for the group. During each stage of the learning—in the mathematically related concepts or in creating the baskets—different students would grasp the learning faster, and inevitably they would turn to help a peer who had not yet fully understood. We also found that students who were often disengaged in learning at school, or who struggled with mathematical concepts, grasped the concepts through the hands-on nature of the activities and led discussions about mathematics. A parent of student E reached out and shared how grateful she was that their child was “actually enjoying math” and that “their ideas and creativity were being celebrated” in the classroom.

3.7. Learning Is an Integration of Aboriginal and Eurocentric Knowledge

Teaching math through the design and creation of wiigwaas makakoon enabled students and teachers to make the connection between the artists’ knowledge of creating baskets and the mathematics found in the provincial curriculum. “As Indigenous Peoples we can master the Western curriculum, but we also need to honour our Indigenous languages, knowledges, and wisdoms. They bring life back into what we are doing through schooling.” (Steinhauer et al., 2020, p. 80).

3.7.1. Finding the Centre of a Rectangle

At the beginning of the project, when students were initially learning how to create makakoon, they practiced with paper and then card stock before finally working with wiigwaas so as not to waste this precious material. The math that surfaced as students learned about creating their makakoon reflected the process that skilled artists use and was explicitly connected to cultural teachings, for example, that precise measurements are required to minimize wasting wiigwaas. We began by finding the centre of a rectangular piece of paper. Finding the centre of the piece of bark is essential because the symmetrical dimensions of the basket are built out from the centre. The students were asked to find the middle of a rectangular piece of paper and put a dot at the centre. Kaneebowich Mukwa explained it as “giving you a visual sense of how much material you need, because you need to be able to estimate with just your vision. Just using your eyes and a pencil, create a little dot in the centre.” The purpose of this central point is to help students create a smaller version of the rectangular piece of paper as the base of the basket, basically a dilation of the original sheet that is proportionally similar and centred. The bigger message was one that resonated throughout the project—that it is important to respect the materials and not waste any of the wiigwaas. If the base is not centred, and is not symmetrical, the sides of the basket will be uneven and will need to be trimmed. Trimming the sides means wasting the wiigwaas, so finding centre is important to minimize wasting any of the bark from the precious tree of life, wiigwaas atik.

Students used different methods to find the centre. Many used a pencil as an informal measuring tool because, as Kaneebowich Mukwa pointed out, they likely would not have rulers with them in the bush when making a makak. Student B, for example, used her pencil to measure from the top edge of the paper and put the point of the pencil where she thought the centre was. Then she put her fingers on the pencil at the top edge of the paper and, not moving her fingers, used that measurement (from pencil tip to her fingers) to measure from the bottom edge of the paper up to the centre.

Other students used different techniques to “eyeball” the centre. Student S moved her fingers together from the outer corners at the top of the page towards the middle to find the vertical centre of the page and then moved her fingers together from the top and bottom edges to find the horizontal centre. Her reasoning was that finding the vertical and horizontal middle would help her find the middle of the paper.

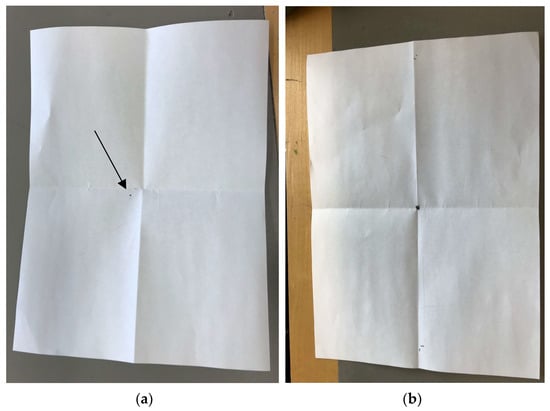

Finding center by “eyeballing the paper” is an important skill to learn because birch bark cannot be folded in half horizontally and vertically without cracking the bark. However, once the students marked the centre of their paper, we asked them to fold it in quarters to check their estimates. Most of the students were off by quite a bit at the beginning, but after a few tries, their estimates got very close to the actual centre, which demonstrated their developing ability to visualize partitioning the rectangular space vertically and horizontally (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Checking the estimates of “eyeballing” the paper to find the centre by folding it in half vertically and horizontally. On the left (a) is an early estimate with the initial dot indicated by an arrow, and on the right (b) is a later estimate by the same student, showing an improvement in the ability to visually partition the rectangular paper.

3.7.2. Finding the Base of the Basket

Kaneebowich Mukwa next demonstrated how to take that idea of finding the centre of the paper and extend it.

“We’re going to take that concept of finding centre, and we’re going to make it bigger. So, what we’re going to try to do now is find a rectangle centred within another rectangle. So instead of one point, you’re going to find four points.”

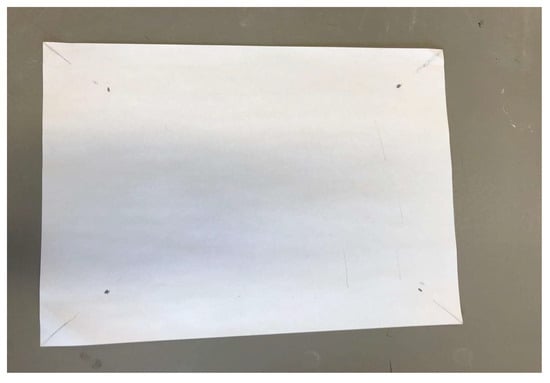

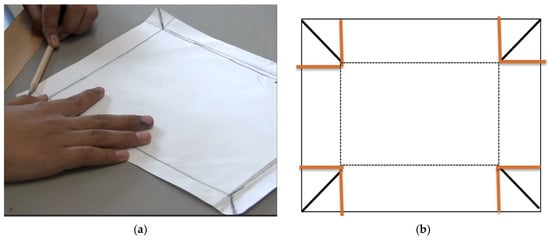

The four points represented the four corners of the smaller, dilated rectangle, which would become the base of the basket. Again, students “eyeballed” where they thought the points should go and used various techniques and non-standard measuring tools to determine the points (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Estimating the four points of the corners of a smaller rectangle, which represents the base of the basket.

Once students found the points, Kaneebowich Mukwa explained that they would need to make diagonal cuts from each corner of the paper to each of the points so that the edges of the paper could be folded up to form the sides, or “walls” of the basket. [Note: The students began referring to the sides of the 3-dimensional basket as “walls” to differentiate them from the edges of the two-dimensional paper.] The angle of these cuts was important. If the cuts were not bisecting the 90° angle of the corners at 45°, then the walls of the basket would not be even and would have to be trimmed, which would waste the wiigwaas. Creating precise cuts of 45° ensured that the sides of the basket would be congruent (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Students used informal tools to determine how to bisect the 90° corners of the paper to create cuts of 45°.

Kaneebowich Mukwa explained why the precision of the cuts was so important. “When we’re using our materials, we’re trying to find ways to minimize our waste. So, it’s the ways of how we cut, how we fold, how we measure, and maximize what we have to use it for the purpose we need.” He demonstrated how to make the cuts and folds for the basket and asked the students to pay careful attention to exactly what he did. After the demonstration, the students identified some of the things they noticed:

- Kaneebowich Mukwa was very focused and concentrated on making even cuts;

- He folded the sides up after the cuts were made to check the height of the walls and how well all the sides lined up;

- He used the length of the scissors to measure the length of the cuts to make sure they were all the same length.

The students then cut the corners of their pieces of paper. One student, K, said that she knew that when she cut each of the corners of the paper, there had to be the same amount of paper on either side of her scissors.

Another student, S, drew diagonal lines and then drew squares around them to ensure he was bisecting the 90° angle of the corner by ensuring that each square was divided into two equal halves. He then drew lines from the bottom of each diagonal line to check whether the walls of the basket would be the same height (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Student K’s method of ensuring the cuts at each corner were at a 45° angle, and that the sides or “walls” of the basket would each be the same height (a). A diagram of how the student created the cuts (b).

3.7.3. Ordering Baskets “Smallest to Largest” (And Refining Our Ideas of “Smallest” and “Largest”)

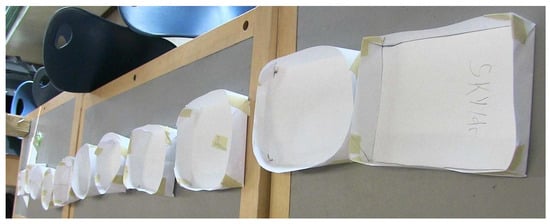

Once students made the diagonal cuts to the four corners and taped the corners of their baskets to form the walls, they were asked to order the paper baskets “from smallest to largest” with no further stipulations. We were interested to find that most students, at this point, focused on the size of the base of the basket and ordered them from smallest to largest base (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Students initially ordered their baskets “from smallest to largest” by focusing on the area of the base of the baskets.

This comparison of different baskets led to a discussion about the relationship between the length of the diagonal cuts, the size of the base, and the height of the walls, with the conclusion that longer cuts created higher walls and a smaller base.

From here, we asked the students to construct a basket that they thought would hold the most stuff (in this case, soy nuts). Essentially, we wanted the students to create a basket that they believed would have the greatest capacity in order to integrate an understanding of capacity with their understanding of the relationship between base and height. Some students predicted that all of the baskets would hold about the same amount because they were all using the same size sheet of paper. Some students conjectured that baskets with higher walls would hold more because they resembled popcorn boxes. Others hypothesized that a shallow box would hold the most because it would have the biggest base.

Once the students created these baskets, we filled each basket with soy nuts and then used identical measuring cups to be able to compare the capacity of each basket. The students ordered the baskets, this time by capacity, and found that (1) not all of the baskets held the same amount of soy nuts, even though they were all created using the same size of paper, and (2) the baskets with the largest base or highest walls did not necessarily hold the most. In fact, the students observed that the baskets that had “medium walls”, or were “in the middle” with respect to the size of the base and the height of the walls, held the most soy nuts.

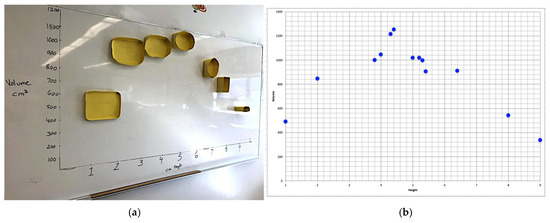

3.7.4. Ordering Baskets by Height

We asked the students to re-order the baskets, but this time by the height of the walls (Figure 9). For this activity, we included baskets that we had created with walls of 1 cm, 2 cm, 8 cm, and 9 cm, which we filled with soy nuts in order to compare the baskets by height and include extremely short or tall basket walls. The baskets on either end of the lineup (1 cm, 2 cm, 7 cm, 8 cm, 9 cm) held the fewest soy nuts, while the baskets in the middle with a height of 4.3 cm to 4.4 cm held the most.

Figure 9.

Students lined up the baskets by the height of the “walls”, with shallow baskets on the left progressing to taller baskets on the right. The “medium” baskets in the middle held the most soy nuts.

The relationships among base, height, and capacity are less straightforward than that between height and base, but seeing the visual representation of this relationship in baskets and cups of soy nuts helped students to explain their understanding. The following is the explanation from a grade 6 student:

If the basket is too big (high walls) or too small (shallow walls) it’s not going to hold much. To hold a lot, you have to be in between small and big (shallow and tall). I think that is because if you have a height of just a little bit, then you have a big base. You can fill up the base, but you can’t do more layers. If you have higher walls then it will be a smaller base, but you can fit more layers. [Picks up a very shallow basket]. Look at these tiny, tiny walls. You can’t pile up more layers. So, you don’t want that. You also don’t want it like this [basket with tall walls] where there’s no base. There’s no base! So even though you can stack, there isn’t much to stack up. But look here [basket with medium walls] you can fit quite a bit inside and you can also stack those layers up. So, I think this is pretty good.

When we calculated the volume of each basket and created two graphs showing the relationship between volume (vertical axis) and the height of the walls (horizontal axis), students could see the same rough bell curve that mirrored what they had observed in the measuring cups of soy nuts (Figure 10). We created one graph by calculating the volume of different card stock baskets and physically placed them on a graph on the whiteboard. The other graph was generated using Excel. The curve is not perfect because the students were creating baskets rather than rectangular prisms, but the shape of the data led to some interesting discussions about the relationship between the base, the height, and the capacity or volume of the baskets.

Figure 10.

Two graphs, one using actual baskets (a) and one generated by Excel (b), showing the relationship between height in cm (horizontal axis) and the volume/capacity of the basket (vertical axis).

In making baskets, students explored transforming two-dimensional surfaces into three-dimensional figures, which is an essential part of developing spatial sense. In this work, we did not introduce students to formulas for calculating capacity of length × width × height. Past research (Owens & Outhred, 2006) has shown that students who are taught to focus on the formulas and numerical operations required in calculating the volume or capacity of a rectangular prism tend to ignore the structure of the figure or have little understanding of how the formulas relate to the figure. In this work, students created baskets to develop an understanding of the relationship between the base and height of the basket—as the height of the walls increased, the size of the base decreased. This then led to an exploration of the relationship between base and height and capacity and how to optimize the capacity of a rectangular prism. Instead of memorizing formulas, these students engaged in activities that brought together visual–spatial explorations of 2D shapes and 3D figures. And although these grade 6 students were not finding the derivative for the height of the box, they did construct a good understanding of the “tipping point” of increasing height leading to increased capacity up until the walls were a little over 4 cm high, and then found that after that, the higher walls did not make up for the reduction in the base.

We also involved a great deal of visualization by creating opportunities for students to develop their abilities to find the centre of a rectangular space (paper, card stock, or wiigwaas) and to practice bisecting right angles in order to create dilations of rectangles within larger rectangles. All of this was done initially without the use of any formal measuring tools and with an emphasis on imagining these movements prior to cutting and folding. These activities tapped directly into students’ spatial abilities, which are forms of mental activities that enable individuals to create spatial images and manipulate them when solving problems (Pittalis & Christou, 2010).

During the second week of the project, the students were each given a sheet of wiigwaas and learned the stages of creating a makak, based on the explorations they had carried out with paper and card stock. The artists began by showing the students how to cut and fold the bark into a basket shape, just as they had been practicing with paper and card stock. Then, instead of taping the corners together, the students learned how to poke holes on either side of the folded-up corners with an awl and use spruce root to stitch them together. Finally, the students learned how to create rims for the basket by bending strips of cedar around the top, one on the inside and one on the outside of the top edge of the basket, and then sewing around the cedar rims with spruce root to hold the rims in place. (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

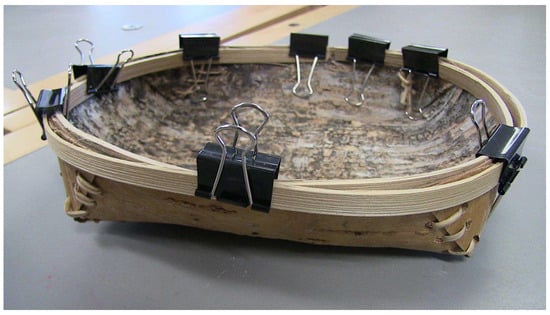

Figure 11.

Clips hold the cedar rims in place. The corners of the makak have been stitched together with spruce root.

Figure 12.

Finished makak with the cedar rims stitched to the makak with spruce root.

4. Conclusions

This project is an example of integrating Indigenous Knowledges into mathematics instruction. For the Indigenous students, it was an important step to celebrate their heritage and center Indigenous ways of knowing in a context that is, unfortunately, usually profoundly Eurocentric. This was a two-week project set within the larger provincial school system. For those two weeks, we lifted up Indigenous voices, prioritized Anishinaabeg culture, and focused on the design, artistry, and technology that developed through working with materials harvested from aki since time immemorial. This project opened the way for a reconceptualization of what mathematics instruction can be—holistic, experiential, cultural, spiritual, and communal. We also experienced the “vitality, energy, vision, and purpose” (Battiste, 2013, p. 181) that happens when real, enthusiastic learning takes place.

Battiste (2013) calls for the revitalization of Indigenous Knowledges in education, and our project extends her work within mathematics education by demonstrating how mathematics is transformed when Anishinaabeg pedagogies are centred. Rather than adding Indigenous perspectives into a Eurocentric discipline, this project demonstrates how teaching mathematics can become relational, land-based, and culturally grounded, moving beyond inclusion towards epistemic sovereignty, and provides a model of how Indigenous Knowledges can reshape mathematics learning. We hope this project will lead to opportunities for Indigenous Knowledges to be foundational in the learning experiences of all students, and that we can progress from two-week projects to a fully culturally sustaining approach to mathematics education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing–original draft preparation, project administration, A.G. & R.B.; writing–review and editing, R.B. & A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, grant number 430-2013-000483.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Lakehead University (protocol code 077-12-13, file 1462965—2015) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the vulnerable nature of the population.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by Lakehead District School Board and Fort William Historical Park.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Archibald, J., Nicol, C., & Yovanovich, J. (2019). Transformative education for Aboriginal mathematics learning: Indigenous storywork as methodology. In Decolonizing research Indigenous storyworks as methodology (pp. 72–88). Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Artigue, M., & Blomhøj, M. (2013). Conceptualizing inquiry-based education in mathematics. ZDM—The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 45(6), 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhardt, R., & Kawagley, A. O. (2005). Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska Native ways of knowing. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 36(1), 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Battiste, M. (2016). Research ethics for protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: Institutional and researcher responsibilities. In Ethical futures in qualitative research (pp. 111–132). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, R. (2018). Connecting algonquin loomwork and western mathematics in a grade 6 classroom. In T. Bartell (Ed.), Toward equity and social justice in mathematics education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, R., & Blair, D. (2015). Indigenous pedagogy for early mathematics: Algonquin looming in a grade 2 math classroom. The International Journal of Holistic Early Learning and Development, 1(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, R., & Clyne, C. (2024). Relationships and reciprocity in mathematics education. In A. King, K. O’Reilly, & P. Lewis (Eds.), Unsettling education: Decolonizing and indigenizing the land. Canadian Scholars. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, R., Clyne, C., Muma, L., Parkinson, J., & Sears, B. (2024). Developing computational thinking using LYNX for loom beading designs in grade 5. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 24(2), 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, R., & Ruddy, C. (2018). Mathematics exploration through algonquin beadwork. In M. Sack (Ed.), My best ideas. Rubicon. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of indigenous education. Kivaki Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doerfler, J., Stark, H. K., & Sinclair, N. J. (Eds.). (2013). Centering Anishinaabeg studies: Understanding the world through stories. University of Manitoba Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glanfield, F., & Sterenberg, G. (2019). Understanding the landscape of culturally responsive education within a community-driven mathematics education research project. In Living culturally responsive mathematics education with/in indigenous communities (pp. 71–90). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness, V. J., & Barnhardt, R. (1991). First nations and higher education: The four Rs–respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education, 30(3), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kisker, E. E., Lipka, J., Adams, B. L., Rickard, A., Andrew-Ihrke, D., Yanez, E. E., & Millard, A. (2012). The potential of a culturally based supplemental mathematics curriculum to improve the mathematics performance of Alaska Native and other students. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 43(1), 75–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipka, J. (2002). Connecting Yup’ik Elders knowledge to school mathematics. In M. de Monteiro (Ed.), Proceedings of the second international conference on ethnomathematics (ICEM2). CD Rom, Lyrium Communacao Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Lipka, J., Sharp, N., Adams, B., & Sharp, F. (2007). Creating a third space for authentic biculturalism: Examples from math in a cultural context. Journal of American Indian Education, 46(3), 94–115. [Google Scholar]

- … & Lunney Borden, L. (2013). What’s the word for…? Is there a word for…? How understanding Mi’kmaw language can help support Mi’kmaw learners in mathematics. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 25, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C., Archibald, J.-A., & Baker, J. (2013). Designing a model of culturally responsive mathematics education: Place, relationships and storywork. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 25, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C., Archibald, J.-A., Glanfield, F., & Dawson, A. J. S. (2020). Living culturally responsive mathematics education with/in indigenous communities. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, K., & Outhred, L. (2006). The complexity of learning geometry and measurement. In A. Gutierrez, & P. Boero (Eds.), Handbook of research on the psychology of mathematics education: Past, present, and future (pp. 85–115). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittalis, M., & Christou, C. (2010). Types of reasoning in 3D geometry thinking and their relation with spatial ability. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 75, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruef, J., Jacob, M., Walker, G. K., & Beavert, V. (2020). Why Indigenous languages matter for mathematics education: A case study of Ichishkíin. Education Studies in Mathematics, 104(3), 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer, D., Cardibal, T., Higgins, M., Madden, B., Steinhauer, N., Steinhauer, P., Underwood, M., Wolfe, A., & Cardinal, B. (2020). Thinking with Kihkipiw: Exploring an Indigenous theory of assessment and evaluation for teacher education. In S. Cote-Meek, & T. Moeke-Pickering (Eds.), Decolonizing and indigenizing education in Canada (pp. 73–91). Canadian Scholars. [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider, C. (2007). The Canadian Council on Learning, Canada. In Evidence in education (pp. 81–86). OECD. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).