Abstract

The integration of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools has become a game-changer in educational practices, particularly in collaborative academic writing. This study explores gender-based disparities in perceptions, emotions, and self-efficacy regarding students’ utilization of AI tools during a collaborative Wikibook writing project. Grounded in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the research investigates how male and female undergraduates in Hong Kong perceive the usefulness and ease of use of ChatGPT 3.5 and Padlet AI image generation function, as well as their emotions and self-efficacy when engaging with these tools. Using a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire and an independent sample t-test, the study compares gender perspectives with a sample size of 140 undergraduates. The results reveal that (1) both genders found the AI tools beneficial for language polishing and essay reconstruction in academic writing; (2) both genders experienced a range of emotions, including enjoyment, satisfaction, frustration, anxiety and tension during the writing task; (3) both male and female students demonstrated AI literacy to critically evaluate AI-generated information. These findings underscore the importance of fostering an equitable and engaging approach to AI-supported learning environments for both genders. The study highlights the benefits of AI tools in enhancing learning outcomes and emphasizes the role of students’ AI literacy in ensuring the responsible and effective use of these tools as learning partners.

1. Introduction

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) tools into educational contexts has profoundly reshaped the education landscape, endowing students with innovative ways to enhance their learning efficacy and outcomes (Zheng et al., 2023; N. Wang et al., 2024). Among these advancements, multimodal generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and Padlet’s AI image generation functions can generate visual and textual content for students’ language learning in an engaged manner (L. Jiang & Lai, 2025), not only in feedback for revision, but also as a multimodal environment with visual representation in fostering students’ critical thinking (Lin et al., 2025). However, since these multimodal technologies have been deemed effective pedagogy in improving writing skills and critical mindset (Liu et al., 2024), it is crucial to explore how diverse groups of students perceive and interact with them, particularly from a gender perspective.

Gender disparities in their attitudes and responses to educational technologies have been widely documented, with research suggesting that males and females exhibit divergent attitudes, behaviors, and emotional responses towards technology adoption (Cai et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2020; Svenningsson et al., 2022). Societal gender expectations and early exposure to technology play a key role in shaping how males and females interact with educational technologies (Whitley, 1997). A significant factor contributing to gender differences in technology use is the distinct socialization of men and women based on traditional gender roles. These gender role beliefs reflect perceptions about the characteristics and appropriate behaviors of men and women (Prentice & Carranza, 2002). Such variations ultimately shape students’ overall engagement and their academic performances (Hanham et al., 2021). Despite the growing interest in leveraging AI in education, there remains a lack of nuanced understanding of how gender differences affect students’ perceptions of these tools, as well as their experienced emotions and self-efficacy in using them. By addressing this gap, this study contributes to more inclusive pedagogical strategies that maximize the benefits of AI for all learners.

Grounded in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), this study aims to investigate gender-based variations in perceptions, emotions, and self-efficacy related to the use of ChatGPT 3.5 and Padlet AI image generation function in collaborative academic writing. A 5-point Likert questionnaire with 42 items was adopted to capture their perceptions. Through independent sample t-tests, this research seeks to uncover critical insights into the gendered nuances of AI adoption in higher education context.

By exploring these dimensions, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how generative AI can be integrated into teaching and learning in a more equitable and engaging manner. The findings have the potential to implicate educators and policymakers in higher education institutes on how to design and implement technology-enhanced pedagogical approaches that cater to diverse student needs as well as cultivating their computational thinking when using AI, fostering a balanced and inclusive learning environment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

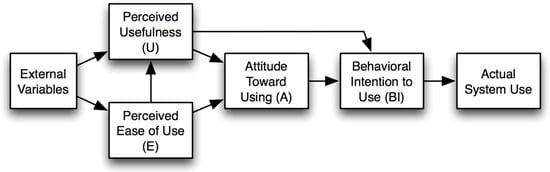

TAM (Figure 1) is a widely used theoretical framework for understanding how individuals adopt and use new technologies, emphasizing the influence of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) on user behavior. While several competing models exist for analyzing technology adoption, including the UTAUT and TPB, TAM was selected for this study due to its streamlined focus on perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) as predictors of user behavior. Unlike UTAUT, which incorporates numerous external variables, TAM offers a minimalist yet powerful framework to investigate the nuanced relationship between gender and generative AI tools in learning tasks. Extended from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), Davis (1989) streamlined this framework to be more specific to the context of information technology, focusing on two key perceptual variables: Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). The former one is defined as the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her performance while the latter one refers to the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort (Davis, 1989). According to the model, both PU and PEOU directly influence a user’s Attitude Toward Using the technology. Critically, PEOU also has a direct positive effect on PU, suggesting that the less effort a technology requires, the more useful it is perceived to be. These factors form a joint impact in shaping the user’s Behavioral Intention to Use, which is the most direct predictor of Actual System Use.

Figure 1.

Technology acceptance model (Davis, 1989).

2.2. Multimodal Generative AI in Higher Education Contexts

Unlike traditional writing, which primarily relies on texts, multimodal writing integrates visual, auditory, and spatial elements to deliver information, creating a richer and more engaging experience for both authors and the audience. In higher education contexts, with GenAI tools shaping the educational landscape with accessible resources within limited time, multimodal writing has become an important approach in assessment as it requires leaners to engage with their multimodal writing components and organize these elements in a critical and coherent manner. AI text generators such as ChatGPT (N. Wang et al., 2024; L. Wang & Ren, 2024) and AI image generators such as DALL⋅E and Midjourney (Liu et al., 2024; Kang & Yi, 2023; Wei et al., 2025) can be creative tools that influence and enrich students’ existing composition process. In such multimodal composition processes, GenAI’s effectiveness lies in its capability to generate ideas with less time and energy and expand students’ creative expressions by providing an enjoyable experience in multimodal writing (J. Jiang, 2024) as well as fostering reflective thinking skills, particularly in problem-solving and adaptive decision-making processes (Wei et al., 2025). Despite these affordances, some limitations of GenAI-assisted multimodal writing were also highlighted. The unsatisfying visual outcomes with unrealistic features produced by AI image generators are inconsistent with students’ original intentions and disrupt the coherence of the writing flow (J. Jiang, 2024). Another highlighted concern is overreliance on AI-generated information, which may compromise learners’ autonomy, critical thinking, and innovation (Duhaylungsod & Chavez, 2023; Zhai et al., 2024). AI’s propensity to fabricate so-called misinformation (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2023) is also under serious concern, urgently calling for the awareness of critical literacy when engaging with AI tools (Arseven & Bal, 2025).

However, a limited number of empirical studies delved into students’ perceptions of multimodal writing in higher education, especially their critical insights into integrating AI into their academic achievements. To fill this gap, this study focuses on students’ experience of using ChatGPT 3.5 and Padlet AI image generation function in a Wikibook collaborative writing task, especially how different genders critically perceive the benefits of these tools and the ease of using them. By comparing gender perspectives, this study can contribute nuanced insights into equality in AI-enhanced environments and the critical literacy required to navigate and interact with these tools.

2.3. Students’ Emotions and Self-Efficacy in Human-AI Collaborative Writing

Emotions play a critical and fundamental role in teaching and learning in digital environments as they can influence students’ academic performance, motivation, information retention, and student well-being, especially crucial for adapting to a new learning environment (Vistorte et al., 2024; Zong & Yang, 2025). The anonymous nature of AI-based platforms endowed students with the power and opportunity to control their learning pace by alleviating the fear of judgment or embarrassment that students might encounter in face-to-face interactions (Lim & Lee, 2024). This can also foster students’ independence and problem-solving skills due to the lack of external support from human educators, leading to increased resilience and learning autonomy (L. Yang & Zhao, 2024). Recent research on students’ emotions in human-AI collaborative writing highlighted a mix of positive and negative affective responses, influenced by factors such as AI literacy and tool design (Albayati, 2024; Hoang, 2025; Kim et al., 2025; C. Yang et al., 2025), as AI literacy reflects individuals’ proficiency and expertise in AI-related knowledge and skills, thereby influencing university students’ comprehension and acceptance of AI (Zhai et al., 2024). Such emotions were revealed to predict learners’ self-efficacy and academic success with the long-term intention in technology-enhanced learning (Song & Song, 2023). The existing empirical study has revealed satisfaction, enjoyment, and motivation when students engaged in human-AI collaboration in writing (Kim et al., 2025). Such positive emotions toward AI tools can foster trust, reliance, and satisfaction, enhancing students’ willingness to continue using these tools over time (Yuan & Liu, 2025). For example, enjoyment stimulates positive emotional states that encourage students to explore and use ChatGPT for academic tasks voluntarily rather than out of obligation (Qu & Wu, 2024; Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2023).

On the other hand, frustration and dissatisfaction also existed when AI tools failed to meet users’ expectations (Rad & Rad, 2023), especially for female students (Csizer & Albert, 2024). Alongside students’ emotions, a distinct gender difference in self-efficacy was also found, with girls being more likely to show lower levels of self-efficacy than boys when they perceived pressure and risks in using digital systems (Kolar et al., 2024). Some studies, in contrast, have indicated a decreasing trend in gender differences among young learners (Chen et al., 2024; Yu & Deng, 2022) as the recent generation is equally exposed to technological education and training in the digital age. Thus, there is no consistent conclusion comparing emotional and self-efficacy differences in a digital learning environment from gender perspectives.

Research also highlighted that self-perception and confidence significantly influence how students engage with digital tools. Male students tend to report higher technology-related confidence, potentially stemming from social and cultural biases shaping gendered attitudes toward technology (Sobieraj & Krämer, 2020; Kolar et al., 2024). Conversely, female students tend to evaluate their performance more conservatively (Cai et al., 2017). These factors play a vital role in shaping emotional responses and performance evaluations in learning tasks but are seldom integrated into the adoption models used in educational technology research.

Meanwhile, previous studies regarding gender differences focused more on their general perception of their utilization of AI, in which students are not particularly guided in using these tools in a required manner. Few studies investigated students’ emotions and self-efficacy in using multimodal tools in a specific academic task, requiring students to select and reorganize AI-generated information under specific goal-oriented collaborative tasks. Moreover, there is minimal focus on gender disparities in this direction, neglecting the niche that may cause unequal support and impact on different genders. This study, therefore, compared gender perspectives regarding their experienced emotions and self-efficacy in using multimodal AI tools, providing empirical evidence on soundly integrating technology-powered learning pedagogy.

2.4. The Present Study

The existing literature has delved into the benefits and challenges students perceive when engaging with multimodal AI tools, highlighting the importance of fostering students’ independence and emotional well-being during collaborative writing. Though a plethora of studies revealed students’ recognition regarding AI tools’ support for their writing (Mahapatra, 2024; Shi et al., 2025; Teng, 2024), it was still underexplored whether different genders perceived such support in the same way, and whether such support is equal for both genders. To fill this gap, the present study, grounded on TAM theory, investigates the differences between genders regarding their perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, emotions, and self-efficacy after completing a multimodal writing task with Gen AI tools. This study might contribute to a nuanced insight into emotional and efficacy disparities across different genders, thus providing pedagogical implications for integrating educational technologies into teaching in a more engaged and equal manner by answering the following questions:

- What are students’ perceptions of the usefulness and ease of adopting multimodal generative AI tools in Wikibook? Are there significant gender variations?

- What are students’ emotions using ChatGPT and Padlet AI image generation function? Are there significant gender variations?

- What are students’ self-efficacy using ChatGPT and Padlet AI image generation function after the Wikibook collaborative writing task? Are there significant gender variations?

To answer the research questions above, this study utilized a five-point Likert scale questionnaire, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), to collect participants’ self-reported perceptions and an independent sample t-test to compare gender perspectives.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

The current research involved 140 undergraduates in Hong Kong who enrolled in the course Introduction to Linguistics over 13 weeks. During this course, students were divided into groups of 4–5 members to complete a collaborative Wikibook chapter writing task under linguistic topics, with each member contributing approximately 900 words to a chapter. They were also required to include multimedia elements, such as images and videos, in their chapters. The pedagogical guidance on this course and writing assessment followed 6P framework: plan, prompt, preview, produce, peer-review, and portfolio-tracking (Kong et al., 2024). Group members are required to peer edit each other’s section in the corresponding chapter of the book so as to help ensure that each section includes sufficient detail, that the writing is polished, and that the whole chapter is coherent (L. Wang, 2021). This has transformed traditional way of essay writing: writing is no longer a private activity; instead, the chapters are openly available online for viewing and peer-editing and students can learn from each other through constant online interactions. The collaborative experience of developing the Wikibook project was turned into a social process of knowledge construction (L. Wang, 2023). With the support of Wiki technology’s history function, students could iteratively revise their writing during group collaboration and discussion. During students’ writing, they are encouraged but not mandated to utilize a wide range of generative AI tools as they prefer, including ChatGPT 3.5 and Padlet AI image generation function. Among the 98 responses gained from 140 enrolled students, 95% male students reported using ChatGPT 3.5, and 61% of them used the Padlet AI image generation function. In comparison, 92% female students reported using ChatGPT, and 63% of them reported using Padlet AI image generation function (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of male and female students using Generative AI tools.

Based on the questionnaire responses, this study investigates students’ perceptions, grounded in the TAM, their emotional experiences when interacting with these tools, and their self-efficacy in using them as effective learning partners.

3.2. Instrument and Data Analysis

This study adopted a five-point Likert scale questionnaire to capture students’ perceptions and experiences after the multimodal writing task with AI tools. The questionnaire was based on TAM, with modifications to include aspects of satisfaction and emotional responses, as these constructs are critical in understanding multimodal AI-assisted learning (Kim et al., 2025). Specifically, items addressing perceived emotions were added to reflect emotions in collaborative writing tasks. These additions were informed by prior studies exploring emotional dimensions in technology adoption (Hanham et al., 2021). The questionnaire comprises four sections, starting with three items investigating participants’ perceived ease of use of AI tools, followed by 21 items exploring their perceived benefits of using these tools in writing. The third section comprises seven items regarding students’ emotions when using AI tools. The final section includes 11 items focusing on students’ self-reported competency in learning with AI tools in the future.

Then the researcher employed SPSS 30 independent samples t-test to statistically compare the responses of male and female participants based on the questionnaire data, providing a nuanced picture of how multimodal generative AI supports students’ writing and differences in gender perceptions.

The study also conducted individual interviews with 10 students (10% of the 98 questionnaire respondents, 5 male and 5 female), selected through random sampling, to collect qualitative data that would further clarify the questionnaire responses.

3.3. Reliability and Validation

A reliability analysis was conducted to evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire, which consisted of 42 items. The analysis produced a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.957, indicating an excellent level of reliability.

4. Results

The research results are analyzed under three categories: perception of the difficulty of the AI-assisted Wikibook project and ease of use of AI tools, students’ perceived benefits of the AI-assisted Wikibook writing task, and students’ emotions and self-efficacy during the learning process.

4.1. Perception of the Difficulty of the AI-Assisted Wikibook Project and Ease of Use of AI Tools

Table 2 below presents female and male students’ perceptions of the difficulty of the AI-assisted Wikibook project, and ease of use of the AI tools.

Table 2.

Students’ perceived ease of use.

As shown in Table 2, both female and male students reported gaining the highest score in invested time in the AI-assisted Wikibook writing task (Female: Mean = 4.12, SD = 0.76; Male: Mean = 3.97, SD = 0.85), followed by female students’ invested effort (Mean = 4.08, SD = 0.77) and male students’ invested effort (Mean = 3.79, SD = 0.93). This reflects students’ overall perception of the project as demanding, with students dedicating their time and energy to complete the task. It is also noticeable that though students reported this writing task as time-consuming and demanding, they all admitted that the AI Tools are easy to use (Female: Mean = 3.87, SD = 0.75; Male: Mean = 3.83, SD = 0.88). This reflects a shared perception of the technology integration as user-friendly, which likely facilitated students’ ability to focus on the content of their work rather than technical obstacles.

In summary, while females consistently reported slightly higher scores across all variables, the results reveal a consistent pattern of intensive engagement across genders. The high levels of effort and time investment, combined with manageable pressure and favorable usability ratings, suggest that the Wikibook collaborative writing with AI tools was an effective learner-centered learning approach, fostering active participation from users, highlighting the approach to provide a meaningful and equitable educational experience.

4.2. Students’ Perceived Benefits of the AI-Assisted Wikibook Writing Task

Table 3 below provides the results of a comparative analysis of students’ perceived usefulness of ChatGPT and Padlet AI image generation function across each writing step in the Wikibook collaborative writing task.

Table 3.

Students’ perceived benefits of the AI-assisted Wikibook writing task.

As shown in Table 3, it is worth noting that both female and male students reported this task as valuable to their learning (Female: Mean = 3.78, SD = 0.85; Male: Mean = 3.78, SD = 0.85), particularly in acquiring AI skills and knowledge (Female: Mean = 3.80, SD = 0.78; Male: Mean = 3.70, SD = 0.91). Regarding students’ perceived benefits of using ChatGPT and Padlet AI image generation function, this study found a significant difference between female and male students in ChatGPT’s function of “To format and finalize the chapter” (t = 2.043, p = 0.044). Despite this slight disparity, the overall trends suggest that ChatGPT assisted students’ writing in brainstorming, language polishing, and essay reorganizing, and the Padlet image generation function was considered valuable in generating creative and appealing pictures in a timely manner.

In conclusion, the perceived benefits were consistent across genders. These findings demonstrate the potential of a pedagogical design of collaborative writing with AI, which creates equitable and effective learning experiences.

4.3. Students’ Emotions and Self-Efficacy

Table 4 below demonstrates students’ emotions during the completion of the AI-assisted Wikibook writing task.

Table 4.

Students’ emotions during the AI-assisted Wikibook writing task.

Table 4 shows that students have encountered a wide range of emotions in completing the task, including satisfaction, anxiety, pressure, hardship, enjoyment, and tension. Among them, female students reported the highest score in the item of “I worked very hard during the AI-assisted Wikibook chapter writing process” (Mean = 4.12, SD = 0.69), followed by the item of “I felt pressured while working on the AI-assisted Wikibook project” (Mean = 3.88, SD = 0.78) and the item of “I experienced tension while writing the Wikibook chapter” (Mean = 3.87, SD = 0.81). Compared with the female counterparts, the male students gained lower scores in the three items mentioned above. They gained the highest score in the item of “I am satisfied with my performance in writing the Wikibook chapter” (Mean = 3.92, SD = 0.75), followed by the item of “I felt pressured while working on the AI-assisted Wikibook project” (Mean = 3.84, SD = 0.88) and the item of “I felt nervous while working on the Wikibook chapter” (Mean = 3.82, SD = 0.95). Furthermore, both genders reported similar levels of enjoyment and interest in the AI-assisted Wikibook project, such as “I enjoyed writing the Wikibook chapter” (Female: Mean = 3.28, SD = 1.03; Male: Mean = 3.47, SD = 0.92) and “I found the AI-assisted Wikibook project interesting” (Female: Mean = 3.6, SD = 0.85; Male: Mean = 3.68, SD = 0.99), which received medium ratings, with no significant differences found between male and female students.

Table 4 also shows the emotional equity students experienced in the Wikibook writing task. These results suggest that despite the presented challenges, the emotional demands were manageable for all students, as both genders reported interest and dedication simultaneously as pressure and anxiety. Such a balance between challenge and resilience is critical for fostering students’ AI skills and reasonable and responsible use of AI in future academic tasks. Table 5 displays male and female students’ self-efficacy regarding using different AI tools during the AI-assisted Wikibook writing task.

Table 5.

Students’ self-efficacy during the AI-assisted Wikibook writing task.

As shown in Table 5, both genders reported competence in AI tools, with females scoring slightly higher (Female: Mean = 3.77, Male: Mean = 3.53). Similarly, both groups demonstrated similar level of understanding of AI systems (Female: Mean = 3.80, Male: Mean = 3.67), reflecting the pedagogical success in fostering students’ foundational AI literacy.

One noticeable finding is that the highest two items are “I am aware of potential abuses of AI technology (e.g., plagiarism)” (Female: Mean = 4.03, SD = 0.78; Male: Mean = 3.87, SD = 1.02) and “I can evaluate the capabilities and limitations of an AI tool after using it for a period” (Female: Mean = 3.92, SD = 0.65; Male: Mean = 3.79, SD = 0.84) for both female and male students. This highlights students’ strong awareness of critical usage of AI tools rather than just relying on copying AI-generated information while losing their authentic voice. No significant differences were found between gender perspectives regarding self-efficacy. However, male and female students rated their proficiency in ChatGPT and Padlet AI functions lower than in other items. This suggests that although students can recognize AI tools’ functions and utilize them in improving writing, they still need training to master these tools comprehensively and skillfully.

To control the Type I error rate inflated by multiple comparisons, we applied the Holm–Bonferroni correction (Holm, 1979) within each of the four measurement constructs of the questionnaire: 3 items for students’ perceived ease of use, 21 items for perceived benefits, 7 items for emotional responses, and 11 items for self-efficacy. Independent-sample t-tests were first conducted at the item level. We then calculated the adjusted significance threshold (αadj) for each construct using the Holm–Bonferroni procedure. Notably, none of the observed differences reached statistical significance when evaluated against the construct-specific (αadj).

4.4. Interview Analysis Results

To complement the quantitative analysis presented earlier, this study also conducted interviews with students to gain deeper insight into their perceptions of the Wikibook project. Overall, both female and male undergraduates described the AI-assisted Wikibook project as a learning experience that combined strong interest with significant challenge. They reported that the project simultaneously developed their AI-related abilities (e.g., prompting, evaluating outputs, revising with AI support) and their linguistic and academic writing skills. Several students also linked perceived usefulness to concrete behaviors such as revising drafts multiple times, refining structure and wording, and contributing more substantively to group work. Examples of anonymized interview excerpts are presented below:

Male student 1: The AI-assisted Wikibook project is my favorite part of the course. The course has given us an overview of linguistic studies, while the in-depth research on a specific topic was achieved through our own efforts. I used AI to generate initial ideas, but I had to revise and reorganize the content myself again and again to make sure that my writing was of good academic standards and matched well with the rest of the Wikibook chapter.

Male student 2: The Wikibook project helped me to develop many skills related to ChatGPT, writing, and academic literacy. For example, I compared different AI-generated versions of a paragraph and then chose and edited the one that best fit our group’s argument. This made me more aware of structure and coherence in my writing.

Female student 1: The most useful aspect of this course was the AI-assisted Wikibook project, in which we were encouraged to conduct our own study in one area of linguistics and share it with others. After this project, I am more confident about expressing my opinions and more willing to study independently. I spent a lot of time revising the chapter—checking references, improving transitions, and making sure our group’s section matched the style of the whole book.

Female student 2: The AI-assisted Wikibook project was challenging, but through a lot of hard work I improved my AI skills, writing skills, presentation skills, and group collaboration skills. It was sometimes frustrating because I was not familiar with the AI tools and could not immediately achieve the results I wanted. I had to repeatedly adjust my prompts and re-edit the text or image, which took extra time, but it was worth it, as our group managed to produce a satisfactory multimedia Wikibook chapter in the end.

The interview data suggest that both male and female students perceived clear benefits from the Wikibook writing project, while also encountering emotional and technical difficulties. Female interviewees, in particular, emphasized the amount of effort and repeated revision required to reach satisfactory outcomes, which may help explain why they reported working harder despite achieving results similar to their male peers. At the same time, students’ descriptions of revising AI outputs, improving the clarity and organization of their chapters, and contributing more substantively to group work provide qualitative evidence that their perceived usefulness of AI support was linked to observable aspects of writing quality, revision patterns, and collaborative contribution, even though the present study did not include separate objective performance metrics.

5. Discussion

This study investigated gender equity in perceptions, emotions, and self-efficacy related to using generative AI tools, namely ChatGPT and Padlet’s AI image generation function, in a collaborative Wikibook writing task. Under the theoretical framework of TAM, the results of this study answered the three research questions, providing detailed insights into how multimodal generative AI tools support students’ academic writing outcomes, and how the learning process enhanced their AI literacy, which is essential for their future learning in the digital age.

First, the results revealed an equally perceived ease of use of AI tools and perceived benefits of engaging with the multimodal generative AI-assisted Wikibook writing task from both male and female perspectives. This aligns with prior research conclusions suggesting that students generally view generative AI tools as effective for improving productivity and enhancing collaborative learning (Gasaymeh et al., 2024). With minimal differences found in this study between gender perspectives, the results of this study support a non-gender-biased environment provided by AI tools (Shaw & Gant, 2002).

Second, this study contributes to the growing literature by providing a detailed landscape of students’ emotional well-being when engaging with multimodal generative AI tools. The results of this study are consistent with prior studies in revealing students’ enjoyment, anxiety, pressure, and dedication in multimodal AI-assisted learning environments (Kim et al., 2025; Rad & Rad, 2023). However, unlike prior research pointing out students’ frustration, loneliness and anxiety caused by the lack of external support and the inadequate regular training to use technologies (Xin & Derakhshan, 2025), this study found that the negative emotions reported by participants in this study were not originated from the inexperience of using technical applications, but a result of the challenging nature of the writing task and demanding navigation with AI-generated information as they perceived the AI tools as user-friendly. These results suggest that with students’ increasing knowledge in AI tools, they faced more challenges in critically evaluating AI information rather than adapting to new digital systems. Another significant contribution of this study is comparing gender emotional disparities in multimodal generative AI-assisted learning environments. The result showed that no emotional differences were found between the two genders, providing empirical evidence to show that AI can support learners equally. The male students’ higher scores in satisfaction may stem from gender-sensitive self-evaluation, with male students often exhibiting greater confidence in technology-related performances (Virtanen et al., 2015). Such variation is consistent with previous findings on gender differences in perception of their technological capabilities rather than goal achievements (Sobieraj & Krämer, 2020). These findings underscore the importance of emotional support to strengthen students’ confidence when designing technology-integrated learning activities to ensure that all students feel equally supported and capable. Educators are encouraged to design collaborative tasks where students of diverse genders work together. This promotes peer learning and reduces emotional burden.

Thirdly, different from previous studies’ findings on male students’ higher level of self-efficacy in technology-related tasks (Kolar et al., 2024), this study found no significant differences in male and female self-efficacy when using multimodal generative AI tools despite these emotional differences. Besides students’ recognition of perceived value and significance that AI provides for learning, both genders showed strong confidence in selecting proper tools and identifying AI-generated information, which falls in line with the definition of AI literacy (Kong et al., 2021; Long & Magerko, 2020). This study contributes to the literature by providing an exemplary pedagogy of training the young generation as responsible citizens with critical thinking and creativity through a hands-on experience integrating AI into authentic learning assessments. Since students demonstrated strong awareness of AI misuse, teachers are suggested to integrate explicit discussions on ethical AI use into the curriculum, which can further enhance their critical thinking and responsible use of tools. Another worthwhile contribution is a manageable balance of challenge and resilience students demonstrated during the collaborative task assisted by multimodal generative AI tools, as higher education is now rapidly reshaped by updated AI applications, with an urgent need to foster students and educators an accurate understanding of AI and its implications in modern teaching contexts (Luckin et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2024). The lack of significant gender differences in self-efficacy and emotional responses to AI tools underscores the potential for equitable adoption of AI-assisted pedagogy. However, prior studies have noted that familiarity with AI tools plays a critical role in how students experience and evaluate such technologies (Chen et al., 2024). Future research should explore how prior exposure to generative AI shapes students’ perceptions and outcomes.

The findings of this study are situated within the cultural and educational context of Hong Kong, where the policy and culture may vary from other nations and regions. Thus, the results may not fully generalize to other cultural contexts, particularly those with different pedagogical norms or attitudes toward technology.

6. Conclusions

Overall, this study answered the three RQs and suggested the following: (1) both male and female students perceived multimodal generative AI tools as user-friendly in the Wikibook chapter writing task and these tools can provide real-time suggestions for writing improvements while female students reported to show significant higher recognition of ChatGPT’s function in formatting their writing; (2) both male and female students experienced enjoyment, satisfaction, pressure, anxiety during engagement with AI tools; (3) there are no significant differences in male and female students’ self-efficacy in using multimodal generative AI tools, suggesting the AI-assisted Wikibook collaborative writing as a sound pedagogical approach to promote students’ writing skills without gender bias; and (4) both male and female students demonstrated capable AI literacy in critically evaluating and selecting AI-generated information, especially in identifying the misinformation and ethical issues related to AI. By revealing a comparative perspective of gender equity on experience and perception in multimodal generative AI-assisted learning environments, this study may provide implications for educational policymakers, educators, and technology designers for inclusive, equitable, and engaging learning environments that support all students in leveraging the potential of generative AI. By focusing on gender equity in effort, satisfaction, and emotional responses, stakeholders can create more balanced and supportive experiences that foster academic and personal well-being.

There are several limitations of this study. First, the research was conducted with undergraduates from a single higher education institution in Hong Kong, all enrolled in a linguistics course; this homogeneity limits the transferability of results to other educational contexts, disciplines, and cultural settings. Future research should explore gender differences in AI-assisted learning across diverse educational contexts and age groups with secondary instruments. Second, the study relied on self-reported data, and future research is suggested to employ observational methods or objective assessment of students’ performances. Third, this study lacks systematic attrition analysis and non-respondent characteristics report. Future studies are suggested to add these aspects for a more comprehensive analysis without bias concerns. Another limitation is the omission of participants’ prior experience with AI tools, which may have influenced their perceptions and responses. Future studies should adopt a more intersectional approach to incorporate prior experience as a covariate to isolate its effect on the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.; methodology, L.W.; software, B.R.; validation, L.W. and B.R.; formal analysis, L.W. and B.R.; investigation, B.R.; resources, L.W.; data curation, L.W. and B.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R.; writing—review and editing, L.W.; visualization, B.R.; supervision, L.W.; project administration, L.W.; funding acquisition, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Inter-institutional Collaborative Activities Portion of the Teaching Development and Language Enhancement Grant, The Education University of Hong Kong, grant number T5004.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Education University of Hong Kong (Ref. no. 2022-2023-0264; 12 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abd-Alrazaq, A., AlSaad, R., Alhuwail, D., Ahmed, A., Healy, P. M., Latifi, S., Aziz, S., Damseh, R., Alrazak, S. A., & Sheikh, J. (2023). Large language models in medical education: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions. JMIR Medical Education, 9(1), e48291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayati, H. (2024). Investigating undergraduate students’ perceptions and awareness of using ChatGPT as a regular assistance tool: A user acceptance perspective study. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseven, T., & Bal, M. (2025). Critical literacy in artificial intelligence assisted writing instruction: A systematic review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 57, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z., Fan, X., & Du, J. (2017). Gender and attitudes toward technology use: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 105, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Liu, W., & Liu, X. (2024). What drives college students to use AI for L2 learning? Modeling the roles of self-efficacy, anxiety, and attitude based on an extended technology acceptance model. Acta Psychologica, 249, 104442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizer, K., & Albert, A. (2024). Gender-related differences in the effects of motivation, self-efficacy, and emotions on autonomous use of technology in second language learning. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(4), 819–828. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar]

- Duhaylungsod, A. V., & Chavez, J. V. (2023). Chatgpt and other ai users: Innovative and creative utilitarian value and mindset shift. Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 33, 4367–4378. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Gasaymeh, A. M. M., Beirat, M. A., & Abu Qbeita, A. A. A. (2024). University students’ insights of generative artificial intelligence (AI) writing tools. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanham, J., Lee, C. B., & Teo, T. (2021). The influence of technology acceptance, academic self-efficacy, and gender on academic achievement through online tutoring. Computers & Education, 172, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N. H. (2025). Investigating EFL students’ emotional responses in AI-assisted language learning: A Broaden-and-Build Theory approach. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J. (2024). When generative artificial intelligence meets multimodal composition: Rethinking the composition process through an AI-assisted design project. Computers and Composition, 74, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., & Lai, C. (2025). How did the generative artificial intelligence-assisted digital multimodal composing process facilitate the production of quality digital multimodal compositions: Toward a process-genre integrated model. TESOL Quarterly, 59, S52–S85. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J., & Yi, Y. (2023). Beyond ChatGPT: Multimodal generative AI for L2 writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 62, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Kim, J., Knotts, T. L., & Albers, N. D. (2025). AI for academic success: Investigating the role of usability, enjoyment, and responsiveness in ChatGPT adoption. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 14393–14414. [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, N., Milfelner, B., & Pisnik, A. (2024). Factors for customers’ AI use readiness in physical retail stores: The interplay of consumer attitudes and gender differences. Information, 15(6), 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S. C., Cheung, W. M. Y., & Zhang, G. (2021). Evaluation of an artificial intelligence literacy course for university students with diverse study backgrounds. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S. C., Lee, J. C. K., & Tsang, O. (2024). A pedagogical design for self-regulated learning in academic writing using text-based generative artificial intelligence tools: 6-P pedagogy of plan, prompt, preview, produce, peer-review, portfolio-tracking. Research & Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 19(030). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., & Lee, M. (2024). The buffering effects of using avatars in synchronous video conference-based online learning on students’ concerns about interaction and negative emotions. Education and Information Technologies, 29(12), 16073–16096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. H., Zhou, K., Li, L., & Sun, L. (2025). Integrating generative AI into digital multimodal composition: A study of multicultural second-language classrooms. Computers and Composition, 75, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Zhang, L. J., & Biebricher, C. (2024). Investigating students’ cognitive processes in generative AI-assisted digital multimodal composing and traditional writing. Computers & Education, 211, 104977. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D., & Magerko, B. (2020, April 25–30). What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–16), Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R., Cukurova, M., Kent, C., & Du Boulay, B. (2022). Empowering educators to be AI-ready. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, S. (2024). Impact of ChatGPT on ESL students’ academic writing skills: A mixed methods intervention study. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D. T. K., Xinyu, C., Leung, J. K. L., & Chu, S. K. W. (2024). Fostering students’ AI literacy development through educational games: AI knowledge, affective and cognitive engagement. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(5), 2049–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(4), 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K., & Wu, X. (2024). ChatGPT as a CALL tool in language education: A study of hedonic motivation adoption models in English learning environments. Education and Information Technologies, 29(15), 19471–19503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, D., & Rad, G. (2023). Exploring the psychological implications of chatGPT: A qualitative study. Journal Plus Education, 32(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Rodríguez, J. M., Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., Buenestado-Fernández, M., & Lara-Lara, F. (2023). Use of ChatGPT at university as a tool for complex thinking: Students’ perceived usefulness. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 12(2), 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L. H., & Gant, L. M. (2002). Users divided? Exploring the gender gap in Internet use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 5(6), 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H., Chai, C. S., Zhou, S., & Aubrey, S. (2025). Comparing the effects of ChatGPT and automated writing evaluation on students’ writing and ideal L2 writing self. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, S., & Krämer, N. C. (2020). Similarities and differences between genders in the usage of computer with different levels of technological complexity. Computers in Human Behavior, 104(5), 106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C., & Song, Y. (2023). Enhancing academic writing skills and motivation: Assessing the efficacy of ChatGPT in AI-assisted language learning for EFL students. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1260843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, B., Mao, H., & Yin, C. (2020). Male and female users’ differences in online technology community based on text mining. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenningsson, J., Höst, G., Hultén, M., & Hallström, J. (2022). Students’ attitudes toward technology: Exploring the relationship among affective, cognitive and behavioral components of the attitude construct. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 32(3), 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M. F. (2024). “ChatGPT is the companion, not enemies”: EFL learners’ perceptions and experiences in using ChatGPT for feedback in writing. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, S., Räikkönen, E., & Ikonen, P. (2015). Gender-based motivational differences in technology education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 25(2), 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistorte, A. O. R., Deroncele-Acosta, A., Ayala, J. L. M., Barrasa, A., López-Granero, C., & Martí-González, M. (2024). Integrating artificial intelligence to assess emotions in learning environments: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1387089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. (2021). Blending a linguistics course for enhanced student learning experiences in a Hong Kong higher education institution. In C. P. Lim, & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Blended learning for inclusive and quality higher education in Asia (pp. 103–124). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. (2023). Adoption of the PICRAT model to guide the integration of innovative technologies in the teaching of a linguistics course. Sustainability, 15(5), 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., & Ren, B. (2024). Enhancing academic writing in a linguistics course with Generative AI: An empirical study in a higher education institution in Hong Kong. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Wang, X., & Su, Y. S. (2024). Critical analysis of the technological affordances, challenges and future directions of Generative AI in education: A systematic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 44(1), 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X., Wang, L., Lee, L. K., & Liu, R. (2025). The effects of generative AI on collaborative problem-solving and team creativity performance in digital story creation: An experimental study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 22(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, B. E. (1997). Gender differences in computer-related attitudes and behavior: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 13(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z., & Derakhshan, A. (2025). From excitement to anxiety: Exploring English as a foreign language learners’ emotional experience in the artificial intelligence-powered classrooms. European Journal of Education, 60(1), e12845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Wei, M., & Liu, Q. (2025). Intersections between cognitive-emotion regulation, critical thinking and academic resilience with academic motivation and autonomy in EFL learners: Contributions of AI-mediated learning environments. British Educational Research Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., & Zhao, S. (2024). AI-induced emotions in L2 education: Exploring EFL students’ perceived emotions and regulation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 159, 108337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., & Deng, X. (2022). A meta-analysis of gender differences in e-learners’ self-efficacy, satisfaction, motivation, attitude, and performance across the world. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 897327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L., & Liu, X. (2025). The effect of artificial intelligence tools on EFL learners’ engagement, enjoyment, and motivation. Computers in Human Behavior, 162, 108474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C., Wibowo, S., & Li, L. D. (2024). The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: A systematic review. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., Niu, J., Zhong, L., & Gyasi, J. F. (2023). The effectiveness of artificial intelligence on learning achievement and learning perception: A meta-analysis. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(9), 5650–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y., & Yang, L. (2025). How AI-enhanced social–emotional learning framework transforms EFL students’ engagement and emotional well-being. European Journal of Education, 60(1), e12925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).