Abstract

Research indicates that attention impacts executive function skills, which playful activities can enhance. While free play is valued in early childhood education, realising it is difficult. Using mixed methods, we examine the benefits of free play for children’s attention and explore the means to realise it as true play. This study involved 16 children aged 21–34 months. Quantitative data were collected by measuring children’s attention levels during playful activities. Qualitative data were obtained through observations and reflections on their play. Data were analysed to examine children’s attention longitudinally and capture the environmental inputs of the teacher who facilitated the children’s free play environment. The results showed that children’s attention increased after free play, which had been tactfully manipulated by the teacher with professional pedagogical skills. Based on the results, we formulated a Playfulness Realisation Framework that illustrates the dialectical interaction between environmental inputs in the play context and children’s playfulness, which ultimately enhanced their attention. We highlight in the framework the importance of the continuous interplay between children’s interests and teachers’ pedagogical inputs, which is presented as a 5Cs model. This framework serves as a practical guideline for teachers to nurture children’s playfulness and improve their attention.

1. Introduction

Play is a key contributor to every aspect of children’s development, especially in early childhood (Bruner, 1972; Gibson et al., 2017; Ginsburg et al., 2007; Pellis & Pellis, 2007; Piaget, 1952, 1962; Vygotsky, 1966, 1978), and it is crucial for success in school (Piaget, 1952). It has long been a core approach in the education of preschool children because it satisfies children’s basic needs (Goldstein, 2012; UNICEF, 2018) and supports children’s development (Colliver et al., 2022; Dankiw et al., 2020; UNICEF, 2022; Vygotsky, 1966; Zosh et al., 2022). However, the context-dependent nature of play poses considerable challenges to frontline early childhood teachers when implementing “play-based learning” in the classroom (Rogers & Evans, 2008; Cheng, 2010, 2011; Samuelsson & Carlsson, 2008; Dockett, 2011; OECD, 2006; Pyle & Danniels, 2017). Because attention has an important role in children’s development and learning and impacts children’s executive function skills (Diamond, 2013), this paper first examines the potential benefits of play in enhancing children’s attention and, second, explores the factors that affect how these benefits are achieved via children’s playful activities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attention and Its Role in Children’s Development and Learning

As a cognitive process, attention is harder to define than it might initially seem. Paying attention requires the ability to focus on a person or object while ignoring other interesting things in the environment that are competing for awareness. The ability to pay attention develops over time, and it can be nurtured and enhanced by good caregivers. Paying attention involves several mental steps, including being alert and choosing what to pay attention to. This requires intentional steps that the individual has to master. The ability to pay attention differs from child to child, from the length of the attention span to the intensity of the attention. Moreover, this is connected to the ability to self-regulate, which refers to a child’s ability to actively behave in a way that allows them to achieve a goal (Butler et al., 2017).

Attention skills impact self-control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, which are known collectively as executive function (EF) skills (Diamond, 2013). Executive function skills are crucial building blocks in the early development of children’s cognitive and social capacities (Centre on the Developing Child, 2011). Attention skills are therefore closely connected to children’s cognitive and social development (Van Lier & Deater-Deckard, 2016). Children with strong attention are more likely to perform well in school because they can focus on relevant information while ignoring distractions, monitor their own progress, and resolve conflicting information to complete tasks. Extensive research has documented the significance of children’s early skills in charting later developmental trajectories (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Lillard & Else-Quest, 2006; as cited in Carlson et al., 2013). Murillo et al. (2020) further stated that the ability to maintain attention during play is crucial for later academic success, as it lays the groundwork for a more structured learning environment. It has also been found that children who enter formal schooling without the ability to pay attention, remember instructions, and demonstrate self-control experience more difficulties in elementary school and high school (McClelland et al., 2007; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2003; Pereira et al., 2021).

2.2. The Development of Attention and Executive Function Skills Through Play

Relatively little is known about the development of attention during the early years. Attention is automatic and exploratory during early infancy. In the early 1980s, research identified that there is an increase in attention span in 2- to 6-year-olds (Krakow & Kopp, 1987, 1982). Gray (2011) mentioned that the high rate of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) may be attributed to the decline of play, which might otherwise help facilitate the development of self-control and emotional regulation. Another study conducted by Holmes et al. (2006) observed a greater attention level in preschool children following sustained outdoor play periods. However, the nature of play matters. Ruff et al.’s (1998) study found that there is an increase in children’s attention in less structured situations of free play than in more structured ones. Whitebread and his colleagues (Whitebread et al., 2009) studied the link between playful activities and the development of children’s metacognitive and self-regulatory skills. They found that play, particularly pretence or symbolic play, is significant in its contribution to children’s development as metacognitively skilful, self-regulated learners. Berk and Meyers (2013) indicated that when children are engaged in play, the use of private speech can enhance the task performance and the development of EF abilities, including self-control and attention. Also, the greatest proportion of self-regulatory behaviours is found when playful activities are initiated by children in small groups without adult supervision. In this respect, research suggests that free play, particularly playful activities initiated by children, can enhance executive functioning by offering children opportunities for problem-solving and self-regulation (Zych et al., 2016; Rostan et al., 2014). They propose that play promotes interactions among peers and fosters social competence and emotional regulation, which are essential components in the development of executive functioning skills. Rostan et al. (2014) also stated that when children engage in different social encounters and negotiate rules within their play scenarios, they enhance their ability to manage impulses and develop self-control, which are the key elements of executive functioning skills. Whitebread and Jameson (2010) reported in their research that pretend play impacted deductive reasoning and social competence and that socio-dramatic play showed an improvement in ‘self-regulation’ among children who are highly impulsive. In some play scenarios, children may need to practise their self-regulation by inhibiting their immediate desires in favour of a delayed reward (Liu et al., 2023). In addition, the nature of free play encourages children’s cognitive flexibility, as they have to adapt to the changing patterns of play and collaborate with their peers, which further strengthen the development of executive functioning skills (Harris, 2016; Hassinger-Das et al., 2017). Free play provides a range of opportunities for children to make plans, observe their own actions, and refine their plans based on the responses of peers and the environment.

While there may not be scientific evidence establishing a causal relationship between play and executive functional skills, existing literature suggests that free play or child-led play can significantly benefit the development of children’s attention processes and executive functions, while other forms of play may not. To support our main claim regarding the benefits of play, we need to better understand the essence of free play/child-led play. Early childhood researchers and theorists find that play is difficult to define, as its form and nature change according to different educational theories (Cheng, 2010; Fleer, 2011; King, 1979; Rubin et al., 1983; Pyle & Danniels, 2017; Zosh et al., 2018). However, they agree on the key characteristics of playful experiences such as “playfulness” (Dewey cited in Parker-Rees, 1999; Masek & Stenros, 2021) and the players’ experience of “flow” (Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1993). Playfulness can be described as the attitude of a person when he or she is engaged mentally and physically in the state of play. The player is engaged, involved, and satisfied in the activity by their internal drive. Playfulness is crucial for fostering a positive emotional climate and thus enhances learning outcomes (Zych et al., 2016; Smith, 2003). Heimann and Roepstorff (2018) suggested that “… situations lacking autonomy will not be experienced as playful….”. According to a recent United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) document, play is described as “children’s agency and control over the experience” (UNICEF, 2018, p. 7). In short, though researchers categorize play into various forms, such as guided play, structured play, cooperative play, games, and free play (Masek & Stenros, 2021; Zosh et al., 2018), true play should involve some degree of agency, enabling children to be capable, autonomous, and agents of their playful learning journeys (UNICEF, 2018) to reach their own state of “playfulness”. A recent study by Mukherjee et al. (2023) suggested that whether an activity is considered as “true play” depends on children’s own perceived sense of agency, safety, and play as an end in itself. The results denoted that these core qualities combine to potentially trigger a joyful state of mind, and thus, the activity can elicit a kind of playfulness amongst children. Thus, free play must be viewed from children’s perspective and is difficult to be judged based on its form alone.

2.3. Adults’ Role During Play

If free play is so significant in promoting “playfulness”, does this mean that adults do not play any role in children’s free play? Studies show that adults’ participation in play enriches the play experience and promotes emotional, cognitive, and social development in children. An adult’s presence can help or impede children in managing intricate play scenarios and thus can enhance or diminish children’s engagement (Cheng, 2010). It is important for adults to “lead by following” (Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center, 2017), in which they should lead the play by carefully observing and following children’s play ideas and expanding them so that children can remain responsive and engaged. Yet, a review study on ECE teachers’ perspectives on play-based learning by Bubikova-Moan et al. (2019) revealed that ECE teachers across different countries struggle to position themselves in children’s play, with different views on balancing children’s learning and respecting children’s agency as autonomous players and learners. While children may benefit from teacher facilitation in more cognitively complex play, such as sociodramatic play, and higher levels of social play, i.e., cooperative play, the over-involvement of teachers during free play may pose more negative effects and cause interruption to children’s flow during play (Cheng, 2001; Tarman & Tarman, 2011). Teachers in Anji (a county in Zhejiang Province, China) uphold the view on the non-participatory role of teachers by stepping back with “hands down, mouths shut, ears and eyes open to hear and see the child”, which allows teachers to gain a better understanding of children in play (Coffino & Bailey, 2019). The contrasting views from both sides of the spectrum challenge adults’ role in children’s play: how can an adult’s presence facilitate children’s play without infringing upon their agency necessary for the promotion of “playfulness”?

To sum up, recent findings on the features of playfulness that give the child agency and ownership of their playful experiences align with the aforementioned literature reporting a correlation between free play and the development of attention. Nevertheless, to ensure playfulness and preserve children’s agency, teachers need to capture and sustain the features of being “engaged, involved and satisfied by a person’s internal drive” to support the development of children’s attention. Thus, we adopt the above features of playfulness as the working definition of play in this study and aim to explore the factors and roles of teachers to enhance children’s level of attention.

3. Research Questions

Given that true play itself and its optimised benefits are hard to realise and the role of teachers during play remains unclear, this paper examines how to realise true play to enhance attention and explores the factors, particularly the appropriate role of teachers, affecting this enhancement in the process. We aim to answer the following research question:

“What are the changes in the attention level of children during free play activities, and how could teachers realise true play and enhance attention?”

3.1. Methods

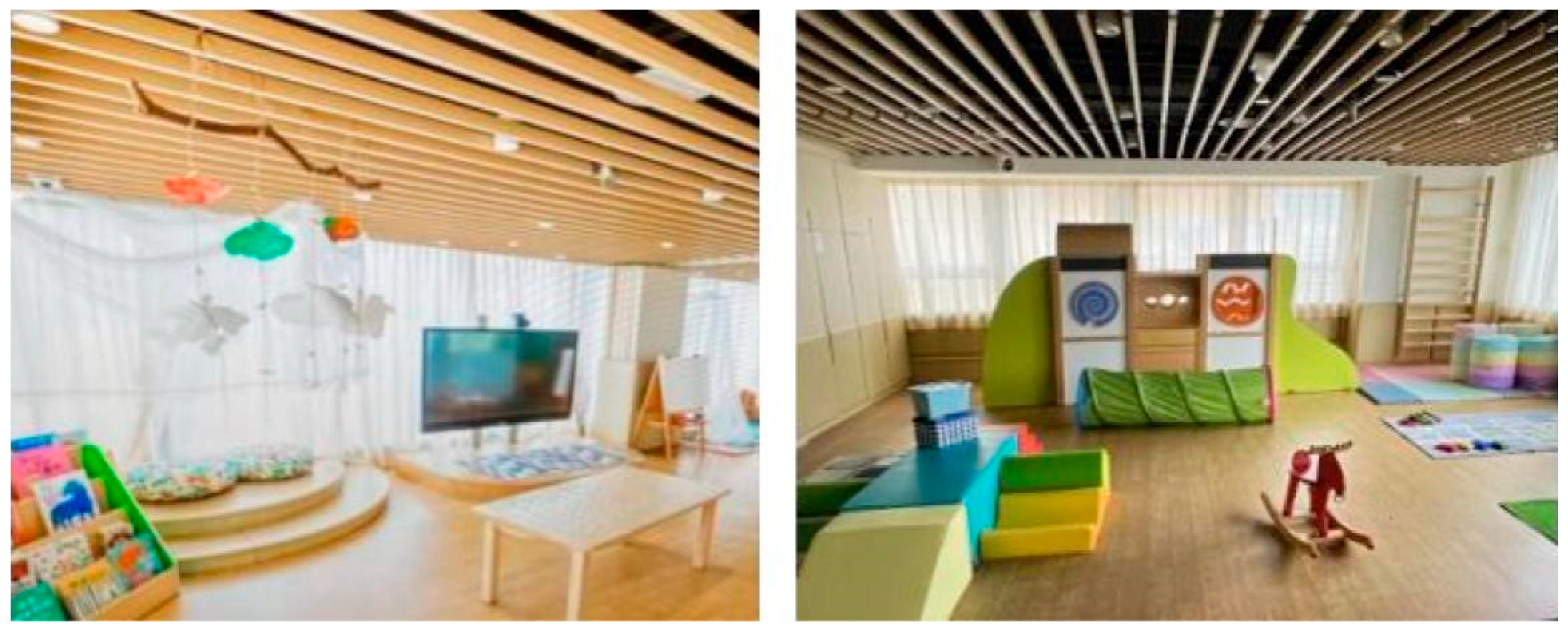

According to the literature, free play can enhance children’s attention. Our study was conducted in an indoor Play Laboratory (Playlab), established in 2019 at a tertiary institute in Hong Kong as part of a new early childhood teacher education programme. The Playlab aims to help early childhood pre-service teachers gain the conceptual understanding and practical skills needed to facilitate free play (Cheng et al., 2022). The environment of the Playlab is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The Playlab environment.

To obtain reliable data to answer the research question, this study captures not only the attentional behaviour of children when engaged in free play but also the pedagogical and environmental inputs that facilitate children to achieve playfulness during free play. A mixed-method approach, using quantitative and qualitative methods, was adopted to collect progressive data. The quantitative data was mainly collected using an observation sheet (Appendix A) previously adopted (Cheng et al., 2015) for observing children’s levels of attention. The qualitative data aimed to capture the inputs adopted by the teacher who designed and facilitated free play in the Playlab (Cheng, 2010). As Van Manen (1991) notes, it is not easy to tap into a teacher’s pedagogy because it is often tacit, and some teachers find it hard to conceptualise their assumptions and articulate them; therefore, the team adopted an action research method to collect continuous inputs during the free play process. Video vignettes capturing the free play activities of the children were used, a naturalistic observation in the form of reflective journal and field notes to record the play behaviour of the children and the discussions between the teacher and the research team after each play session were documented. The discussion protocols, with the support of the teacher’s reflective journal, focused on the following: (a) the interests and attentional behaviours of the children in that session, (b) the most favoured play areas or toys found in that session, and (c) the environmental inputs that the teacher adopted to facilitate, sustain, and extend the “playfulness” of the children (Cheng, 2010). Moreover, the recorded reflective discussions were used as guides for the continuous design of the play environments and pedagogies used by the teacher to sustain children’s “playfulness”. In short, data was mainly collected via (a) observation of children’s attention processes, (b) observation of the interactive behaviour between the teacher and children during play sessions, (c) the teacher’s reflective journal, and (d) continuous discussion between the teacher and the research team.

3.1.1. The Design of the Playlab

Inspired by the environmental inputs for outdoor play areas in Canada (Herrington & Lesmeister, 2006), the research team, assisted by the teacher, focused on the basic setting of the Playlab, which is central to children’s playfulness or flow. It consists of two rooms located on different floors, each around 600 square feet. One of the rooms caters to physical activities, including, for example, climbing frames and slides, while the other one caters to quieter playful activities. There is a small one-way observation room on each floor and four video recorders attached to the ceiling of each room, aiming to capture the interactive behaviour between the children and the teacher during the free play activities.

The environmental design, according to the needs of the particular age group, was taken care of by the teacher, who was supported by the research team during the two cohorts of free play sessions. Based on government documents from the Education Bureau (2020) on young toddlers’ developmental abilities, daily experiences, and general interests, the teacher was responsible for arranging and changing the materials of the Playlab accordingly. The initial setting was based on the prior life experiences of the young children, such as areas for playing at home, playing in the park, and going to the supermarket. Thus, a home corner, part of a park, and a supermarket were set up as the initial context for the children to develop playful activities. (Due to their ages, the child could be accompanied by their primary caregivers during play.) A variety of natural materials, such as flowers, petals, leaves, wooden sticks, plastic bottles, and paper boxes, were provided to develop playful contexts according to children’s interests, needs, and abilities. Supported by student assistants, the teacher facilitated the free play sessions with a 5 min introduction of the set-ups to the children and the caregivers, who were randomly selected to one of the floors and then asked to swap halfway through the session. Children were free to explore and play for 2 h in the Playlab, while their caregivers, who had taken a two-hour workshop conducted by the researcher, were advised not to intervene in the children’s play activities unless they were in danger.

3.1.2. The Subjects

Sixteen Hong Kong children, aged 21 to 34 months, who had no formal playgroup experience prior to joining the play activities, were recruited via purposive sampling to engage in 20 sessions of free play activities in the Playlab, and each session lasted around two hours. The 16 children, comprising 11 boys and 5 girls, were separated into two cohorts. Cohort 1 (with 9 children, 8 boys and one girl, aged 21 to 32 months) attended their free play sessions between 15 October 2020 and 22 April 2021, while Cohort 2 (with 7 children, 3 boys and 4 girls, aged 25 to 34 months) attended theirs between 4 May 2021 and 13 July 2021.

3.1.3. Data Collection Process

Two cohorts of children were employed to compare the attention level between Cohort 1 children at the end of their free play sessions and Cohort 2 children at the beginning of their free play sessions. Both cohorts of children were also combined to longitudinally examine the progressive change in attention levels when they participated in more sessions of free play. Details of the data collection process are shown below.

- (1)

- Data collection began in October 2020 when the first free play session started and finished in July 2021 when the last free play session ended.

- (2)

- Child observation was conducted by two trained research assistants using purposely designed observation sheets across the 20 free play sessions, which in total lasted 40 h. In each of the 2 h sessions, three children were systematically observed. Each child was observed five times per session, and each observation lasted for 5 min. The trained observer would observe the target child for one minute and code the behaviours for another four minutes.

- (3)

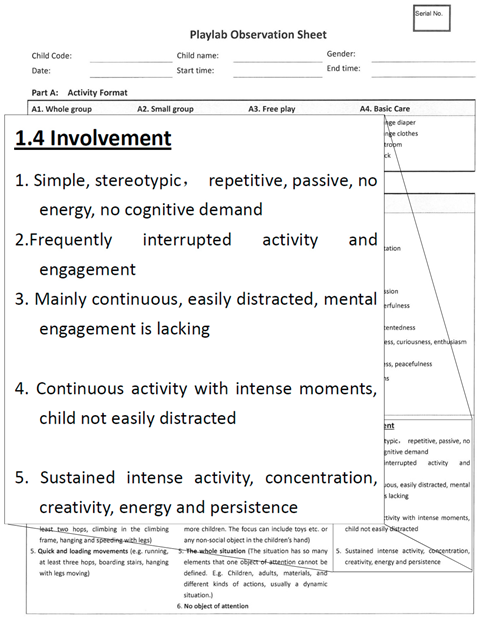

- Observation was conducted according to the Involvement observational scale, which quantifies the attention levels of children. This assessment framework was adopted in a previous study on children’s agentive orientations (Cheng et al., 2015). The Involvement scores range from 1 to 5, with a higher score indicating a higher level of concentration. Specifically, the observed child would be given a lower score when the child interrupted activities, was easily distracted by their surroundings, or lacked mental engagement. On the other hand, when the observed child demonstrated good attention, for example, performing continuous or sustained activity; showing high concentration, creativity, and persistence; and not being easily distracted by their surroundings, the Involvement score would be higher. The interpretations of the five ratings on the Involvement scores are presented in Table 1.

- (4)

- The research assistants attended training sessions given by the researcher to ensure the validity and reliability of the Involvement scale.

- (5)

- Apart from quantitative data, a tape recorder was attached to the child to capture their utterances during the activities. Video vignettes of children’s free play activities were recorded by video-recorders on the ceiling of the Playlab to enrich and verify the data collected. The research assistants were asked to swap their targeted children’s observation sheets. When there was discrepancy, both research assistants reviewed the recorded videos together, and the records were clarified based on their mutually agreed interpretation.

- (6)

- The teacher, who took care of the environmental inputs of the Playlab, was asked to document the designs of the 20 Playlab sessions and to write a reflective journal on her observations after each session. Additionally, the research team met with the teacher after each session to hold reflective discussions. Reflective reports were made after each discussion.

Table 1.

Involvement scale.

Table 1.

Involvement scale.

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Simple, stereotypic, repetitive, passive, no energy, no cognitive demand |

| 2 | Frequently interrupted activity and engagement |

| 3 | Mainly continuous, easily distracted, mental engagement is lacking |

| 4 | Continuous activity with intense moments, child is not easily distracted |

| 5 | Sustained intense activity, concentration, creativity, and persistence |

3.1.4. Quantitative Data Analysis

To examine the changes in the level of involvement of the children throughout the 20 free play sessions, we classified the sessions into four time points, with five sessions at each time point. The first time point included the first five free play sessions, interpreted as the time at which the children had attended less than 10 h (or less than 25%) of free play sessions. Similarly, the second time point included Session 6 to Session 10, by which time the children had attended a further 10 h (or the next 25%) of free play sessions, and so on. Choosing four time points could provide insights into the progressive change in the attention behaviour of children during free play. Also, four time points (but not larger) entailed enough (or five) sessions at each time point so that each child could be observed in at least one session per time point when one to three children were systematically observed in each session. All Involvement scores, collected from a child in different sessions within one particular time point, were averaged to obtain a single mean value for that time point; the attention behaviour of each child at each of the four time points was then recorded. In total, we obtained Involvement scores at four time points for nine children from the first cohort and seven children from the second cohort.

Two statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 to examine the level of involvement of children in free play. First, we used an independent sample t-test to compare the difference in the mean Involvement scores of the two cohorts of children, in which the first group participated in less than 10 h of free play sessions at time point 1 and the other participated in more than 30 h of free play sessions at time point 4. Second, we used repeated-measures ANOVA to longitudinally examine the progressive change in the Involvement scores of children in both groups throughout the 40 h of free play sessions. The normality of Involvement scores was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk Test, and the assumption of sphericity was checked with Mauchly’s Test.

3.1.5. Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data were employed to uncover the factors, particularly the teacher’s use of appropriate tact, which affects the enhancement of children’s attention during free play. As Van Manen (1991) explained, tact manifests itself in everyday life and is highly sensitive to context, making it best examined through direct engagement between teachers and children. Thus, the project team designed multiple means to capture the trustworthy contextual data that happened during teacher-children’s interactions. They include (i) rating scales based on naturalistic observation, (ii) video vignettes and audio recordings from free-play sessions, (iii) teacher’s continuous reflective journals, (iv) post-session discussions between project staff and teacher, and (v) field notes taken by a project team member, who was responsible for qualitative data analysis, during the non-interventive observations in free-play sessions. All forms of data were swiftly transcribed by a research assistant afterwards.

Following the suggestion of Merriam (1998), coding focused on the interplay between highly engaged playful behaviour and the tact of the teacher to identify emergent patterns, which were then classified into categories. By drawing diagrams and mind-maps based on these categorized data and mapping it with field notes and the rating scales of relevant children, significant themes on how the environmental inputs affected children’s playfulness and hence attention emerged. To consolidate the data obtained, episodes of playful scenarios with highly engaged children were written. Through repeated reading and discussion of these episodes, the research team was able to identify factors contributing to the enhancement of attention. This procedure of analysis was applied to data in both the first and the second cohort. By doing so, the data from the two cohorts could be triangulated. By comparing the written episodes from both cohorts, similar themes and patterns were identified. The credibility of the design was ensured, and the team are confident in the generated findings.

4. Results

4.1. Higher Attention for Children Immersed in Playfulness

Both the quantitative and qualitative data showed that children’s attention span and its intensity were higher when children immersed in playfulness.

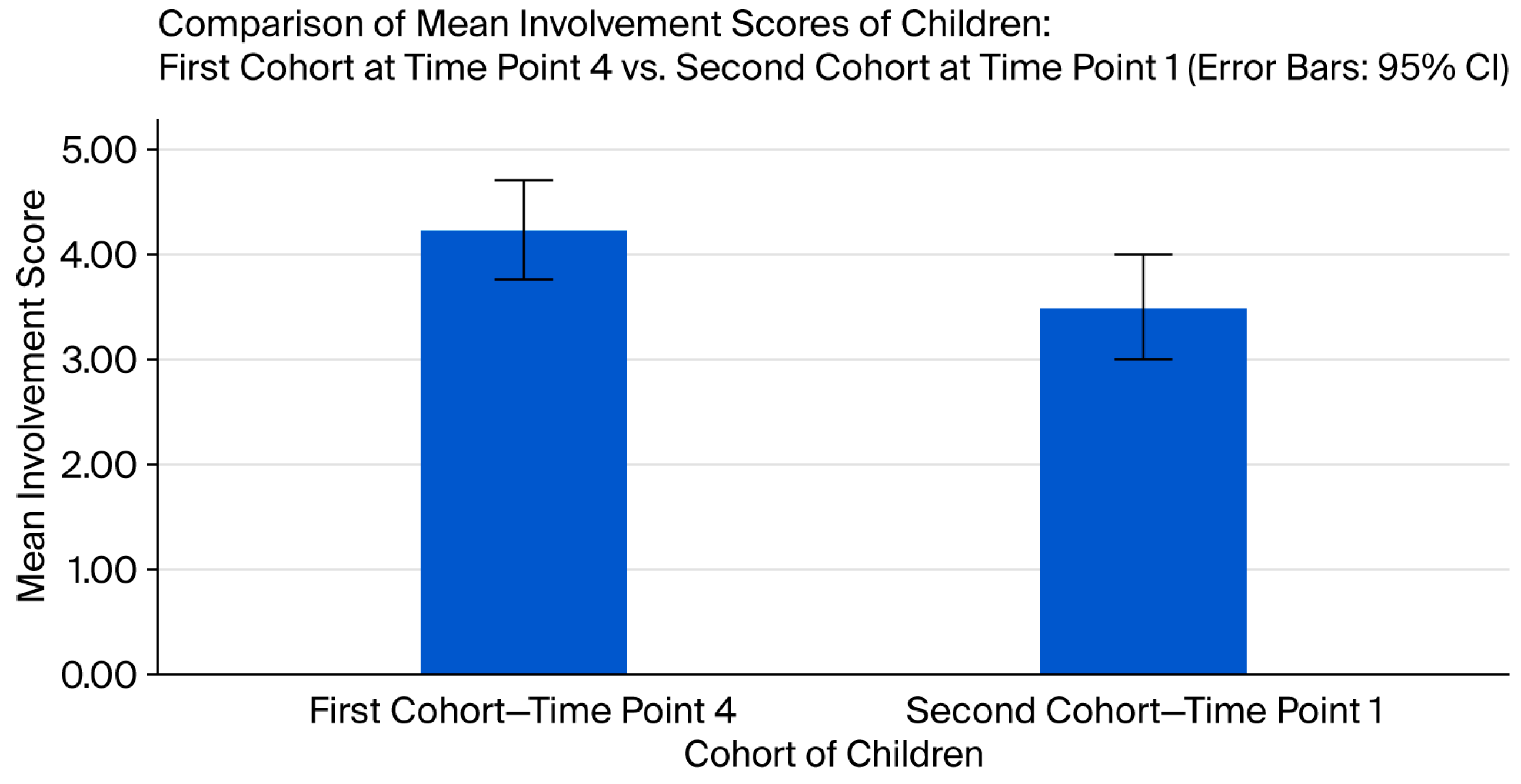

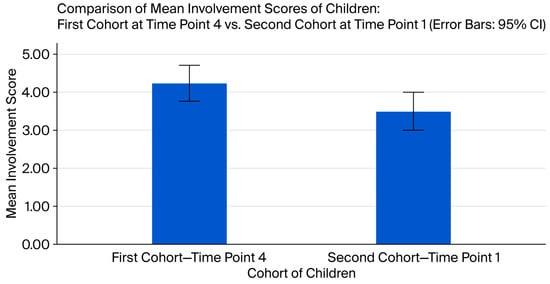

Our quantitative analysis compares the Involvement scores of children in the first cohort at time point 4 (with more than 30 h of free play) and those in the second cohort at time point 1 (with less than 10 h of free play). At the time when the measurements were taken, there was no significant difference in the age (in months) of the two cohorts of children, t(14) = 0.836, p = 0.417. Table 2 presents the mean Involvement scores for both cohorts at different time points. Followed by a normality check using Shapiro–Wilk Test, an independent sample t-test revealed that the Involvement score of children in the first cohort at time point 4 (N = 9, M = 4.24, SD = 0.617) was significantly higher than those in the second cohort at time point 1 (N = 7, M = 3.51, SD = 0.540), t(14) = 2.49, p = 0.026. This finding suggested that children who participated in more than 30 h of free play sessions demonstrated a higher level of attention compared to those who experienced less than 10 h of free play sessions. Figure 2 graphically compares the mean Involvement scores between the two cohorts.

Table 2.

The Involvement scores of participating children in both cohorts at all four time points.

Figure 2.

Mean involvement comparison chart. Note: A comparison chart of the mean Involvement scores of children in the first cohort at time point 4 (having participated in more than 75% of the free play sessions) and those in the second cohort at time point 1 (having participated in less than 25% of the free play sessions).

Our qualitative findings revealed that children could progress from solo play or playing with primary care takers to playing with peers and other adults actively in the Playlab after ten sessions of free play. It was written in the teacher’s reflective journal at the 12th session of the first cohort that, “…there were more laughters and giggles amongst children in today’s play session. The children were lying in the ball pit and threw the balls to one another… the play activity lasted longer than before” (reflective discussion report). The teacher told the research team that the children started to improvise in their play, that they were very attentive, and that they even extended their play activity in the later parts of the free play sessions. “…this group of children were interested in digging out toy animals from the mud, I added another basin of water for the children to wash the animals, then put shaving foam near the basin for the children to clean the toy animals. The children were very engaged and some children started making a farm for the toy animals using a cardboard box, one of them told the others to put the horses in, ‘they (the animals) stayed here and the dog outside’….” (from reflective report and video transcription of the first cohort).

There were no differences in the chronological age when the children of the second cohort joined in the play programme; regarding play behaviour, the children in the first few sessions of the second cohort “…were found still sticking with their primary care takers, cried and snatched the play materials from one another…their attention was short…”. It was written in the teacher’s reflective journal that “The play behaviour appeared to be solo, accidental and without focus; they seemed to repeat the play pattern of the children of the first cohort when they first came to the Playlab” (teacher’s reflective journal of the second cohort). After more play sessions, the teacher told the research team that “the children became familiar with each other, even the B7 (who cried in the first few sessions) could play water in the water- fountain alongside with other children now…He seems quite enjoyable…” (discussion report and the transcription of the video clips). In other words, B7 did not cry, could keep playing in the water fountain, and his attention was prolonged. Moreover, the teacher added a trolley in the supermarket, and it was seen that B7 (who was weaker physically) loved to push the trolley and walk around the Playlab. He could move and explore more in the Playlab at his own pace with the support of the trolley.

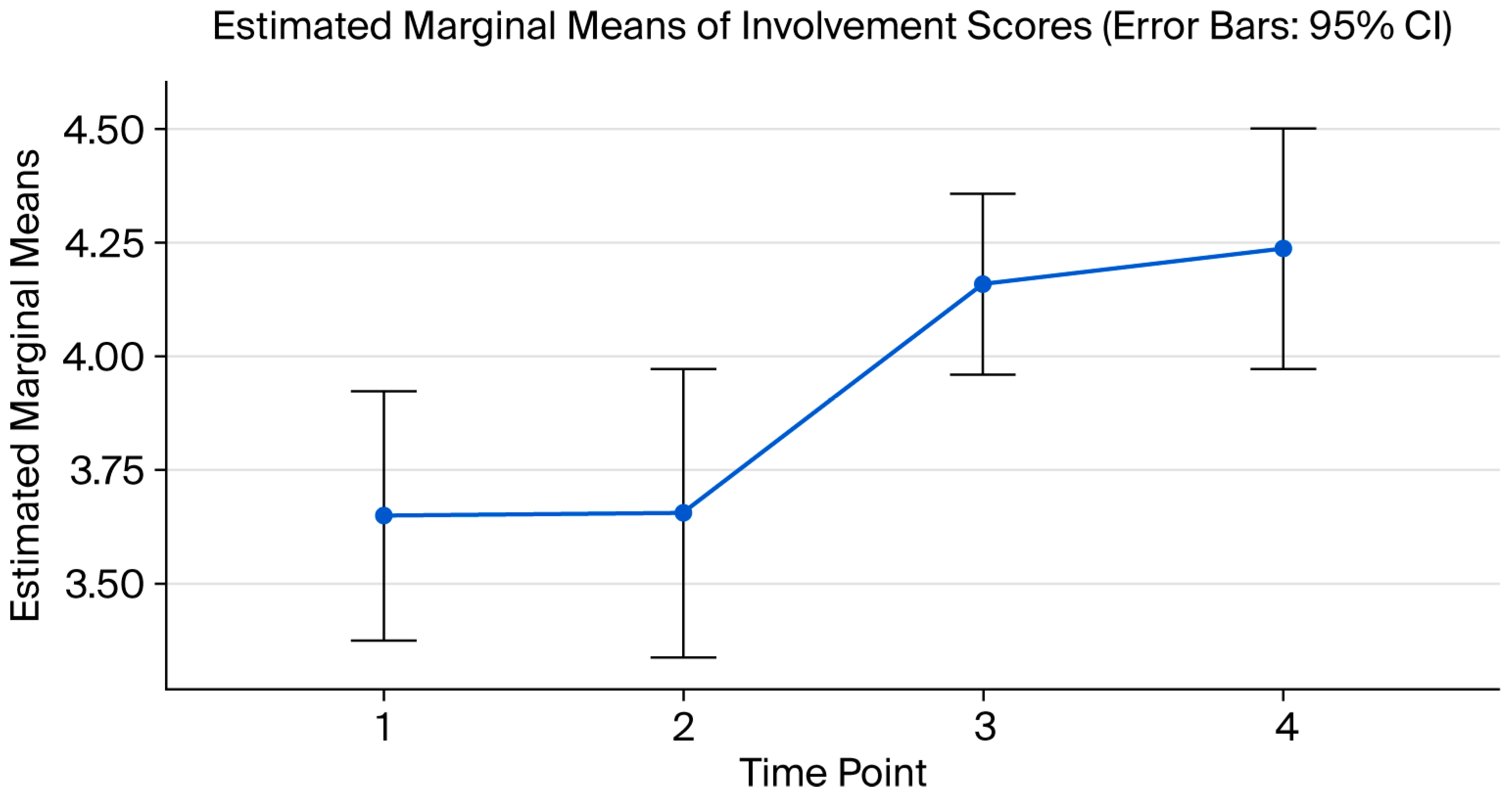

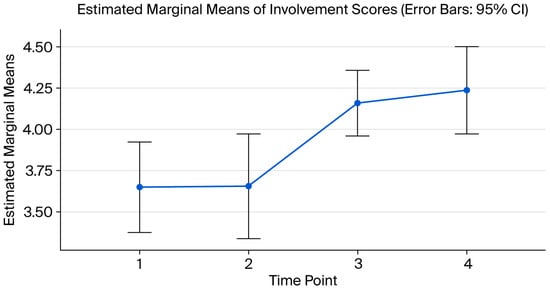

4.2. Playfulness Promotes Attention and Adequate Timing for Children to Play Serves as an Incubator of Intense Attention

We additionally examined the progressive development of the Involvement scores of children across the four time points in the 40 h free play sessions. Each time point followed 10 additional hours of free play sessions, allowing us to assess whether increased exposure to free play can enhance attention. Following the Shapiro–Wilk Test for the normality of Involvement scores and the Mauchly’s Test for the assumption of sphericity, a repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on all children in both cohorts (N = 16). The repeated-measures ANOVA showed that the mean Involvement score differed across four time points (F(3, 45) = 8.872, p < 0.001), with a large effect size ( = 0.372). A post hoc pairwise comparison using Bonferroni correction showed no significant difference in the Involvement score between the first and the second time points (3.65 vs. 3.65, p = 1) and between the third and the fourth time points (4.16 vs. 4.24, p = 1); however, there was an increase in the Involvement score from the first to the third (3.65 vs. 4.16, p = 0.01) and the fourth time points (3.65 vs. 4.24, p = 0.014), and an increase from the second to the third (3.65 vs. 4.16, p = 0.038) and the fourth time points (3.65 vs. 4.24, p = 0.034). Figure 3 presents the profile plot of the estimated marginal means of the Involvement scores at four time points, with a 95% confidence interval, demonstrating a specific pattern in the development of attention levels. The increase in the Involvement scores, and thus the level of attention, is not significant in the first 20 h, but after children were engaged in more than 50% (approximately 20 h) of free play activities at time points 3 and 4, their level of attention significantly improved. Such increase in the Involvement scores after children engaging in more than 20 h of free play activities revealed that an increased exposure to free play contributed to the observed gains in attention level, providing evidence consistent with a causal effect of free play engagement on children’s attention.

Figure 3.

A profile plot of the estimated marginal means of Involvement scores at four time points.

Aligning with the quantitative findings, the qualitative data showed that children needed time to familiarise themselves with the environment. From video data, it took two to three play sessions for children to progress from playing with objects and toys with their primary caregivers to exploring the toys and objects themselves. Shared by the teacher to the research team, “most children attempted to play with objects and toys first, proceeding to more vigorous and physically playful activities when they were familiar with the environment in the Playlab”. Consistent with the quantitative findings showing that children’s Involvement scores had noticeable changes after 10 play sessions, the teacher told the research team at the 12th play session that “most of the children could communicate and play with other children in the Playlab. There were laughters and giggles when children gathered in the ball pit or having water play…they played very long there” (discussion report). These results demonstrated that timing is a significant factor when teachers want to maximise the benefits of play for children. This might be because children can enter into a state of playfulness after playing for a period of time. Moreover, the results suggested that a state of playfulness correlates with the intensity of attention. The longer the children were immersed in a state of playfulness, the more attentive and concentrated they would become.

4.3. Children Have Different Characteristics and Immerse in a State of Playfulness Differently

Qualitative data showed that children progress towards play differently, both in duration and intensity. Sharing her observation, the teacher told the research team that “… most children attempted to play with objects and toys first, proceeding to more vigorous and physically playful activities when they were familiar with the environment in the Playlab…However, there was a child who was taller and more agile than average and that was A1. He moves fast, can jump high and he turns to playing physical activities more…Yet, B7 who cried when he first joined us, is stilling walking not that steady at the end of the programme. His exploration scope is limited…” (discussion report). Some children were easily distracted, while others had continuous concentration and sustained intense concentration. Moreover, children differed in their socialisation processes. While some were still sticking with their caregivers, others began to mingle with their peers and the adults around them after several sessions in the Playlab. Diverse cases could be identified in the teacher’s journal: the teacher wrote that “A9 was sticking in the corner with the puzzles after playing several times of the sessions…he was not that engaged…, but when his auntie came with him, he tried to explore around the room as he was brought up and looked after by his auntie since birth. His mom was a working mom.” Due to their background, it might take longer for some children to develop a perceived sense of safety to explore the play activities in the environment (Mukherjee et al., 2023).

4.4. Understanding of Each Playing Child Is Crucial for Quality Interaction Between the Child and the Teacher

To prolong children’s state of playfulness and realise their development of attention, the teacher used different approaches during the free play sessions. Due to developmental differences and differences in experience, children’s interests varied. Some children liked playing with vehicles, while others liked fixing puzzles or staying in the home corners for most of the time. The qualitative findings showed that the teacher’s keen understanding of each playing child appeared to be crucial in facilitating and prolonging the child’s state of playfulness. The teacher shared her experience of trying to understand the different characteristics of children and facilitate prolonging their playfulness; she said, “children’s attention was found differed in length and depth as we could find that B6 had a sustained intensive attention when he was involved with vehicles e.g., today, I made a virtual gas station in the Playlab, B6 took his self-made car near the gas station and was absorbed in car washing activity…. He scrubbed the car systematically and then rinsed it thoroughly. He was so involved in the activity that he would not be disturbed but continued with his car washing…” (teacher’s reflective journal). The results showed that a professional teacher, who is observant and can understand individual children’s needs and their ways of expressing themselves, is vital when interacting with children during play.

4.5. Interweaving the Environmental Inputs to Sustain the Interests of a Playing Child Is Necessary in Achieving Playfulness and Hence Attention

Qualitative data demonstrated that the teacher in this study, with a keen understanding of each child, focused on capturing, sustaining and extending children’s interests by using various environmental inputs while the children were playing in the Playlab. These inputs aim to sustain the interests of children to achieve playfulness. The employed strategies include, first, setting up stimulating contexts and providing meaningful content to elicit the prior experience of the children. With the knowledge of the age of the children joining the play sessions, the teacher first designed the Playlab based on the developmental abilities and past experiences of the children. Then, special areas were set up, such as the home area, the supermarket and ball areas. The designed contexts were often modelled on realistic ones, for example, supermarkets, parks, and cooking and dining areas, in order to arouse the prior experience and interests of the children. However, these areas were not fixed; they were environmental inputs used to weave children’s interests to allow them to reach a state of playfulness. For instance, the teacher wrote in her reflective journal that “I could see that some children used spoon to scoop the plushed balls in the ball area, some liked to put ping pong balls inside the milk-can and tossed them while others picked up the plastic balls and rolled on the floor; later, some children took the balls to the home corners and cooked them, they served the balls as eggs…Yet, there were children who always clung to their caregivers and did not participate or explore the environment themselves… I then brought in different kinds of balls and provided more utensils for children to continue with the playful activities. It was found that those who did not join in at first, started looking around to follow the rolling balls…” (the discussion report of the second cohort). In another instance, the teacher, during the reflection meeting with the research team, said that “I found that children seemed to lose their interest in the home area as less children went in these days…. I, then, placed an audio recorder of a baby’s crying soundtrack and played it in the home corner to attract children to go in… It was found that children went in again and started their role play of a family…” (discussion report of the first cohort). The addition of an audio recording near the home corner successfully extended children’s interests and hence their playfulness. Moreover, by using a virtual background, the teacher could sustain the interests of a boy who already demonstrated sustained, intense attention, prompting him to continue with his car-washing activity.

Additionally, the teacher continuously incorporated physical and cognitive challenges in order to extend children’s playfulness while they were playing. For instance, balloons were tied to the lower and upper parts of a climbing ladder to accommodate children with different motor abilities. Verbal challenges were also adopted by the teacher, exemplified by an instance when one of the children kept looking out of the window to observe the vehicles outside. The following dialogue shows the verbal challenge adopted by the teacher to extend the child’s playfulness:

Child: Baa baa.Teacher: What do you see?Child: Train! Car!Teacher: Where’re they?Child: (points). (There were cars, trucks…and trains outside the window but the child was gazing at the train station).Teacher: Do you see the train all the time?Child: (shakes his head) … wait, wait…(From video transcription)

In summary, the above findings reveal the complex skills used by the teacher to tactfully capture, sustain, and extend children’s playfulness using the available resources. When the playfulness of the children was prolonged, their attention automatically deepened and became more intense.

5. Discussion

The results of the study point to the fact that when children are provided with a free play environment, where time and resources are tactfully used, they are more likely to progress to a state of playfulness, which in turn enhances their attention. From our longitudinal quantitative data analysis, the repeated-measure ANOVA revealed a significant effect, indicating that playfulness promotes attention. The observed effect size was large, with being 0.372, which corresponds to a Cohen’s f of approximately 0.77. Due to the large observed effect, a post hoc power analysis conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., 2007) indicated an achieved power close to 1 (based on our study design with 16 participants, 4 time points, = 0.05, and an observed effect of being 0.372). This suggests that the study was statistically well-powered to detect the observed effect.

We argue that play, especially its benefits for young children’s development and learning, is complicated. Indeed, teachers across different countries found it hard to position themselves when supporting children to learn through play in their curriculum (Bubikova-Moan et al., 2019). When studying play, past studies tend to focus on its form, for example, explaining the spectrum of play (Zosh et al., 2018), ranging from free play to guided play and structured play (Weisberg et al., 2013). However, the core essence of play, reaching a state of playfulness, which leads to its most significant benefits, has been neglected.

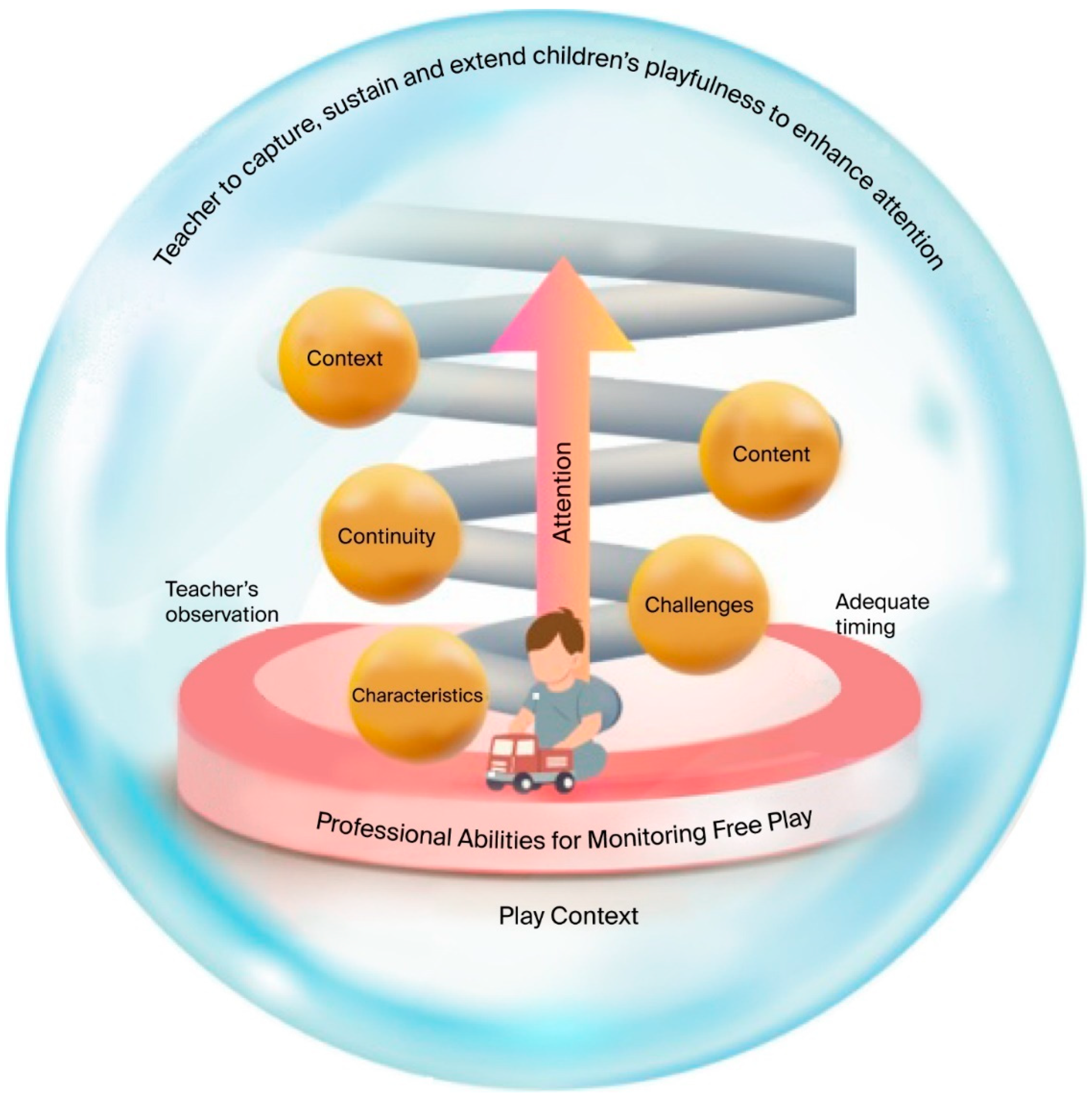

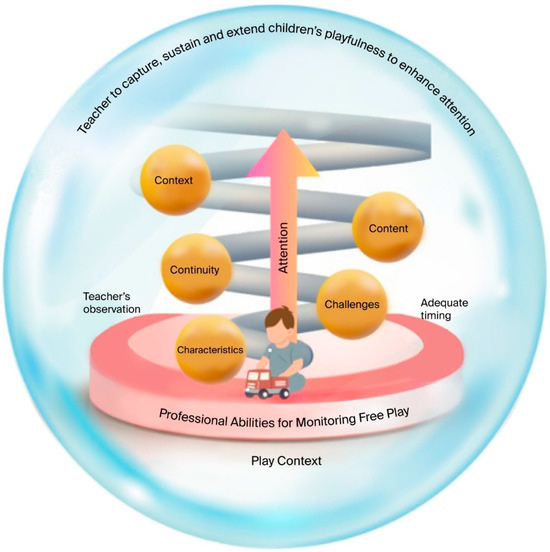

5.1. Playfulness Realisation Framework—A Framework to Nurture Playfulness in Order to Enhance Children’s Attention

Based on our findings, we identified several essential key pedagogies employed by the teacher to establish a free play environment that fosters playfulness and thus enhances children’s attention. To illustrate the dialectical interaction between environmental inputs in the context of play and the achievement of children’s playfulness, we propose a Playfulness Realisation Framework, which is depicted in Figure 4. Firstly, a child needs to be provided with an environment that allows the development of playful interests. Secondly, a professional teacher/educator is needed to observe and capture the child’s playful interests during a sufficiently long play session; sustain their interests by managing environmental resources; and lead by following the interests of the child in a dialectical manner. Thirdly, there should be a continuous interplay between the child’s interests and the teacher’s pedagogical inputs to support internal joy, the state of playfulness, which enhances their attention. For practical implementation, based on our findings and inspired by the work of Herrington and Lesmeister (2006), we further illustrate the continuous interplay between children’s interest and teachers’ pedagogical inputs via a 5Cs model, which is shown below.

Figure 4.

The Playfulness Realisation Framework.

5.2. The 5Cs Model to Nurture Playfulness in Order to Enhance Children’s Attention

Characteristics of the Child. The findings showed that children were different and unique, though they had the same chronological age. They had different inherited characteristics, interests, temperaments, and life experiences prior to coming to the Playlab. While some children were timid and stuck to their caregivers, others had developed their interests, such as playing with vehicles, puzzles, and reading stories. Children had different characteristics, and thus, the teacher had to observe the uniqueness of each child and note these differences while tailoring the environment to arouse children’s interest in play.

Context. As mentioned, the teacher had to understand the unique interests and life experiences of each child to design and provide adequate contexts that would elicit and capture the children’s attention and facilitate their playful activities. The designed context was often modelled on realistic ones, for example, supermarkets, parks, and cooking and dining areas, in order to arouse children’s prior experience and interests. Of course, adequate timing was one of the necessary criteria for children to familiarise themselves with the context. With the development of IT, virtual contexts were also possible. The designed context helped to connect children’s experiences and could be altered to sustain and extend their interests.

Content. Context and content were highly interconnected. Depending on the context, different content was needed to realise it; e.g., a cashier station and different kinds of foods and drinks were necessary for a superstore, and a cooking stove, sink, and dining table were the suggested contents of a home area. However, the contents could be real objects or semi-structured ones to accommodate children’s imagination, as we could not completely comprehend every child’s experience. While the content of the play area might attract the initial interest of children, it can also be used to sustain and extend children’s playfulness, for example, the baby soundtrack in the home area.

Challenges. Our research team found that without taking risks, children cannot reach their full playfulness. Hence, as Johnson et al. (1987) noted, “Due to the uniqueness of each child, the settings should enable each child to find an optimal level of challenge.” Hence, different kinds and levels of physical and cognitive challenges were needed in the play environment. The teacher in this study continuously added new challenges to the play areas in order to sustain children’s interests and extend their sense of involvement. It was found that challenges could be in the form of context, content, or the dialectical interaction between the teacher and children, for instance, the dialogue between the teacher and the children when watching the vehicles and the balloons tied to different levels of the ladder.

Continuity. Though continuity is listed as the last notion of the 5Cs model, it is one of the core concepts when nurturing playfulness. As playfulness connects one’s affective, physical, and cognitive domains, it needs time to develop. Hence, the facilitation of a teacher is needed to support the development of playfulness. The teacher needs to devise multiple ways to revisit children’s interests and joyful experiences to make sense of them, while at the same time generating means to build their prior interests and evolving joyful experiences to support the integration of the children’s internal feelings with their external playful environment (Cheng, 2010). For example, the teacher put shaving foam in a basin of water when she found that the children were interested in playing with the animals and played a baby’s crying soundtrack for the children to continue with the family role play.

While the 5Cs are identified as a significant strategy adopted to nurture playfulness, we must bear in mind that the 5Cs model needs to be applied without infringing on children’s agency; otherwise, children’s “playfulness” can be jeopardised. This study shows that the teacher tactfully made sense of the 5Cs using her keen observations, spontaneously supplying new content and altering the context according to the interests of the children. Thus, the pedagogical strategies used by the teacher were the most significant factors in promoting children’s playfulness and thus enhancing their attention.

6. Limitations

Although our study revealed a significant result with a large observed effect size, indicating that playfulness promotes attention, we acknowledge several limitations. First, despite the high observed power, a small sample may fail to capture the full variability of the population. It is possible that the observed effect size was inflated due to chance, and the statistical power could be overestimated. Second, the limited sample size restricts the generalisability of our findings. The results may not extend to broader populations with greater diversity of the children’s developmental, cultural, and contextual backgrounds. Third, although standardised procedures and guidelines were provided to the two research assistants conducting observations and writing reflections, data collection may still be influenced by the researcher bias, with a risk of interpreting responses in ways that confirm pre-existing hypotheses.

In future research, we aim to conduct the study with a larger sample to enhance reliability, recruit children with more diverse background to improve the generalisability, and assess inter-rater reliability to quantify and minimise observer bias.

7. Conclusions

Our study provides evidence that children’s attention levels are enhanced when they engage in free play activities. Enhancing children’s attention is crucial for improving their EF skills and later educational performance. In addition, this study demonstrated the teacher’s tactful pedagogical skills, which are crucial to achieving the benefits of play in a free play environment. We would like to reiterate the importance of children’s agency in promoting playfulness, as highlighted in the aforementioned literature, as true play needs to be viewed from the child’s perspective, not the teacher’s perspective. Thus, the ability to understand children’s “here and now behaviour” while, at the same time, responding to their interests, without disrupting their agency, is vital to maximise the true benefits of free play. Our study proposes a Playfulness Realisation Framework with a 5Cs model for front-line teachers to implement free play. The framework shows the dialectical interactions between environmental inputs in the play context and the development of children’s playfulness, while the 5Cs model highlights the key skills for teachers to realise the potential benefits of free play. Lastly, from a research perspective, we plan to extend in future work by conducting a similar study with a larger sample. We also hope that researchers will continue to discover more tactful pedagogies that can bring out the true benefits of play in nurturing children’s attention and their overall development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T., P.L. and A.K.-Y.T.; Data curation, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T. and P.L.; Formal analysis, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T. and P.L.; Funding acquisition, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T. and P.L.; Investigation, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T., P.L. and A.K.-Y.T.; Methodology, D.P.-W.C. and M.C.-M.T.; Project administration, D.P.-W.C. and P.L.; Resources, D.P.-W.C.; Supervision, D.P.-W.C.; Validation, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T. and P.L.; Visualization, M.C.-M.T. and A.K.-Y.T.; Writing–original draft, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T., P.L. and A.K.-Y.T.; Writing–review & editing, D.P.-W.C., M.C.-M.T., P.L. and A.K.-Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is supported by a Catholic organisation from Europe and the Hong Kong University Grant Council Research Matching Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975. The research protocol was approved by the Research Office of Tung Wah College prior to the commencement of the project on 1 January 2020. The College’s Regulations on Child Protection, which aligned with the child safeguarding policy of the funding body was duly followed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Due to the sensitive nature of the data involving children, and in accordance with ethical guidelines and privacy regulations, the data are not publicly available to protect participant confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Playlab Observation Sheet, with the Section About Involvement Enlarged

References

- Berk, L. E., & Meyers, A. B. (2013). The role of make-believe play in the development of executive function: Status of research and future directions. American Journal of Play, 6(1), 98. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. S. (1972). Nature & uses of immaturity. American Psychologist, 27, 687–708. [Google Scholar]

- Bubikova-Moan, J., Næss Hjetland, H., & Wollscheid, S. (2019). ECE teachers’ views on play-based learning: A systematic review. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(6), 776–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D. L., Schnellert, L., & Perry, N. E. (2017). Developing self-regulating learners. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, S. M., Zelazo, P. D., & Faja, S. (2013). Executive function. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology (pp. 706–743). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre on the Developing Child. (2011). Building the brain’s ‘air traffic control’ system: How early experiences shape the development of executive function. Working Paper No. 11. Harvard University. Available online: https://developingchild.harvard.edu (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Cheng, P. W. D. (2001). Difficulties of Hong Kong teachers’ understanding and implementation of ‘play’ in the curriculum. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P. W. D. (2010). Exploring the tactfulness of implementing play in the classroom: A Hong Kong experience. Asia Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P. W. D. (2011). Learning through play in Hong Kong: Policy or practice? In S. Rogers (Ed.), Rethinking play and pedagogy in early childhood education: Concepts, contexts and cultures (pp. 100–111). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P. W. D., Leung, S. Y., & Law, H. H. (2022). The implementation of free play: An explorative study on a child-centered play in Hong Kong. Tung Wah College. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P. W. D., Reunamo, J., Cooper, P., Liu, K., & Vong, P. (2015). Children’s agentive orientations in play-based and academically focused preschools in Hong Kong. Early Child Development and Care, 185(11–12), 1828–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffino, J. R., & Bailey, C. (2019). The Anji Play ecology of early learning. Childhood Education, 95(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliver, Y., Harrison, L. J., Brown, J. E., & Humburg, P. (2022). Free play predicts self-regulation years later: Longitudinal evidence from a large Australian sample of toddlers and preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 59, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rathunde, K. (1993). The measurement of flow in everyday life: Toward a theory of emergent motivation. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 57–97). University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dankiw, K. A., Tsiros, M. D., Baldock, K. L., & Kumar, S. (2020). The impacts of unstructured nature play on health in early childhood development: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0229006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockett, S. (2011). The challenge of play for early childhood educators. In S. Rogers (Ed.), Rethinking play and pedagogy in early childhood education: Concepts, contexts and cultures (1st ed., pp. 32–47). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center [ECTA Center]. (2017). Following the child’s lead. Available online: https://ectacenter.org/~pdfs/decrp/PG_Ins_FollowingYourChildsLead_family_mobile_2017.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Education Bureau. (2020). Pre-primary children development and behaviour management—Teacher resource kit. Available online: https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/edu-system/preprimary-kindergarten/comprehensive-child-development-service/index.html (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleer, M. (2011). ‘Conceptual play’: Foregrounding imagination and cognition during concept formation in early years education. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 12(3), 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J. L., Cornell, M., & Gill, T. (2017). A systematic review of research into the impact of loose parts play on children’s cognitive, social and emotional development. School Mental Health, 9(4), 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, K. R., American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Communications & American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J. (2012). Play in development, health, and well-being. Toy Industries of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Play, 3(4), 443. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K. (2016). Supporting executive function skills in early childhood: Using a peer buddy approach for community, confidence, and citizenship. Journal of Education and Training, 3(1), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassinger-Das, B., Toub, T., Zosh, J., Michnick, J., Golinkoff, R., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2017). More than just fun: A place for games in playful learning/más que diversión: El lugar de los juegos reglados en el aprendizaje lúdico. Journal for the Study of Education and Development Infancia y Aprendizaje, 40(2), 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, K. S., & Roepstorff, A. (2018). How playfulness motivates—Putative looping effects of autonomy and surprise revealed by micro-phenomenological investigations. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, S., & Lesmeister, C. (2006). The design of landscapes at child-care centres: Seven Cs. Landscape Research, 31(1), 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R. M., Pellegrini, A. D., & Schmidt, S. L. (2006). The effects of different recess timing regimens on preschoolers’ classroom attention. Early Child Development and Care, 176(7), 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. E., Christie, J. F., & Yawkey, T. D. (1987). Play and early childhood development. Scott, Foresman & Co. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. R. (1979). Play: The kindergartners’ perspective. The Elementary School Journal, 80(2), 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakow, J. B., & Kopp, C. B. (1982). Sustained attention in young down syndrome children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 2(2), 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakow, J. B., & Kopp, C. B. (1987, April 23–26). The importance of sustained attention throughout the early years [Paper presentation]. Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard, A., & Else-Quest, N. (2006). Evaluating Montessori education. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), 313(5795), 1893–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Hassan, N. M., & Luen, L. C. (2023). Developmental trends of executive function in Chinese preschool children. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 12(3), 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masek, L., & Stenros, J. (2021). The meaning of playfulness: A review of the contemporary definitions of the concept across disciplines. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, 12(1), 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., Connor, C. M., Farris, C. L., Jewkes, A. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2007). Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S., Bugallo, L., Scheuer, N., Cremin, T., Montoro, V., Ferrero, M., Preston, M., Cheng, D., Golinkoff, R., & Popp, J. (2023). Conceptions of play by children in five countries: Towards an understanding of playfulness [las concepciones acerca del juego de niños de cinco países: Hacia un mejor conocimiento de la actividad lúdica]. Journal for the Study of Education and Development Infancia y Aprendizaje, 46(1), 109–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, C., Grau-Sevilla, M., McWilliam, R., & García-Grau, P. (2020). Quality of the early childhood education environment and interactions, and their relationship with time dedicated to free play [calidad del entorno y de las interacciones en educación infantil y su relación con el tiempo dedicado al juego libre]. Journal for the Study of Education and Development Infancia y Aprendizaje, 43(2), 395–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2003). Do children’s attention processes mediate the link between family predictors and school readiness? Developmental Psychology, 39(3), 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2006). Starting strong II: Early childhood education and care. OCED Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2006/09/starting-strong-ii_g1gh7238/9789264035461-en.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Parker-Rees, R. (1999). Protecting playfulness. In L. Abott, & H. Moylett (Eds.), Early education transformed (pp. 61–72). Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pellis, S. M., & Pellis, V. C. (2007). Rough-and-tumble play and the development of the social brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 16(2), 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A., Miranda, S., Teixeira, S., Mesquita, S., Zanatta, C., & Rosário, P. (2021). Promote selective attention in 4th-grade students: Lessons learned from a school-based intervention on self-regulation. Children, 8(3), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook, Trans.). W.W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. Norton Library. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, A., & Danniels, E. (2017). A continuum of play-based learning: The role of the teacher in play-based pedagogy and the fear of hijacking play. Early Education and Development, 28(3), 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S., & Evans, J. (2008). Inside role-play in early childhood education: Researching young children’s perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostan, C., Caballero, F., Serrano, J., Amadó, A., Vallès-Majoral, E., Esteban, M., & Serrat, E. (2014). Fostering theory of mind development. Short- and medium-term effects of training false belief understanding/favorecer el desarrollo de la teoría de la mente. Efectos a corto y medio plazo de un entrenamiento en comprensión de la falsa creencia. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 37(3), 498–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K., Fein, G., & Vandenberg, B. (1983). Play. In E. Mavis Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 4: Socialization, personality and social development (pp. 693–774). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff, H. A., Capozzoli, M., & Weissberg, R. (1998). Age, individuality, and context as factors in sustained visual attention during the preschool years. Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, I. P., & Carlsson, M. A. (2008). The playing learning child: Towards a pedagogy of early childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(6), 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. K. (2003). Evolutionary developmental psychology and socio-emotional development. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 26(3), 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarman, B., & Tarman, I. (2011). Teachers’ involvement in children’s play and social interaction. Elementary Education Online, 10(1), 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2018). Learning through play. Strengthening learning through play in early childhood education programmes. UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2018-12/UNICEF-Lego-Foundation-Learning-through-Play.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- UNICEF. (2022, February 12). The science of play: It’s not just fun—It’s fundamental to your child’s development. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/parenting-lac/early-learning/science-play-child-development (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Van Lier, P. A. C., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2016). Children’s elementary school social experience and executive functions development: Introduction to a special section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. (1991). The tact of teaching: The meaning of pedagogical thoughtfulness. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1966). Igra i ee rol v umstvennom razvitii rebenka [Play and its role in mental development of the child]. Voprosy Psihologii [Problems of Psychology], 12(6), 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, & S. Scribner, Eds.; 1st ed.). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg, D. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2013). Guided play: Where curricular goals meet a playful pedagogy. Mind, Brain and Education, 7(2), 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebread, D., Coltman, P., Jameson, H., & Lander, R. (2009). Play, cognition and self-regulation: What exactly are children learning when they learn through play? Educational and Child Psychology, 26(2), 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebread, D., & Jameson, H. (2010). Play beyond the foundation stage: Story-telling, creative writing and self-regulation in able 6–7 year olds. In J. Moyles (Ed.), The excellence of play (3rd ed., pp. 95–107). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zosh, J. M., Hassinger-Das, B., & Laurie, M. (2022). White Paper: Learning through play and the development of holistic skills across childhood. LEGO Foundation. Available online: https://cms.learningthroughplay.com/media/kell5mft/hs_white_paper_008-digital-version.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Zosh, J. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Hopkins, E. J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Solis, S. L., & Whitebread, D. (2018). Accessing the inaccessible: Redefining play as a spectrum. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zych, I., Ruíz, R. O., & Sibaja, S. (2016). Children’s play and affective development: Affect, school adjustment and learning in preschoolers/el juego infantil y el desarrollo afectivo: Afecto, ajuste escolar y aprendizaje en la etapa preescolar. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 39(2), 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).