Abstract

The emergence of generative AI, particularly the widespread accessibility of ChatGPT, has led to challenges for higher education. The extent and manner of use are under debate. Local empirical investigations about the use and acceptance of ChatGPT contribute to effective policymaking. The study employs a specialized approach, utilizing an information system view based on the DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success Model as its theoretical framework. A survey was conducted to assess students’ opinions about ChatGPT regarding its usefulness in their studies. The model was tested using PLS-SEM with 466 Hungarian and Romanian higher education students. The model examined six constructs as information quality, system quality, service quality, use, user satisfaction, and net benefits. The results confirmed the effects of information quality and system quality on use and satisfaction, whereas service quality did not make a significant contribution. Satisfaction was found to be the key driver to use. The study contributes to a deeper understanding of AI acceptance in higher education and provides valuable considerations for policymaking. A data-oriented, task-focused policymaking is recommended over system-based regulation. Additionally, a comprehensive framework model is required for international comparisons, which combines information systems success and technology acceptance models.

1. Introduction

Information has become a key asset in the world. Access to reliable, accurate, secure, and timely information is not a new phenomenon; it is a historical fact. However, technological development has made it possible to generate more and more data, and the availability of the dataset generates new challenges (T. Xu et al., 2024). It has been a long and continuously accelerated journey from the development of speech through writing to today’s electronic communication and the information age. We have reached the age of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) (Sengar et al., 2024). The increased amount of data requires an information system to systematize the data and its usability for different personal or organizational purposes. Some decades ago, there were enough sheets of paper, while today we manage automated databases, the Internet, and the Internet of Things sources (Cantamessa et al., 2020). The demand for automating processes is mirrored in technological advancements in the fields of production and information management, described by Industry 4.0 (Folgado et al., 2024; Ustundag & Cevikcan, 2018; Zhang et al., 2024).

Overall, artificial intelligence is not a new invention; it has been developed over decades (García-Peñalvo & Vázquez-Ingelmo, 2023; Nayak & Walton, 2024). Nevertheless, GenAI, especially the introduction of ChatGPT 3.5 (Buruk, 2023), has built a broad audience and popularity for this technology. The impact of GenAI is well-documented by the growing scientific interest (Bettayeb et al., 2024; Hussein et al., 2025; Sengar et al., 2024). The opportunities are promising, the social impacts, especially in the labor market, are frightening, and the lessons are mixed (Farrokhnia et al., 2024; Lo, 2023; Zhou et al., 2024). Based on a literature review, Hussein et al. (2025) demonstrated that education and health are the top themes related to ChatGPT, emphasizing the transformative impacts on teaching, learning, and academic work. Through this, a new generation will be influenced by this technology and will adopt it in their work and personal lives.

As with all new technologies, in addition to the potential uses, safety and reliability issues, as well as ethical concerns, arise (Hua et al., 2024; Hussein et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2024). Despite the remarkable efforts made by international organizations, governments, and local institutions in policymaking (Hussein et al., 2025; Weis et al., 2026; Zhou et al., 2024), a comprehensive and effective solution requires further investigations. The need for regulations and user training is obvious to enjoy the benefits and improve social utility. Understanding the factors that influence use and satisfaction with a technology plays a crucial role in its further development and utilization. Behavioral (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) and technology acceptance models (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003, 2012) are popular for exploring the topic, but these are limited to personal aspects. A somewhat different approach has been proposed in the information systems success model by DeLone and McLean (DeLone & McLean, 1992, 2003; Marjanovic et al., 2024). That model is less prevalent for GenAI software usage investigations, but it can provide valuable contributions to the knowledge base. In a narrower sense, chatbots and other GenAI services cannot be considered information systems, although from the user’s viewpoint, they operate similarly to an information system. According to Stair and Reynolds (2018, p. 7) “an information system (IS) is a set of interrelated components that collect, process, store, and disseminate data and information; an information system provides a feedback mechanism to monitor and control its operation to make sure it continues to meet its goals and objectives”. GenAI services collect, process, and disseminate data, but there is no data storage. Another difference is based on using a probabilistic language model instead of a structured database; however, from the users’ perspective, that may mean more opportunities than constraints, since the purpose of decision-making support is available. Based on the above, however, the information system approach is not the mainstream understanding of GenAI use; it is worth not rejecting. Some authors (B. Chen et al., 2023; Chu, 2023; Marjanovic et al., 2024) offer insights into the application with original or modified information systems success models.

The scope of this study is limited to the use of ChatGPT among students in higher education. ChatGPT is not an exclusive GenAI chatbot, but at the time of data collection, it played a more significant role than it does today. The academic field is significantly impacted by the growing appreciation of GenAI (Lo, 2023; Hussein et al., 2025; Strzelecki, 2024; Lee & Esposito, 2025), including the production of scientific reports and student writing. Policymaking for the conscious and responsible use of GenAI is progressing more slowly than the widespread adoption of its use. Accepting that the restriction of GenAI use is meaningless and unnecessary, learning from the present experiences of students contributes to effective policies and supports awareness-raising activities.

The research question of the study is formulated as whether ChatGPT contributes to the success of higher education studies in the opinion of the students. A (PLS-SEM) model was developed based on the DeLone and McLean Information Success model (DeLone & McLean, 2003) to explore students’ assessments of information, system, and service quality, and their impact on use, satisfaction, and net benefits. The model was tested based on a sample of Hungarian and Romanian higher education students (n = 466). The study aims to contribute to the body of knowledge on GenAI use and highlight the adaptation opportunities for achieving information system success.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review of the influencing factors of ChatGPT use among students and the application of the DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success model. Section 3 presents the development of the research framework, the data collection methods, and the methods. Section 4 includes descriptive statistics and the PLS-SEM model validation. Section 5 and Section 6 summarize the evaluation of the results and the implications.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Influencing Factors of ChatGPT Use

2.1.1. Framework Models

Behavioral and technology acceptance framework models provide several latent variable constructs, but researchers are enabled to supplement the models with new elements and reconsider the influencing factors of ChatGPT use. UTAUT/UTAUT2 (Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology) (Venkatesh et al., 2003, 2012) and TAM (Technology Acceptance Model) (Davis, 1989) are the most popular initial framework models in the papers investigated, often supplemented with behavioral models (Granić, 2025; Lee & Esposito, 2025), such as Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as in (Jo, 2023; Al-Qaysi et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2024) or Self-Determination Theory (Annamalai et al., 2025; Hu et al., 2023), and with original pilot factors by the authors. The task-technology fit approach (Alfaisal et al., 2024; Salloum et al., 2024c) was also considered among the empirical research models.

Since the high degree of methodological similarity was only apparent across the wide range of papers, and the study goals are similar, the comparability of the results is limited. Review articles may support further research. A comprehensive review by Lo et al. (2024) confirmed a set of observational studies that used the TAM or UTAUT models. Although the present study uses a different approach and framework model for empirical analysis, the research design considered the constructs and questions of other models.

The positive impact on performance and academic progress of accepting and using ChatGPT is emphasized, in some models entitled learning value (Al-Maroof et al., 2024, 2024; Alshammari & Alshammari, 2024; Ayoubi, 2024; Foroughi et al., 2024; Salloum et al., 2024b; Tang et al., 2025). In addition to the effort required, user expectations must be considered a primary influencing factor in understanding the reasons. A core element of the framework models is the behavioral intention, which describes the willingness of a person to use or continue using the system, as self-declared by the person concerned (Ajzen, 1991). Efforts to use the system, expected benefits, habit, social influence, facilitating conditions, and personal factors, such as attitudes and trust, are often used to explain behavior depending on the framework model (Venkatesh et al., 2003; Isaias & Issa, 2015). However, the studies confirm the usability of ChatGPT; there is no general agreement on the effect of the factors. The information system view of ChatGPT use may bring bridging results in understanding the influencing factors.

2.1.2. Effort Expectancy and Perceived Ease of Use

Effort expectancy in the UTAUT model and perceived ease of use in the TAM model refer to the degree of ease with system use. Papagiannidis (2022) suggested this factor is expected to become insignificant when extended use of technology is reached. Although GenAI is not an old technology, it has spread quickly, as reflected in the varied results of related research reports. Tang et al. (2025) emphasized the positive impact of effort expectancy on the learning value.

Significant effects of effort expectancy on intention to use ChatGPT were reported in many countries, such as Nepal and the United Kingdom (Budhathoki et al., 2024), Malaysia (Supianto et al., 2024), Uganda (Namatovu & Kyambade, 2025), China (Hoi et al., 2023; Shahzad et al., 2024; X. Xu & Thien, 2025; Zhao et al., 2024), and in Indonesia (Habibi et al., 2023).

The similar construct, perceived ease of use, was found significant in this relation in China (Cao et al., 2023; Qu & Wu, 2024), Peru (Al-Abdullatif & Alsubaie, 2024), Jordan (Alshurideh et al., 2024), UAE (Salloum et al., 2024a), and Sri Lanka (Sabraz Nawaz et al., 2024), while Tiwari et al. (2023) found the opposite in Oman.

At the same time, contradictory findings exist in the literature. Ngo et al. (2024) emphasized the missing effect on satisfaction. Liu and Ma (2024) found that perceived ease of use affects attitude indirectly, through perceived usefulness. Alshammari and Alshammari (2024) found that perceived ease of use significantly affects satisfaction with the software, but not the intention to use, while Hasanein et al. (2024) reported the opposite. Niloy et al. (2024) argued that technical knowledge is not needed to use generative AI software. A different conclusion was drawn by Salifu et al. (2024), Alshammari and Alshammari (2024), Surya Bahadur et al. (2024), and Zhao et al. (2024).

2.1.3. Performance Expectancy and Perceived Usefulness

Performance expectancy in the UTAUT models refers to the beliefs of a person that technology or the system helps to achieve better performance (Venkatesh et al., 2003). It is adopted from the perceived usefulness in the TAM model (Davis, 1989), enhancing the attitudes interpreted by the behavioral models. These constructs are often linked to behavioral intention and actual use, and most studies report significant effects. Tang et al. (2025) confirmed its effect on learning value, and Namatovu and Kyambade (2025) revealed the significant influence of performance expectancy on adoption.

In contrast, Maheshwari (2024) found that the effect of perceived usefulness on intention to use in Vietnam was not significant; however, the conclusion was based on a relatively small sample. Surya Bahadur et al. (2024) found that neither effort expectancy nor performance expectancy had a significant impact. Alshammari and Alshammari (2024), as well as Zhao et al. (2024) emphasized the significant role of the perceived usefulness through the satisfaction of the respondents.

2.1.4. Habit

Habit refers to performing a form of behavior automatically (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Among the additional influencing factors of use or the intention to use ChatGPT, habit was identified as significant by Namatovu and Kyambade (2025), Sabraz Nawaz et al. (2024), and Strzelecki (2024). Furthermore, use was found to be significantly affected by satisfaction as reported by Ngo et al. (2024). Besides performance expectancy, habit was found to be the strongest predictor of behavioral intention (Faraon et al., 2025), and it was found to be a significant predictor by most studies in the review. Based on the PLS-SEM results, Foroughi et al. (2024) concluded that habit does not affect ChatGPT use, but the fsQCA analysis suggested that combining habit with other factors has a notable impact.

2.1.5. Hedonistic Motivation

Another construct introduced to the framework models is hedonic motivation, which refers to the “fun or pleasure” associated with using the system (Venkatesh et al., 2012). The positive significant effect of hedonic motivation on the intention to use ChatGPT was emphasized by Faraon et al. (2025), Habibi et al. (2023), Sabraz Nawaz et al. (2024), and Cai et al. (2023), while it was rejected by Surya Bahadur et al. (2024). Habibi et al. (2023) found hedonic motivation to be the most dominant influencing factor of behavioral intention.

2.1.6. Facilitating Conditions

Facilitating conditions refer to the support of system use (Venkatesh et al., 2003). It is the most counterfactual and diverse construct in the studies, with varying results. Facilitating conditions seem to be a kind of container for the genuine explanatory factors of intention to system use in research models. However, the opposite was hypothesized in the UTAUT model (Venkatesh et al., 2003), and it was found that facilitating conditions have an impact only on use (Venkatesh et al., 2012). The effect of facilitating conditions on use was emphasized by Habibi et al. (2023) and Strzelecki (2024), on intentions by Sabraz Nawaz et al. (2024) and Supianto et al. (2024), on satisfaction by Ngo et al. (2024), and on attitudes by Duong (2024). No significant effect was found by Foroughi et al. (2024), Surya Bahadur et al. (2024), Hasanein and Sobaih (2023), and Tang et al. (2025) on their outcome factors investigated.

2.1.7. Social Influence

Social influence refers to the impact of other influential individuals on the decision to use the system. (Venkatesh et al., 2003) found that the effect of social influence is significant when the use of technology is mandated. Among the investigated papers, the positive effect of social influence on the intentions or use was confirmed by Alshammari and Alshammari (2024), Budhathoki et al. (2024), Changalima et al. (2024), Jang (2024), Namatovu and Kyambade (2025), and Supianto et al. (2024). It was rejected by Foroughi et al. (2024), and Tang et al. (2025). Hasanein and Sobaih (2023) found that social influence affects intention but not use. Duong (2024) confirmed its effect on attitudes and trust in the system.

The partially different results on the influencing factors derived from the TAM or UTAUT models suggest considering another approach for building a framework model. The authors turned to the information system view.

2.2. DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success Model

Since information technology (IT) has become a fundamental pillar of modern organizations (Isaias & Issa, 2015), concerns about its effectiveness are evident. Ultimately, user perceptions and feedback are crucial for system development, as they significantly contribute to an organization’s success or failure. The model established the analysis of temporal and causal relations or the systematic examination of information systems (Seddon et al., 1999). Later, attempts were made to combine information systems, technology acceptance, and behavioral views (Abdul Wahi & Berényi, 2023; Zaied, 2012).

The DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success model (DM model) can be considered a master model in the field of information systems. The first model validated for e-commerce success included six factors (DeLone & McLean, 1992). An updated model (DeLone & McLean, 2003) reorganized the original model and expanded its scope to include new aspects. The interpretation of the constructs can be summarized as follows (based on DeLone & McLean, 2003):

- Information quality refers to the content issues.

- System quality refers to the desired and valued characteristics of the system.

- Service quality (a new construct in the updated model) refers to the support provided for effective and desired use of the system.

- Use refers to the transactions made by the system.

- User satisfaction refers to personal opinions and impressions about the system in any sense.

- Net benefit (a new construct, replacing individual and organizational impact) refers to the most important success measures, including both positive and negative, personal and organizational impacts of the system use.

A scientometric review of 511 publications between 2003 and 2021, conducted by Pushparaj et al. (2023), reported remarkable growth in the model adaptation in business and economics, information science fields, and the appearance of the model in educational relations as well. The remarkably high citation count for the paper presenting the updated model (DeLone & McLean, 2003), along with the fields of the citing papers, confirms the applicability of the information system success approach. Based on the Scopus database (as of 23 August 2025), the paper has received 8649 citations. Checking the keywords of these papers, health care system applications (“health” is mentioned 2080 times, and “medical” 819 times), and education are the most popular (“learning is mentioned 1896 times, “education” 996 times, and “e-learning” 835 times). Structural equation modeling is a key method for DM model applications. The expressions referring to the application of the PLS-SEM method were found in 1309 papers. These indicators underline the broad applicability of DeLone and McLean’s framework model.

Despite ChatGPT not being a traditional information system, it is worth turning to the information system approach, as the quality of information provided by ChatGPT is critical, and potential misunderstandings and problems can be traced back to system design and user unpreparedness. The original DM model (Chu, 2023), joint application of different models (Marjanovic et al., 2024; Thongsri et al., 2025), and limited scope (Duong et al., 2024) models can be found among the related research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Framework Model and Hypothesis Development

The research framework model (Figure 1), which was designed to investigate the research question of whether ChatGPT contributes to the success of higher education studies, is based on the DM model. The latent variable constructs of the DM model were kept, but the path structure needed some modifications. The original model includes bidirectional paths, which are not permitted under the rules of PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2022). Between use and satisfaction, the research model emphasizes that experience gained through use will have an impact on satisfaction with the system. Moreover, intention to use and actual use are not separated, as objective data collection about use was not feasible. A study in this field (Chu, 2023) omitted the construct of use or intention; however, for the purposes of this article, this approach was not suitable.

Figure 1.

Research framework model.

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS (Pallant, 2020) and SmartPLS 4 (Ringle & Becker, 2024) software. According to the procedure and threshold values of the PLS-SEM model, the guidelines of Hair et al. (2022) were followed. The analysis employed the path weighting scheme, using standardized results and default initial weights. The bootstrapping procedure was performed with the bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) method with 5000 subsamples. The significance level in the study was 0.050.

Research hypotheses were formulated for the paths in the model as follows:

H1:

Information quality (IQ) provided by ChatGPT has a positive impact on system use (USE).

H2:

Information quality (IQ) provided by ChatGPT has a positive impact on user satisfaction (SAT).

H3:

System quality (SQ) of ChatGPT has a positive impact on system use (USE).

H4:

System quality (SQ) of ChatGPT has a positive impact on user satisfaction (SAT).

H5:

Service quality (SeQ) of ChatGPT has a positive impact on system use (USE).

H6:

Service quality (SeQ) of ChatGPT has a positive impact on user satisfaction (SAT).

H7:

Use (USE) of ChatGPT positively impacts user satisfaction (SAT).

H8:

Use (USE) of ChatGPT positively impacts the net benefits (NET).

H9:

User satisfaction (SAT) positively impacts the net benefits (NET).

The survey items were adopted from former studies in the field (Table 1), including behavior models where applicable, and marked the main sources of formulating the statements. The tables and figures in Section 4 indicate the items and constructs by the abbreviations noted in the table.

Table 1.

Survey items with coding.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection was conducted in 2024 among higher education students from Romanian (Sapientia University) and Hungarian (University of Miskolc) institutions, using a convenience sampling method. A voluntary online survey was designed to collect information about students’ attitudes and behaviors related to GenAI use and their opinions about ChatGPT, including items related to the framework model presented in this paper. The respondents were asked to assess the statements with a 7-point scale.

The survey was distributed by a central message from the offices managing student information systems. A total of 618 responses were collected. Since academic misconduct can be considered in filling out surveys, which compromises the discriminant validity of the dataset, it was filtered based on the standard deviation of the responses, and suspicious respondents were excluded.

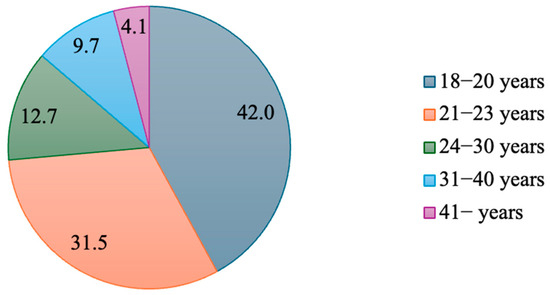

According to the inverse square root method (Hair et al., 2022, p. 26), the minimum sample size is 155 at 5% significance level and pmin = 0.2 value of the path coefficient with the minimum magnitude expected to be significant. Based on this guidance, the sample size (n = 466 valid responses) was preliminarily deemed to be adequate. The model run confirmed this assumption (pmin = 0.151, p = 0.014, related nmin = 272). The path coefficient between SeQ and SAT was lower but not significant (pmin = 0.091, p = 0.053). 190 females and 276 males were included. The mean age of the respondents was 23.63 years (standard deviation = 6.911). As expected, younger respondents are in the majority (Figure 2), but the research sample covers a broader target audience.

Figure 2.

Age distribution of the respondents.

4. Results

4.1. Structural Model Validation

The descriptive statistics for the survey items and the contribution to the model are summarized in Table 2. The outer loadings and significance levels confirm that items (loading < 0.708) are not significant, and the Variance Inflation Factor measures (VIF < 3 for each item) do not indicate any multicollinearity issues in the model.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of survey items, outer loadings, and VIF (based on SmartPLS output).

The reliability of the latent variable constructs is acceptable (Table 3). Cronbach’s alpha value of SQ is below the threshold value of 0.700, but the AVE is greater than 0.500. The authors attempted to include additional items related to SQ, as it can improve Cronbach’s alpha; however, any such efforts had an unfavorable effect on AVE and model fit indices as well.

Table 3.

Reliability statistics (based on SmartPLS output).

The discriminant validity of the model is assured based on the Fornell-Larcker criteria (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), the square roots of the AVE exceed the correlation values with other constructs for each latent variable (Table 4), ensuring convergent validity. Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) analysis (Henseler et al., 2015) also confirms the model, as the values do not exceed the threshold value of 0.900 (Table 5).

Table 4.

Fornell-Larcker criteria (based on SmartPLS output).

Table 5.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) analysis (based on SmartPLS output).

The most important fit indicator (Henseler et al., 2015), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = 0.073), suggests an acceptable model fit, as it is lower than the threshold value of 0.08. Other fit indices for the saturated model, based on the SmartPLS output, are d_ULS = 0.721, d_G = 0.356, and Chi-square = 1016.489. NFI = 0.727 does not exceed the threshold value of 0.900. There is an acceptable model fit for the pilot study; further data collection can improve fit indices.

4.2. Path Coefficients and Structural Model Assessment

The information quality (IQ), system quality (SQ), and service quality (SeQ) constructs explain 32.1% of the variance (R2) of use (USE) and 56.1% of the variance in satisfaction (SAT). The variance explained for the benefits (NET) is 6.1.9%. The results can be considered to have moderate explanatory power, but in the case of NET, the value is close to substantial (R2 > 67%). Figure 3 shows the model run results, including the outer loading with significance levels for the measurement model, as well as the path coefficients with significance levels for the structural model.

Figure 3.

Path analysis results (SmartPLS output).

All factor loadings in the model are significant (p < 0.050), and the path coefficients are acceptable, except for the SeQ → SAT relation (p = 0.053).

According to effect size (f2) (Cohen, 2013), a large (f2 ≥ 0.35) effect was not found. The most considerable effect was measured, close to the threshold value, between USE → NET (0.345). A further medium effect size was found (0.35 > f2 ≥ 0.15) between SAT → NET (0.251) and between USE → SAT (0.216). Low effect size (0.15 > f2 ≥ 0.02) was found between IQ → SAT (0.120), IQ → USE (0.037), SeQ → USE (0.053), SQ → SAT (0.027), SQ → USE (0.048). The effect size between SeQ and SAT (f2 = 0.013) is not considerable. Path coefficients and the significance test results are presented in Table 6 for hypothesis testing, and Table 7 shows the total and indirect effects.

Table 6.

Path coefficients and effect size for hypothesis testing (based on SmartPLS output).

Table 7.

Total effects and indirect effects (based on SmartPLS output).

The path direction between USE and SAT constructs was a research decision to investigate whether the experience gained from using ChatGPT contributes to higher enjoyment. The DM model (DeLone & McLean, 2003) assumed a mutual relationship between them. To check the SAT → USE direction, the trial model was created for testing the effect. Not remarkably affecting other indicators or outputs of the model, the result shows a significant (p = 0.000) path coefficient (0.476) that is higher than in the USE → SAT direction (0.374).

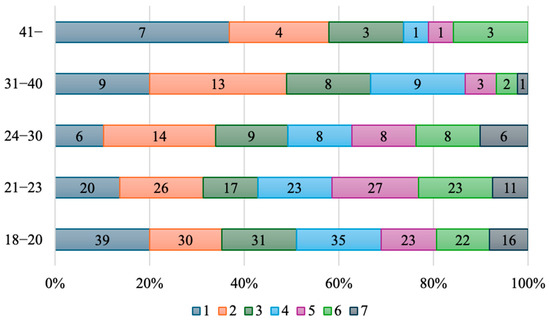

4.3. Frequency of ChatGPT Use by Age Categories

The frequency of ChatGPT use (USE1) was relatively low, with a high standard deviation. Figure 4 presents the distribution of responses (higher values on the seven-point scale indicate more frequent use) by age category. Younger respondents are more frequent users, but a mixed picture is found among them. In the period since data collection, a probable increase in frequency of use can be assumed according to ChatGPT based on the usage statistics available on the Internet (see, e.g., https://www.allaboutai.com/resources/how-many-people-use-chatgpt-daily (accessed on 22 August 2025)), and numerous GenAI services have been launched (Clark et al., 2025).

Figure 4.

Distribution of the responses to “I frequently ask ChatGPT” (USE1) item by age categories.

4.4. Perceived Benefits of Using ChatGPT by Age Categories

In relation to the research question of the study, the net benefits (NET) construct was limited to the benefits and usefulness of ChatGPT for the students’ higher education studies. The results by age (Figure 5) suggest a similar opinion among students about the beneficial nature of ChatGPT, except for the respondents aged between 21 and 23 years (who are presumably completing master-level studies), with a higher confidence in ChatGPT.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the responses to “ChatGPT is beneficiary for my studies at all” (NET2) item by age categories.

5. Discussion

5.1. Evaluation of the Findings

The statistical analysis confirmed the applicability of the DM model for assessing ChatGPT use. Among the influencing factors, information quality (IQ) has the strongest effect on intermediate constructs, primarily affecting satisfaction (SAT). That construct was strongly recommended by DeLone and Mclane (DeLone & McLean, 2003) as a critical dimension, which is confirmed by this study.

System quality (SQ) reflects the highest level of user satisfaction, as indicated by the mean values of the survey items (Table 1). This dimension primarily influences actual use, with a path coefficient of 0.245.

Service quality (SeQ) is the most challenging factor to understand since the service provided by ChatGPT itself is about that. The technical use of ChatGPT is not at all overcomplicated for one who has ever used search software. The weak results of the analysis can be explained by the fact that such a service is not required for students, or that they do not know what to expect. That should not be confused with the reliability of the responses.

Information quality was found to be the most important predictor of enjoying the usefulness of ChatGPT through the satisfaction of the students. The experience with the results of the system improves user satisfaction. At the same time, the indirect impact suggests that there are other influencing factors behind it. According to the information system view, system quality offers a limited contribution to the understanding of such factors, while service quality was found to be insignificant. The results provide insight into the motivations for using ChatGPT, highlighting the significant relationships between use, satisfaction, and benefits. However, they also point out the need for further research.

The personal judgment on the validity of information provided by ChatGPT may be very limited (Adel & Alani, 2025; Cong-Lem et al., 2024). At the same time, service quality is not a significant contributor to satisfaction or use, which can be explained by the uniform use of the search engine, which is an illusion. The limited knowledge also means that people may not know how to ask questions to ChatGPT (Son et al., 2025; Torkestani et al., 2025); the way of thinking in processing the questions still differs from that of humans.

The results align with the findings of (Salloum et al., 2024b) about how information quality and system quality primarily determine ChatGPT use, in their study focusing on ChatGPT-integrated learning platforms. Beyond information and system quality, the effect of service quality on satisfaction and benefits was confirmed by Chu (2023). The present study did not find a significant effect of service quality on satisfaction. H.-J. Chen et al. (2024) investigated the impact of the quality factors on satisfaction and confirmed the effect of information and service quality. They found that satisfaction predicts continuous intention to use ChatGPT, which is consistent with the finding in this paper about the significant effect of satisfaction on net benefits.

Few studies deal with the use of ChatGPT based on the DM model for any purpose. Chu (2023) examined the topic in business environment, concluding that service quality is the most important explanatory factor of satisfaction (path coefficient = 0.451, p = 0.000), and both system quality (path coefficient = 0.254, p = 0.000) and information quality (path coefficient = 0.254, p = 0.000) had a significant effect on satisfaction with high variance explained (R2 = 65.4%) similarly to our study (R2 = 56.1%). The role of service quality was found to be contradictory among higher education students, which can be explained by the fact that universities tended to prohibit and restrict the use of ChatGPT for educational purposes during the survey period.

Duong et al. (2024) used a limited model including information quality, service quality, and satisfaction with polynomial regression analysis. A direct comparison of the results is not feasible, but similarly to our results, their model reported a significant coefficient in the case of information quality (ß = 0.228, p < 0.001) and service quality (ß = 0.056, p = 0.472), but a low explanatory power (adjusted R2 = 0.187).

Thongsri et al. (2025) used a joint model to explore the influencing factors of students’ behavioral intention to use ChatGPT, including the DM model factors. Their findings are in line with the present study, as they found information quality (path coefficient = 0.055, p < 0.001) and system quality (path coefficient = 0.567, p < 0.001) to be significant influencing factors of the intention. Their model had a high explanatory power (R2 = 65.0%); however, it covers the impact of personal factors as well.

Marjanovic et al. (2024) emphasized the impact of system quality on use (path coefficient = 0.45, p < 0.001, R2 = 21%) and satisfaction (path coefficient = 0.70, p < 0.001, R2 = 53%), in line with the present results. Similarly, satisfaction is the main predictor of net benefits (path coefficient = 0.81, p < 0.001, R2 = 63%).

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

According to the hypothesis formulated for the DM model paths, most of them can be accepted (Table 6), and the following statements can be formulated:

- The information quality provided by ChatGPT has a significant positive effect on system use; however, the effect size is small and not statistically significant (H1). Information quality primarily affects user satisfaction with ChatGPT (H2).

- ChatGPT system quality has a significant positive effect on use (H3) and satisfaction (H4), among which the effect size on use is significant.

- Service quality related to ChatGPT affects the use of the software (H5), but satisfaction is not affected significantly (H6).

- The use of ChatGPT has a significant positive impact on user satisfaction (H7), and the reverse direction is also experienced.

- ChatGPT’s beneficial nature is explained by use (H8) and user satisfaction (H9).

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Contributions

The findings of the study confirmed previous results regarding the broad and high-level acceptance of ChatGPT among higher education students and the applicability of the DM model for the analysis of this system. Based on the analysis of 466 valid responses from higher education students, information quality and system quality have a significant impact on use and satisfaction, while service quality has a marginal impact, suggesting a different picture compared to corporate applications. The results revealed that higher education students like using ChatGPT, and user satisfaction is the strongest influencing factor of the net benefits. A practical implication derived from the negligible effect of service quality is that targeted education and training are required.

Overall, the research contributes to a deeper understanding of the application of Gen AI in higher education and provides a basis for developing a comprehensive model for international comparison.

The framework model and the results are considered a pilot study in the field. Given the limited number of studies focusing on the information system view of ChatGPT use, this approach can serve as a bridge for future model building to manage competing results with personal influencing factors.

6.2. Further Research

Due to the similar trends in the results despite the different framework models used, the additional influencing factors involved, and the wide variety of survey items, the theoretical implication of the study is the need for a common framework model. The DM model can serve as an initial framework retaining information quality, and the approach to separate (intention) use, satisfaction, and benefits. UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al., 2012) and TAM2/TAM3 (Venkatesh & Bala, 2008) models are considerable since they include a large number of explanatory factors. Habit, hedonistic motivations, and literacy may be relevant constructs.

Moreover, while incorporating personal and social influences is certainly important, attempts to measure them in previous studies have yielded inconsistent or scattered results. Assuming that the latent variable construct aims to explore similar phenomena, the lesson can be drawn that users’ expectations regarding the service of ChatGPT are confirmed to predict the intention to use it, while the impact of the efforts needed may depend on other factors. Attitudes (Zhao et al., 2024), satisfaction (Tang et al., 2025), or motivation (Salloum et al., 2024a) can play a relevant role in further investigations.

Methodologically, the bi-directional relationship between use and satisfaction could not be captured in a single PLS-SEM model; the trial model suggested a mutual relationship between them. Developing a CB-SEM model with enhanced data collection could further investigate the issue.

6.3. Need for Policy Making

An important lesson from the study is the urgency of policymaking. That cannot be just an administrative task to be checked off. The rapid spread of ChatGPT and other GenAI models, along with the significant uncertainty surrounding their use, raises the need for policy development. The role of higher education institutions is particularly important in the ethical and effective use of GenAI, as they prepare students for their future work and support scientific research. The pace of the development of technology exceeds the response time of policymakers; there is a pressing need for balanced regulation (Dempere et al., 2023). According to the review by Batool (Batool et al., 2025), the objective of the related regulation can be the data and/or the system, the responsibility for governing AI issues can be organizational, national, and international, and the way of governance can be ethical (in the forms of principles, policies, and guidelines), frameworks, models, and tools. Since experience with GenAI systems lags behind other issues in terms of time, cautious approaches and attempts with different approaches are understandable. The results, based on the information system view of ChatGPT, suggest that data-oriented policies may be expedient for higher education institutions because information quality significantly affects student satisfaction. The objective of the regulations must focus on the tasks to be performed (learning, research, writing), while broader policies describe the options for action. The rapid development of systems makes system-oriented regulations unnecessary, and this is also confirmed by the study results. Considering GenAI as a tool for performing better, supplementing existing regulations for such tasks is purposeful to avoid conflicting provisions. The goal of co-participation of GenAI in education (Nasr et al., 2025) may be achievable and acceptable that Quality management experts can effectively support this process. In addition, a highlight of the ethical principles is necessary to help perform the related educational, training, and communication activities. Regarding the responsibility of principles and guidelines, it must extend beyond the walls of universities, as the quality of their output is valued by external partners. Local application of PLS-SEM analysis supports the clarification of details.

6.4. Limitations

Although the authors strove to conduct a thorough and comprehensive analysis at both theoretical and empirical investigations, the interpretation of the results has some limitations. Although a large sample was available, it was limited to higher education students, and the representativeness is not assured by any aspect. The source of the data is a self-administered online questionnaire, so issues of misunderstanding and misconduct can be expected, despite screening the database. The PLS-SEM method was employed; future research must aim for a CB-SEM analysis as well as the fsQCA method after more extensive data collection. Based on the limited experience with using the DM model for GenAI systems, the results are considerable, making this a pilot study for mode development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B., E.L. and S.M.; methodology, L.B. and E.L.; software, L.B.; validation, L.B. and S.M.; formal analysis, L.B. and E.L.; investigation, L.B. and S.M.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, E.L. and S.M.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, E.L.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The creation of this scientific communication was supported by the University of Miskolc with funding granted to the author László Berényi within the framework of the institution’s Scientific Excellence Support Program (Project identifier: ME-TKTP-2025-023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Scientific Committee of the University of Miskolc (protocol code: TNI/1836/2025; date of approval: 23 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| DM model | DeLone and McLean Information Success model |

| ChatGPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling |

| fsQCA | Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

References

- Abdul Wahi, N. S., & Berényi, L. (2023). Validating UTAUT model for E-government adoption among employees: A pilot study. Gradus, 10(2), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A., & Alani, N. (2025). Can generative AI reliably synthesise literature? Exploring hallucination issues in ChatGPT. AI & SOCIETY, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abdullatif, A. M., & Alsubaie, M. A. (2024). ChatGPT in learning: Assessing students’ use intentions through the lens of perceived value and the influence of AI literacy. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaisal, R., Hatem, M., Salloum, A., Al Saidat, M. R., & Salloum, S. A. (2024). Forecasting the acceptance of ChatGPT as educational platforms: An integrated SEM-ANN methodology. In A. Al-Marzouqi, S. A. Salloum, M. Al-Saidat, A. Aburayya, & B. Gupta (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in education: The power and dangers of ChatGPT in the classroom (Vol. 144, pp. 331–348). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maroof, R. S., Alhumaid, K., Alshaafi, A., Akour, I., Bettayeb, A., Alfaisal, R., & Salloum, S. A. (2024). A comparative analysis of ChatGPT and Google in educational settings: Understanding the influence of mediators on learning platform adoption. In A. Al-Marzouqi, S. A. Salloum, M. Al-Saidat, A. Aburayya, & B. Gupta (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in education: The power and dangers of ChatGPT in the classroom (Vol. 144, pp. 365–386). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qaysi, N., Al-Emran, M., Al-Sharafi, M. A., Iranmanesh, M., Ahmad, A., & Mahmoud, M. A. (2025). Determinants of ChatGPT use and its impact on learning performance: An integrated model of BRT and TPB. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41(9), 5462–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S. H., & Alshammari, M. H. (2024). Factors affecting the adoption and use of ChatGPT in higher education. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 20(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshurideh, M., Jdaitawi, A., Sukkari, L., Al-Gasaymeh, A., Alzoubi, H. M., Damra, Y., Yasin, S., Kurdi, B. A., & Alshurideh, H. (2024). Factors affecting ChatGPT use in education employing TAM: A Jordanian universities’ perspective. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 8(3), 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, N., Bervell, B., Mireku, D. O., & Andoh, R. P. K. (2025). Artificial intelligence in higher education: Modelling students’ motivation for continuous use of ChatGPT based on a modified self-determination theory. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubi, K. (2024). Adopting ChatGPT: Pioneering a new era in learning platforms. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 8(2), 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, A., Zowghi, D., & Bano, M. (2025). AI governance: A systematic literature review. AI and Ethics, 5(3), 3265–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettayeb, A. M., Abu Talib, M., Sobhe Altayasinah, A. Z., & Dakalbab, F. (2024). Exploring the impact of ChatGPT: Conversational AI in education. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1379796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubker, O. (2024). From chatting to self-educating: Can AI tools boost student learning outcomes? Expert Systems with Applications, 238, 121820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhathoki, T., Zirar, A., Njoya, E. T., & Timsina, A. (2024). ChatGPT adoption and anxiety: A cross-country analysis utilising the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). Studies in Higher Education, 49(5), 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruk, O. (2023, October 3–6). Academic writing with GPT-3.5 (ChatGPT): Reflections on practices, efficacy and transparency. 26th International Academic Mindtrek Conference (pp. 144–153), Tampere, Finland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q., Lin, Y., & Yu, Z. (2023). Factors influencing learner attitudes towards ChatGPT-Assisted language learning in higher education. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 40(22), 7112–7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantamessa, M., Montagna, F., Altavilla, S., & Casagrande-Seretti, A. (2020). Data-driven design: The new challenges of digitalization on product design and development. Design Science, 6, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Aziz, A. A., & Arshard, W. N. R. M. (2023). University students’ perspectives on artificial intelligence: A survey of attitudes and awareness among interior architecture students. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changalima, I. A., Amani, D., & Ismail, I. J. (2024). Social influence and information quality on generative AI use among business students. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(3), 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Zhu, X., & Díaz Del Castillo H., F. (2023). Integrating generative AI in knowledge building. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J., Chang, S.-T., Chou, P.-Y., Tsai, Y.-S., Chu, C., Hsieh, F.-C., & Tseng, G. (2024). Exploring users’ continuous use intention of ChatGPT based on the IS success model and technology readiness. International Journal of Management Studies and Social Science Research, 6(1), 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.-N. (2023). Assessing the benefits of ChatGPT for business: An empirical study on organizational performance. IEEE Access, 11, 76427–76436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J., Barton, B., Albarqouni, L., Byambasuren, O., Jowsey, T., Keogh, J., Liang, T., Moro, C., O’Neill, H., & Jones, M. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence use in evidence synthesis: A systematic review. Research Synthesis Methods, 16(4), 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong-Lem, N., Soyoof, A., & Tsering, D. (2024). A systematic review of the limitations and associated opportunities of ChatGPT. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41(7), 3851–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempere, J., Modugu, K., Hesham, A., & Ramasamy, L. K. (2023). The impact of ChatGPT on higher education. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1206936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C. D. (2024). Modeling the determinants of HEI students’ continuance intention to Use ChatGPT for learning: A stimulus–organism–response approach. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 17(2), 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C. D., Nguyen, T. H., Ngo, T. V. N., Dao, V. T., Do, N. D., & Pham, T. V. (2024). Exploring higher education students’ continuance usage intention of ChatGPT: Amalgamation of the information system success model and the stimulus-organism-response paradigm. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 41(5), 556–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraon, M., Rönkkö, K., Milrad, M., & Tsui, E. (2025). International perspectives on artificial intelligence in higher education: An explorative study of students’ intention to use ChatGPT across the Nordic Countries and the USA. Education and Information Technologies, 30(13), 17835–17880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnia, M., Banihashem, S. K., Noroozi, O., & Wals, A. (2024). A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: Implications for educational practice and research. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(3), 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado, F., Calderón, D., González, I., & Calderón, A. (2024). Review of Industry 4.0 from the perspective of automation and supervision systems: Definitions, architectures and recent trends. Electronics, 13(4), 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B., Senali, M. G., Iranmanesh, M., Khanfar, A., Ghobakhloo, M., Annamalai, N., & Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. (2024). Determinants of intention to use ChatGPT for educational purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 40(17), 4501–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F., & Vázquez-Ingelmo, A. (2023). What do we mean by GenAI? A systematic mapping of the evolution, trends, and techniques involved in generative AI. International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 8(4), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granić, A. (2025). Emerging drivers of adoption of generative AI technology in education: A review. Applied Sciences, 15, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A., Muhaimin, M., Danibao, B. K., Wibowo, Y. G., Wahyuni, S., & Octavia, A. (2023). ChatGPT in higher education learning: Acceptance and use. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A Primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanein, A. M., & Sobaih, A. E. E. (2023). Drivers and consequences of ChatGPT use in higher education: Key stakeholder perspectives. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(11), 2599–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanein, A. M., Sobaih, A. E. E., & Elshaer, I. A. (2024). Examining Google Gemini’s acceptance and usage in higher education. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 7(2), 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoi, S., Yu, Y., & Ye, L. (2023, December 22–24). How perceived organizational support influences university students intention to use AI language models in course learning: An exploratory study based on the technology acceptance model. 2023 International Conference on Information Education and Artificial Intelligence (pp. 781–786), Xiamen, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-M., Liu, F.-C., Chu, C.-M., & Chang, Y.-T. (2023). Health care trainees’ and professionals’ perceptions of ChatGPT in improving medical knowledge training: Rapid survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e49385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, S., Jin, S., & Jiang, S. (2024). The limitations and ethical considerations of ChatGPT. Data Intelligence, 6(1), 201–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H., Gordon, M., Hodgkinson, C., Foreman, R., & Wagad, S. (2025). ChatGPT’s impact across sectors: A systematic review of key themes and challenges. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 9(3), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaias, P., & Issa, T. (2015). High level models and methodologies for information systems. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M. (2024). AI literacy and intention to use text-based GenAI for learning: The case of business students in Korea. Informatics, 11(3), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H. (2023). Decoding the ChatGPT mystery: A comprehensive exploration of factors driving AI language model adoption. Information Development, 41(3), 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Esposito, A. G. (2025). ChatGPT or human mentors? Student perceptions of technology acceptance and use and the future of mentorship in higher education. Education Sciences, 15(6), 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., & Ma, C. (2024). Measuring EFL learners’ use of ChatGPT in informal digital learning of English based on the technology acceptance model. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 18(2), 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K. (2023). What is the impact of ChatGPT on education? A rapid review of the literature. Education Sciences, 13(4), 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K., Hew, K. F., & Jong, M. S. (2024). The influence of ChatGPT on student engagement: A systematic review and future research agenda. Computers & Education, 219, 105100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G. (2024). Factors influencing students’ intention to adopt and use ChatGPT in higher education: A study in the Vietnamese context. Education and Information Technologies, 29(10), 12167–12195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic, U., Mester, G., & Milic Marjanovic, B. (2024). Assessing the success of artificial intelligence tools: An evaluation of ChatGPT using the information system success model. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems, 22(3), 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namatovu, A., & Kyambade, M. (2025). Leveraging AI in academia: University students’ adoption of ChatGPT for writing coursework (take home) assignments through the lens of UTAUT2. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2485522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, N. R., Tu, C.-H., Werner, J., Bauer, T., Yen, C.-J., & Sujo-Montes, L. (2025). Exploring the impact of generative AI ChatGPT on critical thinking in higher education: Passive ai-directed use or human–ai supported collaboration? Education Sciences, 15(9), 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B. S., & Walton, N. (2024). History and rise of artificial intelligence. In Political economy of artificial intelligence (pp. 1–17). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T. T., Khuong An, G., Thy Nguyen, P., & Tu Tran, T. (2024). Unlocking educational potential: Exploring students’ satisfaction and sustainable engagement with ChatGPT using the ECM model. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 23, 021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niloy, A. C., Bari, M. A., Sultana, J., Chowdhury, R., Raisa, F. M., Islam, A., Mahmud, S., Jahan, I., Sarkar, M., Akter, S., Nishat, N., Afroz, M., Sen, A., Islam, T., Tareq, M. H., & Hossen, M. A. (2024). Why do students use ChatGPT? Answering through a triangulation approach. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS (7th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannidis, S. (2022). TheoryHub book. Available online: https://www.theoryhub.org/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Pushparaj, N., Sivakumar, V. J., Natarajan, M., & Bhuvaneskumar, A. (2023). Two decades of DeLone and Mclean IS success model: A scientometrics analysis. Quality & Quantity, 57(3), 2469–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K., & Wu, X. (2024). ChatGPT as a CALL tool in language education: A Study of hedonic motivation adoption models in English learning Environments. Education and Information Technologies, 29(15), 19471–19503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., & Becker, J.-M. (2024). SmartPLS 4 [Computer software]. SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Sabraz Nawaz, S., Fathima Sanjeetha, M. B., Al Murshidi, G., Mohamed Riyath, M. I., Mat Yamin, F. B., & Mohamed, R. (2024). Acceptance of ChatGPT by undergraduates in Sri Lanka: A hybrid approach of SEM-ANN. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 21(4), 546–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salifu, I., Arthur, F., Arkorful, V., Abam Nortey, S., & Solomon Osei-Yaw, R. (2024). Economics students’ behavioural intention and usage of ChatGPT in higher education: A hybrid structural equation modelling-artificial neural network approach. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2300177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S. A., Aljanada, R. A., Alfaisal, A. M., Al Saidat, M. R., & Alfaisal, R. (2024a). Exploring the acceptance of ChatGPT for translation: An extended TAM model approach. In A. Al-Marzouqi, S. A. Salloum, M. Al-Saidat, A. Aburayya, & B. Gupta (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in education: The power and dangers of ChatGPT in the classroom (Vol. 144, pp. 527–542). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S. A., Almarzouqi, A., Aburayya, A., Shwedeh, F., Fatin, B., Al Ghurabli, Z., Al Dabbagh, T., & Alfaisal, R. (2024b). Redefining educational terrain: The integration journey of ChatGPT. In A. Al-Marzouqi, S. A. Salloum, M. Al-Saidat, A. Aburayya, & B. Gupta (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in education: The power and dangers of ChatGPT in the classroom (Vol. 144, pp. 157–169). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S. A., Hatem, M., Salloum, A., & Alfaisal, R. (2024c). Envisioning ChatGPT’s integration as educational platforms: A hybrid SEM-ML method for adoption prediction. In A. Al-Marzouqi, S. A. Salloum, M. Al-Saidat, A. Aburayya, & B. Gupta (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in education: The power and dangers of ChatGPT in the classroom (Vol. 144, pp. 315–330). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, P. B., Staples, S., Patnayakuni, R., & Bowtell, M. (1999). Dimensions of information systems success. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 2(20), 2–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengar, S. S., Hasan, A. B., Kumar, S., & Carroll, F. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence: A systematic review and applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 84(21), 23661–23700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M. F., Xu, S., & Javed, I. (2024). ChatGPT awareness, acceptance, and adoption in higher education: The role of trust as a cornerstone. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M., Won, Y.-J., & Lee, S. (2025). Optimizing large language models: A deep dive into effective prompt engineering techniques. Applied Sciences, 15(3), 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stair, R. M., & Reynolds, G. W. (2018). Fundamentals of information systems (9th ed). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecki, A. (2024). To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(9), 5142–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supianto, Widyaningrum, R., Wulandari, F., Zainudin, M., Athiyallah, A., & Rizqa, M. (2024). Exploring the factors affecting ChatGPT acceptance among university students. Multidisciplinary Science Journal, 6(12), 2024273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya Bahadur, G. C., Bhandari, P., Gurung, S. K., Srivastava, E., Ojha, D., & Dhungana, B. R. (2024). Examining the role of social influence, learning value and habit on students’ intention to use ChatGPT: The moderating effect of information accuracy in the UTAUT2 model. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2403287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Yuan, Z., & Qu, S. (2025). Factors influencing university students’ behavioural intention to use generative artificial intelligence for educational purposes based on a revised UTAUT2 model. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 41(1), e13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsri, N., Tripak, O., & Bao, Y. (2025). Do learners exhibit a willingness to use ChatGPT? An advanced two-stage SEM-neural network approach for forecasting factors influencing ChatGPT adoption. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 22(2), 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, C. K., Bhat, M. A., Khan, S. T., Subramaniam, R., & Khan, M. A. I. (2023). What drives students toward ChatGPT? An investigation of the factors influencing adoption and usage of ChatGPT. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 21(3), 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkestani, M. S., Alameer, A., Palaiahnakote, S., & Manosuri, T. (2025). Inclusive prompt engineering for large language models: A modular framework for ethical, structured, and adaptive AI. Artificial Intelligence Review, 58(11), 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustundag, A., & Cevikcan, E. (2018). Industry 4.0: Managing the digital transformation. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Bala, H. (2008). Technology acceptance Model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sciences, 39(2), 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S., Montsch, C., Delpechithrage, T., & Nguyen, B. A. P. (2026). From regulation to implementation: Understanding the impact of the EU AI Act on public sector institutions in Germany. In S. Hofmann, L. Danneels, R. Dobbe, A.-S. Novak, P. Parycek, G. Schwabe, V. Spitzer, & J. Ubacht (Eds.), Electronic participation (Vol. 15978, pp. 87–101). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T., Shi, H., Shi, Y., & You, J. (2024). From data to data asset: Conceptual evolution and strategic imperatives in the digital economy era. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 18(1), 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., & Thien, L. M. (2025). Unleashing the power of perceived enjoyment: Exploring Chinese undergraduate EFL learners’ intention to use ChatGPT for English learning. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 17(2), 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaied, A. N. (2012). An integrated success model for evaluating information system in public sectors. Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences, 3(6), 814–825. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., Chen, Y., Chen, H., & Chong, D. (2024). Industry 4.0 and its implementation: A review. Information Systems Frontiers, 26(5), 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Li, Y., Xiao, Y., Chang, H., & Liu, B. (2024). Factors influencing the acceptance of ChatGPT in high education: An integrated model with PLS-SEM and fsQCA approach. Sage Open, 14(4), 21582440241289835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Müller, H., Holzinger, A., & Chen, F. (2024). Ethical ChatGPT: Concerns, challenges, and commandments. Electronics, 13(17), 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).