Abstract

Decimals are of great significance in the primary mathematics curriculum due to their application and use in everyday life. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of certain dynamic digital representations in developing students’ knowledge of decimal fractions. Task-based interviews were used with six Year 4 (9–10 years old) students that incorporated four different dynamic digital representations of decimals. Data collected via video–audio recordings were used to detect shifts in students’ attention while using the digital representations. Attention shifts were analysed using microgenetic methods to determine conceptual changes over time. Findings uncovered specific features of the digital representations that generated productive cognitive confusion that prompted changes in students’ understanding of decimal fractions. The unique affordances of each digital tool offered students opportunities to dynamically explore decimal concepts, and the digital tools could be used to enrich the teaching of decimals within the primary mathematics classroom.

1. Introduction

Children have difficulty in understanding the abstract nature of decimals, and a plethora of misconceptions arise from incomplete understandings (Steinle & Stacey, 2004). Such complexities arise as students are exposed to rational numbers in numerous symbolic representations, including ratios, fractions, decimals, and percentages, without deep understanding and knowledge of how to use each notation correctly (Bobis, 2011). Furthermore, decimal fractions present additional complications as part of the number-relationship needed to make sense of the numeral, the denominator, is not visible (Steinle & Stacey, 2004). Developing conceptual understanding of decimal density, place value and relative magnitude of decimal fractions is considered key for consolidating number sense, since these properties unify all numbers (Siegler et al., 2011) and rational number magnitude knowledge is related to future mathematics achievement (DeWolf et al., 2016). The current research sought to understand how the use of certain interactive digital tools influenced students’ understanding and conceptualisation of decimal fractions. This study involved mapping how their understanding evolved through shifts in attention, what challenges they encountered with the dynamic affordances, and what new insights they gained through their engagement with these digital representations. The new-found understanding of how students develop decimal sense through dynamic digital representations could translate into advice about effective pedagogy within the primary mathematics classroom. Two research questions communicate the aim of the study:

1. What conceptual changes occur when children attend to features of dynamic digital representations of decimal fractions?

2. How do shifts in attention mediate engagement with these representations?

In this section literature related to the areas of decimal fractions and mathematics representations is presented. The review outlines existing research into the role of conceptual understanding in the primary mathematics classroom and the importance of decimal fractions in the primary mathematics curriculum. In addition, a summary of the difficulties that students encounter when learning about decimal fractions, including misconceptions that often arise from incomplete understandings, is presented. The second part of the review discusses the role of representations in mathematics learning extending to the field of dynamic digital representations. A description of the affordances and constraints of dynamic representations is included.

1.1. Conceptual Understanding of Decimal Fractions

Decimal fractions stem from the base-ten numerical system. According to Martinie (2014), students encountering difficulties in comprehending place value with the base-ten system often struggle with decimal fraction computations. Additionally, learners may face challenges when failing to recognise decimal fractions as a distinct category of fractions with base-ten denominators (Martinie, 2014). Students need prior knowledge and experience with whole-numbers and common fractions to build conceptual understanding of decimal fractions as decimal notation is compounded in complexity by the merging of these two rational number systems. In the realm of mathematics education, conceptual understanding is defined as “an integrated and functional grasp of mathematical ideas” (National Research Council, 2001, p. 118). This understanding encompasses the familiarity with presenting various scenarios in diverse ways, discern connections between those representations, and employ each representation for distinct purposes (Caldwell, 2020). The development of students’ conceptual understanding parallels their progress in mathematics learning.

The growth of students’ conceptual understanding is synonymous with mathematics learning. Conceptual understanding develops over time as students organise their knowledge into a coherent, integrated mental structure (Caldwell, 2020). The learning of mathematics occurs through shifts of students’ attention which “constitutes changes in understanding” (Mason, 2002, p. 25). A student’s understanding evolves not in a linear progression, but through the accumulation of more refined ‘microqualities’ of attention, leading to a deeper grasp of a mathematical concept (Mason, 2008). Microqualities of attention refer to the specific and rapid ways in which students direct and regulate their focus when engaging with mathematical concepts. These subtle shifts in attention can significantly impact how learners develop a deep conceptual understanding of decimal fractions. The development of more a sophisticated and mature grasp of the concept of decimal numbers occurs through the hurried re-experience of shifts of attention whenever a learner is invited to respond to a probe about decimals (Mason, 2008). Pirie and Kieren’s (1991) theoretical work on acquiring mathematical understanding proposes a similar learning trajectory, highlighting that ‘folding back’ is crucial for the development of mathematical thinking. A growth in mathematical understanding is seen to emerge through the continual movement back and forth through levels of knowing, as students reflect on and reconstruct their current understandings (Pirie & Kieren, 1991). For example, a student grappling with flexible strategies for addition and subtraction of decimals may face a problem that is not immediately solvable. They will need to revisit earlier understandings of decimal concepts and use these to inform their new thinking at the higher learning level, leading to a deeper understanding of the concept. Clements and Sarama (2004) developed a cognitive model of students’ learning that described the processes involved in the construction of conceptual knowledge across several qualitatively distinct structural levels of increasing complexity. Importantly, these levels of structured understanding are not distinct classes of mathematical thinking that suddenly change, rather higher levels are elaborations and advancements of lower levels (Clements & Sarama, 2004).

Currently, there is insufficient research regarding the optimal learning process through which students develop a conceptual understanding of decimals (Tian & Siegler, 2018). Decimals are constrained equivalent fractions, in that the denominators are limited to tenths, hundredths, thousandths, and so forth. Place value of decimal fractions involves symmetry around the ones place value. The decimal system extends infinitely in both directions of magnitude, with the relationship between consecutive places directed by multiplication or division by ten. Decimal density refers to the continuity property of rational numbers, whereby between any two decimals there are an infinite number of other decimals (Widjaja et al., 2008). Decimal magnitude understanding refers to familiarity with estimating and reasoning about the size of a decimal (Resnick et al., 2019). One way in which students can demonstrate their knowledge of decimal magnitude is by determining the location of a decimal on a number line, rationalising about the size of a decimal compared to the benchmark fraction (e.g., ), and judging the validity of decimal and fraction equivalencies (Resnick et al., 2019).

Understanding decimal fractions conceptually rather than only procedurally is essential, as it lays the groundwork for employing appropriate strategies in mathematical tasks (Way, 2011). Without a robust conceptual grasp of decimals, students are prone to developing misconceptions related to the topic (Steinle & Stacey, 2004). Misconceptions often arise when students inappropriately apply rules to decimal fractions that result in the right answer for the wrong reason, reinforcing the fabricated rule (Hiebert & Wearne, 1985). Four common misconception categories that emerge from the literature include; longer-is-larger thinking, shorter-is-larger thinking, zero-makes-small thinking, and money rule (Moloney & Stacey, 1997; Steinle & Stacey, 2004; Martinie, 2014). Students must be equipped with effective learning tools to address cognitive confusions in their thinking about decimal fractions. Therefore, it is necessary to consider what instructional tools should be implemented in mathematics classrooms to aid students in cultivating accurate decimal fraction sense and preventing the emergence of common misconceptions.

1.2. Mathematics Representations

Representations are widely recognised as valuable tools in mathematics, offering experiential learning opportunities through both concrete and virtual manipulatives. Piaget (1970), Bruner (1986), and Skemp (1987) concur that the development of concepts progresses from physical objects to representational forms and then to abstract thought. According to Kennedy (1986), students’ capacity to form mental images and access abstract ideas is dependent on their experiences. By interacting with and manipulating physical objects, students can form stronger mental images and represent abstract concepts more comprehensively (Kennedy, 1986). This aligns with Pirie and Kieren’s (1994) early phases of mathematical understanding, where students construct mental images through engaging with tangible representations before progressing to more abstract reasoning. Studies have emphasised the significance of mathematical representations in fostering fractional thinking (Siemon et al., 2011). Students proficient in partitioning areas, sets, and line models, as well as naming fractions in various ways, are more likely to grasp the connection between fractions involving tenths and the base-10 number system (Siemon et al., 2011).

Dynamic representations have proven to be effective aids in student learning within mathematics due to their dynamic affordances. These representations enable students to actively engage with mathematical content by formulating conjectures and promptly testing them, thus allowing them to perceive concepts from various perspectives (Orrill & Polly, 2013). Specifically, learner-centred computer tools that promote interactive engagement with mathematics empower students to ‘see’ notions that would otherwise be ‘unseeable’ (Orrill & Polly, 2013). Digital technologies are regarded as “dynamic, manipulable, and interactive representational forms” that both facilitate and are influenced by mathematical thinking and expression (Hoyles & Noss, 2003, p. 326).

When designing learning activities, mathematics educators are frequently restricted to using symbolic representations that isolate a single mathematical concept. A holistic mathematics education that enhances mathematical thinking involves searching for meaning beyond symbol sense. Santos-Trigo (2006) suggests that the integration of technology in a mathematics classroom has the potential to develop a disposition, resources and problem-solving strategies associated with this extended way of thinking. Technology can generate a dynamic representation of a problem in which students can pose and pursue questions that might lead them to identify and examine connections and extensions of that problem (Santos-Trigo, 2006). In this process, it is argued that representing the problem dynamically might offer students the opportunity to be engaged in a line of thinking in which they constantly need to search for mathematical relationships and utilise the knowledge they possess to explore and support the pertinence and validity of those relationships (Roschelle et al., 2000). The integration of dynamic digital representations in mathematics education has emerged as a transformative approach to supporting student learning and conceptual understanding. These representations constitute a crucial component of cultural infrastructure, providing systematic methods for presenting mathematical thoughts, creating communicative records across contexts, and supporting mathematical reasoning and computation (Laborde & Laborde, 2014). This examination of dynamic digital representations reveals their benefits to mathematics learning through four key dimensions: epistemological considerations in design, cognitive transformations in student thinking, progressive learning through interaction modalities and pedagogical reimagining of mathematical tasks (Ruthven, 2022).

Integral to this research into dynamic representations is investigating the affordances and constraints of these digital learning tools. Recent research has explored the potential benefits of touchscreen digital tools, and this body of research suggests that apps for virtual manipulatives offer various advantages that may impact learning, which children utilise in diverse ways (Moyer-Packenham & Westenskow, 2016; Tucker & Moyer-Packenham, 2014; Tucker et al., 2016). The rapid advancement of technology in mathematics education presents new challenges for educators, as it involves “using new kinds of mathematical tasks and modifying the nature of mathematical activities in classroom based on a set of pedagogical principles” (Shahmohammadi, 2019, p. 1834). This critical perspective demonstrates the importance of closely examining how technology influences and enhances students’ learning and conceptual understanding of mathematics. Specifically, teachers must comprehend how different instructional tools can aid students in improving their understanding of mathematical concepts through various cognitive processes.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

The theoretical perspectives of constructivism, representations in mathematics and ‘shifts of attention’ yield a theoretical framework useful for investigating students’ interactions with dynamic digital representations of decimal fractions. In particular, a learning environment incorporating rich problem-solving tasks is suited to exploring students’ conceptual understanding of decimal fractions through noticing their shifts in attention during the process of task completion (Voutsina et al., 2019).

2.1. Constructivist Theory

The theoretical framework employed in this study is underpinned by the work of Piaget (1970), who was seminal in using task-based interviews to elucidate children’s thought processes regarding posed problems and advocated for the belief that “true understanding takes place when the student makes discoveries for themselves” (Assad, 2015, p. 17). Constructivism, a prominent theoretical perspective in mathematics research, has been extensively explored by several key scholars (Cobb et al., 1992; von Glasersfeld, 1995; Katic et al., 2009). A fundamental tenet of Piaget’s constructivist theory posits that students construct their understanding and knowledge through perceptions and experiences, which are in turn “mediated through previous knowledge” (Simon, 1995, p. 115). Consequently, this study acknowledged students’ pre-existing knowledge of decimal fractions and anticipates that individual students will interact with digital tools in varying ways. Constructivist mathematics teaching with digital tools emphasises the interplay between mathematical content knowledge, constructivist pedagogies, and technology to enhance conceptual understanding (Mishra & Koehler, 2006). This study positions digital tools to enhance constructivist mathematics learning by offering interactive, visual, and collaborative experiences.

2.2. Representation Theory

In the mathematics classroom, representations serve as tools to assist students in grasping abstract concepts that are fundamental to mathematical learning. Specifically, within the realm of mathematics, representation is defined as “the act of externalising an internal, mental abstraction” (Pape & Tchoshanov, 2001, p. 119). Hiebert and Carpenter (1992) make a distinction between internal and external representations, where internal knowledge representations are the cognitive structures of knowledge in a learner’s mind, and external representations often assume the forms of spoken language, pictures, written symbols, and manipulative models (Lesh et al., 1987). Mathematics educators have long perceived external representations as an effective means of making mathematical ideas understandable for students (Hiebert & Carpenter, 1992). G. A. Goldin (2000, 2003) maintains that external representations should play a fundamental role in empirical investigations of students’ reasoning and understanding of mathematical concepts, such as during task-based interviews. Enhancing students’ mathematical understanding and their ability to think representationally necessitates the flexible use of multiple representations, along with the interaction between external and internal representations (Pape & Tchoshanov, 2001). Effectively translating concepts across different representational modes plays a critical role in the acquisition of mathematical ideas, and engaging with multiple representations can facilitate this process (Lesh et al., 1987; Duval, 2006).

2.3. Shifts of Attention Theory

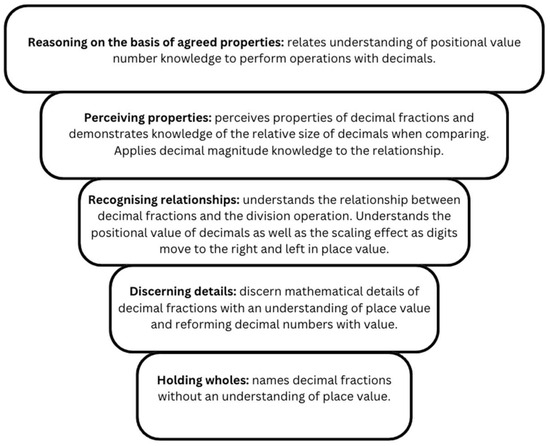

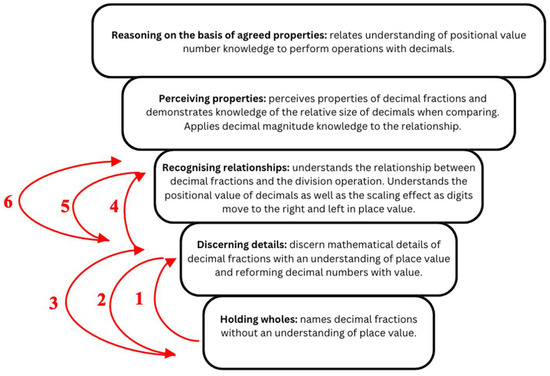

The theory of shifts of attention serves as a framework for researchers to comprehend students’ mathematical thinking, offering five observable ways of attending that indicate both the content and manner in which students learn in the mathematics classroom (Mason, 2008). Mason’s (2008) conceptualisation of attention serves to explain students’ mathematical learning processes. Throughout the development of mathematical thinking, various shifts of attention may occur, relating to the object or focus of attention (what the learner attends to) and the form or structure of attention (how the learner attends) (Mason, 2008). The structure of attention encompasses activities such as “holding wholes, discerning details, recognising relationships, perceiving properties, and reasoning based on agreed properties” (Mason, 2008, p. 35). As attention shifts from one focus to another and/or from one form to another, its structure alters which enables the learner to establish connections, perceive relationships, and appreciate new ideas. Holding wholes involves observing a mathematical object with or without focusing on its mathematical characteristics, typically for a brief period before transitioning to discerning details, which involves marking distinctions and recognising significant features. Recognising relationships occurs when the learner identifies specific relations between elements of a mathematical concept, such as a model, calculation, diagram, or equation. Shifting attention from recognising relationships to perceiving properties of specific elements is crucial for the development of mathematical understanding. Perceiving properties necessitates the learner’s “awareness of a possible relationship and look for elements to fit it, thus leading to generalisation” (Mason & Johnston-Wilder, 2004, p. 60). Lastly, reasoning based on agreed properties involves formal mathematical reasoning related to previously identified properties, “independent of particular objects, properties, as the only basis for further reasoning” (Mason & Johnston-Wilder, 2004; Mason, 2008, p. 37).

The theory of shifts of attention has been applied in studying progressions of mathematical problem-solving (Voutsina et al., 2019). It can also be used to explain changes related to shifts in the object and structure of learners’ attention regarding any mathematical concept, including decimal fractions. As students engage with mathematical tasks and representations, there are continual changes in the focus and structure of their attention (Attard et al., 2016). For a learner, this shift occurs while detecting apparent motion from saccadic eye movement, which can suddenly switch to an awareness of details amidst previously undiscerned information (Wei et al., 2023). Mathematics learning evolves through these shifts in attention, coupled with students’ increasing awareness of them. Voutsina et al. (2019) explored dynamic changes in how problem-solving strategies were articulated and conceptualised when students shifted the structure of their attention in response to shifts in the mathematical object being focused on. The findings revealed microqualities that influence the structure of attention among different students during various phases of mathematics learning, offering valuable insights into the qualitative dynamics of change in learning (Voutsina et al., 2019).

2.4. The Relationship Between the Theories

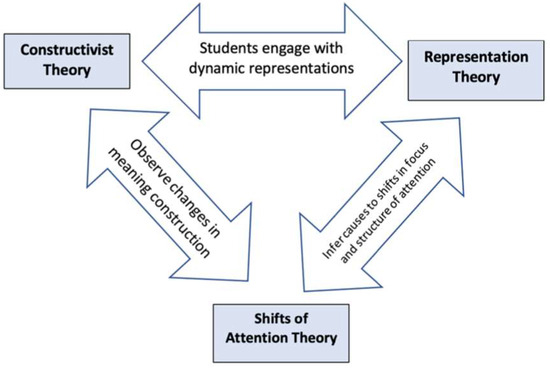

Mason (2010) perceives learning as the dynamic shifting of attention in both form and focus, encompassing what is being attended to and how it is being attended to by the learner. From his research emerges a compelling assertion that mere engagement with a mathematical task is insufficient for effective learning. Instead, there is a necessity for the integration of experience and sense-making, requiring a transformation of attention. This transformation entails shifting the learner’s attention from complete immersion in the task to a broader perspective that internalises the new concept or approach (Mason, 2010). Dynamic representations of decimal fractions have the potential to guide learners’ shifts of attention. The dynamic nature of digital manipulatives induces shifts in the object of students’ attention as they actively interact with the mathematics content, as well as in the structure of their attention concerning how they perceive features of the mathematics representation and the embedded mathematical concepts (refer to Figure 1). Understanding these shifts in what and how learners attend to features of decimal fractions is crucial for advancing researchers’ comprehension of the dynamics of change in learning.

Figure 1.

Diagram of relationship between three theoretical perspectives: constructivism, representations in mathematics, and ‘shifts of attention’.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative methodology, using task-based interviews in conjunction with microgenetic methods for data collection and analysis (Chinn & Sherin, 2014). Task-based interviews, when well designed and effectively implemented, offer insights into how students construct knowledge, their cognitive processes, and their interpretations of learning situations and tasks (H. Ginsburg, 1997). Microgenetic methods facilitate detailed analysis of students’ reasoning, particularly in research designs incorporating task-based interviews (Chinn & Sherin, 2014; Siegler, 2006). The method of investigating moment-to-moment processes of learning is important for this study as it connects ‘how’ the students are engaging with the dynamic digital representations with ‘what’ decimal concepts are being attended to by the students. In doing so, identification of specific affordances that prompt changes in conceptual understanding can occur.

3.1. Task-Based Interviews Overview

Task-based interviews serve the dual purpose of observing mathematical behaviour and drawing inferences about the problem solver’s cognition and/or affect from the observations (G. Goldin, 1993). Consequently, tasks must be sufficiently open-ended to allow each student to respond in their preferred manner and designed to encourage dialogue between the researcher and student (Hunting, 1997). The primary aim of the interview was neither to teach nor to test knowledge, but rather to explore the student’s thought processes and interactions with mathematical representations (Gorman & Way, 2018).

3.2. Task Design

The dynamic digital representations incorporated in this study were selected due to their compatibility with the aim of the research questions. Four virtual manipulatives were chosen from a larger list of seventeen web-based apps after exploring and analysing the affordances and constraints of each potential digital tool. The process of selecting the dynamic digital representations to be included in the study involved a systematic evaluation based on predefined criteria, including mathematical accuracy linked to decimal density, decimal magnitude and/or decimal place value, age-appropriate interactivity, pedagogical effectiveness, and alignment with the study objective. Each tool was assessed for its potential to provide meaningful visualisations, foster conceptual understanding, and support student engagement. The final selection prioritised tools that included a range of linear, area, and symbolic representations of decimal place value, density and magnitude.

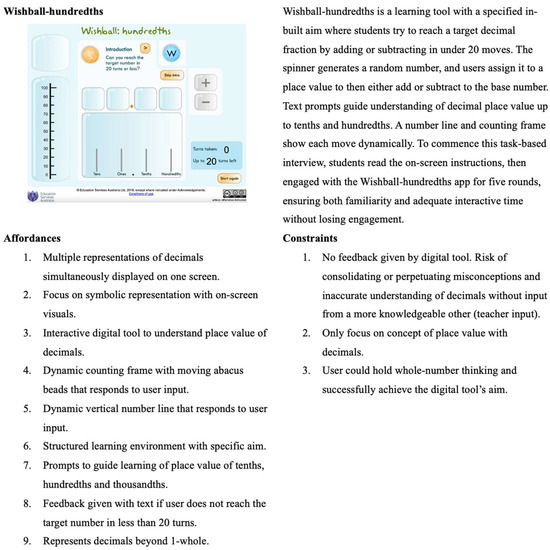

The number-line-based, place-value symbolic, and area-model dynamic digital representations of decimal fractions used were in the form of applets, which were embedded into a webpage and displayed using a web browser (Moyer et al., 2002). Retaining the well-documented affordances of manipulatives that have been used for decades by teachers and students in classrooms, the four dynamic digital representations; Wishball-hundredths, Decimal Strips, Zooming in on Place Value, and Zoomable Number Line, offered additional advantages and affordances to their static counterparts. An in-depth list of affordances and constraints for each digital tool is outlined below in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the Wishball virtual manipulative and description of tasks (https://www.scootle.edu.au/ec/viewing/L869/index.html) (accessed on 30 May 2023).

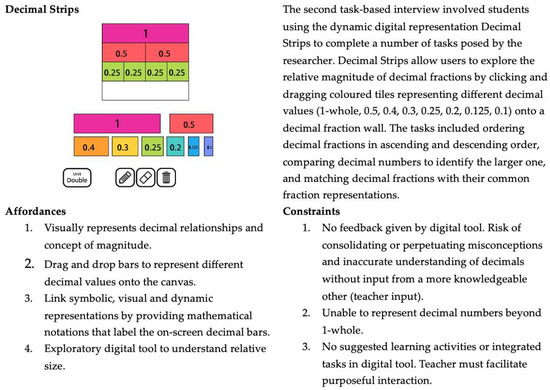

Figure 3.

Screenshot of the Decimal Strips virtual manipulative and description of tasks (https://toytheater.com/decimal-strips/) (accessed on 6 June 2023).

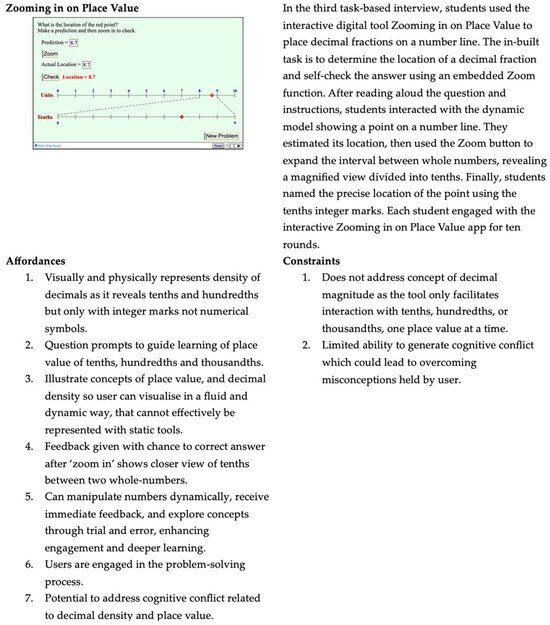

Figure 4.

Screenshot of the Zooming in on Place Value virtual manipulative and description of tasks (http://www.sineofthetimes.org/zooming-in-on-place-value/) (accessed on 13 June 2023).

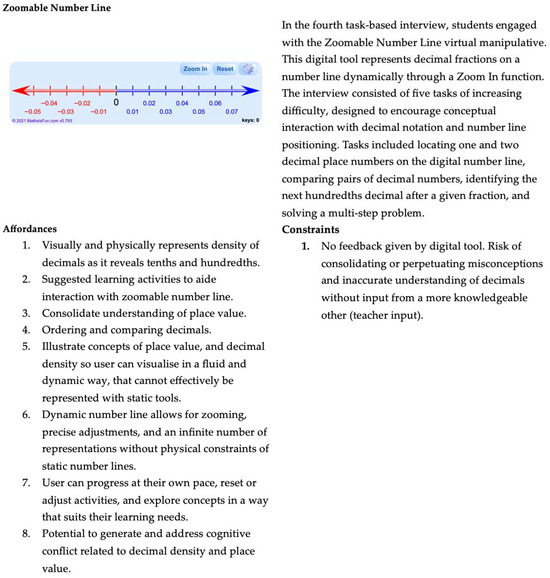

Figure 5.

Screenshot of the Zoomable Number Line virtual manipulative and description of task (https://www.mathsisfun.com/numbers/number-line-zoom.html) (accessed on 20 June 2023).

The task-based interviews began with a base-line task involving a conversation about decimal fractions where the student was asked to identify and explain the concept of a decimal fraction. They then located a sequence of one and two decimal place numbers on a static paper-based number line. In doing so, the researcher was able to compare the data collected from the task-based interviews with the results from the introductory activity and therefore form some conclusions in relation to the students’ prior knowledge. Following this, four separate task-based interviews were conducted, over a four-week period, where the students interacted with a different dynamic digital representation during each session. For two of the task-based interviews, a set of tasks were designed with increasing levels of challenge, to encourage the students to interact conceptually with decimal notation, number line positioning and area models. Probing questions were used by the researcher to encourage further explanation, such as “Can you tell me what you are thinking?”, while maintaining neutrality regarding the correctness of responses (Gorman & Way, 2018).

3.3. Participants and Interview Procedure

The participants in this study consisted of Year 4 students (9–10 years old), a grade level chosen because the New South Wales (NSW) state syllabus introduces decimal notation for tenths and hundredths at this point (NESA, 2012). Typically, students in this grade are still in the early stages of understanding of rational numbers in the context of decimal fractions which was true for the participants in this study. Individual participants held a different level of understanding that is influenced by their acquisition of the anticipated prerequisite knowledge related to decimals from Year 3. The NSW Mathematics Syllabus positions Year 3 students to consolidate conceptual knowledge of fractions and their relationship to decimals, as well as explore decimal fractions through practical activities and contexts such as money or measurements.

Six participants were selected from a single Year 4 classroom based on their decimal comparison pre-test results. One criterion for participation was the students’ ability to articulate their mathematical thinking and reasoning verbally. The class teacher confirmed that the selected children would feel comfortable engaging in one-on-one discussions with the researcher. Although the participants were not intended to be representative of the entire class, the researcher chose six students encompassing a range of mathematical achievement levels to account for potential differences in how low and high achievers interacted with the dynamic digital representations. Due to the time-consuming nature of data collection and analysis required in microgentic designs of research, generally a small number of participants are selected to provide the rich data sets (diSessa, 2017). Choosing six children was deemed sufficient to capture a variety of student responses (Marton, 1986).

3.4. Procedure and Data Collection

Data collection for this study consisted of two key phases:

- An initial decimal comparison pre-test;

- Four individual task-based interviews each focussing on a different dynamic digital representation.

3.4.1. Pre-Test

To initiate the data collection phase, the lead researcher designed and administered a pre-test to all students in a Year 4 class. This pre-test tasked students with comparing pairs of decimal fractions and determining the larger decimal, such as 0.4 and 0.457. These pairs of decimal fractions were sourced from Stacey and Steinle’s (2003) Decimal Comparison Test, a tool utilised for categorising students’ understanding of decimal notation. The research-based test is accompanied by marking instructions and an analysis tool to allocate a code to each question that indicates the students’ thinking with a classification of either Longer-is-larger, Shorter-is-larger, or Apparent-expert. Using the results from the Decimal Comparison Test six participants were nominated that spanned a range of results and appeared to hold different mathematical knowledge within the area of decimal fractions.

3.4.2. Task-Based Interviews

The four dynamic digital representations used were Wishball-hundredths, Decimal Strips, Zooming in on Place Value, and Zoomable Number Line. The researcher worked individually with each participant in four 30 min sessions which proved to be sufficient time to collect quality data and simultaneously brief enough to maintain age-appropriate student concentration levels. In the task-based interviews, the role of the interviewer was to facilitate the student’s engagement with the mathematical tasks while maintaining a neutral stance to ensure authentic insight into their decimal thinking. The interviewer guided the tasks by prompting reflection and encouraging explanation, rather than providing evaluative feedback or hints toward correct answers. Neutrality was maintained through the use of open-ended questions including “Can you tell me more about your thinking?” and non-judgmental verbal and facial responses. This approach minimised interviewer influence and allowed the student’s reasoning, misconceptions and conceptual changes to emerge naturally through interaction with the tasks.

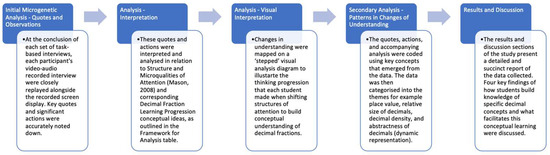

3.5. Microgenetic Analysis

The data collected from the task-based interviews were analysed using a microgenetic approach. The correlation between one-on-one task-based interviews and the principles of the microgenetic method is evident when gathering intensive data from learners over a period of time to capture a record of moment-by-moment learning processes (Chinn, 2006). Microgenetic methods of analysis involve closely examining what learners do and say over several task-based interviews, thus allowing researchers to draw conclusions about what prompts knowledge change, how learning occurs, and other aspects of the processes of acquiring conceptual understanding (Voutsina et al., 2019).

Data analysis began with repeated viewings of the video–audio recordings at the conclusion of each task-based interview where the researcher deduced new understandings that the participants had gathered. Particular attention was given to the manipulation of each digital tool, the mathematics concepts demonstrated, and the relationship between the two. These significant sayings and doings were accurately documented in chronological order. As qualitative microgenetic studies focus on tracing and documenting points of change in learning through analysis of each individual’s verbal and physical behaviours, a high density of observations was required. This entailed multiple viewings of the data from task-based interviews to explore “development of individual students’ knowledge, reasoning, problem solving and understanding of mathematics concepts through a qualitative lens” (H. P. Ginsburg, 2009, p. 113). A framework for analysis was designed by the researcher as a reference tool when analysing the verbal reasoning and manipulative actions the participants made. The ‘Shifting Attention with Decimal Concepts Framework’ (see Table 1) correlated Mason’s five components of structures for attending with key decimal fraction concepts that form a sound conceptual understanding as outlined in the ACARA National Numeracy Learning Progression. This analysis tool was used alongside a microgenetic approach to data analysis to discern observable shifts in how and what the participants were attending to as they engaged with the four dynamic digital representations of decimal fractions. The coding process for the microgenetic analysis was guided by the ‘Shifting Attention with Decimal Concepts Framework’, which provided a structured lens for identifying moments of conceptual change as students engaged with each dynamic digital representation. Each video-recorded task-based interview was transcribed and segmented into fine-grained episodes, which were then coded to capture shifts in the students’ focus, strategies and reasoning about decimal concepts. To enhance reliability beyond expert review, a subset of transcripts was independently coded by a second researcher to ensure consistency in the application of the framework. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved collaboratively, leading to refinements in the coding scheme. Validity was further strengthened through triangulation across multiple data sources, including screen recordings, student verbalisations and interviewer observation notes. This allowed for a more comprehensive interpretation of the students’ evolving conceptual understandings.

Table 1.

Shifting Attention with Decimal Concepts Framework.

In addition, a ‘stepped’ visual analysis tool (See Figure 6) was designed to help map the thinking progression that each student made when shifting structures of attention to build conceptual understanding of decimal fractions. The layered tiles are annotated with each structure of attention alongside the corresponding key decimal knowledge concepts and skills that contribute to decimal sense. Whilst employing a microgenetic analysis approach, links were made between the actions and sayings demonstrated by each student and a specific decimal concept with the corresponding structure of attention. In addition, considerations were made into how the students’ attention flittered between any particular stage of the diagram. For example, attention shifts that occurred between discerning details (what is being referred to), recognising relationships (between discerned details), and perceiving properties (as being instantiated). The changes in decimal conceptual understanding were recorded along the side of the diagram and were sequentially numbered to represent each observable attention shift during the student’s interaction with the dynamic digital representation. Annotated versions of this visual analysis tool are used in the findings and discussion section of this paper.

Figure 6.

‘Stepped’ Visual Analysis Tool Diagram.

Following this, individual student’s responses and actions were interpreted to determine shifts in what each student was attending to and consequently make inferences about how the change had occurred. This interpretation was achieved through a secondary analysis as detailed in Figure 7, by searching for similarities and differences across the students’ profiles and identifying patterns that emerged. The most prominent moments of conceptual change were identified from the learning progressions that students exhibited when shifting attention from one structure to another. This layer of analysis was completed for four key episodes of pivotal learning for all six students and were examined for evidence of the role played by each dynamic tool. The analysis and interpretation were used to draw inferences into how students build knowledge of specific decimal concepts and what facilitates this conceptual learning. Four decimal principles that linked to the conceptual changes and emerged from the students’ engagement with the dynamic representation are used as the key findings in Section 4 Results.

Figure 7.

Diagram showing five key stages of data analysis.

To enhance validity, the primary researcher’s analysis and interpretation of results were cross-referenced with two additional experts in mathematics education research. One expert served as the researcher’s tertiary supervisor, while the other was both a published mathematics education researcher and an advisor for the NSW Department of Education. By involving these external reviewers in assessing the audio–video recordings of task-based interviews and the researcher’s written analysis, credibility was established in the interpretation of the qualitative data.

4. Results

The findings outlined in this paper present a synthesis that emerged from detailed analysis during the concentrated interpretation of students’ verbal reasoning and manipulative actions whilst engaging with four digital tools. An analysis of the specific affordances within each dynamic digital tool that enhanced students’ conceptual understanding of decimal fractions is presented in Table 2. This table aims to present the mathematical concept or process that each digital tool supported. Discerning similar pathways that students followed when shifting attention from one structure to another allowed inferences to be drawn about how students build knowledge of specific decimal concepts and what facilitates this conceptual learning. Four key findings emerged from the data analysis that detail the formation of four distinct decimal principles and skills related to decimal place value, relative magnitude and decimal density. These findings are used as sub-headings in this section alongside student evidence and examples to illustrate each conceptual finding. The excerpts were chosen because these students’ thinking patterns and verbal reasoning most clearly demonstrate the conceptual changes that occurred in their understanding of decimals. When an evidence snapshot from a task-based interview is described, it is interpretated using the ‘Shifting Attention with Decimal Concepts Framework’ to deduce the unique dynamic digital affordances that prompted changes in conceptual understanding related to decimals.

Table 2.

Summary of findings highlighting key affordances used by students to prompt changes in decimal fraction conceptual understanding.

4.1. Finding One: Students Demonstrated a Change in Understanding Related to Decimal Density Through Noticing the Dynamic Display of Continuous Decimal Place Values on the Zoomable Number Line

The continuous property of numbers refers to the fact that between any two distinct numbers, there is an infinite quantity of other numbers. Understanding that between 0 and 1, there are infinitely many decimals, and the density of decimals is high, requires knowledge of the continuous property of numbers. This concept is highly abstract, and some learners experience cognitive conflict when they are first exposed to the idea as it opposes their whole-number knowledge.

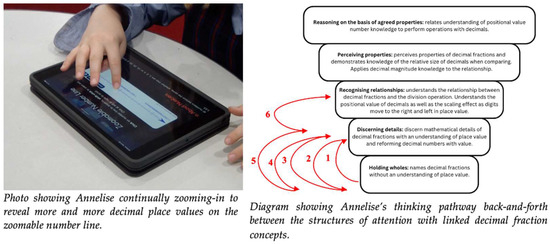

During the Zoomable Number Line interview five out of the six students demonstrated a change in conceptual understanding related to decimal density directly linked to the research question What conceptual changes occur when children attend to features of dynamic digital representations of decimal fractions? These five students shifted attention from a starting place of either holding wholes or discerning details without knowledge of the relationship between decimals and the division operation, which is a precursor to understanding decimal density, to a more accurate understanding of this specific concept. They connected the details discerned in the dynamic zoomable number line with their decimal place value knowledge to uncover the continuous property of decimal numbers. The individual learning journeys that the students took to reach this new understanding had an interesting commonality whereby all students cycled through at least two-rounds of hypothesising when attempting to explain why the Zoomable Number Line continued to reveal an increasing number of decimal place values. This self-questioning was evidence of cognitive confusion as the students attempted to recognise relationships between the positional value of decimals and the continued division of place values that resulted in another decimal digit being displayed on the dynamic number line, a discerned detail. Annelise was one such student who completed two cycles of shifting attentions between discerning details and recognising relationships before she could articulate the continuous property of decimals and therefore describe decimal density. The evidence snapshot below details the interaction between Annelise and the interviewer that exposed a change in conceptual understanding related to decimal density. In addition, the ‘structures of attention’ diagram (see Figure 8) maps the observed learning progression Annelise moved through to gain familiarity and facility with the shifts of attention necessary in order to have recognised relationships readily available for further thinking.

Figure 8.

Annotated images of Annelise’s interaction with the zoomable number line including a diagram showing Annelise’s shifts of attention in sequential order.

Annelise was freely investigating the zoomable number line app by continuously zooming in which enabled her to recognise a relationship of never-ending betweenness which is labelled ‘density’. She was interested in discovering how many place values could be revealed in a decimal when she predicted a maximum and then tested her hypothesis. The accompanying verbal exchange is detailed below:

Annelise: [Held down zoom-in function to continually reveal more and more decimal place values] Oh wow… there are so many numbers.Interviewer: How many numbers are after the decimal point?Annelise: Six.Interviewer: What do you think is the maximum number of decimals there are after a decimal point?Annelise: Maybe 10 [held down zoom-in function to continually reveal more and more decimal place values] I just counted 12 numbers after…maybe it stops at 20” [held down zoom-in function to continually reveal more and more decimal place values] “I don’t think it will stop.Interviewer: Why don’t you think it will stop.Annelise: Because there are infinite numbers.

At the commencement of the interview, Annelise displayed an incomplete understanding of the abstract concept of decimal density. In the example recounted above, Annelise was learning to extend the place value to tenths, hundredths, thousandths and beyond, supported by using the zoomable number line to recognise how the numbers increase and decrease. The zoom-in and zoom-out functions show how the decimal number system is based on powers of ten and helped build Annelise’s knowledge of decimal density. Concrete manipulatives may only go as far as representing thousandths, however the digital zoomable number line with its dynamic affordance allowed Annelise to notice that decimals can always be divided into ten smaller pieces. Furthermore, Annelise appeared to connect what she witnessed in the continually zooming-in number line with her knowledge of the concept of infinity in that, the numbers continue to get smaller without ending, just as they can continue to become larger without ending. The analysis suggests that by exploring a powerful digital learning tool, Annelise could reason about her observations which ultimately helped her determine her own methods to explain the size and value of decimal numbers and therefore discover why the decimal place values continue forever.

One student’s attention remained within the attention structure of discerning details when freely investigating the Zoomable Number Line. Yehali was questioned as to the maximum number of digits that come after the decimal point. Her response was “maybe seven…” before she held down the zoom-in function on digital tool which continually revealed more and more decimal place values. Yehali commented “I counted 9 [decimal places] …maybe it will go up to the 10” She again held down the zoom-in function and revealed additional decimal place values, her final explanation was “there’s 14 now, it probably goes up and up.” When asked to explain why it “goes up and up”, Yehali was unable to produce a mathematical reason for the continuous property of decimals. At the commencement of this interview Yehali exhibited thinking which indicated that she was treating decimals as other whole numbers to the right of the decimal point. This was a result of her viewing the decimal point as separating two individual whole numbers. However, Yehali’s attention shifted from holding wholes to discerning details when she witnessed the Zoomable Number Line dynamically expand to display ten-tenths between two whole numbers. A limitation with conceptual knowledge development is evident in Yehali’s experience, as she could not independently relate what she uncovered on the Zoomable Number Line with the abstract concept of infinite decimals existing between any two whole-numbers. This evidence excerpt highlights the importance of students understanding the continuous property of decimals in order to grasp the concept of decimal density.

4.2. Finding Two: Students’ Knowledge of Decimal Magnitude and Decimal Place Value Determined Their Success with Decimal Comparison Tasks and How They Used Decimal Strips

All six students involved in this study demonstrated a shift in conceptual understanding linked with decimal place value which they used when comparing pairs of decimal numbers. Thus, a second form of conceptual change was found to answer the research question What conceptual changes occur when children attend to features of dynamic digital representations of decimal fractions? In order to successfully determine the larger decimal value when comparing a pair of decimal numbers, the students needed knowledge of the decimal unit that a digit represented. For example, when engaging in a decimal comparison task that used the Decimal Strips digital tool, an understanding of the magnitude of tenths and hundredths was needed to decide whether 0.2 or 0.25 had a larger value.

Those students who initially demonstrated a strong link between decimal understanding and the base-10 numeration system used the digital tool Decimal Strips differently to other students who displayed conceptual confusion based on their treatment of decimals as whole numbers. These same students operated with facility and familiarity when ordering decimals, and experienced shifts between forms of attention that enabled them to offer mathematical explanations which included the relationship between decimal place value and measurement concepts. For example, Annelise needed to compare a series of two decimal numbers to determine larger decimal value during Interview 2: Decimal Strips. Annelise acknowledged her insufficient decimal knowledge to answer the comparison question. The decimal task is detailed below:

Interviewer: “Which decimal in this pair is larger?” [Presented card with 0.2 and 0.25 decimals].Annelise: “This is what I was looking at before. I’m not sure I’ll have to check.” [Dragged aqua 0.2 strip, and green 0.25 strip onto two blank fraction wall rows]. “They are very close but this one [pointed to green 0.25 strip] is the biggest.”Interviewer: “Why do you think they are so close in value?”Annelise: “Maybe the zero-point-two has something else on it you just can’t see it.”Interviewer: “What would be on the end?”Annelise: “It could be twenty-something and then this one [pointed to yellow 0.3 strip at bottom of screen display] could be thirty-something.”

Annelise was deeply aware of the affordances of the dynamic digital representation to display the relative size of decimal fractions as was needed in this decimal comparison challenge. She relied on the dynamic representation of Decimal Strips to accurately compare the relative sizes of 0.2 and 0.25 decimals and concluded the values were “very close but this one [pointed to green 0.25 strip] is the biggest.” Her second attempt at explaining why 0.25 was slightly bigger than 0.2 was correct due to her use of the dynamic affordances within Decimal Strips to manipulate length-representations of the relative size of decimals when comparing pairs. This is an example of cognitive confusion being generated by the dynamic display of decimal fraction strips and their relative sizes. Annelise resolved her cognitive confusion through shifting attention structures as she engaged with the sophisticated functions of the Decimal Strips digital tool. She gave evidence of shifting between three separate structures of attention, resting eventually on recognising a relationship between number size and decimal-strip length, ultimately speaking as if she was calling upon decimal-size, with the on-screen decimal-strip lengths as her reference. In the beginning Annelise operated within the microquality of discerning details to use place value knowledge to predict the larger decimal fraction. She then moved towards recognising relationships as she consolidated her understanding of the decimal-fraction link whereby decimals are the result of dividing the whole into equal parts. Finally, Annelise shifted her attention to perceiving properties by connecting her knowledge of the relative size of decimals when comparing and applying this concept to the relationship with measurement.

Annelise’s learning progression was mirrored in all students’ attempts to compare pairs of decimal numbers whereby knowledge of the decimal unit a digit represents determined their success with the task. This observation seeks to answer to the research question How do shifts in attention meditate engagement with these representations? Each student began with identifying the place values of the decimal by locating and naming the digit positions in a multi-digit number. Those students who correctly activated their place value knowledge used the numerical information of a decimal unit to complete number comparison tasks. Finally, the two students who demonstrated place value computation integrated their place value information in arithmetic tasks. The student evidence from this study highlighted the relation of dependence and inclusion between the stages of conceptual acquisition as a pillar in the learning developmental model. Students needed knowledge of lower levels to develop successive structures of attention and to progress beyond their current decimal thinking they had also developed the prior levels.

4.3. Finding Three: Relating Decimal Fractions with the Division Operation Was Prompted by Student Interaction with Zooming in on Place Value as Well as the Zoomable Number Line, and Positioned Students to Understand the Relative Magnitudes of Rational Numbers

Understanding decimals is a multi-dimensional undertaking. Students need to coordinate place value concepts with aspects of whole number and fraction knowledge. Making the transition to understanding decimals relies on having a thorough understanding of previous concepts fully integrated with new information. Five of the students were identified, through a Decimal Comparison Test (Stacey & Steinle, 2003), as holding misconceptions that interfered with their knowledge of decimal concepts. Analysis of the test results indicated that three students’ thinking was classified as Longer-is-larger, two students’ thinking as Shorter-is-larger, and one student was an Apparent-expert. In the initial interview conducted to gather data on their current knowledge of decimal fractions including their misconceptions, conceptual understanding of decimal fractions involving place value, magnitude and density, the students were asked to explain what a decimal fraction was. No student responded with reasoning that included the idea of decimals representing parts of a unit resulting from dividing the whole into equal parts.

In this study, a number of the tasks required students to order sets of decimals correctly using knowledge of the relative sizes of decimals. A student’s success with these tasks appeared to be determined by their knowledge of the relationship between decimal notation and the division operation. Two dynamic representations, Zooming in on Place Value and the Zoomable Number Line, seemed to be particularly effective in showing the relationship between decimal fractions and the division operation. The data revealed that all students developed a real sense of the size of decimal numbers through their engagement with these two dynamic representations. This was demonstrated in their consistent success with locating decimals on a number line as well as their verbal explanations that accompanied decimal comparison tasks when using the Zoomable Number Line.

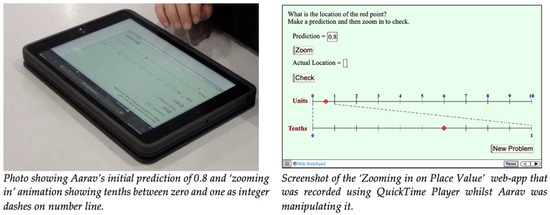

Aarav was one such student who made observable growth in his understanding of decimal magnitude. The transcript below outlines the student’s thinking in response to the interviewer’s questioning during Interview 3: Zooming in on Place Value. Visual references of Aarav’s engagement with the digital tool are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Annotated images of Aarav’s interaction with Zooming in on Place Value.

Aarav: I think the dot is three away from one… so zero point eight. [Typed the predicted location in and watched the ‘zooming in’ animation reveal the location between zero and one with tenths integers marked as dashes on the number line].Aarav: It’s actually zero point six.Interviewer: How do you know that is the answer?Aarav: Because I counted along zero point one, zero point two, zero point three, zero point four, zero point five, and zero point six.Interviewer: What is the second number line showing?Aarav: Oh, I understand it’s showing the number after the decimal point, the tenths.Interviewer: Did the zoomed-in number line help you answer the question?Aarav: Yes, seeing the closer numbers on the number line helped me, I could see exactly where the decimal was with it zoomed in and it was easier.

Aarav had difficulty initially predicting what tenths decimal was located on the number line when prompted to name the decimal that was marked on an unlabelled position. However, with assistance in the form of the ‘zooming in’ animation as the interval between two whole numbers expands showing a magnified view divided into tenths, he successfully solved later questions. Aarav engaged with the dynamic nature of the Zooming in on Place Value web-app to assist with locating tenths decimal fractions on a number line. The student used the animated zooming feature embedded in the learning tool to eliminate the abstractness of decimals. His manipulative interaction with the dynamic representation, enhanced his understanding of decimals, as he was able to ‘see’ notions that would otherwise be ‘unseeable’.

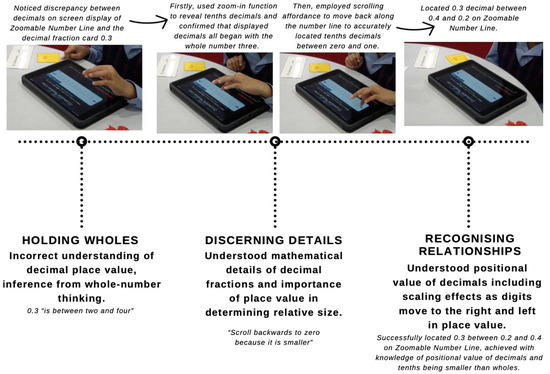

The Zoomable Number Line representation also offered dynamic experiences for the students to see decimal concepts in motion. Each student overcame the misconceptions they initially held to successfully compare the relative size of decimal pairs and determine the larger value. The pathway of thinking progressed from holding wholes with an incorrect understanding of decimal place value to a more accurate internal representation of decimals by discerning details presented on the dynamic number line. A clear supporting answer to the research question What conceptual changes occur when children attend to features of dynamic digital representations of decimal fractions? In the task-based interview the students were asked to locate the decimal 0.3 on the zoomable number line and describe its location by stating “it’s between _ and _”. A majority of the students responded with incorrect initial answers due to the presence of whole-number thinking or incomplete decimal-fraction link thinking. However, as a result of their interactions with the Zoomable Number Line, each student recognised relationships between digits in the decimal as they understood the positional value to the right and left of a decimal point and used this knowledge to deduce that tenths were a smaller value than wholes, and hundredths as an even smaller value. The diagram below, labelled Figure 10, outlines the three structures of attention that one student, Yehali, held during a moment of conceptual change about decimals. The verbal exchange between the interviewer and Yehali uncovered a change in understanding from her thinking that the location of 0.3 was between “Two and four…” to then articulating that the decimal was “smaller” than the predicted whole numbers and she needed to “scroll backwards to zero” to locate the decimal. As she transitioned back and forth between gazing, discerning details and recognising relationships, Yehali’s decimal narrative became more succinct which is evidence of her increasing sophistication of decimal comprehension. Each microquality of attention is labelled alongside the corresponding decimal fraction concept that Yehali acknowledged as well as the specific affordances within the Zoomable Number Line representation that prompted each shift in attention.

Figure 10.

Diagram showing three structures of attention with linked decimal fraction concepts that Yehali showed evidence of are noted below the timeline. Yehali’s actions and sayings associated with each shift in attention and consequent change in decimal conceptual understanding are annotated in italics above the timeline with a screenshot from interview video-recordings.

4.4. Finding Four: Discovering Decimal Magnitude with Tenths and Hundredths Required an Understanding of Reforming Decimal Numbers with Value, as Dynamically Displayed in Wishball-Hundredths

Students who developed a sound understanding of decimal magnitude through the feedback and dynamic features of Wishball-hundredths experienced shifts in attention related to recognising relationships between decimals and the division operation such as ten-tenths being equal to one-whole. These same students could apply this knowledge of reforming decimals when estimating the addition and subtracting of decimals. A finding directly related to the research question How do shifts in attention mediate engagement with these representations? Aarav was one-such student who experienced cognitive confusion during the Wishball-hundredths interview when he viewed the decimal place values as separate digits without any relation to each other. Aarav encountered the spinner number 9 and current starting number 51.45 early in his interactions with the Wishball-hundredths game. He articulated his confusion:

Aarav: I don’t know what to do with this number because if I minus for any of them [place value digits] it will automatically be zero but if I plus then it is going to be too high… okay I am going to risk it and add it to one to make it ten and then I’ll subtract on the next spin.[Screen displayed 60.45 as the new starting number whilst the dynamic counting frame simultaneously carried over 10-ones to the tens place value].Aarav: I understand it now… because I added nine-ones to make ten-ones in total so it had to jump over to the tens place value.[Screen displayed next spinner number was 8 alongside the current starting number 60.45].Aarav: I could add it here [gestured to the 4-tenths place value] which would give one to this number [gestured to ones place value] and then it would be closer to two [the target ones digit].Interviewer: Is the counting frame helping you?Aarav: Yes, I can see how many I need to add or minus to each number.

At this point of cognitive confusion, Aarav’s attention had shifted back to discerning details. Without the ability to partition and reform place values across the decimal fraction it is difficult to successfully recognise relationships between the positional value of decimals and the scaling effects as decimals move right and left in place value. This is a key point of understanding between attending to discerning details and the higher-order mathematical thinking process of recognising relationships. A shift between these structures of attention can only be completed with conceptual knowledge of using place value to partition decimals which is a precursor of estimating relative size of decimals. As such, a change in understanding depends on students being able to fluently reform decimal numbers with value. Aarav shifted between discerning details and recognising relationships six observable times across the timeframe of one-round of Wishball-hundredths (See Figure 11). Three other students demonstrated the same pattern of thinking when they shifted back and forth between these two structures of attention. The time spent within and between discerning details and recognising relationships suggests that the process of acquiring mathematical knowledge involves many numerical and symbolic details being discerned, with each new mathematical detail being understood through a reasonable explanation that is an extension of current understandings. As such, the students who had limited prior-conceptual understanding of decimal place value experienced cognitive confusion when attempting to explain why their digital input during the Wishball-hundredths interactive activity resulted in different size movements on the vertical number line.

Figure 11.

Diagram showing Aarav’s thinking pathway back-and-forth between the structures of attention with linked decimal fraction concepts, shifts of attention are numbered in sequential order.

The feedback embedded within the interactive app prompted conceptual changes related to the students’ decimal number knowledge. Multiple representations of the changing decimal fraction were displayed on a dynamic vertical number line, and a dynamic place value counting frame. The students utilised both of these representations to assist with gauging the relative size of decimals, particularly the scaling effects as digits move to the right and left in place value. This shift in attention from discerning details to recognising relationships demonstrated an expansion of conceptual understanding from the students initially stating decimal place values to then understanding the decimal magnitude that each place value represented.

Interestingly, two of these same students were then able to shift attention structures into reasoning on the basis of agreed properties. Both these students acknowledged that their thinking had changed from their prior understanding of performing operations with decimal fractions. The conceptual change from discerning details of the place values within a decimal to then being able to recognise relationships, perceive properties, and reason on the basis of agreed properties by performing operations with decimals with an understanding of positional value number knowledge, was the result of new learnings that occurred during the Wishball-hundredths game. These were prompted by unique affordances embedded within the web-app including the dynamic counting frame. The students were no longer only attending to discerning details but were able to hold multiple structures of attention simultaneously whilst tuning into a number of intertwined conceptual principles to demonstrate in-depth knowledge of the mathematical concepts related to decimal fractions. The students who gained facility in reasoning on the basis of agreed properties experienced brief but dynamic back and forth shifts between forms of attention before engaging in similar thinking. The two students showed their ability to flexibly use strategies for subtraction of decimals which was linked to the students attending to reasoning on the basis of agreed properties when they applied their understanding of positional place value to perform operations with decimals. The students demonstrated consideration of the relative magnitude of each place value in the two-digit decimal fraction alongside the carry over addition and subtraction principle.

5. Discussion

The discussion connects the findings from this study to the research questions and central prior research in the field. Limitations of the study are outlined alongside suggestions for further research with consideration of implications for theory and practice. A new-found understanding of how students developed decimal sense through their engagement with four dynamic digital representations is discussed in this section. Students noticed the Zoomable Number Line’s dynamic display of the continuous property of number which prompted a change in conceptual understanding related to decimal density, they also engaged with the Decimal Strips digital tool differently when comparing pairs of decimal fractions depending on levels of decimal magnitude and place value prior knowledge. Relating decimal fractions to the division operation was prompted by student interaction with Zooming in on Place Value and the Zoomable Number Line, positioning students to understand the relative magnitudes of rational numbers. Students also better understood decimal magnitude when they acknowledged reforming decimal numbers with value, as dynamically displayed in Wishball-hundredths. The dynamic affordances embedded within the digital tools interrupted the students’ flow of attention, to guide their conceptual learning journey of decimal fractions by generating cognitive conflict.

5.1. Structures of Attention and Changing Conceptual Understanding

It is acknowledged that students experience microqualities of attention in the learning journey and will switch back and forth between the multiple structures, often very rapidly (Mason, 2010). As such, it is important to notice shifts between these states of attention which can happen very quickly as these are vital in mathematical thinking. The structures are not a single progression pathway as learners will go back and forth as well as around in a cycle. In particular, noticing shifts from specific relationships to perceiving properties is pivotal, as this is the essence of mathematics. For a learner this shift unfolds while gazing to detect apparent motion produced from saccadic eye movement which can suddenly switch to awareness of details amongst a mass of other, undiscerned detail (Wei et al., 2023). As details are detected and discriminated, the mind automatically looks for relationships; differences and similarities. To do this requires something being invariant as a background against which to detect change (Mason, 2010). Recognising relationships focuses on particulars, however perceiving properties shifts to generalisable principles, and then to the particular as exemplary or paradigmatic. Formalising in mathematics is the overt action which accompanies a shift from perceiving properties to taking certain properties as definitive and so as the basis for reasoning. In each episode of evidence presented in the findings section, the student was no longer only attending to the entry-level structure of attention but was able to rapidly move between multiple structures whilst tuning into a number of conceptual understandings simultaneously to demonstrate in-depth knowledge of the mathematical concepts related to decimal fractions. This finding sought to answer to the study’s first research question What conceptual changes occur when children attend to features of dynamic digital representations of decimals fractions? For four of the students, this sequence occurred six times before they formalised certain properties as definitive and so as the basis for reasoning. This is suggestive that learners require time to articulate the relationships they recognise, and then need to confirm the relationship by searching for other instances of it within an object, before prompting a move to articulating the relationship as a property. The theoretical work of Pirie and Kieren (1991) on the nature of acquiring mathematical understanding posits a similar learning trajectory where the process of “folding back” is necessary for dynamical growth of mathematical thinking. What was observed through microgentic analysis of the students’ interactions with four dynamic digital tools, was a layering of increasingly sophisticated structures of attention as a compounded ‘stacking’ of mathematical details that were grouped in relationships to be extrapolated as properties before being generalised as principles to be reasoned on the basis of agreed properties.

A students’ change in understanding is not a unidirectional progression through structures of attention as separate modes of learning but rather a layering of more sophisticated microqualities of attention that build a more robust understanding of a mathematical concept (Clements & Sarama, 2004). This was particularly evident in the students’ engagement with the Wishball-hundredths interactive activity. They recognised the digital tool’s ability to reform decimal numbers from the feedback of a new starting number. Two students extended this concept to understand the subtraction trading principle being shown through the movement of the beads on the counting frame which prompted a shift in their attention. Furthermore, these students were able to learn from the feedback and reform the decimal independently during a later decimal subtraction calculation. Being able to estimate this mathematical move by performing both mental addition and subtraction calculations required a complex chain of reasoning and cognitive strategies including a “series of multi-step associations and procedures that involve facts, verbal chains, discriminations, concepts, and rules designed to bring about a response to a specified problem” (Kame’enui & Simmons, 1990, p. 294). The students linked understandings of decimal place value with the procedural knowledge and steps to add and subtract value from a decimal fraction. Within the short timeframe of this task-based interview, the two students formed an understanding of how subtracting decimals followed the same principles of renaming and trading as whole numbers and could exchange one unit for ten tenths and one tenth for ten hundredths (Martinie, 2014). Most importantly, they noticed this pattern was continuous and understood that when moving to the right of the decimal point, the numbers become ten times smaller (Martinie, 2014). The growth in the students’ conceptual understanding of decimal fractions was facilitated by the dynamic affordances embedded within the interactive activity of Wishball-hundredths namely the counting frame and vertical number line.

5.2. Provoking Productive Cognitive Confusion

All students demonstrated conceptual change as the result of productive cognitive conflict. Complete resolution of their confusion was dependent on the ability to generalise a discovery from the dynamic digital representation by linking what they saw displayed with their prior knowledge of decimal concepts. Across the four interviews, all six students engaged with a task that prompted them to question their current understandings of decimal fractions and begin to develop mathematical thinking that consistently included the decimal-fraction link. The thinking pathway provided an answer to the second research question How do shifts in attention mediate engagement with these representations? This was particularly evident when they worked through the decimal comparison tasks alongside the Decimal Strips and Zoomable Number Line dynamic representations. Seminal work by Swan (1983) found that students who experienced ‘cognitive conflict’ when learning gained better outcomes overall than students who learnt through ‘positive only teaching’. Decimal Strips generated cognitive conflict as it challenged the students’ current understandings and present misconceptions about decimals. It was not until they used the functions of the Decimal Strips web-app and dragged the coloured tiles onto the blank fraction wall that they explicitly recognised the relative values of tenths and hundredths. Steinle and Stacey (2004) detailed how teachers simply telling a student that their thinking is incorrect does not eradicate that student’s misconceptions. Rather, instructional techniques need to be implemented to assist students in overcoming or controlling the influence of misconceptions and systematic errors. Most of the students were able to self-correct their thinking by interacting with this powerful dynamic representation as it challenged their prior understanding of decimals and allowed them to examine their errors in thinking and misconceptions. For example, Annelise needed a mathematical reason as to why 0.3 was a longer decimal strip than 0.25, which was currently conflicting with her prior thinking that a longer decimal number was always larger in value. By dynamically comparing the relative sizes of these two decimals on the Decimal Strips web-app, she was able to connect this active learning with her understanding of decimal place value recently consolidated in the same interview, to determine that tenths are a larger value than hundredths and therefore despite 0.3 only having one decimal place it can be understood as ‘30-something’ as it is in the tenths place value. As such, this interview moment is a display of Annelise extrapolating her recognising relationships between the dynamically visual representation and correcting her ‘longer is larger’ decimal thinking to a generalisable understanding of decimal place value after she perceived properties of scaling place values to the left of a decimal point. Annelise’s experience was not a linear progression through structures of attention as separate modes of learning but rather a layering of more sophisticated microqualities of attention that build a more robust understanding of a mathematical concept.

5.3. Abstractness of Decimal Fractions

Students relied on the dynamic representations to reduce the abstractness of decimal fractions by visually showing the relative positions of decimals on a number line. This enabled them to recognise the relationship between decimal notation and the division operation, which leads to perceiving properties with the relative magnitude of rational numbers. The students could then reason and problem-solve to produce solutions to decimal location questions. Such a finding provided a second answer to both research questions What conceptual changes occur when children attend to features of dynamic digital representations of decimals fractions? and How do shifts in attention mediate engagement with these representations? Engaging with the dynamic zooming and stretching of the Zooming in on Place Value number line, eliminated the abstractness of the decimals and clearly presented the sequence of scores for the students to see. As a result, they were able to visualise the location of each tenths decimal to correctly predict the answer to the question. The digital functions of the Zooming in on Place Value interactive activity allowed them to uncover decimal concepts that a static number line is not able to illustrate. The ability to stretch out the number line between two whole-numbers, enabled students to see the continuous sequence of decimals, which assisted them when operating with different types of numbers (Teppo & van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, 2014). G. Goldin and Shteingold (2001) suggest, developing clear links between quantity, vocabulary and symbol is critical for conceptual understanding and the visual affordances of the digital tool illustrate the symbolic notation. A key affordance of the Zooming in on Place Value virtual manipulative is its ability to dynamically displaying ten-tenths between two whole-numbers. Through a ‘zooming in’ animation the digital tool reveals ten-tenths between two whole-numbers, and ten-hundredths between two-tenths in a two-step question sequence. This gradual release of information allows the student to build knowledge of decimal density as to the continuity property of rational numbers, whereby, between any two decimals there are an infinite number of other decimals (Widjaja et al., 2008). Furthermore, Aarav’s critique of the app in saying that he was able to see the number line with the decimals on it, indicated that the web-app was able to assist him in visualising the ‘abstractness’ of decimal fractions. Young students need support when developing their decimal sense and teachers therefore need to be sensitive to students’ ways of thinking and learning (Way, 2011). Quality teaching that employs quality representations such as a dynamic number line can assist students in better understanding decimal fractions.

Students may follow erroneous rules linked to whole-number thinking when trying to assimilate new knowledge about decimals with what they already know about whole numbers, place value and fractions (Moloney & Stacey, 1997). To develop their understanding of the continuous nature of the base-10 system, students need to relate decimal fractions with the division operation which can be difficult to illustrate using static representations.

5.4. Practical Implications for Classroom Practice