Abstract

This research aims to discover how inclusive education practices can determine the happiness and school satisfaction of students with physical disabilities through the development of self-concept. To achieve the objective of this study, quantitative research was used by administering a questionnaire to 403 students with special needs in secondary and high school in Saudi Arabia. The collected data were analyzed according to structural equation modeling. Our findings support the considerable agreement on the importance of inclusive special needs education for the happiness of physically disabled students. A total mediating effect of self-concept between ISNE and school satisfaction is also confirmed, which shows the great importance of the psychological dimension in special education. These results can orient and assist school managers in defining an appropriate educational environment for students with special needs. They can provide specific directives for raising the happiness and the quality of life of such students, making them more productive and socially active. Following this research, a new school framework can be drawn to protect, assist, and change the self-concept of students with physical special needs to shift the perspective of disability from an obstacle to overcome to an opportunity to exploit.

1. Introduction

Recently, an increasing number of studies evaluating student well-being have emerged [1,2,3] due to the importance of this concept and its impact on many relevant domains of student life [4,5]. A particular interest in the well-being of students with special needs has been shown by many international studies regarding sustainable development goals [6,7,8,9]. In this way, many researchers have tried to identify factors and determinants of students’ well-being in general and special needs students in particular [10]. Three main categories of student well-being determinants can be defined: socio-demographic, environmental, and satisfaction factors [5].

Here, school satisfaction seems to be important too. It is one of the main factors commonly cited by previous research in this field [11,12]. School satisfaction is considered a determinant factor impacting children’s happiness and healthy functioning in different areas, depending on how contextual factors interact and cooperate [13]. The impact of school satisfaction has been confirmed, yet the process through which a higher level of satisfaction can be attained remains unclear, particularly in the context of students with special needs.

A deeper analysis of the existent literature shows that inclusive education can be related to school satisfaction and can contribute to generating some specific positive conditions, enhancing satisfaction and, consequently, student well-being (subjective or psychological) [14] as well as parental satisfaction [15].

Arising from this, the Inclusive Special Needs Education (ISNE) program has been adopted to allow special educational needs students to be placed, integrated, and educated in regular classes with other students without considering eventual differences between them and assisted by the same teachers [16] at the appropriate level without considering their physical or development delay [17,18]. In addition, they must follow the same academic process without modification [19,20].

This has quickly become one of the major educational missions [16,21], supported by many studies, such as [22,23]. Further researchers have sustained this new inclusive educational approach and claimed that this constitutes a great opportunity for special educational needs students to build friendship with other students [24] and to develop positive behavior by being an active part of their community in addition to emulating their personal potential in non-academic and academic contexts [25]. Studies exclusively related to the effect of inclusive education on school satisfaction are very limited. Potential results regarding measures of inclusive education, its relevant practices, and the nature or significance of its impact on happiness or school satisfaction could not be identified. The authors of [26] insist on the importance of effective inclusive education due to the benefits it provides to students with special needs by stimulating their potential in all aspects and helping them indirectly develop a positive self-concept, enhance happiness, and increase success. Examining their self-concept is essential to gauging the happiness of students with special needs. This involves examining factors that contribute to a positive self-concept, including their relationships with teachers, the overall school climate, and the dynamics among students, irrespective of their differences [27,28]. This last point can constitute one of the major challenges of inclusive special needs education.

Saudi Arabia was one of the first Arabic countries to sign the Salamanca Statement and adopt the Action on Special Needs Education according to a specific framework (UNESCO, 1994). Inclusive education was the most popular action to satisfy students with special educational needs. However, this program has faced many difficulties in the Saudi context at the practical and theoretical levels [29]. The Regulations of Special Education Programs and Institutes (RSEPI) plays a crucial role in advocating for and supporting special education in Saudi Arabia. While various educational practices align with the global trend of inclusive education, the formal embrace of the concept of inclusive education in the country remains uncertain. Despite this, numerous educational initiatives are recognized as inclusive, reflecting a commitment to align with contemporary educational approaches on a global scale [30]. Therefore, greater efforts are being adopted to promote not only a conceptual approach to inclusive education but also a pragmatic approach compatible with SDGs and the respect of humanity [30].

This current study sustains this effort and tries to provide an operational approach to effective inclusive special needs education in Saudi Arabia by testing some of its relevant practices as well as their effects and benefits on the well-being, school satisfaction, and self-concept of physically disabled students in secondary and high school in Saudi Arabia. Physically disabled students are those who lose physical function or have an impairment of their physical function due to an accident or illness, which can limit some important life activities [31].

In other words, this research investigates how inclusive special needs education can affect the happiness of students with physical disabilities through school satisfaction and self-concept development in secondary and high schools in Saudi Arabia.

The following paper is composed of four main parts. The first part deals with research concepts at the theoretical level in terms of definitions and hypotheses. The second part presents the methodology, in addition to tools and research context. The third part details the results and discussion according to the previously developed hypotheses. The fourth and last part is a conclusion regarding the main research problem statement to deduce theoretical and empirical implications.

2. Review of Literature and Hypotheses Development

In this section, we will detail the literature related to inclusive special needs education, school satisfaction, self-concept, and happiness in general, while considering students with physical disabilities as students with special needs due to their physical special needs and limits in such areas as movement, posture, manipulating objects, motricity, and reflexive movement.

2.1. Inclusive Special Needs Education (ISNE) and School Satisfaction

Inclusive education is a platform that provides opportunities for students with special educational needs (SEN) to learn in a regular classroom without considering eventual differences between students. ISNE consists of admitting all students in the regular process of education and in collaboration with external specialized partners in special education if needed [32,33]. This requires a rigorous definition of all different students’ needs to be satisfied. ISNE focuses on a specific educational view while integrating the general perspective of simple, inclusive school development [34].

School satisfaction is directly related to the quality of the school experience according to students’ cognitive evaluations [35,36]. It depends on a comparative process of school circumstances and life domain with students’ standards that they have defined by themselves [37]. Based on many previous studies, such as [38], school satisfaction is important for each student and can affect considerable school outcomes as well as many mental aspects and students’ psychological health [39]. In this regard, [35] consider a successful school to be one where school satisfaction is treated as a (continued) process, not only an outcome to be reached with a lower level of internalizing behaviors and disengagement from school. In some studies, the positive and critical effects of school satisfaction on school achievement are confirmed [35]. Even if this impact seems less important to other researchers, a positive correlation still exists [38].

School satisfaction is used as an indicator of student well-being, which can depend on intrapersonal factors, internal environmental factors such as classroom context and teachers’ attitudes [40,41], and external environmental factors and events and environments outside of school [39,42]. It is also a major contributor to life satisfaction for secondary students in Korea [43,44,45,46] and middle school students in America [47,48,49]. Based on this analysis, the effect of school satisfaction on well-being and global life satisfaction is supported.

H1:

ISNE positively affects school satisfaction.

2.2. Self-Concept

Self-concept refers to a specific point of view of students with regard to their strengths and abilities: the ability of self-efficacy or to be self-regulated [50,51,52] and emotional and behavioral strengths [53,54,55]. The author of [51] suggests that self-efficacy determines the choices and activities of each individual as well as their persistence. According to this theory, self-efficacy regulates and fixes the individual’s ability to accomplish some tasks proportionally to his beliefs. Lacking such skills makes students unable to regulate their behaviors and/or emotions when facing adversity [56,57], which can cause fatigue, and students can be embarrassed. Developing such abilities and strengths will help to educate, support, and guide students of different pedagogical needs and ages [58,59].

Previous research has demonstrated that students’ self-perceptions regulate, define, and determine their emotions, behaviors, and thinking, which can affect their emotional and social development [50,52,60,61]. Students’ self-perceptions are a foundation for educational and psychosocial development. The self-concept of special needs students is proportionally lower than that of normal students [62]. This implies that they need much more effort and assistance.

H2:

ISNE positively affects self-concept.

H3:

Self-concept positively affects school satisfaction.

2.3. Age and School Level

Based on their research with 599 students from eastern Finland, the authors of [58] demonstrate that students’ ages, as well as the nature and importance of pedagogical support, impact the way in which students see themselves, and processes related to self-concept are still regulated by a personal approach, which differs from one to another. They added that self-concept seems to be more positive in primary school than in secondary school.

H4:

Age moderates the effect of ISNE on self-concept.

H5:

School level moderates the effect of ISNE on self-concept.

2.4. Happiness (or Subjective Well-Being)

To define subjective well-being, we have to refer to two main dimensions: cognitive and affective aspects [63]. The cognitive aspect mainly depends on life satisfaction, but the affective aspect seems to be related to life in general; it can be positive or negative.

As detailed below, subjective psychological well-being is frequently examined by measuring happiness. This dimension depends on many factors but is still related to the school setting [64]. To attain happiness, a high level of satisfaction has to be reached in five main domains: living environment, school, self, friendship, and family [65].

The school setting that determines happiness is a multidimensional construct that depends on academic achievement and the positive relationship between students and teachers [66,67]. Positive personal attributes such as self-concept are also associated with school satisfaction at the individual level because they facilitate a student’s adaptation [68,69].

In this sense, many previous studies have insisted on the positive impact of school satisfaction on students’ well-being and life satisfaction. It is admitted that school satisfaction ameliorates and stimulates life satisfaction [70,71]. In more detail, assistance provided by teachers contributes to the enrichment of students’ competencies and ensures positive development [72,73]. In addition, school adaptation positively impacts students’ perceived well-being and happiness [74], showing higher scores on students’ academic functioning [70,75]. Overall, and based on previous theoretical analysis, the school can be the main context of student development and the primary place promoting life satisfaction and happiness for children.

H6:

School satisfaction positively affects student happiness.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Population

Our constructed theoretical framework for the subjective well-being of disabled students, especially those with physical disabilities, based on inclusive special needs education’s effects on school satisfaction and self-concept, was verified using the data collected via an online questionnaire administered to students in secondary and high schools of different sizes in Saudi Arabia. The biggest challenge during this process was essentially identifying these students and making contact. All students using wheelchairs to move (due to accident or naturally) were asked to participate, as well as those with difficulties seeing, hearing, or speaking.

Two main steps were followed during the data collection procedure: First, the researcher made contact with the school’s directors to explain the objective and opportunity of this project and obtain their agreement. Then, a copy of the questionnaire was sent to the school director, teachers, and supervisors (as previously defined) to administer and send back. Recipients were reminded that the questionnaire was transmitted to the ethical committee of the university to be revised and approved. In all, 403 valid questionnaires were collected during the school years 2022 and 2023. Table 1 details the characteristics and the number of respondents.

Table 1.

Characteristics and number of respondents.

3.2. Measures

The questionnaire (Table A1) was distributed via email, and a link (Google Forms) was sent to the contact person to be administered and sent back. The questionnaire was elaborated based on items identified and collected from the existing literature and revised by the ethical committee. The questionnaire was composed of 54 items addressing issues about inclusive special needs education, school satisfaction, self-perception, and happiness. Respondents were asked to rate their degree of acceptance of each item by scoring the corresponding items along a Likert scale (five-point scale). Table 2 details the variables, dimensions, items, and references for each construct.

To develop this survey, we adopted the seven-step scale as designed by [76]. First, a literature review was elaborated to collect items and define their role in this research. Then, we conducted a focus group to discuss and synthesize the literature. After this, items were selected (as detailed in Table 2) and validated by experts and academics. At this level, the instrument’s validity was verified, because it covered the desired measurements with clear content and appearance. The final step was a cognitive interview to verify if the items and language used could be easily understood, before proceeding to the pilot test. The reliability of this instrument was also examined using the reliability test, which permits evaluation of its internal coherence (as detailed in Table 3).

Table 3.

Dimensions, eigenvalues, and Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 2.

Items and references.

Table 2.

Items and references.

| Variables | Dimensions | Items | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive special needs education (ISNE) | Learning environment (LE) | 3 | [77,78] |

| Guidance provided by teachers (GT) | 4 | ||

| Care structure (CS) | 5 | ||

| Self-concept | Self-fulfillment (SF) | 6 | [79,80] |

| Autonomy (A) | 5 | ||

| Honesty adjustment (HA) | 5 | ||

| Emotional adjustment (EA) | 6 | ||

| School satisfaction | School satisfaction (SS) | 6 | [81] |

| Student subjective well-being (happiness) | School connectedness (SC) | 4 | [82,83] |

| Academic efficacy (AE) | 4 | ||

| Joy of learning (JL) | 4 | ||

| Educational purpose (EP) | 4 |

3.3. Procedure

The first version of the questionnaire was elaborated in English and then translated into Arabic language to be easier and more accessible for different respondents. Then, it was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee at Qassim University to be ethically approved. Once the final version of the questionnaire was available, and after obtaining approval from the committee (ID number 23-59-01), the researcher collected data. At this point, selected participants were asked to join after the informed consent form was signed by participants themselves or their teachers. An information sheet was also provided describing the research, instructions, rights, and main research objectives. To be more flexible, a URL link to the questionnaire was developed using Google Forms, and it was permitted to respond to the questionnaire online. All data were collected anonymously.

3.4. Statistical Techniques

To test different interrelationships, the author opted for the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). This technique analyzes interdependences and different impacts between variables [84]. In this case, it was used to test the mediation effect of self-concept between inclusive special educational needs as the independent variable and school satisfaction as a dependent variable. The moderating effects of the variables age and school level were also examined through the structural equation model (SEM).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

This first step aims to verify the convergent validity measures adopted in the theoretical model according to three tests [85]: factor loadings for latent variables, composite reliability (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE).

The first test, related to factor loadings of different indicators for all latent variables, seems to be significant, with standardized loading values ≥ 0.5. The second test, about composite reliability (CR), shows that indices exceed the required level of 0.7, confirming the good reliability of the constructs used in this research. During the third and final step of AVE, the construct of care structure fails this test with a value of 0.483. The evident proximity to the fixed value of 0.5 necessitates the exclusion of this dimension due to its weak representativeness in this step of analysis. All other constructs are above the minimum required, which allows us to suggest an adequate convergence.

Three dimensions, care structure, autonomy, and educational purpose, were deleted due to their non-significance and low level of internal coherence, as detailed in Table 3.

To establish discriminant validity, the researcher used a heterotrait-monotrait correlation ratio (HTMT), which is preferred to the cross-loading assessments and the commonly used Fornell–Larker criterion [86]. According to the results in Table 4, all HTMT values for the latent variable are inferior to 0.90, except the values for HA adjustment and emotional adjustment.

Table 4.

Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) matrix.

The final step for the examination of the measurement model was the confirmatory factor analysis. Table 5 details the results of CFA, as well as chi-square difference tests. Corresponding results confirm that the hypothesized model (including ISNE, self-concept, school satisfaction, and student subjective well-being) fits the data (χ2 = 391.855; CFI = 0.903; IFI = 0.921; RMSEA = 0.052; SRMR = 0.041), and the chi-square difference test result is significant. According to this analysis, the study supports the idea that the discriminant validity of all key variables is good and can be used in subsequent research.

Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA).

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

The structural model is used to test the hypothesis (direct and indirect effect) according to the coefficient of correlation, R-squared (R2), and fit index. Based on the values in Table 4, all fit indices are acceptable, and the model can be adopted for further analysis. The R-squared for school satisfaction was 0.601, and the corresponding R-squared value for self-concept was 0.489. These values confirm that 60% of the variables used in the model can explain school satisfaction for students with physical disabilities in secondary and high schools in Saudi Arabia. Proportionally, 50% of variables used in the same model can explain the self-concept level.

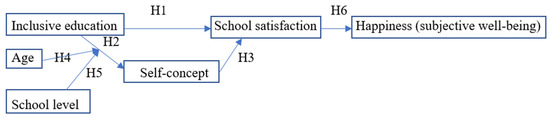

The analysis used t-statistics (t = 5%) to test hypotheses. Figure 1 retraces all different effects, according to which the hypothesis can be verified. Based on the path coefficient generated by the SmartPLS algorithm (Figure 1), direct effects for each variable could be detected and interpreted.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

The learning environment positively and significantly affects adjustment (0.251). The guidance provided by teachers affects self-fulfillment and school satisfaction at the same level (0.224; 0.253).

As can be seen, all indirect effects have increased between ISNE and school satisfaction when self-concept variables are inserted (0.198 becomes 0.592; 0.224 promoted to 0.363; and 0.251 increased to 0.451; with a significant p-value of >5%).

School satisfaction positively determines school connectedness (0.691) and joy of learning (0.324). The impact of school satisfaction on academic efficacy seems negative (−0.387). This effect requires more attention and has to be examined further to identify the reasons.

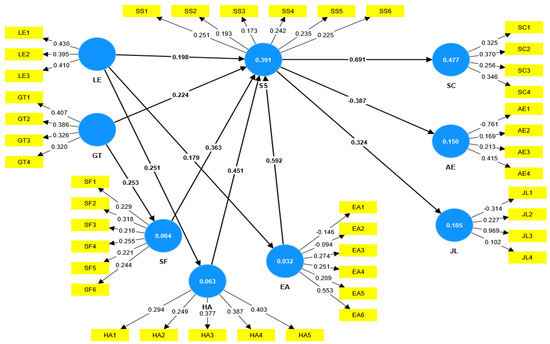

4.3. Mediation Results

In this research, bootstrapping was selected to verify the mediating effect of self-perception, as shown below. Corresponding results are detailed in Table 6. Based on this, the significant mediating effect of self-concept between ISNE and school satisfaction is confirmed. According to the value of the coefficient in terms of direct and indirect effect, the study can conclude the existence of a total mediating effect. This means that the development of a high level of self-concept is required to attain school satisfaction using ISNE practices. Therefore, H1 is confirmed. Figure 2 represents the path coefficient for the variables used in this model. This figure clearly shows the level, the relative importance, and the robustness of direct effects.

Table 6.

Path coefficients.

Figure 2.

The mediating effect of self-concept.

As shown in Table 6, indirect effects are more important than direct ones, confirming the mediation effect. Hypothesis H4 is accepted. At this point, the level of mediation has to be examined. The VAF (variance accounted) was determined. In general, a VAF value of 80% confirms a complete mediation. Table 7 shows the results of the mediation test. As mentioned, self-concept totally mediated the influence of inclusive special needs education on student satisfaction.

Table 7.

Mediation analysis with self-concept.

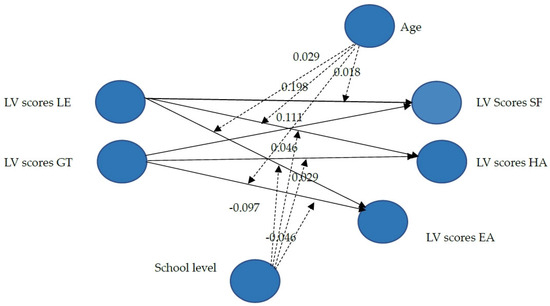

4.4. Moderating Effect: Interaction Results

A stepwise regression method was further adopted to measure and test the impact of age/school level as a moderating variable. The interaction coefficient of age/school level and self-concept on school satisfaction as well as the interaction of this variable and school satisfaction on subjective well-being were calculated. Figure 3 represents different effects between moderator variables on the link between ISNE and self-concept.

Figure 3.

Moderating effects of age and school level.

Both self-concept and inclusive special education needs are centralized before analysis to prevent multicollinearity problems due to the insertion of interaction terms. The corresponding path coefficient of the two models is detailed in Table 8. Model 1 is related to school-level moderation, and model 2 represents the moderating effect of age. The results confirm that school level has a positive and significant effect (β = 0.192, p < 0.001); model 2, which incorporates the interaction of age and self-concept on the basis of the model, seems non-significant. Therefore, H5 is not supported, and only the moderating effect of school satisfaction is accepted.

Table 8.

Path coefficient of the moderator effects.

5. Discussion

In accomplishing our research objectives, the researchers treated two main hypotheses (mediation and moderation) through five hypotheses for testing.

5.1. Supported Hypotheses

H1 was supported (β = 0.246, p ≤ 0.05), which confirms that special needs students are satisfied with the inclusive special needs education method. At this point, it can be concluded that environment learning, care structure, and teacher guidance are all aligned with school satisfaction. In Saudi Arabia, the learning environment is the strongest predictor of a higher level of school satisfaction, along with the guidance provided by teachers. Empirically, only two practices seem to be useful. The research results also support a positive and significant relationship between ISNE and self-concept, as predicted by H2 (β = 0.683, p ≤ 0.05). The value of the coefficient of correlation exceeds 0.5 and can be qualified as a high value. This level can be related to the positive effect of the specific method on special needs students in terms of self-concept. Dealing with “normal” students with the same conditions can help them overcome the negative self-perception related to physical disabilities, and they can be more confident.

Furthermore, two main dimensions of self-concept produced a higher factor loading: self-fulfillment and emotional adjustment, with values of 0.805 and 0.822, respectively. A similar finding was mentioned by [87]. Hypothesis H3 was also supported with a positive effect (β = 0.287, p ≤ 0.05); this value indicates that self-concept can determine school satisfaction, but this influence is still limited. This result leaves open the possibility that other psychological factors exist for the definition of school satisfaction.

The bootstrapping result confirms that self-concept significantly and totally mediates the relationship between ISNE and school satisfaction (H4, β = 0.562, p ≤ 0.05).

The moderating effect of school level is also supported by the effect of ISNE on self-concept.

5.2. Unsupported Hypotheses

The only unsupported hypothesis is H5, which is related to student age as a moderator on the relationship between ISNE and self-concept.

This study was conducted to examine and measure the effects of ISNE on the subjective well-being of special needs students. Among the objectives of this research are: (1) to identify best practices of ISNE; (2) to identify the role of self-concept among special needs education students in achieving school satisfaction; (3) to review this effect based on age and school level; and (4) to test the relationship between the school satisfaction and happiness of special needs students in inclusive education to ameliorate their fulfillment.

6. Conclusions

The main purpose of this research was to investigate and appreciate how the environment in school can impact students’ self-concept, determine school satisfaction, and develop a higher level of subjective well-being (happiness). In this conceptual work, these interrelationships still depend on a mediator effect of self-concept between school environment and school satisfaction and a moderator effect of students’ age and school level.

This research concludes that a positive effect exists between the development of some specific inclusive special educational need practices and the subjective well-being of physically disabled students in Saudi Arabia. This is an indirect effect generated by student self-concept and the attainment of school satisfaction. This idea is in line with [88,89], who insisted on the major role of self-concept in ameliorating school results and satisfaction. For [90], self-concept is the main determent of students’ motivation. Our findings confirm this effect and demonstrate that in the case of inclusive special needs education, the effect of self-concept will depend on students’ age and school level. This result enriches those of [91], who supported the claim that academic self-concept will depend on many factors, such as perception of inclusion and gender. The learning environment is the most critical and the most influential. As one of the three dimensions of ISNE, teaching guidance needs to be applied to ensure and develop a learning environment. In this inclusive system, it is not enough to define practices and teachers’ roles; an integrative and complementary approach has to be developed according to a tryptic approach between schools, students, and teachers. The findings support the claim that a successful ISNE system is based on a cooperative process and good communication among students, teachers [92], and parents [93] at the same time. Added to this, these results sustain a theoretical connection between ISNE, school satisfaction, self-concept, and happiness, with different interaction effects and associations. Self-perception again confirms its critical role in students’ satisfaction, academic performance, and learning process [94], especially for special needs students. These findings highlight the need for a better understanding of the differences and interconnections of these perceptions among students in various age groups and with different pedagogical needs. This information provides new insights for researchers and school professionals alike, with the latter having a particular demand for tools to help them identify students’ individual needs, not only in terms of difficulties but also in skills and abilities to support students.

Based on our findings, it can be said that special needs students are happy to learn in an ISNE program because they receive a great opportunity to learn in a normal setting, and this contributes considerably to the development of a high level of self-concept. This idea is supported by many previous studies, such as [95], who proved that special needs students in an inclusive education setting were happy: they can learn and communicate with teachers and other students. Being in the same conditions and succeeding despite disability is considered a great achievement and a major source of motivation to participate in the community and be productive and active. It can be concluded that self-confidence and self-concept are closely interconnected via this process.

7. Implications

Improving the quality of life and educational inclusion of people with physical, intellectual, and developmental disabilities is an important objective in social policy systems; that is why it is very important to promote various programs and make a correct evaluation in order to offer support to this population category, especially young people and children, and this study more clearly highlights the context in Saudi Arabia.

8. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its great contributions, some limitations still exist. First, respondents were concentrated in the Qassim region, and work needs to be extended to other regions in Saudi Arabia to specify the conditions in each one. The concern of representativeness also remains critical. A large sample is required to specify and test longitudinal relationships of constructs related to human behavior, which is variable and unpredictable. Added to this, our research population was composed of students with physical disabilities only, and further studies can enlarge and diversify the sample to verify if our model is still representative and valuable independently of the nature of the disability marking students as special needs.

Future research should invest in a deeper analysis of ISNE as well as its corresponding practices to define a pragmatical framework that can contribute to happiness and school satisfaction while considering other psychological factors for students in general and students with special needs in particular. However, students with disabilities need more attention, and their satisfaction or their perception of satisfaction is still different [96]. This challenge will also depend on many partners, and it will be interesting to deal with ISNE while moving towards a systemic approach. Technological innovation and artificial intelligence can also be integrated into this approach, and exploring their eventual contributions will be also interesting. Our result can be used to help in developing a new shape of ISEN in Saudi Arabia: how it can be conducted, what is the role of teacher and parents, and what is the appropriate model to achieve school satisfaction and student happiness at the same time. Extending these investigations to identify corresponding mechanisms and practices according to these elements will also be of benefit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.R. and A.A.A.; methodology, W.R.; software, W.R.; validation, W.R.; formal analysis, W.R.; investigation, W.R. and A.A.A. resources; W.R. and A.A.A. data curation, W.R. and A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation; W.R. and A.A.A.; writing—review and editing; W.R. and A.A.A. visualization, W.R.; supervision, W.R. project administration, W.R. and A.A.A.; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the King Salman Center for Disability Research, grant no KSRG-2023-111.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Qassim University Research Ethics Committee. The ethical approval of this study (No: 23-59-01) was obtained from this committee before collecting the data from participants as a prerequisite for conducting this study and all committee requirements have been fulfilled.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in interviews.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data used for this study is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2023-111.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Table A1.

Items.

Table A1.

Items.

| How Satisfied Are You with Each of the Following Things in Your Life? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Neither Dissatisfied nor Satisfied | Satisfied | Very Satisfied | |

| Relationships with other children in your class? | |||||

| Your school marks? | |||||

| Your school experience? | |||||

| Your life as a student? | |||||

| Things you have learned? | |||||

| Your relationship with teachers? | |||||

| Your time in the school? | |||||

| Please indicate your degree of agreement with the following statements | |||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Disagree nor Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I am satisfied with what I am achieving in my life. | |||||

| I depend on other people more than the majority of those I know | |||||

| If I’m feeling down, I find it hard to snap out of it. | |||||

| So far, I have achieved every important goal I have set myself. | |||||

| I am a trustworthy person. | |||||

| In order to do anything, I first need other people’s approval. | |||||

| I consider myself to be a very uptight and highly strung person. | |||||

| I have yet to achieve anything I consider to be important in my life. | |||||

| I am a man/woman of my word. | |||||

| I find it hard to embark on anything without other people’s support. | |||||

| I am more sensitive than the majority of people. | |||||

| I have always overcome any difficulties I have encountered in my life. | |||||

| I am a decent, honest person. | |||||

| When making a decision, I depend too much on other people’s opinions. | |||||

| If I could start my life over again, I would not change very much. | |||||

| I try not to do anything that might hurt others. | |||||

| I find it difficult to take decisions on my own. | |||||

| I am an emotionally strong person. | |||||

| I feel proud of how I am managing my life. | |||||

| I suffer too much when something goes wrong. | |||||

| My promises are sacred. | |||||

| I know how to look after myself so as not to suffer. | |||||

| I get excited about learning new things in class. | |||||

| I feel like I belong at my school. | |||||

| I feel like the things I do at school are important. | |||||

| I am a successful student. | |||||

| I am really interested in the things I am doing at school. | |||||

| I can really be myself at school. | |||||

| I think school matters and should be taken seriously. | |||||

| I do good work at school. | |||||

| I enjoy working on class projects and assignments. | |||||

| I feel like people at my school care about me. | |||||

| I feel it is important to do well in my classes. | |||||

| I do well on my class assignments. | |||||

| I feel happy when I am working and learning at school. | |||||

| I am treated with respect at my school. | |||||

| I believe things I learn at school will help me in my life. | |||||

| I get good grades in my classes. | |||||

| I feel that I’m in a stimulating learning environment. | |||||

| I feel that I’m in secure learning environment. | |||||

| I feel that I’m in participatory learning environment. | |||||

| I get a guidance mentor/regularly assigned teacher. | |||||

| I get individual guidance in lessons. | |||||

| I get customized program. | |||||

| Individual education plan. | |||||

| My parents are partners in my guidance. | |||||

| I get functioning of care coordinator. | |||||

| I get functioning of care team. | |||||

| I get interagency collaboration. | |||||

| I get harmonization of internal and external care. | |||||

References

- Bwachele, V.W.; Chong, Y.; Krishnapillai, G. Perceived service quality and student satisfaction in higher learning institutions in Tanzania. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teniell, T.L.; Archibald, G.C.; Jach, E.A. Well-being and student–faculty interactions in higher education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Velde, S.; Buffel, V.; Bracke, P. The COVID-19 International Student Well-being Study. Scand. J. Public Health 2022, 49, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priscilla, P.; Mather, R.; Peter, C.; Bhat, C.; Suniti, J.; Justine, K. University Student Well-Being during COVID-19: The Role of Psychological Capital and Coping Strategies. Prof. Couns. 2021, 11, 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gashi, A.; Mojsoska-Blazevski, N. The Determinants of Students’ Well-being in Secondary Vocational Schools in Kosovo and Macedonia. Eur. J. Educ. 2016, 51, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, N.S.; Mondragon, N.I.; Santamaria, M.D.; Gorrotxategi, M.P. The well-being of children with special needs during the COVID-19 lockdown: Academic, emotional, social and physical aspects. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 37, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldan, J.; Nusser, L.; Gebel, M. School-related Subjective Well-being of Children with and without Special Educational Needs in Inclusive Classrooms. Child Ind. Res. 2022, 15, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wang, C.; Tang, W.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y. Emotional Intelligence and Well-Being of Special Education Teachers in China: The Mediating Role of Work-Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 696561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; Qoraboyev, I.; Gimranova, D. Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: New empirical and conceptual insights. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; O’Neill, S.; Strnadová, I. What Constitutes Student Well-Being: A Scoping Review of Students’ Perspectives. Child Ind. Res. 2023, 16, 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferran, C.; Sergiu, B.; Irma, B.; Mònica, G.; Adrian, H. School Satisfaction Among Adolescents: Testing Different Indicators for its Measurement and its Relationship with Overall Life Satisfaction and Subjective Well-Being in Romania and Spain. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 111, 665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M.Y.; Shaheen, A.M.; Nassar, O.S.; Arabiat, D. Predictors of school satisfaction among adolescents in Jordan: A cross-sectional study exploring the role of school-related variables and student demographics. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2019, 12, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Santos, T.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Developmental assets and positive youth development: An examination of gender differences in Spain. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2021, 26, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyarini, A.D.; Putri, Y.H.; Tyas, F.P.S. Satisfaction with Inclusive Education Services and its Relationship with Father and Mother Involvement. J. Fam. Sci. 2021, 06, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, T.N.; Prasetya, M.N. Dapatkah kepemimpinan kepala sekolah, motivasi guru dan kualitas pelayanan pendidikan mempengharuhi kepuasan orang tua siswa. EduTech J. Ilmu Pendidik. Dan Ilmu Sos. 2020, 6, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, M.A. Evolution of the Human Brain and Intelligence: From Matter to Mind. In Handbook of Intelligence: Evolutionary Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, M. Special Education: Contemporary Perspectives for School Professionals; Pearson Education Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.A. Problems in comparative research: The example of omnivorousness. Poetics 2005, 33, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supiah, S. Komitmen Dan Peranan Guru Dalam Pelaksanaan Pendekatanpendidikan Inklusif Di Malaysia; Jabatan Pendidikan Khas, Kementerian Pelajaran: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Nazrin, B.; Osman, Z.; Raju, V. Mediating Effect of Satisfaction on the Relationship between Teamwork and Employees Engagement in Malaysian Airlines Sector in Malaysia Mohd Nazrin Burhanuddin. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2020, 7, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- César, M.; Ainscow, M. Inclusive education ten years after Salamanca: Setting the agenda. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2006, 21, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Murnie, H. Perlaksanaan Program Inklusif bagi Pelajar-pelajar Pendidikan Khas Bermasalah Pembelajaran di Program Integrasi. Master’s Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.B.; Doorlag, D.H. Teaching Special Students in General Education Classrooms, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heiman, J.R. Orgasmic disorders in women. In Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy; Leiblum, S.R., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kucukera, S.; Tekinarslanb, I.C. Comparison of the Self-Concepts, Social Skills, Problem Behaviors, and Loneliness Levels of Students with Special Needs in Inclusive Classrooms. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2015, 15, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, N.A.; Tahar, M.M. The Effects of Inclusive Education on the Self-Concept of Students with Special Educational Needs. J. ICSAR 2017, 1, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, F. El bienestar personal: Su investigación en la infancia y adolescencia. Encuentros Psicol. Soc. 2010, 5, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lissa, C.J.; Keizer, R.; Van Lier, P.A.C.; Meeus, W.H.J.; Branje, S. The role of fathers’ versus mothers’ parenting in emotion-regulation development from mid–late adolescence: Disentangling between-family differences from within-family effects. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhesh, A. The concept of inclusive education from the point of view of academics specialising in special education at Saudi universities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhesh, A. Full exclusion during COVID-19: Saudi Deaf education is an example. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpakjian, C.Z.; Haapala, H.J.; Ernst, S.D.; Orians, B.R.; Barber, M.L.; Mulenga, L.; Jay, G.M. Development and pilot test of a pregnancy decision making tool for women with physical disabilities. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. What Really Works in Special and Inclusive Education: Using Evidence-Based Teaching Strategies, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, C.S.; Wüthrich, S.; Büchi, J.S.; Sharma, U. The concerns about inclusive education scale: Dimensionality, factor structure, and development of a short-form version (CIES-SF). Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 111, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Sandill, A. Developing Inclusive Education Systems: The Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzer, C.; Weber, M. Region of Western Europe (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland). In The International Handbook of Positive Psychology: A Global Perspective on the Science of Positive Human Existence; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 185–221. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.A.; Maupin, A.N. School satisfaction and children’s positive school adjustment. In Handbook of Positive Psychology in the Schools; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Flook, L.; Cook-Harvey, C.; Barron, B.; Osher, D. Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2020, 24, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.; Hills, K.; Jiang, X.; Long, R.; Kelly, R.; Lyons, M. Schooling and Children’s Subjective Well-Being. In Handbook of Child Well-Being; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Suldo, S.M.; Gormley, M.J.; DuPaul, G.J.; Anderson-Butcher, D. The impact of school mental health on student and school-level academic outcomes: Current status of the research and future directions. Sch. Ment. Health 2014, 6, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülsün, I.; Olli-Pekka, M.; Akie, Y.; Hannu, S. Exploring the role of teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education, their self-efficacy, and collective efficacy in behaviour management in teacher behaviour. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, D.; Goutas, T.; Tsigilis, N.; Michaelidou, V.; Gregoriadis, A.; Charalambous, V.; Vrasidas, C. Effects of the Universal Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports on Collective Teacher Efficacy. Psychol. Sch. 2023, 60, 3188–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkeit, J.; Anne, H.; Antje, E.; Michel, K.; Nadine, S. Effects of special educational needs and socioeconomic status on academic achievement. Separate or confounded? Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 113, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Huebner, E.S. A cross-cultural study of the levels and correlates of life satisfaction among adolescents. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, J.H. Social Relations and School Life Satisfaction in South Korea. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Kahng, S.K.; Kim, H. The trajectory of life satisfaction and its associated factors among adolescents in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work. Dev. 2017, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.; Park, B.J. How do leisure activities impact leisure domain and life domain satisfaction and subjective well-being? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, C.; Huebner, E.S. Life satisfaction reports of gfted middle-school children. Sch. Psychol. Q 1998, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E.; Roche, T.; Wilson, E.; Zhang, J.; McKenzie, J.W. The success, satisfaction and experiences of international students in an immersive block model. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2024, 21, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topps, A.K.; Jiang, X. Exploring the Moderating Role of Ethnic Identity in the Relation Between Peer Stress and Life Satisfaction among Adolescents. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 27, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joët, G.; Usher, E.L.; Bressoux, P. Sources of self-efficacy: An investigation of elementary school students in France. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 103, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (Ed.) Psychological Modeling: Conflicting Theories; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paananen, M.; Aro, T.; Viholainen, H.; Koponen, T.; Tolvanen, A.; Westerholm, J.; Aro, M. Self-Regulatory Efficacy and Sources of Efficacy in Elementary School Pupils: Self-Regulatory Experiences in Population Sample and Pupils with Attention and Executive Function Difficulties. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2019, 70, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.; Padilla, A.; Wieman, R.; Tan, P. A disability studies in mathematics education review of intellectual disabilities: Directions for future inquiry and practice. J. Math. Behav. 2019, 54, 100672. [Google Scholar]

- Alfalih, A.; Ragmoun, W. Drivers of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Orientation for Students at Business School in Saudi Arabia. J. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ragmoun, W. A descriptive analysis of entrepreneurial female career success determinants on Saudi Arabia along entrepreneurial process. Arch. Bus. Res. 2019, 7, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, R.; Helakorpi, S. Lasten ja Nuorten Hyvinvointi: Kouluterveyskysely 2019. Available online: https://www.julkari.fi/handle/10024/138562 (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Ragmoun, W. Determinants of entrepreneurial intention: A comparative analysis. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 25, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikävalko, M.; Sointu, E.; Lambert, M.C.; Viljaranta, J. Students’ self-efficacy in self-regulation together with behavioral and emotional strengths: Investigating their self-perceptions. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 38, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spörer, N.; Lenkeit, J.; Stefanie, B.; Anne, H.; Antje, E.; Michel, K. Students’ perspective on inclusion: Relations of attitudes towards inclusive education and self-perceptions of peer relations. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 103, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, F. Understanding White Privilege: Creating Pathways to Authentic Relationships Across Race; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sternke, J. Self-Concept and Self-Esteem in Adolescents with Learning Disabilities, American Psychological Association, stb ed.; University of Wisconsin: : Madison, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well–being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Kern, M.L.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Hattie, J.; Waters, L. What Schools Need to Know About Fostering School Belonging: A Meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S. Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, N.; Aunola, K.; Vuori, J.; Nurmi, J.E. The role of peer groups in adolescents’ educational expectations and adjustment. J Youth Adolesc. 2007, 36, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, N.; Nurmi, J.E.; Aunola, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Peer group homogeneity in adolescents’ school adjustment varies according to peer group type and gender. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azpiazu, I.M.; Dragovic, N.; Pera, M.S.; Fails, J.A. Online searching and learning: YUM and other search tools for children and teachers. Inf. Retr. J. 2017, 20, 524–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Ramos-Díaz, E.; Ros, I.; Fernández-Zabala, A.; Revuelta, L. Bienestar subjetivo en la adolescencia: El papel de la resiliencia, el autoconcepto y el apoyo social percibido. Suma Psicol. 2016, 23, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, R.; Huebner, E.S. Characteristics of adolescents who report very high life satisfaction. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, P.C.; Benson, P.L.; Leffert, N.; Blyth, D.A. Contribution of developmental assets to the prediction of thriving among adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2000, 4, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Ríos, M.; Antolín, L.; Parra, Á.; Hernando, Á.; Pertegal, M. Ángel Más allá del déficit: Construyendo un modelo de desarrollo positivo adolescente. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2010, 33, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D.; Estévez, E.; Murgui, S.; Musitu, G. Relación entre el clima familiar y el clima escolar: El rol de la empatía, la actitudhacia la autoridad y la conducta violenta en la adolescencia. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. 2009, 9, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Taveira, M.D.C.; Sheu, H.-B.; Singley, D. Social cognitive predictors of academic adjustment and life satisfaction in Portuguese college students: A longitudinal analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, F.P.; Clavero, F.H. Influencia de la felicidad en el rendimiento académico en primaria: Importancia de las variable sociodemográficas en un contexto pluricultura. REOP Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 2019, 30, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Artino, A.R.; La Rochelle, J.S.; Dezee, K.J.; Gehlbach, H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Med. Teach. 2014, 36, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiernan, B.; Casserly, A.M.; Maguire, G. Towards inclusive education: Instructional practices to meet the needs of pupils with special educational needs in multi-grade settings. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Bij, T.; Geijsel, F.P.; Garst, G.J.A.; Ten Dam, G.T.M. Modelling inclusive special needs education: Insights from Dutch secondary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2016, 31, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, A.; Zulaika, L. Relationships between physical education classes and the enhancement of fifth grade pupils’ self-concept. Percept. Mot. Skills 2000, 91, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, E.; Madariaga, J.M.; Axpe, I.; Goñi, A. Structure of the personal self-concept (PSC) questionnaire. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2011, 11, 509–522. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, E.; Boerchi, D.; Magnano, P.; Patrizi, P. High-School Satisfaction Scale (H-Sat Scale): Evaluation of Contextual Satisfaction in Relation to High-School Students’ Life Satisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, T.L.; Long, A.C.J.; Cook, C.R. Assessing adolescents’ positive psychological functioning at school: Development and validation of the Student Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire. Sch. Psychol. Q 2015, 30, 534–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, T.L. Psychometrics of the Revised College Student Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 33, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Chi, M.; Wang, W. The Impact of Information Technology Capabilities of Manufacturing Enterprises on Innovation Performance: Evidences from SEM and fsQCA. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Editorial-Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan 2014, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. In Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 361–381. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, C.; Rufín, R. Transparency policy and students’ satisfaction and trust. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2015, 9, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, I. Non-Academic Self Concept and Academic Achievement: The Indirect Effect Mediated By Academic Self Concept. Res. J. Organ. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2014, 3, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Doménech-Betoret, F.; Abellán-Roselló, L.; Gómez-Artiga, A. Self-Efficacy, Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement: The Mediator Role of Students’ Expectancy-Value Beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulakow, S. Academic self-concept and achievement motivation among adolescent students in different learning environments: Does competence-support matter? Learn. Motiv. 2000, 70, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, J.M.; Knickenberg, M.; Trygger, M. Academic self-concept, perceptions of inclusion, special needs and gender: Evidence from inclusive classes in Sweden. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 37, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniqi, V.; Zdravkova, K.; Dalipi, F. Impact of Assistive Technologies to Inclusive Education and Independent Life of Down Syndrome Persons: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battal, Z.M.B. Parental Satisfaction with special education service for students with learning disabilities: Riyadh. J. Educ. Sci. 2013, 26, 663. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, J. Effortful control, executive functions, and education: Bringing self-regulatory and social-emotional competencies to the table. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K.; Mahmud, W.W. Pelaksanaan Program Pendidikan Inklusif Murid Autistik Di Sebuah Sekolah Rendah: Satu Kajian Kes. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Teacher Education; Join Conference UPI & UPS, Bandung, Indonesia, 8–10 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, K.; Bray, M.A.; Kehle, T.J.; Theodore, L.A.; Gelbar, N.W. Promoting happiness and life satisfaction in school children. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2011, 26, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).