Abstract

This qualitative study explores the implementation and adoption process of the use of digital devices and tools in teaching and learning before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. Using Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory as a framework, the study examines the adoption and adaptation of digital devices by in-service secondary mathematics teachers (n = 62) and the teachers’ perceptions of and preferences for instructional modalities. The findings suggest that, despite the increased reliance on digital devices during the pandemic, there is a lower likelihood of them being used in face-to-face classrooms in developing countries, such as Nepal. The adoption of online learning had not yet reached the adoption stage, even after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, online learning was not widely adopted by teachers in developing countries societies. The study also provides important insights into the challenges of and opportunities provided by using digital devices in post-COVID-19 classrooms, and its implications for policymakers and educators in Nepal.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a worldwide transition from face-to-face classes to online learning. This shift has brought about a significant transformation in education, with e-learning experiencing particular growth. E-learning involves delivering lessons through various online and digital platforms, as noted by Hodgen et al. [1,2]. Digital resources are increasingly being used in online classes to aid students when lockdowns are necessary, as pointed out by Videla et al. [3]. This situation has provided teachers with an opportunity to use digital tools, even if they had never done so before, and has led to unexpected benefits for digital natives [4]. Schools with an established infrastructure for online learning have been better equipped to transition to remote instruction than those without [1].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers have been able to acquire new knowledge and digital skills in online teaching, enabling them to facilitate student development, especially in developing countries such as Nepal [5]. The skills that teachers have acquired in online teaching during the pandemic may lead to the development of strong digital skills and technological capacities, particularly in areas with connectivity [6]. Furthermore, the use of digital resources in the classroom has opened up opportunities to introduce students to digital technology and for the continuous use of social media for networking and advancing novel practices [7].

Zhao and Watterston [8] predicted that education would change after COVID-19 to incorporate both synchronous and asynchronous learning in all subjects, including mathematics. Prior research has provided insights into how mathematics teachers use digital resources for online learning during the pandemic [3,9,10,11]. However, the key issue for practitioners is how to make informed decisions about the use of digital resources after the pandemic to promote their effective utilization in teaching. Digital technologies have become popular due to their scalability and cost effectiveness in education. With the shift away from traditional classrooms, researchers, practitioners, and policy makers are questioning whether the use of digital tools for online teaching will continue post-pandemic and how it will impact classroom teaching worldwide [12]. The use of online teaching with digital resources has become an innovative new option for mathematics teachers in Nepal. Rogers’ theory [13] suggests that the adoption of new approaches depends on individuals’ decisions to continue using new ideas. The government of Nepal has implemented Teachers Professional Development (TPD) training to equip in-service teachers with essential ICT skills, and most teachers complete this training after serving for over a decade [14]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the TPD was intensified, as reported by the Ministry of Education Science and Technology. However, despite the acquisition of relevant digital devices and tools during the training and their potential utility in online teaching during COVID-19, the implementation of these skills in face-to-face mathematics classrooms was not observed in most cases. This highlights a significant gap between the acquisition of digital skills and their transfer and implementation by teachers [15].

The possibilities for the continued use of digital resources in the mathematics classroom after COVID-19 remain relatively understudied. While virtual classes and social media platforms, such as Facebook Messenger, Google Classroom, Teams for Virtual Classes, Google Docs, and WeChat, were novel resources for Nepali mathematics teachers, they have quickly become essential tools for delivering quality education in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite their potential, little research has investigated the continued use of these tools post-COVID-19. Future research should explore the viability of these digital resources in mathematics education and identify the barriers to their integration, in order to enhance the quality of education in Nepal.

To address this gap, a qualitative study was conducted among school mathematics teachers in Nepal to understand the determinants of the perceived usefulness and ease of use of digital devices and tools, as well as teachers’ attitudes towards continuing to use such tools in the post-COVID-19 context. The aim of this article is to explore the uses of digital resources by teachers before the pandemic or during COVID-19 as they made the transition from a face-to-face classroom system to an online mathematics teaching. The findings have important implications for policy makers, teachers’ educators, and educational administrators regarding the integration of digital technology in mathematics education and its implementation in classroom teaching. This study is particularly relevant to developing countries. The research questions guiding the study were: (1) what digital resources did mathematics teachers use in online teaching before and during COVID-19 in Nepal? and (2) how did mathematics teachers use these digital resources after COVID-19 in face-to-face classroom teaching in Nepal?

2. Context of the Study

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional face-to-face instruction was the norm for teaching and learning mathematics in Nepal, with limited use of technology. In Nepal, where education is mostly limited to traditional classroom settings with rote learning, memorization, and paper-and-pencil tests, policymakers and planners should consider blended learning approaches to transform the teaching and learning processes. Critical thinking is necessary for internalizing the curriculum contents, but it is often discouraged, and textbooks are the main sources of learning materials. Learning should involve more than just listening to lectures and completing assignments [16]. However, the pandemic resulted in a full lockdown and school closures, which forced a transition to online learning, as was the case in many other countries. This shift was challenging for both students and teachers and presented multidimensional and complicated challenges. The need for innovative teaching methods and digital resources has become more critical.

In response to school closures due to COVID-19, schools adopted various approaches to reach their students, with many opting for online and distance learning through digital resources and classic technologies such as radio and TV [5]. However, this shift required teachers to develop new skills in designing online pedagogy, integrating digital resources, and utilizing digital tools [17]. To teach math online, teachers require basic computer skills and access to digital resources [18], but effective online math teaching may require specialized digital resources and expertise [19]. Although awareness of digital tools has increased among math teachers, it remains unclear to what extent they used these resources during COVID-19 and how they plan to use them in post-COVID classrooms [10,20].

3. Understanding the Technological Limitations of Online Learning

Online learning is plagued by several limitations in developing countries, including technological issues and infrastructural deficits that result in low bandwidth, inadequate internet connectivity, and a scarcity of electronic devices such as laptops and smartphones; these issues limit students’ access to online classes. UNICEF [21] reported that 463 million students worldwide were unable to participate in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic due to a lack of internet connectivity, devices, or both. Additionally, a lack of interaction and involvement results in students becoming disengaged, demotivated, and lonely, leading to a decreased likelihood of them engaging with online coursework and an increased likelihood of dropping out of online courses [22]. Inadequate support services, such as a lack of sufficient support for students seeking assistance with their online schoolwork, constitute another significant challenge faced by many countries. Some students with learning difficulties or linguistic barriers may not have access to appropriate support resources in some countries. Another issue is that teachers lack the expertise or training required to design and deliver effective online learning experiences. The OECD [23] reported that teachers in many countries lack the skills required to design and deliver good online courses, which makes assessing student learning and evaluating their performance difficult. Recent studies have shown that students’ perceived ease of use does not significantly impact their intention to use new technologies. Furthermore, e-learning has been evaluated based on students’ comprehension of the course material, and research indicates that e-learning may hinder students’ ability to understand the content compared to traditional teaching methods [24] and may contribute to a lack of a sense of belonging [24]. Das [25] stated that students may become distracted during online learning due to difficulties in understanding numerical applications and a lack of engaging activities, leading to reduced concentration during live sessions. In the contexts of developing countries, the most significant hurdle encountered by teachers pertains to their insufficient proficiency in information and communication technology (ICT) [26]. However, in a recent study by [27]), it was observed that both teachers and students identified the flexibility of online teaching and learning as its most significant advantage, owing to its accessibility and effective communication methods. However, the sudden implementation of eLearning may have implications for users’ mental health and socialization, resulting in negative outcomes. To alleviate these challenges, the authors propose the implementation of a hybrid flexible (HyFlex) approach that considers the characteristics of the courses and is utilized by educators in academic institutions. This approach can provide the best of both worlds, allowing for the benefits of online learning while also providing opportunities for in-person interaction and socialization, leading to a more well-rounded and effective educational experience.

4. Conceptual Framework: Diffusion of Digital Resources in Mathematics Teaching

The dissemination of technological innovation is a fundamental focus of innovation diffusion research. Researchers have investigated technological innovation through many lenses, such as the formation of technical innovation systems, the mechanics of operation, and the promotion of innovative potential. Given that the ultimate goal of corporate innovation is the successful spreading of new technologies, there is a growing emphasis on investigating the process of technological innovation diffusion as well as the factors that influence it [27,28].

We focused on Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory (DIT) to understand the implementation of and conformation to new ideas in the field of education due to its wider range of innovation adaptation characteristics and processes, including the knowledge, persuasion, decision, execution (implementation), and adoption stages [29]. Roger’s diffusion theory of innovation is an empirically well-established theoretical framework that conceptualizes the five stages of the innovation adaptation process [30]. This theory has been used to elucidate the adaptation and acceptance of online learning in teaching and learning and the adoptation of online proctored exams [28].

The adoption and continuous use of digital resources and devices by mathematics teachers in online classes involve various stages of adaptation. According to Rogers’ (1995) theory of the diffusion of innovation, there are five stages involved in this process: awareness, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation. A few studies have shown that mathematics teachers in Nepal have already used digital tools to communicate with students during the COVID-19 pandemic [10,31]. The Government of Nepal has already made the decision to incorporate information and communication technology (ICT) into the educational system by creating online classrooms for all levels of education during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is inferred that teachers have been made aware of the existence of this technology for classroom instruction. Furthermore, it is plausible that these teachers have been convinced to adopt this technology in their mathematics classrooms (persuasion) and that they have ultimately reached the decision to embrace this innovative approach to teaching, as there may not have been any alternative options available to them (decision). Nonetheless, as Grgurovic [32] observes, the last two phases, which are critical for the enduring utilization of digital tools and materials beyond the pandemic, have not been thoroughly researched in the context of online education, particularly in developing nations. These phases can shed light on whether the integration of digital resources into math education is a gradual process or if it is rapidly embraced and consistently employed by instructors. These stages can help us to determine whether the adoption of digital resources in mathematics teaching takes time or is quickly embraced and consistently used by teachers. In this case, mathematics teachers who have tested digital resources and engaged in online learning are considered innovators. The analysis of interviews presented in the findings section utilizes these two stages.

5. The Implementation Stage

The diffusion theory implementation stage entails the process of putting the innovation into reality and making it widely available. Those who are exposed to innovation, meanwhile, must have a fundamental understanding of what it is and how it works [33]. People are more likely to maintain an attitude than to frequently change their minds [34]. This change is therefore not seen as either favorable or bad. When regarded in this context, implementation helps and supports learners’ efforts to rearrange and modify their schemata. It is apparent that, for students to fully benefit from an online environment, they must engage with it [35]. However, due to various circumstances, it may be difficult for students to engage with blended learning [36]. In most circumstances, once a decision to adopt a product has been made, the consumer will use it. This is the point at which the adopter decides whether or not the innovation or new ideas will be beneficial to them. They may also look for additional information to help them use the product or to better understand it in context. An innovation, on the other hand, brings newness, and “some degree of uncertainty is involved in diffusion” [13] (p. 6). An individual (teachers) in a social system (class) can face a number of issues. Thus, the implementor (teachers) may require technical assistance from change agents and others. A supportive environment, ease of use, and usefulness could be the major factors for acceptance [37]. When individuals doubt the ease and usefulness of the technology (e.g., due to technology anxiety), they might reject it entirely [13]. Rogers (2003) also clarified the concept of “adoption” as “the process of using an existing idea continuously” [13] (p. 181). The greater the perceived ease and usefulness of the technology is, the faster an innovation is adopted and entrenched. Digital resources in the form of computer technology are more accessible since they are tools with many possible prospects and applications.

The compatibility of an innovation with prevailing systems and practices is one of the primary factors that influence its successful implementation. Studies have demonstrated that innovations that align with existing systems are more likely to be embraced and put into effect [13] In addition, the complexity of the innovation and its ease of use are important factors in determining its success. Innovations that are simple to use and understand are more likely to be implemented successfully [29]. Another important factor is the availability of resources, including funding and support from stakeholders. Innovations that have adequate funding and support are more likely to be implemented successfully [38]. The involvement of stakeholders, such as end-users, in the implementation process has also been shown to be important in ensuring success [39]. Research has shown that the involvement of leaders and managers in the implementation process can help to overcome resistance to change and increase the likelihood of success [40]. However, despite the potential benefits of innovation implementation, there are many barriers that can hinder the process. One of the most common barriers is resistance to change. Research has shown that people are often resistant to change and may be reluctant to adopt new ideas and technologies [38]. This resistance can be particularly strong in organizations with entrenched cultures and traditions. There are also many barriers that can hinder the process, including a lack of resources. Future research should focus on identifying strategies for overcoming these barriers and increasing the likelihood of successful implementation.

6. The Continuation of Use of Digital Resources (Confirmation Stage)

Confirmation is the final stage of the process, in which individuals assess the effects of adopting the innovation and seek confirmation from other decision makers that the decision to embrace the innovation was correct [13]. The confirmation stage was explored in this study since all the mathematics teachers are professional teachers who conducted online classes to reach out to students and used digital resources to continue their teaching. Even if the decision had already been made by schools, individuals might have been exposed to conflicting cues regarding the innovation [13], leading them to reject it. Some individuals, on the other hand, may avoid conflicting cues and favor only supportive ones that affirm their decisions. As a result, during the confirmation stage, attitudes become even more important. One of the key factors affecting the confirmation stage is the perceived relative advantages of the innovation. Research has shown that innovations that are perceived to offer significant advantages over existing systems and practices are more likely to be confirmed [13]. Depending on the level of support for the invention and the individual’s attitude, delayed adoption or even discontinuance might occur during this stage [13]. Another important factor is the complexity of the innovation and its ease of use. Innovations that are easy to use and understand are more likely to be confirmed [41]. The involvement of stakeholders in the confirmation process is also important. Stakeholders who are involved in the evaluation and feedback process are more likely to continue using the innovation [39].

Despite the potential benefits of innovations, there are many barriers that can hinder the confirmation stage. One of the most common barriers is a lack of a perceived relative advantage. If stakeholders do not perceive the innovation as offering significant advantages over existing systems and practices, they may be less likely to confirm it (Rogers, 2003). Another common barrier is a lack of compatibility with existing systems and practices. If the innovation is not compatible with existing systems and practices, stakeholders may be reluctant to continue using it [41]. In addition, the complexity of the innovation and the difficulty of use can be barriers to confirmation [41]. Table 1 represents the difference between the implementation and confirmation stages; the relationship between them is not strictly linear and they overlap and occur simultaneously in practice.

Table 1.

The difference between the implementation and confirmation stages.

7. Methods

The study utilized a qualitative design and gathered data through structured interviews with mathematics teachers in two districts. We conducted interviews through Google Meet and face-to-face modes. A total of 90 mathematics teachers were purposefully selected, but only 62 (56 males and 6 females) provided complete answers to our questions, making them the actual sample size for the study. All participants were chosen from areas with internet access and reported having Android mobile devices, with 47 teachers also owning laptops before the pandemic. This sample displayed a significant under-representation of female participants, likely due to the scarcity of women in the teaching profession in Nepal, as noted by Shakya [42]. The teachers came from 62 schools across 2 districts and were all in-service teachers working in community schools in Nepal. All participants in this study possessed a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in either mathematics education or science education. The age range of the respondents spanned from 25 to 45 years. Due to the large sample size, the researcher enlisted the support of MPhil scholars from Nepal Open University (NOU) and provided them with instructions on the instruments and data collection techniques. All interviews were recorded during data collection and transcribed in Nepali language. The transcribed data were then translated into English for analysis. The researchers coded the data using Atlas.ti software based on the interview guidelines.

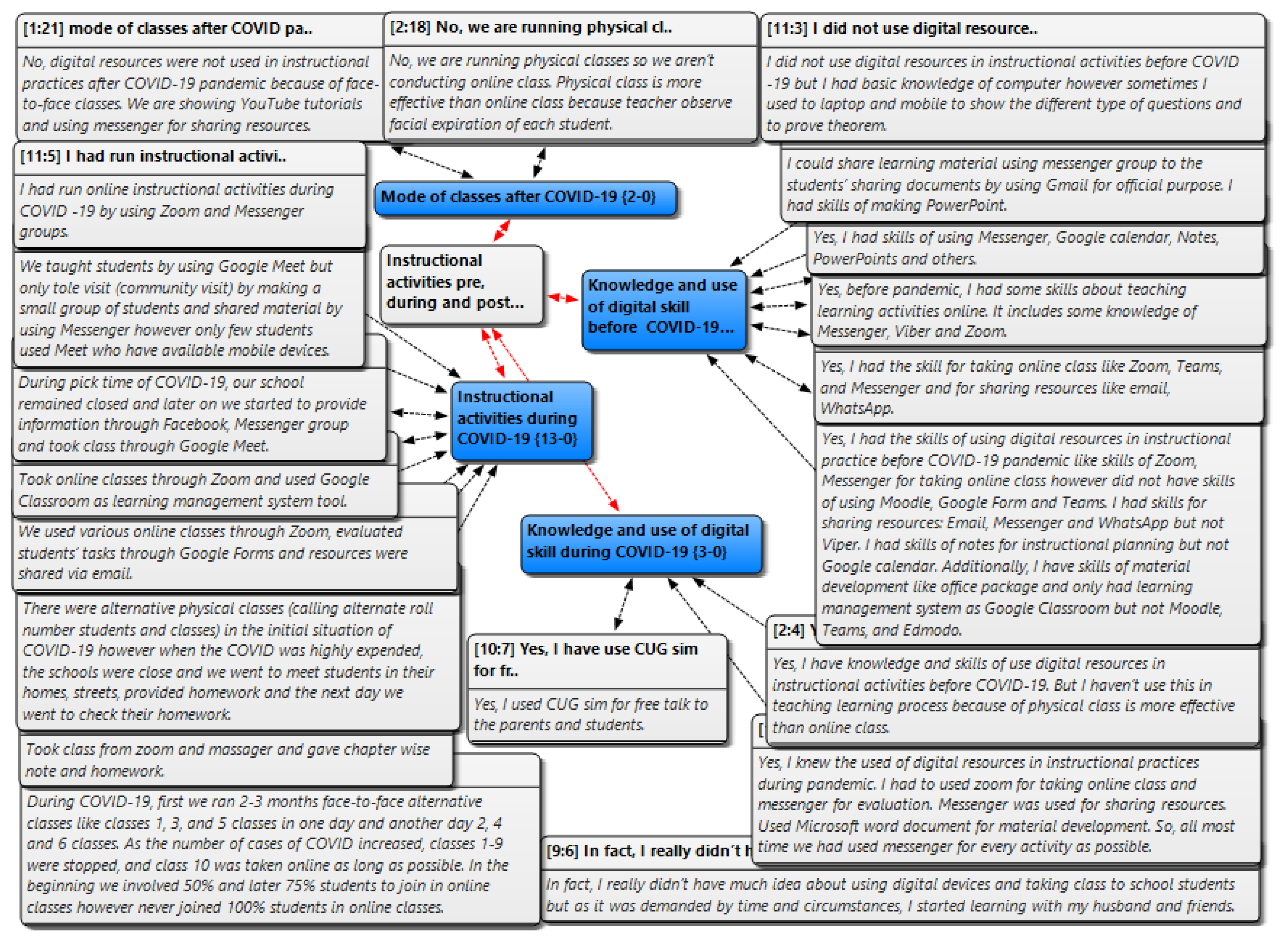

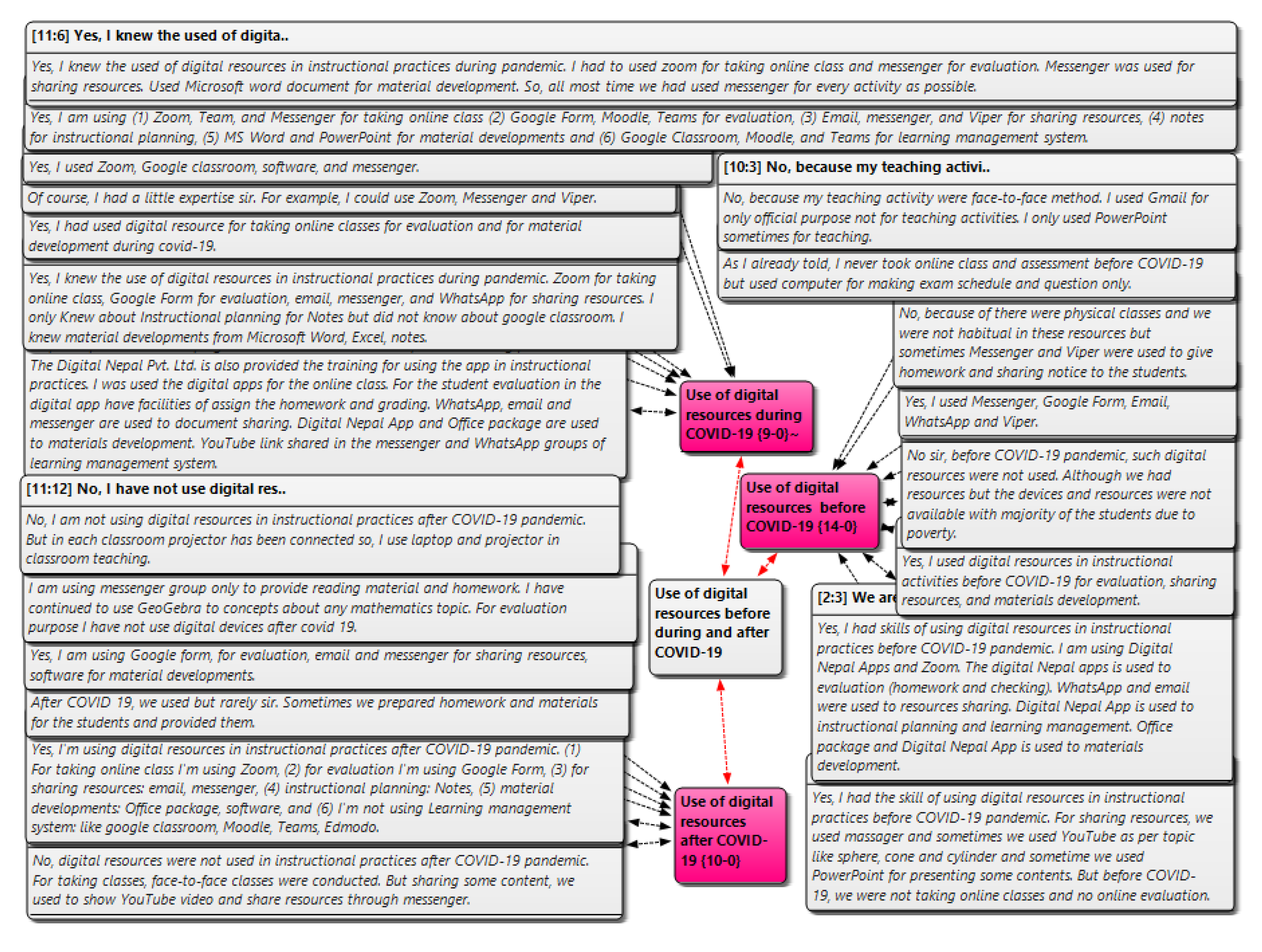

To ensure ethical standards were met, informed consent was obtained from the students via email responses. Deductive analysis was used to confirm that the data arrangement was consistent with the expected pattern of the two stages of the diffusion theory of innovation and in accordance with the participants’ responses. Thus, the two stages of the diffusion theory of innovation were taken into consideration when interpreting the interview responses. The transcripts were perused to gain a broad understanding of the results, and relevant excerpts were allocated to the two phases of the decision-making procedure, as proposed by Creswell [43]. Throughout this process, the ideas were constantly compared both within and across stages to reduce overlapping and draw clear conclusions. Figure 1 and Figure 2 depict the interview questions and answers regarding instructional activities and the use of digital resources in mathematics teaching in high schools in Nepal before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, and the analysis is presented under separate subheadings.

Figure 1.

Instructional activities of mathematics teachers before, during, and after COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2.

Use of digital resources before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

8. Findings

Our findings are organized according to three main pre-determined themes, i.e., the implementation and confirmation stages before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

9. Implementation and Confirmation of Digital Resources before COVID-19

Teachers lacked experience and knowledge of digital devices before COVID-19 and had no prior experience with online classes or evaluations. They did not feel it was necessary in face-to-face classrooms and did not realize the importance of digital resources in teaching. For example, a teacher from Kaski District said:

“We didn’t have any experience with online classes or evaluations. We didn’t have any practice conducting classes or evaluations online.”

The knowledge and skills required to use digital resources were crucial for their implementation. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly all teachers had an Android mobile phone, and 47 of them owned a laptop. Teachers used their mobile phones to make calls and browse Facebook but did not use these devices for instructional activities. A few of them, however, used group messenger apps to share information. Classes were conducted in physical classrooms, and there was no use of online classes or digital devices to evaluate students. For instance, a teacher from Lalitpur district stated:

“Yes, I had the knowledge and skills to use digital resources for instructional activities before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, I did not use them in the teaching and learning process. But sometimes I used Viber to send the group message to the students.”

However, almost no participants had prior knowledge of Moodle, Google Forms, or Teams. Out of the sixty-five participants, only fifteen teachers were familiar with PowerPoint, while half of them had no knowledge of other digital resources. Among the teachers who owned personal computers, they only used them to create PowerPoint presentations and display YouTube videos for students to answer examination questions. For example, a teacher from Kaski District said:

Before COVID-19, I owned an Android mobile phone and a laptop. While teaching mathematics, I occasionally used YouTube to demonstrate mathematical shapes such as spheres, cones, and cylinders. I also created PowerPoint presentations for classroom use.

As noted by other teachers, they did not even try or had no desire to use whatever digital devices they had, but they made the adjustment to a face-to-face classroom without digital devices. Making adjustments in lecturing and the chalk-and-duster classroom will decrease the implementation and desire to use digital resources in the future. For example, another teacher from Lalitpur added:

Computers and laptops were less necessary in face-to-face mode. Some apps were used for sharing learning materials. The computer was used basically for official purposes.

None of the teachers who participated in this study reported experiencing success with the use of digital resources in mathematics teaching, and they were not motivated to adopt digital devices and resources in Nepali schools. The participants’ feedback suggested that face-to-face classrooms do not require digital devices and resources. For instance, only a small number of teachers (7) reported having prior experience with digital resources, while the majority stated that they lacked ideas for incorporating them into their classes and were not motivated to use them for classroom teaching. A teacher from Kaski reported:

Yes, sometimes during the year, I take my students to the ICT room, if I needed to demonstrate the relationship of a math topic such as spheres, cones, and cylinders or help them with any other problem. We enjoy making such shapes on the whiteboard.

As a result, the implementation and confirmation processes led to the limited usage of digital devices and resources in classroom teaching due to a lack of both internal and external motivation. This lack of motivation is reflective of the limited implementation and conformity stages in the adoption process of digital resources and devices prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

10. Implementation and Confirmation Stages during COVID-19

The information provided by the participants appears to indicate an initial lack of knowledge about using digital devices to teach students. However, due to the COVID-19 situation and the demand for remote learning, the participants were motivated to learn and adapt. They mentioned learning alongside their partner and friends, indicating that they were able to seek support and guidance from others to acquire new digital skills. This quotation, from a teacher from Lalitpur, highlights the importance of adaptability and continuous learning, especially during times of change and uncertainty:

Initially, I had limited knowledge about utilizing digital devices to teach students. However, as the situation demanded, I began to learn alongside my partner and friends.

Zoom became a popular tool for conducting classes as physical distancing measures during the pandemic forced teachers to generate ideas for online instruction. Most of the time, Messenger was used for every possible activity. They also utilized Zoom and Google Meet for classes and shared materials via email. A teacher from Kaski District stated:

I learned how to use digital resources in my instructional practices during the pandemic. I used Zoom for online classes and Messenger for evaluations and sharing resources. Additionally, I used Microsoft Word to develop course materials. A few of my friends used Google Meet to conduct the classes.

Participants believe that face-to-face classes, where the instructor writes on a whiteboard, are more effective at making steps and processes clear, which leads to increased student understanding. However, when teaching online classes using slides, it can be more difficult to convey the same level of clarity and understanding to students. Additionally, the participants note that non-participation in online classes is a challenge they face, which suggests that students may not be as engaged in online classes as they are in face-to-face classes. Illustrating these challenges, a respondent from Kaski stated:

When conducting face-to-face classes by writing on a whiteboard, we were able to make the steps and processes clear, which increased students’ understanding. However, it was difficult to impart knowledge through slides in an online class. Sometimes we face non-participation in online classes.

As there was no alternative to using digital resources during the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers began using platforms such as Messenger and Viber to share materials and conduct classes, as well as utilizing Google Forms for student evaluations. A teacher from Lalitpur noted:

I incorporated digital resources into my instructional practices during the pandemic. I used Google Forms for student evaluations, and email, Messenger, and WhatsApp for sharing resources. Prior to this, I only knew about instructional planning for notes and was not familiar with Google Classroom.

Uncertainty during the implementation stage can be daunting; therefore, it is necessary to be willing to receive assistance from agents of change. However, participants reported that they did not receive the opportunity for training to learn how to operate digital devices and acquire the skills needed to conduct online classes. As a result, they resorted to alternative approaches such as community learning, home learning, and online education. A teacher from Lalitpur stated:

I did not use any digital resources as I lacked both the devices and skills required for instructional activities. Instead, we conducted community learning and home learning. Additionally, there were challenges in accessing the internet and electricity to run digital classes in remote areas of the country.

It is good to hear that the government and local governments started providing online training to teachers for online teaching during the pandemic. It is essential to equip teachers with the necessary skills and knowledge to conduct effective online classes. It seems that the training helped teachers in various areas, such as learning how to join an online class, using a learning management system, developing materials using digital tools such as GeoGebra, and using different software for evaluation, resource sharing, and office work. Such training programs could be beneficial in the long run and prepare teachers for any future emergencies that may arise. A teacher from Kaski said:

Skills like taking online classes, using a learning management system, and developing materials were enhanced by training.

Likewise, a teacher from Lalitpur noted that training programs had improved various competencies, including the use of Zoom and Messenger for virtual lessons, Google Forms and the school’s software for assessments, and email and Messenger for exchanging learning materials. The trainings supported the development of teaching material, software usage for offices, learning management systems such as Google Classroom, and the school’s software. Due to time constraints, teachers developed digital skills from various sources, such as Google, through training, watching online tutorials, accepting suggestions and support from staff and friends, studying the user guide, and “self-practice,” said a teacher from Kaski:

In the training, we learned how to operate the Digital Nepal App and conduct online classes, how to create groups, and how to evaluate homework assignments and check them through the app. Email and WhatsApp were used to share resources. Office packages were used for material development. The Digital Nepal App is used for learning management systems and instructional planning. The messenger group is utilized for information updates.

Despite the impossibility of contacting all teachers who were situated in remote regions, a number of them received training from welfare organizations. However, it was clear that teachers who were unable to receive training had an inadequate understanding of their role in adopting technology. They were uncertain and, based on their experiences of adopting digital devices and tools as teachers, they noted the need for training from the government or any other organization. Teachers who were not able to join the training had developed their skills through a self-learning process. A teacher from Kaski said, “I had developed my skills to use these tools by watching online tutorials and by self-practice.” Similarly, a teacher from Lalitpur said, “We tried to conduct physical classes, but we could not conduct online classes.” Some teachers received training organized by various organizations, but most of the teachers learned on their own with the support of Google and friends.

Teachers highlighted the benefits of digital training, including the ability to prepare materials for teaching, engage in collaborative learning, and conduct virtual classes on platforms such as Zoom and Facebook Messenger. The trainings covered topics such as online class management, material creation, resource sharing, student assessment, and instructional planning. All teachers agreed on the necessity of digital training, with one teacher from Kaski emphasizing the importance of staying up-to-date and developing basic skills:

We must not be left behind in this digital world. At least basic skills should be learned by teachers.

During the implementation stage, it was crucial for teachers to be willing and able to make adjustments in their use of digital devices and resources for online classes, including adapting their methods for assessing students, assigning work, and communicating with students. However, some teachers reported that students struggled to adjust to online classes and were unwilling to actively participate, such as by muting their microphones and refusing to answer questions. Both students and teachers faced challenges with screen sharing, whiteboard usage, and the proper use of online meeting platforms. In the confirmation stage of Rogers’ theory, users reflect on the process and outcomes and seek support for their decisions. Some teachers expressed a desire for more training to better prepare for similar emergencies in the future. One teacher from Kaski emphasized the importance of digital training in the age of computers, noting that it could help teachers prepare for future pandemics.

According to a teacher from Lalitpur district, quality online instruction requires equal participation and responsibility from all stakeholders, including parents, teachers, administrators, government, the School Management Committee, and other organizations. Similarly, a teacher from Kaski Disctict emphasized that the continuity of online instruction depends largely on the support provided by stakeholders such as parents, teachers, administrators, government, SMC, and other organizations. Additionally, a teacher from Lalitpur suggested that SMC should provide opportunities for teachers to participate in online training and follow-up programs and demand a budget from the government for such activities. However, the support provided in this regard was found to be inadequate. Lastly, a teacher from Kaski disctrict revealed that their school did not provide support for managing digital resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding support, almost all teachers expect financial support from the local government, such as rural municipalities, and a few teachers reported receiving support from the municipality. Additionally, in the example provided by the teacher from the Kaski area: “The government has supported the management of online classes, while the SMC has supported the creation and overall management of online classes.”

Most teachers expect funding to be made available from federal and local governments. For example, some teachers from rural municipalities stated that the municipality provided a free sim card to the students, but no one provided a budget for buying digital devices such as computers, laptops, or mobiles. Similarly, a teacher from Lalitpur reported that Digital Nepal Pvt. Ltd. provided a subsidy to the Digital Nepal App for school education management. The company provided the subsidy only to community schools for the promotion of the digital management system. An informant from Kaski said:

Not much, but a small amount is provided by the Municipalities for buying mobile data.

Two teachers’ replies highlighted the issue of inadequate ICT training and digital resources. The government plays a crucial role in managing online classes, and it should provide support by conducting ICT training for teachers, providing devices, and offering an excess of networking for every student. A teacher from a rural area emphasized that the government or administrators should make digital resources available and equip every school with sufficient ICT resources by providing a suitable budget and needs-based training.

Teachers have emphasized the important role of parents in ensuring quality online education. However, they also recognize that parents may face challenges in providing the necessary materials, equipment, and internet access for online classes. One teacher from Kaski suggested that schools and local administration should provide economic support to help parents and schools equip students with the necessary tools for effective online learning. Another teacher emphasized the need for teachers to perfect their teaching skills for online classes and develop digital resources, while also cooperating with parents, students, and school administration.

11. Challenges Faced in Online Classes

While some teachers have found success in implementing online classes, many have also faced challenges related to the use of digital resources in teaching and learning. These challenges are associated with the potential for both success and failure in online education. The teachers in the study identified several significant difficulties, including unstable internet connections, frequent power cuts, student absenteeism, background noise in virtual classes, and evaluating assignments.

Teachers in this study reported that lessons taught in online classes often had to be reviewed again in physical classes later, as students faced issues with unstable internet connections and frequent power cuts. Additionally, some students were absent or unresponsive during virtual classes, and background noise from their homes posed a problem. Teachers also faced difficulties when evaluating assignments, as some students were not submitting work or were copying from their peers. In some cases, students would even turn off their video and play mobile games during class. According to a teacher from Kaski district:

Collaborative study is not possible as students are studying from home. Teachers are finding it very difficult to make students pay attention during online classes. It is also challenging to treat all students equally and provide individual feedback to each student.

A rural teacher from Lalitpur shared an interesting story about digital-skills-based training and instructional practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the online class, there were frequent disruptions caused by electricity outages and slow internet connectivity, which necessitated multiple attempts to reconnect with the students. This experience was memorable for the online class interaction. The teacher faced challenges due to slow internet connectivity or a complete lack of it but had documents in her email that may not be easily accessible to students.

An urban teacher also shared an interesting story related to digital-skills-based training during the pandemic. The municipality conducted a two-month online ICT training where they learned many things (Khanal et al., 2022 [10]; Joshi et al., 2023 [31]). The teacher collaborated with friends on assignments and also shared their own new knowledge.

12. Implementation and Confirmation of the Use of Digital Devices, Digital Resources, and Digital Skills after COVID-19

As COVID-19 restrictions gradually eased, schools reopened, and teachers returned to the classroom to resume teaching in the new normal. However, some teachers, including the one from Lalitpur district, continued to use digital tools such as messenger groups and GeoGebra to provide reading materials and share mathematical concepts, respectively. Nevertheless, the same teacher did not use digital devices for evaluation purposes after the pandemic. Similarly, a teacher from Kaski stated that:

Digital resources were not employed in instructional practices following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Despite the necessity of alternative modes of instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic, schools have now resumed physical classes in the post-COVID era. When teachers discussed their use of the digital skills they acquired during the pandemic in the classroom, they did not emphasize the importance of continuing to use these skills in the traditional classroom setting, which would enable them to maintain the same level of instruction as during the pandemic. Many teachers are accustomed to conducting face-to-face classes without relying on technology, but it is important to recognize the value of digital tools in enhancing and improving the quality of education. Almost all the teachers expressed a similar sentiment regarding the reluctance to continue using digital resources in the post-COVID period:

We enjoy teaching in face-to-face classes and therefore do not believe that digital devices and resources are necessary for physical classes.

The face-to-face mode of instruction is the usual method in Nepali educational institutions, whereas online instruction is a new modality. There are significant differences between these two models. According to a respondent from the Kaski district:

“There are many differences between face-to-face and online instruction. Online classes can be difficult for students at different levels of proficiency; it is not possible to provide differentiated instruction to students with varying abilities, and evaluation can be challenging; it can be difficult to develop instructional materials, and maintaining discipline among students in online classes is challenging. In contrast, these things are possible in face-to-face classes. Therefore, in the informant’s opinion, face-to-face instruction is more effective than online instruction.”

A respondent from Lalitpur District stated:

“I strongly believe that there are huge differences between face-to-face and online instruction and that face-to-face classes are far superior to online instruction. If we consider the results of the SEE (Secondary Education Examination), we can easily see the difference in outcomes between these two modes of instruction.”

Teachers claimed that lessons taught in online classes had to be reviewed again in physical classes later. The students’ data connection was often unstable, with frequent interruptions in class due to power outages. When questions were asked, students could either remain silent or leave the class. Background noise from home environments, homework assignments, and marking pose additional challenges. Some students may become disengaged, playing mobile games during class, turning off their video, or copying homework from their friends, thereby betraying the trust of their teachers. A teacher from Kaski stated:

Collaborative study is not possible with students at home. Teachers find it challenging to keep students engaged and attentive during online classes. Providing equal treatment to all students and individual feedback to those in need is also difficult.

Online teaching and learning are not the first choice of many participants, likely due to their familiarity with and preference for face-to-face instruction, which has been the norm for a long time. As a result, participants believe that the key competitive advantage of face-to-face classrooms is their ability to effectively deliver course content and conduct written examinations in school. Almost all the teachers shared the same opinion that face-to-face instruction is more effective because it enhances students’ engagement, promotes regular attendance, and allows teachers to better understand the psychology of their students. A teacher from Lalitpur district noted:

In face-to-face mode, we are able to evaluate students’ activity, and every type of student can learn effectively “Face-to-face instruction is more effective than online instruction because online classes are one-sided and students may engage in other activities like playing games or talking with friends.”

However, a teacher from a Kaski district shared a different perspective, stating:

“Both online and face-to-face modes are important. Online instruction is particularly beneficial for students who are not able to attend school regularly. Online instruction was especially useful during the pandemic.”

It appears that the participants did not utilize digital devices and software in their teaching despite the resumption of face-to-face classes. They may not be taking advantage of the benefits that technology can offer in enhancing the teaching and learning experience. It also suggests that certain teachers may be more comfortable with traditional teaching methods and may need support and training to incorporate technology into their teaching practices. For example:

“No, I am not using digital devices and software in teaching while face-to-face classes are starting.”

13. Discussion and Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the adoption of digital tools and devices in teaching and learning, as well as the role of online learning in schools located in technologically disadvantaged societies, particularly in the context of less-developed countries. The study examines the implementation and acceptance stages of digital devices and digital tools, as well as online teaching as an innovation, in math classrooms from the school level to universities, during three different time periods: pre-COVID, during COVID-19, and post-COVID-19. To analyze the implementation and acceptance of digital tools and devices, as well as online learning, the study applies Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory [13], specifically its implementation and confirmation stages. Based on the experiences of teachers, the study found that the adoption of digital tools and devices in face-to-face classroom and online mathematics teaching has not yet reached the confirmation stage, even after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, digital tools and devices in classroom teaching and online learning were not widely implemented or accepted by mathematics teachers in these societies. During the pandemic, there was a limited implementation of online learning using digital tools, but the study found that its effectiveness as a viable alternative to traditional classroom teaching had not yet been confirmed by teachers.

The findings of this study suggest that the implementation and confirmation stages of the diffusion theory of innovation were not fully realized in the context of mathematics education in Nepal. The COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to use digital tools, which many teachers had not used before [4]. Prior to the pandemic, there was limited exploration and implementation of digital tools in classrooms, and stakeholders were not motivated to incorporate these innovations into the teaching and learning process. This is consistent with the implementation stage of the diffusion theory, which suggests that innovations must be adopted and utilized by a significant number of individuals to become established as mainstream practices. Teachers lacked exposure to the innovation and did not have a fundamental comprehension of what it is and how it functions [33]. During the pandemic, Nepali mathematics teachers, like teachers in other countries, were required to deliver lessons using various online and digital platforms, such as Zoom, Google Meet, WeChat, and Google Docs [1,2], but they failed to capture the unexpected benefits of being digital natives, contrary to the findings of Pozo et al. [4]. This indicates that teachers need motivation to learn and adapt to new technologies independently, which will help them keep up with the changing educational landscape. Furthermore, mathematics teachers in Nepal lacked exposure to and a fundamental understanding of digital innovation, indicating that they were not yet ready for the confirmation stage of the diffusion theory. In order to confirm the effectiveness and value of an innovation, it must be widely adopted and integrated into regular practices, leading to observable improvements in performance or outcomes. Without this confirmation, the potential benefits of digital tools and devices as an innovation in teaching mathematics may not be fully realized.

The COVID-19 pandemic has compelled teachers to adopt digital tools and devices in online teaching. While many initially lacked the knowledge and skills to use these resources, the pandemic motivated them to learn and adapt. Consequently, many teachers utilized digital tools such as Zoom, Google Meet, and Google Forms to conduct online classes, share resources, and evaluate students. However, the participants noted that face-to-face classes were still considered more effective in making concepts clear and engaging students. Teachers who did not receive training had an inadequate understanding of their role in adopting technology, indicating a need for support from the government or other organizations. Overall, the study emphasizes the importance of adaptability and continuous learning, especially during times of change and uncertainty. It also underscores the need to equip teachers with the necessary skills and knowledge to conduct effective online classes through training programs. Such programs can prepare teachers for any future emergencies that may arise and benefit them in the long run.

Additionally, the study highlights the need for teachers’ university education to promote independent learning skills, irrespective of other influences on the learning process, such as the teaching staff or the classroom environment. This is crucial because technology is rapidly evolving, and training may not be sufficient to keep teachers up to date. Therefore, teachers need to be equipped with the ability to learn independently and to continuously adapt to new technologies. This approach will enable them to stay up to date with emerging trends and technologies in education and to maintain their effectiveness in teaching students.

The study highlights the significance of the use of digital tools and devices in teaching mathematic online as a practical substitute for face-to-face teaching in Nepal, especially during times of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the teachers involved in the study sought confirmation and support from various stakeholders, even though the government had already made the decision to adopt online classes. Despite acquiring new skills during the pandemic, the teachers did not perceive digital teaching to have significant advantages over traditional teaching methods and seemed to be avoiding conflicting cues associated with the use of digital tools and devices in mathematics teaching. The study identified several challenges related to online instruction, such as difficulties in maintaining student engagement and participation, evaluation and feedback, and technical issues such as unstable internet connectivity; these findings align with UNICEF’s [21] report that millions of students worldwide were unable to participate in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic due to a lack of internet connectivity, gadgets, or both. To overcome these challenges and effectively implement online instruction during crises, the study suggests that teachers need targeted training and support from relevant stakeholders. Overall, the study highlights the need for more focused efforts to promote the acceptance and adoption of digital tools and devices in Nepali classrooms.

The successful implementation of online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic was heavily dependent on the level of support from participants; as such, some teachers experienced delays or even discontinued their use of digital resources and devices [13]. This indicates a lack of confirmation of the benefits of these technologies. One important factor that influences the acceptance of innovation is the complexity of the innovation and its ease of use. Innovations that are easy to use and understand are more likely to be confirmed [41]. Stakeholders, including teachers, who were not involved in the evaluation or feedback process were more likely to reject online learning and the use of digital tools in mathematics classrooms in Nepal [39]. Teachers’ attitudes towards and trust of online teaching, as well as the use of digital tools and devices in the teaching and learning process, remain major concerns, particularly during and after the pandemic. As individuals in a social system, teachers may face challenges and issues. Thus, implementers may require technical assistance from change agents and others. A supportive environment, ease of use, and usefulness could be the major factors for acceptance [37]. Table 2 presents the teachers’ responses to the implementation and confirmation stages of digital devices and tools in the teaching and learning process before, during, and after COVID-19.

Table 2.

Teachers’ responses to the implementation and confirmation stages.

The findings of this study could be used to develop policies and guidelines that facilitate the implementation of digital tools in mathematics classrooms in Nepal and other similar contexts. When individuals doubt the ease and usefulness of technology due to technology anxiety, they might reject it entirely [13]. According to Rogers [13], “adoption” is “the process of continuously using an existing idea. Therefore, it is crucial to consider contextual factors when deciding to integrate digital devices and tools in the classroom. Teachers’ attitudes and environments can often impede the adoption of digital resources. For instance, teachers may initially adopt digital devices and tools as a new idea, like online learning, when the situation demands it, but they may stop doing so once the environment returns to its pre-pandemic state, and this cannot guarantee its continuous implementation.

To address this issue, the government and policymakers should focus on enhancing teachers’ knowledge and skills and building their trust in digital tools and technology adoption. Personal development activities such as training programs and workshops can be organized to support teachers’ continuous professional development in digital teaching and learning. Expanding the use of digital resources, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, can also help to build a more resilient and adaptable education system. By paying greater attention to teachers’ knowledge and skills in digital teaching and learning, we can ensure that the adoption and implementation of online learning are sustainable and effective in the long term. Furthermore, teachers’ education in universities must promote independent learning abilities, regardless of any other influences on the learning process, such as the teaching staff or the classroom environment. This is important because technology is changing rapidly, and it may be challenging to update teachers through training. Teachers need to have the ability to learn and adapt to new technologies independently, which will help them keep up with the changing educational landscape.

The implementation and confirmation of the use of digital devices, digital resources, and digital skills after COVID-19 are increasingly crucial. The pandemic has forced many people to work, learn, and interact using digital tools and devices, highlighting the importance of digital literacy for success in many areas of life. Therefore, individuals and organizations must continue to invest in digital technology and skills training to stay competitive in a rapidly evolving digital world. This will not only benefit individuals and organizations but also help bridge the digital divide and promote greater digital inclusion in the physical classroom. It is essential to address the concerns of teachers regarding the use of digital tools in the classroom. Although this study provides useful insights into the use of digital devices and tools prior to, during, and after COVID-19, it is important to note that work experience was not factored into the analysis. This variable may be included in future studies to acquire a more comprehensive knowledge of the use of digital devices and tools across different ages. Future studies could explore the factors that influence teachers’ attitudes towards the use of digital tools as well as the strategies that could be used to increase their acceptance of this innovation. Moreover, future research could investigate how to address the challenges associated with the use of digital devices and tools and improve their effectiveness in mathematics teaching. For instance, research could explore the impact of digital resources and technology on student learning outcomes, as well as the factors that facilitate or hinder the adoption of digital resources by teachers. Additionally, future studies could examine the best practices for integrating digital resources and technology into teaching practices in different contexts. This could involve exploring innovative teaching strategies and pedagogical approaches that support effective learning. In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of digital literacy for teachers and the need for investment in digital technology and skills training for teachers. The adoption and implementation of digital resources and technology in Nepali classrooms are crucial for building a more resilient and adaptable education system. By addressing the challenges associated with online instruction, we can improve the effectiveness of digital resources and technology in teaching and learning, ultimately benefitting students and society as a whole.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.J. and J.K.; methodology, D.R.J.; software, D.R.J. and R.H.D.; validation, D.R.J.; formal analysis, R.H.D. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has obtained a letter of permission from Nepal University to conduct the research and adheres to the standards outlined in our ethical guidelines for conducting research involving human subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions and may be provided in special request to the corresponding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to all the mathematics teachers who participated in this research study. Their invaluable insights and contributions were critical in ensuring the successful completion of this project. The authors would also like to express their appreciation to the MPhil scholars from Nepal Open University who generously offered their time and support to the data collection process. Their commitment to this research was instrumental in the acquisition of crucial data that greatly informed the findings of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hodgen, J.; Taylor, B.; Jacques, L.; Tereshchenko, A.; Kwok, R.; Cockerill, M. Remote Mathematics Teaching during COVID-19: Intentions, Practices and Equity; UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videla, R.; Rossel, S.; Muñoz, C.; Aguayo, C. Online Mathematics Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Didactic Strategies, Educational Resources, and Educational Contexts. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, J.-I.; Pérez, E.M.-P.; Cabellos, B.; Sánchez, D.L. Teaching and Learning in Times of COVID-19: Uses of Digital Technologies During School Lockdowns. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 656776. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.656776 (accessed on 28 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Dawadi, S.; Giri, R.; Simkhada, P. Impact of COVID-19 on the Education Sector in Nepal—Challenges and Coping Strategies. Sage Submiss. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumiller, M.; Rinas, R.; Hein, J.; Janke, S.; Dickhäuser, O.; Dresel, M. Shifting from face-to-face to online teaching during COVID-19: The role of university faculty achievement goals for attitudes towards this sudden change, and their relevance for burnout/engagement and student evaluations of teaching quality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 118, 106677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Watterston, J. The changes we need: Education post COVID-19. J. Educ. Chang. 2021, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulaziz, M.S. COVID-19 and the use of digital technology in mathematics education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7609–7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, B.; Joshi, D.R.; Adhikari, K.P.; Khanal, J. Problems of Mathematics Teachers in Teaching Mathematical Content Online in Nepal. Int. J. Virtual Pers. Learn. Environ. 2022, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmo, A.; Maffia, A. High School Students’ Use of Digital General Resources During Lockdown. Eur. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2022, 10, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lalani, F. The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Education Forever. This Is How. World Economic Forum. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003.

- Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (8 May 2020). Notice. Government of Nepal. 2020. Available online: https://mocit.gov.np/notice (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Bhujel, K. The Impact and Challenges of Teachers’ Professional Development Training of Mathematics at Primary School Level in Nepal. NUE J. Int. Educ. Coop. 2019, 13, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Baeten, M.; Struyven, K.; Dochy, F. Student-centred teaching methods: Can they optimise students’ approaches to learning in professional higher education? Stud. Educ. Eval. 2013, 39, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrahim, F.A. Online teaching skills and competencies. TOJET Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 19, 9–20. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1239983.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- UNESCO. Diverse Approaches to Developing and Implementing Competency-Based ICT Training for Teachers: A Case Study (Vol. 1). 2016. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/bdfx6ext (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Cevikbas, M.; Kaiser, G. Flipped classroom as a reform-oriented approach to teaching mathematics. ZDM Math. Educ. 2020, 52, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.R.; Chitrakar, R.; Belbase, S.; Khanal, B. ICT competency of mathematics teachers at secondary schools of Nepal. Eur. J. Interact. Multimed. Educ. 2021, 2, e02107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. COVID-19: Are Children Able to Continue Learning during School Closures? A Global Analysis of the Potential Reach of Remote Learning Policies. UNICEF for Every Children. 2020. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/remote-learning-reachability-factsheet/?_gl=1*efdp5*_ga*MTAxODMzNzAxMi4xNjgwMjI4MDgw*_ga_9T3VXTE4D3*MTY4MzE2ODg1Ny4zLjEuMTY4MzE2ODg1Ny4wLjAuMA (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Bettinger, E.P.; Loeb, S. Promises and pitfalls of online education. Evid. Speak. Rep. 2017, 2, 1–4. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ccf_20170609_loeb_evidence_speaks1.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- OECD. Education Responses to COVID-19: Embracing Digital Learning and Online Collaboration. OECD Publishing. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/education-responses-to-covid-19-embracing-digital-learning-and-online-collaboration-d75eb0e8/ (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Tang, C.; Thyer, L.; Bye, R.; Kenny, B.; Tulliani, N.; Peel, N.; Gordon, R.; Penkala, S.; Tannous, C.; Sun, Y.-T.; et al. Impact of online learning on sense of belonging among first year clinical health students during COVID-19: Student and academic perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U. Online Learning: Challenges and Solutions for Learners and Teachers. Manag. Labour Stud. 2023, 48, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahito, Z.; Shah Sayeda, S.; Pelser, A.-M. Online Teaching During COVID-19: Exploration of Challenges and Their Coping Strategies Faced by University Teachers in Pakistan. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 880335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, J.H.; Lehmann, D.R. Multigeneration innovation diffusion: The impact of intergeneration time. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 31, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei-Landau, R.; Muchnik-Rozanov, Y.; Avidov-Ungar, O. Using Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory to conceptualize the mobile-learning adoption process in teacher education in the COVID-19 era. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 12811–12838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Nedungadi, P.; Amrita, R.P.; Banerji, S.; Mohan, R.; Ramesh, M.V. Investigating the factors afecting the adoption of experiential learning programs: MBA students experience with live-in-labs, 2020. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Bangalore Humanitarian Technology Conference (B-HTC), Vijiyapur, India, 8–10 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.R.; Khanal, B.; Adhikari, K.P. Effects of Digital Pedagogical Skills of Mathematics Teachers on Academic Performance. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgurovic’, M. Technology-Enhanced Blended Language Learning in an ESL Class: A Description of a Model and an Application of the Diffusion of Innovations Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, J.W.; Cox, J.G. Diffusion of innovations theory, principles, and practice. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Li, H.; Song, L. social media and attitude change: Information booming promote or resist persuasion? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 596071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M.B.; Borokhovski, E.; Schmid, R.F.; Tamim, R.M.; Abrami, P.C. A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2014, 26, 87–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, D.; Oliver, M. Student engagement and blended learning: Portraits of risk. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okocha, F. Acceptance of blended learning in a developing country: The role of learning styles. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2019, 2226. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2226 (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Damanpour, F. Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 555–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.D.; Brooks, G.R.; Goes, J.B. Environmental jolts, institutional entrepreneurship, and the creation of new organizational forms. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1464–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, B.D. Girl students in mathematics at bachelor level colleges of Kathmandu valley, Nepal: Some problems and prospects. Voice Teach. 2021, 6, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).