Abstract

Since the mid-20th century, tourism has become a strategic activity for the economy of the Balearic Islands, causing profound social, territorial, and environmental transformations. This fact challenges local society, which must be aware of its environment to better face the future challenges posed by this economic activity. With this goal, the official curriculum has been analyzed, making it possible to ascertain the approach with which this subject is taught by the administration and what objectives are set. Furthermore, a review was carried out of the contents of geography textbooks in the third year of ESO and the second year of the Baccalaureate, which corresponds to the educational stages in which tourism aspects appear. The results obtained represent a fundamental strategic diagnosis to improve the teaching and learning of this key activity for the Balearic Islands, giving it more importance and adapting its approach to the current times.

1. Introduction

The tourism industry is one of the economic activities that has grown the most in recent decades, representing 10.3% of the world GDP [1], with the Mediterranean as one of the most important tourist areas on the planet. Since the second half of the 20th century, this region of the world has seen uninterrupted tourism growth [2,3,4], causing deep economic [5,6,7,8], social [9,10,11], and environmental transformations within it [12,13,14]. Within this geographical context, this research analyzes the case of the Balearic Islands (Spain), which with 16.2 million tourists [15] is one of the main tourist destinations in the Mediterranean.

Just as Marins et al. [16] point out, tourism can be characterized as a beneficial phenomenon for the agents that constitute it and for the towns and cities that participate in it; however, it can also contribute to intensifying sociocultural tensions, economic dependence, and environmental degradation [17,18], just as it has been observed in the case of the Balearic Islands [19,20,21]. On this issue, it should be noted that the discontent of locals towards tourism and the disputes between residents and tourists are becoming more frequent throughout the world [22], including the Balearic Islands [23,24]. Researchers such as Martins [25] have associated these coexisting conflicts with low levels of education. Other authors such as Andereck et al. [26] point out that education can contribute to a better understanding of the tourism industry.

Therefore, there is no doubt that there are contact points between education and tourism [27], which go beyond professional formation [28,29,30,31,32]. The dynamism of the socioeconomic, technological, environmental, and political environment is causing the research paradigm to change in recent years to respond to the needs of all interested agents [33,34]. Consequently, the focus of analysis on the relationship between education and tourism has broadened, showing that education has an impact on many aspects of tourism, beyond the formation of human capital [35]. Some studies have addressed the relationship between education from the perspective of competitiveness [36], innovation [37,38], hospitality [39], and sustainability [40,41,42]. All of this has helped to reinforce the role that education can play in tackling tourism problems such as economic monoculture, job insecurity, human pressure, climate change, and the loss of identity and heritage, among others.

Although tourism education has taken root in colleges and universities [43], its presence has been very limited in secondary education institutes [44]. This is reflected in the fact that there are still few studies that have made didactic proposals to incorporate tourism aspects into secondary education, achieving significant learnings [45,46]. The present investigation is framed around this point, entering a little-explored study niche such as pre-university tourism education [47] despite the fact, just as some authors point out [48], that this subject has great potential since it is at this stage of education when students are first introduced to the study of tourism [49,50].

Thus, this paper analyzes the approach to the curriculum and the contents of tourism proposed in the books on the different courses of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO in advance) and Baccalaureate in the Balearic Islands. In this way, the aim is to contribute to fostering the debate in the scientific field on the contents of teaching materials and the way in which tourism is taught, given its growing relevance in today’s society [51,52,53]. This topic is relevant in the current post-COVID context, where the need for a value-based education as a part of a future orientated towards sustainable tourism [54] may be limited by the pro-rapid recovery positions of the industry, which are reluctant to make broader efforts to reform tourism to make it more ethical and sustainable [55,56].

Despite the evidence highlighting the need to enhance tourism education, the starting hypothesis of this research is that few resources have focused on analyzing and explaining this phenomenon in pre-university studies, even in regions such as the Balearic Islands, where according to data from 2019, this activity represented 41.3% of GDP and employed 41.6% of the working population [57]. Therefore, the overall objective of this document is to examine the limitations and possibilities of textbooks to promote skills to transform tourism towards sustainable development.

2. The Role of Geography in the Spanish Secondary School

In Spain’s compulsory secondary education (ESO), there is no specific subject for tourism and it is taught in geography [58], as happens in other countries of the world [59,60]. As Moreno [61] points out, this is since, unlike other disciplines, the geography curriculum facilitates the approach of transversal themes. In the case of tourism, geography makes it possible to obtain holistic knowledge, since socioeconomic and natural aspects of other aspects converge in this economic activity, facilitating the understanding of the tourist phenomenon [62]. In Spain, the teaching of tourism in pre-university studies has focused mainly on the analysis of the social, economic, and environmental components of tourism, having been able to identify three large blocks of content: the tourist space, the tourist system, and the impacts of tourism.

However, geography shares a subject with history during the first two years of ESO, remaining independent in the third and not studied in the fourth. In this way, in the first year, the contents of physical geography are taught, and in the second year the contents of human geography. The contents of the third year of ESO are completely geographical, and although it is usual to review what has been worked on in previous courses, they focus above all on economic aspects, particularly when the issue of tourism is addressed in this course. Therefore, this course is key to the teaching of tourism, since it is the last one in which a large part of the student body is taught geography. Only those students who continue their education stage through the Baccalaureate of Social Sciences and Humanities modality have the option in the second year of choosing geography [63].

3. Materials and Methods

The following study has set two main objectives in order to analyze systematically the content curricula and textbooks. These are:

- (1)

- To know the vision that is transmitted about tourism in the geography textbooks in secondary and high school.

- (2)

- To analyze the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of geography textbooks for teaching tourism.

To do this, it is necessary to analyze the curricula and information from the books that address the mentioned subject. Following this, the following research questions are:

- What information about tourism is included in geography curricula?

- What information on tourism is offered and what is omitted from textbooks?

- What are the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of current geography textbooks for tourism education?

It should be noted that this article does not incorporate in its study the content of the new educational law, the LOMLOE, since this will begin to be fully applied (in all secondary school courses) after the investigation, during the 2023–2024 academic year. Therefore, the analysis presented is based on what is established by the LOMCE (Organic Law 8/2013, of December 9, for the improvement of educational quality). Thus, to find out what is taught about tourism in pre-university education in the Balearic Islands, Decrees 34/2015 and 35/2015 have been consulted, through which the ESO and Baccalaureate curriculum is established in the Balearic Islands.

Even though many educational centers are incorporating digital learning materials [64], it has been decided to inquire about printed books, since they continue to be the preferred teaching materials in the field of formal education [65,66]. Specifically, the examples for the 2021–2022 academic year have been consulted; therefore, they are teaching materials that were published following the curricular criteria of the LOMCE and Decrees 34/2015 and 35/2015. The textbooks chosen correspond to those of the three publishers with the largest circulation, which are available in most schools in the Balearic Islands (Table 1).

Table 1.

Geography schoolbooks that have been analyzed.

The analysis of these textbooks has been carried out systematically, delving into their contents [67] to understand the characteristics under which tourism is institutionally conceived and which are the guidelines that are prescribed for teachers of secondary education in the Balearic Islands. To achieve the proposed objectives, a transversal and structured methodology has been used that develops a descriptive–interpretative analysis within the qualitative paradigm [68]. Aspects have been identified, such as the unit in which tourism is framed, the topics covered, the theoretical approach, the proposed activities and materials provided, and the geographical context in which the work is conducted. Finally, based on the results obtained, a SWOT analysis has been performed, showing the main pros and cons of the didactic materials regarding an economic sector of capital importance in the Balearic Islands.

4. Results

4.1. Tourism in the Geography Curriculum of Secondary and High School

From the analysis made, it has been observed that the treatment of tourism within the geography curriculum in the Balearic Islands is performed tangentially in secondary school and more specifically in high school. The contents linked to tourism are usually integrated within the economic branch of geography and are usually included in the topic of economic sectors and tertiary activities.

Despite the socioeconomic and environmental importance of tourism in the Balearic Islands, tourism does not appear explicitly in the secondary school curriculum. It only implicitly refers to tourism in the competency aspect and the objectives, since the contents, evaluable learning standards, and evaluation criteria of this reference do not appear.

Contrary to the secondary school curriculum, in the Baccalaureate there is explicit reference to tourism, both in the contents and also in the evaluation criteria and the evaluable learning standards (Table 2). Regarding tourism, special emphasis is placed on the study of this sector in the Balearic Islands and the relationship it maintains with the environment.

Table 2.

References to tourism in the high school geography curriculum.

In the part of the didactic objectives, the Baccalaureate curriculum also develops a good number of these issues, focusing on the understanding and knowledge of the territory, valuing environmental impacts and interest in environmental heritage, as well as observing how the territory is interacting with the expansion of tourism. Sustainability and the effects of tourism are a reason that is constantly present in the curricular formulation, which suggests a proactive position on the part of the administration and an awareness of the situation concerning tourism in its territory.

As regards the learning standards, different tourism-related competencies are also required, all of them related to spatial skills and the ability to identify, analyze and express geographic content. In this sense, it can be noted that the curriculum has a predominance of didactic strategies that encourage students to inquire, reflect and demonstrate critical thinking regarding problems and processes that occur in their environment [69]. Thus, students must know the situation of the geography of tourism in Spain and the Balearic Islands, considered by the curriculum a “part of the whole”, meaning it is contextualized in the local reality, but always within a global framework. Consequently, the student can acquire a more analytical vision and a broader scope of the geographical processes associated with the tourist activity in their territory.

4.2. Tourism in Secondary and High School Geography Textbooks

Textbooks have a legitimizing role in teaching, as teachers tend to believe that curriculum requirements are met by following the materials [70], and consequently, learning outcomes are often assessed about their content [71]. On the other hand, the content that these books offer about tourism significantly influences the construction of the social representations of the students, given that they are perceived as objective and rigorous materials with scientific evidence [72]. From a curricular point of view, this stage represents the first contact with tourism for ESO students, and the approach taken is essential to determine the students’ initial view of this topic.

In secondary geography textbooks, the contents associated with tourism are usually included in the blocks of economic geography, mainly, within the topic of the tertiary sector (Table 3). These are characterized by a strong descriptive orientation of tourism.

Table 3.

Title of the units where content and activities on tourism are collected in the different ESO textbooks.

Regarding the type of content, a unanimous presence of the types of tourism, the location of tourist areas, and the socioeconomic and environmental impacts derived from tourism have been observed. Usually, it starts from a global vision of the tourism phenomenon that is completed with a final annex dedicated specifically to Spain and the Balearic Islands. These issues are usually addressed through graphic materials and case studies, given their capacity to highlight the relationship between theory and daily practice.

In the Balearic Islands, the predominance of an economic vision of tourism has been observed, highlighting the presence of graphs and statistics to explain the importance of this sector for the economy and the labor market. On the other hand, sun and beach tourism is highlighted as the dominant type, and the effects that this model has at a spatial and temporal level are explained. Firstly, the concentration of the tourist offers on the coast and, secondly, the concentration of demand during the summer months is addressed.

Also, it should be said that as it is an intermediate course in ESO, teachers are not subject to a stage-ending evaluation, which allows teachers to have a greater margin of action with respect to the curricular lines and to complement the contents of the book with other types of activities.

In high school geography textbooks, tourism is covered much more deeply than in the secondary school stage. However, as in secondary school, there isn’t a specific theme dedicated to tourism, and it is incorporated as a part of the theme of services. Also, it should be noted that the content and development of the subject are highly marked by the Exam for University Access (EvAU), which is a major curricular conditioner when planning and didactically designing the teaching and learning of geography [73].

In the archipelago’s case, the geography test at the EvAU is divided into four parts: a mapping section, a brief definition section, and two comment sections (graphs, statistics, maps, or texts). Tourism in these sections is evaluated by commenting on graphics, statistics, texts, or thematic maps on tourism development and inequalities in the tourism space in Spain and/or the Balearic Islands. In addition, there are definitions of concepts related to tourism, such as agrotourism, tourist rental, tourist seasonality, tourist monoculture, discretionary transport, alternative tourism, mass tourism, non-hotel occupancy, tour operator, and overbooking.

The textbooks analyzed are dealing with tourism from a descriptive perspective and following a very similar content structure (Table 4), characterizing the sector itself in the first place and, to enter later on, the location of the tourist areas, the different problems and processes related to this economic activity and its territorial interactions. The theoretical contents are accompanied by abundant graphs, tables, maps, and specific texts. In a complementary way, case studies or topics are presented that are in line with the current and future challenges of Spanish tourism, such as the National Comprehensive Tourism Plan (PNIT), the 2030 Agenda, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

Table 4.

Title of the units where content and activities on tourism are collected in the different textbooks for the second year of high school.

Besides this, the word “Balearization” is mentioned in the books, taking into account a process of massive urbanization and the lack of control that led to an overgrowth in tourist infrastructures and human pressure in the coastal areas. Finally, it should be noted that in the books analyzed it has been observed that not all the definitions of the key concepts of the EvAU appear, which obliges teachers to provide students with a glossary of all the definitions.

4.3. A SWOT Analysis of Tourism in Geography Textbooks

After the analysis of geography textbooks, a clearer picture of what the current situation of tourism is in these books appears. Therefore, we can apply the SWOT methodology and see what the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of these publications (Table 5) are, which will allow us to offer a strategic diagnosis for future debates on this issue.

Table 5.

SWOT matrix based on the treatment of tourism in geography textbooks in secondary and high school.

Another observed in textbooks is that little use is made of Geographic Information Technologies (TIG), despite being fundamental tools for active methodologies such as project-based learning and student-based learning [74,75]. These tools foster the acquisition of spatial knowledge and location-based skills [76], which are essential to be able to carry out spatial reasoning about tourism.

Textbooks can be considered indicators of the current social and political situation, and markers of how groups and/or ideas have weight in official knowledge [77]. In this sense, it has been observed that despite the importance of tourism for the socioeconomic and environmental metabolism of the Balearic Islands, no specific chapter or didactic unit is dedicated to it. This fact is noteworthy, since in all the books the tourist question is always included in relation to other activities in the third sector, such as transport or commerce. In addition, a positive approach to tourism (showing transformations and economic benefits) rules over a negative one, with the negative effects it generates appearing to a lesser extent.

Another aspect to highlight is that the information sources that feed the different maps, diagrams, and graphs that complement the text contents are almost always official sources from public organizations and governmental or supranational associations. The lack of citations in scientific articles is notorious, removing from the student’s perspective the possibility that the contribution of science may be useful for their learning of the processes surrounding tourism.

Furthermore, an issue that should be reconsidered from the analysis of the textbooks is the need to incorporate technology in the teaching–learning processes of tourism in secondary education and high school. Although there are numerous experiences supporting the educational potential of the use of GIT in the field of geography [78], its use for teaching tourism has barely been explored so far in textbooks. However, its application can contribute to the acquisition of spatial skills for citizens [79] that can contribute to a better understanding of the tourism phenomenon.

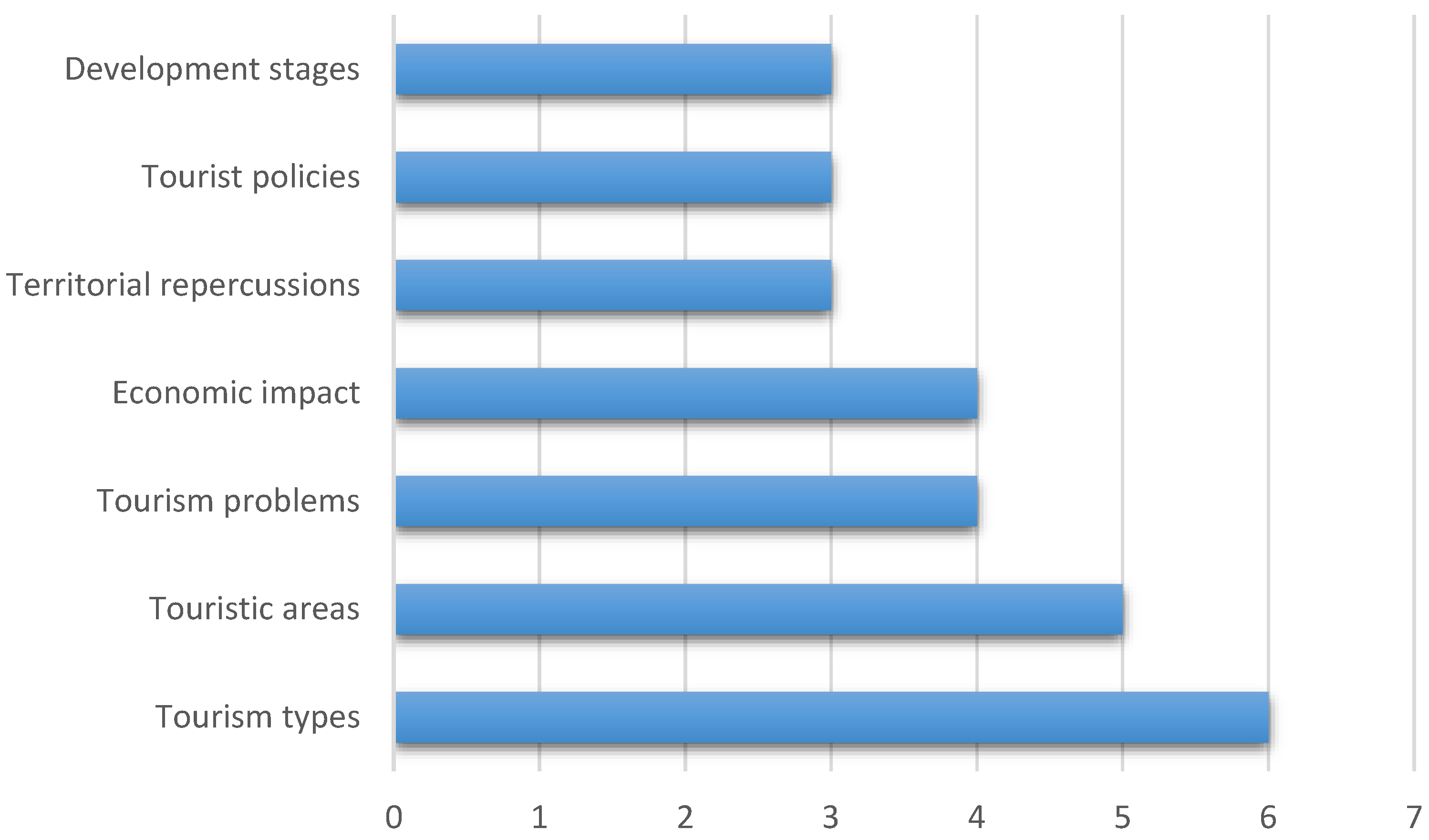

A recurring characteristic between the different topics is the repetition of contents that are shown between the two courses wherein tourism is taught (Figure 1). Although data is shown at different scales, generic aspects such as tourist typologies or territorial repercussions can occur due to the sightseeing, and duplicates are seen, sometimes making specific reference to each geographical context. This repetition of content and the rote nature of the subject has sometimes made it be considered tedious, with a lack of interest from the general public [80], a characteristic that goes against its prestige and significance in learning.

Figure 1.

Most repeated epigraphs in the analyzed textbooks.

Many textbooks, even having gone through many editions, continue with the classic structure of contents marked by educational law, with little room for innovation or a differentiated presentation of the contents, either by the grouping of sectors or by the topics that are shown. This scheme omits aspects that in recent years have become relevant and that today are basic when it comes to talking about tourism; thus, uncovering some of the shortcomings of both the curricular proposal and the work embodied in the books. Some of the most important topics specific to the geography of tourism, both globally and nationally, are omitted in the thematic blocks of the books analyzed and are as follows:

- -

- Tourism and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- -

- The expansion of Tourist Use Housing (VUT) as an alternative to traditional accommodation.

- -

- The effects of tourist seasonality.

- -

- The tourist saturation (overtourism) and the debates on the tourist decrease.

- -

- The new forms of intelligent tourism management of destinations (Smart Destinations).

- -

- Types of accommodation on the rise: boutique hotels and inland hotels.

- -

- Climate change and tourism.

- -

- The energy crisis and tourism.

The incorporation of current issues within the teaching of tourism can play a transcendental role when it comes to addressing the social and environmental challenges of the 21st century [81], since it can stimulate future generations to adopt new ways of thinking, behaving, and acting that match the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the 2030 Agenda [82]. SDG 4 points to quality education as an essential pillar that should help achieve these challenges. The new education law known as LOMLOE (Organic Law 2/2020 that Modifies the Organic Law of Education) is focused on this line, which will be fully applicable in Spain from the 2023–2024 academic year, replacing the current one (analyzed in this article) with the contents and evaluation criteria to direct education towards these objectives more clearly [83,84].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In the case of the Balearic Islands, despite having a great tourism dependency, this economic activity has a reduced presence in non-university education. The results obtained follow the path of others such as Eade [85], and Shalem and Allais [86], who showed that the presence of tourism is more significant within secondary education than at other educational levels, just as it happens in high school. This circumstance is reflected in the analyzed textbooks, where tourism has more importance in the Baccalaureate books with respect to the secondary ones.

However, the curriculum in ESO is more flexible than in high school, which is highly conditioned by the rigidity of the EvAU. In any case, the possibility of taking advantage of this greater flexibility to deepen the teaching of tourism in secondary school will depend on the perception that teachers have about tourism [47] and the teaching they may have on the subject [58]. Thus, the learning of tourism by secondary school students is subject to the personal characteristics of the teacher [50].

Moreover, it is key to note that students tend to read textbooks as neutral descriptions and not as the “masterfully crafted social instrument to achieve a social purpose” [87] (p.502) that they ultimately are. This fact makes it even more crucial that textbooks offer insight into the complexities related to socially and environmentally controversial contexts [88,89]. However, based on the analysis, it has been observed that an economistic approach to tourism continues to predominate, with few teaching materials that provide critical thinking with respect to the effects that tourism generates on the socio-economic and environmental metabolism of the territories in which it is intensely developed, as would be the case for the Balearic Islands. To make up for these shortcomings, it is recommended that teachers use complementary materials, such as research articles, press reports, or documentaries, which contribute to a more comprehensive teaching–learning process concerning tourism.

In addition, the contents of textbooks frequently do not match the reality of tourism, since it is an economic sector that changes rapidly and makes it difficult to adapt the materials to the current situation [90], as has been verified with the COVID-19 pandemic [91]. Therefore, it would be recommendable that teachers use other types of teaching resources that can adapt more quickly to changes in the tourism industry, such as digital books, project-based learning, or field trips [92]. This last learning methodology can be especially beneficial for students [93], given that in the Balearic Islands there are many tourist spaces in which to work on aspects of said activity and generate more significant learning. Also, this fact can help to establish roots in the students, which encourages them to be more in contact with the territorial reality and helps them to be aware of the changes produced by tourism in the geography of the archipelago and its environment in general.

Finally, it should be noted that education, as a social phenomenon, must respond in its contents and approaches to what occurs in the environment of the students [27]. In this way, given the importance of tourism in the Balearic Islands, a tourism education that contributes to the training of future generations in the face of the challenges that tourism entails for society is essential. For this, it is proposed to link the contents of tourism to the objectives of the 2030 Agenda, given that these objectives can contribute, directly or indirectly, to responding to these challenges of tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.À.C.-R. and V.P.; methodology, V.P. and M.À.C.-R.; validation, A.O., V.P. and M.À.C.-R.; formal analysis, V.P. and M.À.C.-R.; investigation, V.P.; resources, V.P. and M.À.C.-R.; data curation, A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, V.P.; writing—review and editing, V.P., M.À.C.-R. and A.O.; supervision, A.O., V.P. and M.À.C.-R.; project administration, M.À.C.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Balearic Islands University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019—Travel and Tourism at a Tipping Point. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2019.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Salvà, P.A. Los modelos de desarrollo turístico en el Mediterráneo. Cuad. Tur. 1998, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodorou, A. The demand for international tourism in the Mediterranean region. Appl. Econ. 1999, 31, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, C.; Morey, A. The growth of mass tourism in the Mediterranean, 1950–2010. IOSR J. Econ. Financ. (IOSR-JEF) 2016, 7, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreto, L.; Manera, C.; Pohl, M. (Eds.) Europe at the Seaside: The Economic History of Mass Tourism in the Mediterranean; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar, R. Tourism in the Mediterranean: Scenarios up to 2030. Available online: www.medpro-foresight.eu (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Ren, T.; Can, M.; Paramati, S.R.; Fang, J.; Wu, W. The impact of tourism quality on economic development and environment: Evidence from Mediterranean countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, E.; Sigeze, C.; Manga, M.; Birdir, S.; Birdir, K. The relationship between tourism, CO2 emissions and economic growth: A case of Mediterranean countries. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Pizam, A.; Milman, A. Social impacts of tourism: Host perceptions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1993, 20, 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Proudfoot, L.; Smith, B. The Mediterranean: Environment and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, Y.; Leontidou, L.; Loukissas, P. Mediterranean Tourism: Facets of Socioeconomic Development and Cultural Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. (Ed.) Coastal Mass Tourism: Diversification and Sustainable Development in Southern Europe; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, A.M.; Olcina-Cantos, J.; Saurí, D. Tourist land use patterns and water demand: Evidence from the Western Mediterranean. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikakou, M.; Chenoweth, J.; Miller, G. Estimating the direct and indirect water use of tourism in the eastern Mediterranean. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 114, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBESTAT. Tourist flux (FRONTUR 2019). Available online: https://ibestat.caib.es (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Marins, S.; Mayer, V.; Fratucci, A.C. Impactos percibidos del turismo: Un estudio comparativo con residentes y trabajadores del sector en Rio de Janeiro-Brasil. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2015, 24, 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Knafou, R. Turismo e território: Por uma abordagem científica do turismo. In Turismo e Geografia: Reflexões Teóricas e Enfoques Regionais; Rodrigues, A.B., Ed.; Hucite: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Sociology beyond Societies: Mobilities for the Twenty-First Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Picornell Bauzà, P. Los impactos del turismo. Pap. Tur. 1993, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, I.; Rullan, O.; Blázquez, M. Las huellas territoriales de deterioro ecológico. El trasfondo oculto de la explosión turística en Baleares. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrónica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2005, 9, 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, C.; Valle, E. An assessment of the impact of tourism in the Balearic Islands. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.M.; Ritchie, B.W. Understanding intergroup conflicts in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 72, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Romero, A.; Blázquez-Salom, M.; Morell, M.; Fletcher, R. Not tourism-phobia but urban-philia: Understanding stakeholders’ perceptions of urban touristification. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2019, 3, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivielso, J.; Moranta, J. The social construction of the tourism degrowth discourse in the Balearic Islands. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1876–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M. Tourism planning and tourismphobia: An analysis of the strategic tourism plan of Barcelona 2010–2015. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2015, 4, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, A.J.; Brown, G. Turismo y Educación (bases para una pedagogía del turismo). Rev. Española Pedagog. 1993, 193, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Shepherd, R. The relationship between tourism education and the tourism industry: Implications for tourism education. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1997, 22, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. Research paradigms and the tourism curriculum. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M. From production line to drama school: Higher education for the future of tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airey, D. Tourism education: Past, present and future. Tur. Posl. 2016, 17, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.D.; Costa, R.A.; Pita, M.; Costa, C. Tourism Education: What about entrepreneurial skills? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 30, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Deale, C.; Goodman, R. Environmental sustainability in the hospitality management curriculum: Perspectives from three groups of stakeholders. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2011, 23, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, V.; Mele, G.; Del Vecchio, P. Entrepreneurship education in tourism: An investigation among European Universities. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2019, 25, 100–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Bañuls, A.; Casado-Díaz, J.M. Capital humano y turismo: Rendimiento educativo, desajuste y satisfacción laboral. Estud. Econ. Apl. 2011, 29, 755–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfors, S.M.; Veliverronena, L.; Grinfelde, I. Developing tourism curriculum content to support international tourism growth and competitiveness: An example from the central Baltic area. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2020, 32, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, E.; Sigala, M. Innovation in hospitality and tourism education. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, G.T.; Clausen, H.B. Fostering innovation competencies in tourism higher education via design-based and value-based learning. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B. Sustainability in hospitality and tourism education: Towards an integrated curriculum. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2011, 23, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Education for Sustainability in Tourism: A Handbook of Processes, Resources and Strategies; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, G.M.; Lockstone-Binney, L.; Ong, F.; Wilson-Evered, E.; Blaer, M.; Whitelaw, P. Teaching sustainability in tourism education: A teaching simulation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H. Global Tourism Higher Education: Past, Present, and Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Velempini, K.; Martin, B. Place-based education as a framework for tourism education in secondary schools: A case study from the Okavango Delta in Southern Africa. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2019, 25, 100–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, L.; Gómez, S. Turismo y Territorio. El Trabajo de campo como estrategia didáctica en la Geografía escolar. Párrafos Geográficos 2009, 8, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, L.C.M.; Peláez, B.F.V.; de la Torre, I.M. Propuesta didáctica para la interpretación del espacio geográfico: La ciudad de Segovia y su entorno. Didáctica Geográfica 2015, 16, 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- Adukaite, A.; Van Zyl, I.; Er, Ş.; Cantoni, L. Teacher perceptions on the use of digital gamified learning in tourism education: The case of South African secondary schools. Comput. Educ. 2017, 111, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; McIntosh, R.W. Tourism components and supply. Tour. Princ. Pract. Philos. 2000, 362–393. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Carr, N.; Cooper, C.P. Managing Educational Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2003; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.D.; Andreassen, H.; O’Donnell, D.; O’Neill, S.; Neill, L. Tourism Education in New Zealand’s Secondary Schools: The Teachers’ Perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2018, 30, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Lew, A.A. Understanding and Managing Tourism Impacts: An Integrated Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P. Tourism Impacts, Planning and Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Edelheim, J. How should tourism education values be transformed after 2020? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mínguez, C.; Martínez-Hernández, C.; Yubero, C. Higher education and the sustainable tourism pedagogy: Are tourism students ready to lead change in the post pandemic era? J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMPACTUR. Estudio del Impacto Económico del Turismo Sobre la Economía y el Empleo de las Illes Balears. EXCELTUR y GOIB. Available online: https://www.exceltur.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IMPACTUR-Baleares-2020.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Coll-Ramis, M.A. Tourism education in Spain’s secondary schools: The curriculums’ perspective. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chili, N. Tourism education: Factors affecting effective teaching and learning of tourism in township schools. J. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A.; O’Relly, A.M.; Brathwaite, R.; Charles, K.R.; Salvaris, C.; Brereton, V. Tourism Education and Human Resource Development for the Decade of the 90’s. In Proceedings of the First Caribbean Conference on Tourism Education, Kingston, Jamaica, 15–17 October 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M. Los temas transversales: Una enseñanza mirando hacia delante. In Los Temas Transversales, Claves de la Formación Integral; Busquets, M.D., Cainzos, M., Fernández, T., Leal, A., Moreno, M., Sastre, G., Eds.; Santillana: Madrid, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, A.; Fernández, G. El medio ambiente en la investigación turística latinoamericana. Biblio3W Rev. Bibliográfica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2002, 7, 418. [Google Scholar]

- Buzo, I. Posición de los contenidos geográficos en la reforma educativa. In La Educación Geográfica Digital; AGE: Zaragoza, Spain, 2012; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Illum, T.; Toke, S. Quality of learning materials. IARTEM E-J. 2017, 9, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcárate, M.D.P.; Serradó, A. Tendencias didácticas en los libros de texto de matemáticas para la ESO. Rev. Educ. 2006, 340, 341–378. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, G.M.; Belver, J.L. El análisis de libros de texto: Una estrategia metodológica en la formación de los profesionales de la educación. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2016, 27, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Díaz, M.; Moreno-Fernández, O.; Rivero-García, A. El cambio climático en los libros de texto de educación secundaria obligatoria. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2020, 25, 957–985. [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel, R. Geoinformación e innovación en la enseñanza-aprendizaje de la geografía: Un reto pendiente en los libros de texto de secundaria. Didáctica Cienc. Exp. Soc. 2013, 27, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, T. The potential of education for creating mutual trust: Schools as sites for deliberation. Educ. Philos. Theory 2011, 43, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, L. Space, Curriculum Space and Morality: About School Geography, Content and Teachers’ Choice. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Serantes-Pazos, A.; Cartea, P.Á.M. El cambio climático en los libros de texto de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria o una crónica de las voces ausentes. Doc. Soc. 2016, 183, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel, R. Del pensamiento espacial al conocimiento geográfico a través del aprendizaje activo con tecnologías de la información geográfica. Giramundo Rev. Geogr. Colégio Pedro II 2016, 2, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, C.M.; Marinas, A.D.I.; Resina, J.P.P.; Cuesta, C.F. El uso de SIG de software libre en una práctica de Biología y Geología de 4º de ESO: Los ecosistemas. Didáctica De Las Cienc. Exp. Soc. 2016, 30, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lázaro, M.L.; De Miguel, R.; Morales, F.J. WebGIS and geospatial technologies for landscape education on personalized learning contexts. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, E.; Hof, A. Promoting spatial thinking and learning with mobile field trips and eGeo-Riddles. In Proceedings of the Creating the GI Society, Berlin, Germany, 2 July 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, C.E.; Wotipka, C.M. History Transformed? Gender in World War II Narratives in US History Textbooks, 1956–2007. Fem. Form. 2011, 23, 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe, N. Geographical information systems for school geography. Geography 2018, 103, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryl, I.; Jekel, T.; Donert, K. GI and spatial citizenship. Learn. GI 2010, 2, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Binimelis, J.; Ordinas, A. Distancia y dirección como parámetros formales en la evaluación de mapas mentales. Los resultados de su aplicación a las islas Baleares (España) en la percepción de los futuros maestros. Investig. Geográficas 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Suresh, M.; Raghu, R. Curriculum agility in higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, A.; Lew, A.A.; Perez, M.S. COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, M.D. Educación, Gobierno Abierto y progreso: Los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS) en el ámbito educativo. Una visión crítica de la LOMLOE. Rev. Educ. Derecho 2021, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Agut, M.P. La Educación para el Desarrollo y la Ciudadanía Global en el Marco de la Cooperación al Desarrollo y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS). Quad. D’animació I Educ. Soc. 2022, 35, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Eade, V.H. Hospitality education in the Dominican Republic. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 1990, 2, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shalem, Y.; Allais, S. Polarity in sociology of knowledge: The relationship between disciplinarity, curriculum, and social justice. Curric. J. 2019, 30, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wineburg, S.S. Historical problem solving: A study of the cognitive processes used in the evaluation of documentary and pictorial evidence. J. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 83, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, K.; Carnicelli, S. Tourism for the emancipation of the oppressed: Towards a critical tourism education drawing on Freirean philosophy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biström, E.; Lundström, R. Textbooks and action competence for sustainable development: An analysis of Swedish lower secondary level textbooks in geography and biology. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelt, N.G. Retos para el sistema educativo en turismo. In Proceedings of the XIV Congress AECIT, Gijón, Spain, 18 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, P.; Séraphin, H.; Chowdhary, N.R. Impacts of COVID-19 on tourism education: Analysis and perspectives. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2021, 21, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, R.; De Lázaro Torres, M.L. WebGIS implementation and effectiveness in secondary education using the digital atlas for schools. J. Geogr. 2020, 119, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J.T.; Gómez, J.I.A. Desarrollo profesional docente ante los nuevos retos de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en los centros educativos. Pixel-Bit. Rev. Medios Educ. 2009, 34, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).