Enhancing Online Instructional Approaches for Sustainable Business Education in the Current and Post-Pandemic Era: An Action Research Study of Student Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

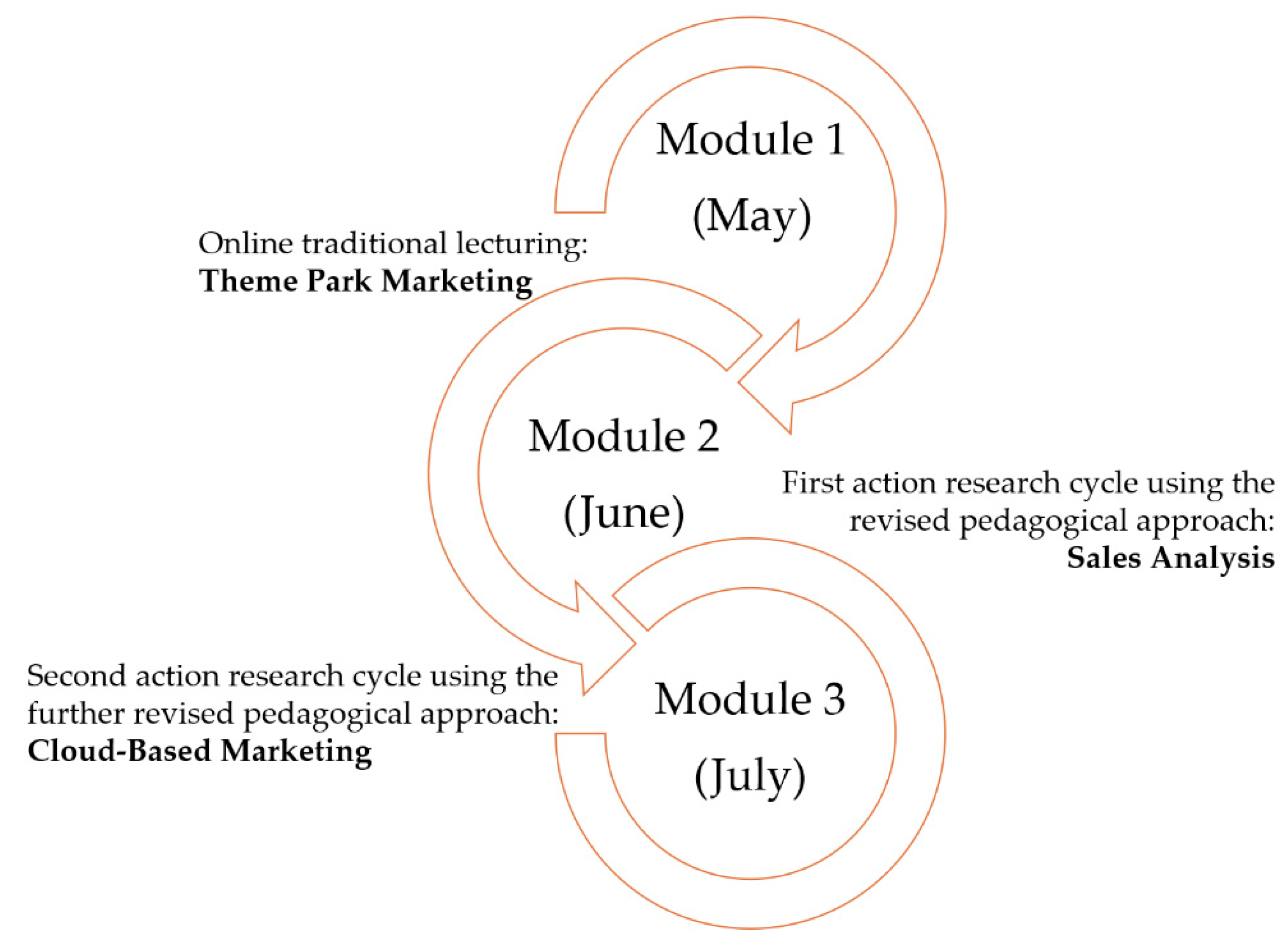

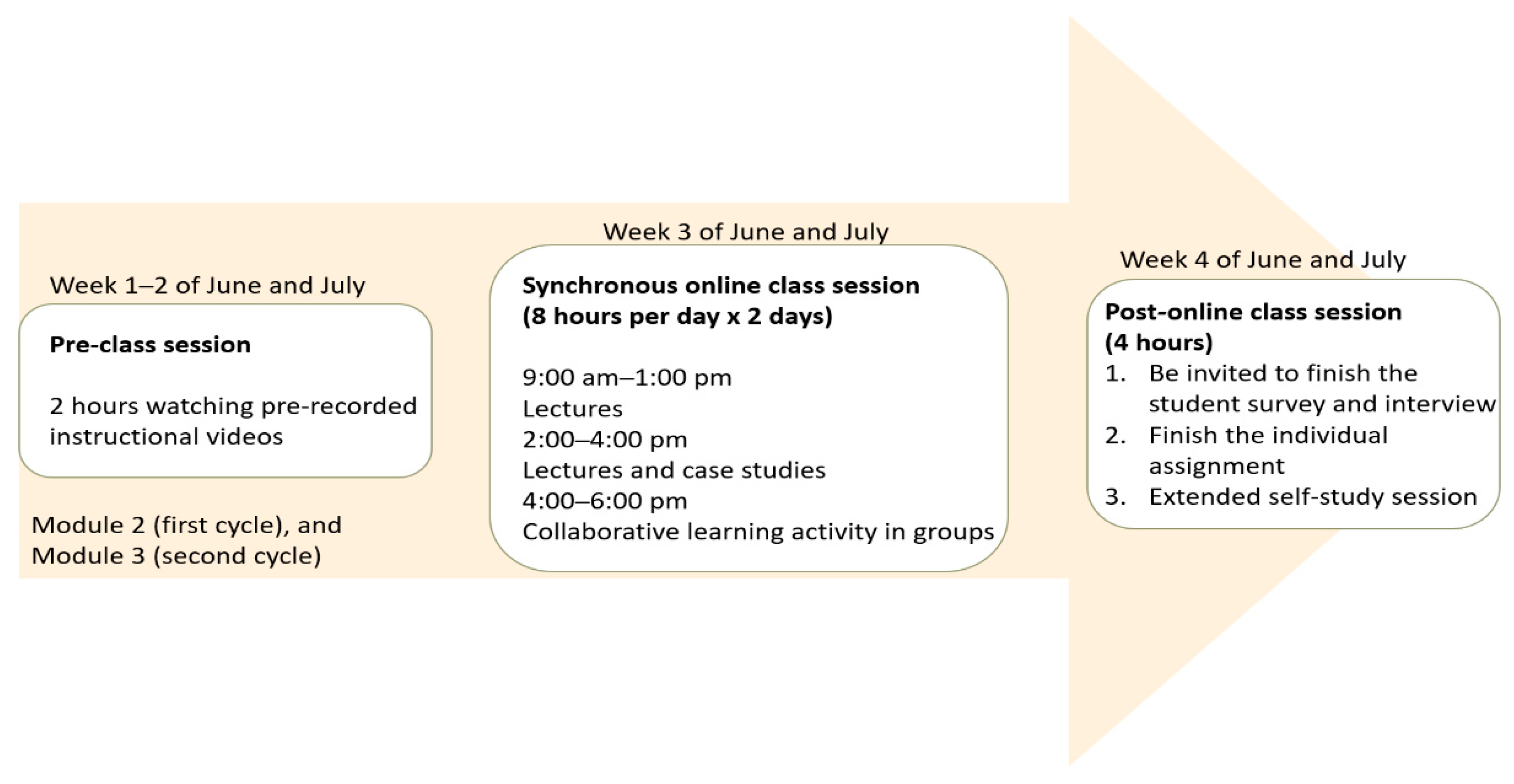

2.1.1. Class and Module Arrangements

2.1.2. Action Research Cycles and Interventions

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3.1. Quantitative Data

2.3.2. Qualitative Data

2.3.3. Qualitative Content Analyses

- Concept-driven: We derived themes and subcategories from the literature on the current state of research and the RQs.

- Data-driven: We completed a stage-by-stage procedure by opening and developing top- and sub-level codes until achieving saturation and continuously organising and systematising the formed codes at different levels with the new incoming data.

- Mixed: We took these concept-driven themes and subcategories and subsequently coded all data accordingly with new generations of specific themes and subcategories when needed.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Two Action Research Cycles

3.2. Implementation Improvement after the Two Action Research Cycles

3.3. Quantitative Results

3.4. Qualitative Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficacy of Current Online Pedagogical Approaches (RQ1)

4.2. Efficacy Improvement of Online Pedagogical Approaches (RQ2)

4.3. Practical Framework for Online Pedagogical Approaches (RQ3)

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Aspect | Questions |

|---|---|

| Perceived learning (Q1–3) |

|

| Behavioural engagement (Q4–8) |

|

| Emotional engagement (Q9–13) |

|

| Cognitive engagement (Q14–17) |

|

| Open-ended question |

|

References

- Peters, M.A.; Rizvi, F.; McCulloch, G.; Gibbs, P.; Gorur, R.; Hong, M.; Hwang, Y.; Zipin, L.; Brennan, M.; Robertson, S.; et al. Reimagining the New Pedagogical Possibilities for Universities Post-Covid-19. Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 54, 717–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Geng, X.; Wang, Q. Sustainable Development of University EFL Learners’ Engagement, Satisfaction, and Self-Efficacy in Online Learning Environments: Chinese Experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divaharan, S.; Chia, A. Blended Learning Reimagined: Teaching and Learning in Challenging Contexts. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgarten, J. Evidence on Efforts to Mitigate the Negative Educational Impact of Past Disease Outbreaks. 2020. Available online: opendocs.ids.ac.uk (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Kuhfeld, M.; Soland, J.; Tarasawa, B.; Johnson, A.; Ruzek, E.; Liu, J. Projecting the Potential Impact of COVID-19 School Closures on Academic Achievement. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, Q.; Hong, X. Implementation and Challenges of Online Education during the COVID-19 Outbreak: A National Survey of Children and Parents in China. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 61, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Education Development in China: Education Return, Quality, and Equity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, C. Suspending Classes without Stopping Learning: China’s Education Emergency Management Policy in the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Liu, S.; Ismat, H.I.; Tsegay, S.M. Choice of Higher Education Institutions: Perspectives of Students from Different Provinces in China. Front. Educ. China 2017, 12, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chan, M.C.E.; Kang, Y. Post-Pandemic Reflections: Lessons from Chinese Mathematics Teachers about Online Mathematics Instruction. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, A. Blended Learning and Flipped Classroom Approaches. Am. Res. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdamli, F.; Asiksoy, G. Flipped Classroom Approach. World J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotellar, C.; Cain, J. Research, Perspectives, and Recommendations on Implementing the Flipped Classroom. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehling, P.V.; Root Luna, L.M.; Richie, F.J.; Shaughnessy, J.J. The Benefits, Drawbacks, and Challenges of Using the Flipped Classroom in an Introduction to Psychology Course. Teach. Psychol. 2017, 44, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Eliyahu, A. Sustainable Learning in Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurukkal, R. Techno-Pedagogy Needs Mavericks. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S. Gamification in Management: Between Choice Architecture and Humanistic Design. J. Manag. Inq. 2018, 28, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z. Students’ Learning Performance and Perceived Motivation in Gamified Flipped-Class Instruction. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfred, C.; Kemmis, S. Becoming Critical: Education Knowledge and Action Research; Routledge Farmer, Taylor & Francis Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C.K. Toward a Flipped Classroom Instructional Model for History Education: A Call for Research. Int. J. Cult. Hist. EJournal 2017, 3, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Government. Accreditation of Academic and Vocational Qualifications (HKCAAVQ). Available online: https://www.hkqf.gov.hk (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Abeysekera, L.; Dawson, P. Motivation and Cognitive Load in the Flipped Classroom: Definition, Rationale and a Call for Research. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiff, J. Editorial: Higher Education Research and Scholarship Group Special Issue: Action Research in Higher Education. Stud. Engagem. Exp. J. 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.-K.; Lo, C.-K. Online Flipped and Gamification Classroom: Risks and Opportunities for the Academic Achievement of Adult Sustainable Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Hew, K.F. A Comparison of Flipped Learning with Gamification, Traditional Learning, and Online Independent Study: The Effects on Students’ Mathematics Achievement and Cognitive Engagement. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.; Furrer, C.; Marchand, G.; Kindermann, T. Engagement and Disaffection in the Classroom: Part of a Larger Motivational Dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.T.H.; Wylie, R. The ICAP Framework: Linking Cognitive Engagement to Active Learning Outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 49, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. And Sex and Drugs and Rock’n’Roll. Pflege 2014, 27, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, A.M. From Passive to Active: The Impact of the Flipped Classroom through Social Learning Platforms on Higher Education Students’ Creative Thinking. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 46, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thyer, B.A. The Scientific Value of Qualitative Research for Social Work. Qual. Soc. Work Res. Pract. 2012, 11, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, B.; Feldman, T.; Cain, C.; Leesman, L.; Hood, C. Defining and Navigating “Action” in a Participatory Action Research Project. Educ. Action Res. 2019, 28, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, B.; Clark, D. An Examination of Student Preference for Traditional Didactic or Chunking Teaching Strategies in an Online Learning Environment. Res. Learn. Technol. 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Hense, J.U.; Mayr, S.K.; Mandl, H. How Gamification Motivates: An Experimental Study of the Effects of Specific Game Design Elements on Psychological Need Satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Hew, K.F. Implementing a Theory-Driven Gamification Model in Higher Education Flipped Courses: Effects on Out-of-Class Activity Completion and Quality of Artifacts. Comput. Educ. 2018, 125, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhash, S.; Cudney, E.A. Gamified Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichev, C.; Dicheva, D.; Irwin, K. Gamifying Learning for Learners. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.J.R.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Leal, C.T.P. Gamification in Management Education: A Systematic Literature Review. BAR-Braz. Adm. Rev. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.-K.; Lo, C.-K. Flipped Classroom and Gamification Approach: Its Impact on Performance and Academic Commitment on Sustainable Learning in Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotgans, J.I.; Schmidt, H.G.; Rajalingam, P.; Hao, J.W.Y.; Canning, C.A.; Ferenczi, M.A.; Low-Beer, N. How Cognitive Engagement Fluctuates during a Team-Based Learning Session and How It Predicts Academic Achievement. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2017, 23, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijs, D.; Rumyantseva, N. Coopetition in Education: Collaborating in a Competitive Environment. J. Educ. Chang. 2013, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quay, J.; Gray, T.; Thomas, G.; Allen-Craig, S.; Asfeldt, M.; Andkjaer, S.; Beames, S.; Cosgriff, M.; Dyment, J.; Higgins, P.; et al. What Future/S for Outdoor and Environmental Education in a World That Has Contended with COVID-19? J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2020, 23, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Hew, K.F. Design Principles for Fully Online Flipped Learning in Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review of Research during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A Systematic Review of Immersive Virtual Reality Applications for Higher Education: Design Elements, Lessons Learned, and Research Agenda. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, G.B.; Petkakis, G.; Makransky, G. A Study of How Immersion and Interactivity Drive vr Learning. Comput. Educ. 2022, 179, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Sample Question | Supporting Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived learning (Q1–3) | I learnt more because of the online class format (Q2) | [24] |

| Behavioural engagement (Q4–8) | I paid attention to my studies (Q7) | [25] |

| Emotional engagement (Q9–13) | I felt interested when we worked on something in class (Q10) | [26] |

| Cognitive engagement (items 14–17) | I made a lot of effort (Q15) | [27] |

| Aspect | Sample Question |

|---|---|

| Challenge |

|

| Problem |

|

| Benefit |

|

| Solution |

|

| Stage | First Action Research Cycle (OFC) | Second Action Research Cycle (OGC) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-class session |

|

|

| Online class session |

|

|

| Post-online class session |

|

|

| Key challenges |

|

|

| Screenshot examples of the online class sessions |  |  |

| Game Element | Purpose | Award Criteria |

|---|---|---|

Point | Granular feedback to encourage participation in learning tasks and activities | Award to activity groups in the collaborative learning activity session, encouraging innovative ideas and solutions. One point is given to one innovative idea or solution. |

Leaderboard | Encourages intragroup collaborative learning and healthy intergroup competition between the activity groups when learners try to obtain more points for a prominent position on the leaderboard | All activity groups were ranked on the leaderboard based on the total number of points accumulated in each online class session. |

| Survey Item | Survey Question | OFC Mean (SD) | OGC Mean (SD) | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived learning | Q2. I learnt more because of the classroom format | 3.53 (0.77) | 4.67 (0.53) | 10.63 | <0.001 |

| Behavioural engagement | Q7. I paid attention to my studies | 4.22 (0.51) | 4.47 (0.64) | 2.67 | <0.001 |

| Emotional engagement | Q9. I felt good when I studied | 3.89 (0.60) | 4.53 (0.64) | 6.36 | <0.005 |

| Q10. I felt interested when we worked on something in class | 3.92 (0.54) | 4.54 (0.58) | 6.82 | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive engagement | Q15. I made a lot of effort | 3.96 (0.53) | 4.50 (0.55) | 6.16 | <0.001 |

| Class | n | Grade B or Higher (Merit) | Grade B or Lower (Pass) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTC | 78 | 82.0% | 18.0% |

| OFC | 76 | 81.6% | 18.4% |

| OGC | 76 | 82.8% | 17.2% |

| Concept Theme | Subcategory | Response Sample | Key Component | Improvement Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexibility (61 quotes, 17%) | Adapting to the switch between online and offline classrooms | ‘The students could switch to online learning during the campus lockdown’ (T-1) ‘The flexible online and offline classroom arrangements were great and helpful for our class management’ (TA-1) ‘It was important to allow us to continue our studies, even during the pandemic lockdowns. We could have online resources to prepare ourselves while waiting to attend the online classes or campus classes when our campus was allowed to open’ (S-13) | Online and offline learning | Technical network and online support |

| All-in-inclusive (104 quotes, 28%) | Inability to capture the students’ attention and participation in the lessons for long hours of online class sessions | ‘Unlike traditional classroom instruction, it was not possible to approach and observe the students on the learning platform, especially when they all turned off their cameras even after asking them to turn on’ (T-1) ‘The students would only start discussing topics when the teacher entered the virtual subgroup chatrooms’ (TA-3) ‘I saw one of my classmates still eating snacks while the teacher asked him to answer a question’ (S-15) | Asynchronous self-study and synchronous online class session | Gamifying the classes |

| Lacking interactions, exchanges and sharing experiences throughout the learning process | ‘I very often received no responses when I asked questions during the online class sessions’ (T-2) ‘The online class sessions were very dull with a slow teaching pace because our teacher often asked questions and waited for answers’ (S-15) | Real-time communication and fewer delays | Technical networks and online support | |

| Difficulties in monitoring and managing the students’ learning progress | ‘I was unable to identify and track my student’s understanding of the instructional content because seeing them on screen was different from face-to-face teaching’ (T-3) ‘I had to remind the students to submit their homework on time in the LMS repeatedly because I never received any of their replies’ (TA-2) ‘I might finish my homework and assignments on time if I knew how my classmates were progressing’ (S-7) | LMS and social media platforms (e.g., Qitoupiao, WeChat) | Learning community and study groups | |

| Feeling lonely and helpless in their learning and studies | ‘Help and assistance were not immediately available when I experienced problems, questions and uncertainties in my study’ (S-17) | |||

| Competitive learning (86 quotes, 23%) | Learning from teachers and classmates (Collaborative learning) | ‘As a teacher, I must organise more class activities, especially for online classes’ (T-3) ‘The students in online classes were not as active during exchanges as in traditional face-to-face classrooms’ (TA-2) ‘I was not interested in taking part in the class activities, especially for online classes, because it was not like being in a real classroom’ (S-18) | Game elements (i.e., points and leaderboards) were used as granular and accumulated feedback to motivate students’ learning interactions and collaborations | Gamification and motivation |

| Pursuing better learning performance than other classmates in the class (Competitive learning) | ‘The students worked hard in learning but were less willing to share their experiences in online class sessions’ (T-1) ‘The students always wanted to win against each other but were not always willing to share and help each other’ (TA-2) ‘I was afraid that my experience and knowledge were not as good as my classmates’ own experiences and expertise (S-13) | Leaderboard rankings promoted healthy intragroup collaborative and intergroup competitive learning | Collaborative and competitive learning | |

| Technical support (36 quotes, 10%) | The need for help and support in using distinct functions in the online instruction platform | ‘It was the first time I had to instruct in front of a computer screen. I was struggling and felt helpless when I had problems using the online applications’ (T-2) | Professional training for online instruction | Technical support and professional training |

| ‘I provided pre-recorded instructional videos and put them on the LMS, but I felt that that the instructional contents should be presented differently online than in traditional classrooms’ (T-3) | Smooth video streaming and live broadcasting | |||

| ‘I cannot get used to the technical stuff, such as how to reset hanging videos’ (TA-1) | Desktop and mobile compatibility | |||

| ‘There were too many disconnections, and I needed to log in repeatedly, which was so distracting and annoying’ (S-7 and S-12) | Network and connection | |||

| Difficulties in planning and integrating multimedia resources into online teaching practice | ‘It was new to me to use multimedia and digital applications to teach the classes, especially in the online class sessions’ (T-2 and T-3) | Technical support and training (i.e., skills and techniques in using technologies) | ||

| Sustainable learning (81 quotes, 22%) | Continue the educational progress during pandemic lockdowns and after synchronous online class sessions | ‘The classes could still progress, although more slowly, which is better than completely halting all classes during city lockdowns’ (T-1) ‘If all the classes stopped for months, there would be great pressure to rearrange class timetables after reopening of the campus’ (TA-3) ‘I could continue my study during the home confinement and the uncertain period following campus lockdowns’ (S-12) | Student connection and learning continuity | Establishment of a learning community and study groups |

| The pedagogy should be sustained and welcomed by the participants | ‘The most important consideration of online pedagogies should be how well the students like to use it to learn over the long time’ (T-2) ‘In-person interaction (further explained as personal presence) is very important for online class sessions because many students turned on their camera but were not listening’ (TA-3) ‘I did not have the in-person feeling of on-site presence as learning in the traditional classroom, after the lessons moved online’ (S-7) | Creation of more immersive and participative learning spaces | Immersive VR applications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ng, L.-K.; Lo, C.-K. Enhancing Online Instructional Approaches for Sustainable Business Education in the Current and Post-Pandemic Era: An Action Research Study of Student Engagement. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010042

Ng L-K, Lo C-K. Enhancing Online Instructional Approaches for Sustainable Business Education in the Current and Post-Pandemic Era: An Action Research Study of Student Engagement. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleNg, Lui-Kwan, and Chung-Kwan Lo. 2023. "Enhancing Online Instructional Approaches for Sustainable Business Education in the Current and Post-Pandemic Era: An Action Research Study of Student Engagement" Education Sciences 13, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010042

APA StyleNg, L.-K., & Lo, C.-K. (2023). Enhancing Online Instructional Approaches for Sustainable Business Education in the Current and Post-Pandemic Era: An Action Research Study of Student Engagement. Education Sciences, 13(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010042