Inside Out: A Scoping Review on Optimism, Growth Mindsets, and Positive Psychology for Child Well-Being in ECEC

Abstract

1. Introduction

True social and emotional learning for children, parents, and teachers is not a process of bringing something from the outside in, but rather bringing something from the inside out. It is not just learning prescribed social skill sets, but more importantly tapping into strength-based mindsets… The early childhood years are the incubator (p. 29).

1.1. Well-Being in ECEC

1.2. Positive Psychology

1.3. Explanatory Styles and Young Children’s Well-Being

1.3.1. Growth Mindset

1.3.2. Optimism

1.3.3. The Influence of Parental Explanatory Styles

1.4. Criticism towards the Theories of Positive Psychology, Growth Mindsets, and Optimism

1.5. Rationale and Objectives of This Study

- What is the extent of the existing literature on optimism, growth mindset, and positive psychology for young children’s well-being in ECEC settings?

2. Methods

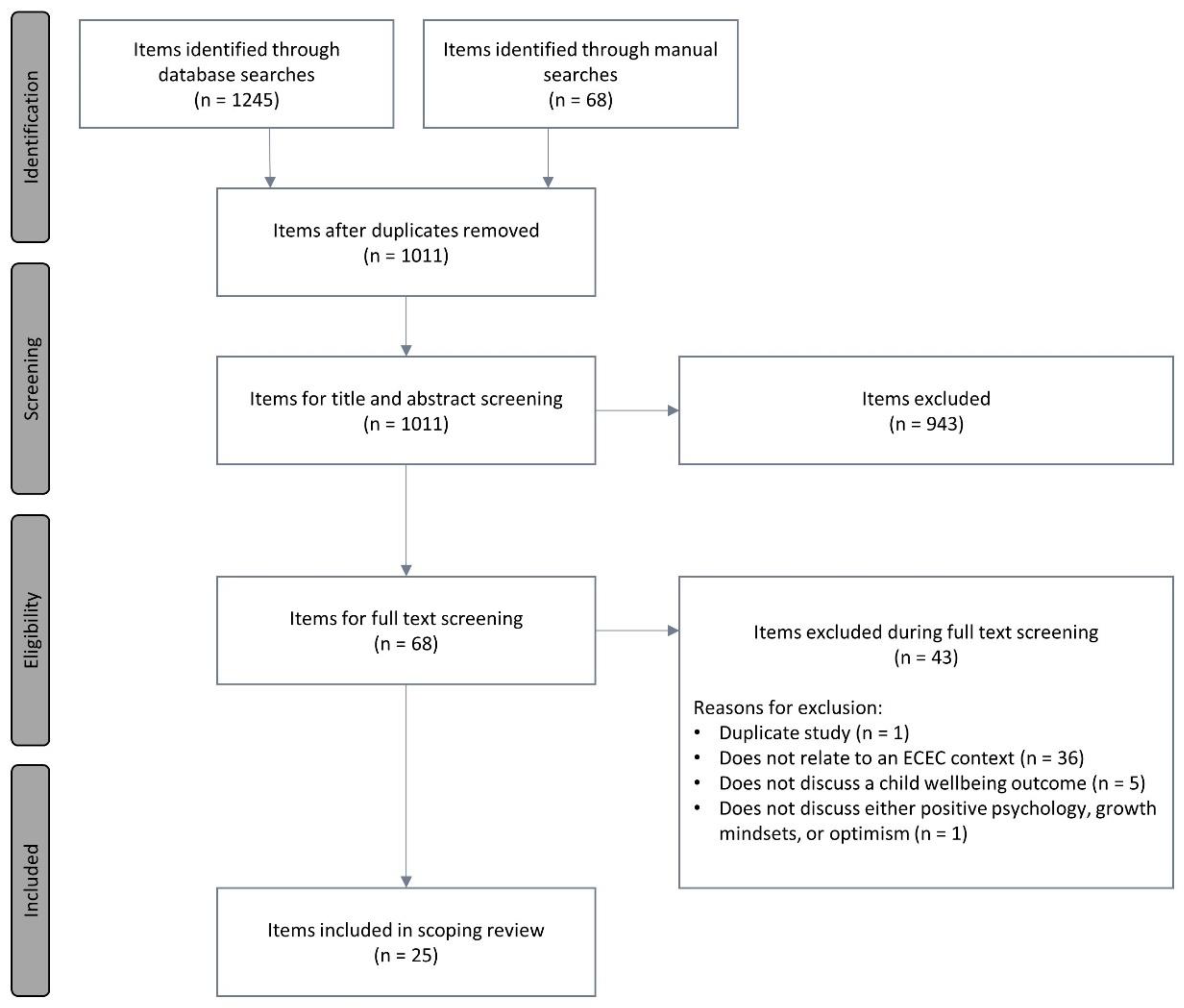

2.1. Systematic Review Design and Search Process

2.2. Study Screening and Eligibility

- Publication since 1995

- ECEC context

- Outcomes for children up to 7 years old

- At least one child well-being outcome

- Discusses either growth mindsets, optimism, or positive psychology

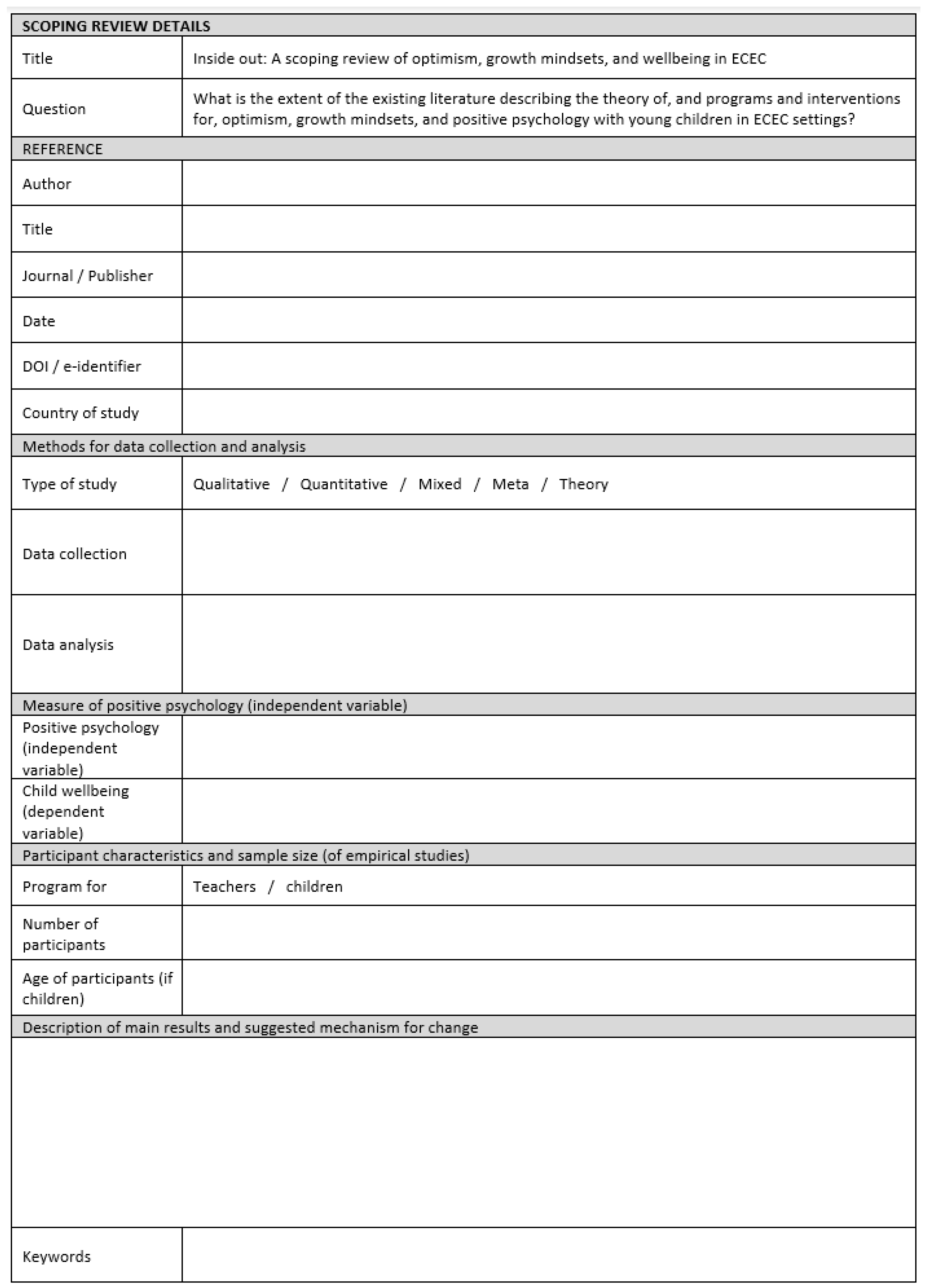

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

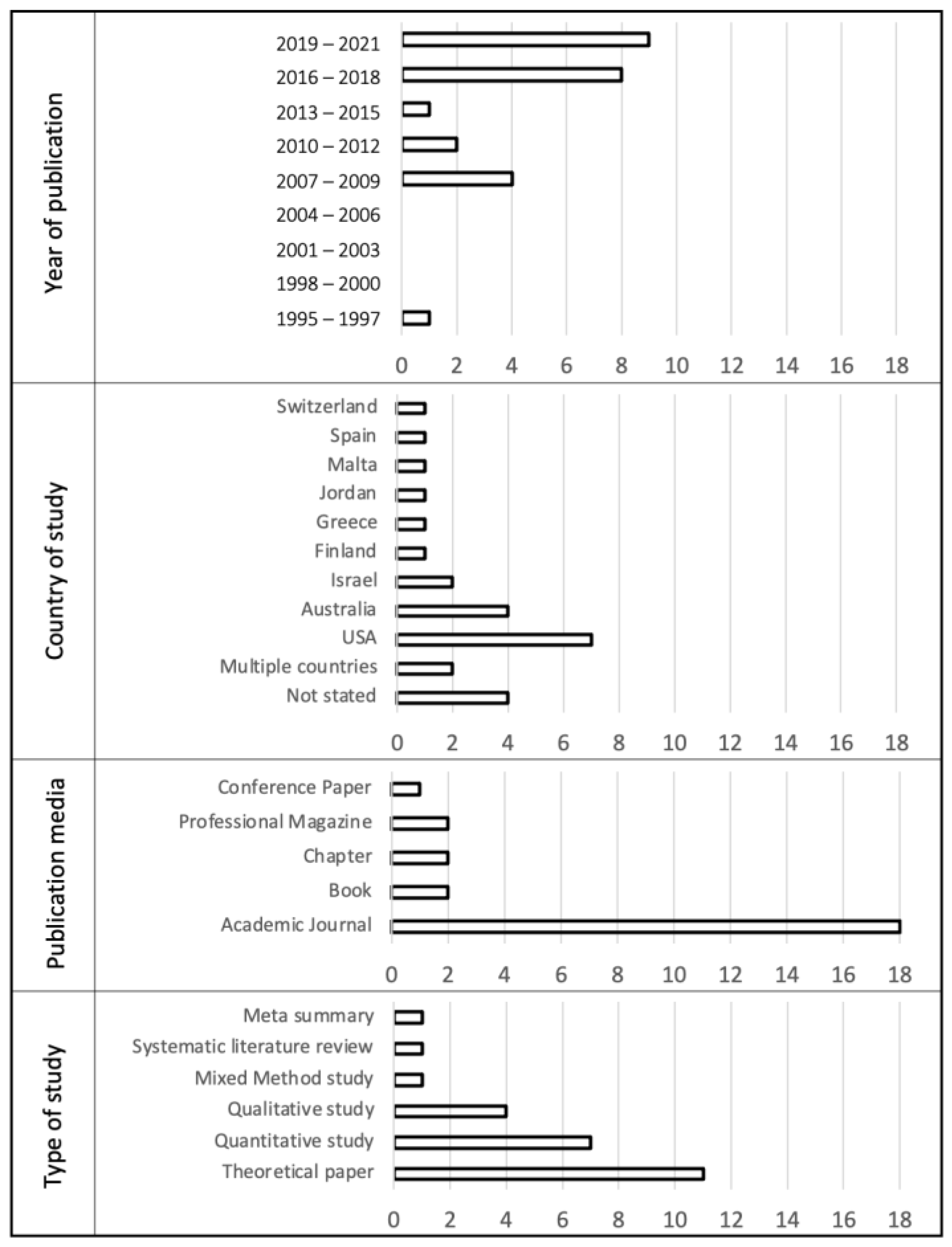

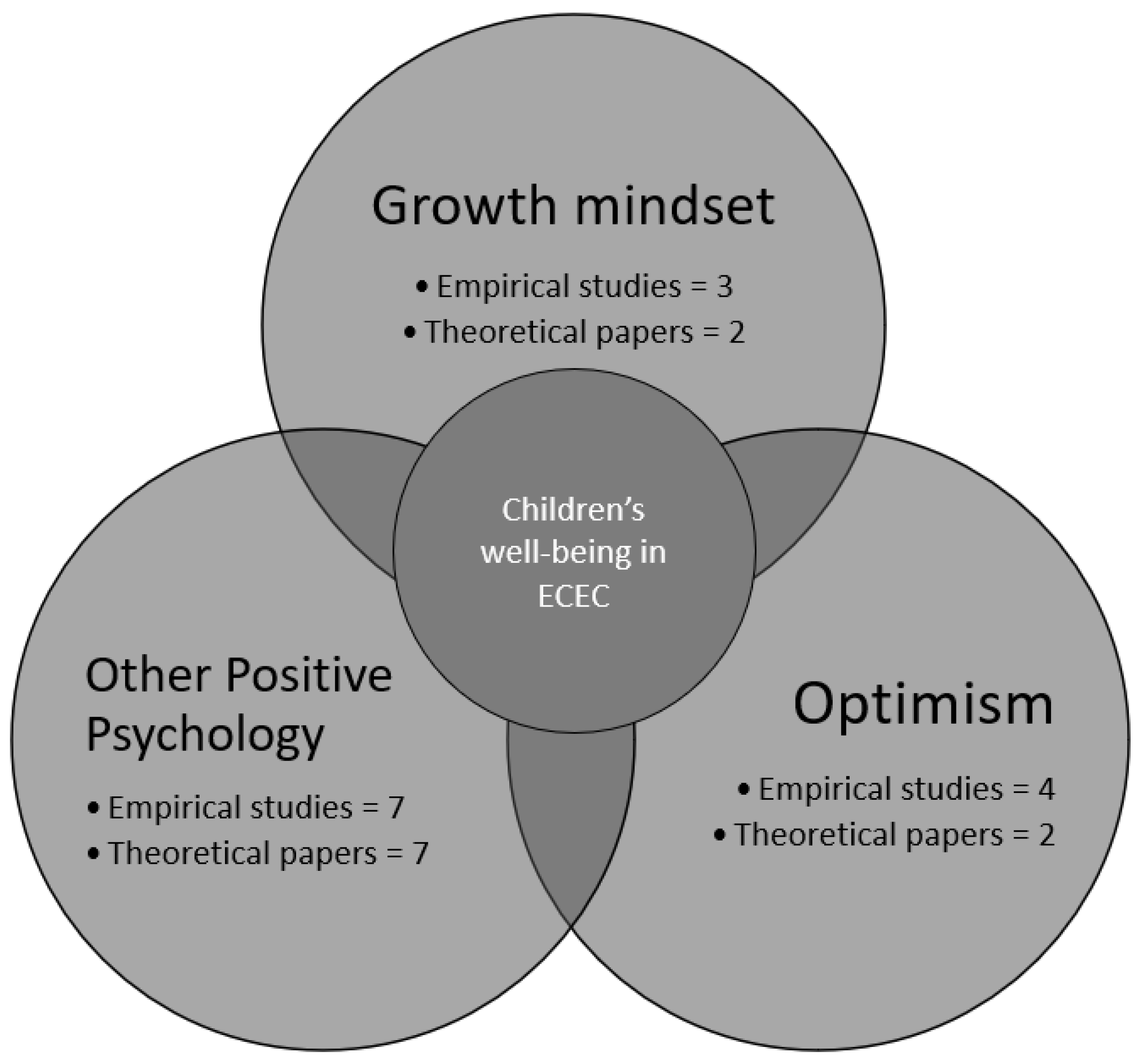

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

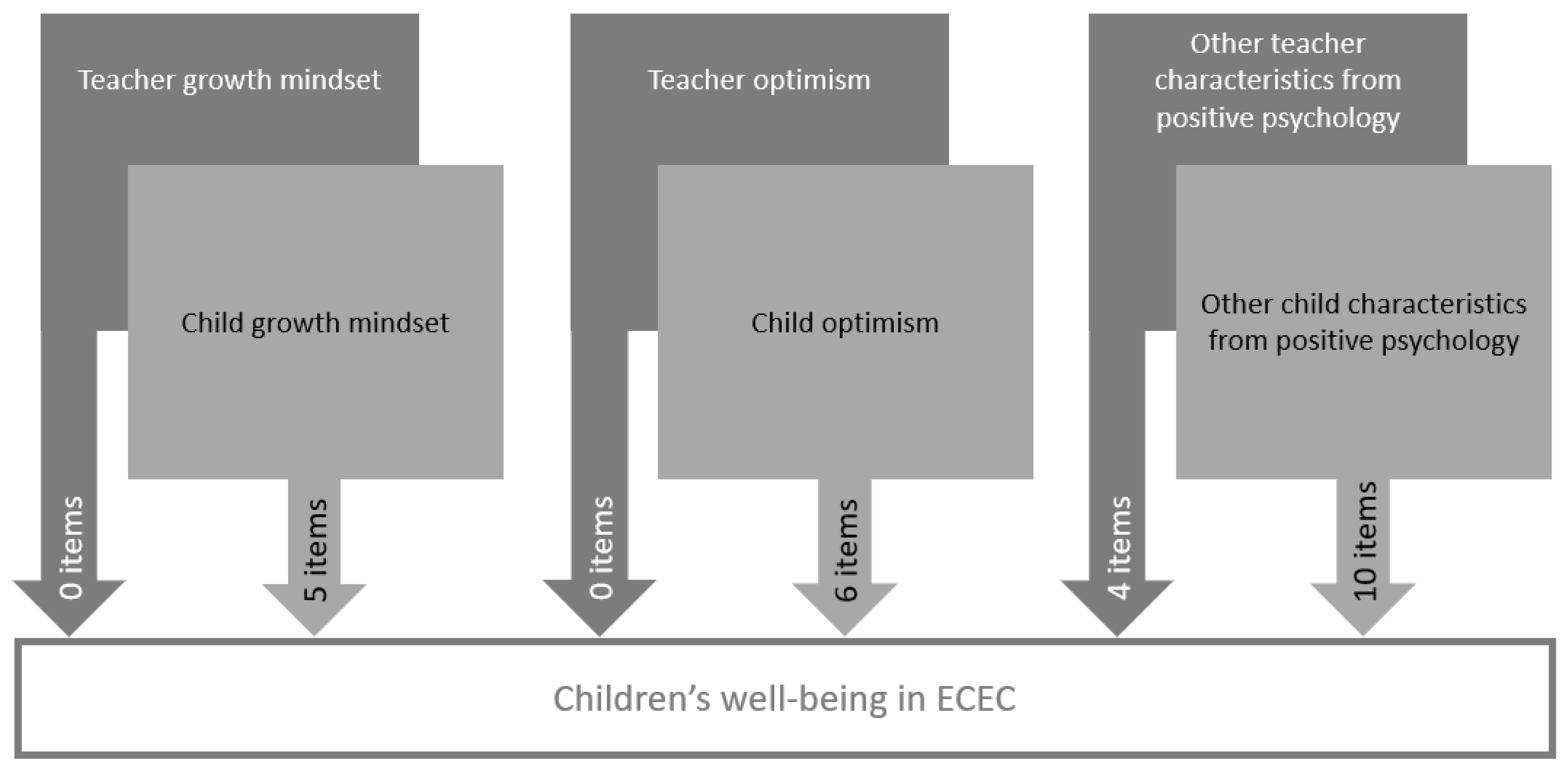

3.2. Reported Positive Psychology and Child Well-Being Attributes

3.3. Suggested Mechanisms of Change

the way adults respond to emotions expressed by each other is a living demonstration for children of how to build caring interactions with other people… With positive adult role models to follow, children as young as one year of age learn pro-social behaviour… Compassionate adults working with children not only model caring behaviour, but they are able to create better functioning organisations in which all members feel included. In such organisations, psychological safety is improved, positive emotions such as gratitude are evoked, [and] anxiety is reduced (p. 164).

4. Discussion

4.1. Limited Evidence, Broad Theory

4.2. The Influence of ECEC Teacher’s Explanatory Styles

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Search Strings

- ERIC & Academic Search Premier

- PsycINFO & PROQUEST Dissertations and Theses

- SCOPUS

- The Journal of Positive Psychology, The International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, & Journal of Positive School Psychology

- The European Journal of Applied Positive Psychology

- The Cochrane database of systematic reviews

- Campbell Systematic Reviews & JBI Evidence Implementation

Appendix B

Data Extraction Template

Appendix C

Included Items

| Authors (Year) | Type of Study, Publication | Country | Phenomena of Interest | Positive Psychology Keywords | Child Well-Being Outcome Keywords |

| Al-Mohtadi, Aldarab’h, & Gasaymeh (2015) [60] | Quantitative, Journal Article | Jordan | Programs aimed at increasing optimism in young children, are positively associated with learning, mastery, positive self-concept, happiness, and health. | optimism | learning, mastery, happiness, empathy, psychological health |

| Alzina & Paniello (2017) [61] | Theory, Journal Article | Spain | Training teachers in emotional education (positive psychology, emotional intelligence, emotional competencies, optimism, drawing attention to positive aspects of human functioning) so they can train children in the same, is associated with improvements in social well-being, personal well-being, and a culture of well-being in children. | emotional intelligence, optimism, mindfulness, character strengths | social competency, emotional competency, flourishing |

| Armstrong, Missall, Shaffer, & Hojnoski (2009) [62] | Theory, Book chapter | Not stated | Early educator and parent support that promotes positive adaptation, social and individual skills for adapting, interacting, and learning, is associated with happiness, well-being, and better positive adaptation to new scenarios in children. ECEC is particularly important for positive adaptation skills for school readiness. | positive adaptation, social skills, positive interactions, character strengths | happiness, adaptability, school readiness |

| Baker, Green, & Falecki (2017) [14] | Theory, Journal Article | Multiple countries | How positive psychology (emotional capital) contributes to resilience and well-being in educators, and play, curiosity, learning, happiness, flow, and healthy relationships in children. ECEC professional well-being (organisational) benefits all. | emotional capital | resilience, learning, flourishing, flow, curiosity |

| Boylan, Barblett, & Knaus (2018) [25] | Mixed method, Journal Article | Australia | Teachers’ perspectives on how growth mindset (resilience, critical thinking, creativity, 21st century skills, intrinsic motivational orientations) in children in ECEC are important for children’s autonomy, learning, and positive lifelong learning habits. | growth mindset, resilience, creativity, critical thinking, intrinsic motivation | autonomy, learning, agency, taking on challenges |

| Cefai, Arlove, Duca, Galea, Muscat, & Cavioni (2018) [53] | Quantitative, Journal Article | Malta | Activities developed by teachers in ECEC classrooms to teach and promote growth mindset, strengths, self-determination, and communication skills, and their association with increased resilience, academic success, learning engagement, prosocial behaviour, and social and emotional well-being. | growth mindset, character strengths, communication skills | resilience, academic achievement, learning, prosocial behaviour |

| Compagnoni, Karlen, & Maag (2019) [56] | Quantitative, Journal Article | Switzerland | An examination of the structure of children’s mindset orientation in ECEC, and how it is related to behavioural self-regulation, successful adaptation, and pre-academic achievement. | growth mindset, goal orientation | self-regulation, adaptability, academic achievement |

| Diesendruck & Lindenbaum (2009) [63] | Quantitative, Journal Article | Israel | How children’s individual stable trait theories of positive attributes are related to prosocial behaviour, social interactions, adaptability, and the absence of helplessness | optimism | prosocial behaviour, positive interactions, absence of helplessness, adaptability |

| Enriquez, Clark, & Calce (2017) [54] | Theory, Journal Article | Not stated | How growth mindset language employed by teachers within a dynamic learning framework, is related to learning, worldview, broad perspectives, belief in the possibility of positive change, social imagination, and taking on challenges in kindergarten children. | growth mindset | learning, taking on challenges, belief in possible change, social imagination |

| Frydenberg, Deans, & Liang (2020) [8] | Theory, Book | Multiple countries | How teachers’ knowledge of a combination of positive psychology attributes (gratitude, grit, mindsets, meaning, positive affect, mastery, self-efficacy, coping) will help their interactions with children and result in improved physical health, social competence, emotional maturity, communication skills, flourishing, and resilience in children. | gratitude, grit, growth mindset, positive affect, mastery, self-efficacy, coping | healthy life, social competency, emotional maturity, communication skills, flourishing, resilience |

| Haslip, Allen-Handy, & Donaldson (2019) [59] | Qualitative, Journal Article | USA | How ECEC educators practice the character strengths of love, kindness, forgiveness, and caring behaviour, and how they observe those traits in children, and the relationship this has with children’s success in school, social life, and prosocial competency. | character strengths, love, kindness, forgiveness | school readiness, social competency, attachment |

| Hawkes (1995) [64] | Theory, Conference Paper | USA | How teachers’ knowledge of, and modelling of, internal locus of control (belief that effort is a major determinant of success, ability to develop, grow, and work independently) positively impacts on children’s self-concept, affective aspects of personality, and positive feeling of self. | locus of control | positive view of self, self esteem |

| Hopps-Wallis, Fenton, & Dockett (2016) [65] | Qualitative, Journal Article | Australia | How strength-based practices and especially strengths identification by teachers (as communicated from ECEC teachers to primary teachers), contribute to positive transitions and school readiness in children. | character strengths | positive transitions, school readiness |

| Koralek & Colker (2019) [29] | Theory, Book | USA | How teachers can teach optimism to young children, and how that will improve children’s healthy lives, school success, resilience, gratitude, happiness, and kindness. | optimism | healthy lives, school readiness, resilience, gratitude, happiness, kindness |

| Lottman, Zawaly, & Niemiec (2017) [11] | Theory, Book Chapter | USA | How teachers can develop skills in themselves to naturally identify and promote the unique constellation of emergent character strengths in the young child. How that can lead to improvements in prosocial behaviour, social intelligence, positive identity development, and creativity. | character strengths, growth mindset | prosocial behaviour, social intelligence, positive view of self, creativity |

| Oorloff, Rooney, Baughman, Kane, McDevitt, & Bryant (2021) [57] | Quantitative, Journal Article | Australia | How teachers can teach optimism to children (with the “I Spy Feelings Optimism program”), and how this is associated with improvements in emotion regulation, coping, and mental health in children. | optimism | emotional regulation, coping, character strengths, mental health |

| Owens & Waters (2020) [66] | Meta summary, Journal Article | Not stated | How early interventions with positive psychology have a positive association with strength, positive life trajectory, positive emotions, and social competence. | character strengths, hope, gratitude | taking on challenges, strength, positive life trajectory, positive emotions, social competency |

| Pawlina & Stanford (2011) [55] | Theory, Professional Magazine | USA | How teachers’ words promoting a growth mindset are associated with children’s resiliency and effective problem solving. | growth mindset | resilience, problem solving |

| Sagor (2008) [58] | Theory, Professional Magazine | USA | How optimism that is nurtured by teachers is associated with positive feelings about the future, perseverance, and efficacy. | optimism | positive feelings about future, perseverance, efficacy |

| Shin, Vaughn, Akers, Kim, Stevens, Krzysik, et al. (2011) [67] | Quantitative, Journal Article | USA | That children who express and experience positive affect and happiness more frequently, will also experience more peer acceptance, better social interaction, better adjustment, and more emotional regulation. | positive affect, happiness | peer acceptance, positive interactions emotional regulation, adjustment, social competency |

| Shoshani & Slone (2017) [12] | Quantitative, Journal Article | Israel | How a positive education program in preschool, focusing on positive emotions, regulation, empathy, positive thinking, engagement, social relationships, and goal identification, is positively associated with learning behaviour, mental health, adaptive functioning, and subjective well-being. | positive emotions, self-regulation, empathy, positive thinking, prosocial behaviour, goal orientation | learning, positive emotions, mental health, adaptability, happiness |

| Vuorinen, Pessi, & Uusitalo (2021) [38] | Theory, Journal Article | Finland | How compassion in ECEC teachers results in better functioning organisations, psychological safety in the workplace, positive emotions in the organisation, less stress and anxiety, and improved attachment and commitment to the work, which in turn is associated with better prosocial behaviour, closer relationships, less bullying, more self-confidence, and better school adaption in children | compassion | prosocial behaviour, positive relationships, less bullying, self-confidence, school readiness |

| Waters & Loton (2019) [68] | Systematic review, Journal Article | Not stated | How children’s strengths, emotional management, gratitude, attention and awareness, mindfulness, relationships, coping, resilience, and self-regulation are positively associated with their mental health, academic performance, motivation | character strengths, emotional management, attention, prosocial behaviour, coping, goal orientation | mental health, academic achievement, motivation |

| Waters, Dussert, & Loton (2021) [69] | Qualitative, Journal Article | Australia | Children’s concepts of their own well-being. How addressing the deficit focus and lack of child voice in ECEC about their own well-being can improve their well-being. | prosocial behaviour | resilience, thriving |

| Zafiropoulou & Thanou (2007) [7] | Qualitative, Journal Article | Greece | How children’s optimism, explanatory styles, mastery, positivity, and lack of helplessness, is positively associated with awareness, ability to identify thought, positive emotions, behaviour management, intentional behaviour towards challenges, and adaptability | optimism, explanatory style, mastery, positivity | awareness, positive emotions, learning, prosocial behaviour, taking on challenges |

References

- Jones, D.; Greenberg, M.; Crowley, M. Early social-emotional functioning, and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, J. Cascades of infant happiness: Infant positive affect predicts childhood IQ and adult education. Emotion 2020, 20, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, K.; Dweck, C. The relation between motivational patterns and achievement cognitions through the elementary school years. Merrill-Palmer Q. 1995, 41, 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. The Optimistic Child; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. Mindset: Changing the Way You Think to Fulfil Your Potential; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. Learned Optimism; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zafiropoulou, M.; Thanou, A. Laying the foundations of well being: A creative psycho-educational program for young children. Psychol. Rep. 2007, 100, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydenberg, E.; Deans, J.; Liang, R. Promoting Well-Being in the Pre-School Years: Research, Applications and Strategies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lottman, T.; Zawaly, S.; Niemiec, R. Well-being and well-doing: Bringing mindfulness and character strengths to the early childhood classroom and home. In Positive Psychology Interventions in Practice; Procter, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshani, A.; Slone, M. Positive education for young children: Effects of a positive psychology intervention for preschool children on subjective well being and learning behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A. Young children’s character strengths and emotional well-being: Development of the character strengths inventory for early childhood (CSI-EC). J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 14, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.; Green, S.; Falecki, D. Positive early childhood education: Expanding the reach of positive psychology into early childhood. Eur. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland Ministry of Education. Alistear: Early Childhood Curriculum Framework for All Children from Birth to 6 Years. Available online: https://curriculumonline.ie/Early-Childhood/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- New Zealand Ministry of Education. Te Whāriki: Early Childhood Curriculum. Available online: https://tewhariki.tki.org.nz/en/early-childhood-curriculum/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Norwegian Ministry of Education. Framework Plan for Kindergartens. Available online: https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/rammeplan/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- OECD. Starting Strong 2017: Key OECD Indicators on Early Childhood Education and Care; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Norrish, J.; Williams, P.; O’Connor, M.; Robinson, J. An applied framework for positive education. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stifter, C.; Augustine, M.; Dollar, J. The role of positive emotions in child development: A developmental treatment of the broaden and build theory. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 15, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, J.; Warren, M.; Gottfried, A. Does infant happiness forecast adult life satisfaction? Examining subjective well-being in the first quarter century of life. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 1401–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.; Ernst, R.; Gillham, K.; Linkins, M. Positive Education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2009, 35, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L. Positive Education: An Australian perspective. In The Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools, 2nd ed.; Furlong, M.J., Gilman, R., Huebner, E.S., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Boylan, F.; Barblett, L.; Knaus, M. Early childhood teachers’ perspectives of growth mindset: Developing agency in children. Australas. J. Early Child. 2018, 43, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz, K.; Dweck, C. The Origins of Children’s Growth and Fixed Mindsets: New Research and a New Proposal. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kuusisto, E.; Tirri, K. How teachers’ and students’ mindsets in learning have been studied: Research findings on mindset and academic achievement. Psychology 2017, 8, 1363–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.; Carver, C. Dispositional optimism and physical well-being: The influence of generalized outcome expectancies on health. J. Personal. 1987, 55, 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralek, D.; Colker, L. Making Lemonade: Teaching Young Children to Think Optimistically; Redleaf Press: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, M.; Leech, K. A parent intervention with a growth mindset approach improves children’s early gesture and vocabulary development. Dev. Sci. 2019, 22, e12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, E.; Sorhagen, N.; Gripshover, S.; Dweck, C.; Goldin-Meadow, S.; Levine, S. Parent praise to toddlers predicts fourth grade academic achievement via children’s incremental mindsets. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, E.; Gripshover, S.; Romero, C.; Dweck, C.; Goldin-Meadow, S.; Levine, S. Parent praise to 1- to 3-year-olds predicts children’s motivational framework 5 years later. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 1526–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeldobel, C.; Kerns, K. A literature review of gratitude, parent-child relationships, and well-being in children. Dev. Rev. 2021, 61, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczkowski, E.; Baker, B. Parenting children with developmental delays: The role of positive beliefs? J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2008, 1, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ellingsen, R.; Baker, B.; Blacher, J.; Crnic, K. Resilient parenting of preschool children at developmental risk. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slattery, E.; McMahon, J.; Gallagher, S. Optimism and benefit finding in parents of children with developmental disabilities: The role of positive reappraisal and social support. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 65, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmons, L.; Ekas, N. Giving thanks: Findings from a gratitude intervention with mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 49, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorinen, K.; Pessi, A.; Uusitalo, L. Nourishing compassion in Finnish kindergarten head teachers: How character strength training influences teachers’ other-oriented behavior. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denworth, L. Debate Arises over Teaching “Growth Mindsets” to Motivate Students. Scie. Am. Online. 2019. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/debate-arises-over-teaching-growth-mindsets-to-motivate-students/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Wong, P. Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Can. Psychol. 2011, 52, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Trinidad, J. Growth mindset predicts achievement only among rich students: Examining the interplay between mindset and socioeconomic status. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, V.; Burgoyne, A.; Sun, J.; Butler, J.; Macnamara, B. To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormeli, R. Grit and Growth Mindset: Deficit Thinking? Available online: https://www.amle.org/grit-and-growth-mindset-deficit-thinking (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Yakushko, O. Scientific Pollyannaism of Authentic Happiness, Learned Optimism, Flow and the Empirically Correct Positivity Ratios. In Scientific Pollyannaism; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI Global: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.; Løkken, I. Positive Psychology, Optimism, and Growth Mindset in Young Children in ECEC Settings: A Scoping Review Protocol. 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/C8PV2 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Clarivate Analytics. EndNote 20.1 (Bld 17060). Available online: https://endnote.com (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- JBI Global. JBIsumari. Available online: https://sumari.jbi.global (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Booth, A.; Sutton, A.; Papaioannou, D. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cefai, C.; Arlove, A.; Duca, M.; Galea, N.; Muscat, M.; Cavioni, V. RESCUR surfing the waves: An evaluation of a resilience programme in the early years. Pastor. Care Educ. 2018, 36, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, G.; Clark, S.; Calce, J. Using children’s literature for dynamic learning frames and growth mindsets. Read. Teach. 2017, 70, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlina, S.; Stanford, C. Preschoolers grow their brains: Shifting mindsets for greater resiliency and better problem solving. Young Child. 2011, 66, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnoni, M.; Karlen, Y.; Maag, K. Play it safe or play to learn: Mindsets and behavioral self-regulation in kindergarten. Metacognit. Learn. 2019, 14, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oorloff, S.; Rooney, R.; Baughman, N.; Kane, R.; McDevitt, M.; Bryant, A. The Impact of the Aussie optimism program on the emotional coping of 5- to 6-year-old children. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 570518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagor, R. Cultivating optimism in the classroom. Educ. Lead. 2008, 65, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Haslip, M.; Allen-Handy, A.; Donaldson, L. How do children and teachers demonstrate love, kindness and forgiveness? Findings from an early childhood strength-spotting intervention. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohtadi, R.; Aldarab’h, I.; Gasaymeh, A. Effectiveness of training sessions on a measure of optimism and pessimism concepts among the kindergarten children in the district of Al-Shobak in Jordan. World J. Educ. 2015, 5, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzina, R.; Paniello, S. Positive psychology, emotional education and the happy classrooms program. Pap. Psicol. 2017, 38, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, K.; Missall, K.; Shaffer, E.; Hojnoski, R. Promoting positive adaptation during the early childhood years. In Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools; Gilman, R., Huebner, E., Furlong, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Diesendruck, G.; Lindenbaum, T. Self-protective optimism: Children’s biased beliefs about the stability of traits. Soc. Dev. 2009, 18, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, B. Locus of control in early childhood education: Where did we come from? Where are we now? Where might we go from here? Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the Mid-South Educational Research Association, Biloxi, MS, USA, 8–10 November 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hopps-Wallis, K.; Fenton, A.; Dockett, S. Focusing on strengths as children start school: What does it mean in practice? Australas. J. Early Child. 2016, 41, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, R.; Waters, L. What does positive psychology tell us about early intervention and prevention with children and adolescents? A review of positive psychological interventions with young people. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 15, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.; Vaughn, B.; Akers, V.; Kim, M.; Stevens, S.; Krzysik, L.; Coppola, G.; Bost, K.; McBride, B.; Korth, B. Are happy children socially successful? Testing a central premise of positive psychology in a sample of preschool children. J. Posit. Psychol. 2011, 6, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L.; Dussert, D.; Loton, D. How do young children understand and action their own well-being? Positive psychology, student voice, and well-being literacy in early childhood. Int. J. Appl. Posi. Psychol. 2021, 9, 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L.; Loton, D. SEARCH: A meta-framework and review of the field of positive education. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 4, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, P.; Moloney, M.; Hoyne, C.; Beatty, C. Missing early education and care during the pandemic: The socio-emotional impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young children. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.; King, R.; Yeung, S.; Zhoc, C. Mind-sets in early childhood: The relations among growth mindset, engagement and well-being among first grade students. Early Educ. Dev. 2022, 1–16, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wustmann, S.; Sticca, F.; Gasser-Haas, O.; Simoni, H. Long-term promotive and protective effects of early childcare quality on the social-emotional development in children. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 854756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Included Items Focusing on This Element of Positive Psychology Programs in ECEC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| More than 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| character strengths | goal orientation | coping | attention |

| growth mindset | prosocial behaviour | gratitude | communication skills |

| optimism | mastery | compassion | |

| positive affect | creativity | ||

| critical thinking | |||

| emotional capital | |||

| emotional intelligence | |||

| empathy | |||

| explanatory style | |||

| forgiveness | |||

| grit | |||

| happiness | |||

| hope | |||

| intrinsic motivation | |||

| kindness | |||

| love | |||

| mindfulness | |||

| positive adaptation | |||

| positive emotions | |||

| positive interactions | |||

| positive thinking | |||

| positivity | |||

| resilience | |||

| self-efficacy | |||

| self-regulation | |||

| social skills | |||

| Number of Included Items Focusing on This Element of Child Well-Being as an Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| More than 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| adaptability | academic achievement | healthy life | absence of helplessness |

| happiness | flourishing | positive emotions | adjustment |

| learning | mental health | positive view of self | agency |

| prosocial behaviour | positive interactions | attachment | |

| resilience | emotional regulation | autonomy | |

| school readiness | awareness | ||

| social competency | belief in change | ||

| taking on challenges | character strengths | ||

| communication skills | |||

| coping | |||

| creativity | |||

| curiosity | |||

| efficacy | |||

| emotional competency | |||

| emotional maturity | |||

| empathy | |||

| flow | |||

| gratitude | |||

| intentional behaviour | |||

| kindness | |||

| less bullying | |||

| mastery | |||

| motivation | |||

| peer acceptance | |||

| perseverance | |||

| positive feelings | |||

| positive life trajectory | |||

| positive relationships | |||

| positive transitions | |||

| problem solving | |||

| psychological health | |||

| self confidence | |||

| self esteem | |||

| self-regulation | |||

| social imagination | |||

| social intelligence | |||

| strength | |||

| thriving | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campbell, J.A.; Løkken, I.M. Inside Out: A Scoping Review on Optimism, Growth Mindsets, and Positive Psychology for Child Well-Being in ECEC. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010029

Campbell JA, Løkken IM. Inside Out: A Scoping Review on Optimism, Growth Mindsets, and Positive Psychology for Child Well-Being in ECEC. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampbell, Janine Anne, and Ingrid Midteide Løkken. 2023. "Inside Out: A Scoping Review on Optimism, Growth Mindsets, and Positive Psychology for Child Well-Being in ECEC" Education Sciences 13, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010029

APA StyleCampbell, J. A., & Løkken, I. M. (2023). Inside Out: A Scoping Review on Optimism, Growth Mindsets, and Positive Psychology for Child Well-Being in ECEC. Education Sciences, 13(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010029