Abstract

The aim of this study is to demonstrate the attitudes and perceptions of teachers regarding the educational inclusion of students with hearing disabilities. The study sample consisted of 128 teachers from the Canary Islands, of which 72 worked in ordinary centers and 56 in Ordinary Centers for Preferential Educational Attention for Hearing Disability (COAEPHD). A quantitative cut methodology was used, based on the use of the Questionnaire of Opinions, Attitudes and Competencies of Teachers towards Disability (CACPD). The results of this study do not allow us to affirm that the teachers showed positive attitudes towards inclusion, expressing concern about offering a correct and adequate response to the students with hearing disabilities. They considered that educational inclusion requires important improvements focused on the training and specialization of teachers in the field of inclusion.

1. Introduction

The inclusive education model has become a benchmark for those educational communities that seek to implement their fundamental principles of equal opportunities and non-discrimination, with the aim of responding to students regardless of their individual characteristics and needs. The success or failure of the implementation of this model is conditioned by various factors, such as the organization and infrastructures of the center, the curricular and methodological management, and the availability of personal and material resources. The attitude of the teacher and the perception, beliefs and humanity attributed to the students with disabilities, acquire great value for the implementation of inclusive education since it can facilitate or hinder the processes of integration, learning, and participation of students. The perception and attitudes of teachers are conditioned by factors such as training, experience, years of teaching practice, etc., and they play a fundamental role in the success or failure of inclusive processes [1,2,3,4].

1.1. Diversity as a Value

The concept of diversity has been commonly associated with that of educational needs, being used to refer to students who have deficits or difficulties and who require specific actions to be able to progress in their learning [5]. This concept has varied and in this research is meant to be a characteristic of human nature that requires quality educational responses, differing and appropriate to individual characteristics and needs, regardless of the presence or absence of a disability.

Attention to diversity in terms of the adequacy of the educational response to diverse students promotes an organizational culture that turns educational centers into inclusive centers. In [6], the author defines inclusion as the action of “making the right to education effective for everyone, considering equal opportunities, eliminating barriers to learning and participation in the physical and social context” (p. 147). Inclusive educational centers must offer responses that assure students the right of equitable access to education, taking into account their individual characteristics and difficulties, paying special attention to those groups or collectives which have previously been excluded from the educational system [2,7,8].

Education for all must be promoted [9], and that in this sense we must reject the attitudes of exclusion, discrimination, or rejection that still exist today in most schools. In this sense, the prioritization of positive relationships and effective coexistence among all students stands out. Inclusive schools must become educational communities that practice respect and coexistence in the culture of diversity [10].

Furthermore, [11] states that inclusive schools must welcome all students regardless of their educational needs, they must ensure that all the individuals who make up the educational community feel recognized, esteemed, and active participants in it. They must also guarantee different educational strategies, forms of organization and various modes of teaching and evaluating, thus allowing all students to access learning and achieve their highest level and performance possible.

Specifically, and given the nature of this study, in relation to hearing impairment, we must consider that a student has special educational needs (SEN) due to hearing impairment (total deafness or hearing loss in its different degrees), regardless of the type of loss. The functionality of their hearing carries important implications in their learning, especially in the development of their communication and language skills [12].

1.2. Educational Response of Schools to Students with Hearing Disabilities

As stated in order 7036 ORDER of 13 December 2010, which regulates the care of students with SESN (Specific Educational Support Needs) in the Canary Islands, students with hearing disabilities will be enrolled whenever possible in an ordinary center. If this is not possible, the student will be enrolled in an Ordinary Center for Preferential Educational Attention (OCPEA). To determine their schooling, the early care they have received, their socialization, their possibilities of access to oral language, and whether they need a complementary system of communication or Spanish sign language, will be considered. If the educational response of the students requires human resources and specific materials which are difficult to generalize, they will be schooled in Ordinary Preferential Educational Attention Center (OPEAC), where the teaching staff specializing in Hearing and Language, the specialist teaching staff to support the SESN and the interpreter in Spanish Sign Language (ILSE) will be present in order to adapt and mediate their educational response.

Authors [13,14] point out that one of the main demands of students with hearing disabilities is to feel included and accepted in their school context. For this reason, apart from the educational adaptations and methodological orientations that are carried out, the centers must focus on improving the relationships which the students establish with their peers and other members of the school community. The promotion of expectations and attitudes towards diversity is directly related to positive interaction [15] and with knowledge of the needs of diverse students and the training of teachers who do not master communication systems or strategies such as Sign Language [16].

In this regard, [17,18] that the centers must offer an adequate educational response, adjusting the necessary measures and resources to respond to the students, without neglecting aspects such as interaction and relationship with others. Teachers recognize and consider that it is necessary to sensitize the educational community to the needs of these students, and for this, they require better training and qualifications [18].

1.3. Teachers’ Knowledge and Attitudes towards Diversity

As [4] considers that the way in which each teacher responds to the needs presented by their students, this becomes the variable with the greatest power to determine the success of inclusion in educational centers. Authors, such as [19] say that the success or failure of the measures which try to develop and maintain inclusion, will be affected by the knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of the educational community regarding disability, being determinants of the success or failure of the inclusive process [20,21,22,23,24].

There are important shortcomings in teacher training on disability [20,25,26], the lack of knowledge promotes negative attitudes and beliefs which stigmatize students with disabilities. As [4,15,27] affirm, in relation to attitudes, the success of an inclusive process, carried out properly, is related to the attitudes of the educational community where it develops. Ref. [19] argues that attitudes, understood as beliefs and feelings, are related to knowledge and involve an emotional charge, condition the individual, orienting their behavior based on their ideas, beliefs, opinions or perceptions, and emotions that they produce. As stated by [28,29,30], the attitudes of teachers determine the quality of educational attention that students receive. In this sense, [19] states that attitudes are modifiable and that adequate training is crucial for this. Continuous training, especially in the field of responding to diversity [4,15,31], favors not only the improvement of the educational response given to students but also the expectations towards the potential and real capacities of these students [31].

Despite the increase in training aimed at teachers [29], these are not related to the syllabus of the students for being teachers. The voluntary nature of the training offered after the completion of the studies becomes a real handicap, which does not guarantee either the quality of the training or the real achievement of skills to improve intervention with these students [30].

An analysis of the situation of teachers in the Canary Islands reveals this important lack, although Law 6/2014, of 25 July [32], states in article 64, that the initial training of teachers must train this group so that they can face the challenges of the educational system, making them acquire knowledge, skills, and abilities to carry out their work, including mastery of content and psycho-pedagogical aspects. A simple analysis of the training plans for kindergarten and primary teacher degrees at Canarian universities reveals the scant training and specialization in the field of SESN with which students finish their studies.

Teacher training has become a fundamental pillar of the quality of the educational response of students and the generation of attitudes and positive predisposition towards inclusion. Ref. [4] points out that the teachers of the Early Childhood Education and Primary Education stages have a more specific preparation than the teachers of higher stages. This fact, manifested in a better or worse knowledge of the educational needs and intervention strategies with students with disabilities, shows that the teachers of higher stages have less training and worse attitudes towards the inclusion of students with SESN. Authors such as [19,31] indicate that negative attitudes are related to a lack of training and knowledge of students and their SESN, and that training in the field of disability improves them. Refs. [33,34] attribute negative attitudes to ignorance about how to proceed, work, and intervene with these students.

1.4. Infrahumanization towards Diversity

The term humanity refers to the attributes that define what it is to be human [35]. The fact of perceiving that a person has less humanity than another or oneself supposes a categorization error, but it is a very common fact in our history and has shown the most radical and explicit forms of intergroup humiliation. Furthermore, infrahumanization justifies perverse and devastating actions towards different individuals or groups of the society. Such is it that, throughout history, we have been able to contemplate atrocities such as slavery, genocide, or terrorism, protected by the perception of being deshumanized from others.

Infrahumanization has a wide variety of behavioral consequences and seems to imply not only a lack of recognition of the outgroup’s humanity but also an active resistance to accepting members of other groups as completely human. Studies on infrahumanization base their principal hypothesis on the attribution of secondary emotions, and affirm that there is a stronger association between “secondary emotions” towards their own group, compared to the outgroup, to which they restrict the possibility of experiencing these human emotions. This differentiation is based on the fact that secondary emotions are a type of emotion that collects exclusive emotional states of human beings, for example, happiness, pride, or spite, while “primary emotions” are stated basic emotional feelings, such as joy, fear or pain, present in both human beings and animals. Furthermore, infrahumanization is independent of the valence (positive vs. negative emotions) and affirms that the ingroup inferred more secondary emotions (either positive or negative) to themselves in contrast to the out-group.

Infrahumanization has been shown towards groups with disabilities, specifically down syndrome [36], but we are not aware of any research that has analyzed the hearing disabilities group.

2. Materials and Methods

As [2] indicates, the attitude of the teacher acquires great importance in the inclusion processes, being able to facilitate or hinder learning, participation, and the same inclusive process in the center. For this reason, this work aims to analyze the perceptions and attitudes that teachers have towards the inclusion of students with disabilities, focusing especially on hearing impairment, to identify the variables that affect teachers’ attitudes and perception.

2.1. General Objectives

Analyze the attitudes and perceptions of teachers towards the inclusion of students with hearing disabilities.

Specific Objectives

Assess the attitudes and perceptions of teachers towards students with SEN, derived from hearing impairment.

To demonstrate the humanity that teaching staff attribute to the students with hearing disabilities.

Demonstrating the assessment of the training received by teachers in the field of hearing impairment.

2.2. Sample

To select the sample for this study, an intentional random sampling procedure (selection of educational centers) was carried out. The sample was made up of a total of 128 teachers from the Canary Islands, aged between 28 and 56 years. Of them, 72.7% (n = 93) were women and 27.3% (n = 35) were men. All educational centers were ordinary public centers (N = 72) and educational centers for children with hearing disabilities (N = 56)

Of these 128 professionals, 56.25% carry out their teaching activity in an ordinary center and 43.75%, in ordinary centers of preferential educational attention for hearing disabilities. Further, 50.8% (n = 65) of the teaching staff teach in Early Childhood Education and 49.2% (n = 63) in Primary Education.

Regarding their training, of the 128 professionals, 72.7% (n = 93) completed the diploma, 10.2% (n = 13) the degree, 7% (n = 9) a Master, and 10.2% (n = 13) have taken other training courses. Of the sample, only 6.3% (n = 8) received training in SESN, and 93.8% (n = 120) had not received training in SESN during their training at university (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample data.

2.3. Instruments

The instrument used to collect information from the sample was the abbreviated version of the Questionnaire of Opinions, Attitudes, and Competencies of Teachers towards Disability (CACPD) by [15]. It is a Likert-type rating scale with 5 response levels, where the value 1 expresses the worst opinions and attitudes towards the SESN and the value 5 best opinions and attitudes towards the SESN. This abbreviated version consists of 36 items, its reliability index is 0.904.

Regarding the analysis factors of the Questionnaire of Opinions, Attitudes, and Competencies of Teachers towards Disability (CACPD) by [15], the 36 items were grouped as follows: Factor 1: ‘General knowledge and attitude towards disability’ (items 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13), Factor 2: ‘Curricular inclusion of the SESN’ (items 16, 18, 19, 22, 24, 25), Factor 3: ‘Organization of the center to attend SESN’ (items 5, 6, 7, 23, 27, 28), Factor 4: ‘Favorable attitude towards awareness-raising work towards SESN’ (items 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35), Factor 5: ‘General competences needed in the SESN’ (items 1, 14, 15, 17, 20, 21), Factor 6: ‘Specific skills needed in the SESN’ (items 2, 3, 4, 26, 33, 36).

In addition, the Infrahumanization Scale was included, specifically the emotional terms used on [37]. This scale analyzes the level of primary and secondary emotions attributed to the students with hearing disabilities by the teachers. It is a 6-level Likert scale of response in which value 1 expresses a lower perception of the emotion to the students with disabilities and value 6, the high perception of that emotion. This scale allows us to know the level of primary emotions (basic emotions that animals also have) or secondary emotions (emotions that are reserved for humans) which teachers attribute to students with hearing disabilities.

2.4. Procedure

After the selection of the instruments, the ordinary centers and the COAEPHD who voluntarily wanted to participate were randomly selected. The difficulties arising from the COVID 19 pandemic forced us to adapt the questionnaire to an online version using Google Forms, which was sent to the management teams who oversaw sending the link to the teaching staff.

3. Results

3.1. Results on Training and Experience

It is shown that 63.3% of teachers have received training in SESN, compared to 36.7% of teachers who have not received training. Regarding the quality of the training received, 57% of teachers consider that SESN training is insufficient compared to 43% of teachers who consider it adequate.

Regarding training in hearing impairment, only 6.3% of teachers state that they have had specific training, compared to 93.8% of teachers who have not received specific training. Further, 48.4% of the teachers surveyed have had experience with students with hearing disabilities, compared to 51.6% who have not had experience with this disability. Regarding the perception of their qualifications to respond to students with hearing disabilities, 25% of the teachers felt prepared to give an adequate response, compared to 75% who did not feel prepared.

Finally, 66.4% of teachers have had experience with other types of SESN, compared to 33.6% of teachers who have not had experience with other disabilities (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Results based on training.

Regarding the experience, in Table 3, the degree of experience of the teachers with the different disabilities can be observed.

Table 3.

Results based on experience with other capabilities.

3.2. Infrahumanization Analysis

The humanity attributed to the students with disabilities was measured by the attribution of secondary emotions to them. This result was analyzed by gender, humanity attributed, and valence.

As is shown in the results, generally, men attribute more humanity towards the hearing-impaired group, and teachers with no experience with groups with disabilities and teachers from COAEPHD attribute more humanity towards the hearing impairment group.

3.2.1. Differences Based on Gender

There are significant differences based on gender regarding humanity, men attribute more secondary emotions (humanity) to the students with disabilities in comparison with women (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Infrahumanization based on gender

3.2.2. Infrahumanization Based on Experience with Other Disabilities

Teachers without experience with other students with disabilities, other than hearing impairment, attribute more secondary emotions (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Infrahumanization based on experience with other disabilities.

3.2.3. Infrahumanization Based on the Type of School

Teachers from ordinary schools attribute fewer secondary emotions towards students with disabilities than teachers from COAEPHD (See Table 6).

Table 6.

Infrahumanization depending on the type of center.

3.3. Results of Contrast of Dimensions (CACPD)

In this section, we present the mean values and standard deviations of each of the CACPD factors, ordered from highest to lowest. The values and detailed values of each of the items that make up each factor can be seen in Table 7. Low values indicate worse opinions and attitudes and high values better opinions and attitudes (Scale value from 1 to 5).

Table 7.

Factors of the Questionnaire of Opinions, Attitudes and Competences of Teachers towards Disability (CACPD).

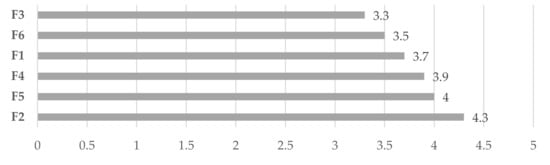

The results have shown that teachers show interest in the inclusion of the different SESN in the curriculum, (F2, = 4.30; Sd = 0.75), consider having general competencies necessary to respond to the SESN (F5, = 4.04; Sd = 0.66), shows a favorable attitude to work on awareness towards SESN (F4, = 3.93; Sd = 0.92), has knowledge and a good general attitude towards disability (F1, = 3.73; Sd = 0.81), has the specific skills necessary to respond to SESN (F6, = 3.50; Sd = 0.55) and considers that the organization of the centers to attend SESN is adequate (F3, = 3.32; Sd = 0.76).

Below is a summary table of the descriptive statistics of the responses provided (see Table 7).

The teaching staff values and highlights the curricular inclusion of the SESN ( 4.30), the favorable awareness-raising attitude carried out by teachers and other professionals of the center towards the SESN ( 3.93), and the general competencies necessary to respond to SESN, as well as their acquisition ( 4.04). However, it negatively values the organization of the center to attend SESN ( 3.32) as well as the specific competencies to respond to SESN.

In short, the teaching staff values factor 2, ‘Curricular inclusion in the SESN, more positively, while the value factor 3 more negatively, ‘Organization of the center to attend the SESN’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of the mean of the CACPD factors.

3.4. Differences in the Opinions, Attitudes, and Competencies of the Teaching Staff

For this analysis, the Student’s t-test for independent samples in two-level variables has been used, as well as the one-way ANOVA test for variables with more than two levels.

For the analysis, opinions, attitudes, and competencies, organized by factors, were compared with the variables gender, stage in which they teach, age, training in SESN in their initial instruction, and type of center.

3.4.1. Gender Differences

There are differences regarding the factors of ‘Knowledge and general attitude towards disability’ (Factor 1), ‘Curricular inclusion of SESN’ (Factor 2), ‘Attitude favorable to awareness work towards SESN’ (Factor 4), ‘General competences required in the SESN’ (Factor 5), and ‘Specific competencies necessary in the SESN’ (Factor 6). Men have a lower degree of knowledge, attitudes, and skills regarding disability, as well as less willingness to carry out awareness-raising attitudes towards SESN and their inclusion in the curriculum (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Gender differences.

3.4.2. Differences by Stage in Which They Teach

Differences were observed with respect to the factors of ‘Curricular inclusion of the SESN’ (Factor 2), ‘Organization of the center to attend the SESN’ (Factor 3), and ‘General competencies necessary in the SESN’ (Factor 5). The teachers who teach Early Childhood Education show a greater willingness to include content in the curriculum related to disability, as well as a greater degree of acquisition of general skills to respond to the SESN. The teachers who teach in the Primary Education stage produce a better assessment of the organization of the center (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Difference depending on the educational stage in which you teach.

3.4.3. Difference by Age

The results show differences depending on age with respect to the factors of ‘Organization of the center to attend the SESN’ (Factor 3), ‘General competencies necessary in the SESN’ (Factor 5), and ‘Specific competencies necessary in the SESN’ (Factor 6). The organization of the center to respond to the SESN is valued more positively by the older teachers. Younger teachers value more positively the acquisition of skills and knowledge, both general and specific (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Difference of opinions, attitudes, and competences extracted from the CACPD according to age.

3.4.4. Difference for Initial Training in SESN

Differences are observed with respect to the factors of ‘Curricular inclusion of SESN’ (Factor 2), ‘Attitude favorable to awareness work towards SESN’ (Factor 4), ‘General competencies necessary in SESN’ (Factor 5), and ‘Specific skills required in the SESN’ (Factor 6). The teachers who received training in SESN during the degree consider that they have acquired the general and specific skills necessary to respond to students with SESN. However, teachers who did not receive training in the SESN value more positively the inclusion of disability in the curriculum, as well as the attitudes towards disability that all teachers have (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Difference based on initial training in SESN.

3.4.5. Difference by Type of Center

Differences are observed depending on the type of center in the factors of ‘Curricular inclusion of the SESN’ (Factor 2), ‘Organization of the center to attend the SESN’ (Factor 3), and ‘General competencies necessary in the SESN’ (Factor 5). The teachers of ordinary schools value more positively the inclusion of content related to SESN in the curriculum, to work on knowledge and awareness of them, as well as the search for information and guidance to act correctly in the classroom with the students who present SESN. These teachers positively value their general knowledge, being willing to improve it by attending training courses, as well as the materials and aids they offer to these students. The teachers who carry out their work in the OCPEAHD value more positively the organization of the center to respond to the educational needs of the students who present SESN (see Table 12).

Table 12.

Differences depending on the type of center.

4. Discussion

In relation to knowledge and general attitude towards disability (F1), the teachers showed a generally positive perception regarding the interaction of students with those students with disabilities. Despite this, the teachers acknowledge that, in general, students are not aware of the limitations and capacities of their classmates with disabilities. It is essential for students to be aware of the disability, understand the limitations and capacities of their classmates, as well as the way to relate or interact with them [16]. Furthermore, as stated by [9,15,17,31], despite the fact that students have contact with classmates with disabilities, this interaction does not imply that they know the correct way to relate and that mere contact generates positive attitudes. Attitudes, as indicated by [19] determine the reality of the inclusion of students with disabilities and depend on the quality of interactions and relationships.

In relation to the curricular inclusion of the SESN (F2), the teachers gave importance to the inclusion of content related to disability in the curriculum, affirming that it enriches the knowledge of the students and favors positive attitudes towards disability. Ref. [16] highlighted the importance of being aware of essential aspects about disability and about strategies to improve the relationship and interaction with disabled students, thus improving the perception towards it and the inclusion process of the students [15,17,31].

In the case of hearing impairment, Ref. [36] defended the need to include Sign Language or alternative communication systems in the curriculum to improve the relationship and communication with deaf students. Ref. [13] promoted the performance of activities in small groups as a strategy to improve attitudes and skills towards students with disabilities.

Regarding the organization of the center to deal with SESN (F3), the teaching staff showed disparate opinions. This coincides with what was stated by [15], whose study reflected that the teaching staff believed it necessary to improve the awareness of the center through enrichment of the educational curriculum, including content related to diversity. Similarly, the teaching staff positively valued the actions that the centers carry out to eliminate possible barriers to inclusion. It is necessary to support and promote inclusive educational practices to avoid stigmatization of students and overcome barriers that allow the organization of accessibility and learning appropriate to the needs of students, a collaborative and cooperative learning climate, and an enrichment of the knowledge of the student teachers [38].

Regarding the attitude favorable to the work of awareness towards SESN (F4), the teachers agreed that the way each teacher responds to the diversity of their students influences the determination of the success of the inclusion of the students. A not very positive attitude of the teacher towards students with disabilities favors negative treatment, which could affect their educational, personal, and social development [4,19].

Those teachers who had experience with students with disabilities or who had at least contact with these students showed positive attitudes towards the inclusion and presence of students with disabilities in the classroom, as did those teachers who had training or specialization in disability [39]; Arias, et al., 2013; and [34].

Furthermore, teachers from COAEPHD perceived as more human the hearing impairment group, in comparison with the teachers from the ordinary group. As it has been commented on, in the theoretical bases of infrahumanization, this phenomenon has different consequences for people who are infrahumanized. There are several studies that affirm that infrahumanization interferes in helping behavior, that is, in the desire to help the infrahumanized person [40] and also reduces empathy with them [41,42]. The fact that there is infrahumanization in teachers is a very relevant fact and can promote negative attitudes towards the hearing impairment group. Moreover, it is very interesting the different infrahumanization between COAEPHD teachers and ordinary school teachers, and future studies would be of interest to analyze the performance or emotions of the hearing impairment group compared to the level of humanity that their teachers attribute to them.

In general, the teachers showed affection and empathy towards the students with disabilities. However, they pointed out that the presence, in class, of these students generated uncertainty and concern. This fact coincides with the lack of training (36.7%) and its low quality (57%). In this sense, it is essential to train teachers in the field of diversity to improve inclusive processes and promote positive attitudes [19,29,31].

In relation to the general competences necessary in the SESN (F5) and specific competences necessary in the SESN (F6), the aspects most valued by teachers are related to the importance of training and care for students with disabilities, finding themselves highly interested in receiving training to improve their knowledge. The educational reality of inclusion requires that teachers have adequate training for adequate support and intervention. An improvement in initial training, as well as in continuous training, would allow teachers to acquire knowledge and develop skills and abilities that would significantly improve the educational response to diversity [15,26,42,43,44].

Women showed better attitudes, knowledge, and skills compared to men, being more willing to carry out awareness-raising processes towards SESN and their inclusion in the curriculum. This coincides with that expressed by [15,18,34].

Early childhood education teachers showed a better attitude towards the inclusion of content related to disability in the curriculum, as well as the acquisition and development of general competencies to respond to the SESN. For their part, primary education teachers valued more positively the organization of the center to respond to the SESN. The highly positive attitudes presented by both groups coincided with that expressed by [19], who argued that the teachers of the infant and primary education stages had better attitudes towards inclusion. As stated by [4], teachers in the stages of early childhood education and primary education have specific preparation, and therefore greater knowledge, than teachers in higher stages.

Young teachers valued the acquisition of skills and knowledge more positively. As reflected by [4], younger teachers feel better prepared to serve students with disabilities due to the training received, which is why they value more positively the acquisition of knowledge and skills to give an adequate response to diversity. In this sense, the teachers who had received training in their studies valued the acquisition of the necessary general and specific competencies more positively, they considered that they had knowledge, strategies, and resources to respond to disability. As [26,42] indicate, teachers with previous training have more positive attitudes towards inclusion.

The OCPEAHD faculty positively valued the organization of the center to offer a response to diversity. As reflected in order 7036 ORDER of December 13, the OCPEAHD have human and material resources that offer a more specialized response to students, so the most positive assessment by the teachers who belong to these centers is common because they are better prepared and they have more resources to carry out specific attention to these students.

5. Conclusions

- The teaching staff showed generally positive opinions and attitudes towards inclusion, especially towards the curricular inclusion of the SESN and the acquisition of general competencies to respond to the SESN.

- The teaching staff considered that the organization of the center to attend the SESN and the acquisition of specific competencies to respond to the SESN could be improved.

- Women presented more favorable attitudes towards inclusion than men.

- Younger teachers valued more positively the acquisition of general and specific skills and knowledge in relation to SESN.

- Teachers who had received initial training felt better prepared to respond to the needs of students with SEN.

- The teaching staff of ordinary centers and OCPEAHD presented similar attitudes towards inclusion, although those who carried out their activity in ordinary centers valued more positively the awareness and the acquisition of knowledge to respond to the disability that their students present.

- Teachers who had not received training in SESN consider that they are not prepared or qualified to give an adequate educational response to students with SESN, which generates emotions of uncertainty and concern for not being able to offer or know how to give an adequate response to students with SESN.

- COAEPHD teachers attribute more humanity towards the hearing impairment group.

6. Limitations of the Study

- The alert situation and the cessation of face-to-face activity in the schools made access to the sample difficult and the participation of the teaching staff diminished. It was not possible to attend the educational centers physically and the questionnaire had to be adapted to an online version.

- As we only have the participation of 128 teachers, we must take the results with caution, therefore, it is recommended to expand the study by expanding the number of participants. Expanding the sample in subsequent studies will allow us to have a better representativeness of the sample.

- Although the results and conclusions provided in this study may not be representative of the reality of teachers in the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands, they may be of help to promote broader research or promote the development of more inclusive initiatives and of awareness towards SESN.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.-J. and E.A.-M.; methodology, D.P.-J. and M.d.C.R.-J.; formal analysis, D.P.-J. and E.A.-M.; investigation, D.P.-J., K.J.S.-G. and M.d.C.R.-J.; resources, D.P.-J. and E.A.-M. and K.J.S.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P.-J. and M.d.C.R.-J.; writing—review, all authors; visualization, all authors; supervision, E.A.-M.; project administration, D.P.-J., K.J.S.-G. and M.d.C.R.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of La Laguna. The APC was funded by project reference: 2021/0000126. Within the Aid plan for New Research Projects: Initiation to Research Activity. Call 2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of CEIBA (protocol code 2018-0331 approval date: 3 January 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

To the University of La Laguna.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Castro, P.G.; Álvarez, M.I.C.; Baz, B.O. Inclusión educativa. Actitudes y estrategias del profesorado. Rev. Española Discapac. 2016, 4, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granada, M.; Pomés, M.; Sanhueza, S. Actitud de los profesores hacia la inclusión educativa. Pap. Trab. 2013, 25, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ossa, C.; Castro, F.; Castañeda, M.; Castro, J. Cultura y liderazgo escolar: Factores claves para el desarrollo de la inclusión educativa. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2014, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Suriá, R. Discapacidad e integración educativa: ¿qué opina el profesorado sobre la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad en sus clases? Rev. Española Orientación Psicopedag. 2012, 23, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morodo, A. Convergencia Entre la Identidad Docente y la de Alumno como Medio de Atención a la Diversidad. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, C. Educación Inclusiva: Un modelo de diversidad humana. Rev. Educ. Desarro. Soc. 2011, 5, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Araque, N.; Barrio, J. Atención a la diversidad y desarrollo de procesos educativos inclusivos. Prism. Soc. 2010, 4, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, G. La formación de docentes para la inclusión educativa. Páginas Educ. 2013, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barragán-Medero, F.; Pérez-Jorge, D. Combating homophobia, lesbophobia, biphobia and transphobia: A liberating and subversive educational alternative for desires. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ruiz, J.; Pérez-Jorge, D.; García García, L.; Lorenzetti, G. Gestión de la Convivencia; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Echeita, G. Educación Inclusiva. Sonrisas y lágrimas. Aula Abierta 2017, 46, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, S.; Ruiz, F.; De la Hoz, V. Propuesta didáctica para fortalecimiento de los procesos cognitivos en estudiantes con discapacidad auditiva incluidos en la educación superior basado en su estilo de aprendizaje. In Libro de Memorias: VIII Congreso Mundial de Estilos de Aprendizaje; Tomo II; Cancino, M., García, M., Rolong, M., Villar, L., Zapata, M., Caro, K., Balceiro, N., Eds.; Universidad del Atlántico: Barranquilla, Colombia, 2018; pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Rey, J.; Pérez-Tejero, J. Experiencia práctica: Estrategias para la inclusión de personas con discapacidad auditiva en Educación Física. Rev. Española Educ. Física Deportes 2014, 406, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Castor, L.; Casas, J.; Sánchez, S.; Vallejos, V.; Zúñiga, D. Percepción de la calidad de vida en personas con discapacidad y su relación con la educación. Estud. Pedagógicos 2016, 42, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jorge, D. Actitudes y Concepto de la Diversidad Humana: Un Estudio Comparativo en Centros Educativos de la isla de Tenerife. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo, L. Intervención Educativa en un Caso de Discapacidad Auditiva. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Väyrynen, S.; Paksuniemi, M. Translating inclusive values into pedagogical actions. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; de la Rosa, O.M.A.; del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.; Márquez-Domínguez, Y.; de la Rosa Hormiga, M. La identificación del conocimiento y actitudes del profesorado hacia inclusión de los alumnos con necesidades educativas especiales. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, P.; Pedrosa, I.; Mateos-Fernández, L. Assessment and interpretation of teachers’ attitudes towards students with disabilities/Evaluación e interpretación de la actitud del profesorado hacia alumnos con discapacidad. Cult. Educ. 2019, 31, 576–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jorge, D. Reforma versus Innovación. Educadores 1999, 41, 443–455. [Google Scholar]

- Broomhead, K.E. Acceptance or rejection? The social experiences of children with special educational needs and disabilities within a mainstream primary school. Education 3–13 2019, 47, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L. On the necessary co-existence of special and inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Martínez, Y.; Monge-López, C.; Seijo, J.C.T. Teacher education in cooperative learning and its influence on inclusive education. Improv. Sch. 2020, 23, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.C.; Ariño-Mateo, E.; Barragán-Medero, F. The effect of Covid 19 on synchronous and asynchronous models of university tutoring. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, Y.A. The perspectives of Colorado general and special education teachers on the barriers to co-teaching in the inclusive elementary school classroom. Education 3–13 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, B.; Verdugo, M.; Gómez, L.; Arias, V. Actitudes hacia la discapacidad. In Discapacidad e Inclusión, Manual Para la Docencia; Verdugo, M., Schalock, Y.R., Eds.; Amarú Ediciones: Salamanca, Spain, 2013; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkos, G.; Hajisoteriou, C. Sustainable intercultural and inclusive education: Teachers’ efforts on promoting a combining paradigm. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Brown, Z.; Hodkinson, A. ‘What is considered good for everyone may not be good for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities’: Teacher’s perspectives on inclusion in England. Education 3–13 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Hinojosa, E. El estudio de las creencias sobre la diversidad cultural como referente para la mejora de la formación docente. Educ. XXI 2012, 15, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Figueredo, V.; Pérez, M.; Sánchez, A. Interculturalidad y discapacidad: Un desafío pendiente en la formación el profesorado. Rev. Nac. Int. Educ. Inclusiva 2017, 10, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; Pérez-Martín, A.; del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.; Barragán-Medero, F.; Hernández-Torres, A. Self and hetero-perception and discrimination in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, D.; Giné, C. La Formación del Profesorado Para la Educación Inclusiva: Un Proceso de Desarrollo Profesional y de Mejora de los Centros Para Atender a la Diversidad. 2011. Available online: http://www.repositoriocdpd.net:8080/bitstream/handle/123456789/1913/Art_DuranGisbertD_Formaciondelprofesorado.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Pegalajar, M.; Colmenero, M. Actitudes del docente de centros de educación especial hacia la inclusión educativa. Enseñanza Teach. 2014, 32, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegalajar, M.; Colmenero, M. Actitudes y formación docente hacia la inclusión en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2017, 19, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariño, E. La Infrahumnaización de Grupos Estigmatizados: El Caso del Síndrome de Down. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, N.; Loughnan, S. Dehumanization and Infrahumanization. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, A.; Betancor-Rodríguez, V.; Ariño-Mateo, E.; Demoulin, S.; Leyens, J.P. Normative data for 148 Spanish emotional words in terms of attributions of humanity. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Estévez, A. Alumnado con deficiencia auditiva: Orientaciones para la intervención educativa. Innovación Exp. Educ. 2010, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, A.; Jan, S.; Minnaert, A. Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 15, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A.; Rock, M.; Norton, M. Aid in the aftermath of hurricane katrina: Inferences of secondary emotions and intergroup helping. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2007, 10, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cehajic, S.; Brown, R.; González, R. What do I care? Perceived ingroup responsibility and dehumanization as predictors of empathy felt for the victim group. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2009, 12, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M. La escuela inclusiva: Una oportunidad para humanizarnos. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2012, 26, 131–161. [Google Scholar]

- Barría, S.; Jurado, P. El perfil profesional y las necesidades de formación del profesor que atiende a los alumnos con discapacidad intelectual en la formación laboral. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2016, 20, 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, L.; Villardón, L. Actitudes hacia la inclusión educativa de futuros maestros de inglés. Rev. Latinoam. Educ. Inclusiva 2015, 9, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).