Abstract

High-dimensional tabular data are common in biomedical and clinical research, yet conventional machine learning methods often struggle in such settings due to data scarcity, feature redundancy, and limited generalization. In this study, we systematically evaluate Synolitic Graph Neural Networks (SGNNs), a framework that transforms high-dimensional samples into sample-specific graphs by training ensembles of low-dimensional pairwise classifiers and analyzing the resulting graph structure with Graph Neural Networks. We benchmark convolution-based (GCN) and attention-based (GATv2) models across 15 UCI datasets under two training regimes: a foundation setting that concatenates all datasets and a dataset-specific setting with macro-averaged evaluation. We further assess cross-dataset transfer, robustness to limited training data, feature redundancy, and computational efficiency, and extend the analysis to a real-world ovarian cancer proteomics dataset. The results show that topology-aware node feature augmentation provides the dominant performance gains across all regimes. In the foundation setting, GATv2 achieves an ROC-AUC of up to 92.22 (GCN: 91.22), substantially outperforming XGBoost (86.05), . In the dataset-specific regime, GATv2, combined with minimum-connectivity filtering, achieves a macro ROC-AUC of 83.12, compared to 80.28 for XGBoost. Leave-one-dataset-out evaluation confirms cross-domain transfer, with an ROC-AUC of up to 81.99. SGNNs maintain ROC-AUC around 85% with as little as 10% of the training data and consistently outperform XGBoost in more extreme low-data regimes, . On ovarian cancer proteomics data, foundation training improves both predictive performance and stability. Efficiency analysis shows that graph filtering substantially reduces training time, inference latency, and memory usage without compromising accuracy. Overall, these findings suggest that SGNNs provide a robust and scalable approach for learning from high-dimensional, heterogeneous tabular data, particularly in biomedical settings with limited sample sizes.

1. Introduction

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has experienced unprecedented growth, particularly in the domain of Large Language Models (LLMs)—transformer-based architectures trained on massive text corpora [1]. These models exhibit remarkable capabilities and represent a significant step toward general, even superhuman, AI. A prominent study by Epoch AI [2] recently made headlines by quantifying a looming challenge: by around 2028, the average dataset size used to train AI models is expected to reach the total estimated stock of all publicly available online text. In other words, AI may run out of new training data within the next few years [3,4]. In contrast, the situation in biology and physiology is qualitatively different. Access to diverse clinical, physiological, and cognitive datasets has expanded dramatically. Today, we can sequence the human genome with near-complete resolution [5,6], map the proteome and transcriptome [7], especially with focus on single-cell omics [8], monitor DNA methylation across millions of genomic loci [9], and work with high-resolution physiological and imaging data, spanning both advanced signal processing of modalities such as EEG, ECG, CT, MRI, fMRI, and MEG and the generation of synthetic samples of some of these modalities [10]. Moreover, there is now widespread availability of structured and unstructured Electronic Health Records (EHRs) [11].

Despite substantial progress and increasing volume of data, translating complex, high-dimensional biomedical records into actionable clinical knowledge remains difficult. For many medical problems, the amount of clean data available for machine learning remains very small. These datasets are heterogeneous and often longitudinal, spanning genomics, proteomics, physiological signals, medical imaging, and electronic health records (EHRs), and each modality raises distinct challenges for interpretable machine learning [12]. Traditional approaches suffer from the curse of dimensionality [13]: as feature counts grow, the number of samples required to maintain generalizability increases exponentially, which is rarely feasible in healthcare, leading to overfitting and weak predictive performance [14,15]. Compounding this, many deep learning models lack the interpretability and transparency required for clinical adoption [12]. Although recent advances thrive on images and text, they frequently fail to generalize to structured biomedical representations, such as patient graphs, brain connectomes, or molecular interaction networks, without substantial domain-specific preprocessing [16].

There are three primary requirements for AI algorithms designed to analyze clinical data [17,18], described as follows:

- Robustness to heterogeneity. They must detect diverse and hidden patterns that may lead to the same clinical outcome, recognizing that compensatory mechanisms can produce similar disease manifestations via different pathways.

- Data efficiency. They must be able to learn from small sample sizes, given the scarcity and cost of clinical data.

- Interpretability. They must go beyond simple classification and offer insightful, explainable reasoning, and, even better, the test procedure to verify the conclusion, especially for tasks such as early diagnosis and risk stratification.

In this context, graph-based AI methods emerge as particularly promising [19]. The human body itself is naturally organized as a multi-layered, interconnected system—a “network of networks” [20]. Organs interact within physiological systems, which are regulated by the brain, itself a complex network of neurons and astrocytes. At the molecular level, cellular processes such as growth, development, aging, and disease progression (e.g., tumorigenesis) are governed by dynamic epigenetic and transcriptional regulatory networks, with growing recognition of the role of non-coding RNAs in shaping these interactions.

Thus, representing clinical and physiological data as graphs, mathematical structures that capture relationships between elements, aligns naturally with the biological architecture of the human body. By leveraging the topological and relational properties of such data, graph-based models offer a powerful framework for capturing complexity, enabling robust predictions, and uncovering mechanistic insights that are critical for advancing precision medicine [21].

One of the earliest approaches to transforming tabular biomedical data into graphs was proposed by Zanin and Boccaletti in the form of parenclitic networks [22]. Using linear regression, this method constructs sample-specific graphs by modeling expected pairwise feature relationships in control samples. Deviations from these relationships in case samples define edges in the graph. Topological metrics of these graphs can then be used as features in downstream classifiers, embedding high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional and interpretable space. This approach has been successfully applied to gene expression, metabolomics, and epigenetic datasets [23].

Despite their utility, parenclitic networks have limitations, including reliance on linear assumptions, thresholding sensitivity, and poor scalability to multimodal or large-scale data. To address these issues, later work introduced enhancements such as using two-dimensional kernel density estimation (2DKDE) instead of linear regression [24], and edge weighting schemes taking account of the boundary between classes in the plane of two features [25]. These improvements led to more accurate class separation and greater biological interpretability.

Building upon these developments, Synolitic Graph Neural Networks (SGNNs) [16] offer a more scalable and generalizable alternative. SGNNs construct graphs using an ensemble of low-dimensional classifiers trained on all pairwise feature combinations. These graphs are class-specific and do not require any domain-specific knowledge or anatomical priors. Unlike traditional Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) tailored to specific domains (e.g., BrainGNN for fMRI), SGNNs generalize across data types and support both continuous and categorical variables. SGNNs have shown promise in prior applications such as aging trajectory analysis [26], prognosis in COVID-19 patients [27,28], and epigenetic profiling in cancer and Down syndrome [26]. These studies demonstrate the potential of SGNN-derived graph representations to uncover biologically meaningful patterns.

However, existing work has primarily focused on generating graph embeddings. To date, it remains unclear how different downstream GNN architectures can effectively exploit these embeddings for classification. This work presents the first systematic evaluation of Synolitic Graph Neural Networks (SGNNs) for high-dimensional tabular classification. We transform high-dimensional, heterogeneous datasets into sample-specific graphs via ensembles of pairwise low-dimensional classifiers and enrich them with topology-aware node descriptors (degree, strength, closeness, and betweenness) and multiple sparsification strategies (top-p edges and minimum-connected). We benchmark two representative GNNs—GCN (convolution-based [29]) and GATv2 (attention-based [30])—in two regimes: (i) a foundation setting on a concatenation of 15 UCI datasets (selected via the Mirkes et al. taxonomy [31]) to probe cross-task generalization, and (ii) dataset-specific training to assess within-domain performance.

We show via five-fold cross-validation that across both regimes, inducing graph structure together with topology-aware node descriptors and edge-based sparsification improves predictive performance over a strong tabular baseline (XGBoost), is robust to feature redundancy, and exhibits promising out-of-domain generalization. In the foundation setting, these improvements are statistically significant relative to XGBoost (DeLong test [32] with Holm correction, ), and the same statistical criterion confirms a significant advantage under reduced training sizes in the curse-of-dimensionality study. Together, these results position SGNNs as a practical route for learning from high-dimensional, heterogeneous biomedical data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

We evaluate publicly available binary classification tabular datasets from the UCI Machine Learning Repository. We selected these datasets based on criteria proposed by Mirkes et al. [31], ensuring consistency and relevance to biomedical-like settings. Selection criteria include the following:

- Binary class labels;

- No missing values;

- All features are numerical or binary;

- The number of samples exceeds the number of features.

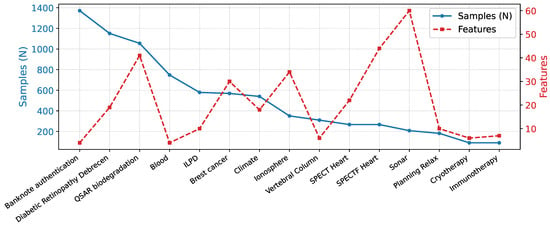

These datasets provide a varied testbed for assessing model generalizability across domains with varying feature dimensions, sample sizes, and class distributions. In this report, we selected 15 datasets (Figure 1) for which constructing sample-specific graphs is computationally feasible within acceptable time constraints, providing a balanced trade-off between dataset diversity and experimental practicality.

Figure 1.

Statistics of the 15 UCI tabular datasets used in this study, illustrating the diversity in feature dimensionality that underpins the evaluation of Synolitic Graph Neural Networks.

To evaluate classification performance, we report the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC-AUC). All experiments employ stratified 5-fold cross-validation for each dataset. In the foundation setting, we assess statistical significance by concatenating out-of-fold predictions across all folds and datasets and applying the DeLong test with Holm correction at .

2.2. Models

2.2.1. Pipeline Architecture

SGNNs constitute a general-purpose framework for converting high-dimensional data into graph representations [16]. The method constructs sample-specific graphs by training an ensemble of pairwise classifiers using class labels. All nodes of our graph are features of the dataset. For each unique feature pair, a binary classifier is trained to learn the class-separating decision boundary in the corresponding two-dimensional projection. In this study, we use a Support Vector Machine (SVM) [33] as the pairwise classifier, with hyperparameters specified in Table 1. The output scores of each classifier are then used to define edge weights between the corresponding feature nodes, where nodes represent features and edges encode the strength of class separation.

Table 1.

Configuration parameters for the Graph Neural Networks.

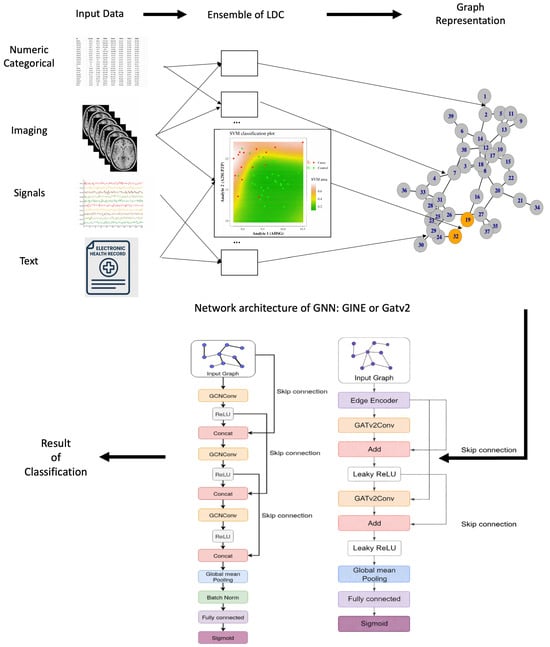

This transformation yields one graph per sample, which is subsequently processed by a GNN that operates on graph structure and edge weights to produce a classification for each input sample. An overview of this process is presented in Figure 2, which illustrates how SGNNs can accommodate diverse data modalities, including numerical features, categorical variables, imaging, and electronic health records.

Figure 2.

Overview of the SGNN methodology, progressing from the top left following the arrows. Input data from different modalities (numerical, categorical, imaging, high-frequency signals, and EHR) is processed by an ensemble of low-dimensional classifiers (LDCs), each trained on a pair of features and their corresponding class labels. Class boundaries (e.g., red/green lines) are learned via standard ML kernels such as SVMs. The outputs of these classifiers define edge weights in the Synolitic graph. Synolitic graph is classified by GNN of two possible architectures, leading to the result.

In this report, we evaluate the effectiveness of the following two state-of-the-art GNN architectures as downstream classifiers operating on SGNN-derived graphs:

- GCN (Graph Convolutional Network) [29]—chosen for its theoretical expressiveness and support for edge-level information.

- GATv2 (Graph Attention Network v2) [30]—selected for its ability to learn dynamic attention weights over neighbors without predefined attention bias.

The parameters used in experiments, reported in Table 1, correspond to the default hyperparameters recommended in the original papers [29,30,34] and official implementations of the respective methods [35,36,37], ensuring a fair and consistent comparison. To evaluate the proposed SGNN methodology, we designed a structured experimental pipeline. This pipeline includes distinct stages encompassing graph construction, model training, and performance benchmarking. Each stage was tailored to systematically assess the effectiveness and generalizability of the approach across diverse biomedical datasets. The experimental procedure consists of the following stages:

- 1.

- SGNN Graph Construction. We generate sample-specific graphs from selected tabular datasets using the SGNN methodology, which relies on ensembles of pairwise classifiers trained with class labels for each dataset and produces a unique graph structure for every data point [16].

- 2.

- GNN Training. We train two Graph Neural Networks—GCN and GATv2—on the resulting graphs to perform classification. For each model and task, we use training parameters selected individually via hyperparameter optimization with the Optuna framework [38].

- 3.

- Training Strategies. We evaluate two training regimes: (i) training on the concatenation of all datasets as a form of task-agnostic pretraining or foundation model setting, and (ii) individual training on each dataset separately. Exploration of these settings allows us to examine generalization across datasets.

- 4.

- Comparison with Classical Models. We compare our graph-based approaches with a classical XGBoost classifier [34] trained on the same datasets to assess the relevance and added value of GNNs in this classification context.

2.2.2. Node Features

To enrich the initial graph representation, namely the full graph, we augment nodes with structural features that capture their topological properties within the network. Starting from the original scalar node feature , we construct a five-dimensional feature vector:

where the following apply:

- is the original scalar feature of node i;

- is the normalized node degree, i.e., the normalized number of edges connected to this node: , where N is the number of nodes;

- is the normalized node strength: , where and is an edge weight between nodes i and j;

- is the closeness centrality of node i, calculated as the reciprocal of the sum of the length of the shortest paths between the node and all other nodes in the graph;

- is the betweenness centrality of node i computed with edge weights.

This combination of features enables the model to consider both local node characteristics (degree, strength) and global structural importance (centrality measures) within the graph topology.

2.2.3. Graph Sparsification

To investigate the impact of edge density on prediction quality, we implement the following three graph sparsification strategies:

- 1.

- Threshold-based sparsification: Retains a fraction p of the most significant edges based on the criterion , where is the edge weight. This approach allows control over graph sparsity while preserving connections with the greatest deviation from the neutral value 0.5.

- 2.

- Minimum connected sparsification: Employs binary search to determine the maximum threshold such that the graph remains connected. The method finds the minimal edge set that ensures graph connectivity, thereby optimizing the trade-off between sparsity and structural integrity.

- 3.

- No sparsification: Baseline configuration that preserves the original graph structure.

These sparsification methods enable investigation of the compromise between computational efficiency and preservation of important structural information in molecular graphs.

3. Results

3.1. Foundation Model Task

To assess the generalizability of the SGNN pipeline, we consider the foundation setting, where we merge all selected UCI datasets into a single unified classification task. As shown in Table 2, enabling topology-aware node features leads to a substantial and statistically significant improvement in ROC-AUC for both GCN and GATv2, consistently outperforming the XGBoost baseline (86.05). GATv2 achieves the best overall performance without sparsification when node features are available (ROC-AUC = 92.22), with strong sparsification (, ROC-AUC = 92.20) yielding a comparable result. GCN exhibits stable performance across sparsification strategies once node features are enabled, showing no pronounced sensitivity to graph filtering. In the absence of node features, performance decreases relative to feature-augmented configurations; however, GATv2 still consistently outperforms the XGBoost baseline, with sparsification providing at most marginal additional gains, including a slight improvement under light filtering (). Overall, these results indicate that node features are the primary driver of performance gains in the foundation setting, while attention-based models benefit from retaining dense or moderately dense connectivity.

Table 2.

ROC-AUC results in the foundation model setting for different models and sparsification strategies, with and without node features. Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation across folds. The best ROC–AUC value is highlighted in bold. Asterisks (*) denote statistically significant improvements over the XGBoost baseline according to the DeLong test with Holm correction at . “Node Features = True/False” indicates whether topology-aware node descriptors are used in addition to edge weights.

3.2. Separate Datasets Task

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed SGNN pipeline, we applied it to each dataset individually, with performance summarized as the macro-averaged ROC-AUC across all evaluated datasets. As shown in Table 3, GATv2 consistently exceeds the XGBoost baseline (80.28) when node features are enabled, achieving its best result under minimum-connectivity filtering (83.12), with stronger sparsification () close behind (82.46); the unfiltered configuration with features also performs competitively (81.53). GCN achieves lower scores overall, peaking at 77.70 with node features and moderate filtering (). The same as in Section 3.1, across both architectures, node features provide a consistent performance gain, while sparsification acts as a structural filter that can modestly improve generalization for attention-based models but offers limited benefit in the absence of node-level descriptors. Overall, these results indicate that attention-based GNNs benefit from appropriate graph filtering in the separate-datasets setting, particularly when informative node features are available.

Table 3.

Macro ROC-AUC, i.e., averaged over all datasets, results for the separate-datasets setting across different models and sparsification strategies, with and without node features. The best ROC–AUC value is highlighted in bold.

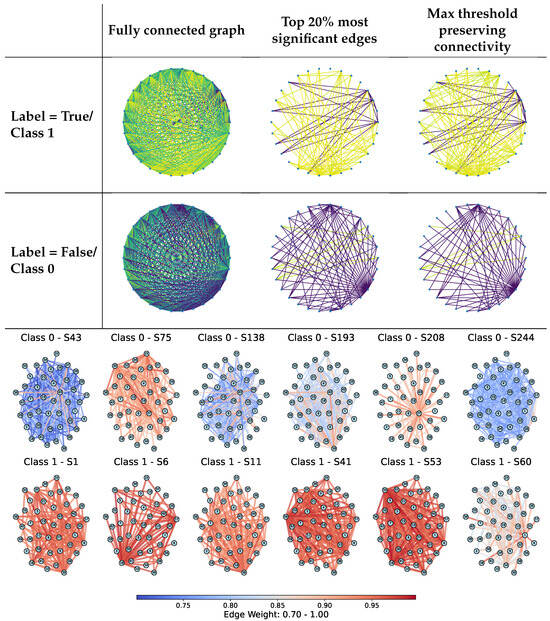

3.3. Visualization of Sparsification Strategies

Figure 3 (top) visually compares different sparsification strategies applied to sample-specific graphs: fully connected graphs, top 20% most significant edges, and minimum threshold graphs that preserve connectivity. The examples illustrate how structural filtering affects graph topology for both positive and negative class samples, with stronger sparsification yielding sparser yet still interpretable structures. In addition, differences between samples are reflected not only in graph connectivity but also in the distribution of edge weights, as indicated by the edge color patterns, highlighting class-dependent variations in relational strength.

Figure 3.

(Top): Examples of threshold-based edge sparsification applied to sample-specific graphs, including fully connected graphs, graphs retaining the top 20% strongest edges, and minimum-connected graphs. Rows correspond to UCI samples with positive (Class 1) and negative (Class 0) labels. Edge colors represent normalized edge weights in the range [0, 1], from purple (low) to yellow (high). (Bottom): Connectivity-preserving sparsified synolitic graphs for representative samples from the SPECTF dataset (Classes 0 and 1). Edges are colored by normalized weights (0.70–1.00). Class 1 samples exhibit denser connectivity and a higher proportion of large-weight edges, whereas Class 0 samples show more heterogeneous structures with high-weight connections concentrated around fewer hubs. These patterns illustrate class-dependent differences in graph structure captured by synoptic representations.

In addition, Figure 3 presents connectivity-preserving sparsified synolitic graphs for representative samples from the SPECTF dataset from the UCI repository (Classes 0 and 1). In these examples, edges are colored by their normalized weights (0.70–1.00), with higher values corresponding to stronger class-separability signals captured by the pairwise SVM classifiers. Visually, Class 1 graphs exhibit a higher proportion of large-weight edges and retain denser connectivity under the same minimum-connected filtering, suggesting more consistently strong pairwise interactions across a larger subset of features. In contrast, Class 0 graphs appear more heterogeneous and often concentrate high-weight connections around fewer visually prominent hubs, for example, node 22 in sample S75 and node 27 in sample S208. For Class 1, several nodes recur as prominent hubs across multiple samples (e.g., nodes 18, 33, and 36 in the shown examples), indicating a more consistent distribution of high-weight connectivity patterns within the class. These qualitative differences motivate the use of topology-aware descriptors and connectivity-preserving filtering to capture class-dependent structural signatures in synolitic graphs.

3.4. Testing the Universality of the Pipeline

To evaluate the generalization capability of the SGNN pipeline, we adopted a leave-one-out evaluation strategy across multiple datasets. In this experimental design, we trained the model on Synolitic graphs constructed from all datasets except one, which was held out for testing. This procedure was repeated for each dataset, ensuring that every dataset served as an independent test domain. We maintained the SGNN architecture constant across all runs, utilizing GATv2, which demonstrated the best overall performance in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2. To ensure consistency and isolate the effects of cross-dataset transfer, we employed its base configuration without additional hyperparameter tuning. This setup enabled us to evaluate how effectively the model can transfer knowledge learned from diverse high-dimensional datasets to previously unseen domains.

As shown in Table 4, the SGNN pipeline exhibits consistent generalization to unseen domains. Training on synolitic graphs alone yields a macro ROC-AUC of 63.89, while applying maximum-threshold sparsification that preserves graph connectivity improves performance to 67.52, indicating that structural filtering helps suppress dataset-specific noise. Incorporating additional node features leads to a substantial gain, achieving the best macro ROC-AUC of 81.99. These results highlight the central role of topology-aware node descriptors in capturing transferable structural patterns shared across heterogeneous datasets. At the same time, sparsification primarily acts as a graph filtering mechanism that facilitates cross-domain generalization.

Table 4.

Effect of SGNN sparsification and node feature augmentation on macro ROC-AUC. The best ROC–AUC value is highlighted in bold.

3.5. Dealing with the Curse of Dimensionality

High-dimensional tabular learning is particularly challenging in sample-limited regimes due to the curse of dimensionality, where reliable estimation becomes increasingly data-hungry, and models are more prone to overfitting as the feature space grows [39]. While classical remedies such as feature selection or dimensionality reduction can mitigate this effect, identifying a stable, task-relevant subspace that generalizes across datasets often itself requires substantial data. To assess whether SGNN-induced graph representations alleviate this limitation in practice, we progressively reduce the available training data and quantify how predictive performance degrades under increasingly constrained supervision.

To evaluate the performance of the SGNN pipeline in high-dimensional, low-sample settings, we conducted a series of benchmark experiments across all 15 datasets in the foundation setting, using the same parameters as in Section 3.1. To simulate increasingly data-scarce conditions, we further reduced the size of the training set in systematic increments, down to 1% of the original training size. We then compared the classification performance of SGNNs to that of a standard ensemble-based machine learning model, XGBoost, which is widely recognized for its robustness and performance in structured data tasks.

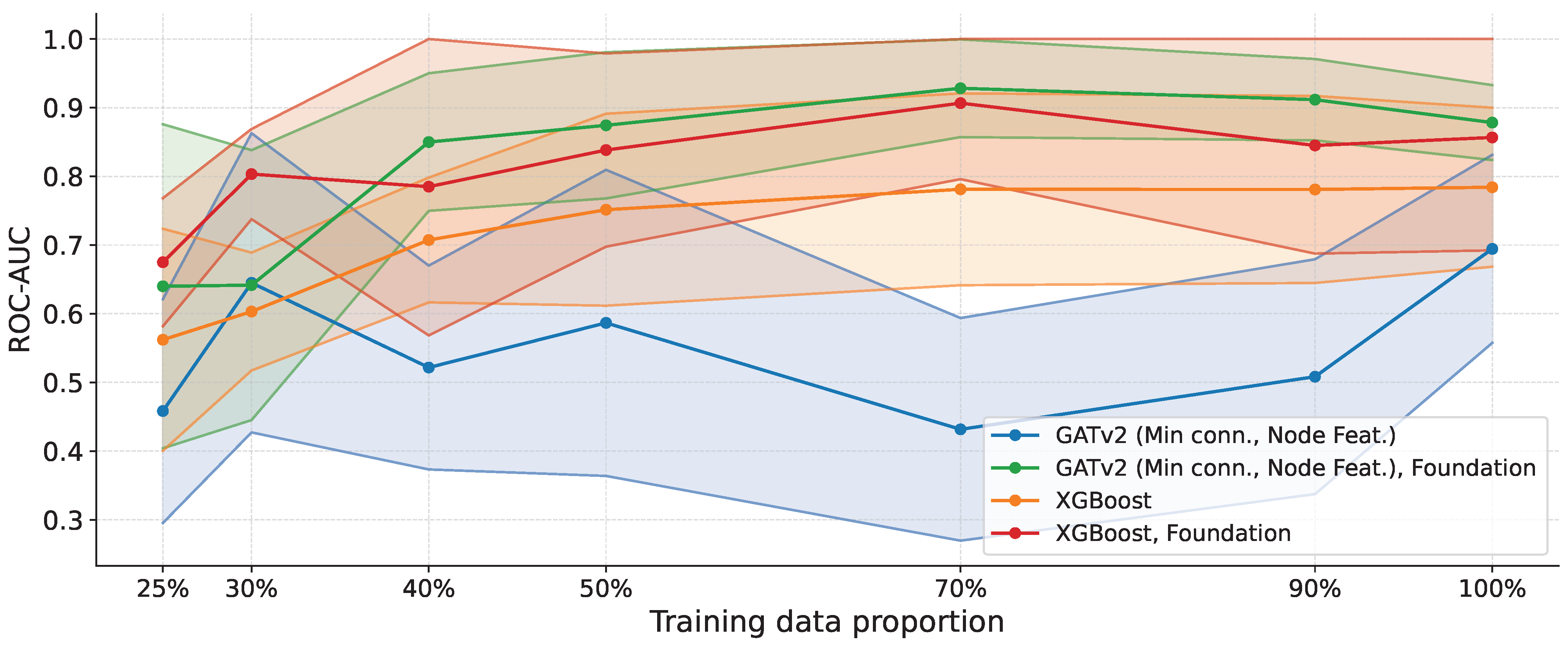

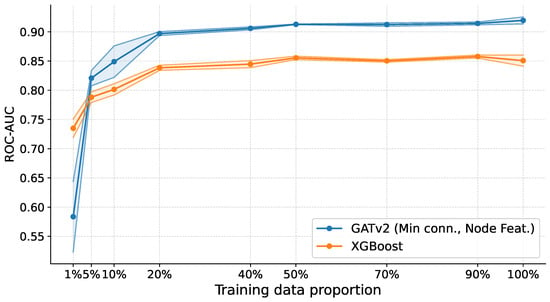

As shown in Figure 4, XGBoost exhibits a pronounced decline in performance as the amount of training data decreases, with ROC-AUC dropping below 85% once less than 40% of the training data is available. In contrast, the SGNN pipeline remains substantially more robust across low-data regimes, maintaining ROC-AUC at approximately 85% from 10% of the training data onward. Although performance degrades in the most extreme setting (1%), SGNNs still outperform the boosting baseline. Across all evaluated training proportions, this advantage is statistically significant (), confirming that the performance gap is not attributable to random variation.

Figure 4.

Performance comparison between SGNNs and a conventional machine learning baseline under varying training set sizes. ROC-AUC is reported as a function of the fraction of available training data, averaged across folds. For each dataset, the training set size is progressively reduced to assess robustness in low-sample regimes. SGNNs maintain stable performance across most reduced-data settings, while XGBoost exhibits a pronounced degradation as data becomes scarce. Differences between the two methods are statistically significant across all training proportions (DeLong test with Holm correction at ). At the same time, SGNNs exhibit a noticeable drop in performance only under the most extreme 1% training regime.

These results indicate that, while extreme undersampling remains challenging, SGNNs’ reliance on low-dimensional pairwise classifiers enables more stable learning when the number of samples is small relative to the number of features, directly addressing the “curse of dimensionality". Moreover, graph-based representations enable SGNNs to capture higher-order feature interactions that are difficult to model with conventional models. At the same time, ensemble graph construction provides robustness to sampling variability across heterogeneous datasets.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that SGNNs offer a robust and scalable alternative to conventional machine learning models in diverse applications where high-dimensional data and limited sample sizes are the norm. The ability to retain high classification accuracy under such constraints makes SGNNs particularly well-suited for early-stage clinical research, modeling rare diseases, and other settings where data availability is inherently limited.

3.6. Robustness to Correlated Features

Complementary to the data-scarcity analysis in Section 3.5, we next examine robustness to redundancy in the feature space, a common characteristic of high-dimensional multimodal data where strong correlations and duplicated signals are prevalent. Such redundancy can inflate dimensionality without increasing information content and often degrades the stability of classical models through spurious associations and unstable estimation.

To examine whether explicit feature engineering is necessary within the SGNN framework, we performed a controlled robustness experiment using the foundation pipeline from Section 3.1. We duplicated the complete feature set and injected 5% Gaussian noise, effectively doubling the input dimensionality while introducing structured redundancy. We then applied the SGNN pipeline without any modification. As summarized in Table 5, performance changes for SGNN-based models remain small across all sparsification regimes, typically within ROC-AUC. In contrast, XGBoost exhibits the biggest absolute drop in performance under the same perturbation ( ROC-AUC), as indicated by the values in parentheses. This relative sensitivity highlights SGNNs’ robustness to redundant and noisy features.

Table 5.

Performance comparison for the foundation-setting classification task under dimensionality inflation and feature noise. We train models using the baseline configuration and report performance as macro-averaged ROC-AUC across cross-validation folds. Each table entry shows the ROC-AUC on the original and noise-augmented datasets, separated by a “/”. The higher value within each pair is underlined, and the best overall performance across all configurations is highlighted in bold. SGNN-based configurations exhibit consistently smaller deviations than the boosting baseline, indicating greater robustness to increased dimensionality and feature noise.

These results indicate that SGNNs are robust to moderate increases in dimensionality and feature-level noise, and that the graph construction and message-passing stages implicitly suppress irrelevant variation without requiring explicit dimensionality reduction. While standard preprocessing remains important for modality alignment and numerical stability, the SGNN pipeline reduces reliance on manual feature engineering, offering a practical advantage when working with complex, high-dimensional datasets.

3.7. Evaluation on Ovarian Cancer Proteomics Data

To extend the evaluation beyond UCI repositories and assess performance in a realistic biomedical setting, we conducted an additional experiment on an ovarian cancer serum proteomics dataset characterized by a high-dimensional, low-sample-size regime [40]. The dataset consists of 64 samples (28 ovarian cancer cases and 36 controls) with 100 protein features, representing a challenging setting affected by the curse of dimensionality.

We follow the same experimental protocol as in Section 3.5, evaluating model performance across different proportions of training data. However, because the ovarian cohort is small, we evaluate proportions from 25% onward: lower fractions would leave too few samples for a meaningful validation split and early stopping, making the training procedure unstable and the comparison less reliable. In addition to training on the ovarian dataset alone, we consider a foundation setting from Section 3.1, in which we augment the dataset with graph-structured samples from the pooled UCI datasets and feed them to the best graph-based model in this setting (GATv2 with minimum-connectivity sparsification and node features).

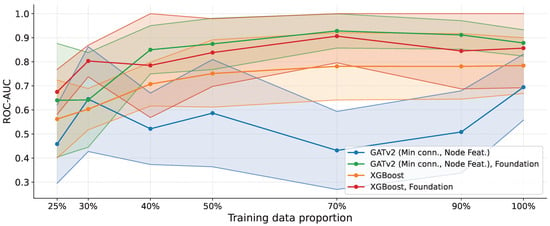

The results are shown in Figure 5. When trained only on the ovarian dataset, the graph-based model exhibits higher variance and underperforms the XGBoost baseline. This behavior likely stems from the difficulty of reliably learning informative relational patterns from a limited number of real-world noisy samples in an extremely high-dimensional feature space, where the combinatorial number of potential interactions exceeds the available supervision.

Figure 5.

ROC-AUC versus training data proportion on the ovarian cancer proteomics dataset. We compare GATv2 (minimum-connectivity sparsification with node features) and XGBoost, evaluated in both the ovarian-only and foundation settings (Foundation = Ovarian + UCI). Shaded regions indicate the standard deviation across runs. When trained only on ovarian data, the graph-based model exhibits higher variance and can underperform XGBoost in the low-data regime. However, with the foundation training, GATv2 achieves the highest ROC-AUC across most training proportions and exhibits substantially reduced variance, except for the smallest fractions (25% and 30%), where performance is more variable due to the limited sample size.

Notably, in the Foundation setting (Ovarian + UCI), the graph-based approach improves substantially, achieving the highest ROC-AUC across most training proportions and exhibiting a markedly reduced variance. This result suggests that heterogeneous training data provide richer relational evidence, enabling the GNN to learn more stable and transferable connectivity patterns. The main exception occurs at the lowest training fractions (25% and 30%), where performance becomes more variable, and the mean degrades, reflecting an unfavorable balance between the number of samples and the dimensionality of the feature space. Nevertheless, even in this regime, the Foundation-trained graph model remains stronger than both non-Foundation variants.

Overall, these findings indicate that combining synolitic graph representations with foundation training substantially improves robustness and sample efficiency in high-dimensional biomedical data, supporting the applicability of the proposed approach beyond standard UCI benchmarks.

3.8. Performance Analysis

In addition to predictive performance, we evaluate the computational efficiency of the SGNN pipeline, considering the costs associated with graph construction, training time, inference latency, and peak memory consumption. The results are summarized in Table 6 and reported over cross-validation folds.

Table 6.

Efficiency analysis. Graph construction time includes edge weight computation and sparsification. Training time is measured until early stopping.

Graph construction introduces moderate overhead for SGNN-based models, primarily due to the computation of edge weights and topology-aware node feature extraction. While augmenting nodes increases build time for both GATv2 and GCN, applying sparsification (such as ) substantially reduces construction cost by limiting edge density. Similar trends are observed during training and inference: attention-based GATv2 consistently incurs higher computational cost than GCN, whereas sparsification partially compensates for this overhead by reducing both runtime and memory footprint, even when richer node representations are used.

Memory usage further highlights architectural differences. GATv2 exhibits the highest peak memory consumption, particularly with node features enabled, while GCN remains significantly more memory-efficient across all configurations. In both cases, sparsification yields pronounced memory savings, reducing peak usage by an order of magnitude in the most compact settings. By contrast, XGBoost achieves minimal training and inference times but yields lower scores in conducted experiments.

Overall, these results show that the computational overhead of SGNNs is predictable and can be effectively controlled through sparsification. While graph-based models are more resource-intensive than classical baselines, structural filtering provides a practical mechanism to balance efficiency and performance, supporting the scalability of the SGNN pipeline in resource-constrained settings.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

In this study, we systematically evaluated Synolitic Graph Neural Networks (SGNNs) for high-dimensional tabular classification, focusing on the relative contributions of topology-aware node features and graph sparsification across multiple datasets and training regimes. The results confirm the working hypothesis that node-level structural information is the primary driver of performance and transferability, while sparsification mainly serves as a regularization and efficiency mechanism. Across both foundation and dataset-specific settings, enriching synolitic graphs with degree- and centrality-based descriptors consistently yielded the biggest gains for both GCN and GATv2, enabling SGNNs to outperform the strong XGBoost tabular baseline (). This result is consistent with prior parenclitic and synolitic studies, which show that graph topology encodes class-relevant structure in high-dimensional biomedical data. Sparsification exhibited a secondary, yet context-dependent, effect: attention-based models were insensitive primarily to edge removal in the foundation setting when informative node features were present. In contrast, moderate filtering or minimum-connectivity constraints improved generalization in the dataset-specific regime, particularly for GATv2. This result suggests that sparsification acts as a structural regularizer, suppressing dataset-specific noise while preserving sufficient relational pathways.

Generalization experiments further support the robustness of the SGNN framework. In leave-one-dataset-out evaluation, models augmented with topology-aware node features generalized substantially better to unseen datasets than those relying solely on synolitic structure, indicating that node-level structural descriptors capture graph properties that are more stable across domains than raw edge weights. Similarly, in low-data regimes, SGNNs maintained stable performance down to 10% of the training data, while XGBoost degraded rapidly, with a notable decline only in the extreme 1% setting (). This behavior supports the core motivation of synolitic construction: learning decision structure in many low-dimensional subspaces can mitigate the curse of dimensionality under limited supervision. Additional robustness was observed under artificial feature redundancy, where dimensionality inflation had minimal impact on SGNN performance compared to classical baselines. The ovarian cancer proteomics experiment further illustrates both strengths and limitations: while SGNNs trained solely on the small cohort exhibited higher variance, foundation-style training with heterogeneous synolitic graphs substantially improved stability and accuracy, suggesting that exposure to diverse graph structures can regularize relational learning in low-sample biomedical settings. From a practical perspective, SGNNs introduce additional computational overhead due to the construction of pairwise graphs and GNN training; however, sparsification provides an effective mechanism to control build time, memory usage, and inference cost. GATv2 offers higher accuracy at the expense of increased computational requirements, whereas GCN remains more resource-efficient, enabling trade-offs based on deployment constraints.

Future work should therefore focus on extending SGNNs to more realistic biomedical settings, particularly multimodal and non-stationary data. While the synolitic framework is modality-agnostic at the graph construction level, practical use in clinical scenarios will require modality-specific encoders and principled fusion, enabling multimodal synolitic graphs in which node representations are modality-aware, and edges capture clinically meaningful cross-modal relationships across structured variables, imaging, physiological signals, and text. In parallel, real-world biomedical data are often non-stationary due to population shifts and evolving acquisition pipelines, making static graph construction prone to performance drift; incorporating continual or dynamic graph learning through online graph refinement, incremental edge-weight updates, and continual parameter adaptation with mechanisms to mitigate catastrophic forgetting is therefore a natural extension [41,42].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z., E.M.M. and T.T.; methodology, I.S., A.S., A.L., R.N. and A.Z.; validation, I.S., A.S., A.L. and R.N.; writing—original draft preparation and further revision, I.S. and A.Z.; The team was formed at the SMILES-2025 summer school. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation (grant No 139-15-2025-004 dated 17 April 2025, agreement identifier 000000C313925P3X0002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used here is publicly available. The code for graphs construction and experimental evaluation was developed by the authors and is available at https://github.com/AlexeyZaikin/Synolitic-Graph-Neural-Networks (repository created on 27 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2402.06196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Villalobos, P.; Ho, A.; Sevilla, J.; Besiroglu, T.; Heim, L.; Hobbhahn, M. Position: Will we run out of data? Limits of LLM scaling based on human-generated data. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research (PMLR); JMLR.org: Brookline, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 235, pp. 49523–49544. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N. The AI revolution is running out of data. What can researchers do? Nature 2024, 636, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumailov, I.; Shumaylov, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Papernot, N.; Anderson, R.; Gal, Y. AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data. Nature 2024, 631, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, S.; Koren, S.; Rhie, A.; Rautiainen, M.; Bzikadze, A.V.; Mikheenko, A.; Vollger, M.R.; Altemose, N.; Uralsky, L.; Gershman, A.; et al. The complete sequence of a human genome. Science 2022, 376, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Huss, M.; Abid, A.; Mohammadi, P.; Torkamani, A.; Telenti, A. A primer on deep learning in genomics. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, C.B.; Demichev, V.; Wendisch, D.; Michalick, L.; White, M.; Freiwald, A.; Textoris-Taube, K.; Vernardis, S.I.; Egger, A.S.; Kreidl, M.; et al. Ultra-High-Throughput Clinical Proteomics Reveals Classifiers of COVID-19 Infection. Cell Syst. 2020, 11, 11–24.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A focus on single-cell omics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 485. [CrossRef]

- Schübeler, D. Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature 2015, 517, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sviridov, I.; Egorov, K. Conditional Electrocardiogram Generation Using Hierarchical Variational Autoencoders. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13469. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yin, Y.; Glampson, B.; Peach, R.; Barahona, M.; Delaney, B.C.; Mayer, E.K. Transformer-based deep learning model for the diagnosis of suspected lung cancer in primary care based on electronic health record data. EBioMedicine 2024, 110, 105442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnenführer, J.; De Bin, R.; Benner, A.; Ambrogi, F.; Lusa, L.; Boulesteix, A.L.; Migliavacca, E.; Binder, H.; Michiels, S.; Sauerbrei, W.; et al. Statistical analysis of high-dimensional biomedical data: A gentle introduction to analytical goals, common approaches and challenges. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Huang, K.; Yang, D.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, X. Biomedical Big Data Technologies, Applications, and Challenges for Precision Medicine: A Review. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2300163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berisha, V.; Krantsevich, C.; Hahn, P.R.; Hahn, S.; Dasarathy, G.; Turaga, P.; Liss, J. Digital medicine and the curse of dimensionality. Npj Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; de Las Casas, D.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivonosov, M.; Nazarenko, T.; Ushakov, V.; Vlasenko, D.; Zakharov, D.; Chen, S.; Blyus, O.; Zaikin, A. Analysis of Multidimensional Clinical and Physiological Data with Synolitical Graph Neural Networks. Technologies 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Z.L.; Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Elangovan, K.; Cheng, H.; Moova, P.; Soetikno, B.; Nielsen, C.; Pollreisz, A.; Ting, D.S.J.; Morris, R.J.T.; et al. Generative artificial intelligence in medicine. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3270–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in health and medicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Stark, H.; Jegelka, S.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R. Graph neural networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitwell, H.J.; Bacalini, M.G.; Blyuss, O.; Chen, S.; Garagnani, P.; Gordleeva, S.Y.; Jalan, S.; Ivanchenko, M.; Kanakov, O.; Kustikova, V.; et al. The Human Body as a Super Network: Digital Methods to Analyze the Propagation of Aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, M.; Alcazar, J.M.; Carbajosa, J.V.; Paez, M.G.; Papo, D.; Sousa, P.; Menasalvas, E.; Boccaletti, S. Parenclitic networks: Uncovering new functions in biological data. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, M.; Papo, D.; Sousa, P.; Menasalvas, E.; Nicchi, A.; Kubik, E.; Boccaletti, S. Combining complex networks and data mining: Why and how. Phys. Rep. 2016, 635, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitwell, H.J.; Blyuss, O.; Menon, U.; Timms, J.F.; Zaikin, A. Parenclitic networks for predicting ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 22717–22726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarenko, T.; Whitwell, H.J.; Blyuss, O.; Zaikin, A. Parenclitic and Synolytic Networks Revisited. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 733783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivonosov, M.; Nazarenko, T.; Bacalini, M.G.; Vedunova, M.; Franceschi, C.; Zaikin, A.; Ivanchenko, M. Age-related trajectories of DNA methylation network markers: A parenclitic network approach to a family-based cohort of patients with Down Syndrome. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 165, 112863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichev, V.; Tober-Lau, P.; Lemke, O.; Nazarenko, T.; Thibeault, C.; Whitwell, H.; Röhl, A.; Freiwald, A.; Szyrwiel, L.; Ludwig, D.; et al. A time-resolved proteomic and prognostic map of COVID-19. Cell Syst. 2021, 12, 780–794.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichev, V.; Tober-Lau, P.; Nazarenko, T.; Lemke, O.; Kaur Aulakh, S.; Whitwell, H.J.; Röhl, A.; Freiwald, A.; Mittermaier, M.; Szyrwiel, L.; et al. A proteomic survival predictor for COVID-19 patients in intensive care. PLoS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.; Alon, U.; Yahav, E. How Attentive are Graph Attention Networks? arXiv 2022, arXiv:2105.14491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkes, E.M.; Allohibi, J.; Gorban, A. Fractional Norms and Quasinorms Do Not Help to Overcome the Curse of Dimensionality. Entropy 2020, 22, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearst, M.A.; Dumais, S.T.; Osuna, E.; Platt, J.; Scholkopf, B. Support vector machines. IEEE Intell. Syst. Their Appl. 1998, 13, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In KDD ’16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PyTorch Geometric Documentation. Available online: https://pytorch-geometric.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- XGBoost Documentation. Available online: https://xgboost.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/index.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. The curse(s) of dimensionality. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaikin, A.; Sviridov, I.; Oganezova, J.G.; Menon, U.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Timms, J.F.; Blyuss, O. Synolitic Graph Neural Networks of High-Dimensional Proteomic Data Enhance Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Qin, Y.; Wang, B.; Guo, L.; Jia, L.; Cheng, X. Evolvable graph neural network for system-level incremental fault diagnosis of train transmission systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 210, 111175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ye, J.; Peng, H.; Wang, F.; Yu, P.S. Self-supervised continual graph learning in adaptive riemannian spaces. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 4633–4642. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.