Abstract

Health and safety concerns at construction sites have become increasingly significant, especially with the rapid technological development and the opportunities it brings. Since fall-from-height incidents are the most frequent construction accidents in the field, this paper focuses on a fall risk prevention method for building construction sites by integrating algorithm-based techniques with BIM models and introducing a smart adaptive system that automatically detects danger zones and places requiring safety equipment regardless of the layout complexity and design modifications. Moreover, the work reveals the optimal quantities and material takeoffs for the suggested safety plan over time, based on the construction sequence. It provides a 4D BIM simulation of building projects, in which the appropriate configurations, quantities, lengths, and costs of the required safety equipment can be derived at any chosen time interval within the construction stage.

1. Introduction

1.1. Construction Accidents

The high rates of occupational accidents related to the construction industry are major concerns, although there are numerous studies and reports published regarding health and safety assessment and construction accident prevention [1]. In contrast with other industries, construction industries are not mechanized; physical effort from laborers in the field is essential for accomplishing projects. Unfortunately, the dark side of that is apparent in the literature with the shocking number of fatal and non-fatal construction accident rates worldwide [2,3,4]. Hence, the construction industry is classified as one of the most dangerous work environments based on the statistics, so there is always room for enhancing and developing protection systems to reduce and eliminate this risk for a safer work environment and industry [5,6].

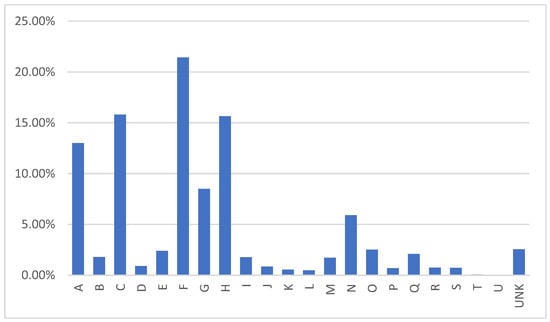

Statistical reports from various countries around the world have indicated high-frequency rates of occupational accidents at construction sites [7,8]. Based on European statistical reports on the incidence rates of fatal accidents across various business activities, from 2011 to 2020, the construction sector’s rates are undisputedly the highest, accounting for more than 21% of the total, as presented in Figure 1 [9]. Similarly, the highest rates of fatal work injuries in the U.S. belong to the construction industry [10].

Figure 1.

Fatal accident rate (A—Agriculture, forestry, and fishing; B—Mining and quarrying; C—Manufacturing; D—Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; E—Water supply, sewage, waste management, and remediation activities; F—Construction; G—Wholesale and retail trade and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; H—Transportation and storage; I—Accommodation and food service activities; J—Information and communication; K—Financial and insurance activities; L—Real estate activities; M—Professional, scientific, and technical activities; N—Administrative and support service activities; O—Public administration and defense, compulsory social security; P—Education; Q—Human health and social work activities; R—Arts, entertainment, and recreation; S—Other service activities; T—Activities of households as employers, undifferentiated goods- and services-producing activities of households for own use; U—Activities of extraterritorial organizations and bodies; UNK—Unknown NACE activity).

There are different classifications of construction accidents, which may vary in causes, locations, and prevention procedures. Among these categories, Falls From Heights (FFH) are the most common lethal accidents ever recorded in the industry [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Studies and statistics from all around the world emphasize the issue; in Taiwan, FFH contributed to more than 30% of total construction accidents [14]. Based on data collected from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) from around 7500 construction accidents, FFH accounted for 35% [16]. Another piece of evidence from the Nigerian construction market, fall incidents were among the most frequent site tragedies [13]. In the Arabic Gulf region, and based on another sample of more than 500 mishaps from various building sites distributed across five countries: Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, and Bahrain, FFH and struck-by-incident were the most frequent accidents in the field, accounting for 30%, and from the total analyzed fall incidents, more than 40% caused severe injuries, and more than 10% were fatal [12]. According to data collected from construction laborers in Zambia’s capital city, hoist-and-fall accidents are attributed to the most repeated accidents [11]. In precast construction projects, the same issue arises, although they are generally considered safer compared to other types of construction. In these cases, FFH presented 48% of the total construction accidents among the 125 analyzed case studies [15].

A report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (the U.S. construction market is one of the largest worldwide) showed that in 2019, there were 1102 fatal accidents in the construction industry, combining both the private and public sectors. These incidents represented around 21% of the total occupational fatalities. Falls, slips, and trips were the most common drivers for fatal events, with around 40% of all fatalities. This represents a relative 30% increase compared to the same values for 2018. Interestingly, most of the fatal slips and falls are from falls to a lower story. For nonfatal injuries, slips-falls and trips still dominated the top, most frequent nonfatal accidents at construction sites, accounting for 32% over the same year [19]. On the domestic level, and based on a study of occupational accidents between the period from 2001 to 2020, the Hungarian construction industry accounted for the highest fatal and non-fatal mishap rates among other industries. A detailed analysis of the accident reports from 2014 to 2018 indicated that the majority of construction accidents on the Hungarian construction projects were caused by falling to lower levels [20].

1.2. Causes and Locations of Fall Accidents

It is undeniable that laborers’ experience has a significant impact on the frequency of fall accidents. More than 80% of fatal fall accidents involved workers with less than one year of experience in the profession, which sheds light not only on the protection procedures against fall risks but also on the awareness level among workers [17]. Hence, a Korean study concentrated on raising awareness of health and safety risks among workers who were expected to face fall incidents based on probability prediction models [21]. On the other hand, it was observed that the lack of needed safety equipment contributed to causing fall accidents. Among the distribution of errors that contribute to falls, the second most frequent error is inoperative or uninstalled safety equipment or devices [16]. Similarly, another study showed that the most frequent fall causes are unguarded openings/edges, bodily actions, and poor work practices, accounting for 16.7%, 10%, and 7.1%, respectively [17].

The locations where fall incidents usually happen are marked as danger zones. Although modular construction projects are classified as safer to deal with compared to other types of structures, since 70–80% of the work is completed offsite, FFH are still the dominant type of accident even at the relatively safer prefabricated building projects [22]. At this kind of construction type, the danger locations are distributed in the following order: roofs, structures’ edges, ladders, and floor openings, with frequency rates of 34.5%, 25.5%, 12.7%, and 9.1%, respectively [15]. In general construction building projects, the fall location is distributed in the following order: scaffold, through floor opening, building girder, and slab/roof edge, with frequencies of 30.4%, 20.6%, 11.3%, and 10.5%, respectively.

1.3. Regulations and Equipment for Fall Prevention

Fall accidents can be reduced to low levels by applying suitable prevention systems. Working at high levels does not necessarily imply a high probability of falling, like with cranes, in which the least common accident is falling, since cranes are fully guarded with safety rails [23]. Based on the construction regulations in the UK, several duties and responsibilities are assigned to planners and contractors alike regarding construction site safety in various situations and at different project stages [24]; health and safety planners and managers ensure that the process starts from the early design stages by identifying the hazards and the required safety tools, then it proceeds with the construction phase which would be executed in the field [25]. The majority of safety regulations were introduced and derived from official authorities, like the Health and Safety Executive’s Construction Division (UK), to improve and manage health and safety planning by highlighting slips and trip risks while working at heights; examples of risks include assessing work at height, roof work, scaffolds, ladders, and fragile surfaces [24].

According to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations, there are two types of fall protection systems: conventional and additional. The first combines guardrails, safety nets, and personal fall arrest systems, while the second includes warning lines, controlled access zones, and safety monitoring systems; protection from falling objects can also be provided by guardrails with fixable toe boards [26]. Guardrails are simple, affordable, flexible, and easy-to-reach fall safety systems, so they are the most widely spread and applicable edge protection safety equipment, with the potential to prevent human and object fall accidents thanks to the ability to fix toe-kick boards at the bottom level of the guardrails [26,27,28]. Hence, guardrails are practical fall protection solutions, and they can be installed in building projects whenever applicable. They should be strong, rigid, and/or fixed to a structure to withstand loads [29].

According to UK regulations, guardrails should be at least 95 cm high above any side from which workers are liable to fall. They are required to have a sufficient number of intermediate planks or suitable alternatives so unprotected gaps would not exceed 47 cm, and the toe boards and kick guards should be placed at the bottom of the guard rail to avoid the risk of objects rolling to lower levels [30]. Similarly, guardrail systems approved by OSHA should be 107 cm in height (±8 cm), and should have the following: horizontal mid-rails installed at a midway height between the top and bottom planks; vertical balusters installed no more than 48 cm apart; openings between horizontal/vertical members that are no more than 48 cm; guardrails that can withstand 890 N force applied in down/outward direction within 5 cm at any point along the top edge; mid-rails that withstand minimum 667 N force without failure; top/mid rails that are at least 6 mm in diameter or thickness; and toe kicks with a minimum vertical height of 9 cm and a maximum of 5 mm clearance to the working-walking surface, that are solid and, in case of needed openings, do not exceed 3 cm, and can withstand a force with minimum 222 N [31]. Likewise, based on data derived from domestic Hungarian safety regulations and consultations with local contracting companies and practitioners, the guardrail system should be a minimum of 1 m high, and not exceed the length of 3 m, and the gap between the mid-rails should not exceed 30 cm; the cross-section height of the used planks should be a minimum of 12 cm. They mainly apply modular systems, which have fixed measurements. Table 1 presents a summary of the available guardrail specifications [32].

Table 1.

Guardrails specifications according to the construction safety regulations in the USA, the UK, and Hungary.

1.4. Algorithms in Safety Support

Sundry attempts appear in the literature to implement algorithms and AI-based methods in health and safety topics to assist in many life aspects [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. In the construction industry, using algorithms for assisting on-site safety is not restricted to building projects; infrastructure and civil engineering works also have potential in algorithm-based and building information modeling (BIM) methods to provide reliable information to control other construction projects. For instance, flow check algorithms of confined spaces at road construction sites can help to increase the safety of road maintenance workers, supported by detectors and warning devices [40]. Similar efforts exist to serve algorithm-based methodologies, which comprise sensors in their workflow [41,42]. Previous studies have focused on the safety of the surrounding built environment of the construction sites within the project area, developed warning algorithms for mobile machinery, and used employee sensors, Wi-Fi connections, and the Internet of Things to detect risk zones and suggest safer routes in real time [42]. Meanwhile, other work focused on fall-from-height detection by developing deep-learning models to simulate fall hazards with the help of embedded sensors and introducing a prediction algorithm that relies on acceleration values [41]. Early efforts in this field form the basic foundation for the monitoring and control of fall hazards. As an algorithm approach that combined several modules, the outputs of the system were warnings, written reports, and graphical illustrations regarding the location and continuity of safety equipment, but it was a more or less 2D-based representation rather than 3D [43].

1.5. Algorithm and BIM-Based Construction Safety and Fall Prevention Support

Previous studies implemented BIM-based techniques to raise the level of safety at construction sites. In these studies, the implementation was approached in various ways regarding the methodology of the workflow and the studied construction accident or safety regulation [5]. BIM capability in safety comes from the fact that the models mostly include all project elements and their interactive relations with each other, so with the help of these models, safety issues can be interpreted and detected early in the design stage [44,45]. BIM models can be used in advanced safety planning approaches for building projects [46], even though they are not limited to building projects; BIM platforms have been used to provide reliable information to control other construction projects, for instance, confined spaces in infrastructure works [47]. Despite that, there is still room for enhancing BIM usage in the safety field, keeping in mind that safety equipment elements, for example, the number of Revit families regarding safety at construction sites (guardrails, safety nets, etc.), are limited in BIM libraries. This demonstrates how safety remains as a secondary concern, even in digital construction [48,49]. BIM models can also generate heat maps through time for construction projects, supported by developed add-ons and safety-leading indicators [50].

By combining BIM and Prevention Through Design (PtD) methodologies, most risks can be identified, planned, and dealt with in the early design stages, and this can significantly decrease the chances of fall hazards at the construction sites [48,51,52], since more than 40% of safety issues can be identified and solved in the early stages of the project [44], especially in fall hazards at construction sites, in which BIM models help to identify and eliminate the potential fall hazards at the early planning stages, and prevent potential hazards to unwittingly be built and scheduled in the construction [53]. Moreover, BIM models can assist in simulating real-life safety risks at construction sites, due to the difficulties of testing that at real projects [54]. BIM models can also be combined with other technology tools to control safety at projects, such as GPS, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), sensors, beacons, and monitoring systems [47,55,56,57,58].

As long as falls are among the most frequent construction site accidents, there are many attempts in the literature to use BIM models supported with algorithm-based techniques to reduce fall accidents [46,51,53,59,60]. Under the topic of safety checking and safety rules checking, many papers have used algorithms to assure the safety quality of BIM models and the application of safety regulations, by developing Algorithms in a plug-in form, which can check the Industry Foundation Class (IFC) BIM files [46]. A similar methodology is introduced to identify and avoid construction hazards during the planning, or PtD, by reporting why, when, where, and what safety procedure is needed to avoid the fall danger as an automatic safety rule check supported by algorithms [51]. The introduced methodologies have left some room for development and limitations that present opportunities to resolve and evolve in future research; some of these limitations are the difficulty of restarting the system manually whenever a model object and its attributes have been modified, the lack of dynamic adaption for construction sequence, and the lack of visual representation [46]. On the same level, other proposed safety-rule checking systems had similar limitations, like the need for manual effort in some rule interpretation in terms of regulation translation to machine-readable codes, and due to the constant change in the construction environment, it was challenging to represent all hazards in real-time reference [51]. Comparably, when a design change occurs, extra efforts are needed using manual modeling; the level of development and quality may need to be improved further to meet practitioners’ needs, especially to overcome the lack of information at some locations of the model (the connection between wall/column and slab detail would not be automatically modeled and placed) [53]. The power of the previously proposed methodologies lies in predicting the danger zones early in the design and planning stage with the help of the developed algorithm, which sheds light on the potential of BIM-based safety planning [46,51,53]. But the most critical limitations can be summarized in the difficulty in covering complex construction conditions and geometries by safety-rule checking systems, which is a downside in relation to present-day construction flexibility in terms of geometry configurations, and the lack of timely, optimal quantity take-offs and installation/removal schedules for safety equipment [46,51,53]. There are many software tools to check the quality of BIM models, like Nemetschek Solibri Model Checker, Trimble Tekla BIMsight, and Autodesk Navisworks Manage. These software tools can assist in safety-rule checking and reporting [61]. Automatic fall-safety checking using BIM would avoid many downsides, like errors and delays that are caused by manual safety checking [62], considering the fact that using safety-rule-checking software tools requires knowledge in exporting files with various formats among several software tools [60,62].

Algorithms and BIM models can be used to identify fall risk variables as factors, by extracting data and calculating the fall-risk probabilities, by applying these probabilities to algorithm simulation, to plan the most suitable operational route leaning on fall risk and distance factors (by simplifying the construction site area to a coordinate plane) [59]. Similarly, it can also be used to introduce ontology models, to support a better description of knowledge concepts in the domain of construction safety, especially in fall hazards [63]. Interestingly, the possibility of combining visual programming with BIM models to detect fall hazards is also applied at the excavation stage to avoid fall hazards, supported by Rhinoceros 3D, Grasshopper 3D, and Autodesk Revit [60]. On the other hand, 4D BIM (3D BIM model + time) supported by Navisworks simulation has been introduced as a construction management method that assures more reliable construction sites from the point of view of construction accidents generally, and fall hazards particularly [48]. Another study applied the SYNCHRO 4D software tool to manipulate data derived from safety regulations from OSHA, local safety experts’ guides, and BIM models, to generate a 4D BIM model, which can be used to identify the risk by a clear picture of the work site and support training sessions for construction workers to clarify the risks that they will face [49]. Nevertheless, the lack of combining 4D BIM with an automatic algorithm-based approach for applying safety rules and equipment at 3D models by taking into account the time factor, the construction sequence, and the optimal quantity takeoff and bill of materials is rarely found among the studies [46,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,59,60,62]. BIM- and algorithm-based methods are also used to automatically generate safety schedules by identifying the possible hazards associated with each construction activity and time interval, for instance, during excavation activity, FFH and transportation accidents have a high probability to occur [64].

In this research, the introduced methodology can be classified under the PtD category with the FFH focus, by combining BIM, algorithms, and construction scheduling. The work will develop an advanced algorithm that not only checks danger zones at the 3D BIM model level but also incorporates changes and automatically places the required safety elements at the exact needed time by simulating the construction stage.

2. Methods and Procedures

2.1. Initial Information

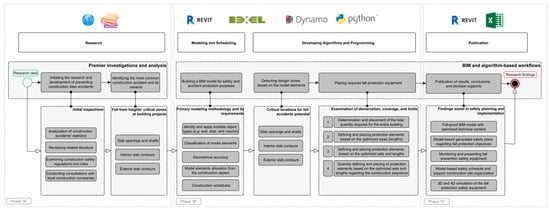

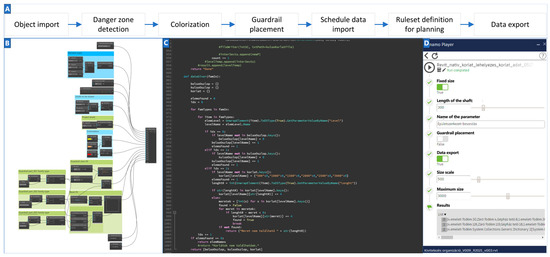

The research methods were divided into three main sections, as shown in Figure 2. The first was the review of regulations, rules, the literature, and resources, which were translated into programming language. The second was the BIM rule definition and the modeling process development. The third was the coding and the evaluation of the results.

Figure 2.

Detailed workflow of the research.

The first section, represented in Phase “A” (Figure 2), includes the identification and recording of the characteristics, spatial position, and safety requirements of the situations and structures that may be considered critical from the point of view of accident prevention during construction.

This research and development project focuses on fall and drop protection, considering the statistical data presented in Section 1. As a first step, we digitized the part of the Hungarian health and safety regulations and rules that we had identified as necessary for the correct functioning of our application. From the huge number of technical specifications and rules, we developed parameters that can be understood by the software. In preparation for future developments of the application, the following input information was recorded as variable parameters:

- -

- the minimum and maximum size of the railings;

- -

- size range of the railings;

- -

- length of the side of the shafts;

- -

- distance between columns themselves and the ends of the railings;

- -

- the height distribution of handrails;

- -

- number of equipment (balusters, posts, railings according to their sizes).

In the algorithm, these are used to define the operating rules and logic of the application. However, in order to ensure the functionality of the program, a BIM model for safety use created in accordance with the primary modeling methodology shown in Phase “B” (Figure 2) is needed as a second step of input data. We aimed to define the simple and general requirements, where the following rules must be followed:

- -

- Always use the correct object type for the building structure during modeling. This means that in the authoring tool, the modeler must use the wall tool for walls, the slab column tool for columns, etc. It is essential because the information content of the model elements can vary depending on the different objects. The program uses this information to identify elements and their geometries.

- -

- Standardized classification systems must be used to have more identification possibilities. During the research, the Uniclass system was used to support the filtering and grouping of elements.

- -

- It is also essential that the spatial positioning (e.g., building level) and the connection of the model elements are as accurate as possible within the capabilities of the modeling tool. This is important not only for the graphical representation but also for the investigations that the algorithm will perform (e.g., mapping of walls or pillars that cut the edges of the slab).

- -

- In cases where the full functionality of the fall protection algorithm is to be used, it is essential to separate the model elements according to the real construction and to link them to the information of the construction schedule. The development of a model-based construction schedule may be an additional task; however, it shall be performed in the case of on-site accident prevention model use.

2.2. Methodological and Logical Description of the Algorithm

If the occupational health and safety information is available and captured, and the BIM model has been built according to the appropriate rules, the use of the algorithm can be started. The first step of the process is to check the quality and compliance of the BIM model with the program codes. After the program has run, the incorrectly placed or misclassified model elements are shown graphically. If the algorithm detects errors, they need to be corrected in the modeling software. If no issues are found, the algorithm will generate the safety model elements as described in the following sections.

In developing the algorithm, we used the Autodesk environment for modeling purposes and for programming the algorithm in order to achieve the highest level of software collaboration. In this case, we used the visual programming extension of Autodesk Revit Dynamo as a programming environment, within which we wrote our code using the IronPython 2.7 programming language version.

In addition, we also needed to carry out additional development to support the extraction and maintenance of information related to the schedule (the time scheduling of construction). For this purpose, we used the BEXEL Manager 24 software and its development environment, into which the models created in Autodesk Revit software can be easily transferred using an add-on. There is no need to perform various file conversions (e.g., IFC export), so a more reliable geometry and information maintenance procedure can be created. The script is written in the C-Sharp (C#) programming language developed by Microsoft and runs in the .NET Framework environment.

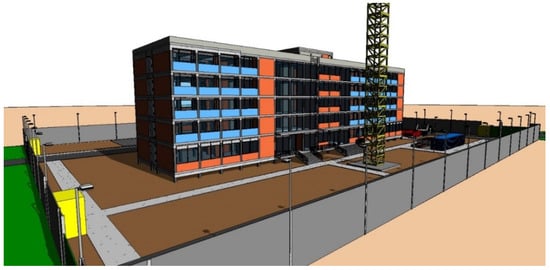

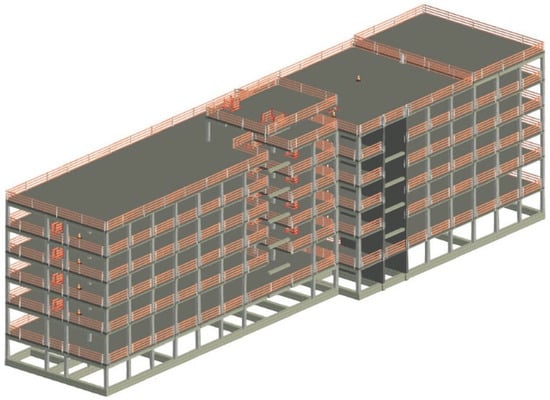

2.2.1. The BIM Model Used

The BIM model used for algorithm-based processes is a fictitious building design. Nevertheless, it was designed and modeled according to a reinforced concrete pillar frame structural system used in reality. The structural system of the building is complemented by reinforced concrete bearing walls, ceramic walls, monolithic reinforced concrete beams, and slabs, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the building.

The model also followed the modeling principles described previously in Section 2.1. It did not require any special procedure other than those listed. Its element connections were accurate and followed a construction principle, and all model elements were selected and classified using the appropriate software tool. In addition, the model had the starting and ending dates for the construction schedule. The possibility of updating the dates to track changes during construction was also developed (Section 2.2.4).

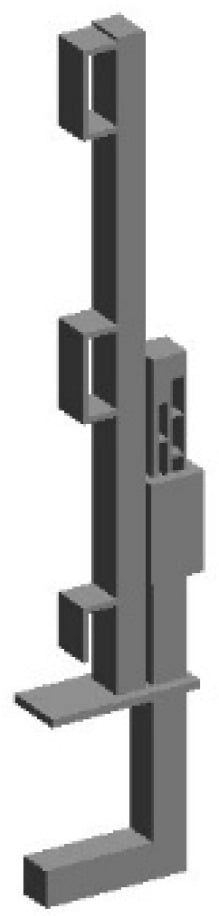

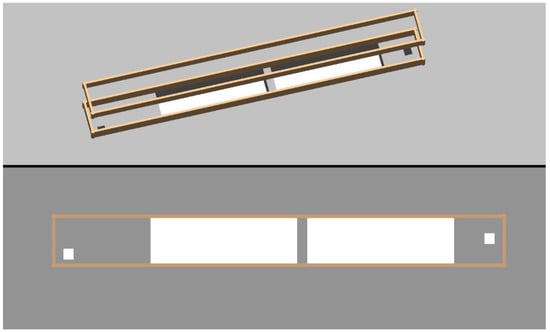

2.2.2. Safety Components Warehouse

For the algorithm to generate sufficiently detailed and accurate 3D views, and after creating 2D plans and material takeoffs, it is necessary to model safety element components. The content of the warehouse may contain individually modeled elements or objects downloaded from the manufacturer’s websites, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Modeled guardrail post according to the manufacturer’s specification.

The algorithm can apply any safety object during the analysis and modeling phase. In this case, 1 m high handrail posts with a height of 12 cm and a maximum length of 3 m (at a 50 cm scale) were created and placed in the required positions.

2.2.3. Operation of the Algorithm

The input parameters, correctly built BIM models, and safety element components constituted a good starting point for running the algorithm [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Representation of the workflow (A), algorithm (B), Python code (C), and interface (D).

The first task of the application is to analyze the model elements in the BIM model according to building structures. After gathering all the structural elements, it selects the walls, slabs, and columns.

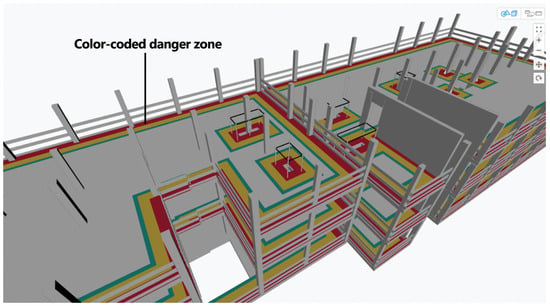

In the second step, the algorithm identifies the danger zones. From a fall-protection point of view, these are located at the edges of the slabs and around internal shafts and dilatations. In this step, the algorithm examines the spatial positions of the slabs compared to the ground and to each other, then filters out the model elements located at high levels and maps the danger zones for the latter as shown in Figure 6 (e.g., it is not necessary to install fall protection systems along the outer contour of the slab at ground level, but it is mandatory for slabs located at high level).

Figure 6.

Representation of danger zones in 3D according to the distances from the edges. (Red—dangerous, Orange—moderately dangerous, Green—low risk).

Then, the geometries of the slabs are split into sides in order to select the top plane of the slab elements. This allows for the slab contours, in the form of closed contours, to be identified for further processes. The algorithm then separates the collected contours and separates the outer and inner slab edges. Based on the results of several examinations, it can be taken as a basic assumption that the longest of the closed contours of a slab element will always be the outer edge of the slab. The other contours, collected by the algorithm in a separate list, will be the contours of the shafts or openings of the slab. This will allow for the separate handling of the outer and inner slab edges in subsequent processes and analyses.

The next step is to identify and examine the slab contours, where the edge length, position, and character are determined. If the contour of the slab, or a part of the slab contour, can be covered by simple geometry (straight line, rectangle, or square), then a simple calculation can be used to determine the track along which the safety components are to be placed. The developed algorithm simplifies the small differences in the contour of the slab (25 cm in or out of the vertical plane of the contour) and takes them into account with an idealized path (these differences are not tracked in real environments). In addition, the algorithm analyzes the relationships with other model elements (walls, columns) and follows the principle that safety elements should only be placed in positions where there is a risk of falling off the edge of the slab. These are identified by the algorithm using geometric fit analysis and collision search. If it finds an object geometry that intersects the edge of the slab, then it splits the contour line according to the intersection. For instance, if the path intersects a column or wall, the line length that can be covered by the bottom surface of the column or wall is considered a separate line segment after the procedure.

After the geometry analysis, the algorithm simplifies the paths and filters out the parts where the exact geometry is not relevant. In the next step, a continuity check is performed to ensure the geometry quality of the resulting path. This is a crucial task because if there is an error at this point, the elements to be placed later will not be in the correct position.

In summary, the algorithm has been designed with an approach that is able to adapt and place any type of safety elements according to the characteristics of the building structure.

Preliminary Analysis of Internal Openings

After the identification and classification of the slab edges, the algorithm performs additional analyses to categorize the internal openings. In the first step, the algorithm examines the spatial relations of the openings and then analyzes their size and shape. If the distance between two openings is less than twice the shortest railing, the algorithm will consider the openings as one. If their combined size exceeds the size that can be covered, they will be included in the group of openings to be protected by railings. The program also classifies in the same group of openings those whose surface or size does not allow simple covering. Those openings that are in the category of coverable, with or without merging, are covered by a steel plate in the model by a specific 3D object.

Covering of Internal Openings, Railing of External–Internal Slab Edges

Defining the possibility of a safety enclosure (coverable, enclosable) is one of the fundamental requirements for the placement of model elements. Another essential input is the definition of positions, dimensions, and the number of elements, which will allow the algorithm to use the previously created and selected Revit Family elements (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of the model elements created for this research.

The algorithm considers the relations of the original slab edge lines, the parts of the slab that can be excluded due to the intersecting building structures, the angles enclosed by the edges, and the shape of the overall form. In the latter case, the algorithm generates the best-fitting enclosing rectangle around the openings [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Representation of the generated rectangular around 4 shafts.

In the case of small openings, the algorithm places posts in the middle of the optimized rectangular. In the case of openings and external slab edges that would be enclosed by railings, the algorithm places the balusters, at first, 20 cm away from the endpoints of the sections (this value can also be manipulated due to the requirements), and then, on the contour lines. After that, considering the geometry of the railing family, the algorithm calculates the height positions.

When the length of the railings is determined, the algorithm performs a comparison, comparing the side lengths of the optimized path with the applicable rail lengths as predefined. As a result, the fixed (scale) lengths of the railings will be used in the placement method. If the stock of usable safety elements is configured (e.g., how many of each size of railing or balusters are available), the algorithm can take this into account.

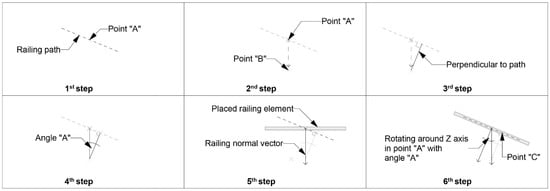

Before placing the safety elements, they need to be rotated in the correct direction. This ensures that the model elements are always oriented in the direction of the defined path. The placement rules and their rotation into position are as follows [Figure 8]:

Figure 8.

Positioning rules and methods.

- -

- The algorithm finds the center point of the slab contour segments (Point “A”) and then shifts it in the direction of the Y axis (Point “B”). If the generated point (Point “B”) is on the starting line, it is shifted from the center point in the direction of the X-axis.

- -

- The algorithm then connects the new point (Point “B”) and the center point (Point “A”) (2nd step) and then creates a perpendicular from Point B to the initial line (3rd step). After this process, it determines the angle enclosed by the two new segments (from Point “A” to Point “B” and the perpendicular segment) (4th step). If the edge of the slab is parallel to the X or Y axis (shown as a horizontal or vertical line in the figure), the angle will always be 0 degrees. In this case, it is necessary to examine whether the new point (Point “B”) falls within the slab area. If it does not, the algorithm has to add 180 degrees to the rotation angle. If that new point (Point “B”) is offset in a direction parallel to the Y axis, then an additional 90 degrees must be added to the rotation value.

- -

- The angle of rotation is then added to or subtracted from the angle between the lines. The process of adding or subtracting depends on whether the intersection point generated by the perpendicular alignment (Point “C”) is to the right or left of the new point (Point “B”) of the normal vector (the angle of the straight lines must be an angle less than 180 degrees).

After the correct direction and all positions have been determined, the safety model elements can be placed. During the procedure, the balusters are positioned with a 20 cm offset, and the horizontal railing elements extend to the end of the slab edge as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Safety equipment placed on the edge of the slab and slab openings.

Optimization-Oriented Use of Safety Elements

Once the safety elements have been generated for the building, one of the most important processes is the optimization of the use and reuse of railings within the construction site. The possibilities for this will be available using the previously mentioned scale and stock.

The sizes can be fixed for each type of railing, ensuring that the algorithm can only create them in the sizes specified in the product specification. Currently, this can be set in the algorithm using minimum and maximum values. The definition of the stock allows for the simulation of a real site element storage (depot) with a defined size and a number of balusters, railings, steel plates, etc., considering sustainability objectives.

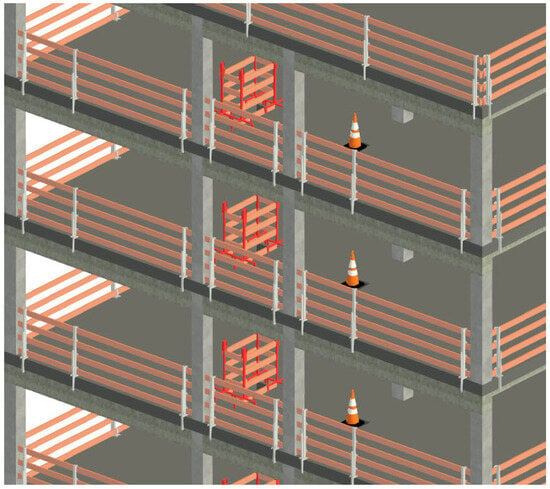

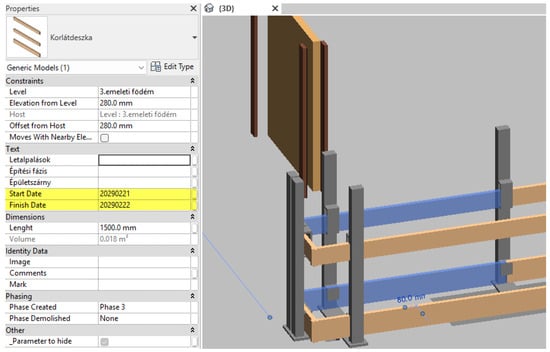

The third aspect of the automated planning is the time factor of the execution, which can be captured by performing a time-based quantitative optimization [Figure 10].

Figure 10.

Representing the start and end date properties in the objects.

Data Exports Using the Algorithm

After all the necessary tests are run and all the model geometries are modeled by the algorithm, it is necessary to add the results to a dataset that can be published. The algorithm can extract quantitative data of safety model elements, which allows for the comparability of different design methodologies (total quantity calculation, stock-based design, schedule-based design) and results. They can also support equipment purchases or stock availability and scheduling.

The algorithm provides the following export options:

- -

- total quantity required for the whole building;

In this case, a calculation can be made to determine the number of balusters, railings, and coverings needed to protect the entire building from dropping and falling (Figure 11). This calculation does not consider either stock- or schedule-based optimization but only provides an aggregate number.

Figure 11.

Safety equipment (guardrails and cover plates) placed in the BIM model.

- -

- the quantity for a certain moment in time;

It is an improved solution, where the algorithm allows for the calculation of the values needed at certain moments of the construction, based on the construction schedule. It also calculates stock and installed values. The algorithm can be configured to specify the time at which you want to see the quantities, and then it checks the building’s completion. Where the path meets a built structure, it modifies the baseline of the slab and skips the segment concerned. Based on these procedures, the required amount of safety equipment for the given time can be collected and displayed. In this case, the 3D visualization methodology is achieved by updating the algorithm in the background so that only the elements that exist at the time are visible. Elements that are yet to be built according to the schedule remain hidden, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Schedule-based calculation and 3D representation of safety equipment at a certain moment (“A”—placed guardrails; “B”—removed guardrails in the positions of parapet walls).

- -

- quantity for a time interval;

Collection at certain periods may be relevant; as a last feature, the algorithm is also prepared for the possibility of producing time interval-based (e.g., daily) statements, which also requires the implementation schedule. In this case, the algorithm also considers the maximum quantity that may be required within a given time interval, allowing for an optimized site stock quantity to be planned.

In the time interval-based stock quantity calculations, different tolerances can be used to increase and decrease the quantity of building site stock. It means that if the daily required quantity exceeds the stock, for example, a margin of tolerance of 5% is added to the stock quantity. It shows the number of missing elements of the daily targets. In the case of stock reduction, a threshold of 20% has been set, which means that if the stock quantity exceeds the required quantity by 20%, the virtual on-site depot will automatically be reduced. This is relevant in the case of rented stock or to meet the needs of several projects running in parallel. In this way, it is possible to reduce and optimize acquisition and transportation costs, as well as the organization of the construction, considering the space requirements of the required depot. The limit values can always be set individually in the algorithm according to the specifics of the current project.

It is important to note that quantitative calculations may be affected by outliers, so a professional review of the data may still be necessary.

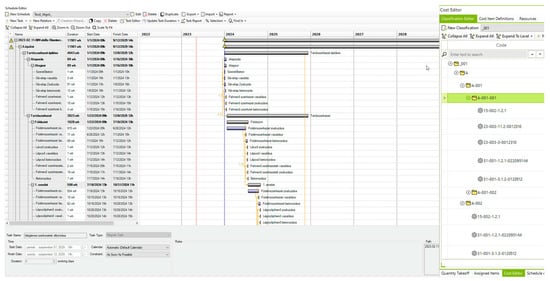

2.2.4. Planning the Scheduling of Safety Equipment—How the Supplementary Development Works

During the scheduling of structural and safety model elements, a collaborative environment between Autodesk Revit and BEXEL Manager had to be implemented. The building model can be easily transferred from Revit to BEXEL Manager using the BEXEL Add-on, but creating the schedule is a semi-automatic and professional task. In addition, the implementation required some custom development, as the Bexel Manager must handle and add the start and end dates for each element as parameters. For this reason, we developed a custom C# code. With this additional code, it became possible to capture the scheduling times of the model elements as property values and export them to a CSV file. The CSV file is built line by line. Each row contains the unique identifier (Revit ID) of a building element and its construction start and end date.

After that, the exported file can be imported into the model, including the safety elements in the Revit environment, using the algorithm. Then this data is added to the native model elements. Finally, it checks which safety objects are related to which building elements, and according to this link, it fills the safety objects with time information. It is possible to integrate time factor analysis into the algorithm along a complex logic. The aim was not to produce a simulation algorithm but to be able to estimate the required (to-be-used) quantity of safety equipment for a given time or time period.

2.2.5. Model and Data Updates

The process described so far has resulted in a model version and a planned delivery schedule, but circumstances change many times during the construction process. This could not be ignored in our research and development project, so we had to update the models. The goal was to reduce manual workflows and to create a methodology that automates the import of the updated models, the allocation of safety equipment, and the updating of quantitative calculations.

Obviously, if during the construction there are not only changes in the time schedule but also changes in the design of the building, then updating and modifying the Revit model is a manual modeling task. However, once updated, the logical relationships and predefined rule sets previously built in the BEXEL Manager software can handle new or changed model elements, as presented in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Schedule update using item classification-based filtering in BEXEL Manager.

The custom C# code then performs the extraction of the time factor, so that all the initial information is available. The algorithm can be run after opening the updated model and importing the exported CSV file. It will then update the previously associated construction dates of 3D elements, as well as review and update the assignment of safety elements. The outcome of the process is the production of updated quantitative reports and 2D-3D views based on changed construction conditions, which support effective change management (Figure 2 Phase “C”).

3. Results

The objective of this paper is to develop algorithms that can be employed to assist professionals in the field of construction safety and management, mainly regarding fall risks due to unguarded edges in construction projects. The main result of the research is a methodology supporting optimization-oriented safety planning in regards of FFH prevention. Due to the structure of the methodology, partial results are also created during the processes, such as danger zone detection, guardrail distribution, stock management, and quantity takeoffs. Thanks to the introduced procedure of combining algorithms, 3D-4D BIM model, and construction management processes, the proposed methodology is able to facilitate optimization-oriented safety planning.

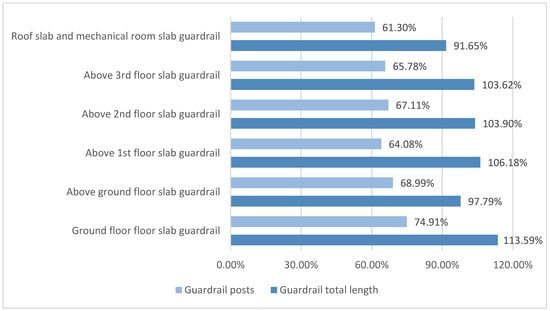

The algorithm-based calculations have been validated by making a traditional calculation. For this calculation, the DOKA Tipos 9 was used. Figure 14 presents the results of the comparison, where the values represent the difference between the traditional and the algorithm-based calculation. As presented, the values of length are quite similar; however, the number of posts is different. It may be because of the different logic applied. The algorithm considered the columns and all the “clashes” in the path during the construction, so this resulted in more guardrail posts in the end.

Figure 14.

Comparison of traditional (DOKA Tipos 9-based) and algorithm-based planning results.

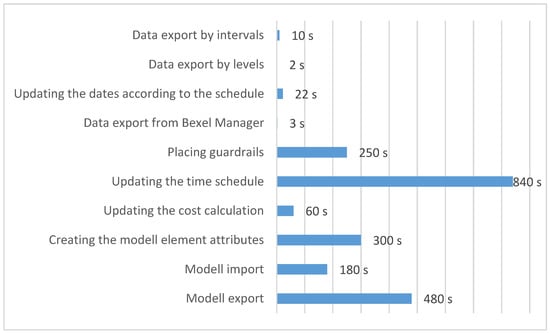

In the case of the traditional calculation, the planning time was much more than just running the algorithm, and in the case of design changes, the calculation time was cumulatively shorter using the algorithm. When the asset design or some model geometry must be changed, all the information contained in the dataset must be updated. In Figure 15, the tasks and their related time are presented to prove the previous statement that the algorithm-based workflow is more efficient. The tasks of the recalculation were measured in seconds. In summary, the updating process took only 35 min, which proves that the applied procedure is efficient.

Figure 15.

Time measuring results in the case of a 3D model update.

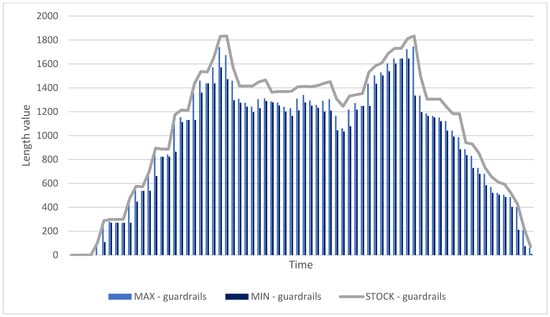

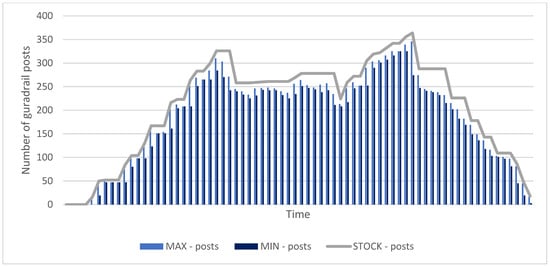

As a result, the algorithm-based calculation allowed us to take the time schedule into consideration. The used schedule was a fictional schedule to simulate the project with safety equipment. We examined five years with monthly sections, and during the calculation, the number and length of equipment needed and the stock on the construction site were calculated by the algorithms. Figure 16 and Figure 17 present the maximum, minimum, and stock values in the predefined period. According to the rules defined in the previous sections, the calculation was made for the stock values, too. The stock rules and time periods could be freely manipulated according to project-specific needs. The algorithm-based calculations made it possible to optimize the stock amount according to the time schedule.

Figure 16.

Required summarized length of elements calculated by the algorithm.

Figure 17.

Number of elements calculated by the algorithm.

Since the algorithm can detect all interior and exterior edges of the structural slab, it can accurately determine the area of the covered shafts, the length of the guarded sides, and the number of planks and posts that need to be placed. Aside from that, these quantity values form a database for safety guardrails in the project, and they are essential for safety planners and quantity surveyors to conduct the quantity takeoff for the guardrail sub-categories in the safety material take-off list.

The algorithm can place guardrails in the required positions, with predefined length modules. It can automatically divide the lengths of the sides (according to the predefined rulesets) that need to be guarded and finally provide the total number or length of the guardrails needed. The length modules that have been used are parametric values that can be modified, enhancing their operability and adaptability to different length modules, applying various manufacturers’ equipment.

The developed algorithm can optimize the lengths of the required guardrails at any time interval of the construction phase based on the date and guardrails’ quantity database, by smartly reading and checking the placed guardrails according to the chosen time interval and comparing them to the available ones in the quantity database. Then it can calculate the required length of the needed guardrail for each placing attempt.

4. Discussion

The presented time values were adequate for the current model size; these might increase in the case of larger models. The research revealed that the application of algorithms and BIM in construction safety aspects is limitless. The presented model and algorithms were developed in the Autodesk environment as a proof of concept, but the script could be adapted to work with other IFC (Industry Foundation Classes) models, which could be exported from different CAD tools. Hence, a future development can be a format conversion by adding an extra node in the script, which enables the software to read elements coming from the IFC model file and not only from the Revit environment, thus supporting OpenBIM environments. Moreover, despite guardrails and plate covers, future research may include more complicated and unusual FFH safety equipment, like net and fall-arrest systems.

Regarding optimization, and in connection with development possibilities, in construction management and scheduling, the assembling and dissembling dates for guardrails can be adjusted based on the dates. Also, the storage sizes on the construction site could be optimized, which can be beneficial. This may enhance the workability and efficiency of the whole safety system.

The research team also believes that the development of Health and Safety BIM models and related applications can support construction safety in the future [65].

5. Conclusions

Health and safety issues in the construction sector are major concerns; this paper generally discusses construction accidents, particularly Falls from Height (FFH), in the context of building projects. This research introduces a combined system that assists FFH safety planning and related quantity take-offs as a Prevention Through Design (PtD) method. The system employs developed algorithms that detect danger zones in the 3D BIM model and automatically distribute the required safety equipment to minimize FFH risk. Furthermore, the developed solution allows for the consideration of time as a parameter and applies the construction schedule in the planning and calculation procedure. The BIM model-based time schedule values are coordinated with the health and safety equipment (guardrails), and according to that relationship, we can calculate an optimized amount of safety elements. For that purpose, a 4D BIM model was developed with an additional data exporter script. The research in its current form is a proof of concept, developed in the Autodesk environment; further research opportunities can consist of script modifications, so that the methodology can support other software environments and OpenBIM concepts as well. The outcome is a BIM model of the entire project and the associated safety elements in 3D space, supporting accident prevention on-site and more accurate planning of safety equipment. The procedures developed enable us to deliver more accurate safety analyses and cost- and time-efficient solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.Z.; Methodology, M.B.Z., O.R. and P.M.M.; Software, V.N.R., N.B. and J.E.; Validation, P.M.M., J.E. and T.J.; Formal analysis, O.R., V.N.R. and J.E.; Data curation, V.N.R.; Writing—original draft, O.R.; Writing—review & editing, M.B.Z. and T.J.; Visualization, P.M.M., N.B. and T.J.; Supervision, O.R. and P.M.M.; Project administration, N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication was granted by the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary, within the framework of the ‘Internal Grant for Supporting Scientific Publications (3.0).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the authors due to intellectual property.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou, Z.; Goh, Y.M.; Li, Q. Overview and analysis of safety management studies in the construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.; Fargnoli, M.; Parise, G. Risk Profiling from the European Statistics on Accidents at Work (ESAW) Accidents′ Databases: A Case Study in Construction Sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Rafiq, M. An Overview of Construction Occupational Accidents in Hong Kong: A Recent Trend and Future Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosly, I. Safety Performance in the Construction Industry of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 4, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajslev, J.Z.N.; Nimb, I.E.E. Virtual design and construction for occupational safety and health purposes—A review on current gaps and directions for research and practice. Saf. Sci. 2022, 155, 105876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürcanli, G.E.; Müngen, U. Analysis of Construction Accidents in Turkey and Responsible Parties. Ind. Health 2013, 51, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Industrial Safety and Health Association. Industrial Accidents Statistics in Japan; Japan Industrial Safety and Health Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Construction Statistics in Great Britain, 2022. Great Britain, Annual Statistics, Data Up to March 2022, November 2022. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/constructionindustry/articles/constructionstatistics/2022 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- EUROSTAT. Accidents at Work-Statistics by Economic Activity—Statistics Explained; EUROSTAT: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS. Number and Rate of Fatal Work Injuries, by Private Industry Sector; U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Simutenda, P.; Zambwe, M.; Mutemwa, R. Types of occupational accidents and their predictors at construction sites in Lusaka city. Occup. Environ. Health, 2022; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fass, S.; Yousef, R.; Liginlal, D.; Vyas, P. Understanding causes of fall and struck-by incidents: What differentiates construction safety in the Arabian Gulf region? Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadiri, Z.O.; Nden, T.; Avre, G.K.; Oladipo, T.O.; Edom, A.; Samuel, P.O.; Ananso, G.N. Causes and Effects of Accidents on Construction Sites (A Case Study of Some Selected Construction Firms in Abuja F.C.T Nigeria). IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2014, 11, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-C.; Wang, L.-Y.; Ho, C.-K.; Yang, C.-Y. Fatal occupational injuries in Taiwan, 1994–2005. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, M.M.; Terouhid, S.A.; Kibert, C.J.; Hakim, H. Safety concerns related to modular/prefabricated building construction. Int. J. Inj. Contr. Saf. Promot. 2017, 24, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Hinze, J. Analysis of Construction Worker Fall Accidents. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2003, 129, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.-F.; Chang, T.-C.; Ting, H.-I. Accident patterns and prevention measures for fatal occupational falls in the construction industry. Appl. Ergon. 2005, 36, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junjia, Y.; Alias, A.H.; Haron, N.A.; Bakar, N.A. A Bibliometrics-Based Systematic Review of Safety Risk Assessment for IBS Hoisting Construction. Buildings 2023, 13, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS. Fatal and Nonfatal Falls, Slips, and Trips In the Construction Industry; U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Bakai, N.; Máder, P.M.; Horkai, A.; Etlinger, J.; Zagorácz, M.B.; Rák, O.; Bachmann, B. Determination of intervention areas to prevent and reduce work accidents in the construction industry-supported by statistical data analyses, (original: Az építőipari munkabalesetek megelőzésére és csökkentésére irányuló beavatkozási területek-statisztikai adatelemzéssel történő - meghatározása). Hung. Constr. Ind. Orig. Magy. Épip. 2021, 70, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Gu, B.; Chin, S.; Lee, J.-S. Machine learning predictive model based on national data for fatal accidents of construction workers. Autom. Constr. 2020, 110, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimichailidou, M.; Ma, Y. Using BIM in the safety risk management of modular construction. Saf. Sci. 2022, 154, 105852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaie, E.; Lingard, H.; Cooke, T. Causes of Fatal Accidents Involving Cranes in the Australian Construction Industry. Constr. Econ. Build. 2015, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Construction (Design and Management) Regulations (CDM). 2007. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2007/320/regulation/27/made (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Managing health and safety in construction. In Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015: Guidance on Regulations; HSE Books: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Fall Protection in Construction. U.S. 2015. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/OSHA3146.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Jokkaw, N.; Suteecharuwat, P.; Weerawetwat, P. Measurement of Construction Workers’ Feeling by Virtual Environment (VE) Technology for Guardrail Design in High-Rise Building Construction Projects. Eng. J. 2017, 21, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruffi, D.; Costella, M.F.; Pravia, Z.M.C. Experimental Analysis of Guardrail Structures for Occupational Safety in Construction. Open Constr. Build. Technol. J. 2021, 15, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Regulations (Part K Amendment) Regulations 2011. 2012. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/tris/en/index.cfm/search/?trisaction=search.detail&year=2011&num=308&dLang=EN (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Health and Safety Executive. Health and Safety in Construction; HSG150; Health and Safety Executive: Merseyside, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-7176-6182-2.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 1910.29—Fall Protection Systems and Falling Object Protection, Criteria and Practices; Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- The Hungarian Government. The Minimum Occupational Safety Requirements to be Implemented at Construction Sites and During Construction Processes; The Hungarian Government: Budapest, Hungary, 2002; Volume 4. Available online: https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=a0200004.scm (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Fudickar, S.; Lindemann, A.; Schnor, B. Threshold-Based Fall Detection on Smart Phones; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuspinar, A.; Hirdes, J.P.; Berg, K.; McArthur, C.; Morris, J.N. Development and validation of an algorithm to assess risk of first-time falling among home care clients. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.; Kim, T.H.; Yuhai, O.; Jeong, S.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Mun, J.H. Deep Learning-Based Near-Fall Detection Algorithm for Fall Risk Monitoring System Using a Single Inertial Measurement Unit. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 2385–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, J.; Dong, F.; Huang, Z.; Zhong, D. Fall Detection Algorithm Based on Inertial Sensor and Hierarchical Decision. Sensors 2022, 23, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Yang, S. Enhancing construction workers’ health and safety: Mechanisms for implementing Construction 4.0 technologies in construction organizations. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 68–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, M.; Alboga, Ö.; Aydınlı, S.; Erdis, E. Usability of large language models for building construction safety risk assessment. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhan, S.J.; Samsami, R. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Construction Safety: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Perera, W.L.; Kühnel, C.; Vollrath, C. Vision-based Warning System for Maintenance Personnel on Short-Term Roadwork Site. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.01689. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Koo, B.; Yang, S.; Kim, J.; Nam, Y.; Kim, Y. Fall-from-Height Detection Using Deep Learning Based on IMU Sensor Data for Accident Prevention at Construction Sites. Sensors 2022, 22, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Mojtahedi, M. A Safety Warning Algorithm Based on Axis Aligned Bounding Box Method to Prevent Onsite Accidents of Mobile Construction Machineries. Sensors 2021, 21, 7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navon, R.; Kolton, O. Algorithms for Automated Monitoring and Control of Fall Hazards. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2007, 21, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekitabar, H.; Ardeshir, A.; Sebt, M.H.; Stouffs, R. Construction safety risk drivers: A BIM approach. Saf. Sci. 2016, 82, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors. 2012, Volume 12. Available online: https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/AJCEB/article/view/2749 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Melzner, J.; Zhang, S.; Teizer, J.; Bargstädt, H.-J. A case study on automated safety compliance checking to assist fall protection design and planning in building information models. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, Z.; Arslan, M.; Kiani, A.K.; Azhar, S. CoSMoS: A BIM and wireless sensor based integrated solution for worker safety in confined spaces. Autom. Constr. 2014, 45, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Baptista, J.S.; Pinto, D. BIM Approach in Construction Safety—A Case Study on Preventing Falls from Height. Buildings 2022, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, H.R.; Hatem, W.A.; Jasim, N.A. Adopting BIM Technology in Fall Prevention Plans. Civ. Eng. J. 2019, 5, 2270–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, M.D.; Behnam, B.; Sebt, M.H.; Ardeshir, A.; Katooziani, A. BIM-Based Safety Leading Indicators Measurement Tool for Construction Sites. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 21, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Teizer, J.; Lee, J.-K.; Eastman, C.M.; Venugopal, M. Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Safety: Automatic Safety Checking of Construction Models and Schedules. Autom. Constr. 2013, 29, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, M.T.; Ershadi, M.; Carothers, L.; Jefferies, M.; Davis, P. A review and assessment of technologies for addressing the risk of falling from height on construction sites. Saf. Sci. 2022, 147, 105618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sulankivi, K.; Kiviniemi, M.; Romo, I.; Eastman, C.M.; Teizer, J. BIM-based fall hazard identification and prevention in construction safety planning. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.M.; Kim, B.C.; Kwon, T.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.J. A Study on Prevention of Construction Opening Fall Accidents Introducing Image Processing. J. KIBIM 2016, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Merchán, M.D.C.; Gómez-de-Gabriel, J.M.; Fernández-Madrigal, J.A.; López-Arquillos, A. Improving the prevention of fall from height on construction sites through the combination of technologies. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 28, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.; González García, M.d.l.N.; Poças Martins, J. BIM for Safety: Applying Real-Time Monitoring Technologies to Prevent Falls from Height in Construction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enhancing Individual Worker Risk Awareness: A Location-Based Safety Check System for Real-Time Hazard Warnings in Work-Zones. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/14/1/90 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Cheng, M.-Y.; Vu, Q.-T.; Teng, R.-K. Real-time risk assessment of multi-parameter induced fall accidents at construction sites. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-K.; Qin, C. Integration of BIM, Bayesian Belief Network, and Ant Colony Algorithm for Assessing Fall Risk and Route Planning. In Construction Research Congress 2018; American Society of Civil Engineers: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2018; pp. 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ali, A.K.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Lee, D.Y.; Park, C. Excavation Safety Modeling Approach Using BIM and VPL. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, I. BIM-Based Quality Control for Safety Issues in the Design and Construction Phases. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2015, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Ahmed, S. Developing an automated safety checking system using BIM: A case study in the Bangladeshi construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 1206–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.W.; Schultz, C.; Teizer, J. BIM-based Fall Hazard Ontology and Benchmark Model for Comparison of Automated Prevention through Design Approaches in Construction Safety. In Proceedings of the 29th EG-ICE International Workshop on Intelligent Computing in Engineering, Aarhus, Denmark, 6–8 July 2022; pp. 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Mansuri, L.E.; Patel, D.A.; Chauhan, S. Harnessing BIM with risk assessment for generating automated safety schedule and developing application for safety training. Saf. Sci. 2023, 164, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Rák, O.; Bakai, N. Az Építőipari Munkabalesetek Megelőzését Célzó, BIM Alapú Virtuális Valóság Felhasználási Lehetőségeinek Vizsgálata. Magy. Építőipar 2024, 73, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.