Abstract

Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) systems operating in the 860–960 MHz frequency range are widely used in applications such as supply chain management, retail, access control, healthcare, and transportation. This study presents the design, modeling, and fabrication of two antennas for this frequency range, followed by a comparative analysis to identify the antenna with superior gain. Key parameters, including corner fillets and chamfering, as well as antenna length, were varied to evaluate their impact on gain and S-parameters for the initial antenna considered the best from the two structures analyzed, aiming to optimize performance while minimizing size and keeping the frequency unchanged. Additionally, the antennas’ interaction with the human body was assessed through numerical modeling by evaluating the electric and magnetic fields and calculating the specific absorption rate for a human leg and hand in order to analyze the impact of these types of antennas on the human body. The dimensions of the initial structure were minimized while the antenna operated in the same frequency range, leading to a small decrease in the gain. It was discovered that when analyzing the values of the parameters of interest regarding the interaction with a human body, the RFID will not exceed them when considering the human hand, but it will harm a human foot when not placed at a specific distance from it.

1. Introduction

An antenna is a device that is used to transmit or receive electromagnetic waves, such as radio or television signals. Antennas can convert electrical signals into electromagnetic waves and vice versa. There are different types of antennas, each with specific applications, such as satellite dishes, patch antennas, or dipole antennas. The different types of antennas can be combined to form specific structures. As an example, when constructing a planar antenna, we can consider describing it as a dipole antenna with its characteristics, but instead of being a wire in air, it is a copper microstrip on a dielectric substrate. To reduce its dimensions, the “planar dipole” is folded [1,2,3]. This is how the antenna shapes for this article were created by creating microstrips, like dipoles, and then folding them for better integration in a small space.

When evaluating different types of antennas, their applications extend across a wide range of domains. Antennas can be employed for object and human detection, functioning as integral components in sensing systems. They may also serve as sensors for monitoring environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, and air quality [4,5] or for tracking human physiological signals and movements [6,7,8,9]. In addition, antennas are fundamental in wireless communication systems, enabling the transmission and reception of information with high efficiency. Another significant application lies in RFID technology, where antennas are used for identification, tracking, and data exchange in logistics, healthcare, and security systems.

RFID technology operates across multiple frequency bands, including 125 kHz and 13.56 MHz [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] for inductive systems, such as intercoms, payment cards, and (NFC), as well as 860–960 MHz, 2.4 GHz, and 5 GHz [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] for radiating systems applied in supply chain management, fleet tracking, and vehicle access control. The 860–960 MHz band is widely used, but its allocation varies by region: Europe (865–868 MHz, ETSI EN 302 208), USA (902–928 MHz, FCC Part 15), China (920–925 MHz), Japan (above 900 MHz), and India (865–867 MHz). These variations reflect the regulatory and operational differences that must be considered when designing RFID systems for global applications.

This article presents two different planar antennas functioning in the bandwidth of 860–960 MHz with their characteristics and advantages, and disadvantages.

In previous studies, the antennas used for such frequencies had bigger dimensions. In ref. [28], an omnidirectional antenna with a gain of approximately 1.5 dB is presented, but the dimensions are 96 × 16 mm, and the dielectric is a very thin polyester that is very hard to manufacture. This study was considered because the antenna has a design similar to the ones in this study. Article [29] has, as a subject, a smaller antenna with the dimensions of 78 × 30 mm, with a design similar to the second antenna considered for the study. In this case, the dielectric is also FR4, with the same thickness, but the gain is not considered for analysis. In ref. [8], the antenna has a higher area and a gain of 0.6 dB, being constructed on a Rogers material with the relative permittivity of 3.5. The fourth antenna considered [30] is constructed on a paper dielectric with a relative permittivity of 3.2, a thickness of 0.5 mm, and reached a gain of 3.4 dBi. In ref. [31], the gain of the antenna is lower, −4.85 dB, and it has 40 × 38 mm dimensions, and it is constructed on a FR4 epoxy dielectric. In ref. [32], the antenna is on a flexible polyethylene substrate with dimensions of 50 × 25 mm. The peak gain is 0.375 dB, and the dimensions increase with the integration of the grounding. The antenna in [33] has 200 × 200 mm—thus a very big antenna in comparison to the other ones—and a gain of −13.46 dB. Another high-dimension antenna considered for this frequency range is the one in [34], which is 46.1 × 126.7 mm and has a gain of 1.44 dB. The advantage of this structure is that it functions in two frequency ranges, one of which is also the one that we are studying. The other two antennas considered are the ones from [8,35], but they are both of large dimensions. In Table 1, some of the examples presented above can be seen.

Table 1.

Structures of RFID antennas operating in the frequency range of 860–960 MHz.

The aim of this work is to determine the type of antenna that operates in the frequency range 860–960 MHz with smaller dimensions while having a high gain, all while also considering its impact on the human body. In Section 2, two different antennas were modeled and practically made in order to determine their characteristic parameters. The antenna with the higher gain between them was considered in Section 3 to be modeled, and some modifications were made in order to see their influence on its gain and S-parameters. Section 4 presents an analysis of the interaction between two antennas in proximity to each other, while Section 5 determines the impact of the antenna on the human hand and leg. The paper concludes with Section 6. Although our antennas do not have high gain, the goal of having a smaller dimension antenna operating in this frequency range was achieved. The small dimensions led to better integration. Due to the fact that the studied antennas have a smaller gain, they could be used in specific applications like dense networks. Also, these types of antennas are more suitable for on-body applications.

2. Structure of the Antennas Considered to Be Used in RFID Applications

In this paper, two miniaturized planar microstrip antennas for UHF RFID tags are proposed, and the one with a higher gain was further studied, analyzed, and optimized.

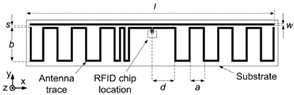

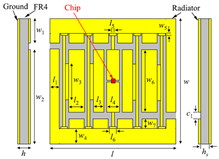

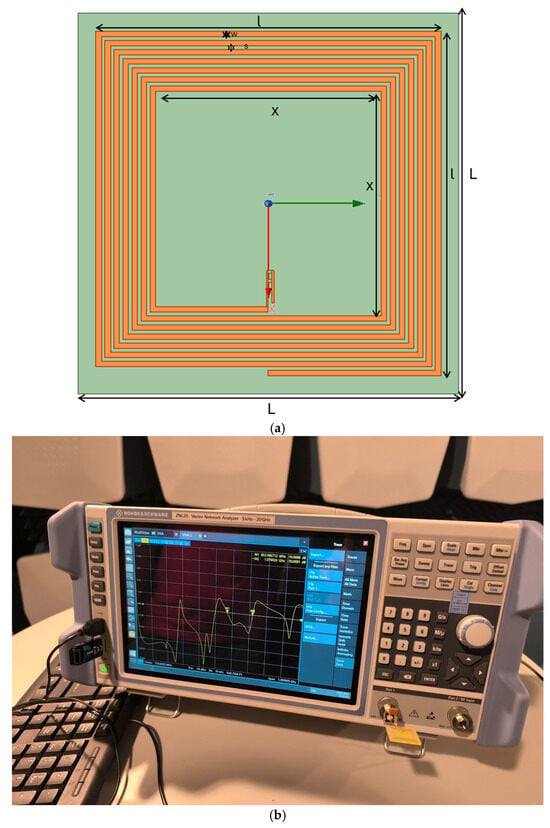

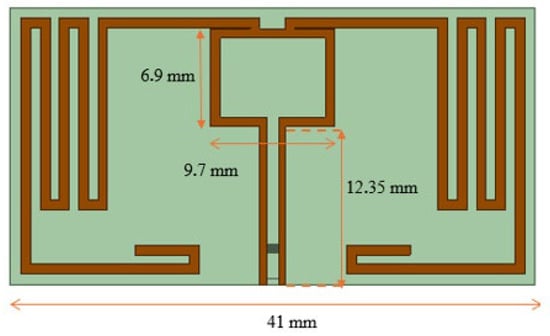

2.1. Structure with T-Match Configuration

The first structure considered has a simple design and was made in a modified T-match configuration, which was connected at both ends by a meandering line. The T-match ensures proper impedance matching and has a compact antenna design, but it is larger than other antennas operating in the same frequency range. To achieve a conjugate match between the tag chip and the proposed antenna, a π-shaped structure was applied. The folded dipole, which modifies the electrical length, was directly coupled to the π structure, resulting in a reduction in the physical size of the antenna, and consisted of a dipole with a width of 0.75 mm, bent into a serpentine shape. The material used as a conductor was copper. The radiating element of the tag was printed on a thin substrate, FR4, with a thickness of 1.5 mm and a total area of 48 × 2.63 × 1.51 mm3. This dielectric was chosen due to its versatility and also because it is accessible and has a low cost. The descriptive geometry of the antenna with its dimensions and geometrical shape is detailed in Figure 1. In Table 2, the dimensions of the structure can be seen.

Figure 1.

The descriptive configuration of the antenna considered for the study.

Table 2.

Dimensions of the RFID antenna.

The structure was initially modeled in the Ansys Q3D Extractor program, where an inductance value of 32.587 nH was obtained. The model was then imported into Ansys HFSS, and some circuit elements were added to its terminals (resistors and capacitors), such as the antenna, to resonate in the considered frequency range. The antenna was designed and modeled in Ansys HFSS, and its functioning was determined in the frequency range 5 kHz–1.5 GHz.

Considering that we want to have an antenna that will operate within the 860–960 MHz frequency band, and knowing the value of the equivalent inductance of the radiating element, the required capacitance for resonance according to (1) was determined to be 0.843 pF for an antenna operating at 960 MHz, and 1.05 pF for an antenna operating at 860 MHz.

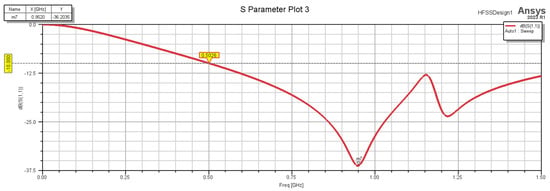

After multiple attempts with the value of the capacitor as close as possible to the one obtained by calculation, the plot in Figure 2 was obtained. Although the antenna resonates at 950 MHz, the plot proves that it functions on the entire considered bandwidth and more. The circuit elements added were a resistor of 50 Ω and a capacitor of 2 pF connected in series. The resistor and capacitor were then connected in parallel to the antenna.

Figure 2.

S-parameters of the modeled structure.

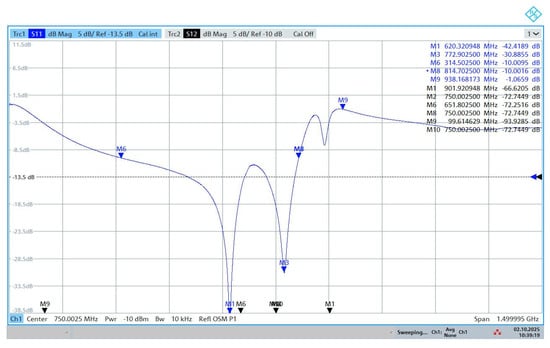

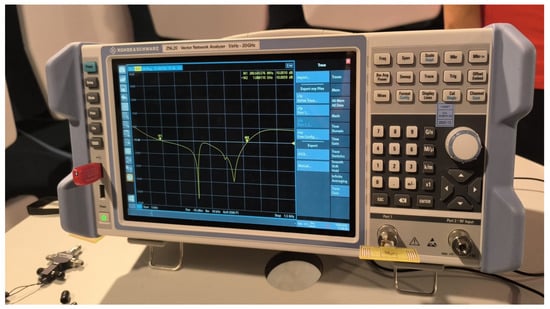

In practice, such low capacitance values are difficult to implement when using standard discrete capacitors. Therefore, a practical approximation was attempted by connecting two capacitors of 2.2 pF in series, resulting in an equivalent capacitance of approximately 1.1 pF, which is close to the theoretical value. This capacitor network was connected in parallel with a 50 Ω resistor in order to emulate the measurement and matching conditions. However, as shown in Figure 3, the experimental results did not fully match the expected theoretical predictions. The discrepancies can be attributed to component tolerances, parasitic effects (such as pad capacitance and equivalent series inductance), and the damping introduced by the parallel resistance, which significantly affects the quality factor and the resonance depth. To improve the tuning accuracy, further optimization is required, either by employing high-Q capacitors with smaller nominal values, trimmer capacitors for fine adjustment, or by designing an appropriate impedance matching network based on the measured input impedance of the antenna. Also, connecting three 4.7 pF capacitors connected in series and then in parallel with the resistor of 50 Ω was considered, and the results are better, as can be seen in Figure 4. The values for the capacitors were considered from the ones present on the market, with small values like 2.2 pF, 3.3 pF, and 4.7 pF. The equivalent capacitance of three such capacitors in series is 0.9 pF, 1.1 pF, and 1.56 pF. Connecting three 4.7 pF capacitors in series led to better performances in practice due to the fact that when talking about the physical structure, we must also consider the parasitic effects from the structure, the capacitor tolerances, and the losses.

Figure 3.

S-parameters of the modeled structure with two 2.2 pF connected in series and placed in parallel with the antenna terminals.

Figure 4.

S-parameters of the modeled structure with three 4.7 pF connected in series and placed in parallel with the antenna terminals.

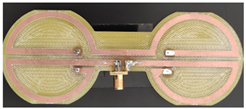

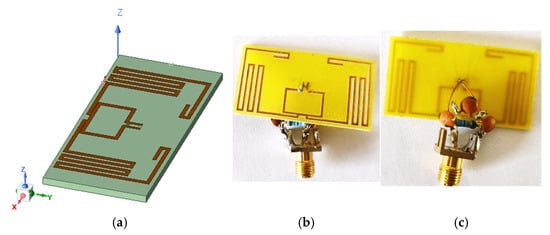

In Figure 5, the antenna constructed with the resistor and the capacitors connected can be seen. The initial prototype was also constructed on a 1.51 mm thick FR4 Epoxy dielectric substrate, copper-plated on only one side. This design, as stated before, allows for a longer electrical length without increasing the physical size of the antenna. This is a solution frequently used in RFID tags, especially where available space is limited. The analyzed structure helps to reduce the size, adapt to different frequencies, achieve good performance in various environments, and have low production costs.

Figure 5.

RFID antenna analyzed: (a) modeled antenna; (b) practical antenna front view; (c) practical antenna back view.

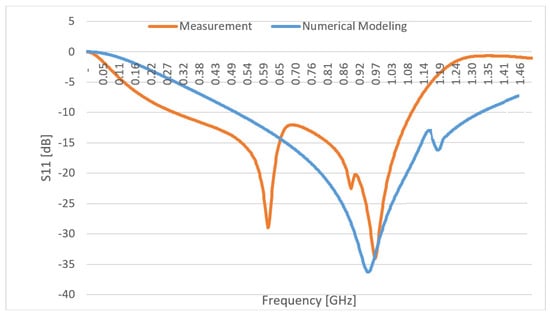

For a better understanding of the differences between the practical and modeled antenna S-parameters, the graph in Figure 6 can be observed. The comparison between numerical modeling and measurement reveals noticeable discrepancies in the S11 response of the proposed antenna. These deviations are primarily attributed to practical implementation factors that are not fully captured in the idealized simulation model. The tuning network employs capacitors with values below 2 pF, which are highly sensitive to manufacturing tolerances, which can also be a cause. Even small deviations lead to significant frequency shifts at UHF. In addition, parasitics, such as equivalent series inductance (ESL) and resistance (ESR) of the capacitors, as well as stray capacitances that are introduced by PCB pads, solder joints, and interconnecting wires, contribute to the mismatch.

Figure 6.

Comparison between the measurements and numerical modeling results.

The gain of an antenna is also a very important parameter when considering RFID because it is directly connected to the distance and orientation of the two antennas that must communicate. Thus, the representation of the gain for the considered antenna is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Gain for the structure considered.

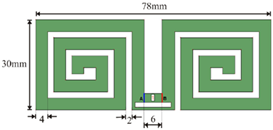

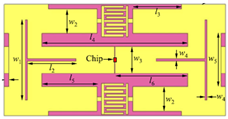

2.2. Spiraled Structures

Because of their versatility and the small space that they occupy, as well as the spiraled structures presented in [36], which function at the frequency of 13.56 MHz, these were considered for this study. The spiral structure allows miniaturization and broadens the effective bandwidth, and this is why they are a good choice for this study. For this, with the help of the well-known formulas, the capacitances needed in order to reach resonance in the frequency bandwidth between 860 and 960 MHz were determined for the four considered shapes of the spiraled structures. The capacitance was determined with Formula (1), while the inductance was determined with Formula (2) for the square shape, Formula (3) for the hexagonal shape, Formula (4) for the octagonal shape, and Formula (5) for the circle shape. In the structures considered, L is the inductance, µ is the permeability of the free space, N is the number of turns, and dm represents the average diameter of the inductor; ρ is the fill factor. The inner diameter of the inductor, dm, is calculated with Formula (6), where De is the exterior diameter of the inductor, and Di is the interior diameter of the inductor. Formula (7) determines the value of the fill factor, and w represents the width of the turn, while s is the distance between the turns [37,38].

dm = (De + Di)/2

ρ = [N·w + (N − 1)·s]/dm

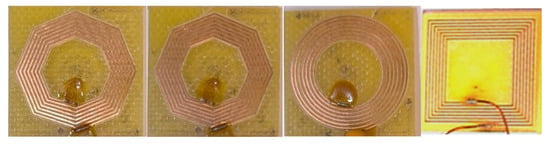

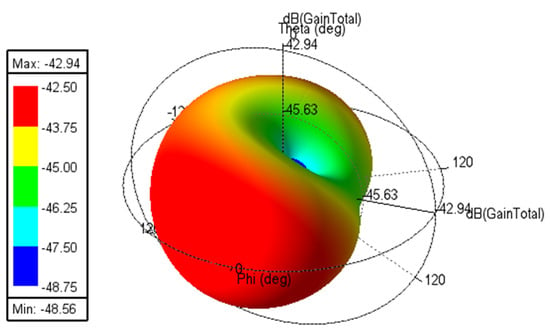

The values of the capacitance necessary were calculated for the four structures considered with Formula (1). The structures were considered to have an exterior diameter between 17 and 20 mm. It can be observed that the capacitance necessary for the inductors to resonate in the bandwidth considered is very low, and it is very difficult to obtain it in practice (Table 3). In this table, De represents the exterior diameter of the structure and is measured in mm, N represents the number of turns, w represents the width of one turn in mm, and s represents the spacing between two consecutive turns. The four columns, C circular, C square, C hexagonal, and C octagonal, represent the capacitances obtained for the four shapes of spiral antennas considered in pF. This is why, in this case, the coils were considered to be tested with only a 50 Ω resistance in parallel with the planar structure. There are some variations considering the tested structures and the results from the numerical modeling, but it is understandable. However, analyzing the results, one can tell that in both cases the structure functions in more than one bandwidth, and the considered bandwidth is one of them. The spiral inductors analyzed can be seen in Figure 8, and they are the same as the ones in [31]. The rectangular structure constructed through numerical modeling is presented in Figure 9a. The experimental results obtained for the rectangular antenna are presented in Figure 9b, while the corresponding results derived from numerical modeling are shown in Figure 9c. Figure 9d presents the results for a comparison and the RMSE error.

Table 3.

Capacitances for the spiral inductors with different shapes.

Figure 8.

Structures considered for analysis.

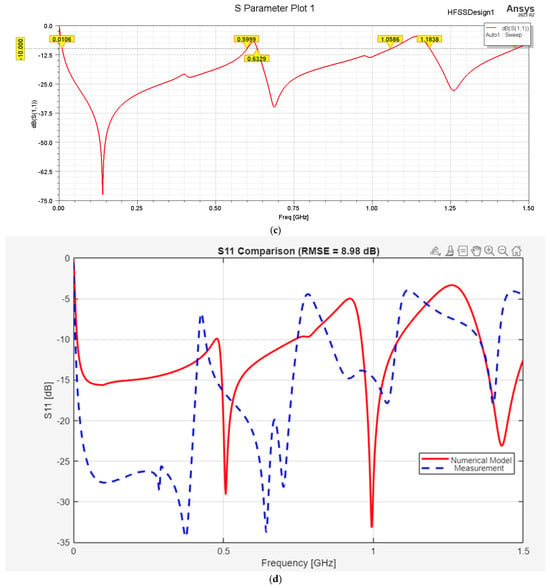

Figure 9.

Rectangular structure: (a) structure created through numerical modeling; (b) experimental results; (c) numerical modeling results; (d) comparison between the numerical and experimental results.

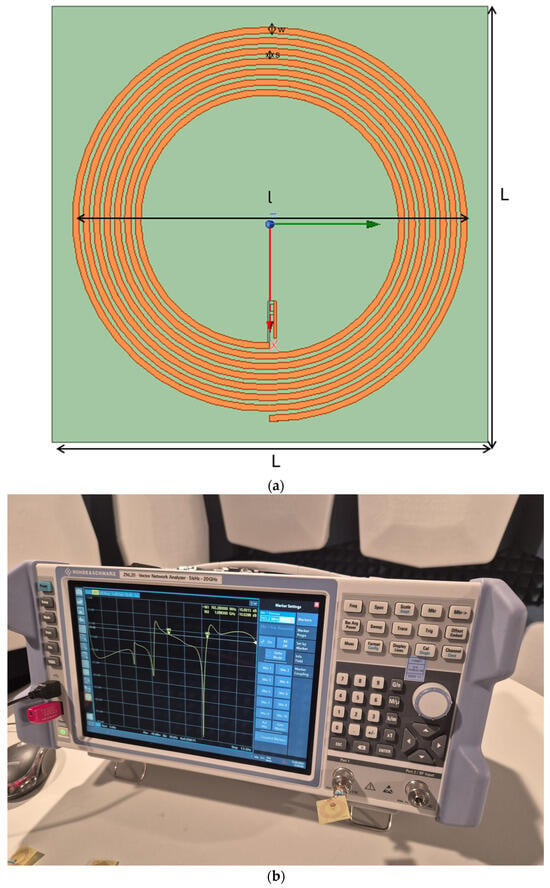

The results for the circular spiral inductors obtained through measurement and numerical modeling, and their comparison, are presented in Figure 10. The results for the other two types are not as good as the ones obtained for the square and circular shape inductors; thus, they are not presented here.

Figure 10.

Circular structure: (a) structure created through numerical modeling; (b) experimental results; (c) numerical modeling results; (d) comparison between the numerical and experimental results.

The dimensions of the two spiraled structures can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Dimensions of the spiraled RFID antenna.

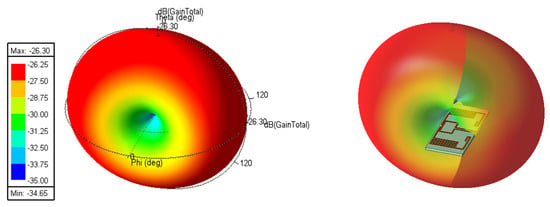

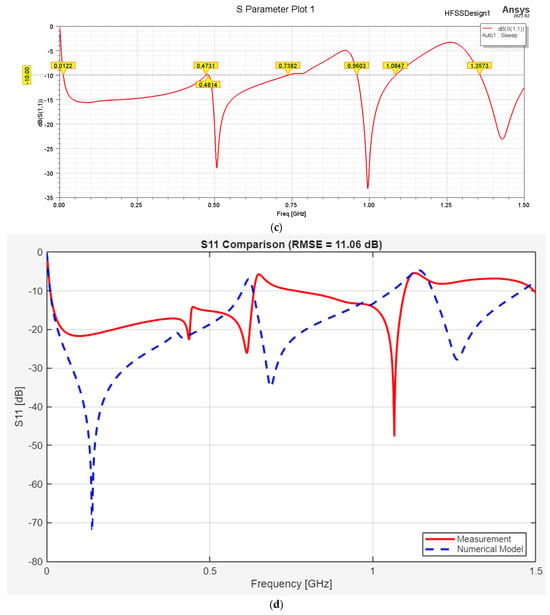

The gain of the structures was also determined (Figure 11). After considering the way in which the antenna from Figure 5 is emitted, it can be stated that the peak gain is lower and the orientation differs.

Figure 11.

The gain of the square spiral planar inductor shape.

Comparing the gain for the two antennas analyzed, the radiation pattern for the first antenna exhibits a more omnidirectional shape with a broader main lobe. The gain gradually decreases from the center outward, indicating a relatively uniform radiation in multiple directions. The maximum gain is approximately −26.30 dB, which suggests moderate radiation efficiency and wide angular coverage. For the second antenna, as seen in Figure 11, the pattern forms a toroidal (donut-like) shape, asymmetric in one direction, typical of dipole-like antennas. Most of the radiation is concentrated in the plane perpendicular to the antenna axis, with minimal radiation along the axis. The maximum gain is around −42.94 dB, which is significantly lower than the first antenna, implying lower efficiency or a higher loss. However, it offers better directional control and reduced back radiation. As a conclusion, the first antenna provides higher gain and broader coverage, which is suitable for general RFID field coverage, whereas the second antenna demonstrates dipole-like characteristics with a lower gain but more controlled directionality, which is potentially useful where confined field regions are desired.

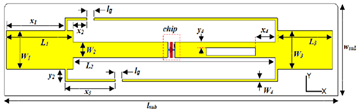

3. Influence of Different Construction Parameters on the Antenna’s Characteristic Parameters

For the next tests, the length of the wires where the feeding is connected was considered so as to reach the edge of the dielectric in an attempt to consider what happens in practice; however, the conclusions will remain the same.

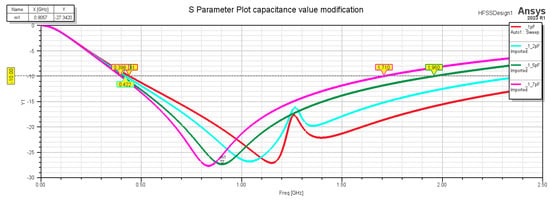

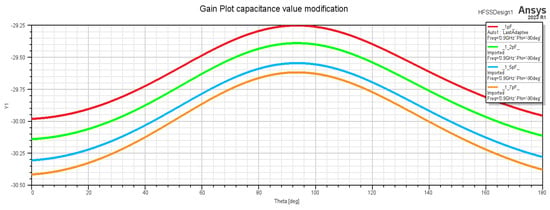

The graph from Figure 12 illustrates the influence of the capacitance value on the S11 parameter. As the capacitance increases (from 1 pF to 1.7 pF), the resonance frequency decreases, and the depth of the S11 minimum changes. The curves in Figure 13 illustrate the antenna gain as a function of capacitance variation. It can be observed that as the capacitance value increases, the gain decreases slightly but consistently. The value of 1 pF provides the highest gain, indicating better radiation efficiency in this configuration.

Figure 12.

The S-parameters vary with frequency for different capacitance values.

Figure 13.

The gain varies with the angle for different capacitance values.

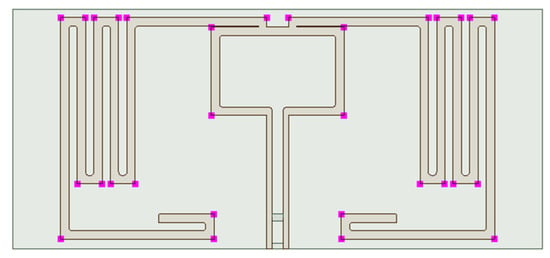

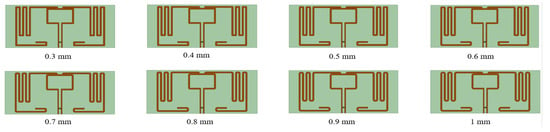

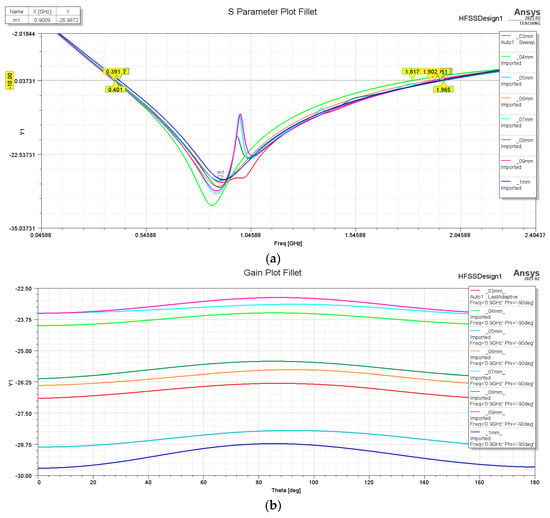

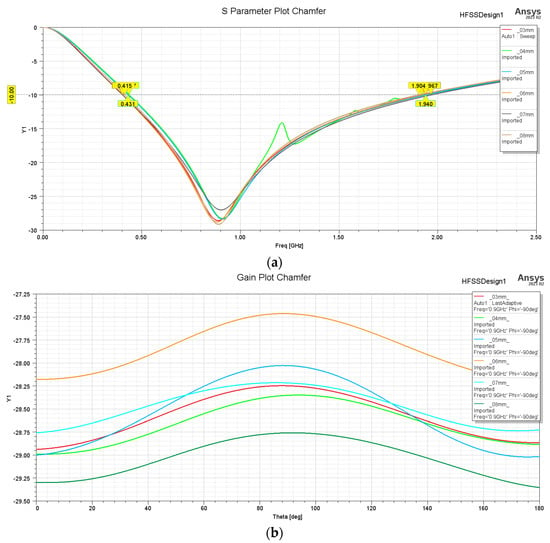

To optimize the previously designed high-frequency antenna, the geometry of the model was adjusted by applying rounding and chamfering to the edge corners (Figure 14), with fillet radius values ranging from 0.3 to 1 mm. The structures with rounded corners are presented in Figure 15. Analyzing the S-parameters (Figure 16a), it is concluded that the size of the fillet radius applied to the outer corners directly influences the antenna’s matching performance. The gain (Figure 16b) varies noticeably with the fillet radius, with values increasing as the radius grows. The highest gain is obtained for the 0.9 mm radius.

Figure 14.

The exterior corners selection.

Figure 15.

Structures with rounded corners.

Figure 16.

Parameters in the case of the rounded corners: (a) S-parameters; (b) gain.

The 0.5 mm radius remains optimal in this configuration, providing the best impedance matching and minimal reflection losses (Table 5).

Table 5.

The influence of the rounding radius on the parameters of interest.

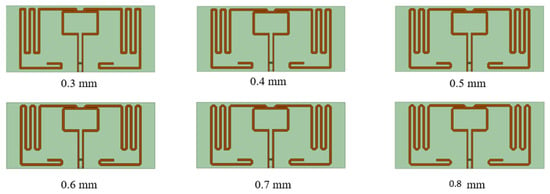

In the case of chamfering the outer corners (Figure 17), this has a smaller impact on the matching performance compared to rounding. However, the 0.6 mm value remains optimal, providing the best reflection characteristics (Figure 18). The values of the resonance frequency and the S11 value for that resonance, together with the peak gain value for that resonance, are presented in Table 6.

Figure 17.

Structures with chamfered corners.

Figure 18.

The S-parameters and gain variations for different corner chamfering: (a) S-parameters; (b) gain.

Table 6.

The influence of the chamfering radius on the parameters of interest.

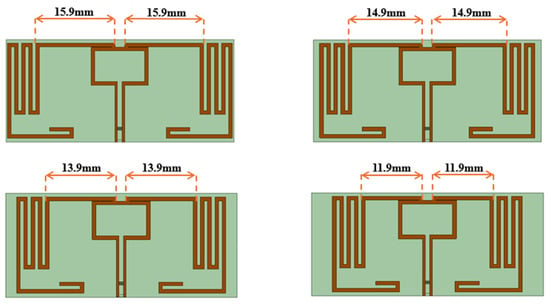

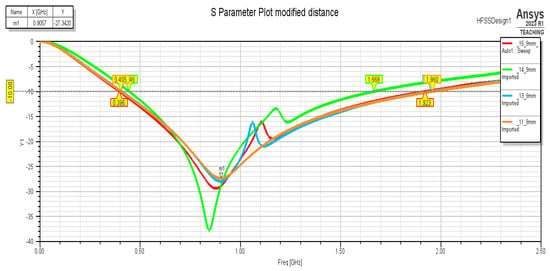

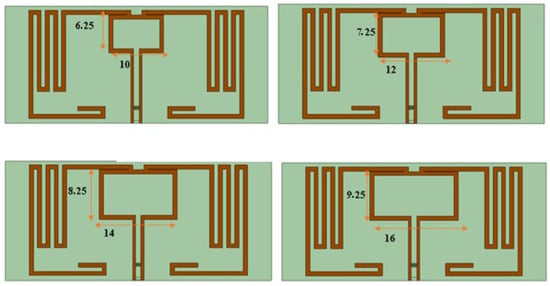

Four structures were modeled to determine the influence of the distance between the central square and the meandered segments, and they can be seen in Figure 19. The graph from Figure 20 shows the influence of the distance between the central square and the meandered segments on the antenna matching. As the distance decreases (from 15.9 mm to 11.9 mm), the resonance frequency changes slightly. The best matching is obtained for the 11.9 mm distance (orange curve), which exhibits a clear minimum around 0.9 GHz and is also the only smooth curve, without disturbances or multiple resonances. This indicates stable and optimal operation for this configuration.

The gain decreases as the distance reduces (Figure 21). Although the 11.9 mm configuration provides good matching (S11), it also exhibits the lowest gain, highlighting the need for a balance between matching and radiation performance (Table 7).

Table 7.

The influence of the spacing variation between the centered square and the meandered segments on the parameters of interest.

Figure 19.

The variation in the distance between the central square and the meandered segments.

Figure 20.

Representation of the S-parameters for the distance variation between the centered square and the meandered segments.

Figure 21.

Representation of the antenna gain for the distance variation between the centered square and the meandered segments.

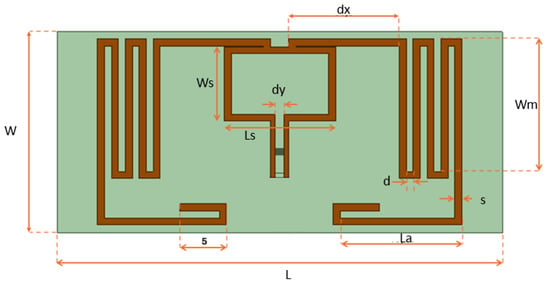

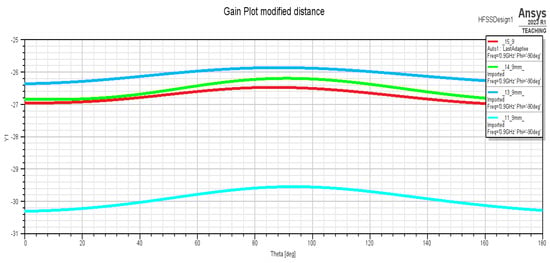

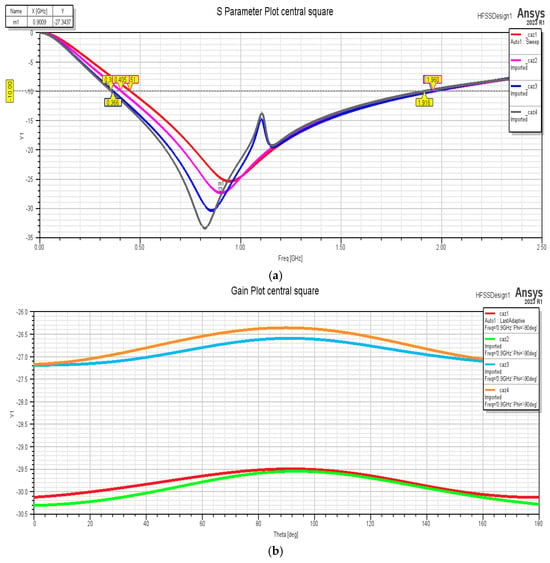

Four cases were selected for analysis, in which the dimensions of the central square of the radiating element were modified in order to determine how this parameter influences the antenna’s performance (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Structures with the variation in the radiant element dimensions.

It can be observed that as the dimensions of the central square of the radiating element increase, the resonance frequency decreases, confirming the direct influence of geometry on the antenna’s behavior (Figure 23a). Additionally, increasing the size of the central square leads to a higher antenna gain (Figure 23b).

Figure 23.

Variation in the S-parameter and gain based on the central square dimensions: (a) S-parameters; (b) gain.

If we consider all the geometrical modifications from this study, we must conclude that the modifications of the distance between the central square and the meandered segments, and also the modification of the central square, are the most significant. It can be clearly seen that the structure operates in approximately the same bandwidth, but its dimension is minimized. A fine modification of the resonant frequency value can also be obtained from these variations.

Following the analysis and the application of the proposed optimization methods—through the adjustment of geometric dimensions and reactive components—an optimized antenna prototype was developed, integrating the most efficient configurations identified during the study. This prototype reflects the improvements in antenna performance and represents a synthesis of the previously tested variants. The model retains most of the dimensions of the prototype shown in Figure 24. The optimized prototype is more efficient due to its reduced size, which results in lower material consumption and, consequently, reduced manufacturing costs. Compact design maintains the antenna’s performance while optimizing space utilization, a crucial aspect for RFID applications, where miniaturization is a major advantage. The bandwidth is mostly kept, while the maximum gain decreases a little, but keeps its orientation and shape. We also consider, for future work, applications of RFID using meta-surfaces as a way to further decrease their dimensions [39].

Figure 24.

The optimized prototype.

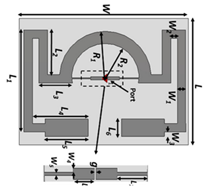

4. Analysis of the Interaction Between Two Antennas in Proximity to Each Other

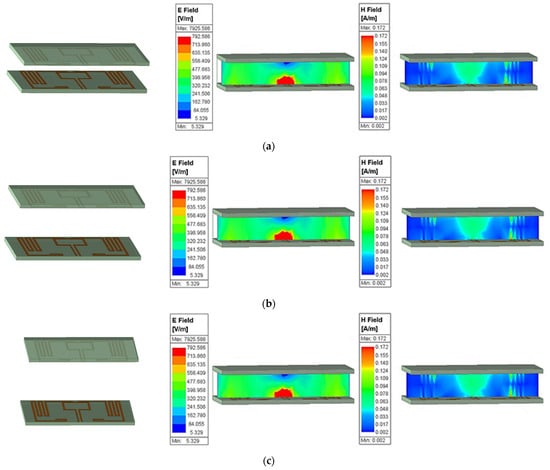

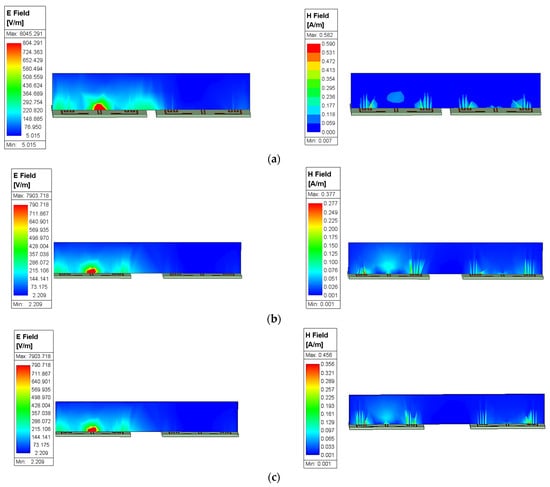

The first step was to determine the electric and magnetic fields generated between two antennas placed facing each other. The face-to-face arrangement of two identical antennas allows for the analysis of direct interactions between the fields they generate. In this configuration, the antennas are positioned so that their main radiation planes are oriented toward each other, simulating a direct communication or coupling scenario. Analyzing the distribution of the electric and magnetic fields in this setup is essential for understanding how physical proximity affects transmission performance, bandwidth matching, and potential losses due to unwanted coupling. This type of evaluation is useful in RFID, IoT, or other systems where antennas operate in close proximity. To observe the effects of a face-to-face antenna arrangement, we proposed four cases in which the distance between the antennas varied between 10 and 40 mm.

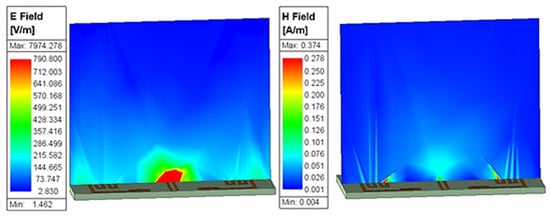

Initially, the distribution of the electric and magnetic fields generated by a single antenna was analyzed to establish a reference point before introducing the second antenna (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

The distribution of the electric and magnetic fields of a single antenna.

In the case of a single antenna, the electric field was concentrated near the conductor, reaching a maximum of 7974.278 V/m, while the magnetic field reached 0.374 A/m, being localized around the feed lines, indicating that the antenna radiates efficiently without external influences.

In the first case, where the antennas are placed at a minimum distance of 10 mm, the electric and magnetic fields are highly concentrated in space between them, indicating very strong electromagnetic coupling. Such intense interaction can negatively affect antenna performance by causing interference or altering radiation characteristics, which is critical in RFID systems where stable signal transmission is required. When the antennas are separated by 20 mm, the electric and magnetic fields remain concentrated between the structures, but with a slightly reduced intensity compared to the first case. This suggests moderate electromagnetic coupling, with decreased interaction and a lower risk of mutual interference, improving operational reliability. For the third case, where the antennas are 30 mm apart, the electric field intensity decreases while the magnetic field shows a slight increase. As spacing reduces capacitive coupling, less energy is stored in the electric field, leading to a corresponding slight increase in the magnetic field due to inductive coupling between current paths. This indicates weaker coupling and more dispersed electromagnetic interaction, which reduces interference effects and supports more stable RFID communication. In the fourth case, with a 40 mm separation, the fields are more evenly distributed: the electric field reaches a maximum of 8001.101 V/m at a lower position, and the magnetic field, although slightly higher at 0.280 A/m, is more diffusely spread. This demonstrates a significantly weaker interaction between antennas, which is beneficial for independent operation and minimal crosstalk (Figure 26). Figure 26e, which is also a vectorial representation for the 30 mm distance, is also presented for a better understanding of the phenomena presented between the antennas.

Figure 26.

The influence of the space between antennas on the electric and magnetic field between them: (a) 10 mm between antennas; (b) 20 mm between antennas; (c) 30 mm between antennas; (d) 40 mm between antennas; (e) 30 mm between the antenna vectorial representation.

As the distance between antennas increases, electromagnetic coupling decreases markedly. The fields become more uniform and less perturbed, resulting in more stable operation and improved performance for each antenna. By comparison, a single isolated antenna exhibits a clearly defined and symmetrical distribution of both electric and magnetic fields, representing the optimal reference for undisturbed operation.

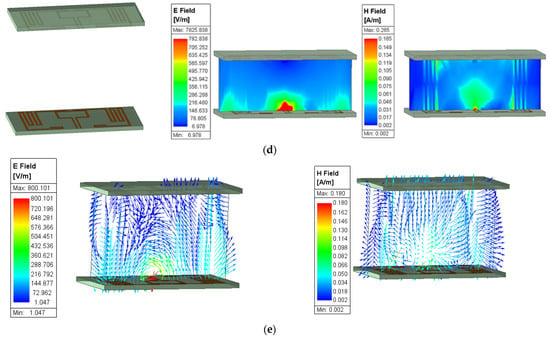

The proximity of identical antennas significantly alters the field distribution, potentially affecting the overall performance in RFID systems. For applications where signal stability and independent operation are critical, maintaining sufficient spacing between antennas is recommended to minimize coupling and reduce interference, ensuring reliable communication and optimal system efficiency. To investigate the effects of a parallel antenna arrangement, we proposed three cases in which the distance between the antennas varied between 5 mm and 30 mm (Figure 27).

Figure 27.

The influence of the space between antennas on the electric and magnetic fields between them, parallel antenna arrangement: (a) 5 mm between antennas; (b) 20 mm between antennas; (c) 30 mm between antennas.

In the first case, with antennas placed 5 mm apart, a slight electric interaction was observed (as shown in the first figure). The antennas operate largely independently, with only a small region of coupling, likely due to their geometry and relative orientation. In the second case, with a 20 mm separation, the electric fields were completely isolated. No inductive coupling was present, and there was no indication that the antennas affected each other. The operation was fully independent.

When we have a 30 mm separation, there is no interaction resulting in fully independent operation. This configuration provides optimal conditions for applications where antennas must operate in parallel without mutual interference.

Overall, as the distance between parallel antennas increases from 5 mm to 30 mm, electromagnetic interaction decreases progressively until the antennas become completely independent both electrically and magnetically.

5. The Effects of Antennas Located near the Human Body

The increasingly widespread use of RFID technology in close proximity to the human body requires careful evaluation of the effects of electromagnetic fields generated by antennas on human health [30,40,41]. This chapter analyzes exposure levels in the context of international standards (ICNIRP, IEEE, ETSI) [42,43,44] and presents detailed simulations of the interaction between an RFID antenna and different parts of the human body, such as the arm and leg. The objective is to identify any exceedances of permissible limits and to determine the conditions under which antennas can be safely used in practical applications.

In the use of RFID antennas, evaluating the effects of electromagnetic fields on the human body is essential, especially in applications involving direct proximity between the user and the device. To ensure safe operation, several international organizations have established clear limits for electric field (E), magnetic field (H), and specific absorption rate (SAR) exposure. Among the most relevant standards are those issued by ICNIRP (International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection), IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), and ETSI (European Telecommunications Standards Institute).

ICNIRP provides guidelines for protection against non-ionizing radiation, recommending exposure limits for electromagnetic fields based on frequency and exposure duration. For frequencies around 900 MHz—typical of RFID systems—ICNIRP recommends the following maximum values for the general public: E: 41 V/m; H: 0.11 A/m; local SAR (head, torso): 2 W/kg (averaged over 10 g of tissue); whole-body SAR: 0.08 W/kg.

IEEE standard 95.1 provides similar standards, sometimes stricter for occupational applications. For electromagnetic fields between 300 MHz and 6 GHz, the IEEE limits for the general public are as follows: E-field (RMS-root mean square): 61 V/m; H-field (RMS): 0.16 A/m; local SAR: 1.6 W/kg (averaged over 1 g of tissue), commonly used in the USA.

ETSI, particularly in standards for radio equipment (e.g., EN 50364), adopts the ICNIRP limits and defines technical requirements for device compliance. For example, UHF RFID devices must comply with SAR thresholds and undergo testing in representative use configurations, such as in close proximity to the body.

Compliance with these limits is critical for avoiding excessive tissue heating or other undesirable biological effects, especially under repeated or prolonged exposure. In this study, these exposure limits were used as reference points in the interpretation of simulation results to determine whether the designed RFID antenna operates safely near the human body.

In order to evaluate the influence of the RFID antenna on the human body, a series of numerical simulations was carried out in Ansys HFSS, focusing on two representative body parts: the foot and the arm. In each case, four scenarios were analyzed, in which the limbs were positioned at varying distances from the antenna in order to observe how proximity influences the propagation of electromagnetic fields. The analysis focused on the electric field, magnetic field, and the specific absorption rate, a key parameter for assessing exposure safety. This stage aims to compare the obtained values with the limits established by international standards to determine whether the antenna can operate safely in the vicinity of the human body.

The models of the human hand of a female are predefined in the Ansys HFSS version used. From the special library, the user can choose human legs, arms, head, or even the body. The models are usually Voxel-based anatomical phantoms and are created as layers of different tissues like skin, fat, muscle, bone, and blood. Also, their characteristic relative permittivity is considered to vary with the frequency, and, as an example, the relative permittivity for different types of tissues at 890 MHz is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Properties of tissues of the human body for 890 MHz.

5.1. Study Regarding the Influence on the Left Arm of a Female

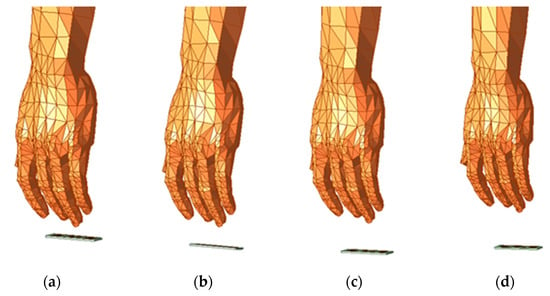

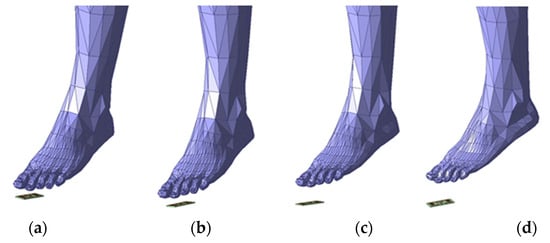

To investigate how the electromagnetic fields interact with the arm, four simulation cases were performed in which the arm model was placed at different distances from the antenna, from 10 mm to 40 mm, with a step of 10 mm. The models can be seen in Figure 28.

Figure 28.

The configurations considered for the analysis with the arm situated at: (a) 10 mm; (b) 20 mm; (c) 30 mm; (d) 40 mm.

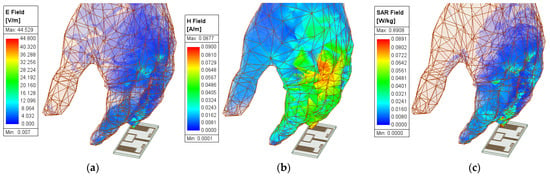

The simulation results indicate that as the distance between the arm and the RFID antenna increases, the values of the electric field, magnetic field, and SAR decrease significantly. In all four analyzed cases, including the closest configuration, the obtained values remain below the limits established by ICNIRP standards, indicating a safe level of exposure. Therefore, it can be concluded that the antenna can be safely used in body-proximate applications, particularly when a minimum separation distance of a few millimeters is maintained. For observation, the values obtained for a distance of 10 mm (Figure 29) and 40 mm (Figure 30) are presented. For the first case, the obtained values for the electric field (44.5 V/m), magnetic field (0.0817 A/m), and SAR (0.890 W/kg) are all below the limits established by the ICNIRP guidelines, indicating that the structure complies with safety regulations for frequencies below 2 GHz.

Figure 29.

The parameters of interest for a distance of 10 mm between the antenna and hand: (a) electric field intensity; (b) magnetic field intensity; (c) SAR.

Figure 30.

The parameters of interest for a distance of 40 mm between the antenna and hand: (a) electric field intensity; (b) magnetic field intensity; (c) SAR.

The measured values for the second case considered are 15.5 V/m for the electric field, 0.0563 A/m for the magnetic field, and 0.119 W/kg for the SAR, and indicate minimal electromagnetic influence, with levels being well below the limits permitted by ICNIRP standards.

The fields are more concentrated in the center of the hand because the center of the antenna, which radiates the most, is in its proximity. The maximum value of the considered parameters depends on the positioning of the antenna in relation to the hand and also on the distance between them.

5.2. Study Regarding the Influence on the Left Leg of a Female

To examine how the electromagnetic fields interact with the foot, four simulation cases were performed in which the foot model was positioned at the same distance from the antenna as the arm in the previous case. The models considered are presented in Figure 31.

Figure 31.

The configurations considered for the analysis with the leg situated at: (a) 10 mm; (b) 20 mm; (c) 30 mm; (d) 40 mm.

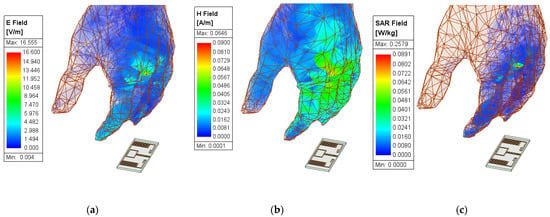

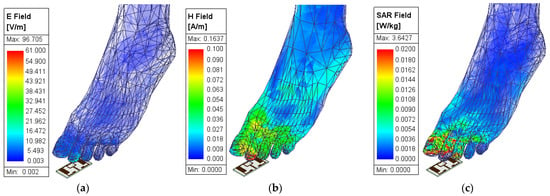

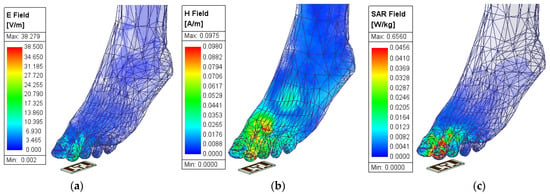

Based on the simulations performed for four different distances between the left foot and the RFID antenna, a clear decrease was observed in the values of the electric field, magnetic field, and specific absorption rate as the distance from the source increased. In the first case, when the foot was positioned very close to the antenna, the E-field and SAR values significantly exceeded the ICNIRP limits, indicating a potential risk under prolonged exposure conditions (Figure 32). Conversely, in the other considered cases, all recorded values were below the thresholds established by international standards, demonstrating that appropriate distancing substantially reduces the level of exposure. For exemplification, the case where the distance is considered to be 20 mm is presented in Figure 33.

Figure 32.

The parameters of interest for a distance of 10 mm between the antenna and leg: (a) electric field intensity; (b) magnetic field intensity; (c) SAR.

Figure 33.

The parameters of interest for a distance of 20 mm between the antenna and leg: (a) electric field intensity; (b) magnetic field intensity; (c) SAR.

In the first case, where the distance was 10 mm, the obtained values of 96.7 V/m for the electric field (exceeding the 61 V/m limit), 0.1657 A/m for the magnetic field (close to the 0.16 A/m limit), and a SAR of 3.64 W/kg (well above the 2 W/kg limit imposed by ICNIRP for 10 g of tissue) indicate a significant exceedance of safety parameters. This highlights a potential exposure hazard, emphasizing the need to avoid placing the antenna at distances shorter than 10 mm from the human body.

For the second case, the electric field value is 39.27 V/m (below the ICNIRP limit of 61 V/m), the magnetic field is 0.095 A/m (well below the 0.16 A/m threshold), and the recorded SAR is 0.65 W/kg (within the safe limit of 2 W/kg), indicating moderate exposure that is considered safe according to the standards.

Table 9 contains the maximum values of the electric and magnetic fields and also the maximum SAR values for a better comparison.

Table 9.

Maximum values of the parameters of interest when considering different distances between the antenna and the human body.

6. Conclusions

The initially analyzed antenna structures exhibit compact geometries and demonstrate satisfactory performance within the targeted frequency range. Based on prior investigations of similar configurations referenced in this work, it can be inferred that, through the implementation of an appropriate impedance matching or adaptation network, these structures can be effectively tuned to operate across other frequency bands as well.

Comparing the two initial structures, the optimum was determined from the gain point of view and, by applying different geometrical variations, a better structure was obtained.

The proximity of identical antennas leads to a modification in the electromagnetic distribution, which may affect the overall performance. For applications in which signal stability and independent operation are critical, it is recommended to maintain a sufficient separation distance between antennas to minimize coupling and interference effects.

Regarding the distance between the human body and the antenna, it can be concluded that maintaining a spacing of at least 10–15 mm is essential to ensure user safety in wearable or body-proximal RFID applications when considering the human hand, but a larger distance from the antenna to the foot must be considered of at least 20 mm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C., D.T., C.P., A.G.; methodology, C.C., D.T., A.G. and C.P.; validation, C.C., A.G., C.P., M.G., L.R. and S.A.; formal analysis, C.C. and L.G.; investigation, C.C., C.P., A.G. and S.A.; resources, S.A., L.R. and M.G.; data curation, C.C., C.P. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, A.G., C.P. and L.G.; visualization, L.R., S.A. and M.G.; supervision, C.P. and A.G.; project administration, C.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Academy of Romanian Scientists, grant number 31/08.04.2024, “Digitalizarea procesului de proiectare al antenelor multifrecventa RFID si evaluarea expunerii umane la radiatiile emise de acestea”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained in the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Academy of Romanian Scientists, project title: Digitalization of the Design Process for Multifrequency RFID Antennas and Evaluation of Human Exposure to the Radiation Emitted by Them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identification |

| NFC | Near-Field Communication |

| ETSI | European Telecommunications Standards Institute |

| HFSS | High-Frequency Structure Simulator |

| UHF | Ultra-High Frequency |

| ESR | Equivalent Series Resistance |

| ESL | Equivalent Series Inductance |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ICNIRP | International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| SAR | Specific Absorption Rate |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- Greard, R.; Himdi, M.; Lemur, D.; Le Dem, G.; Thaly, P.; Le Meins, C. A Semi-Elliptical UWB Folded Dipole Antenna. Electronics 2023, 12, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Tan, Q.; Cheng, K.; Fan, K. A Wideband Folded Dipole Antenna with an Improved Cross-Polarization Level for Millimeter-Wave Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehiro, K.; Nakashima, K.; Ito, K.; Aibara, E.; Sakakibara, K.; Youssef, K.; Kanaya, H. Development of Metal-Compatible Dipole Antenna for RFID. Electronics 2025, 14, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Su, S.; Xiong, J. A wireless slot-antenna integrated temperature-pressure-humidity sensor loaded with CSRR for harsh-environment applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 311, 127907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgese, M.; Dicandia, F.A.; Costa, F.; Genovesi, S.; Manara, G. An Inkjet Printed Chipless RFID Sensor for Wireless Humidity Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 4699–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, N.; Seet, B.C. 24 GHz Flexible Antenna for Doppler Radar-Based Human Vital Signs Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Xu, L.; Bao, N.; Qi, L.; Shi, J.; Yang, Y.; Yao, Y. Research on Non-Contact Monitoring System for Human Physiological Signal and Body Movement. Biosensors 2019, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouali, R.; Ouahmane, H.; Khan, J.; Liaqat, M.; Bhaij, A.; Ahmad, S.; Haddad, A.; Aoutoul, M. Improved Stable Read Range of the RFID Tag Using Slot Apertures and Capacitive Gaps for Outdoor Localization Applications. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Seco, F.; Milanés, V.; Jiménez, A.; Díaz, J.C.; De Pedro, T. An RFID-Based Intelligent Vehicle Speed Controller Using Active Traffic Signals. Sensors 2010, 10, 5872–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharat, V.; Colin, E.; Baudoin, G.; Richard, D. Indoor performance analysis of LF-RFID based positioning system: Comparison with UHF-RFID and UWB. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Sapporo, Japan, 18–21 September 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarone, A.; Mondal, S.; Aliakbarian, B.; Chahal, P. Miniaturization of Multifunctional Low Frequency RFID Coil Antenna for Embedded Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and North American Radio Science Meeting, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 1349–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, E.; Lucano, E.; Censi, F.; Triventi, M.; Calcagnini, G. Provocative Testing for the Assessment of the Electromagnetic Interference of RFID and NFC Readers on Implantable Pacemaker. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2016, 58, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomaa, K.; Ndagijimana, F.; Ayad, H.; Fadlallah, M.; Jomaah, J. Near-field characterization for 13.56 MHz RFID antenna. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility–EMC EUROPE, Angers, France, 4–8 September 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benassi, F.; Masotti, D.; Costanzo, A. Engineered and miniaturized 13.56 MHz omnidirectional WPT system for medical applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on RFID Technology and Applications (RFID-TA), Pisa, Italy, 25–27 September 2019; pp. 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, R.; Palazzi, V.; Roselli, L.; Copparoni, L. A 13.56 MHz Time-Division Wireless Power and Data Transfer System. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th International Conference on RFID Technology and Applications (RFID-TA), Cagliari, Italy, 12–14 September 2022; pp. 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namadmalan, A.; Duffy, M. Design of Domino-Resonators for Enhanced Power and Data Transmission of 13.56 MHz RFID Sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 20825–20833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zradziński, P.; Karpowicz, J.; Gryz, K. Evaluation of the effect caused by hearing implants on SAR in a body approaching an RFID reader emitting at a frequency of 13.56 MHz. In Proceedings of the 2018 EMFMed 1st World Conference on Biomedical Applications of Electromagnetic Fields (EMF-Med), Split, Croatia, 10–13 September 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, C.; Pacurar, C.; Giurgiuman, A.; Munteanu, C.; Andreica, S.; Gliga, M. High Gain Improved Planar Yagi Uda Antenna for 2.4 GHz Applications and Its Influence on Human Tissues. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleruyelle, T.; Auguste, A.; Sananes, F.; Oudinet, G. Nondestructive Diagnostic Measurement Methods for HF RFID Devices With AI Assistance. IEEE Open J. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 2, 2500910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abkari, S.; Jilbab, A.; El Mhamdi, J. RFID Medication Management System in Hospitals. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. (Ijoe) 2020, 16, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.N.; Bashar, S.S.; Al Mahmud, A.; Miah, S.; Zadidul Karim, A.H.M.; Marium, M. A Security System for Kindergarten School Using RFID Technology. J. Comput. Commun. 2019, 7, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, C.; Pacurar, C.; Giurgiuman, A.; Munteanu, C. Influence of the Conventional and Planar Yagi Uda Antenna on Human Tissues. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advancements of Medicine and Health Care through Technology MEDITECH 2022, IFMBE Proceedings, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 20–22 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 102, pp. 87–98, ISBN 978-3-031-51119-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, C.A.; Adeyeye, A.O.; Eid, A.; Hester, J.G.D.; Tentzeris, M.M. 5G/mm-Wave Next Generation RFID Systems for Future IoT Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on RFID Technology and Applications (RFID-TA), Delhi, India, 6–8 October 2021; pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawan, C.T.; Shivaraj, S.H.; Kounte, M.R. RFID Characteristics and Its role in 5G Communication. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI)(48184), Tirunelveli, India, 15–17 June 2020; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, V.L.G.; Magri, V.P.R.; Ferreira, T.N.; Matos, L.J.; Castellanos, P.V.G.; Silva, M.W.B.; Briggs, L.S. Swivel low cost prototype and Automatized Measurment Setup to Determine 5G and RFID Arrays Radiation Pattern. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 3rd 5G World Forum (5GWF), Bangalore, India, 10–12 September 2020; pp. 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Sharma, S.; Khanna, R. A Spiral Shaped Loop Fed high Read Range Compact Tag Antenna for UHF RFID Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on RFID Technology and Applications (RFID-TA), Pisa, Italy, 25–27 September 2019; pp. 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răcășan, A.; Munteanu, C.; Țopa, V.; Păcurar, C.; Hebedean, C.; Lup, S. Advances on Parasitic Capacitance Reduction of EMI Filters; Analele Universitatii din Craiova, Seria Inginerie Electrica: Craiova, România, 2010; pp. 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, K.V.S.; Nikitin, P.V.; Lam, S.F. Antenna design for UHF RFID tags: A review and a practical application. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2005, 53, 3870–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelladi, R.; Djeddou, M.; Benssalah, M. Design and implementation of passive UHF RFID system. In Proceedings of the 2012 24th International Conference on Microelectronics (ICM), Algiers, Algeria, 17–20 December 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Alam, T.; Yahya, I.; Cho, M. Flexible Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID) Tag Antenna for Sensor Applications. Sensors 2018, 18, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesh, M.; Akbar, M.F. A Low-Profile Symmetric Dipole UHF RFID Tag Design With Wide Tuning Range for Metallic Platforms. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2025, 9, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesh, M.; Firdaus Akbar, M.; Azlin Ghazali, N. Compact Dipolar Patch UHF RFID Tag Antenna Using Interdigital Capacitor for Metal Platforms. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 157249–157263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, M.A.; Ripin, N.; Rahim, M.K.A.; Samsuri, N.A. Compact on-Metal UHF RFID Tag Antenna. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Telecommunication and Networking Technologies (ATNT), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 9–10 September 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.U.; Carvalho, N.B. Dual-Band Loop Antenna for UHF RFID and ISM Band. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 13th International Conference on RFID Technology and Applications (RFID-TA), Aveiro, Portugal, 4–6 September 2023; pp. 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrukhin, I.R.; Yelizarov, A.A.; Bashkevich, S.V.; Nazarov, I.V. Research of the Electrodynamic Parameters of UHF RFID Tags. In Proceedings of the 2023 Systems of Signals Generating and Processing in the Field of on Board Communications, Moscow, Russian Federation, 12–14 March 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, C.; Andreica, S.; Laszlo, R.; Giurgiuman, A.; Gliga, M.; Munteanu, C.; Pacurar, C. Numerical Modeling, Analysis, and Optimization of RFID Tags Functioning at Low Frequencies. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacurar, C.; Topa, V.; Giurgiuman, A.; Munteanu, C.; Constantinescu, C.; Gliga, M.; Andreica, S. High Frequency Analysis and Optimization of Planar Spiral Inductors Used in Microelectronic Circuits. Electronics 2021, 10, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacurar, C.; Topa, V.; Constantinescu, C.; Munteanu, C.; Gliga, M.; Andreica, S.; Giurgiuman, A. Adapting the Formula for Planar Spiral Inductors’ Inductance Computation to the New Oval Geometric Shape, Ideal for Designing Wireless Power Transfer Systems for Smart Devices. Mathematics 2025, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jana, A.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Burokur, S.N.; Genevet, P. Exploiting hidden singularity on the surface of the Poincaré sphere. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tian, G.Y.; Marindra, A.M.J.; Sunny, A.I.; Zhao, A.B. A Review of Passive RFID Tag Antenna-Based Sensors and Systems for Structural Health Monitoring Applications. Sensors 2017, 17, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chechi, D.; Kundu, T.; Kaur, P. The RFID Technology and its Applications: A Review. Int. J. Electron. Commun. Instrum. Eng. Res. Dev. 2012, 2, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP). Guidelines for Limiting Exposure to Electromagnetic Fields (100 kHz to 300 GHz). Health Phys. 2020, 118, 483–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std C95.1™-2019; Standard for Safety Levels with Respect to Human Exposure to Electric, Magnetic, and Electromagnetic Fields, 0 Hz to 300 GHz. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- ETSI. EN 50364; Limitation of Human Exposure to Electromagnetic Fields (0 Hz to 300 GHz). European Telecommunications Standards Institute: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.