Abstract

Grounding Systems (GS) play a critical role in electrical safety, lightning protection, and the reliable operation of power and renewable energy infrastructures, particularly in high-resistivity soils. In this context, Ground Enhancement Materials (GEM) are widely used to reduce soil resistivity and improve grounding performance. This systematic review analyzes and synthesizes recent advances (2018–2025) in GEM applied to GS, with emphasis on their electrical performance, durability, and environmental sustainability. The review covers conventional GEM, industrial waste-derived materials, and hybrid formulations, evaluating their effectiveness under different soil types and moisture conditions. Comparative analysis of the literature indicates that GEM derived from industrial byproducts and hybrid composites often exhibit superior long-term resistivity reduction due to enhanced moisture retention and material-soil interactions, especially in clay-rich and heterogeneous soils. Sustainability considerations such as environmental impact, material availability, and long-term stability are increasingly influencing GEM selection and design. Overall, this review provides a structured framework for understanding the factors governing GEM performance while highlighting current trends, challenges, and future research directions in the development of sustainable grounding solutions.

1. Introduction

The efficiency and safety of electrical Grounding Systems (GS) are essential for protecting equipment, personnel, and infrastructure in energy, telecommunications, and industrial environments [1]. However, a persistent challenge arises from the high resistivity of soils in dry or rocky regions, which limits the dissipation of fault currents and increases the risk of electric shock, equipment malfunction, and electromagnetic interference [2]. Studies have demonstrated that seasonal moisture fluctuations, chloride migration, and variations in soil texture significantly influence soil conductivity and long-term grounding stability, affecting the overall performance of GS [3].

A central challenge in the reliability of GS lies in the selection and performance evaluation of Ground Enhancement Materials (GEM), which are designed to reduce soil resistivity and maintain stable grounding resistance () under variable environmental and geotechnical conditions. Recent findings indicate that soil moisture distribution, thermal behavior, and resistivity patterns can be significantly influenced by land use practices such as those found in agrivoltaic and large-scale solar farm installations, ultimately affecting grounding performance [4]. Complementary studies have shown that soil electrical resistivity is strongly correlated with important geotechnical index properties such as grain size, plasticity, and density, reinforcing the need to integrate geotechnical diagnostics when evaluating and selecting GEM for field applications [5].

Study of GS originally centered on conductive concretes and bentonite-rich backfills. These materials improved the soil–electrode interface to some extent but did not perform consistently under strong moisture fluctuations [6]. More recent research has expanded toward sustainable materials and improved analytical tools. for example, biochar has gained interest as a renewable additive that promotes carbonation in cementitious mixes and increases long-term stability, making it a candidate for low-impact grounding solutions [7]. FEM simulations have also become common, since they allow researchers to test grounding geometries, evaluate reductions in ground resistance, and study potential and temperature fields generated during faults. These analyses support the design of grounding systems that are both efficient and more robust under variable conditions [8].

Work carried out in arid and semi-arid environments shows that GEM behavior must be evaluated alongside local geotechnical and electrochemical factors. Experiments in desert soils indicate that contact resistance can vary substantially when waste-derived additives are used, reflecting the influence of mineralogy, soil fabric, and degree of compaction [9]. Other studies have shown that moisture migration plays a major role in the evolution of soil conductivity over time, especially in the presence of superabsorbent polymers. These observations reinforce the idea that GEM durability depends on understanding moisture cycles rather than only on initial resistivity tests [10].

Sustainability considerations now strongly influence the development of GEM. Systematic reviews of environmentally oriented composites have shown that several low-impact alternatives can deliver good electrical and mechanical performance while reducing environmental burdens [11]. Research on natural-origin construction materials also suggests that waste-derived and minimally processed components can improve the mechanical and physical behavior of earthen systems, supporting broader efforts to rely on locally available and sustainable resources [12]. Despite this, there is still a gap in studies that evaluate durability, environmental impact, and electrical behavior together; this lack of integrated analyses highlights the need for comprehensive reviews that bring these aspects into a single framework within GEM research.

Therefore, this research seeks to address the following questions:

- What recent evidence (2018–2025) exists regarding the electrical, environmental, and structural performance of GEM?

- How can GEM be systematically classified according to composition, effectiveness, and sustainability criteria?

- What knowledge gaps remain in the literature, and which methodological guidelines should be proposed to standardize the evaluation of GEM?

The objective of this study is to conduct a systematic review under PRISMA 2020 guidelines to evaluate the efficiency, durability, and environmental impact of various GEM, thereby supporting the selection of sustainable solutions for high-resistivity soils and GS applications in renewable-energy and industrial systems.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1, the Introduction, presents the general and specific background of GS, the challenges associated with high-resistivity soils, and the motivation for evaluating sustainable GEM. Section 2, Methodology of the Systematic Review, details the PRISMA 2020-based systematic review protocol, including the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction process, and quality assessment of the selected studies. Section 3, Results, synthesizes the main findings regarding the electrical, environmental, and structural performance of different GEM alternatives, highlighting important variables such as soil resistivity, ground resistance, and long-term stability. Section 4 provides a Discussion that analyzes and compares the results with current industrial practices and emerging research trends while identifying limitations, correlations among variables, and areas requiring further investigation. Finally, Section 5, Conclusions, summarizes the main insights of the study, emphasizes its methodological contributions, and provides recommendations for future research and sustainable applications of GEM in GS.

2. Methodology of the Systematic Review

A systematic review is a type of scientific research study in which the unit of analysis consists of original primary studies addressing a common research topic. In this case, the review focuses on the methods, materials, and technological developments used to improve soil conductivity and performance in GS through the application of GEM.

The objective of this systematic review is to clearly and concretely answer the research question regarding the effectiveness, durability, and environmental impact of GEM, thereby providing a comprehensive and reliable perspective while minimizing potential research biases. This approach enables an objective assessment of the efficiency, stability, and long-term performance of GEM in various soil and environmental conditions.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology is applied to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor. PRISMA provides a standardized checklist and a flow diagram to guide authors in documenting each stage of the systematic review process. Steps such as identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion enhance the clarity and reliability of the results [13].

This systematic review was retrospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) to ensure transparency and reproducibility of the review protocol under the following reference: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/6ZFT4.

This registration ensures transparency in the research process, providing public access to the review protocol and supporting the reproducibility of the employed methodology.

2.1. PRISMA Framework and Protocol

The method used to prepare this article consisted of a comprehensive literature review on GEM for grounding and earthing systems, focusing on their composition, electrical performance, corrosion resistance, and environmental behavior.

The PRISMA 2020 methodology was employed as a reference framework to ensure systematic, transparent, and replicable analysis. The steps followed were:

- 1.

- Define the objective:

- Establish the purpose of the systematic review, focusing on the performance and environmental behavior of GEM used in grounding and lightning protection systems.

- Address the research question on how GEM composition, structure, and installation methods affect soil resistivity and long-term durability.

- 2.

- Develop a protocol:

- Design a protocol including research questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and analysis methods for studies addressing electrical and environmental performance of GEM.

- 3.

- Conduct a comprehensive search:

- Search relevant databases (Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect) to identify publications meeting the established criteria for GEM-based GS.

- 4.

- Select studies:

- Apply inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter relevant works focused on grounding performance, resistivity measurements, corrosion testing, and environmental assessment.

- 5.

- Extract data:

- Collect relevant information from the selected studies, including type of GEM (bentonite, graphite, carbonaceous, polymeric, nanomaterial), soil type, test method (Wenner, fall-of-potential), resistivity reduction (), and corrosion/lixiviation data.

- 6.

- Evaluate study quality:

- Assess methodological quality and potential bias using standardized appraisal tools (e.g., JBI or CASP) to ensure reliability of findings.

- 7.

- Analyze the data:

- Perform descriptive and comparative analyses of electrical performance, stability, and environmental impact, identifying trends and variability across soil conditions.

- 8.

- Interpret the results:

- Discuss findings in relation to existing literature, identifying important challenges and opportunities in GEM design and sustainable grounding applications.

Synthesis Methods

Following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, explicit synthesis procedures were applied to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Eligibility for each synthesis was determined by comparing the electrical, environmental, and methodological characteristics of studies against predefined inclusion criteria.

Data were standardized by normalizing resistivity units (Ωm), harmonizing test methods (Wenner, Schlumberger, or fall-of-potential), and converting reduction rates () into comparable measures.

Results were organized into structured tables summarizing GEM type, test conditions, resistivity improvement, corrosion rate, and durability.

Due to the heterogeneity among experimental setups, a narrative synthesis was primarily applied. Summary statistics were computed when quantitative data were available, and heterogeneity was assessed using standard indices (, ).

Subgroup analyses were conducted by GEM category (mineral, carbonaceous, polymeric, hybrid, or nanomaterial) to identify performance patterns and sources of variability. These steps ensured a methodologically robust and reproducible synthesis process.

2.2. Criteria for Selection and Exclusion of Research

A systematic review demands clear and replicable criteria to guarantee methodological rigor and minimize selection bias. For this study, the following criteria were defined:

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- 1.

- Studies published between 2018 and 2025.

- 2.

- Research addressing earthing/GS that used GEM or related soil conductivity enhancers.

- 3.

- Documents in English or Spanish indexed in Scopus, IEEE Xplore, or ScienceDirect.

- 4.

- Works presenting experimental, modeling, or field data on soil resistivity, corrosion, or long-term performance.

- 5.

- All document types were accepted (articles, conference papers, book chapters, and reviews) provided that they included measurable results.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- 1.

- Studies focusing on unrelated topics such as electromagnetic interference, antenna grounding, microgrids, or electronic shielding.

- 2.

- Papers without quantitative data on resistivity (), ground resistance (), or material degradation.

- 3.

- Patents, short communications, and opinion articles without scientific validation.

- 4.

- Duplicates or incomplete records lacking sufficient metadata.

- 5.

- Articles outside the fields of electrical engineering, materials science, or soil conductivity research.

2.2.3. Literature Search Strategy and Final Scopus Query

This section presents the final search strategy and query string applied in the Scopus database to retrieve the studies included in this systematic review. The search strategy was defined to ensure comprehensive coverage of studies addressing the design, composition, and performance of GEM in GS across diverse soil and environmental conditions.

TITLE-ABS-important(

(earthing OR grounding OR “earthing system*” OR “GS*” OR “ground electrode*” OR “earth electrode*” OR “lightning protection system*”)

AND (“ground* enhancement material*” OR GEM OR backfill OR “earthing backfill” OR “grounding backfill”

OR “soil treatment” OR “conductive concrete” OR bentonite OR graphite OR “coke powder”

OR “carbon black” OR “activated carbon” OR polymer* OR “conductive polymer*”

OR graphene OR CNT* OR “carbon nanotube*” OR nanomaterial* OR nanocomposite*)

AND (“soil resistivity” OR resistivity OR “ground resistance” OR “resistance-to-ground”

OR “earth resistance” OR corrosion OR leaching OR durability OR “life cycle”

OR “environmental impact” OR “cost analysis” OR “performance evaluation”)

)

AND PUBYEAR > 2017 AND PUBYEAR < 2026

AND (LIMIT-TO(LANGUAGE,“English”) OR LIMIT-TO(LANGUAGE,“Spanish”))

The application of this code ensured a transparent and reproducible identification of relevant studies in accordance with PRISMA recommendations for systematic reviews.

2.3. Analysis Guide for Systematic Review

The following framework was used for the analysis: multiple interrelated factors influence the efficiency and performance of GS enhanced with GEM materials; from a technological standpoint, the chemical composition, particle size, and conductivity of the materials directly determine their electrical behavior and long-term stability under variable soil and environmental conditions.

Experimental tests evaluating resistivity reduction (), corrosion rate, and leaching properties were examined to assess the suitability of each GEM formulation for field applications. Installation methods, soil type (clay, sand, calcareous), and moisture content were also identified as critical parameters affecting performance consistency.

The synthesis included results from laboratory and in situ studies, highlighting that materials based on bentonite, graphite, conductive polymers, and carbon nanostructures show significant improvements in conductivity and corrosion resistance. Moreover, hybrid composites and nanomaterial-enhanced GEM exhibit promising results for sustainable and long-life earthing systems.

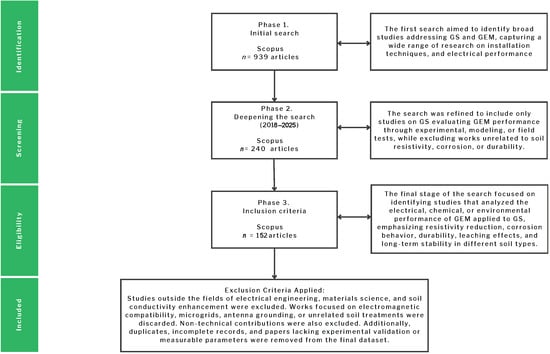

Figure 1 summarizes the selection and exclusion process according to the PRISMA methodology, detailing the number of studies identified, screened, and finally included in this systematic review. In addition, the PRISMA flow diagram is used as a schematic representation of the literature search and selection algorithm, explicitly illustrating the sequential stages from search definition to final study inclusion in accordance with the procedure described in Section 2.2.3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the literature search and selection algorithm adopted in this systematic review, including the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion stages.

2.4. Considerations for GEM in Earthing Systems

To refine the scope of this systematic review, a series of exclusion filters were applied to ensure that only studies directly related to GEM in earthing and lightning protection systems were analyzed. Non-relevant topics such as electromagnetic compatibility, antenna grounding, microgrids, and unrelated soil treatments were excluded. Additionally, non-technical publications, patents without experimental validation, editorials, and duplicates were removed. These criteria ensured that the resulting dataset represented robust and reproducible evidence concerning the electrical, chemical, and environmental behavior of GEM in practical applications.

The analysis revealed that the performance of GEM depends on multiple interrelated factors, both environmental and material-based. Soil composition (clay, sand, calcareous, loam) determines the ionic exchange and moisture retention capacity, directly influencing the soil resistivity () and the efficiency of the installed grounding electrodes. High-resistivity soils require materials capable of maintaining stable conductivity, even under low humidity; consequently, compounds such as bentonite, graphite, and carbonaceous composites are frequently used due to their hygroscopic and conductive properties.

Moisture content and temperature also play crucial roles in GEM performance. Experimental studies have shown that a 10–15% variation in soil moisture can lead to resistivity fluctuations of up to 40%, significantly impacting grounding stability. GEM formulations incorporating conductive polymers and carbon-based nanomaterials (graphene, CNTs) have demonstrated improved stability under these variations, providing both mechanical integrity and resistance to thermal degradation.

Corrosion resistance is another determining parameter for the long-term performance of GS. Aggressive soils with high chloride or sulfate concentrations accelerate electrode deterioration and increase contact resistance. Hybrid GEM compositions such as polymer-modified bentonite or graphite–cement blends help to mitigate these effects by forming a semi-permanent conductive matrix around the electrode that acts as a barrier against oxidation. Additionally, the inclusion of natural enhancement materials (eco-friendly clay–carbon blends) has recently emerged as a sustainable alternative that balances electrical efficiency with reduced environmental impact and leachate toxicity.

From a technological standpoint, current research trends highlight the integration of GEM with advanced diagnostic and predictive models to assess GS performance under real operating conditions. Numerical simulation tools (COMSOL, ANSYS) and empirical field measurements (fall-of-potential and Wenner methods) are commonly employed to correlate material properties with resistivity behavior. These methods facilitate the optimization of GEM composition, electrode configuration, and soil–electrode interface characteristics to achieve cost-effective and durable earthing installations.

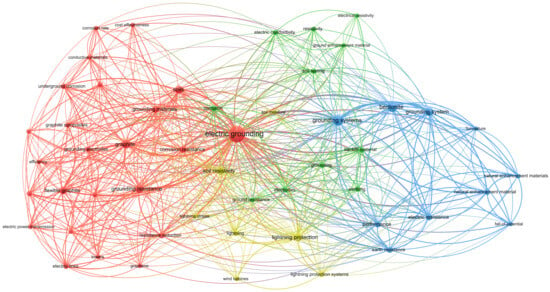

The bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer identified the main thematic clusters structuring global research on GEM between 2018 and 2025. Illustrated in Figure 2, the importantword network reveals dominant terms such as soil resistivity, corrosion rate, graphite composites, lightning protection systems, and ground resistance. This network highlights the multidisciplinary nature of the field, where electrical engineering, materials science, and environmental studies converge to enhance the performance and sustainability of earthing systems.

Figure 2.

Bibliometric importantword network for GEM in GS (2018–2025). The analysis was performed using VOSviewer 1.6.20 based on Scopus database records. The main clusters highlight terms associated with soil resistivity, corrosion rate, graphite composites, and environmental impact.

Notably, three major research fronts were identified:

- The material optimization cluster, emphasizing the development of hybrid and nanostructured GEM to improve conductivity and stability.

- The environmental assessment cluster, focusing on the leaching behavior, recyclability, and eco-toxicity of GEM components.

- The performance modeling cluster, oriented toward predictive analyses and real-world validation of resistivity and corrosion models.

These insights demonstrate a clear transition from purely empirical approaches towards integrated and data-driven methodologies. The incorporation of sustainable materials and the use of advanced modeling tools represent the current evolution of grounding technology toward reliability, cost-efficiency, and reduced ecological footprint.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Resistivity Factors Influencing GEM-Enhanced GS

In this review, soil electrical resistivity is discussed as a governing parameter that directly conditions the effectiveness, durability, and selection of GEM in GS. In this manner, soil electrical resistivity is an important factor in varied fields such as geotechnics, electrical engineering, agriculture and environmental sciences. It plays a crucial role in the design of GS and the characterization of soil properties [14,15,16,17]. Its importance lies in determining the soil’s ability to conduct electricity, which directly affects the safety and performance of electrical systems (Table 1). This resistivity depends on multiple factors, including mineralogical composition, moisture content, temperature, salinity, texture, structure, compaction, and the presence of salts or contaminants [14,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

In order to obtain the electrical resistivity of the soil, it must be known that sandy, silty and clayey soils present different behaviors. Humidity and the fine fraction (clay) are the most influential factors, followed by density and salinity [14,19,22,23,24]. For the measurement of resistivity, non-destructive geophysical methods such as the Wenner array or electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) should mainly be considered; these allow continuous and three-dimensional profiles of the subsoil to be obtained [16,27,28,29,30,31].

Soil resistivity in GS is influenced by the electrode resistance and long-term effectiveness of the electrodes, and it is crucial to consider the spatial and temporal variability of the parameter as well as reduction mechanisms such as the addition of salts or water. Therefore, integrations of advanced predictive models and artificial intelligence techniques have been carried out, which have improved the accuracy in resistivity estimation and its relationship with geotechnical properties [15,25,32]. However, challenges remain related to soil heterogeneity, the influence of the structure, and the need for context-specific calibrations [14,20,33].

Table 1.

Summary of main statements regarding the factors that influence soil resistivity.

Table 1.

Summary of main statements regarding the factors that influence soil resistivity.

| Claim | Reasoning | References |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture is the most influential factor in soil resistivity | Robust and widely validated inverse relationship in laboratory and field | [14,19,26,34,35,36] |

| Mineral composition (clay, plasticity) reduces resistivity | Strong correlations, especially in fine and heterogeneous soils | [14,19,35,37,38,39] |

| Salinity significantly decreases resistivity | Proven effect in saline soils and validated in models and experiments | [36,40,41,42] |

| Compaction and dry density affect resistivity | Moderate influence, dependent on soil type and degree of saturation | [39,43] |

| Multivariable models and AI improve resistivity prediction | Better fit and generalization, although they require specific calibration | [37,44,45] |

| Structure and texture can locally modify resistivity | Relevant effect but less quantifiable, depending on heterogeneity and the presence of macropores | [20,42,46,47] |

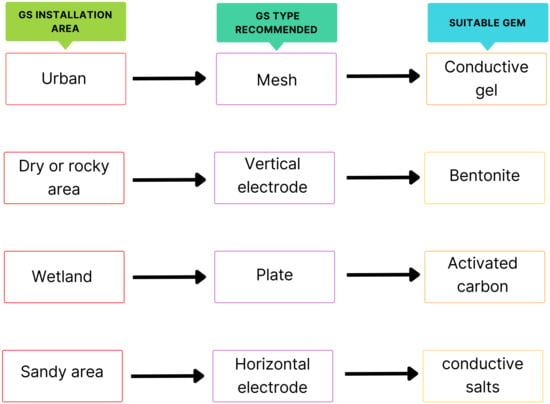

Based on the factors influencing soil resistivity summarized in Table 1, Figure 3 [48] provides a conceptual visualization of representative GS configurations and the associated use of GEM under different installation environments. Likewise, Figure 3 illustrates how variations in soil properties translate into distinct grounding strategies.

Figure 3.

Conceptual flow diagram illustrating representative GS configurations according to installation environment, GS type recommended, and suitable GEM.

3.1.1. Factors That Affect Soil Electrical Resistivity

Among the factors that affect soil resistivity, moisture is the most influential factor, showing a nonlinear inverse relationship: the higher the water content, the lower the resistivity, which is due to the increased ionic mobility and the formation of conductive pathways [14,19,30,34,35,36,37].

Mineral composition, especially clay content and plasticity, also reduces resistivity, while the coarse fraction (sand) tends to increase it [14,19,35,38,39]. The salinity of the pore water significantly decreases resistivity, and this effect is more pronounced in fine soils [40,41,42]. Temperature affects resistivity, but its influence can be normalized in predictive models [46,49].

Table 2 provides a summary of the main relationships between various factors and soil resistivity, along with important observations for each factor. It highlights that humidity, dry density, plasticity index, and salinity exhibit an inverse relationship with respect to resistivity, and shows that multivariate models improve the prediction of this parameter. Furthermore, moisture, porosity, temperature, and fluid composition affect resistivity; a decrease in its value is observed with higher saturation and lower porosity, showing abrupt changes near 0 °C [50].

Table 2.

Comparison of factors affecting soil electrical resistivity.

The clay type and percentage, coarse fraction, moisture, and temperature have an optimal fit in hyperbolic models, with moisture and clay content being the dominant factors. Temperature data normalization is recommended to improve model accuracy [19]. Regarding temperature, clay content, salinity, and density, multivariable models explain resistivity better, although density and temperature show lower sensitivity in this context [46].

Finally, moisture, dry density, and pore structure also affect resistivity, with this parameter decreasing with higher moisture and density. In this case, a volumetric model is proposed to better describe the relationship between these factors [51].

In this way, the soil resistivity factors analyzed here provide the necessary context for understanding GEM behavior, while the subsequent sections focus on the comparative performance, durability, and sustainability implications of different GEM.

3.1.2. Soil Types and Physical Properties

Sandy soils are those with higher resistivities than silty and clayey soils, which is due to their lower water retention capacity and lower fine fraction content [28,35]. Clayey soils that have a higher cation exchange capacity and a higher specific surface area show low resistivities, especially when they are humid or saturated [34,39]. In addition, compaction and dry density influence resistivity, since they modify the porosity and the degree of saturation [43]. The structure and texture of the soil as well as the presence of salt and contaminants can locally modify the resistivity [42,46,47].

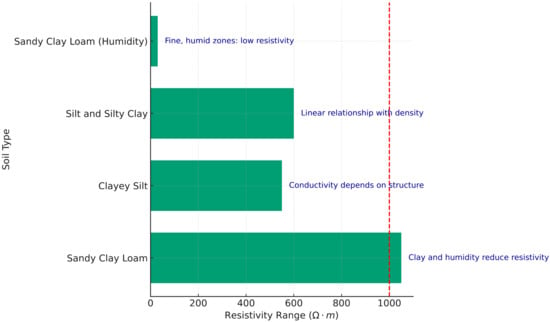

Table 3 presents how resistivity is affected by different soil types and how moisture and mineral composition affect this parameter. In sandy loam/clay soils, resistivity varies between 19 and 1094 Ωm, and the presence of clay and moisture is observed to reduce resistivity [52]. In silty clay soils, resistivity decreases with increasing moisture and density, and conductivity is also strongly influenced by soil structure [51].

Table 3.

Comparison of resistivity by soil type and moisture.

In silty and silty clay soils, resistivity also decreases with respect to moisture content, showing a linear relationship with density [34]. Finally, in clay loam soils with moisture content ranging from 10.2% to 18.6%, areas with fine particles and higher moisture content show low resistivity, highlighting that moisture plays a crucial role in reducing resistivity [25].

Figure 4 illustrates how resistivity is affected in different soil types. Soils such as sandy clay loam (moisture) and sandy clay loam exhibit lower resistivity ranges, suggesting that both moisture and clay content contribute to the reduction in resistivity in these soils. In contrast, silty and silty clay soils exhibit a linear relationship with respect to density, meaning that their resistivity varies according to the number of particles present. Finally, silty clay soils demonstrate that conductivity is primarily influenced by soil structure. These studies are essential for understanding important factors such as water distribution, soil stability, and other important soil characteristics.

Figure 4.

Variation of resistivity across different soil types.

3.1.3. Soil Resistivity Measurement and Modeling Methods for GEM Assessment

In the context of GEM, soil resistivity measurement and modeling are discussed here primarily as evaluation tools to quantify GEM effectiveness, stability, and sensitivity to soil heterogeneity and moisture variability, rather than as standalone geophysical procedures. In this regard, the Wenner method and Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) are the most widely used techniques, as they provide fast and non-destructive measurements with high spatial resolution [53,54]. While predictive models have evolved from basic empirical correlations to more complex multivariate models and artificial intelligence techniques (such as ANN, SVR and XGB), the latter have improved accuracy by simultaneously considering multiple variables [44,45]. Calibration and correction for factors such as temperature, salinity, and soil type are crucial to ensuring reliable results [39].

Table 4 presents the most used measurement methods and models for estimating soil resistivity along with their accuracy, limitations, and important observations. For the case of methods using two and four electrodes with an alternating current (AC) signal at 50 Hz, it is highlighted that the contact error is reduced when using four electrodes, although the results may be affected by the frequency [50].

Table 4.

Comparison of resistivity measurement and modeling methods.

Hyperbolic models with an R2 fit greater than 0.9 have demonstrated better performance compared to exponential models, as they are independent of soil compaction energy [19]. On the other hand, laboratory studies using nonlinear regression also show high reliability, especially when considering multiple variables; this method is recommended for the design of GS due to its high accuracy.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) have shown superior performance in heterogeneous soils, although they have limitations due to environmental variability, which can affect the generalization of results [14].

In this way, Table 4 summarizes the main soil resistivity measurement and modeling approaches and their relevance for evaluating GEM. Four-electrode configurations such as the Wenner method are particularly suitable for GEM assessment because they reduce contact resistance errors introduced by highly conductive backfill materials.

Predictive and data-driven models such as multivariable formulations and artificial neural networks are especially useful for GEM-based grounding systems, since they capture nonlinear effects associated with moisture variability, soil heterogeneity, and material–soil interactions. Overall, the methods presented in Table 4 support a reliable assessment of GEM effectiveness, durability, and long-term performance under both laboratory and field conditions.

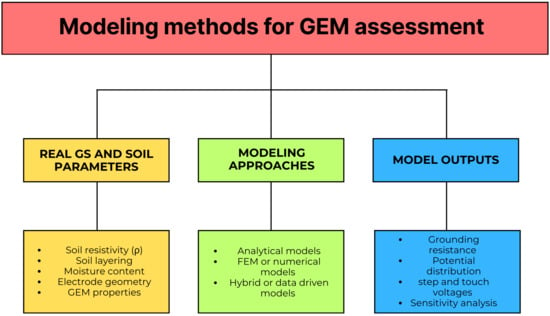

Likewise, Figure 5 [26] presents a schematic overview linking physical inputs, modeling techniques, and typical outputs used in GS analysis, helping to clarify the relationship between real GS parameters and the modeling approaches commonly reported in the literature.

Figure 5.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the relationship between real GS and soil parameters, modeling approaches used for GEM assessment, and typical model outputs.

3.1.4. Applications in GS and Resistivity Reduction

Soil resistivity is essential for the design of GS, since it determines the electrical resistance of the electrodes and the safety of electrical installations [14,55,56]. Soils with high resistivity require reduction strategies such as the addition of salt or water or the use of special electrodes [56]. In addition, it is necessary to consider temporal (seasonality, drought, frost) and spatial (heterogeneity, stratification) variability in order to ensure long-term effectiveness [55,57].

Table 5 summarizes the applications and contexts in which soil resistivity has been studied along with important findings. For the design of GS, the importance of accurate measurement and proper selection of critical axes to ensure system safety is highlighted [2]. Regarding the design of GS, it has been observed that dry soils require a greater number of electrodes to maintain adequate current conduction efficiency [58].

Table 5.

Comparison of applications and strategies in GS.

Regarding improvement materials, it has been shown that wood ash effectively reduces contact resistance and can improve the efficiency of GS [9]. Furthermore, in the context of impulse currents, it has been observed that addition of NaCl (common salt) significantly decreases resistivity in sandy and clayey soils, which can be useful for optimizing conductivity in certain scenarios [59].

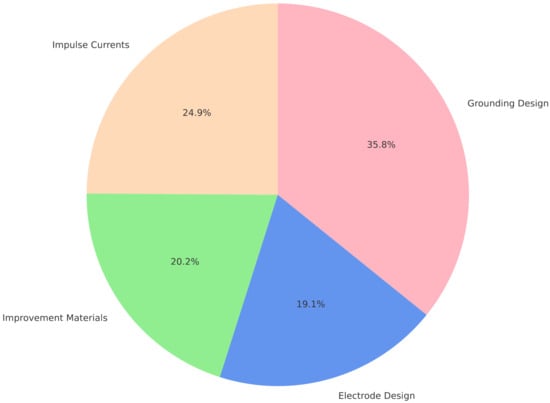

Figure 6 presents a pie chart with a clear distribution of important findings across various applications and contexts, showing how different topics are prioritized within the study area. GS design stands out as the most significant area with 35.8% of the findings, suggesting that it is a major concern or focus of the analysis. Impulse currents occupy second place with 24.9%, reflecting considerable attention to this phenomenon, possibly due to impact or relevance to the field of study. Electrode design and enhancement materials both occupy similar portions, with 19.1% and 20.2%, respectively, indicating that these aspects receive significant attention, albeit to a lesser extent compared to the aforementioned areas.

Figure 6.

Pie chart with a clear distribution of important findings in the articles.

3.2. GEM According to the Scientific Literature

The reliable operation of a GS depends on low soil electrical resistivity, making its reduction a crucial design goal [50]. Materials of both natural and synthetic origin have been applied to improve soil conductivity, though they differ in their properties and how they function. For example, natural materials such as bentonite, zeolite, and plant ash offer a cost-effective and sustainable solution. These are especially useful for treating soils with high natural resistivity, such as sand [60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. While salts and chemical compounds provide the most significant resistivity reduction, they also introduce major drawbacks, including corrosion risks and the need for regular maintenance [59,62,67,68,69].

Other categories such as synthetic polymers are valued for their ability to stabilize soil moisture and resistivity over the long term. This makes them a reliable choice for variable climatic conditions [70,71,72]. Waste-derived materials offer a sustainable path, enabling the reuse of industrial and agricultural byproducts to reduce costs. Their main drawback is that their performance can be inconsistent [73,74,75,76]. Likewise, commercial mixtures are formulated to achieve a balance between efficiency, stability, and adaptability. This balanced performance typically comes at a higher cost [48,69,70,75,77]. Table 6 provides a general classification of these different GEM types used as soil resistivity reduction agents.

Table 6.

Classification of materials used as GEM to reduce soil resistivity.

It is apparent that the selection of the optimal material depends on factors such as soil type, climatic conditions, environmental impact, cost, and maintenance requirements. The current trend favors sustainable and low-impact solutions without compromising the electrical efficiency of the GS. Table 7 classifies the main materials used as GEM and summarizes their important relevant properties, highlighting the most extensively studied materials according to the recent and relevant scientific literature.

Table 7.

Summary of materials used as Ground Enhancement Materials (GEMs) to reduce soil resistivity.

3.2.1. Comparative Evaluation of the Effectiveness of GEM Used in GS

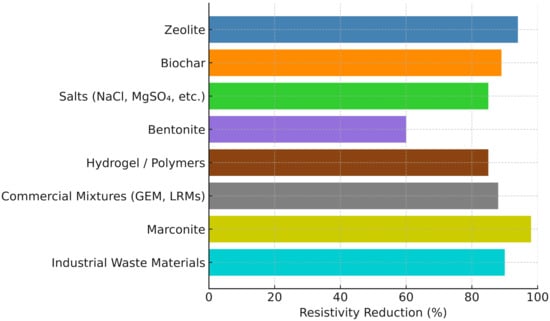

Comparative evaluation of GEM effectiveness allows for identifying those materials that exhibit superior performance in the GS. Figure 7 summarizes the average resistivity reduction values reported in the recent literature (Table 7), which are expressed as percentages relative to untreated soil. The analyzed GEM include natural, chemical, synthetic, industrial, and commercial options, reflecting the diversity of existing approaches aimed at optimizing the electrical conductivity and long-term stability of GS.

Figure 7.

Effectiveness of soil resistivity reduction materials.

Figure 7 shows that the effectiveness of GEM varies according to nature and composition. Among natural materials, zeolite stands out with resistivity reductions of up to 94%, followed by biochar (89%) and bentonite (60%), the latter being valued for its stability and low corrosivity. Chemical salts provide a rapid reduction (85%) but exhibit corrosion issues and gradual loss of effectiveness over time. Hydrogels and polymers achieve stable reductions (80–90%) by maintaining constant moisture levels, while Marconite reaches the highest efficiency (≈99%), albeit at higher cost. Finally, industrial residues and commercial mixtures such as LRMs combine good efficiency, stability, and sustainability, representing balanced solutions for long-term applications.

In general, the effectiveness of a GEM depends not only on its conductivity but also on its moisture retention capacity, chemical stability, and compatibility with the soil type [9]. Recent studies have emphasized the development of sustainable hybrid mixtures such as bentonite combined with hydrogel, graphite, or biochar, which integrate electrical efficiency, durability, and low environmental impact.

3.2.2. Relationship Between Electrical Efficiency and Environmental Impact of GEM

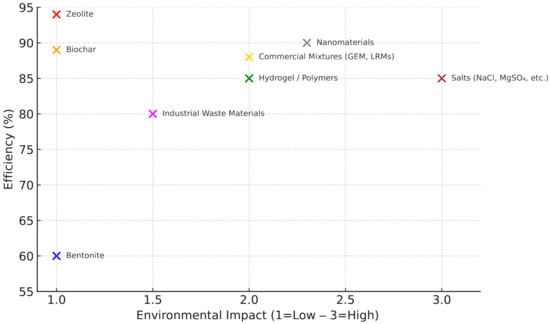

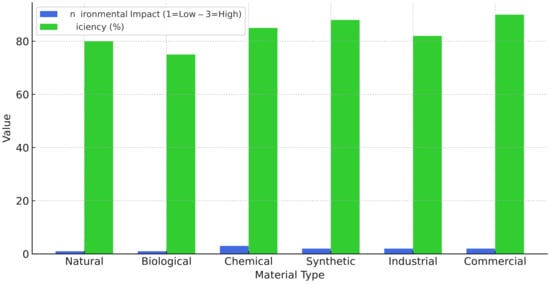

The relationship between the electrical efficiency and environmental impact of GEM is a fundamental criterion for selecting sustainable solutions in GS [88].

Figure 8 presents a qualitative scatter plot comparing the resistivity reduction capacity (%) of various materials with their level of environmental impact, classified according to their origin (natural, chemical, synthetic, industrial, or commercial).

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of electrical performance and environmental impact of various materials.

The vertical axis represents electrical efficiency, while the horizontal axis indicates the degree of environmental impact on a scale from 1 (low) to 3 (high). This graphical representation enables visualization of the balance between technical performance and ecological sustainability.

Natural materials such as bentonite, zeolite, and biochar combine high efficiency with low environmental impact, occupying the optimal region of the plot. Hydrogels, commercial mixtures such as LRMs, and Marconite achieve high efficiency with moderate impact, representing stable but more expensive solutions. In contrast, chemical salts exhibit high environmental impact despite their strong initial resistivity reduction. Overall, the analysis demonstrates that hybrid and sustainable materials offer the best balance between electrical efficiency, durability, and low ecological impact.

3.2.3. General Classification of GEM

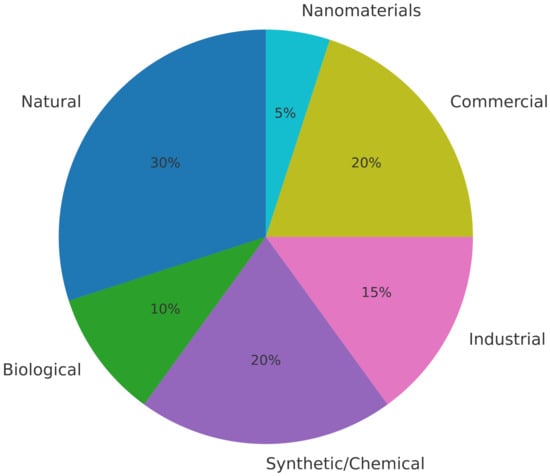

The classification of GEM forms the basis for understanding their physicochemical behavior and applicability in GS [9]. These materials are grouped into six main categories: natural, biological, synthetic, industrial, commercial, and nanomaterials, each with distinctive electrical, chemical, and environmental characteristics that determine their performance across different soil types and climatic conditions. Figure 9 illustrates the general classification of the GEM analyzed in this study. This classification confirms that the selection of materials should not be based solely on their conductivity but also on their stability, ecological impact, and lifecycle cost.

Figure 9.

GEM classification by type.

Natural materials such as bentonite, zeolite, and biochar are widely used due to their low cost, abundance, and environmental compatibility, providing moderate to high reductions in soil resistivity through their ability to retain moisture and exchange ions. Biological materials derived from organic compounds or plant residues contribute to long-term stability, although their effectiveness may vary due to biological degradation [9]. In contrast, synthetic or chemical materials such as salts or absorbent polymers offer rapid and significant reductions in resistivity but carry risks of corrosion and environmental contamination [69]. Industrial residues such as ash, gypsum, and cement waste have gained importance as sustainable alternatives [82]. Commercial mixtures such as Marconite combine conductive and absorbent additives to optimize both conductivity and durability [86], while nanomaterials are still in an experimental stage, but exhibit exceptional electrical properties even in minimal quantities [83].

The classification chart in Figure 9 reveals that natural materials dominate current applications, representing over 30% of reported cases, followed by synthetic and commercial ones. This trend reflects a transition toward sustainable and low-cost solutions consistent with modern environmental demands. The growing use of commercial mixtures is attributed to their stable and predictable performance, whereas traditional chemical materials are being progressively replaced due to their corrosive nature and high environmental impact. Meanwhile, the reuse of industrial residues and the development of nanomaterials highlight a shift toward circular economy models within electrical engineering.

3.2.4. Comparison of Advantages and Disadvantages of GEM

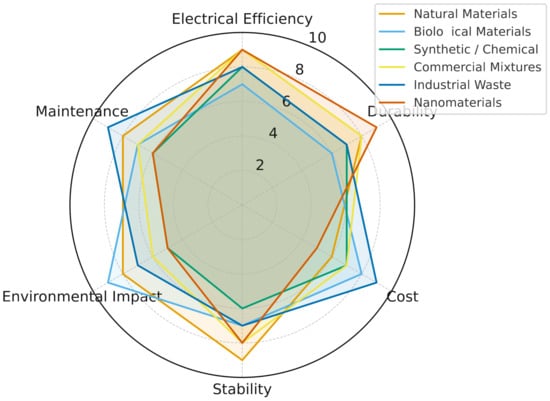

The multidimensional comparison of GEM allows for an assessment of their overall performance. The radar chart in Figure 10 integrates six critical parameters: electrical efficiency, durability, cost, environmental impact, stability, and maintenance, providing a comprehensive view of the performance of each material category. This tool facilitates the identification of materials that achieve an appropriate balance between technical performance and environmental sustainability. Moreover, this analysis confirms that multi-criteria evaluation is essential for material selection.

Figure 10.

Comparative performance of GEM categories.

According to Figure 10, no single category excels in all parameters; instead, each exhibits specific strategic advantages. Commercial mixtures and nanomaterials offer the best overall technical balance, combining efficiency, durability, and stability with low maintenance requirements. Although less efficient, natural and biological materials stand out for their low environmental impact and cost, making them suitable for rural areas or locations with limited infrastructure. Synthetic and chemical materials require strict environmental management to prevent soil degradation, despite their high initial performance. Meanwhile, industrial residues serve as an intermediate link between economic feasibility and sustainability while aligning with resource reuse objectives.

Thus, the radar comparison in Figure 10 illustrates a transition from the traditional conductivity-based paradigm towards an integrated technological sustainability approach in which optimal material selection depends on balancing electrical efficiency, stability, environmental impact, and lifecycle cost.

3.2.5. Analysis of Moisture Retention Versus Electrical Efficiency of GEM

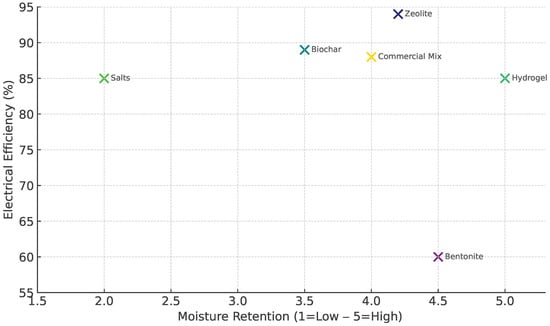

The availability of moisture in the vicinity of the electrode is a determining factor for the electrical performance of GEM used in GS [67]. Because ionic mobility in soil depends directly on water content, materials with higher absorption capacity tend to maintain low resistivity for longer periods [89]. The scatter plot in Figure 11 analyzes the correlation between moisture retention capacity (qualitative scale from 1 to 5) and electrical efficiency (percentage of resistivity reduction).

Figure 11.

Moisture retention vs. electrical efficiency.

The results show a clear positive relationship between moisture retention and electrical performance. Materials such as hydrogels, bentonite, and zeolite not only hold moisture effectively but also maintain a stable reduction in resistivity, even under changing weather conditions. Biochar, although it retains moisture at a moderate level, stands out for being renewable and environmentally friendly; in contrast, chemical salts lose effectiveness quickly due to ion leaching and dissolution [70]. Overall, the analysis confirms that water retention is the most influential factor in ensuring long-term electrical stability [48]. To ensure good performance in the field, it is essential to consider local moisture dynamics and choose materials capable of keeping the area around the electrode consistently wet.

3.2.6. Analysis of Cost Versus Efficiency of GEM

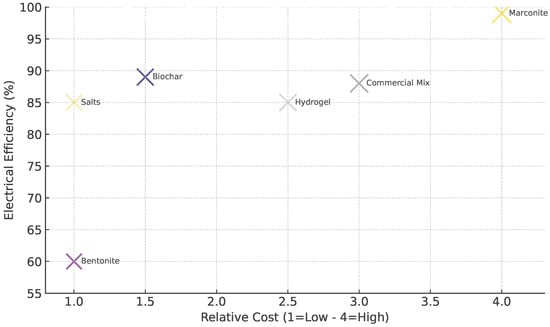

The balance between cost and electrical performance represents an important criterion in the selection of GEM for GS. Figure 12 illustrates the relationship between relative cost, electrical efficiency, and durability (represented by bubble size). This analysis integrates technical and economic factors, providing a comprehensive perspective for decision-making in electrical engineering projects.

Figure 12.

Cost vs. efficiency.

Analysis of Figure 12 indicates that low-cost materials such as bentonite and biochar provide acceptable efficiency (60–89%) and moderate durability, making them suitable for standard installations. Medium-cost materials such as hydrogels and hybrid mixtures achieve a favorable balance between stability, efficiency, and economic viability.

Finally, high-cost materials such as Marconite and commercial mixtures reach efficiencies close to 99%, justifying their use in critical or permanent systems. This demonstrates that cost alone cannot be the sole selection criterion, and must be evaluated alongside chemical stability and maintenance requirements. Consequently, sustainable hybrid materials represent the most advantageous option due to their combination of electrical performance, durability, and economic feasibility.

3.2.7. Environmental Impact According to the Type of GEM Applied to Soil

Environmental sustainability has become an important pillar in modern electrical engineering [90]. The bar chart in Figure 13 compares the average environmental impact (scale 1–3) with the electrical efficiency (%) for each GEM category. The objective is to analyze the ecological tradeoffs associated with the use of each type of compound.

Figure 13.

Environmental impact and efficiency by material type.

From Figure 13, it can be observed that natural and biological materials exhibit the lowest environmental impact (≈1) while maintaining acceptable efficiencies (75–85%). Synthetic and commercial materials achieve high efficiencies (>88%), though they show moderate environmental impact due to their polymeric or carbon-based components [73]. Chemical salts exhibit the highest environmental impact because of their corrosive nature and potential contamination risk [48]. Industrial residues provide a sustainable alternative, as they reuse by-products and achieve efficiencies above 80%.

This analysis confirms that electrical efficiency and sustainability can coexist, particularly through the use of eco-engineered formulations designed to meet sustainable development objectives.

3.2.8. Research Trends (Temporal Analysis)

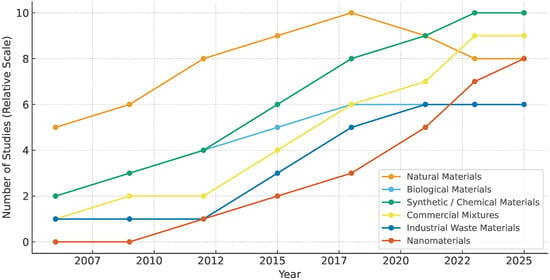

The study of scientific trends enables the identification of technological advancements and emerging research directions. Figure 14 illustrates the evolution of research interest across different GEM categories between 2007 and 2025 on the basis of a comprehensive bibliographic analysis. The purpose of this representation is to highlight shifts in scientific and technological focus over time, evidencing the transition from conventional materials toward sustainable and high-performance solutions.

Figure 14.

Research trends by GEM category.

Figure 14 reveals a clear diversification of research lines over the past two decades. In the first stage (2007–2012), attention was mainly focused on natural GEM such as bentonite and zeolite due to their low cost and wide availability. These materials dominated the early landscape, forming the technological foundation of traditional GS.

From 2012 onward, there has been steady growth in studies involving synthetic GEM and commercial mixtures, driven by the pursuit of higher stability, durability, and electrical performance. Interest in biological materials has also gradually increased in response to environmental sustainability policies and the integration of ecological criteria in electrical system design [91].

Between 2018 and 2021, research on industrial residues gained prominence, supported by circular economy strategies promoting the reuse of industrial byproducts for conductive applications [83]. Simultaneously, nanomaterials emerged as a cutting-edge research line, characterized by high conductivity, low mass, and strong potential for hybrid applications [92].

Finally, during the 2023–2025 period, the global trend converges toward a multidisciplinary approach in which hybrid materials and nanocomposites represent the main axis of innovation. The continuous growth of synthetic, commercial, and industrial categories together with the maturation of nanomaterials reflects a clear technological transition from empirical solutions toward scientifically engineered systems optimized for electrical performance, environmental sustainability, and operational durability.

3.3. Common Soil Stabilizer Mixes Used in GEM

Different material mixtures have been applied to enhance the soil characteristics to be utilized in civil engineering and construction. Recycled materials in common combinations are granulated rubber with granular soils, which help in improving compaction, permeability, strength and dynamic properties, making them friendly to the environment by reusing end-of-life tires [93,94]. Both recycled concrete aggregate and recycled brick aggregate have been demonstrated to confer excellent shear strength, hydraulic conductivity, and compaction properties; even RCA-RBA blends with up to 50% RBA have been found to perform well in the base, sub-base, and embankment of pavement works [95].

Other innovative blends include agro-biogenic composites such as wool–banana fiber, which can significantly improve the strength, resilience, and ductility of expansive clays to make them more suitable for subgrade stabilization [96]. Soil stabilization with clay–lime blends is also common, with research indicating that minimizing binder content and maximizing density can reduce environmental impacts while achieving target strength and stiffness [97,98]. Additionally, the use of crushed slag with marginal lateritic soils improves abrasion resistance and bearing capacity while reducing swelling, making these blends suitable for engineering fill materials in road construction [99]. These material blends not only enhance geotechnical performance but also contribute to sustainability by utilizing waste and recycled materials.

3.3.1. Cement + Lime

One common and effective method of stabilizing soils, especially highly plasticized or clay soils, is to use a blend of cement and lime. The lime process reduces soil plasticity and enhances soil workability by triggering cation exchange and pozzolanic reactions, subsequently resulting in flocculation and decreased swelling potential along with improved compressive strength, durability, and structural resistance brought about by an increase of cement hydration and the development of cementitious compounds [100]. This mixture is particularly useful in improving the load-bearing capacity and long-term stability of subgrade soils in road construction, rural roads, and foundations [101].

It has been found that both additives have significant engineering benefits, including maximum dry density, California bearing ratio, and unconfined compressive strength, with cement typically resulting in greater strength increases and prolonged life than lime alone [102]. The success of the stabilization process is affected by aspects such as soil type, additive concentration, curing duration, and environmental factors, yet the general increases in plasticity, strength, and capacity to resist moisture variations and freeze–thaw cycles are expected to occur in general [103]. Cement and lime stabilization of the soil is also deemed to be cost-effective and environmentally friendly compared to digging and replacing inappropriate soils [104].

3.3.2. Cement + Fly Ash

Soil stabilization is usually carried out by utilizing a mixture of cement and fly ash, notably in pavement and road construction as well as in managing the swelling of clayey soils or expansive soils. Fly ash is a coal combustion byproduct that makes soils more workable, increases their resistance to aging, and minimizes the expansion and swelling potential of clay-based soils. Cement is added to enhance the strength and durability of soils as well as to boost their workability [105]. Studies have revealed that fly ash mixed with cement enhances the unconfined compressive strength, bearing capacity, and cohesion of soils as well as improving the compaction properties and lowering optimum moisture content. This is because research has shown that combining fly ash with cement increases the unconfined compressive strength, bearing capacity, and cohesion of soils, improves their compaction properties, and reduces their optimum moisture content [106].

This combination is specifically good in fine soils and sandy sands with low grades, where it increases shear strength, permeability, and load-bearing capacity. Fly ash also has environmental advantages in that it consists of recycled industrial byproducts and less cement is used in the process. This makes the process even more sustainable and less costly in achieving the desired results and outcomes in the process of compressive strength testing, as well as in analysis of concrete and gypsum properties in construction [107].

3.3.3. Polymers + Sandy Soils

When sandy soils are added with synthetic or natural polymers, the sandy soils become much more coherent and stable, and do not erode; thin mats and interlacing laces between sand particles are formed by polymers such as sodium polyacrylate, guar, and different types of synthetics that improve mechanical strength, permeability, and long-term durability of the structure [108]. Research indicates that polymer-treated sandy soils are characterized by increased shear strength, compressive strength, and toughness. The improvements are proportional to the polymer dosage and the curing period until reaching stability. The literature demonstrates that polymer-treated sandy soils have higher shear strength, compressive strength, and toughness, the enhancement of which increases with the dosage and curing time of the polymer until stability is observed [109].

Such improvements render polymer-stabilized sandy soils exceptionally effective for erosion control in sloping and low-cohesion soils, as well as in soil enhancement for construction of road bases and in agricultural fields [110]. Moreover, treatment with polymers has the potential to enhance water retention and support plant growth by creating an appropriate habitat to aid ecological recovery work efforts [111]. Another benefit of using polymers is relatively short time to cure; for instance, the technical capability to be used in geotechnical projects at different doses was a benefit of the material used in the investigation by Kumar [112].

3.3.4. Bitumen + Aggregate

The mix of bitumen and aggregate has been extensively adopted in soil stabilization, especially in the development of asphalt pavements and where higher impermeability and durability have to be applied. Bitumen is used as an adhesive, covering the particles of an aggregate such as gravel or sand, which improves the compressive strength, wear resistance, and impermeability of the stabilized soil, effectively decreasing water infiltration and increasing its stability over the long term [113]. It has been found that the optimal content of bitumen (usually about 4%) results in higher California bearing ratio and maximum dry density of granular soils, whereas high contents may decrease the strength as a result of over-saturation and aggregate interlock loss [114].

Soils stabilized with bitumen are particularly useful in the subgrades, pavement layers and foundational regions of roadways, where moisture control and resistance to deformation is of vital concern [115]. It is also emphasized in studies that bitumen emulsion (often with limited amounts of cement) also enhances the strength and compaction properties of soil, making such a mixture viable in both rural and urban infrastructure construction [116]. Recycling of waste bitumen to partially replace coarse aggregate in stone columns has been demonstrated to increase bearing capacity, offering a cheap alternative that improves the soil while being cost-effective to recycle [114].

3.4. Functional Principles of Earthing Systems Enhanced with GEM

The primary function of an earthing system is to ensure a low-impedance path for the dissipation of electrical faults and lightning currents into the ground. Traditional soil–electrode interfaces often present high resistivity, especially in dry, rocky, or sandy terrains. The incorporation of GEM modifies this interface by reducing soil resistivity (), stabilizing moisture, and expanding the conductive area around the electrode [117].

The experimental evidence in Table 8 demonstrates that GEM can lower the ground resistance () by 40–80%, depending on the formulation and local soil conditions. Carbonaceous and polymer-based materials offer long-term conductivity stability, whereas bentonite and saline compounds perform efficiently only in high-humidity conditions [118]. Thus, a sustainable grounding design requires balancing electrical efficiency with environmental and corrosion control aspects.

Table 8.

Comparative evaluation of GEM types based on electrical performance and durability.

The data in Table 8 confirm that material composition directly affects the electrical and chemical interaction with the soil. For long-term reliability, it is crucial to select GEM that maintains conductivity under seasonal humidity fluctuations and exhibits minimal corrosive or leaching behavior.

3.4.1. Applications and Field Performance

GEM-enhanced GS have become essential in modern electrical (Table 9). The use of these systems is documented in power substations, transmission towers, communication networks, and renewable energy plants, where they provide reliable dissipation of lightning currents and fault energy even in high-resistivity environments [69].

Field-scale studies conducted in utility-scale photovoltaic plants have reported the use of GEM, including conductive fertilizers that increase soil electrical conductivity through salt leaching mechanisms. These materials have demonstrated a significant reductions in soil resistivity, achieving an average decrease in ground resistance of approximately 4.45 Ω in photovoltaic installations with herbaceous vegetation cultivated beneath solar panels [122].

Similarly, field applications in wind farms highlight the integration of GS designs that combine horizontal and vertical electrodes with conductive enhancement materials to adapt to high-resistivity soils. The use of GEM in conjunction with conventional electrode materials such as galvanized steel or copper contributes to improved grounding performance and enhanced protection against electrical faults and lightning events [123].

Despite wide adoption, many field reports lack long-term resistivity monitoring or environmental evaluation. Thus, the design of earthing systems must include sensors for humidity, temperature, and corrosion potential to ensure consistent performance and predictive maintenance capabilities.

Table 9.

Main applications and performance considerations for GEM-based earthing systems.

Table 9.

Main applications and performance considerations for GEM-based earthing systems.

| Application | Observed benefits | Limitations/Concerns | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical substations | Lower step and touch voltages; improved safety | Requires periodic resistance verification | [69] |

| Transmission line towers | Ensures stable in dry and rocky soils | GEM aging due to heat and drying | [124] |

| Telecommunication towers | Reliable reference grounding; protection of sensitive electronics | Needs moisture monitoring | [125] |

| Photovoltaic/wind energy systems | Integral part of lightning and surge protection networks | Must comply with environmental restrictions | [126] |

3.4.2. Technological Innovations and Optimization Approaches

Recent developments in measurement and modeling techniques (Table 10) have advanced the design of GS. Standard methods such as the Wenner and Schlumberger four-pin tests remain the foundation for soil resistivity evaluation, while computational tools based on FEM allow for simulation of potential distribution, current dissipation, and corrosion mechanisms [2].

From Table 10, it can be noted that the integration of numerical modeling and real-time data acquisition enhances predictive accuracy and allows for continuous optimization of grounding performance.

Table 10.

Technological tools and analytical methods for design and optimization of earthing systems.

Table 10.

Technological tools and analytical methods for design and optimization of earthing systems.

| Technology/Method | Function | Advantages/Challenges | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wenner/Schlumberger method | Measures apparent soil resistivity | Standardized; allows stratified soil analysis; affected by seasonal changes | [127] |

| Fall-of-potential test | Evaluates total grounding resistance () | Simple and reliable; limited by site geometry | [128] |

| FEM modeling (COMSOL, ANSYS) | Simulates electrical field, potential gradient, and corrosion | Enables optimization of GEM geometry and volume; requires accurate parameters | [129] |

| Corrosion and electrochemical testing | Quantifies electrode degradation and leaching | Validates long-term GEM compatibility with metals and soils | [130] |

| Smart sensor networks | Monitors humidity, temperature, and resistance in real time | Enables predictive maintenance and AI integration | [131] |

3.4.3. Environmental and Circular Economy Considerations

Environmental impact assessment is increasingly relevant in the evaluation of GEM. Traditional salt-based enhancers may lead to soil salinization and corrosion of metallic electrodes. Therefore, the use of sustainable and recyclable materials is being prioritized to align with circular economy strategies [132].

- Recycled industrial byproducts such as fly ash, steel slag, and graphite waste reduce landfill volumes and material costs by up to 40% [133].

- Graphite- and carbon-based GEM show minimal ion leaching and stable pH profiles, preserving soil chemistry [134].

- Life cycle assessment studies reveal that replacing bentonite with carbonaceous composites can reduce CO2 emissions by 25–35% [135].

Despite these benefits, the literature still lacks standardized eco-toxicological testing of GEM under long-term leaching conditions. Establishing a harmonized framework for environmental certification remains a critical step for the large-scale adoption of sustainable GEM technologies.

3.4.4. Artificial Intelligence and Predictive Maintenance Integration

Artificial intelligence and machine learning have emerged as transformative tools in GS optimization. Predictive models trained on environmental and operational datasets can estimate the evolution of resistance, corrosion rate, and soil conductivity. Techniques such as neural networks, fuzzy logic, and genetic algorithms have been employed to predict optimal GEM formulations and electrode geometries [136].

The implementation of AI-based monitoring enables the transition from reactive to predictive maintenance. By analyzing temporal variations in , soil humidity, and temperature, intelligent systems can identify early signs of deterioration and recommend corrective actions before failure occurs [137].

Future advancements are expected to combine AI-driven optimization with digital twin models for real-time performance prediction, adaptive maintenance scheduling, and automated design feedback loops [138].

4. Discussion

The results presented in Section 3 indicate that the performance of GEM depends strongly on soil type and material composition. These differences are governed by material–soil interaction mechanisms such as particle size distribution, moisture retention capacity, porosity, and ionic exchange potential, which directly affect conductive pathways at the electrode–soil interface [14].

In particular, industrial waste-derived and hybrid GEM often exhibit superior performance in clay-rich and heterogeneous soils due to their complex mineralogical composition and enhanced moisture retention, which contribute to more stable resistivity reduction under variable environmental conditions [69]. These mechanisms explain the performance trends observed among different GEM categories across the soil types, as analyzed in Section 3.

Likewise, among emerging GEM alternatives, nanomaterial-based formulations represent a particularly promising research direction for future GS [139]. Carbon-based nanomaterials such as graphene derivatives, carbon nanotubes, and nano-structured biochar have demonstrated enhanced electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, and improved interaction with soil particles, which can contribute to more stable conductive pathways under varying moisture conditions. In addition, metal-oxide nanomaterials have been explored for their potential to modify soil electrochemical behavior and improve long-term resistivity performance [120].

However, despite their technical potential, the practical implementation of nanomaterial-based GEM remains limited by several challenges. These include high material costs, scalability constraints, uncertainty regarding long-term environmental impact, and limited field-scale validation. As a result, current research increasingly emphasizes hybrid formulations in which nanomaterials are incorporated in small fractions within conventional or waste-derived matrices as a way to balance performance gains with cost, durability, and sustainability considerations [83].

4.1. Bibliometric Insights on Conductive and Reduction Materials

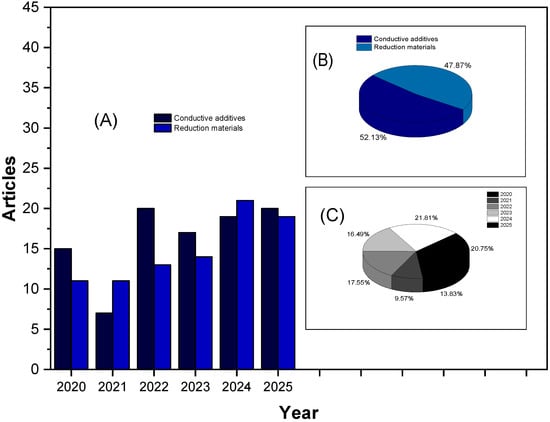

Bibliometric analysis provides a comprehensive view of the recent evolution in scientific research concerning conductive and reduction materials, which are important components in the development of GEM. The following figures summarize two complementary aspects of this research domain: (i) the annual progression of publications in both categories, and (ii) the main thematic areas that define their technological orientation between 2020 and 2025.

Figure 15 (panels A–C) illustrates the temporal behavior of publications associated with conductive additives and reduction materials from 2020 to 2025. The data reveal a consistent increase in the overall research output for both categories, indicating the sustained relevance of materials capable of improving electrical conductivity and electrochemical stability in GS. During the first three years (2020–2022), studies on conductive additives represented the dominant line of investigation, primarily due to their effectiveness in lowering soil resistivity through the inclusion of carbonaceous components such as graphite, carbon black, or coke powder. This phase coincides with a period of strong interest in practical conductivity enhancement, focusing on surface area, particle size, and dispersion efficiency.

Figure 15.

Annual distribution of publications on conductive additives and reduction materials (2020–2025).

A gradual transition is observed from 2023 onward, when reduction materials began to gain prominence in the literature. By 2025, these materials account for 52.13% of the total publications, surpassing the proportion dedicated to conductive additives. This change suggests that researchers are increasingly addressing long-term reliability and electrochemical stability in GS rather than short-term conductivity gains. Reduction materials are valued for their ability to mitigate oxidation, corrosion, and soil–electrode degradation, which directly influences the durability and maintenance requirements of grounding installations. Consequently, the trend captured in Figure 15 reflects an evolution from purely electrical optimization toward a more integrated understanding of electrochemical processes that affect system performance.

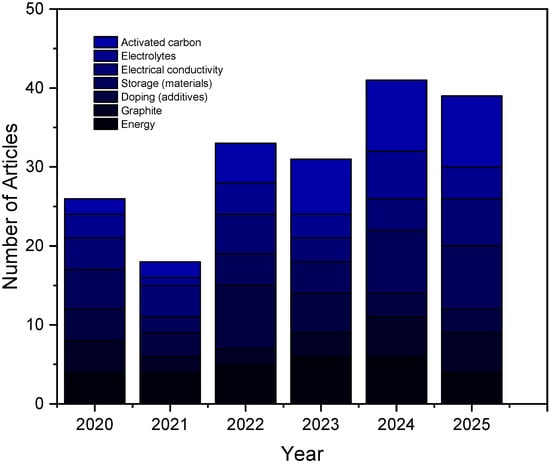

Complementing this trend, Figure 16 presents the most frequently occurring research themes within the same period. The prominence of important words such as activated carbon, electrolytes, and electrical conductivity underscores the continued focus on optimizing charge transport mechanisms and enhancing the conductive framework of GEM formulations. The strong representation of activated carbon reflects its versatility as a porous medium capable of increasing the effective contact area and stabilizing the current distribution in soil environments. Similarly, electrolytes appears as a recurrent theme due to the role of electrolytes in maintaining moisture and ionic balance, both of which are critical to achieving stable resistance over time.

Figure 16.

Main research themes related to conductive and reduction materials (2020–2025): activated carbon, electrolytes, conductivity, doping, graphite, and energy.

Emerging terms such as doping additives, graphite, and energy storage point toward a progressive convergence between GEM research and other areas of materials science. These topics reveal that the same conductive and redox-active mechanisms explored for energy applications such as supercapacitors and battery electrodes are also being adapted for the design of advanced grounding materials. This convergence suggests a broader understanding of how electrical, electrochemical, and surface phenomena can be synergistically combined to produce multifunctional composites with enhanced performance.

The data summarized in Figure 15 and Figure 16 demonstrate a dynamic and expanding field characterized by the integration of electrical and chemical approaches. The transition from traditional conductive additives towards reduction-active formulations is coupled with growing thematic diversity, indicating a clear shift in the direction of sustainable and high-performance materials for grounding applications. These findings not only reflect the scientific community’s interest in improving conductivity but also its commitment to developing environmentally responsible and long-lasting solutions for electrical safety and energy infrastructure.

4.2. Trends in the Analysis, Optimization, and Evaluation of GEM

Comprehensive evaluation of GEM has become an essential aspect of GS design and optimization, especially in environments with high resistivity or adverse environmental conditions. The need to ensure the electrical and mechanical stability of these systems has driven the development of more precise methodologies that integrate site characterization, advanced numerical modeling, experimentation, and environmental sustainability.

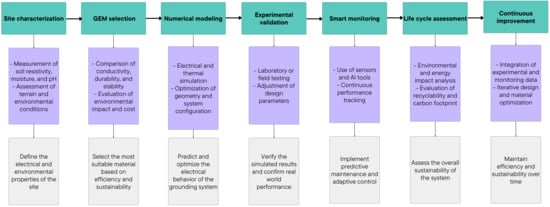

In this context, Figure 17 presents a methodological flow that summarizes the important stages for the selection, validation, and performance evaluation of GEM, incorporating computational simulation tools and intelligent monitoring strategies that allow for the optimization of both the electrical performance of the system and its environmental impact [140,141,142,143].

Figure 17.

Proposed process diagram for the analysis, optimization, and evaluation of GEM used in GS.

The proposed methodological flow integrates a multidimensional approach that combines electrical engineering, materials science, and environmental sustainability. In the initial stages, site characterization and the selection of GEM materials define the physical and chemical basis of the system, ensuring compatibility between the soil and the conductive compound. The inclusion of FEM represents a turning point in the methodology, as it enables the prediction of electrical behavior under different geometric configurations and humidity conditions.

Subsequently, experimental validation and real-time monitoring allow for the adjustment of theoretical models with empirical data, increasing the reliability of the design. This monitoring is complemented by machine learning algorithms, opening up new possibilities around predictive maintenance, resource optimizing, and reduced operating costs.

Finally, the incorporation of Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) and circular economy principles gives the methodology a sustainable character geared towards reducing the environmental footprint and reusing materials. Taken together, this approach ensures a balance between technical efficiency, durability, and sustainability, promoting the adoption of advanced GEM materials as a viable and responsible alternative for modern electrical systems.

4.3. Comparison Table of Review Articles on GEM: Technology Trends

The comparative review presented in Table 11 highlights the distinct approach of this study compared to the existing literature on GEM. While previous studies have primarily focused on individual stabilizing agents or specific chemical, physical, or environmental mechanisms, this review provides a holistic perspective that integrates multiple dimensions, including material characterization, environmental sustainability, and scalability for field application. Several important differences emerge when comparing this study to prior reviews. For instance, early works such as those by traditional GEM researchers focused on chemical stabilizers and calcium-based compounds, whereas more recent studies have shifted attention toward biopolymers, recycled industrial byproducts, and hybrid eco-friendly binders. However, none of these prior reviews have offered a comprehensive synthesis connecting environmental impact, mechanical performance, and large-scale feasibility under a unified framework.

Table 11.

Summary of reviewed works relating to GEM materials and soil stabilization.

The comparative analysis summarized in Table 11 demonstrates a progressive evolution in the field of GEM, moving from conventional chemical additives toward sustainable and bio-derived alternatives. Early studies [144,145,151] concentrated on calcium-based or synthetic polymer stabilizers, emphasizing mechanical strength and soil compatibility. Although these materials achieved well-documented performance improvements, they also presented significant environmental drawbacks, including carbon-intensive production and soil alkalinization effects.

Subsequent investigations [146,147,148] introduced biopolymers and natural organic compounds such as lignin, highlighting their potential as environmentally responsible binders. These studies broadened the focus beyond short-term strength gains to consider durability, biodegradation, and long-term soil–binder interactions. Nevertheless, challenges remained regarding standardization, cost efficiency, and large-scale applicability, due in particular to variability in biopolymer sources and synthesis methods.

More recent comparative works [65,108,149,150] have revealed an increasing interest in hybrid stabilization strategies combining biopolymers, recycled fibers, industrial residues, and nanomaterials. Such integrated approaches aim to balance mechanical performance, environmental impact, and economic viability. Despite promising results, inconsistencies in experimental design and testing conditions across studies still hinder direct comparisons and the formulation of universal performance criteria.