Abstract

Cryogenic technologies are a crucial field of modern engineering, with applications in liquefied gas transport, renewable energy, aerospace, and high-precision medicine. Their advancement relies heavily on the performance and reliability of cryogenic tanks, which ensure the safe storage and handling of fluids at extremely low temperatures. This paper presents a concise review of recent engineering innovations, focusing on fluid behavior in single- and two-phase regimes, boil-off mechanisms, advanced thermal insulation, and energy loss control strategies. Recent numerical and experimental studies indicate that optimized insulation configurations, such as the placement of a low-emissivity intermediate layer near the cold wall, can reduce radiative heat loads by approximately 40–60%, thereby significantly mitigating cryogenic liquid boil-off. Developments in structural materials, functional coatings, and numerical simulations are also discussed, as they contribute to enhancing tank efficiency under demanding operational conditions. Particular emphasis is placed on material selection and surface engineering solutions aimed at reducing corrosion, improving cryogenic resistance, and extending service life. These approaches not only lower maintenance costs but also strengthen safety and sustainability in cryogenic applications. In addition, current industry trends are highlighted, including equipment miniaturization, integration into mobile platforms, and the adoption of international standards for safety and efficiency. The paper aims to provide an interdisciplinary synthesis that supports both academic research and the development of durable, high-performance cryogenic systems.

1. Introduction

Liquefied gases and their associated technologies have become an indispensable component in multiple engineering fields, particularly where extreme temperatures provide functional advantages that are difficult to match [1]. These fluids, including liquid nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, and helium, are characterized by complex thermodynamic behavior involving properties such as high thermal conductivity, elevated specific heat capacity, and controlled volatility at low pressures [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Their relevance derives not only from their specific physico-chemical properties but also from their adaptability within high-performance engineering systems [4].

The practical use of liquefied gases requires the implementation of sophisticated storage and handling systems, particularly cryogenic tanks optimized both structurally and thermally [5]. These tanks must ensure the stable maintenance of liquids, prevent boil-off losses, and guarantee material compatibility under repeated thermal cycling [7]. In this regard, material selection becomes essential, focusing on resistance to embrittlement, corrosion, and thermal shock criteria that go beyond simple mechanical strength [8,9].

Over the past few decades, applied cryogenics research has led to major progress in the use of special alloys, composite materials, and functional coatings that enhance the performance of cryogenic systems [10,11]. Significant advances have been made in thermal insulation systems, such as multilayer insulation (MLI) and partial vacuum structures, which minimize parasitic heat fluxes [12]. These solutions extend cryogen hold time in applications such as maritime or aerospace transport, reducing the need for frequent refilling [13].

In parallel with material development, numerical analysis and fluid-dynamic modeling have provided new insights into the behavior of liquefied gases under single-phase and two-phase regimes [11]. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models enable the prediction of flow instabilities, boil-off phenomena, and risks associated with localized heat losses or cavitation effects [14]. The integration of such models into engineering design has allowed geometric optimization of tanks and direct correlation with functional performance under dynamic operating conditions [15].

Industrial and commercial applications of these technologies are expanding rapidly. In the energy sector, for example, cryogenic tanks are used for storing liquid hydrogen as a clean energy vector, directly supporting global decarbonization objectives [16]. In the food industry, liquid nitrogen is essential for rapid freezing and preservation of sensitive products, while in advanced medicine, liquid helium is critical for cooling superconducting magnets in devices such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems [4].

Another emerging direction involves mobile and space applications, where cryogenic systems are integrated into transport platforms exposed to mechanical shocks, vibrations, and pressure variations [17]. In these contexts, component reliability becomes critical, requiring functional surface coatings of tank interiors to reduce chemical interactions and impurity migration [18].

Given this multidisciplinary complexity, the present article aims to provide an integrative analysis of recent innovations in liquefied gases and cryogenic tanks, emphasizing the interactions between material performance, fluid behavior at the engineering scale, modern analysis methods, and emerging industrial applications. Through this approach, the study seeks to deliver a comprehensive synthesis to support researchers, engineers, and decision-makers in optimizing and sustainably implementing liquefied gas storage capacity.

In this context, the future of sustainable energy systems is closely linked to the use of liquefied gases—particularly liquid oxygen and hydrogen—as vectors of green energy. Their integration into modern energy infrastructure offers real prospects for reducing carbon emissions and improving the efficiency of energy storage and transport systems.

This paper, therefore, aims to explore this technological evolution through an in-depth analysis of the latest advances in the design, optimization, and application of cryogenic tanks in the transition toward green energy. The focus is placed on the role of liquefied gases in emerging energy paradigms, highlighting the connection between the engineering performance of storage systems and current requirements for sustainability, efficiency, and industrial adaptability.

2. Liquefied Gases and Their Dynamic Behavior

Cryogenic liquids are substances that exist in liquid form at extremely low temperatures, often below 123 K, where their physical-chemical properties differ significantly from those observed at ambient conditions [1]. Within this temperature range, thermodynamic behavior, heat transfer capacity, and interactions with the surrounding environment become critical factors for any engineering application [6]. These fluids are essential in cutting-edge technologies, from the storage and transport of energetic gases such as liquid hydrogen to applications in the food industry, modern medicine, and superconducting computing systems [4]. Their importance derives not only from their unique properties but also from the engineering challenges associated with their safe handling.

Cryogenic liquids also play a significant role in the circular economy, being used in waste-heat recovery and reuse systems, or in advanced preservation processes that reduce food waste [10]. This convergence between technological performance and environmental sustainability highlights the growing need for standardization, engineering optimization, and interdisciplinary research in applied cryogenics. As global energy systems shift toward decarbonization and sustainability, cryogenic liquids—particularly liquid hydrogen—are becoming central pillars in strategies for the storage and transport of clean energy. At the same time, their use involves a complex interplay of heat transfer phenomena, phase dynamics, thermal processing, and material compatibility [7].

A liquid is considered cryogenic when its boiling point falls below 123 K, requiring specialized systems to maintain the liquid phase [2]. The most common cryogenic liquids include: liquid nitrogen (77 K), liquid oxygen (90 K), liquid hydrogen (20 K), and liquid helium (4 K), each with distinct applications depending on their physical properties [1,6].

A comparative overview of frequently used cryogenic liquids shows significant differences in boiling point and reactivity. For instance, liquid oxygen (90 K) is a strong oxidizer, whereas liquid helium is completely inert but has an extremely low heat capacity, making it ideal for cooling superconducting systems [6].

Historically, the use of cryogenic liquids began with laboratory research on gas liquefaction and was later applied to aerospace engineering, particularly through the use of liquid hydrogen and oxygen in rocket propulsion [5]. In recent decades, driven by the energy transition, interest has expanded toward industrial and commercial applications, owing to their potential in renewable energy storage, efficient cooling technologies, and quantum applications [10].

In thermal engineering, it is essential to distinguish between cryogens used for direct cooling and refrigerants employed in closed circuits. The former come into direct contact with the cooled material or medium (e.g., LN2 in food processing), while the latter circulate in compression–expansion systems (e.g., helium for indirect cooling in particle accelerators) [5].

The pressure–temperature relationship is also critical. For example, when the temperature drops below the boiling point without a corresponding pressure reduction, cryogenic liquids may undergo direct vaporization through flash evaporation. Modeling this phase transition is essential for the design of tanks and pipelines, particularly under transient regimes or in cases of vacuum loss [7].

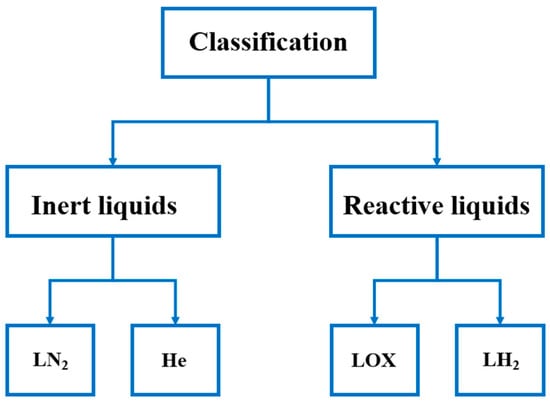

These fluids can also be classified according to several engineering criteria. A primary criterion is their chemical nature: inert liquids, such as nitrogen and helium, do not engage in chemical reactions under normal operating conditions and are therefore employed in processes where stability is crucial (e.g., food cooling, thermal testing systems) [12]. In contrast, reactive liquids, such as liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, are indispensable in controlled combustion applications and propulsion technologies [10]. This classification is explained schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Classification of cryogenic liquids based on their chemical reactivity, distinguishing between inert liquids and reactive liquids.

A second criterion, also explained by means of Table 1, concerns the field of applicability: some liquids are employed in food-related cryogenic processes (liquid nitrogen) [12], others in fundamental research (liquid helium in quantum physics experiments) [4], while liquid hydrogen is widely used in energy storage and transport systems [10]. Classification according to the level of hazard is also essential, particularly in the design of insulation and safety systems [4]. Therefore, comprehensive documentation of each cryogenic liquid, considering reactivity, toxicity, diffusivity, and explosive potential, is a prerequisite for any engineering project [8].

Table 1.

Fields of application of liquefied gases.

A thorough understanding of the nature of these fluids requires a detailed analysis of how they are stored and transported under conditions of safety, efficiency, and sustainability. Accordingly, the following section presents the engineering technologies dedicated to this purpose.

Storage and transport systems for liquefied gases are designed to ensure the maintenance of extremely low temperatures, prevent fluid losses, and mitigate the thermodynamic risks involved [5]. These requirements necessitate the use of cryo-resistant materials and multi-chamber architectures, incorporating multilayer insulation under vacuum or high-performance foams [6].

In the case of liquid hydrogen storage, both experimental and numerical studies indicate that the thermal dynamics of the fluid under static conditions are strongly influenced by tank geometry, insulation thickness, and the presence of thermal bridges [7]. The phenomenon of thermal stratification leads to the formation of warmer regions at the top, promoting evaporation and pressure build-up. To counteract these effects, calibrated safety valves, axially distributed temperature sensors, and passive or active venting systems are employed [7].

Experimentally validated CFD simulations have shown that the introduction of baffles and optimization of the insulation layer distribution can significantly reduce boil-off losses [9]. Furthermore, the structure of the inner tank walls influences vapor bubble formation [1], while the use of low thermal conductivity materials (such as metal–polymer composites) helps maintain stable cryogenic conditions [5].

For food and medical applications, portable containers—pressurized or equipped with cryogenic sprayers—are commonly employed, allowing direct transfer of liquid nitrogen into processing zones. These systems must comply with hygiene and non-toxicity regulations, while accidental contact with exposed components must be prevented through ergonomic design and automated control [12].

Efficient storage of these fluids would be meaningless without a well-defined practical purpose. For this reason, it is equally important to highlight the fields in which cryogenic liquids are industrially and scientifically exploited, contributing to the technological transformation of society.

Liquefied gases have become indispensable components in high-technology industries, where extreme thermal control is critical. In the energy sector, liquid hydrogen is employed as an energy carrier for large-scale transport and storage, offering a viable solution for carbon emission reduction [10]. Recent progress in liquefaction efficiency and in no-vent storage systems enables the implementation of these technologies in commercial applications [7].

In the aerospace industry, liquefied gases are used as primary propellants in rocket propulsion [5]. Liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen form one of the most efficient combinations in terms of specific impulse, being critical for orbital and interplanetary missions [10].

In the food industry, liquid nitrogen is employed for the rapid cryogenic freezing of sensitive products, which preserves cellular structure and organoleptic qualities. This method is highly valued for its fast cooling rate and the absence of chemical contaminants [12].

In scientific research, liquid helium is applied for cooling highly sensitive detectors in particle physics [4], while liquid nitrogen is indispensable in molecular biology laboratories for sample preservation [5].

At the same time, cryogenic applications in the field of electronic memory involve the development of superconducting circuits operating at temperatures of only a few kelvins. These systems provide minimal latency and enhanced energy efficiency in quantum computing platforms or ultra-low-power data centers [4].

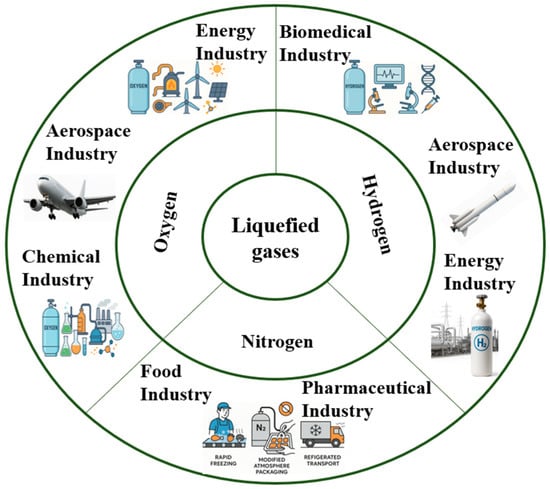

Figure 2 illustrates the main industrial sectors in which liquefied gases-namely oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen-are applied, highlighting their roles across energy, aerospace, biomedical, food, chemical, and pharmaceutical industries.

Figure 2.

Overview of major industrial applications of liquefied gases (oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen).

Nevertheless, beyond their remarkable performance, the associated risks must also be considered. A comprehensive analysis requires accounting for safety, operational stability, and the compatibility of the materials involved.

The use of liquefied gases entails multiple technical hazards, ranging from equipment degradation to threats to human health. Extreme temperatures can cause severe frostbite, while direct contact with skin or eyes leads to immediate and deep tissue damage [8]. To prevent such incidents, the mandatory use of personal protective equipment is required, including cryogenic gloves, face shields, and insulating clothing [5]. Another major risk concerns the build-up of internal pressure in closed tanks due to the spontaneous evaporation of the liquid [5]. Without effective pressure-relief valves, the pressure may exceed allowable limits, leading to container cracking or localized explosions [6]. Experimental studies have shown that the rate of pressure increase is highly sensitive to insulation defects and external temperature fluctuations [7].

In the case of liquid hydrogen, the hazard is amplified by its flammability and the high diffusivity of the resulting gas [7]. In confined spaces, the accumulation of hydrogen gas can lead to explosive mixtures, necessitating the implementation of gas sensors, forced ventilation, and optical detection systems [10].

Materials in contact with cryogenic fluids are also susceptible to embrittlement-the phenomenon of low-temperature-induced brittleness-which can compromise the structural integrity of the tank [1]. Tests conducted on metallic alloys have revealed significant reductions in ductility at cryogenic temperatures, underscoring the need for careful selection of structural components [3].

Liquefied gases, due to their extreme sensitivity to temperature and pressure variations, represent a critical field in advanced engineering. These fluids are employed in applications ranging from space propulsion and fuel transport to quantum materials research, particle physics, and emerging ultra-efficient cooling technologies [18]. Because they are maintained at extremely low temperatures-typically below 123 K and sometimes close to 0 K-they exhibit thermodynamic and hydrodynamic behaviors that differ substantially from conventional fluids [19].

From a technological perspective, cryogenics has become indispensable in the development of hydrogen and oxygen liquid propulsion systems (LH2/LOX), where flow dynamics, mixing, and evaporation are strongly interconnected and critically influence overall engine performance [18]. Moreover, phenomena such as boil-off instabilities, cavitation at low pressures, bubble formation, and two-phase flows are almost unavoidable in practical systems, requiring a detailed understanding of their phenomenology [20].

The main flow regimes encountered in cryogenic systems, together with their thermodynamic states, dominant physical phenomena, and engineering implications, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification of cryogenic flow regimes and governing characteristics.

A central aspect of cryogenic dynamics is the local variation in density and viscosity, which can significantly affect flow even under apparently isothermal conditions. These variations are amplified in the presence of external forces—such as inertial accelerations, microgravity [21,22,23], or applied heat gradients—leading to complex instabilities such as thermocapillary effects or thermal stratification [24].

It is important to note that in many cases, liquefied gases do not behave as ideal Newtonian fluids but may display non-Newtonian characteristics or behaviors dependent on thermal history [25], as observed in unstable helium jets or in subcritical–supercritical transition regimes [26]. Consequently, research in this field requires a synthesis of experimental investigation, mathematical modeling [20], and high-fidelity numerical simulations, all necessary for accurately describing the phenomena involved [27].

The flow regimes observed in liquefied gases are influenced by a considerable number of thermodynamic and hydrodynamic factors [20], including system pressure, local temperature, degree of evaporation, and geometric configuration of the installation. The cryogenic nature of these fluids accentuates phase transitions and necessitates careful classification of flow types depending on the phases present and their stability [21].

Single-phase flow occurs when the fluid remains entirely liquid or gaseous throughout the transport process, typically in well-insulated systems where energy losses are minimal, and temperatures are consistently maintained below the saturation point [28]. Under these conditions, classical analysis methods similar to those applied to Newtonian regimes may be used [29]. However, in most practical applications, operating temperatures approach the boiling point, leading to vapor phase formation and thus two-phase flow [20].

The two-phase regime is specific to systems where liquid and vapor coexist, often in unstable equilibrium due to sudden pressure variations or external heat influx [20]. This metastable state generates a series of interfacial phenomena, such as bubble formation, coalescence, and pressure waves, which strongly affect overall flow dynamics [23].

When the fluid is brought to extreme thermodynamic conditions beyond the critical point, a supercritical regime is reached. This state is characterized by the absence of a clear boundary between liquid and vapor phases and by continuous variations of density and other properties, which greatly complicate mathematical modeling and system control [21].

Interestingly, subcritical and supercritical regimes may temporarily coexist within the same system, depending on local conditions [24], especially in configurations with nonuniform heating zones or systems subjected to rapid external perturbations [17]. For example, in aerospace applications, pressure drops during flight can instantly trigger a phase transition that dramatically alters flow behavior [16].

For the efficient design of cryogenic systems, it is essential to accurately identify the predominant flow regime, as this dictates the choice of calculation models, pipe geometry, insulation type, and operating conditions. Misidentification of the regime may lead to cavitation [20], excessive evaporation losses, or mechanical failures caused by overpressure [29].

Given the varied fluid behaviors and engineering challenges associated with flow regimes, the next logical step is to examine in detail the behavior of cryogenic jets. These represent an interface between fluid dynamics and mass and energy transfer, being essential for applications such as fuel injection, controlled atomization, and targeted cooling.

The behavior of jets formed by liquefied gases constitutes a critical area in the analysis of injection, atomization, and advanced cooling systems. These jets, due to the extremely low temperature and the high thermophysical sensitivity of the fluid, are subject to instabilities fundamentally different from those observed in conventional water or hydrocarbon jets [25].

The breakup mechanism of a jet, known as Rayleigh–Plateau instability, applies only under isothermal conditions with constant surface tension [25]. In cryogenic fluids, however, surface tension varies significantly with temperature, while thermal interactions with the surrounding environment induce interfacial vaporization, destabilizing the jet structure from the nucleation zone onward [26].

Experimental studies on liquid helium jets have revealed the occurrence of spontaneous three-dimensional oscillations even in the absence of external forces, indicating the presence of intrinsic self-instability mechanisms. These phenomena are associated in the literature with quantum behaviors of superfluid helium, as well as with local variations in density and enthalpy amplified by heat flux [25].

In applied cryogenic system engineering, jet stability is critical to ensuring efficient mass and energy transfer. In rocket engine combustion chambers, any perturbation of the jet—whether thermal or induced by structural vibrations—may affect fuel mixing quality and, consequently, combustion efficiency [18]. In such cases, fluctuations in the injection flow can lead to acoustic instabilities, where the interaction between pressure and flow rate produces dangerous oscillations in operating conditions [18].

Advanced CFD simulations have highlighted the crucial role of interfacial evaporation, as well as the influence of ambient pressure on jet stability. The models employed must account not only for flow and heat transfer but also for rapid phase change, thermal stratification, and temperature-dependent fluid properties [27].

Thus, the behavior of cryogenic jets cannot be reduced to analogies with conventional liquids [25]. A rigorous approach is required, integrating local thermodynamic effects, variable interfacial properties, and intrinsic dynamic instabilities generated by the unique nature of these fluids [26].

The analysis of instabilities and the dynamics of cryogenic jets highlights the complexity of the physical phenomena that must be understood and controlled in engineering applications. However, in order to anticipate the behavior of these fluids under real-world scenarios, it is essential to employ advanced computational tools. This underscores the importance of numerical modeling and CFD simulations, which provide a rigorous predictive framework for phenomena such as phase transition, interfacial interactions, and dynamic instabilities in cryogenic regimes.

Numerical modeling of the behavior of liquefied gases poses several challenges due to their biphasic nature, the strong variation in physical properties with temperature, and the presence of rapid transitions between states of aggregation. Unlike conventional fluids, the numerical simulation of cryogenic flows cannot neglect any of the transport processes involved, whether thermal, mass, or momentum transfer [20].

One of the most widely used methods for describing the behavior of such fluids is the volume of fluid (VOF) technique, in which the interface between liquid and vapor phases is explicitly tracked within a three-dimensional computational grid. This approach is efficient in simulating vaporization processes, bubble formation, and the development of unstable jets, but it requires advanced numerical stabilization schemes to handle interfacial discontinuities [27].

For systems in which phases coexist in interpenetrating volumes without a clearly defined interface, Euler–Euler models are preferred. These treat each phase as a continuous fluid, interacting through coupling terms of mass, momentum, and energy exchange [20]. Such models are useful for analyzing homogeneous two-phase regimes, such as boil-off in storage tanks or flow through pressurized cryogenic pipelines [24].

Particular attention must be paid to the definition of thermophysical properties in simulations. Key parameters such as density, viscosity, thermal conductivity, and specific heat cannot be assumed constant but must be expressed through nonlinear functions or experimental datasets for each cryogenic fluid [20]. Any error in interpolating these data can severely affect simulation accuracy.

For specialized regimes, such as those involving superfluid helium jets or nanoparticle-doped cryogenic droplets, classical CFD approaches become insufficient [25]. In these cases, alternative techniques such as Lattice Boltzmann or Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) are employed. These particle-oriented methods provide a discrete description capable of capturing interfacial phenomena, condensation, and the propagation of perturbations with high resolution [26].

Based on these numerical modeling approaches, the main computational methods used for simulating cryogenic flows, together with their suitable regimes, key capabilities, and limitations, are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Numerical methods for specialized cryogenic flow regimes.

Another critical aspect is the treatment of boundary conditions, especially when simulations target systems in microgravity or under thermal cycling. In such contexts, numerical approaches require adaptive boundary conditions and perturbation-sensitive discretization schemes to capture the onset of instabilities, thermal stratification, or oscillatory regimes [27].

Thus, numerical modeling of cryogenic flows requires a balance between the physical fidelity of the models, the numerical robustness of the solution methods, and continuous validation against high-precision experimental data [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Once the fundamentals of numerical modeling are established, it becomes crucial to analyze in depth the mechanisms of heat transfer, as these directly govern fluid stability, vaporization rates, and the overall efficiency of cryogenic systems. In this context, the phenomenon of boil-off is not merely an energy loss but also a sensitive indicator of overall thermal performance, which is why it is treated as a central engineering issue in the design and optimization of cryogenic installations.

Within cryogenic systems, heat transfer mechanisms are directly responsible for the onset and evolution of the boil-off phenomenon—the process by which part of the stored liquid vaporizes uncontrollably due to thermal influx from the external environment [18]. Since liquefied gases possess a high latent heat of vaporization, even a low heat flux can lead to significant mass losses, affecting both system efficiency and operational stability [19].

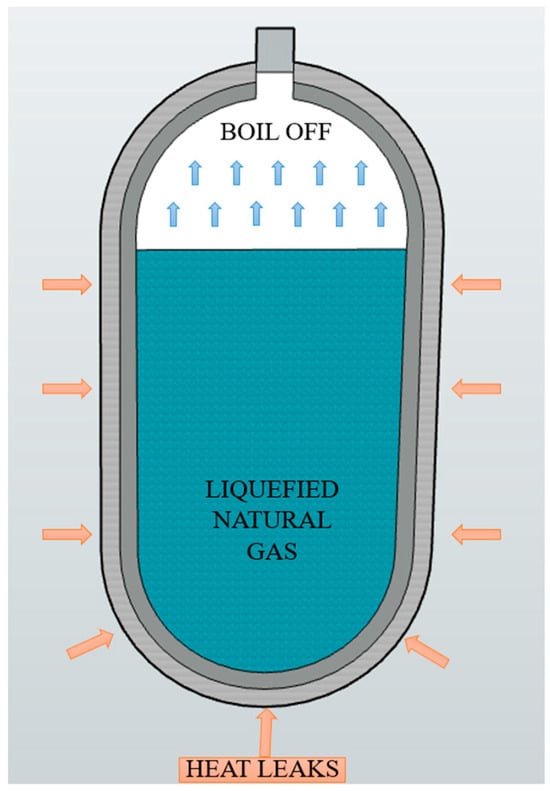

The physical mechanisms governing heat transfer and the resulting boil-off process in cryogenic storage systems are schematically illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the boil-off phenomenon in a cryogenic liquefied natural gas (LNG) tank.

In passively insulated regimes, heat losses occur mainly through thermal radiation and conduction across structural points such as mechanical supports or joints. This thermal energy flux induces a vapor layer in the upper region of the tank, where thermal stratification develops and a saturation front forms between the liquid and vapor phases. In the absence of active control, this layer evolves progressively, increasing internal pressure and forcing the system to vent vapor—a highly undesirable process for long-duration applications [24].

In stratified cryogenic storage tanks, internal thermal non-uniformities may evolve toward unstable configurations, leading to sudden mixing between liquid layers of different temperatures, commonly referred to as rollover events. Such transient instabilities can induce a sharp escalation in evaporative losses, with the boil-off gas generation rate increasing by more than an order of magnitude compared to nominal operating conditions. Reported observations indicate peak boil-off levels reaching approximately ten to twenty times the steady-state rate, underscoring the pronounced sensitivity of cryogenic systems to internal heat redistribution and highlighting the importance of effective thermal control strategies [30].

To reduce such losses, several engineering solutions have been developed, including multilayer insulation (MLI), the introduction of radiation shields, and the active use of cryogenic condensers, which extract generated vapor and reliquefy it under a mass-conserving regime [19]. The Zero Boil-Off (ZBO) technology, applied in NASA missions, combines active cooling, pressure control, and recondensation to completely eliminate vapor losses during long-term storage [25].

At the microscopic level, the boil-off process is governed by heat transfer mechanisms at the liquid–vapor interface. Studies have shown that non-uniform heat distribution along the tank wall leads to localized regions of intense vaporization, which can generate unstable bubbles and accelerate fluid losses [22]. Furthermore, nucleate or convective instabilities may appear when thermal gradients are not uniformly controlled, particularly in complex geometrical configurations.

An additional challenge arises from the non-uniform behavior of fluids under microgravity, where natural convection is diminished, and heat transport depends largely on conduction within the liquid layer and on vapor redistribution through oscillatory motions induced by vibrations or external perturbations [17].

To effectively understand and control these processes, experimental research is complemented by advanced simulations of temperature fields and heat flux, which allow for the identification of critical zones within the system. These simulations must account for both two-phase modeling and the effects of thermal expansion and density variation [19].

Thus, in any engineering application involving the storage or handling of liquefied gases, thermal system design becomes a determining factor, as it directly defines the boil-off rate and, consequently, the operational lifetime and overall safety of the installation. Cooling and thermal management techniques applied in cryogenic tanks reflect a combination of thermodynamic principles, structural innovations, and active control methods aimed at ensuring long-term system stability under diverse operating conditions.

The cooling process in cryogenic tanks exhibits distinct characteristics compared to pipelines, being influenced by the three-dimensional configuration of the closed space, filling conditions, and thermomechanical interactions between the fluid and structural walls. This complexity justifies the need for dedicated studies that separately address the thermal behavior of these systems. For example, Wang et al. [31] implemented two finite-difference schemes to characterize the filling performance of a liquid hydrogen (LH2) tank. Similarly, Leclair and Majumdar [32] developed a numerical model capable of simultaneously simulating the cooling and fueling of LOX and LH2, successfully estimating the thermal stabilization time of the tank.

Thermal dynamics modeling has also been extended to LNG (liquefied natural gas) applications, where Lu et al. [33] proposed a CFD approach to evaluate the thermodynamic response of a transport tank, with emphasis on improving prediction reliability. In parallel, Hedayat and colleagues [34] developed an advanced model combining heat transfer and hydrodynamics to describe cryogenic behavior during filling and cooling of an LH2 tank, demonstrating a precise correlation between liquid level and internal pressure.

During cooling, the progressive accumulation of cryogenic liquid induces a rapid decrease in tank wall temperature, resulting in steep thermal gradients and, consequently, the development of thermal stresses in the structural material. This problem has attracted significant attention in the literature. For instance, Fedorov and Luk′yanova [35] emphasized that filling strategy can influence temperature distribution and stress levels, observing that top-filling reduces thermal stresses significantly. Cheng et al. [36] derived analytical formulas to estimate mechanical stresses in cylindrical walls under cryogenic cooling, reporting circumferential stresses that may exceed 50% of the tensile strength of the material.

From a numerical modeling perspective, Zhu et al. [37] applied finite element analysis to evaluate transient stress behavior in tank walls, highlighting the influence of insulation configuration. Sassine and colleagues [38] adopted a discrete element approach, capturing the time evolution of internal stresses with high accuracy. Ma et al. [39,40] complemented this picture through simulations of a small-scale tank, demonstrating a clear relationship between cooling rate and structural deformation intensity.

Experimental validation of these models was provided by Zhu and colleagues [41], who analyzed the behavior of a 100 L aluminum tank during liquid nitrogen filling.

Results indicated an increase in thermal stresses proportional to filling rate, suggesting a higher risk of structural overload under rapid dynamic conditions [41,42].

Despite significant advances in simulation and testing, notable gaps remain in the detailed understanding of the phenomenology associated with cryogenic tank cooling. Most studies focus on temperature distribution analysis, often neglecting the impact of thermal stress on structural durability. Therefore, the study of stress distribution during cooling phases becomes a critical priority in the development of reliable and safe cryogenic systems [43].

The applicability of cooling and thermal management techniques extends beyond theoretical or experimental aspects, being integrated into numerous functional engineering systems. These solutions are embedded in complex structures optimized for cutting-edge domains such as space propulsion, cryogenic fuel transport, and research facilities. Accordingly, an overview of how these fluids are practically utilized in advanced, interdisciplinary cryogenic systems is essential.

Liquefied gases are widely employed across a variety of advanced engineering systems, particularly in the aerospace, energy, and applied research sectors. Their exceptional thermophysical characteristics—such as high density, elevated latent heat of vaporization, and storage capacity at extremely low temperatures—make them indispensable in applications where efficient energy transfer or propulsion is required [28].

In space propulsion, cryogenic applications primarily involve the use of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen in high-performance injection and combustion systems. These impose stringent requirements for flow control, fuel atomization, and stability under highly variable pressure and temperature regimes [18]. Cryogenic injection systems must ensure stable flow and uniform distribution while avoiding cavitation phenomena and parasitic vaporization losses [28].

In this context, direct cryogenic injection systems have been developed, where mixture dynamics play a critical role in combustion processes [11]. Controlling operational parameters of such systems, including injection frequency, nozzle geometry, and synchronization between liquid and gaseous phases, require advanced numerical modeling and experimental validation [18].

Another category of applications is represented by the transport and storage of cryogenic fuels in isolated or space environments. In such cases, components such as pipelines, pumps, and tanks are designed to minimize boil-off, withstand pressure variations, and prevent the onset of instability or thermally induced mechanical stress [25]. Cryogenic pipelines, for instance, must be analyzed not only for mechanical resistance but also for thermal compatibility with the working fluid, in order to avoid differential expansion and potential cracking [29].

Applications extend beyond aerospace. In scientific research facilities, liquefied gases are used to achieve ultra-low temperatures required in the study of superconducting materials, Bose–Einstein condensates, or cooling systems for particle accelerators. In these applications, controlled heat distribution and thermal uniformity are essential conditions for experimental stability [28].

The development of cryogenic components requires the integration of multiple engineering disciplines—thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, materials science, and automated control [11]. All of these must be harmonized to achieve a functional, safe, and long-term efficient system, regardless of the complexity of the operational environment [24].

The main application domains of liquefied gases, together with their specific uses and associated engineering challenges, are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Application domains of liquefied gases and associated engineering challenges.

Although cryogenic applications have made remarkable progress in recent decades, the complexity of these systems and the extreme conditions under which they operate continue to pose significant challenges. Current limitations in measurement, modeling, and control of dynamic phenomena highlight the need for advanced research and the development of innovative technological solutions.

The dynamics of liquefied gases remains a highly active research field, where the complexity of thermohydraulic phenomena and the limitations of experimental instrumentation create substantial difficulties in fully understanding the behavior of these fluids [20]. Their biphasic nature, rapid transitions between aggregation states, and strong dependence of physical properties on thermal and pressure parameters lead to instabilities that are difficult to predict and control in real applications [21].

One of the central issues lies in the realistic numerical modeling of these phenomena. Although CFD methods have evolved considerably—particularly through the use of adaptive algorithms and multiphase simulation techniques—the accuracy of simulations remains constrained by the lack of precise experimental data under extreme conditions [20]. This limitation is even more pronounced for supercritical liquids or in microgravity environments, where behaviors become fortuitously oscillatory or chaotic [21].

Experimentally, real-time measurements inside active cryogenic systems remain highly restricted. Extreme temperatures reduce sensor reliability, while ice or vapor condensation on optical components hinders the use of conventional visualization techniques [24]. Current efforts focus on developing advanced optical methods and next-generation cryogenic sensors capable of operating stably under unstable and two-phase regimes [25].

Another critical aspect is thermal stratification, which can significantly affect pressure distribution and vaporization rates in storage tanks [23]. Without efficient mixing or liquid recirculation systems, such stratifications lead to temperature inhomogeneities that compromise overall system performance and may induce spontaneous oscillatory behaviors [24].

Recent research also targets the integration of liquefied gases into hybrid systems, such as those combining conventional propulsion with renewable technologies, where cryogenic fluids are used both for cooling and as dense energy storage media [20]. These applications require the development of predictive control models that account not only for instantaneous parameters but also for the thermal history of the system [25].

An emerging field is nano-cryogenics, where liquids are confined at nanometric scales or used in cryogenic colloidal suspensions. At this scale, size effects become dominant, and unconventional behaviors such as self-organization, localized superconductivity, or quantum fluid dynamics open new avenues for both fundamental and applied research [25].

3. Materials Used in the Construction of Cryogenic Tanks

3.1. Cryogenic Tanks

Cryogenic tanks are specialized devices for the storage and handling of fluids at extremely low temperatures, required to maintain the liquefied state of substances such as hydrogen, nitrogen, or oxygen. In industrial and aerospace contexts, they play a crucial role in alternative energy infrastructure, particularly in the storage of liquid hydrogen for aviation applications [44]. The integration of these systems into vehicles involves significant engineering challenges, both at the level of structural design and thermal performance [45].

From a thermodynamic perspective, liquefied gases are frequently operated below the critical point, requiring strict control of temperature and pressure to prevent vaporization losses (boil-off) [46]. For example, liquid hydrogen must be maintained at approximately 20 K under atmospheric pressure, and any deviation can result in significant mass losses [47].

The evolution of technological requirements, especially in low-emission aviation, has driven the optimization of tanks for aeronautical use, where weight, volumetric efficiency, and thermal performance are critical factors [48]. In this context, structural design must ensure resistance to mechanical loads, compatibility with the materials employed, and high thermal performance [1].

A direct comparison between spherical and cylindrical cryogenic tanks highlights important engineering trade-offs that are critical for system safety and efficiency. Due to their radial symmetry, spherical tanks provide a highly uniform stress distribution under internal pressure, which minimizes stress concentrations and enhances structural safety at cryogenic temperatures [44]. In addition, the spherical geometry minimizes the surface-to-volume ratio, thereby reducing heat ingress through conduction and radiation and improving thermal efficiency [44,45,46,47,48]. These characteristics make spherical tanks particularly suitable for large-capacity stationary storage applications, where thermal stability and safety margins are prioritized. However, spherical tanks require complex fabrication processes, higher material consumption, and increased construction costs, which limit their practical implementation in cost-sensitive or space-constrained systems [48].

Cylindrical cryogenic tanks, by contrast, are easier to manufacture and integrate into rectangular or modular layouts, offering greater flexibility for terrestrial, maritime, and transportable applications [47]. Their simpler geometry facilitates installation in both horizontal and vertical configurations and supports efficient integration into host systems [46]. Nevertheless, cylindrical tanks are more susceptible to localized stress concentrations, particularly at end caps, welded joints, and support interfaces, which necessitate careful structural reinforcement and inspection under cryogenic loading conditions [49,50,51,52,53,54]. Consequently, the selection between spherical and cylindrical cryogenic tank designs represents an engineering compromise between structural safety, thermal performance, fabrication complexity, cost efficiency, and application-specific operational requirements [44].

Moreover, in applications such as space launchers, stratospheric balloons, or cryogenic cooling facilities, tanks are subjected to conditions of vibration, thermal cycling, and pressure variations, which impose stringent reliability requirements [54]. Modern systems integrate advanced insulation technologies, pressure and temperature monitoring sensors, as well as automated control systems to maintain liquid-phase stability [55].

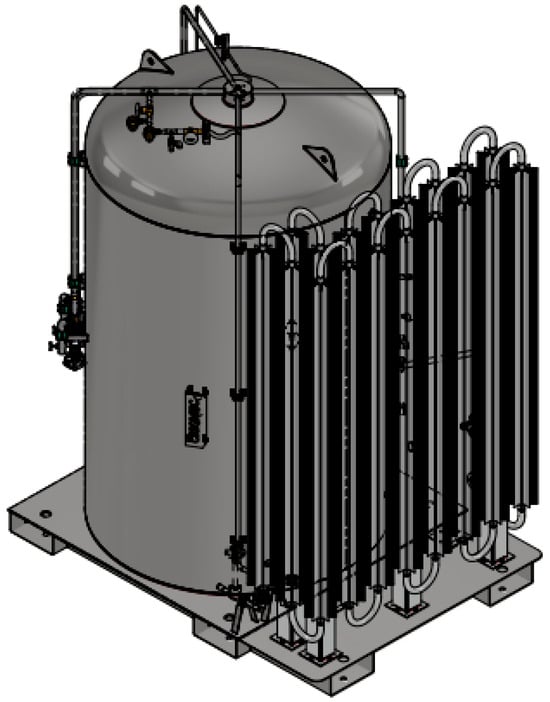

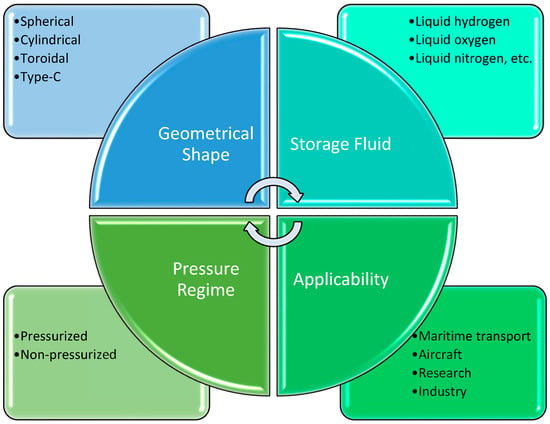

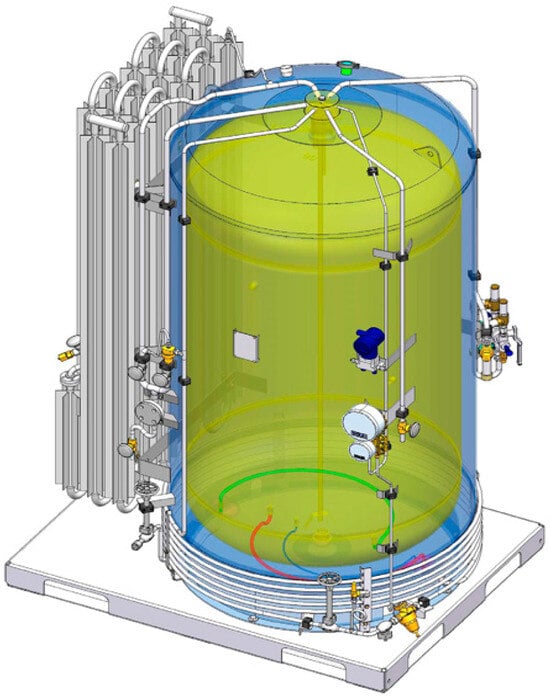

A representation of a cryogenic tank is shown in Figure 4, followed by a summary of the main classification criteria, illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Cryogenic tank of 3000 L.

Figure 5.

Classification criteria for cryogenic tanks.

From the perspective of cryogenic tank types, classification is based on several factors, including geometrical shape, pressure regime, intended application, and the nature of the stored fluid. Each structural configuration addresses specific requirements regarding thermomechanical behavior, insulation efficiency, and adaptability to the host system [44].

One of the most efficient geometrical shapes is the spherical configuration. Due to radial symmetry, spherical tanks distribute mechanical stresses uniformly and minimize the surface area in contact with the external environment, which significantly reduces losses through conduction and radiation [44]. This type is frequently used in the aerospace sector, where low mass and thermal conservation are critical for propulsion system performance [48].

In terrestrial or maritime applications, the cylindrical shape is predominant. Such tanks are easier to manufacture, provide good integration into rectangular spaces, and can be mounted either horizontally or vertically, depending on installation architecture [47].

Pressurized cylindrical variants are often employed in transportable containers or industrial testing equipment, where robustness and simplicity are major advantages [46].

Toroidal configurations also exist, typically used in applications where peripheral space utilization or integration around other equipment is required. While they provide compact geometry, they pose challenges related to temperature distribution and fabrication complexity [48].

A particular case is represented by Type-C tanks, extensively employed in maritime transport of liquid hydrogen. These structures are built from cryogenically compatible materials, capable of withstanding high internal pressures, and equipped with both active and passive insulation systems, in compliance with IMO international standards [43]. Their design is optimized for autonomous operation without continuous venting and for integration into large-scale mobile systems.

Depending on the mode of operation, tanks may be pressurized, where the liquid is maintained above atmospheric pressure to reduce vaporization rates and enable controlled extraction [56]. Alternatively, non-pressurized tanks are used, particularly in laboratory experiments or temporary applications, where boil-off is acceptable or even necessary to maintain constant pressure [49].

The choice of tank type is also closely linked to the nature of the cryogenic fluid. For example, liquid hydrogen requires materials with low diffusivity, capable of resisting embrittlement and limiting atomic permeability [1]. Internal configurations are further adapted to prevent thermal stratification and ensure complete drainage, including under microgravity conditions [50].

Advanced applications, particularly in hydrogen-powered aviation, demand customized configurations such as wing-integrated tanks or modular models designed to optimize the center of gravity and mass distribution [45]. In such cases, aerodynamic, structural, and thermal requirements are combined into a single multifunctional cryogenic structure [57]. Thus, the typology of a cryogenic tank is not merely a geometric choice but an engineering decision that involves balancing multiple parameters: thermal stability, structural safety, usable volume, and compatibility with the target application.

Regarding tank design, structural engineering requires a multidisciplinary approach, where structural mechanics, heat transfer, material compatibility, and operational requirements interact. Structural elements must ensure tank integrity under extremely low temperatures, internal pressure variations, and severe environmental factors, without compromising the overall mass of the system [44].

A fundamental design principle is the functional separation between the load-bearing structure and the insulation layers. In classical configurations, the inner liner is made of metallic or cryogenic composite materials, while the outer shell is designed to withstand mechanical and vibrational loads [45]. This approach allows for optimization of each layer according to its function: mechanical resistance, thermal insulation, or environmental protection [1].

The materials employed must withstand significant thermal contractions without cracking, delamination, or loss of ductility. For example, aluminum alloys and austenitic stainless steels are widely used due to their stable behavior at temperatures below 100 K [46]. In aerospace applications, carbon-fiber-reinforced epoxy composites are increasingly employed to reduce tank mass while maintaining mechanical performance [48].

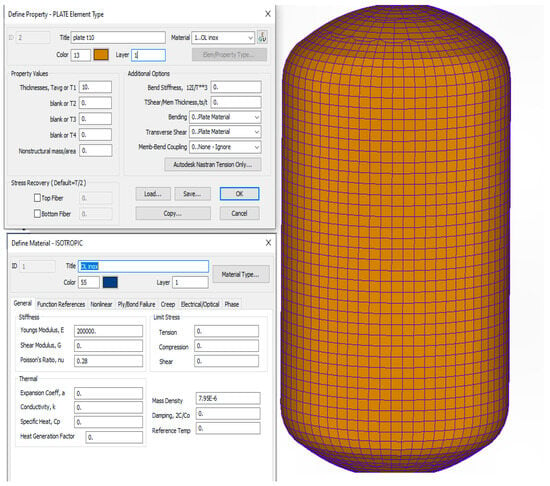

A finite element–based representation of a cryogenic tank geometry, including the definition of material properties for structural analysis, is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Finite element (FEM) geometric model of a cryogenic tank, including material property definition for structural analysis.

Geometric design must minimize areas of stress concentration and ensure a uniform distribution of loads generated by internal pressure and inertia. Particularly in applications such as launch vehicles or stratospheric balloons, rapid pressure variations and high accelerations can induce significant dynamic stresses [54]. Therefore, bulkheads, stiffening ribs, and cryogenic suspensions are strategically integrated to absorb these loads [49].

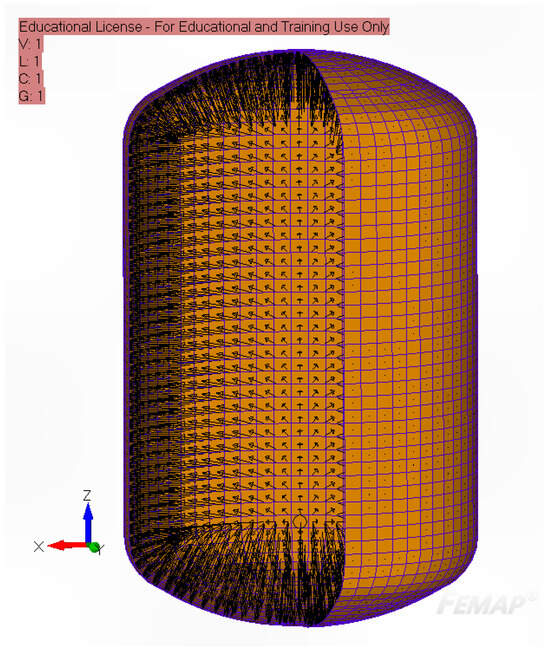

The internal pressure fields resulting from typical operating conditions and structural loading scenarios in cryogenic tanks are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Representative internal pressure distribution within a cryogenic tank under typical operating conditions.

A key challenge in structural design is the integration of the cryogenic tank into the overall system. In aerospace vehicles, integration must account for the center of gravity, fuselage geometry, and the routing of auxiliary systems such as transfer lines, cryogenic valves, and sensors [57]. Recent studies propose the use of adapted shapes, such as elliptical casings or segmented structures, to maximize interior space efficiency and ensure seamless integration with wings or fuselage [45].

Operational pressure is another decisive factor in design. Self-pressurizing tanks require internal reinforcements and safety valves, while passive systems—often employed in fundamental research or high-altitude scientific balloons—must completely minimize boil-off through advanced insulation performance [55].

Numerical modeling plays a central role in structural design. Finite element analysis (FEA) is employed to evaluate stress distributions, cryogenic deformations, and thermal cycling behavior [47]. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations are frequently integrated to assess fluid behavior inside the tank under transient regimes, supporting optimization of the tank geometry and the placement of internal components such as baffles or intake tubes [50].

Efficient integration of a cryogenic tank requires more than geometric compatibility; it must ensure functional interaction with all subsystems, including thermal control, venting, safety, and automation. A successful design must balance these requirements without compromising overall mass, performance, or safety [51].

Beyond structural integrity, thermal insulation, and operational safety, it is also essential to examine the practical implications of these considerations. Understanding how tanks are employed in real-world applications provides the necessary context for evaluating design efficiency and operational performance. Thus, the functional purpose of cryogenic tanks and their utilization across industrial and technological domains underscores the interdependence between practical requirements and adopted engineering solutions.

Cryogenic tanks are essential components in numerous industrial, scientific, and commercial applications, ensuring the safe storage and handling of liquids at very low temperatures, typically below 120 K. They enable the use of liquefied gases such as hydrogen, helium, nitrogen, oxygen, and methane in liquid form, ensuring high energy density and efficient preservation in mass- and volume-sensitive systems [44].

In the maritime sector, Type-C tanks are extensively used for transporting LH2 under high pressure, designed according to IMO codes and optimized to minimize mass losses due to boil-off. They are vital for future hydrogen-powered vessels, serving as both storage and continuous fueling systems for zero-emission propulsion [44]. In this context, thermal performance and structural integrity are critical during long-duration voyages [48].

In aerospace applications, cryogenic tanks are used in rockets employing LOX/LH2 propellants, stratospheric balloons, and scientific instruments requiring ultra-low temperatures. These systems must withstand extreme accelerations, pressure variations, deep vacuum, and rapid thermal cycling [54]. Furthermore, the design must minimize thermal losses without increasing overall mass, necessitating sophisticated insulation and structural integration solutions [55].

In the energy sector, cryogenic tanks are indispensable for the production, transport, and storage of green hydrogen. Within liquid H2 supply chains, they act as buffers between electrolysis and electrochemical conversion in fuel cells, requiring full compatibility with intermittent operation and rapid load/unload cycles [45].

Medical and scientific applications include cryopreservation of biological tissues and operation of imaging equipment (e.g., MRI), where liquid helium is used for cooling superconductors [52]. In such cases, tanks must operate with extremely low boil-off levels, while monitoring systems must allow rapid detection of any losses or malfunctions.

Given the wide range of applications—from liquid hydrogen transport in the maritime sector to aerospace, medical, and energy systems—it becomes clear that tank performance depends not only on geometry and construction materials but also on the ability to minimize thermal losses. In this context, thermal insulation technologies acquire strategic importance, directly influencing energy efficiency, operational safety, and the long-term sustainability of cryogenic systems. Modern insulation solutions analyze the underlying physical principles, materials employed, and selection criteria according to the target application.

Thermal insulation represents a critical factor in the functional efficiency of cryogenic tanks, directly affecting the boil-off rate, structural integrity, and overall operational cost. Technologies are selected according to the application, environmental conditions, and tank geometry [1].

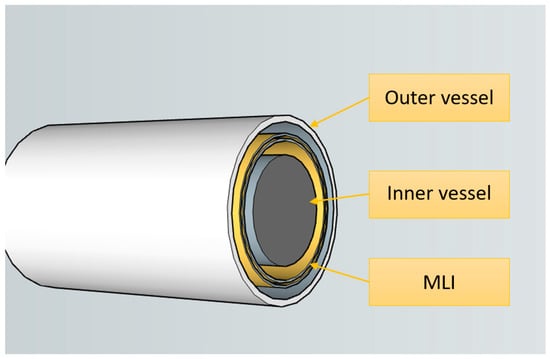

The most effective solution is vacuum insulation combined with multilayer reflective foils (MLI-multilayer insulation). This technology relies on a vacuum space between the inner tank and the outer shell, interspersed with dozens of thin reflective layers, such as aluminum-coated Mylar [53]. This configuration simultaneously reduces all three modes of heat transfer: conduction, convection, and radiation [48].

Experimental results highlight the dominant contribution of heat transfer through the lateral walls of the tank, which, under specific operational configurations, can account for more than 80% of the total heat input to the liquid phase, thereby emphasizing the critical importance of optimizing thermal insulation systems in cryogenic applications [30].

Recent investigations have provided detailed quantitative assessments of multilayer insulation (MLI) systems used in cryogenic tanks, highlighting both their high thermal efficiency under nominal conditions and their limitations under extreme scenarios. Comparative analyses of MLI configurations for liquid hydrogen vessels indicate that these systems exhibit very low density and minimal volume occupation, making them particularly suitable for applications where mass and space constraints are critical, such as transport and aerospace systems [58]. Under high-vacuum operating conditions, optimized MLI layouts can reduce the effective heat flux entering the tank to the order of a few watts per square meter, resulting in boil-off rates typically below 1% per day in liquid hydrogen storage applications [58].

However, recent modeling and safety-oriented studies demonstrate that the thermal performance of MLI systems can deteriorate rapidly when exposed to accidental external fire scenarios. Elevated external temperatures significantly compromise the reflective layers, leading to a sharp increase in heat ingress and accelerated pressurization of the cryogenic vessel [59]. Comparative fire-scenario assessments further show that, for external shell temperatures exceeding approximately 1160 K, severe degradation of the insulation system may occur within tens of minutes, potentially resulting in structural failure regardless of the specific reflective material employed [60]. These findings emphasize that, while MLI systems are highly effective for minimizing heat losses under normal cryogenic operation, their contribution to overall tank safety is strongly dependent on environmental exposure conditions and must therefore be considered in the context of fire-safety regulations and design standards [58,59,60].

From a regulatory perspective, the fire resistance and degradation behavior of thermal insulation systems used in cryogenic tanks must comply with international safety frameworks such as the IMO and the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code, which require insulation and containment systems to limit heat ingress, prevent catastrophic pressure rise, and maintain structural integrity under accidental fire and extreme thermal exposure conditions [44,45,46,47,48].

In commercial and industrial applications, where cost-effectiveness and manufacturability are priorities, porous or composite insulation materials are commonly employed, such as perlite, cryogenic polyurethane foams, or aerogels. These materials exhibit low thermal conductivity but are more sensitive to thermal cycling and may suffer from compaction or vapor absorption [47]. However, rigid foams have the advantage of being easily applied to complex geometries and can simultaneously serve as a protective mechanical layer.

The structural arrangement of the vacuum insulation chamber separating the inner and outer shells of a cryogenic tank is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The vacuum insulation chamber between the inner and outer shells of the cryogenic tank.

In advanced systems, insulation is optimized using CFD and heat transfer models to evaluate real-time behavior. For example, simulations demonstrate how layer thickness, tank geometry, and MLI orientation significantly influence overall performance [52]. Furthermore, the composition of residual gas in the evacuated space affects convective transfer and must be carefully controlled [52].

An emerging trend is the integration of active insulation, where sensors and piezoelectric or thermoelectric cooling elements locally adjust temperatures in critical regions of the tank. Although still experimental, these technologies show strong potential for space and defense applications [55].

The correct selection of the insulation system is a decisive factor for overall performance, safety, and durability, requiring a comprehensive assessment of the operating environment, pressure regimes, and duty cycles.

Safe operation of cryogenic tanks demands the integration of highly precise monitoring and control systems capable of functioning reliably under severe temperature and pressure conditions. These systems ensure real-time supervision of critical parameters and help prevent hazardous phenomena such as overpressure, localized boiling, or massive fluid losses [51].

Temperature sensors are typically fabricated from semiconductor materials suitable for operation below 77 K, such as doped silicon, germanium, or calibrated thermoelectric alloys. They are positioned strategically near the tank bottom, at the liquid level, and in venting regions [52]. Measured values are fed into a data acquisition (DAQ) system that runs adaptive control algorithms to stabilize internal conditions.

Control systems include safety valves, regulation valves, electromechanical actuators, and programmable logic controllers (PLCs) that automatically manage pressure and temperature. If boil-off exceeds a critical threshold, the systems can either vent vapor in a controlled manner or activate a recirculation mechanism to maintain internal equilibrium [53].

In aeronautical and space applications, control systems are even more sophisticated: sensors communicate through redundant networks, with encrypted telemetry transmissions. Data are processed on-board or ground-side, and corrective actions are executed autonomously. For example, in stratospheric balloon tanks, thermal losses are dynamically corrected by adjusting internal pressure or modifying orientation relative to solar radiation [54].

A particularly critical aspect is liquid-level monitoring, which may be achieved using capacitive or ultrasonic sensors, or through cryogenic-specific methods such as differential density detection. These systems enable accurate estimation of remaining fluid volume and trigger alarms in the event of leaks or uncontrolled evaporation [47].

Integration of all these components into a coherent platform requires electromechanical compatibility, frost protection, redundancy, and shock resistance—especially in mobile or spaceborne applications [45]. New generations of cryogenic tanks already incorporate self-diagnosis, IoT connectivity, and predictive control powered by machine learning.

As the energy transition accelerates, cryogenic tanks are becoming central elements in sustainable mobility systems, space exploration, and large-scale energy storage. Advanced applications require integration into complex architectures with strict demands for weight, safety, durability, and thermal efficiency [45].

In the aeronautical sector, recent research focuses on hydrogen-fueled aircraft. Integrating cryogenic tanks into the fuselage or wings requires balancing volume, stability, mass distribution, and minimizing boil-off [48]. These tanks must be structurally compatible with the aircraft, resistant to vibrations and severe thermal cycles, and geometrically optimized to reduce aerodynamic drag [57].

In space missions, cryogenic tanks are used not only for propulsion (liquid oxygen and hydrogen) but also in satellite thermal control systems and scientific instruments. Stratospheric balloons, such as those employed in SPIDER or TAURUS projects, demand extremely well-insulated tanks capable of functioning without active cooling for weeks at altitudes above 35 km [55]. Under such conditions, passive insulation systems and uniform distribution of the cryogenic load are critical [54].

In fundamental research, cryogenic tanks are indispensable in particle accelerators, cosmic radiation detection chambers, and quantum physics experiments. Cooling components to temperatures close to absolute zero allows for precise control of thermal fluctuations and unprecedented accuracy in measurements [52].

Emerging applications also include hydrogen-based electric propulsion systems for heavy vehicles, industrial drones, and high-speed trains. In these cases, tanks must be modular, shock-resistant, easy to maintain, and compatible with automated refueling systems [47].

With the rapid expansion of cryogenic tank applications—from hydrogen-powered aircraft to high-precision scientific instrumentation and autonomous energy storage systems—the need for a robust regulatory framework ensuring safety, reliability, and technological compatibility has become increasingly evident. Implementation of these systems in critical contexts requires compliance with complex international standards tailored to extreme operating conditions and application-specific requirements.

The safe operation of cryogenic tanks is governed by a robust set of international standards adapted to the specifics of each application. These regulations define detailed requirements for materials, pressure testing, structural design, failure protection, and thermal loss control [44].

In the maritime sector, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) mandates compliance with the IGC Code for the transport of liquefied gases, including liquid hydrogen. This code specifies requirements for wall thickness, insulation type, redundancy of safety systems, and pressure maintenance capabilities in emergency scenarios [44,45,46,47,48].

For terrestrial applications, the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code (Section VIII) defines the conditions for design, testing, and certification of pressure vessels. ISO 21014 regulates methods for assessing thermal losses, while ISO 20421-1 specifies requirements for fixed cryogenic tanks [50].

In aerospace applications, agencies such as NASA, ESA, and ECSS (European Cooperation for Space Standardization) enforce much stricter requirements regarding vibration behavior, thermal tolerances, vacuum material compatibility, and long-term reliability. For instance, insulating materials must be tested for degradation under thermal cycling, UV radiation, and microgravity effects [54].

Recent regulations also integrate sustainability principles, including carbon footprint assessment, component recyclability, and safety in case of failure. Provisions also include material traceability, non-destructive weld testing, and periodic calibration of sensors [53].

The structural integrity and regulatory compliance of cryogenic tanks are further ensured through rigorous inspection and quality-control procedures applied to critical components, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Weld joint between the nozzle and the upper head of an inner pressure vessel, inspected by NDT methods (VT, US).

An important component is the harmonization of international standards to enable the interoperability of equipment across different regions and industries. This facilitates the development of a global liquid hydrogen ecosystem, in which cryogenic tanks play a central role [45].

3.2. Materials Used

Cryogenic tanks play a vital role across numerous industries, ranging from the transport and storage of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to aerospace and medical applications [61]. These vessels must safely handle liquids at extremely low temperatures, such as liquid hydrogen at 20 K, liquid nitrogen at 77 K, or liquid oxygen at 90 K, which imposes exceptional requirements on the materials used in their construction [33]. The correct selection of materials is not only a matter of mechanical strength but also of thermal stability, resistance to corrosion, embrittlement, and durability under severe cyclic conditions [62]. The impact of this selection on the overall tank performance is crucial for operational safety and long-term cost optimization [63,64].

Low temperatures affect not only the intrinsic properties of materials but also the interactions between components of composite structures or between different material layers, leading to residual stresses and potential structural defects [65]. In addition, thermal transfer through the tank walls must be minimized to reduce unwanted evaporation and, consequently, economic losses and safety risks associated with gas accumulation [66]. In this context, composite materials, especially alloyed metals, and high-performance insulators constitute the technological pillars of modern cryogenic tank design [67].

Ensuring the reliable and safe operation of cryogenic tanks under extreme temperature and loading conditions requires the careful selection of constituent materials as a key element of the design process. The physical and mechanical properties of these materials at cryogenic temperatures directly influence structural performance, long-term integrity, and compliance with international standards.

The mechanical properties of materials at cryogenic temperatures are influenced by microstructural changes [64] and by embrittlement phenomena occurring at the atomic and microscopic levels [68]. Most metals exhibit an increase in yield strength and tensile strength as temperature decreases, owing to the reduced mobility of dislocations in the crystalline lattice [68,69]. However, this trend is accompanied by a reduction in ductility and toughness, a phenomenon known as low-temperature embrittlement, which can result in brittle fractures that are hazardous in service [64].

Recent studies have demonstrated that cryogenic embrittlement is not an intrinsic limitation of steels but can be effectively mitigated through advanced microstructural design strategies. Recent experimental advances indicate that cryogenic mechanical performance can be substantially enhanced through microstructural engineering rather than through extensive alloying. Xu et al. reported that a heterostructured low-carbon micro-alloyed steel achieved an impact toughness of approximately 200 J/cm2 at 77 K, which is about 24 times higher than that of conventional coarse-grained steels and nearly three times higher than that of ultrafine-grained microstructures [70]. Instrumented Charpy impact tests further revealed an absorbed energy of 79.5 J at 77 K, confirming the exceptional resistance to crack initiation and propagation under cryogenic conditions. Importantly, these mechanical properties were obtained without significant nickel alloying and were shown to meet performance requirements comparable to those of conventional 9% Ni cryogenic steels, highlighting a cost-effective and sustainable pathway for the development of next-generation cryogenic structural materials [70].

In parallel with microstructural engineering approaches, recent alloy development studies have reported promising cryogenic performance, although these materials are still at an early research stage.

Recent literature highlights alloy design as a highly effective strategy for achieving superior cryogenic performance without relying on heavy nickel alloying. In this regard, Shang et al. (2025) [71] demonstrated that a high-manganese austenitic steel maintains exceptional impact resistance at extremely low temperatures. Charpy impact testing revealed absorbed energy values of approximately 116 J at −196 °C and 80 J at −269 °C, confirming robust fracture resistance at both liquid nitrogen and liquid helium temperatures. The sustained cryogenic toughness was attributed to the activation of complementary deformation mechanisms, including mechanical twinning, stacking fault formation, and ε-martensite transformation, which collectively inhibit crack initiation and propagation. These findings position high-Mn austenitic steels as promising candidates for next-generation cryogenic structures, offering a favorable balance between mechanical performance, alloying efficiency, and industrial scalability [71,72].

Austenitic stainless steels, particularly type 316L, are widely recognized for their ability to retain favorable mechanical properties and high ductility even at cryogenic temperatures, due to the stability of their crystalline structure and the high nickel content that stabilizes the austenitic phase [64]. Experimental tests have demonstrated significant increases in mechanical strength at 77 K, but also a reduced plastic deformation capacity compared to room temperature [64].

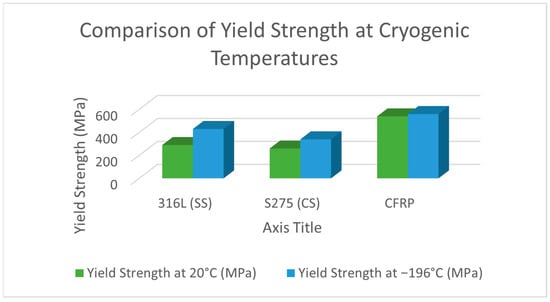

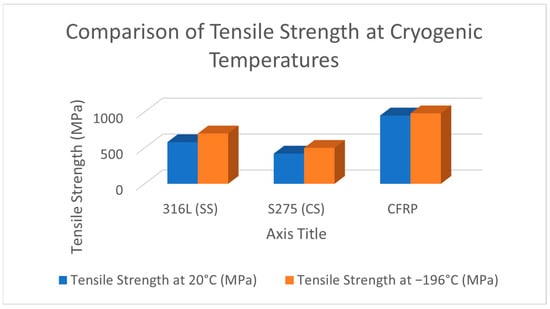

To provide a comparative perspective on the mechanical response of materials commonly used for cryogenic tanks, Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the variation in the yield strength and tensile strength of 316L austenitic stainless steel, S275 structural carbon steel, and carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) at room temperature (20 °C) and cryogenic temperature (−196 °C).

Figure 10.

Comparison of yield strength at room temperature (20 °C) and cryogenic temperature (−196 °C) for selected cryogenic tank materials: 316L (SS) austenitic stainless steel, S275 (CS) structural carbon steel (EN 10025), and carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP).

Figure 11.

Comparison of tensile strength at room temperature (20 °C) and cryogenic temperature (−196 °C) for selected cryogenic tank materials: 316L (SS) austenitic stainless steel, S275 (CS) structural carbon steel (EN 10025), and carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP).

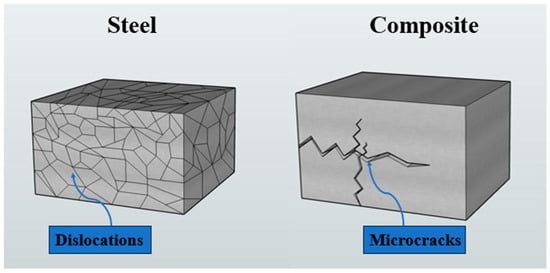

In the case of carbon-fiber-based composites, mechanical resistance at low temperatures is complex, owing to the thermal mismatch between the fibers and the polymer matrix, which can induce internal stresses and microcracks [62]. Recent research indicates that cyanate ester-based matrices exhibit superior performance in terms of cryogenic microcracking resistance compared with conventional epoxy resins [67]. Thus, the polymer matrix represents the critical factor for the durability of composites in cryogenic environments [65].

The structural behavior of materials at cryogenic temperatures must be correlated with their ability to limit heat flux from the surrounding environment. Energy losses through conduction and radiation may compromise the thermal stability of the system, which requires particular attention to the thermal conductivity of materials used in tank construction.

Thermal conductivity constitutes an essential factor in the design of cryogenic tanks, as heat transfer from the ambient environment to the cryogenic liquid leads to evaporation and energy losses [66,73]. Metallic materials generally exhibit relatively high thermal conductivities; for instance, stainless steel 316L has a conductivity of about 16 W/m·K, while carbon steel can reach values of up to 45 W/m·K [64]. This necessitates the use of high-performance insulating materials in combination with the metallic structure [74].

Multilayer insulation (MLI), consisting of multiple layers of reflective foil interleaved with dielectric materials, reduces heat transfer through radiation and conduction to minimal values on the order of a few mW/m·K, making it the standard in high-performance space and cryogenic applications [67,74]. Additionally, evacuated foam insulations and expanded perlite are employed for the thermal protection of tanks and associated components, providing a balance between performance and cost [66].

Low-temperature embrittlement is caused by changes in the crystalline structure [64] and phenomena such as phase transformations, precipitation, and stress concentration in material defects. Carbon steels and low-nickel alloys are more susceptible to embrittlement, which is why austenitic stainless steels or special alloys are preferred in the design of cryogenic tanks [69].

For composites, embrittlement is mainly associated with microcracking of the polymer matrix [62], which compromises the fiber–matrix bond and, implicitly, the overall mechanical strength [65]. Recent studies show that cyanate ester matrices exhibit increased resistance to microcracking compared with epoxies, due to their rigid chemical structure and superior thermal properties [67].

The contrasting deformation and damage mechanisms that govern the cryogenic mechanical behavior of steels and composite materials—namely dislocation activity in metals and microcrack initiation in polymer-matrix composites—are illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Schematic comparison of deformation and damage mechanisms in steel and composite materials, illustrating dislocation activity in steel and microcrack initiation in composite structures under low-temperature conditions.

Beyond their influence on heat transfer, cryogenic temperatures also induce profound structural effects in the materials employed, promoting embrittlement mechanisms that may compromise the mechanical integrity of the system. Cryogenic tanks are exposed to humid environments and may contain impurities that accelerate corrosion processes [64], particularly at welds and material interfaces [69]. Stainless steels provide excellent protection owing to the passive chromium oxide layer formed on their surface, making them the preferred choice in humid cryogenic conditions [64].

Composite materials, due to their organic nature and chemical composition, exhibit higher resistance to chemical corrosion [62], yet the polymer matrix may degrade in the presence of aggressive chemical agents. Consequently, chemical protection and appropriate matrix selection are essential for ensuring long-term durability [66].