Abstract

Free trading of distributed energy resources (DERs) is an effective way to enhance local renewable consumption and user-side economic efficiency. Yet unrestricted sharing may threaten operational security. To address this, this paper proposes a voltage-constrained, differentiated resource-sharing framework for active distribution networks (ADNs). The framework maximizes users’ economic benefits and renewable absorption while keeping system voltages within safe limits. A local energy market with prosumers and the distribution network operator (DNO) is established. Prosumers optimize trading decisions considering transaction costs, wheeling charges, and operational costs. Based on this, a generalized Nash bargaining model is developed with two sub-problems: cost optimization under voltage constraints and payment negotiation. The DNO verifies prosumer decisions to ensure system constraints are satisfied. This paper quantifies prosumer heterogeneity by integrating market participation and voltage regulation contributions, and proposes a differentiated bargaining model to improve fairness and efficiency in DER trading. Finally, an ADMM-based distributed algorithm achieves market clearing under AC power flow constraints. Case studies on modified IEEE 33-bus and 123-bus systems validate the method’s effectiveness, the allocation of benefits between producers and consumers is more equitable, and the costs for highly engaged producers and consumers can be reduced by 46.75%.

1. Introduction

Active distribution networks (ADNs) have emerged as a promising solution for integrating high levels of renewable energy and leveraging flexible demand-side resources [1]. The rapid deployment of photovoltaic (PV) systems has transformed traditional consumers into prosumers, who can potentially contribute to system regulation through market participation [2]. However, existing ADN management approaches face significant limitations in handling this transformation. Traditional centralized control methods struggle to efficiently coordinate the large number of distributed prosumers, often resulting in computational bottlenecks and scalability issues. Moreover, current market mechanisms fail to adequately address the dual challenges of maintaining network operational constraints (particularly voltage limits) while preserving prosumer privacy [3]. These shortcomings not only limit the full utilization of prosumer flexibility but also create barriers to achieving the promised benefits of renewable energy integration and cost reduction in ADNs.

Coordinating local energy resources to address these challenges can significantly boost prosumers’ revenue in the energy market. However, as the number of prosumers grows, the limitations of centralized market trading become apparent, such as restricting trading freedom, limiting income opportunities, and inadequate privacy protection. These issues ultimately hinder the sustainable development of the local energy market. Furthermore, the energy marketing and fiscal regulation of competitive energy efficiency systems play a crucial role in shaping market dynamics, as they establish the regulatory framework that governs prosumer participation and ensures fair competition while promoting system-wide efficiency improvements.

DER trading is an effective way to harness demand-side flexibility and promote local consumption of distributed renewable energy (especially PVs) through energy markets [4,5]. Recent studies have categorized DER trading mechanisms into two types: centralized and decentralized schemes.

Centralized schemes require entities like DER market operators and distribution network operators to manage transactions between market participants [6]. For example, Mediwaththe, C.P. et al. [7] proposed a demand-side management system for neighborhood networks with multiple stakeholders, and Liu, W. et al. [8] suggested a bilateral auction-based methodology for inter-residential energy trading in low-voltage systems. However, centralized methods often face challenges like communication overload [9] and privacy concerns [10] due to their need for extensive global data collection and processing. In contrast, decentralized schemes rely on direct information exchange between parties, using techniques like game theory [11], blockchain [12,13], and ADMM [14]. For instance, Ye et al. [15] developed a DER trading scheme using deep reinforcement learning, while Anoh, K et al. [16] applied a Stackelberg game approach to DER trading in virtual microgrids, considering prosumer load uncertainty. Despite these insights, many studies overlook the physical constraints of distribution networks.

Unlike typical commodities, electricity trading is closely linked to physical networks, requiring consideration of operational constraints in ADNs. For example, Cheng, X. et al. [17] study the energy-sharing problem in a system consisting of several DERs. Feng, C. et al. [18] proposed a DER trading framework that incorporates security constraints using a fast pairwise ascent method. and suggested a real-time hierarchical energy sharing approach for multi-microgrids with building prosumers [19]. To address voltage security, Zhang, K. et al. [20] developed a method for calculating network usage charges based on marginal prices to prevent unsafe transactions. Ullah, M.H. et al. [21] proposed a distributed pricing strategy for DERs, accounting for voltage and line congestion management across various grid topologies. All these studies consider the physical constraints of DER trading, making them practical. However, ensuring fairness and aligning individual interests with social welfare in the DER market remains a key challenge for its success and widespread adoption.

Nash bargaining theory, as a cooperative game, provides an impartial framework for energy transactions, maximizing social welfare while benefiting individual participants [22]. Wu et al. [23] explored bilateral energy trading among prosumers using Nash bargaining, while Wang et al. [24] proposed a hierarchical stochastic dispatch method for ADNs that incorporates flexibility services. Xu et al. [25] used Nash bargaining to model multi-energy interactions between microgrids, decomposing them into subproblems for optimization. Zhong et al. [26] introduced a synergistic energy market model based on generalized Nash bargaining to maximize welfare, accounting for distribution network constraints. While these studies applied Nash bargaining to optimization problems by breaking them into subproblems, they primarily focused on transaction optimization, often overlooking the differing contributions of participants, which could impact fairness in the energy market. Waghmare, S.D. and Hu, Q. et al. [27,28] provided a new pathway for rapid charging in prosumer energy-storage systems.

Table 1 summarizes representative studies on DER trading and highlights the key limitations in the existing literature. As shown in the table, most current works focus on simplified market settings, adopt restricted trading mechanisms, or overlook important practical constraints such as network operation limits and participants’ strategic behaviors. These limitations reveal that, despite substantial progress, the literature has not yet provided a comprehensive framework capable of capturing the complexity of real-world DER trading environments. Motivated by these gaps, this study aims to address the identified shortcomings and develop a more realistic and applicable trading model.

Table 1.

Comparative table of literature.

To address unfair benefit distribution and limited prosumer incentives in active distribution networks, this paper proposes a differentiation-aware, voltage-constrained energy sharing framework based on generalized Nash bargaining theory. Existing methods often ignore prosumers’ varying contributions to energy trading and voltage regulation, leading to suboptimal participation and voltage risks. This framework addresses this gap by quantifying prosumer differentiation, integrating demand-side voltage regulation, and enabling distributed energy resource sharing to enhance renewable energy utilization and system flexibility. By accounting for both market participation and voltage control contributions, it ensures voltage security and fair benefit allocation, thereby incentivizing active prosumer engagement. The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows.

- (1)

- A differentiation-aware and voltage-constrained energy sharing framework is established for ADNs. This framework uniquely integrates demand-side voltage regulation into the trading process, simultaneously ensuring system security constraints are met while maximizing prosumer economics.

- (2)

- A distributed DER sharing model is proposed to coordinate interactions between the DNO and prosumers. By incorporating multi-lateral interactions, this model effectively promotes renewable energy consumption and enhances system flexibility compared to traditional centralized approaches.

- (3)

- A novel quantification mechanism for prosumer differentiation is designed to evaluate contributions to both market participation and voltage control. This mechanism ensures fair benefit distribution and explicitly incentivizes prosumers to provide voltage support, thereby fostering a more active and secure trading market.

2. Problem Statement and Framework Outline

This section details the content framework of the article.

2.1. Problem Statement

With the increasing share of controllable resources in the demand-side of the ADN, a substantial number of prosumers can manage their controllable resources and available PV energy to participate in the electricity market. In this context, it is of great significance to design a suitable local energy market, so that it can fully mobilize the enthusiasm of prosumers to participate in the market, reduce the cost of electricity for prosumers, and effectively improve the consumption of PV. It is imperative to recognize that energy trading in ADNs is contingent upon physical network transmission, necessitating prosumer trading to adhere to stringent network security constraints. Simultaneously, a pertinent market mechanism is essential, ensuring that prosumers possess both the willingness and capacity to actively maintain network security constraints during energy trading. Against this background, this paper focuses on the following issues in prosumers energy trading.

Considering the physical constraints inherent in the distribution network during energy trading, self-interested prosumers, driven primarily by individual cost optimization, may inadvertently compromise the operational security of the physical system through unrestricted trading, which therefore leads to voltage violations and line congestion issues [3]. Consequently, the design of rational energy market mechanisms becomes crucial in motivating prosumers to actively prioritize the physical constraints of the ADNs when optimizing their electricity consumption decisions.

When it comes to balancing the optimization of individual prosumer costs with the consideration of total social welfare in DER trading—if not restricted, prosumers would always overlook the global energy costs and energy economics of the entire cluster when individually optimizing their costs, impacting the overall well-being of the local energy market [29]. Therefore, how to maximize social welfare while concurrently enhancing individual prosumer interests has become a critical issue.

As for enhancing the fairness of the distribution of benefits by fully considering the diversity of prosumers during energy trading, prosumers engaged in DER trading not only seek greater profits than non-participants but also emphasize the fairness of profit distribution [30]. Given the different trading roles played by different prosumers in the ADN and their different contributions to voltage safety, it is critical to consider differentiated bargaining power. Non-differentiated bargaining power affects prosumers’ motivation and efficiency in participating in energy trading and may undermine the overall fairness of the trading process, hindering sustainable development in the local energy market. Therefore, quantifying the bargaining capacity of different prosumers to enhance the energy trading fairness holds particular importance.

2.2. Proposed DVC-DER Framework

Considering the above issues, this paper introduces a differentiation-aware voltage-constrained (DVC) DER trading and sharing framework, which proficiently quantifies the contributions of prosumers in the energy sharing and voltage regulation process, fostering greater equity in overall energy sharing and providing robust support for energy market trading.

The specific elements within the framework are as follows: in the cluster welfare maximization stage (cost optimization stage), the prosumers are first modeled by analyzing the composition of their objective functions. Then prosumers negotiate with each other in a distributed manner to determine the final DERs trading volume. Finally, the DNO checks whether prosumers’ decisions comply with the physical system constraints and guides the voltage-violating prosumers to change their decisions until all prosumers’ decisions satisfy the network constraints. In the payment bargaining stage, according to the energy market participation and voltage regulation proposed in this paper, prosumers obtain differentiated bargaining power and achieve fair benefit distribution.

The practical deployment of the proposed pricing and trading framework relies on an efficient communication infrastructure capable of supporting frequent information exchange between the DNO and prosumers. In modern distribution systems, such functionalities are typically enabled by advanced metering infrastructure (AMI), which provides real-time or near-real-time measurements of energy consumption, local voltage magnitudes, and trading quantities. Leveraging these communication capabilities, the DNO periodically updates nodal price signals and trading limits in accordance.

3. Formulations

This section details the models used in the article: the DNO model, the DER sharing model, and the prosumer differentiation model.

3.1. Local Energy Market

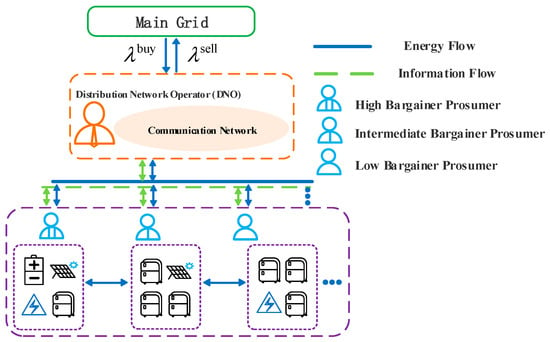

The local energy market outlined in this paper comprises two entities: prosumers and the DNO, as shown in Figure 1. Prosumers take on a central role in local energy market transactions and contribute significantly to maintaining voltage security. Facilitated by modern communication networks and AMI, effective data communication between the DNO and prosumers is ensured [31]. In terms of energy trading: prosumers first maximize the welfare of the cluster through cooperative energy sharing, then differentiate the bargaining power of different prosumers through the differentiation mechanism, and finally negotiate with each other to determine the DER trading price to achieve the reduction in their energy costs. In terms of voltage security: maintain community voltage security by accepting the updated tariff information from the DNO, and proactively changing the electricity consumption strategy. The role of DNO in maintaining community voltage security: DNO calculates node voltage by collecting part of prosumer information, updates the interactive price between prosumers and the main grid according to the node voltage, and encourages prosumers to change their decisions to maintain the voltage security of the whole system. Through this integrated mechanism, the local energy market proposed in this paper effectively enhances the local PV utilization level, reduces prosumer costs, improves the overall economic efficiency of prosumers, and ensures the voltage security of the community distribution network.

Figure 1.

Local energy market.

The specific action process of DNO is as follows:

- (1)

- Calculate the prosumer node voltage

Prosumers upload the sum of their interaction power with the main grid and DER trading volume at period to DNO, and then the DNO calculates the node voltage for each prosumer based on the following model [6].

where and denote the active and reactive power flowing from upstream prosumers to prosumer at period ; and denote the active and reactive power injected by prosumer ; denotes the amount of electricity sold by prosumer to the utility main grid at period ; denotes the amount of electricity that prosumer buys from the utility main grid at period ; denotes the volume of DERs trading between prosumer and prosumer at period ; denotes the set of all prosumers; denotes the square of the voltage at bus at period ; denotes the set of downstream users of prosumer ; denotes the downstream prosumer of prosumer ; and denote the resistance and reactance of the line between prosumer and prosumer .

Since prosumers do not have to upload specific power consumption strategies, their privacy is protected during the entire trading process.

- (2)

- Update the interactive price between prosumers and the main grid

By updating the interactive price between prosumers and the main grid, DNO guides the prosumers who violate the node voltage to change their original strategies until all the consumption strategies of prosumers meet the voltage constraint. DNO updated electricity price rules are as follows:

where is the price regulation coefficient; and represent the purchase price and feed-in tariff of prosumer at period , respectively; and represent the minimum and maximum prices of electricity purchased from the grid, respectively; and and represent minimum and maximum feed-in tariffs, respectively.

When prosumer is overvoltage at period in the -th iteration, the feed-in tariff and purchase price of prosumer at that period are reduced in the ( + 1)-th iteration, and prosumer is guided to transfer the load at other periods to period , increase the electricity load at period , reduce the amount of electricity injected into the main grid, and alleviate the overvoltage violation. On the contrary, in the -th iteration, when prosumer is under voltage at period , the feed-in tariff and purchase price of prosumer at that period are increased in the ()-th iteration, and prosumer is guided to transfer the load at period to other periods, reduce the electricity load at that period, and alleviate the under-voltage violation. If prosumer has no violation during -th iterations, the interaction price between prosumer and the main grid at that period does not change during ( + 1)-th iterations.

3.2. DER Sharing Model

In the local energy market framework, all prosumers are equipped with a proportion of flexible adjustable loads, which can be modified when necessary. However, adjusting these flexible loads incurs inconvenient costs for prosumers. Some prosumers are equipped with energy storage devices, which inevitably cause losses during charging and discharging, and their costs are not negligible. There are costs associated with prosumers’ DER trading with each other and their interactions with the main grid. In addition, prosumers need to pay certain network fees when they conduct DER trading.

The prosumer cost optimization model is as follows:

where denotes the load adjustment inconvenience cost, denotes the degradation cost of energy storage systems, denotes the DERs trading cost, denotes the interaction cost with the main grid, and denotes the grid asset usage fee of prosumer . If < 0, prosumer obtains energy from prosumer , and vice versa, it supplies electricity to prosumer . is the prosumer load adjustment inconvenience factor; is the total load transferred by prosumer throughout the cycle; denotes the set of all time periods; denotes the charging loss coefficients of the energy storage, denotes the discharging loss coefficients of the energy storage, denotes the charging power of the energy storage, denotes the discharging power of the energy storage, denotes the unit price of DERs trading between prosumer and prosumer at period ; and denotes the per unit cost of the grid asset usage due to the electricity trading.

- (1)

- Demand response: All prosumers have a certain proportion of flexible resources, which can be transferred when needed, and the transfer load needs to meet following constraints:where is the ratio of flexible load; and the load transferred by prosumer at period .

- (2)

- Energy storage system: To ensure the normal and safe operation of the energy storage system, energy storage charging and discharging must meet the following constraints:where and represent the maximum charging and discharging power; and represents the charging and discharging efficiency. denotes the maximum state of charge (SoC) allowed for prosumer ; denotes the minimum SoC allowed for prosumer ; denotes the SoC of prosumer at period ; and H denotes the maximum value of the time period set .

- (3)

- Prosumer DER trading: The constraints on prosumer participation in local energy markets for DERs trading are as follows:where is the adjacent prosumer of prosumer ; is the amount of electricity sold by prosumer j at period ; is the amount of electricity purchased by prosumer from his neighbor at period ; and are the maximum allowable electricity purchase and sale quantities for prosumer during time period , respectively; is the total amount of energy traded by prosumer at period , and the corresponding payment to be paid is .

- (4)

- Interaction constraint between prosumers and the main grid: Prosumers are connected to the main grid through the distribution network, and when optimizing their own energy consumption strategies, any excess or insufficient energy needs to be balanced through the main grid.where denotes the net load of prosumer during time period .

3.3. Differentiation Among Prosumers

Considering the different roles of prosumers in trading and their different contributions to maintaining the security of the entire system, it is important to quantify the differentiation among prosumers throughout the energy sharing process for a fair market environment.

The differentiation proposed in this paper is manifested in three aspects: (1) the degree of interactive tariff regulation imposed on prosumers with different levels of voltage violations with the main grid (see subsection III-A for details); (2) the definition of an indicator of energy market participation, which is related to the prosumers’ status as a buyer or seller of electricity as well as to the volume of transactions in the DER trading; and (3) the definition of an indicator of the contribution of regulation, which is related to the number of nodes at which the prosumer regulates the violated voltage.

- (1)

- Energy market participation

Energy market participation is specifically the extent to which prosumers participate in the instinctive energy market to conduct transactions, with different identities and different volumes of DER transactions resulting in each prosumer having a different level of energy market participation.

To capture the heterogeneous participation levels of prosumers in energy sharing, this study adopts a nonlinear logarithmic function to quantify individual market engagement, which reflects strategic interactions and payoff distributions among participants with unequal bargaining powers. Unlike conventional utility or optimization functions, it explicitly incorporates asymmetric bargaining influence, social welfare maximization, fairness, and incentive compatibility while maintaining analytical tractability. The mathematical structure also supports decomposition and distributed solution methods consistent with Nash bargaining theory [32]:

where denotes the amount of electricity bought by prosumer throughout time horizon ; denotes the amount of electricity sold by prosumer throughout time horizon ; denotes the ratio of the amount of electricity bought by prosumer to the amount of bought by all prosumers; denotes the ratio of the amount of electricity sold by prosumer to the amount of sold by all prosumers; and denotes the level of participation in the energy market by prosumer .

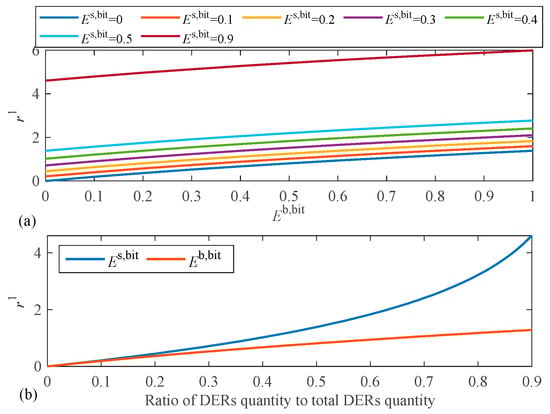

Energy market participation varies with the share of electricity bought by prosumers and the share of electricity sold by prosumers as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the and /. (a) Relationship between and and (b) Energy market participation of new energy buyers and sellers.

The energy market participation of prosumer , as depicted in Figure 2a, exhibits a positive correlation with the proportion of electricity purchases within the total purchases of prosumer cluster and the proportion of electricity sales within the total sales of prosumer cluster. In other words, it increases as both increases. Furthermore, Figure 2b reveals that, at the same proportion, renewable energy sellers demonstrate higher levels of energy market participation compared to renewable energy buyers.

Remark: In Equation (23), the parameter exhibits a sharp increase as approaches 1. However, in real-world energy markets, it is common to have multiple renewable energy sellers, and the value of typically falls outside the range [0.9, 1]. Consequently, the proposed energy market participation approach put forward in this paper remains feasible.

In general, the energy market participation model formulated by Equations (23)–(26) exhibits the following characteristics: (1) all prosumers engaged in energy sharing possess the capability to engage in negotiations; and (2) renewable energy sellers (providers) exhibit a higher level of involvement in the energy market compared to buyers (receivers), indicating their superior bargaining power. Moreover, the amount of energy provided (received) directly influences their bargaining power.

- (2)

- Voltage control contribution

During the voltage regulation process, different prosumers make different contributions to the maintenance of distribution network security. The voltage regulation contribution defines the different contributions of prosumers to the voltage security of the ADN. Similarly to the energy market participation, this paper employs a nonlinear logarithmic function for quantification and calculate the corresponding contribution of prosumers towards pressure regulation using the following model.

where denotes the number of voltage violation nodes regulated by prosumer ; denotes the maximum number of regulated voltage violation nodes among all prosumers; and denotes the voltage regulation contribution of prosumer .

Equation (27) shows that all prosumers have a basic value of voltage regulation contribution 1 (i.e., the voltage regulation contribution of users who do not participate in voltage regulation). Furthermore, prosumers regulating more voltage violation nodes experience a higher voltage regulation contribution and, consequently, an increased bargaining value.

The first aspect of differentiation is implemented in the DER trading and sharing stage, where DNO updates its interaction price with the main grid based on the differentiated voltage situation of prosumers, enabling prosumers to improve voltage violations. The latter two aspects of differentiation are implemented in the bargaining stage, which constitutes the differentiated bargaining value in the bargaining stage.

where denotes the bargaining value of the prosumer in the bargaining stage. Different prosumers have different bargaining values, and differentiated asymmetric bargaining in the bargaining stage makes the whole process fair.

3.4. Generalized Nash Bargaining Problem

The DER trading and sharing problem is decomposed into two sub-problems: the welfare maximization problem of prosumer cluster (P1) and the payment bargaining problem (P2).

P1: The welfare maximization problem of prosumer cluster with voltage constraints.

Equation (21) shows that the mutual settlement prices among prosumers consistently balance out, resulting in a sum of zero. Therefore, the cost associated with DER settlement does not impact the cost of the prosumer cluster and can be disregarded in the solution. The welfare-maximizing model for prosumer clusters is provided below.

P2: Payment bargaining problem based on differentiated bargaining value.

In this paper, the Generalized Nash Bargaining (GNB) theory [33] is adopted in the bargaining stage, and the following prosumer differentiated bargaining model is constructed by combining the differentiated bargaining value , which is composed of the energy market participation and the regulation contribution, as mentioned in the previous section.

where denotes the cost to prosumer when not participating in the cluster energy cooperative sharing; and denotes the cost to prosumer when the cluster welfare is maximized.

4. Solution Implementation and Robustness Analysis

This section details the methods for solving the models proposed in the article.

4.1. Solution Implementation

The objective function of P1 can be decomposed into sub-objective functions for each prosumer. Considering the privacy and communication limitation among prosumers, this paper adopts the ADMM distributed algorithm to solve the optimization problem. ADMM is a compelling method for solving this class of problems. It efficiently handles separable objectives coupled by linear constraints while exhibiting stable and robust numerical behavior. Furthermore, it provides strong privacy-preservation with minimal communication overhead and has empirically demonstrated favorable convergence and scalability. However, due to the presence of multi-coupling in constraint (19) representing the DER trading and sharing constraint, direct application of the ADMM algorithm is not suitable. Therefore, this paper introduces an auxiliary variable to transform the multi-coupling constraint (19) into a double-coupling constraint (32).

where denotes the quantity of electricity that prosumer expects to trade with prosumer . When , it indicates an agreement on electricity transaction between prosumer and prosumer . On this basis, this paper establishes the augmented Lagrangian function for minimizing the cost of prosumers.

where is the Lagrange multiplier; and is the penalty factor.

The ADMM algorithm requires three updates in each iteration to optimize this problem:

S1: Update of Prosumers’ Trading Decisions

S2: Update of Auxiliary Variables

S3: Update of Lagrange Multipliers

The process of updating prosumer electricity consumption decisions is repeated through the three steps mentioned above until the algorithm satisfies the convergence conditions. After the above convergence conditions are satisfied, all prosumers send information about their interactions with the main grid and DERs transactions to the DNO, which updates the prosumers’ differentiated interaction prices with the main grid, and simultaneously, the prosumers adjust their and according to Equations (37) and (38). Then the prosumers perform a new round of iteration to update their consumption decisions, DNO calculates the system node voltages again, and the iteration stops if all the prosumer voltages satisfy the network constraints, otherwise the above process is repeated.

where is the step length of the upper limit change allowed in DER trading; is the maximum electricity sold permitted by prosumer in DER trading at period ; is the upstream neighboring prosumer of prosumer ; and is the maximum electricity bought permitted by prosumer in DER trading from its upstream neighboring prosumers.

The optimization model of P2, i.e., Equation (30), can be equivalently transformed as follows:

Since maintains a balance among prosumers, can be decomposed into the sub-objective function for each prosumer. Prosumers calculate their differentiated bargaining value according to Equations (23)–(28). The processing of multivariate coupling constraint (19) and the update process of P2:

Since the balance is maintained between producers and consumers, it can be decomposed into the sub-objective function of each producer and consumer:

The ADMM algorithm requires three updates in each iteration to optimize this problem:

S1: Update of Prosumers’ Trading Decisions

S2: Update of Auxiliary Variables

S3: Update of Lagrange Multipliers

After updating these quantities, the producers and consumers carry out a new round of iterative updates to their electricity trading decisions. The DNO recalculates the system node voltages. If the voltages of all producers and consumers meet the safety constraints, the iteration stops; otherwise, the process is repeated. Once the iteration stops, the producers and consumers allocate benefits based on their voltage control contributions and determine the order of energy trading. The loop terminates when the price change (the difference in the energy purchase/sell prices between consecutive iterations) is smaller than 0.1%.

4.2. Robustness Analysis

In real-world distribution systems, the assumed network topology and line impedance parameters may deviate from their actual values due to routine switching actions, network reconfiguration, asset aging, and inaccuracies in parameter estimation. Although the analytical formulation adopted in this work presumes accurate and fixed network models, the proposed method exhibits a notable degree of robustness to such modeling uncertainties.

A key factor underpinning this robustness is the feedback-driven iterative structure of the pricing and operational updates. The DNO adjusts nodal prices by observing the actual voltage magnitudes at the buses, which inherently encapsulate the true—albeit imperfectly known—system characteristics. Therefore, even if the assumed impedances or connectivity deviate moderately from the physical network, the price-update mechanism responds to empirical voltage deviations rather than relying strictly on the modeled sensitivities. This closed-loop correction enables the algorithm to progressively guide the system toward operationally admissible states and to maintain convergence properties under a broad range of parameter perturbations.

5. Numerical Simulation and Discussion

This section details the parameter settings used in the simulation and partial result analysis.

5.1. Simulation Setups

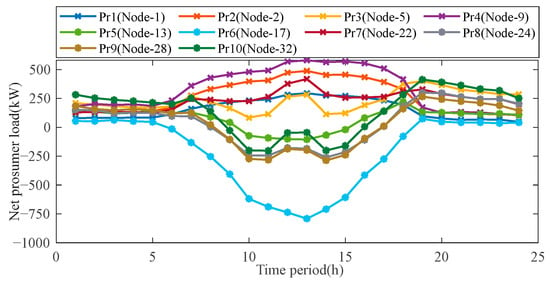

The effectiveness of this paper’s proposed method is validated through case studies conducted on modified IEEE 33-bus test system with 10 prosumers, each potentially equipped with PV or energy storage and their net load curves are shown in Figure 3. The nominal distribution voltage is 12.66 kV, and the feasible busbar voltage range is 1 ± 5% p.u. Further details about these periods can be referenced in [6]. More specific parameters are shown in Table 2. All simulations were implemented in MATLAB 2021b with YALMIP and the commercial solver Mosek optimization toolbox, and required approximately 9000 s on a workstation equipped with an Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-8700 processor (3.2 GHz).

Figure 3.

Net prosumer load curve.

Table 2.

Parameter table.

To verify the effectiveness of the method in this paper, a comparative study was conducted with three other cases:

Case 1: A baseline scenario without DER trading (No DERs).

Case 2: An ADMM-based distributed optimization for DER trading that neglects network constraints (DERs w/o considering network constraints) [26].

Case 3: An ADMM-based scheme integrating DER trading and voltage regulation with a standard Nash bargaining solution (i.e., equal bargaining powers for all prosumers, DERs w/o DVC).

Case 4: The ADMM-based DVC-DERs scheme proposed in this paper.

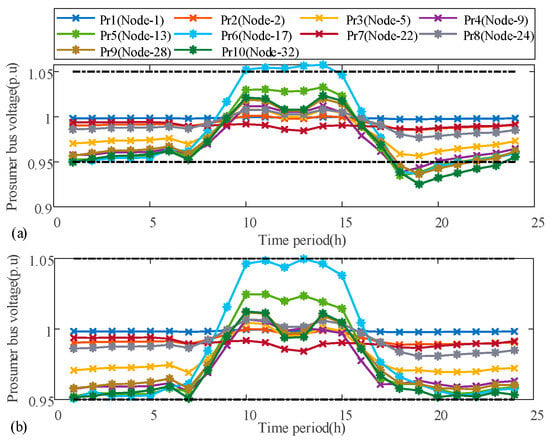

5.2. DER Trading Management

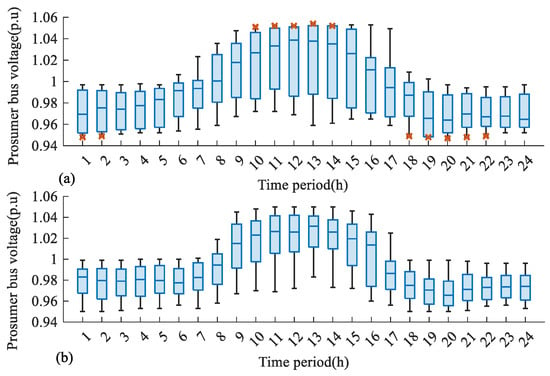

The voltage profiles of the 10 prosumers in Case 2 and Case 3/Case 4 are shown in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively. In Case 2 (Figure 4a), prosumer 6 experiences overvoltage at multiple instances during the second period, reaching up to 1.06 p.u. at its worst moment. In the third period, multiple prosumers encounter undervoltage, with prosumer 10 experiencing the most severe under voltage, approaching 0.92 p.u. at its worst moment. Upon implementing the proposed voltage regulation scheme for each prosumer in Case 3/Case 4 (Figure 4b), all prosumers’ voltages are maintained between 0.95 and 1.05 p.u., which demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed voltage regulation scheme in alleviating voltage violations.

Figure 4.

Voltage profiles of 10 prosumers. (a) Bus voltage before regulation (Case 2), (b) bus voltage after regulation (Case 3/Case 4).

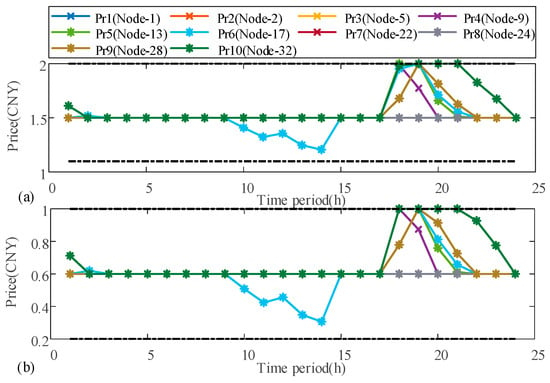

Figure 5 illustrates the interaction price between prosumers and the main grid after voltage regulation (i.e., Case 3 and Case 4), which highlights that the interaction price between prosumers and the main grid undergoes changes when prosumers violate voltage constraints. Consider the price changes for prosumer 6 in the second period and prosumer 10 in the third period as examples. In the second period, when prosumer 6 experiences overvoltage, both the feed-in tariff and the purchasing price of power from the main grid decrease. This encourages prosumer 6 to increase the load consumption, consume more PV at the time of overvoltage, and reduce the amount of power injected into the main grid, thereby alleviating the overvoltage. Similarly, in the third period, when prosumer 10 faces undervoltage, both the feed-in tariff and the purchasing price of power from the main grid rise. This encourages prosumer 10 to reduce electricity load consumption at the time of undervoltage, thus alleviating its violation of under voltage.

Figure 5.

Interaction price. (a) Buying prices from the main grid, (b) selling prices to the main grid.

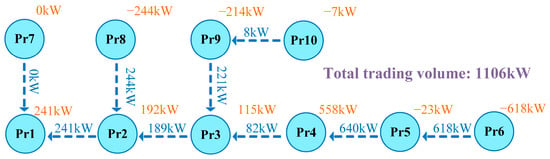

The detailed DER trading volume for each prosumer at 11:00 a.m. is illustrated in Figure 6, and Figure 7 and shows that after optimization, both prosumer 6 and prosumer 10 transfer the load of period 1 and period 3 to period 2. This optimization allows them to reduce their electricity costs by taking advantage of abundant photovoltaic resources in the energy market during this period through DER energy sharing. Additionally, from the perspective of voltage regulation, DNO updates the interaction price between prosumer 6 and prosumer 10 at the period of violation with the main grid. Prosumers adjust their load by reducing it during periods of undervoltage and increasing it during periods of overvoltage. This optimization of the power consumption strategy not only reduces electricity costs but also effectively alleviates voltage violations, ensuring the voltage security of the distribution network.

Figure 6.

DER trading at 11:00 a.m.

Figure 7.

Optimization strategy of prosumer. (a) Energy optimization results for prosumer 6, (b) Energy optimization results for prosumer 10.

5.3. Differentiation-Aware Voltage Control Scheme

Table 3 presents the differentiated bargaining value of the 10 prosumers, which indicates that prosumers engaging in more DER trading exhibit higher participation in the energy market, with those providing renewable energy having greater participation than those accepting renewable energy. Additionally, the greater the number of illegal voltage nodes regulated by the prosumer, the more significant its contribution to the entire node system, resulting in a greater bargaining value.

Table 3.

Prosumer differentiated bargaining value.

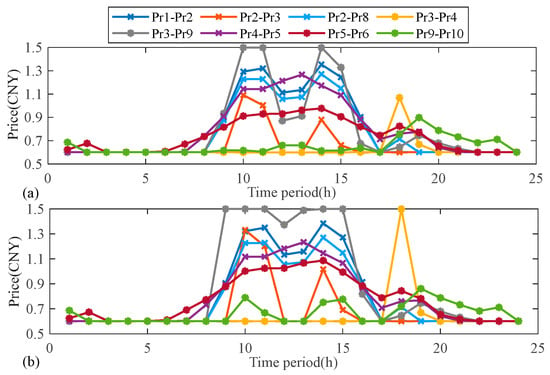

Figure 8 illustrates the bargaining results of prosumers, indicating that all bargaining outcomes fall between the feed-in tariff and the purchase price. Taking the bargaining curves between prosumers 5–6 and prosumers 3–9 as examples, the two price curves in Figure 8b are higher than the price curves in Figure 8a. This difference is attributed to the higher differentiated bargaining value of prosumer 6/9 compared to prosumer 5/3, giving it a dominant position in the bargaining process. As a seller, prosumer 6/9 raises the DER trading price to maximize its income. The utilization of differentiated bargaining power effectively distinguishes prosumers’ contributions to the local energy market, ensuring a more equitable distribution of benefits and motivating active participation in the local energy market and voltage security maintenance in ADNs.

Figure 8.

Bargaining results. (a) Price of DERs w/o DVC, (b) price of DVC-DERs.

Regarding prosumer electricity costs, compared to Case 1, all prosumers participating in DER trading in Case 2 achieved cost reductions or revenue increases (except Prosumer 7 who did not participate). Prosumer 5 achieved the highest benefit with a 46.75% cost reduction, while prosumer 10 had the smallest reduction of 2.83%. Compared to Case 2, prosumers in Case 3 experienced marginal cost increases due to participating in voltage regulation, as they sacrifice individual benefits for network security. Compared to Case 3, Case 4’s differentiated bargaining mechanism further reduces costs for prosumers with significant contributions to DERs trading and voltage security (those with higher bargaining powers). This demonstrates that the proposed differentiated voltage compensation scheme in Case 4 ensures fair benefit allocation, promoting market fairness and sustainability.

5.4. Impact Analyses of Voltage Regulating Factor and DER Transaction Cap Cutting Step Length

In practice, prosumers are sensitive to the interactive price of the main grid and the upper limit of DER transaction allowed in energy sharing. In order to verify the convergence performance of the proposed method, sensitivity analysis is conducted on the voltage regulation coefficient and the step size of DER transaction upper limit reduction in this part.

The results are shown in Table 4, where the number of iterations for the prosumers decreases as γ becomes larger, but the number of iterations starts to increase when γ > 35. This is because if γ is too large or too small, it needs to be externally regulated more times before the prosumers’ interaction tariff with the main grid reaches an appropriate value. The results show that when γ is set properly, the voltage quality of the prosumer cluster is improved, and the algorithm has a better convergence performance.

Table 4.

Comparison of voltage regulating factor γ convergence performance ( = 60).

As shown in Table 5, the iteration times of the algorithm decrease as increases, because the larger the power reduction step, the faster the DER transaction ceiling of the prosumer is cut, and the more obvious the change in user strategy. However, when is too large, the change in user DER transaction ceiling is too large, which may lead to excessive user behavior and failure to approach the convergence value. The results show that the local energy market consumption rate can be up to 100% with appropriate settings, while the algorithm has good convergence performance.

Table 5.

Comparison of DER transaction cap reduction step performance (γ = 10).

5.5. Algorithm Evaluation

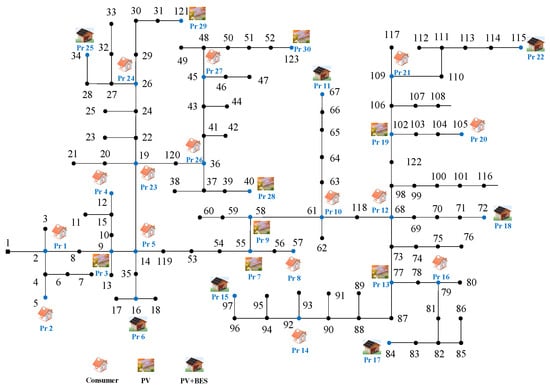

This subsection verifies the scalability of the proposed DVC-DER method on the modified IEEE 123-bus test system [34] with 30 prosumers, which is shown in Figure 9. Simulation tests were conducted with γ = 10 and = 60. Through simulation tests, the proposed scheme required 38 outer loop iterations (internal iterations totaled 2861). Compared with the previous 10-prosumer case, the number of iterations did increase to some extent, but it was still within the acceptable range. Therefore, the scalability of the proposed method in terms of computational efficiency is proved.

Figure 9.

The modified IEEE 123-bus test system.

The voltage magnitude distribution between DER cases with and w/o DVC is comprised in Figure 10. Compared with Figure 10a, the voltage of prosumers after DVC-DER regulation is within the safe range, and the voltage of most nodes is not close to the critical value (0.95 p.u and 1.05 p.u). It can be concluded that the voltage distribution of prosumer cluster has been effectively optimized after the DVC-DER regulation.

Figure 10.

Voltage magnitude distributions for 30 prosumers under (a) DERs w/o DVC (The red cross indicates that there is a voltage overlimit condition) and (b) DVC-DERs.

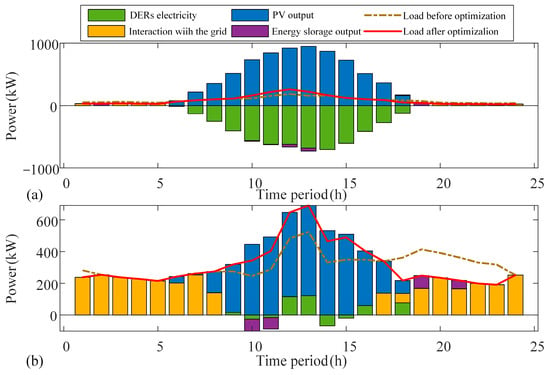

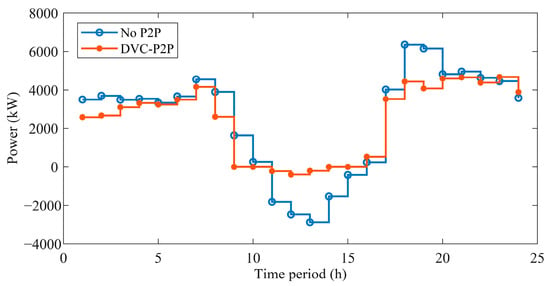

Figure 11 illustrates that in the absence of energy sharing, prosumers can only achieve power balance through the main grid. In comparison, with the implementation of energy sharing, there is a significant reduction in the level of energy interaction between prosumers and the main grid. In certain periods, the entire prosumer cluster can even achieve self-sufficiency. This highlights the positive impact of energy sharing on enhancing the local renewable energy absorption rate and reducing dependence on the main grid.

Figure 11.

Net load of prosumers under two cases: no DERs and DVC-DERs.

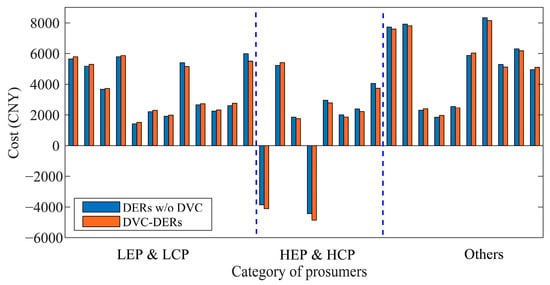

To effectively demonstrate the impact of the proposed DVC-DER method on prosumer costs, all prosumers are classified into the following categories. Prosumers with a ratio of buying and selling electricity to the maximum buying and selling electricity greater than or equal to 0.5 are categorized as high energy market participation (HEP), while those with a ratio less than 0.5 are classified as low energy market participation (LEP). Furthermore, prosumers with the number of regulating node voltage greater than or equal to 4 are designated as high voltage regulating contribution participants (HCP), whereas those with a number less than 4 are identified as low voltage regulating contribution participants (LCP). The cost comparison with and w/o DVC-DERs in different categories of prosumers is shown in Figure 12, from which it can be revealed that, compared to the scenario without the DVC-DERs scheme, the higher the market participation of prosumers, the more the number of regulated voltages, the more costs will be reduced, and vice versa. This demonstrates the positive impact of the proposed DVC-DER scheme in maintaining fairness in the overall energy market transaction and fostering sustainable development in the energy market.

Figure 12.

Daily cost comparison with and w/o DVC-DERs in different categories of prosumers.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a DVC-DER trading method that accounts for the differentiated contributions of prosumers while ensuring voltage regulation. Based on Nash bargaining theory, the trading problem is decomposed into a cluster welfare maximization and a bargaining payment subproblem. The ADMM algorithm enables iterative negotiation among prosumers, while the DNO verifies decision feasibility and updates the grid interaction price until voltage constraints are satisfied. A differentiation mechanism is then introduced to quantify each prosumer’s contribution to voltage security, enabling a fair and efficient benefit allocation through asymmetric pricing. Simulation results on modified IEEE 33-bus and 123-bus systems verify that the proposed method enhances economic efficiency and fairness. Highly engaged prosumers reduce costs by up to 46.75%, with an additional 9% saving over the non-differentiated scheme. All voltages stay within 0.95–1.05 p.u., PV utilization reaches 100%, and rewards are allocated fairly according to voltage-support contributions. Experimental results show that the proposed framework enables prosumers to gain higher benefits than non-participation while satisfying network constraints and achieving more equitable benefit distribution.

While this paper differentiated pricing mechanism, demonstrating how recognizing heterogeneous prosumer contributions can enhance market efficiency and integrate voltage security constraints, several limitations remain. The assumptions of perfect information sharing and day-ahead market focus may oversimplify strategic behaviors and overlook real-time uncertainties, with ADMM scalability to large networks remaining unexplored. Future work should address renewable uncertainties through robust optimization, extend to multi-timescale markets, and develop privacy-preserving and machine learning-accelerated solutions. Practical implementation requires regulatory frameworks enabling technical contribution-based differentiated pricing, standardized prosumer-DNO communication protocols, and incentive mechanisms rewarding both energy provision and grid support services, facilitating the transition toward active, resilient distribution networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. and M.P.; methodology, J.Z.; software, C.Z.; validation, W.L., M.P. and J.Z.; formal analysis, W.L.; investigation, M.W.; resources, L.S.; data curation, W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, W.L.; project administration, M.P.; funding acquisition, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Company (B3120524003 K).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

If needed, The authors can provide the data required for the research.

Conflicts of Interest

Author M.P. and J.Z. were employed by State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DERs | distributed energy resources |

| ADNs | active distribution networks |

| DNO | distribution network operator |

| ADMM | Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers |

| PV | photovoltaic |

References

- Chang, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, H.; Wu, Q. Privacy-preserving distributed energy transaction in active distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 3413–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, J. Virtual prosumers’ P2P transaction-based distribution network expansion planning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 1044–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, A.; Khorasany, M.; Gooi, H.B. Decentralized local energy trading in microgrids with voltage management. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Gao, J.; Jiang, X.; Fu, K.; Wen, F. A new double-market parallel trading mechanism for competitive electricity markets. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanis, Z.; Durusu, A.; Altintas, N. A Comprehensive Review on Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading: Market Structure, Operational Layers, Energy Cooperatives and Multi-energy Systems. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, C.; Paudel, A.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Gooi, H.B.; Zhu, J. Fully decentralized P2P energy trading in active distribution networks with voltage regulation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 14, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediwaththe, C.P.; Shaw, M.; Halgamuge, S.; Smith, D.B.; Scott, P. An incentive-compatible energy trading framework for neighborhood area networks with shared energy storage. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 11, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Qi, D.; Wen, F. Intraday residential demand response scheme based on peer-to-peer energy trading. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 16, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liao, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhang, L.; Lin, J.; Chen, M.; Guerrero, J.M.; Abbott, D. Parallel and distributed optimization method with constraint decomposition for energy management of microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 4627–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, H.A.; Srivastava, A.K.; Eldosouky, A. Blockchain-based privacy preserving and energy saving mechanism for electricity prosumers. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgioioso, G.; Ananduta, W.; Grammatico, S.; Ocampo-Martinez, C. Operationally-safe peer-to-peer energy trading in distribution grids: A game-theoretic market-clearing mechanism. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 2897–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.P.; Thakur, A.K.; Singh, S.P. Blockchain based energy trading in ADN with its probable impact on aggregated load profile, available distribution capability and loadability margin. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2023, 17, 2853–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Gu, N.; Wu, C. Blockchain enabled data transmission for energy imbalance market. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminlou, A.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Zare, K.; Razzaghi, R.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Peer-to-peer decentralized energy trading in industrial town considering central shared energy storage using alternating direction method of multipliers algorithm. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 2579–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.-P.; Strbac, G. A scalable privacy-preserving multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach for large-scale peer-to-peer transactive energy trading. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5185–5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoh, K.; Maharjan, S.; Ikpehai, A.; Zhang, Y.; Adebisi, B. Energy peer-to-peer trading in virtual microgrids in smart grids: A game-theoretic approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Tsetis, I.; Maghsudi, S. Distributed Management of Fluctuating Energy Resources in Dynamic Networked Systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Liang, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Wen, F. Peer-to-peer energy trading under network constraints based on generalized fast dual ascent. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Liang, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Wen, F. Data-driven energy sharing for multi-microgrids with building prosumers: A hybrid learning approach. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e12821. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Troitzsch, S.; Hanif, S.; Hamacher, T. Coordinated market design for peer-to-peer energy trade and ancillary services in distribution grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 2929–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.H.; Park, J.-D. Peer-to-peer energy trading in transactive markets considering physical network constraints. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3390–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Feng, X.; Nguyen, H.D. Peer-to-peer transactive energy trading of a reconfigurable multi-energy network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 2236–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Gu, W.; Zhou, S.; Yang, X. Decentralized game-based robustly planning scheme for distribution network and microgrids considering bilateral energy trading. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Hierarchical Optimal Dispatch of Active Distribution Networks Considering Flexibility Auxiliary Service of Multi-Community Integrated Energy Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 2770–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, B.; Liu, N.; Wu, Q.; Voropai, N.; Li, C.; Barakhtenko, E. Peer-to-peer multienergy and communication resource trading for interconnected microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 2522–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Xie, S.; Xie, K.; Yang, Q.; Xie, L. Cooperative P2P energy trading in active distribution networks: An MILP-based nash bargaining solution. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, S.D.; Phulwale, S.P.; Gaikwad, A.M.; Thosar, A.S.; Bobade, R.G.; Ambare, R.C.; Thonge, P.N.; Dhas, S.D. Tungsten-doped bismuth ferrite nanoparticle electrodes for energy storage application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhas, S.D.; Mendhe, A.C.; Thonge, P.N.; Patil, A.M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D. A high-performance battery–supercapacitor hybrid device and electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction based on NiCo2−xMnxO4@Ni-MOF ternary metal oxide core–shell structures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 21956–21970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Chi, M.; Liu, Z.-W. A pricing game strategy with virtual prosumer guidance in community grid. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2023, 17, 2701–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, W.; Ma, K.; Li, C. A three-stage multi-energy trading strategy based on P2P trading mode. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Wen, J.; Cheng, S. Enabling online scheduling for multi-microgrid systems: An event-triggered approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 1836–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Wang, Y.-W.; Liu, X.-K.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.-W. Economic Storage Sharing Framework: Asymmetric Bargaining-Based Energy Cooperation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 7489–7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Ni, M. Day-ahead operation strategy for multiple data centre prosumers: A cooperative game approach. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, Z.; Wen, J.; Ding, L.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, S. Network-constrained transactive control for multi-microgrids-based distribution networks with soft open points. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 1769–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).