1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents a growing public health challenge worldwide, with a substantial increase in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) cases requiring dialysis care. In Thailand alone, there are more than 80,000 patients receiving hemodialysis, distributed across over 2500 dialysis centers nationwide [

1]. These centers are responsible for collecting and reporting large volumes of clinical and administrative data to government agencies. However, due to strict cybersecurity and privacy policies, there are no interoperable application programming interfaces (APIs) to enable automated data exchange between dialysis centers and national health information systems. Consequently, nurses and administrative staff must manually enter the same data into multiple government platforms, including two web-based portals and one legacy desktop application. This repetitive work leads to inefficiencies, delays, and a heightened risk of human errors, diverting clinical staff from direct patient care and contributing to burnout [

2,

3].

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) has emerged as a promising solution for automating rule-based workflows in healthcare, such as billing, claims management, and patient scheduling. However, conventional RPA solutions are often brittle and fail when user interfaces (UIs) are modified, particularly in heterogeneous environments where web and desktop systems must be integrated [

4,

5,

6]. Recent studies emphasize the need for integrating RPA with advanced artificial intelligence to create intelligent automation frameworks that can adapt dynamically while keeping governance and sustainability considerations in view [

7,

8,

9]. This integration is particularly relevant in nephrology, where high-frequency dialysis sessions generate repetitive documentation tasks requiring rapid, accurate data transfer between systems [

10].

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), particularly large language models (LLMs), introduces new capabilities that extend beyond deterministic automation. In healthcare contexts, LLMs have been applied to tasks such as clinical note generation, anomaly detection, and semantic validation, demonstrating the potential to enhance the quality and efficiency of information workflows [

11]. When embedded within RPA systems, GenAI can provide context-aware reasoning, automatic text generation for free-text fields, and self-healing UI adaptation, allowing bots to continue functioning even when interfaces evolve [

12]. Furthermore, the inclusion of human-in-the-loop (HITL) mechanisms ensures that automation enhances safety and accountability, especially in high-stakes environments such as dialysis care [

13,

14,

15].

Traditional RDA systems, while effective for automating repetitive desktop tasks, exhibit several critical limitations in complex healthcare environments. First, they depend on static, locator-based scripts and fixed UI element identifiers, which makes them brittle when layouts or element IDs change after routine software updates—especially in web-based applications that are updated frequently [

4,

6]. Second, because traditional RDA operates without semantic understanding or contextual validation, bots may mimic user actions yet fail to detect cross-system inconsistencies or invalid entries, thereby propagating input errors [

9]. Third, conventional RDA deployments are often tied to single workstations and tightly coupled desktop environments, limiting scalability and interoperability in hospitals that combine on-premise applications with secure cloud portals; these constraints are well-recognized in governance and internal-control discussions of RPA [

8]. Collectively, these technical and operational weaknesses constrain their long-term sustainability and hinder widespread adoption in mission-critical settings such as dialysis care.

This study addresses the remaining bottleneck of manual multi-system data entry. We propose a Generative AI-enhanced Robotic Desktop Automation framework designed to autonomously navigate two web-based and one desktop-based government system, perform accurate and efficient data entry, and adapt dynamically to UI changes. This research project, supported by research funding from the National Research Council of Thailand, seeks to develop and evaluate a prototype for using RDA to streamline data entry processes in nephrology centers across approximately 2500 clinics in Thailand. The objectives of this study are threefold: (1) to design and implement an improved RDA framework for multi-system nephrology data workflows; (2) to evaluate its performance in terms of automation accuracy, time efficiency, error prevention, usability, and resilience to interface changes; and (3) to assess its potential to reduce clerical workload and improve user satisfaction in real-world dialysis center operations. By combining deterministic automation with adaptive generative intelligence and HITL oversight, this framework aims to advance Thailand’s digital health transformation while respecting existing governance and security constraints.

3. System Implementation

3.1. System Architecture and Framework Design

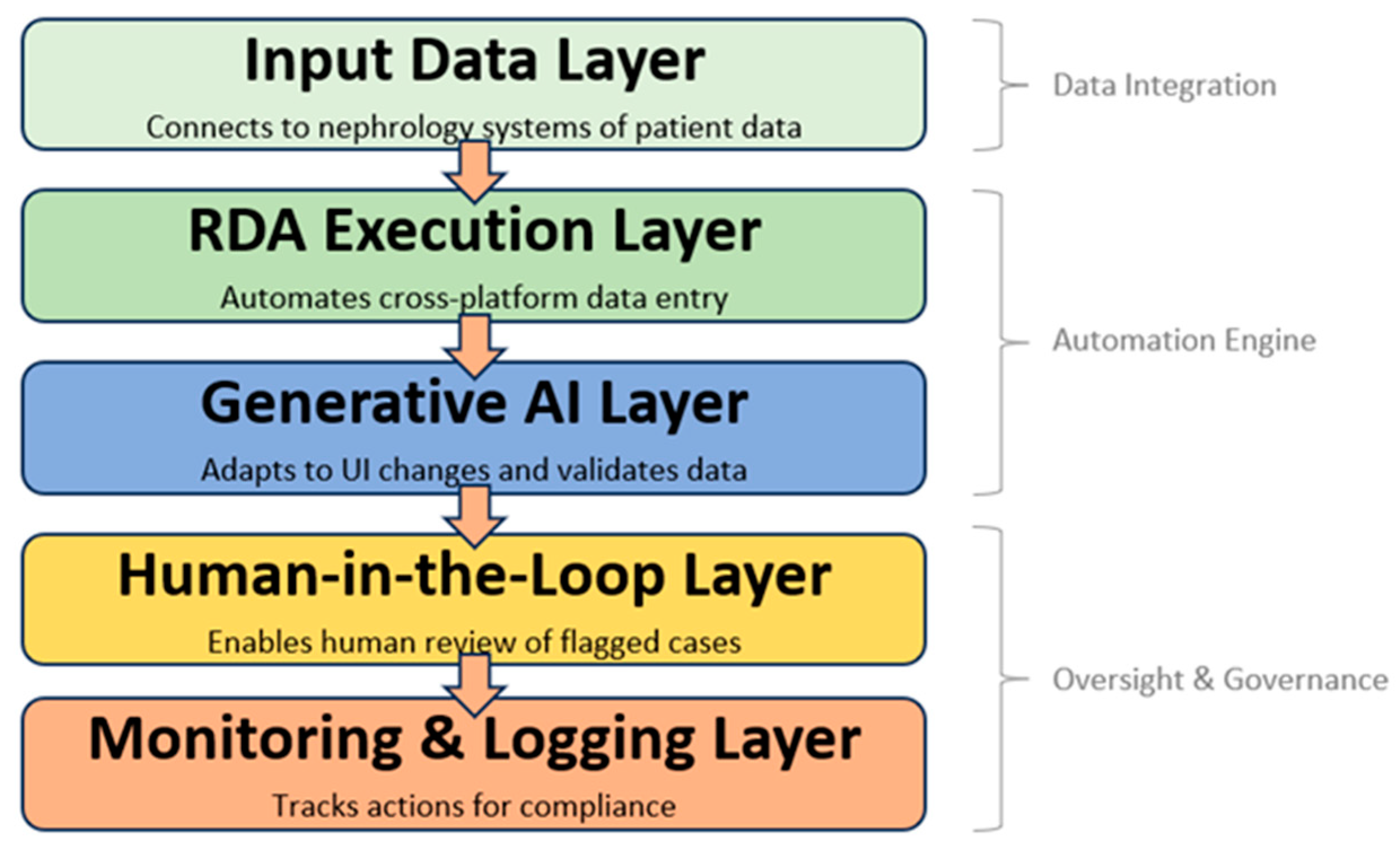

The proposed system architecture, illustrated in

Figure 1, was designed to address the persistent challenge of manual, repetitive, and error-prone data entry across multiple government nephrology platforms. The framework is conceptualized as a layered model that integrates deterministic automation with adaptive generative intelligence and human oversight, thereby ensuring both efficiency and resilience. At its foundation, the Input Data Layer enables secure connectivity with nephrology information sources, including hospital information systems and third-party dialysis management platforms. This layer is responsible not only for the transfer of patient records but also for their preprocessing and structuring into standardized formats suitable for automation. The subsequent RDA Execution Layer builds upon this foundation by deploying robotic desktop automation (RDA) tools to systematically input patient data into both web-based and PC-based government systems. By automating the majority of repetitive tasks, this layer significantly reduces clerical workload and minimizes the risk of human-induced errors. To address the common challenge of system updates and interface variability, the Generative AI Layer operates as an adaptive middleware that applies advanced natural language processing (NLP) and computer vision models to interpret user interfaces, dynamically remap workflow sequences, and validate data consistency. Together, these three layers form the technical backbone of the proposed automation engine.

Compared with prior RPA and AI-RDA architectures, the proposed framework emphasizes adaptability, semantic validation, and governance readiness across heterogeneous government platforms. Traditional RPA studies in healthcare typically target rule-based, task-level automation within a single web or desktop environment and do not provide robust self-healing against UI drift (e.g., layout or locator changes) [

6]. More recent “intelligent automation” approaches add machine-learning components to RPA, yet still require periodic retraining or manual reconfiguration when interfaces evolve, limiting resilience and scalability in practice [

9,

15]. In contrast, our AI-ERDA design integrates a generative reasoning layer with human-in-the-loop oversight to dynamically reinterpret changing UIs, perform cross-system semantic checks, and maintain auditable operation in complex nephrology data flows. This positions the framework as a step beyond rule-augmented RPA toward sustainable, trustworthy automation under real-world update cadence.

While automation provides efficiency, healthcare data workflows also demand mechanisms for safety, transparency, and accountability. These aspects are embodied in the final two layers of the architecture, which focus on governance and oversight. The Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Layer plays a critical role by introducing a human verification stage into the process, where anomalies, incomplete records, or context-dependent cases are flagged by the AI and subsequently reviewed by nephrology staff or data clerks. This hybrid approach ensures that decision-making for sensitive patient data is never fully delegated to automated systems, thereby safeguarding data integrity and regulatory compliance. The Monitoring and Logging Layer complements this oversight function by maintaining comprehensive records of all automated and human-involved actions, enabling traceability and auditability in line with healthcare governance frameworks. In practice, this layered structure integrates the strengths of deterministic RDA, adaptive generative AI, and human expertise, producing a scalable and sustainable architecture that not only reduces administrative burdens but also aligns with Thailand’s broader digital health transformation objectives.

3.2. RDA Bot Implementation and Generative AI Modules

The implementation of the proposed system integrates rule-based automation with adaptive generative intelligence to execute data entry across heterogeneous nephrology platforms (

Figure 2). The workflow begins with the Data Integration module, which securely collects and preprocesses patient records from hospital and dialysis management systems. Within the Automation Engine, deterministic robotic desktop automation (RDA) agents are deployed for both web-based and PC-based government systems. Web automation is handled through frameworks such as Playwright, enabling scripted navigation, form completion, and submission. Legacy PC systems are supported through desktop automation (e.g., PyAutoWin v0.6.8), simulating human interactions such as keystrokes and mouse events. To interpret diverse user interfaces, the system applies OCR (Tesseract v5.3.0) and computer vision (OpenCV v4.8.0) for field recognition, while administrative rules (Pydantic 2.6.0 schemas) validate field formats and enforce compliance with nephrology data standards. All actions, whether successful or error-prone, are logged for traceability within the monitoring layer, ensuring both transparency and security.

Beyond deterministic execution, the Generative AI modules enhance resilience and reduce human workload through three core functions summarized in

Table 1. First, Self-Healing Automation enables the bot to adapt automatically to minor UI modifications, such as renamed buttons or shifted field locations, without manual reprogramming. Second, Semantic Validation and Anomaly Detection ensure the integrity of clinical data by cross-checking entries, flagging abnormal dialysis frequencies, and detecting inconsistencies across multiple systems. Third, Decision Support for Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) allows the AI to prioritize flagged records and provide concise summaries of anomalies, enabling nephrology staff to review and approve submissions more efficiently. Together, these AI-enhanced functions transform a brittle automation pipeline into a robust and adaptive system, ensuring accuracy, accountability, and compliance across Thailand’s nephrology data ecosystem.

3.3. Human-in-the-Loop Oversight

Although robotic desktop automation and generative AI greatly enhance efficiency, healthcare data workflows demand safeguards that automation alone cannot guarantee. The proposed framework therefore integrates a HITL layer to ensure that ambiguous, anomalous, or high-risk records are verified by nephrology staff before being transmitted to government systems. Human oversight is essential because patient data entry often involves contextual judgment, such as interpreting unusual dialysis frequencies, validating incomplete laboratory results, or confirming compliance with evolving reporting policies, tasks where deterministic automation and AI reasoning may still be prone to error or bias. In practice, the AI modules assist by ranking flagged records according to severity and generating concise explanations, thereby reducing cognitive load and enabling staff to focus on the most critical cases. Each human decision is logged for traceability, producing a transparent audit trail that supports governance and accountability. This design aligns with emerging consensus in responsible AI for healthcare, which emphasizes that human oversight is indispensable for preserving trust, mitigating algorithmic risks, and ensuring that clinical and administrative decisions remain safe and ethically grounded [

13,

32].

3.4. System Implementation, Monitoring, and Security Compliance

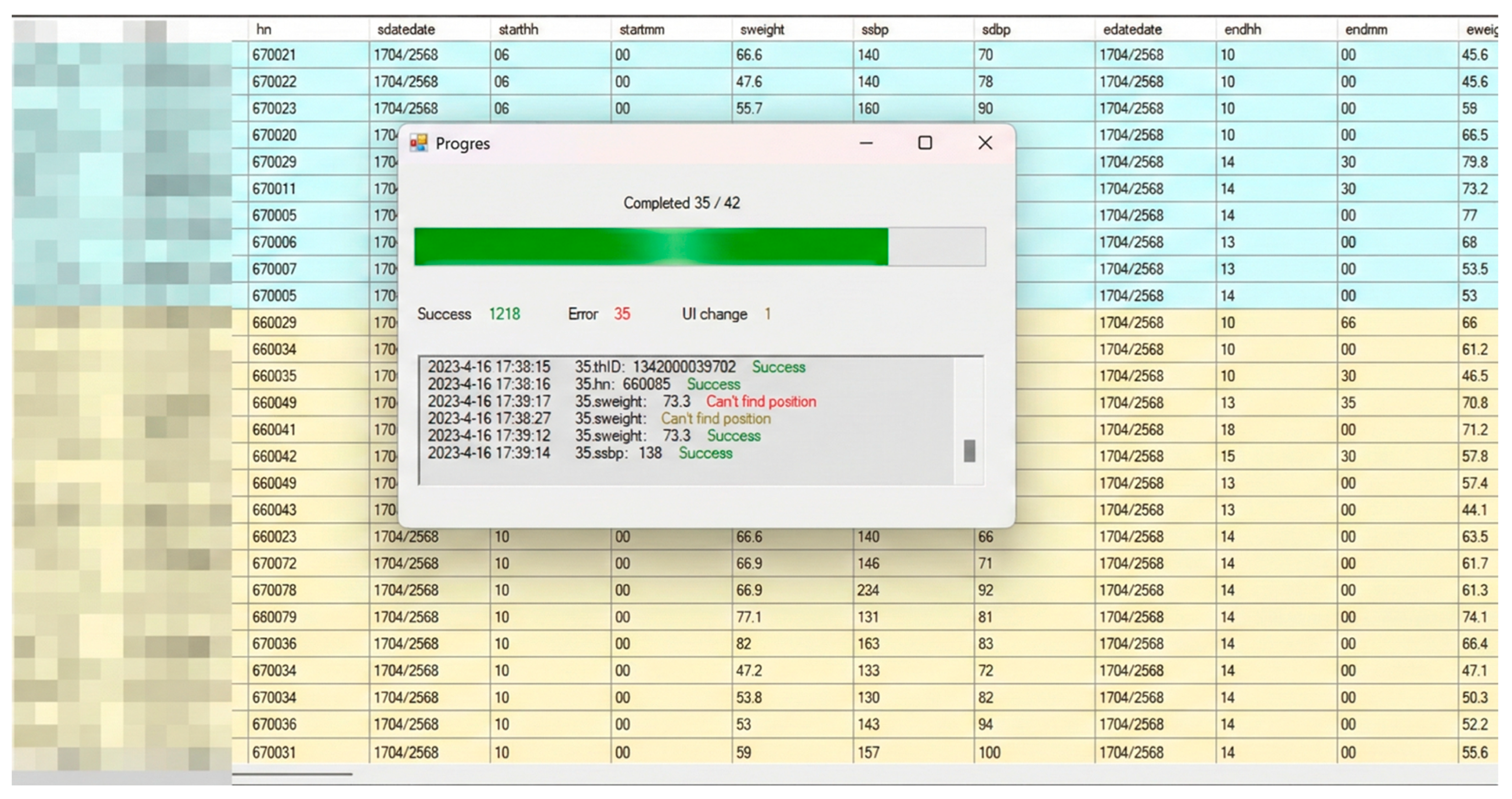

The AI-ERDA framework was implemented as an integrated automation system capable of operating across both web-based and PC-based healthcare platforms. The system interface (

Figure 3) includes a real-time monitoring dashboard that tracks progress, success rates, and error logs during automated data entry, ensuring transparency and facilitating rapid debugging. To enhance resilience, a built-in UI Change Detection module (

Figure 4) automatically identifies modifications in user interface elements such as field labels or layout positions, prompting user confirmation before adaptive remapping is applied. This self-healing mechanism enables the system to maintain accuracy and operational continuity even when unexpected UI changes occur, while all adjustments are logged for audit and model retraining.

To ensure data security and compliance, the AI-ERDA framework was developed under a privacy-by-design principle. All patient records were pseudonymized prior to automation, and all communication channels between modules utilized end-to-end HTTPS encryption. Access to sensitive data fields required authenticated session tokens verified through the hospital’s single sign-on (SSO) infrastructure. During task execution, HITL verification prevented automated overwriting or modification of protected data without explicit user approval. Furthermore, all automation actions, including field remapping events, were time-stamped and stored in encrypted audit logs to ensure traceability, accountability, and adherence to national e-health data protection standards. These mechanisms collectively safeguard patient information while preserving the transparency and reliability of the automation process.

4. Evaluation Methodology

4.1. Study Design

This study adopts an experimental design to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed Generative AI–ERDA framework compared with the baseline RDA system. Two groups were established: RDA System (control), which utilized the existing RDA system without AI augmentation, and AI-ERDA System (intervention), which employed the RDA framework integrated with generative AI modules for self-healing automation, semantic validation, and decision support to enable adaptive field mapping, contextual reasoning, and automated error correction during task execution. Both groups were assigned equivalent data entry tasks involving one web-based government platforms and two PC-based legacy systems. The overall experimental workflow is illustrated in

Figure 5.

The experiment was conducted over a two-month period to reflect realistic operating conditions. Specifically, data inspection and pilot testing were performed between May and June 2025, using anonymized nephrology workflow datasets extracted from the national dialysis information platform. The dataset covered patient record transactions recorded from January to April 2025, encompassing registration, treatment, and discharge reporting activities across three regional hospitals. A longer duration was intentionally selected because government health platforms frequently undergo minor UI adjustments or text modifications, which can disrupt conventional automation workflows. By extending the observation period to two months, the study increased the likelihood of encountering such variations, thereby providing a more rigorous assessment of the system’s resilience, adaptability, and real-world usability.

4.2. Participants and Setting

Participants were data entry clerks employed in nephrology centers across Thailand, all of whom had practical experience in handling government health information systems. The study involved two nephrology clinics per group, with each clinic contributing four clerical staff, resulting in a total of n = 8 per group and n = 16 overall. Clinics were purposefully selected to represent diverse operational environments while maintaining comparability in workload and patient record volumes. Clerical staff were responsible for daily entry of patient records into nephrology registries and national reporting platforms.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.3.1. Usability and User Experience

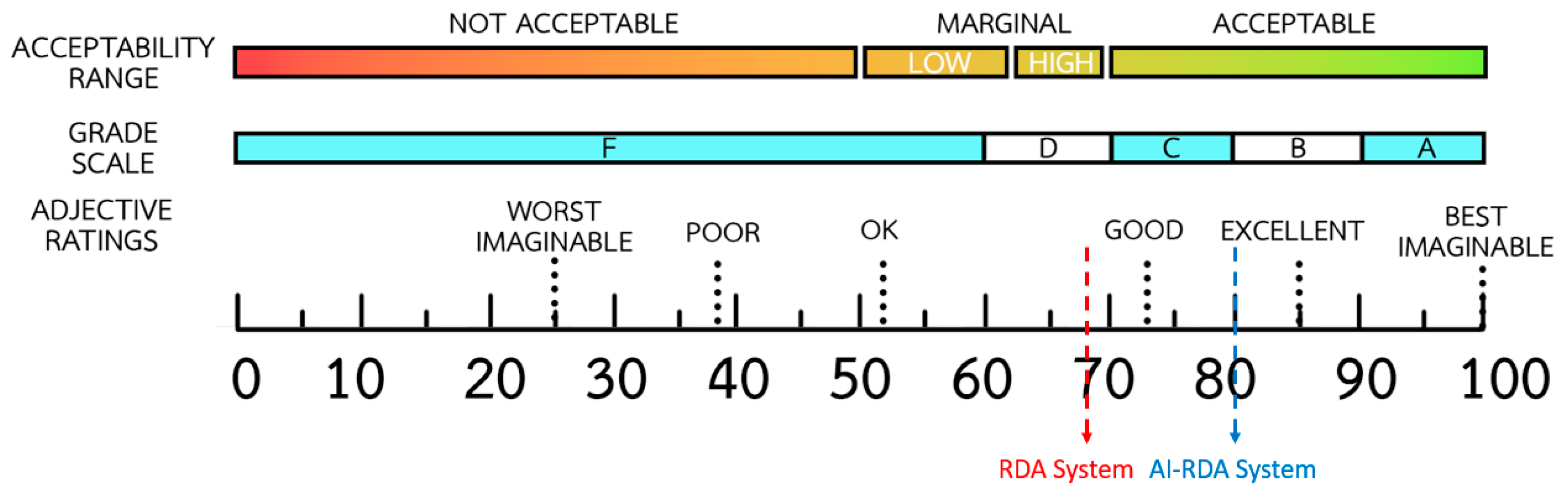

Usability was evaluated using the System Usability Scale (SUS), a standardized and validated instrument widely applied in assessing interactive systems [

33]. The SUS consists of ten items rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Responses are combined to produce a single composite score between 0 and 100, reflecting overall system usability [

34,

35]. Higher scores indicate greater user satisfaction and perceived ease of use, with a benchmark of 70 commonly recognized as representing acceptable usability. The questionnaire captures user perceptions of effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction after interacting with the system. Results were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, and confidence intervals, to summarize user experience.

4.3.2. Automation Accuracy

Automation accuracy was measured by comparing system outputs against a gold standard dataset. Two complementary indicators were used. The first was Field Exact-Match Accuracy, defined as the proportion of fields that were identical to the gold standard. This metric follows the principle of exact-match evaluation widely used in automated data validation and natural language processing benchmarks, where predicted outputs must perfectly coincide with reference values [

26,

36]. It was calculated as

This measure was applied to categorical or structured variables such as patient identifiers, dates of treatment, and insurance codes. The second indicator was Tolerance Accuracy (numeric), which captured whether numeric values fell within predefined clinically acceptable limits, consistent with tolerance-based evaluation used in medical data validation [

22,

37]. It was calculated as

Examples included dialysis start time within ±5 min, laboratory values within ±2%, and body weight within ±0.2 kg.

4.3.3. Resilience to UI Change

Resilience to UI change was evaluated to measure how effectively the automation frameworks could sustain accurate performance when user interface components or textual labels were modified. The assessment focused on monitoring Field Exact-Match Accuracy continuously over a 60-day period that included multiple UI modification events. Each event typically lasted around three days and involved adjustments to the structure or labeling of the web interface. Changes in accuracy during these events were analyzed to indicate the framework’s ability to adapt to altered interface layouts. The evaluation was visualized as a time-series plot of daily accuracy, allowing for a direct comparison of stability and recovery behavior after each UI change.

4.4. Data Collection Procedures

The data collection process was designed to evaluate the performance and resilience of both RDA and AI-ERDA automation frameworks across three major healthcare information systems. Each system represented a distinct operational environment and interface type, ensuring comprehensive testing of automation reliability in real-world conditions. The three platforms included: (1) the National Health Security Office (NHSO) system (

Figure 6), a web-based application used for processing healthcare benefit claims; (2) the Thai Nephrology Society (TRT) desktop application (

Figure 6), which manages patient registration and renal care records; and (3) the Health Service Information Bureau (CHi) platform (

Figure 7), a PC-based information system responsible for healthcare service reporting and data integration across hospital networks.

For each platform, a series of standardized automation tasks were developed to simulate routine data entry and verification workflows performed by healthcare officers. The testing period spanned 60 consecutive days, during which both the RDA and AI-ERDA systems operated under identical task sequences and datasets. Daily Field Exact-Match Accuracy and Tolerance Accuracy metrics were recorded automatically, along with system logs documenting response time, field errors, and recovery behavior. In the case of the web-based NHSO system, periodic UI changes were intentionally introduced to assess the resilience of both frameworks under dynamic interface conditions. For the PC-based TRT and CHi platforms, the evaluation focused on execution stability and handling of intermittent system latency.

6. Discussion and Findings

6.1. Interpretation of Usability Improvements

The overall SUS results revealed a substantial enhancement in perceived usability when the AI-ERDA framework was employed in place of the conventional RDA system. Qualitative feedback collected from participants during the two-month experiment provided strong contextual support for this quantitative gain. Many users reported that whenever a UI change occurred in the RDA system, they had to manually re-map input fields, verify corresponding data labels, and perform repeated test runs before resuming normal operation tasks, which were cognitively demanding, time-consuming, and often required waiting for the developer team to implement fixes. This interruption not only delayed routine data entry but also reduced user confidence in the reliability of the automation. In contrast, users operating the AI-ERDA system described a smoother workflow, as the AI modules could recognize modified interface layouts and automatically adjust field mappings with minimal human confirmation on the first day of change. Participants noted that this capability significantly reduced frustration and perceived workload, allowing them to focus on data accuracy rather than troubleshooting the tool itself. The 12-point increase in SUS (from 68 to 80) therefore reflects not merely improved interface design but a reduction in manual overhead and increased task-flow continuity under realistic healthcare system conditions.

When compared with prior research, the usability improvement observed in this study demonstrates a clearer and more stable enhancement than those reported in earlier RPA deployments. Huang et al. [

5] described that conventional RPA systems improved task efficiency but often left users burdened with post-update adjustments, while Park et al. [

6] found that even with monitoring capabilities, manual retraining remained a major source of user frustration. In contrast, the adaptive mechanisms of the AI-ERDA framework reduced these interruptions and promoted sustained confidence in automation, aligning with Thirunavukarasu et al. [

19], who emphasized that AI-driven systems can dynamically support users and lower cognitive demands. Similar patterns have also been reported in explainable-AI and healthcare-automation studies, which highlight that machine-learning-based interfaces enable smoother decision-making compared with static, rule-driven approaches [

38]. Moreover, the present findings extend prior adaptive-interface design research [

39] by demonstrating that self-healing and semantic-mapping capabilities can maintain usability continuity even under frequent UI variations.

6.2. Analysis of Automation Accuracy

Quantitatively, the AI-ERDA framework achieved superior automation accuracy across all platforms, with the largest gains observed on the web system where layout and labeling are most volatile. In this study, Field Exact-Match Accuracy increased from 97.2 ± 1.4 percent under RDA to 99.0 ± 0.5 percent under AI-ERDA, a gain of 1.8 percent. Likewise, Tolerance Accuracy improved by 0.8 percent, indicating that AI-assisted field recognition mitigated small formatting deviations and intermittent load delays. Participant feedback supported these metrics: the AI agent could “wait” for slow-rendering elements and re-associate fields after a UI update with minimal confirmation, whereas the conventional rules required manual remapping before data entry could continue. This dynamic adaptability allowed AI-ERDA to sustain automation continuity with minimal interruptions. On PC-based systems (CHi and TRT), both frameworks performed nearly perfectly, maintaining accuracy above 99.5 percent; however, AI-ERDA still demonstrated slightly tighter variance under transient latency, consistent with findings that learning-based interfaces sustain performance in the presence of runtime perturbations [

39].

Compared with earlier RPA and intelligent automation studies, these findings demonstrate a clearer resilience advantage under dynamic interface conditions. Schwamm et al. [

39] reported that conventional RPA enhanced process stability but often failed to recover from locator drift without manual rule reconfiguration, while Nimkar et al. [

40] showed that hybrid RPA–ML systems reduced error propagation but required periodic retraining. In contrast, the generative AI modules in AI-ERDA achieved comparable precision without retraining, maintaining continuity through contextual recognition of UI patterns. This result extends the conclusion of Figueroa et al. [

41], who found that adaptive learning improved recognition accuracy via user feedback loops, by demonstrating that generative reasoning can achieve similar adaptability autonomously. Moreover, our findings align with Fairhurst et al. [

29], who highlighted that AI-driven context reasoning enhances data precision and reduces human correction needs in healthcare workflows, and with Baqar et al. [

42], who emphasized that self-healing automation minimizes failure rates after interface updates. Together, these comparisons indicate that AI-ERDA not only aligns with but advances the current evidence on accuracy stability and recovery efficiency in intelligent RPA systems.

6.3. Evaluation of System Resilience and Adaptability

The resilience evaluation revealed clear distinctions between the AI-ERDA and traditional RDA frameworks when subjected to real-world UI changes. Across a 60-day observation period, three genuine UI modification events occurred within the web-based NHSO system, while both PC systems (CHi and TRT) remained largely stable. During these web interface changes, the RDA framework experienced significant performance degradation, with Field Exact-Match Accuracy dropping to approximately 94 percent and requiring manual reconfiguration that lasted up to three days for full recovery. In contrast, the AI-ERDA system demonstrated rapid self-correction capabilities: accuracy declined only slightly (by about 1–2 percent) on the first day following each UI change before recovering to near-perfect levels once the AI model had re-learned new field associations. The ability to sustain automation accuracy without developer intervention highlights the framework’s capacity for autonomous adaptation, an essential property for large-scale healthcare systems, where even brief interruptions can compromise data integrity and delay service delivery. Moreover, the benefits of AI-ERDA were particularly evident in the web-based system, which undergoes frequent updates and layout modifications, while the PC-based systems showed minimal differences due to their static and stable interface structures.

These findings align strongly with emerging research in adaptive AI systems and self-healing automation. Studies have shown that machine learning–driven RPA frameworks outperform traditional scripts when exposed to UI drift or evolving software environments, thanks to their capacity to detect anomalies and autonomously rebuild field relationships [

39,

42]. Similarly, resilience engineering in healthcare informatics emphasizes maintaining system functionality during unforeseen interface or data structure changes [

43]. In particular, semantic AI models can dynamically adapt to new input schemas and recover from unexpected disruptions by leveraging contextual embeddings and pre-trained decision models [

39]. Compared with these prior approaches, the AI-ERDA framework demonstrates a more immediate recovery cycle and does not rely on manual retraining or explicit anomaly labeling. While Schwamm et al. [

39] and Abhichandani et al. [

42] documented post-failure recovery times ranging from several hours to days in intelligent RPA systems, the generative reasoning component of AI-ERDA enables near-continuous operation under similar UI drift conditions. This observation complements the theoretical perspectives of Tolk et al. [

43] on resilience engineering by providing empirical evidence that contextual AI integration can sustain operational robustness in a live government healthcare setting. Furthermore, the outcomes extend the work of Thirunavukarasu et al. [

19] and Fairhurst et al. [

29] by demonstrating that self-adaptive automation not only reduces maintenance burden but also reinforces user trust through uninterrupted workflow continuity. Therefore, the superior resilience of AI-ERDA confirms its readiness for deployment in complex, continuously evolving healthcare ecosystems, where interface stability cannot always be guaranteed and reliability is critical to patient data management.

6.4. Implications for Healthcare Data Automation

The integration of AI-ERDA within healthcare data workflows carries substantial implications for the efficiency, reliability, and long-term sustainability of digital health infrastructures. The experimental findings demonstrate that generative and adaptive automation can reduce manual workload, mitigate downtime, and enhance data quality in government health systems. In practice, such improvements translate directly into faster case processing, fewer human errors, and greater data completeness across interconnected agencies. In systems like NHSO, where personnel routinely manage thousands of records per day, even a one to two percent accuracy improvement represents a meaningful gain in operational throughput and public service reliability. Moreover, by automatically adapting to UI modifications without developer intervention, AI-ERDA reduces system maintenance costs and shortens response times during software updates. These outcomes align with broader policy goals in digital transformation and “AI for Public Health,” where automation serves as both an efficiency multiplier and a reliability assurance mechanism. Importantly, user feedback also revealed enhanced trust and satisfaction when AI systems demonstrated transparent reasoning and consistent performance—two crucial dimensions of human–AI collaboration in healthcare contexts [

19]. Recent reviews also emphasize that AI adoption in healthcare must balance efficiency gains with ethical governance and safety oversight [

44,

45].

Beyond immediate operational gains, the broader implications of AI-assisted automation extend toward building resilient, learning-driven infrastructures for healthcare data ecosystems. As healthcare systems evolve toward interoperability and continuous data integration, the ability of automation frameworks to adapt across variable contexts becomes essential [

29]. Adaptive AI agents embedded within RDA pipelines can serve as intelligent intermediaries that ensure accurate data exchange among diverse hospital information systems, laboratory databases, and national health registries. This capability reduces the cognitive and administrative load on healthcare personnel, allowing them to focus on higher-value analytical and clinical tasks. Furthermore, self-healing automation not only supports technical efficiency but also enhances governance and auditability by maintaining verifiable logs of every automated correction [

39,

42]. Nevertheless, despite these promising advantages, human oversight remains indispensable in healthcare data automation. Given the high-stakes nature of clinical information, final-stage verification by human experts is essential to ensure patient safety, ethical compliance, and contextual accuracy. Thus, AI-ERDA represents a pathway toward sustainable digital transformation, where automation acts not as a replacement for human intelligence but as a collaborative partner that strengthens resilience, transparency, and accountability in healthcare data management.

6.5. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Work

While this study provides compelling evidence of the AI-ERDA framework’s superiority in usability, automation accuracy, and resilience, several limitations merit attention. The experiments were conducted on three healthcare platforms over a 60-day period, which, although sufficient to capture genuine UI changes, may not fully reflect the diversity and long-term evolution of complex national health systems. The framework’s adaptability was primarily reactive, responding to UI alterations after they occurred rather than anticipating them. Moreover, while quantitative metrics such as Field Exact-Match Accuracy and Tolerance Accuracy effectively measure performance, they do not fully capture aspects of explainability, ethical transparency, or user trust, which are essential for responsible AI adoption. Future research should therefore pursue proactive adaptation through reinforcement or self-predictive learning agents capable of forecasting UI evolution, as well as cross-platform semantic alignment to strengthen interoperability. Incorporating explainable AI mechanisms and human–AI co-adaptation studies will also be vital to ensure user confidence, traceability, and accountability. Addressing these directions will enable AI-ERDA to evolve from adaptive automation into a fully autonomous, interpretable, and ethically aligned framework for sustainable healthcare data ecosystems.

7. Conclusions

This study proposed and empirically validated the AI-ERDA framework as a novel solution for improving healthcare data entry across multiple government platforms. By integrating generative and adaptive AI components such as self-healing automation, semantic validation, and intelligent waiting, the framework achieved measurable improvements in usability, automation accuracy, and resilience under real-world operating conditions. Compared with the conventional RDA system, AI-ERDA demonstrated a 12-point increase in usability (SUS 68 to 80), an average accuracy gain of up to 1.8 percent in web environments, and near-perfect performance stability despite multiple genuine UI change events during a 60-day evaluation period. The framework’s generative reasoning and human-in-the-loop oversight reduced manual reconfiguration, maintained workflow continuity, and strengthened user confidence, confirming its suitability for mission-critical healthcare automation. These results collectively indicate that AI-driven adaptability not only minimizes manual intervention but also ensures data reliability and operational sustainability in dynamic healthcare contexts.

Positioned within broader research trends, this work contributes to the ongoing evolution of Robotic Process Automation (RPA) toward intelligent, generative, and governance-driven automation paradigms. Recent studies have highlighted the transition from static, rule-based RPA to context-aware frameworks that integrate machine learning and human oversight to enhance transparency, resilience, and ethical governance [

9,

15]. The proposed AI-ERDA framework advances this trajectory by operationalizing these principles within regulated public-health infrastructures, bridging theoretical notions of trustworthy and explainable AI [

13] with empirical validation in large-scale government systems. This alignment resonates with the growing digital-health literature emphasizing sustainable, human-supervised AI ecosystems that safeguard data integrity and compliance [

6,

28,

29]. Future research should therefore extend this work toward cross-domain deployment, governance assessment, and longitudinal safety auditing, reinforcing AI-ERDA’s role in shaping the next generation of adaptive, human-centered digital transformation in healthcare.